Sex Workers at Risk

Condoms as Evidence of Prostitution in Four US Cities

Summary

If I took a lot of condoms, they would arrest me. If I took a few or only one, I would run out and not be able to protect myself. How many times have I had unprotected sex because I was afraid of carrying condoms? Many times. –Anastasia L., sex worker, New York City, March 22, 2012

Felicia C. is a sex worker in the Columbia Heights neighborhood of Washington, DC. When Human Rights Watch met Felicia, it was 2 a.m. on a cold and windy morning. Felicia ran over to an outreach van to get a warm cup of coffee from the volunteers. She took the “bad date” sheet that warns of recent attacks on sex workers, and was offered some condoms. She would not take more than two. When asked why, she said she was afraid to be harassed by the police. She said that a month earlier, she had been stopped and questioned by police and told to throw her condoms into the garbage. She said she’d held her ground and refused, but she didn’t want to be harassed again.

Felicia’s story is not unique. In four of the nation’s major cities—New York, Washington, DC, Los Angeles, and San Francisco—police stop, search, and arrest sex workers using condoms as evidence to support prostitution charges. For many sex workers, particularly transgender women, arrest means facing degrading treatment and abuse at the hands of the police. For immigrants, arrest for prostitution offenses can mean detention and removal from the United States. Some women told Human Rights Watch that they continued to carry condoms despite the harsh consequences. For others, fear of arrest overwhelmed their need to protect themselves from HIV, other sexually transmitted diseases and pregnancy.

Alexa L., a New York City sex worker, said, “I use condoms. I take a lot of care of myself. But I have not used them before because I was afraid of carrying them. I am very worried about my health.” Carol F., a sex worker in Los Angeles who had been arrested partly on the basis of carrying condoms, had a similar story: “After the arrest, I was always scared…There were times when I didn’t have a condom when I needed one, and I used a plastic bag.”

Prostitution—the exchange of sex for money or other consideration—is illegal in 49 states and in all of the cities addressed in this report. Law enforcement agencies in these jurisdictions are charged with enforcing laws, including those relating to prostitution. Enforcement, however, must be compatible with international human rights law and governments should ensure that police policies and practices do not conflict with equally important public health policy imperatives, including those designed to curb the HIV epidemic.

Police stops and searches for condoms are often a result of profiling, a practice of targeting individuals as suspected offenders for who they are, what they are wearing and where they are standing, rather than on the basis of any observed illegal activity. In New York, Washington, DC, and Los Angeles, many people, particularly members of the transgender community, told Human Rights Watch they were stopped and searched for condoms while walking home from school, going to the grocery store, and waiting for the bus. Vague loitering laws invite interference with the right to liberty and security of the person, permitting police to consider a wide range of behavior and other factors suspicious, including possession of condoms and being “known” as a sex worker. The anti-prostitution loitering laws in New York, California, and Washington, DC are inconsistent with human rights principles prohibiting detention or punishment based on identity or status and should be reformed or repealed.

Sex workers in New York, Washington, DC, and Los Angeles described abusive and unlawful police behavior ranging from verbal harassment to public humiliation to extortion for sex, both in and out of detention settings. Transgender women described being “defaced” by police who removed their wigs, threw them on the ground, and stepped on them. Police subjected transgender women to a constant barrage of vulgar insults, mockery, and disrespect. Most disturbing were reports in both New York and Los Angeles that some police regularly demanded sex in order to drop charges or coerced women into sex while in detention. Few of these women filed complaints, fearing further abuse and having lost faith in police to respond with fairness and integrity. Police officials in each of these cities should take action to increase accountability, restore community trust, and end an unacceptable cycle of impunity for human rights abuses against sex workers and transgender persons.

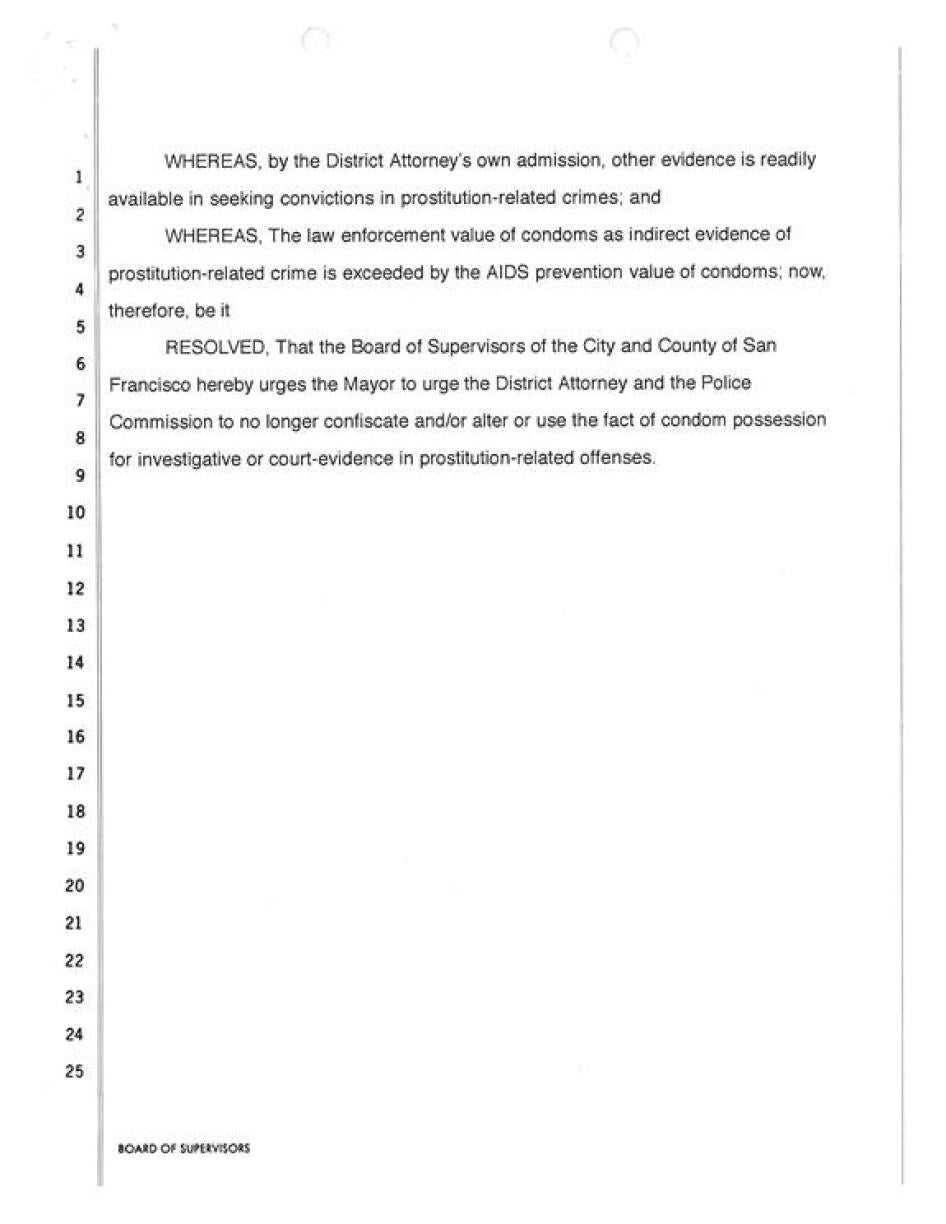

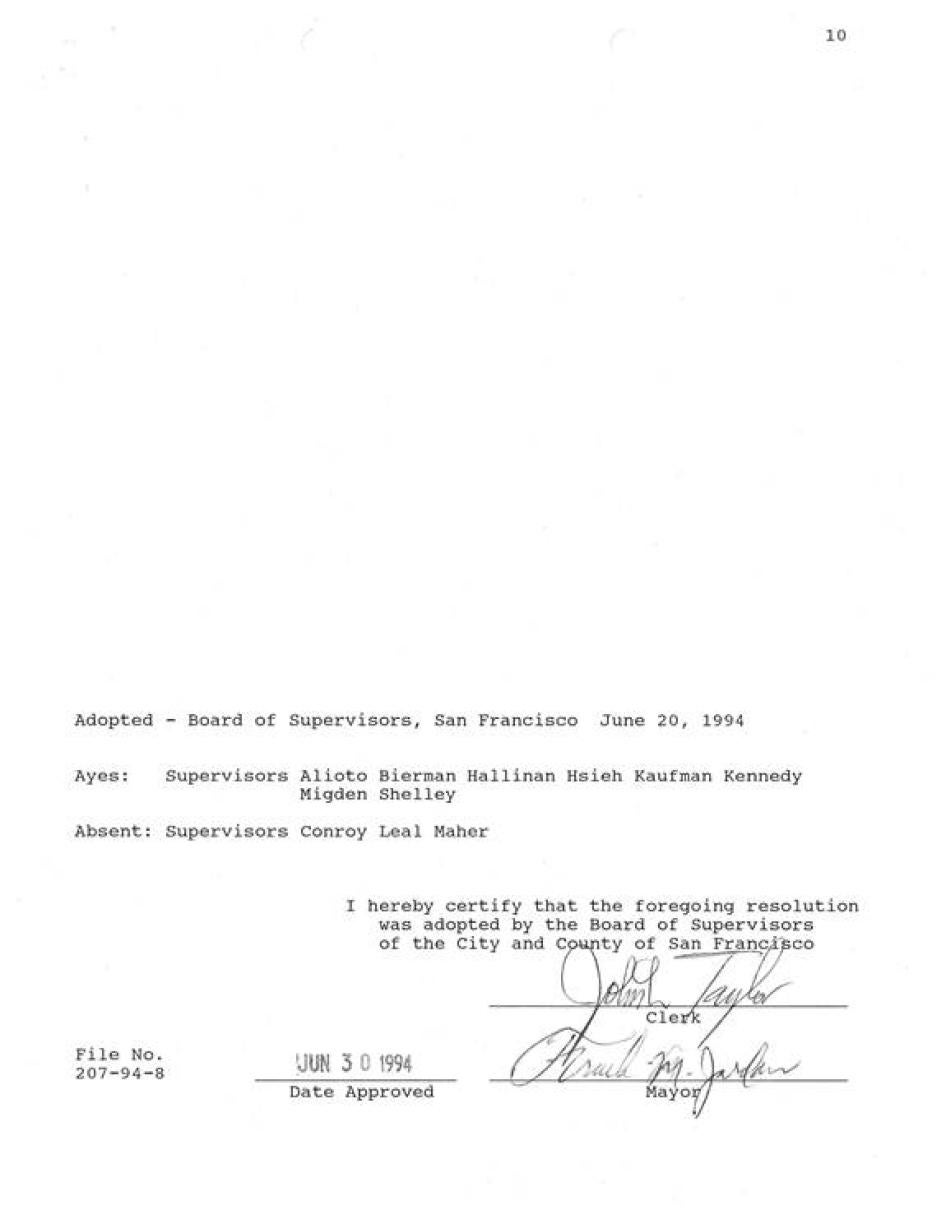

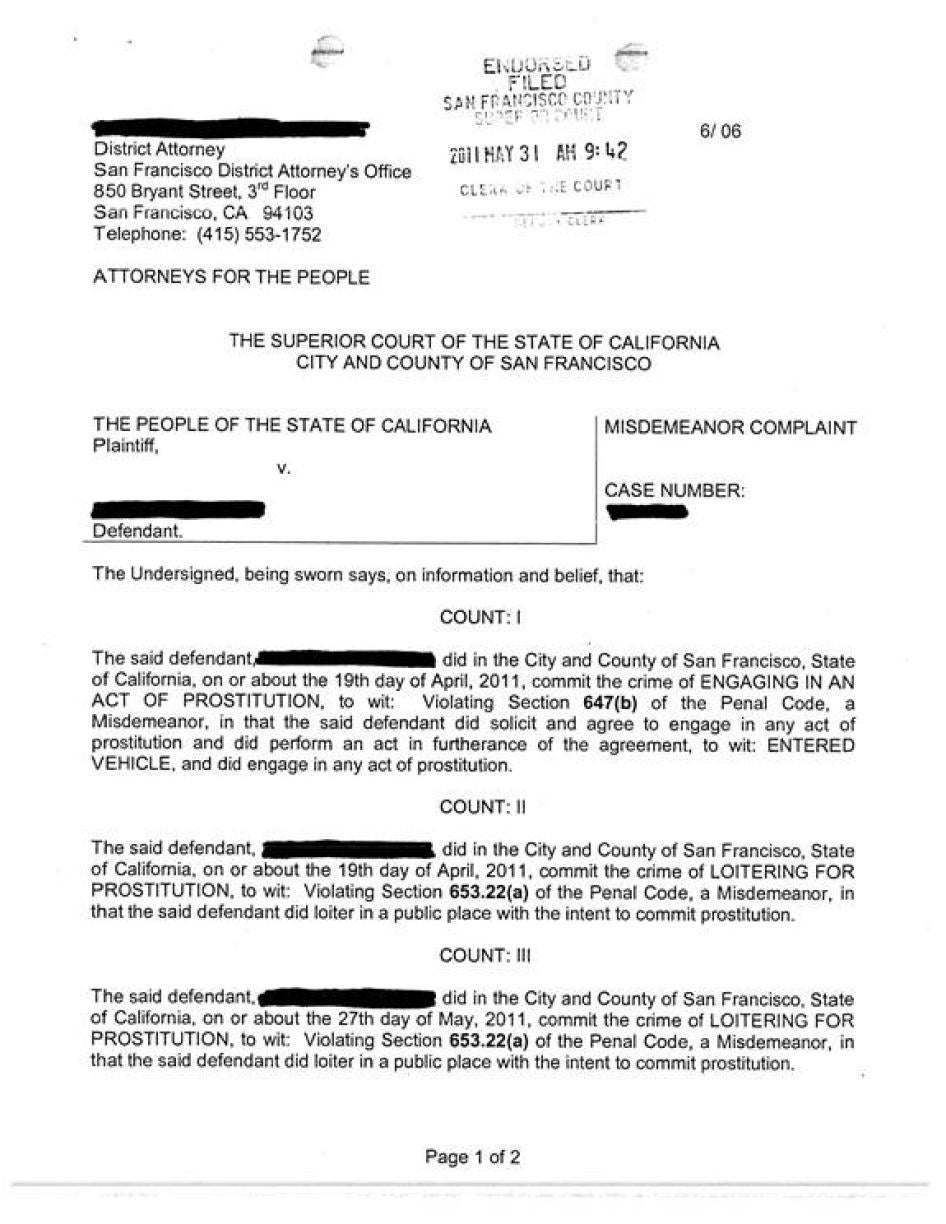

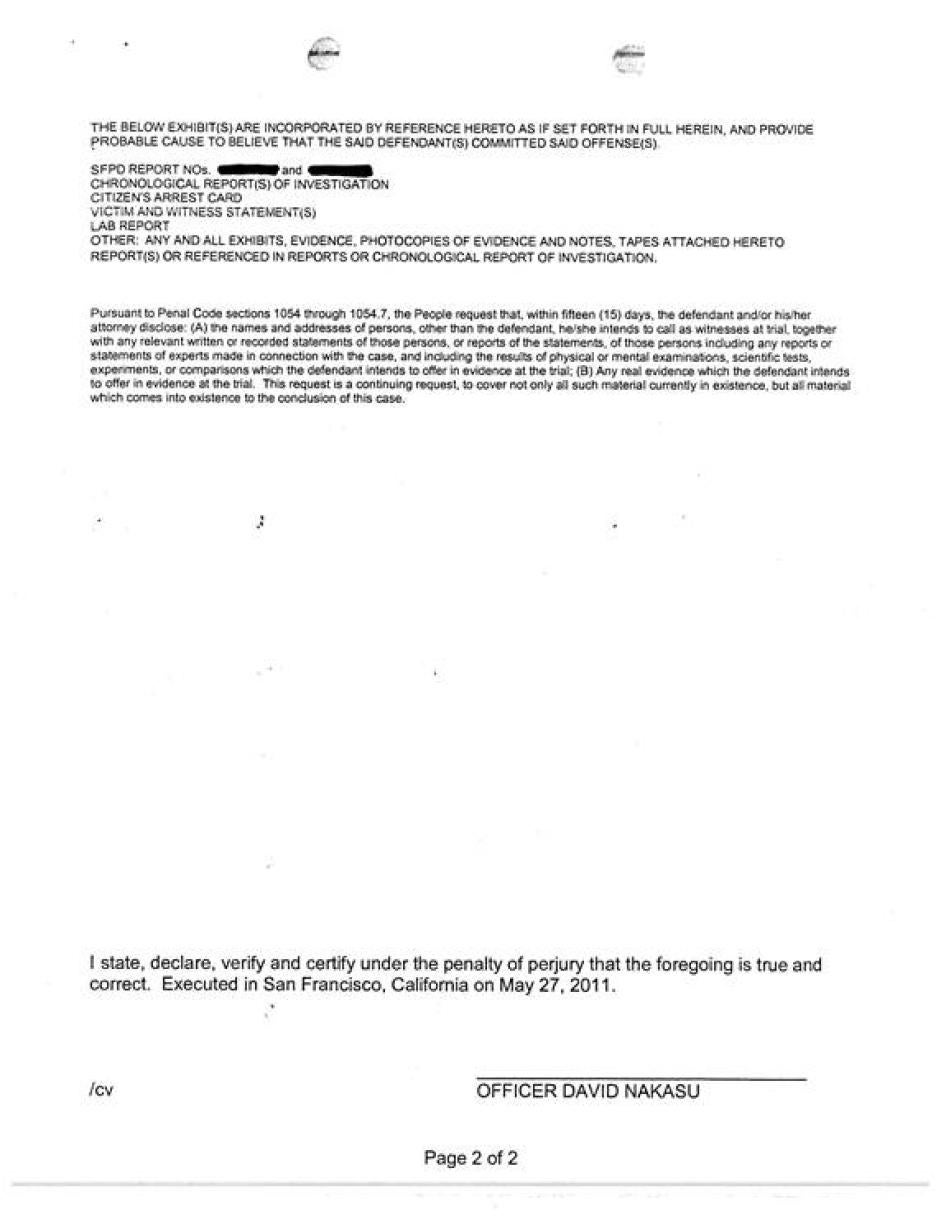

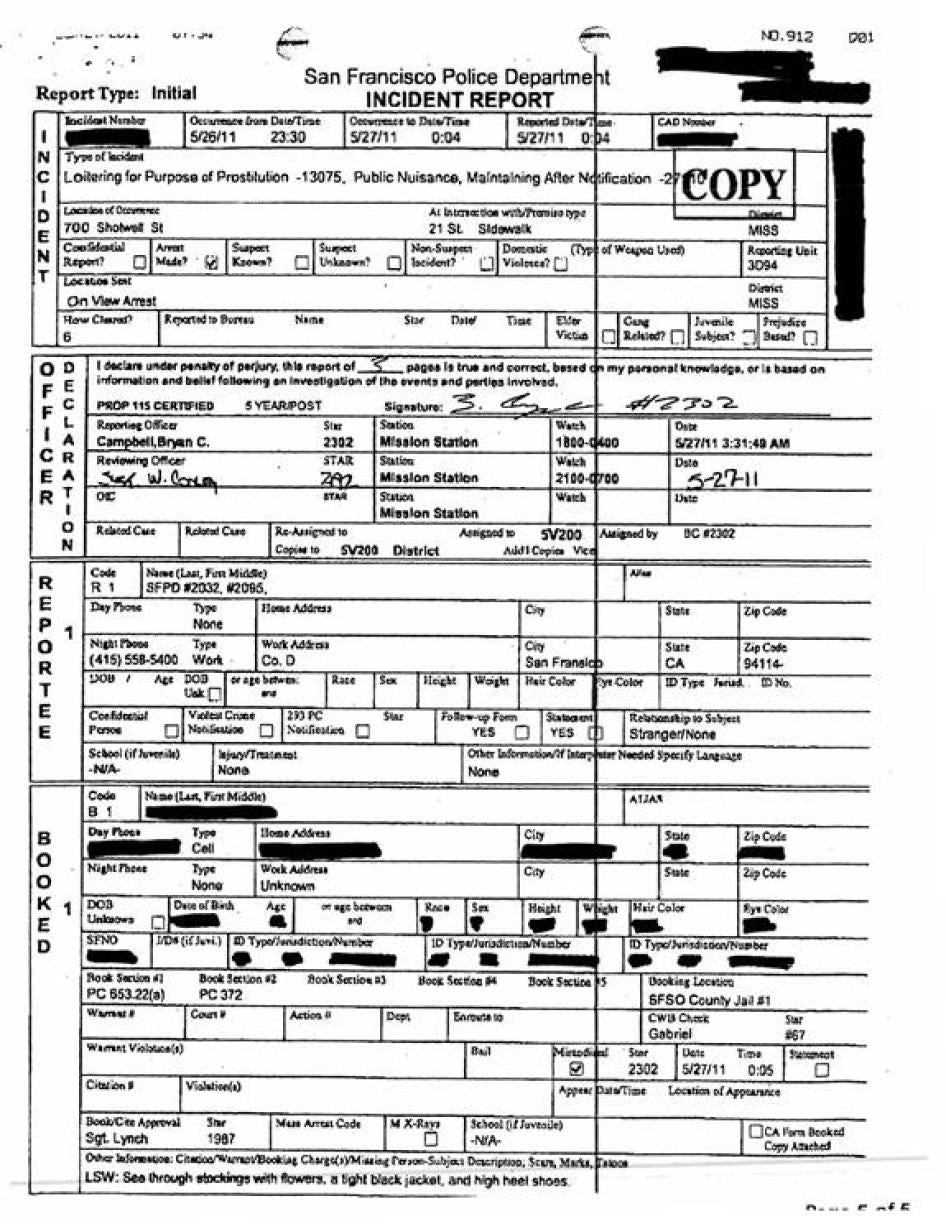

Human Rights Watch interviewed more than 300 persons for this report, which focuses on police use of condoms as evidence to enforce prostitution and sex trafficking laws, as part of an investigation into barriers to effective HIV prevention for sex workers in the four cities covered by this report. Those interviewed included nearly 200 sex workers and former sex workers as well as outreach workers, advocates, lawyers, police officers, district attorneys, and public health officials. In New York, Washington, DC, and Los Angeles our investigation focused on complaints of police using condoms as evidence while targeting sex workers on the street. In San Francisco, condoms were used as evidence for street enforcement to some extent, with police photographing rather than confiscating condoms, in what appeared to be a dubious nod to public health concerns. In San Francisco, much of the anti-prostitution enforcement using condoms as evidence targeted women working in businesses such as erotic dance clubs, massage businesses, and a nightclub with transgender clientele.

Police use of condoms as evidence of prostitution has the same effect everywhere: despite millions of dollars spent on promoting and distributing condoms as an effective method of HIV prevention, groups most at risk of infection—sex workers, transgender women, and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) youth—are afraid to carry them and therefore engage in sex without protection as a result of police harassment. Outreach workers and businesses are unable to distribute condoms freely and without fear of harassment as well.

Sex workers and transgender women are highly vulnerable to HIV infection as a result of many factors including stigma, social and physical isolation, and economic deprivation. In San Francisco one of three transgender women has HIV; in Los Angeles the Department of Health has identified HIV prevention for transgender women as an “urgent” priority. It is not surprising that those on the front lines are confused about the message city governments are sending on condom use. Maria, a sex worker in Los Angeles asked, “Why is the city giving me condoms when I can’t carry them without going to jail?” Ironically, if Maria went to jail in Los Angeles or any of the cities addressed in this report she could get a condom, as condoms are available in detention settings for prevention of HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases.

Police and prosecutors defended the use of condoms as evidence necessary to enforce prostitution and sex trafficking laws. However, the use of any type of evidence must be determined by weighing the potential harm that occurs from its use and the benefits provided. In legal systems everywhere, categories of potentially relevant evidence are excluded as a matter of public policy, with laws excluding testimony regarding a rape victim’s sexual history providing but one of many examples. Law enforcement efforts should not interfere with the right of anyone, including sex workers, to protect their health. The value of condoms for HIV and disease prevention far outweighs any utility in enforcement of anti-prostitution laws.

In the summer of 2012, Washington, DC will be hosting the 19th International AIDS Conference. As more than 30,000 delegates from all over the world converge on the nation’s capital, the US response to the epidemic will be in the spotlight. This is an extraordinary opportunity for the city of Washington, DC as well as the cities of New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco to enact policies that protect those at risk of HIV and to eliminate those that undermine HIV prevention such as the use of condoms as evidence of prostitution.

Strong federal leadership is also needed. The US government provides millions of dollars of funding to each city addressed in this report to prevent HIV among groups at high risk of HIV infection. Condoms as evidence of prostitution should be identified as a barrier to implementing the National HIV/AIDS Strategy and federal, state, and municipal agencies should work together toward its elimination. Most importantly, the US recently pledged at the United Nations Human Rights Council to protect the human rights of sex workers, a commitment that should begin without delay. A critical step towards meeting this obligation would be to call for the end to the use of condoms as evidence of prostitution, a policy that endangers the health and lives of sex workers, transgender persons, LGBT youth, and all members of the community.

Key Recommendations

To the Police Departments and District Attorneys of New York City, Washington, DC, Los Angeles, and San Francisco

- Immediately cease using the possession of condoms as evidence to arrest, question, or detain persons suspected of sex work, or to support prosecution of prostitution and related offenses. Issue a directive to all officers emphasizing the public health importance of condoms for HIV prevention and sexual and reproductive health. Ensure that officers are regularly trained on this protocol and held accountable for any transgressions.

To the Legislatures of New York State and California and the District of Columbia Council

- Enact legislation prohibiting the possession of condoms as evidence of prostitution and related offenses.

- Reform or repeal overly broad laws prohibiting loitering for purposes of prostitution as incompatible with human rights and US constitutional standards.

To the United States Government

- The Office of National AIDS Policy and the federal

agencies charged with implementing the National HIV/AIDS Strategy should:

- Recognize that human rights abuses such as interference with a means of HIV prevention are significant barriers to reducing HIV among sex workers, transgender persons, LGBT youth, and other vulnerable groups and prioritize structural interventions to address those abuses;

- Ensure the inclusion of sex workers and transgender women in the efforts of the Working Group on the Intersection of HIV/AIDS, Violence against Women and Girls, and Gender-related Health Disparities;

- Ensure that HIV research and surveillance data adequately reflects the impact of HIV on sex workers and transgender persons;

- Call upon states to prohibit the use of condoms as evidence of prostitution and related offenses, and develop a plan to provide guidance, technical assistance, and model legislation to accomplish this objective.

- The Department of Justice should investigate the treatment by police of sex workers and transgender persons in New York City, Washington, DC, and Los Angeles. The Department should provide ongoing review, enforcement and oversight to ensure that policies and practices comply with human rights and US constitutional standards.

Methodology

This report is based on research conducted in New York, Washington, DC, San Francisco, and Los Angeles by a five-member team from the Health and Human Rights Division of Human Rights Watch between October 2011 and July 2012. Research began with inquiries to sex worker organizations and sex worker advocates, transgender, harm reduction, and HIV advocates, and public defenders in more than 15 cities throughout the United States about whether police or prosecutors were using condoms as evidence of prostitution. From this preliminary investigation New York, Washington, DC, Los Angeles, and San Francisco emerged as cities consistently reporting the use of condoms as evidence of prostitution.

Human Rights Watch interviewed an estimated 197 current and former sex workers for the report, including 77 in New York and 40 in each of the other cities. Interviews were conducted both individually and in groups, in a variety of settings that included the offices of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) working with sex workers, outdoors as part of street outreach shifts, in restaurants and other public spaces, in the offices of Human Rights Watch, and on the telephone. It is difficult to ascertain an exact number of sex workers interviewed in the course of conducting the research for this report because not everyone self-identified as such and there was often overlap among outreach workers, advocates, and others. The majority of sex workers and former sex workers interviewed were female or transgender persons, primarily transgender women.

All persons interviewed were informed of the purpose of the interview, its voluntary nature, and the ways in which the information would be used. All interviewees provided oral consent to be interviewed. Pseudonyms are used for all current and former sex workers and others requesting anonymity in order to protect their privacy, confidentiality, and safety.

Human Rights Watch also interviewed more than 110 outreach workers, advocates, lawyers, public defenders, prosecutors, judges, public health officials, and police officers in the four cities. Documents were obtained through Freedom of Information Law and public record requests and shared with Human Rights Watch from multiple sources, including the Metropolitan Police Department of Washington, DC, the Legal Aid Society of New York, and the San Francisco Human Rights Commission. All documents cited in the report are publicly available or on file with Human Rights Watch.

Human Rights Watch sought the perspective of government officials in each city including the police, prosecutors, and public health officials. Official responses in each city are detailed in the Findings section of the report.

Background

HIV continues to pose a major public health threat in the United States, where 1.2 million people are living with HIV, with one in five unaware of his or her infection. Approximately 50,000 people are newly infected with HIV each year, with racial and ethnic minorities bearing a disproportionate burden of the disease.[1] Thirty years into the epidemic, it is well established that interventions targeted at individual behavior are insufficient without attention to social, economic, legal, and other structural factors that influence vulnerability to HIV.[2] Addressing the epidemic among vulnerable populations requires understanding the risk environment in which they exist, and designing structural interventions in response. As Kevin Fenton, director of the National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD and TB Prevention of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), wrote,

Though individually based interventions have had some success, it is clear that their success is substantially improved when HIV prevention addresses broader structural factors such as poverty and wealth, gender, age, policy, and power.[3]

Sex workers and transgender persons share many elements of an environment that shapes their risk of acquiring HIV. These include physical, social and cultural isolation, stigma, and a legal and policy environment that criminalizes their behavior and often their status.[4]Transgender persons, for example, face widespread discrimination, family rejection, stigma, and poverty, factors that illuminate the limited data that exist regarding HIV prevalence among this group. Transgender advocates recently released “Injustice at Every Turn,” a survey of nearly 6,500 transgender persons in the United States.[5] The report indicated pervasive discrimination, a poverty level four times higher than the general population, and twice the unemployment rate of non-transgender people, often leaving sex work as the only option for survival. Each of these factors was even more marked in transgender persons of color, as was vulnerability to HIV and AIDS. Among those surveyed, the self-reported HIV prevalence rate was four times higher than that in the US general population, with rates for those who had engaged in sex work higher than 15 percent.[6]

The consequences of arrest are harsh for sex workers, transgender women, and other LGBT people, who face high levels of abuse, harassment, and violence in police custody and in prison.[7] Sex workers who are immigrants have additional reason to fear arrest as the US government targets “criminal aliens” for removal.[8] For both documented and undocumented immigrants, prostitution and solicitation are potential grounds for removal and inadmissibility under federal immigration law.[9] As a “crime of moral turpitude,” a conviction for prostitution, loitering with intent to commit prostitution, or solicitation can be grounds for removal from the US, but there is also a separate provision that establishes prostitution as a removable offense.[10] Under this provision a criminal conviction for prostitution is not required for a finding of inadmissibility, if immigration authorities determine on other grounds that one has “engaged in prostitution.”[11] A conviction of prostitution or a determination that one has engaged in prostitution can render one inadmissible, meaning that those in the US cannot return if they leave the country and may have difficulty adjusting their legal status. These are also grounds that can trigger the mandatory detention requirements of the immigration laws for both documented and undocumented immigrants.[12]

Condoms are a proven method of preventing transmission of HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases, demonstrated to substantially reduce the risk of HIV transmission and endorsed by international and US health authorities as an essential component of HIV prevention programs.[13] In many jurisdictions, including the United States, condoms are provided as an essential HIV prevention method among populations whose actions are criminalized or for whom sex is prohibited such as prisoners.[14] Indeed, in each of the four cities addressed in this report, millions of condoms are distributed by the public health department each year as part of highly visible HIV prevention campaigns, and in each city, condoms are made available to inmates of the city’s jails.[15]

Prostitution—defined as the exchange of sex for money or other consideration—is illegal in 49 states in the US and is prohibited in every city addressed in this report.[16] The police are charged with enforcing laws, including laws against prostitution. But enforcement must be consistent with human rights obligations, including the rights to health, to liberty and security of the person, and to freedom from cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment. Governments can and do take measures to ensure that the criminal laws do not impede human rights protection and public health, most notably by promoting harm reduction programs for drug users including syringe exchange and safe injection sites.[17] Each of the cities addressed in this report has syringe exchange programs that operate under exceptions to state drug paraphernalia laws. These programs are aimed at promoting treatment of drug addiction and preventing the sharing of needles, a mode of HIV transmission, by protecting drug users from police action in specific situations. They reflect collaboration between affected communities, law enforcement, and public health officials, an approach that should be applied to the issue of condoms as evidence of prostitution.

Findings: Condoms as Evidence of Prostitution in Four US Cities

New York City

HIV in New York City

New York City is the epicenter of the AIDS epidemic in the United States, with more than 110,000 people living with HIV and an AIDS case rate that is three times the national average. AIDS is the third-leading cause of death for New Yorkers between the ages of 35 and 54. African-Americans bear a disproportionate burden of HIV in New York, with an HIV diagnosis rate four times that of whites. Though HIV historically affected mostly males in New York, nearly a quarter of new HIV diagnoses are among women, with 92 percent of these in African-American or Latina women.[18] Young men who have sex with men, particularly young men of color, are increasingly at risk of HIV infection. In 2009, for the first time, HIV diagnoses among men who have sex with men aged 13 to 29 surpassed those among men 30 years and older.[19] Among transgender persons in New York City, there were 183 new HIV diagnoses between 2006 and 2010. Most of these occurred among African-American or Hispanic transgender women. Of the transgender women newly diagnosed with HIV, eight percent reported having engaged in sex work, a figure likely to be low given that it was based on the number of people who felt comfortable disclosing this fact to a medical provider.[20]

A recent study in New York City among people who exchange sex for money or other goods (a category broader than those who self-identify as sex workers[21]) found that 14 percent of the men and 10 percent of the women were HIV-positive.[22] This is dramatically higher than the 1.4 percent HIV prevalence in New York City generally and the 0.6 percent prevalence in the United States overall.[23]

New York State and City have devoted enormous resources to curbing the HIV epidemic, targeting prevention efforts to many of these vulnerable populations. A cornerstone of these prevention efforts is promoting universal access to condoms. The New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH) expanded an already-existing condom distribution program in the mid-1980s in response to the AIDS crisis, and in 2007 launched the New York City Condom Campaign, the first condom to be branded by a municipality in the United States. Within six months of the launch, the city’s condom distribution increased to more than three million condoms per month in the five boroughs (36 million per year). New York City currently distributes more than 40 million free condoms annually.[24] DOHMH states in its condom promotion materials, “It’s Your Right: No one—not even a spouse or intimate partner—can take away your right to use condoms, or your right to refuse sex.”[25]

Anti-Prostitution Enforcement in New York City

New York State law prohibits the offenses of “prostitution,”[26] a misdemeanor, and “loitering for the purpose of engaging in a prostitution offense,” a violation (punishable only by a fine) and a possible misdemeanor (punishable by a fine, jail time, or both).[27]Other prostitution-related offenses include patronizing prostitution,[28] promoting prostitution,[29] and sex trafficking.[30]

From January through November 2011 the New York City Police Department (NYPD) made 4,054 arrests for prostitution-related offenses.[31] This included 1, 899 prostitution cases (targeting the alleged provider of sex) and 1,192 arrests targeting alleged patrons of prostitutes. Six hundred and nineteen arrests were made for “loitering for the purpose of engaging in a prostitution offense.”[32]The vast majority of these arrests are disposed of without trial, primarily through plea bargaining or proceeding under a conditional discharge, usually requiring participation in a substance abuse or other “diversion” program.[33]

In 2011, for example, there were five acquittals in New York City for prostitution-related charges. Of cases showing a disposition, 85 percent showed “sentenced or sentence pending,” indicating a judgment of guilt. One of three persons convicted spent time in jail for the offense. In 2011 there were 35 arrests for sex trafficking in New York City (see Tables 1 and 2 below).[34]

Table 1. Prostitution Related Arrests in New York City in 2011*

|

CHARGE | ARRESTS |

| PL 230.00 | Prostitution | 1,899 |

| PL 230.04 | Patronize Prostitute – 3rd | 1,188 |

| PL 240.37 | Loitering for Prostitution | 691 |

| PL 230.20 | Promoting Prostitution – 4th | 119 |

| PL 230.25 | Promoting Prostitution – 3rd | 92 |

| PL 230.34 | Sex Trafficking | 35 |

| PL 230.40 | Permitting Prostitution | 10 |

| PL 230.30 | Promoting Prostitution – 2nd | 9 |

| PL 230.33 | Compelling Prostitution | 6 |

| PL 230.06 | Patronize Prostitute – 1st | 3 |

| PL 230.05 | Patronize Prostitute – 2nd | 1 |

| PL 230.32 | Promoting Prostitution – 1st | 1 |

| PL 230.03 | Patronize Prostitute – 4th | 0 |

* as of 11-22-11. Source: DCJS, Computerized Criminal History system.

Table 1. Dispositions of Prostitution Related Arrests in New York City in 2011*

|

ARRESTS |

|

|

Total Arrests |

4,054 |

|

Dispositions Reported |

2,460 |

|

Open, No Disposition Reported |

1,594 |

|

Total Dispositions |

2,460 |

|

Convicted: Sentenced |

2,053 |

|

Dismissed |

228 |

|

DA Declined to Prosecute |

127 |

|

Convicted: Sentence Pending |

41 |

|

Acquitted |

5 |

|

Other |

4 |

|

Covered by Another Case |

2 |

|

Total Sentences |

2,053 |

|

Conditional Discharge |

859 |

|

Fine |

527 |

|

Jail |

348 |

|

Time Served |

314 |

|

Probation |

2 |

|

Other |

2 |

|

Jail and Probation |

1 |

|

Prison |

0 |

|

Unconditional Discharge |

0 |

* as of 11-22-11. Source: DCJS, Computerized Criminal History system.

Prosecutors have attempted to use condoms as evidence in some of the few cases that proceeded to trial. Kate Mogulescu, a public defender with the Legal Aid Society of New York, has spent the last two years defending prostitution and loitering for purposes of prostitution cases in Manhattan and serving as a consultant on prostitution trials in other boroughs. Mogulescu said that in that time period, “Prosecutors tried to introduce condoms in two of the ten cases that went to trial, and in both of those the judge refused to admit them as evidence.”[35]

In a case tried by Mogulescu in June 2010 Judge Richard Weinberg of the Criminal Court of the City of New York had this exchange with the prosecutor:

Judge Weinberg: I don’t care about the condoms. This is the 21st Century.

Prosecutor: The People would like to voice their objection. This is circumstantial evidence of defendant’s intent.

Judge Weinberg: And every other woman and man who wants to protect themselves in the age of AIDS.[36]

In New York “loitering for the purpose of engaging in a prostitution offense” is defined as when a person “…remains or wanders about in a public place and repeatedly beckons to, or repeatedly stops, or repeatedly attempts to stop, or repeatedly attempts to engage passers-by in conversation, or repeatedly stops or attempts to stop motor vehicles, or repeatedly interferes with the free passage of other persons, for the purpose of prostitution.”[37]The loitering for purposes of prostitution law has long been considered unconstitutionally overbroad by civil liberties advocates in New York State. In 1978 it was challenged as too vague to provide adequate notice of what conduct was illegal, a violation of the right to due process of law under the 5th and 14th Amendments, but the law was upheld by the New York Court of Appeals.[38] The Court specifically upheld the use of circumstantial evidence for the loitering charge, including the location of the defendant in a “known” prostitution zone, the officer’s prior arrests of other people for prostitution in that location, and recognition of the defendant as a previous prostitution offender.[39]

According to the New York Police Department Patrol Guide, police officers are permitted to include the suspect’s location, conversations, clothing, conduct, associates, and status as a “known prostitute” in order to establish that someone is loitering for the purpose of engaging in prostitution.[40]This and similar loitering laws are problematic from a human rights perspective, in that they grant police wide latitude to engage in unjustified interference with lawful activities short of actual solicitation. Such laws enable arbitrary and preemptive arrests on the basis of profile or status, rather than criminal conduct.[41]

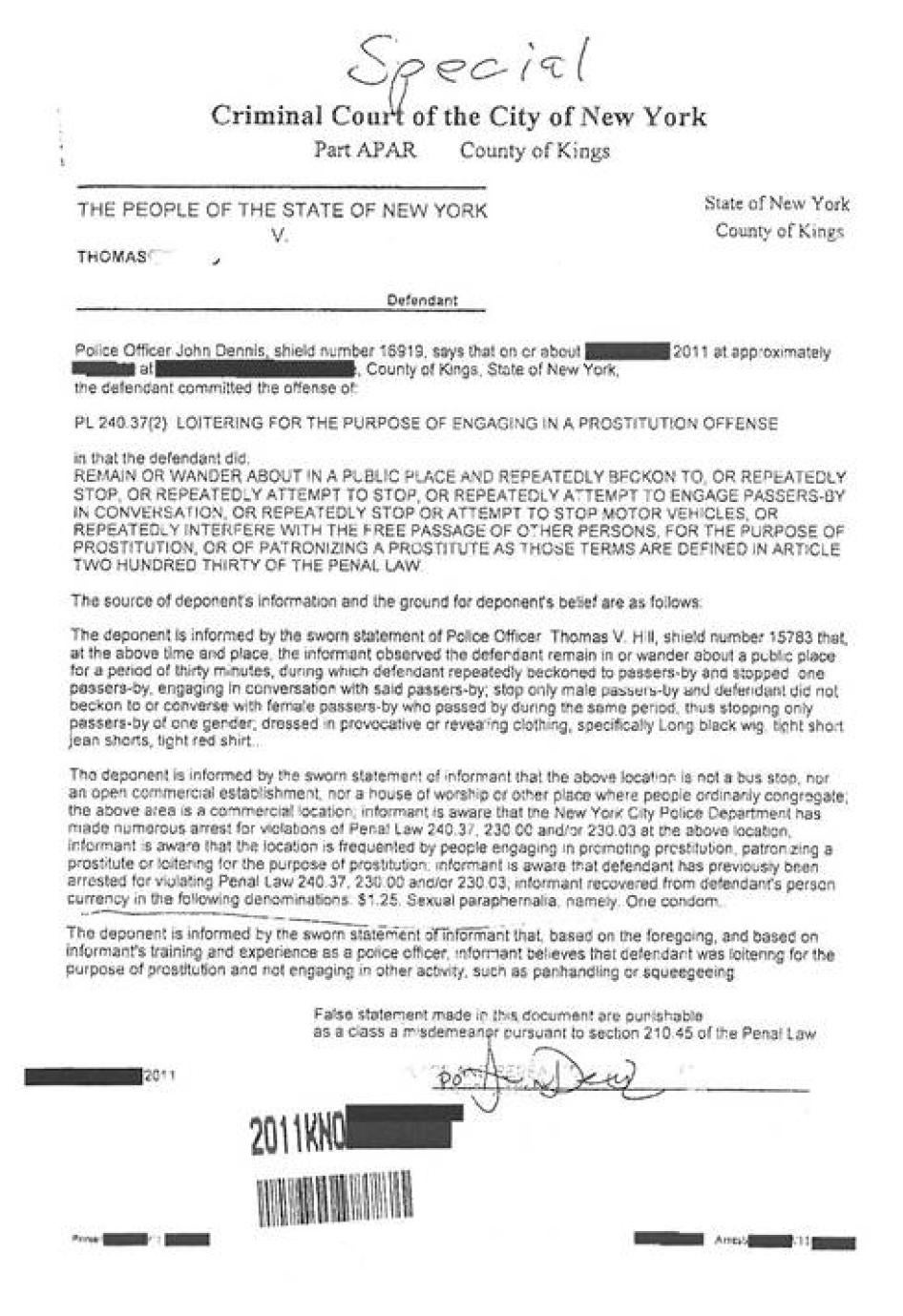

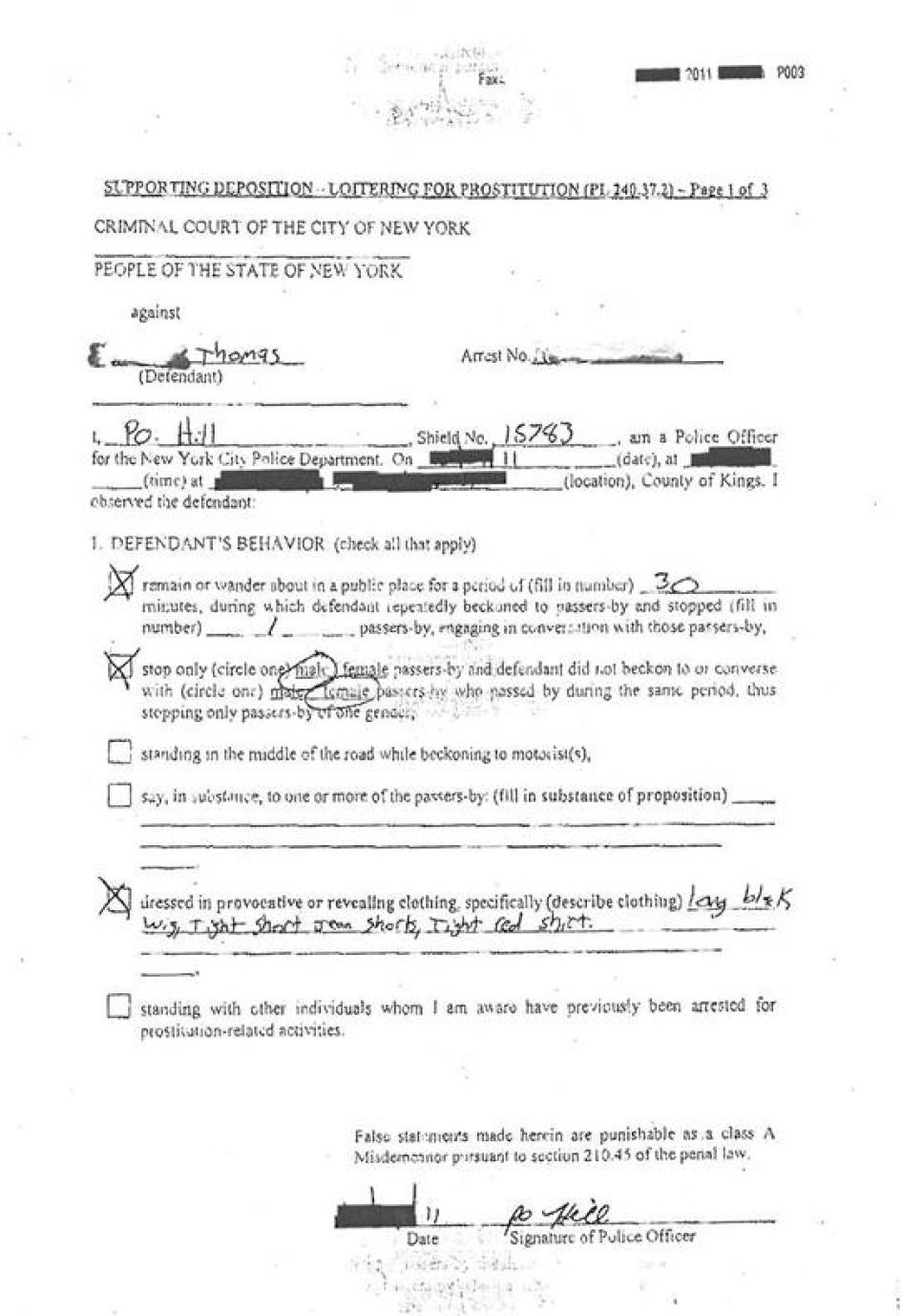

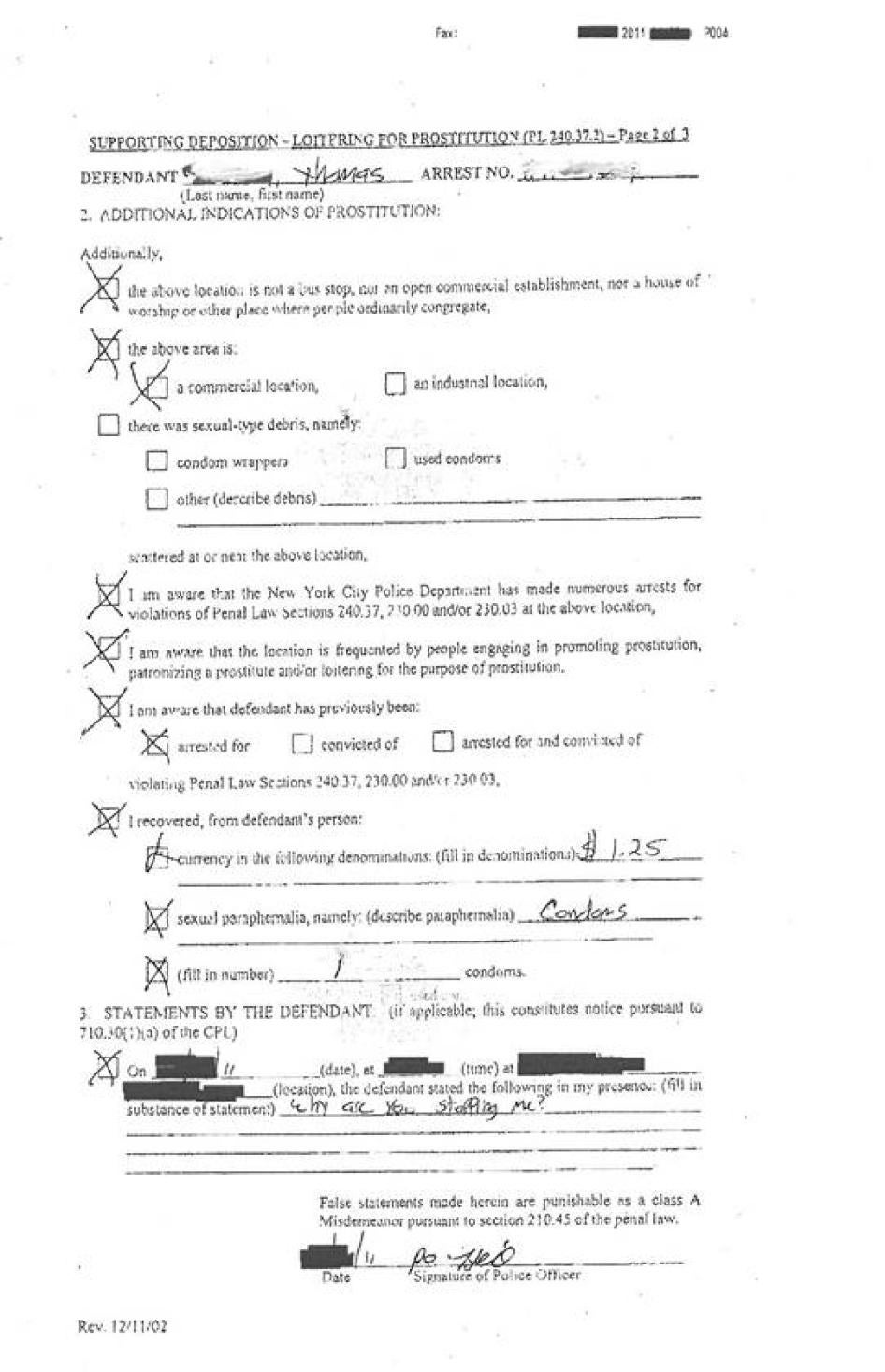

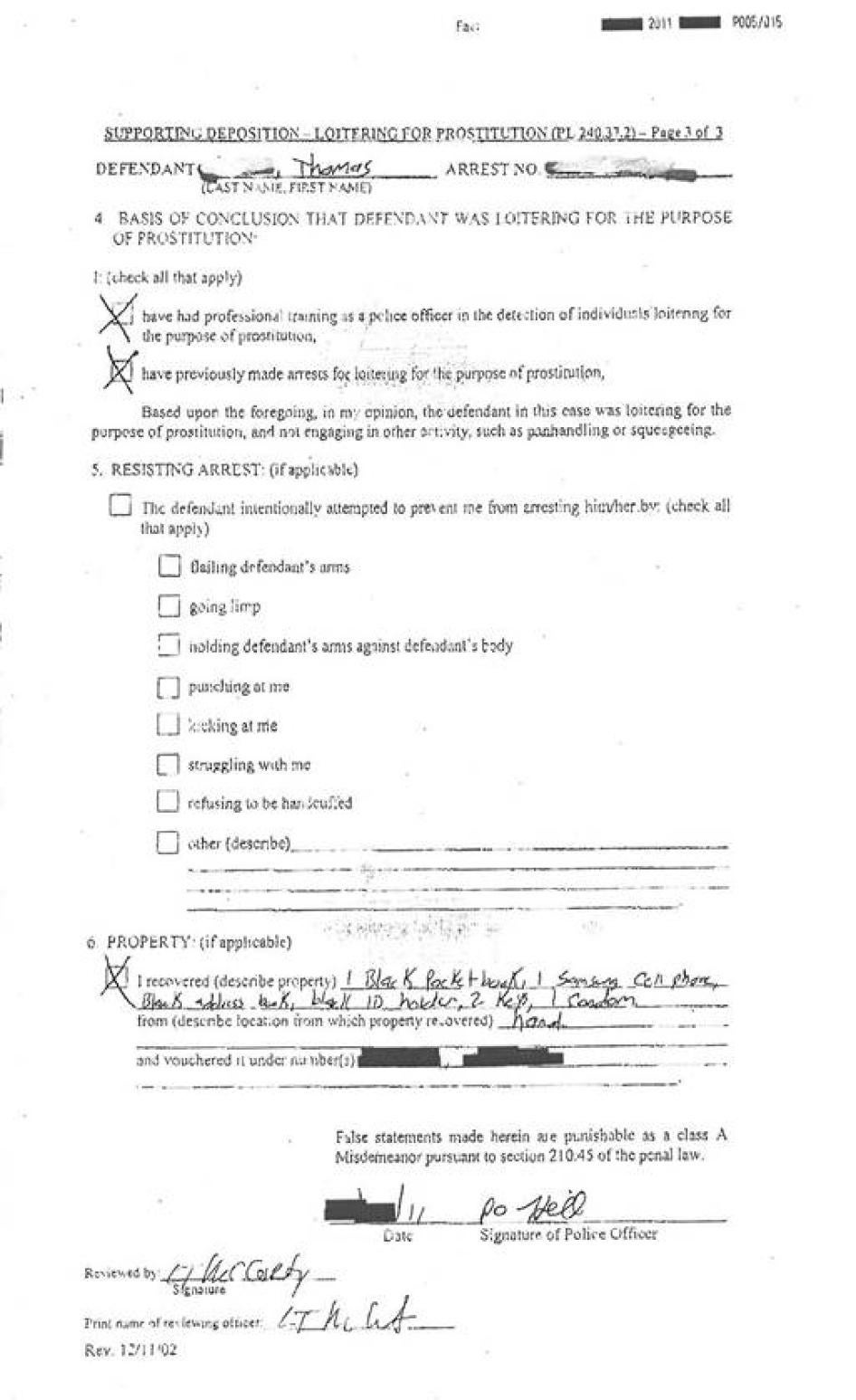

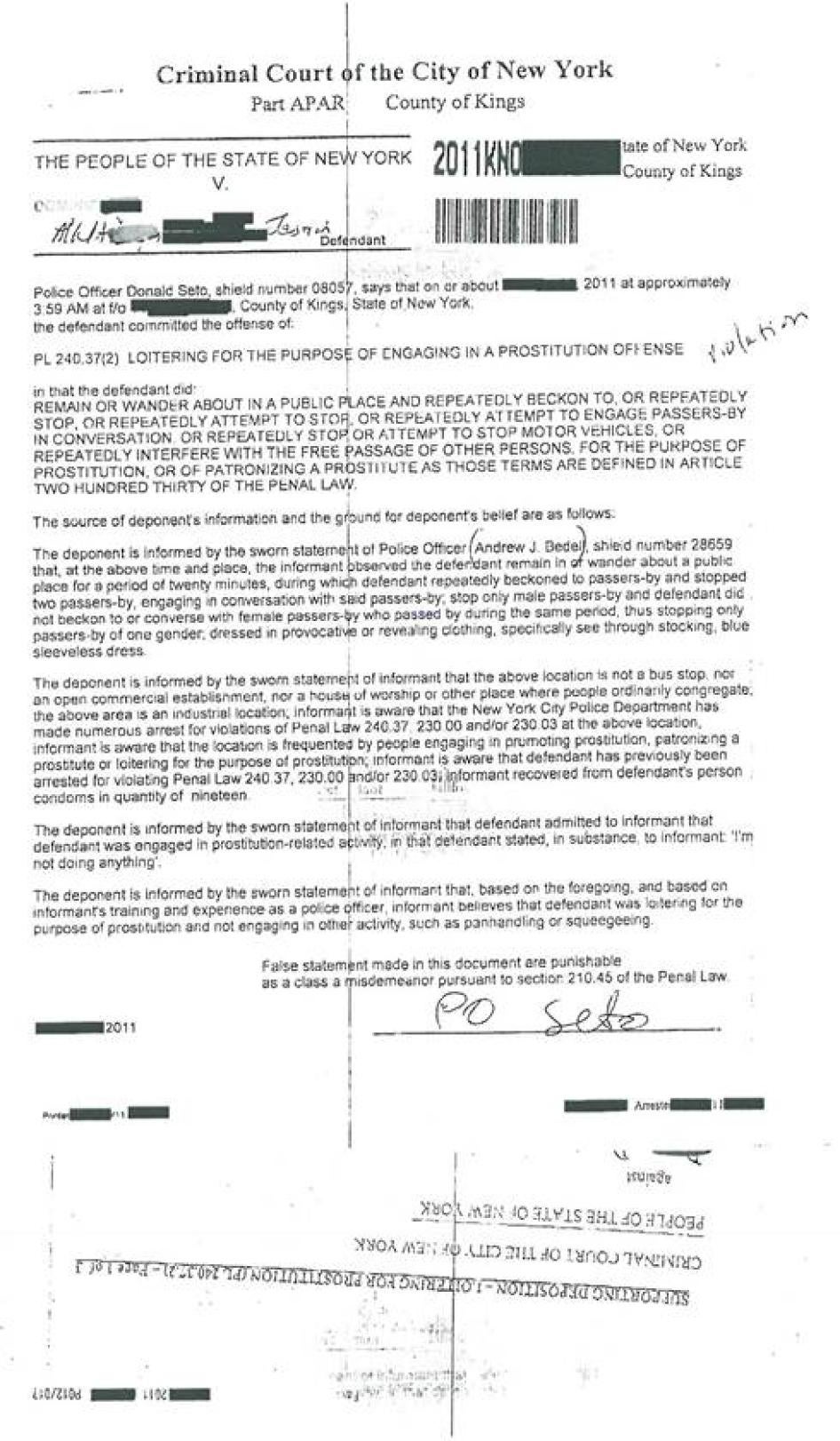

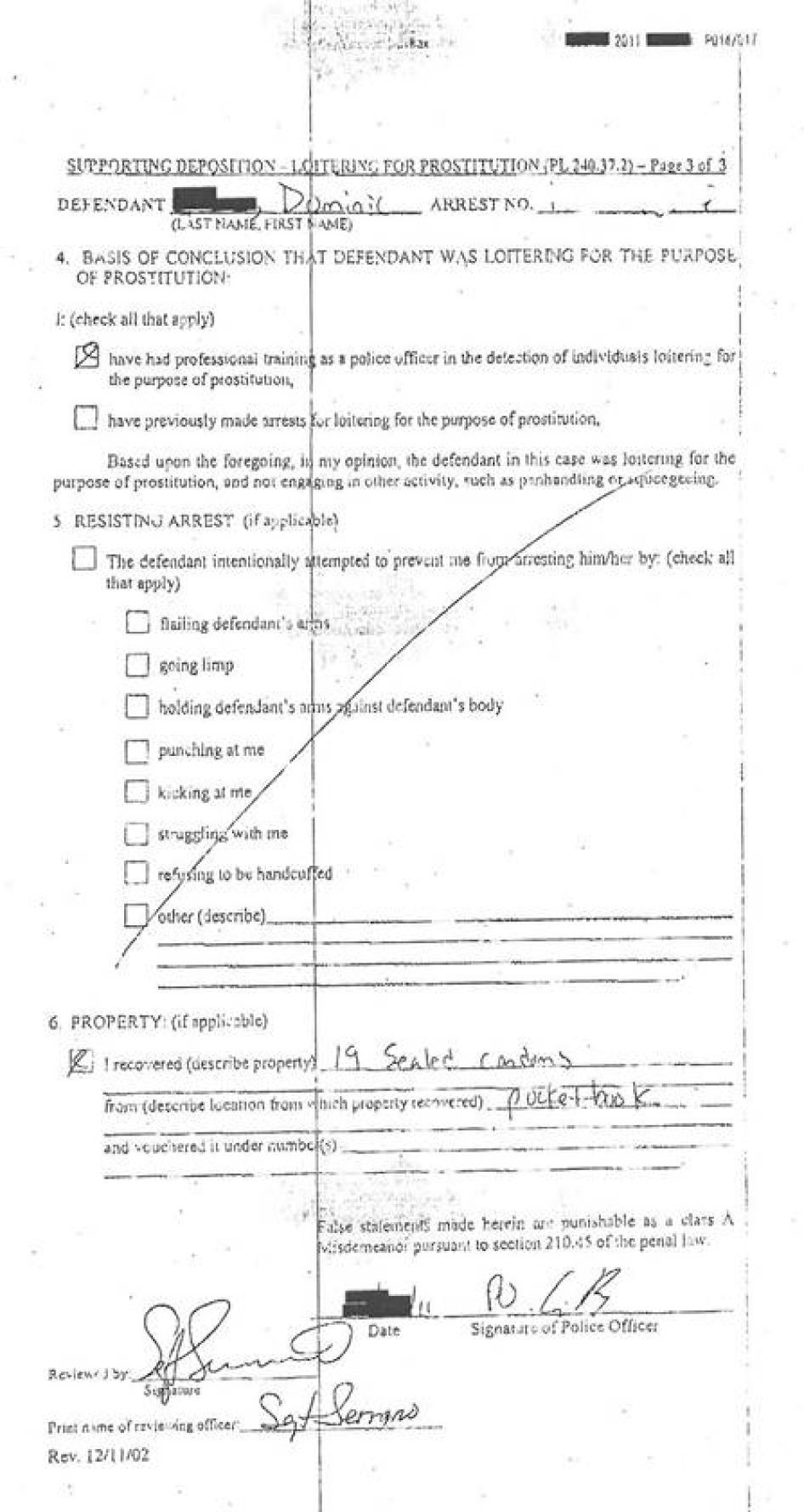

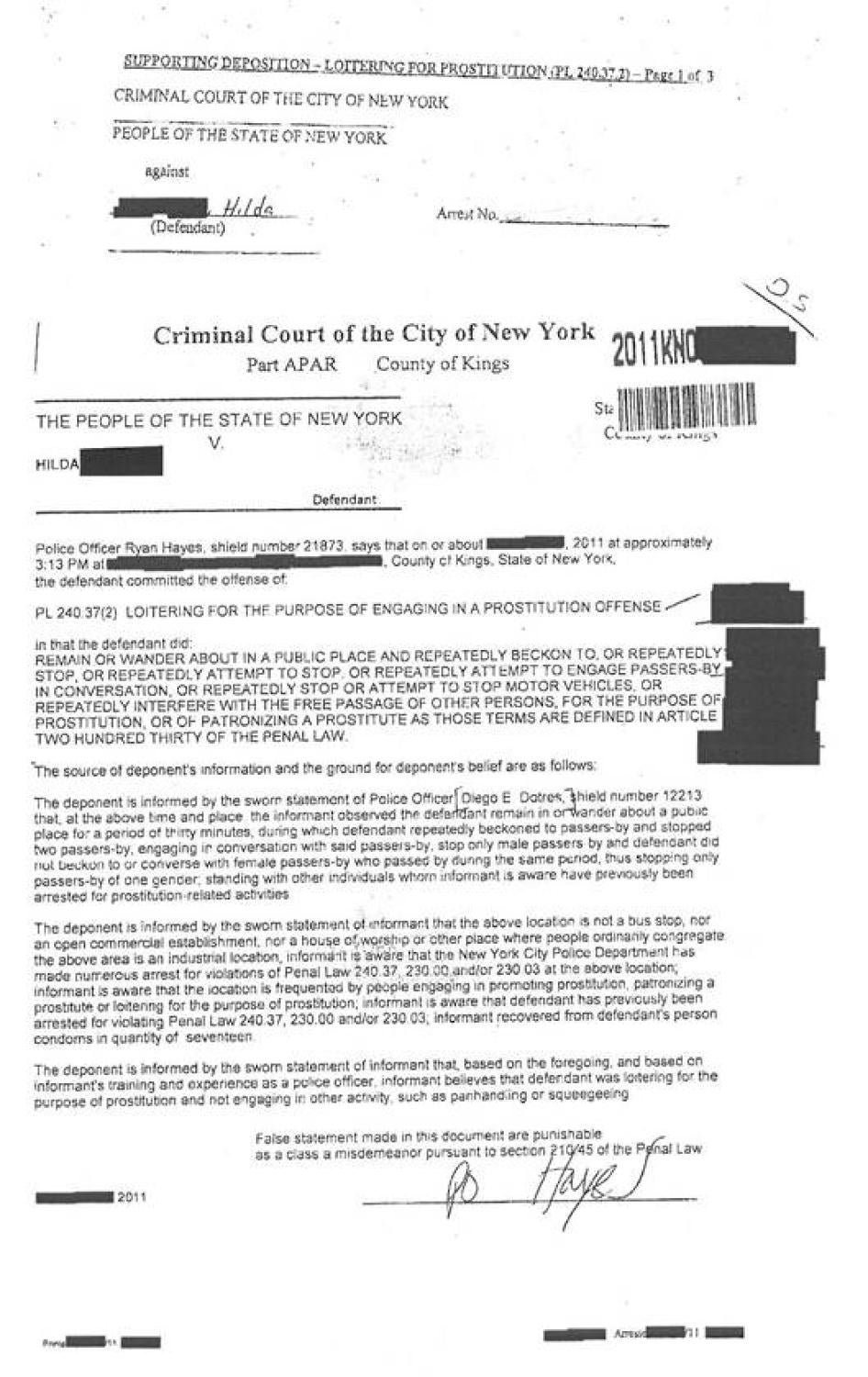

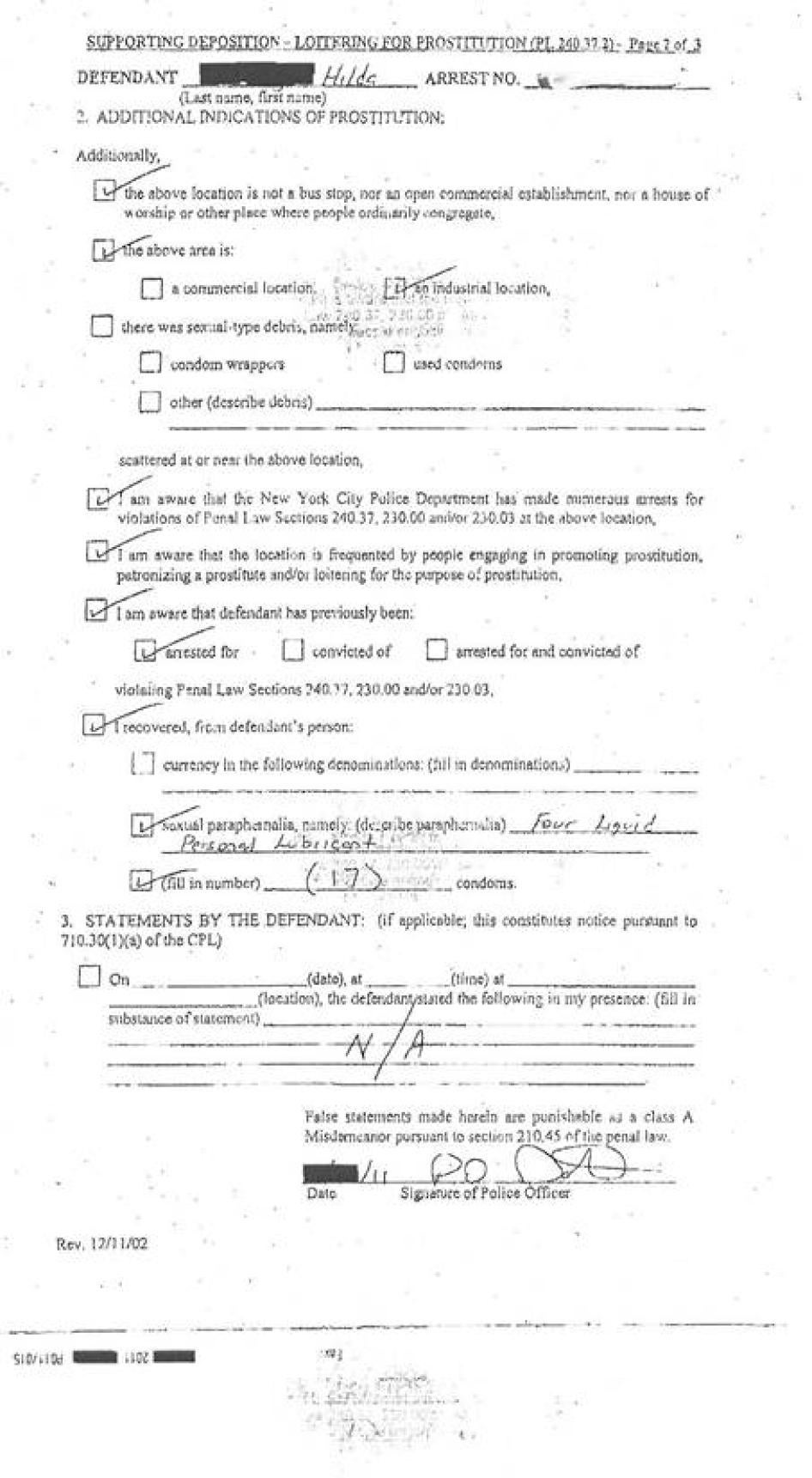

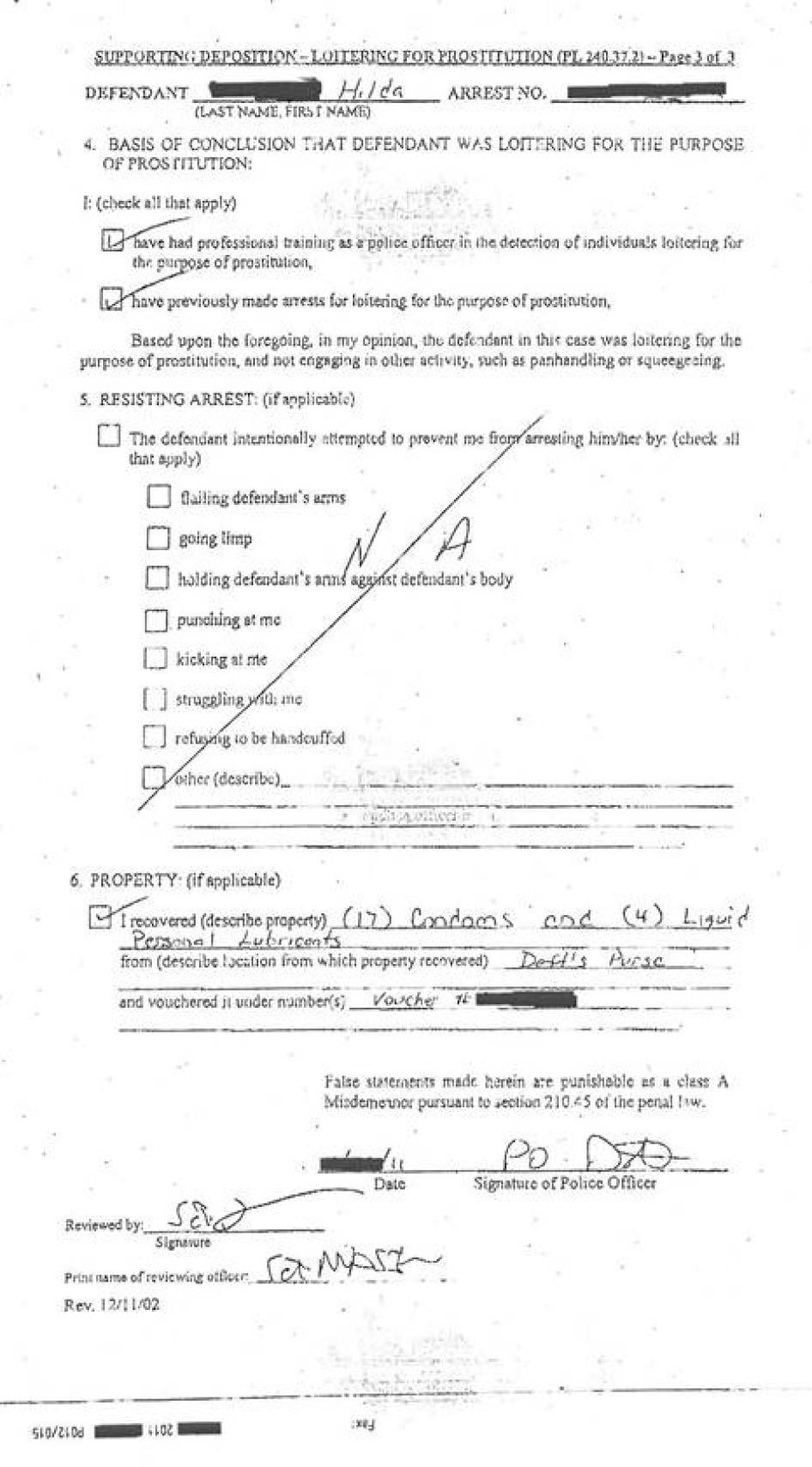

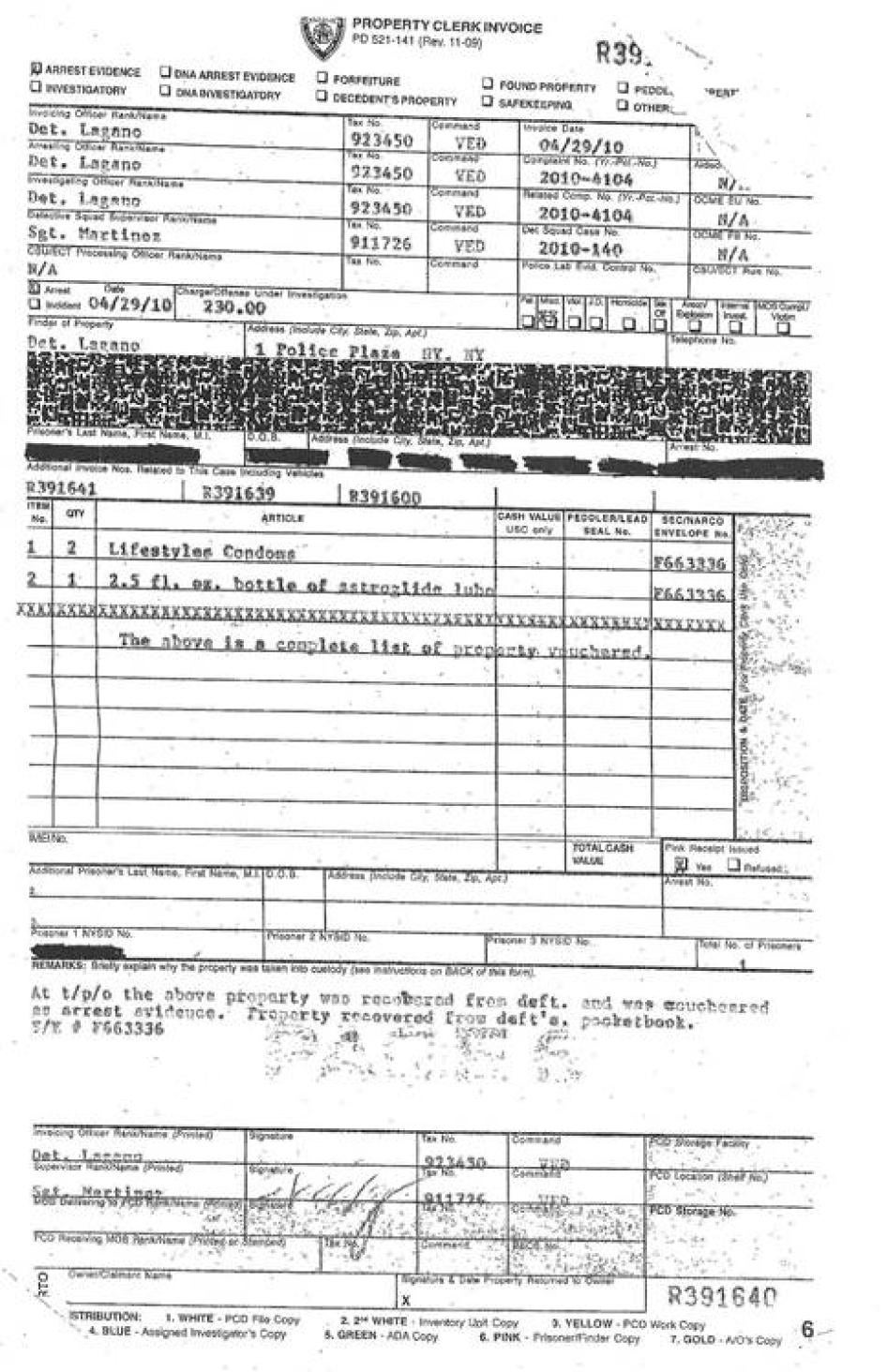

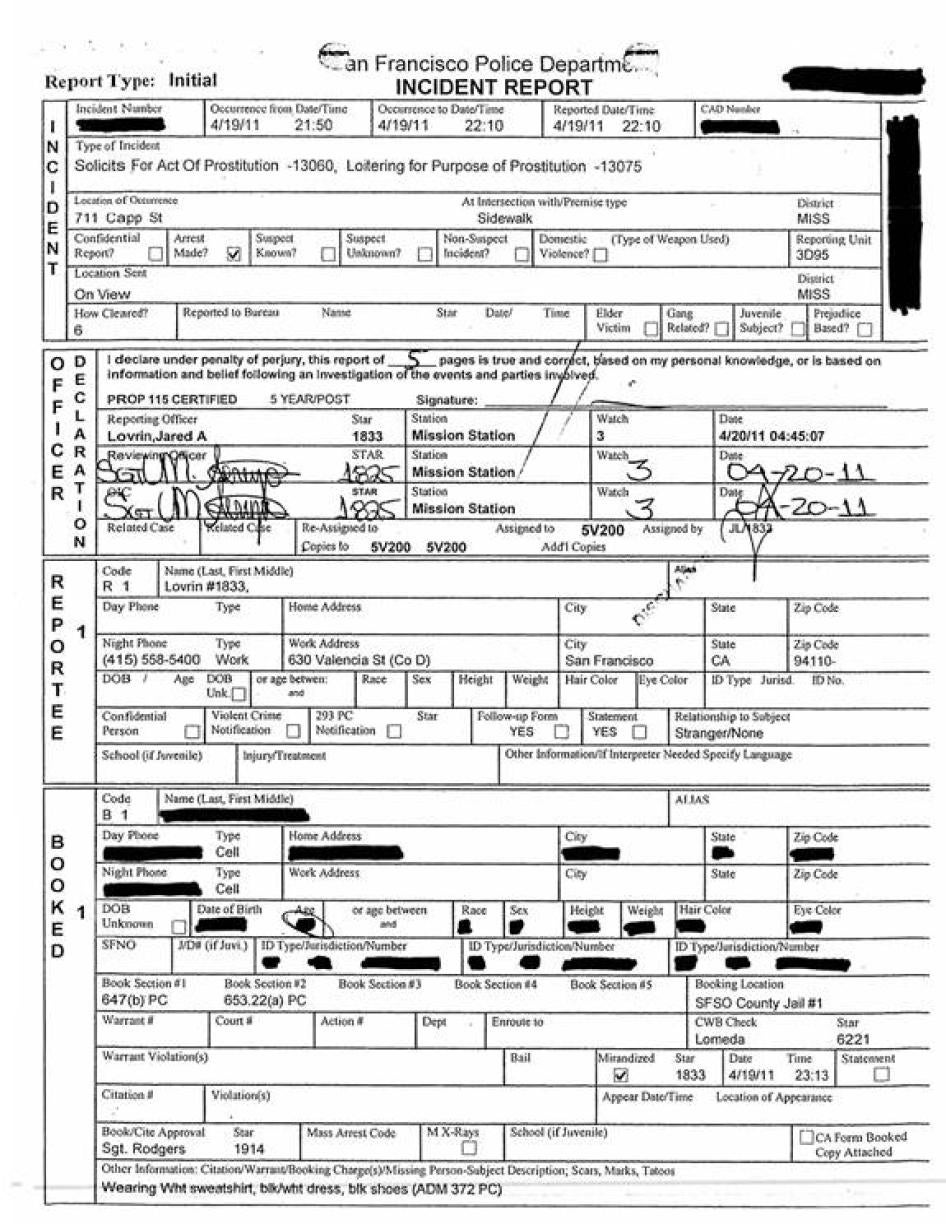

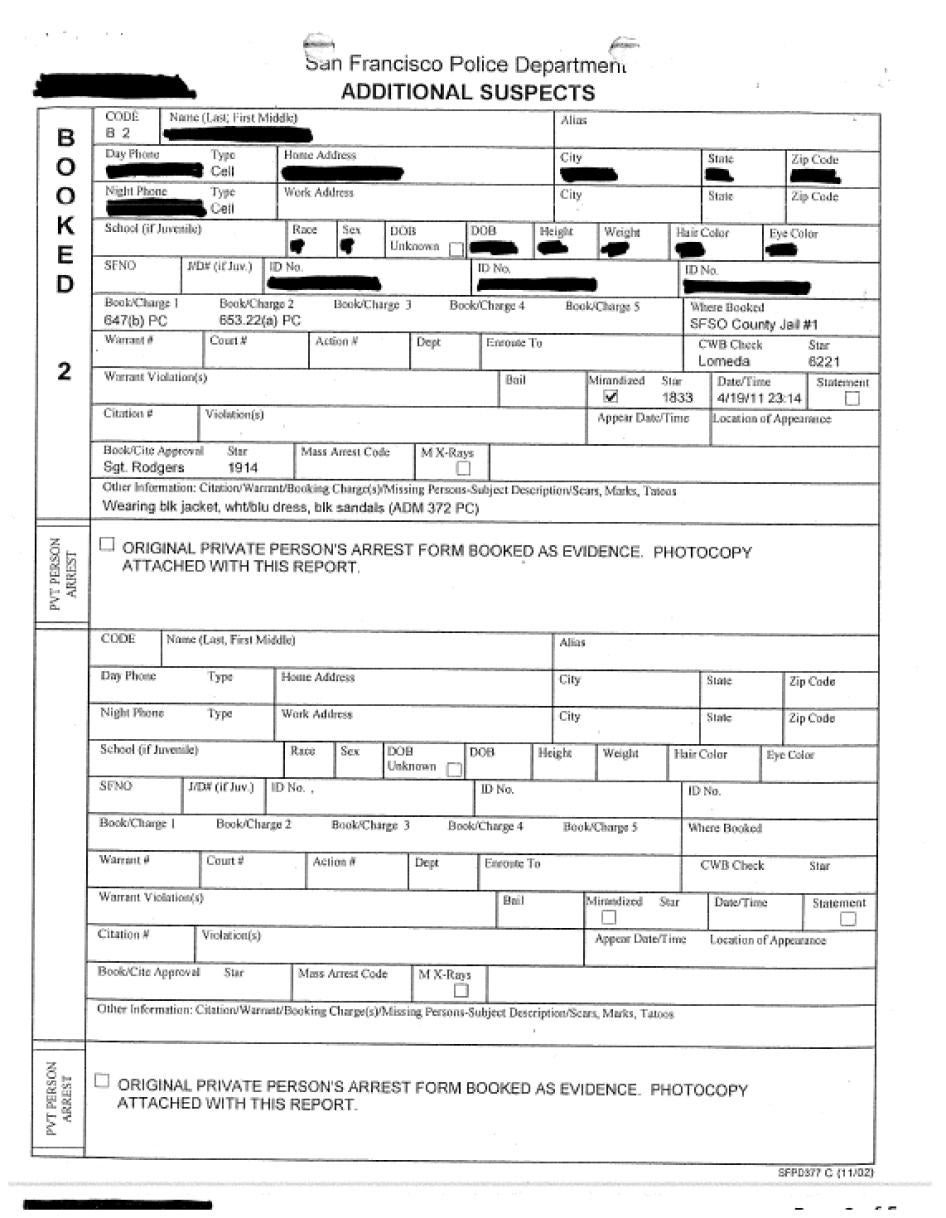

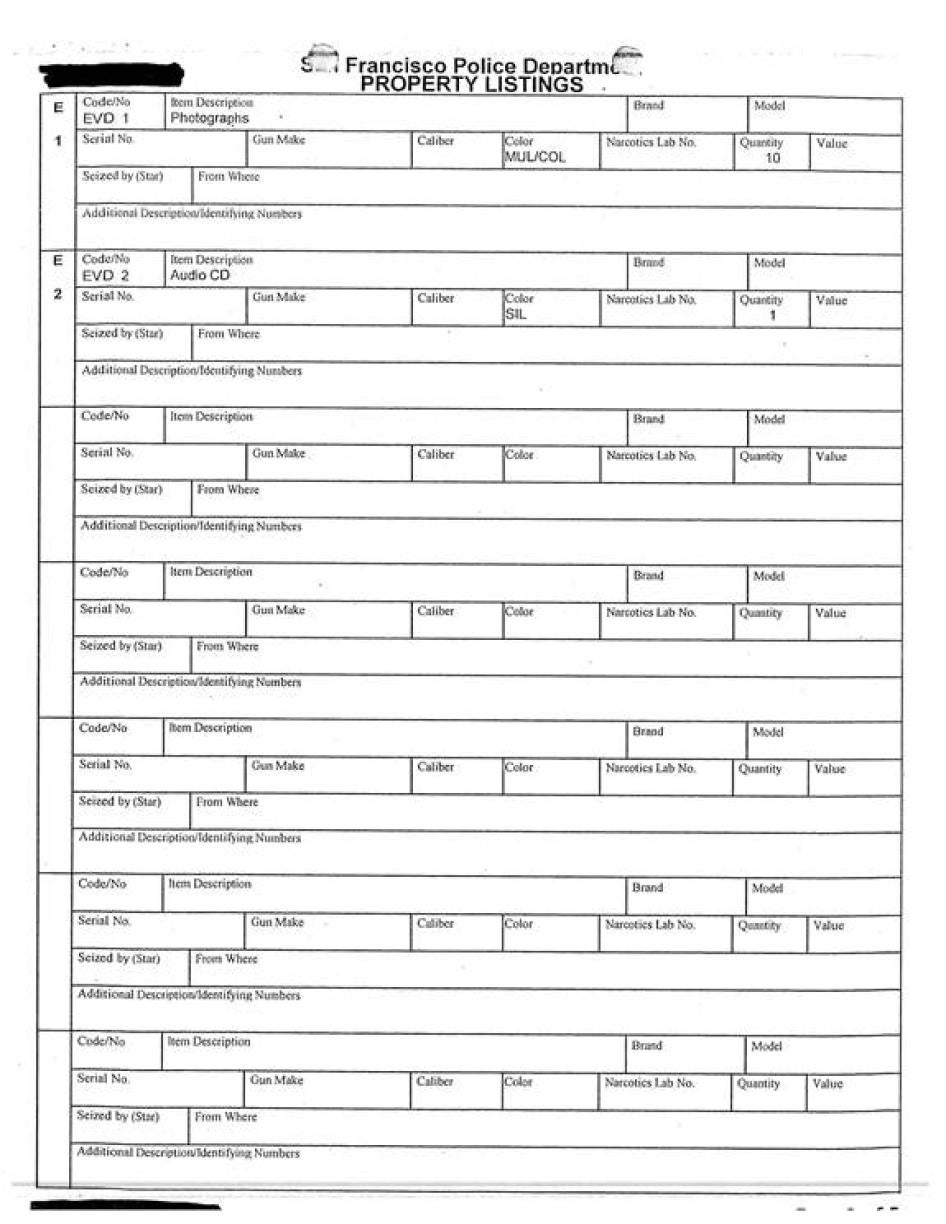

Under federal and state law, police may stop an individual on a reasonable suspicion of criminal activity.[42] Police may conduct a search if there is probable cause to believe that the person committed a crime.[43] The expansive grounds for suspicion under New York’s loitering for the purposes of prostitution statute permit police to stop and search individuals for a wide variety of reasons and it is during these searches that condoms may be discovered and seized. Condoms may also be seized as evidence of non-loitering prostitution charges such as those based on solicitation of an undercover police officer or other grounds.[44] In Brooklyn criminal courts “condoms” are one item listed as an option as “additional evidence of prostitution” on forms filled out by police officers in support of prostitution and loitering charges. On forms used in Manhattan criminal court, officers have added condoms to the narrative as “additional evidence” to support prostitution charges. Examples of forms filed in Brooklyn and Manhattan criminal courts identifying condoms as evidence of prostitution are included in Appendix A.

Condoms as Evidence of Prostitution

Human Rights Watch interviewed sex workers in Manhattan, Queens, Brooklyn, and the Bronx. In each borough sex workers told Human Rights Watch that they were frequently stopped by police and searched. In many instances police seized the condoms and routinely commented on the number of condoms they were carrying when condoms were found as part of a search.

Police Stops and Seizure of Condoms

Tanya B., a Latina transgender sex worker in Queens, stated,

I was stopped and threatened. The cops said ‘empty your purse.’ I cleared out everything but left the condoms at the bottom—I got caught. They said ‘how come you didn’t pull out the condoms? I can arrest you because of this.’ I said ‘it’s not a problem, I have no weapons, no drugs’ and the police officer said ‘next time I will arrest you because this is evidence you are a prostitute.’[45]

Pam G., a woman who has Multiple Sclerosis and is a sex worker, told Human Rights Watch of her experience in Coney Island, Brooklyn:

The cops say, ‘what are you carrying all those condoms for? We could arrest you just for this.’ They use it to push the issue of searching me. It happens all the time around here. I may be carrying eight condoms. If you have more than three or four on you, they will take them, they will be disrespectful.[46]

Alysha S., an African-American sex worker in Hunt’s Point, Bronx, stated,

I have been picked up because I have condoms, it happened to me. I had five. I was by McDonald’s, I was walking down the street, he [policeman] went into my pocket, I always have them in my pocket.[47]

Misinformation about the Legality of Condoms

For some sex workers the use of condoms as evidence of prostitution leads to confusion about how many they can carry and a perception that condoms are illegal. Sienna Baskin is a lawyer and co-director of the Urban Justice Center’s Sex Worker Project. Baskin said that sex workers frequently ask, “How many condoms it is legal to carry in New York City?” Baskin informs them that it is legal to carry as many as one wishes.[48]

Lynn A. had just moved to New York from the Midwest. She said, “I didn’t know this was happening at all, I didn’t know carrying a condom was a crime. I just came from Minnesota and in Minnesota they give out condoms.”[49]

Police Profiling as Sex Workers

Many people complained of being stopped, searched, or arrested while engaging in legal activity, many just while walking in their own neighborhoods. Along with appearance, being known to officers as a sex worker, or being in an area “known” for prostitution activity, condoms could lead to women being identified by police as sex workers. Lola N., an African-American sex worker in Hunt’s Point, Bronx said,

One day I was walking with a boyfriend and a vice cop pulled up, jumped out. My boyfriend, he had weed on him and they let him go. They arrested me. They found condoms on me. They say I was arrested for solicitation.[50]

Many members of the Queens Latina transgender community experienced being stopped and searched by the police on suspicion of prostitution while walking in their own neighborhoods. Alexa L., a transgender woman from Mexico, said,

Eight days ago I wasn’t working because I was sick. I left my house to get a coffee, and had two condoms in my pocket. The police stopped me and said ‘what are you doing?’ I said I was getting coffee. They searched me and found two condoms. They asked ‘what are you doing with two condoms, what are they for?’ I said they were for protection. They took the condoms. I couldn’t get coffee, I was so scared. I felt very bad. I’m not a delinquent, I didn’t steal. When they searched me and found them, I was shaking, I was so scared.[51]

Selena T., told Human Rights Watch,

They have emptied out my whole purse. The cops assume I’m a prostitute, they stop me, open my purse, check if I have a certain number of condoms. They are always looking for condoms when they open your purse.[52]

Yanira C. was at the movies before she was arrested:

I was with a friend on 82nd and Roosevelt. We came out of a movie theater. Some cops in a van came over, said I was being arrested. The cops said I was too beautiful. The charge was that I had more than one condom in my bag. They locked me up for two days for solicitation and prostitution…they said I had condoms, it was on the report.[53]

Mona M. is from El Salvador and has lived in Jackson Heights, Queens for ten years. She is a transgender woman who takes it upon herself to provide condoms to other sex workers. She said, “To the police, all transgenders are prostitutes.”[54]

Juan David Gastolomendo is executive director of the Latino Commission on AIDS, a nongovernmental organization providing support and outreach services to Latina transgender women in Queens. According to Gastolomendo their clients are regularly targeted as prostitutes by law enforcement:

The false arrest is mainly on loitering charges, including loitering for prostitution. It ends up boiling down to being a trans woman in a place where known sex work is happening. The arrest is based on the client’s identity and where the arrest happens. These are places where prostitution happens, but they are also places where people socialize.[55]

Police Interference with Outreach Activities

Several women who often engaged in peer outreach and education described how police interfered with these activities. Anna E., a 32-year-old former sex worker from Mexico, said,

I went back to the clubs in Jackson Heights, not to be a prostitute, but just to go back to the clubs. I can’t walk on Roosevelt Avenue between 72nd Street and 82nd Street because the police are there and they immediately think I’m a prostitute. I can’t carry condoms like I used to and give them to my friends. I have a terror about it. I am panicked especially since now I have a job as a stylist. I feel I can’t give out condoms to my friends because I am afraid to carry them.[56]

Mona M. sits in a neighborhood restaurant at a regular time so that she can provide condoms to women who are afraid to carry condoms when they are working:

The majority have fear, they don’t carry condoms…. I’m an outreach worker. They know Mona will be in the cafe. They will only come when they have a client, get one condom, then leave with the client. For me it’s a risk to have the condoms in my purse. But I’ve worked as an outreach worker, and I feel obligated to carry condoms because if someone comes up and asks me, and I don’t have one, what are they going to do?[57]

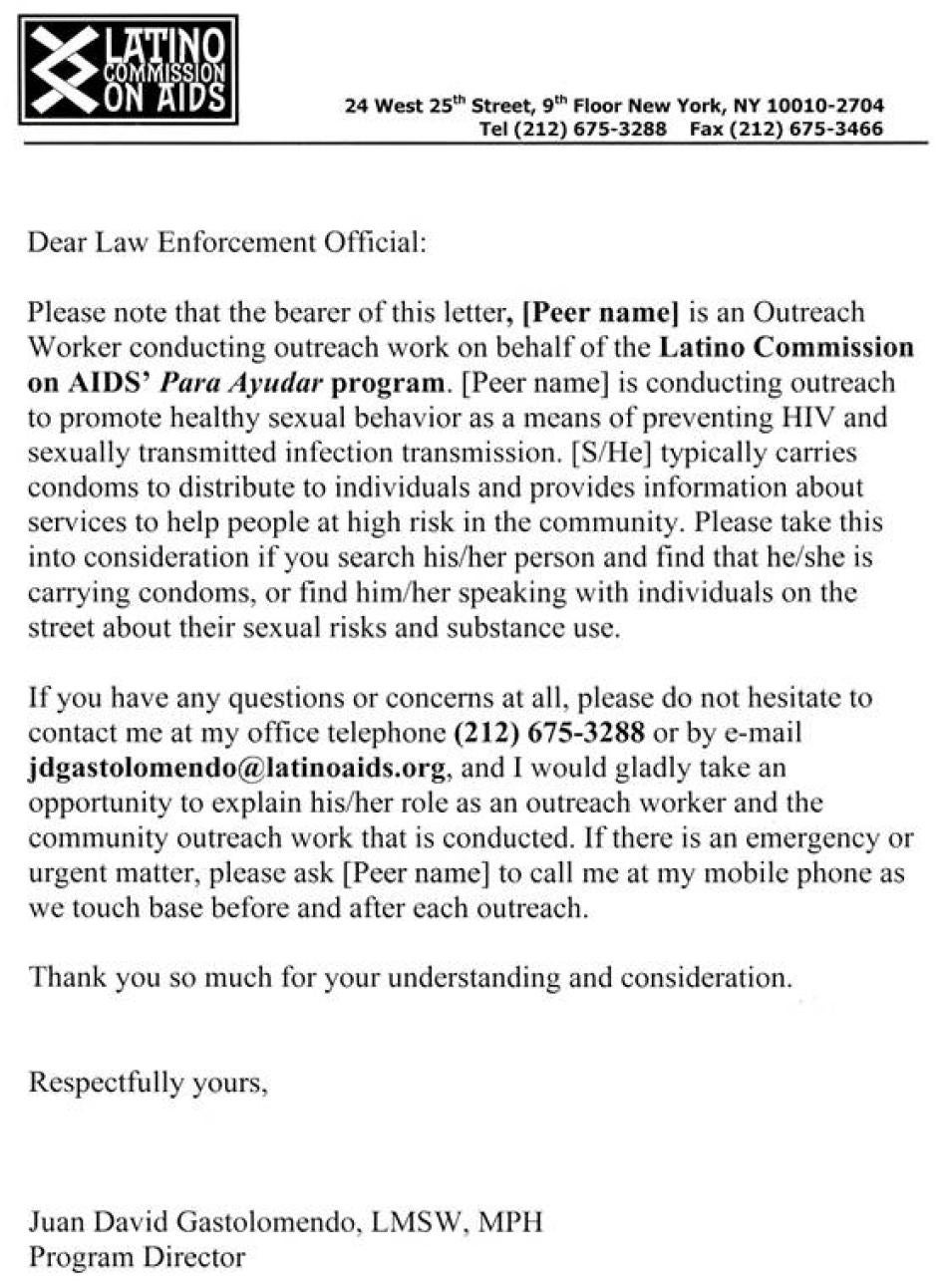

Police also have harassed outreach workers from service organizations despite workers’ explanations and presentation of identification issued by their employers.[58] In Queens and other boroughs the Latino Commission on AIDS gives each outreach worker a printed form to carry explaining to police why they are carrying and distributing condoms in the neighborhood. A copy of this form is included as Appendix B.

Immigration Consequences of Arrest for Prostitution

The immigration laws put undocumented sex workers in a serious dilemma. According to public defenders in New York, they are acutely aware of the untenable situation their clients face and often must advise their clients to plead guilty to an offense in order to be released from custody. They want to avoid going to Rikers Island Correctional Facility where federal Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents screened arrivals for immigration violations.[59] As Barbie M., an undocumented sex worker, described it, “I pled guilty to prostitution, my lawyer said to plead guilty, I had no other option because if I didn’t plead guilty I would stay in jail and be deported.”[60]

However, as of May 15, 2012, avoidance of immigration screening will no longer be possible, as ICE began to implement the Secure Communities Program. Under this program the fingerprints of all persons arrested by local police are sent to federal immigration authorities for review to determine whether they should be detained for immigration purposes.[61] For sex workers who are undocumented and transgender this development is particularly disturbing as deportation can mean a return to countries where they have endured life-threatening abuse and discrimination. Juan David Gastolomendo of the Latino Commission on AIDS said,

We see mainly false arrest, profiling. Latino immigrants, trans, MSM. This has immigration implications, which is a major concern. They will be deported to the situations they were fleeing from. The trouble with this is that a lot of individuals who are deported could file for asylum if we had the resources for this.[62]

Fear of Carrying Condoms as a Result of Police Action

Many sex workers reported that they continued to carry condoms despite fear of arrest. For others, however, fear of arrest, jail time, and conviction on prostitution charges overcame their need to protect themselves from HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases. Anna E. said,

Am I afraid to carry condoms? Yes I was for a long time. When I was working on the street, I felt like I could only carry two or three, not a lot when I went out…[63]

Nola B. explained that transgender sex workers may need more than one condom during an exchange:

For sex workers who are transgender, sometimes the transgender has to put on a condom, so does the client. So you need two. Or they could break. One to two is not enough.[64]

Outreach workers who provide harm reduction services on the street confirmed that sex workers were often reluctant to take condoms for fear of arrest. An outreach worker in the Bronx and East Harlem said,

We usually hand out two packs [of condoms] at a time. I’ve had girls give one pack back and say ‘we’ll share.’ Sometimes they are not carrying anything to carry them in, and with them getting stopped so often, they don’t want to have a lot on them.[65]

Lorena Borjas, an outreach worker for the Latino Commission on AIDS in the Queens Latina transgender community gave a similar testimony:

The police are arresting a lot of people in Jackson Heights. The girls are afraid to carry condoms…The Department of Health says protect yourself, you see their advertisements on TV, on the radio, on the subway. But the police in Queens are either not well trained, or don’t know better that they are doing things wrong. They are arresting girls and using condoms as evidence.[66]

Mito Miller, an outreach worker in the West Village in Manhattan told Human Rights Watch,

I have never had any young men afraid to take condoms, only black and Latina trans women who have refused to take them. I’ve had people not take condoms, people who do go through a rigorous routine of hiding them. They were wrapping them in paper, so they were gift-wrapped…They took a couple, but consciously limit themselves, even though they know they are working and would need more, because they couldn’t hide them.[67]

Several sex workers stated that because of police practices they had no choice but to engage in sex work without condoms as a result. Alexa L. said,

I use condoms. I take a lot of care of myself. But the police affect our ability to carry them. Sometimes I’m afraid and have not used them. I am very worried about my health.[68]

Tanya B. said she runs out of condoms but has to keep working:

[Police action] affects my ability to carry condoms. A lot of girls carry one to two condoms but some nights are very successful and you have to do the last one [client] without one.[69]

Anastasia L., a transgender woman from Mexico who did sex work in Queens until 2007, said,

If I took a lot of condoms, they would arrest me. If I took few or only one, I would run out and not be able to protect myself. How many times have I had unprotected sex because I was afraid of carrying condoms? Many times.[70]

Police Abuse, Harassment, and Misconduct

Sex workers reported that whether condoms played a role or not, interaction with police frequently was accompanied by verbal and physical abuse. This was particularly true for transgender women, as reported by Victoria D.:

All my arrests always came from just walking on the street, coming out of a club, or just because a cop identified me as transgender. They would always look for condoms. They don’t care about you, they take your purse, throw it on their car, your stuff they throw it on the floor, they pat frisk you, they ask if you have fake boobs, take them off right there, if you have a wig, take it off. It’s humiliating. Right there in the street, they take your identity right there. When they find condoms, they say ‘what are these for… how many dicks did you suck today? How much money did you make today?’[71]

Alexa L. told Human Rights Watch,

Five months ago, I was going to see my partner, my husband. A police van stopped and four police officers came out. They stopped me, put me in handcuffs, and asked what I was doing. I said I was going to see my partner, and they said I was lying, that I was prostituting myself. They pushed me against the wall and I scraped my knee and my cell phone fell down. They were saying …‘fuck you gay’… That time they arrested me and I had one condom in my breast. They found it and took it and threw it away.[72]

Transgender women described abuse by law enforcement officers in Queens Central Booking, The “Tombs” detention complex in Manhattan and at Rikers Island Correctional Facility. Tara A. was in Queens Central Booking in April of 2011:

I spent 24 hours in Central Booking in Queens. Just 24 hours in hell, the psychological side is affected because you have to go in an area with men. It’s not just being arrested…In front of me men were insulting me, saying ‘faggot.’ I felt discriminated when they took my fingerprints, they put on gloves, like they were disgusted. They made fun of me, the police officers. Sometimes I’d walk by the men and they’d say ‘you’re pretty.’ The police officer would say ‘she’s not a woman, she’s a man.’[73]

Transgender women described many incidents, including extortion for sex, which, if perpetrated by policemen, would constitute criminal activity or misconduct. Some occurred several years ago but there were recent incidents as well. Brenda D. told Human Rights Watch about an incident in December 2011:

I went into a car with a person. He said he was a police officer and said ‘if you help me I’ll help you.’ He said he wanted oral sex. He showed me a badge. He said if I didn’t have oral sex with him he would call the police and arrest me for prostitution. [74]

Valerie S., a transgender sex worker from Queens described an incident she said occurred three months earlier:

An Asian police officer came up. I thought it was a client, I went into his car. I put my hand on his, he didn’t let me and we kept driving. I started leaving the car at the red light. He said ‘stop, I’m police’ and showed his badge. He said he wanted oral sex. I said ‘what do I do’? Looking at the badge, I didn’t want to get arrested.[75]

Mona M., a former sex worker who now does outreach in the Queens transgender community told Human Rights Watch,

I’ve heard from some of the girls that they have an agreement with the police. It means if you have sex with me, your charges will disappear.[76]

None of these individuals complained to the police or other authorities. Anna E. was forced by a New York City police officer to have sex with him in Queens in 2006. She explained why she never reported the incident:

No, because I was too terrorized by all the other interactions with the police, I haven’t reported it until now [that I am sharing it with Human Rights Watch]. I have faced so much discrimination and trouble with so many cases, and so many psychological problems with the case, I didn’t want any more trouble. But if I had the psychological state to do it, I would, because I think it’s important.[77]

NYPD mistreatment of transgender people has been documented by Amnesty International and others.[78] On June 12, 2012, the NYPD announced reforms to the official patrol guide intended to improve interaction between police and members of the transgender community.[79] This is a step forward but the testimony of individuals interviewed for this report indicates much work remains to protect the human rights of sex workers and transgender persons in New York City.

LGBT Youth Affected By Condoms as EvidenceMen who have sex with men and LGBT youth are at high risk of HIV infection in New York City. In 2009, HIV diagnoses among men who have sex with men aged 13 to 29 surpassed, for the first time, those among men aged 30 and older.[80] In New York City between 2006 and 2010, new HIV infections among young men who have sex with men, particularly young men of color, were consistently higher than in any other transmission category.[81] One in four LGBT teens runs away or is forced to leave home, and between 20 and 40 percent of homeless youth self-identify as LGBT. [82] Many may not identify as sex workers but may exchange sex for money, food, and other necessities. LGBT youth report being harassed for possessing condoms by police enforcing anti-prostitution laws. Streetwise and Safe (SAS) is an advocacy organization for LGBT youth of color focused on challenging harmful criminal laws, policies, and practices that target this population. In 2011 SAS participated in research conducted by the PROS (Providers and Resources Offering Services to sex workers) Network and the New York Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH) by surveying peers in their age group and others about police harassment for condoms. Of those surveyed by SAS members, 60 percent had been stopped and searched by a police officer, and one-third said police had taken condoms away from them. Half of the survey participants said they feared carrying condoms because of trouble with the police.[83] Outreach workers to LGBT youth told Human Rights Watch about a young girl in Manhattan who refused to take more than one condom out of fear of arrest: I was handing out condoms in Tompkins Square Park. One lady came up and took two condoms. I said ‘you can take more’ but she said ‘no, they’ll arrest me.’ She was scared to take them… she might have been 18 [years old]. [84] In May 2011 SAS co-hosted a forum with Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance to address criminal justice issues. Nearly 50 LGBT youth testified about the practice of police confiscating condoms and using them as evidence of prostitution and loitering for prostitution charges. [85] According to Andrea Ritchie, civil rights lawyer and activist and co-coordinator of SAS, LGBT youth are primary targets of HIV prevention efforts, including condom distribution in schools, drop-in centers, and communities. At the same time, they make up a disproportionate number of homeless youth and are subject to intense policing practices in public spaces as a result…They are routinely profiled as being engaged in prostitution-related offenses and subjected to NYPD stop-and-frisk practices. This all adds up to a lethal combination where condoms are confiscated and used in evidence, undermining public health efforts and criminalizing LGBT youth. [86] Although not the focus of this report, police interference with condom possession among LGBT youth in New York City merits further investigation. |

Documentation of Condoms as Evidence from the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene and the Urban Justice Center/PROS NetworkIn the summer and fall of 2010 the Sex Worker Project of the Urban Justice Center and the PROS Network assisted the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH) in conducting a survey of sex workers in New York City to assess the prevalence of the practice of police using condoms as evidence of prostitution. The findings of this survey were not released publicly, even to the PROS Network, until Human Rights Watch obtained a redacted version in February 2012 by filing a request under the New York Freedom of Information Law. The results indicated that of 63 individuals surveyed, 81 percent had been stopped and searched by a New York City police officer; 57 percent had had condoms taken away from them by a New York City police officer; and 29 percent said they had at one time not carried condoms because they were afraid of trouble with the police. When this group was asked to explain what about the police made them fear carrying condoms, statements ranged from their own experiences with arrest, hearing that condoms could cause you to be marked as a prostitute, and the potential embarrassment of having condoms seized.[87] On the basis of this report, DOHMH included the issue of using condoms as evidence in their 2011 Enhanced Comprehensive HIV Prevention Plan (ECHPP) submitted to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in March 2011, noting their support for current legislation pending in the New York State legislature that would prohibit the use of condoms as evidence of prostitution, and stating that discussions with the New York City Police Department about the issue were “underway.”[88] However, in an interview with the New York Times published on April 24, 2012, a spokesperson for the DOHMH stated that the department had reversed its position: After the Commissioner reviewed the study, which found that the current law has not resulted in sex workers consistently failing to carry condoms because of fear of arrest, he decided not to support the legislation. We have seen no evidence that the current law undermines the public health aims of condom distribution.[89] The Sex Worker Project of the Urban Justice Center and the PROS Network followed up on these findings with additional surveys taken in the fall of 2011. In a report released on April 17, 2012, the two organizations reported that 74 percent of the 35 sex workers surveyed had been stopped and searched by the police, and 46 percent of sex workers surveyed had at one time not carried condoms due to fear of the police. Fifteen sex workers reported having had condoms confiscated by the police, with six of these individuals reporting that they continued engaging in sex work after the confiscation. Of these six sex workers who engaged in sex work after the confiscation, three did not use protection.[90] |

Response of New York City Public Officials

Human Rights Watch requested interviews with the New York City Police Department, the District Attorneys in each of the four boroughs addressed in this report, and the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene.

The NYPD “respectfully declined” to meet with Human Rights Watch.[91] The New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene did not respond to repeated written requests for an interview.[92] As of May 2012, only the Manhattan and Queens District Attorneys had granted our request for interviews, though the Manhattan District Attorney’s office has not scheduled an interview as of this writing. The Bronx District Attorney’s office replied that, “we have not seen cases where such evidence [condoms used as evidence of prostitution-related offenses] was collected or used. Accordingly, at this time there seems to be no reason for a meeting,” but failed to respond to subsequent requests to clarify this statement.[93] The Brooklyn District Attorney failed to respond to a request for an interview, but has publicly expressed its opposition to proposed legislation prohibiting the use of condoms as evidence.[94]

In the view of the office of the Queens District Attorney, condoms are useful items of evidence in prostitution-related offenses, and banning condoms as evidence “would seriously damage our cases.”[95] The office emphasized the importance of using condoms as evidence in sex trafficking and promoting prostitution cases in which the alleged prostitutes, mostly women, are victims of criminal exploitation. Lois Raff, Counsel to the Queens District Attorney, stated,

We spend a lot of focus on going after pimps and sex traffickers for promoting prostitution, kidnapping, and sex trafficking. In that context as well, condoms may be one way the pimp will facilitate prostitution, by providing them.[96]

The Queens District Attorney stated that condoms were useful in efforts to close brothels and other businesses engaging in prostitution such as nail salons, hotels, and residences. “A large number of condoms will be evidence in these cases,” said Ms. Raff.[97] Their office currently has seven sex trafficking cases and 65 cases for promoting prostitution, internet crimes, and illegal massage parlors pending disposition. With regard to sex trafficking and promoting prostitution, they estimated that condoms were part of the evidentiary basis for the prosecution in two of these cases.[98]

The NYPD “Stop-and-Frisk” PolicyIn New York City, police stops and searches of sex workers, and those profiled to be sex workers, can be placed in the larger context of questionable police policies for stopping and searching persons without suspicion of criminal activity. The US Constitution and New York State Law permit an officer to stop an individual temporarily if the officer has reasonable suspicion that the individual is committing or has committed a crime, and to frisk the individual for a weapon if the officer reasonably suspects that he is in danger of physical injury. [99] A pending federal lawsuit, Floyd v. City of New York, challenges the NYPD’s “stop-and-frisk” practices, claiming that a substantial number of the nearly 700,000 annual stops and frisks by the police lack adequate grounds for reasonable suspicion, are racially motivated, and are unlawfully targeted toward black and Hispanic New Yorkers.[100] Although not specifically focused on stops and frisks enforcing anti-prostitution or loitering laws, plaintiffs in Floyd have submitted extensive evidence that an NYPD policing policy based on quotas for stops and arrests is a driving force behind many of the stops and frisks.[101] This policy, described officially by NYPD as “minimum thresholds for performance,” but as “quotas” by current and former officers, rewards a certain number of street stops per week.[102] It is not clear how many stops on suspicion of sex work are recorded as “stops and frisks,” but many of the neighborhoods where stops and frisks occur on a regular basis are the same neighborhoods where sex workers are frequently stopped. Jackson Heights, Queens, for example, the location of much of the harassment of Latina transgender women documented in this report, has the third-highest rate of stops and frisks in the city.[103] In New York City, failure to respect the right of sex workers, transgender women, and LGBT youth to liberty and security of the person is part of broader human rights concerns raised by practices of the NYPD. |

Washington, DC

HIV in Washington, DC

The HIV epidemic in Washington, DC is one of the most severe in the United States. The overall prevalence of HIV in the District is three times higher than the one percent designated by the World Health Organization as a generalized epidemic.[104]Washington, DC has the highest AIDS diagnosis rate and the second-highest rate of new HIV diagnosis among major metropolitan areas in the United States.[105] Half of the District of Columbia population is African-American.[106] Of the 17,000 persons living with HIV, however, 75 percent are African-American. Most people living with HIV in Washington, DC are males (72 percent), but black women in DC are 14 times more likely to be living with HIV than white women.[107] Sex between men is the most frequent mode of transmission, responsible for 38 percent of all living cases of HIV/AIDS, with 27 percent of people living with HIV/AIDS reporting infection through heterosexual contact and 16 percent through injection drug use.[108]

The District of Columbia’s response to HIV came under heavy criticism in the last decade. In 2005 the non-profit public policy organization DC Appleseed Center for Law and Justice released a comprehensive critique of the city’s failure to adequately budget, plan, and confront the HIV epidemic in the District. The report called for sweeping reforms in infrastructure, coordination, and resources for surveillance, prevention, care, and services.[109] That same year the HIV Prevention Planning Council for the District appealed to the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to intervene in the city HIV and AIDS office as it was missing federal deadlines for developing and reporting crucial epidemiological data for the city.[110]

Major changes followed these reports, including a new director for the HIV program and an organizational restructuring in the District of Columbia Department of Health. Every year since the initial report, DC Appleseed has issued a report card on the District’s efforts in the battle against AIDS. The most recent report card indicates that substantial progress has been made in many areas, confirmed by Department of Health data showing a decrease in the HIV prevalence to the current figure of 3.2 percent, a decrease in new AIDS cases, a testing program that nearly doubled the number of HIV tests, and a significant decrease in deaths from AIDS.[111]

City government in the District of Columbia has demonstrated a commitment to improving its response to the HIV epidemic, and HIV remains a focus of the current administration. In 2011, Mayor Vincent Gray appointed a Mayor’s Commission on HIV and AIDS in order to “help end the HIV epidemic in the District of Columbia by focusing on treatment, the needs of people living with AIDS, and the prevention to stop new infections.”[112] The Commission will bring together medical providers, academics, faith-based community members, and members of government to make recommendations on best practices for improving care, services, and prevention programs. In July 2012 the city will host the 19th Annual International AIDS Conference, where the epidemic and the response of the District will be in the spotlight.

One area of marked improvement is condom distribution in the District of Columbia, where four million condoms were distributed in 2010 compared to 115,000 in 2006.[113] The Rubber Revolution, part of the District of Columbia’s HIV prevention program, uses the internet and other social media to encourage condom use. The Rubber Revolution website says,

Today is the day that you join the Rubber Revolution, a new movement in DC to take condoms out of hiding. We want to get those rubbers out of your wallet, remove them from your purses and pull them out from under the beds of every ward in the city. We want condoms in the hands of the men and women of DC to use for responsible and good sex. We are creating a movement of people who are committed to getting and using condoms. No longer will we have to hide condoms.[114]

Anti-Prostitution Enforcement in Washington, DC

Washington, DC law prohibits engaging in or soliciting prostitution, an offense defined as “a sexual act or contact with another person in return for giving or receiving a fee.”[115] Penalties range from a fine of not more than US $500 and/or 90 days in jail for a first offense to a possible two year jail sentence for the third offense.[116]

In 2005 the DC Council enacted the Omnibus Public Safety Act that provided for the declaration of “Prostitution-Free Zones” (PFZ) by the Metropolitan Police Department (MPD). Under this statute, the MPD may designate an area a PFZ on the basis of “disproportionately high” arrests for prostitution or calls for police service related to prostitution in the locale in the previous six month period, or “objective evidence or verifiable information” indicating that a high incidence of prostitution is occurring in that locale.[117]

Within the PFZ police may arrest or disperse persons determined to be engaging in or soliciting prostitution, based on a range of behaviors and factors similar to those enumerated in New York City’s loitering for prostitution laws. These include not only conduct such as flagging down cars and conversing with passers-by, but being a “known participant in prostitution or prostitution-related offenses.”[118] In addition, in the PFZs police may arrest two or more persons who are “reasonably believed” to be congregating for the purposes of prostitution and who fail to disperse when ordered to do so.[119] The declaration of a PFZ can last as long as 480 consecutive hours after notice is posted in the area by the MPD.[120]

Although prostitution is unlawful throughout Washington, DC, the broadly drawn loitering laws that permit arrest based on a range of circumstantial evidence are enforceable only within an officially declared PFZ. This statute was immediately controversial, drawing opposition from a broad spectrum of community groups and civil liberties advocates.[121] No legal challenge, however, has ever been filed, primarily because MPD has never made an arrest for failure to disperse under the PFZ statute, leaving its legality untested in the courts.[122]

The MPD practice of dispersing people from the PFZs was the subject of advocacy in the sex worker and transgender community. Police profiling of transgender persons as prostitutes was a significant factor in organizing the transgender community to push for the addition of transgender and non-gender conforming people to the city’s Human Rights Act in 2005.[123] After two years of negotiation between the transgender community and the MPD, the MPD issued guidelines for members of the police force addressing their interaction with transgender individuals that includes a prohibition on profiling transgender persons as sex workers:

Members shall not solely construe gender expression or presentation as reasonable suspicion or prima facie evidence that an individual is engaged in prostitution or any other crime.[124]

In January 2012 the DC Council considered a bill sponsored by Councilwoman Yvette Alexander to expand the prostitution-free zones.[125] The new bill would have permitted the MPD to declare a PFZ on a permanent basis for an unlimited period of time. Between 2009 and 2012, arrests for prostitution-related offenses decreased by nearly 50 percent, from 1,695 in 2009 to 845 in 2011.[126] In testimony before the Committee on the Judiciary regarding the bill, Assistant Chief of Police Peter Newsham opposed expansion of the PFZs, explaining that they had little to do with the drop in prostitution arrests in recent years. Chief Newsham stated that the PFZs had not reduced prostitution in the District in a meaningful way, rather subjecting it to “temporary displacement.”[127] He noted that prostitution complaints from citizens as well as arrests had steadily decreased in the last several years, a decrease he attributed to several factors other than the PFZs, including the movement of many prostitution activities indoors and onto the internet. With regard to street prostitution, he stated that in his experience, many people engaging in this type of prostitution are drug dependent or have mental health problems, and “this is not a problem we can arrest our way out of.” Chief Newsham urged an increase of social services to the population engaged in prostitution.[128]

The Office of the Attorney General for the District of Columbia also testified against expansion of the PFZs, noting that the original PFZ legislation was vulnerable to constitutional challenge and the expansion bill was even more likely to be found unconstitutionally vague.[129] The proposed legislation was returned to the Committee by the Council as whole for reconsideration and as of June 2012 had not been enacted.[130]The original PFZ legislation remains in place.

Condoms as Evidence of Prostitution

In Washington, DC, sex workers told Human Rights Watch that condoms were used as part of police stops on suspicion of prostitution.

Stops and Searches for Condoms

In Washington, DC as in other jurisdictions a lawful stop requires reasonable suspicion of criminal activity and lawful searches must be based on probable cause for arrest on a specific charge.[131]Every stop, however, does not result in arrest, and most stops reported to Human Rights Watch consisted of police questioning, searching, and demands to “move along” without resulting in an arrest. It was during these encounters that sex workers were most frequently targeted for carrying condoms during enforcement of the anti-prostitution laws.

Annie P., an African-American transgender woman who used to be a sex worker told Human Rights Watch,

I stopped tricking three years ago. But when I walk through the old neighborhood where my boyfriend still lives, I get stopped by the police who think I am still working. A few months ago I had been visiting my boyfriend and I had three condoms still on me. The police stopped me, asked me to empty my pockets, and asked me why I was carrying so many condoms. I said ‘cuz that’s how many times me and my boyfriend do it.’ But he didn’t believe me, and made me wait while he looked to see if there were prostitution charges against me. Since I didn’t have any recent ones he let me go.[132]

Cassandra A., a transgender woman and sex worker, stated,

I was stopped at 4th Ave and Rhode Island Avenue. I and a friend had gotten a ride to the store, and we were stepping out of the car when some vice cops rode up. They were looking for drugs or something so they patted us down and asked me why I was carrying a condom and asked was I tricking? ‘Are these guys your pimps?’ And I said no and we didn’t have any drugs so they let us go. This happens all the time that they ask about the condoms you are carrying, if you are a known prostitute it is one of the basic questions asked by the cops when they stop you.[133]

Lee H., an African-American sex worker, also said that police frequently target condoms during stops:

Three months ago in the downtown area I was stopped by the cops. They told me to put my hands on the police car and they searched my purse. They asked me why I had so many condoms. I had 15 condoms in my purse, and if you have more than two condoms they think you are a sex worker. I told them it was not their business how many condoms I had. I said I might be out here giving it away but I’d rather have too many than not enough. It’s not for them to tell me how many condoms I can have… This was the 3rd or 4th time this happened to me in DC.[134]

Zinnia F., a transgender sex worker in the downtown area said,

Yes it happens, they say ‘why do you have so many condoms?’ No one walks around with a lot of condoms because of it. It happened to me two times, once last summer. This was in the K street area.[135]

Felicia C., a sex worker in Columbia Heights, told Human Rights Watch,

Oh yes, at 14th and Perry, on the 26th of December, the cops harassed me and told me to throw my condoms in the garbage. I told them ‘no I am not throwing them in the garbage! I don’t want to die!’[136]

Outreach workers also said that sex workers express a fear of being found by police in possession of condoms. Jenna Mellor, Director of Outreach for HIPS (Helping Individual Prostitutes Survive) runs the mobile outreach van that provides condoms, clean syringes, and other harm reduction materials to sex workers several times per week. Mellor told Human Rights Watch,

Fear of taking condoms is a real problem. Clients take fewer condoms than they need because they fear the police. They also hide condoms in their clothes, their wigs, their cleavage, in order to avoid being hassled by the police.[137]

Mellor also said that generally police are tolerant of the outreach van, but there have been occasions when police cars have followed the van. Recently, a police car waited for a transgender individual to visit the van, and then the officers got out of the car and stopped and searched her: “Some police are supportive and leave us alone, but it is by no means 100 percent supportive.”[138]

Monica B. facilitates the transgender support group at HIPS and does outreach to sex workers to let them know about the group:

Three months ago I was in the downtown area doing outreach. I give out condoms and let people know about the [HIPS] program. The cops stopped me and went through my bag, asked me what am I doing with all these condoms? I explained that I was an outreach worker and promoting my group. They did not arrest me but they sure gave me a hard time.[139]

Lina C., an African-American transgender sex worker, described a recent experience while “on the stroll” (an area where sex work regularly occurs):

Last summer I was on the stroll. I had just left the [HIPS] truck and they asked me why I had so many condoms. I said I had just come from the truck. They asked me my history, whether I had ever been arrested in the past. They also approached the truck to verify my story. They didn’t arrest me but they harassed me for 45 minutes.[140]

Some sex workers referred to a “3-condom rule” in the District of Columbia. Nila R. told Human Rights Watch that she received that information from a police officer:

In 2011 they locked me up in the 5th district. The cop told me I could have three condoms and threw the others out, I had ten altogether. Also, an open condom is a charge. I’ve been locked up for it, the cops told me they were locking me up for an open condom.[141]

Madison M., a sex worker interviewed at a motel in the northeast section of the city, stated,

I haven’t been hassled myself, but I heard there was a rule that you can only carry three condoms.[142]

Abuse of Transgender Women by Police

Transgender women were the majority of those we interviewed who complained about stops and searches for condoms, and their testimony described abusive behavior by police.

Jody B., a 23-year-old female-to-male transgender person stated,

The police ask constantly, ‘how much are you charging?’ In October I was coming out of the China theater in Chinatown on a date with my boyfriend. They stopped both of us, searched me, I had condoms in my purse. We talked our way out of it so they did not arrest us. Us transgenders, we get used to not reporting these things. It’s hard; I’m stepping back from being full-on transgender, because it’s hard.[143]

Lina C. said that police encounters were often traumatic:

I was arrested last year and it was humiliating. They defaced me. They took off my wig and stomped it on the ground, then handed it back to me when they put me in the car.[144]

Monica B. stated that in her outreach work she has observed this “defacing” behavior and other abuse occurring during police stops:

The police are often extorting for sex, taking out people’s falsies and dropping them on the street, this does not happen every day but it happens regularly.[145]

Response of Washington, DC Public Officials

Assistant Chief of Police Peter Newsham expressed concern that the police were discouraging the use of condoms among sex workers or any other member of the public. He said that condoms could be used as supplemental evidence collected “incident to arrest.” He explained that in Washington, DC, prostitution cases are not a high priority and that arrests that are made are usually “complaint-driven,” meaning members of the public have complained about activity in their neighborhoods. According to Chief Newsham, the emphasis is now on pimping and human trafficking cases, and the priority is to charge those who are exploiting the women involved. Chief Newsham asserted that condoms may be helpful as supplementary evidence in these cases and will continue to be collected at the scene.[146]

Further, Chief Newsham emphasized that searches must be made only if there exists probable cause for arrest. He was concerned to hear that people reported being stopped and searched in circumstances that suggested a lack of probable cause. He also expressed concern that transgender individuals were alleging “profiling” and other abuse, and asked if they had filed complaints. When hearing that people often feared filing police complaints, he emphasized that there were anonymous ways to make complaints and agreed to ensure that community members were aware of these methods.[147]

Chief Newsham expressed his concern that police were “editorializing” about condoms in a manner that conveyed a threat to arrest sex workers for possession of condoms. Newsham agreed to consider issuing guidelines prohibiting such commentary and to underscore for MPD officers the importance of encouraging condom use. He agreed to meet with public health and other city officials and members of the sex worker community to discuss steps that can be taken by MPD to address all of these issues.[148]

Judge Linda Kay Davis, the judge in the special “prostitution docket” of the Criminal Court said that in two years of presiding over individual prostitution cases she had never encountered condoms presented as evidence in her court.[149]

The US Attorney had no comment on the issue of condoms, or any other evidence in their cases, as a matter of policy.[150]

The Washington, DC Department of Health responded with concern to the findings of this report and agreed to consider proposals from community organizations for action before the International AIDS Conference.[151]

Los Angeles

HIV in Los Angeles

Los Angeles County is a sprawling area that is home to nearly 10 million people.[152] The County includes the City of Los Angeles and numerous smaller cities. Los Angeles County is the entity for which HIV and AIDS statistics are collected by the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health (LADPH) and the entity to which HIV funding is provided by the federal government.[153] In Los Angeles County, 59,500 persons are estimated to be living with HIV.[154]Forty percent of people living with HIV in Los Angeles County are Latino.[155] In 2012, 80 percent of new HIV diagnoses occurred in men who have sex with men and 11 percent in those who reported heterosexual contact. Among women, Latina women had the most new HIV infections (42 percent) compared to 39 percent in African-American women and 14 percent in white women.[156]

According to LADPH there are an estimated 926 transgender persons living with HIV in Los Angeles County.[157] The rate of HIV infection is difficult to determine because the size of the transgender population as a whole is uncertain.[158] Nevertheless, Los Angeles has a large and vibrant transgender community, and HIV infection is one of its greatest concerns. In 2001 several community organizations partnered with the LADPH to publish a study of transgender health.[159] The authors noted the lack of data concerning the health of a “marginalized and underserved population” and surveyed 244 male-to-female transgender persons.[160]

The 2001 LADPH report found a 22 percent HIV prevalence among the group, many of whom were not aware of their infection. Half of the participants had an annual income of less than $12,000, and half also noted that their primary income was derived from sex work. Despite a high level of knowledge about HIV transmission, condom use was inconsistent, with 29 percent of people who had exchanged sex for money or other goods in the last six months stating that they did not always use a condom. Thirty-seven percent reported verbal abuse or harassment by the police. The report concluded, among other recommendations, that HIV prevention programs tailored to transgender women in Los Angeles were “urgently needed.”[161]

Another transgender needs assessment conducted by LADPH in 2007 found that of 80 transgender persons surveyed, one in five was HIV-positive. Numerous factors associated with high HIV risk were identified, including sex work, unemployment, and transphobia. One-third of transgender persons surveyed had traded sex for money or other goods. The needs assessment was cited in the LADPH HIV Prevention Plan for 2009-2013, with the conclusion that transgender persons were a “priority and critical target population” for HIV prevention in Los Angeles.[162]

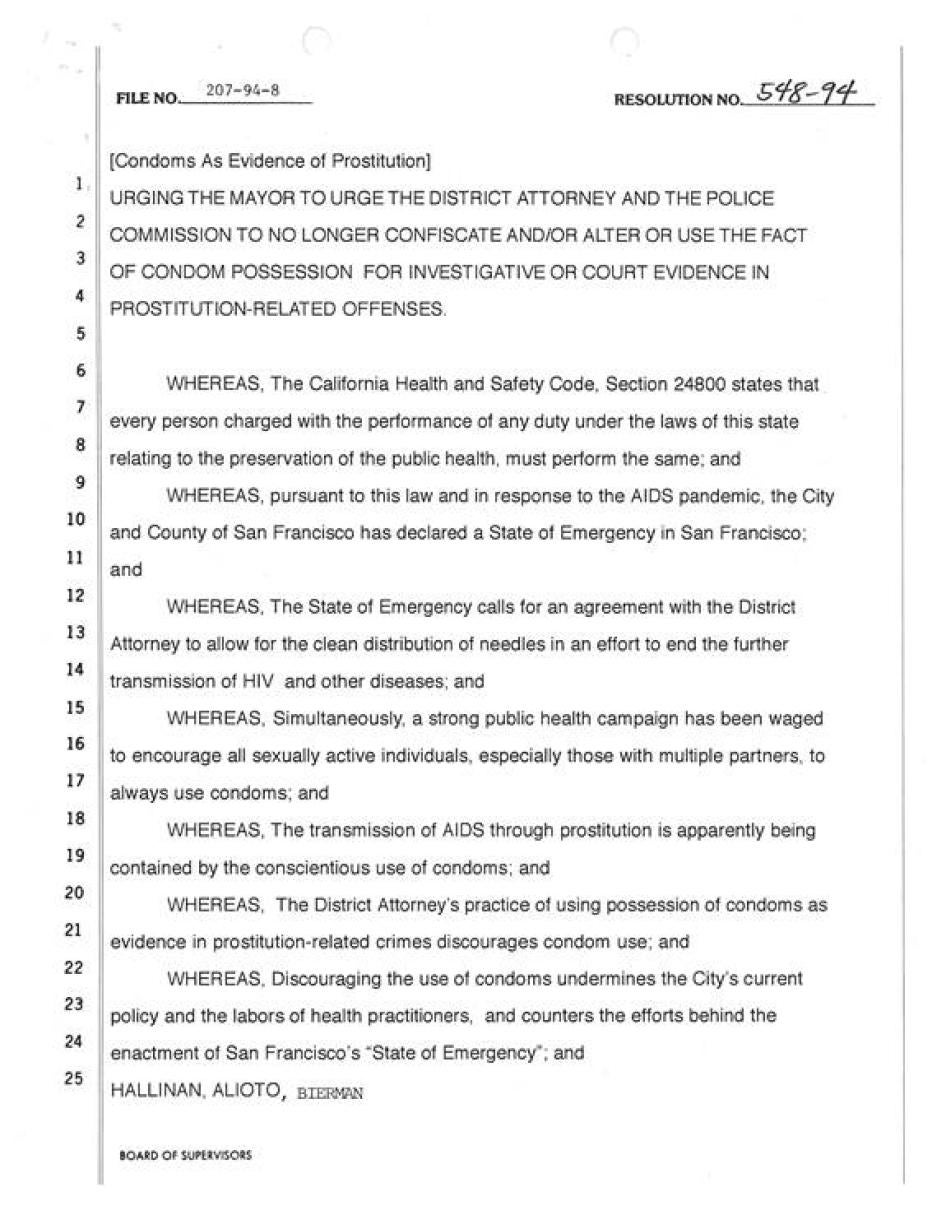

Increased condom distribution to high-risk groups is also a top priority for Los Angeles County Department of Public Health. Along with New York, Washington, DC, and San Francisco, Los Angeles is a participant in a funding initiative of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), focusing on high prevalence urban centers as part of its implementation of the National HIV/AIDS Strategy. (Although the program is called the “12-cities” program, the entity receiving federal funding is the County of Los Angeles).[163]One of the required HIV prevention interventions for all “12-cities” program participants is increased condom distribution to high-risk populations. Los Angeles plans to accomplish this goal by increasing distribution to high-risk populations and by marketing a Los Angeles-branded condom.[164]