“We Are Still Here”

Women on the Front Lines of Syria’s Conflict

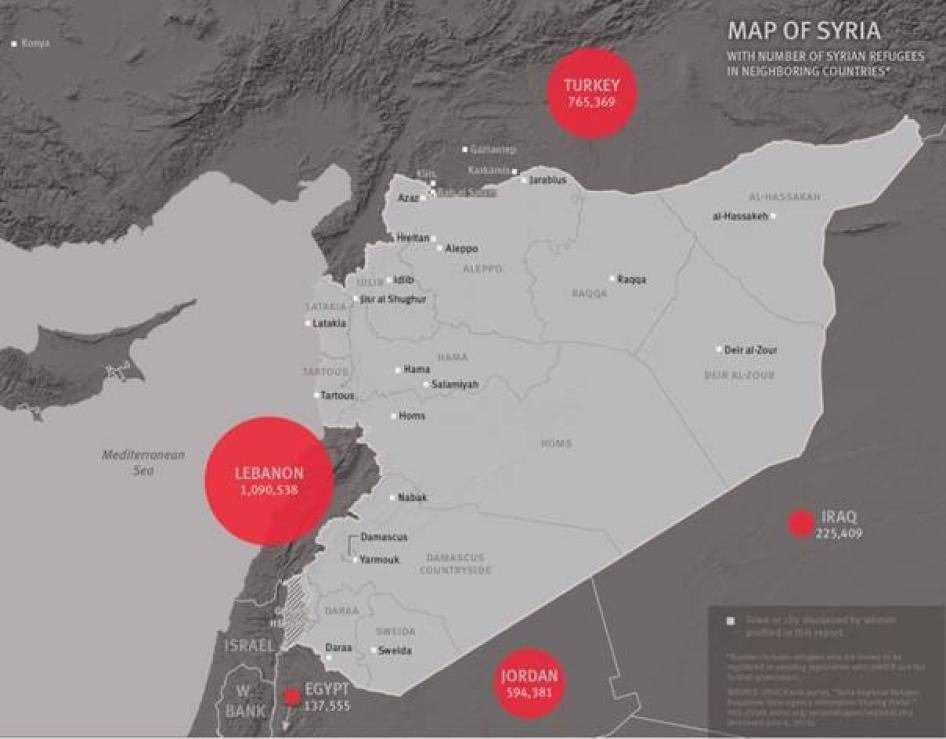

Map of Syria

Introduction

“On the news [about Syria] you only see blood and destruction. You don’t see that behind it, there are civilian groups doing things peacefully. We are still here.”

–Maha, age 28, an activist from Aleppo, April 8, 2014[1]

Maha, 28, was an elementary school English teacher in Aleppo when uprisings began in Syria in March 2011. Through friends, family, and her husband, Maha gradually became an activist. Newly married, Maha had just participated in a peaceful demonstration in November 2012 when shelling by government forces landed on the protest site, killing her 30-year-old husband and leaving her a widow at 26.[2] Maha – an activist, a survivor, and a victim of the conflict’s violence – exemplifies the complexities that mark the lives of many Syrian women today.

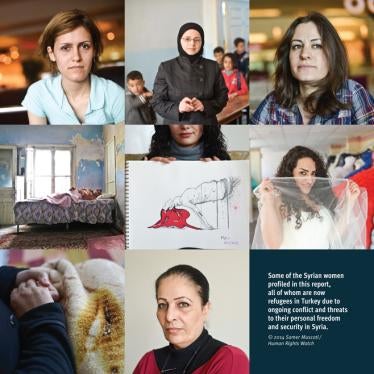

This report profiles 17 Syrian women, now refugees from their country, which continues to be ravaged by conflict.[3] Their experiences reflect the various roles that women, particularly those opposed to the government or living in areas that came under government attack, have taken on as political activists, caregivers, humanitarians, and providers, as well as the particular ways in which the conflict impacts women.

Some of the women profiled in this report have long histories of activism while others began participating politically only after the beginning of uprisings against the Syrian government. Some were targeted or arbitrarily detained for their work, such as Jelnar, 27, who used her pharmaceutical credentials to smuggle medications between neighborhoods.[4] Several of them experienced torture, sexual assault, physical abuse, or harassment as a direct result of their activism, like Layal, 21, who was detained by government forces for assisting the internally displaced.[5] Others became household heads following their husbands’ arbitrary detention or death, such as Zeinab, 42, who lost her husband and son in separate incidents at the hands of government forces.[6] Some suffered injury themselves, like Aisha, 45, who was paralyzed by a sniper’s bullet.[7]

Whether participating in demonstrations, providing humanitarian assistance, or taking on responsibility for family in the wake of death, injury, or detention, these women are not only bearing the burden of conflict but persevering in spite of it, often at great personal risk.

Recognizing women’s multiple and significant roles in the conflict, and their experiences as both actors and victims, is critical to developing appropriate responses to women’s needs inside Syria and in refugee communities and to ensuring their ongoing and meaningful participation in determining Syria’s future. It is also important in the face of the efforts of emerging extremist groups to sideline women in Syria and impose discriminatory restrictions limiting their freedoms.

The international community should provide greater support for women’s medical, psycho-social, and economic needs and ensure their meaningful inclusion at all levels in further peace negotiations and state-building initiatives.

Background: Women in Syria’s Conflict

|

In Syria’s ongoing conflict, civilians often bear the brunt of the violence that has shaken the country since 2011. In flagrant breach of international human rights and humanitarian law, government and pro-government forces as well as non-state armed groups opposed to the government have subjected civilians to deliberate, indiscriminate, and disproportionate attacks as well as denial of humanitarian assistance. Civilians have also faced arbitrary detention, abduction, torture, and summary execution. Calculating and confirming the number of those killed in the conflict has proven difficult, but in June 2014, the Violations Documentation Center (VDC), a Syrian monitoring group working closely with a Syrian activist network, reported having documented over 98,000 civilian deaths, including over 10,700 women and girls.[8] The conflict has also created the world’s largest displacement crisis in decades. The United Nations refugee agency (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, UNHCR) reported that, as of June 11, 2014, over 2.8 million refugees had fled Syria and were residing primarily in neighboring Lebanon, Turkey, Jordan, Iraqi Kurdistan, and Egypt.[9] Over half of these are women and girls.[10] Within Syria people are also fleeing in massive numbers, often moving multiple times in search of security and livelihoods.[11] As of May 26, 2014, the United Nations (UN) estimates that more than 6.5 million people are internally displaced in Syria.[12] |

In the course of its investigations into Syria’s human rights crisis since March 2011, Human Rights Watch has documented cases of numerous women who, from the initial uprisings against the government of Bashar al-Assad in the spring of 2011, have organized and participated in peaceful demonstrations, delivered vital humanitarian assistance to those in need, and provided medical care to the wounded.

Like their male counterparts, Syrian women active in demonstrations and civilian assistance are targets for abuse, harassment, and detention by government forces and, sometimes, non-state armed groups opposed to the government. Human Rights Watch has documented cases of women arrested due to their activism, including for participation in peaceful demonstrations and provision of humanitarian assistance. Many of them suffered assault, torture, harassment, or deprivation by government and pro-government forces and, in some cases, non-state armed groups in official and unofficial detention facilities. Most were denied communication with family members and access to due process.[13]

Syrian women also told Human Rights Watch that the absence of men, whether due to indiscriminate attacks, arbitrary detentions, enforced disappearances, or engagement in military operations, left them vulnerable to abuse during household raids and search operations by armed groups. In one case, during a military offensive on Alawite villages in Latakia countryside in August 2013, non-state armed groups abducted and held hostage over 200 civilians, primarily women and children, to use for political leverage.[14]

Numerous women from across Syria told Human Rights Watch that they had led searches for disappeared or detained relatives and assumed greater responsibility for supporting families, aiding civilians, and participating in or leading non-violent demonstrations. Women told us about becoming caregivers for family members who are injured or living with conflict-inflicted disabilities. Many women also said that they had become de facto household heads in such cases, or when faced with the death, disappearance, or detention of male family members. Such risks are prevalent not only in the conflict itself, but also during flight from Syria. Warda, from Aleppo, recounted to Human Rights Watch how her husband was killed and son injured while they were waiting to cross the border to leave Syria for Turkey.[15]

At the same time, in a number of cases, Human Rights Watch found that women’s mobility has been curbed significantly. In interviews at refugee sites, women and their family members reported having limited women’s and girls’ movement outside the home in Syria due to fear of sexual violence, harassment, and indiscriminate attacks. In some cases, as Human Rights Watch has documented in Aleppo, al-Hassakah, Idlib, and Raqqa governorates, extremist armed groups have placed discriminatory restrictions on women and girls. Such restrictions include strict dress codes, limitations on women’s engagement in public life and ability to move freely, and constraints on their access to education and employment.[16]

Additionally, some Syrian laws, including personal status laws that regulate marriage and family life, remain discriminatory against women. Women may also be subject to social customs and traditions that constrain their personal freedom and increase their vulnerability.[17] While men also face limitations due to social norms, legal and societal restrictions related to family, social and economic life impact women disproportionately. Despite this, many women told Human Rights Watch that they have become their family’s primary breadwinners as men struggle to find steady work, including in refugee and internal displacement settings. As the statements of women in this report show, their responsibilities in Syria are shifting and expanding out of necessity. In the face of extraordinary loss, the women profiled here persist in providing for their families, aiding fellow Syrians, and speaking out to support freedom and human rights for all Syrians.

These are some of the faces of women in the Syrian conflict.

“You Feel You Will Never Be Free Again”: Arbitrary Arrest, Detention, Torture, and Abuse

|

Arbitrary arrest, detention, and torture have characterized Syria’s conflict since the uprising began in March 2011. Human Rights Watch has documented the arbitrary arrest, detention, and enforced disappearance of dozens of people by government and pro-government forces as well as non-state armed groups opposed to the government in governorates across the country.[18] Human Rights Watch has also documented systematic torture in 27 government-run detention facilities in Aleppo, Damascus, Daraa, Homs, Idlib, and Latakia governorates as well as torture in facilities run by anti-government groups.[19] The majority of former detainees interviewed by Human Rights Watch have been men between 18 and 35, but government and anti-government forces have also arbitrarily detained and tortured children, women, and the elderly. Human Rights Watch has documented the arbitrary detention, physical abuse, and torture of women by government forces and non-state armed groups in Aleppo, Damascus, Daraa, Hama, Homs, Idlib, Tartous, and Raqqa governorates.[20] It is impossible to confirm the number of detainees due to the Syrian government’s refusal to allow independent monitors access to detention sites, but as of May 26, 2014, the Violations Documentation Center (VDC), a Syrian monitoring group, had documented 52,674 detentions since the beginning of the conflict, including 1,477 women and 55 girls.[21] According to VDC data, over 40,400 of these detainees are still awaiting release.[22] Government and pro-government forces, and some non-state armed groups, have subjected women to arrest, detention, and torture for engaging in peaceful protests and activism, delivering medical and humanitarian aid to civilians and the displaced, and assisting military defectors or anti-government fighters. Seventeen of twenty women who had been detained told Human Rights Watch that they were arrested due to their own activism, including participation in peaceful demonstrations and provision of humanitarian assistance. Three were detained, and five others physically abused, by government security forces simply because of the suspected association of their relatives or neighbors with pro-opposition forces. In most cases documented by Human Rights Watch, arrests and detentions were unlawful or otherwise arbitrary: security forces conducting the arrests did not identify themselves, provide legal justification for the arrest, or inform detainees of where they were being taken. Detainees were often held for lengthy periods of time – well beyond the 60-day maximum pre-trial detention period permitted by Syrian law – without due process. Often, detainees did not have access to a lawyer, were not formally charged, and never went before a judge. In many cases, family members were denied information about detainees’ whereabouts or grounds for their arrest. Such instances can qualify as enforced disappearances under international law. [23] Widespread or systematic enforced disappearances or arbitrary detention, carried out as part of a state policy, can constitute a crime against humanity. [24] As noted above, in the course of research on Syria over the past three years, Human Rights Watch has documented cases of women who experienced physical and sexual assault, harassment, torture, or deprivation by government and pro-government forces and, in some cases, non-state armed groups, in official and unofficial detention facilities.[25] The ban against torture is one of the most fundamental prohibitions in international human rights law. No exceptional circumstances can justify torture. Syria is a party to key international treaties that ban torture under all circumstances, even during recognized states of emergency, and require investigation and prosecution of those responsible for torture.[26] When committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack against the civilian population, torture constitutes a crime against humanity under customary international law and the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court.[27] |

Layal [28]

Originally from Homs, Layal, 21, became part of a Damascus group providing temporary housing in hotels, warm clothing, and other necessities to displaced families from Homs. On November 8, 2012, plain-clothed men whom Layal identified as pro-government militia members arrested Layal and took her to a detention facility that she thought was Military Intelligence Branch 215 in Damascus.[29] At the time, Layal was carrying digital memory cards with names and addresses of families she was assisting. “I chewed the cards and bit them to break them. Then I swallowed them,” she said.

A male officer at Branch 215 forced Layal to undress and searched her and her clothing. After dressing, a second male officer handcuffed her, forced her to kneel backwards on a chair, molested her, and beat her feet with a thick electric cable.[30] “The more I screamed and cried, the more he was aroused. After he finished [molesting me], he kept beating me on my feet. I fell down on the ground. He kicked me with his boots. For seven days, I couldn’t walk on my feet,” she said.

During her detention at Branch 215 and later at a facility she thought was Military Intelligence Branch 261 in Homs, where she was transferred in December 2012, officers tried to force Layal to confess that she had a part in organizing bombings in al-Kazzaz, Damascus, in May 2012, and in al-Malaab neighborhood and near the Quba Mosque in Homs in December 2012.[31] When Layal denied this, they threatened to harm her two young children and her parents.

One day at Branch 215, an officer brought Layal to his office to see digital photographs retrieved from her confiscated cell phone, including pictures of her unveiled or wearing sleeveless shirts. “For a woman in hijab [headscarf] this is very humiliating,” she said. “He said, ‘If you don’t admit you are responsible for the explosions I will publish the photos of you on the internet, everywhere.’”

After 23 days in Branch 215, she was transferred to Branch 261 in Homs, where officers blindfolded her, tied her hands with wire, and hung her from the ceiling in the stress position known as shabeh for three hours.[32] “After 10 minutes, my hands sometimes felt very hot, sometimes very cold. I started to lose feeling. When they set me free, all the blood flowed back into my arms quickly. It felt like boiling oil going into my hands.” Layal said that after she was released she fell down. “A soldier dragged me downstairs by a rope from the wire on my hands.”

In Branch 261, two different male officers forced Layal to perform oral sex on them on two separate occasions.

On January 9, 2013, the government released Layal as part of a swap for Iranian detainees held by anti-government groups in Syria.[33] She left Syria for southern Turkey a few weeks later. Layal has not shied away from sharing her story with the public, but her peers discouraged her from talking about the sexual violence she experienced in detention. “My friends said, ‘Please, keep some details quiet. Rumors will start to spread about you.’”

Layal now lives in the southern Turkish city of Gaziantep with her mother. She has not received any psychosocial support and has not been able to find available services in Gaziantep. She has faced an ongoing struggle with the effects of her detention. “I don’t have any feelings at all– no happiness, no sadness, nothing.”

Hala

Aleppo University became a hub for protests in the spring of 2011 and Hala, a 19-year-old Kurdish woman and first-year student from Aleppo, quickly joined. She and three friends created paintings and caricatures for leaflets and posters distributed at Friday demonstrations. They told few people of their activism. “You risk not just your life but your whole family’s life… You couldn’t trust anyone,” Hala said.

In late May 2011, government forces arrested her father, who had been a Kurdish rights activist for over 30 years. Following the arrest, Hala said her family came under greater scrutiny by security forces, who also became suspicious of Hala’s activism. Security force members began calling Hala: “They said, ‘We are watching you. We know you are still going to demonstrations. We can arrest you at any time.’” They threatened to arrest her mother and brother and kill her father in detention. They searched her home repeatedly and confiscated her computer, hard disks, and documents.

In October 2011, Hala was en route to an activists’ meeting in Aleppo’s Salah al-Deen neighborhood when one of her friends called from the gathering. “I answered my phone and heard screaming,” she said. Security forces were arresting seven of her male friends at the gathering.Two weeks later, Hala saw three of their bodies after they were found on Salah al-Deen’s main road. “They were all blue and purple. I saw burns and marks from electric shock,” Hala said. One month later, security forces informed a fourth friend’s family that he died of an alleged heart attack in detention. Three others remain missing. “We have no idea if they are alive or not,” Hala said.

Hala began helping smuggle medications, blood, and surgical supplies from Aleppo city to surrounding villages in March 2012. She said she felt afraid at checkpoints because of a government crackdown on activists: “The regime was scared of civil activists giving people food and medicine. They were sending a message: ‘If you help, we will kill you.’”

In mid-June 2012, a member of the police force called Hala to come to the station to “chat.” When she entered the police station in the al-Zahiriyah neighborhood in Aleppo, officers blindfolded her and demanded that she reveal the names of activists. Officers tied her hands together and pulled her arms back until her shoulders burned. Hala then heard what she described as the “ta-ta-ta” sound of electricity before she felt shocks: “You know it’s getting close. You feel it. It felt like blood exploding in my mind. It took me 10 minutes to breathe after that. They said, ‘That is just a sample. Now talk.’” When she refused, they shocked her a second time on the leg, then removed her blindfold. “They showed me the voltage machine as they made the voltage higher. They said, ‘Do you want to talk or not?’ I was silent.” They shocked her again and squeezed her fingers with pliers, threatening to crush them.

An officer released Hala after six hours. “They called me two hours later and told me it was just a small sample – if you tell anyone anything, we will do worse.”

After her release, Hala moved to the town of al-Bab, northeast of Aleppo, which was under the control of anti-government groups. There she dressed and sutured wounds as part of a medical relief group. Her father had been released from detention in February 2012 and was living with her family in Aleppo city. In January 2013, Hala left Syria because of threats from the government and what she identified as the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), whose offshoot, the Partiya Yekîtiya Demokrat (Democratic Union Party, PYD), operates in Syria. Hala said that the latter threats were due in part to her father’s activism. “[They] sent messages saying they can reach my family anytime they want. They told my father, ‘We will kidnap your daughter.’” She arrived in Turkey with her mother and brother in January 2013. Her father followed in January 2014. Hala said she would continue her activism inside Syria today if not for the threat of detention. “I don’t care about the barrel bombs or dying, but when you get arrested you die a thousand times.”

Kinda

As one of four “Brides of Peace,” on November 21, 2012, Kinda, 21, a Druze from the southern city of Sweida, marched with her sister and two female friends wearing homemade white wedding dresses in the Medhat Basha market in Damascus’s old city. They carried signs saying, “Syria is for all of us,” “We declare an end to military action in Syria,” and “You are tired, we are tired, we need another solution.” Thirty minutes into the demonstration, security forces arrested all four girls. “It was a peaceful movement that embarrassed the regime,” Kinda said.

They were taken to Military Intelligence Branch 235, a facility also known as “Palestine Branch,” where a male officer interrogated each woman individually.[34] “He [the officer interrogating her] spit on me. He insisted, ‘Who made you do this?’ He searched all over my body. He wanted to touch me, not search me,” Kinda said.

At 2:30 in the morning, after nearly 12 hours, the officer took Kinda and her friends to the office of a captain. “When we entered [the captain] started to shout the worst words I have ever heard: ‘Now I have four whores to entertain myself tonight.’”

The captain began questioning the women. When he came to Kinda, he threatened to torture her and to arrest and torture her father. “He called an investigator and said, ‘Bring me the electricity instrument.’ I could feel my knees shaking from fear. He told the investigator, ‘Take them downstairs. Torture them. I want to hear their screams in my office,’” Kinda said. He also threatened to contact community leaders from Sweida: “He said he would call the sheikhs and bring them here and tell them, ‘These girls from Sweida are working as prostitutes.’ That would destroy us.”

Downstairs, an investigator in a military uniform beat Kinda and hit her hands with four entwined electric cables. Kinda and the others were held in a crowded cell, approximately 3 x 3 meters, with 23 other women.

Kinda said that, while in detention, she was not allowed to contact her family or speak to an attorney. The security forces never informed Kinda of any official charges against her. In January 2013, after nearly three months, the “Brides” were released in a prisoner swap for Iranian detainees.[35] When Kinda returned to Sweida, the government and community targeted her family, now identified as anti-government. “The regime had closed my dad’s restaurant. They had forced my family out of our house,” she said. The family felt ostracized in Sweida and left Syria for Lebanon in May 2013.

At a workshop for young Syrian activists in Turkey, Kinda met Ali, a Sunni Syrian. They soon married. “I am Druze; I am married to a Sunni. This is a crime to my family,” said Kinda, who became pregnant in December 2013. “When news of our marriage reached Sweida, my extended family said that I was disowned and in danger. They said, ‘Your blood is not protected anymore.’ Anyone can kill me at any time.”

Nayla [36]

After the start of anti-government protests in March 2011, Nayla, 52, a teacher from Daraa, adopted a pseudonym to write posts in support of the Syrian opposition on Facebook.

In March 2012, Nayla and a male friend agreed to transport a military defector from Nabak, about 80 kilometers north of Damascus, to Damascus. On the return trip, government soldiers searched their car at a checkpoint and discovered the defector. They seized Nayla’s identification and car keys, took the two men from the car, and began beating them both. “I had another car key with me so I drove away. They followed me and started to shoot,” Nayla said. “All the wheels went flat. I couldn’t control the car. They took me and started to beat me.”

Nayla said the soldiers took them to the Air Force Intelligence Administration in Mezzeh, Damascus, where they blindfolded Nayla and tied her hands behind her back. They forced her to sit inside a car tire and placed a dowel through the gap between her knees and the tire to lock her in a position so that she could not defend herself from beatings. “When they turned me onto my face my feet were up in the air. They beat me with a green plastic stick. They asked me how I knew the defector and why I had him in my car.”[37]

After two hours of this treatment, the officers took Nayla to a small solitary cell, measuring approximately 1 x 1.5 meter. For two days, she was interrogated and denied any food or water. Next to her was a cell housing men. “We were underground and we didn’t know if it was day or night. They used the same plastic boat to give us food as they used in the toilet,” she said. “There were insects like you can’t imagine. I started to scratch myself until my skin bled.”

On the third day, officers brought Nayla to another cell, which they called a “cage,” with other women and girls. Through a small window in the door, Nayla saw injured men who she said appeared to have been tortured. She recounted witnessing a young man crawling on the floor, his feet so blue and swollen from beatings that he could not walk. “You can’t imagine – day and night, the screaming, the crying, the beating,” she said. She described a man of about 30, hanging outside the women’s cell. “His nails had been pulled out. He was talking and talking and talking. They would stamp on his bare feet without the toenails.”

After a few days, Nayla was brought to a room where she found her brother, who was a judge. He had been searching for Nayla and, through a friend’s connections, was permitted to visit her. Within days of the visit, he was arrested by government forces for alleged political support of opposition groups. Following her brother’s visit, Nayla was not permitted to see her family or contact them by telephone, nor was she given access to a lawyer. Her mother and sister later told her that when they tried to visit her, soldiers denied that she was there and told them that no women were held at the facility.

In September 2012, after nearly seven months in detention, Nayla went before a military court on charges of assisting activists, anti-government fighters, and foreign governments. The judge found her innocent but said she had to go before a civilian court, where a judge asked how long she had been in detention. When Nayla told him, “Seven months,” he released her. She said of her imprisonment and subsequent release: “You feel you will never be free again – that you will never see your family, never go to [a proper] toilet. It is a joy just to go to the toilet when you want.”

After her release, Nayla stayed in Syria and immediately resumed her internet activism. “I was afraid, of course. At every checkpoint I was afraid,” she said. In December 2013, Nayla left Syria when friends alerted her that there were rumors government forces were coming to arrest her again. From Turkey, she works to provide aid inside Syria and uses Facebook to support civil society campaigns against arbitrary arrests and detentions inside Syria.

Berivan

“When the revolution started, it was what we had been waiting for,” said Berivan, 24, from al-Hassakah city in Syria’s northeast. A member of the Kurdish minority, which has faced longtime discrimination and persecution by the government in Syria, Berivan was eager for change.[38]

As a student of English literature at Damascus University, Berivan participated in peaceful demonstrations. She moved to the Palestinian refugee camp in Yarmouk in south Damascus to provide aid in November 2012; one month later, government forces began laying siege to the area, not allowing humanitarian assistance in or civilians out. Despite a lack of medical experience, Berivan and her friends decided to open a free pharmacy using medicines left behind by pharmacists and abandoned clinics. Eventually they also began training civilians in emergency medical care.

Nearly a year after her arrival in Yarmouk, in September 2013, the presence of Islamist and extremist armed opposition groups, including Liwa’ al-Islam (also known as Jaysh al-Islam) and the Islamic State of Iraq and Sham (ISIS), expanded in Yarmouk. “It became a problem because I was a woman, unmarried, an activist, unveiled, and working at the ‘front line’ in the medical field,” Berivan said. Liwa’ al-Islam, headed by Zahran Alloush, arrested Berivan at a friend’s house where she was preparing a medical relief mission to Ghouta, in the Damascus suburbs.

Liwa’ al-Islam members took her to a house in Hijra in the Damascus countryside. They said she was being held for working with and providing medical treatment to men, not wearing the hijab(headscarf), and acting as a government spy. They called her kafir, a derogatory term used by Muslims for a non-believer, and accused her of working with the Kurdish PKK, affiliated with the PYD. They also pressed her for information about leaders from the anti-government Free Syrian Army.

After several days, the group’s members admitted they had no evidence against Berivan but told her that they would continue to detain her. “They said, ‘Your file is clean. You are a guest here. You need time with your god.’” Berivan refused to eat for eight days. When she resumed eating, she became violently ill and Liwa’ al-Islam released her, after 10 days in captivity.

Berivan re-opened the unofficial pharmacy in besieged Yarmouk, but she took precautions in an effort to protect herself and her work. “After I was released I wore the hijab. I changed how I looked because of them,” she said, referring to the extremist armed groups present in the area. In late November 2013, ISIS fighters forced her to close the pharmacy and threatened her because she was wearing the hijab but not the abaya, a loose-fitting full-length robe. “They said, ‘If we see you like this again, we will kill you. If we ever see you in this area, we will hang you.’”

Before her detention, Berivan said she had treated many wounded from Liwa’ al-Islam, ISIS, and other armed groups in the area, and they knew her well. “The worst part was that it wasn’t even the regime who arrested me; it was people with whom I was suffering,” she said. Aided by friends and activists, Berivan left Yarmouk in February 2014 and went to Turkey a month later because she was wanted by both extremist armed groups and by government forces for providing humanitarian assistance in an area under government siege.

For Berivan, being in Yarmouk was a choice. “The problem is there are lots of people still there and it is not their decision,” she said of those trapped in besieged areas. She emphasized the strength of women in the community. “They are strong, and they are fighting. They are suffering. They don’t want to leave.”

Maisa

In early 2012, Maisa, a 30-year-old intensive care nurse from Damascus, was one of a group of young doctors and medical students who began procuring medical supplies and treating wounded at makeshift field hospitals in government-controlled areas in Damascus countryside governorate, outside of Damascus city.

“I felt like my life was threatened all the time because the regime didn’t permit anyone to treat people from the opposition,” she said. She said government security forces had already targeted her for her peaceful activism; she moved houses several times and left her job as an intensive care nurse in Damascus after security forces searched for her repeatedly at home and work in early 2011. “They would say, ‘We are following you. We are keeping our eyes on you,’” she said

At the end of 2012, Maisa stopped her medical work and started a small organization to support women’s rights and local political participation. In January 2013, she also began hosting a weekly program on Orient TV, a pro-opposition satellite station, showcasing interviews with activists. “I hid my face under a veil and used a different name so the regime wouldn’t know it was me,” she said. Maisa said that the government found out about her work with Orient-TV from a fellow activist who revealed it under torture.

In April 2013, government security forces arrested Maisa and 11 friends in a café in the Sarouja neighborhood of Damascus. They took her to Military Intelligence Branch 235 (the Palestine Branch), where she said they beat her throughout the night with a thick, green, stick-like hose. “They slapped me on the face. They pulled me from my hair. They hit me on my feet, on my back, all over,” she said.[39] Security officers searched her home and seized her computer and documents. “They found a revolutionary flag pin and they started to hit me,” she said.

Maisa said she suspected that the security forces did not subject her to further torture because they feared her high profile in media and activist circles. She was held in the Palestine Branch for four months. “I never got to talk to anyone in my family. I never got a lawyer,” she said, and laughed at the suggestion that it would have been a possibility.

In July 2013, security forces transferred Maisa to Rukn al-Deen and then Kafr Sousseh police stations, where she was held for 20 days. “Kafr Sousseh was the really bad time,” she said, recounting men in police uniforms sexually harassing and torturing other female detainees. “I used to hear a woman screaming,” Maisa said. She saw the woman, handcuffed and naked, alone in a cell. “Once they brought her to our cell and made her beat the other women. Her body was defaced. It was all blue,” Maisa said.

Maisa said that the security forces at Kafr Sousseh fed the criminal detainees but not the political ones. Women who had personal funds would sometimes pay the security forces to get them food or other supplies. “To get food or make phone calls, some women would have sex with the policemen,” Maisa said.

In late September 2013, nearly a month after she had been transferred to Adra prison, security forces took Maisa to the counterterrorism court, where the judge upheld her detention for supporting terrorism and armed groups, working with Orient TV, and founding an armed group.[40] In October 2013, the regime released Maisa in a prisoner swap brokered by Lebanon, Turkey, Qatar, and the Palestine Authority.[41]

Upon her release, Maisa learned that ISIS had arrested her sister, Samar, in Aleppo in August 2013 for civil activism and not wearing the hijab. “My mother is still searching for her daughter,” said Maisa. At the time of writing, the family had no confirmation of Samar’s whereabouts.

Maisa resumed her activism in Syria but felt she had to leave in early 2014 after government forces arrested fellow activists and started following her again. Forbidden by the government from traveling, she went to Lebanon illegally and then to Turkey in April 2014. While she was at the Syria-Lebanon border, security forces searched her house in Damascus, arrested her cousin and a friend, and imprisoned them in Adra Central Prison in Damascus. “They forced them to do interviews on Syrian TV to say I supported them with weapons and that I was part of a terrorist group,” said Maisa. “My cousin didn’t even have anything to do with the revolution.”

“It Had Turned to Hell”: Impact of Attacks on Civilians

|

In Syria, violations of international humanitarian law and the laws of war, including indiscriminate and disproportionate attacks on civilian-populated areas, have had a significant and specific impact on women. Government forces have used artillery, incendiary weapons, barrel bombs, and chemical weapons in heavily populated areas under the control of non-state armed groups, resulting in substantial civilian casualties and deaths. [42] According to the Syrian monitoring group Violations Documentation Center (VDC), 266 government air strikes in Aleppo between November 2013 and February 2014 killed over 1,395 people, all but 14 of whom were civilians. [43] As of May 23, 2014, VDC reported 10,360 civilian deaths as a result of aerial attacks since January 14, 2012. [44] These include deliberate attacks against civilians and indiscriminate attacks—that is, attacks that did not or could not distinguish between civilians and combatants. Syrian government air strikes that have deliberately or indiscriminately killed civilians appear to be part of systematic and widespread attacks against the civilian population. Non-state armed groups opposed to the government have also carried out deliberate or indiscriminate car bomb and mortar attacks in government held territory. [45] Deliberate, disproportionate, and indiscriminate attacks on civilians or civilian objects are prohibited by international humanitarian law. Those who commit such acts or fail to take precautions to prevent civilian deaths and destruction of civilian property may be guilty of war crimes. [46] Civilians are also suffering because of restrictions on humanitarian operations by government and, in some instances, non-state armed groups. In defiance of Security Council Resolution 2139 (2014), which was adopted on February 22, 2014, and demands lifting of sieges and facilitation of cross-border humanitarian aid, the government of Syria has refused to allow aid to enter the country through border crossings held by non-state armed groups and blocked humanitarian aid deliveries to areas under siege, resulting in lack of medical care and supplies, widespread malnutrition and, in some cases, death from starvation.[47] In some areas, armed opposition groups have also imposed sieges and blocked humanitarian aid, whether by assaulting aid providers or denying access to aid convoys.[48] These actions violate international humanitarian law, which requires all parties to the conflict to allow and facilitate the rapid and unimpeded passage of humanitarian aid to civilians at risk, including in areas under siege.[49] Indiscriminate and disproportionate attacks on civilians impact women significantly, resulting in their increasing role as caretakers, primary wage-earners, and heads of household. As civilians face increasingly desperate circumstances with ever more restricted supplies, and as men’s presence and ability to fulfill their traditional roles dwindles, growing numbers of female-headed or female-supported households have emerged. Families and communities are relying progressively more on women to procure and distribute humanitarian aid, care for the injured and disabled, and support families. |

Fathya

In August 2012, Fathya, 25, and her husband, Adib, then 39, returned to their home in the al-Hara al-Kablie neighborhood in Azaz in Aleppo countryside to celebrate Ramadan with their family. They had previously left for Aleppo city with their young children when the armed conflict approached Azaz.

After bathing her children, Fathya set them on a blanket where their father lay sleeping. She was cleaning the bathroom when something suddenly felt wrong. “My eyes started to blink. I hit the walls from side to side. It felt like hot water and electricity in my body,” she recalled.

Fathya thought she was dying before realizing that she was buried in rubble, with only a small hole letting in light and air. “I screamed for my husband to come help because I thought the explosion was only in the bathroom,” she said. A neighbor heard her and brought others to dig her out. “I felt horrible pain when they tried to take the rubble off. I felt like my flesh was coming out with it,” she said. Once freed, a relative held her tightly to close a gaping wound across her abdomen.

After eight days in intensive care at the hospital in Kilis, Turkey, Fathya was told her husband and two of her children, Shahoud, 9, and Amani, 3, were killed in the air strike. Her other children, Ahmed, 5, and Youssef, 10, survived. Youssef suffered internal injuries and serious damage to his arm and hand, which he still has difficulty using. “He started crying this morning while he was doing his schoolwork because he couldn’t write,” Fathya said.

During the attack, which Human Rights Watch investigated two hours after it had occurred, a fighter jet dropped at least two bombs, destroying a block of homes, killing over 40 civilians, and wounding over 100 more.[50]Two opposition Free Syrian Army facilities were in the vicinity of the attack and may have been targets of the Syrian aircraft though neither facility was damaged in the attack.

Fathya, who now lives with her parents, sons, brother, and in-laws in Gaziantep, said she clings to the blanket on which her family was resting at the time of the attack, which bears two burned-out holes from the bombing. “The blanket was covered in blood. I cleaned it and now I can’t sleep without it. My mother tried to throw it away and I screamed,” she says. “Now I may have a happy face on the outside, but inside there is something wrong.”

Amal

“My only remaining child is my son,” said Amal, 44, pointing to the 10-year-old sitting by her side. Amal’s four other children – boys aged 17 and 7, and girls aged 14 and 4 – were killed when their Aleppo home was struck by a barrel bomb in July 2013.[51] Amal, her husband, and their son were about one kilometer away. “When we heard the barrel bomb I said to my husband, ‘God help those have been bombed.’ Then I found out it was my house and I lost my children.”

The family’s single-story home near Aleppo city’s historic citadel was destroyed in the attack. Prior to the bombing, Amal’s family felt relatively safe; the area was under government control and she said no armed groups were present near their home before or during the bombing.

“We saw the helicopter. We saw when the barrel was thrown out,” she said. “At first I thought they were throwing food to the regime troops.”

Shortly after the bombing, Amal’s husband, previously the keeper of a small shop, suffered a heart attack and stroke that left him partially paralyzed and unable to speak. The family had moved to the opposition-controlled area of Aleppo and Amal said medical care was inaccessible.

Amal’s husband gradually regained some speech but cannot use his left arm or leg. “I wash him, feed him, and take him to the bathroom,” Amal said. They left Syria for Turkey in late March 2014 to seek physical therapy and health care. At Kilis hospital, doctors said her husband’s heart problem requires specialized care. “I said we have no money,” Amal recounted. “They said, ‘Then there is nothing we can do.’” In Kilis, where Human Rights Watch interviewed Amal, the family was sleeping in an open park and relying on a restaurant that provides free meals to Syrian refugees.

Amal hopes that her son will ultimately resume his studies. “My son is afraid to go to school because a barrel bomb fell on the school where he was. But I hope he will go to school,” she said. Then, smiling and nudging him insistently, she added: “He will go.”

Roula [52]

“When the revolution started, I was a normal woman with a normal family,” said Roula, 38, a wife and mother of five from the northern Syrian-Turkish border town of Jarablus. Roula said she saw civilians suffering, especially widows. “I felt very angry that I couldn’t do anything to help them,” she said.

Roula said that the five camps for internally displaced people (IDPs) that had sprung up in Jarablus were crowded and lacked services. In January 2013, she started an organization to provide education for children and income-generation projects for women whose husbands had been killed or detained.

When her husband lost his job, Roula and her family moved across the border to Karkamis, Turkey, in early 2012. For two years, Roula travelled to and from Jarablus almost daily, but she said this became difficult when the Turkish government closed the border crossing after ISIS took control of it in January 2014.[53] She said she must now pay 50 Turkish liras (about US$24) for someone to smuggle her across the border illegally.

Roula said that her work in Jarablus also required clever negotiation with ISIS, which was present in the area as early as July 2013.[54] In November 2013, ISIS members tried to block her from entering the IDP camps. To convince them otherwise, Roula said she used ISIS’s own tenet demanding separation of the sexes: “I said, ‘In the camps, there are women and children without men. It is improper for you to go and talk to them. Let us do it.’” ISIS permitted her entry and even allowed her to begin women’s literacy classes. “ISIS said we can teach them to read and write, and maybe a bit of math, but that is all. We cannot teach them anything else,” Roula said.

Roula said that in January 2014, ISIS began strict enforcement of a dress code in Jarablus: “They forced all the women to wear hijab (headscarf) – even girls aged six or seven. Now, since March 2014, they make every woman and girl wear the niqab (veil covering the entire face except the eyes). Females also have to wear the abaya (full-length robe) – even small children.”[55] According to Roula, ISIS also restricts women’s presence in public. “If a woman is alone she has to be with a man from her immediate family. It has to be her father, husband, brother, or son – it cannot even be a cousin.”

Roula said that crossing the border illegally was difficult but that she planned to resume her frequent trips. “I was really terrified. But I expect the next time I will be braver.”

Aisha

Aisha, 45, was at the market in al-Khaldiyah in Aleppo city on February 7, 2013, when she was shot by a sniper. “I was in the middle of the street trying to buy vegetables. It was an uncovered area. The bullet entered me on the back of the neck,” Aisha said. X-rays reviewed by Human Rights Watch showed a bullet lodged at the top of her spine. Doctors performed emergency surgery, but said she would require a lengthy recovery period and physical therapy. “The doctor said I would be disabled,” Aisha said.

“I can’t really use my left hand very much. I can’t use my legs,” she said. In March 2013, she and her family came to Gaziantep, Turkey, where she is largely confined to a first-floor bed in the house she shares with her husband, five sons, three daughters, and their children. Her daughters care for her.

Aisha said that there were no armed groups present when she was injured, but that snipers had been active in the area. “It was all civilians who were shot and all in the same neighborhood,” she said. Family members confirmed that local residents had attempted to block snipers’ sight lines by draping blankets and other coverings over the open market.

Aisha and her family have tried to find free physical therapy, but as of April 2014 she had not had any rehabilitation treatment for one year. “We have been trying to get physical therapy, but at the clinics they kept saying, ‘It’s not your turn,’” she said. Three months ago, Aisha said she was accepted for one month of physical therapy at each of two hospitals in Adana, Turkey, and she is eager to begin. Occasionally, Aisha’s children bring her outside in the wheelchair. “Mostly she is just in that bed,” said Aisha’s daughter.

Maha

“For three months, I had a feeling that one of us was going to die,” said Maha, now 28, a former first grade teacher from Aleppo city. She and her husband, Mustafa, were part of a local civilian activist group promoting peaceful change and democracy. Newly married, in mid-November 2012 Maha and Mustafa, 30, went with two friends to participate in a weekly anti-government demonstration following Friday prayers in the Bustan al-Qasr neighborhood of Aleppo. Maha said that the demonstration consisted of civilian activists and local community members. After it concluded, she and her friends stood chatting in front of the mosque when government shelling hit the area.

“I felt something falling above me and I started to run. I turned back and saw dust,” Maha said. “I looked for Mustafa… I couldn’t find him. I started looking through the bodies.” Maha saw one of their friends on the ground, bleeding profusely. She discovered that Mustafa had been taken to the hospital.

“I went to the hospital. I saw a child without legs. I saw every kind of injury. But my only worry was: where is Mustafa?” Doctors told Maha that Mustafa required surgery for injuries to his lungs and abdomen. Several hours later, they told her that he had died during the operation. Thirteen others also died that day; twenty-one people, including the friend Maha saw bleeding, were injured.[56]

Maha said she felt shocked and hopeless. She left Syria three weeks later, in December 2012, and has only returned once since that time. Her brother, Hussein, a well-known human rights blogger, has been detained by government forces since February 16, 2012, when he was arrested with colleagues Mazen Darwish and Hani Al-Zaytani at the Syria Center for Media and Freedom of Expression.[57] Maha’s sister, Nuha, was detained for 23 days in August 2012 by pro-government militia members who attempted to use her as leverage for a prisoner exchange with the FSA.[58]

The organization that Maha and her friends founded has resumed work inside Syria, but for now Maha works with them from Turkey. According to Maha, such grassroots civilian organizations form the backbone of the uprisings in Syria. Yet she said their work and message have been overshadowed by the violence and chaos that have become synonymous with the Syrian conflict. “On the news you only see blood and destruction,” she said. “You don’t see that behind it, there are civilian groups doing things peacefully.”

Warda [59]

After her husband lost his job in February 2014, Warda, 42, and her family left the Tariq al-Bab neighborhood of Aleppo for Turkey. On February 6, 2014, they arrived at the Bab al-Salam border crossing, which Warda said was crowded with people fleeing barrel bombings in Aleppo.[60] Turkish border police moved those without passports, like Warda and her family, to one side and an officer encouraged them to cross unofficially, said Warda. She said that he told them that the families had to cross one by one. “Everyone was in a hurry to get in before nightfall. People started to try to cross in big groups.” Warda, her husband, 49, and her 7 children, ages 4 to 23, sat in a circle to the side of the crowd, 3 to 4 meters from the officer. When people rushed the border, she said, the officer tried to slow them by firing his gun. “The first thing I saw was my son with blood on his neck,” Warda said of Muhammed, 8, who was wounded but survived.

Warda said she heard the gun fire four or five times. Initially, she did not realize that her husband, 49, was injured in his arm and abdomen. Her sons carried him across the border. An ambulance took him to Kilis hospital, where Warda said doctors told her they did not have adequate equipment to treat him. They sent him to the hospital in Konya, where, according to a hospital report, he died of his injuries. An autopsy was performed, but doctors did not provide the full report to the family.

Police in Kilis spoke to Warda and told her she could file a report about the incident. She said the police questioned her for about five minutes, but the Arabic translator remained for only part of that time so she did not understand everything the police said. As far as she knows, the police did not speak with her husband before he died. At Kilis hospital, Warda said her husband was conscious and encouraged her to file the police report. She said that the translator, however, dissuaded her. “He told me, ‘If you talk, huge problems will happen. Don’t waste your time.’” She does not know who the translator was or for whom he worked. She decided not to file a police report. Since that time, no authorities have questioned Warda about the incident.

A scar now marks the spot on Muhammed’s neck that required two stitches after the incident. Two of Warda’s sons found work in Gaziantep and the rest of the family works at home, attaching fabric segments to make sandal tops for a Turkish workshop. She said they earn 3 Turkish liras (about US$1.41) for every 200 pieces they assemble. “At first when we arrived here we were desperate to work. They gave us 15 Turkish liras (about US$7.13) for 1,000 pieces,” she said.

Warda said she does not know what happened to the border officer who fatally injured her husband and wounded her son, but that two higher-ranking officers slapped him and threw him to the ground after the incident. Warda said she is no longer afraid to file a report as long as her children can remain in Turkey. “I don’t want anyone to send them back to Aleppo. That’s why I am afraid to say anything against the Turkish government.”

Safiya [61]

“It was like it had turned to hell. The army was everywhere – in every street and every corner,” said Safiya, 35, of Jisr al-Shaghour after Syrian government forces entered her town en masse in June 2011.[62] Safiya lived in the Idlib governorate town with her husband and four children. She taught physics and chemistry at surrounding villages’ schools.

Safiya said that government security forces verbally and physically abused people at roadside checkpoints: “They said things to me like, ‘You are a woman of Jisr al-Shaghour. We should do more to you. We should rape you.’” Safiya had a paper identifying her as a teacher, which usually allowed her to pass more easily. “But I couldn’t stand how they were treating others at the checkpoints. I saw them hitting and arresting men,” she said. She left her job in November 2011 to avoid regular travel on the roads.

Safiya’s husband operated a pharmacy and an internet café in Jisr al-Shaghour. Even before the first uprisings in Syria, military security demanded that he register and provide monthly lists of café users’ identification information, especially those who used Facebook or YouTube. “The security forces said, ‘If you don’t give us the names, we will shut you down,’” Safiya said.

In May 2012, security forces entered the couple’s home and detained Safiya’s husband. “They told him, ‘Come with us for one hour. Bring some money and then we will bring you back,’” Safiya said. She does not know what branch the security forces were from or where they took her husband. In July 2012, a family friend released from detention said he had seen Safiya’s husband being held by security forces at Kafr Sousseh station in Damascus. “This was the last news I heard of him,” she said.

Safiya began teaching at the Syrian School in the Turkish town of Kilis (Madrassah Soriyeh Kilis) in December 2012, a month after her family left Syria for Turkey. Out of 18 family members living together in Kilis, Safiya is the only one with a steady job. Others send what money they can. “It is just enough to help us stay alive,” Safiya said. Her father suffered from heart disease and needed surgery. “We couldn’t afford it, so he died four months ago.”

Salwa

In October 2013, Salwa, 40, was refueling the oven in her kitchen in the Sheikh Najar neighborhood of Aleppo when she heard a low whistling sound, similar to that of an airplane. A tank shell hit the house and the cooking gas canister caught fire. Salwa and her daughter Kafaa, 5, who was beside her, were severely burned during the attack.

Salwa said that there were no armed groups in the direct vicinity of the house, but a Free Syrian Army group was on one side of the neighborhood and government troops on the other. Salwa’s home was one of several caught between the two fighting groups, less than three kilometers from each. When airplanes began shelling early that morning, the family was trapped in the midst of the fighting. After the shell struck the house around 5 p.m., Salwa’s brother brought her and Kafaa to a hospital via back roads. When Salwa’s husband later returned to the site of the attack, the house had been destroyed.

Salwa underwent a skin graft for the burns on her neck, but the doctor in Turkey told her it was unsuccessful. She cannot use her burned left hand, which became infected, and suffers constant pain. Thick scarring from severe burns on Kafaa’s face prohibits her from opening her mouth fully, which her parents said inhibits her ability to eat. Doctors in Turkey have told them that Kafaa cannot have additional reparative surgery until she is at least 15. “We are afraid for her future and what will happen to her. We feel pain for that.”

Jelnar

Jelnar, 27, had completed her pharmacist’s degree and was a corporate pharmaceutical representative in Damascus when the uprisings in Syria began. An Alawite from Tartous, a coastal city with a population largely loyal to the government, Jelnar nevertheless immediately joined peaceful protests and later provided humanitarian assistance.

Forced to leave her job due to rising insecurity, in July 2012 Jelnar volunteered as a pharmacist for internally displaced people living at a school in the besieged Palestinian Yarmouk refugee camp in Damascus. Women approached Jelnar, the sole female staff member, when she was alone in the clinic. “If a woman was veiled, she wouldn’t uncover even her hand to show a male doctor,” she said. “For these women, I was the only one there who could help. One woman didn’t show a rash to anyone for a week because the doctor was a man.”

Jelnar rationed scarce medical supplies. “I would give a woman just one pill and tell her to come back for another one the next day,” she said. “What if, in the meantime, someone else needed it urgently?” To carry medications between Damascus and its suburbs, Jelnar showed her pharmacists’ syndicate card or documentation from her time as a pharmaceutical representative. “It was signed and had a seal on it, saying that I had to have medicines and take samples to doctor’s offices. When I left my job I kept that paper and used it to smuggle medicines,” she said.

“It’s impossible not to feel afraid at checkpoints. Your biggest fear is that they will use your arrest to pressure your family. Or what if you can’t stand the torture and give up information?” she said.

Using her background as an Alawite from Tartous, Jelnar initially convinced security forces she was not aiding pro-opposition groups in any way. In February 2012, security forces moved next door to the home Jelnar shared with friends in Damascus and began questioning them regularly. Without a steady income and facing increasing insecurity, life in Damascus became untenable. In late 2012, Jelnar left for Turkey, where she works for an international assistance program operating in northern Syria.

Tiba

Between March and June 2012, Tiba, 36, her husband and four children moved more than five times, seeking safety in and around Aleppo. When barrel bomb attacks began in Aleppo in the summer of 2012, they returned to their home in Hreitan, a northwest suburb of Aleppo city. “If you are going to die anyway, it is better to die in your home,” Tiba said.

Tiba was at the Abd al-Latif Barakat School, where she taught five- and six-year-olds, when it was damaged by shelling from helicopters in April 2012. No one at the school was injured, though Tiba said there were casualties on the surrounding streets. According to Tiba, no armed groups were ever at the school or in the area nearby, though she said there was a government checkpoint next to the entrance to Hreitan. “Whenever the rebels attacked it, the regime would target the town with shelling,” she said.

The increasing attacks hindered Tiba’s ability to work, especially when the family was living outside of Hreitan. Bombings often prevented her from traveling to work at the prescribed time. “I had to take many days off because of the attacks,” she said. Students also stopped attending either due to displacement or fear. “People were paranoid when they heard airplanes and bombs,” she said. “Students were very afraid, so they didn’t leave their houses.”

Tiba’s family left Hreitan for Turkey in September 2012 and she began teaching at the Syrian School in Kilis (Madrassah Soriyeh Kilis). Though her husband, formerly a government electric employee, has found periodic work, Tiba is the family’s primary breadwinner. “This is a big difference in Syrians’ lives.” She said that this shift takes a toll on the family. “Women have to reassure their husbands: ‘I am not the man now just because I am making the money.’ My husband had a good job in Syria and suddenly he found himself doing nothing at all. It is really hard for him mentally and emotionally.”

Zeinab

“First my son was killed, then my husband,” said Zeinab, 42, from Daraya, Damascus. In early December 2012, Zeinab, her husband, two sons, and daughter moved from their house in Yarmouk camp to the nearby Abdul Qader Husseini mosque for safety. Zeinab said that about 75 families were living in the mosque and its interior garden when a rocket struck on December 16, 2012, killing at least 15. According to media reports, Syrian air strikes hit the mosque in an attack on Yarmouk after anti-government armed groups attempted to seize control of the camp.[63]

After the bombing, Zeinab searched for her older son, Muhammad, 16, for four hours before discovering he had been taken to the hospital, where he died of his injuries. Metal and wooden shards damaged the eyes of Zeinab’s younger son, Sammy, 15. After surgery in Syria, he has partial vision in one eye.

Following the bombing, Zeinab’s family stayed with extended family members in and around Damascus. In March 2013, a sniper shot and killed Zeinab’s husband when he returned to Yarmouk to ascertain the condition of the family’s home.

A charity organization funded half the cost of Sammy’s medications as well as the family’s move to Turkey in early July 2013. In Turkey, Zeinab, Sammy, and her daughter, Asma, picked fruit and olives for two months to earn money. Zeinab said that the agricultural work exacerbated Sammy’s condition. “Even the sun hurts his eyes,” she said. Asma now attends school, but Sammy does not because of his impaired vision.

At the end of the agricultural season, Zeinab found and registered with the Ulfah Project, a charity that uses private funds to support female-headed households, including widows and their children. Zeinab is the head chef at the organization’s income-generation project, through which women prepare lunches that local businesses and organizations purchase for meetings and events. Ulfah Project is also helping to purchase Sammy glasses, which doctors in Gaziantep said will improve his vision.

Recommendations

Since the beginning of the Syrian conflict in the spring of 2011, Human Rights Watch has repeatedly issued detailed recommendations concerning steps that the UN Security Council, the governments of Syria and other countries, and other parties to the conflict should take in order to address violations of international human rights and humanitarian law and prevent further violations in the course of this conflict. These recommendations, as well as extensive documentation of arbitrary arrests and detentions, enforced disappearances, indiscriminate attacks, executions, and hostage-taking of civilians, have endured for over three years, yet little progress has been made to curb these abuses. The government of Syria and non-state armed groups continue to flout international human rights and humanitarian law, as well as UN Security Council Resolution 2139 on humanitarian access.[64] Despite the seeming intractability of the conflict and ensuing human rights and humanitarian crisis, it is imperative that the UN Security Council and concerned governments around the world remain vigilant in working to end such abuses by imposing an arms embargo and targeted sanctions and referring Syria to the International Criminal Court and using other mechanisms to ensure accountability for abuses.

The UN Security Council and other concerned governments should impose an arms embargo on Syria’s government, as well as on any non-state armed groups implicated in widespread or systematic human rights abuses. They should require states to suspend all military sales and assistance, including technical training and services, to the Syrian government and abusive non-state actors until Syria and such non-state actors end unlawful attacks against civilians, given the real risk that the weapons and technology will be used in the commission of serious human rights violations.

Concerned governments should continue to press for accountability and justice in Syria. Despite Russia’s and China’s May 22, 2014, veto of a Security Council resolution to refer the case of Syria to the International Criminal Court, over 60 countries from all regions showed support for the resolution.[65] These and other governments should remain committed to seeking justice for victims in Syria, whether in the Security Council, UN General Assembly, UN Human Rights Council, or through other avenues including the use of universal jurisdiction.[66] Members of the Security Council should also increase pressure on Syria’s allies, including Russia and China, to end efforts to block effective Security Council action on Syria.

In accordance with UN Security Council Resolution 2139 and international humanitarian law, all parties to the conflict should facilitate rapid and direct humanitarian aid operations by permitting agencies secure access to all areas of Syria, whether held by government or non-state forces. Likewise, in accordance with the same, the UN and concerned governments should support and undertake full-fledged humanitarian aid operations designed to reach all those in need by the safest and most direct routes. Concerned governments should expand funding for humanitarian aid for all Syrians, both inside Syria and in refugee settings, and ensure that such aid includes easily accessible medical, psycho-social, and rehabilitative services for victims of all forms of abuse, torture, trauma, and war-inflicted injuries. This should include urgent access to essential medical and psycho-social services to survivors of sexual violence. Concerned governments should also ensure that all financial assistance supports the particular economic and social needs of female-headed households, including through cash assistance and material grants as well as vocational and income-generation opportunities. Further, donor governments should insist that aid distribution takes into account the specific needs and vulnerabilities of women and girls to ensure that they access essential goods and services safely and readily.[67]

States bordering Syria should ensure refugees from Syria can seek asylum at their borders or enter their territories and claim asylum in-country. They should abide by the customary international law prohibiting refoulement, which bars States from returning anyone to a place where his or her life or freedom is threatened or where he or she faces real risk of torture or inhuman or degrading treatment. [68] Those States should take all necessary steps to ensure respect for asylum seekers’ rights at border crossing points, including by training border guards and holding those committing refoulement and other abuses against asylum seekers to account. As home to a growing refugee population from Syria, neighboring countries have already taken on an enormous burden, which is putting immense strain on resources, public services, and local populations. To ensure that countries continue to assist and protect refugees from Syria, donor governments should greatly increase their funding of the UN’s Syria refugee appeal and should step up direct support to neighboring countries receiving refugees. [69] Moreover, countries outside the region should accept increased numbers of refugees from Syria for resettlement. [70] European Union (EU) member states should end unlawful pushbacks of Syrians at their borders and ensure refugees from Syria can safely access EU territory. [71] They should also ensure that refugees can access channels to lodge asylum claims and claims for other forms of protection, and that these are processed fairly and efficiently. [72]

Moreover, concerned governments should publicly condemn the use of arbitrary arrest, abuse, and torture in detention by government and pro-government forces and armed opposition groups. The government of Syria and non-state armed groups should immediately cease all arbitrary detention and torture of civilians in Syria, as well as abductions and forced disappearances, and release all those who have been arbitrarily detained. They should also provide immediate and unhindered access for trained, recognized international detention monitors to all detention facilities, official and unofficial. These should include monitors of the office of the UN Commission of Inquiry (COI) on Syria.

In accordance with UN Security Council Resolution 1325 and the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), which the government of Syria ratified in 2003, and the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women’s General Comment 30, all parties to the conflict should take measures to protect women and girls from all forms of violence during conflict, including but not limited to sexual and gender-based violence.[73] This includes preventing abuse and holding those who commit such abuse to account. In addition, the government of Syria should ensure that survivors of sexual and gender-based violence access essential medical and psychological care, as well as economic and social support.[74] The government of Syria should take measures to provide survivors of physical abuse, torture, and sexual violence, particularly those in detention or other government-operated facilities, with access to vital and comprehensive services, including medical and psycho-social care.[75]

The UN Security Council and other concerned governments should also publicly condemn discriminatory restrictions on women and pressure those responsible to eliminate them. Non-state armed groups should immediately and publicly rescind all policies that violate women’s rights, including mandatory dress codes and limitations on freedom of movement, and cease punishing and threatening women and girls whose dress or behavior does not conform to such rules. They should also halt unlawful interference in women’s and girls’ rights to privacy, autonomy, freedom of expression, religion, thought, and conscience and punish those under their command who restrict women’s dress and access to work, education, or public space.[76]

In line with both CEDAW and Resolution 1325, States should eliminate discrimination in all aspects of political and public life, including by ensuring women’s fair and effective participation in government bodies and formulation of policy at national, regional, and international levels. [77] The UN Security Council, Syrian government, and other concerned parties should ensure women’s full and meaningful representation and participation in all future peace talks or negotiations, as well as in subsequent policy-making and peace-building processes. [78] Concerned governments should support initiatives to ensure women’s access to decision-making processes at all levels and on all sides, as well as activities to build women’s capacity to engage fully in political processes at the local, national, and international level.

Acknowledgements

This report was researched and written by Hillary Margolis, researcher on women’s rights in Syria for the women’s rights division at Human Rights Watch. Samer Muscati, emergencies researcher for the women’s rights division, took the photographs used in the report and also contributed to its research and writing.

Camille Pendley, associate for the women’s rights division, and Diana Semaan, research assistant on Syria and Lebanon, provided research support.

The report was reviewed by Liesl Gerntholtz, women’s rights director; Nadim Houry, deputy director for the Middle East and North Africa division; Lama Fakih, researcher on Syria and Lebanon; Bill Frelick, refugee program director; Gerry Simpson, senior researcher and advocate for the refugee program; Emma Sinclair-Webb, senior researcher for the Europe and Central Asia division; Priyanka Motaparthy, researcher for the children’s rights division; Clive Baldwin, senior legal adviser; and Tom Porteous, deputy program director. Fred Abrahams, special advisor for the program office, also reviewed sections of the report. Annerieke Smaak assisted with proofreading, footnoting, and formatting. Grace Choi, publications director, provided photo editing and layout design. Production assistance was provided by Kathy Mills, publications specialist, and Fitzroy Hepkins, administrative manager.

Human Rights Watch would like to express our deep appreciation to all the women who shared their stories and images with us for this report, as well as to all those who provided support and assistance to us from and in the field. We would also like to thank the Violations Documentation Center for their assistance in our research.

[1] Human Rights Watch interview with Maha, Gaziantep, Turkey, April 8, 2014.

[2] Ibid.

[3] To gather material for this report, Human Rights Watch researchers traveled in March and April 2014 to the southern Turkish border towns of Gaziantep and Kilis, where they interviewed and photographed 27 female refugees from Syria and spoke with individuals from seven civil society groups and humanitarian aid agencies offering services to refugees from Syria. Human Rights Watch conducted in-person interviews with all of the women included in this report, often with the assistance of Arabic-language interpreters. In some cases, family members also participated in interviews. All interviewees gave permission for us to use their statements and images. Human Rights Watch talked with interviewees about their lives prior to the conflict, their experiences during the conflict, their decision to leave Syria, and their lives since becoming refugees. We asked about their own and their family members’ experiences of activism, detention, abuse, torture, injury, and impact of the conflict on their daily lives. Where requested or deemed necessary for security reasons, we have changed names and omitted identifying details of interviewees. In all other cases, those profiled have given consent to use their names and all information included herein. Where possible and with consent of interviewees, Human Rights Watch helped to connect interviewees to appropriate medical, psychosocial, and protection services. The Syrian activist community in southern Turkey consists largely of refugees who have opposed the Syrian government and therefore, Human Rights Watch did not interview any female refugees who self-identified as government supporters. As of June 11, 2014, the United Nations refugee agency (UNHCR) reported that Turkey was host to over 773,000 registered refugees from Syria, 71 percent of whom live outside of refugee camps. “Syria Regional Refugee Response: Turkey,” UNHCR (accessed June 15, 2014), http://data.unhcr.org/syrianrefugees/country.php?id=224.

[4] Human Rights Watch interview with Jelnar, Gaziantep, Turkey, April 2, 2014.

[5] Human Rights Watch interview with Layal, Gaziantep, Turkey, April 1, 2014; name of interviewee has been changed at her request.

[6] Human Rights Watch interview with Zeinab, Gaziantep, Turkey, April 6, 2014.

[7] Human Rights Watch interview with Aisha, Gaziantep, Turkey, April 8, 2014.

[8] As of May 26, 2014, the Syrian monitoring group Violations Documentation Center (VDC) reported that 10,631 civilian women and girls have died in the conflict. See VDC database at https://www.vdc-sy.info/index.php/en/ (accessed June 13, 2014). In a November 2013 report, the Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR) said that the organization had documented over 10,850 female civilian deaths, including more than 3,600 girls. See Syrian Network for Human Rights, “Syrian Women,” November 25, 2013, http://sn4hr.org/public_html/wp-content/pdf/english/violance%20against%20women%20day.pdf (accessed May 26, 2014). The United Nations confirmed at least 100,000 total dead as of June 2013, its last official count before determining that it could no longer reliably calculate death tolls due to lack of access to sites and inability to verify source material used in data analysis. See John Heilprin, “UN Decides to Stop Updating Syria Death Toll,” AP, January 7, 2014, http://bigstory.ap.org/article/un-decides-stop-updating-syria-death-toll (accessed May 25, 2014).

[9] United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) Office of the Director, Middle East and North Africa Bureau, “Inter-Agency Regional Response for Syrian Refugees,” http://data.unhcr.org/syrianrefugees/regional.php (accessed June 13, 2014).

[10] Ibid.

[11] United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, “Patterns of Displacement Continue to be Massive in Syria,” September 27, 2013, http://www.ohchr.org/FR/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=13791&LangID=E; Internal Displacement Monitoring Center, “Syria: Internal Displacement in Brief,” December 31, 2013, http://www.internal-displacement.org/middle-east-and-north-africa/syria/summary (accessed June 11, 2014).

[12] United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, “Syrian Arab Republic: Humanitarian Dashboard,” May 26, 2014, http://syria.unocha.org/sites/default/files/syria_humanitarian_dashboard_jan_to_march_2014_26052014.pdf (accessed June 11, 2014).

[13] Human Rights Watch documented arbitrary detention, abuse, and torture of female activists in June 2013. See “Syria: Detention and Abuse of Female Activists,” Human Rights Watch news release, June 24, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/06/24/syria-detention-and-abuse-female-activists. Human Rights Watch has also previously documented arbitrary detention, abuse, and torture in detention facilities by government and pro-government forces and non-state armed groups. See Human Rights Watch, Syria– “By All Means Necessary!” Individual and Command Responsibility for Crimes Against Humanity in Syria, December 2011, http://www.hrw.org/reports/2011/12/15/all-means-necessary-0; Human Rights Watch, Syria–Torture Archipelago:Arbitrary Arrests, Torture, and Enforced Disappearances in Syria’s Underground Prisons since March 2011, July 2012, http://www.hrw.org/reports/2012/07/03/torture-archipelago-0; “Syria: Free All Arbitrarily Held Detainees, Hostages,” Human Rights Watch news release, March 15, 2014, http://www.hrw.org/news/2014/03/14/syria-free-all-arbitrarily-held-detainees-hostages.