Afraid and Forgotten

Lawlessness, Rape, and Impunity in Western Côte d’Ivoire

Map of Côte d’Ivoire

© 2010 John Emerson / Human Rights Watch

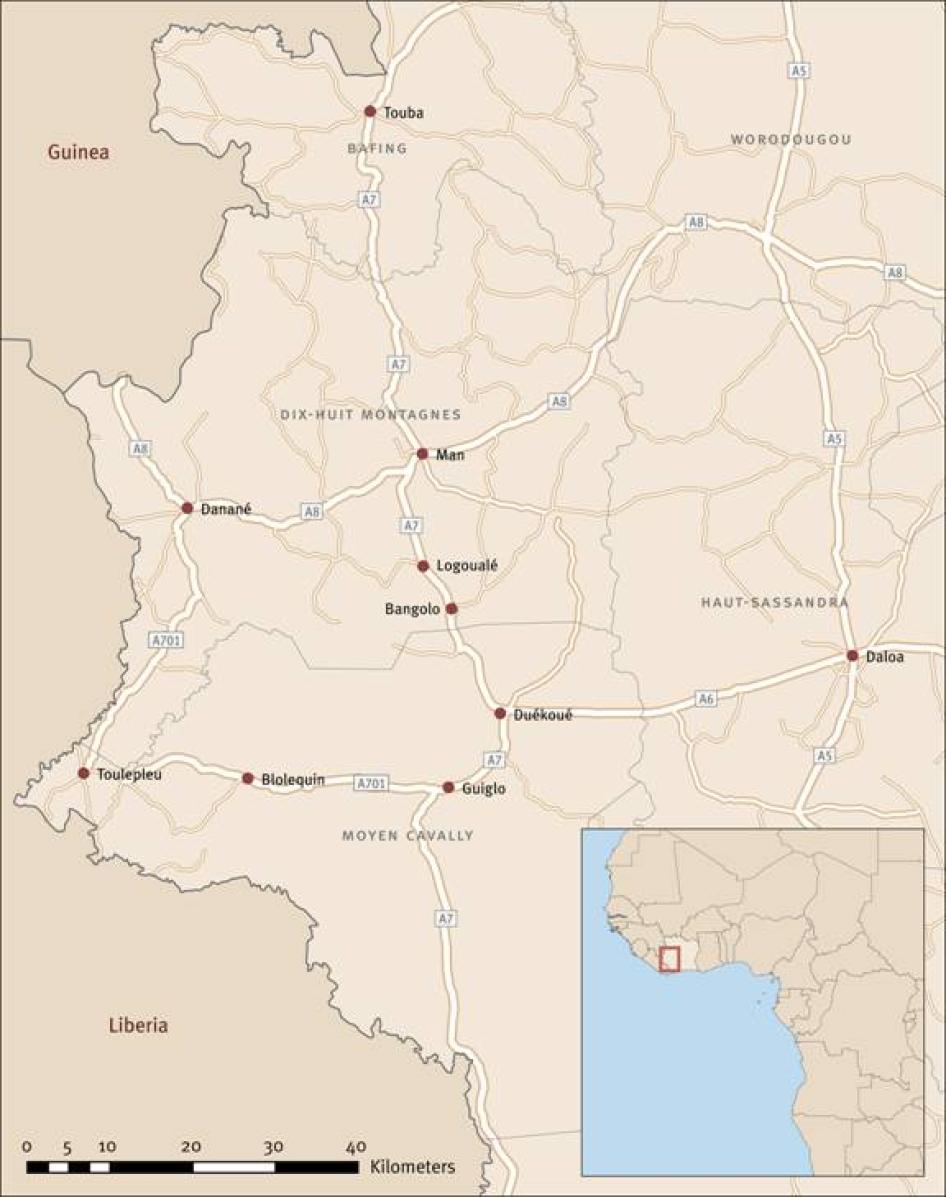

Map of Côte d’Ivoire’s Far West

© 2010 John Emerson / Human Rights Watch

Summary

As Côte d’Ivoire heads toward long-delayed presidential elections scheduled for October 31, 2010, the far west of the country is in a state of near lawlessness. Here, the power of the gun prevails and the rule of law has all but disintegrated amid increasing political, conflict-related, and criminal violence. Criminal gangs, militiamen, police, gendarmes, and rebel forces subject locals to an unrelenting stream of abuses, including banditry, assault, extortion, and the rape of women, girls, and even babies. State institutions tasked with preventing and holding accountable those responsible for the violence have largely failed to act, allowing a dangerous culture of impunity to take hold.

The worst-hit areas are the western administrative regions of Moyen Cavally and Dix-Huit Montagnes—often referred to as the “Wild West” by humanitarian organizations and journalists—where criminal gangs attack and subject the population to abuse on a widespread basis in their homes, en route to market, and as they travel between their villages and the main regional towns.

International human rights law obligates Côte d’Ivoire’s government to respect the right to life, right to bodily integrity, right to liberty and security of the person, and the right to be free from discrimination, which includes an obligation on states to take appropriate measures to eliminate sexual and gender-based violence. As a result, the state—headed by the president, who is also commander-in-chief of the armed forces—must take all reasonable steps to protect persons within its territory or jurisdiction, including supporting the investigation and prosecution of private actors who infringe these rights. Ending the impunity that allows violence and other criminal practices to continue requires leadership from the highest levels of the state. Proactive patrolling by police and gendarmes, particularly on market days and during the harvest season, would likewise contribute greatly to improved security.

The region’s problems are rooted in the social, political, and military crisis that has racked Côte d’Ivoire since 2000, accelerating economic decline, deepening political and ethnic divisions, and leading to serious human rights abuses. Following the end of active hostilities in 2003, the country settled into a state of “no peace, no war,” divided between a rebel-controlled north and a government-controlled south. In 2007, the belligerent parties signed the Ouagadougou Political Agreement, which outlined plans for citizen identification, voter registration, disarmament, and the country’s reunification. However, there were immediate delays in implementation: presidential elections were postponed six times; disarmament was an almost total failure; and the country remained divided. Moreover, the government’s failure to re-establish the rule of law in the west—the region hardest hit by the conflict and with the highest concentration of arms—has allowed bands of armed former combatants and other armed youth to make a living from banditry and other forms of criminality.

One particular problem, especially within the violent-prone regions of Moyen Cavally and Dix-Huit Montagnes, is the severely compromised judicial system. There is no functioning trial court or prison in the whole of Moyen Cavally, leaving victims to travel between 70 and 250 kilometers to the courthouse in Daloa, located in the neighboring Haut-Sassandra region. While a trial court does exist in Man, the largest town in Dix-Huit Montagnes, it remains essentially non-operational due to a lack of essential state judicial personnel and the de facto authority of the rebel forces known as the Forces Nouvelles (“New Forces,” or FN). Corruption and inadequate staffing means the few cases that are adjudicated often result in the premature release of prisoners who are on remand or even convicted. The government has failed to take adequate steps to improve security and access to justice, even as international partners like the European Union and the World Bank pour hundreds of millions of dollars into judicial and security sector development.

Police and gendarme officials present another problem, routinely failing to fulfill their duties to protect, investigate, or prevent lawlessness. Victims described how security officials repeatedly refused to pursue and investigate criminal elements, even when attacks were reported at checkpoints only a few kilometers from the scene of brutal physical and sexual violence. Indeed, state authorities often demand bribes from victims to file complaints, most of which languish with authorities who show little interest in investigating or arresting perpetrators. Even when arrests do occur, suspected perpetrators are often freed within 24 or 48 hours, leaving victims disillusioned with authorities and terrified of revenge.

Police and gendarmes also engage in systematic extortion at checkpoints and roadblocks. In government-controlled Moyen Cavally, state officials routinely prey on individuals by extorting and, at times, beating, robbing, and arbitrarily detaining residents under the pretense that they do not have proper identity cards. Immigrant populations from northern Côte d’Ivoire and neighboring countries are targeted for particularly harsh treatment. Meanwhile, in Forces Nouvelles-controlled Dix-Huit Montagnes, rebel forces dispense with such pretense altogether, and simply demand money from residents and businesses through threat, intimidation, or force. The rebels, who accrue a financial windfall from this extortion, actively maintain control despite the redeployment of many state authorities to the northern half of the country—including to Dix-Huit Montagnes in the west.

All levels of state and rebel authority appear to be either directly involved in extortion or complicit in these practices due to their failures to reprimand, much less discipline, subordinates. Moreover, the prevalent checkpoints further weaken the already precarious security situation by reducing the population’s confidence in the respective forces and pushing people to take secondary roads with fewer checkpoints, where criminality is rife.

In Moyen Cavally and Dix-Huit Montagnes, the now-infamous coupeurs de routes, or road bandits, prey in particular on those traveling during the cocoa harvest and on market days, when victims generally carry greater amounts of money. Many residents and victims described almost daily attacks during the cocoa harvest, and attacks occurring like clockwork on market days throughout the year.

Groups of bandits establish makeshift roadblocks and then surround their victims walking along the roads or traveling in transport vehicles. Almost always masked, they are armed with Kalashnikovs, hunting rifles, long knives, and machetes. Secondary roads between towns and surrounding villages are notoriously treacherous. The bandits work meticulously, often stripping their victims to ensure that they find every last coin, inflicting physical abuse and, at times, killing those who refuse to relinquish their money or try to identify them.

Hundreds of women and girls have been sexually assaulted, raped, and gang raped during these criminal acts. Women and girls are systematically pulled off transport vehicles, one by one, and marched into the bush where they are raped while other bandits stand guard. Victims include very young children, including babies, and women over 70 years of age. During home attacks, husbands are tied up and forced to watch as wives, daughters, and other female family members are raped. Women sometimes become pregnant as a result of these attacks, while underreporting and clandestine, unsafe abortions likely hide many other cases.

Transport drivers, cocoa farmers, and women going to market are forced to make precarious ends meet as they negotiate between armed bandits, who perpetrate violent criminal acts on a consistent basis, and security forces, who are not only unlikely to investigate these crimes, but engage in their own forms of predatory behavior.

Their overwhelming fear of moving along the roads has led some inhabitants to significantly change their lifestyle; for many, this fear has severely undermined or destroyed their livelihood. Others simply live with the dread that an attack may occur the next time they or a loved one walk to market or travel to sell cocoa. While travel at night is wholly impossible in most areas because of the security situation, the daytime is scarcely better. The vast majority of the scores of road attacks that Human Rights Watch documented occurred during daylight hours.

At least some perpetrators in Moyen Cavally belong to militia, or former militia groups, who were actively armed and supported by the Ivorian government during the 2002-2003 armed conflict and its aftermath. The planned disarmament of these groups, and of the Forces Nouvelles rebels, has been an almost total failure, allowing for continued widespread use of firearms, particularly Kalashnikovs. Gangs of young men have exploited the availability of arms and the breakdown of the rule of law to wreak further havoc on the population.

While Ivorian officials, the UN, and the diplomatic community have focused principally on organizing the October 31 elections, the population continues to suffer rampant criminality with little to no possibility of recourse to justice. Ordinary Ivorians have little faith in authorities’ will or ability to effectively stop perpetrators of abuses, much less hold them to account. As long as state structures fail to function, and state authorities prioritize extortion over protection, people in western Côte d’Ivoire will continue to suffer.

Recommendations

To the Minister of the Interior, the Minister of Defense, the Major General of the Gendarmerie, and the Director General of the National Police

- Investigate gaps in security for the local population in western Côte d’Ivoire, and provide better protection to communities from bandit attacks.

- Strengthen the response to complaints presented at checkpoints regarding nearby bandit attacks, including by proactively pursuing perpetrators.

- Ensure effective allocation of resources to checkpoints, including staffing and equipment, and discipline officers who refuse to respond to complaints.

- Step up patrols on market days and during the harvest season, particularly on secondary roads around Duékoué and Guiglo.

- Develop plans to more systematically root out criminal elements, including by conducting operations in communities and neighborhoods where bandits and criminal gangs are known to be based.

- Significantly increase staffing and logistics of police, gendarmes, and mixed brigade forces deployed to western Côte d’Ivoire, so that they can respond more effectively to the high incidence of criminal acts perpetrated against residents.

- Issue clear directives to police, gendarmes, and customs officers manning checkpoints across Côte d’Ivoire to desist from bribe-taking, extortion, and other corrupt practices.

- Establish a focal point in police and gendarme stations, as well as a telephone hotline, for victims to file complaints about abusive practices by state security forces.

- Ensure that complaints are thoroughly investigated, and establish internal disciplinary measures within the forces to take action against members of the security services who abuse the population.

- Proactively and routinely investigate the behavior of security forces at checkpoints even in the absence of complaints from residents.

- Establish an independent oversight committee in departments throughout the country to monitor and evaluate the police and gendarme response to all crimes, with particular focus on sexual violence cases. Include women from local civil society on the oversight committee.

- Conduct a public information campaign on the mandate and locations of all Integrated Command Center forces. Ensure that they wear distinct uniforms or insignia so that the population can distinguish them from Forces Nouvelles soldiers.

To the Minister of Justice and Human Rights, the Minister of the Interior, and the Judiciary

- Immediately establish functioning legal institutions in the region of Moyen Cavally, in particular by rehabilitating the Guiglo court building and constructing detention facilities. Urgently finalize the agreement with the United Nations Operation in Côte d’Ivoire (UNOCI) that outlines its assistance, and the government’s obligations, in completing these tasks.

- Immediately redeploy outstanding state judicial and correctional officials to Forces Nouvelles territory, including prison officials and judicial police to the prison and trial court in Man, ensuring a return to at least pre-conflict capacity. Ensure that the prison is under state, not Forces Nouvelles, control.

- Improve the response of law enforcement personnel and the judiciary to sexual and gender-based violence, including by recruiting more female police officers to act as focal points in police stations, and by training judicial and security personnel on responding to sexual violence.

- In accordance with international fair trial standards, prosecute members of the security, defense, and rebel forces who engage in criminal conduct, including the solicitation of bribes, arbitrary arrest and detention, or physical abuse against those who refuse to pay a bribe.

- Investigate cases of banditry and sexual violence in western Côte d’Ivoire, and prosecute perpetrators in accordance with international fair trial standards. Pursue impartially cases involving militias in Moyen Cavally and Forces Nouvelles rebels in Dix-Huit Montagnes.

To the Minister of Health and Public Hygiene and the Minister of Family, Women, and Social Affairs

- Improve services for victims of sexual violence, including medical and counseling services.

- Establish free emergency medical services for rape victims in all public hospitals and health centers in Côte d’Ivoire, including access to medical examinations, post-exposure prophylaxis drugs and antibiotics, psychosocial care, and follow-up consultations.

- Ensure sufficient coverage in areas without adequate health infrastructure, through training mobile teams and traditional healers.

- Disseminate information on treatment for rape victims to health centers and professionals nationwide.

To the President and the National Assembly

· Enact a law that eliminates the medical certificate fee in cases of rape and ensure that it is implemented universally.

· Ratify the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa and implement its provisions, particularly regarding sexual violence.

To the President, the Prime Minister, and the Integrated Command Center

- Finalize the disarmament process and ensure that arms are collected from all former combatants not formally integrated into state military and police entities, including from militia and the Forces Nouvelles.

- Allow independent inspection and reporting by UNOCI on weapons collected.

To the Forces Nouvelles

- Cease extortion and racketeering of individuals and businesses in the north.

- In accordance with the Ouagadougou Political Agreement and its Fourth Supplementary Agreement, relinquish control of taxation, customs, the judiciary, and the prison system to redeployed state officials responsible for these functions. Publicly declare that remaining state functions will be immediately handed over upon the redeployment of remaining state officials.

- Relinquish control over security and checkpoints in the north to the Integrated Command Center forces, where they are stationed, and dismantle any additional, unauthorized checkpoints.

- In accordance with the Fourth Supplementary Agreement to the Ouagadougou Agreement, hand over to the Integrated Command Center, in the presence of UNOCI peacekeepers and weapons inspectors, weapons collected by zone commanders from rebel soldiers. Provide statistics to UNOCI, the Integrated Command Center, and the National Program for Disarmament, Demobilization, and Reintegration (PNDDR) on the number of weapons collected and remaining at large.

