Turning Critics into Criminals

The Human Rights Consequences of Criminal Defamation Law in Indonesia

Map of Indonesia

Summary

I sent a private email to friends about what really happened and suddenly I am made a criminal. I had to go to prison, I had to go to court, I had to go a second time, and it’s still happening.… I’m worried about the future…. I want to continue my life.

—Prita Mulyasari, prosecuted on charges of criminal defamation for sending an email criticizing her doctors to friends.

My husband said, “You are fighting with a tycoon and cannot win.” It’s like the law of the jungle. There is no justice here. All of us tell the truth but they put us in jail.

—Fifi Tanang, convicted of defaming a real estate developer in a letter to the editor of a newspaper.

My eyes filled with tears as I kissed the cheeks of my little kids. What will happen to them? I told them, “don’t be embarrassed that I’m going to prison because of my writing. Take care of the children,” and kissed my wife.

—Risang Bima Wijaya, imprisoned for publishing unflattering newspaper articles on a local media figure accused of a crime.

Holding public demonstrations protesting corruption, writing letters to the editor complaining about fraud, registering formal complaints about acts of impropriety by politicians, and writing and publishing news reports about sensitive subjects are common practices in a democratic society. But in Indonesia, such criticism can lead to criminal charges and land you in prison, even if what you say is true.

Indonesia in recent years has eliminated many of the most pernicious laws that officials once used to silence critics, but criminal defamation and insult laws remain on the books. Those laws remain potent weapons and continue to be used by officials and powerful private actors seeking to silence non-violent criticism and opposition.

Defamation laws exist to protect individuals from having their reputations intentionally and falsely tarnished by others. Civil defamation laws allow an injured party to sue and seek remedies ranging from monetary compensation to an apology or retraction and exist in all or virtually all countries. Some countries, however, also impose criminal penalties, including imprisonment, for reputational harm.

International human rights law allows for restrictions on freedom of expression to protect the reputations of others, but such restrictions must be necessary and narrowly drawn. Together with an increasing number of governments and international authorities, Human Rights Watch believes that criminal penalties are always disproportionate punishments for reputational harm and should be abolished. As repeal of criminal defamation laws in an increasing number of countries shows, such laws are not necessary: civil defamation and criminal incitement laws are sufficient for the purpose of protecting people’s reputations and maintaining public order and can be written and implemented in ways that provide appropriate protections for freedom of expression.

Criminal defamation laws are also impermissible because they are more open to abuse than civil defamation provisions, and when such abuse occurs, victims can experience very harsh consequences, including imprisonment. Although civil defamation laws can also be abused, their impact is not as devastating as criminal defamation laws can be. As one Indonesian charged with criminal defamation told Human Rights Watch, “In a civil case, there is no threat of being in prison—the sanction is much lighter…. But a criminal case will rob you of everything, including your freedom.”

This report details the continuing negative impact of criminal defamation laws in Indonesia and urges their repeal.

* * *

Indonesian law contains a number of different criminal defamation provisions. One provision of the Indonesian Criminal Code prohibits individuals from intentionally publicizing statements that harm another person’s reputation, in many cases even if those statements are true, and punishes such conduct with imprisonment for up to 16 months. In circumstances in which the accused is allowed to assert truth as a defense, the penalty goes up to four years should they fail to prove what they wrote or said was true.

Another provision imposes somewhat longer sentences where the defamed party is a public official acting in official capacity: deliberately “insulting” a public official, even if one’s statements are true, can land one in prison for 18 months.

Finally, a new law enacted in 2008 punishes defamation sent over the internet with up to six years’ imprisonment and fines of up to Rp1 billion (approximately US$106,000 as of January 1, 2010).

All of these laws contain extremely vague language. As a result, whether by design or as a result of poor drafting, public officials can use defamation laws to criminalize not only the intentional spreading of malicious lies but also citizen complaints or reports of corruption and other misconduct by public officials, airing of business disputes and consumer complaints, and critical reporting by the media. We present examples of each in this report.

For example, Bersihar Lubis, a veteran reporter in Medan, was convicted of criminal defamation in February 2008 after he wrote an opinion column criticizing the Indonesian attorney general’s decision to ban a high school history textbook. Khoe Seng Seng, Kwee “Winny” Meng Luan, and Fifi Tanang of Jakarta were found guilty of criminal defamation in 2009 for writing letters to the editors of local newspapers alleging that they had been victims of fraud—which they had also reported to the police. Tukijo, a farmer in Kulon Progo regency of Yogyakarta, was convicted of criminal defamation in January 2010 for asking the head of his sub-district for information about the results of a land assessment.

Recognizing that media freedom, “whistleblowing” by consumer and corruption watchdogs, and other forms of expression are valuable and should be protected, Indonesian law enforcement officials and legislators have articulated a number of policies and enacted laws that are intended to safeguard the right to freedom of expression. However, in several cases Human Rights Watch investigated, these legal and policy measures proved inadequate to address the threat to free expression posed by defamation laws, even when they were brought to the attention of law enforcement officials.

Criminal defamation laws are also open to manipulation by individuals with political or financial power, who can influence the behavior of investigators. In one of the cases profiled in this report, the complainant had the ability to interfere directly with the subsequent investigation: the police chief of a major city brought defamation charges against a journalist, Jupriadi “Upi” Asmaradhana, and then ordered his subordinates to investigate the charges.

In the majority of the criminal defamation cases we examined, powerful national or local-level actors filed criminal defamation complaints with the police as a direct response to allegations of corruption, fraud, or misconduct made against them. Occasionally, the investigations that followed involved improper or intimidating conduct by the authorities, raising suspicion of improper influence over the implementation of the defamation laws.

For example, in October 2009, after Indonesia Corruption Watch activists Emerson Yuntho and Illian Deta Arta Sari criticized law enforcement officials for investigating officials of the Corruption Eradication Commission (Komisi Pemberantasan Korupsi or KPK) on trumped-up abuse of power charges, police summoned them for questioning on a criminal defamation complaint that had been filed against them nine months earlier, in January 2009. The suspicious timing of the summons suggests that authorities hoped to use the criminal defamation charges against the activists to deter criticism of their trumped-up charges against the KPK officials, charges later shown to have been based on fabricated evidence.

In April 2009, Bambang Kisminarso filed a complaint with a local election supervisory commission alleging that supporters of the son of Indonesia’s president, then a candidate for parliament, had been giving money to prospective voters. Three days later, police arrested him and his son-in-law M. Naziri on charges that they had defamed the president’s son in violation of the defamation provisions of Indonesia’s new internet law (Undang-Undang Informasi dan Transaksi Elektronik or ITE law). The ITE law contains the only defamation-related offense in Indonesian law for which pre-trial detention is permitted. This is despite the fact that there were no allegations that either Bambang or Naziri had made any of their allegations online.

Investigations and prosecutions under criminal defamation laws can have a disastrous and long-lasting impact on the lives of those accused. Journalists accused of defamation told us they found it difficult or impossible to find work after charges were filed. Other individuals charged with defamation have lost their jobs and suffered serious professional setbacks as a result of being required to submit to interrogations, complete twice-weekly check-ins with authorities, attend weekly trial sessions, and endure bureaucratic procedures that can last for years without resolution. And the threat of imprisonment hangs over all individuals accused of defamation or convicted and sentenced to probation.

Prita Mulyasari spent three weeks in pre-trial detention in May 2009 on internet defamation charges stemming from an email she wrote to friends criticizing doctors who had misdiagnosed her. In November 2009, after prosecutors demanded a six-month sentence, Prita told Human Rights Watch she feared she would be unable to endure the punishment, saying of her earlier detention, “21 days was like 21 years.”

The application of criminal defamation laws in Indonesia gives rise to a damaging, chilling effect on speech central to the effective functioning of a democratic society. It can seriously undermine the work of local NGOs and community-level actors working to combat corruption.

Mohammad Dadang Iskandar, the director of Gunungkidul Corruption Watch in Yogyakarta province, says that since he was accused of criminal defamation by local legislators following an anti-corruption demonstration he coordinated, former fellow activists refuse to work with him. “They are scared, worried. They feel threatened because the police are questioning them,” he told Human Rights Watch.

