Hidden in the Mealie Meal

Gender-Based Abuses and Women's HIV Treatment in Zambia

I. Summary

I started [HIV] medication in 2006.[My husband] does not know.I take the medicine out of a bottle and put it in a plastic [bag] or in a paracetamol box . Sometimes I would miss a dose; he comes back at 18:00 hrs, drunk, closes the door and says, "Today you are going to freak out."He locks [me] in, he beats me up and locks me out of the house . I go to the neighbors, if they have mercy they will let [me] in, if not, [I] sleep under a tree until tomorrow.As a result of that I miss doses sometimes.I feel very bad. I don't even feel like taking the medicine.

-Berta K., Lusaka, February 3, 2007

Zambia is one of many countries setting ambitious targets for rapidly scaling up antiretroviral treatment for HIV/AIDS and is making impressive progress. It is addressing a range of obstacles to treatment and receiving substantial donor support to overcome them. However, women's unequal status in Zambian society gravely undermines their ability to access and adhere to antiretroviral treatment (ART), and the government is paying little if any attention to the gender dimension of treatment, especially the impact of entrenched discrimination and gender-based violence and abuse.

Women in Zambia report that gender-based human rights abuses are, in fact, very real barriers to accessing and adhering to treatment.HIV programs, activists, and policy makers are increasingly recognizing that discrimination and violence against women must be addressed if the world is to combat the AIDS pandemic.But treatment policies and programs still tend to ignore the connection between domestic violence or women's insecure property rights and their ability to seek, access, and adhere to HIV treatment.Although the Zambian government has taken some steps to address violence and discrimination against women generally, major gaps remain in legislation, HIV treatment programs, and support services to address poverty among women living with HIV/AIDS. This must change if HIV treatment is to be provided equitably and to succeed in saving women's lives.

Human Rights Watch investigated the negative impact of gender-based human rights abuses on women's access and adherence to HIV treatment in two provinces in Zambia, Lusaka and the Copperbelt, in 2006 and 2007. Women there told Human Rights Watch how beatings and rapes by their intimate partners, emotional and verbal abuse, loss of property upon divorce or death of a spouse, and fear of such abuses affected their access and adherence to HIV treatment. The abuses thwarted their ability to seek HIV information and testing, discouraged them from disclosing their HIV status to partners, delayed their pursuit of treatment, and hampered their ability to adhere to HIV treatment regimens. Many women, fearing abuse or abandonment, fabricated excuses for their absence from home during clinic visits or support group sessions and hid their medication in flower pots, holes in the ground, food containers, and elsewhere. Many struggled to find money for food, transport to clinics, and diagnostic tests, especially those whose property was taken when divorced, abandoned, or widowed. Some missed doses as a result. The strain took a toll on many, like Berta K., who told us that due to repeated abuse by her partner, "I miss doses sometimes. I feel very bad. I don't even feel like taking the medicine. I say, 'Ha, let me die.'"

Though gender-based abuses have seriously undermined their ability to get HIV treatment, most of the women Human Rights Watch interviewed said their difficulties are simply not discussed in the clinics where they go for HIV counseling or medicine. With few exceptions, health care providers did not raise the issue.Some of the institutions that train HIV counselors in Zambia told us "gender is integrated" into their training. Yet most of the dozens of HIV counselors Human Rights Watch interviewed said they do not screen for gender-based abuses, offer referrals for services, discuss safety strategies with patients, assess how this impacts treatment, or otherwise address the abuses. Treatment adherence counselors said they count women's remaining pills and discuss certain other obstacles to adherence, but not gender-based abuses. Almost all, however, expressed willingness to start dealing with these abuses with proper training and support.

There is perhaps no better place than Zambia to create a model approach to responding to gender-based human rights abuses within HIV treatment programs as part of an overall strategy to prevent and address these abuses. Situated in Southern Africa, the region most affected by the pandemic, 17 percent of Zambia's adult population is living with HIV/AIDS, and of these, 57 percent are women. Zambia also has high rates of gender-based violence.Recent surveys have found that more than half of women surveyed reported beatings or physical mistreatment since age 15, and one in six women reported having been raped.

On the positive side the government has enacted laws to protect women's property rights, has established specialized police units to address gender-based abuses, and in 2006 appointed a cabinet minister for gender and development. Civil society organizations provide services for women survivors of abuse and adults and children living with HIV/AIDS. The country has high-level governmental and multi-sectoral bodies working on HIV/AIDS, and is commended globally for its fight against the epidemic. It has pledged to make HIV treatment and related tests free in the public health system and has increased the number of people on treatment over 30-fold in five years. However, almost half of all individuals in need of treatment are still not getting it. Increasing donor support for its HIV/AIDS response puts Zambia in the spotlight, including as one of 15 focus countries for the United States President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief.

Zambia has also ratified major regional and international treaties that require the government to eliminate violence and discrimination against women and to guarantee their rights to health, physical security, non-discrimination, and life. It has also committed to fulfill the United Nations (UN) Millennium Development Goals, which include promoting gender equality, empowering women, and combating HIV/AIDS. To safeguard women's rights and dignity, and to ensure the success of HIV treatment programs, Zambia must turn these commitments into concrete action.

Human Rights Watch calls on the Zambian government to strengthen its response to HIV/AIDS by safeguarding women's human rights, ensuring equitable access to antiretroviral therapy (ART), and providing women on ART access to healthcare services designed to help them deal with gender-based abuses as part of their treatment.In this effort the Zambian government should act urgently to enact and enforce legislation on sexual and gender-based violence.The government should ensure that the new constitution currently under debate guarantees women's equality in all respects, including matters relating to personal and customary laws.And the government should ensure that health care providers working in the areas of HIV/AIDS and ART receive adequate training, clear guidelines, and support to detect and address gender-based abuses. It should improve health care infrastructure, including by ensuring that HIV counseling occurs in a private setting, where women and their healthcare providers can discuss the existence or risk of gender-based abuses.

Donor agencies should support these reforms as a priority, endorsing them as a necessary component of effective treatment for women with HIV/AIDS.

This is a dynamic moment of opportunity and risk in the global fight against HIV/AIDS. Governments and international agencies are pressing to achieve universal access to HIV prevention, treatment, care, and support by 2010. Donors are spending tens of billions of dollars to support HIV treatment.The number of individuals on HIV treatment worldwide jumped from 400,000 in 2003 to more than two million in 2006, and millions more will seek testing for HIV infection and start treatment in the next few years. Without urgent attention to gender-based abuses, Zambia will not realize the potential for these efforts, and the lives of many women will be at risk.

II. Key Recommendations to the Government of Zambia and Zambia National Assembly

To the President of the Republic of Zambia

- Publicly denounce gender-based abuses, including gender-based violence, property grabbing, and unequal distribution of marital property upon divorce, and emphasize the harmful effect of these abuses on HIV treatment.

- Publicly express support for initiatives to redress gender-based abuses.

To the Zambia National Assembly

- Ensure that as the draft constitution is finalized, provisions on equality before the law regardless of sex, and provisions prohibiting any law, culture, custom, or tradition that undermine the dignity, welfare, interest or status of women or men are retained in the final version.

- Adopt specific legislation to prevent and remedy sexual and domestic violence. This should include civil and criminal judicial remedies, and the provision of services to survivors.

To the Ministry of Justice and the Gender in Development Division

- Support efforts to review and transform discriminatory aspects of customary law.

To the Cabinet Committee on AIDS, the National AIDS Council, the Ministry of Health, and the Gender in Development Division

Facilitate the establishment and implementation of programs in the healthcare system to address gender-based abuses, as follows:

Establish a multi-sectoral taskforce that would study different models for addressing gender-based abuses in health settings (see Appendix II), devise a model that is effective and appropriate for Zambia, pilot it, and implement it in the nine provinces.

Integrate initiatives addressing gender-based abuses, especially gender-based violence, into ART and HIV programs.

Ensure that HIV treatment adherence counselors integrate screening for and handling of gender-based violence in counseling, establish protocols on detecting and addressing gender-based violence, and provide continuous supervision and support for counselors to assist them in doing so.

To the Ministry of Health and the Zambia Counseling Council

- Ensure that institutions providing training for HIV counselors cover the issues of gender-based violence, lack of legal protection for women's property rights, and other gender-based abuses and their effect on treatment in training courses.

To the Ministry of Health

- Monitor and document the impact of gender-based abuses on ART in on-going research on ART in Zambia.

To the Gender in Development Division

- Lead on the development of a campaign that emphasizes women's right to decide when, where, and how to seek health services, including access to HIV testing and treatment programs.

To the Ministry of Home Affairs

- Ensure the provision of adequate resources and training for the Victim Support Unit (VSU) including vehicles, sexual crime kits, stationery, and appropriate training and supervision for all VSU officers.

To The Ministry of Community Development and Social Services

- Establish shelters and other relevant services for survivors of gender-based violence in all provinces, and provide additional funding for existing Young Women's Christian Association shelters.

III. Methodology

This report is based on field research conducted in January and February 2007 and in May 2006 by a Human Rights Watch researcher and a consultant.

Human Rights Watch conducted one-on-one interviews with 83 women living with HIV/AIDS, most of whom were survivors of domestic violence or have experienced property grabbing or loss of marital property upon divorce. Many of the women were on antiretroviral therapy (ART). Their ages ranged from 17 to 74, with the majority between 25 and 55 years. One interviewee testified on behalf of her bed-ridden sister. We also conducted two mixed-gender focus group discussions and one women-only focus group discussion with members of HIV support groups in Lusaka and Chongwe. We identified and contacted informants through women's groups and HIV support groups and organizations, and also used the snowball technique where women we interviewed introduced us to other women in their social networks or support groups whose experiences were relevant to our research.The interviews took place in private rooms at NGOs premises, informants' houses, support groups meeting rooms, and in a meeting room at a hotel.

Interviews were conducted in English, Bemba, and Nyanja with the help of two female professional translators and a female coordinator of a support group. Prior to each interview we informed participants of the purpose of the interview, its voluntary nature, and the way in which the data would be collected and used. Researchers assured participants of confidentiality and obtained informed verbal consent from them. Care was taken with survivors to ensure that recounting their experience did not further traumatize them or put them at physical risk. We provided each interviewee with a list of local nongovernmental organizations and clinics that provided relevant services.

Human Rights Watch also interviewed over 25 HIV/AIDS counselors and nurses, in addition to representatives of nongovernmental organizations specializing in women's rights, HIV/AIDS or development, faith-based groups, and traditional health practitioners. At the governmental level we interviewed representatives from the Ministry of Health, the National AIDS Council, the Gender in Development Division, the Ministry of Finance, the Ministry of Justice, the Zambia Permanent Human Rights Commission, and the Victim Support Unit of the police. We also interviewed the First Lady of Zambia, bilateral donors, the World Bank, and UN agencies. Researchers conducted several follow-up phone interviews with government officials and healthcare professionals.

The research focused on the Lusaka and Copperbelt provinces, which have the largest number of adults and children living with HIV/AIDS and the most HIV treatment sites in Zambia. Apart from Kafue and Chongwe rural areas, our interviews took place mainly in the urban districts of Lusaka, Kitwe, and Ndola. Zambia is highly urbanized; the urban population has twice the infection rate of the rural population, and the most established treatment programs are in urban areas. Future research on HIV treatment barriers for rural women would be valuable.

A limitation to this research is that we mainly interviewed women connected to women's organizations and HIV support groups, or who attended adherence counseling. The experiences of women who are unable to access these services are likely to be more severe. Moreover, in terms of adherence, support group leaders and adherence counselors often emphasize that patients should take ART on time as prescribed by clinic staff. Women who have missed appointments to renew their prescriptions for ART reported that they were "told off" by clinic staff. Consequently, some of the women interviewed might have decided not to admit missing ART doses as they associated Human Rights Watch researchers with support group leaders or adherence counselors.

Another limitation is that we did not interview perpetrators, including husbands, intimate partners, and family members involved in property grabbing.

Unless stated otherwise, the names of women living with HIV/AIDS cited in this report have been disguised with names and initials (which do not reflect real names), in the interest of the privacy of the individuals concerned.

IV. Background

Gender and HIV/AIDS in Africa

More than twenty-five years after the first HIV cases were detected, Africa remains in the grip of a terrible epidemic.Millions of children have been orphaned and are at risk of abuse and exploitation, thousands of adults in their most productive years are dying every day, millions of others are sick, and countless others fear abandonment and even violence if they disclose their HIV status to family and friends.

Globally, 33.2 million people are living with HIV/AIDS.Of these approximately 15.4 million are women.[1]Sub-Saharan Africa remains the epicenter of the pandemic, with 22.5 million of all those with HIV living in this region, representing 68 percent of all infections.[2]

In Africa women with HIV outnumber men, constituting between 59 and 61 percent of all adults with HIV above age 15.[3]There is now a well established body of international and regional research that illustrates how gender inequalities fuel the epidemic and hamper efforts to prevent new infections among women.[4]Women's subordinate status within intimate relationships and their economic dependence on male partners make it difficult for them to negotiate safer sex and to use condoms consistently, for fear of being abandoned or assaulted.Concurrent relationships (or suspicion of concurrent relationships) in the age of HIV/AIDS often give rise to tensions that can result in domestic violence.[5]

The World Health Organization (WHO) has identified violence, including violence against women, as "a major public health problem in Africa."[6] Gender-based violence creates conditions conducive to the transmission of HIV to women, since women in violent relationships often experience coercive, violent sex and are unable to negotiate HIV prevention. Furthermore, some women may be unable to leave violent relationships because of their economic and psychological dependence on their abusers.Women's unequal property rights also contribute to the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the region.Under the laws and customs of many sub-Saharan African countries, women neither inherit nor keep property upon divorce on an equal basis with men.This reinforces their dependence on men, sometimes locking them in abusive relationships.This may also render women and their children destitute upon divorce or the death of their husbands.

Access and Adherence to Treatment

In 2003 2.1 million adults and children died of AIDS-related causes worldwide, the vast majority unable to pay for life-saving medication. At that time only 400,000 people in low- and middle-income countries were receiving antiretroviral therapy.[7]By December 2006 the reach of treatment had increased five-fold, to over two million, but even this figure represents only 28 percent of those who needed treatment.[8]Many adults and children still cannot access life-saving ART.Leaders of the Group of Eight (G8) and the United Nations General Assembly made commitments in 2005 and 2006 to work with the WHO, Joint United Nations Program on AIDS (UNAIDS), and other international institutions to move as close as possible to universal access to treatment by the year 2010.[9]This political commitment led to increased resources for HIV treatment programs, and in sub-Saharan Africa the scale-up of treatment has been dramatic.[10]

Despite these advances, governments and international health agencies point to several constraints in the delivery of and adherence to ART.These include the procurement and supply of drugs and equipment for diagnostic testing, limited human resources, limited capacity of healthcare systems, and lack of proper program management and monitoring systems.[11]These and other factors, such as food insecurity, poverty, lack of money for transport, stigma and discrimination, and direct and indirect user fees, are all factors that hold back the expansion of treatment programs. As Chapter V below shows, gender-based abuses substantially curtail women's ability to benefit fully from ART.In some cases women's enrollment in ART programs exposed them to domestic violence, and to abandonment and divorce, which coupled with insecure property rights, often exposed women to further impoverishment and even homelessness.If ART programs are not strengthened so that they take into account and help to address the impact of gender-based violence, lack of protection for women in family and property rights issues, and unequal relations between men and women in general, women will continue to miss out on life-saving treatment.

A high level of adherence is critical for the success of ART.According to the WHO, "adherence to ART is well recognized as an essential component of individual and programmatic treatment success."[12]Research on drug adherence has shown that "higher levels of drug adherence are associated with improved virological, immunological and clinical outcomes and that adherence rates exceeding 95 percent are necessary in order to maximize the benefits of ART."[13]Lack of adherence can lead to the development of drug resistance, which can lead to treatment failure among individuals and drug resistant strains of HIV can be transmitted to others during unprotected sex and other high-risk activity.[14]

Obstacles to Accessing HIV/AIDS Treatment in Zambia

In 2006 the prevalence of HIV in Zambia was about 17 percent (approximately 1.1 million people) among the 15 to 49 age group.[15] Women account for 57 percent of Zambians infected with HIV.[16]Girls and young women between ages 15 and 24 are four times more likely to be infected with HIV than their male counterparts.[17]

Despite increased knowledge of the importance of HIV counseling and testing, few Zambian women and men know their HIV status.[18]According to the most recent Zambia Sexual Behavior Survey (2005), although 80 percent of Zambian women and 83 percent of Zambian men stated that they knew a place where they could have an HIV test,[19] the percentage of Zambians who had ever been tested remained low.In 2005 the percentage of Zambian women and men who had ever been tested was 15.3 percent and 11.4 percent respectively.[20]Fear of learning the result, fear of stigma and discrimination, and lack of adequate health facilities are all factors contributing to the low percentage of people aware of their HIV status in Zambia.[21]Gender-based abuses and the fear of such abuses also determine women's decisions to access HIV testing.

In 2004 the Zambian government introduced free access to ART in the public health sector for those who need it, and in June 2005 the government declared that the whole ART service package would be available free of charge in the public health sector.[22]It appears, however, that this policy is not being uniformly applied in the two provinces studied for this report.Interviewees in Ndola, in the Copperbelt province, indicated that they only receive antiretroviral medicine free of charge, and must pay for CD4 countsand other diagnostic tests.[23]As the testimonies in Chapter V indicate, the cost of these tests is prohibitive for women with insecure property rights and also severely impacts women in abusive relationships.

In January 2004 only 1,483 people were accessing HIV treatment in Zambia. By November 2005 an estimated 43,964 people living with HIV were accessing antiretroviral drugs through 53 public health facilities throughout the country.[24] At the end of 2006 the number had increased to 75,000 and the number of sites to 110.[25]According to PEPFAR, by September 2007 the number of people receiving HIV treatment in Zambia had increased to 122,700.[26]

In 2006 61 percent of those accessing treatment were women.[27]Women are more likely to know their HIV status through antenatal healthcare services, Prevention of Mother to Child Transmission of HIV (PMTCT) programs, and through seeking pediatric medical assistance when a child is ill.However, the slightly higher percentage of women accessing HIV treatment raises the risk of complacency where healthcare providers and other stakeholders may overlook the serious hindrances to women's access and adherence to HIV treatment such as those discussed in this report.

The US President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (the Global Fund) are the largest funders of HIV treatment in the country.Zambia is one of PEPFAR's 15 focus countries, and received support from the Global Fund in rounds one and four (see Chapter VIII).

HIV has placed enormous pressure on a public health system that was already struggling to serve Zambians while only committing approximately US$51 per capita per year for health services.[28]The Zambian government has identified a number of barriers to improving the healthcare system.These include a "human resource crisis," the poor state of health facilities, inadequate drugs and medical supplies, long distances to and between health facilities, poor transportation infrastructure, and high-levels of poverty.[29]Similarly, PEPFAR has identified several limitations within the health system that are hindering ART scale-up, such as inadequate staff and gaps in supply of drugs in the public sector.[30]Other barriers, such as stigma and food insecurity, compound the effects of these obstacles in the health system.

Staff shortages hinder the government's efforts to expand access to ART and ensure that access is equitable via addressing the specific needs of women who experience gender-based abuses.A 2006 Ministry of Health evaluation of the ART program in Zambia identified severe shortage and high turnover of trained staff as "the most significant constraint in ART service delivery."[31]The report identified "inadequate recruitment, insufficient re-training of the few staff in position, inadequate monetary and non-monetary retention incentives, long working hours in ART sites, and increased workload due to rapid increase in numbers of enrollments due to the free ARV policy"[32] as major causes of staff shortages.The latest available data on the number of healthcare workers in Zambia indicates that in 2004 there were only 1,264 physicians-0.12 physicians per 1,000 people-and 16,990 nurses-that is 1.56 nurses per 1,000 people.[33]

Dr. James Banda, director of the District Health Management Team for Kitwe, a large town in the Copperbelt, stated that staff shortage was "the most fundamental challenge that we face every day."[34]According to Banda, Kitwe's population of 460,000 is serviced by just 483 health care workers.[35]Staff shortages in Zambia are discussed further in Chapter VI.

Women in Zambia

Zambian women face multiple forms of discrimination and abuses, including gender-based violence and insecure property rights.Women's relatively low socioeconomic and political status is reflected in a number of indicators that are discussed below.

Domestic and Sexual Violence

In 2001-2002 more than half of ever-married women surveyed reported being beaten or abused by their husbands.[36]In November 2006 the Zambia chapter of Young Women's Christian Association (YWCA) reported that their shelter recorded ten cases of rape of adult women in Lusaka every week.[37]There is no specific law against domestic violence, so cases must be prosecuted under the general assault statutes, which typically do not provide effective protection for women because of the need to provide evidence of gross bodily harm, or of the fact that the perpetrator was carrying a weapon.Moreover, the penal code does not specifically prohibit marital rape, and the provisions on rape in the code do not in practice apply to spousal rape.

Property Rights

Zambian statutory law partially protects women's inheritance and property rights, but failure to prevent discriminatory customary law taking precedence over statutory law undermines such protection.Moreover, the laws are poorly enforced.The Intestate Succession Act (1996 amendment) provides that a widow should receive 20 percent of her deceased husband's estate, and that it is illegal to evict a surviving spouse from a matrimonial home.[38]However, under the customs of some ethnic groups, which are more widely used by Zambians than statutory law, the right to inherit property often rests with the deceased man's family.The inability to enforce their property rights in the area of inheritance is compounded for HIV-positive widows since in-laws sometimes threaten to punish them if they insist on keeping their property by not caring for their childrenwere they to fall sick or die.A lawyer at the International Justice Initiative, an organization that focuses on cases of property grabbing, told Human Rights Watch, "We had one case when a woman was [HIV] positive, [her in-laws] said, 'It is just a matter of time, you are sick [and will die soon] and then see what we are going to do to the children.'"[39]

In-laws may also insist that a widow undergoes sexual "cleansing" (through sexual intercourse with a hired male of lower social status), and as a result, widows sometimes give up their property to avoid this practice.As Yoram Siame, HIV/AIDS program officer at the Church Health Association of Zambia, a PEPFAR partner, put it, "If a widow is not willing to share property with in-laws, they will say, 'Take everything, but we want cleansing.'"[40]

The Matrimonial Causes Act, which address division of marital property upon divorce, was passed by the National Assembly passed in 2007 and is awaiting presidential signature.[41]When it comes into force, the Matrimonial Causes Act will be applicable to civil marriagesunder the Marriage Act.[42]It enables courts to determine settlement of property upon divorce, but is silent in terms of equal distribution of property upon divorce.However, most people in Zambia marry according to customary law rather than the civil marriage statute, and thus the protections of the Matrimonial Causes Act will not apply to them.[43]Although customary law is continuously evolving and heterogeneous, reflecting the norms of Zambia's 73 ethnic groups, it generally continues to discriminate against women in marriage and divorce.Customary practices tend to grant men all rights to marital property.

Zambia's constitution prohibits the enactment of any law that is discriminatory on the basis of sex or has such discriminatory effect.But it also recognizes a "dual legal system," which allows local courts to administer customary laws, some of which discriminate against women.

One promising property rights development is Zambia's land policy, which requires that 30 percent of all land advertised for lease be allocated to women.However, to qualify for the land acquisition it is necessary to prove the capacity to develop the land, as evidenced by bank statements, and this is often an impossible hurdle for women.[44]

Social, Economic, and Political Indicators of the Status of Women

A range of indicators show that women are at a distinct social and economic disadvantage in Zambia.Statistics on literacy show that only 59.7 percent of women are literate compared to 76.1 percent of men.[45]Poverty affects women disproportionately.Many women are in low-paid and low-skilled jobs with little job security.Seventy-six percent of women in Zambia are engaged in agriculture, fisheries, and forestry.[46]Sixty-three percent of women engaged in agricultural work receive no payment for their work, compared to 56 percent of males working in the same sector who do not get paid for their work.[47]

Women's Political Participation

In Zambia women's representation in government falls below the 30 percent target set by the Southern African Development Community and the 50 percent target set by the African Union.[48]In 2006 only 100 women stood for election to the National Assembly, compared to 605 men.Of these 100 female candidates, only 21 were elected to the National Assembly, representing 14.19 percent of the Assembly.[49]There are currently only 22 women MPs out of a total of 150 elected and nominated members of the National Assembly.Only six out of 23 cabinet members are women, although after the 2006 elections the President of Zambia appointed a Minister of Gender and Development.[50]

Decision-Making within the Household and Negotiation of Safer Sex

In Zambia women's ability to make informed decisions about their health and lives, including their ability to obtain information on HIV/AIDS, counseling, and testing, and their ability to negotiate safer sex, is seriously impaired by the perceived and real control of men (particularly intimate partners) over their lives.At the household level, statistics from the Zambia Demographic Health Survey (ZDHS) indicate that the majority of husbands have the final say in making decisions on wives' healthcare.[51]As the interviews for this report indicate, this meant that women felt unable to receive HIV testing or treatment without their husbands' permission.The ZDHS also indicates a strong correlation between a woman's financial position and her decision-making power: of wives who indicated that they had no say in household decision-making, 36 percent were unemployed, 30 percent were employed but not for cash, and only 18 percent were in formal, paid employment.[52]

Women in some of Zambia's ethnic communities are socialized to be submissive, not to challenge male authority, and to respect and please men.[53]As one activist told Human Rights Watch, "Women can't speak in public. They shouldn't discuss their domestic affairs. They must keep quiet as a wife."[54]Over half of the women interviewed for this research indicated that married women in many Zambian communities are taught to submit to demands for sex from their husbands and have little power to negotiate safer sex.They said it was considered inappropriate for women to initiate discussions about sex with their intimate partners.

Many of the women interviewed for this report described the difficulties they experienced in attempting to negotiate condom use.Isabel H. told Human Rights Watch that healthcare workers told her that she must refrain from having unprotected sex with her husband as both were living with HIV.Isabel H.'s husband refused to use condoms: "Every time we had sex, there was a quarrel.He didn't want to use condoms."[55]

Cultural beliefs about the roles of women and men also inform how women themselves think about, and respond to, gender-based violence.The ZDHS found that a large majority of women (85 percent) and men (69 percent) believed that a husband is justified in beating his wife for at least one reason.[56]As one activist put it, "our culture means that women must accept certain extremes, for example, violence. They are constrained by culture when [a woman] gets married, she is told, 'take things as they come.' She must accept a certain level of abuse, it's a way of life."[57]

V. The Impact of Gender-Based Abuses on Women's HIV Treatment

We have seen domestic violence interfere with ARVs [antiretroviral drugs] many times.There are several examples of such cases among women in [YWCA's] shelter.One [of the women in the shelter] had a partner who threw away her pills.[He] said to her, "If you have to drink medicine you're out of this house."

-Yeta Mekazu, shelter manager, Young Women's Christian Association, Lusaka, February 1, 2007

Human Rights Watch identified gender-specific barriers that impede Zambian women's ability to seek HIV information or start and continue using ART.These include violence and the fear of violence by intimate partners, the fear of abandonment and divorce in an environment where women suffer insecure property rights, and property grabbing upon the death of a spouse.These abuses occur in the context of poverty and of a culture that condones male authority and control over women.The final result can be severe.Some of the women in need of ART either do not access ART in the first place, with dreadful impact on their health and their lives, or they hide their HIV status and their ART, which sometimes results in missing vital ART doses or appointments to collect their medication.

Gender-Based Violence

Women reported to Human Rights Watch that domestic violence at the hands of their husbands and intimate partners, and the fear of such violence, had a direct, harmful impact on their ability to start and continue using ART.Women said that they were beaten, slapped, shouted at, verbally abused, and raped upon discussing HIV testing and treatment with their husbands, after disclosing their HIV status to their husbands, and as a result of visiting health facilities to collect their ART.

Some of the women interviewed for this report said that they could not be tested for HIV infection or get access to ART because of the kinds of abuses described in this chapter, or fear of such abuses.Some women only accessed HIV services and started ART after their husbands died.Others said that they received HIV tests through antenatal services while pregnant, but because of violence and the fear of violence they did not go back to the health facility to collect their test results.Other women started taking ART without informing their husbands.

HIV Testing and Disclosure

To access treatment women need to receive an HIV test, and if the test results are positive, they usually take further tests before they can start ART.Married women interviewed for this report stated that their husbands and other intimate partners beat, kicked, or emotionally abused them when discussing HIV testing and treatment, and when they disclosed their positive HIV status.This caused critical delay in their ability to start ART.Mercy Z., 29, told Human Rights Watch,

I got married in 2004 and my husband started giving me STDs [sexually transmitted diseases]. He goes out with women.When I ask for a condom, or go to the clinic to get treatment, he starts beating me. In January 2006 I went for VCT [voluntary counseling and testing].He was refusing [to receive an HIV test].The results came positive. From the time I got the results, he started beating me up.After two months he chased me away. He beat me everywhere.When I was four months pregnant he beat me until the placenta came out.I had to go to the Victim Support Unit [a special unit of the Zambian police that addresses abuses against women and children].[58]

Some of the women interviewed for this report described the psychological abuse they experienced as a result of discussing HIV testing with their husbands and when their husbands found out about their HIV status.Unique Z., who lived with her Zambian husband in a neighboring country where he worked, told Human Rights Watch that when she discussed HIV testing and counseling, "[My husband] just ignores me, he does not even eat in the house.He just comes home and takes a bath and goes out again."[59]Unique Z. said that this delayed her decision to receive an HIV test until she became very sick:

When I became very sick, I said that I needed to be near my mother and came back to Zambia. [That was when] my brother took me to take an HIV test.[At the time], my CD4 countwas 21.[60]When I tested positive, I went into depression for three weeks I am on ARVs [antiretroviral therapy] and on Monday my CD4 count was 725.When I [first] met [my former husband] he was very good.Two months after we met he said to me "I want you as a parent [mother for his children]." I said to him okay, let us have [an HIV] test.I [later] discovered that he was just a womanizer.We fought when I asked him about women.He hit me on the mouth.He tore half of my hair.I spoke to his brother but he told me that this was a domestic affair and there is no need to involve the police.I just went to his elders and discussed it."He is not a criminal." That is what they said.[61]

Numerous other women said that their husbands described them as "prostitutes," suggesting that the women had extramarital affairs and as a result they suspected that they had sexually transmitted infections.As such, several women interviewed for this report told Human Rights Watch that they decided not to discuss the matter with their husbands or take HIV tests.

Women who access routine HIV testing as part of antenatal services sometimes fear domestic violence should they raise the issue with their partner or husband and as a result some may never return to the clinic to receive their HIV diagnosis or to be assessed for readiness for ART. Others simply decide not to start ART.Monica Mwachande, a senior nurse at the government's Kalingalinga Clinic, said that when she asks women why they did not return to the clinic for further tests, "At times they say, 'Suppose I find my results positive, this may cause problems at home.'"[62]

The impact of the delay in HIV testing and in commencing ART as a result of violence is reflected in the testimony of Precious C., 43, who was only able to receive an HIV test and later enroll on ART after her husband abandoned and then divorced her.She told Human Rights Watch, "My CD4 count was only 4 . I went down to 27 kilograms from 68 kilograms.[I looked like] a skeleton.There were buds [bumps/blisters associated with AIDS related skin conditions] coming from my body and I was impaired whenever I came into contact with sunlight I realized that I was killing myself."[63]Precious said that had she still been with her husband, she never would have been able to start ART, and that she could have died as a result:"If I was still with him I am sure I would have died [by now] because he'd never have allowed me to test or go on medicationHe used to beat me a lot."[64]

Another factor that delays women's access to HIV testing and ART is that women sometimes feel that they must obtain their husbands' or partners' permission to receive an HIV test.Many of the women interviewed for this report said they were counseled upon reaching puberty to be submissive and obey their future husbands.Women also repeatedly told Human Rights Watch that they received pre-marital counseling from elderly female relatives who emphasized women's subordinate role within the household and their obligation to obey their husbands.Violence against women within the household, they were told, was normal and acceptable, and a woman should remain in her marriage regardless of her husband's behavior.In some traditions, according to Women in Law and Development in Africa (WiLDAF), "domestic violence is misconstrued as a sign of love, 'rather than divorce her, he is willing to mould her into the kind of woman that he wants.'"[65]Like gender-based violence, these gender norms and socialization often shape women's attitudes toward seeking healthcare, including HIV testing and counseling, with devastating results.

A number of women said that until their husbands died, they felt unable to take an HIV test or access treatment.When Ruth M., a 52-year-old farmer from Chongwe, and her husband started getting sick, she tried in vain to convince her husband to allow her to receive an HIV test, and for him to test as well:

I used to tell my husband, we should both [receive] HIV test[s].He refused.He didn't want me to go for a test.He said, "This is not AIDS but people just [be]witched us."We used to go to witch doctors, but there was no help.We just wasted a lot of money I went for [an HIV] test and the results were positive.I am on ARVs now If it was not for my husband, I would have gone for VCT long ago.I didn't know what was wrong [with me] and sold a lot of things at the farm to pay the [witch] doctors.Now there is hunger at home and a lot of poverty.[66]

A growing body of research addressing women in sub-Saharan Africa shows that despite incidents of gender-based violence and abandonment upon disclosure,[67] where there is acceptance of a woman's HIV-positive serostatus by her partner, being able to disclose HIV test results to sexual partners resulted in less anxiety, increased social support, and improved access to care and support programs.[68]Still, the difficulties that women in sub-Saharan Africa face in disclosing their HIV-positive status are reflected in the fact that the lowest rates of disclosure in the studies conducted among women receiving antenatal services were in sub-Saharan Africa.[69] Many of the women interviewed for this research said they felt unable to disclose their HIV status to their husbands, and as a result had to take HIV medicine secretly (see below).

The Impact of Violence and Abuse on Access and Use of ART

Women interviewed for this report who were enrolled in ART programs told Human Rights Watch that, as a result of physical and psychological abuse and the fear of such abuse, they sometimes missed ART doses and clinic appointments, including appointments to collect their medicine.Some women felt compelled to hide their HIV status and medicine because of fear of violence, or because they feared that their husbands might dispose of the medicine.Berta K., whose husband beat her routinely, told Human Rights Watch, "I started medication in 2006. [My husband] does not know."[70]Beatrice S. told Human Rights Watch that she was not planning to inform her husband about her HIV status: "My husband is not good to me.Once I asked him to go for VCT but he refused.He does not want me to drink any medicine or go anywhere.Even these scratches on my face are because I was in the market to buy vegetables.He said, 'You are late, why?' and he started beating me.He beats me up about every two weeks."[71]

Commencing ART without informing their husbands, many women told Human Rights Watch that they had to grapple even with where to keep their medication. Some of the women testified that they dug holes in the ground or in flower pots to hide ARVs.These women then retrieved the medicine-which they must take for the rest of their lives-twice every day and then hid it again.Others told Human Rights Watch that they hid the medication in the dish or bag for the family's mealie meal (maize-based traditional staple). Others said they hid the medicine in suitcases under their beds, or in aspirin and panadol containers.Some pretended they were taking family planning pills.Some of the women said they missed ART doses as a result of all this subterfuge.One woman told Human Rights Watch that because she fears domestic violence, "I take the medicine out of the bottle and put it in a plastic [bag] or in a paracetamolbox [container] . Sometimes I would miss a dose."[72] Marrietta M., who said that her husband often beat and insulted her, hides ART in her clothes: "I hide my treatment in my clothes.My husband will not look for it in my clothes.My husband and I fight a lot. He insults me and he says very bad things to me. He is a very difficult person and I do not want to upset him."[73]

Having started ART secretly, some of the women interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that when they experienced side effects of treatment, they had to make up explanations so as to avoid violence and other abuses.Marietta M. told Human Rights Watch, "When I started the medication, I had bad side effects.I had to tell my husband that it was malaria."[74]

Regardless of whether husbands knew about their HIV status or treatment, women whose husbands continually beat them or otherwise abused them sometimes missed ART doses.Berta K., stated,

[Sometimes, my husband] comes back at 18:00 hrs, drunk, closes the door and says, "Today you are going to freak out."He locks [me] in, he beats me up and then he locks me out.[On another day I would say], "Here is Nshima" (traditional Zambian food), and he would say, "You think I am not wise enough to know this is Nshima?"He beats me up and locks me out of the house.I go to the neighbors.If they have mercy they will let [me] in, if not, [I] sleep under a tree until tomorrow.As a result of that I miss doses sometimes.I feel very bad. I don't even feel like taking the medicine.I say, "Ha, let me die."[75]

Other women told Human Rights Watch that their husbands beat them or threatened to beat them if they saw them taking ART.Charity T. said, "I do not take my medicine in front of my husband.He told me that he would beat me if he saw me taking the pills.He did slap me when he saw me take them.I did miss taking some of the pills because I was scared of my husband.It was very difficult for me to take the medication in the beginning because of him."[76]

Most of the women interviewed for this report testified to the impact of verbal abuse on their health in general and on their adherence to ART.Rooted in dominant beliefs about women, verbal abuse described by women interviewed also reveals how stigma is entrenched in society.Verbal abuse often takes place alongside other forms of abuse. Efforts to avoid such abuse have caused over 30 of the women we interviewed to miss ART doses.The testimony of Maria T., 45, whose husband only knows that she has tuberculosis, is telling:

I did not tell anybody about my [HIV] status apart from [members of] the support group.I fear to tell my husband because I fear that he can shout [at me] and divorce me.He uses bad language with me every time, especially when he is drunk.[He says], "The vagina of your mother," "the anus of your mother, move away from me you are a patient of TB, you could die in my hands." I hide the medicine, I put it on a plate, add mealie meal, so when he takes the lid off he [does not find the ART medicine].I take the medicine at 8:00 hrs [when he is] at home and at 20:00 hrs when he is still at work.I have to make sure that he is outside.That is why I forgot to take medicine four times since I started treatment [in June 2006].Last year he hit me around the back with his fist. I got the cooking stick and hit him back.[77]

In addition to the direct, dire impact of physical and verbal abuse on women's ability to access and continue using ART, at least five women told Human Rights Watch that their husbands threw away their antiretroviral medicine.Charity T., whose husband abused her physically, stated,

Once [my husband] threw away my medication into the pit latrine. He said that he did not want to see these medicines in his house.I used to hide the medicines with my neighbor; I left them there for six months.After he threw the medicines away, I had to go back to the clinic the next day to get more medicine.I did explain to the nurse what had happened.She got me more medicines.[78]

Several support group leaders, activists in women's groups, and HIV treatment- adherence counselors told Human Rights Watch similar stories.Ida Mukuka, an AIDS activist and former support groups coordinator, said that in some of the groups she ran "Women would come and say, 'My husband rapes me every night. He would throw the ARVs in the toilet.'It is a very sad situation."[79]An adherence counselor in Lusaka also relayed the experience of a former patient who passed away: "She took her drugs at the same time as her husband.Every time they quarreled her husband would beat her up and take her drugs and throw them away."[80]The manager of the shelter that the Young Women's Christian Association (YWCA) established in Lusaka also recounted the stories of two women survivors of domestic violence who used the services of the YWCA shelter, "The partners of two women who are on ARVs refused [to let] the women drink [HIV] medicine.One woman [said that] her husband threw away her medicine and told her, 'If you drink that medicine, you are out of this house.'"[81]

The experiences of women interviewed for this research show that gender-based violence thwarts the ability of many of them to continue HIV treatment.The majority of the women interviewed told Human Rights Watch that they attended adherence counseling sessions at ART clinics.When asked whether they discussed their experiences of verbal, psychological, and physical abuse, they said that counselors did not usually ask about these issues, unless they notice visible marks of assault (see Chapter VI).[82]

Some of the women interviewed by Human Rights Watch stated that despite continuous beating and verbal abuse, they made sure to take their ART on time.This could be because the majority of the informants started treatment when they were already extremely ill with full-blown AIDS and so have seen the difference ART made in improving their health over time. Or another reason, as noted in Chapter III, could be that Human Rights Watch researchers mainly interviewed women who were connected to support groups, attended adherence counseling, or both.Support group leaders and adherence counselors often emphasize that patients should take ART on time as prescribed by clinic staff.Women who have missed appointments to renew their prescriptions for ART reported that they were "told off" by clinic staff.Consequently, some of the women interviewed might have decided not to admit missing ART doses as they associated Human Rights Watch researchers with clinic staff.

The testimonies in this chapter show that women are very resilient and often use creative means to ensure that they take ART on time and attend clinic appointments, while at the same time undertaking key care responsibilities. Some even use gender-based violence as an excuse to attend clinic appointments.The story of Lucia G. is indicative:

I tested [for HIV] in 2005.I was ill [and] a nurse asked me to go for VCT.I asked my husband who refused and said "if you go for VCT and test positive I will divorce you."I went secretly [to the clinic] and tested positive.This way I knew what was wrong with me.After three months my CD4 [count] went down so I was put on ARVs.I am still on ARVs but my husband does not know.I am only managing because I hide medicine.I dig in the ground, put medicine in a tin, and put it in a hole then put the water bucket over it, so no one would know that there is medicine buried underneath.I am always thinking about my life.I do not want to lose my marriage and I do not want to lose my life, so I have to do this to keep my marriage and my life.If I am divorced I cannot look after the children.My husband is very arrogant.This scar on my face is because he hit me.He beats me because he suspects I am ill and because I go to the clinic a lot when I am ill or [to collect] ARVs.He beats me, insults me, and asks me why I go to the clinic every time.I tell him I need to go to the clinic because of the beating.If I do not get beaten for a whole week that is too long.He hits me almost everyday, which is good for me because I can [find an excuse to] go to the clinic.I never reported him [to the police].I once told the headman [village chief].[83]

Lucia G., and other women interviewed for this research described how they raise funds specifically to cover transportation costs to attend clinic appointments."When my appointment [at the HIV clinic] gets nearer, I sell pumpkin leaves to raise money [for transportation].Sometimes I manage [and] sometimes I don't, so I borrow money from friends."[84]Similarly, Angela R., a market vendor who sells fruits, who said she hid ARVs between two flower pots, told Human Rights Watch: "I go [to the clinic] by bus and have to pay [Kw10,000 (about US$2.50) for a round trip].I do not [usually] get profit from my business, so when there are a few days left for my appointment at the clinic, I do some piece work, like washing other people's clothes.Once I missed a clinic appointment last December because I had no transport money.At the clinic they shouted at me and warned me not to miss [appointments or ART doses] because this is very dangerous."[85]

Insecure Property Rights

Women interviewed for this report identified unequal property rights, and their inability to protect their property rights, as a major factor impeding their access to ART and their ability to adhere to treatment.For women who married under discriminatory customary laws, their lack of property rights often mean having to remain in abusive marriages, which in turn can impede treatment.Fear of divorce in a context where women are economically dependent on men forces some women to hide ART. Women who seek divorce and lose property they accumulated during their marriage suffer constraints that restrict their ability to afford transportation costs to attend clinic appointments, collect ARVs, or attend treatment-adherence counseling.Similarly, widows told Human Rights Watch about property grabbing by in-laws when their husbands died, which made it harder for them to start and continue taking ART, due to economic constraints.Property grabbing also led some women to enter new, abusive marriages just to sustain themselves and their children.

Unequal Property Rights upon Divorce

Right now, [we have about] seventy clients for [each] legal officer.The most common issue is divorce in local courts.If married under customary law, nothing is given to the woman.[Not] even her clothes!

-Rumbidzai Mutasa, legal officer at the Women's Legal Aid Clinic, Lusaka, February 23, 2007

As noted above, among some ethnic groups in Zambia, to which over 50 percent of the women interviewed for this report belong, women who marry under customary law often lose the property accumulated during their marriages upon divorce.[86]The resulting economic hardship often affects their HIV treatment.Women who divorced under customary law told Human Rights Watch that they suffered abject poverty and were not able to afford transportation to health facilities to collect ARVs or even to afford food.As a result, they had to take medicine on an empty stomach.This is problematic as some ARVs must be taken with food and good diet can help with recovery.Moreover, the appetite of people recovering from AIDS related illnesses may increase.[87]

Human Rights Watch documented the experiences of women abandoned by their husbands and other intimate partners, chased from their homes, and divorced by their husbands as a direct result of disclosing their HIV status.Women told Human Rights Watch that fear of abandonment and divorce, and the consequent loss of property, sometimes forced them to hide their HIV status and their ARVs.Caroline M., 31, whose first husband divorced her upon finding out that she had HIV, eventually married another man to whom she did not disclose her HIV status, so she hid ARVs."If I disclose my status to my husband," said Caroline M.

I fear two things: [being] divorced again or that my husband would just say, "Stop taking ARVs, you are okay".So when I get the ARVs from the clinic, I throw away the box [container] and keep the plastic [bag].I place the medicine underneath clothes in the wardrobe.My husband does not even touch clothes.He asks me to bring clothes to him from the wardrobe. I take the medicine at 8:00 hrs and 20:00 hrs.We only have two rooms so when my husband brings friends home I prepare themedicine and put it in the kitchen in advance.My new husband is bossy.He always says "You can't be positive, and these ARVs you hear about are not good."He thinks he cannot be HIV-positive.When he's drunk he is a problem.He hits me and shouts at me.[88]

Ann K., 27, whose husband divorced her, received her HIV-positive test result one day prior to her interview with Human Rights Watch.Married according to customary law, she told Human Rights Watch that upon divorcing her, her husband appropriated all her belongings, including plates, cupboards, mattresses and sheets.Ann K. said she complained to the "headman" of the farm where she lived with her husband, but her husband ran away to Lusaka to avoid confrontation with the headman, and her former husband's new wife claimed that these items were presents from her parents.Ann K. said that she gave up trying to reclaim her badly needed belongings due to ill-health."I am sick but I have no sheets or mattresses.I have to sleep on a mat on the floor.I have one blanket that my niece gave to me.I share it with the children."[89]She was due to return to the HIV clinic on the next day for further tests.Ann K. said that although the doctors might enroll her on ART, she might not be able to tolerate the medication with no food to eat.

Property Grabbing

Widows living with HIV/AIDS interviewed by Human Rights Watch described the daunting impact of property grabbing-the unlawful appropriation of property by relatives of the deceased (usually a man)-on their HIV treatment.Property grabbed by in-laws, said these widows, could have helped them start small businesses, feed themselves and their children, and pay for transport to attend clinic appointments.Some of the widows who needed HIV treatment before it was available for free also said that property grabbed by in-laws could have helped them generate income to cover ART costs.

When Mina P.'s husband died in 1999, she had already told him that she was living with HIV/AIDS.Along with his relatives, he accused her of "bringing HIV to the house."Upon her husband's death, his relatives took the couple's property:

I was not working when my husband died.His relatives blamed me They said that I had brought illness into his house.His relatives took all the property and they sold our land.I didn't get any money from the land.I did not [report this to the Victim Support Unit].My relatives said that I must not fight over the land ...You do not fight over land as we all come from the soil.When I had the land, [my family] always had something to eat.After they took the land, I really struggled and we often did not have food.This was not good for my health and I got sick. I could not afford [HIV] treatment at this time. If I had had the land, I could have sold it to pay for [HIV] treatment or I could have sold some of the things that we grew.[90]

Even after the Zambian government made ARVs available for free, property grabbing by in-laws has at times forced widows receiving ART to miss vital clinic appointments because they were unable to afford transportation costs.The experience of Hilda M. is illustrative:

All the property was taken by [my late husband's] relatives. They took a motor vehicle, TV, radio, DVD player, dining room suite and sitting room chairs.They told me that I was going to die so I would not need these things. I did not try to get this property back-it is the way things are-I have no power.My problem is that I do not have enough food now.These drugs are very strong.I need to have food to take them.If I had the minibus I would use it for business and I would get money for food and transport. I have to catch a bus to the hospital to get my medication every month.My sister has to give me money for this, and when she can't, I have to walk. It is too far when I am feeling weak.I have missed some appointments when I do not have money for transport.Once I did not collect my medication for three days.[91]

Not only does property grabbing intensify poverty among women, it also prompts them to enter into new relationships for economic security, in some cases with abusive partners.When June S.'s husband passed away in 1991, his relatives "grabbed everything."[92]June S. never got her property back.Having received an HIV-positive diagnosis the same year, she went to live with her father and stepmother, where she was mistreated.After four years June S. remarried.She told Human Rights Watch that her current husband beats her up, rapes her, and refuses to use protection during sexual intercourse, even though she disclosed her HIV status to him.Whenever she refused to have unprotected sex with her husband, said June S., her husband would just grab her.[93]June S. reported her husband to the government's Victim Support Unit (VSU) when he beat her badly, and VSU officers offered to refer her to the YWCA shelter.June S. told Human Rights Watch that she wanted to know her CD4 count to see if she needed HIV treatment, but that her husband "does not want to hear about HIV treatment."[94]She explained to Human Rights Watch that had her property not been grabbed when her first husband died, she could have sold the property to keep going, and that she could have left her current abusive husband.

When the husband of Beatrice S., 35, died, his relatives grabbed all their belongings."The family got these things because [my] husband worked: TV, fridge, stove, sofa, and iron.I got nothing, just my clothes."[95] Beatrice, who has been receiving ART since 2004, had to find accommodation with a friend who later married her.Beatrice S. said that she will not inform her current (similarly abusive) husband about her HIV status or about the fact that she is on ART.

Lack of Access to Food

Many of the women interviewed for this report, especially those who lost their property upon divorce or upon the death of their partners, spoke of hunger as a major problem marking their experiences of taking ART.[96]Lack of adequate food is a general problem in Zambia, where, in 2004, 68 percent of the population was classified as poor, and 53 percent of the population could not afford the cost of a basic food basket of Kw78,223 (about US$18.50) per month.[97]Poverty in Zambia affects women disproportionately, given their already low economic status and dependency on male partners.For example, in 2002/2003 poverty stood at 58 percent in female-headed households, compared to male-headed households where poverty stood at 43 percent.[98]

For adults and children living with HIV/AIDS, adequate food and nutrition are essential for the health of their immune systems and for the success of ART.According to the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), "Adequate nutrition is essential to maintain a person's immune system, to sustain healthy levels of physical activity, and for quality of life. Adequate nutrition is also necessary for optimal benefits from antiretroviral therapy."[99] Similarly, Pathfinder International explains that,

Many people who are diagnosed with AIDS have lost weight through chronic ill health. They may have decreased appetite, be unable to eat much because of candidiasis in the mouth or esophagus, have poor absorption, or have chronic diarrhea. Co-infection with TB is common in HIV infection, and widespread TB infection may also cause weight loss. Weight gain may be rapid for persons commencing ART and after treatment of TB. Some ARVs must be taken with food and recovery may be assisted by a good diet. Many people recovering from AIDS-related infections have increased appetite, and this can be a problem in poor households that are not food secure.[100]

Payment of Related Costs

Women who do not enjoy secure property rights may also lack the resources needed for tests related to ART where these are not consistently available for free, as is the case in the Copperbelt province.As discussed earlier, in June 2005 the Ministry of Health announced that it would provide a full package of HIV/AIDS care, including ART, free of charge to Zambians. It appears, however, that this policy is not being uniformly applied in the two provinces studied for this report.Interviewees in Ndola, in the Copperbelt province, indicated that they only receive antiretroviral medicine free of charge, and must pay for CD4 countsand other diagnostic tests.

For all the reasons explained above, the cost of these tests also severely impacts women in abusive relationships.For example, Dorothy M., who said that healthcare workers advised her to have a CD4 count every six months, said that she was four months late on taking the test because she could not afford the cost.Her husband-who assaulted and abandoned her along with her two children when he found out that she had HIV-refused to pay for it.[101]Another woman told Human Rights Watch that she was unable to commence treatment because she could not afford the cost of the CD4 count. Her doctor recommended that she take the test as soon as possible since she had suffered from a number of opportunistic infections, but her husband refused to pay.[102]

VI. Zambia's Response to Gender-Based Abuses Impeding Women's HIV Treatment

I have always felt that [the government is] not doing anything.If the president says, "declare free drugs," do they know what is happening to women?When ministers talk about achievements [in terms of treatment rollout], the biggest beneficiaries of ARV [programs] are women.[But] What have they [really] done for them?They need to put appropriate laws and policies in place.[There is a need] for provisions for women [so] if they are beaten because they are [HIV] positive, men should be jailed.

-Ida Mukuka, AIDS activist and former support groups' coordinator in Lusaka, January 31, 2007

The Zambian government's rollout of free ART is commendable as is the establishment of a gender ministry in 2006.However, the government has not done nearly enough to prevent or respond to gender-based violence and inadequate protection of women's property rights, and the impact that these abuses have on women's ability to access and adhere to ART.Healthcare facilities providing ART-which are overburdened and under-staffed-have no systems in place to detect or address gender-based abuses such as domestic violence.The training that counselors receive does not cover gender-based abuses in a systematic manner, nor does the understanding of gender-based abuses factor into official counselor certification.There are no government protocols on how to address gender-based abuses, including domestic violence, within ART programs, and monitoring systems do not track the effects of such abuse. Our research found no arrangement or partnership between the government and nongovernmental service providers that could provide such services at healthcare facilities.

Similarly, the country's legal framework fails to address these issues adequately.Zambia has no specific law that criminalizes gender-based violence.The penal code does not cover marital rape or psychological abuse.Prevalent customary laws discriminate against women in terms of property allocation upon divorce or the death of a spouse.The 1989 Intestate Succession Act regulates inheritance where the deceased did not leave a will, by providing for the surviving spouse in such cases, but it is ill-enforced.

This chapter examines the response-or lack thereof-of the health system and the legal, justice, and policy frameworks in Zambia to the violations described in the previous chapter.

The Health System

Health Policies

The Zambian government is responsible for devising health policies, delivering healthcare services, regulating private providers of healthcare services, and regulating healthcare workers, including HIV and ART adherence counselors.[103]In 2005 the Zambian government launched the National HIV/AIDS/STI/TB Policy (hereafter National HIV Policy).The policy identifies "[g]ender issues that perpetuate the dominance of male interests and lack of self assertiveness on the part of women in sexual relations" as a major factor contributing to the spread of HIV.The policy also lists women's poor socioeconomic status and unequal distribution of household resources as determinants of the disproportionate effects of AIDS on women.The policy, however, does not mention gender-based violence and its effects on treatment.

In May 2006 the government launched the National HIV and AIDS Strategic Framework, which stated that AIDS was inter-linked with poverty, social and economic inequality between women and men, and dominant cultural beliefs, and acknowledged the disproportionate effect of AIDS on women.[104]This framework, however, does not suggest ways to address gender-based abuses.The Fifth National Development Plan (2006-2010) (FNDP) further articulates the national policy response to HIV/AIDS.It has a specific chapter on gender and recognizes the role of gender-based violence in the spread of HIV/AIDS.[105]The FNDP recommends strengthening the penal code with respect to gender-based violence and facilitating the enactment of a gender-based violence bill as strategies for the gender sector during the period (2006-2010).[106]

Healthcare Facilities and Gender-Based Violence

In the past decade an international consensus has gathered around the importance of recognizing gender-based violence as a critical public health issue,[107] and as a barrier to women's use of health services.[108]As a result, the WHO and UNAIDS issued a policy statement in 2004, calling for interventions that take into account the different needs of women and men who access HIV services.[109]And the UN Commission on Human Rights in 2005 encouraged states "to ensure the availability towomen and girls of comprehensive and accessible health-care services and programmes and to health‑care providers who are knowledgeable and trained to recognize signs of violence against women and girls and to meet the needs of patients who have been subjected to violence, in order to minimize the adverse physical and psychological consequences of violence."[110]

In 1999 the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW Committee) identified gender-based violence as a critical health issue for women, and called upon states parties to guarantee "(a) The enactment and effective enforcement of laws and the formulation of policies, including health care protocols and hospital procedures to address violence against women and the provision of appropriate health services; (b) Gender-sensitive training to enable health care workers to detect and manage the health consequences of gender-based violence."[111]

In Zambia our investigation revealed that healthcare facilities providing ART have not adequately responded to gender-based abuses, including violence against women, in a way that would enhance women's access and adherence to ART.Although relevant policies generally highlight the importance of gender in addressing health needs in Zambia, they seldom address gender-based violence.Healthcare workers responsible for monitoring adherence to ART are not required to probe for gender-based violence or other abuses as potential hindrances to successful treatment, nor are they adequately trained to do so.Existing health protocols do not cover gender-based violence.

HIV adherence counselors, other health professionals, and policy-makers, however, told Human Rights Watch that they would welcome programs through which they could probe for and address gender-based violence in ART clinics, if adequately trained and equipped to do so.This should be part of an overall strategy to address gender-based violence and other abuses that affect Zambian women.

Monitoring Adherence to ART and Gender-Based Abuses

Chapter V discusses the extent to which violence against women and inadequate protection of property rights for women affect women's access and adherence to HIV treatment.Health facilities disseminating ART, including clinics, could play an important role in detecting and responding to these abuses, especially during adherence counseling sessions.In Zambia clinical follow up for all patients living with HIV/AIDS takes place at least every three months.Patients receiving ART typically present every month at clinics to collect their drugs.[112]At these monthly visits they also generally attend adherence counseling sessions.These are one-on-one sessions where a trained counselor determines the capacity of a patient to take his or her prescribed ART, monitors adherence to ART, and helps patients develop ways to cope with their illness and with ART.

Human Rights Watch's interviews with women receiving ART and with healthcare staff, including adherence counselors, indicated that healthcare facilities providing and monitoring adherence to ART seldom address gender-based violence or other abuses.This is left to the discretion of individual healthcare workers,[113] several of whom said they only discuss gender-based violence when women have visible signs of physical abuse.[114]In such cases some counselors advise women to contact the VSU or the YWCA,[115] or offer them couple counseling.[116] Staff at the YWCA said that at times hospitals refer women who were injured as a result of domestic violence-and who were receiving treatment for these injuries-to YWCA.[117]

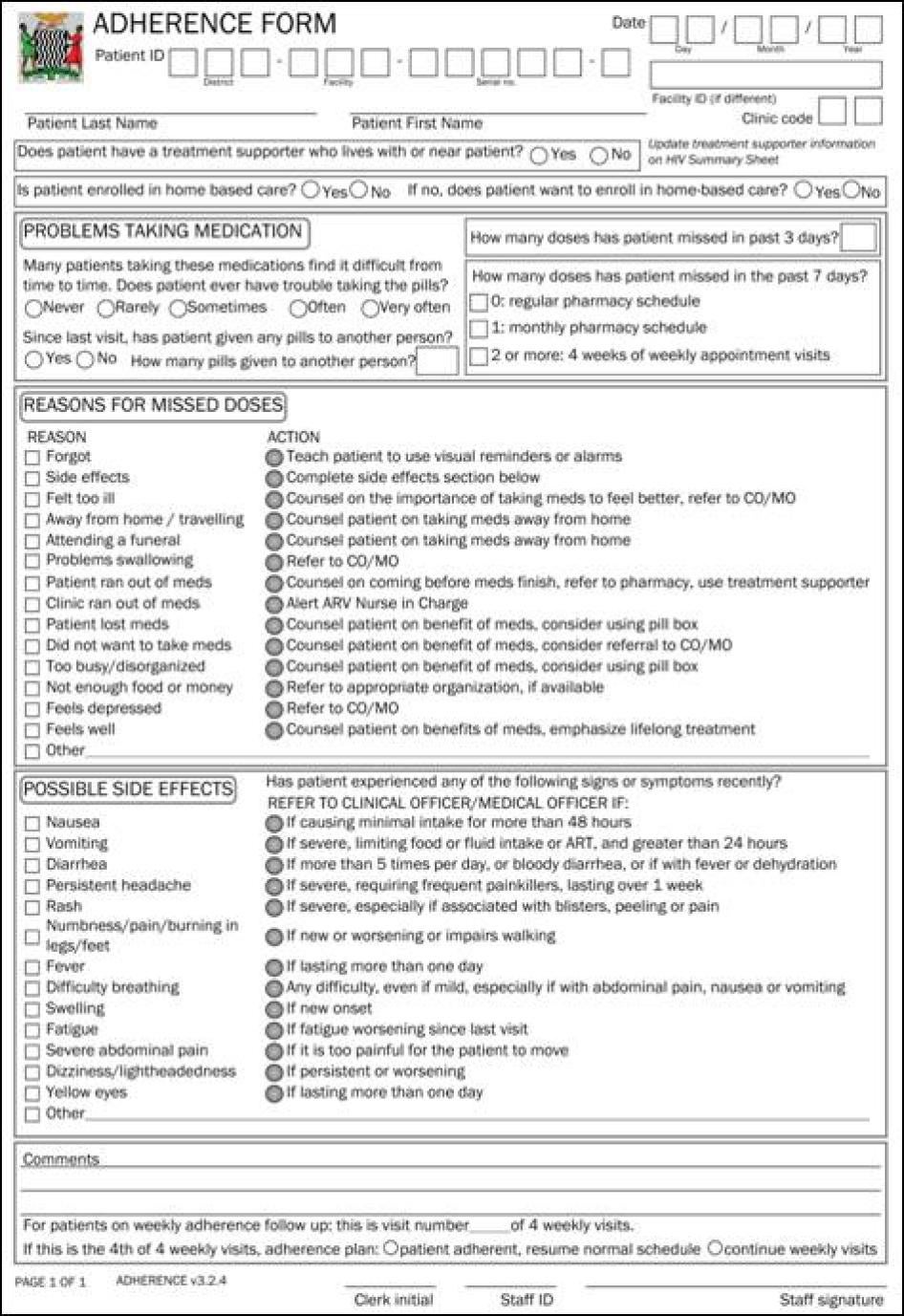

Counselors commonly monitor patients' adherence by counting the pills remaining from the last visit and asking questions if the patient has missed ART doses.Most counselors complete a form, devised by the Centre for Infectious Disease Research in Zambia[118] (see Appendix I), that assists counselors in discussing adherence-related issues with patients.[119]It probes a wide range of reasons why a patient may not have taken their ART, including that the patient forgot, felt too ill, experienced side effects, ran out of medication, was uncomfortable taking the pills in front of others, was disorganized, or had problems swallowing.However, the form does not include questions about violence, including violence against women.Thus, some of the critical barriers to women's adherence to ART remain undetected and unaddressed by healthcare workers.This undermines these facilities' ability to provide appropriate support to women who experience violence.[120]

Probing whether female patients have experienced or fear gender-based violence or other forms of abuse or discrimination including violations of their property rights, in adherence counseling sessions can help women overcome the dehumanizing effects of the abuses described earlier in this report, and would improve women's ability to cope with ART, HIV/AIDS, and violence.[121]Human Rights Watch asked policy-makers, counselors, and other healthcare workers about the feasibility of detecting and responding to gender-based violence by healthcare staff in facilities providing ART.The majority of healthcare professionals and policy-makers interviewed said that, with proper support, it would generally be desirable and feasible to address gender-based violence in their work.Dr. Kamoto Mbewe, reproductive health specialist at the Ministry of Health in Zambia, supported the idea of integrating questions about gender-based violence "because women may hide the abuses, so it is important that [health workers] help those [women]."[122]Elizabeth Serlemitsos, chief advisor at the Zambia National AIDS Council (NAC), said that it would be "realistic" to recommend that adherence counselors ask about domestic violence, but that in rural areas, where there are less community resources, this requires HIV counselors to have basic skills on how to counsel women about gender-based violence.[123]

The manager of planning and development at the Kafue District Health Management Team stated that it "will help us a lot to have these interventions [to address gender-based violence]."[124] Theresa Chidothi, a nurse and counselor in Nangongwe clinic in Kafue, rural Lusaka, said that screening for and addressing gender-based violence was "a welcome idea.We require skills to handle [survivors of gender-based violence]."[125]In terms of time limitations, Theresa Chidothi said, "I think we can manage [in Kafue] because we have set aside a day to [see patients in need of ART]."[126]