- Allow the United Nations Group of Experts unfettered access to inspect all arms under Forces Nouvelles control.

- Ensure that demobilized and former Forces Nouvelles soldiers no longer wear military uniforms or carry weapons.

To the United Nations Operation in Côte d’Ivoire

- Engage the UNOCI Human Rights Division to undertake field investigations on human rights abuses suffered by the populations in Moyen Cavally and Dix-Huit Montagnes. Ensure that the reports of such investigations are publicly available.

- Publicly release all reports related to human rights abuses in Côte d’Ivoire, including posting regular updates and periodic reports online.

- In collaboration with Ivorian security forces, increase UN Police patrols around Duékoué and Guiglo on market days, most importantly by adding patrols that accompany women who come into Duékoué and Guiglo on market day from surrounding villages.

- Encourage and support Ivorian authorities to undertake a full and thorough Demobilization, Disarmament, and Reintegration (DDR) program in line with the Integrated DDR Standards (IDDRS) and other internationally recognized best practices.

- Provide technical and logistical support to assist state authorities in conducting thorough investigations of human rights violations, with particular attention to violence committed against women and girls, as articulated in UNOCI’s mandate.

To Foreign Partners and International Aid Agencies, notably the European Union and the World Bank

- Demand that the Ivorian government address the tenuous human rights situation in the country, which has been largely ignored during the long road to elections.

- Demand that UNOCI undertake more proactive investigation and reporting regarding the human rights climate in Côte d’Ivoire and engage more assertively with the government on documented human rights concerns and violations.

- Strengthen and expand funding for programs supporting victims of sexual violence, including medical care, counseling, and legal support.

- Undertake public awareness campaigns on how and where victims of sexual violence can access confidential and free treatment.

- For those funding or implementing rule of law programs, demand that the Ivorian government deliver tangible results, including increasing the staffing and infrastructure of key judicial institutions and courts and reducing corruption and checkpoint extortion by security forces. Fund and use independent monitoring and evaluation mechanisms, such as quarterly reports by the Improved Road Transport Governance (IRTG) Initiative, to determine the state’s success in combating extortion.

Methodology

This report is based on a three-week mission to Côte d’Ivoire in July and August 2010. It focuses principally on events occurring in western Côte d’Ivoire between January 2009 and August 2010.

Two Human Rights Watch researchers conducted interviews with more than 80 victims and witnesses of violence and extortion, as well as with government officials, law enforcement and military personnel, rebel soldiers, officials from the United Nations Operation in Côte d’Ivoire, representatives from Ivorian and international nongovernmental organizations, journalists, and diplomats. Human Rights Watch also received and viewed documentary evidence provided by victims, witnesses, and nongovernmental organizations.

Research was conducted in the financial capital, Abidjan, as well as in the towns of Duékoué, Guiglo, Bangolo, Man, Danané, and Daloa. This field research was accompanied by an extensive literature review of publicly available and unpublished studies on the human rights situation in western Côte d’Ivoire and the broader politico-military crisis.

All witnesses and victims were interviewed individually during in-depth conversations. Most interviews lasted approximately one hour. Interviews were generally held in secure locations agreed upon with the witness or victim to ensure safety and address their fear of reprisal. Most victims of sexual violence were interviewed in private with only a translator and interviewer present. In a few cases, staff from local women’s and human rights organizations were present to support the women. Only females were present for interviews with victims of sexual violence. Interviews were conducted in French, or with the aid of a French-to-English translator. When preferred by the interviewee, interviews were conducted in local dialects with translation into English or French.

Names of victims and witnesses have been changed or withheld to ensure their safety and that of their families. Details, including town names and the specifics of an attack, have been withheld where they could lead perpetrators to identify individuals interviewed. This was often done at the request of the interviewee. The names of officials with Ivorian and international organizations have also been withheld at their request to protect their identity, privacy, and security.

Monetary figures throughout this report are calculated using the rate of 500 CFA francs to the United States dollar.

Background

For decades after it gained independence from France in 1960, Côte d’Ivoire—a diverse country of some 20 million people on the southern coast of West Africa—prospered economically even as parts of its population were left politically excluded.

During the presidency of Félix Houphouët-Boigny (1960-1993), Côte d’Ivoire became an economic power in West Africa as a leader in cocoa and coffee production. Houphouët-Boigny oversaw an open-door immigration policy, which, coupled with the rapid growth of the Ivorian economy, attracted migrant workers from throughout the region who now comprise about a quarter of the population.[1] During this time, the president ruled the country as a one-party state based on an ethnic coalition of groups from the country’s north and center, leaving many ethnic groups in the south and west excluded.[2]

In the late 1980s, plummeting cocoa prices, land scarcity, and rising foreign debt led to an economic recession that left an increasing number of educated youth unable to find employment.[3] Many returned to their villages, including in the western part of the country, but often found that their parents had rented the land to immigrants and that no other arable land was available, resulting in large numbers of unemployed villagers. As unemployment and political discontent rose, opposition parties and civil society demanded multi-party democracy and other reforms, but the newfound parties soon split along ethnic and geographic lines.

Prelude to the Crisis

Questions of ethnicity and nationality dominated campaigning ahead of the first multi-party presidential elections in 1995. The main candidates were Houphouët-Boigny’s successor within the Democratic Party of Côte d’Ivoire (Parti démocratique de Côte d’Ivoire, PDCI), Henri Konan Bédié, also a Baoulé from Côte d’Ivoire’s geographic center; Laurent Gbagbo, the Bété leader of the Ivorian Popular Front (Front populaire ivoirien, FPI) from the south; and Alassane Dramane Ouattara, Houphouët-Boigny’s former prime minister then running as head of the Rally of Republicans (Rassemblement des républicains, RDR), whose constituency is largely drawn from northerners.[4]

Several politicians, notably Bédié, employed the rhetoric of “Ivoirité” (or “Ivorianness”)—an ultranationalist political discourse focusing on Ivorian identity that marginalized immigrants and other perceived outsiders—to garner support and exclude political rivals. After Ouattara was barred from running on account of questions over his citizenship, the RDR boycotted the elections.[5] Gbagbo and the FPI soon withdrew over concerns about transparency, and Bédié easily won the elections. During his six years in power, Bédié relied heavily on ethnic favoritism from the Baoulé and small ethnic groups from central Côte d’Ivoire to maintain control. A combination of plummeting cacao prices and rampant corruption and mismanagement led to the country’s dramatic economic downturn.

In December 1999, General Robert Gueï, a former army chief of staff, took power in a military coup and pledged to oversee a return to civilian rule with elections in 2000. Gueï’s initial pledges to eliminate corruption and introduce an inclusive Ivorian government were largely welcomed by Ivorians, but were soon overshadowed by his personal political ambitions, repressive measures against both real and suspected members of the opposition, and near-total impunity for human rights abuses by military personnel.[6]

During the 2000 election year, Ivorian politics divided increasingly along ethnic, regional, and religious lines.[7] Several weeks before the October presidential election, the military junta deemed a majority of candidates, including Ouattara and former president Bédié, ineligible—resulting in a contest between General Gueï and Gbagbo of the FPI party. After Gbagbo’s victory at the polls, General Gueï attempted to disregard the results and maintain power, leading to massive popular protests and the loss of his military support. He fled the country on October 25, 2000. Gbagbo became president a day later.

RDR supporters immediately called for new elections that included all candidates and clashed with FPI supporters and state security forces across Côte d’Ivoire. Violence, including massacres perpetrated by the army and gendarmes, continued through the December parliamentary elections, leaving more than 200 dead.[8] Political tension remained high, particularly in the west where explosive ethnic rhetoric by political and youth leaders exacerbated pre-existing land disputes. Groups of youth from ethnic and national groups in western Côte d’Ivoire, including Bété, Gueré, Yacouba, and Burkinabé, burned each other’s villages in June and July 2002, displacing thousands from all ethnic groups to Daloa and Duékoué.[9]

Civil War

On September 19, 2002, rebels from the Patriotic Movement of Côte d’Ivoire (Mouvement patriotique de Côte d’Ivoire, MPCI), whose members were drawn largely from the country’s Muslim north, attacked Abidjan, the commercial capital of Côte d’Ivoire, and the northern towns of Bouaké and Korhogo. While the rebels were unable to take Abidjan, they quickly managed to control the northern half of the country. Soon after, the MPCI was joined by two rebel factions from the west, the Ivorian Popular Movement of the Great West (Mouvement populaire ivoirien du Grand Ouest, MPIGO) and the Movement for Peace and Justice (Mouvement pour la paix et la justice, MPJ), creating a politico-military alliance called the Forces Nouvelles, or “New Forces,”under the leadership of Guillaume Soro.

The western part of the country was hit hardest by the war, decimating infrastructure and wreaking havoc on the local population. Certain Liberian rebel groups had long used western Côte d’Ivoire as a base to move arms and fighters to Liberia, where civil war ravaged the population for over a decade; by late 2002, thousands of arms, particularly AK-47s (“Kalashnikovs”), were flowing back. In addition, both the Ivorian government and the Forces Nouvelles recruited former combatants from the Liberian and Sierra Leonean civil wars to fight in the far west, where they committed many of the same kinds of brutal war crimes perpetrated in these neighboring armed conflicts.[10]

As the Forces Nouvelles marched south from Man and Danané through Moyen Cavally, the Ivorian government responded by forming and arming a network of militia groups to support the thinly-stretched Ivorian security forces.[11] General Denis Maho Glofieï, president of the Resistance Forces of the Great West (Forces de résistances du Grand Ouest, FRGO), composed of at least five militia groups that fought during the conflict, claimed to have more than 25,000 militia fighters under his control in the region of Moyen Cavally.[12] Both sides—the rebels as well as government forces and government-supported militias—committed serious human rights abuses, including massacres, extrajudicial executions, torture, and the recruitment and use of child soldiers.[13] Fighting forces perpetrated frequent acts of collective punishment in which civilians considered loyal to the other side were targeted. All of the fighting groups systematically committed sexual violence, including individual and gang rape, egregious sexual assault, forced incest, and sexual slavery.[14]

A ceasefire agreement put an end to active armed conflict between the government and the Forces Nouvelles in May 2003, although recruitment of mercenaries and severe human rights violations against civilian populations continued. Sexual violence against women and girls remained widespread due to weak legal and security institutions that failed to prevent violence, prosecute perpetrators, or support victims.[15] The country has remained effectively split in two, with the Forces Nouvelles controlling the north and the government the south.

Peace Agreements

Since the end of formal hostilities, the warring parties have signed a number of peace agreements. Each of these failed to bring about disarmament and unification of the country or substantial improvements in the rule of law. France, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), the African Union, and the United Nations have all spearheaded initiatives to end the stalemate.

These efforts resulted in a “zone of confidence” dividing the northern and southern halves of the country; the French commitment of the Force Licorne, a military force including over 4,000 troops during the height of the crisis, to help stabilize the country and monitor the zone of confidence; the installment of the United Nations Operation in Côte d’Ivoire (UNOCI), which peaked at over 11,000 peacekeeping troops; and the establishment of a UN arms embargo, in addition to travel and economic sanctions.[16]

In March 2007, President Gbagbo and rebel leader Guillaume Soro signed the Ouagadougou Political Agreement (OPA), later endorsed by the African Union and the United Nations Security Council.[17] The OPA was the first to have been directly negotiated by the country’s main belligerents on their own initiative. It resulted in the appointment of Soro as prime minister in a unity government, and hope that Côte d’Ivoire was moving out of a stage of “no peace, no war.”

The agreement reiterated previously defined objectives, including disarmament, the country’s reunification (including unified armed forces and state authorities), citizen identification, and voter registration, which at times was marred by low-level violence as issues of citizenship and ethnicity continued to fester.[18] The OPA also called for presidential elections by early 2008. Delays were almost immediate. Over three years after the Ouagadougou Agreement, and after six electoral delays, the presidential elections have still not been held, although they are scheduled for October 31, 2010.[19]

Weakened Rule of Law Institutions

At present, the power of the gun—wielded by militias, Forces Nouvelles rebels, and criminal bandits—has largely replaced the rule of law. Several factors in both the rebel-held north and government-held south have resulted in significant weakening of institutions mandated to maintain law and order, including the police and gendarmerie, and the judicial and corrections systems.

In the north, the failure to reunify the country has played the most significant role in continued lawlessness. After continued delays in implementing the OPA, the principal actors signed the Fourth Supplementary Agreement to the Ouagadougou Political Agreement on December 22, 2008, which committed them to take immediate steps toward reunification of the country, including redeploying state authorities to the north.[20] Police, civil servants and judges were due to begin work in the north by January 15, 2009. However, a lack of political will by both sides resulted in further delays in their redeployment. As a result, rebel commanders continue to exercise near-complete control over economic, security, and judicial affairs within their zones.[21] The May 2010 periodic report of the UN secretary-general on UNOCI notes:

Côte d’Ivoire is still a divided country, with the Forces nouvelles maintaining a parallel administration, economy, treasury, judicial system and security structures in the north…. [Forces Nouvelles] zone commanders, and Forces nouvelles-appointed mayors and other local authorities continue to exercise real authority and collect revenues in the north…. [M]any courts in the north and the west are non-operational…. [T]he tribunals in Man and Katiola remain closed since February, when staff abandoned their posts following the violent disturbances there.[22]

In addition, the Fourth Supplementary Agreement called on the Forces Nouvelles and the Ivorian armed forces to immediately make officials available for the Integrated Command Center (Centre de commandement intégré, CCI)—a joint security and defense force created under the OPA and envisioned to build confidence between the two sides. The CCI was to deploy primarily in the north and former zone of confidence and was mandated to provide security, oversee disarmament, and assist the return of state institutions, including the judiciary. More than a year later, progress remained slow, as noted by the UN report:

The mixed brigades deployed by the Integrated Command Centre, which have the task, inter alia, of maintaining law and order, lack adequate manpower and resources, and are not able to protect the population and the re-established State institutions. They maintain an uneasy coexistence with the heavily armed and well-financed Forces nouvelles security machinery.[23]

In government-held areas, the rule of law is similarly weak. Local human rights organizations working on justice issues decried the widespread corruption in the judiciary, as well as a lack of independence from the executive. Security forces in particular have benefited from longstanding impunity, and their continued extortion of the population at checkpoints around the country has weakened the public’s faith in their role as protectors.

Nowhere is the failure of legal institutions more evident than in the far west. Police and gendarmes routinely refuse to pursue known criminals or investigate crimes, at times demanding bribes merely to file a complaint. No tribunal or prison exists in the government-controlled region of Moyen Cavally, forcing residents to travel over 100 kilometers to Daloa, in the region of Haut-Sassandra, to find the nearest operational legal institutions. No judicial officials—including a prosecutor or judicial police—are therefore stationed in Moyen Cavally, severely hampering those investigations that are undertaken. In the midst of disintegrated state structures, men with arms are ubiquitous.

Failure to Disarm, Demobilize, and Reintegrate

More than three years after the Ouagadougou Agreement, the Ivorian government has failed to disarm various fighting factions, while the Forces Nouvelles and militia forces have ignored and subverted disarmament efforts. Residents in the west, home to tens of thousands of armed militia and rebel soldiers, have suffered disproportionately as a result.

Under the agreement, the CCI is to oversee the disarmament process. However, as noted above, the CCI is essentially not operational due to a lack of political will to commit resources to it. In addition, lack of will on the part of the Forces Nouvelles and the militias to disarm—combined with each party’s distrust of the other—has resulted in scant progress.

An official in UNOCI’s Disarmament, Demobilization, and Reintegration (DDR) division told Human Rights Watch that since 2007, UNOCI had collected a total of 715 arms from the rebels and militia forces combined.[24] This is despite the government’s account that 70,000 ex-combatants have been profiled and 29,207 are already considered to have been demobilized.[25] In the west, Ivorian officials convened a high-profile ceremony marking the disarmament of militia forces in May 2007. However, the UN was not allowed to inspect precisely how many arms were handed over to the government officials, who controlled the event.[26] A UN official who was present at the ceremony told Human Rights Watch:

There was a big ceremony, but it was a charade. The militia only brought out their oldest arms.Few of them handed over the real arms that we have seen them walking around with on the street.[27]

The UN Group of Experts, tasked with monitoring the UN Security Council’s 2004 arms embargo, noted the extensive presence of Kalashnikovs and ammunition among militias in Moyen Cavally, though generally found the light arms to be outdated and of poor quality.[28] In its May 2010 report, the International Crisis Group likewise described a heavy presence of arms among militias in Moyen Cavally, and the continued arrival of new arms via forest roads from Liberia.[29]

The Forces Nouvelles likewise remain well-armed, including in the region of Dix-Huit Montagnes. Of the 715 arms collected by UNOCI, even fewer came from the Forces Nouvelles than from the militias. Many Forces Nouvelles soldiers in Man still wear military fatigues and openly carry Kalashnikovs and other firearms. Indeed, the UN Group of Experts reported in October 2009 that northern rebel commanders were importing additional arms in violation of the UN arms embargo.[30]

Violence and Lawlessness in Western Côte d’Ivoire

Residents are frequently targets of violence and severe abuse in western Côte d’Ivoire. This is due to failed or non-existent state structures to protect and ensure justice for abuses, widespread proliferation of arms, and lack of political will to improve rule of law on both sides of the politico-military divide.

As noted above, several regions in western Côte d’Ivoire were the scene of widespread violence during the more active period of hostilities from 2002 to 2003. However, while the level of violence gradually diminished elsewhere, abuses in the west—particularly in the regions of Moyen Cavally and Dix-Huit Montagnes—have remained at near-crisis levels, and in some areas may even be rising.

A United Nations official based in western Côte d’Ivoire described the security situation to Human Rights Watch:

There have been no real improvements in the human rights situation here because the security situation has worsened. In this area we have the government’s armed forces, Forces Nouvelles, and the militias. The mix results in huge security problems.

The situation with banditry continues to worsen. In addition to road attacks, there have been a rising number of incidents in houses. At least daily I receive a report about armed people attacking a house in a village or a camp, or attacking on the road.[31]

Human Rights Watch documented scores of incidents in which heavily armed individuals, generally operating in small groups, committed acts of banditry along the region’s roads as well as home robberies. In the course of these attacks, victims were often beaten, stabbed with knives and machetes, and shot with firearms.

The armed men also committed frequent acts of sexual violence against women and girls, including aggravated sexual assault, individual and group rape, and gang rape. Human Rights Watch interviewed 23 women and girls who had been victims of rape and sexual violence in Moyen Cavally or Dix-Huit Montagnes since January 2009, and documented at least 86 additional cases from witnesses, including drivers of transport vehicles and family members. These and other victims whose cases were documented by Human Rights Watch were targeted while working in the fields, going to and from markets and places of work, or sleeping at home. They ranged in age from seven months to 78 years old.

The frequency of armed attacks has left the region’s residents in constant fear. Many have curtailed or severely limited their travel and daily routine. Indeed, certain areas are considered too dangerous to enter because of their near-total lawlessness.

Widespread Criminality by Coupeurs de Route

The coupeurs de route, a French term used to describe groups of armed individuals who attack vehicles and then rob the passengers of money and goods, typify the lawlessness in western Côte d’Ivoire.

One resident of a village near Guiglo told Human Rights Watch, “In the last three months, there has not been a single week that has gone by without at least two armed robberies that have touched people from my village alone. Most are by the coupeurs de route.”[32] A resident of Duékoué likewise said that road banditry occurred in the surrounding areas at least weekly, even during the non-harvest season when there is less road banditry.[33]

Moreover, there are indications that the phenomenon is increasing. Residents throughout Moyen Cavally told Human Rights Watch that incidents of road banditry date back to soon after the conflict, but have steadily increased since 2008. A representative of a local organization working with victims of sexual violence, including those raped during armed attacks on cars and transport vehicles, explained:

The incidents with banditry and rape started in 2005, but it was in 2008 and 2009 that it really went up. When they restarted selling cocoa, [the coupeurs de route] started to rob people because they knew people had money. So now they rob and steal money. Sometimes they kill the husband or wound or beat him, and they rape the women.[34]

Human Rights Watch interviewed 10 drivers of public transport vehicles in the west who had been victims of one or multiple attacks on the road, in addition to 18 passengers and other individuals who had been victims of armed banditry. The drivers alone experienced 17 separate attacks between November 2009 and July 2010; one driver had suffered four attacks during these nine months. They indicated that they knew of dozens more similar attacks on other drivers.

According to drivers and passengers who suffered road banditry, the attackers frequently place a large piece of wood across the road, or choose a location where drivers have to slow down because of sharp turns or holes in the road. As the driver brakes, bandits—between three and nine in number according to cases documented by Human Rights Watch—emerge from surrounding vegetation. They are always heavily armed, most often with Kalashnikovs, but at times with hunting rifles and small pistols that victims say appear to be locally made. Many bandits also carry knives and machetes, and are dressed in camouflage or black clothing.[35] All victims interviewed by Human Rights Watch described their attackers as wearing balaclavas or masks, sometimes makeshift masks made out of t-shirt fabric with holes cut for the eyes and mouth. Attackers almost exclusively speak French, with what victims commonly described as an Ivorian accent.

The attackers force the passengers off the road, threatening to open fire if the car drives away. They then quickly and meticulously steal money from each passenger. A driver from Guiglo who had been attacked three times since December 2009 described a typical ambush that occurred in January 2010:

About 10 kilometers from Guiglo on the road to V15 [a village in Moyen Cavally], there is a crossroads. Right before it, there was a long piece of wood stretched out. As soon as I pressed on the brakes, four people came out of the bush, pointing guns at the car. Two of them had Kalashnikovs, two were holding hunting rifles. They also all had long knives. They yelled at us to get out of the car. There were 14 passengers, in addition to myself and an apprentice. They marched us about 10 meters into the bush and forced us to the ground. They were all dressed like ninjas, completely covered in black. They had on masks that you could barely see through, with tiny holes for the eyes and mouth. And they all had on long sleeves and gloves.

Once we were on the ground, they tore at our clothes with knives, trying to find all of our money to make sure we didn’t have any hidden from them. They took 22,000 CFA (US$44) from me and my mobile phone. They kept yelling to keep our heads down and not to look at them, that if we tried to look at them they would kill us. It happened so fast, it lasted about 30 minutes. They took our money and then disappeared back into the bush.[36]

As discussed below, attacks occur most often during the cocoa harvest and on market days when people travel with larger sums of money. Moreover, several drivers and a UN official in the area told Human Rights Watch that the bandits appeared to operate with informants at the inter-city transport hub, at least in Duékoué, to target transport vehicles with wealthier passengers.[37]

The armed attackers often perpetrated severe physical violence against drivers and passengers. One victim of an attack in January 2010 said:

When the bandits didn’t think we got off the truck fast enough, they started beating us. They hit me with the back of their gun in the face and knocked out my front teeth. Three of them were hitting me, one with the back of his gun and then two others with their fists. It lasted for several minutes. I tried to cover myself, but they knocked my front teeth out with one hard hit to my face. I still don’t feel right and have headaches all the time because of this.[38]

Numerous victims and witnesses believed that the most brutal physical violence occurred as a result of victims’ attempts to determine the attackers’ identities, as explained by a driver whose route runs from Guiglo to the village of V15:

You can’t try to look at the bandits. One time when the coupeurs de route robbed my truck, one of the passengers looked at a bandit’s face, or the bandit thought he was looking at him, even though he had a mask on. The bandit yelled, “Why are you looking at me?” and then he hit the guy really hard with the back of his machete—not the blade part—and then with his gun. He hit the guy over and over until his face was running with blood.[39]

Others suffered particularly brutal abuse after refusing to turn over money. A farmer near Guiglo described how he lost his hand when he fought back against his attackers:

I was coming home from the market when I was met by four men who had cut the spiky leaves of the palm tree and placed them on the road. They told me to lay on the sharp leaves, so I went and lay near the sharp edges, but not on them. One said, “lay down,” and he cut me on my right hip with the machete. My mobile phone was in my pocket and blocked the machete but it still cut me—the wound was big enough so you could put two fingers inside it. They said, “Give us money,” and I said, “You told me to lay down so, I lay down, if you want money, take it…. Why do you hurt me like that? Now what money am I going to use to take care of my wound?”….

One caught me by the neck and pushed his machete in my back. Another man in front began to open my pants, and I kicked his legs and he fell to the ground. I tried to grab his throat so I could pull off his mask. Then the one behind me tried to cut my head with the machete, so I put my right arm up to protect me and he cut my hand off. It was hanging by just a few centimeters of flesh…. This happened at 2 [in the afternoon], and I was there in the field until 6 when someone found me and took me to the hospital.

When we arrived at the hospital there were no doctors so I stayed until morning. When the doctor came in, he said my hand was dead so he had to remove it entirely. The hospital took good care of me, but now it’s just a question of how can I work?[40]

Human Rights Watch received credible reports of four killings during road attacks in 2010. A planter from one village about 15 kilometers from Guiglo said that both his uncle and cousin had been killed in separate bandit attacks, in January and April 2010. The relative later saw the bodies, which had gunshots to the head.[41] Several drivers reported the killing of a passenger on a transport vehicle that departed from Duékoué when bandits opened fire after the driver refused to stop at a makeshift roadblock.[42] Finally, several drivers also described the killing in late 2009 of a passenger in their colleague’s vehicle after he refused to hand over money to bandits in an attack around Bangolo.[43] Countless girls and women have also been subjected by armed perpetrators to sexual assault, including rape and gang rape, as discussed below.

Widespread throughout the Far West

Human Rights Watch documented at least two bandit attacks since November 2009 on each of five separate roads in Dix-Huit Montagnes and Moyen Cavally. Multiple drivers noted that the incidence of attacks had reduced on the main road connecting the largest towns in the west, though sporadic attacks still do occur on it, particularly in the former zone of confidence between Duékoué and Bangolo.

One driver whose route went from Man to Daloa, for example, reported how his 18-passenger vehicle was attacked by bandits near Bangolo in December 2009.[44] Another driver of an 18-passenger vehicle was attacked around 10 a.m. in April 2010 between Bangolo and Duékoué.[45] In general, though, security on the main road has improved as compared to immediately after the war, as one driver explained:

At least one axis has improved in terms of security since the war—the main road from Guiglo to Bangolo. In the past, that was a no-go zone, especially from Duékoué to Bangolo. If you didn’t have a UNOCI escort, you just couldn’t drive there, no matter the time of day. It’s possible now, of course not at night. There are some incidents, some banditry, but the problems have diminished.[46]

Several drivers and other community members attributed this decline to convoys and patrols that UNOCI formerly operated along the main road, particularly between Duékoué and Man.

Despite some improvements along the main roads as a result of patrols and escorts by UNOCI, secondary roads in the region remain under frequent attack. These roads are generally unpaved paths leading from the main regional towns to surrounding villages. Drivers interviewed by Human Rights Watch had been victims of multiple attacks along the roads between Duékoué and Gbapeur, Guiglo and Nguya, and Duékoué and Kuassikro. The most treacherous appeared to be the road between Guiglo and V15, where Human Rights Watch documented at least seven separate incidents between December 2009 and May 2010. A UN official who monitors the security situation in the west similarly described the problems as now predominating on secondary roads.[47]

The end result is a level of insecurity and fear that keeps many from traveling unless it is absolutely necessary. Nighttime movement is completely off limits, as one driver who had been attacked multiple times explained:

The robberies are part of being a driver here. It’s tough, but what else am I supposed to do? I have lost a couple of apprentices after attacks—they said they just couldn’t do it, and I couldn’t fault them. I’m just too old to change. For me, the biggest problem is that there are so few hours in the day when people can travel, when I can work and make money. Right now, given the security situation, it’s only possible to be on the roads from 7 in the morning to 6 at night—if I push it, maybe to 7. It’s dangerous enough during the day, but it’s just impossible after that. There is no way to move without something happening.[48]

Period during and after the Harvest

Drivers, farmers, market sellers, and other victims reported that there is a notable increase in the number of road attacks between November and March, when cocoa is harvested and sold in the market. One cocoa farmer explained:

The coupeurs de route problem always exists, but it’s much worse during the cocoa harvest. Everyone has money and people are moving around. Farmers come to town to sell their crop and then receive cash before going back to the village. [Cocoa] buyers circulate around the camps with cash, purchasing from farmers. The robbers come out in full force because of the money available. By now [in late July], we have all run out of money from the previous year’s harvest, so it happens less.[49]

The clear majority of bandit road attacks that Human Rights Watch documented occurred between November 2009 and March 2010. Tens of people interviewed by Human Rights Watch lamented the weak state response to what they feared was a problem that would intensify during each cocoa harvest period. A cocoa planter from near Duékoué explained:

We are already hearing in the community that the bandits will rise again when the harvest comes. It has not stopped right now, but it has slowed down compared to the harvest time. When people start getting money from the harvest, though, it will happen all over again unless someone does something to stop them. As of now, they still have the guns, they still can do whatever they want to.[50]

Market Day

Human Rights Watch documented frequent attacks on market days when villagers converge to buy and sell goods. The concentration of attacks on these days, both during and after the harvest period, was confirmed by nearly all those interviewed—many of whom said that attacks happened weekly, at a minimum.

The petty trading that occurs on market days is primarily conducted by women and, as a result, they are disproportionately impacted by the attacks and violence that occur on these days. Several drivers and other community members told Human Rights Watch that most attacks on market days occur in the latter part of the day, when villagers are returning home with goods and money earned from selling produce. They further noted how the attacks occurred on both primary and secondary roads leading to and from major towns such as Duékoué and Guiglo to the surrounding villages.

While the routine nature of the attacks was well known, villagers had little alternative but to take the risk of robbery and rape to be able to buy provisions and make their living. A driver who had twice been victim to road banditry told Human Rights Watch about the general problem, as well as a particular attack in February 2010:

Driving on market days are the worst, though we have to do it because it’s one of the few days people travel anymore. Bandits are always ready to attack traders who have sold their merchandise, [so] driving home from the market is the most dangerous.

In February, I drove traders to the Friday market on Thursday afternoon. We can’t travel while it’s dark, so you have to take them early and spend the night. On the way back Friday afternoon, we were forced off the road by bandits…. There were six of them and they had Kalashnikovs. They weren’t satisfied when people handed over small sums of money. They knew people had more, so they started getting angry, yelling, “We know you’re coming from market. Give us the rest, or we’ll kill you.” Most people gave them the rest, but one of the passengers said he didn’t have any more. Two of the robbers beat him with their guns for about five minutes. I had to drive him to the hospital.[51]

Attacks are not limited to drivers on the road. Women walking to and from the market are also frequent targets. One Guiglo resident explained:

You hear of an attack almost every Tuesday. That’s market day here in Guiglo, so women from surrounding villages come into town. Some come on transport, but most walk, leaving when the sun rises. They are often in groups; the men are back working in the fields. On several of the secondary roads that lead into town, there is almost always an attack. The women’s money is taken and often some of them are raped.[52]

Indeed, the week before Human Rights Watch researchers were in Guiglo, bandits attacked several groups of women who were traveling to the Guiglo market, raping at least one woman.[53] A woman told Human Rights Watch how she was robbed of 40,000 CFA ($80) earlier in July as she headed back to her village from the Duékoué market.[54]

Despite the routine nature of the attacks and the known correlation with market day, victims and community members told Human Rights Watch that there had been no response from Ivorian security forces, which an Ivorian police officer in Guiglo acknowledged.[55] After a series of high-profile attacks in early 2010, several involving group rape, United Nations peacekeepers in the area established a patrol to accompany women living in Guiglo who were traveling to markets in surrounding villages, particularly the Friday market in the village of Gpapleu. However, no patrol yet exists for women who travel from surrounding areas into Guiglo for the Tuesday market—a significant protection gap for those communities living outside of Guiglo.

Attacks in Towns and Villages

The violence is continuing even though the harvest is over. It just continues in town. They attack homes and businesses. Everyday there is continued violence and rapes in the town…. It is becoming the way of life here. There is recurrent violence on young girls. People don’t report because they are scared of reprisal.

–Leader of a local women’s organization, Moyen Cavally, July 25, 2010

Residents in the western region of Côte d’Ivoire are frequently subjected to violent home invasions, performed by what appear to be the same groups of heavily armed bandits as the coupeurs de route. At times, the attackers also prey on people working in fields near their home.

Like road banditry, attacks in and around homes are most common in the region around and between Bangolo and Guiglo, although they also occur in and around the rebel-held towns of Man and Danané, albeit in a less violent form. The intensity of home attacks likewise appears seasonal, higher during the months when road banditry is less frequent, according to multiple residents of Duékoué and Guiglo.[56] Many of these attacks include egregious sexual assault and rape against women and girls, as discussed below.

Human Rights Watch interviewed 16 victims of home attacks, all involving groups of heavily armed men. A victim of one such attack in January 2010 described a typical case:

I was asleep, and at 3:30 a.m. there was a loud boom and people entered the house, knocking down our front door. There were eight of them. They demanded our mobile phones and then forced us down to the ground. One of them yelled, “If you don’t give us all your money, we’ll kill you.” They took 170,000 CFA ($340) from my wife, and 250,000 CFA ($500) from me—almost all the money we had. They targeted me because they knew we had money. One of them accidentally said my name, so they must have been from the community.

The three that came into my room were all masked and covered in black, and they all carried Kalashes [Kalashnikov rifles]. You could tell they were youth, probably between 22 and 25 years old. Five more stayed in the main room, where my children were, as a lookout. They all had Kalashes too. They searched everything in the house, they even cut into my suitcases. They said they would kill me if I moved. They never hit me, but they did strike and threaten my son—because he recognized one of them.[57]

The armed men often beat, stab, and sometimes murder male members of the family in the course of perpetrating armed robberies. Human Rights Watch received credible information about two separate killings in conjunction with home attacks. In both cases, relatives who lived in the same village saw the bodies and described bullet wounds. In one instance, the victim was alone when the attack occurred, while in the other, additional family members were present and told the relative interviewed by Human Rights Watch that the father was killed after he tried to fight back.[58]

Human Rights Watch documented numerous cases in which perpetrators severely beat or burned male victims, and, in one case, amputated the victim’s extremities. A witness who was present at a January 2010 attack in Moyen Cavally described how perpetrators cut off both of his uncle’s arms when he attempted to fight back.[59] Human Rights Watch also interviewed a victim from a January 2009 home attack who described witnessing the brutalization of the men in the house both before and while she and another woman were raped:

It happened at 1 a.m. There were seven bandits, six with Kalashes and one with a knife. They said to my husband, “Give us your money.” When my husband said “Wait, wait,” they had a knife and they stabbed him once in the buttock and twice in the right shoulder. His first wife’s son is 26, and they cut his leg deeply with a knife from one side to the other across his thigh…. They also tied up all three workers on our farm in a separate room. They lit a plastic bag and burned the workers on the face and back. I saw them just after.[60]

Human Rights Watch documented four instances of attacks by criminal gangs on people working in fields in or around their village. There was also credible information that armed bandits killed a man in April 2010 as he walked back to camp from his cocoa fields. Planters whose own fields were nearby heard gunshots and, while moving toward the area, reported seeing masked men leaving through the vegetation. The victim had been stripped, according to the planters, a sign the attackers were searching for money.[61]

Since women often tend to the fields and grow fruits and vegetables near the village, they appear to suffer disproportionately from these attacks. Human Rights Watch documented cases of sexual violence, discussed in detail below, perpetrated against women working in fields near their homes.

The overwhelming fear that such rampant criminality instills in people manifests in various ways. Many interviewees refused to divulge their name despite guarantees of confidentiality, saying that they were terrified of repercussions if it became known that they spoke about the attacks. Others looked around continuously during interviews with Human Rights Watch researchers, cautious of who might be listening. One Guiglo resident explained, “The criminal elements are everywhere. Nowhere is safe. We are just trying to survive, but everywhere there are these people with guns.”[62]

Widespread Sexual Violence

Victims and witnesses, as well as medical personnel and social workers with local and international humanitarian organizations, described widespread sexual violence by armed men against women and girls in western Côte d’Ivoire. Victims were raped in their homes; as they walked to or returned from market, tended to their fields, or foraged in the forest for food; and after being taken off public transport vehicles. Women interviewed by Human Rights Watch described a paralyzing climate of fear, where no place was safe, every woman and girl was vulnerable to attack, and perpetrators attacked with impunity.

Human Rights Watch documented 109 specific cases of rape in Moyen Cavally and Dix-Huit Montagnes since January 2009. Twenty-three cases were reported by victims, and 86 by witnesses.[63] The vast majority of documented rapes—81—happened during attacks by coupeurs de route on transport vehicles, followed by 11 documented cases during home robberies, 8 cases against infants and young girls either in their houses or the fields, and 9 cases of women and girls attacked while carrying out daily activities around their village.[64] Human Rights Watch documented the rape of girls as young as 7 months old and of women who were nearly 80.

Human Rights Watch also gathered accounts of gender-based violence from multiple organizations providing care and services to victims across Moyen Cavally and Dix-Huit Montagnes. These records indicated 676 cases of sexual and gender-based violence between 2009 and 2010, although the total number of cases occuring during this period is likely to be higher since these organizations did not seek to establish a comprehensive reporting system and cases of sexual and gender-based violence are frequently unreported. Indeed, two-thirds of the 23 cases that Human Rights Watch documented directly from victims were not reflected in these statistics, as victims had not reported the incidents to state authorities or other organizations.[65]

Sexual Violence against Women on Transport Vehicles

You are so scared you want to be a bird and fly away.

–Rape victim, Guiglo, July 25, 2010

The coupeurs de route routinely and systematically commit sexual violence against women and girls during attacks on transport vehicles.[66] In interviews with rape victims, drivers, and other passengers, Human Rights Watch documented at least 12 separate instances in which women had been sexually assaulted during attacks by road bandits. At least 81 women and girls had been sexually assaulted during these 12 attacks, which occurred between January 2009 and August 2010. Reports from drivers who had knowledge of similar attacks on their colleagues’ vehicles, as well as community members who knew neighbors who had been raped in similar attacks, indicated many more cases. A local women’s organization in one town in Moyen Cavally showed Human Rights Watch data for 40 rape cases that it had documented between January and July 2010, of which 26 had occurred during bandit road attacks (see text box below on underreporting of sexual violence).[67] A 31-year-old mother of five from Moyen Cavally talked about one such attack in January 2010:

We were going to the market and got on a truck—the type used to transport cocoa. There were lots of [women] in the back of the truck. We finished at the market around three in the afternoon and were going home when we were attacked by the coupeurs de route…. There were seven of them, including one woman…. They stopped the truck, and we got down and lay down with our faces on the ground, and they beat the men. I had 7,000 CFA ($14) hidden in four pieces of cloth. One of them called me to come. I hesitated but then I went. My husband was there and so was my father in-law…. [The bandit] ripped my underwear with a knife and he took my cloth and threw it aside. In front of my husband and my father-in-law, he raped me…. I lost my dignity that day.[68]

The majority of incidents documented by Human Rights Watch involved the rape of multiple women; in some instances as many as 20 women and girls were raped in a single attack. The women are typically removed from the vehicle one by one and raped in the surrounding vegetation. A 41-year-old victim of such an attack in January 2010 told Human Rights Watch:

Friday is market day in the village and we go to buy things there. We were in a Kia truck and there were about 20 women. When we arrived just outside of Guiglo, there were some branches on the road and the truck could not pass…. Then the coupeurs de route came out and caught the driver and threw him onto the ground.

They took the women one by one [off the truck] into the bush and did what they wanted with them—they raped them. There were many attackers, I think about 10. I was in the middle of the group on the truck and he caught me and took me to the bushes and he pointed the gun to me and he said, “Take off your cloth and lay down.” He had a gun and I was scared. There was nothing I could do. One of the men told the women to hurry up; they were taking all the women into the bush and raping them. Many women were crying and [the coupeurs de route] said, “Shut up or I will kill you….” My sister was in the vehicle coming from the market the week after—they attacked the vehicle and my sister was raped. There were a lot of women with that group also.[69]

Many women and girls taken from transport vehicles described being subjected to gang rape. A 36-year-old driver in Man who had been victim of multiple bandit attacks described the “worst one,” which happened in April 2010:

They raped one girl … it was right in front of me. When they finished taking money, they took the girl—she couldn’t have been more than 18 years old, and I would guess around 16—and separated her from the rest of us. But not far, just five or ten meters. She was the prettiest and the youngest of the women in the car—I think that’s why they chose her. Two of them raped her while three kept guard on the rest of us. We couldn’t do anything, the guns were pointed at us. She was screaming, screaming so loud, crying out. It was horrible. One finished, and then the other started. She never stopped screaming the whole time. And we all just lay there, listening…. We took her to the hospital after, it was the only thing we could do.[70]

Underreporting of Sexual ViolenceDetermining the full extent of sexual violence in western Côte d’Ivoire is challenging for multiple reasons. In the vacuum left behind after the armed conflict, there is still no functioning judicial system in which cases can be pursued or documentation collected. Victims of sexual violence and representatives of local women’s organizations all told Human Rights Watch that police and gendarmes often demanded bribes and, whether paid or not, consistently took little or no action when women filed complaints. As a result, the women said that they lacked confidence in the police and gendarmerie to investigate, and felt deterred from reporting incidents of rape due to the lack of a functioning judicial system. Additionally, women do not report cases of sexual violence out of the fear of reprisal from perpetrators, cultural and societal taboos, and a lack of financial resources to pay for health services or bribe police—all of which pose barriers to women’s perceived and actual ability to report and obtain assistance and justice. In particular, many women stated that police and gendarmes demanded a medical certificate, which had to be obtained at a hospital at a cost of 30,000 CFA ($60), in order to file a complaint—despite this not being required by law. The cost is exorbitant for the vast majority of women in western Côte d’Ivoire.[71] Human rights and humanitarian organizations working on sexual violence issues, as well as community-based women’s groups, told Human Rights Watch that the number of actual cases of sexual violence cannot be accurately gauged by the statistics kept by organizations and government institutions because they generally include only the few who find the means, courage, and support to report the crime and seek assistance.[72] Despite the lack of data, the cases documented by Human Rights Watch and the statements from scores of witnesses and community members who were aware of the frequent unreported incidents in their communities, strongly indicate that rape and other forms of sexual assault are widespread in western Côte d’Ivoire. |

Sexual Violence during Home Invasions

Sexual violence often accompanies home robberies perpetrated by criminal gangs, contributing to the perception of residents in western Côte d’Ivoire that nowhere is safe. Human Rights Watch documented 11 such cases of rape in Moyen Cavally and Dix-Huit Montagnes committed between January 2009 and July 2010.

In some instances, the victims believed that sexual violence was used to frighten their husbands into giving all the money kept in the house. The sexual assaults are generally perpetrated against all women present in the house. A 25-year-old victim of a home attack in Guiglo described what happened to her family:

Two men entered—one with a Kalash and one with a pistol. There were more outside…. I was laying next to my husband sleeping and they picked me up by the cloth. One of the men took me outside, [where] I saw another two men raping my niece. He told me to take off my cloth and I said I was having my period. He said, “You are lying,” and he threw the cloth away and raped me. Then the second one came and saw the blood and said he would not touch me because I was dirty, he then told me to go and tell my husband to give them all his money or he would spill our blood.[73]

Some victims reported being gang raped, like this 61-year-old widow and mother of six who was the victim of an attack in January 2009:

It was night and I was sleeping and they came and knocked at my door. I had a lamp in my room and they pushed the door and broke the lamp. There were four men. They asked me, “Where is the money?” When I said I didn’t have any, one pushed me and he fell on top of me. I fell down on my back and he lay down on me and he took off my cloth and threw it aside. He said don’t talk and put his hand over my mouth. He had sex with me. All four of them raped me and fled. They didn’t rob me as I have nothing to take.[74]

In a separate incident in July 2009 in Dix-Huit Montagnes, a 35-year-old woman described a violent home invasion in which she and her husband were brutally attacked and she was bound and gang raped. She was unable to see her attackers because her head was covered with a pillow case, and so could not be sure of the exact number of men who raped her:

They pushed the door and my husband and I were overwhelmed as they entered. The first robber hit my husband on the side of the head and the second on the waist. He was bleeding a lot. My husband told me to stand behind him…. One of them grabbed me by the shirt and put a machete to my neck. He told my husband, “If you don’t stop being brave, I will kill your wife.” … They took a sheet and covered my husband’s head. They told me to lie down and said, “Give me money.” My husband said he did not have his salary yet, and the bandit said, “In that case, we will kill you.” … I told them I had many pieces of material and they should take it, but they said it was not enough. I said, “Take my jewelry box,” but they said it was not enough.… Finally they covered my head and with a machete they cut my underwear and clothes…. With my husband next to me, they started to rape me. I didn’t say anything and was just hurting inside. My head was covered; I don’t know how many of them passed through and raped me. I was covered in blood. It’s still on the wall of my bedroom.[75]

Sexual Violence while Performing Daily Activities

Human Rights Watch also documented cases of women and girls who were attacked and raped as they walked home from work or the market, tended their fields, and foraged in the forest for food or wood. In Danané, a 15-year-old girl described to Human Rights Watch being raped by two men in May 2010 on her way home from her apprenticeship:

I was coming from work and going to cross the river—I have to use a secondary road to do this. It was 7 in the evening. I went down the road and four men came up behind and jumped on me. Two of them caught me and held me and two of them raped me. There was nothing I could do.[76]

In several cases documented by Human Rights Watch, attackers raped women carrying infants on their back as they returned home from local market. A 32-year-old woman described what happened to her and four other women as they returned from market in January 2010:

We were far from my house in the forest; I was with my baby when [the bandit] stopped us in the middle of the road. They caught me and they said, “Take off the baby,” and they took my baby and threw him on the ground. They beat me and beat me with the end of the Kalash. My baby was in the bushes and they raped me.… After they finished I went to pick up my baby. They beat me, and again my baby fell down.[77]

In the same incident, a 20-year-old woman who was three months pregnant recounted being raped despite pleading with the attackers:

He caught me and told me, “I am going to have sex with you.” I told him it was sacrilege because I was pregnant, but he didn’t say anything. When I said I could not do it he said, “If you don’t, I will kill you.”[78]

No One Is Spared: Women and Girls of All Ages at RiskHuman Rights Watch documented eight cases of girls being raped by bandits and other unknown attackers, including three teenage girls who were raped during a home invasion and arrived at a health facility in Dix-Huit Montagnes while Human Rights Watch was carrying out its investigation.[79] Among these eight cases, Human Rights Watch documented sexual violence against infants as young as seven months old.[80] The infant’s aunt explained to Human Rights Watch that her two nieces—seven months old and two years old—were raped by an unknown attacker in January 2010 while sleeping in a field, as their aunt who was caring for them was tending to her crops only meters away.[81] In another case in Dix-Huit Montagnes, a 16-year-old girl described to Human Rights Watch how she was raped while looking for food in February 2009: I was just walking not far from my house and a man, I didn’t know him … he raped me. He didn’t say anything, he was dressed all in black and he raped me and he left. I started to cry and I went home but I didn’t tell anybody. I was scared because I was alone. I had never had sex before and I became pregnant after this and now I have a baby.[82] Human Rights Watch also documented several cases of rape carried out against women over 60 years old. One was attacked in her home, while two others described being raped on their way to market. Josie (not her real name), a 78-year-old woman, described to Human Rights Watch how she was raped in January 2010 while walking to town: I take grain and palm nuts and I bring them to the town and sell them to help my family to live. One day on my route I met four men. I thought they were going to the village also. When I arrived closer, they said, “Old woman your life is finished today.” I said, “Young man, I am old, don’t kill me.” They said, “Mama you think we are just going to kill you? We are going to do more than just kill you.” … They took my basket and threw it into the river. They took me and dragged me into the bushes … and they did anything they wanted with me, they raped me…. Two of them raped and two of them stood guarding.[83] |

Consequences of Sexual Violence

The women and girls interviewed by Human Rights Watch described severe physical and emotional scars as a result of the sexual violence they had endured, including the inability to conceive. Others described how fear of attack had led them to considerably alter their lifestyle. A 39-year-old Burkinabé woman who had been raped by coupeurs de route on the way from market in January 2010 explained: