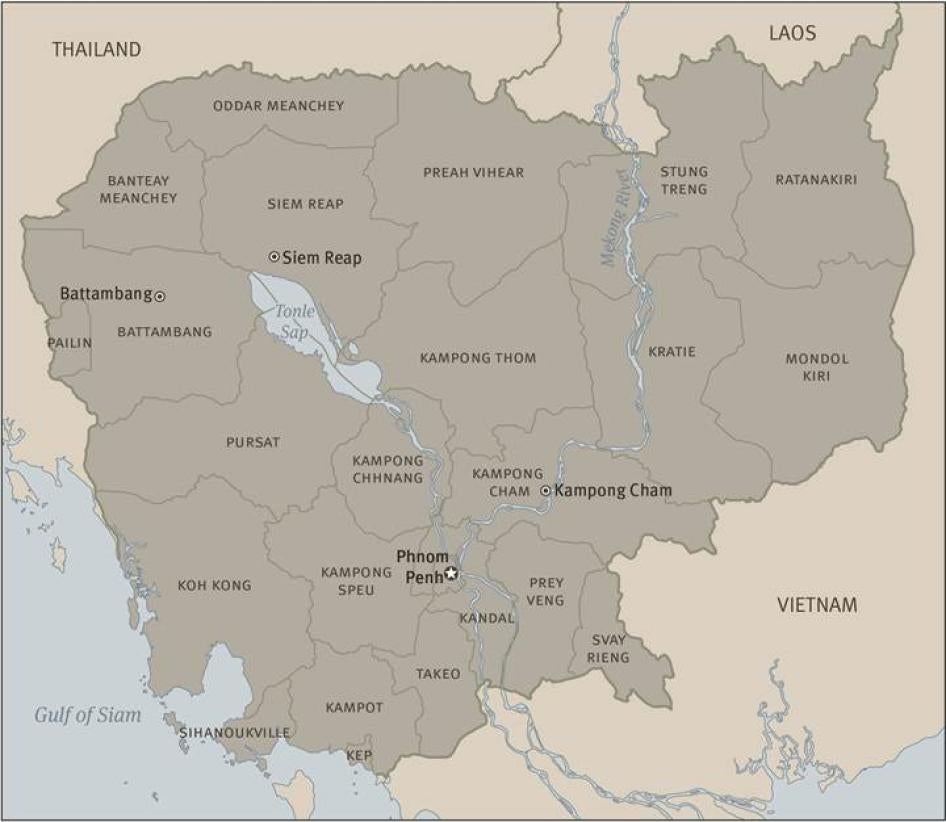

Map of Cambodia

© 2012 Human Rights Watch

Summary

In early 1993, ahead of elections organized by the United Nations, four Cambodian political activists, all recently returned refugees, were abducted by soldiers in Battambang province in northwest Cambodia. The four were taken to a nearby military base. They were never seen again.

Dozens of people witnessed these abductions. Investigations by the United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC), the peacekeeping mission created by the 1991 Paris Agreements, revealed the identity of the men responsible. The case became one of the first in which UNTAC’s special prosecutor, created to address the wave of human rights abuses carried out with impunity by government forces, took action.

Though the State of Cambodia (SOC) -- the official name of the country at the time, led then and now by Prime Minister Hun Sen and his Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) -- and the other three parties to the Paris Agreements had formally committed to protecting human rights and to cooperating with UNTAC, the SOC administration and its security forces refused to cooperate with UNTAC’s investigation. The SOC not only denied the involvement of its forces in the abductions, it conducted a campaign of threats and intimidation against witnesses for talking to UNTAC.

Faced with state-sponsored killings and state refusal to bring the perpetrators to justice, on March 8, 1993 an UNTAC special prosecutor issued arrest warrants for six soldiers and their commander, Captain Yon Youm, on charges of murder, battery with injury, illegal confinement, and infringement of individual rights. UNTAC attempted to deliver the warrants to the soldiers’ base in Sangke district in Battambang province, but found the base deserted. None of the seven suspects was ever arrested.

Yon Youm and other members of the SOC security forces remained in uniform and went on to conduct a systematic and officially protected campaign of extortion, kidnapping, and murder between late June 1993 and early 1994. Cambodia’s military prosecutor, UNTAC, and the successor UN human rights field office in Cambodia documented these abuses. According to eyewitness accounts, at least 35 people were abducted and temporarily detained in a secret detention facility in Battambang town. They were then taken to Chhoeu Khmao, a remote location in Ek Phnom district, where almost all were summarily executed.

The main unit responsible for carrying out the abductions and executions was a Special Intelligence Battalion, code-named S-91, of the army’s Fifth Military Region. At that time S-91 was under the direct command of Yon Youm. Despite the evidence against him and the UNTAC arrest warrant, Yon Youm had by 1994 been promoted to the rank of colonel. He is now deputy chief of staff of the Fifth Military Region in Battambang. Neither he nor anyone else responsible for the atrocities in Battambang has ever been held accountable for these crimes.

More than twenty years after the signing of the Paris Agreements, Yon Youm is emblematic of the culture of impunity that continues to characterize the Cambodia of Prime Minister Hun Sen and the CPP. The message to Cambodians is that even the most well-known killers are above the law, so long as they have protection from the country’s political and military leaders.

* * *

On October 23, 1991, the Paris Agreements on a Comprehensive Political Settlement of the Cambodia Conflict were signed by the four warring Cambodian political organizations and 18 states.[1] The Paris Agreements were supposed to bring an end to the post-Khmer Rouge era civil war between the Vietnamese-installed government, led since 1985 by Hun Sen, and the US and Chinese-backed resistance forces, led militarily by the Khmer Rouge and politically by Prince Norodom Sihanouk, Cambodia’s ousted monarch. It was also supposed to usher in a new era of human rights. The promise of Paris was that there would be no more atrocities like those committed by S-91 and Yon Youm, but if they did happen the rule of law would hold perpetrators accountable.

Sadly, the case of Yon Youm and Chhoeu Khmao is not exceptional. The involvement of senior government officials and military, police, and intelligence personnel in serious abuses since the Paris Agreements has been repeatedly documented by the United Nations, the US State Department, domestic and international human rights organizations, and the media. Despite the human rights provisions of the Paris Agreements, the human rights protections in Cambodia’s 1993 constitution, and Cambodia’s accession to the main international human rights treaties, almost no progress has been made in tackling impunity over the past two decades. Instead, perpetrators have been protected and promoted.

Killings, torture, illegal land confiscation, and other abuses of power are rife around the country. More than 300 people have been killed in politically motivated attacks since the Paris Agreements. In many cases, as with members of the brutal “A-team” death squads during the UNTAC period and military officers who carried out a campaign of killings after Hun Sen’s 1997 coup, the perpetrators are not only known, but have been promoted. Yet not one senior government or military official has been held to account. Even in cases where there is no apparent political motivation, abuses such as extrajudicial executions, torture, arbitrary arrest, and land grabs almost never result in successful criminal prosecutions and commensurate prison terms if the perpetrator is in the military, police, or is politically connected. It is no exaggeration to say that impunity has been a defining feature of the country since the signing of the Paris Agreements.

To illustrate the problem, this report details some cases of extrajudicial killings and other abuses that have not been genuinely investigated or prosecuted by the authorities [we have focused on some cases, but could have included many others as the examples are vast]. These cases include:

- The killing of dozens of opposition politicians and activists by the State of Cambodia during the UNTAC period in 1992-93.

- The murder of opposition newspaper editor Thun Bun Ly on the streets of Phnom Penh in May 1996.

- The slaughter of at least 16 people in a coordinated grenade attack on opposition leader Sam Rainsy in March 1997 in which the US Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) implicated Prime Minister Hun Sen’s bodyguard unit.

- The campaign of extrajudicial executions of almost 100 Funcinpec-affiliated officials after Hun Sen’s July 1997 coup, including senior government official Ho Sok, in the Ministry of Interior compound.

- The 1999 acid attack that disfigured 16-year-old Tat Marina by the wife of Svay Sitha, a senior government official.

- The 2003 execution-style killing of Om Radsady, a well-respected opposition member of parliament, in a crowded Phnom Penh restaurant.

- The 2004 killing of popular labor leader Chea Vichea.

- The 2008 killing of muckraking journalist Khim Sambo and his son while the two exercised in a public park.

- The 2012 killing of environmental activist Chut Wutty in Koh Kong.

This report is based on information from various sources, including UNTAC documents, reports of UN special representatives and rapporteurs and the Cambodia Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights [previously the UN Centre for Human Rights], reports by Human Rights Watch and other international and local nongovernmental human rights organizations, and media accounts. It is also based on interviews over many years with current and former government officials, members of the armed forces, the police, the judiciary, parliament, and other state institutions, and representatives of political parties, labor unions, the media, and human rights organizations.

The report adopts the definition of impunity put forward in 1997 by Louis Joinet, a former UN special rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers:

The impossibility, de jure or de facto, of bringing perpetrators of human rights violations to account—whether in criminal, civil, administrative or disciplinary proceedings—since they are not subject to any inquiry that might lead to their being accused, arrested, tried and, if found guilty, sentenced to appropriate penalties, and to making reparations to their victims.[2]

International treaties to which Cambodia is a party obligate governments to address impunity and provide redress for violations of human rights. The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) requires governments to ensure that any person whose rights or freedoms are violated to have an effective remedy before competent judicial, administrative or legislative authorities, “notwithstanding that the violation has been committed by persons acting in an official capacity.”[3]

Recognizing that impunity can be an important contributing element in the recurrence of abuses, the UN Human Rights Committee, the international expert body that monitors compliance with the ICCPR, has stated that governments that violate basic rights “must ensure that those responsible are brought to justice.” Both the failure to investigate and to bring to perpetrators to justice “could in and of itself” be a violation of the ICCPR. [4]

* * *

In the twenty years since Paris, Cambodia has in many ways changed beyond recognition. The Paris Agreements and UNTAC wedged open space for political parties and civil society organizations. By 1998 the Khmer Rouge had collapsed and armed conflict had finally come to an end. Cambodia’s economy has become more integrated with regional economies. Donors and development agencies have succeeded in improving many human development indicators. The isolation of the Cambodian people from most of the rest of the world has come to an end.

Yet the last two decades have also been a story of missed opportunities. Serious abuses and repression continue. Corruption characterizes the economy, political opposition parties and free media have been slowly but steadily quashed, and NGOs face regular threats and constant pressure. Senior officials are not held accountable under law. None of this is surprising, as one leader, Hun Sen, and one political party, the CPP, have dominated Cambodia throughout. Authoritarian with a propensity for violence, Hun Sen has been prime minister for more than 27 years. A formerly communist party that has turned capitalist yet retained its pervasive security apparatus down to the village level, the CPP has been in power since 1979. Neither Hun Sen nor the CPP have shown any intention of developing a genuine democracy or allowing the kind of political pluralism envisioned by the Paris Agreements. Cambodia is in the process of reverting to a one-party state.

Only with a renewed sense of commitment and purpose from foreign governments, the UN, and donors can the many brave Cambodian human rights defenders and civil society activists succeed in transforming Cambodia into the rights-respecting democracy promised in Paris. An essential place to start is by addressing the culture of impunity that pervades the country and fatally undermines all efforts at reform. As the UN special rapportteur on human rights, Professor Surya Subedi, said on the twentieth anniversary of the Paris Agreements, “ T he Agreements will remain relevant until their vision is a reality for all Cambodians.” [5]

I. The Paris Agreements and Developments Since 1991

At the same Kleber Center where in 1973 the United States and Vietnam signed their Paris Peace Agreement, on October 23, 1991, 18 countries, including all five permanent members of the UN Security Council and the four warring Cambodian parties, signed the Agreements on a Comprehensive Political Settlement of the Cambodia Conflict. Cambodians hoped that the Paris Agreements would lead to the end of the more than decade-long civil war with the Khmer Rouge, raise abysmal living standards, and improve respect for basic human rights. Foreign diplomats, who celebrated the new agreement at a reception at the Versailles Palace Library, hoped to cross Cambodia off the list of Cold War issues that had long bedeviled relations among the United States, the Soviet Union, China, and Vietnam.

Because of the unprecedented brutality of the Khmer Rouge period from 1975-1979 and the oppressive one-party rule that followed from 1979-1991, the protection of human rights was a central theme of the Paris Agreements. A section in Annex 1, entitled “Human Rights,” stated that the newly created United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia ( UNTAC), would make provisions for:

a) The development and implementation of a programme of human rights education to promote respect for and understanding of human rights;

b) General human rights oversight during the transitional period;

c) The investigation of human rights complaints, and, where appropriate, corrective action.[6]

To bind the four Cambodian parties and 18 signatory states to their human rights commitments, the Paris Agreements were unusually prescriptive in laying out, “ Principles for a New Constitution for Cambodia.” These provisions would be applicable after UNTAC left Cambodia, which it did on schedule in September 1993. Human-rights-related provisions are contained in Annex 5 and include:

2. Cambodia's tragic recent history requires special measures to assure protection of human rights. Therefore, the constitution will contain a declaration of fundamental rights, including the rights to life, personal liberty, security, freedom of movement, freedom of religion, assembly and association including political parties and trade unions, due process and equality before the law, protection from arbitrary deprivation of property or deprivation of private property without just compensation, and freedom from racial, ethnic, religious or sexual discrimination. It will prohibit the retroactive application of criminal law. The declaration will be consistent with the provisions of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other relevant international instruments. Aggrieved individuals will be entitled to have the courts adjudicate and enforce these rights….

4. The constitution will state that Cambodia will follow a system of liberal democracy, on the basis of pluralism. It will provide for periodic and genuine elections. It will provide for the right to vote and to be elected by universal and equal suffrage. It will provide for voting by secret ballot, with a requirement that electoral procedures provide a full and fair opportunity to organise and participate in the electoral process.

5. An independent judiciary will be established, empowered to enforce the rights provided under the constitution.[7]

The Paris Agreements mandated the creation of UNTAC, at the time the largest and most expensive UN peacekeeping mission ever. UNTAC, with both civilian and military components, had many tasks, including supervision of a ceasefire; cantonment and disarmament of the Cambodian signatories’ armed forces and the creation of a new national army; control of the existing administration of each party, the largest of which was run by the SOC; the staging of multi-party elections; and the protection of human rights.

Faced with resistance from the SOC and the Khmer Rouge, UNTAC failed or made only partial progress in all these areas. One major accomplishment was presiding over a largely peaceful vote in May 1993 for a Constituent Assembly, although this was marred by a massive campaign of violence and intimidation in the run-up to the election by the SOC against opposition parties and activists. The Khmer Rouge withdrew from the process and carried out many atrocious attacks, often against the ethnic Vietnamese community. The Constituent Assembly adopted a new constitution in September 1993, which includes a long list of fundamental rights that remains in place today, though is largely ignored in practice.

The Paris Agreements were supposed to transform Cambodia. In many ways they did. Over the past 20 years Cambodia has changed dramatically. As of 1991 the country still suffered egregiously from the horrors of the Khmer Rouge period, with a physically and psychologically devastated population, absence of basic infrastructure, and little in the way of health care, education, or industry. Before Paris most Cambodians struggled to obtain basic necessities, due both to the crippling embargo imposed by the US and its allies after the 1979 Vietnamese invasion and the SOC’s mismanaged and corrupt state-controlled economy. Civil rights were routinely trampled upon and government institutions existed outside of the rule of law.

After Paris, the country quickly reintegrated into first the regional and then the world economy. The country was opened to foreign investors, who were given huge tax breaks and other incentives – but with obligatory bribes to government officials at all levels. Some invested in emerging industries such as Cambodia’s garment sector, creating employment for hundreds of thousands. Others operated hand-in-hand with Cambodian officials to plunder the country’s natural resources, particularly its dwindling forests. Roads, schools and health clinics have been built, largely with the more than $10 billion of donor money provided since Paris, though the gains are more evident in urban areas. Cambodia’s large rural population suffers from widening inequality in incomes and opportunities, as well as persistent poverty, despite overall poverty reduction .

One of the most significant accomplishments of the Paris Agreements was to open the country to the world, which over time has had a profound effect on many Cambodians. Paris and UNTAC wedged open space, grudgingly conceded by the CPP, for Cambodians to read and learn about the world – from which most had been closed off for nearly two decades – and their own country. Whereas before Paris open forms of dissent were not tolerated, Cambodians are now free to speak their minds on most subjects, although often at a cost when they do so in a politically confrontational manner. Most significantly, Cambodia now has a thriving and critical nongovernmental sector, which because of government indifference and malfeasance often provides basic services that a more functional state would deliver.

The controversial inclusion of the Khmer Rouge as one of the parties to the Paris Agreements ultimately led to the movement’s demise, as China kept its part of the bargain and cut off aid and military backing, thereby isolating and weakening the Khmer Rouge, who enjoyed virtually no popular support. By 1996 senior Khmer Rouge leaders began defecting to the government. By the end of 1998, both Pol Pot and the murderous movement he controlled were dead, transforming the lives of millions of Cambodians who suffered from war for decades.

Yet the country has made strikingly little progress in creating a culture of good governance and the rule of law. Most Cambodians remain very poor, in part because of breathtaking levels of corruption that have enriched government officials and discouraged honest foreign investors. Despite low official salaries, high-ranking government officials are often very wealthy, owning large villas, luxury cars, and major stakes in business enterprises. Indeed, no one has ever explained how Hun Sen, who has been a government official since 1979, could afford the large house and compound in Kandal province that he has occupied since the mid-1990’s. Corruption is so bad – and is the subject that seems to most anger ordinary Cambodians – that in 2011 the World Bank suspended its assistance to Cambodia. A s long ago as 2005, the World Bank president, James Wolfensohn, said the government’s top three priorities should be, “fighting corruption, fighting corruption, and fighting corruption.” [8]

The state health and education systems remain weak and donor-dependent. Donors have augmented the country’s tiny tax base by providing approximately 50 percent of the state budget since Paris, but this has had the unintended consequence of allowing the government to spend much of its official resources on an inflated army and police, including a de facto private army for Hun Sen.

Since Paris, power has become increasingly centralized in the CPP and now resides primarily with Hun Sen, a former low-level Khmer Rouge commander who has been prime minister since 1985. [9] Eclipsing the party, he now takes all key decisions. All senior civilian and military officials report to Hun Sen, who has installed his own people in almost all of the leading positions in the cabinet, military, gendarmerie, and police. He runs both the government and a parallel network of governing authorities with an iron fist, demanding loyalty before competence. Local officials around the country frequently emulate his practices.

The result is the failure since Paris to build strong institutions to promote good governance, the rule of law, and respect for human rights. The National Assembly is a rubber stamp. The opposition is increasingly marginalized, with Sam Rainsy, the leader of the opposition, living in exile to escape long prison sentences for peaceful political activities.

The military and police have remained under political control since Paris. The security and intelligence forces have been party instruments since their reestablishment after the Khmer Rouge was ejected from power by the Vietnamese army in 1979. Hun Sen has personally controlled the police since the failed July 1994 CPP coup attempt against him, which implicated Chea Sim and members of his faction of the party. As recompense, Hun Sen demanded that Chea Sim allow him to appoint his own man, Hok Lundy, as national police chief. Lundy quickly established a reputation for brutality and became the most feared man in Cambodia. Loyal until his death in a 2008 helicopter crash, he was replaced by Neth Savouen, a relative by marriage of Hun Sen and also notorious for committing human rights abuses since the 1980’s. Neth Savouen is currently a member of the CPP Central Committee. [10]

After many attempts, Hun Sen in 2009 replaced General Ke Kim Yan with General Pol Sarouen as the head of the armed forces. Both are members of the CPP Central Committee, yet Ke Kim Yan is part of CPP President Chea Sim’s faction of the party, while Pol Sarouen has been linked to Hun Sen since their time in the Khmer Rouge in the 1970’s.

The courts and justice system are controlled by Hun Sen and the CPP. Most judges and prosecutors are CPP members who implement party directives, and believe they have no leeway to do otherwise. Most glaringly, Dith Munthy, the chief judge of the Supreme Court, is a member of the CPP’s Permanent Committee of the Central Committee and of the party’s six-person Standing Committee.[11] Like all senior party members, he is expected to place party loyalty over his official responsibilities.

II. Illustrative Cases of Impunity since the Paris Agreements

Long before the Paris Agreements, Cambodians had suffered abuses committed by the government and warring armed forces with impunity. After gaining independence from France in 1953, Cambodians have lived through one abusive regime after another, usually with foreign backing. From 1953-1970, Prince Norodom Sihanouk presided over a state that brooked little dissent and, from time to time, threatened, tortured, and killed its critics and political opponents. After General Lon Nol deposed Sihanouk in 1970, the country was plunged into full-scale civil war, with the US-supported army pitted against the Khmer Rouge, who were fronted by Sihanouk and backed by China and Vietnam. From April 17, 1975, until January 7, 1979, the Khmer Rouge presided over one of the most murderous regimes in human history. Up to two million people, perhaps a quarter of the population, perished from execution, disease, and starvation.

In 1979, Vietnam invaded Cambodia. The Khmer Rouge fled to areas along the border with Thailand. Vietnam created a new one-party state, the People’s Republic of Kampuchea, installing a government and party of Hanoi-trained communists and former Khmer Rouge fighters. The former Khmer Rouge fighters, which included Heng Samrin, Chea Sim, and Hun Sen, soon gained the upper hand, controlling the party and security forces. While the level of abuses under this government did not approach the horrors of the Khmer Rouge period, widespread human rights abuses were committed with complete impunity.

The post-Paris period was supposed to be different. The cases below illustrate that while many things have changed in the ensuing two decades, brutal state-sponsored human rights abuses still occur and, when they do, impunity still reigns.

UNTAC and A-Teams

UNTAC’s “Human Rights Component Final Report,” issued in September 1993, contained an appendix of “investigation statistics” listing types of abuses committed, the number of incidents and victims, and to whom UNTAC attributed responsibility. The report stated that the SOC had been responsible for 39 incidents of “killing of political opponents” that resulted in 46 “casualties” and 25 “killings the primary purpose of which is to intimidate the civilian population and other summary executions” that resulted in 40 “casualties.” The report listed hundreds of other cases of SOC abuses, including enforced disappearances and torture. The numbers in the report understate the extent of the violations since UNTAC could not investigate all cases or specify who was responsible in all cases it did investigate.[12]

Information gathered by UNTAC showed that those who committed abuses, including the police and army, operated as direct agents of the CPP under ministerial-level instructions as well as under the direction of provincial, district, commune and village officials. The perpetrators were involved both in intelligence-gathering activities directed at opposition political parties and individuals connected to those parties, and in suppressing the political activities of the opposition.[13]

UNTAC also gathered extensive evidence of SOC and CPP use of covert groups to carry out abuses. Some existed as distinct entities, while others operated within formal units, surfacing periodically when called into action. Some members of these groups worked for more than one group. They included former members of groups such as the A-3, set up in the 1980’s as “combat police” to fight resistance forces and to root out its suspected supporters in the country.

However, most were new groups set up by the CPP to prepare for the arrival of UNTAC and the return of opposition parties to Cambodia to contest elections. The most important of these groups were the so-called “A-Teams,” “T-Groups,” and “reaction forces,” which were created to obstruct the activities of opposition parties through violence and other means, and to infiltrate UNTAC.[14] These became instrumental in carrying out political violence and sabotage. Many secret groups are mentioned in United Nations files, some civilian and some not. Various code names were used by these groups, including A-90, A-92, A-93, A-48, A-50, S-21, S-22, S-23, X-09, X-90, T-30 T-90, and A-5.

Interviews with members of these units have confirmed their existence and provided details of their orders and the kinds of abuses they committed. Former senior cadres of the Ministry of Interior’s Defense of Political Security directorates were put in charge of strategy, while operational personnel were drawn from, among others, A-3 and Infantry Regiment 70,[15] a unit under direct command of the General Staff Department of the Ministry of Defense [this unit would later become infamous for abuses after it was renamed Brigade 70 and tasked with ensuring security and safety for senior government officials, including the prime minister].[16]

The functions of these groups do not appear to have been well understood until relatively late in UNTAC’s lifespan, by which time political violence was jeopardizing the peace process. An UNTAC report written in April 1993 states that, “A groups,” operating under the command of the Ministry of National Security, were “engaged in activities wholly detrimental to the creation of a neutral political environment.” The same document concluded that the SOC, knowing this was in violation of the terms of the Paris Agreements, had “taken every step to conceal their existence from UNTAC and the populace.” [17]

A Ministry of National Security document entitled “Building up A-92 Forces” obtained by UNTAC describes the role of A-92 in considerable detail. A covert command structure running from the commissioner or deputy commissioners of security in each province was established that recruited people with high standing, such as professors, teachers, medical practitioners, monks, and “other persons with influence among the ranks of the popular masses.” A-92 operatives were directed to infiltrate and subvert “all the various political organizations having a policy of opposition to the Cambodian People’s Party.” The aim was to uncover information about their strategies and supporters, and to disrupt them by seizing control of vital functions, including economic resources. Their functions included creating “misunderstanding among the popular masses about the opposition parties, to foment activities that undermine their reputations and interests, to create contradictions and splits among their forces, and to use pre-emptive methods to prevent the opposition parties from gaining the advantage in the election.”[18]

The document said that A-92 personnel would:

Carry out, either personally or through intermediaries, the destruction and forestallment of the stratagems, plans, methodologies, tricks and activities of the opposition parties which aim at expanding their influence and their membership and to destroy us. They are also to achieve any of a number of goals, primarily those such as eliminating the influence, propaganda and psychological warfare of the opposition parties, and in particular to eliminating their influence among the popular masses.

The document continued: “It is imperative to set up Assistance Groups both in the ministries and in the provinces and municipalities. These are to be selected from among the security forces.… The Ministry specifies that this document is to be kept top secret.”[19]

UNTAC records show that A-Teams and reaction forces encouraged and directed their members to carry out attacks and then cover up evidence of official complicity.[20] As reaction forces had no official links to SOC security forces, police were able to deny involvement. Documents uncovered in Takeo, Prey Veng, and Kampong Cham provinces show that members of the security forces were encouraged to meet quotas for incidents, and cover up CPP complicity by appearing to assist UN investigators. Thus, the same people who were behind the crimes were able to influence investigations.[21]

A former A-Team member, a leader of a covert team in one of Cambodia’s largest provinces, explained how T-90 worked:

T-90 was set up for action. It was made up of drunks, losers, young unemployed men, teenagers who would ride around on motos [motorbike taxis], drink, sing karaoke, etc. Often they would be assigned to start fights with suspects and the police would arrive and arrest both. The T-90 person would be released, while the suspect would be held and tortured or killed. This was hard for UNTAC to detect or even suspect. T-90 targeted opposition party members.[22]

Another former A-Team member explained that A-90 members worked using information gleaned from civilian informants in T-30. When individuals were identified by T-30 as suspects, A-90 would reportedly be responsible for intimidating, detaining or, in some cases, killing them. Many of those who worked for A-90 came from local and district police. [23]

A police document obtained by UNTAC from Tbong Khmum district in Kampong Cham province spoke of the need “to build a reaction force of one person per village” to identify and destroy “targets.”[24] A separate document from Kampong Cham showed that 20 SOC security forces personnel were employed in forming reaction forces in a single district.[25]

A senior SOC operative who admitted being involved in planning killings of opposition activists and participating in meetings of senior officials explained:

The CPP was afraid they would lose the 1993 election, so Sin Song and Sin Sen, [Minister of National Security and head of the national police, respectively] who were responsible for internal security, worked with generals from the police and army to create new structures. A-90 was the hidden force of the police. It was set up to monitor and control the overall situation in Phnom Penh and the country. It was in charge of seeking political movements and opponents. It had staff in charge of researching security matters, both normal and political. A-92 was the hidden forces under the control of the [Ministry of Interior]. A-90 and A-92 could kill, arrest secretly, and kidnap. They were also expected to generate revenue. Every police unit had to provide backup – financially, materially, equipment, etc. When Mok Chito [senior police officer] or my unit discovered something or a target we first had to make a report to our superiors. They take the decision to kill. Mok Chito was involved in lots of killings. Sok Phal was in charge of internal security, while Luor Ramin was responsible for foreigners. A-teams reported to Sok Phal, who reported to Sin Sen. Sometimes they went directly to Sin Sen.[26]

One former A-Team member from Kampong Cham province admitted involvement in many killings, but refused to provide details. He said that A-Teams were responsible for many of the attacks on activists from Funcinpec and the Buddhist Liberal Democratic Party during the UNTAC period:

When the A-Teams arrested someone, people were held in secret places of detention such as safe houses, cages, pagodas, etc. Every time someone was killed a report was sent to superiors. All reached Sin Sen.[27]

One of the consequences of impunity in Cambodia is that because those responsible for abuses were not held publicly accountable, Cambodians, foreign diplomats and journalists alike typically do not know the backgrounds of abusive individuals when they are later promoted or reemerge in official positions. For instance, while Cambodians over a certain age will all know the name of Sin Sen, younger Cambodians and most foreigners have no idea how powerful and widely feared he was in the late 1980s and early 1990s. During UNTAC, Sin Sen was the deputy minister of national security [the de facto national police chief, as no one held that title], a senior member of the CPP, and a representative of the SOC on the Supreme National Council, the body in which all four Cambodian parties were represented and in which Cambodian sovereignty had been placed during UNTAC. Sin Sen has been described by many former A-Team members and present and former security personnel as the architect of the A-Teams and the political violence carried out by the SOC during UNTAC. He was arrested and imprisoned for his alleged role in a failed 1994 coup attempt by CPP elements against co-prime ministers Prince Ranariddh and Hun Sen. He was later pardoned by King Sihanouk as part of a political deal between Funcinpec and the CPP.

Other members of the covert groups are also noteworthy. According to a Ministry of Interior source, the Ministry of Interior’s “Defense of Political Security 1, 2 and 3 Directorates” [codenamed S21, S22 and S23], responsible for covert action against opposition political parties, political intelligence, and counter intelligence, respectively, were renamed and moved to the Ministry of National Security after its creation in 1991. You Sin Long was put in charge of S21. Sok Phal took charge of S22. Luor Ramin ran S23. According to the covert provincial A-Team member:

For the A-Teams in Phnom Penh under Sin Sen were Sok Phal and Luor Ramin. Mok Chito was one of the leaders of the A-Teams in Phnom Penh. Heng Pov worked with Mok Chito. Mok Chito was responsible for kidnapping, while Heng Pov was responsible for selling drugs. Heng Pov planted drugs on people to extract money.[28]

Sok Phal was in charge of the information department at the Ministry of Interior during UNTAC. The information department was, and continues to be, the ministry’s intelligence unit, responsible for spying on and keeping information about Cambodians. Another leading A-Team member explained that:

Sok Phal was in charge of the information department at the MOI. Though he worked for Sin Sen, he also reported directly to Hun Sen during UNTAC. The chain of command during UNTAC was Hun Sen to Sok Phal.[29]

During UNTAC, Luor Ramin was in charge of the Counter-Terrorism Directorate of the Ministry of National Security. According to an UNTAC report, “This body had previously functioned as a political special branch of the security apparatus, responsible for the detection, arrest and interrogation of political suspects.”[30] In a June 1992 interview, Thou Thon, a long-time friend of Luor Ramin and the former administrator of K-2 [the biggest refugee camp along the Thai border], said that Luor Ramin admitted to having arrested many of Thou Thon’s fellow opposition members. He “offered the explanation that he had only been following orders from his superior, Sin Sen [currently a vice-minister of National Security and a member of the Supreme National Council].”[31]

In the document “Building up A-92 Forces,” a section entitled “Management of Command Leadership and Liaison Systems” named the leaders of A-92. It said, “A-92 forces are situated within the overall command of the Security Command of the Ministry of National Security [a line is apparently missing]:

1. Brigadier General Tes Chhoy

2. Brigadier General Chan Ien

3. Sub-Colonel Luor Ramin.”[32]

A-Teams appear to have been dissolved as coherent units amid a reorganization of security personnel following the July 1994 coup attempt, when Hun Sen demanded the ability to appoint a new national police chief [he appointed Hok Lundy and soon consolidated his control of the police at the expense of the Chea Sim and Sar Kheng faction of the CPP]. Members of the security forces interviewed for this report say key officers were reintegrated into units such as the Land Border Police, Interior Ministry Bodyguards, and Intervention Police. Others were redeployed to the Gendarmerie and the Second Prime Minister’s Bodyguard Unit in late 1994.[33]

Reintegrating A-Team personnel into formal units of the police and armed forces did not end the practice of covert activity against political and other opponents. Today, such groups operate within the police. According to former police commanders, they are divided into what are known as “kamlang l’a” or “Good Forces,” principally meaning informants, and “kamlang samngat,” or “Secret Forces.” The existence of these forces and other such groups under the command of senior officials has been reported to Human Rights Watch by sources in the Judicial Police Department at the Ministry of Interior, the Anti-Terrorism Department at the Ministry of Interior, Police Intervention Unit at the Ministry of Interior, in several departments of the Phnom Penh Municipal Police, in the prime minister’s Bodyguard Unit, the Gendarmerie, the Military Intelligence and Research Department, and at the highest levels of the National Police. Responsibility for operations rests wholly with commanders and secrecy means that no member is likely to know more than a handful of others.[34]

No one has ever been held accountable for any of the abuses reported above by UNTAC. Worse, all of the people named above were promoted after UNTAC was dissolved.

- Tes Chhoy later became police commissioner of Kampong Speu province. Chan Ien was later promoted to major general and made chief of the Central Department of Land Borders in the Ministry of Interior.

- Luor Ramin was placed in charge of the Immigration Department at the Ministry of Interior. He was later promoted to head the Anti-Drug Department of the National Police.

- You Sin Long became deputy director of the National Police and is now a general in command of the National Authority for Combating Drugs.[35]

- Mok Chito is now a three-star general in charge of the criminal department of the Ministry of Interior. In this position he reports to national commissioner of police, Neth Savouen, and oversees the criminal, economic and anti-human trafficking police. “He is the ultimate fox in the chicken coop,” said a US diplomat.[36] The United Nations and nongovernmental organizations have documented the involvement of Mok Chito in kidnapping, extortion, and killings over many years.

- Heng Pov later became the national anti-narcotics chief, undersecretary of state at the ministry of interior, chief of police in Phnom Penh, and an advisor on security to Hun Sen.[37] During this period he was implicated in a large number of human rights abuses. He is currently serving more than 90 years in prison after being convicted in 2007 on charges of murder, kidnapping, and extortion, although these crimes were tolerated until he passed information to foreigners accusing Hun Sen of profiting from drug trafficking and responsibility for human rights abuses.[38]

Among all the A-Team leaders, perhaps the most successful has been Sok Phal. Aware of his role in the A-Teams, after the 1993 election Funcinpec officials wanted him removed, but were blocked by the CPP. After the formation of the coalition government in 1993, Sok Phal stayed out of the limelight in his position as the head of the Ministry of Interior’s Information Department. After the departure of UNTAC, few foreigners knew of Sok Phal’s background. In 1997 the US Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) found out. The FBI was sent to Cambodia to investigate the March 30, 1997, grenade attack on a rally led by opposition leader Sam Rainsy. Sok Phal was part of the government investigation committee formed after the attack. It was formally led by Teng Savong, a senior police official.[39] According to Tom Nicoletti, the lead investigator for the FBI:

I had to chew out Sok Phal at a meeting. He was intimidating witnesses in front of all of us. I told him to leave and told Teng Savong not to bring him back. But Savong said this guy was from intelligence and he couldn’t control him.[40]

Not only has Sok Phal never been investigated for his role in human rights abuses, he has been favored by Hun Sen and the CPP. In or at least by 2004, Sok Phal was promoted from his post as chief of the General Information Department to that of chief of the Central Security Directorate, which oversees the General Information Department. By 2005 he was again promoted, this time to Deputy National Police Commissioner, in which capacity he oversees the Central Security Directorate. Sok Phal is currently a three-star general and a member of the CPP Central Committee.[41]

S-91 and Chhoeu Khmao, 1992-94

The Vietnamese government in 1979 established a military intelligence unit in the northwest region of Cambodia known until 1990 as "T-6." According to sources familiar with the unit, it was responsible for the arrest and interrogation, and often torture of persons suspected of belonging to the Khmer Rouge or resistance groups. These interrogations were conducted primarily at a villa in Battambang provincial town that served as its headquarters and prison; the villa was also known as "T-6." With the departure of Vietnamese armed forces from Cambodia in 1989-1990, the unit was renamed "S-91." S-91 appears to refer to “santisoke,” or "security," and 1991 refers to the year the organization was turned over to Cambodian leadership and renamed.[42]

In the early 1990’s, over 50 Cambodian soldiers were employed with S-91 as guards, interrogators, executioners, and investigators. Following UNTAC-run elections in 1993, the unit changed names once again, this time to "B-2" for “deuxième bureau,” the French designation of military intelligence. The leadership appears to have remained fairly constant throughout the unit's history, and there is little doubt that they were highly connected within the political structures of the CPP.

The military intelligence establishment included two collaborating organizations. The one known as S-91 or B-2 was directly connected with the Ministry of National Defense. General Toan Saveth, an officer of the Ministry of National Defense's intelligence bureau in charge of Battambang, Banteay Meanchey and Siem Reap provinces, was one leader. Directly under him was General Phal Preunh, said to be responsible for operations in Battambang. UNTAC investigations described Toan Saveth as the leader of the S-91 group. Phal Preunh, who had lost his forearms and one eye, was identified by UNTAC as the person in charge of conducting investigations and executions of those detained by S-91. In addition to his activities at the T-6 compound, he also ran his own detention center in a villa located near Wat Ta Mim near Battambang town.

The second branch of the military intelligence establishment included staff assigned to the Fifth Military Region, comprising Battambang, Pursat and Banteay Meanchey provinces. General Toat Theuan, a deputy chief of staff of the Fifth Military Region, was the overall commander of this group and has been implicated in its previous depredations; other notable figures included Col. Yon Youm, commander of the Fifth Military Region Special Intelligence Battalion, and one of Yon Youm’s deputies named Tep Samrith. Tep Samrith [sometimes called "Lorn"] additionally functioned as the aide de camp of Toan Saveth, and according to UNTAC investigators, was responsible for the arrest and interrogation of S-91's prisoners.

Every one of the above-named superior officers was the subject of extensive UNTAC investigations in 1992 and 1993 that revealed literally dozens of murders, abductions and acts of extortion. Every one also appeared to have received a significant promotion in rank since that time.

The Special Intelligence Battalion included several hundred members in Battambang province. It was divided into at least three units, among them Ko-1, Ko-2 and Ko-3. Ko-1 was based in Tuol Po village, Sangke district, Battambang. Its assignment was to execute persons sent "by the higher echelons" from Battambang. Until the end of April 1994, the unit was commanded by Lt. Col. Kem Vorn and his two deputies, Sith Som and Nip Kosal, the latter of whom was reportedly killed by the Khmer Rouge in March 1994.

The second sub-unit of the Special Intelligence Battalion, Ko-2, was under the command of Lt. Col. Sou Chan Nary, and his deputies Koy Vorn and Kchang Bun Thoeun. Initially sent to protect fishing communities in the Tonle Sap area from the Khmer Rouge, they appear to have usurped any Khmer Rouge "taxation" and demanded exorbitant protection fees from local traders and fishermen who wished to work their concessions and sell their catch to Battambang. Sou Chan Nary and Kem Vorn answered to Yon Youm; all three came from Thmei village in Banan district of Battambang, and were thought to be related.

The third sub-unit was assigned to the Poipet area of Banteay Meanchey province, where UNTAC had discovered and closed unreported lock-ups during the peacekeeping period.

UNTAC documented large numbers of abductions and extrajudicial executions attributed to this group. The first documented killing was of a man named Dam, who was arrested in July 1992 on the accusation that he had stolen a car. In July or August 1992, Dam was placed in a Soviet-type ambulance and taken by Phal Preunh, and a number of lower-ranking S-91 officers to Kampong Preang commune, Sangke district. He was wearing shorts with his hands tied behind his back. There is evidence that Phal shot Dam with an AK-47 assault rifle on Toan Saveth's order. Dam's body was not recovered.

Also in July 1992, an unidentified man was shot dead at point-blank range in Thmei village, Kampong Prieng commune, Sangke district. According to investigators, Phal Preunh and Von Cheuon, a soldier under Preunh's command, had taken the victim from the Fifth Military Region headquarters. Von Cheuon executed him on orders from Phal Preunh for supposedly being a motorcycle thief. The corpse had been mutilated.

The next incident was precipitated by UNTAC’s discovery of the T-6 prison, where over 50 prisoners were estimated to have been detained since January 1992. On August 23, 1993, UNTAC entered the prison, but found all the prisoners had been released or removed hours earlier. Although the UNTAC visit took the prison guards by surprise, Toan Saveth was apparently informed in advance by Toat Theuan, then deputy chief of staff of the Fifth Military Region and a former head of T-6 himself. Toan Saveth then reportedly ordered the killing of two T-6 prisoners, Chhon Chantha [also referred to as Suan Chhanta], accused of being a resistance fighter and found with Funcinpec papers on him when he was arrested earlier that August, and Rith, accused of being a Khmer Rouge cadre, who had been arrested in July 1992. These men allegedly were taken to the Fifth Military Region headquarters in Treng and killed. As many as 10 other prisoners who had been held in T-6 between June and August 1992 were released after paying substantial ransoms in gold or money.

Hun Suorn, a soldier, was killed on the night of April 6, 1992, by two bullets in the chest. He had been abducted that night in Battambang town by four other soldiers with whom he had been playing cards and from whom he had won a considerable amount of money. The soldiers took him to the house of an S-91 officer [believed to be Toat Theuan] located directly opposite another building in Battambang town used by S-91 for detentions. From there he was taken by truck to a local restaurant, and then to the outskirts of town near Wat Kor commune, where he was shot. His body showed signs of torture, and his arms had been bound.

UNTAC police also suspected S-91 involvement in at least one of the dozens of attacks on the royalist Funcinpec party offices prior to the election, in this case an attack on the Sangke district Funcinpec office on March 31, 1993, that killed three people. The strategy of recruiting thugs became a hallmark of S-91 operations as well. The UNTAC raid on T-6 in August 1992 caused a temporary pause in the group's activities, but by September Toan Saveth was reportedly reassembling the group and intimidating former members he suspected might betray it. The group began recruiting notorious robbers, who then continued their banditry under the protection of the unit. But some of these recruits also became S-91's newest victims. The rationale for S-91's activities shifted from controlling political opponents to "using thieves to catch thieves," as Toan Saveth himself explained, echoing Sin Song's explanation for the "reaction forces."

By July 1993 at the latest, S-91 had put the T-6 detention facility back to use. On the morning of July 19, 1993, two S-91 members, Chheang Sarorn, known as Rorn, and Pou Virak, known as Korp or Kaep, visited the houses of Kom Sot and another man and informed them that it had been reported that the two had stolen and pawned a motorcycle, which both men denied. That night, the two were abducted at gunpoint by several S-91 members, including Phouek, Leang Kim Hak, also known as Map, and Sua Seun. They were taken to the T-6 villa where they were undressed and shackled. Tep Samrith interrogated each one about the theft while Phouek beat them, including hitting them on the neck with a B-40 rocket launcher. At midnight they were blindfolded and taken on motorcycles by Map, Phouek, and Sua Seun to Anlong Vil village near Route 5 in Sangke district, where Seun killed Kom Sot by shooting him in the head. The other man escaped.

The next incident occurred two weeks later, when the bodies of Suon Heang, Touch Taylin and Sun Sareuat showed up, along with another severely injured man, close to Anlong Vil village in Sangke district, and two more corpses were found at the same place in Wat Kor commune where Hun Sourn had been killed in April. All the victims had been blindfolded with strips of the same blue-checked scarf, and had been shot in the head late on the night of August 3, 1993. Three of the victims had been invited to have dinner at Phal Preunh's home in order to give biographical information and enlist in S-91. Following the meal, they were abducted by subordinates of Preunh, beaten, and put into a type of jeep. The fourth victim was arrested that night by several S-91 members, including Phouek and Ung Sovann, at Kapko Thmei village in Battambang town. A note had been left at both places with the sign of a skull and crossbones and the words, "The Activity of the Robber Groups Must be Destroyed - T.B. Kh.M." In early August, two more male corpses were found close to the same spot in Anlong Vil, again shot in the head with a message nearby with the same words and skull and crossbones.

These cases were brought to the attention of the transitional government's Ministry of National Security and the Supreme National Council by UNTAC personnel prior to UNTAC’s departure. No action was taken.

The death squads continued after the new government was formed in September 1993. In March 1994, Human Rights Watch began to investigate reports of continuing S-91 extrajudicial executions at Chhoeu Khmao. Ultimately, at least 35 other killings committed between June 1993 and January 1994 in that location became known to the UN Centre for Human Rights, which was established in Phnom Penh to promote and monitor human rights in the country after UNTAC’s departure. The victims of S-91 were usually moderately prosperous traders, businessmen, travelers or passersby who were in the wrong place at the wrong time, as well as some suspected Khmer Rouge members or sympathizers. Many of the victims appear to have been spotted in markets en route to or from the Thai border by the military intelligence network and marked as likely prospects for extortion. Ambushes or abductions were then arranged. Arrests often took place at night in markets, where merchants and petty traders rented stretchers and slept outside on the pavement, or on the road under the guise of bandit attacks on complicit taxi drivers.

Victims were typically held overnight at one of the secret prisons in Battambang, or sometimes longer if it appeared their families could be extorted for ransom. They were systematically robbed of their possessions, and if suspected of Khmer Rouge sympathies, interrogated by Phal Preunh himself. As the use of his villa near Wat Ta Mim became more widely known as S-91's detention facility, Phal Preunh transferred his operation to the house formerly known as the T-6 facility, located on the same side of the river on a street running between Route 5 and the river bank. A new corrugated metal fence went up with a small sentry box, and the refurbished headquarters swiftly became notorious as "Uncle Preunh's place."

From the Battambang detention houses, victims who were not immediately executed were transferred to locations near Chhoeu Khmao. Chhoeu Khmao is the name of an abandoned village some 45 kilometers east of Battambang, on the left bank of the Sangke river, in Prey Chas commune, Ek Phnom district. The area is a vast flood plain, with small villages that subsist on fishing when the rainy season submerges the land. A small temple was the only inhabited site left at Chhoeu Khmao. On the opposite bank is Tuol Po village, which was the site of a small garrison camp for one of the sub-units of the Special Intelligence Battalion of the Fifth Military Region. There was no prison as such at Chhoeu Khmao or the Tuol Po garrison.

Until early 1994, prisoners were sent from Battambang town with specific orders that they be executed as "Khmer Rouge enemies." The members of Ko-1 usually carried out executions in the early hours of the morning or immediately after the victim's arrival. Soldiers would place the victims, blindfolded with arms tied in back at the elbows, onto boats to one of several execution places a few kilometers downstream from Chhoeu Khmao and shoot them point-blank in the head. Bodies would be disposed of in the river, where terrified fishermen would sometimes find them. Local people estimated that as many as 70 people may have been killed in the second half of 1993. The bodies of some of those executed at Chhoeu Khmao were mutilated as well.

At least seven detainees managed to escape in 1993, some after paying substantial bribes to their captors. News of these escapes from Chhoeu Khmao seems to have led to a change in policy there. Instead of executing 16 detainees remaining at the end of 1993, the Ko-1 unit decided to hold them as quiet captives, releasing some conditional on a promise of silence, and forcibly incorporating others into the Ko-1 unit on pain of death.

Toan Saveth reportedly issued an order to the military intelligence group in early 1994 to cease executions at Chhoeu Khmao, apparently out of fear of being exposed, and there is no evidence of executions at that location after January 1994. In early April 1994 a recent Ko-1 recruit was spared execution by Yon Youm for a minor offense on the intervention of another officer. Abductions, however, continued.

Although the group's crimes were very widely known among the population of Battambang, residents there, including very high-ranking provincial military and police officials, were extremely frightened and reluctant to discuss them.

When the extent of the atrocities committed at Chhoeu Khmao was discovered in June 1994, the UN Centre for Human Rights, Human Rights Watch, and Amnesty International communicated confidentially to leaders of the government, urging them to secure the safe release of the remaining detainees, investigate the matter, and prosecute those responsible. That month, the government's military prosecutor, General Sao Sok, conducted an investigation that substantially corroborated the findings above. He recommended that the alleged perpetrators be produced for interrogation. These recommendations were transmitted to the Ministry of National Defense, which issued written instructions to the Royal Cambodian Armed Forces General Staff to implement the military prosecutor's recommendations.

These instructions were ignored. Instead, the then co-prime ministers, Hun Sen and Ranariddh, appointed a special commission to conduct its own investigation. In a report dated July 22, 1994, the commission concluded that no such abuses had taken place. Once the July 22 report began to circulate, the findings of previous investigations, including the military prosecutor's, found their way to the international and local media. In the wake of public outrage, the prime ministers ordered the special commission to resume the investigations.

The commission, composed mainly of CPP members, included the Battambang deputy chief of police and a deputy commander of the Fifth Military Region. Its questioning of witnesses was carried out in the company of large and intimidating entourages of soldiers and journalists. Although the government invited local human rights monitors to observe these investigations, Cambodian human rights groups declined the invitation, saying that they considered the prior investigations to be neutral and adequate.

On December 9, 1994, after its fourth investigative mission to Battambang, the Commission released a report on its findings. It concluded that S-91 was responsible for many arrests. These arrests were, according to the Commission, initially carried out to collect information of importance for the armed forces, but the purpose seemed to have transformed into extortion. The Commission further concluded that they had not found sufficient evidence to confirm the existence of secret detention centers or that executions had occurred.

Hun Sen denied the allegations in a 1995 meeting with members of the Human Rights Action Committee, an umbrella group of Cambodian human rights groups. He accused the UN human rights office in Cambodia of acting outside its mandate by investigating Chhoeu Khmao. He claimed that its report on the issue defamed the government and had damaged the image of Cambodia in the eyes of other countries.[43]

Toan Saveth later was implicated in further crimes. On July 16, 1994, he was arrested when a car containing him and two subordinates stopped less than 100 meters from a police checkpoint on Route 5, south of Battambang provincial town in Moung Russei district, and persons in the car got out and fired a 40 mm M-79 grenade launcher on the police post. Within 24 hours of his arrest, Toan Saveth had been transferred to the Tuol Sleng military prison in Phnom Penh. The news caused jubilation throughout Battambang. In the words of one resident, “It was as though one bar was removed in the prison that holds our hearts.” However, Toan Saveth was released several weeks later, because of an alleged lack of evidence, based on testimony that he was "asleep" in the car at the time of the alleged attack.[44]

On April 11, 1995, Toan Saveth was sentenced in absentia by a Battambang court to 13 years in prison. The court sent an arrest warrant to the Ministry of National Defense, where Toan Saveth was said to be working, but received no response. Toan Saveth still has not been arrested. Senior government officials and members of the armed forces have admitted that he and several other military officers believed to be responsible for the atrocities committed by S-91 continued to hold positions in the Military Intelligence and Research Department.[45]

As of 2004, sources familiar with the operations of the Military Intelligence and Research Department maintained that individuals associated with it were still involved in assassinations, kidnappings and various other crimes, including alleged narcotics trafficking and providing security for casinos along the Thai border.[46] As in the case of other senior military officers, the commanders of the department have also acquired considerable legal business interests, such as hotels, apartment buildings and road construction companies.[47]

None of those involved in S-91 crimes have ever been prosecuted for their involvement in these illegal activities.

Phal Prunh is reportedly dead. Toat Theuan was transferred to Phnom Penh after the disclosure of the Chhoeu Khmao activities. He is now a Major General at the Ministry of Defense in Phnom Penh.

Son Sann grenade attack, 1995

The Buddhist Liberal Democrat Party (BLDP) was formed by a faction of the Khmer People’s National Liberation Front (KPNLF), the main non-communist resistance force fighting the Vietnamese-installed People’s Republic of Kampuchea [later the SOC] from bases along the Thai border. The KPNLF was supported by the United States and founded by Son Sann, a former Cambodian finance minister during the Sihanouk era. Son Sann was well known to Cambodians chiefly because his name appeared on Cambodian money in the 1960s when he was finance minister. After the Paris Agreements, Son Sann, returned to Phnom Penh, from where he operated the BLDP in preparation for the UNTAC-sponsored elections in 1993.

In early 1995, then 83 years old, Son Sann attempted to have Ieng Mouly, the BLDP’s de facto number two, expelled from his seat at the National Assembly. Mouly had taken the position of information minister in the government without his party’s approval. Mouly had been a BLDP-appointed member of the Supreme National Council during UNTAC.

In response, in August 1995 Mouly’s faction held a party congress at Phnom Penh’s Olympic Stadium to expel Son Sann, have himself elected party leader, and claim the BLDP name for his faction alone. The congress received the support of the co-prime ministers. According to Mouly, Hun Sen offered to provide security and financial support:

I needed the support of Hun Sen to make a big splash. I had no money or materials. Hun Sen provided security and high-ranking representatives from his party. I couldn’t say no. To have a big impact I needed this support. I was also worried about security for the congress without Hun Sen’s support. [48]

Son Sann then decided to hold his own party congress. His faction of the BLDP requested permission from the Ministry of Interior to also hold its congress at the Olympic Stadium. The Ministry of Interior refused. Son Sann defied the government and decided to hold the congress on October 1 at his house on Street 338, near the Olympic Stadium.[49]

At the time, the government was claiming that plans by former finance minister and Funcinpec leader Sam Rainsy to start a new political party were illegal. Earlier in the year, Rainsy had been expelled from his seat in the National Assembly and from the Funcinpec party. The co-prime ministers took a similarly hard stand against Son Sann’s planned congress, calling it illegal and launching a media campaign to discourage party members and the public from attending. On the eve of the congress, government security forces blocked all the roads to Phnom Penh to keep attendance at the congress as low as possible. Those with BLDP cards were not allowed to pass.[50]

Before Son Sann held his congress, Mouly told the Phnom Penh Post that he feared violence, saying that there might be “bad elements from outside who want to...create some problems? They may throw three hand grenades and then they can accuse me, they can accuse the government.”[51]

Mouly later said that he was warned that there could be security problems:

Benny Widyono [the UN secretary-general’s representative in Cambodia], told me that if Son Sann had a congress there could be security problems. He said the Khmer Rouge or others could attack and I would get the blame. So I made a public statement that there might be a grenade attack. Before the congress I was also told by a three-star general in the police not to be nearby. [52]

Hun Sen warned in a nationally broadcast speech that if Son Sann proceeded with the party congress, either he or other organizers would be deemed “lawbreakers” and arrested, or there could be “terrorist attacks or bombings,” for which Hun Sen said Son Sann and other BLDP leaders would be held personally responsible.[53]

On September 30, the night before the congress, about 100 people were gathered outside Son Sann’s house. A motorcycle carrying two men drove by. The passenger threw a grenade and the motorcycle sped off. Twenty-eight people were wounded, including Son San’s son Son Soubert, the vice-president of the National Assembly, who had a minor shrapnel wound. There were no fatalities. Soon after, a grenade was thrown into the grounds of a nearby Buddhist temple, Wat Mohamontrei, where supporters of Son Sann from the provinces who had made their way past roadblocks were staying. This was the first incident of major political violence since UNTAC ended its mission in September 1993.

In spite of the dangers, more than 1,000 people attended the congress the next day. Soon after the US ambassador left, the French-trained gendarmerie [also known as military police in Cambodia], armed with machine guns and grenade launchers, waded into the crowd and broke up the rally. Many supporters moved into Son Sann’s compound, but the others were forced to leave.

The government promised to investigate, but there is no evidence that any investigation ever took place.

Killing of Thun Bun Ly, May 1996

On May 18, 1996, at 10.30 a.m., Thun Bun Ly, editor of Udom Kate Khmer (Khmer Ideal) left his house in Phnom Penh and took a motorcycle taxi. According to witnesses, at Street 95 two men on a motorcycle came up from behind. The passenger fired a K-59 pistol, hitting Bun Ly in three places. He died at the scene. A returned refugee, Bun Ly was 39 and left a wife and children. He was a steering committee member of the opposition Khmer Nation Party (KNP), led by Sam Rainsy.

Bun Ly’s body was taken to nearby Wat Lanka, a Buddhist temple, and laid out in traditional Khmer style. In front of a UN human rights worker, armed and uniformed soldiers arrived at Wat Lanka. One put on rubber gloves and reached into the wounds, extracting the bullets, before calmly leaving. Later that day, another man allegedly came to the temple and removed the third bullet.

Earlier on the morning of his death, Bun Ly had gone to Rainsy’s house and returned home. He called a friend and told him that he had been followed home and feared for his safety. That day, Udom Kate Khmer ran a front-page story saying that Bun Ly had been threatened by a major in the police’s anti-terror squad.[54]

In his paper, Bun Ly regularly attacked the co-prime ministers and their parties. A vigorous and inflammatory critic of Vietnamese immigration to Cambodia, in 1995 Bun Ly had been prosecuted and convicted twice for publishing articles critical of the government. He was on bail and his cases were on appeal at the time of his death. At one of his trials, he amused a packed courtroom by explaining that it was the role of the press to critique the government. “It is not my job to hold the testicles of the co-prime ministers,” he said.

Bun Ly frequently received threats and reported them to the UN and human rights groups. He told Amnesty International, “I have been threatened by soldiers and police who keep me under surveillance, and people who know me say I should stop publishing...but the newspaper is my sweat and blood. I won’t forsake it."[55]

No one has ever been arrested or prosecuted for Thun Bun Ly’s killing.

Grenade Attack on Opposition Party Rally, March 30, 1997

On Sunday, March 30, 1997, a handful of children, including Ros Kea, 12, took a ride from Wat Mohamontrey, the Buddhist temple in Phnom Penh where they lived as orphans [and which had been attacked in 1995 in the Son Sann grenade attack]. They jumped into the back of a pickup truck, taking up the offer of 5,000 riels (US$2) to participate in a rally organized by the KNP.[56]

As they waited in the early morning sun in a park across the street from the Royal Palace and the National Assembly, 200 of the real demonstrators arrived after a 10-minute march. Carrying blue banners with white lettering in Khmer and English containing slogans like “Down with the Communist Judiciary” and “Stop the Theft of State Assets,” the last photo of the group looks more like a school picture than a political rally.

Present at the rally was Sam Rainsy, the founder of the opposition Khmer Nation Party (KNP). Since the killing of an opposition journalist in May 1996, Rainsy, who had been minister of finance until his dismissal in 1994 by Co-Prime Ministers Prince Ranariddh and Hun Sen for demanding the acceleration of reforms, had begun staging regular demonstrations over labor rights, corruption, illegal logging, the environment, and the lack of political pluralism. The creation of Cambodia’s first independent labor unions in January 1997 had led to many strikes and demonstrations. Rainsy seemed to be at all of them, and each was met with a heavy police presence that raised tensions.

The government controlled the army, police, the courts, and the media, yet seemed frightened by street protests. Contrary to the new constitution, which guarantees freedom of expression and peaceful assembly as well as Cambodia’s compliance with all of its obligations under international law, the government declared all the rallies illegal.

The UN human rights office in Phnom Penh considered the rally on March 30 to be so innocuous that for the first time it sent no one to monitor it. Yet this demonstration made history for two reasons: it was the first post-UNTAC demonstration formally approved by the Ministry of Interior, and it ended in grenades and carnage. When the grenade-throwing was over, at least 16 people lay dead and dying. More than 150 were injured. Ros Kea was among those killed.

The main target, Sam Rainsy, survived the attack. After the first grenade exploded, Rainsy’s bodyguard, Han Muny, threw himself on top of his leader. He took the full force of a subsequent grenade and died at the scene. Rainsy escaped with a minor leg injury. Body parts of other victims littered the area, and the grisly photos of the dying against the backdrop of the Royal Palace landed the story on the front pages of newspapers around the world and as the lead story on CNN. One photo shows a teenage girl with her legs blown off trying to stand up. She stares at the camera in shock and incomprehension, her long black hair matted with blood, surrounded by dead bodies. She soon died. Cambodian police present not only did not help the injured, but some tried to block bystanders from assisting victims.

The attack took place at a time of extreme political tension. The coalition government of the royalist Funcinpec party and Hun Sen’s CPP was unraveling after armed clashes in Battambang province the previous month. Rainsy’s KNP was seen as a threat in national elections scheduled for the following year. For more than a year, he and his party members had been the subject of attacks and threats from CPP officials and agents.

The attack was well-planned. Members of the personal bodyguard unit of Hun Sen, Brigade 70, were deployed in full riot gear at the rally. The rally was the first time Brigade 70 has been deployed at a demonstration. The elite military unit not only failed to prevent the attack, but was seen by numerous witnesses opening up its lines to allow the grenade-throwers to escape through a CPP-controlled area of Phnom Penh, and then threatened to shoot people trying to pursue the attackers. T he police, which had previously maintained a high-profile presence at opposition demonstrations in an effort to discourage public participation, had an unusually low profile on this day, grouped around the corner from the park. Other police units, however, were in a nearby police station in full riot gear on high alert.

In a speech on the afternoon of the attack, Hun Sen suggested that the leadership of the KNP might have organized the attack to put the blame on the CPP. Instead of launching a serious investigation, he called for the arrest of Sam Rainsy. However, facing resistance in the CPP and an onslaught of domestic and international outrage, he dropped the plan.

The FBI undertook an investigation into the grenade attack because a US citizen, Ron Abney, was among those wounded. The FBI concluded that Cambodian government officials were responsible for the attack, but the chief investigator, Thomas Nicoletti, was ordered out of the country by US officials before he could complete his investigation.[57]

On June 29, 1997, the Washington Post reported:

In a classified report that could pose some awkward problems for US policymakers, the FBI tentatively has pinned responsibility for the blasts, and the subsequent interference, on personal bodyguard forces employed by Hun Sen, one of Cambodia’s two prime ministers, according to four US government sources familiar with its contents. The preliminary report was based on a two-month investigation by FBI agents sent here under a federal law giving the bureau jurisdiction whenever a US citizen is injured by terrorism.... The bureau says its investigation is continuing, but the agents involved reportedly have complained that additional informants here are too frightened to come forward.[58]

While the investigation uncovered a great deal of evidence, as did investigations by the UN human rights office, the Cambodian authorities failed to cooperate. On January 9, 2000, CIA director George Tenet said the United States would never forget an act of terrorism against its citizens and would bring those responsible to justice “no matter how long it takes.” Yet the FBI investigation was abandoned and formally closed in 2005.

Rather than identifying and prosecuting the people who ordered and carried out the grenade attack, the Cambodian government has since handed out high-level promotions to two people linked by the FBI to the attack. The commander of Brigade 70 at the time, Huy Piseth, who admitted ordering the deployment of Brigade 70 forces to the scene that day, is now a lieutenant general and undersecretary of state at the Ministry of Defense. Hing Bun Heang, deputy commander of Brigade 70 at the time, was promoted to deputy commander of the Royal Cambodian Armed Forces (RCAF) in January 2009. In a June 1997 interview with the Phnom Penh Post, Bun Heang threatened to kill journalists who alleged that Hun Sen’s bodyguards were involved. “Why do they accuse us without any basic evidence? We are innocent people, we were not involved in that attack. Publish this: Tell them that I want to kill them … publish it, say that I, chief of the bodyguards, have said this. I want to kill … I am so angry.” [59]

The March 30 grenade attack has cast a long shadow over Cambodian politics that remains today. The attack appears to have been intended to destroy the political opposition in Cambodia.It signaled that pluralism would be opposed by powerful people and would come at a deadly price.

The attack on Sam Rainsy and his supporters remains an open wound in Cambodia, but neither the government nor Cambodia's donors are doing anything to hold those responsible to account. The clear involvement of Hun Sen’s bodyguard unit in the attack and the perpetual failure to address this crime has led some to refer to March 30 as “Impunity Day” in Cambodia.

The July 1997 Coup and Post-Coup Killings, 1997-1998

On July 5, 1997, Second Prime Minister Hun Sen launched what the United Nations described as a coup d’état against First Prime Minister Ranariddh and his Funcinpec party. According to the Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Human Rights in Cambodia, Thomas Hammarberg:

I strongly condemn the violent coup d'état of 5-6 July which has displaced the lawfully-elected government of Cambodia. The overthrow of First Prime Minister Prince Norodom Ranariddh by armed force violates the Cambodian Constitution and international law and overturns the will of the Cambodian people in the 1993 UN-sponsored election. In that poll approximately 90 percent of eligible voters courageously turned out in the face of widespread intimidation and violence to choose a new government.

As the Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Human Rights in Cambodia, I am particularly concerned about the large loss of life and injury in the current violence. The use of mortars, artillery and other heavy weapons in urban areas displayed a callous disregard for the lives and safety of the civilian population.