Similarly, Jamaludin bin Sanusi and Badruzaman, members of the West Java student group the Coalition of Students and People of Tasikmalaya (Koalisi Mahasiswa dan Rakyat Tasikmalaya, orKMRT), and their advisor, Zamzam Zamaludin, continue to feel the effects of the criminal defamation process they faced. All three men were accused of criminal defamation by a local education official after they held a demonstration protesting the official’s refusal to cooperate with an inquiry by the local legislature into allegations that he had engaged in misconduct. Even though he and his colleagues were eventually acquitted on criminal defamation charges, Zamaludin told Human Rights Watch that, “Even today, KMRT is seen as a public enemy by local government [officials] and civil society organizations … I felt like a public enemy [during the criminal trial], and I still do now.”

Another consequence of Indonesia’s criminal defamation laws is their ability to encourage media self-censorship—inside and outside Jakarta—on issues of great importance when they involve powerful public figures. One journalist, who declined to be named in this report, told Human Rights Watch that more than one media outlet has deliberately refrained from reporting news about the president’s son as a reaction to the heavy-handed official response that accompanied reports of the election complaint against his supporters, saying “[w]hatever [he] does is newsworthy, but now we’re not able to report about it.” As Risang Bima Wijaya, a reporter formerly based in Yogyakarta who was convicted and imprisoned for criminal defamation, told Human Rights Watch, “It was like an infection with other journalists when they found out” about his conviction.

The increased prison terms provided for in the ITE law, Indonesia’s new internet law, pose an increasingly powerful threat to private citizens who express their thoughts or opinions online. As Prita, who spent over 12 months in the criminal justice process and faced six months in prison simply for sending an email to friends, lamented, “I don’t know how to complain again.” In these and other ways, criminal defamation laws undermine democracy, the rule of law, and freedom of expression in Indonesia.

Human Rights Watch believes that Indonesian officials should promptly initiate repeal of the defamation provisions of the Criminal Code and the new internet law, replacing them with civil defamation provisions that contain adequate safeguards to prevent unwarranted limitations on freedom of expression.

Human Rights Watch also urges the Indonesian government to:

- Acknowledge that criminal law is an inappropriate and disproportionate response to the problem of reputational harm and commit to the repeal of all criminal defamation provisions in Indonesian law.

- Until the criminal defamation provisions of the Criminal Code and internet law have been repealed, ban government officials from filing criminal defamation complaints.

Methodology

This report is based on research in Indonesia in October and November 2009 and on follow-up telephone and desk research through March 2010. Human Rights Watch conducted in-depth interviews with 32 defendants and witnesses in criminal defamation investigations. Interviews were conducted in Jakarta, Yogyakarta, Ponorogo, Surabaya, Makassar, Medan, and Tasikmalaya, in English or in Indonesian through an interpreter. We identified interviewees through media reports and with the assistance of NGOs in the cities of Jakarta and Yogyakarta.

Human Rights Watch also interviewed more than 35 Indonesian government officials, civil society activists, lawyers, and Indonesia-based staff of international organizations.

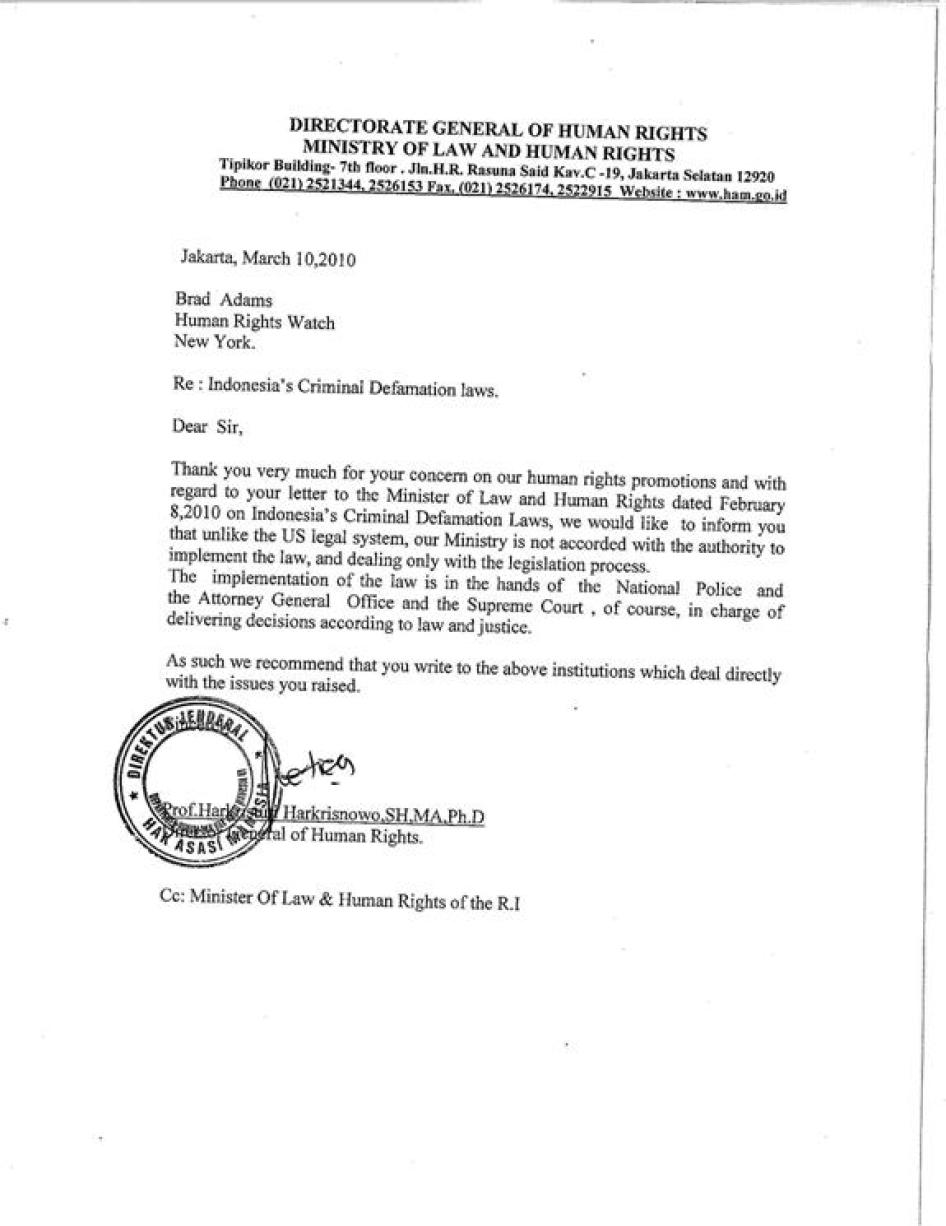

In October 2009 Human Rights Watch sent letters to the Indonesian Ministry of Law and Human Rights, National Police, and Office of the Attorney General requesting meetings to solicit views on the application of criminal defamation laws in Indonesia and steps the relevant officials were taking to minimize abuses. Despite numerous attempts to follow up on those written requests, we received no replies and none of the officials agreed to meet. Human Rights Watch was able to meet with Benny K. Harman, a legislator and chairman of the parliamentary commission with responsibility for issues involving “law and human rights,” but he declined to respond to a later request by Human Rights Watch for his views on some of the issues raised in this report.

In February 2010 Human Rights Watch sent letters to the Indonesian officials listed below to obtain data, including statistics on the frequency of criminal defamation prosecutions and laws and policies designed to prevent the misuse of defamation law, and to solicit their views on the issues addressed in this report:

Patrialis Akbar, minister of Law and Human Rights

Tifatul Sembiring, minister of Communications and Information Technology

Djoko Suyanto, coordinating minister for Political, Legal, & Security Affairs

Marzuki Alie, speaker of the House of Representatives

Kemal Azis Stamboel, chairman, DPR Commission I (Defense, Foreign Affairs, and Information)

Benny K. Harman, chairman, DPR Commission III (Law and Human Rights)

Hendarman Supandji, attorney general

Gen. Bambang Hendarso Danuri , chief of National Police

H.E. Salman Al Farisi, chargés d’affaires, Embassy of Indonesia to the United States

H.E. Hasan Kleib, chargés d’affaires adinterim, Permanent Mission of Indonesia to the United Nations

At this writing, only Prof. Harkristuti Harkrisnowo, director general of human rights at the Ministry of Law and Human Rights, had responded, and then only to inform Human Rights Watch that the ministry has no authority to implement laws and to suggest that Human Rights Watch contact other government agencies. Harkrisnowo’s letter did not address the many questions raised that were not related to the implementation of the laws, including those that sought clarification about the interplay of criminal defamation provisions and other laws designed to guarantee freedom of expression, nor specific questions inquiring whether the ministry intended to propose amendments to Indonesian laws to address the issues identified in this report.

On March 24, 2010, Human Rights Watch sent a follow-up letter to the Office of the Attorney General and National Police again requesting their reply to the questions we raised. As of April 15, 2010, we had received no response.

Human Rights Watch’s letters and the response from Prof. Harkrisnowo are attached in this report’s appendix.

Human Rights Watch does not take a position on whether the conduct in which the individuals profiled in this report engaged constitutes civil defamation; rather, we oppose Indonesia’s classification of such non-violent conduct as a potential criminal offense.

I. Freedom of Expression in Indonesia

Indonesia’s constitution explicitly protects freedom of expression. Article 28(e) states, “Every person shall have the right to the freedom of association and expression of opinion.”[1] Article 28(f) states, “Every person shall have the right to communicate and obtain information for the development of his/her personal life and his/her social environment, and shall have the right to seek, acquire, possess, keep, process, and convey information by using all available channels.”[2]

Despite these guarantees Indonesia has a long history of state-sponsored repression of free expression and non-violent criticism. Starting in the late 1950s during the latter years of President Sukarno’s “Guided Democracy” rule, and intensifying during President Suharto’s more than 32 years in power (1965/66 to 1998), freedom of expression was broadly repressed in the name of “national stability.”[3] President Suharto ruled Indonesia as a police state, and officials in his “New Order” government used far-reaching censorship, surveillance, ideological pressure, intimidation, harassment, and imprisonment of outspoken critics to stymie open inquiry and debate on fundamental issues facing Indonesian society.[4] Individuals who challenged the militaristic underpinnings of New Order rule or attempted to organize independent political opposition, including political dissidents and journalists, were made the object of aggressive campaigns in which law was manipulated as a tool of official repression.[5]

In carrying out this repression New Order officials invoked the very provisions of the Indonesian Criminal Code that former Dutch colonial administrators had used to suppress opposition to colonial rule by the Indonesian people.[6] These included articles 154-156 of the Criminal Code, “hate sowing” (haatzai artikelen) articles which prohibited “public expression of feelings of hostility, hatred or contempt toward the government”; articles 134-137, 207, and 208, lese majeste provisions which prohibited “defaming” the head of state, “deliberate disrespect” for the president, vice-president, and other government officials, and the “dissemination, display or posting” of material “offensive” to such officials;[7] and Suharto’s Presidential Decree 11/1963 on Subversion.[8] These disparate provisions had two common features: all could be used to restrict popular criticism of the state’s actions and policies and all were vaguely worded and subject to arbitrary application.[9]

After Suharto’s fall from power in the face of large-scale protests in 1998, there was an eruption of public expression in Indonesia as many of the old constraints fell away, with over 700 new magazines and newspapers founded in the 10 months following his resignation alone.[10] While Suharto’s immediate successors, President B.J. Habibie and President Abdurrahman Wahid, were far more tolerant of dissent and largely let the media flourish, neither administration repealed the repressive laws most frequently employed by Suharto against critics and neither did enough to reform Indonesia’s law enforcement institutions in ways that would ensure their independence and accountability.

When Megawati Sukarnoputri ascended to the presidency in 2001, she inherited a law enforcement apparatus that remained vulnerable to—and even calibrated for—abuse by public officials unwilling to tolerate peaceful dissent. In 2003 Human Rights Watch documented a noticeable increase in criminal prosecutions of non-violent political activists solely for expressing their political views at peaceful demonstrations and of journalists for publishing articles deemed to have “insulted” the president.[11] Often, the provisions employed to criminalize criticism of Megawati and her administration’s policies were the very same lese majeste and “hate sowing” articles of the Criminal Code used by Suharto.[12]

Since 2004 Indonesia has been governed by the administration of President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, who came to power on a moderate platform that stressed the eradication of corruption as one of its principal objectives.[13] In the early years of Yudhoyono’s presidency, Indonesian officials occasionally resorted to the same legal provisions as his predecessors to punish citizens who petitioned the authorities to investigate rumors of high-level corruption and peacefully criticized the government.[14] However, in a series of groundbreaking judicial decisions in 2006 and 2007, the Indonesian Constitutional Court declared both the “hate sowing”and lese majeste articles of the Criminal Code to be unconstitutional.

In 2006 the court reviewed three of the Criminal Code’s lese majeste provisions, article 134, 136 bis, and 137, which provided heightened penalties for defaming or insulting the president and vice president.[15] The court noted that the authorities could potentially use such articles to violate demonstrators’ freedom of expression. It expressed concern that the application of these provisions could “result in legal uncertainty,” because whether or not a given protest, statement, or opinion constituted defamation against the president or vice president was a matter of subjective interpretation.[16] The court further noted that the provisions could obstruct the proper functioning of democracy in Indonesia, as guaranteed by its constitution, since they could be used to criminalize anyone attempting to determine whether or not the president or vice president had violated the law.[17]

In 2007 the court similarly ruled that two of the Criminal Code’s “hate sowing” provisions, articles 154 and 155, were unconstitutional, determining that the articles could “allow power abuse to occur,” insofar as they could be easily invoked by the authorities to justify punishing citizens merely for criticizing the government, a right protected by Indonesia’s constitution.[18] Declaring that the articles “do not guarantee legal certainty and … as a consequence, disproportionately hinder the freedom to express thoughts and the freedom to express opinions,” the court found them contrary to the 1945 constitution.[19]

Following these landmark decisions, the legal tools most frequently employed to suppress peaceful dissent in Indonesia disappeared. Yet the court’s opinions did not completely eliminate criminal penalties for non-violent speech. Rather, in its decision invalidating the lese majeste articles, the court specifically called upon public officials to use the Criminal Code’s other criminal defamation articles to protect the reputations of public officials, as well as regular citizens, from attack.[20] Even before the Constitutional Court’s ruling, those articles had already been used against critics of lower-level officials and high-profile private individuals.[21] By 2007 President Yudhoyono had similarly deployed them against a critic as well.[22]

In the 12 years that have passed since President Suharto’s resignation, Indonesia has pursued an ambitious decentralization program in which regional, district, and municipal-level governments have been given significant power over fiscal management, legislation, and policy-making in a wide variety of areas previously managed solely by the central government.[23] Unfortunately the decentralization of authority has also brought about the decentralization of opportunities to engage in corruption and abuse of power.

A 2007 study by the World Bank found that the shift in power relations brought about by decentralization—both between the central and regional governments and between branches of government at the regional level—had given rise “to rampant ‘money politics.’”[24] The report further noted, “[a]ll sides have taken the chance to embezzle funds for self-enrichment,” and have been aided in doing so both by “regular ‘cooperation’ between the legislative and executive bodies as well as low levels of public participation and control in local governance.”[25]

The World Bank study also identified a more positive trend: the emergence of national and local-level NGOs dedicated to investigating and publicizing official corruption.[26] Indeed, the authors found:

Regardless of where the initial reports originated, NGOs or NGO coalitions were the driving force for public disclosure and resolution of the cases studied…. In the not too distant past, these cases would never have come to light at all. This process has begun to undermine the deeply entrenched culture of impunity which has long characterized governance in Indonesia. And although their capacity to review local budget documents and investigate corruption remains limited, complaints filed by anticorruption actors were in all instances the driving force behind the cases coming to public attention.[27]

In a majority of the cases discussed in this report, the criminal defamation complaints were filed by powerful national or local actors to silence individuals who had made allegations of corruption, fraud, or misconduct. In some of these cases the investigations conducted into the defamation charges appeared to contain procedural irregularities or behavior that suggested bias. When used in this manner criminal defamation laws pose many of the same risks to freedom of expression as did the now-defunct lese majeste and “hate sowing” articles of the Criminal Code.

II. The Legal Framework: Criminal Defamation Law in Indonesia

Defining Defamation

Broadly speaking, defamation laws prohibit individuals from injuring the reputation of another person in the form of a spoken statement (commonly called “slander”) or in writing (commonly called “libel”). In some countries, “insult” laws specifically criminalize expressions deemed to offend the honor of public officials and institutions.[28] Defamation laws—which are only intended to protect honor and reputations—are distinct from incitement or “hate speech” laws, which are intended to serve the purpose of maintaining public order and prohibit forms of expression that are intended and likely to provoke imminent violence.

All states have adopted some form of defamation law to protect individuals from unwarranted attacks on their reputations. Some only have civil defamation laws, meaning that individuals who believe they have been defamed may have access to a judicial remedy, but as a private actor, on their own initiative.[29] If an individual is found guilty of civil defamation, he may be required to pay compensation to the defamed party or to take other measures such as publicly retracting the defamatory statement. Other states, including Indonesia, have both criminal and civil defamation laws, meaning that individuals may file a claim alleging defamation with the police, and the police and prosecutors will then use public funds to investigate the case on behalf of the state. Under criminal laws the courts can punish those found guilty of defamation with fines or even imprisonment.

Criminal Defamation Law in Indonesia

The Criminal Code

The Indonesian Criminal Code contains a number of articles that provide penalties for defamation.[30]

Article 310 prohibits defamation, defined as “intentionally harm[ing] someone’s honour or reputation by charging him with a certain fact, with the obvious intent to give publicity thereof,” in the form of slander (punishable by up to nine months imprisonment)[31] and libel (punishable by up to one year and four months imprisonment).[32] An individual accused of defamation may claim in his defense that he was acting in the “general interest” or out of necessity.[33] The accused may seek to prove that his statement is true to escape punishment, but only if he or she claims that he acted “in the general interest” or out of necessity, or if the allegedly defamatory statement concerns an official acting in his official capacity. In cases in which a judge allows the accused to establish the truth of his statement, the burden of proof is on the accused and, if he fails, he can be found guilty of “calumny” under article 311, which carries a more severe penalty of up to four years’ imprisonment.[34]

Other criminal defamation provisions are contained in article 315, which prohibits “simple defamation” (punishable by up to four-and-a-half months’ imprisonment),[35] and article 335, which prohibits forcing someone “to do, omit, or tolerate something” by threatening to defame them (punishable by up to one year of imprisonment).[36]

Two provisions in the Criminal Code provide heightened protection to public officials and bodies which invoke criminal defamation provisions. Under article 316, the punishments for all defamation offenses (other than the extortion offense in article 335) may be increased by one-third where the complaining party is a public official and the alleged defamation related to the exercise of his office.[37] Articles 207 and 208 codify separate “insult” laws which prohibit deliberately “insult[ing] an authority or public body set up in Indonesia” (punishable by up to one year and six months of imprisonment) and “disseminating,” “demonstrate[ing],” or otherwise publicizing pictures or text that contain insults against authorities or public bodies.[38]

All of the criminal defamation provisions are punishable in the alternative by fines. However, one consequence of Indonesia’ continued reliance on the colonial-era Criminal Code is that the maximum fines provided for under the Criminal Code’s provisions have not been readjusted to account for inflation for decades, with the result that fine amounts are so low as to render them utterly insignificant (at the time of writing, the maximum fine authorized under the defamation provisions of the Criminal Code, Rp300, is the equivalent of 3 US cents). Thus, as a practical matter, the only criminal penalties for defamation under the Criminal Code are imprisonment or a suspended jail sentence.

Law No. 11/2008 Regarding Electronic Information and Transactions

In 2008 Indonesia’s parliament, the Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat (DPR), enacted a sweeping new law regulating internet activity, known as the Law Regarding Electronic Information and Transactions (Undang-Undang Informasi dan Transaksi Elektronik or ITE law).[39] The ITE law provides a much-needed legal basis for internet-based commerce in Indonesia and also codifies a number of internet-based offenses, including various forms of cybercrime. The law also contains a provision criminalizing internet-based insult and defamation with noticeably stronger penalties than those contained in the defamation and insult provisions of the Criminal Code.

Under the ITE law an individual whose allegedly defamatory statements are communicated over the internet can be punished with up to six years’ imprisonment and can be fined up to Rp1 billion (approximately US$106,000 as of January 1, 2010). Under Indonesian law the police can authorize pre-trial detention only where a person is suspected of committing a crime that carries a penalty of at least five years’ imprisonment.[40] Thus, while individuals accused of defamation under the Criminal Code cannot be imprisoned unless they are tried and found guilty, individuals accused of defamation under the ITE law can be imprisoned, even in the absence of a trial, for up to 50 days, provided police investigators or prosecutors express “concern that the suspect … will get away, damage or destroy evidence materials and/or repeat the criminal act.”[41]

All three of Indonesia’s largest political parties, including President Yudhoyono’s Partai Demokrat, endorsed the ITE law during parliamentary debates in April 2008.[42] The deputy chairman of Indonesia’s Press Council, Leo Batubara, told journalists that the DPR had not asked for the council’s input on the law, and that he believed legislators had deliberately inserted the more severe defamation penalties into the draft.[43] He told Human Rights Watch, “Some of our leaders in the government and DPR still don’t like the idea of freedom of the press.”[44]

Constitutional Court rulings on Free Expression and Criminal Defamation

In 2008 and 2009, in decisions that diverged dramatically from its previous rulings on the “hate sowing” and lese majeste articles of the Criminal Code, the Indonesian Constitutional Court upheld the validity of both the criminal defamation and insult provisions of the Criminal Code, as well as the ITE law’s articles on defamation. The petitioners in the 2008 case challenging the Criminal Code provisions put forward the same arguments that had persuaded the court to overturn other criminal defamation provisions in previous years: that the articles were highly susceptible to abuse by those seeking to repress public criticism and had the potential to cause legal uncertainty.[45] The court, noting that the Indonesian constitution also safeguards the right to protect one’s honor and dignity,[46] declared that criminal defamation laws constituted a permissible restriction on freedom of expression intended to safeguard that competing right. Said the court, “[w]e cannot expect to achieve order in the social life or mutual life known as society if each person uses his/her freedom arbitrarily. In the foregoing context, restriction of freedom by laws is a must.”[47]

Departing from the reasoning employed in its earlier decisions on the “hate sowing” and lese majeste articles, the court declared that even if the criminal defamation provisions were highly susceptible to abuse, that was not a reason to invalidate the laws as such, but rather a problem involving “deviations in … law enforcement practices.”[48] The court further ruled that criminal penalties were not a disproportionate response to defamation, stating that proportionality is a matter which “depends on the values adopted by the community”[49] and that the incidence of defamation prosecutions was “not significant” compared to the number of corruption accusations published in the media.[50]

In its 2009 decision on the criminal defamation provisions of the ITE law, the court reiterated its reasoning in its 2008 Criminal Code decision, finding that the provisions constituted a justifiable restriction on freedom of expression intended to serve the equally important goal of safeguarding citizens’ right to protect their honor and dignity.[51] NGO representatives have expressed interest in petitioning the Constitutional Court for a second review of the criminal defamation provisions of the Criminal Code, but the prospects of success were unclear at this writing. In principle, of course, the Indonesian parliament could also repeal the laws or reform them in line with Indonesia’s international human rights obligations, but this is highly unlikely given that the parliament only recently demonstrated its full support for criminal defamation penalties by enacting the ITE law.

In addition to the recent troubling Constitutional Court decisions, Indonesia is considering a new draft penal code that some have warned could resurrect some of the most restrictive offenses of the old regime. The latest draft, not yet debated by parliament and the subject of ongoing controversy, is said to include the lese majeste and “hate-sowing” offenses previously invalidated by the Constitutional Court and the Suharto-era offense of “subversion.”[52]

III. Types of Behavior Criminalized by Indonesian Defamation Law

The officer even told me, “You cannot say something bad about someone in public, in front of lots of people. It doesn’t matter whether your statement is true or not. You cannot say that in public.”

—Usman Hamid, accused of defaming Maj. Gen. (ret.) Muchdi Purwopranjono at and following his trial for murder.

In recent years police and prosecutors have threatened or used Indonesian criminal defamation laws against NGO workers engaged in efforts to stamp out corruption and misconduct by public officials, individuals who aired consumer complaints and business disputes, individuals who requested information from or lodged complaints with the authorities, and journalists whose reports offended the subjects of their stories. These are all areas in which, while civil defamation penalties might be appropriate depending on what exactly was said by whom and with what intent, criminal investigation and imprisonment of the writer or speaker should never be the outcome.

Peaceful Protests against Corruption and Official Misconduct

In a number of cases investigated by Human Rights Watch, NGO activists who engaged in peaceful demonstrations or spoke publicly on issues of importance to Indonesian society subsequently became the targets of criminal defamation complaints. One emblematic example is the case of Illian Deta Arta Sari and Emerson Yuntho, employees of the respected Jakarta-based NGO Indonesia Corruption Watch.

In January 2009, at an ICW press conference, Illian fielded a question from an audience member about the track record of the Attorney General’s Office (AGO) on asset recovery in corruption cases. Illian, relying on an official audit by the country’s Supreme Audit Agency (Badan Pemeriksa Keuangan, or BPK), noted that the agency had identified “irregularities” in the financial statements of a majority of prosecutors’ offices.[53] Emerson and a colleague pointed out significant disparities between the value of assets the AGO had claimed to have recovered and the value of assets identified by the BPK audit.

Three days later the AGO filed a criminal defamation complaint against Illian and Emerson, relying on a newspaper’s coverage of the incident.[54] In October 2009, nine months later, the police summoned the pair for questioning on articles 311 and 316 of the Criminal Code.[55] Illian expressed frustration that there could be any possibility that her comments at the ICW press conference could be considered criminal under Indonesian law. “We believe we are right and our data is accurate,” she said. “We did no wrong.”[56] As already noted, the timing of the summons was also suspicious, given that it came months after the initial complaint but just days after ICW had criticized police and prosecutors for filing trumped-up charges against officials of Indonesia’s Anti-Corruption Commission.

Another example is that of Mohammed Dadang Iskandar, the director of Gunungkidul Corruption Watch (GCW), a local anti-corruption NGO in the Gunungkidul regency of the province of Yogyakarta. On July 30, 2009, Dadang coordinated a demonstration with several other local NGOs to protest the authorities’ lack of speed in investigating allegations they had made of corruption in the Gunungkidul legislature during the 1999-2004 term.[57] The protesters’ frustration also stemmed from the fact that a March 2005 BPK audit had revealed that 45 legislators during that term had received exceptionally large “benefits” allowances. Although the BPK had recommended that legislators return the funds, only a handful had done so.[58]

During the demonstration protestors raised banners displaying such statements as “please delay the inauguration of the newly elected” and “the members of the Gunungkidul legislature are robbers—they have stolen people’s money.”[59] Three days after the demonstration, three local legislators, including the current head, the deputy chairman from the 1999-2004 period, and a first-time legislator not implicated in the BPK audit, filed criminal defamation complaints against Dadang under articles 207 and 208 of the Criminal Code.[60] The police launched an investigation into the defamation complaints that remained ongoing as of April 2010.[61] Dadang told Human Rights Watch that his case is an example of how “[a] libel case can be a tool for the government to suppress and oppress people who want to criticize [it].”[62]

Dadang’s case is similar to that of Jamaludin bin Sanusi and Badruzaman, two representatives of the Coalition of Students and People of Tasikmalaya (Koalisi Mahasiswa dan Rakyat Tasikmalaya, or KMRT), and their advisor, Zamzam Zamaludin, who were tried on criminal defamation charges under articles 310, 311, and 315 of the Criminal Code from January to June 2009.[63] On July 23, 2008, the activists held a demonstration to protest the refusal of the chief of the Office of Education in Tasikmalaya, Abdul Kodir, to appear at local parliament hearings investigating allegations of corruption in his office—allegations KMRT had lodged in a formal complaint to local prosecutors. In protest, the KMRT members and a number of children marched, chanted, held signs carrying messages such as “freedom from corruption in education,” and placed a piece of paper on the door of the official’s office, symbolically proclaiming it “closed on behalf of the people.”

Despite the fact that the authorities began to investigate KMRT’s corruption charge against Kodir, they also quickly followed up on the criminal defamation complaint Kodir filed against the three KMRT members the day after their demonstration.[64] The KMRT members were put on trial on the defamation charges in January 2009, where prosecutors demanded that they be imprisoned for one year and four months, despite the fact that the investigation into the corruption charges against Kodir were ongoing. Six months later, in June 2009, the court acquitted the KMRT activists. However, prosecutors have appealed the verdict, and as discussed below, the lives and work of the KMRT members have been deeply affected by the charges against them. Zamzam, the chairman of KMRT, told Human Rights Watch, “When I began doing demonstrations, I didn’t think it was against the law. Reporting the corruption case is not criminal, but when I did that, I was prosecuted.”[65]

Even the most well-known NGO activists in Indonesia are not immune from criminal defamation charges, as the case of Usman Hamid demonstrates. In late 2004, Usman, coordinator of an NGO called the Commission for the “Disappeared” and Victims of Violence (Komisi untuk Orang Hilang dan Korban Tindak Kekerasan or KontraS), one of Indonesia’s leading human rights groups, was appointed to a presidential fact-finding team established to monitor and evaluate a police inquiry into the murder of KontraS founder Munir bin Thalib.[66] Based on the evidence collected by the fact-finding team and the police, prosecutors charged a senior official of the National Intelligence Agency (Badan Inteligen Negara, or BIN), with Munir’s murder, and brought him to trial in 2008. Usman testified on behalf of the prosecution, detailing evidence the fact-finding team had discovered that pointed to Muchdi’s involvement in the murder.[67] However, during the course of the trial, many current or former intelligence officers and members of the military called as witnesses retracted sworn statements they had previously provided to the police.[68] On December 31, 2008, the court acquitted Muchdi on all charges. Usman exited the courtroom and made a speech to spectators gathered outside which clearly indicated that he believed Muchdi had been wrongly acquitted.[69] The following week Muchdi’s lawyers filed a criminal defamation complaint against Usman on the basis of his courtroom testimony and his speech following the verdict. In late September 2009 police named him a suspect on charges that he violated articles 310 and 314 of the Criminal Code.[70]

Usman argues that the government should only prohibit peaceful expression if it is intended and likely to cause others to use violence and that the statements for which he faces criminal charges did not rise to this level. “I didn’t incite anybody to hate him or to kill him,” he says. “I didn’t say anything about violence. I said ‘I cannot accept this verdict. This is not a fair trial.’… I was doing my job. I was trying to find the truth. I was trying to fight for justice.”[71]

Publicizing Consumer Complaints and Business Disputes

Perhaps the most well-known criminal defamation case in Indonesia is that of Prita Mulyasari, the head of the customer care department at Bank Sinar Mas in Jakarta and the mother of two small children. Prita was prosecuted on criminal defamation charges for writing an email to friends in which she criticized two doctors who had treated her at a Omni International Hospital in Tangerang, a Jakarta suburb.

In August 2008 doctors had misdiagnosed Prita with dengue fever on the basis of a flawed platelet test and had asked her to be discharged so she could seek treatment elsewhere. However the hospital refused to provide her with a record of the flawed platelet test despite several requests from Prita and her husband. Frustrated, Prita sent her friends a long email about Omni and her doctors from the second hospital. In November her doctors saw the email online, after friends posted it on blogs and Facebook, and filed a criminal defamation complaint against her. Without warning, in May 2009 prosecutors placed her in pre-trial detention on the basis of the ITE law. Prita remained in prison for three weeks and was released only on the eve of her criminal trial. Her imprisonment led to outrage, and a Facebook campaign established in support of her cause eventually attracted over 137,000 members, elevating Prita’s status to that of a national icon.[72] Prita was tried, acquitted, retried, and then finally acquitted on December 29, 2009, although prosecutors have appealed the verdict. Prita, still incredulous, told Human Rights Watch in November 2009, “I sent a private email to friends about what really happened and suddenly I am made a criminal. I had to go to prison, I had to go to court, I had to go a second time, and it’s still happening.… I’m worried about the future…. I want to continue my life…. Now, I don’t know how to complain.”

Prita may have been acquitted of criminal defamation charges, but she is not the only dissatisfied consumer in Indonesia to have been accused of criminal defamation for publicly airing her grievances with a company. In 2005 Lim “Steven” Ping Kiat, then a trader at a Jakarta commission house, became the target of a criminal defamation investigation by the police after he wrote a letter to a newspaper criticizing a real estate company that he had retained years before to help him purchase his home. Steven claimed that when he had attempted to sell the house he had purchased with help from the company six years earlier, he was informed that there was a major error on the title documents. When the company refused to correct the mistake, he was forced to retain another real estate company and incurred significant expenses in the process. In his letter to the newspaper Steven criticized the company’s refusal to respond to his requests to cover half the costs he incurred in fixing the error. In response, the company filed a criminal defamation complaint against Steven.

Additionally, three criminal defamation defendants interviewed by Human Rights Watch were prosecuted after airing a business dispute: Fifi Tanang, Khoe Seng Seng, and Kwee “Winny” Meng Luan faced criminal charges after publicly accusing a real estate developer of misleading them when selling them the property. [73]

Fifi, the chairwoman of the tenants’ association of the Mangga Dua Apartment Complex, and Winny and Seng Seng, members of the tenants’ association at the nearby ITC Mangga Dua shopping center, said that when they had purchased their properties from the developer—Fifi’s apartment and Winny and Seng Seng’s small shops—they had been led to believe that their tenants’ associations would hold the rights to both the buildings and the land upon which they were constructed. However, in June 2006, the Indonesian national land registry (Badan Pertanahan National, or BPN) told Fifi that the land upon which both the apartment complex and the shopping complex sit had been developed pursuant to an agreement with the governor of Jakarta, and that the land had been and remained the property of the state.[74] When they publicized the issue in letters to local newspapers alleging fraud, the real estate developer responded by filing a criminal defamation complaint.

Following a two-year-long investigation, all three were tried on criminal defamation charges in November 2008 under articles 310, 311, and 335 of the Criminal Code. A Jakarta court convicted Fifi in May 2009 and sentenced her to one year of probation (a violation of which was to be punished with six months’ imprisonment). In July 2009 Seng Seng and Winny were also found guilty of defamation and given the same sentence. Winny told Human Rights Watch, “We’re more than 40 years old, and it’s the first time that we are involved with the law. We had never even been in a police station before, and then all of this happened.”[75] As detailed below, the case has had a significant and continuing negative impact on their lives.

Requesting Information from or Lodging Complaints with Authorities

Seeking information from authorities or reporting official misconduct can also lead to criminal defamation charges. In one example, journalist Jupriadi “Upi” Asmaradhana, formerly a correspondent with Metro TV, was tried on criminal defamation charges in Makassar, South Sulawesi, in 2009 for filing complaints about police behavior.[76]

In May 2008 Makassar District Police Chief Inspector General Sisno Adiwino had given two speeches in which he urged government officials to ignore Indonesia’s “Press Law,” which states that disputes with the press should be addressed through the right of reply or corrections and suggests that press misconduct should be addressed through fines on media companies rather than criminal charges against journalists. The police official urged government officials in Makassar to ignore these provisions and to immediately file criminal defamation complaints against journalists who “mocked” them or “tarnished the good image of the region.”[77]

In response Upi lodged complaints with the National Police Commission and Komnas HAM (Indonesia’s national human rights body), arguing that Sisno had threatened press freedom and encouraged disrespect for the law. Sisno, in turn, filed a criminal defamation complaint against Upi, stating that his complaints to the Police Commission and human rights bodies, and the subsequent public demonstration he and other journalists held in Makassar to protest the use of criminal charges against journalists, had insulted him and tarnished his reputation. In September 2009 Upi was acquitted on charges of violating articles 207, 310, 311, and 317 of the Criminal Code, but prosecutors have appealed the verdict.[78] As detailed below, even though he was acquitted, the case has had a dramatic impact on Upi’s employment, finances, and personal relationships.

In another case, Tukijo, a farmer in the Kulon Progo regency of Yogyakarta, unexpectedly found himself the subject of a criminal defamation complaint after he asked local authorities for information. Tukijo, whose farm has been in his family for seven generations, has no documents that prove his ownership of the land. In May 2009 the village chiefs in his regency completed a land assessment that had been ordered by the regent. Tukijo, fearing that government officials would rely on the assessment to deprive him of his land for a mining project in the area, approached a local official, Isdiyanto, at his home and asked him to disclose the results, and when he claimed he did not have the information Tukijo sought, a heated conversation resulted.[79]

Shortly thereafter, police contacted Tukijo, informing him that Isdiyanto had filed a criminal defamation claim against him pursuant to articles 310, 335, and 336 of the Criminal Code.[80] Following a trial, in early 2010, Tukijo was found guilty of defamation and sentenced to six months’ probation and a three-month suspended jail sentence.[81] While he was still a suspect on defamation charges, Tukijo expressed shock that his conduct could be considered criminal. He told Human Rights Watch, “I feel that I did nothing wrong. I think the government might be broken. Why should people asking questions be suspected like this?”[82]

Samsudin Nurscha of the Legal Aid Institute of Jojgakarta, Tukijo’s lawyer, said of his clients, Tukijo and Sugiyarno (another farmer who was questioned as a witness in the case), “They want to feel like the government is developing policy with their input. They want to be able to express their opinions and aspirations in the public sphere. [Indonesian law] protects freedom of speech and opinions. It is guaranteed by the state. But the police are refusing to accept this.”[83]

Bambang Kisminarso, a lawyer and the chairman of the Ponorogo, East Java chapter of the NGO Pijar Keadilan (Flame of Justice), and his son-in-law Naziri were briefly jailed after filing an election complaint. On April 3, 2009, less than a week before national legislative elections, Bambang and Naziri traveled to the nearby village of Blembem, within the district of Ponorogo, where they say they encountered two supporters of DPR candidate Edhie Baskoro Yudhoyono—President Yudhoyono’s son—distributing envelopes containing Rp10,000 (US$0.88), a sticker, and a picture of Edhie to villagers.[84] They took this to be done in an effort to gain votes for Edhie. After taking their pictures and questioning them, Bambang filed an official complaint with the district-level election supervisory committee (Panwascam).[85]

On April 6 police arrested Bambang and Naziri and took them to the provincial police headquarters in Surabaya, East Java. Police told them they had defamed Edhie (popularly known as Ibas) in violation of articles 310 and 311 of the Criminal Code and the ITE law.[86] At 3 a.m. the following morning, police abruptly released the men and returned them to Ponorogo. Naziri says that police told him in January 2010 that their investigation into the defamation claim was still in progress.[87] Bambang says of the incident, “It is just strange. What I cannot take is why I, who reported the case, was made a suspect.”[88]

Media Reporting on Sensitive Topics

Criminal defamation charges can also result from media reporting on subjects that are politically sensitive or that offend the subject of the report. In some cases state officials appear to have used criminal defamation laws in an attempt to punish people for engaging in the very scrutiny and public evaluation of state policies and official performance upon which democratic societies rely. For example, in March 2007, journalist Bersihar Lubis, who is based in Medan, wrote an opinion column for Tempo newspaper in which he criticized the attorney general for banning a high school history textbook because he believed the decision contravened principles guaranteed by the Indonesian constitution. Lubis told Human Rights Watch, “I thought the government’s act to ban the book was wrong and not good for the Indonesian people.”[89] Yet he found himself charged—and eventually convicted—under article 207 of the Indonesian Criminal Code for “insulting” the attorney general. Lubis said, “I write for the public good, but the government thinks of it as defamation. At the time, I thought, where is democracy?”[90]

In December 2004 Risang Bima Wijaya, then the general manager of the Yogyakarta newspaper Radar Jogja, was found guilty of criminal defamation and sentenced to six months’ imprisonment, which he served from December 2007 to June 2008, after his newspaper printed a number of articles critical of the executive director of another paper, who had been accused of sexually harassing a female staff member at the time the articles were written.[91] Risang claimed that other journalists had been apprehensive about reporting the staff member’s claim against the newspaper director because of his strong political connections. “I wrote about [the employee who brought sexual harassment charges] because no one else would write about her…. So I went to prison. I realize this [was] a consequence of my job,” he told Human Rights Watch.[92]

Three other news outlets faced criminal defamation charges for their reporting on the alleged election vote-buying detailed above. At 10 p.m. on April 6, 2009, East Java Police Chief Insp. Gen. Anton Bachrul Alam announced at a press conference in Surabaya that the Jakarta Globe, Okezone.com, and Harian Bangsa were suspected of criminally defaming Edhi Baskoro Yudhoyono in violation of articles 310 and 311 of the Criminal Code.[93] This was based on articles the three news outlets had published that morning reporting the election complaint filed by Bambang Kisminarso and Naziri. The news came as a shock to Abdurahman, the chief editor of Harian Bangsa, who told Human Rights Watch, “Our report was not exclusive. All papers were reporting it. It was ordinary news!”[94] However, it came as less of a shock to Camelia Pasandaran, the author of the Jakarta Globe article on the election complaint. According to her husband, plainclothes police officers had questioned her that morning in a Jakarta hotel about her article.[95]

The charges against the newspapers proved to be short-lived, as only a matter of hours later, at approximately 3 a.m. on April 7, the police chief held another press conference to announce that the charges against the three news outlets had been dropped.[96] However, the experience was enough to shake both Camelia and her husband, who works as a reporter for Tempo. He told Human Rights Watch, “[Camelia’s] facts were clear, she covered both sides. So the news itself had no bias. The problem is that even if we are very sure that we are doing what our profession requires, because of this defamation law, we can still be brought to court.”[97]

IV. Inadequate Legal Safeguards and Irregularities in the Enforcement of Criminal Defamation Law

As the preceding chapter demonstrated, criminal defamation laws in Indonesia effectively criminalize several types of conduct that are critical to the proper functioning of a democratic society. Indonesian law enforcement officials and legislators have articulated a number of official policies and enacted laws that are intended to protect consumer and anti-corruption “whistleblowing” and media freedom. However, in several cases Human Rights Watch investigated, these legal and policy measures proved inadequate to address the threat to free expression posed by defamation laws, even when they were brought to the attention of law enforcement officials.

Additionally, in other cases that Human Rights Watch investigated, authorities who carried out criminal defamation investigations behaved in ways that suggested bias, as when police and prosecutors failed to follow standard procedures intended to safeguard suspects’ due process rights.

Police Policy Regarding Criminal Defamation Complaints against Anti-Corruption Whistleblowers

One document that appears to be intended to address some of the risks to freedom of expression posed by criminal defamation law in Indonesia is a 2005 memorandum sent by Brig. Gen. Indarto, SH, director of the Criminal Investigation Bureau of the National Police, to all district police chiefs in Indonesia. The memorandum acknowledges that officials accused of corruption may retaliate by filing criminal defamation complaints against anti-corruption whistleblowers and urges police to prevent their investigation of defamation complaints from distracting them from properly investigating the underlying corruption allegations.

Indarto’s memorandum, which appears to have the status of a policy statement by the national police, was issued in response to a request by Indonesia’s anti-corruption commission (Komisi Pemberantasan Korupsi, or KPK), which was seeking witness protection for an NGO that was being prosecuted for criminal defamation after having accused officials at a state agency of corruption. Indarto’s memorandum notes that at both the federal and provincial level, “officials who have been reported to engage in corruption, have retaliated by reporting the informant to the Indonesian National Police (Polri) for defamation,” and that such defamation charges have the potential to distract attention from corruption investigations.[98] In the memorandum, Indarto states that handling corruption cases “should always be the main priority,”[99] and specifies that defamation claims should be handled “with the aim that those cases do not [obscure] the handling of corruption that is the main issue of the case.”[100] While Indarto’s memorandum does not prohibit police from investigating criminal defamation complaints filed against “whistleblowers” prior to the resolution of underlying corruption allegations, it demonstrates that the Indonesian police are aware that criminal defamation claims can be used to attack whistleblowers and reminds police officials that their investigation of corruption claims should take priority.

In at least one criminal defamation complaint investigated by Human Rights Watch, the police appeared to be adhering to this policy, despite some initial uncertainty. In Ponorogo, East Java, Sunardi, the head of local anti-corruption NGO Laksar Wengkar, said that the police investigation into a criminal defamation claim against him has been put on hold while authorities investigate the underlying corruption allegations Sunardi made that gave rise to the defamation complaint.[101] In 2008 Sunardi gave a speech at an anti-corruption demonstration in which he discussed the results of an investigation his organization had undertaken. In his speech Sunardi claimed that the local government had violated fair tender requirements in awarding a contract to produce school textbooks to a local publishing company.[102] Shortly thereafter the president of the company demanded that Sunardi apologize for his remarks, and when Sunardi refused, he filed criminal defamation charges against him.

Sunardi told Human Rights Watch that the police initially questioned him on the defamation charges without attempting to determine whether or not his graft claims were true, and that they tried to submit his file to local prosecutors on three separate occasions.[103] At the time Sunardi was frustrated with the conduct of the police, asking, “Why are those responsible not being questioned and those who ask questions are?”[104] However, in February 2010, Sunardi told us that police said they intended to fully investigate his corruption allegations before proceeding with investigation of the defamation claim. Police also told him that if his corruption allegations were determined to be well-founded, they would close the investigation into the defamation claim.[105]

In other cases we looked at, however, police did not adhere to the policy outlined in Indarto’s memorandum. In Tasikmalaya, for example, members of KMRT, the student group whose members were accused of defamation by a local education official after they held a protest outside his office, had alleged in 2008 that the education official had engaged in corruption, reporting him to prosecutors and to the local parliament. The local parliament had requested the official to participate in hearings investigating the allegations three times during the summer of 2008, but the official had refused to attend them, and KMRT held its protest in response to his refusal. The official retaliated against KMRT by filing a criminal complaint which was vigorously pursued by both police and then prosecutors.

The three KMRT activists were put on trial for defamation beginning in January 2009, despite the fact that an investigation into their corruption claims was ongoing. In May 2009 five months into the KMRT members’ trial, the Indonesian Victim and Witness Protection Agency (Lembaga Perlindungan Saksi Dan Korban, or LPSK), petitioned the judge overseeing the case to dismiss the charges against the KMRT members, saying that the crime they had reported had not been fully investigated.[106] While the judge acquitted the KMRT workers in June 2009, he made no mention of the LPSK request.[107] Since that time prosecutors have declared the local education official a suspect on corruption charges, but they have also appealed the KMRT workers’ acquittal on defamation charges.[108]

The criminal defamation case brought against the KMRT workers exemplifies the risks of criminal defamation claims to anti-corruption whistleblowers highlighted in Indarto’s memorandum. Here, authorities devoted a great deal of time and resources to investigating and prosecuting the defamation charges against individuals who reported corruption, allowing the defamation claim against them to become “a distraction” to the corruption allegation. If police had followed the approach outlined in Indarto’s memorandum, they would have had reason to suspend their investigation into the criminal defamation charges against the KMRT members. Instead, at the time of writing, the members of KMRT had endured more than 18 months in Indonesia’s criminal justice system and faced an ongoing appeal process.

The Press Law

Indonesian legislators also attempted to safeguard the right to freedom of expression by enacting Law No. 40/1999, commonly known as the Press Law, shortly after Suharto’s ouster. The Press Law aims to safeguard freedom of the press in Indonesia, and while it does not explicitly state that journalists should not be charged with criminal defamation, a Supreme Court decision suggests that the law should generally be interpreted in that manner.

In 2006 Indonesia’s Supreme Court appeared to confirm that the Press Law overrides the criminal defamation provisions of the Criminal Code in at least some situations. In a widely reported case it overturned the criminal defamation conviction and one-year prison sentence levied against Bambang Harymurti, the corporate editor-in-chief of one of Indonesia’s most well-respected media outlets, Tempo.[109] In its decision, the Supreme Court found that the lower court in Harymurti’s case should have relied on the Press Law, and not the defamation provisions of the Criminal Code, and that as a general rule, journalists should be protected by the Press Law from criminal defamation charges as long as they abide by journalistic ethics.[110] However, the court’s decision did not go so far as to declare that journalists should never be found guilty of criminal defamation. This ambiguity, combined with features of Indonesia’s legal system, which does not award Supreme Court decisions with precedential effect, gives police, prosecutors, and judges some latitude to continue to apply criminal defamation laws against journalists.[111]

In two of the defamation cases against journalists discussed in chapter III above, authorities refused to apply the Press Law and applied the criminal law instead.[112] Bersihar Lubis, who wrote an opinion column for Tempo in which he criticized an official decision of the attorney general, was convicted and sentenced to probation and a suspended jail sentence on the basis of the Criminal Code. The court in his case found that the Press Law, which generally states that the management of a publication, and not individual journalists, should be held responsible for published material, did not apply in his case because it was an opinion piece, and thus expressed the individual views of the author, rather than those of the media publication.[113] Bersihar told Human Rights Watch, “Media shouldn’t face the Criminal Code. The press shouldn’t be criminalized, [but the] Press Law is not strong enough to protect journalists in Indonesia like me.”[114]

Similarly, police, prosecutors, and judges all refused to apply the Press Law to Risang Bima Wijaya, then general manager of the Yogyakarta-based newspaper Radar Jogja, after Radar Jogja published a series of articles critical of the executive director of another paper, who then filed a complaint. Risang says that had the Press Law been applied, the most severe penalty would have been a fine levied on the editor-in-chief or the newspaper itself. Instead, Risang, who was only the general manager of the paper, was sentenced to, and served, nine months in prison.[115]

Thus, while the Press Law occasionally operates to safeguard the right to freedom of expression for journalists and to protect them from criminal defamation charges, it is insufficient to fully protect them. As a result, despite parliament’s intention to encourage media freedom, journalists and editors remain exposed to the risk of criminalization for doing their work.

The Consumer Protection Law

Another law which legislators enacted in an effort to protect the right to freedom of expression in Indonesia is the 1999 Consumer Protection Law. Article 4 of the law provides that consumers have a right to express their opinions and to have complaints about goods and services heard, and emphasizes that advocacy and dispute resolution efforts “are worthy of consumer protection.”[116] At least one government agency has specifically invoked the law on behalf of an individual accused of criminal defamation for expressing negative opinions about commercial services. While the existence of the law shows Indonesian lawmakers feel that consumer opinions and complaints should be protected, two cases investigated by Human Rights Watch demonstrate that the law does not provide a reliable defense to defamation charges.[117]

For example, in 2005, police questioned Lim “Steven” Ping Kiat, then a trader at a Jakarta commission house, on charges that he violated article 335 of the Criminal Code. Steven had purchased his Jakarta home through the subsidiary of a transnational real estate company, but when he tried to sell the home he realized that his title certificate did not list the correct address.[118] The company refused to correct the mistake, so Steven hired another real estate company to do so and sought to recoup half the cost from the original company (Rp3.5 million, or approximately US$380.00). When the subsidiary refused to respond, Steven wrote a letter criticizing it that was soon published in three newspapers.[119] Thereafter, the company filed a criminal defamation complaint against Steven, and police began to investigate the case, apparently disregarding the Consumer Protection Law.[120] Two years later, in 2007, after the police investigation had been closed, Steven received a copy of a letter that a government agency had sent on his behalf to the company, arguing that the Consumer Protection Law protected Steven’s right to write the letter to the editor.[121]

Prita Mulyasari’s case, already detailed above, provides another example: she was detained and prosecuted twice on criminal defamation charges in 2009 after she sent an email to friends criticizing a hospital and its doctors for poor service. Tulus Abadi, the chairman of the Indonesian Consumers Foundation (Yayasan Lembaga Konsumen Indonesia, or YLKI), agreed, telling the Jakarta Post in June 2009, on the eve of Prita’s first trial on criminal defamation charges, “this sets a bad precedent for consumers, since the right to complain is protected under Law No. 8/1999 on Consumer Protection.”[122]

Conflicts of Interest and Procedural Irregularities

In some of the criminal defamation cases Human Rights Watch investigated that were initiated by government officials or wealthy individuals or companies, we found that conflicts of interest existed, violations of standard police procedures had taken place, or the authorities had acted in an improper or intimidating manner that suggested bias or ulterior motives. These incidents illustrate the potential for misuse of criminal defamation law as a tool for retaliation rather than as a mechanism for redress where genuine injury has occurred.

In some cases, the people who carried out the subsequent investigations into the criminal defamation allegation included the complainants’ subordinates. In others, the investigators that followed up on defamation claims filed by public officials may not have reported directly to the complainants, but the fact that the complainant was a high-profile public official could likely have affected the subsequent response by law enforcers. In one example, in Makassar, the police chief brought criminal defamation charges against journalist Jupriadi “Upi” Asmaradhana and then ordered his subordinates to investigate the charges. Other powerful officials who filed criminal defamation complaints in the cases Human Rights Watch investigated include the attorney general and the son of Indonesia’s president. These potential conflicts do not establish bias on their own. However, the investigations undertaken in response to several of these claims were also characterized by improper conduct on the part of the authorities.

For example, Upi Asmaradhana told Human Rights Watch that after the Makassar police chief filed a criminal defamation complaint against him, he was terrorized by threatening SMS messages and anonymous telephone calls while his subordinates were investigating the defamation claim against him.[123] He also alleged that police officers told his lawyers during the investigation that they had wiretapped his mobile phone.[124] When his case file was turned over to the prosecutor’s office, he received a warning that police intended to arrest him and place him in pre-trial detention.[125] As a result, he briefly went into hiding until a higher ranking police official intervened and prevented his arrest.[126]

Another instance in which police engaged in apparently improper behavior was the series of investigations that followed the filing of an election complaint against Edhie Baskoro Yudhoyono’s campaign team by Bambang Kisminarso and his son-in-law Naziri in Ponorogo, East Java. Police officers charged Bambang and Naziri not only with violating the criminal defamation provisions of the Criminal Code, but also with violating the ITE, despite the fact that there was no evidence to suggest that Bambang or Naziri had placed any defamatory material on the internet. This is significant because individuals accused of defamation under the Criminal Code cannot be placed in pre-trial detention because none of the offences in it are punishable by more than five years’ imprisonment. However, because the ITE authorizes imprisonment for up to six years, those accused of violating it can be arrested, provided police determine they are likely to tamper with evidence, repeat their offense, or flee.

Police arrested Bambang and Naziri early in the morning on April 7, and while the arresting officers permitted the men to see a copy of what they claimed to be a warrant for their arrest, they were not given copies of the document at any point during their detention.[127] When they were suddenly released from custody early the next morning, they were provided with no explanation or documents explaining what had transpired. On his own initiative Naziri approached the Ponorogo police the following week and requested a copy of the document he had been shown upon his arrest.[128] While the chief of police in Surabaya publicly declared that both men had been declared suspects on criminal defamation charges at a press conference while they were still in detention,[129] neither man ever received written notice from the police to that effect. On two occasions since the arrest, October 2009 and January 2010, Naziri has inquired with the police about the status of the investigation, and both times, he was informed that it is ongoing.[130]

Additionally, shortly after Camelia Pasandaran wrote an article reporting on the election complaint filed against Edhie Baskoro Yudhoyono’s campaign team, the case described in chapter III above, she was unexpectedly taken to a hotel room to be questioned about the sources she consulted in writing her piece by men who identified themselves as police officers but who were not wearing uniforms and did not present her with official identification.[131] Camelia was not told on what basis she was being questioned or whether she had been accused of criminal defamation.

Camelia’s husband, Tempo reporter Oktamandjaya Wiguna, strongly objected to the conduct of the police, which he said was intimidating and not in line with proper procedures. He argued that under the Press Law, the police had no right to question Camelia.[132] Instead, if Edhie Baskoro Yudhoyono objected to the content of Camelia’s report, he should have petitioned her employer, the Jakarta Globe, for the chance to exercise a right of reply or for a correction. He argues that the police should only have become involved in the dispute if such measures failed, and that in any case, Camelia should have been given advance warning about the police desire to question her, and that she should have been questioned by uniformed officers, at a police station, and been given the opportunity to have a lawyer with her.[133] He told Human Rights Watch, “Media situations should involve the right of reply, but Camelia’s story was published on April 6 and she was interviewed on April 7. This is not the correct way.” He says that if he had known that the police intended to question Camelia under such conditions in advance, he would have told her not to comply with their request and to demand that they summon her for questioning as a witness according to proper procedures. However, because neither of them was given advance warning, Camelia found herself in a circumstance in which she did not feel that she could refuse to be questioned.[134]