Map of Guinea

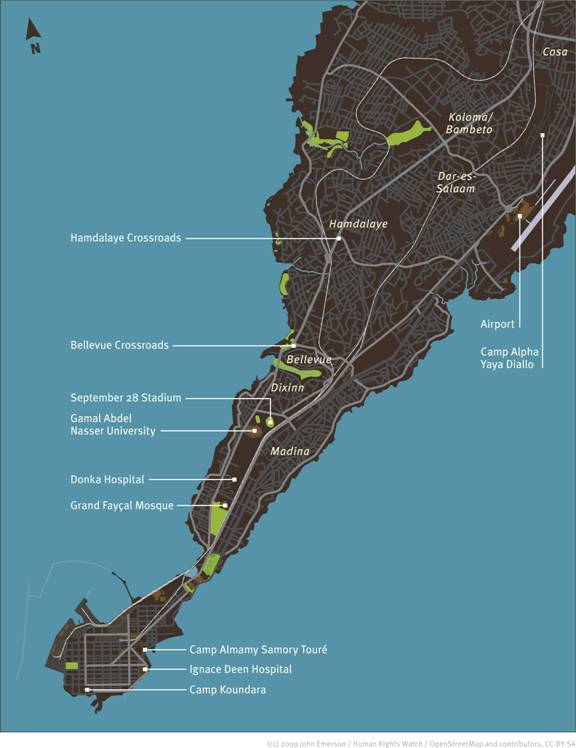

Map of Conakry

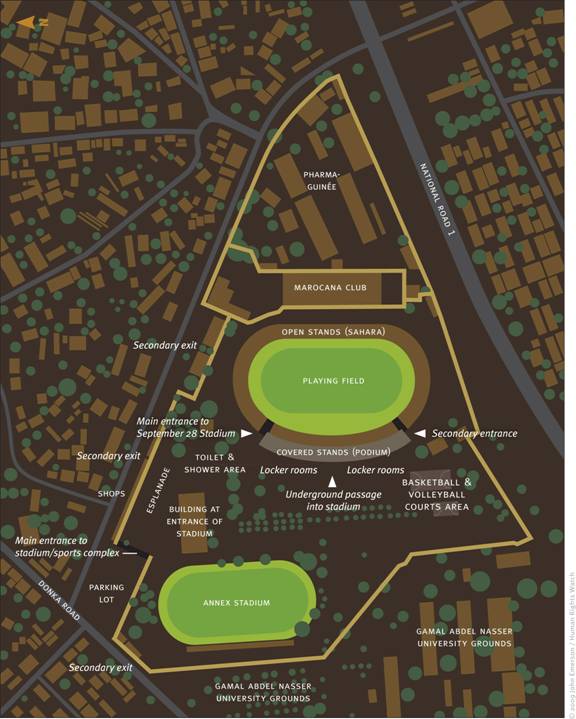

Map of the September 28 Stadium and Surrounding Area

Summary

At around 11:30 a.m. on the morning of September 28, 2009, several hundred members of Guinea’s security forces burst into the September 28 Stadium in Guinea’s capital, Conakry, and opened fire on tens of thousands of opposition supporters peacefully gathered there. By late afternoon, at least 150 Guineans lay dead or dying in and around the stadium complex.

Bodies were strewn across the field, crushed against half-opened gates, draped over walls, and piled outside locker rooms where doors had been pulled shut by the terrified few who had gotten there first. Dozens of women at the rally suffered particularly brutal forms of sexual violence at the hands of the security forces, including individual and gang rape and sexual assault with objects such as sticks, batons, rifle butts, and bayonets. At least four women and girls were murdered during or immediately after being raped; one woman was shot with a rifle through her vagina while laying face up on the stadium field begging for her life.

In the hours and days following the violence, as desperate mothers, fathers, and other family members attempted to find their loved ones, the security forces engaged in an organized cover-up to hide the number of dead. After sealing off the stadium and morgues, security forces removed scores of bodies from those places and buried them in mass graves. For several days, additional abuses—including murder, rape, and pillage—were committed by members of the security forces who had deployed throughout the neighborhoods from where the majority of opposition supporters hailed. Scores of other opposition supporters were arbitrarily detained in army and police camps where many were subjected to serious abuses, including torture. To date, the Guinean government has failed to investigate, much less hold accountable, any member of the Guinean security forces for their role in the killings, rapes, and other abuses.

In the course of an in-depth, on-the-ground investigation into the events of September 28 and their aftermath, Human Rights Watch interviewed some 240 individuals, including victims wounded during the attack, witnesses present in the stadium, relatives of missing people, soldiers who participated in the violent crackdown and the government cover-up, medical staff, humanitarian officials, diplomats, journalists, and opposition leaders. The investigation found that the majority of killings, sexual assaults, and other abuses described in this report were committed by members of the elite Presidential Guard, in particular the unit at the time directly responsible for the personal security of CNDD President Moussa Dadis Camara. Others who committed serious abuses included gendarmes, police, and men in civilian clothes armed with machetes and knives.

The serious abuses carried out by the security forces on September 28 were not the actions of a group of rogue, undisciplined soldiers, as has been argued by the Guinean government. The dearth of any apparent threat or provocation on the part of the demonstrators, in combination with the organized manner in which the security forces carried out the stadium attack—the simultaneous arrival at the stadium of different security units, the coordinated manner of deployment to strategic positions around the stadium in anticipation of the fleeing demonstrators, the failure to use non-lethal means of crowd dispersal, and the presence of officers, including a minister tasked with security responsibilities—suggests that the crimes were premeditated and organized.

The evidence gathered by Human Rights Watch suggests that the killings, rapes, and other abuses committed by the security forces on and after September 28 rise to the level of crimes against humanity. The scale and organization of these crimes strongly suggest that they were both widespread and systematic. As such, the principle of “command responsibility” applies to military commanders and others in position of authority who may be criminally liable for crimes committed by forces under their effective command and control.All those responsible, including those who gave the orders, should be held criminally accountable for their actions, as should anyone who participated in efforts to cover up the crimes and dispose of any evidence.

In a significant display of international revulsion uniting African and other governments as well as regional and international bodies, important international actors—including France, the United States, the European Union, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), the African Union, and the United Nations—harshly denounced the September 28 violence in Guinea. This was followed by the imposition of arms embargos by ECOWAS and the European Union; travel bans and asset freezes of CNDD members by the EU, the US, and the African Union; and the withdrawal or cancellation of economic and military assistance from the EU and France.

The international community has been equally definitive about the need for those responsible for the September violence to be held accountable. As a result, an African Union and ECOWAS-proposed international commission of inquiry was on October 30 established by UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon. The prosecutor of the International Criminal Court on October 14 confirmed that it had initiated a preliminary examination of the situation. Unfortunately, continued economic and diplomatic support for Guinea from China and Libya mars the otherwise unified international response.

Based on the evidence presented in this report, Human Rights Watch recommends that the Guinean government immediately suspend from their duties and promptly investigate, prosecute, and punish in accordance with international standards the security officials believed to be most responsible for the killings, sexual violence, and other abuses committed during the September violence. Human Rights Watch further recommends that the Guinean government acknowledge a more accurate death toll from the September events and facilitate the exhumation, identification, and return to family members of the bodies disposed of by the security forces.

Guinea’s international partners should maintain the demand for accountability and support international efforts to prosecute these crimes if the Guinean authorities fail to meet their obligations to hold accountable those responsible. Lastly, Human Rights Watch calls on the UN secretary-general to promptly make public the report of the international commission of inquiry into human rights violations associated with the September 28 violence, and ensure that its findings are discussed and implemented.

Massacre, Sexual Violence, and Cover-Up

A bloodless coup in December 2008 by a group of military officers following the death of Guinea’s long-time authoritarian president Lansana Conté brought initial hope that it would usher in a period of greater respect for human rights. The coup government, calling itself the National Council for Democracy and Development (Conseil national pour la démocratie et le développement, CNDD) was led by a self-proclaimed president, Captain Moussa Dadis Camara, who pledged to hold elections in 2009 in which neither he nor any other member of the CNDD would run. When, later in 2009, he reversed that pledge, Guinean opposition parties and civil society responded by planning demonstrations across the country. The biggest of these was planned for September 28, 2009, in Conakry, culminating in the rally at the September 28 Stadium.

From the early hours of September 28, tens of thousands of opposition supporters walked toward the stadium from the capital’s suburbs. Security forces made several attempts to stop the unarmed demonstrators from proceeding to the stadium, including by firing live ammunition into groups of marchers. In response to one such incident, marchers ransacked and set on fire a police station, and wounded one police officer. When political opposition leaders entered the stadium at around 11 a.m., they found it packed with tens of thousands of supporters chanting pro-democracy slogans, singing, dancing, and marching around the stadium’s race course carrying posters and the Guinean flag.

Just before 11:30 a.m., a combined force of several hundred Presidential Guard troops, together with gendarmes working for the Anti-Drug and Anti-Organized Crime Unit, some members of the anti-riot police, and dozens of civilian-clothed irregular militiamen arrived at the stadium area. After quickly deploying around the stadium perimeter and positioning themselves near the stadium exits, anti-riot police fired tear gas into the stadium, causing widespread panic. Minutes later, the security forces, led by the Presidential Guard, stormed through the stadium entrance, firing directly into the packed and terrified crowd. Numerous witnesses described the gunmen “spraying the crowd from left to right” until they had emptied the two clips of ammunition many of them carried.

One group of soldiers advanced slowly down the stadium’s playing field as they fired, leaving a trail of injured and dead in their wake. A second group headed for the stands and attacked the opposition party leaders and their associates gathered there, beating some of them so severely that they lost consciousness. Many other soldiers blocked the exits both from inside and outside the stadium.

Witnesses described how the panicked demonstrators were gunned down as they attempted to scale the stadium walls; shot point blank after being caught hiding in tunnels, bathrooms, and under seats; and mowed down after being baited by disingenuous soldiers offering safe passage. Since most of the stadium exits were blocked by the attackers, there was scant opportunity for escape for the trapped protesters, and many were crushed to death inside the stadium by the panicked crowd. Outside the main stadium, on the sports complex grounds, many more opposition supporters were shot, knifed, or bayoneted, often to death, as they tried to escape. Hospital and humanitarian organization records confirm that more than 1,400 persons were wounded during the attack.

Human Rights Watch has not found any evidence that any member of the security forces was wounded or killed inside the stadium or sports complex, demonstrating the one-sided nature of the violence perpetrated by the security forces against the unarmed opposition supporters.

Sexual assaults began minutes after the security forces stormed the stadium gates. Human Rights Watch researchers interviewed 28 victims of sexual violence and documented many more cases from witnesses to the assaults. Of the 28 victims, 18 had been raped by more than one perpetrator. It is not known how many women were raped. A coalition of health and human rights groups had, as of mid-October, identified 63 victims of sexual violence, but given the profound stigma attached to victims of sexual violence in Guinea’s conservative, largely Muslim society, it is widely believed that many women have not come forward for medical treatment or other support.

Victims and witnesses described how members of the Presidential Guard cornered or chased down the panicked women as they fled the hail of gunfire. Women trying to scale fences were pulled down or forced to descend under threat of being shot. Those found hiding under stadium chairs were violently pulled out. After overpowering their victims, the perpetrators ripped or cut off their clothes with a knife, pinned their victim to the ground or across the stadium seats, and raped her in quick succession.

The sexual assaults were most often accompanied by degrading insults, death threats, and extreme physical brutality. The victims described being kicked, pummeled with fists, and beaten with rifle butts, sticks, and batons before, during, and after the sexual assault. Many victims showed Human Rights Watch their bruises; knife wounds on their back, buttocks, and extremities; and fingernail marks on their thighs, wrists, and abdomen. During the sexual assaults against girls and women of Peuhl ethnicity, assailants frequently made ethnically biased comments, insulting and appearing to threaten the Peuhl in particular.

Numerous witnesses described groups of up to 10 girls and women being raped simultaneously on the field and elsewhere in the stadium complex. The Presidential Guard also took many women from the stadium and, in the one case from a medical clinic where they were awaiting treatment, to private residences where they endured days of gang rape. The frequency and number of sexual assaults that took place during and after the protests suggests that it was part of a widespread and organized pattern of sexual abuse, not isolated and random acts by rogue soldiers.

Human Rights Watch found strong evidence, including eyewitness accounts by confidential military sources and medical personnel, that the military engaged in a systematic effort to hide the evidence of their crimes and misrepresent the number of individuals killed during the events of September 28. The government reported the official number of dead to be 57. Human Rights Watch’s investigation found that the actual death toll of the violence on September 28 and the following days is likely to be between 150 and 200.

Beginning immediately after the massacre, members of the Presidential Guard closed off the stadium to medical personnel and over the next several hours removed bodies from the stadium complex in military trucks. Within 24 hours of the stadium violence, the Presidential Guard also took control of the two main morgues in Conakry, at Donka and Ignace Deen Hospitals, and removed bodies for burial in both known and unknown locations. Human Rights Watch spoke with the families of more than 50 persons who were known to have died during the September 28 massacre. In more than half of the cases, the body of the deceased person had never been recovered, and was believed to have been removed by the military directly from the stadium or from the morgues of the hospital.

Human Rights Watch spoke with one source who saw 65 bodies at Conakry’s Almamy Samory Touré military camp that were later removed in the middle of the night, allegedly to be buried in a mass grave. Another source described seeing Presidential Guard troops removing bodies from Donka Hospital in the early morning hours of September 29 and burying them in two mass graves in and around Conakry.

Abuses after the Stadium Violence

In the hours and days after the stadium violence, heavily armed soldiers dressed in camouflage and wearing red berets, and civilians armed with knives, machetes, and sticks, committed scores of abuses in neighborhoods in which the majority of participants in the September 28 rally lived. In some cases, the soldiers and armed civilians appeared to be collaborating to commit abuses. The neighborhoods in which there were attacks, notably Dar-es-Salaam, Hamdalaye, Koloma, Bomboli, and Cosa, are widely considered to be opposition strongholds, and are dominated by residents who are of the Peuhl and Malinké ethnic groups. Numerous victims and witnesses to violence in these neighborhoods told Human Rights Watch how, in the course of the attacks, the soldiers and irregular militia killed, raped, vandalized, and stole from residents. They also repeatedly insulted and made threats against people of Peuhl ethnicity in particular.

Security forces arbitrarily detained scores of men as they fled the stadium, and, to a lesser extent, in the course of the neighborhood attacks that followed, and subjected them to serious forms of mistreatment, including torture. Most were robbed and beaten, sometimes severely, at the time of detention. The worst abuses and longest periods of detention occurred at the Koundara and Alpha Yaya Diallo military camps. In these camps, former detainees described being subjected to frequent beatings with batons, guns, and other instruments; whipping; forced nudity; stress positions; and mock executions. Of the 13 men interviewed by Human Rights Watch who had been detained in at least one of four detention centers, not one had been questioned, interrogated, or formerly arrested, and most were obliged to pay the policemen, gendarmes, or soldiers holding them to secure their release.Detainees were generally given no medical treatment and little food or water during their detention.

Recommendations

To the Government of Guinea

- Provide full cooperation and unhindered access to the international commission of inquiry proposed by the Economic Community of West African States in September, and established by United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon in October.

- Immediately suspend from their duties and promptly investigate the security officials believed to be most responsible for the crimes committed on and in the days after September 28, 2009, including the officials named in this report.

- Investigate, prosecute, and punish in accordance with international fair trial standards members of the security forces against whom there is evidence of criminal responsibility for these crimes—such as murder, rape, assault, and torture—including those liable under command responsibility for their failure to prevent or prosecute these crimes.

- Fully cooperate with the restrictions imposed on Guinean officials by the African Union, ECOWAS, the European Union, and the United States, including:

- Arms embargos imposed by ECOWAS on October 17 and by the EU on October 27;

- Travel and visa restrictions imposed by the US on October 23, by the African Union on October 23, and by the EU on October 27; and

- An asset freeze imposed by the EU on October 27.

- Ensure that witnesses and others who have information about crimes committed during the September violence are adequately protected from intimidation, threat, or violence.

- Immediately release any remaining people detained without charge following the September violence, or immediately charge them with specific criminal offenses followed within a reasonable timeframe by a fair trial.

- Facilitate the exhumation, identification, and return to family members of the bodies disposed of by the security forces in the immediate aftermath of the September 28 violence, including those bodies taken from the stadium and morgues at Donka and Ignace Deen Hospitals to be buried in mass graves.

- Adequately and speedily compensate victims of the September 28 violence and its aftermath, including family members and dependents of those killed.

- Ratify the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa, signed by Guinea in July 2003, which obligates states to protect women from all forms of violence, especially sexual violence, and to enact and enforce laws to protect women from sexual violence.

- Ensure that the National Observatory for Democracy and Human Rights (Observatoire national de la démocratie et des droits de l’homme, ONDH)—mandated to investigate human rights abuses and conduct human rights education—is fully operational, funded, and allowed to function independently.

- Thoroughly review—and, as necessary, revise—the training curriculum for police and other security forces to ensure comprehensive training on human rights issues, including legal and appropriate interrogation and detention practices, and minimum use of force for crowd control. Provide comprehensive training for police officers on the conduct of investigations into alleged illegal use of force and abuse by security forces. All training should be consistent with international human rights standards, such as the UN Code of Conduct for Law Enforcement Officials and the UN Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials.

To the African Union, the Economic Community of West African States, and the European Union

- Demand accountability for the killings, sexual violence, and other abuses committed on and after September 28, and support international efforts to prosecute the crimes if Guinean authorities fail to meet their obligations to hold accountable those responsible for these crimes.

- Call publicly and privately on the Guinean government to ensure that witnesses and others who have information about crimes committed during the September violence are adequately protected from intimidation, threat, or violence.

- Assist the international commission of inquiry by providing them full access to information collected by member states, including intelligence information on the September 28 violence and its aftermath.

- Assist the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights in ensuring that adequate measures are in place to protect witnesses to the September violence who cooperate with the international commission of inquiry, including by monitoring any actions by the Guinean authorities that threaten witnesses and by assisting with the evacuation and relocation of threatened witnesses if necessary. Provide asylum to threatened witnesses if necessary.

- Fully cooperate with the restrictions imposed on Guinean officials by the African Union, ECOWAS, the European Union, and the United States, including:

- Arms embargos imposed by ECOWAS on October 17 and by the EU on October 27;

- Travel and visa restrictions imposed by the US on October 23, by the African Union on October 23, and by the EU on October 27; and

- An asset freeze imposed by the EU on October 27.

- Provide financial and other support to Guinean nongovernmental organizations to improve the monitoring and documentation of abuses committed by security forces and to undertake advocacy at a national and international level.

To United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon

- Promptly make public the report of the international commission of inquiry into human rights violations associated with the September violence in Guinea, and ensure that its findings are discussed and implemented.

- Demand accountability for the killings, sexual violence, and other abuses committed on and after September 28, and support international efforts to prosecute the crimes if Guinean authorities fail to meet their obligations to hold accountable those responsible for these crimes.

- Call publicly and privately on the Guinean government to ensure that witnesses and others who have information about crimes committed during the September violence are adequately protected from intimidation, threat, or violence.

- Establish and adequately staff a field presence of the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights to ensure the monitoring and documentation of:

- Any acts of intimidation against witnesses and others who have information about crimes committed during the September violence; and

- Violations of civil and political rights in the run up to the elections planned for 2010, including any restrictions that hamper the ability of individuals to associate freely, the ability of political parties and their supporters to organize and campaign, and the ability of the press to freely report on electoral developments.

To the United Nations Security Council

- Encourage continued engagement by the UN secretary-general and the UN Human Rights Council on the situation in Guinea.

- Support the establishment of a human rights field operation in Guinea.

To the United Nations Human Rights Council

- Request the international commission of inquiry on the September violence in Guinea to brief members of the UN Human Rights Council on their findings at the council’s 13th session to be held in March 2010.

- Support engagement by relevant special procedures of the Human Rights Council, such as those listed below, and follow up on their recommendations regarding the situation in Guinea.

To the United Nations Special Rapporteurs on Relevant Subject Areas

To the UN special rapporteurs on violence against women; on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions; and on the use of mercenaries as a means to violate human rights and to impede the exercise of the right of peoples to self-determination

- Closely monitor the situation in Guinea and request to visit the country.

To the International Commission of Inquiry

- Include specific recommendations in the commission’s report regarding accountability in accordance with international standards for serious crimes committed as part of the September violence in Guinea, with due consideration to the ability and willingness of the domestic authorities to investigate and prosecute alleged perpetrators.

- Include specific recommendations in the commission’s report regarding the need for an ongoing monitoring presence by the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights to ensure the monitoring and documentation of any acts of intimidation against witnesses and others who have provided information about crimes committed during the September violence.

To the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court

- As part of your preliminary examination of the situation in Guinea, consider the findings and recommendations of the international commission of inquiry on Guinea and closely monitor any domestic efforts to prosecute the crimes with a view toward assessing whether your office should seek to open an investigation of crimes committed as part of the September violence.

To Blaise Compaoré, President of Burkina Faso and ECOWAS Mediator on the Crisis in Guinea

- Ensure that accountability for the crimes committed on and after September 28 is part of any proposed solution to resolving the crisis in Guinea.

- Closely monitor the safety of victims and witnesses to the September violence, and intervene to protect individuals under threat if and when such threats occur.

Methodology

From October 12 to 22, 2009, a team of four Human Rights Watch staff members conducted research in Guinea into the massacre, rapes, and related human rights abuses that occurred on and following September 28 in the capital, Conakry.

Human Rights Watch researchers carried out some 240 interviews with victims wounded during the attack, witnesses present in the stadium during the attack, relatives of missing people, soldiers who participated in the violent crackdown and the government cover-up, medical staff, humanitarian officials, diplomats, journalists, and opposition leaders. All but a few interviews were conducted in a language spoken by the interviewee—either French or English. Any others were conducted through the use of interpreters.

Human Rights Watch received and reviewed numerous still photographs and clips of video footage from the September 28 events, which appeared to have been recorded on mobile phones. The photographs and footage were generally obtained through sources available to the public, including internet sites and on compact discs available for sale in Conakry markets. Other photographs and footage were given to Human Rights Watch by interviewees.

Interviewees were identified with the assistance of civil society groups, local aid groups, journalists, political parties, and medical clinics, among others. The interviews were conducted throughout Conakry, as well as in Senegal’s capital, Dakar, and in Paris, France. Most interviews were conducted individually, although they sometimes took place in the presence of family members and friends. Many interviewees expressed fear of reprisals by the security forces, and, for that reason, requested to speak anonymously. They were assured that their names and other identifying factors, or the name of their organization, would not be cited in the report. Details about individuals and locations of interviews when information could place a person at risk have been withheld, but are on file with Human Rights Watch.

I. Background

Guinea, a country of just over 10 million people, has three major ethnic groups—the Peuhl, representing 40 percent of the population; the Malinké, 30 percent; and the Sousou, 20 percent—and a number of smaller ethnic groups, including the Guerzé, Kissi, and Toma, which comprise the remaining 10 percent and live predominantly in the forest region in the southeast.[1] Each ethnic group has its own language, though French remains the country’s official language and Sousou is a lingua franca, particularly in Conakry and amongst the military.[2] Approximately 85 percent of Guineans are Muslim; the other 15 percent, predominantly those from the forest region but also some in Conakry and other large towns, practice Christianity or indigenous beliefs.[3] Despite having almost half of the world’s bauxite reserves and significant deposits of iron ore, gold, and diamonds, Guinea is one of the world’s most impoverished countries.[4]

The human rights of ordinary Guineans have been systematically undermined under the successive leaderships of Ahmed Sékou Touré, president from the time of independence from France in 1958 until 1984, and then Lansana Conté, who led Guinea until his death in December 2008.[5] A bloodless coup following Conté’s death on December 22, 2008, by a group of Guinean military officers calling themselves the National Council for Democracy and Development (Conseil national pour la démocratie et le développement, CNDD), led by a self-proclaimed president, Captain Moussa Dadis Camara, initially brought some hope for greater protection of democracy and respect for human rights.[6] However, since taking power, Dadis Camara and the CNDD government have entrenched military control of the country’s political affairs, failed to hold free and fair elections as they promised, and steadily and violently suppressed the opposition. The perpetrators of these abuses have enjoyed near-complete impunity.[7]

Early actions by Dadis Camara, a previously little-known officer responsible for the military fuel supplies unit, reflected a disregard for democratic principles and the rule of law. Despite the well-known involvement of several military officers within the CNDD in serious past abuses and crimes, including torture, Guinea’s new rulers took no action to vet, much less hold them accountable for their crimes. The Alpha Yaya Diallo military camp, commonly known as Camp Alpha Yaya, in Guinea’s capital, Conakry, has become the de facto seat of government, from where Dadis Camara and his colleagues have largely operated. Since the coup, some 20 military personnel, many linked to the old regime, have been held in irregular detention centers where they have been denied access to their lawyers and families and subjected to severe mistreatment.[8]

Initially, Dadis Camara took concrete steps to root out the high levels of corruption and involvement by government and military officials in drug trafficking that for years had plagued Guinea, a major transit location for cocaine trafficked between Latin America and Europe.[9] However, these efforts were characterized by a number of abuses and serious violations of the rule of law. Throughout 2009, heavily armed soldiers carried out frequent abuses against ordinary Guineans and businesspeople, including theft, extortion, and intimidation of the judiciary.[10]

Upon taking power, Dadis Camara quickly suspended the country’s constitution, dissolved the government, and declared a ban on political and union activity.[11] The new leader initially proposed to hold elections by December 2010,[12] but later, under international pressure, pledged to hold elections in 2009, in which neither he nor any CNDD member would run, and to relinquish control to a civilian-led government,[13] earning him the support of much of the Guinean population. However, few concrete steps to organize elections were taken, and throughout 2009 the CNDD government increasingly restricted freedoms of political expression and assembly. Attempts by opposition parties to campaign ahead of planned presidential elections were repeatedly met with intimidation and attacks by the government.[14] At various times throughout the year, Dadis Camara lifted and reinstated a ban on political and union activity. In response to heightened criticism from the Guinean public, in August he imposed a ban on mobile phone text-messaging and in September a ban on political discussions on radio talk shows.[15]

Opponents of the military regime, which include unions, civil society leaders, and all of Guinea’s major political parties—the Union of Republican Forces (Union des forces républicaines, UFR), the Union of Democratic Forces of Guinea (Union des forces démocratiques de Guinée, UFDG), the Union for Progress of Guinea (Union pour le progrès de la Guinée, UPG), the United Front for Democracy and Change (Front uni pour la démocratie et le changement, FUDEC), the New Democratic Forces (Nouvelles forces démocratiques, NFD), and the Union of Democratic Forces (Union des forces démocratiques, UFD)—banded together to form the umbrella Forum of the Forces Vives of Guinea (Forum des Forces Vives de Guinée). In March the Force Vives presented the CNDD with a timetable for election preparations, with a view toward holding legislative elections in October and presidential elections by December 2009. Though Dadis Camara agreed to this timetable, the CNDD failed to follow through and in May and June 2009 even refused to provide funding for the Independent National Electoral Commission (Commission électorale nationale indépendante, CENI)—the government body charged with organizing and monitoring the elections.

After months of delay, and under mounting pressure from both Guinean civil society and key international stakeholders, Dadis Camara, in August, set January 31, 2010, as the presidential election date. Although he stopped short of declaring his own candidacy, Camara back-tracked on earlier commitments, stating that any member of the CNDD should be “free to put forward their candidacy for the national election if they so desire.”[16] This was widely interpreted by Guineans as meaning that the military leader fully intended to run. Guinea’s opposition viewed Dadis Camara’s presumed candidacy as a spoiler for the election’s credibility, and responded by planning demonstrations of varying sizes across the country.[17] By the end of September, momentum toward mass demonstrations had reached a tipping point, with actions planned by the Forces Vives.

II. Prelude to Massacre at the September 28 Stadium

Choosing a Date for the Opposition Rally

The Forces Vives decided to hold a major rally on September 28, 2009, a date deliberately chosen because of its historical significance in Guinea. On September 28, 1958, France carried out a referendum in its colonies, giving them the choice between immediate independence and remaining a French colony. Guinea was the only French colony to vote “No” and gained its independence days later, on October 2, 1958. Guineans consider September 28, 1958, the day when Guinea stood united for the country’s independence.[18] The stadium in Conakry where the demonstration was to take place is named the September 28 Stadium.

The Forces Vives leaders called for a major opposition rally on this date for two reasons: first, to show the extent of their support among the population, refuting CNDD President Dadis Camara’s claim that the Forces Vives “do not represent anything”;[19] and second, to challenge Dadis Camara’s presumed candidacy in the elections planned for January 2010, which the opposition leaders hoped would return Guinea to civilian rule.

Shortly after deciding to hold the rally, the Forces Vives dispatched opposition leader Jean-Marie Doré, head of the Union for the Progress of Guinea (UPG), to inform Dadis Camara of their plans. Doré described Dadis Camara’s response when they met on September 19:

I went to see Dadis the same night we set the date of the rally, and informed him of our intention to hold a peaceful rally. He wasn’t initially in favor, but I said it would be peaceful and in an enclosed place. He said he was concerned there would be protest marches. I told him this was false, but that there would be large crowds walking to the stadium. He gave us his permission, so I immediately instructed the secretariat of the Forces Vives to send out letters to the director of the stadium, the minister of justice, the minister of the interior, the mayor of Conakry, the minister of youth, and other officials.[20]

Despite Dadis Camara’s apparent agreement to the rally planned for September 28, 2009, the CNDD attempted to prevent it from taking place. On September 22, the minister of youth, Fodéba Isto Keira, announced that the September 28 Stadium would be closed to the public from September 23 until October 11, in the interest of preserving the quality of the stadium’s field for an October 11 football match against Burkina Faso. Keira denied that the closure had anything to do with “politics.”[21]

On Sunday, September 27, the interior minister, Frédéric Kolié, appeared on national television to declare that “all demonstrations on the national territory are prohibited until the national holiday on October 2.”[22] Opposition leaders met in response to the announcement, and decided to go ahead with the rally despite the ban.[23] The same day, Dadis Camara declared September 28 a public holiday, and said that no public rallies would be allowed that day.[24]

Despite the official announcements, the Forces Vives received no official correspondence denying their request for the September 28 rally, and, thus, decided to proceed with the planned rally. According to Oury Bah, the vice president of the Union of Democratic Forces of Guinea (UFDG), the Forces Vives wished to hold the rally to demonstrate to the CNDD the level of popular support for the opposition: “We told our supporters to remain peaceful, even if we couldn’t enter the stadium. Our aim was simply to show that the population supported the opposition.”[25] Opposition leaders did not believe that they would face a violent response from the security forces, because, since Dadis Camara had come to power, they had heard him state publicly on several occasions that he would not deploy the military against the civilian population, unlike his predecessors.[26]

Finally, at 1 a.m. on September 28, Dadis Camara telephoned opposition leader Sidya Touré, leader of the opposition Union of Republican Forces (UFR), at his home. During the conversation, which Touré recounted to Human Rights Watch, Dadis Camara reiterated that September 28 was a public holiday that belonged to all Guineans, and said that the opposition “could not claim the historic date for their own purposes.” He demanded that the opposition call off the rally, and proposed instead that a smaller rally be held on September 29 at the smaller and more remote Nongo Stadium.[27] Touré explained to the CNDD president that calling off the rally would be impossible with such little notice, and that opposition supporters would start moving toward the stadium early the next morning.[28]

Morning March to the Stadium and Attempts by Security Forces to Block Opposition Supporters

From the early hours of the morning of September 28, tens of thousands[29] of opposition supporters walked toward the September 28 Stadium from the suburbs of Conakry, clogging the few main roads along Conakry’s narrow peninsula. At a variety of points along the way, security forces used force to try to block marchers from reaching the stadium, leading to deaths and injuries that pre-figured the events to come. Gendarmes, commanded by Captain Moussa Tiégboro Camara (no relation to the CNDD president, Dadis Camara), the minister charged with the fight against drug trafficking and serious crime, made a final attempt to block opposition leaders from entering the stadium by barring their path, but later retreated, likely because of the sheer size of the crowds.

The day after the massacre at the stadium, Dadis Camara claimed that opposition supporters had ransacked and burned two police stations while marching to the rally on the morning of September 28, arming themselves with guns and explosives, and that they were intent on overthrowing the coup government by force.[30] While some violence by protesters took place as the crowds walked to the stadium—most notably rock throwing and the partial burning of the Bellevue police station—such violence was not widespread. Human Rights Watch did not find any evidence that any weapons had been seized by opposition supporters during the clash at the Bellevue police station documented below, as alleged by Dadis Camara, and has not seen any evidence to suggest that any opposition supporters at the stadium were armed with firearms. Nor has the CNDD provided any evidence to support these charges, such as weapons seized from the stadium.

Shooting of Unarmed Protesters by Gendarmes near the Stadium

At around 9 a.m., anti-riot police attached to the Mobile Intervention and Security Force (Compagnie mobile d’intervention et de sécurité, CMIS) and gendarmes from the Anti-Drug and Anti-Organized Crime Unit under the command of Captain Tiégboro Camara attempted to prevent hundreds of opposition supporters gathered since 7 or 8 a.m. near the entrance to the stadium from entering.[31] Witnesses at the scene told Human Rights Watch that as the crowd grew, Tiégboro arrived to the stadium and ordered opposition supporters to return home. When they did not, he ordered a group of gendarmes to respond with tear gas, and then, almost immediately, with live ammunition. According to witnesses, at least two people were killed and several others were wounded in the incident.[32]A witness explained:

Around 9 a.m., Tiégboro himself arrived at the crossroads near the stadium where we were being blocked. He came down from his armored car and seemed surprised that people were celebrating and being peaceful. He tried to talk to the crowd, but you could tell he was angry. He told everyone they had to leave because no protest was authorized. People refused to go, so he told his gendarmes to fire tear gas and then they also fired their rifles and killed three people, I later saw two of their bodies. The gendarmes fired from right next to Tiégboro. I was standing very near to where he was. He first ordered them to shoot gas, and then he ordered them to fire their guns, and only a few shots were fired.[33]

Clashes at Hamdalaye and Bellevue Crossroads

Torrential rainfall that morning had delayed many more people from setting out to the stadium. As the rains subsided around 8:30 a.m., large crowds of opposition supporters left Conakry’s neighborhoods on foot, packing the main Donka Road leading to the stadium. At both the Hamdalaye and Bellevue crossroads on the main Donka Road, small units of security forces attempted to stop the crowds by firing tear gas, and in the case of Bellevue, by firing live ammunition.

At Hamdalaye crossroads, a group of anti-riot police attempted to stop people amassing there by firing tear gas, but reportedly found the crowd too big to manage and withdrew. Multiple witnesses who had gathered at the Bellevue crossroads described to Human Rights Watch how at around 10 a.m., gendarmes fired tear gas and then live ammunition, killing at least two and wounding others. Among those shot and killed was Mamadou “Mama” Bah, a 20-year-old student, who was hit as he watched the crowd from outside his father’s tailor shop.[34] The crowd then began throwing rocks at the security forces and attacked the local police station, partially burning it and several police vehicles. One policeman was wounded after being hit in the head with a rock and attacked by the opposition supporters.[35] The security forces retreated and the crowd continued on to the stadium.

Attempt to Block Opposition Leaders from Entering the Stadium

While opposition supporters were moving toward the stadium, the main opposition leaders—Sidya Touré, Cellou Dalein Diallo, François Lonsény Fall, Mamadou Mouctar Diallo, and Mamadou Baadiko Bah—met at the house of the UPG leader, Jean-Marie Doré, near the stadium.[36]

Throughout the morning, high-ranking religious officials, including the imam of the Grand Fayçal Mosque, el-Hadj Ibrahima Bah, and the Anglican bishop, the Rt. Rev. Albert Gomez, mediated between Dadis Camara and the opposition leaders in an attempt to avoid violence.[37] As the opposition leaders were about to head toward the stadium, they were informed by phone that the religious leaders were coming to Jean-Marie Doré’s house with a message from the CNDD leader. All but Jean-Marie Doré departed, seeking to join their supporters, while Doré remained to receive the religious leaders and their message. According to Doré, the religious leaders told him that Dadis Camara had agreed not to use violence against participants in the rally if the opposition leaders would go to the stadium and tell their supporters to peacefully disperse and not march on Camp Alpha Yaya, though marching on the military camp had never been an intention of the opposition.[38]

According to numerous witnesses and the opposition leaders themselves, as the group of leaders headed toward the stadium, several dozen gendarmes led by Captain Tiégboro Camara blocked their path in front of the Gamal Abdel Nasser University, which adjoins the stadium grounds. Tiégboro ordered them to turn back, which they refused to do. A tense stand-off ensued. Some minutes later, opposition supporters inside the stadium learned that their leaders were being prevented from entering, and large numbers came out to join the leaders, effectively surrounding Tiégboro and his force. As this happened, Tiégboro told the leaders to go to the stadium and tell people to go home peacefully. According to witnesses, he then ordered his gendarmes to fire into the air a few times to clear an exit path for the gendarmes to depart through the crowd. The crowd then took the opposition leaders on their shoulders and carried them into the stadium.[39] A 39-year-old trader described the ambiance:

When Tiégboro disappeared, we assumed permission to hold our meeting had been given. We walked with our leaders chanting, “Freedom! Freedom!” We said we were tired of 50 years of dictatorship. At around 11 a.m. we all entered the stadium through the main door. It was a wonderful atmosphere ... we were dancing and happy. We chanted, “Long live the nation, we want freedom.”[40]

As they entered, at around 11 a.m., the political leaders came into an arena packed with tens of thousands of jubilant supporters chanting pro-democracy slogans, singing, dancing, and marching around the stadium’s track carrying posters and the Guinean flag. Dozens of demonstrators were praying on the stadium’s field.[41]

III. Massacre at the September 28 Stadium

Human Rights Watch’s investigation into the September 28, 2009 events at the September 28 Stadium, based on more than 240 interviews, has determined that the massacre of an estimated 150 to 200 opposition supporters and rape of dozens of women and girls were organized and premeditated.

At around 11:30 a.m., soon after the opposition leaders arrived at the stadium, a combined force of several hundred soldiers, police, and civilian-clothed militias positioned themselves around the exits to the stadium, fired tear gas, and then stormed the stadium, firing directly at the trapped civilians. Many died from the indiscriminate firing; others were beaten or knifed to death; and still others were trampled to death by the panicked crowd. Outside the main stadium, on the sports complex grounds, many more opposition supporters were killed as they tried to escape. The opposition leaders were brutally beaten, some of them to the point of losing consciousness. Amidst the killing, the security forces also committed widespread rapes, as documented in the next chapter of this report. Human Rights Watch has not found any evidence that any member of the security forces was wounded or killed inside the stadium or within the stadium complex, demonstrating the one-sided nature of the violence perpetrated against the opposition supporters.

Numerous still photographs and clips of video footage from the September 28 events reviewed by Human Rights Watch firmly corroborate the accounts of the numerous victims and witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch who described the rally as largely peaceful.[42] Not a single armed protestor is visible in any of the photographs or video. The opposition supporters are seen marching, holding placards (including “No to Dadis,” “Dadis is a liar,” and “End military rule”), shouting slogans, singing songs, and praying inside the stadium. Also, none of the statements made before the rally to the press by opposition leaders showed any intent to incite the crowds to overthrow the CNDD. Rather, their messages almost exclusively called for a return to civilian rule and for Captain Moussa Dadis Camara not to run for president. The photographs and video footage of events before and at the stadium rally reviewed by Human Rights Watch do not provide any support for Dadis Camara’s post-massacre contention that the crowd was armed.

Attack on Rally Participants by Security Forces inside the Stadium

At around 11:30, about 30 minutes after the political leaders entered the stadium, several hundred members of the security forces arrived, mostly aboard vehicles. According to scores of witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch, the security forces who perpetrated the violations described in this report consisted of:

- Presidential Guard soldiers dressed in full camouflage uniform and wearing red berets. They were commanded by Lieutenant Abubakar “Toumba” Diakité, then Dadis Camara’s personal aide de camp and chief bodyguard, and Second-Lieutenant Marcel Kuvugi.

- Gendarmes wearing green berets and one of two uniforms: those wearing black T-shirts and camouflage pants formed part of the Anti-Drug and Anti-Organized Crime Unit under the command of gendarme Captain Moussa Tiégboro Camara; those wearing full camouflage uniforms appeared to be part of a second unit of gendarmes.

- Anti-riot police with the Mobile Intervention and Security Force (Compagnie mobile d’intervention et de sécurité, CMIS) wearing black pants and shirts. Many were equipped with riot gear, such as shields and helmets.

- Civilian-dressed militia armed with knives, sticks, and pangas (machetes), many of whom were wearing traditional amulets and fetishes. The majority were believed by witnesses to be from ethnic groups living in the southeastern forest region of Guinea.[43]

The vast majority of the killings and sexual assaults documented by Human Rights Watch were committed by members of the Presidential Guard, or “red berets” as they are more commonly known.

After the security forces reached the stadium, they quickly encircled it, mostly on foot. Anti-riot police then fired tear gas into the stadium from their vehicles, causing widespread panic. Minutes later, Presidential Guard soldiers, and a smaller number of other forces, stormed through the principal entrance, firing directly as they advanced forward into the packed and terrified crowd. Numerous witnesses described the gunmen “spraying the crowd from left to right, left to right.” Many witnesses described the soldiers shooting at people as they tried to climb up over the fences and walls. A retired professor in her sixties, recalled:

All of a sudden, I heard these loud noises—boom, boom—it sounded like a war. That was the firing of the tear gas from outside the stadium. Then, within minutes, the red berets entered. They were everywhere. The youth were on the field. When the soldiers entered, they opened fire right away on that crowd. Everyone went into panic, people were running everywhere—I saw people jump from the top of the covered stands. There was screaming everywhere, screaming so loud, and the crowd started to stampede.[44]

A 65-year-old man described what he saw:

I clearly saw them spraying back and forth, back and forth, and people falling in their path. They fired as they moved down the field. I fell down on top of others who had been shot ... my boubou [clothing] was drenched with the blood of young men. These people are trained to defend us from harm. Instead they turned their guns on us. It was a meeting, not a war. We wanted to talk—we wanted them to listen to us, not shoot and kill us.[45]

A 32-year-old trader told Human Rights Watch that he heard the soldiers yelling, “We’ve come to clean!” as they opened fire into the crowds.[46] A medical student described the different security forces that he saw perpetrating the violence:

I was sure they wouldn’t kill like they did in January 2007,[47] but I was wrong. As soon as the gas was fired I knew there would be trouble so I immediately tried to run out one of the side gates, but when I reached the main gate, I saw the military deploying around the side of the stadium. I immediately ran back to the stadium and moments later saw them flooding in—they were mostly red berets dressed in camouflage, then the gendarmes from Anti-Drug in camouflage pants with black T-shirts, a few from Anti-Gang in all black, and a few regular green beret gendarmes. I saw them firing directly into the people gathered in the stadium, stands, and even at the youth trying to get over the gates and walls to escape.[48]

Many witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch described how the attackers continued to shoot at those gathered both on the field and in the stands until they had emptied the two clips of ammunition many of them carried.[49]

A 22-year-old student, described to Human Rights Watch how he watched the shootings start and was then beaten to the ground as he tried to escape:

The first who entered the stadium were the red berets, followed by Tiégboro’s gendarmes and the anti-riot police. They came into the stadium from the main gate and the smaller gates, and immediately began shooting directly at the people. The first victim I personally saw was a young boy, maybe 13 or 14, who was shot down on the field. I was coming down the stands then. There were so many people shot then. I ran down to the field, and then I was hit by a red beret with a wooden stick in my knees. I fell down to the ground, and then four came—a red beret and three dressed in all black uniforms with police berets. They beat me with wooden sticks for five minutes. One of them said, “If you think Guinea belongs to the Peuhl and the Malinké, today you will learn who the real bastards and the mad dogs are.” I couldn’t get up anymore, so I just stayed on the ground. There was a girl next to me, she was nearly naked, only in her underwear, she was crying and bleeding, so I gave her my T-shirt. Then I lost consciousness and woke up at Donka Hospital.[50]

Witnesses recounted how at the far end of the covered stands, as the panicked crowds pushed open another major gate, members of the Presidential Guard stood at the entrance and attacked the crowd as they tried to flee. Many died there from being shot or as a result of being trampled to death. Several witnesses who observed bodies near the stadium exits told Human Rights Watch that many did not appear to have gunshot or knife injuries, indicating that a number of those killed were trampled to death. A shopkeeper in her fifties told Human Rights Watch how she faced gunfire and beatings to escape through an open door, and described walking over the bodies of those who had been trapped:

The crowd kept pushing toward that one available exit. The red berets were hitting people over and over as they exited. I ducked down to avoid being hit, and at about that time there were gunshots and someone right next to me was hit and fell down. I don’t know what happened to that person, the crowd just kept moving. After all that pushing, I finally got out of the door. I was knocked down, and there were bodies all on the ground. I was crawling on dead bodies. I was scared they would shoot me if I lifted my head, so I kept my head down, looking right at the dead bodies.[51]

A 51-year-old businesswoman who survived being trampled as she tried to escape, and then witnessed the killing of an adolescent boy as she hid beneath a number of bodies, pretending she was dead, described her ordeal:

I tried to run out one door which had been forced open by the panicked people. But I fell down and was trampled ... I was almost unconscious. People were on top of me. There was shooting all around. When I came to, people were running out and I was lying on the bodies of the dead. I heard a voice saying, “Oh she opened her eyes ... she’s not dead.” He tried to pull me up but I was too heavy. More shots rang out and he fled. I remained there, now pretending I was dead. As I lay there, I saw a 13- or 14-year-old boy near the door looking for where to escape. A red beret approached him with his gun facing him and I heard the boy yell, “Uncle, uncle ... you’re going to kill me.... Uncle, no, you’re not going to kill me are you?” But he did ... the red beret shot the boy. This was right next to me.... Oh God, when I see that boy I see my own children.”[52]

A 29-year-old hairdresser told Human Rights Watch how she was repeatedly beaten and trampled as she tried to escape from the stadium through the main entrance, and ultimately suffered severe burns when she fell on top of a tear gas canister and lost consciousness:

We ran down the stands toward the fence separating the field from the stands. There were lots of people pushing up against the fence and I was crushed down by the crowd, and then had two people fall down dead on top of me from being shot. I made my way to one of the gates in the fence and a soldier started beating me, but I pushed my way through and was on the grass. Another soldier kicked me to the ground. I got back up and made my way to the big gate. Another soldier yelled at me to stop and hit me with his belt. I fell down, and then others fell on top of me—they were firing tear gas and bullets at us, and I fell down on top of a tear gas canister and was now under people’s feet. I stayed on the ground. When things calmed down a bit, a soldier walked over to see if I was dead. He put his boot on my arm to see if I would move, but I stayed still, acting dead. After a while, I lifted my head and asked someone to help me. I was under 10 dead people, piled on top of me. They moved the bodies to get me out, and I saw I was burned all over my body and arms, my belly and my legs. They took me from the pile of bodies and out of the stadium.[53]

Many of the victims and witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch had managed to hide within toilets, locker rooms, and maintenance rooms during the worst of the stadium violence. When they emerged, sometimes hours later, they described seeing many bodies, some of which had been lined up on the field or close to the stadium entrance. A 39-year-old businesswoman who had hidden within a locker room described what she saw after daring to come out:

When I saw the rapes on the field, I was scared, so I ran back up the stairs and then jumped off to get away from the red berets chasing me. I injured my foot in the fall. A young man grabbed me and led me to the locker room, where there were 30 other people. We closed the door because the red berets were coming. The others begged to come in but we couldn’t—if we had, we all would have died. We shut the door. Minutes later, they opened fire ... the people kept begging to be let in. They killed everyone who was outside. Later, when it was safe to come out, we saw so many bodies there.[54]

A schoolteacher in her fifties, who had been hiding inside another locker room or room in the stadium, described the aftermath of the bloody encounter in the then near-abandoned stadium:

When I left the locker room, I went out to complete desolation—there was blood everywhere, lost shoes, glasses, clothes, all scattered around the field. It hit me. I was devastated when I saw a boy’s shirt covered with blood. I bent down and picked up a handful of dirt from the stadium and put it in my bag. I did this twice, because I wanted to take something with me from this day. I continued walking and the first dead body I saw was of a very large woman who had fallen over on her stomach. The military, or perhaps civilians that they had forced, had not been able to move this body into the line with the other bodies. I continued walking and saw a long line of bodies. I said to myself, I must count them, and so I did. I counted 40 on this line, inside the stadium field—I counted them all. They had been laid there, one next to the other in a line. There were others scattered around the stadium still waiting to be moved, and more still outside the field, but there were 40 in that line, I am sure.[55]

Pursuit of Rally Participants by Security Forces outside the Stadium

The killings and other abuses were not limited to the inside of the September 28 Stadium. Human Rights Watch documented numerous killings, beatings, and rapes that were carried out outside the main stadium.

The main stadium is located inside a large sports complex surrounded by high walls; it has a small number of exits with metal gates. Inside the sports complex, there are toilets and showers near the main entrance, a series of basketball and volleyball courts just below the covered stands of the stadium, and a second, smaller “annex” stadium a short distance away, with a high wall separating the sports complex from the neighboring grounds of the Gamal Abdel Nasser University. At the time of the attack, some construction was taking place between the main stadium and the annex stadium, which had left several deep holes in the ground. On the opposite side of the main stadium, another high wall separates the sports complex from the grounds of the private Marocana Club and the grounds of Pharma-Guinée, a pharmaceutical-importing state enterprise.

As panicked opposition supporters escaped from the main stadium, they found the entire sports complex occupied by the security forces and men in civilian dress armed with sticks and knives. Most of the escape routes out of the complex were blocked, and many people were shot or knifed down as they attempted to flee. A 24-year-old graduate student described how he barely escaped getting knifed as he attempted to flee the stadium:

There were three small doors on one side of the stadium that people were trying to escape through. As I was looking for where to escape, I saw a few soldiers come in through the small doors and start firing at people from there. Then I saw some armed men in civilian clothes start attacking people with knifes—it was like the military and these guys were working together. When people tried to push themselves through the doors, the civilians and military [about 10 in total] would knife them as they tried to slip by. I saw about five people wounded like this, including a guy I was trying to flee with. As we pushed by, the civilian-dressed guy stuck him in the shoulder. He fell down, and I continued. I heard them talking in bad French as they were doing this ... “Who told you to come here? We’re going to kill you.”[56]

Many people tried to flee by climbing to the top of the stadium’s covered stands and then jumping down the estimated 10-15 meters to escape. According to witnesses, many people died from injuries sustained by the fall, or from others landing on top of them. Still others were gunned down after surviving the jump. A 41-year-old merchant told Human Rights Watch how he had been forced to jump, injuring his leg in the process, and how he saw 38 bodies at the exterior of the stadium, near the bottom of the covered stands:

The military closed off all the exits. I ran up the covered stands. When I got to the top, I looked back and saw them firing on the field and also now firing coming up the covered stands. I had no choice but to jump—it must have been 30 meters down [sic, an estimated 10-15 meters]. There were lots of people jumping, someone landed close to me and I heard their ankle just snap. When I hit the ground, I lost my breath and couldn’t move. There were soldiers not far from me, and they were firing [at us]. One of the bullets went through my pant leg. I could feel it, but it didn’t enter my skin. There were so many people around, and I was breathing with great difficulty because of the fall.

A red beret came up to me and gave me a kick to the head. He took my money, my cell phone, everything. He then took a knife and put it to my head, but he didn’t cut me, then he left. I lied there, unable to move, and I counted up the dead bodies around me. There were 38. The soldiers kept going through the cadavers and taking stuff. I was lying with dead bodies ... 38 cadavers just at around the place where I jumped off the covered stands. I counted them while I lay there.[57]

Another witness, a 23-year-old hairdresser, saw one of her friends shot dead right next to her as they tried to escape from the area behind the covered stands, and then hid, only to see many more people shot dead in the same area:

As we were running behind the covered stands, outside the stadium, me and two friends, one of my friends was shot in the chest. She fell down and cried out, “Help me!” but there was nothing we could do. I didn’t see who shot her—I think they were behind us. It was just chaos, there were so many people running.... I saw the clinic for the football players, right underneath the covered stands, and we hid there for a short period of time. People were running all around, and I saw so many shot there, I couldn’t even count.[58]

Similar violence took place at the entrance to the stadium grounds, known as the esplanade, a walkway area between the main entrance gate into the sports complex grounds and the main entrance to the stadium. The 23-year-old hairdresser who gave the above account told Human Rights Watch how she saw another friend shot dead as they ran for the main entrance, and how she herself was attacked and stabbed by Presidential Guard soldiers:

Finally, my friend and I ran toward the main entrance, the one that heads out to the road in front of the stadium. As we were running with a number of other people, my friend was shot. The gunshot went through his neck, and he fell to the ground; the blood just flowed through his shirt, and he lay there, dead. I kept running, and as I got close to the main entrance, a red beret knocked me down to the ground and then jumped on me, up and down on my stomach. I could not speak, the pain was so much, and he just kept on jumping. Then another red beret came and stabbed me in the arm with a knife and hit me in the face. They just kept beating me.[59]

Around the basketball and volleyball courts and the small annex stadium, a large crowd of opposition supporters became trapped against the high walls separating the sports complex grounds from the neighboring university grounds. A group of red berets and gendarmes pursued them, firing at the trapped people as they tried to scramble over the walls. A 32-year-old shopkeeper described to Human Rights Watch how five of the group of eight people with whom he was fleeing were shot there, and how others were bayoneted to death as they tried to climb the perimeter walls:

I decided to try and run out of the stadium. At the far gate, one of the doors was open but there were so many people trying to flee, I decided to climb over the closed door.... I ran toward the perimeter wall. Near the basketball court, a group of red berets and gendarmes from Tiégboro’s unit were chasing us. They fired on a group of eight of us, and only three of us were able to get away alive. Five of us were killed, shot down near the wall facing the university. We couldn’t get out there, so we ran back to the broken wall near Donka Road. A group of red berets was there waiting for us, two trucks of them. They were armed with bayonets. I saw one red beret kill three people right in front of us [with a bayonet], so I wanted to run back. But my friend said, “There are lots of us, let’s try and push through,” and that is how we escaped.[60]

A 47-year-old factory owner told Human Rights Watch how he quickly made his way out of the main stadium, only to find himself trapped in the area of the annex stadium, where he saw the killings by members of the Presidential Guard continue:

Toumba [Lieutenant Abubakar “Toumba” Diakité] pointed his rifle in our direction and fired at us, and it was then that I realized they had come to kill.... Outside the main stadium, the red berets were chasing us. We ran toward the small annex stadium. There were people being shot down everywhere, there was blood everywhere on the ground. Near the annex stadium, there were some construction holes in the ground, and I jumped over them. But there was a wall blocking our way near the university, so we were stuck. People were being crushed to death there as they tried to climb up and run away over the roofs of the houses. I finally managed to climb the big wall and was helped over the wall, but I looked back to see the gendarmes still beating people.[61]

Another witness, a 27-year-old shopkeeper, told Human Rights Watch that he had seen many dead in the same area:

There were lots of bodies at the small annex stadium, and they continued to shoot people there. There were also shot-down electrical wires on the ground, electrocuting people.[62]

One witness, a 30-year-old market woman, described being duped by a few Presidential Guard soldiers who indicated to a large group of people that they would be provided safe passage, only to open fire when they drew nearer:

As I ran toward the main entrance, I saw the red berets firing on the high voltage wires. It fell and we were no longer able to go out this way, so we exited out near the stadium annex. I was running with a group of about 25 to 30. When we got to the annex, the red berets circled us and started beating us with pieces of wood—some of them had nails in them. I got away and ran, but about 50 meters away, another one kicked my feet out from under me. I got up again and ran towards the volleyball court. When I got there, I joined up with a big group of us—about 200—all looking for the best place to escape. Some meters away there was a group of red berets who started telling us to run toward them.... They shouted, “Come, come ... here, here,” motioning at a small door near the volleyball courts that leads to the university. When we got about 10 meters away, they took position and opened fire on us. Those in front of me started falling down wounded and dead. They fired and fired at us.[63]

A 19-year-old student who was beaten by security forces and hid in an area under construction behind the stadium recounted to Human Rights Watch:

As I sat there, no more than three meters away, I saw them shoot an old man dressed as an imam in the head while he was praying. The old man was in the process of praying, because in the Muslim faith, if you are going to die, it is necessary to pray before dying. He was in the process of praying and a red beret walked up to him and shot him in the head with a pistol. Nearby, there was another man who wanted to pray. As he kneeled there, one of the ones wearing gris-gris [amulets] said, “Don’t say another prayer,” and came up behind him and slit his throat.[64]

Outside the grounds of the sports complex, the killings continued. According to witnesses, Karim Bangura, a 28-year-old taxi driver from the Matam neighborhood was inside the stadium when the shooting started. He managed to get out of the sports complex and was trying to use his taxi parked outside to assist the wounded. Red berets approached him and demanded the keys of his taxi. When he refused to hand the keys over, the red berets shot him dead and took his taxi, leaving the body behind.[65]

Several victims and witnesses described how individual gendarmes tried to stop members of the Presidential Guard from committing abuses. In some cases, they extracted men and women from an imminent attack and watched over them until they could leave safely. A 29-year-old seamstress helped by one gendarme recounted to Human Rights Watch:

After escaping to the parking area, two soldiers tripped me and started ripping off my clothes, while others who weren’t in uniform brought forward a piece of wood, like they wanted to rape me with it. As they struggled to hold me down, a gendarme dressed in camouflage with a green beret yelled at them, “Leave this girl! It’s not like this.... You also have mothers and fathers.... You should not be doing this!” But the others told him to go away and leave them. He insisted and eventually took me away and told me to hide in a place near the basketball court. I was hiding with about 10 others. While hiding, we saw other red berets stab and kill two men. The gendarme yelled at them to stop doing such bad things, and stood watch over us until it was safe to go.[66]

A 27-year-old secretary recounted how she and some 50 others were assisted by another gendarme:

As I held up a friend who’d been seriously beaten, a gendarme came to our group—we were about 50 or so—and said, “Come ... there is an exit here.” Unfortunately he didn’t see two red berets behind him. One of them started striking us, and kicked my feet from under me, beating me further with his rifle butt. I got up and the gendarme helped us toward the exit. As I left, other red berets were knifing people with their bayonets as they tried to flee out the door.[67]

Over 1,400 opposition supporters were wounded during the attack on the stadium.[68] In addition to the many who received gunshot wounds, large numbers of opposition supporters were cut with knives, bayonets, or machetes; beaten with rifle butts, batons, and sticks; and pummeled, slapped, or kicked by the security forces as they tried to escape. Many others suffered broken bones and severe cuts after being trampled by the panicked crowds, jumping down from the top of the stadium’s stands, or as they tried to climb over walls and fences. Many victims revealed to Human Rights Watch signs of the injuries that they sustained, including bullet entry and exit wounds; scars from knife and machete wounds; and black and blue marks. Three weeks after the events, numerous victims of the stadium violence interviewed by Human Rights Watch continued to limp or required the assistance of a cane or crutch to walk.

High figures of wounded were reported from multiple sources. More than 500 persons were treated for serious injuries at Conakry’s Donka Hospital alone,[69] and many others sought treatment from other hospitals and smaller medical clinics throughout the city. The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) reported that by November 8, 1,434 persons injured in the September violence had been registered by a crisis committee set up after the events.[70] Of these, 123 had been hospitalized and five had died of their injuries after being hospitalized.[71] Many of the wounded were initially too frightened of further attack by the security services to seek medical attention for their injuries, particularly given the military presence at Donka Hospital on the afternoon of September 28 (see chapter on the military takeover of Donka Hospital below).

During and after the stadium violence, the security forces engaged in widespread theft from those who had attended the rally, including from individuals who had been gravely wounded. Dozens of witnesses described to Human Rights Watch how they were robbed while lying wounded on the ground or while trying to flee from the stadium grounds. They described having their pockets searched, or being threatened at gunpoint to hand over their phones, money, jewelry, cameras, shoes, and identity documents. Other witnesses described soldiers going through the clothing and belongings of people who had been killed during the violence. These acts were usually accompanied by physical abuse.

A 47-year-old factory worker recalled to Human Rights Watch how, after managing to escape from the stadium compound, he was robbed of all his belongings by a policeman:

A policeman stopped me and asked me to empty my pockets, and took my phone and wallet. He patted me down, and at the same time a soldier was trying to hit me in the face with a wooden stick.[72]

A 38-year-old storeowner told Human Rights Watch how he was knocked down and had his money and phone stolen:

At the exit near the university, I found a lot of gendarmes and red berets there. One hit my head with a rifle; it knocked me down and then I took another hit from a gun to my hand and body. They took my papers, my money, and my cell phone.[73]

Attack by Presidential Guard on Opposition Leaders

While the Presidential Guard attacked opposition supporters on the field of the main stadium, their commanders sought out the main opposition leaders who remained on the main podium, together with numerous other high-level party officials. A bodyguard for opposition leader Cellou Dalein Diallo told Human Rights Watch that he saw a group of Presidential Guard soldiers led by Lieutenant Abubakar “Toumba” Diakité and Toumba’s deputy, Second-Lieutenant Marcel Kuvugi, head directly toward the leaders. The witness also saw with this group two other members of the Presidential Guard whom he identified as “Sankara” and “Careka” who, he said, sometimes have worked as drivers for Dadis Camara.[74]

Numerous witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch identified Toumba at the scene. A few witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch observed Toumba both beating opposition supporters and, in a few cases, firing at people in the covered stands. Toumba is a well-known figure in Guinea because of the regularity with which he has accompanied Dadis Camara to public appearances, many of which have been photographed and televised. Several witnesses noted as well that Toumba is easily recognizable for the distinctive manner in which he wears his red beret, pulled low over his head like an ordinary woolen hat. A 29-year-old hairdresser told Human Rights Watch that she came face-to-face with Toumba as he moved toward the stands, firing in her direction:

The red berets came inside [the stadium] and moved up the stands. We tried to run down, but saw Toumba coming toward us. He had his gun and shot at my brother. My brother fell down and let go of my hand when he saw Toumba pointing his gun, so a young child behind us was shot instead. It was Toumba himself who shot the child. My brother got back up and climbed the fence [separating the stands from the field].[75]

One 47-year-old businesswoman described how she was beaten by Toumba shortly after he arrived at the covered stands: