“That Land Is My Family’s Wealth”

Addressing Land Dispossession after Côte d’Ivoire’s Post-Election Conflict

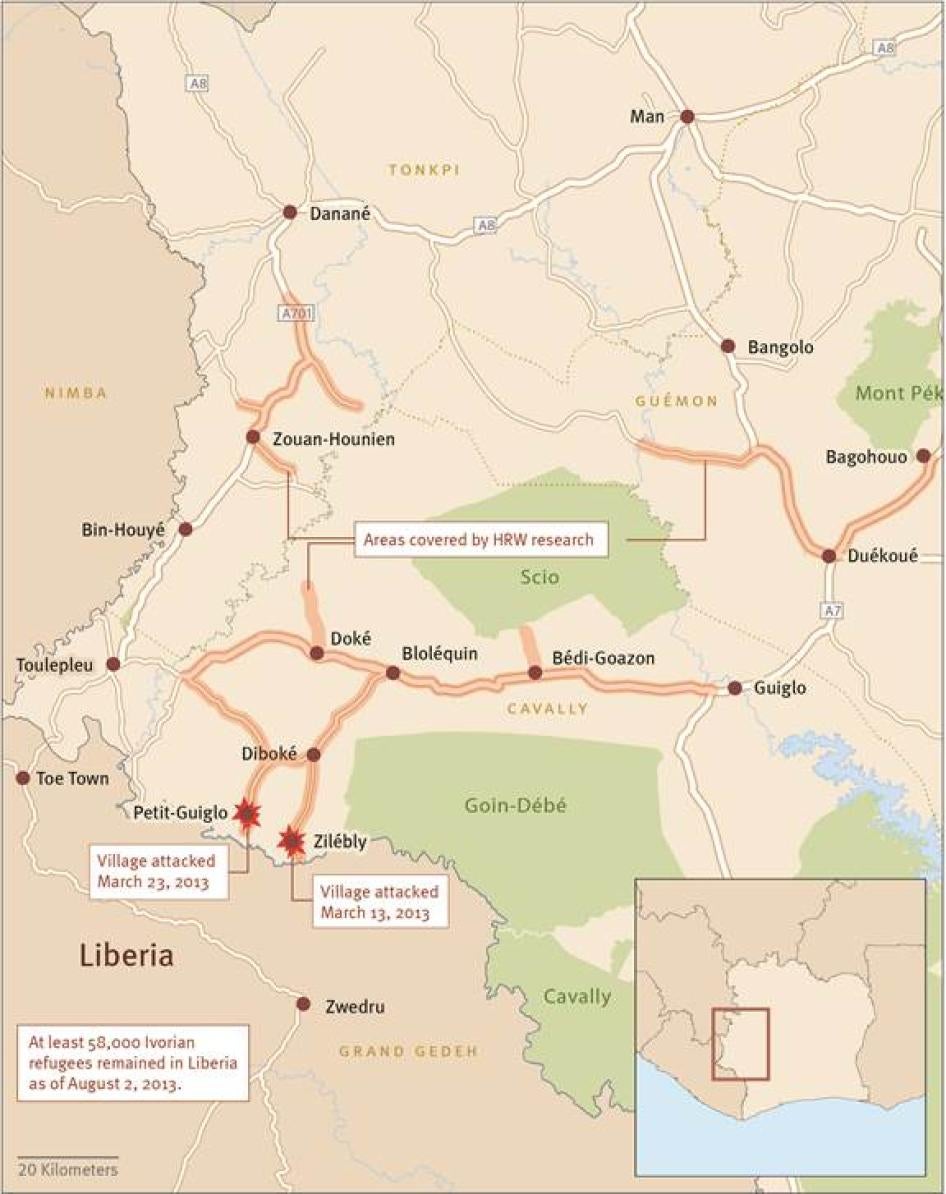

Maps

Côte d’Ivoire. © 2013 John Emerson / Human Rights Watch

Western Côte d’Ivoire. © 2013 John Emerson / Human Rights Watch

Summary

What’s happening angers us a lot, as the land is our inheritance. If the authorities don’t act quickly, things will get dangerous. For right now, we’re avoiding making war against the [illegal sellers and buyers]. But if we lose our inheritance, what are we going to eat, how will we stay in the village? Things could quickly fall apart…. If we continue to see the illegal occupation of land in our region … it could become another war.

—Alleged victim of land dispossession while displaced by conflict, June 2013

Land and ethnocentric politics have proven an explosive cocktail over the last 15 years in Côte d’Ivoire, particularly in the country’s volatile west. As the economy recessed and productive land grew scarce as a result of rising populations, Ivorian politicians exploited the resulting tensions between ethnic groups “native” to the west and “non-native” migrants who had come from neighboring countries and other regions of Côte d’Ivoire to work the region’s cocoa and coffee fields. When armed conflicts erupted from 2002-2003 and again from 2010-2011, deep inter-communal tensions linked to land were one factor in why western Côte d’Ivoire played host to many of the worst atrocities. The government of President Alassane Ouattara has said that resolving land conflict is a major priority. The actions it takes could determine whether western Côte d’Ivoire moves toward reconciliation or is stuck in a cycle of violence and instability.

By the end of the 2010-2011 conflict, around 200,000 people had fled to neighboring Liberia; hundreds of thousands more were displaced internally. While displacement occurred throughout the country, western Côte d’Ivoire experienced the greatest population movements. The Guéré ethnic group native to much of the region fled en masse from their villages as pro-Ouattara forces advanced toward Abidjan, where they would arrest former President Gbagbo on April 11, 2011, five months after he refused to accept electoral defeat to Ouattara. Guérés have tended to be some of the strongest political supporters of Gbagbo, and western-based pro-Gbagbo militia groups that committed egregious crimes against perceived Ouattara supporters during the post-election crisis included many Guérés. Both Guéré militiamen and civilians fled in fear of reprisals—fears that were often substantiated. Some Guérés were displaced for several months during and after the crisis. Others remained displaced for more than a year, with some 58,000 registered refugees still in Liberia as of August 2013. After returning home from displacement, many allege that their land has been overrun by non-native populations, particularly immigrants from Burkina Faso.

One story is commonly told by Guéré refugees in Liberia and pro-Gbagbo militants in Abidjan. They say that “non-natives”—meaning West African immigrants and Ivorians from ethnic groups native to other regions of Côte d’Ivoire—seized vast amounts of land that belongs to Guéré “natives” displaced by the crisis. They say that non-natives—implicating Burkinabé migrants, above all—are armed and ready to commit violence to protect their occupation of this land, and that these groups are supported by the Ivorian military. Another story is commonly told by the non-native populations in western Côte d’Ivoire, including Burkinabés. They say that the Guérés are lazy and dishonest and have repeatedly tried to seize back land that non-natives acquired legitimately. They say the Guérés have spent years terrorizing non-natives, particularly West African immigrants, trying to chase them away from the land.

As with many stories in a country that remains deeply divided on political and ethnic lines, the reality exists far from either extreme, though both sides present elements of the truth. Hundreds of Guérés have returned from being displaced to find someone occupying a parcel of land the Guéré landowner never sold or ceded. Many of those still in Liberia will face the same fate upon returning. Yet in the vast majority of cases documented by Human Rights Watch, land dispossession resulted from illegal sales of Guéré land by other Guérés, not a hostile takeover by armed Burkinabés. When Guérés were displaced during the conflict, Guérés from neighboring villages or even the same family pretended they were the real owners and sold the land, most often to Burkinabé migrants.

Although this reality is far less sinister than the oft-recited depiction of widespread, violent takeover of natives’ land, it is generally no less problematic for—and no less a violation of the rights of—the true landowners. The United Nations Principles on Housing and Property Restitution for Refugees and Displaced Persons, better known as the Pinheiro Principles, focus on the rights of returning refugees and displaced persons. The Pinheiro Principles state that “[a]ll refugees and displaced persons have the right to have restored to them any housing, land and/or property of which they were arbitrarily or unlawfully deprived.” The African Union Convention for the Protection and Assistance of Internally Displaced Persons in Africa (“Kampala Convention”) and the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights likewise protect property rights—including land that was owned according to customary rights. These rights have been violated in cases of illegal sales.

To investigate land conflict related to the post-election crisis, Human Rights Watch undertook a week-long mission to Liberia in December 2012 to speak with Ivorian refugees; and two three-week missions to Côte d’Ivoire, in February and June 2013. Human Rights Watch visited 49 towns and villages in Côte d’Ivoire’s western administrative regions of Guémon, Cavally, and Tonkpi and interviewed 168 people involved in land conflicts related to the post-election crisis—seeking out evidence from the various ethnic and immigrant populations involved in land disputes. Human Rights Watch confirmed many of its observations in dozens of additional interviews with people working closely on land issues in the West, including customary authorities and local government officials involved in resolving land disputes; and representatives of humanitarian organizations and the United Nations peacekeeping mission in Côte d’Ivoire.

In the 1960s and 1970s, President Houphouët-Boigny favored policies that promoted large-scale migration from neighboring countries and northern and central Côte d’Ivoire to the country’s lush western forest regions—where cocoa and coffee production helped create what became known as the “Ivorian miracle” of strong economic growth and political stability. An economic downturn in the 1980s and 1990s, combined with quickly diminishing cultivable land, led to a change in politics that focused on Ivorian nationality, culminating in a 1998 land law that said only Ivorian citizens could own rural land. Encouraged by certain politicians, some Guérés in western Côte d’Ivoire used this as a license to try to seize plantations that they had sold or ceded to West African immigrants; immigrants, for their part, were outraged that transactions they believed were outright land sales—sometimes reasonably, sometimes not—were now characterized as long-term leases or rental agreements. Rising land tensions in subsequent years played a role in the political and military violence that would follow, culminating in the post-election crisis.

The massive displacement in western Côte d’Ivoire caused by the post-election crisis ushered in chaos around land rights and acquisition. Some Guérés who returned while a true landowner remained displaced sold land fraudulently that they had no claim to, often including enormous amounts of virgin forest, particularly around Bloléquin. While some Burkinabé buyers purchased in good faith, others were complicit—clandestinely buying large parcels of land from young Guérés whose ownership claim would be questioned by any reasonable person, and doing so without involving local customary leaders who by practice normally witness such sales. Both the fraudulent seller and the bad-faith buyer benefited greatly, with no fear of sanctions, while the true landowner—displaced within Côte d’Ivoire or to Liberia—returned home to find his land sold and occupied.

In addition to illegal land sales, Human Rights Watch documented some cases of more hostile land takeovers. Some non-natives no longer honor longstanding rent agreements, under which they previously paid a part of the harvest to the Guéré landowner. Other non-natives used the landowners’ absence to illegally enlarge their holdings; for example, a two-hectare purchase was at times extended to three hectares after the owner fled internally or to Liberia. In four further cases, all located in a particular area south of Bloléquin, Human Rights Watch documented occupation by force, in which dozens of Burkinabés have moved onto a Guéré’s land, saying it was their “reward” for having fought with pro-Ouattara forces during the crisis. Finally, non-natives have destroyed or occupied sacred Guéré land in several villages, escalating tensions there and potentially violating their rights to free practice of religion.

The illegal sale or seizure of land has serious consequences on people’s livelihoods, making the failure of the Ivorian government to ensure timely land restitution a potential violation of the rights to food and livelihood. Many Guérés fled the crisis with only the barest of possessions and returned to find that their houses had been pillaged and burned. But land dispossession is seen as a far more existential threat, likely to provoke inter-communal violence, as it imperils livelihoods both present and future. Human Rights Watch documented dozens of cases in which occupants have seized or destroyed crops that owners had formerly planted. Virgin forest that landowners planned to leave to future generations as inheritance is now being cut down and planted on. Without the ability to grow cash crops or foodstuffs, those who lost their land while displaced face a “poverty that we don’t even know how to describe,” in the words of one Guéré. Land dispossession, and the economic consequences it entails, is one of the main reasons some refugees in Liberia said they do not feel able to return home.

Land dispossession linked to the post-election crisis is already fueling small-scale violence. Two cross-border attacks in March 2013 appear directly related to land conflicts in the area hit hardest by illegal occupations. Attackers killed at least nine civilians in two border villages south of Bloléquin on March 13 and 23 and destroyed dozens of homes. Land sale documents seen by Human Rights Watch indicate that attackers appear to have targeted some victims for their perceived role in allegedly illegal land transactions. There have also been several inter-communal clashes in 2013—with Guérés from two villages fighting each other over allegations of fraudulent land sales. Fiery rhetoric is recurrent in many villages, and tensions threaten to erupt into additional clashes.

The dispossession of Guéré land in the aftermath of the post-election crisis must be seen in the context of what happened in western Côte d’Ivoire after the 2002-2003 armed conflict. Then, the non-native population was forced to flee as they were targeted by pro-Gbagbo forces for serious crimes; many were unable to return for four years. Some Guéré landowners imposed extortionate conditions on the non-natives’ return, taking back parts of previously ceded land or demanding money to recover a person’s own property. Other Guérés illegally sold or re-sold land during non-natives’ displacement. Burkinabé leaders in western Côte d’Ivoire described some of the recent seizures as “recovering” this land. That likely has occurred, though illegal sales and seizures have undoubtedly gone well beyond re-acquisitions. The tit-for-tat nature of land dispossession in western Côte d’Ivoire is one of the many forms of vigilante justice practiced there over the last decade. It will likely continue until Ivorian authorities are able to establish confidence in the rule of law as the way to resolve disputes, including over land.

Under the Pinheiro Principles, states “should establish and support” through “adequate financial, human and other resources … equitable, timely, independent, transparent and non-discriminatory … mechanisms to assess and enforce … land and property restitution claims.” To date, the Ivorian government has largely failed to meet that responsibility, although the opening of a new tribunal in Guiglo in June 2013 should increase the access to the justice system for people living in far western Côte d’Ivoire.

Customary and administrative mechanisms dealing with land conflicts are often overwhelmed with claims in western Côte d’Ivoire, particularly related to the post-election crisis. In western Côte d’Ivoire, village chiefs and sub-prefects, the main customary and administrative officials responsible for resolving land conflicts, collectively have thousands of cases before them. Yet they have received remarkably little financial support from the national government—often either crippling their ability to investigate and resolve disputes, or obliging them to charge exorbitant sums to accept cases from people who have lost everything and are unable to access their land.

In addition, successive Ivorian governments have promised to demarcate boundaries between villages. No Ivorian government yet has. The lack of village boundaries has helped create the free-for-all in which people can easily cross into another village and sell land they have no claim to. Officials in the Ouattara government have promised that demarcating village boundaries is a priority, but little concrete action has been taken. Donor help could be crucial both financially and technically.

Finally, there is total impunity for those involved in fraudulent land sales. Customary and administrative officials could not point to a single case in which sanctions had been imposed—even when an illegal land seller’s acts amounted to theft and fraud. Indeed, many of the customary and administrative officials interviewed by Human Rights Watch said they actively avoided implicating the gendarmerie and judicial authorities, saying it would harm reconciliation. Residents around western Côte d’Ivoire repeatedly expressed otherwise, saying that penal sanctions—whether fines or imprisonment—were crucial to stop fraudulent sales, the root of so many land conflicts.

In August 2013, the Ivorian government undertook modest reforms to the country’s nationality law and the 1998 law on rural land tenure. However, the land law still has provisions that the government needs to clarify in a way that conforms to international human rights law and the rights of returning refugees. Moreover, national land reform will not be a panacea for the conflicts that plague western Côte d’Ivoire. There, claims for restitution related to land dispossession during displacement must be addressed individually—and urgently. Every day, people are permanently changing land that they acquired illegally. Trees from previously virgin forests are being cut down, cocoa plants and rubber trees planted instead. Each day that happens, the anger and hatred mounts among those who have been dispossessed.

Land has been one of the root causes of Côte d’Ivoire’s decade lost to violence and grave human rights abuses. The Ivorian government’s efforts to ensure land restitution in western Côte d’Ivoire will help determine whether land will remain a potential spark for conflict or become a source of local development that alleviates inter-communal tensions.

Recommendations

To the President, Prime Minister, and National Assembly

- Consult with local populations around Côte d’Ivoire, through a formal process, before further modifying laws or drafting decrees related to the reform of land tenure. Ensure that all political and ethnic groups, women, and youth are included in consultations.

- Recognize that the August 2013 reforms to laws on nationality and rural land tenure will not resolve the thousands of land conflicts caused by the post-election crisis, and commit publicly to ensure restitution for refugees and displaced persons whose land was illegally sold or seized during their displacement.

- Prioritize restitution in the form of people returning to their own land, in accordance with the Pinheiro Principles.

- Support with adequate financial, human, and other resources existing customary, administrative, and judicial mechanisms involved in resolving claims of land dispossession linked to the crisis, to better facilitate just and timely restitution.

- Ensure that a legal mechanism is in place to

effectively resolve land ownership claims and disputes and to assist landowners

in registering their property with the cadastre and in obtaining the

demarcation of their property lines. This may involve modifying or better

supporting the current administrative mechanisms, particularly the

sub-prefectural land committees, or may require creating a new mechanism.

- Ensure that any legal mechanism for resolving land ownership claims and disputes is accessible to local populations.

- Consider examining the experience of other countries, including Bosnia, that have had success in determining property ownership in the aftermath of mass displacement during an armed conflict.

- Ensure by law or decree that people can appeal to the court system decisions made by a sub-prefectural land committee or other administrative body, particularly in regards to disputes over land ownership.

- Issue a decree or pass a law clarifying that displacement as a result of inter-communal violence or armed conflict does not negate a person’s ability to establish “continuous and peaceful existence of customary rights” to their land, as required by the 1998 law on rural land tenure.

- Clarify by decree or law whether and how informal papers (petits papiers, in French) related to land transactions will be used to determine land ownership or rental agreements.

- Ensure, in accordance with the Ivorian constitution and international human rights law, that women and men have equal rights in terms of access to land and that there is no discrimination against women, in law or in practice, in regards to the ability to formalize land ownership rights under the 1998 rural land law.

To the Ministers of Interior, Justice, and Agriculture

- Instruct the sub-prefects, police, judicial police, and prosecutors to work together to undertake investigations and prosecutions when land sales appear to have been fraudulent, namely when people sell land to which they have no reasonable claim to ownership. Penalties should ensure, at a minimum, that the bad-faith seller does not retain a profit from his fraud.

- Ensure that customary and administrative mechanisms involved in resolving land disputes in western Côte d’Ivoire act in accordance with international human rights and humanitarian law and standards.

- Support financially and through adequate

staffing the village and sub-prefectural committees involved in resolving land

conflicts related to displacement, with a view to eliminate or at least greatly

reduce the fees some customary and administrative authorities now charge people

to file land complaints, call witnesses, and perform field investigations.

- Ensure, at a minimum, that the sub-prefectural committees waive fees in cases where a party can demonstrate financial hardship.

- Investigate claims related to the destruction or occupation of sacred areas and remove people illegally occupying sacred land. Ensure that Ivorian law grants full protection to such land.

- Create a mechanism to allow people displaced within Côte d’Ivoire to travel to their home village to see if their land is occupied illegally and to bring a complaint if necessary.

- Ensure that village land committees include representatives from all communities, including immigrant populations, non-native Ivorian ethnic groups, women, and youth.

To the Minister of Agriculture

- Undertake promptly the demarcation of village boundaries. Prioritize areas where land and inter-communal conflict are closely linked, including in western Côte d’Ivoire.

- Consider reducing the fees associated with obtaining a land certificate (certificat foncier) and registering land ownership in the cadastre, to better ensure that these processes are accessible to everyone.

- Ensure that, throughout the country, local offices of the agriculture ministry are adequately staffed and supported to provide guidance, assistance, and all necessary paperwork related to the various steps of the process to formalize customary rights to land.

- Ensure through assistance or alternative means of completing paperwork that people who are illiterate are not discriminated against in formalizing their customary claims to land.

- Take steps to increase the pool of qualified experts who can determine and demarcate rural land boundaries, in an effort to accelerate the process and to reduce costs for landowners trying to register their land with the cadastre. Consider whether trained experts from other professional fields could assist in the demarcation process and, if appropriate, modify relevant laws and decrees that have granted the Order of Expert Surveyors a monopoly on performing these tasks.

To the Minister of Defense and the Authority for Disarmament, Demobilization, and Reinsertion (ADDR)

- Accelerate efforts to disarm former combatants who fought on both sides of the politico-military crisis, as the presence of armed men has emboldened fraudulent activity and intimidated some people trying to return to their land or to file claims related to land dispossession.

To the National Assembly

- Ratify the African Union Convention for the Protection and Assistance of Internally Displaced Persons in Africa and harmonize Ivorian law with its provisions.

- Create a special technical committee, in

accordance with the National Assembly bylaws, responsible for examining the

root causes of and necessary legislative actions to address land conflict,

including land conflict linked to displacement.

- Conduct public hearings on the links between land conflict, displacement, and violence and call to testify, among others, experts on rural land tenure, representatives from various ethnic and immigrant populations, customary leaders, local government officials, representatives from civil society, and surveyors.

To Donors, including the European Union, France, and the United States

- Provide financial and technical assistance to customary and administrative mechanisms in western Côte d’Ivoire involved in resolving claims of land dispossession associated with the post-election crisis.

- Fund capacity building for customary and administrative officials involved in resolving land conflicts in western Côte d’Ivoire. Such capacity building should help promote the mechanisms’ ability to act in accordance with international human rights, refugee, and humanitarian law standards.

- Provide financial and technical assistance to the Ivorian government in its efforts to demarcate village boundaries. Assist the Agriculture Ministry in increasing its pool of surveyors, through trainings and by embedding experts.

Methodology

This report is based on three research missions to Côte d’Ivoire and Liberia. In December 2012, Human Rights Watch spent a week in Grand Gedeh, Liberia, where tens of thousands of Ivorian refugees remain after fleeing western Côte d’Ivoire during the 2010-2011 conflict. Human Rights Watch also undertook two missions to Côte d’Ivoire of around three weeks each, in February and June 2013, spending a total of four weeks in western Côte d’Ivoire and two weeks in Abidjan.

While land disputes exist throughout Côte d’Ivoire, this report focuses on land conflict and dispossession related to the displacement caused by the 2010-2011 post-election crisis. Western Côte d’Ivoire experienced the heaviest displacement, both in terms of people displaced within Côte d’Ivoire and people who fled to neighboring Liberia as refugees. Land conflict has also long been linked to politico-military violence and grave human rights abuses in that region.

During its field work, Human Rights Watch visited 49 towns and villages in the western administrative regions of Guémon, Cavally, and Tonkpi. In particular, Human Rights Watch conducted interviews in following towns and villages:

- In Guémon: Duékoué, Bagohouo, Yrouzon, Guinglo-Zia, Blody, Toa-Zéo, Kahin-Zarabaon, Séhoun-Guiglo, Fengolo, and Diahouin;

- In Cavally: Guiglo, Domobly, Guinkin, Kaadé, Ziglo, Bédi-Goazon, Douedy-Guézon, Ladjikro (campement)[1], Béoué, Guibobly, Guéya, Diouya-Dokin, Bloléquin, Goya, Pohan-Badouebly, Doké, Bloc (campement), Doké II (also known as Laïpleu), Zomplou, Diéya, Diahibly, Glacon-Bloc, Médibly, Diboké, Zilébly, Oulaïtaïbly, Tinhou, Dedjéan, Petit-Guiglo, Koadé-Guézon (KDZ), and Denan;

- In Tonkpi: Danané, Zouan-Hounien, Ouyatouo, Gbontegleu, Batéapleu, Zéalé, Téapleu, and Bounta.

Human Rights Watch interviewed more than 230 people in total, including 117 alleged victims of displacement-related land dispossession. These victims come from the Guéré ethnic group, which tends to support former President Gbagbo and is “native” (the autochtones, in French) to much of Guémon and Cavally regions. In order to ensure the representation of all viewpoints, Human Rights Watch also interviewed individuals from other ethnic and immigrant populations involved in land conflicts in western Côte d’Ivoire, including 32 Burkinabés and Malians, the predominant immigrant populations (allogènes) in western Côte d’Ivoire; 26 members of Ivorian populations not native to western Côte d’Ivoire (allochtones), including Baoulés, Malinkés, Senoufos, and Lobis; and 19 Yacoubas, the natives in most of Tonkpi region. In addition, Human Rights Watch interviewed customary and traditional leaders from the various ethnic and immigrant groups; local government officials involved in resolving land disputes; leaders from Ivorian civil society; representatives from humanitarian organizations; representatives from the United Nations peacekeeping mission in Côte d’Ivoire; diplomats in Abidjan and Europe; and journalists.

Human Rights Watch generally interviewed people involved in land disputes in their home village. Most interviews were conducted individually, with a few focus groups at the early stage of research to help identify particular regions of tension and issues for deeper exploration. Complete privacy is often difficult in small villages, where people quickly crowd around, eager to see why an outsider has arrived. Human Rights Watch generally explained its presence to everyone interested, and then tried to interview in privacy individuals who had personal stories of land conflict related to the post-election crisis. On occasion, people preferred that others—usually family members or community leaders—were also present at the interview. Victims were identified through community leaders, local activists, and other victims. Human Rights Watch did not offer interviewees any incentive for speaking, and they were able to end the interview at any time.

Human Rights Watch has withheld names and identifying information of people involved in land disputes in order to protect their privacy and security. Most spoke on the condition of anonymity, out of fear of reprisal.

Throughout the research, Human Rights Watch shared its findings with the Ivorian government, including in meetings with Interior Minister Hamed Bakayoko; the Minister of Justice, Human Rights, and Public Liberties, Gnénéma Coulibaly; Agriculture Minister Mamadou Coulibaly; President Ouattara’s advisor on human rights and humanitarian affairs, Mamadou Diané; and the Prime Minister’s special advisor on rule of law, Vincent Sedalo. Human Rights Watch appreciates the government’s consistent willingness to meet on human rights issues.

Human Rights Watch also wrote to Prime Minister Daniel Kablan Duncan on August 21, detailing the report’s main findings and asking for an official government response (see Annex I). On September 13, Justice Minister Gnénéma Coulibaly responded on behalf of the government. Human Rights Watch has incorporated many of the government’s answers into the report body and has included the entire response in Annex II.

I. Background

[Land] tensions, exploited and exaggerated into a form of xenophobic hatred by politicians at the highest level, hold the key both to the country’s destruction and, if properly addressed, its possible reconstruction.

—Global IDP Project, November 2005[2]

Land, politics, and violence have been closely linked in Côte d’Ivoire for the last two decades, culminating in a rebellion launched in 2002 and an armed conflict in 2010-2011 following contested presidential elections. Many of the worst crimes during both armed conflicts occurred in western Côte d’Ivoire, where tension and land conflict between “native” and “non-native” populations are particularly acute. Hundreds of thousands of people were displaced during the conflicts, and many returned to find that their land had been illegally seized by someone from another community.

President Alassane Ouattara has said that resolving the problems around land tenure is one of his highest priorities. To put an end to the land conflict in western Côte d’Ivoire that has helped fuel massive human rights abuses, the Ouattara government will have to ensure the restitution of land seized from people displaced by conflict and address the problems that have encouraged fraudulent land sales and confusion over land ownership.

Law and Politics of Land in Côte d’Ivoire

From the country’s independence in 1960 to the early 1980s, Côte d’Ivoire prospered economically, becoming a world leader in cocoa and coffee production. Félix Houphouët-Boigny, president from 1960 to his death in 1993, oversaw an open-door immigration policy, which, coupled with the rapid growth of the Ivorian economy, attracted migrant workers from neighboring countries, who grew to about one-quarter of the population.[3] The country’s western part, with land ideal for cocoa and coffee production, was a popular destination for both immigrants and migrant workers from northern and central Côte d’Ivoire—who by 1998 together outnumbered the native populations in the region.[4]

In the 1980s, cocoa and coffee prices plummeted on international markets which, along with other factors, helped lead to a sharp economic recession. An increasing number of educated youth were unable to find employment in Abidjan and returned to their villages, including in the country’s west.[5] They found that during their absence their parents had rented or ceded much of the land to migrants, creating inter-generational conflicts among the native population and inter-communal conflicts between the natives and migrants.[6]

In the political vacuum left by Houphouët-Boigny’s death in 1993, politicians increasingly looked to build support through ethnic blocs. Several politicians employed the rhetoric of “Ivoirité,” or “Ivorianness”—an ultranationalist discourse focusing on Ivorian identity that marginalized immigrants and northern Ivorians, groups that tended to support then-Prime Minister Ouattara.[7] While the discourse was predominantly about politics and nationality—used to bar Ouattara from contesting the 1995 and 2000 elections[8]—it also related to land issues, challenging non-Ivorians’ ability to have significant property rights.[9]

On December 23, 1998, the National Assembly unanimously passed Law No. 98-750, the “Law on Rural Land Tenure,” which sought to transition land tenure from customary land claims to private, individual ownership backed by land titles filed with the state cadastral registry.[10] A comprehensive review of the law is beyond this report’s scope and has been well covered by others.[11] However, several components are crucial to understand subsequent conflict over land.

Prior to the 1998 land law, there was great confusion about rural land ownership rights. From 1935 to 1998, land transactions based on custom had no legal authority, as the law required people to register their land through land titles and to involve a notary in land transactions.[12] Yet this formal system ignored a reality in which “the management of 98 percent of rural land is customary, with only one or two per cent of land held under title deed.”[13] The various laws and decrees leading up to the 1998 land law were therefore never implemented or enforced, including in western Côte d’Ivoire.

Custom in Côte d’Ivoire makes “a clear distinction between the ownership of the soil—which belongs to the community (family, lineage or village) and cannot be sold under any circumstances—and the right of use of the soil, which may be transferred or sold.”[14] Ownership of the soil under this custom generally belongs to those who first arrived to the area; in western Côte d’Ivoire, this often means the families that founded a village.[15] These families almost never obtained land titles, as village and individual family boundaries remained governed by custom. Under custom, these guardians of the land, or tuteurs, could not sell “ownership of the soil,” but they could cede or sell rights of use in the land.[16] When virgin forest was plentiful in western Côte d’Ivoire in the 1960s and 1970s, migrants often had only to provide an offering of a drink or small gifts in return for receiving one or more hectares of land on which to plant cash crops and foodstuffs.[17] Over time, as land became more scarce, “land transfers started to involve money, and sometimes large amounts,” creating “confus[ion] as to whether the right of use was being sold, or the ownership of the land. This confusion was knowingly upheld, both by the state—notably by way of ex-president Houphouët-Boigny’s famous slogan ‘The land belongs to those who put it to good use’ … and by certain local owners who used this notion to demand larger amounts of money.”[18]

On the eve of the 1998 land reform, there thus existed two deep tensions:

- Between a reality dominated by customary land management, and a legal framework that gave customary rights no value; and

- Between a reality in which land had been sold or ceded on a large scale, often in ways that suggested selling ownership of the soil, and a custom that forbade the sale of anything more than a right of use.

On the first issue, the 1998 land law broke ground in recognizing customary rights as a basis for claiming land ownership during a transitional period.[19] The law gave everyone 10 years to transform customary rights into a system of private ownership. People asserting land rights were to initiate a procedure after which, if local authorities confirmed their customary-based claims, they would obtain a state-issued land certificate (certificat foncier). People then had three additional years to register their parcel of land in the state’s land registry, or cadastre.[20] In part due to the subsequent decade-long politico-military crisis and in part because of poor dissemination of the law, the government issued extremely few land certificates by the end of the 10 year deadline.[21] On August 23, 2013, the National Assembly passed a law giving people an additional 10 years to formalize their customary rights.[22] At the end of the period, all legal land transactions will ostensibly involve the transfer of land title registered in the cadastre.

As to the second tension noted above, the 1998 land law incorporated the ideals of Ivoirité, stating that, for rural land, “only the government, public authorities, and Ivorian citizens are permitted to be landowners.”[23] Anyone without Ivorian citizenship could not own land; their rights appear restricted to rental agreements or long-term leases, which can run for up to 99 years and be passed to heirs.[24] Thus, many non-Ivorians who paid significant sums of money to acquire land prior to the 1998 law appear unable to transform their purchases into a land title. According to a 2009 report, “At best, [the non-Ivorian] can expect to obtain a long-term lease with favorable conditions, but which still imposes the payment of rent for land that he considers his own.”[25] Almost every pre-1998 transaction occurred outside the written law—based on custom, not a transfer of land title—so it is difficult to say that it annulled “legal” sales. But the 1998 law certainly changed the type of property rights that some non-Ivorians believed, often reasonably, that they had acquired when purchasing and investing for years in parcels of land.

Under the 1972 nationality code, citizenship comes primarily from jus sanguinis (right of blood) rather than jus soli (right of the soil). A child born in Côte d’Ivoire is only conferred Ivorian nationality if born to at least one Ivorian parent.[26] Thus, as many as half the foreign migrants in Côte d’Ivoire were born and raised in the country, yet are not citizens.[27]

The 1998 law on rural land tenure further raised tensions between immigrants and natives in western Côte d’Ivoire, leading to several deadly clashes in 1999 in the center-west and south-west parts of the country.[28] Many immigrants in western Côte d’Ivoire believed that their pre-1998 transactions had been for land ownership, yet the law appeared to bar such a claim. Natives, particularly youth, saw the law as a license to take back land their elders had sold or ceded to immigrants in prior decades. Politicians, particularly Gbagbo’s political party, promoted this belief, as described by a scholar on Ivorian land issues:

During the 1990 and 1995 elections, politicians’ speeches encouraged indigenous people from the forest regions to believe that the rise to power of the opposition leader Gbagbo would lead to the expropriation of land from non-native and non-indigenous peoples and its subsequent reallocation. By taking up the ‘land for indigenous people’ slogan incorporated in the Land Act on the eve of the 2000 presidential, legislative and municipal elections, politicians aimed to attract voters while reinforcing the principle of reclaiming land….[29]

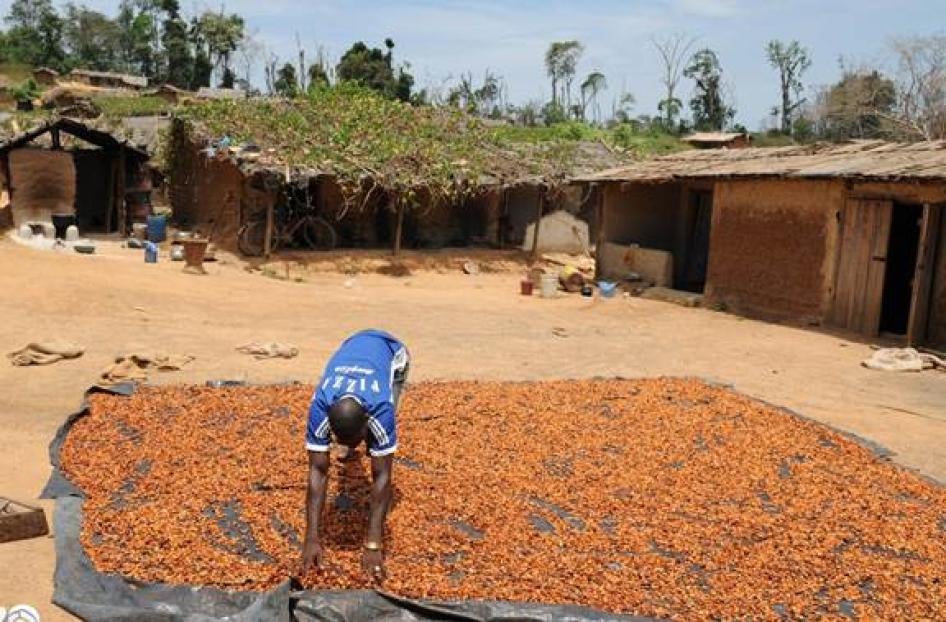

A cocoa farmer spreads cocoa beans that will dry under the sun in the village of Cantondougou, 360 kilometers west of Abidjan, April 23, 2009. © 2009 AFP Photo/Kambou Sia

Conflict over land—while certainly not the only, or even the most important factor—would play a prominent role in Côte d’Ivoire’s plunge toward a decade of violence and grave human rights abuses. This was particularly true in the country’s west.

Displacement of Migrant Populations by the 2002-2003 Armed Conflict

On September 19, 2002, rebels from the Patriotic Movement of Côte d’Ivoire (Mouvement Patriotique de Côte d’Ivoire, MPCI) attacked strategic targets in Abidjan along with the northern towns of Bouaké and Korhogo. Although it did not succeed in taking Abidjan, the MPCI, soon joined by two western-based rebel factions, quickly controlled the northern half of Côte d’Ivoire. The three rebel groups formed a political-military alliance called the Forces Nouvelles, which sought to end political exclusion and discrimination against northern Ivorians and to remove the president, Laurent Gbagbo, who they perceived as illegitimate due to flaws in the 2000 elections. [30] Fighting was particularly intense in the country’s west, where both sides recruited Liberian mercenaries and targeted mostly civilians. Human Rights Watch documented grave crimes committed by both sides, including summary executions, massacres, and targeted sexual violence. [31]

Facing targeted abuses by pro-Gbagbo forces for their perceived support for the rebellion, immigrants and Ivorians from northern and central ethnic groups fled en masse from the southern half of western Côte d’Ivoire. [32] Many had lived and worked on plantations there for decades, even generations. [33] The displacement of migrant populations was particularly acute along the Guiglo-Toulepleu axis, where there was a heavy concentration of pro-Gbagbo militia groups. Many immigrants and non-native Ivorians fled to the northern half of the country, controlled by the Forces Nouvelles, while around 7,000 went to a displaced persons camp in Guiglo. [34] Four years after the conflict, more than 5,000 displaced persons, the overwhelming majority Burkinabé and Malian immigrants, remained at the Guiglo camp [35] —unable to return to their homes and land because of threats from pro-Gbagbo forces and some members of population native to the region. [36]

During the forced displacement of immigrants and non-native Ivorians, some Guérés—the main population native to the region—retook land that they had previously sold or ceded to those who fled. [37] Non-natives began returning to villages in Guiglo department [38] in 2005. [39] In Bloléquin department, most non-natives could not start returning until 2007 or 2008. [40] Burkinabés from several villages in western Côte d’Ivoire told Human Rights Watch that, after reconciliation ceremonies involving native and non-native populations, they were able to regain without difficulty any land that Guérés had taken over. But in other villages, some Guérés, backed by the Gbagbo government, imposed extortionate conditions before permitting the return of displaced non-natives; these varied from village to village, or even tuteur to tuteur. In some villages, some Guérés demanded that immigrants and non-native Ivorians give back part of the parcel previously sold or ceded in order to be able to return to the village. Other Guérés demanded money from displaced non-natives before allowing them to return to the village or reacquire their land. Some Guérés even resold the person’s parcel while he was displaced. [41]

In Bloléquin department, where anti-immigrant hostility appeared particularly severe, the Ivorian government, humanitarian organizations, and the opposed communities came to an agreement at a February 2008 workshop aimed at permitting the remaining displaced persons to return to their land.[42] Known as the Bloléquin Accord, non-native leaders accepted that their communities would renegotiate rental agreements with the native landowners, regardless of their previous terms of individual agreements.[43]A Burkinabé leader in Bloléquin told Human Rights Watch: “People didn’t have any money [after being displaced for four years], so they had to accept any condition to get back to their land…. The [native population] took advantage [of our situation].”[44] While outside the zone of the Bloléquin Accord, a Malian community leader in Duékoué said similarly: “Between 2002 and 2010, we couldn’t say anything. We had to pay whatever they demanded.”[45]

Through the November 2010 presidential elections, immigrant populations in western Côte d’Ivoire continued to suffer regular abuses at the hands of pro-Gbagbo security forces and militia groups. [46] A Burkinabé leader in Bloléquin believed that the actions taken by native, typically pro-Gbagbo populations after the 2002-2003 armed conflict contributed to the severity of the post-election crisis in western Côte d’Ivoire:

Reconciliation was poorly done after the first crisis. It was not easy for Burkinabés [and other immigrant populations] to return to their homes and to their land…. If it had been better done, if the reconciliation had been genuine, the post-election crisis would not have hit here so hard. [47]

Post-Election Crisis

After five years of postponing presidential elections, Ivorians went to the polls on November 28, 2010 to vote in a run-off between incumbent President Laurent Gbagbo and former Prime Minister Alassane Ouattara. After the Independent Electoral Commission announced Ouattara the winner with 54.1 percent of the vote—a result certified by the UN Operation in Côte d’Ivoire (UNOCI) and endorsed by regional bodies and countries around the world—Gbagbo refused to step down. [48] Six months of violence followed, in which at least 3,000 civilians were killed and more than 150 women raped, often in attacks perpetrated along political, ethnic, and religious lines. [49]

By conflict’s end in May 2011, armed forces on both sides of the politico-military divide had committed war crimes and likely crimes against humanity, as documented by a national commission of inquiry created by President Ouattara, a UN-mandated international commission of inquiry, and human rights organizations. [50] The most serious crimes occurred in two areas: Abidjan, where the struggle for political and economic control centered; and western Côte d’Ivoire, beset by longstanding communal tensions and where pro-Ouattara forces launched their military offensive in March 2011 to take control of the country. [51]

The human rights division of UNOCI reported in May 2011 that it had documented 1,012 crisis-related killings in western Côte d’Ivoire, including at least 505 deaths in Duékoué alone.[52] Among those identifiable, UNOCI documented at least 341 Guéré victims, the native population that tends to support Gbagbo; and, on the typically pro-Ouattara side, 159 Burkinabé, 100 Malinké, 68 Malian, 30 Baoulés, 6 Guinean, and 5 Béninois victims, among others.[53] Several of the worst atrocities committed by forces on both sides occurred in western Côte d’Ivoire, including the March 25 massacre by pro-Gbagbo militia groups and mercenaries of at least 70 northern Ivorians and immigrants, including men, women, and children, who had taken refuge in the Bloléquin prefecture; and the March 29 massacre of several hundred mostly Guérés by pro-Ouattara forces in Duékoué.[54]

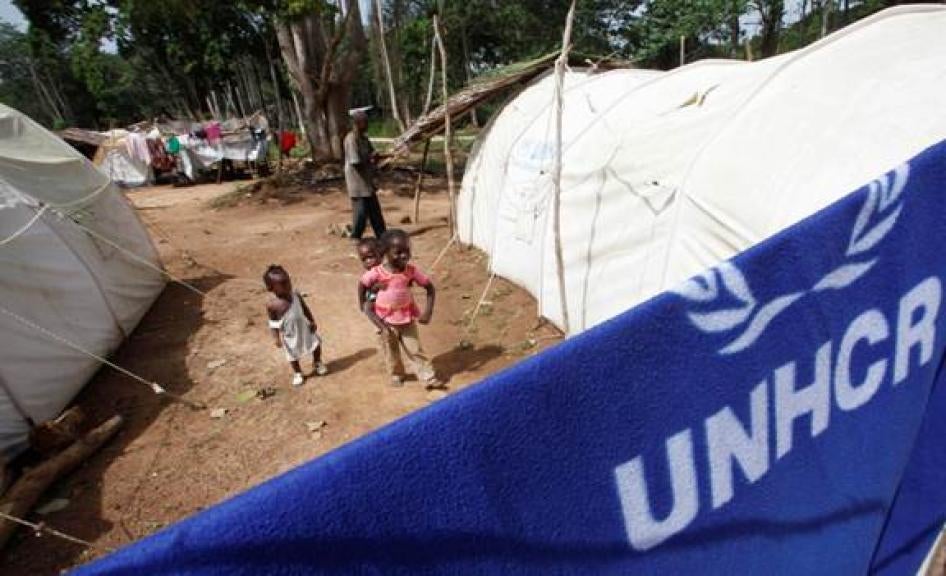

Faced with intense fighting and grave human rights violations by armed forces on both sides, around 200,000 people fled to Liberia during the crisis, [55] primarily from western Côte d’Ivoire. A majority of these refugees either supported or were from ethnic groups which largely supported Gbagbo during the 2010 election. [56] Hundreds of thousands more people were displaced internally within Côte d’Ivoire; the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) reported in June 2011 that the greatest concentration of internally displaced persons (IDPs) was in western Côte d’Ivoire. [57]

This report focuses on what happened to the land of people in western Côte d’Ivoire displaced by the post-election crisis. Many remained displaced for months after the conflict’s May 2011 end, with at least 58,000 registered refugees in Liberia as of August 2, 2013. [58] In interviews with Human Rights Watch, they expressed concern for their security and livelihoods should they return to Côte d’Ivoire. [59] These concerns have been amplified by the sporadic targeting of typically pro-Gbagbo populations for abuses even after the conflict, primarily by the country’s military, the Republican Forces of Côte d’Ivoire (FRCI), and allied fighters. [60] In a particularly egregious example, some FRCI soldiers and allied forces burned to the ground the Nahibly IDP camp in July 2012, which housed around 4,500 people still displaced after the crisis. [61] The International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) has reported verifying at least six summary executions by FRCI soldiers and the “disappearance of dozens of displaced persons.” [62] FIDH said that there may be up to 13 mass graves linked to the Nahibly attack, including a well in which six bodies were

A UN peacekeeper stands near the destroyed Nahibly displaced persons camp near Duékoué, July 22, 2012. On July 20, members of the Ivorian military and allied forces burned down the camp, which then housed around 4,500 people, and summarily executed or disappeared some people who fled. © 2012 AFP PHOTO/ SIA KAMBOU

found in October 2012. [63]

President Alassane Ouattara (center) looks at a stand of cocoa during the 2012 World Cocoa Conference in Abidjan. President Ouattara has said that resolving conflicts related to land tenure is a key priority for his government. © 2012 AFP Photo/Sia Kambou

Reform to Land Tenure and Nationality Laws in 2013

In May 2013, President Ouattara committed to reevaluate and reinforce the 1998 law on rural land tenure, rightly linking both land and nationality issues to Côte d’Ivoire’s decent into politico-military violence.[64] During a special legislative session, the National Assembly passed laws on both subjects on August 23. For rural land tenure, the National Assembly extended for another 10 years the period during which people can transform customary-based claims to land into private, state-backed land ownership.[65] On the issue of nationality, the new law re-opens[66] Ivorian citizenship to foreign-born residents who have lived in Côte d’Ivoire since before independence, as well as to their descendants; and to people born to foreign nationals in Côte d’Ivoire between December 1961 and January 1973, as well as to their descendants.[67] The law also allows these people to make their claim for Ivorian citizenship through a declaration, rather than the normal naturalization process.[68]

The political opposition and at least some civil society groups expressed frustration over the lack of consultation with relevant stakeholders before the National Assembly debated and passed the laws.[69] According to its letter response to Human Rights Watch, the Ivorian government does not currently have plans for additional reforms to the 1998 law on rural land tenure.[70] A potentially divisive question will be how citizenship conferred under the new nationality law impacts previous acquisitions of land, since only Ivorian nationals can own land under the 1998 law. That question is outside the scope of this report.

With this report, Human Rights Watch aims to capture the prevailing situation of land conflict in western Côte d’Ivoire and to offer recommendations for sustainable solutions to those conflicts, grounded in the equal protection of land and property rights. Western Côte d’Ivoire has experienced some of the country’s worst atrocities over the last decade and could prove host to more atrocities if land issues are not resolved. Reducing tensions in western Côte d’Ivoire will require significant work at the local level to address complaints related to illegal land seizures that occurred while people were displaced by the post-election crisis.

II. Land Dispossession after the Post-Election Conflict

After the crisis, the region has known complete disorder and anarchy in terms of land.

—Burkinabé community leader in western Côte d’Ivoire, June 2013[71]

In western Côte d’Ivoire, there are thousands of complaints by the native, mostly Guéré, population of alleged land dispossession linked to displacement caused by the 2010-2011 conflict. One sub-prefect, a local government official who oversees an administrative area comprising a number of villages, told Human Rights Watch that he alone had received more than 800 complaints related to land since the crisis.[72] Another sub-prefect said he deals with between four to eight cases a day, four days a week.[73] In the area examined by Human Rights Watch, there are seven different sub-prefectures dealing with at least scores, and often hundreds, of these cases.[74] And cases that reach the sub-prefect are generally those that village chiefs feel unable to resolve or have tried to resolve but one party refuses to accept the ruling. The chief of a village between Guiglo and Bloléquin told Human Rights Watch that he had over 40 remaining unresolved cases.[75] Another village chief, when asked how many cases he had, picked up his notebook and showed page after page of registered complaints. “We’re overwhelmed,” he said.[76] While land dispossession linked to the post-election crisis exists throughout the regions of Guémon and Cavally, the areas with the most acute problems appear to be in the department of Bloléquin.[77]

The dominant story told by Gbagbo supporters in Liberia and Abidjan is that armed Burkinabés, aided by the Ivorian security forces, have forcibly seized land belonging to the Guérés and other typically pro-Gbagbo ethnic groups.[78] In the locations investigated, Human Rights Watch found little evidence of such acts on a widespread scale. However, the less hostile forms of land dispossession that have occurred on a large scale in western Côte d’Ivoire raise similar problems for the original landowners. In the vast majority of cases documented by Human Rights Watch, land dispossession linked to the crisis is rooted in illegal land sales: When Guérés were displaced by the conflict, other Guérés—from neighboring villages, or even the same family—came in behind and sold land that did not belong to them, most often to recent arrivals of Burkinabé migrants. The seller, who often engaged in theft and fraud, gets off scot free. While some Burkinabé buyers purchased in good faith, others were complicit, clandestinely buying enormous parcels of land from young Guérés whose legal authority to sell such land would have been questioned by any reasonable person. The guilty parties benefit, without fear of sanctions, while the true landowner suffers greatly.

In a minority of the cases documented by Human Rights Watch, land dispossession has occurred by force, rather than by illegal sale. Some non-natives used a landowner’s absence to increase their landholdings, for example when a person who purchased and confined himself to two hectares before the crisis seized and planted on additional hectares, to which he has no claim, while the owner was displaced. Finally, in a very small number of cases, groups of non-natives have wholesale commandeered land. These cases appear confined to forest areas that are located near government-owned protected forests, particularly the protected forest of Goin-Débé. Perhaps thinking that they were installing themselves in the protected forest, these groups occupied areas in the immediate vicinity, but on land owned privately by people displaced by the conflict.

In all cases of land dispossession linked to displacement, the Ivorian government has failed to fulfill its responsibilities under the African Union Convention for the Protection and Assistance of Internally Displaced Persons in Africa (Kampala Convention), which requires states to “take necessary measures to protect individual, collective and cultural property left behind by displaced persons”[79]; and the United Nations Principles on Housing and Property Restitution for Refugees and Displaced Persons, better known as the Pinheiro Principles.[80] The Pinheiro Principles, which draw from the rights to property, home, and housing, as well as the recognized right to a remedy for human rights violations,[81] state that “[a]ll refugees and displaced persons have the right to have restored to them any housing, land and/or property of which they were arbitrarily or unlawfully deprived.”[82]

Land dispossession linked to the crisis has devastating consequences on livelihoods and food security, as people are unable to access land where they grew food and cash crops. Given the longstanding tension over land in western Côte d’Ivoire and land’s significance for livelihoods, land conflicts created by the crisis bring the potential for inter-communal violence should the government fail to take measures to ensure restitution. Several cross-border attacks from Liberia in March 2013 appear directly related to land conflict.

In response to Human Rights Watch’s findings that the current victims of land dispossession in western Côte d’Ivoire come overwhelmingly from the Guéré ethnic group, which largely supported Gbagbo, the Ivorian government said any such ethnic element to land dispossession was not the result of government policy or the “indifference of the current authorities.”[83] It stated further:

The government would like to point out that, in any event, land conflicts in the West are not the result of any policy of colonizing land to the detriment of the “native” ethnic group. Moreover, certain illegal or illicit land occupations by other ethnic communities should not be seen as “collective punishment.”[84]

Human Rights Watch did not find evidence suggesting that land dispossession in western Côte d’Ivoire was a result of a state-organized policy or that local authorities were discriminating against Guérés in resolving land conflicts. As discussed in Section III, the Ivorian government’s breach of its human rights obligations comes primarily from the lack of support it has provided to ensure land restitution for victims, not from overseeing the confiscation of Guéré land.

However, the Ivorian government would be remiss if it were to deny or pretend away the ethnic and political nature of the land dispossession. The reality is that the victims of land dispossession in the region of western Côte d’Ivoire examined by Human Rights Watch overwhelmingly come from an ethnic group that widely supported Gbagbo. By ensuring the swift and fair resolution of their claims for land restitution, the Ivorian government could demonstrate that it represents and protects the rights of all residents in Côte d’Ivoire.

|

Land Transactions in Western Côte d’Ivoire Almost every land transaction in rural Côte d’Ivoire occurs outside of the system established by Ivorian law. As discussed in the Background, after a transition period that allows people to formalize their customary rights, the 1998 rural land law will only recognize land sales that occur through the transfer of a land title registered in the state cadastre. Rural land transactions with non-Ivorians, including long-term leases or rental agreements, should also occur through formal written documents registered with the cadastre. Yet these procedures are almost never followed, and in practice, custom remains the basis for land transactions. Indeed, almost no one in western Côte d’Ivoire has started, much less finalized, the process to register their land ownership.[85] People reported several barriers to formalizing land rights, including expenses associated with the process of obtaining a land certificate; the poor promulgation of the 1998 law; and the fact that private, individual land ownership runs counter to centuries of customary practice.[86] In western Côte d’Ivoire, many land transactions occur orally. Other transactions are written down and signed on petits papiers (literally, “small papers”), essentially anything that is available, from notebooks to rice sacks. Customary authorities—including the village and land chief—often act as witnesses to oral and informal written agreements. Ivorian law gives petits papiers no legal authority,[87] though in resolving disputes they could provide crucial evidence in terms of the area and nature of the transaction, for example a sale versus a rental agreement. Due to the widespread destruction and burning of houses in western Côte d’Ivoire during the conflicts, many petits papiers from previous transactions no longer exist. In such cases, people adjudicating disputes rely on, for example, the testimony of witnesses to the original agreement; a determination of how the land has been used since the agreement; and the knowledge of village experts, including the land chief. Fraudulent land transactions that occurred while the landowner was displaced by the crisis look much like regular land transactions, as they are done orally or in informal written agreements. One common difference, however, is in the involvement of customary authorities. Most, though not all, land transactions rooted in custom include witnesses, particularly from the customary authorities. However, fraudulent land transactions, including those that have marred western Côte d’Ivoire in the aftermath of the post-election crisis, tend to occur clandestinely—without family, community, or customary leaders to point out that the seller has no right to the land he is offering. |

Illegal Sales by Other Guérés

In almost all of the 27 villages visited between Guiglo and Toulepleu, Human Rights Watch documented cases of land dispossession that were rooted in illegal land sales while the landowner was displaced by the post-election crisis. Indeed, 72 of the 117 cases of alleged land dispossession documented by Human Rights Watch were related to illegal land sales—with members of the Guéré “native” population taking advantage of another Guéré’s displacement to illegally sell the person’s land to a “non-native,” generally a Burkinabé. Illegal sales involved both virgin forest and land already in production—with buyers either ripping up the owner’s old crops or appropriating them.

The vast majority of Guéré community leaders in western Côte d’Ivoire interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that illegal sales by their compatriots are the biggest source of illegal occupation linked to the crisis. Many such sales involve land to which the seller had no known link. Sellers who hold themselves out as the rightful owner while knowing this to be false commit crimes, including fraud and theft. The chief of a village between Bloléquin and Zomplou said:

There have always been land conflicts, but after the crisis, it’s a whole new world…. I haven’t had any cases of occupation by force [in my village]. The conflicts are from illegal sales, often by youth. The buyers are new Burkinabé [migrants], not the ones who lived with us before the crisis…. Someone comes back from Liberia and sees Burkinabés on his land, and they tell him so and so installed them. That person had no claim to the land, but now drives around on a nice motorbike.[88]

A village chief on the Bloléquin-Tinhou axis likewise told Human Rights Watch:

For the most part, it’s not occupation by force. It’s illegal sale. [Other Guérés] sold our forests while people were displaced. The non-natives didn’t just occupy the forest on their own…. You come back [from being displaced], go into your forest, and find a non-native there, and he says X sold him the land—though that person had no right to that land![89]

Leaders from non-native communities describe a similar problem. A Burkinabé leader in Guiglo said that “the natives who remained in the area or who returned quickly from being displaced profited greatly from their compatriots’ absence to sell land to non-native Ivorians and immigrants. The real owner returns to see his plantation has been taken over…. We’ve been inundated with these problems.”[90] A non-native community leader on the Duékoué sub-prefecture’s land committee (see Section III) likewise said that most crisis-related cases they receive “are from Guérés who return to see that their plantation has been sold. We don’t really see cases where a non-native just went and occupied a forest. It’s almost always based on a sale, an illegal sale, from another Guéré.”[91]

Most cases documented by Human Rights Watch involved fraudulent sellers with no family relation to the true owner, often from a neighboring village. Many dispossessed Guéré landowners voiced anger primarily at the illegal seller, though the transaction also pits them against the buyer, generally an immigrant. A Guéré in Pohan-Badouebly described his situation, which was representative of many others:

When I came back from Liberia [in late 2011], a youth Guéré from Blédi [the next village] had sold more than 10 hectares of my family’s land. Everything is taken—the 1 ½ hectares where we’d planted cocoa, and land that used to be virgin forest…. There are at least 13 Burkinabés in my forest. When I found them there, they told me that they bought it from [name omitted] for more than 100,000 CFA (US$200) per hectare…. They’ve cut down much of the forest and are planting cocoa.

The Blédi youth never said that it was his land before the [2010-2011] war. My grandfather, [who died before I was born], worked that land. That land is where I was brought into this world…. We’ve never sold it, that land is my family’s wealth. Now it’s been destroyed. Where we grew food before, they’ve even pulled that up to plant cocoa…. I can’t access my forest, I can’t feed my children. We just grow a little rice and manioc by the village to survive. It really angers me.

I’ve filed a complaint with the local authorities, but the Blédi youth never comes when the canton chief [a traditional leader] summons him…. I don’t even have the 1,000 CFA ($2) to go to Bloléquin to bring the case to the sub-prefect…. I don’t have any problems with the Burkinabés there. They’re honest with me, they told me who sold them the land. It’s the Guéré in Blédi who I have a problem with. We have so many cases like this. The [youth] sell land that’s not theirs and then go buy a motorbike.[92]

A 68-year-old man from Douedy-Guézon likewise described how separate Guéré sellers from a neighboring village fraudulently sold his land while he was displaced:

I’ve been working my family’s land since 1969. To my great surprise, after the crisis, my entire parcel had been sold, right up to the door to my hut in the campement…. I returned from exile in January 2012. When I returned, I saw that my forest had been cleared. I found Burkinabés on the land, three different buyers who have brought other non-natives to work with them. I’d never seen these Burkinabés before, they weren’t ones who lived with us before the crisis…. When I asked them who had given them this land, they told me [names omitted], Guérés from Bédi-Goazon. I have to be clear, the Burkinabés didn’t install themselves on my land….

The Guéré [sellers] aren’t even neighbors of mine. They’re from the same area, but we don’t share boundaries. Never before had they stepped foot on my land, made any claim to it. Since 1969, I’ve planted rubber trees, coffee, and cocoa. I had a hectare of rubber trees that I was planning to extend [into my virgin forest] … and five hectares of cocoa, but they’ve taken that all over. Some of it was already in production. How can you sell someone’s land that’s already producing?

All of my land is taken, I don’t know how I will get money this year. I don’t even know where I can plant rice to sustain my family…. I brought a complaint against one seller to the village chiefs [of Douedy-Guézon and Bédi-Goazon] and against the other seller to the sub-prefect, though he sent me back to the village chiefs. They’ve tried twice to summon one of the sellers for a meeting, but he doesn’t show up. It’s been since January 2012, and I still can’t access my land.[93]

In some cases documented by Human Rights Watch, it was another family member who illegally sold the land. For example, a 58-year-old man in Tinhou said that his nephew, in his 30s, sold the man’s land while he was a refugee in Liberia: “The youth recognizes that he did it, that he had no right to the land. We’re trying to resolve this within the family for now, not involve the authorities. He sold two hectares to a Burkinabé family. I told them to leave, but they said they gave money for the land. They’re putting down cocoa.”[94]

Throughout western Côte d’Ivoire, customary leaders and victims of land dispossession said that many of the illegal land sellers were young men “flouting the family hierarchy or just looking to make quick money off of a neighbor’s land they know they have no right to.”[95] One Guéré interviewed fled Koadé-Guézon in March 2011 and returned in March 2012 to discover that his 20-year-old cousin had sold 12 hectares of the man’s land. The illegal seller promptly left the area and was no longer reachable at his former phone number. “He sold my land and then left,” the victim told Human Rights Watch. “It was virgin forest before, and now the Burkinabé [buyers] have cut down trees to start planting. I recently filed a complaint, but it hasn’t yet been heard.”[96]

Human Rights Watch documented cases involving illegal land sales by people as young as 17 years old. Guéré land is often considered owned by families, rather than individuals, which means few youth of that age have the right to sell land without the head of family agreeing.[97] In cases like this, many community leaders and victims of land dispossession felt that both the buyer and illegal seller were to blame. A village chief involved in resolving land disputes in a village between Guiglo and Bloléguin said:

We have to stop illegal buying and selling, clandestine buying and selling. That’s what causes all of these problems…. The illegal sellers are often less than 25 years old, that’s why I blame the buyers too. A little kid of 18, 19 years old says he’s selling you 5, 10, even 20 hectares of land, and you don’t think about perhaps checking with the head of family, or village authorities, or even the head of your [non-native] community? [The buyer] knows what he is doing [is wrong].[98]

In examining and resolving land dispossession in western Côte d’Ivoire linked to the post-election crisis, it is therefore appropriate to distinguish between good-faith Guéré sellers, who reasonably believe they have a claim to the land, and bad-faith Guéré sellers, who knowingly engage in theft and fraud. It is likewise appropriate to distinguish between good-faith non-native buyers, who pass through local authorities when making a purchase, and bad-faith non-native buyers, who take advantage of the anarchy to buy land from someone whose ownership claim would be questioned by any reasonable person.

Guérés in western Côte d’Ivoire, particularly around Bloléquin, felt that many problems arose when a flood of new Burkinabé migrants arrived after the crisis. A Burkinabé leader in Bloléquin admitted that they had problems controlling some of the new migrants:

Some of our brothers who come, they don’t present themselves to the village chief or even the Burkinabé chief in that village. They go into the forest and buy land clandestinely. I have to admit it’s a problem. It tarnishes the image [of all Burkinabés in the region]. We’ve tried to sensitize, the sub-prefect here has also tried to sensitize, but people don’t listen—some Guérés still sell clandestinely, and some Burkinabés still buy clandestinely.[99]

A Burkinabé leader in Guiglo said similarly:

The new migrants are causing problems. They have come [generally from elsewhere in Côte d’Ivoire, particularly around Soubré and San Pedro] with a lot of money in their pockets. They are buying up huge areas of land, and then they quickly have problems in terms of who is the rightful owner and where the correct boundaries are.[100]

The problem of illegal land sales is comparatively less severe in villages around Duékoué, an older cocoa growing region where there is little remaining virgin forest. Beginning in Guiglo, the problems grow more and more severe the further west one moves, becoming the most extreme after the town of Bloléquin, before arriving in the department of Toulepleu. The sub-prefect in Doké told Human Rights Watch:

Before the crisis, it was almost all virgin forest here. People who live west of Bloléquin hadn’t ceded their forests [like the Guérés elsewhere]. Since the crisis, non-natives, [mostly Burkinabés] are coming in from Soubré, Bangolo, San Pedro that have never been here before. They are buying massive amounts of land—sometimes as much as by the [square] kilometer [100 hectares], even two [square] kilometers.[101]

As discussed in Section IV, the failure of the Ivorian government to prevent land dispossession while people were displaced or to ensure victims obtain swift and effective redress violates their rights as set out in the Kampala Convention and the Pinheiro Principles.[102] It also deprives them of their right to property guaranteed by article 14 of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights.[103]

Refusal to Pay Rent

Many Guérés in western Côte d’Ivoire have historically entered into rent agreements with non-natives, a practice commonly referred to as “travail partagé.” This roughly translates as “shared work,” though the system might be more accurately described as the “shared fruits of the non-native’s work.” Some Guérés interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that, after the crisis, non-natives who work for them no longer abide by the former rent agreement. Human Rights Watch primarily documented these cases in villages around Duékoué, a region where most land was already in use prior to the crisis.

There are two predominant kinds of travail partagé arrangements. In both, the Guéré tuteur provides a parcel of land to a migrant, who works the land. In the first type of arrangement, the landowner and renter split the crop for the entire area ceded to the renter—with each party then responsible for selling his portion. In the second type of arrangement, the landowner and renter split the money from the sold crop.

A Guéré man from Diahouin, a village north of Duékoué, described how a Burkinabé who had worked on his land for more than 15 years no longer followed their agreement:

I fled in 2011 when the [FRCI] were coming toward Duékoué and didn’t come back until after [the July 2012 Nahibly IDP camp attack]. Before the crisis, we shared the cocoa revenue. I gave him two hectares on which to plant, and we agreed to do travail partagé. It happened every year, until the crisis. Now, he shares it with himself. After this harvest, he went and sold the cocoa without even calling me, and when I confronted him about it, he said there was no money for me. Before, if we sold 100,000 CFA ($200) of cocoa, he took 50,000 CFA, I took 40,000 CFA, and 10,000 CFA went to treat the fields. Now, I get nothing…. Since the crisis, they are the bosses.[104]

Human Rights Watch documented two cases involving Guéré women who said that, since inheriting land, the renter had refused to continue paying rent paid when the woman’s father or husband, respectively, was alive.[105] One of the cases originated with the crisis, during which the 52-year-old woman’s husband died:

My husband [separately] installed three Baoulés [years ago], who planted cocoa. [The cocoa] has been in production for several years. Two of them were just workers, but one had a rent agreement with my husband…. My husband died in February 2011, and I fled in March when the war arrived. I was [displaced] at the Catholic mission [in Duékoué]. Since coming back to the village, the Baoulé has not paid rent. In 2012, I received nothing. So far in 2013, nothing…. I’ve tried to call him to the village to resolve this, but he doesn’t come…. Nobody responds to me. For me as a woman, it’s not easy to go into the bush after them.[106]

The claims related to rent can be difficult to assess. Most Guérés who complained about non-natives’ refusal after the crisis to continue honoring rent agreements said the contract had been oral. Others said there had been a written agreement on informal papers, but those had been destroyed along with people’s homes during the crisis. In such cases, authorities would likely need to establish that both parties had accepted and carried out the division every year—or with every cocoa harvest—prior to the crisis, demonstrating that such an agreement existed.

In cases where there was an agreement to pay annual or seasonal rent, the failure to do so as a result of a person’s displacement would, like an illegal sale, violate the right to property under the African Charter.

Illegal Extension of Acquired Parcels

In some villages, Human Rights Watch documented cases where non-natives who previously acquired some of an owner’s land appear to have illegally extended their holdings while the owner was displaced. Assessing these claims’ credibility is again complicated by the fact that parties often carried out the original land transaction orally or on informal papers that were never filed with local authorities and were then destroyed during the crisis when armed forces burned homes.

A Guéré man in Guinkin said that, decades before the crisis, his uncle ceded to a Burkinabé family a hectare of land and a plot to build their home. When the Guéré returned from being displaced by the crisis, he found that the Burkinabé had planted rubber trees on several additional hectares that the Burkinabé had never received or made claim to. The Guéré told Human Rights Watch: “I can’t stop him from working the land my uncle ceded to him, but he can’t take the rest of my family’s forest. I asked him why he had planted there, and he said he thought everyone [in my family] had died during the crisis.”[107] The man said he was trying to resolve the dispute through customary leaders and with the help of a humanitarian organization, but would file a complaint with the court system if they did not quickly succeed in removing the Burkinabé from the additional land.[108]

A Guéré in Petit-Guiglo described another such case:

When I came back from Liberia in late 2012, I saw that Burkinabés who work for me had taken over land I never sold to them. There were five Burkinabés on my land before the crisis, on five hectares total…. There are now seven Burkinabés, and they are working on 12 total hectares. Before, the other seven hectares was virgin forest, I never sold it. I went to them and said who gave this to you, why are you on this land. And one said, “[Name omitted], you weren’t here.” I’m not fine with them taking this land. This is for my children, for future generations.

About a month ago I brought a complaint to the sub-prefect, who said he would come to Petit-Guiglo, but he hasn’t yet…. This really angers me, but I don’t want a fight, that’s why I haven’t chased them off the land. For now, I am waiting for the sub-prefect to come. If I push them off the land, tomorrow they’ll say that the population of Petit-Guiglo doesn’t accept foreigners. I have no problem with them working the [original] five hectares, but they can’t just take the rest of my land.[109]

At times, the illegal extension runs into the land of a neighboring owner, as described by a resident of Dedjéan village:

I returned from Liberia in January 2013 and found that the little land I own had been taken over by a Burkinabé. I went into the bush and said, “Why are you on my plantation?” I saw that he was losing his temper, so I returned to the village. I was scared…. He isn’t a new migrant. Since well before the [2002-2003] crisis, he worked for a Guéré whose land borders my own. When I was in Liberia, the Burkinabé crossed into my land. He had never done so before, never made any claim to it. Maybe he thought I wouldn’t return. But he has cut down [part of] my forest and planted cocoa.