“I Want to Help My Own People”

State Control and Civil Society in Burma after Cyclone Nargis

Maps

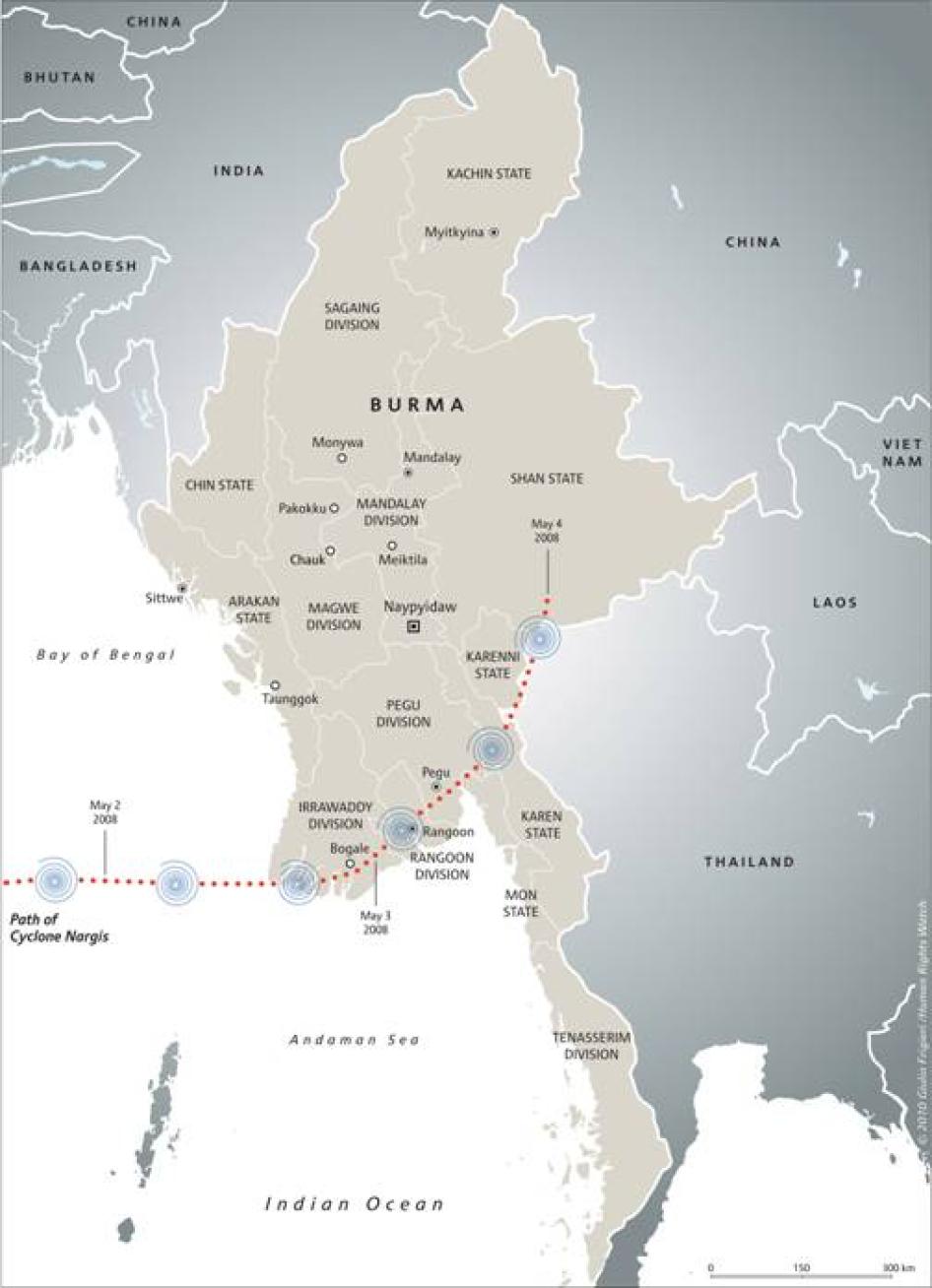

Path of Cyclone Nargis

© 2010 Giulio Frigieri/Human Rights Watch |

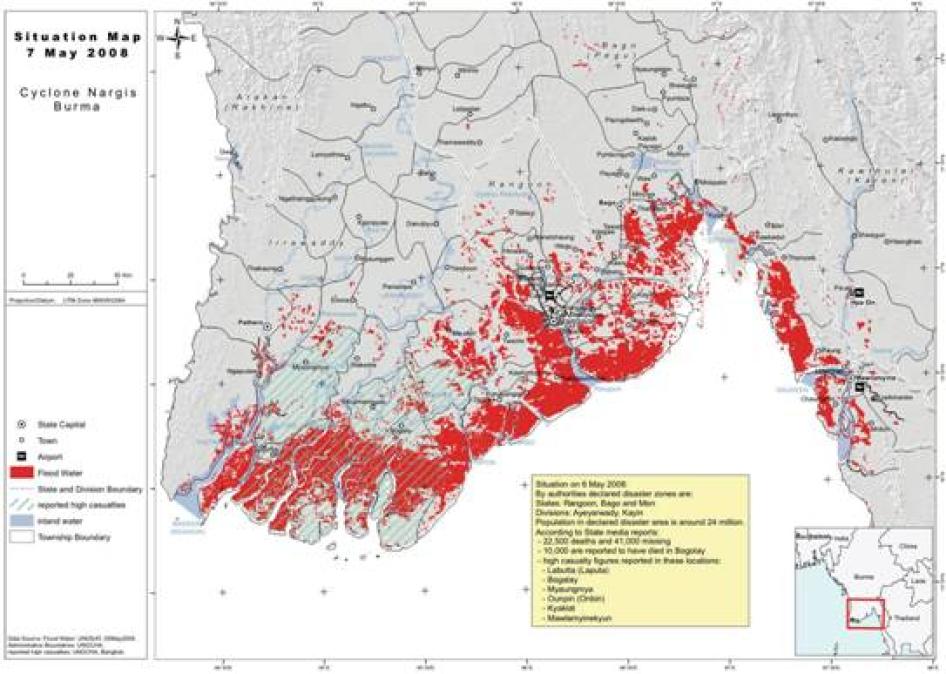

Cyclone Nargis Situation (May 7, 2008)

Adapted with permission of the copyright holder, using original source materials from UN agencies and the PONREPP. |

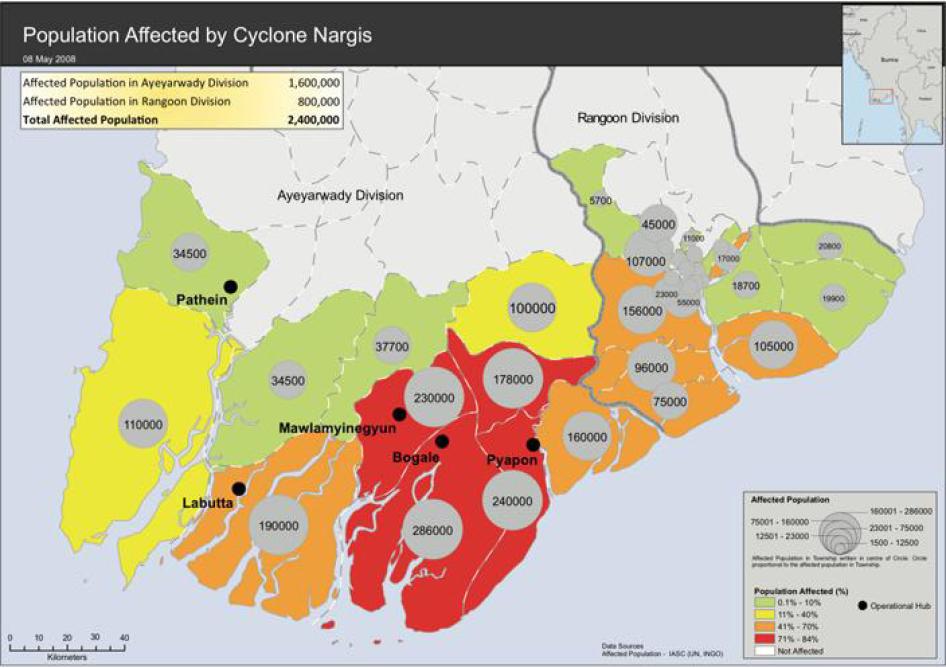

Population Affected by Cyclone Nargis (May 2008)

Adapted with permission of the copyright holder, using original source materials from UN agencies and the PONREPP."> |

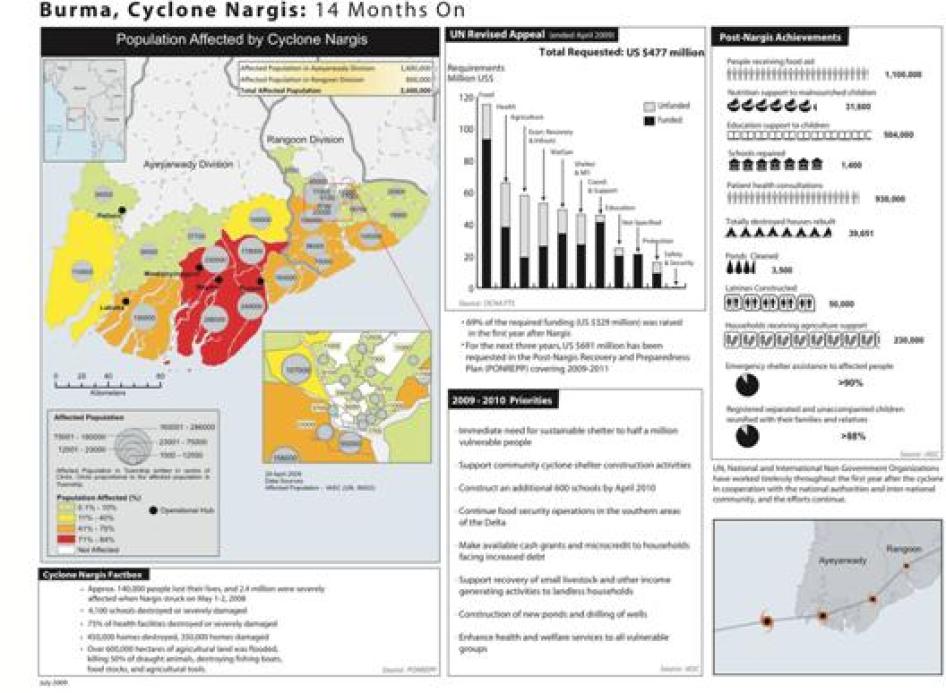

Cyclone Nargis 14 Months On (July 2009)

Adapted with permission of the copyright holder, using original source materials from UN agencies and the PONREPP. |

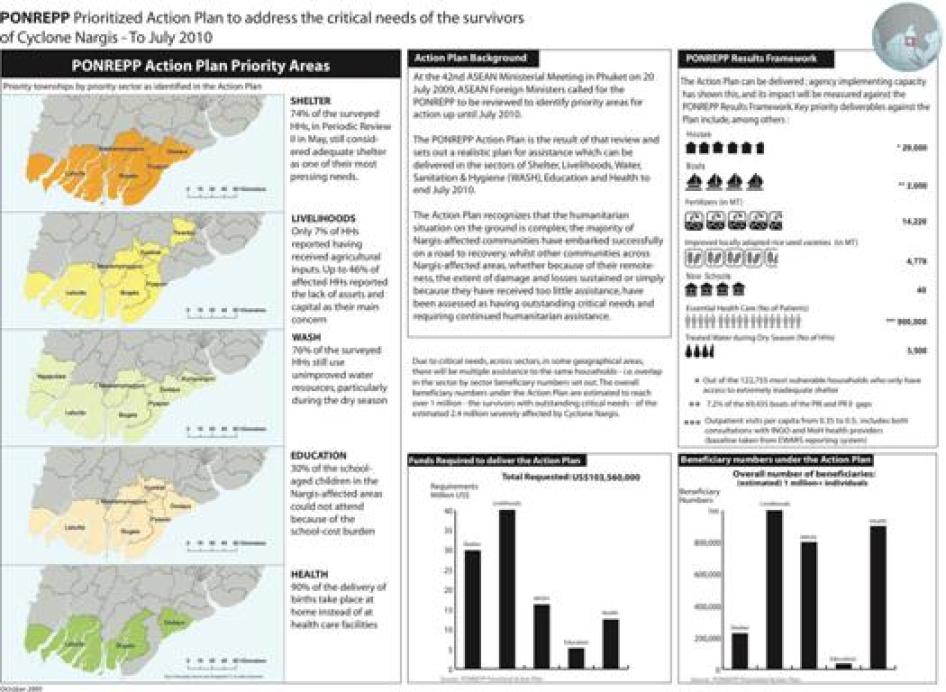

PONREPP Prioritized Action Plan to Address the Critical Needs of Survivors of Cyclone Nargis (to July 2010)

Adapted with permission of the copyright holder, using original source materials from UN agencies and the PONREPP. |

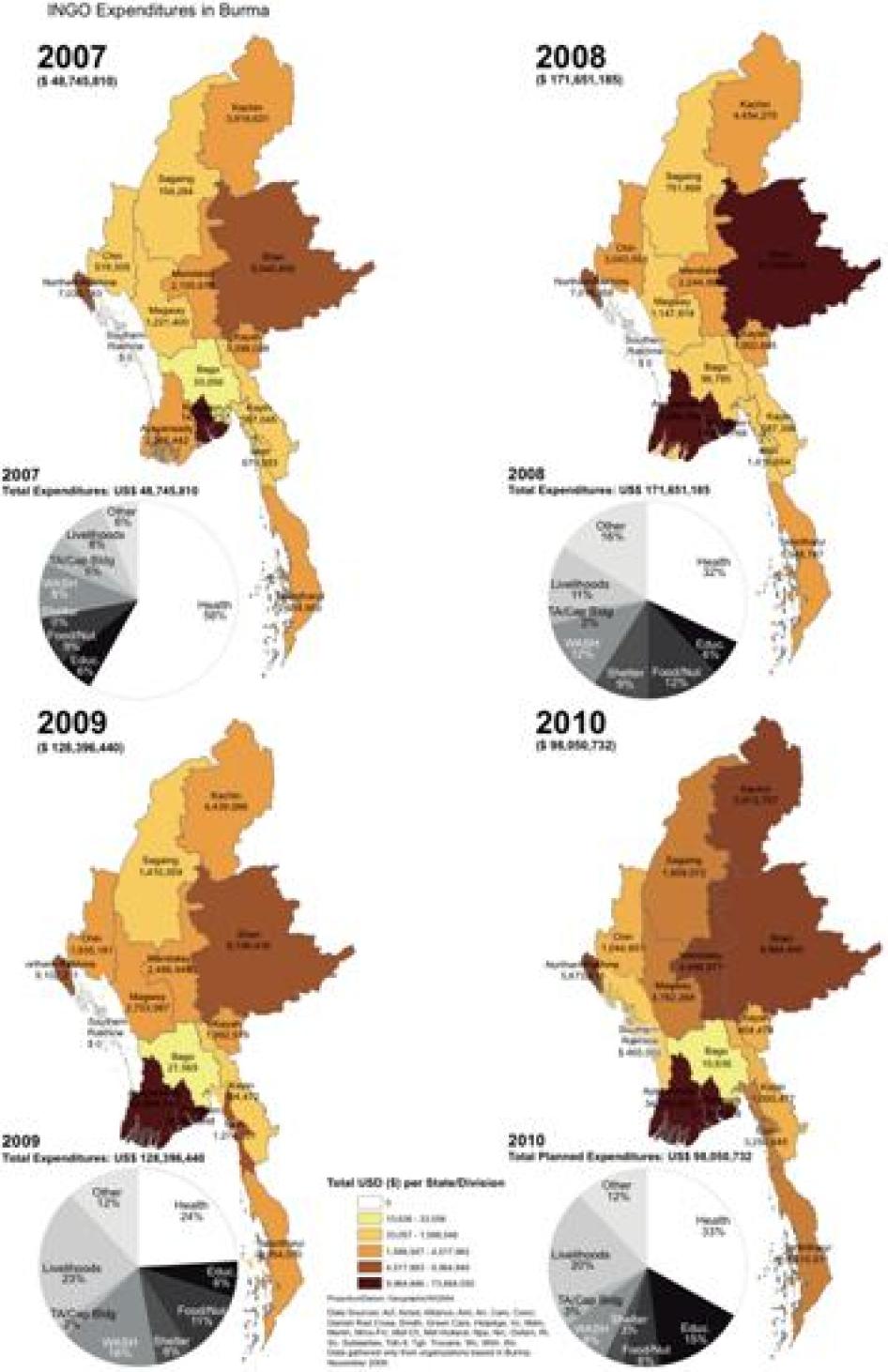

INGO Expenditures in Burma (2007-2010)

Adapted with permission of the copyright holder, using original source materials from UN agencies and the PONREPP. |

Summary

I want to save my own people. That’s why we go with any donations we can get. But the government doesn’t like our work. It is not interested in helping people. It just wants to tell the world and the rest of the country that everything is under control and that it has already saved its people.

—Comedian and activist Zargana prior to his arrest, Rangoon, June 2008

It was Cyclone Nargis which created the space for us to engage in humanitarian work, not the government.

—Director of a Burmese humanitarian group, Rangoon, March 2010

One of the most positive accomplishments of the cyclone response was to demonstrate the positive role that NGOs and the UN can play in a humanitarian response…. It is unfortunate that translating this good example from the cyclone response into other parts of the country has not happened yet.

—UN Resident Coordinator Bishow Parajuli, Rangoon, March 2010

Cyclone Nargis struck southern Burma on May 2-3, 2008, killing at least 140,000 people and bringing devastation to an estimated 2.4 million people in the Irrawaddy Delta and the former capital, Rangoon. The Burmese military government’s initial reaction to the cyclone shocked the world: instead of immediately allowing international humanitarian assistance to be delivered to survivors, as did countries affected by the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, the ruling State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) prevented both foreign disaster relief workers and urgently needed relief supplies from entering the delta during the crucial first weeks after the cyclone.

The military government blocked large-scale international relief efforts by delaying the issuance of visas to aid workers, prohibiting foreign helicopters and boats from making deliveries to support the relief operation, obstructing travel by aid agencies to affected areas, and preventing local and international media from freely reporting from the disaster area. Rather than prioritizing the lives and well-being of the affected population, the military government’s actions were dictated by hostility to the international community, participation in the diversion of aid, and an obsession with holding a manipulated referendum on a long-delayed constitution.

In the face of the government’s callous response, Burmese civil society groups and individuals raised money, collected supplies and traveled to the badly affected parts of the Irrawaddy Delta and around Rangoon to help survivors in shattered villages. Many efforts were spontaneous, but as the relief and recovery efforts gained pace, dozens of community-based organizations and civil society groups organized themselves and gained unprecedented experience in providing humanitarian relief and initiating projects.

Access for United Nations agencies and international humanitarian organizations improved starting in late May 2008 after UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon visited the delta, and the UN and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) brokered a deal with the Burmese government. They established the Tripartite Core Group (TCG), which became the central vehicle for coordinating aid, improving access for humanitarian organizations to the delta, and carrying out the ensuing recovery efforts.

The two years since Cyclone Nargis have seen an unprecedented influx of humanitarian assistance to the delta, with a visible presence of local and international aid workers and improved access to provide humanitarian relief. While this opening has been rightly welcomed, it has not been the unmitigated success that many Burma analysts have portrayed it to be.

Humanitarian access to the delta improved significantly by Burma standards following the establishment of the TCG mechanism, but it has remained far short of international standards. And partly because of the access restrictions imposed by the SPDC, humanitarian funding has not been sufficient to meet the needs of people in the cyclone-affected zones. As a result, two years after the cyclone, the recovery of many communities in the delta remains limited, particularly communities far from the towns where most relief efforts were organized. Such communities face continuing hardships and difficulties obtaining clean water and adequate sanitation, health resources, needed agricultural support, and recovery of livelihoods. Had the SPDC not continued to place unnecessary restrictions on the humanitarian relief effort in the delta, the cyclone-affected population would be much farther down the road to recovery.

The Burmese government has failed to adequately support reconstruction efforts that benefit the population, contributing only paltry levels of aid despite having vast sums at its disposal from lucrative natural gas sales. Although the government has not announced total figures dedicated for cyclone relief and reconstruction, it allocated a mere 5 million kyat (US$50,000) for an emergency fund immediately after the storm. It is clear that its subsequent spending has also not been commensurate with available resources. Burma’s government is estimated to have more than US$5 billion in foreign reserves and receives an estimated US$150 million in monthly gas export revenues. The Burmese government channels the limited assistance it does provide through its surrogates and contracts awarded to politically connected companies, in an effort to maintain social control. In addition, the government’s distribution of aid has been marred by serious allegations of favoritism.

In most areas of Burma outside of the cyclone-affected areas, international humanitarian access is much more limited than in the delta, despite significant levels of preventable disease, malnutrition, and inadequate water and sanitation, particularly in the central dry zone and the ethnic minority areas of the border states. All of the UN staff, Burmese aid providers, and international humanitarian organization representatives Human Rights Watch spoke with in Burma in early 2010 praised the humanitarian opening in the delta, but then added that humanitarian space in the rest of Burma remains a major challenge. As one senior aid official told us: “We were all hoping that the Nargis experience would be the wedge to open a lot of things, but this hasn’t happened.”

The statistics speak for themselves: approximately one-third of Burmese citizens live below the poverty line. Most live on one to three US dollars a day, and suffer from inadequate food security. Maternal mortality is the worst in the Asian region after Afghanistan. While the economies of many of its neighbors rapidly develop, the people of Burma continue to suffer. The SPDC fails to invest its own available resources to address urgent social and economic needs and blocks the humanitarian community from doing all it can to help meet those needs in other parts of the country.

A number of humanitarian aid experts we spoke with were hopeful that after national elections scheduled for the end of 2010 are completed, they will then be able to build on what was achieved in cyclone-affected areas, and expand the delivery of humanitarian aid to other areas in Burma where it is desperately needed. While the record of the Burmese government to date suggests this will be an uphill battle at best, the UN, ASEAN, and other influential international actors in Burma should make it a priority to continue to press for such expanded access.

Natural disasters can sometimes work as a catalyst for peace-building and reform in conflict wracked societies, as occurred in Aceh, Indonesia, following the 2004 tsunami. In Burma, the military government is stronger and more confident two years after the cyclone, but it is no more accountable or respectful of basic rights.

* * *

This report is based on extensive interviews with cyclone survivors, local and international aid workers, and other knowledgeable sources. It assesses the human rights impact of Cyclone Nargis and provides an often neglected human rights perspective on what is happening in cyclone-affected areas today. The last chapter of the report looks at the humanitarian situation in other parts of the country and the failure of the humanitarian opening in the Irrawaddy Delta to be replicated elsewhere.

This report is not a critique of humanitarian operations inside Burma, either during the Cyclone Nargis relief and recovery operations, or more generally throughout the country. It has been longstanding Human Rights Watch policy to support an increase in humanitarian assistance to Burma, albeit with recognition of the fraught human rights challenges posed by such operations in so oppressive a political environment as Burma.

Finally, this reports details an under-appreciated positive legacy of the cyclone response: the development of a group of new, truly independent and experienced civil society organizations in Burma, which now seek to use their skills to address other humanitarian and development challenges in the country.

Key Recommendations

To the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC)

- Immediately and unconditionally release all of Burma’s more than 2,100 political prisoners, including Zargana and 20 other Burmese aid workers arbitrarily arrested for their activities following Cyclone Nargis.

- End unnecessary restrictions on the operations and freedom of movement of Burmese and international nongovernmental organizations and UN agencies in the Irrawaddy Delta and throughout Burma.

- Ensure that scheduled elections in Burma in 2010 are conducted in a free, fair and credible manner. Discipline or prosecute as appropriate officials who engage in politically motivated harassment, intimidation and violence.

To United Nations Agencies

- Expand and strengthen the human rights protection, monitoring and reporting activities of the United Nations country team in Rangoon, and formalize existing protection mechanisms with an increased protection working group presence in Burma.

To International Donors

- Press the Burmese government to ensure unimpeded humanitarian access for local and international humanitarian organizations in cyclone-affected areas and elsewhere throughout Burma.

Methodology

For this report, Human Rights Watch researchers interviewed 70 Burmese survivors of Cyclone Nargis in 2008, and between October 2009 and March 2010. Inside Burma, Human Rights Watch also interviewed 25 Burmese and Western aid workers, diplomats, and visitors to affected areas. Human Rights Watch researchers conducted interviews in several townships of the Irrawaddy Delta, and in Rangoon. Researchers visited a combination of small villages in isolated areas, medium-sized towns, and township centers such as Bogale, Laputta, Pyapon, Dedaye, Kunyangaung and Haingyi. Further interviews were conducted in Bangkok, Mae Sot and Chiang Mai in Thailand.

Interviews were conducted in English, Burmese, and Karen. They were mostly structured around prepared questionnaires depending on the type of interviewee: ordinary Burmese citizen, Burmese community aid worker, Burmese staff member of UN agency or INGO, Burmese government worker or official, international staff member of UN agency or INGO, and Burmese or Western journalist. Everyone interviewed for this report gave oral consent for their testimony to be included in our reporting.

Researching human rights inside Burma is an extremely difficult undertaking because of the risk of government retaliation against Burmese nationals interviewed by Human Rights Watch. Intense and continuous surveillance of the population, and fear of repressive measures against those providing information to a human rights organization, makes human rights research in the country perilous.

We have given pseudonyms to all Burmese we interviewed and in some cases have withheld certain other identifying information to protect their safety. Locations of interviews done in Burma have also been generalized to the township level, so that those interviewed cannot be easily identified.

From May to August 2008 during the immediate post-cyclone phase, Human Rights Watch staff attended numerous meetings and press conferences of UN agencies and INGOs in Bangkok. During this period, we conducted more than 40 interviews with Western and Burmese aid workers and civilians who had just returned to Thailand after visiting the affected areas of the Irrawaddy Delta and Rangoon. Human Rights Watch researchers were unable to enter Burma at the time because of general visa restrictions. In March 2010, a Human Rights Watch researcher travelled to Burma to interview members of international and Burmese organizations involved in the cyclone relief operation and in ongoing reconstruction programs. In total, during the emergency phase and in the later research phase, Human Rights Watch interviewed 135 Burmese civilians, aid workers, and international aid workers, officials and journalists.

In preparing this report, Human Rights Watch also analyzed numerous UN and INGO reports, field updates, maps, and audio-visual materials from professional and private sources. The numerous cyclone “lessons learned” studies from UN agencies, practitioners and academics, together with the perspectives of many Burmese civil society organizations, were invaluable in framing this report.

I. Cyclone Nargis

The Storm Strikes

On the night of May 2, 2008, the largest tropical cyclone in Burmese history lashed the coast of the Irrawaddy Delta with winds and waves, and continued inland before petering out along the border with Thailand. Cyclone Nargis wreaked havoc all along its path, from the isolated villages in the waterways and marshes of the delta, to large towns and the former capital Rangoon, the country’s commercial center. The storm surge generated waves as high as four meters that washed away entire villages and swept inland as far as 30 kilometers. The combination of 160 kilometer per hour winds and massive waves destroyed houses and toppled trees, wrenched children out of the grasp of their parents, ripped people from shelters where they were seeking safety from the storm, and devastated crops and livestock in the agrarian food bowl of the country.

The cyclone ripped through the Irrawaddy division townships of Haingyi Island, Laputta, Bogale, Mawlamyinegyun, Dedaye, Twantay and several others before reaching the densely populated suburbs of Rangoon. Nearly 140,000 people are now known to have been killed in the course of several hours. For several months official government figures cited 84,537 dead, and 53,836 missing, a tally that would eventually be converted to reflect that all had died. An estimated 2.4 million persons in 47 severely affected townships desperately waited for aid to reach them. In these storm-hit areas, more than 50 percent of schools and 75 percent of health facilities were destroyed or damaged. In some areas, virtually all the houses were demolished.[1]

News of the true scale of the disaster was slow to come out of Burma, ruled by a military junta called the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC), which severely restricts local media freedom and goes to great lengths to prevent foreign journalists from traveling to the country. The death toll, first placed in the low hundreds, slowly rose as information became clearer. By May 5, the official death toll was placed at 10,000, the next day it was 22,000. Only by the end of the first week did official estimates climb rapidly to more realistic levels.[2]

As the magnitude of the cyclone became known to the outside world, a massive international aid program to assist millions of survivors was organized and then stalled by the SPDC. This chapter outlines the added risk to the life and well-being of the population that resulted from those early government actions and omissions. The SPDC, though aware of the impending storm, gave insufficient warnings to the population. The government imposed unnecessary restrictions on international aid agencies, including by delaying the issuance of visas. It unjustifiably restricted freedom of movement by aid agencies to affected areas, including through restrictions on transport and distribution, and travel restrictions on foreign aid workers. And it increased, rather than relaxed, existing controls over the domestic and international media, which deprived the population of potentially life-saving information.

Once relief aid got underway, the humanitarian problems did not end. The Burmese military erected roadblocks that were more closely linked to corruption than to providing security. Government entities diverted for their own purposes an unknown quantity of aid. And some cyclone survivors displaced from their homes were forcibly sent back to their villages that remained uninhabitable.

The delays imposed by the SPDC sparked global opprobrium and even calls for international intervention. The deadlock was finally broken by the formation of the Tripartite Core Group (TCG), a coordinating body lead by the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), the United Nations, and the SPDC.

Insufficient Government Warnings

The ferocity of Cyclone Nargis came as a surprise to many residents of Rangoon and the Irrawaddy Delta because they received little or no warning from the Burmese government.[3] The Indian Meteorological Department first detected Nargis on April 26 and the Joint Typhoon Warning Center promptly listed it as a tropical storm.[4] By April 29, there were clear indications that Nargis was a severe cyclonic storm heading for southern Burma, and the Indian Meteorological Department relayed warnings to the Burmese Department of Meteorology and Hydrology. The head of the Indian Meteorological Department, B.P. Yadav, later said, “We continuously updated authorities in Myanmar and on April 30 we even provided them [with] details of the likely route, speed and locations of landfall [of the cyclone].”[5]

On the morning of May 2, as Nargis swept towards the Burmese coastline, The Mirror, a major daily Burmese-language newspaper, published an interview with the head of the Burmese Meteorology Department, U Htun Lwin, in which he warned of a storm approaching that could bring 160 kilometer per hour winds.[6] The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) also issued a storm warning that day.[7] UN agencies based in Rangoon convened the Inter-Agency Standing Committee and the UN Disaster Management Team to prepare an emergency response.[8] Yet inexplicably, the Burmese government did not issue a wider alert or warning, leaving many in the delta unaware until the winds and rains intensified and made fleeing to safer areas difficult or impossible.

It is difficult to assess the impact a clearer warning about the impending storm would have had on the ability of the scattered, rural population in the delta to seek shelter. Many houses in the Irrawaddy Delta are fragile, made of wood, bamboo and thatch. But better warnings would have enabled more people to reach the few hard-walled shelters–mostly monasteries, churches and schools–in villages and towns, and many who survived did so because they reached such structures in time. Most of the initial mortality was due to the storm surge of four-meter waves reaching as far inland as 30 kilometers, easily sweeping away whole villages of lightly constructed houses.

Better warnings from the Burmese state-run television and radio media, relayed through to Burmese language radio stations abroad,[9] could have given communities several more hours to reach higher land or seek hard-walled shelters. As one meteorological analyst concluded, “Be it through lack of communication, insufficient warnings or a failure to realize the severity of the threat to the delta regions of the Irrawaddy, the lack of [official Burmese] response to the warnings resulted in a far greater loss of life than needed to occur.”[10]

Min Min Choe, a farmer on Haingyi Island, knew the storm was coming but did not think it would be different than the annual storm season. He told Human Rights Watch:

I heard the storm news on the radio. It didn’t contain any alarming facts. If the news had been announced seriously with possible impacts of destruction, we wouldn’t have lost so much. But, we were not informed about the estimated time when the storm would [make] landfall in our area, and where the eye of the storm would be. When they announced how serious it was, our area was already being pummeled by the storm.[11]

May Khin, a 45-year-old woman from a small village on the coast in Laputta township, was shocked by the force of Nargis:

Nargis was the worst experience of my life. The last thing I remember is the lightning coming together with a strong wind and later a giant wave covered my daughter and me while we were running to the monastery. Then we were separated. I was washed away by the wave and became unconscious. When I came around, there were no clothes on my body and I could not walk as I had no strength. Beside me there was a dead body. I was lying like that for two days I think. I tried very hard to look for my daughter. Later people with a boat rescued me. There was no warning about the storm.[12]

Ma Mei Mei, a laborer from Dedaye township, said:

We didn’t hear about this storm in advance. We lived outside the village, so we didn’t hear such news from the other villagers. My house was built up on the bank of the river. When the storm surge rose, we prepared to flee by boat, but, my husband was swept away. When the house collapsed, I was inside. My mother-in-law was killed in the collapse. I couldn’t help her as I had to struggle to save my child’s life and mine. We were swept away by the storm-surge, and at one place, we were stuck in a tree. The next morning, the water level started going down… we started seeing rescuers.[13]

Aye Aye Win, a young mother from Pyapon township, told Human Rights Watch:

We heard that a storm was coming, but there was no warning about the cyclone in our village. The cyclone started hitting us… We ran to high land. I lost my three children. Our house collapsed. Nothing was left. Everything was washed away… We had no time to prepare.[14]

Naw Paw Htoo, a young school teacher from Bogale, also didn’t hear any warning:

I was in the house with my brothers and sisters when the storm started striking. We wanted to go to the nearby granary... As soon as we stepped outside, the house collapsed. As the current was very strong I couldn’t swim so I tried to survive on the debris of the house. With my flashlight on, I yelled out ‘Help! Help!’ I saw my father before me in the current, he was trying to save my mother. I lost my mother, three sisters and two brothers. Only my father and I survived. In the debris of our house, I went to a wardrobe to take out some clothes and found my aunt and her husband had died with the wardrobe on top of them.[15]

Saw Lu, an ethnic Karen farmer from Kunchangone township, was watching state-run television on the night of the storm, and said that the storm news broadcast did not reflect the real intensity of the cyclone. He said:

I watched TV until 9.30 p.m. Around 10 p.m., it started raining, and the wind became a bit stronger. But, I told my wife ‘Don’t worry. It’ll soon be fine.’ But, around midnight, the wind suddenly became very strong... The house also started to tremble, making noises. We didn’t dare to stay any longer. When we went to my brother’s house, his house had lost the roof already. The strong winds were devastating, but, the flood was not that high in our village. The next morning, I found that the destruction was total.[16]

Saw Htoo Wah from Bogale, experienced the eye of the storm passing over his village:

There was some warning at 3 p.m. on Friday [May 1], but we didn’t hear it on the radio, other survivors told me the next day. The SPDC knew it was coming but didn’t tell anyone. [I think that] they don’t like us, they look down on their own citizens, they don’t care whether we’re dead or alive.[17]

Rangoon was hit severely by the storm, with power lines down, thousands of trees uprooted and serious damage to buildings and basic infrastructure. The river ports in and around Rangoon were severely damaged, large numbers of ships, big and small, were destroyed, and roads washed away. Tha Hla Swe, the head of the Myanmar Red Cross Society (MRCS), described the cyclone striking the city:

The night of the cyclone was like hiding beneath a Boeing 747 with all its engines on. The wind was roaring and you could hear trees snapping. Iron roofs were being ripped off, making an incredible sound. I remember hearing satellite dishes being ripped out and flying around. It was not until around noon the next day that the wind began to die down… The roads were impassable, blocked with fallen electric lines, trees, lampposts. Volunteers, soaking wet, were already trying to help clear the roads. Though the storm first struck at midnight on 2 May, it was not until late evening on 3 May that information began to reach us from the villages. The phones were all down and so it was not until people arrived by motorbike to report that we knew how serious the situation was.[18]

According to Htet Aung, then a political prisoner at Insein prison, after Cyclone Nargis ripped off the roofs of the prison, three or four inmates demanded to be moved to more secure facilities and rioting broke out. Guards shot into the air to bring order. The next day, Htet Aung noticed a disturbance in a nearby prison building at Insein:

I saw thick smoke from the main jail. Then I heard some shooting around 6 a.m. Prison officials and warders [guards] ran to that building. In the afternoon, when the storm [finished], some warders came back… A prison guard told me that there was a strike [riot] in the main jail. Prison guards tried to scatter the prisoners by shooting into the crowd. Some prisoners died. No prison officials gave attention to the prisoners’ troubles in the storm. Then next morning they got very angry and set fire to the prison cells. Several were beaten and shot to death by the guards.[19]

Initial reports after the cyclone claimed that from 12 to 40 inmates had been killed by the gunfire. The authorities ignored calls by the UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar for a thorough and transparent investigation into the killings.[20] During interrogations of more than 100 prisoners, aimed at uncovering the identity of the instigators of the riot, guards beat prisoners, and denied food and water for more than seven days during the interrogation proceedings. Nine prisoners reportedly died. More than 100 prisoners were given additional sentences of between two and twelve years following secret trials in the prison in late 2008 on charges related to arson, damaging government property and inciting a riot.[21]

Government Obstruction to International Relief Operations

Two days after the cyclone, on May 5, the UN country team in Rangoon held a meeting with the SPDC Ministry of Social Welfare, Relief and Resettlement and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and requested that the UN be allowed to coordinate international assistance. The government formed a National Disaster Preparedness Central Committee headed by Prime Minister Thein Sein, and allocated 5 million kyat (US$50,000) as an emergency fund. The townships along the cyclone’s path were declared national disaster zones.[22] UN agencies and international relief organizations established working “clusters”—collectives of agencies working in key areas such as health, shelter, and child protection.[23] But what should have been a highly coordinated, rapid relief operation soon devolved into a situation where relief supplies and emergency aid specialists waited for days and weeks while the Burmese government sharply limited access to cyclone-affected zones.

Under the UN Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement (IDP Principles), national authorities have the “primary duty and responsibility” for providing relief to displaced persons.[24] Nonetheless, international humanitarian organizations and other appropriate actors may offer their services, which is not to be regarded as “an unfriendly act or interference in a State’s internal affairs” and must be considered in good faith.” The authorities may not arbitrarily withhold consent, particularly when they “are unable or unwilling to provide the required humanitarian assistance.”[25] Instead, the authorities are to “grant and facilitate” the free passage of humanitarian assistance and grant aid workers “rapid and unimpeded access to the internally displaced.”[26]

An important part of the UN’s request to the government was to relax its stringent rules on issuing visas to foreign aid workers and waive or reduce customs and import duties on humanitarian aid. Other government restrictions hindering aid included the SPDC’s insistence that it receive all aid and distribute it through government agencies; travel restrictions on foreign disaster relief specialists, especially logistics and water and sanitation technicians, to travel to affected areas; and a ban on media access. Weeks after the cyclone, despite SPDC promises that restrictions had been waived or streamlined, many impediments remained. The ability of relief supplies to get through and aid workers to travel freely was far below what was needed and possible under the circumstances.

Just as international donors, UN agencies, and INGOs were organizing a massive response to send aid and relief workers into the country, the SPDC’s strict restrictions blocked many of these efforts. Key log-jams were its refusal to issue visas for foreign aid workers to enter Burma to organize relief efforts, and controls on the movement of personnel and transport and distribution of aid. In these decisions, the SPDC appeared to place priority on ensuring close control of the situation. The result was aid was extremely slow in reaching the victims of the cyclone at precisely the time when assistance was needed most, thereby contributing to unnecessary additional suffering and deaths.

Khin Mar Wai, a young woman from an isolated village in Laputta township, did not receive any direct assistance for more than a month after the cyclone. For weeks, she and other villagers had to walk and take small boats for nearly two hours to the main motor road into Laputta town to beg for food.

No one came to rescue us. When we heard there were donations in other villages, we went there and begged for food. We begged from the cars passing on the motor road. We got trouble from the authorities... When we saw cars passing on the road, we ran to the cars and asked for donations. Later we were forced to return to our village by the authorities. They said the local officials will come give us donations. We were threatened that we would be arrested if we did not return.[27]

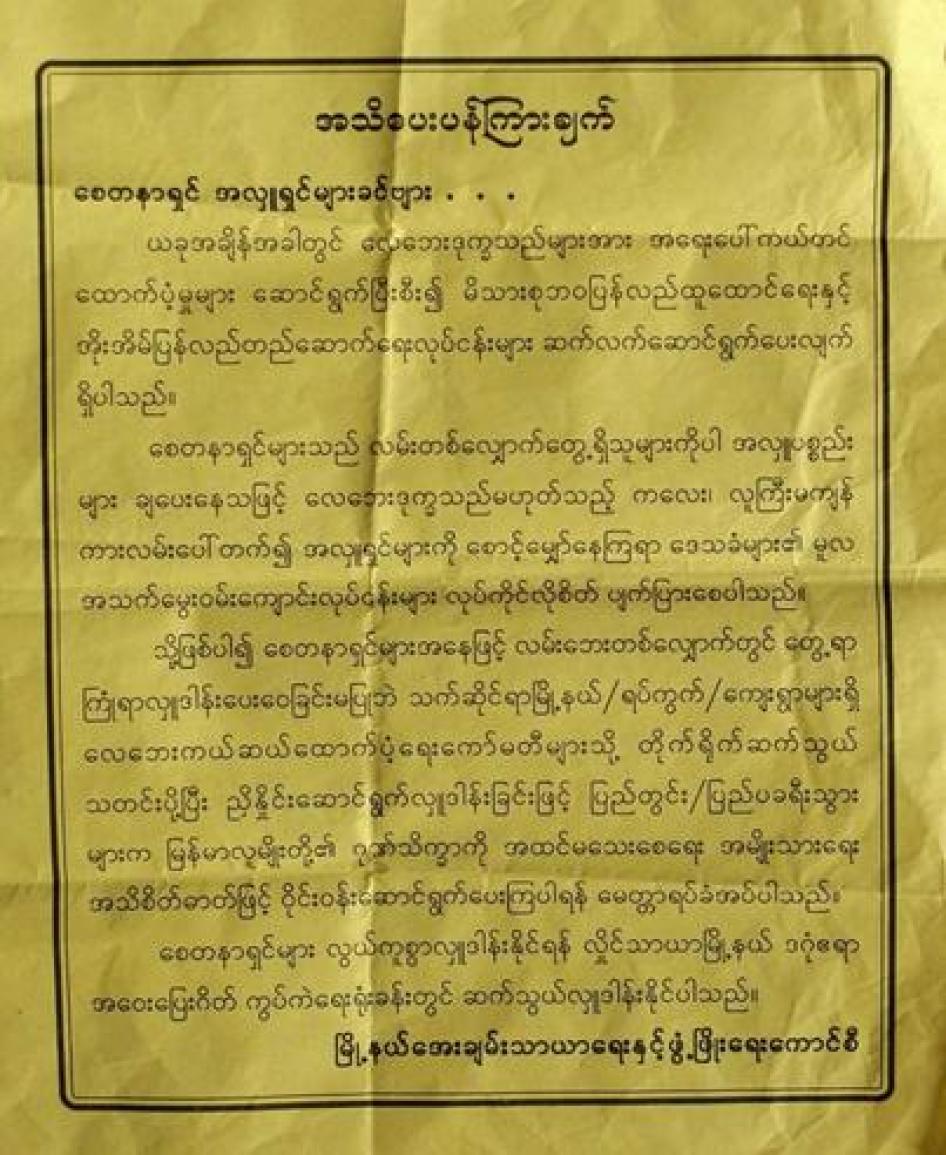

The SPDC even distributed a brochure at bus stations and along the roads leading to cyclone-affected areas which sought to deter private aid distribution outside of government control. The brochure, which appears below, stated:

Notice To philanthropists, donors… These days, we have finished providing emergency relief aid to cyclone victims and are helping victims reestablish family life and rebuild their houses. Because philanthropists have been donating items to people along the roads those who are not cyclone victims including both adults and children wait for donors on the streets. This destroys people’s motivation to return to their previous vocations. Philanthropists, therefore, should not donate items randomly to people along the roads, instead they should contact cyclone relief aid committees in related townships, quarters, and villages to inform them and to donate items through those committees. This will prevent foreign and local tourists from looking down on Burmese and lowering our dignity. We request that people work with national consciousness. Philanthropists can donate items easily through Hlaing Thaya Township, Dagon Aye Yar Highway Gate administrative office. Township Peace and Development Council.[28]

Khin Mar Wai told Human Rights Watch that in the days following the cyclone, the lack of food and clean water, combined with the continuing rains and lack of shelter, had a terrible impact on the old, young and injured.

Some older people and children died in front of me. I couldn’t help them because I had to go far to beg for food. There were many people who got sick and died. We did not receive any help from anyone for more than one month after Nargis. We could only come back to our village when a donor group led by the monks came to our area.[29]

Naw Ley Ley, a young Karen woman from a village near Bogale, a 20-minute walk from the coastline where half the residents were missing and presumed dead, told Human Rights Watch:

We expected that someone would come to help. We waited but no one came. After a week we started to move to look for food and water. There were a lot of survivors moving. At no point did we see aid being distributed. We only saw that later on Burmese television.[30]

Foreign aid workers stuck in Bangkok counted the small number of visas granted daily by the Burmese authorities.[31] Further delaying the movement of international disaster relief experts was the government’s evident preference for granting visas to Asian over Western staff, in particular those from ASEAN states. Medical relief teams from Singapore were permitted to travel to the affected areas soon after the cyclone, while disaster relief experts from Western countries were denied visas.[32] The United States Agency for International Development-Disaster Assistance Response Team (USAID-DART team) waited for weeks in Bangkok for official approval to enter Burma, as did many other emergency relief workers trying to reach the Irrawaddy Delta.[33] In an official statement on May 16, the Burmese government stated:

As the Government is facing huge amount of challenges, we are not yet ready to accommodate all visa requests made by various agencies and organizations. However, we have already authorized the visas for experts from OCHA, WFP, WMO, UNHCR, ICRC, EU and Medicins Sans Frontieres. The Government has also invited medical doctors and nurses from Myanmar's five immediate neighbors—Bangladesh, China, India, Laos and Thailand to reinforce the health care activities.[34]

On May 9, the UN World Food Program (WFP) temporarily halted its airlift of supplies because government authorities had attempted to seize the WFP shipments and control its distribution. WFP regional director Tony Banbury told the media:

We’re going to have to shut down our very small airlift operation until we get guarantees from the authorities. It should be on trucks headed to the victims. That food is now sitting on a tarmac doing no good.[35]

After negotiations between the WFP and the Burmese government, the SPDC agreed later that day to allow WFP to distribute its own aid. But the authorities continued to maintain cumbersome customs clearance procedures and instituted other bureaucratic delays, effectively ignoring the WFP’s earlier requests to waive many of these provisions.[36]

The Burmese military used only one helicopter in support of the operation, although other government helicopters were ferrying officials on inspection trips. The government refused to permit UN agencies to bring in helicopters until early June. Waterborne transport of supplies through the river network of the delta only started to increase one week after the cyclone.[37]

The situation became so dire that on May 12, UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon publicly took the government to task over the continued impasse in permitting aid and disaster response experts into Burma:

I want to register my deep concern—and immense frustration—at the unacceptably slow response to this grave humanitarian crisis. Unless more aid gets into the country—very quickly—we face an outbreak of infectious diseases that could dwarf today’s crisis. I therefore call, in the most strenuous terms, on the Government of Myanmar to put its people’s lives first. It must do all that it can to prevent the disaster from becoming even more serious. I emphasize that this is not about politics. It is about saving people’s lives. There is absolutely no time to lose.[38]

The secretary-general also expressed frustration that President Than Shwe had so far refused to accept his phone calls to try and negotiate a way out of the impasse.

Secretary-General Ban’s intervention with the Burmese government notwithstanding, two weeks after the cyclone struck, the UN Office of the Coordinator for Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) was still reporting that “the levels of aid getting in to the country remain far below what is required to meet the needs on the ground.”[39] At that point only slightly more than half of the 2.4 million cyclone survivors had received some sort of aid. Aid agencies raised fears of a secondary wave of mortality through spread of diseases if immediate action was not taken to address sanitation, drinking water, and the spread of communicable disease due to overcrowding at relocation centers.[40]

Restrictions on Access and Movement in Cyclone-Affected Areas

On the ground in the Irrawaddy Delta and around Rangoon, many international and Burmese organizations did not wait for permission to take action. INGOs that had operated for years in the cyclone-affected areas—such as Save the Children, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), Merlin and others—began transporting supplies and assisting survivors. Numerous Burmese groups, ranging from existing community development collectives to more ad hoc groups, began raising money and collecting goods to transport to badly hit areas.

The military quickly began erecting road and river checkpoints to regulate movements. While ensuring security in humanitarian emergencies is a valid and necessary government function, the main purpose of many of these checkpoints appeared to be to restrict or even block urgently needed supplies and relief personnel. On May 13, new checkpoints created on most of the roads leaving Rangoon began screening all foreigners trying to reach the Irrawaddy Delta. Tim Costello, head of World Vision Australia, arrived in Burma soon after the cyclone to coordinate his agency’s emergency response. He was scathing about the new travel restrictions even after his personal interventions with a Burmese general permitted World Vision staff to bypass some of the obstacles:

We negotiated a space with the military where we deliver the aid, not them. And we're getting through those military checkpoints. But this is causing deep frustration and even guilt for our workers that they can't reach more people. The [military’s] narrative is that the military created the nation, protects the nation, and will save the nation without ex-pats coming in to do it. It would be incredibly helpful if we could get ex-pats in because of their expertise in water and sanitation systems, but we just cannot get them in. Most countries understand we are not out to breach national sovereignty and only want to do for you what you can’t do for yourself. The junta simply doesn't understand that humanitarian idea. They won’t trust us.[41]

Bruno Jochum, director of operations for MSF, deplored the government restrictions even as hundreds of the organization’s Burmese national staff members were organizing relief operations in the delta. He said at the time:

Although MSF is able to provide a certain level of direct assistance, the overall relief effort is clearly inadequate. Thousands of people affected by the cyclone are in a critical state and are in urgent need of relief. The aid effort is hampered by the government-imposed restriction on international staff working in the Delta region. For example: despite the fact that some MSF water and sanitation specialists have been granted visas to enter Myanmar, they have not been permitted to travel into the disaster area, where their expertise is desperately needed.[42]

The SPDC’s fear of foreign intervention was most evident in the rejection of nearly all direct assistance from Western warships off the coast of Burma. Military vessels laden with emergency assistance from the United States, the United Kingdom and France waited for permission to airlift or land their emergency relief supplies. None ever received it. The USS Essex and its support ships sailed away from the Burmese coast on June 4, after 15 unsuccessful attempts to gain permission to land relief supplies.[43] The British frigate HMS Westminster arrived off the coast of Burma on May 18 and was replaced on May 25 by HMS Edinburgh. Both ships were to conduct relief assistance duties as part of “Operation Songster” but when Burmese government permission was not forthcoming, they abandoned the mission and departed from the Burmese coast on May 28. The French amphibious landing ship Le Mistral arrived off the coast on May 17, carrying 1,000 tons of supplies, but was never able to land them in Burma. It too sailed from Burmese waters in late May and offloaded its supplies at a port in Thailand to be flown into Burma.

On May 11, the commander of the US Pacific Fleet, Adm. Timothy Keating, the director of USAID, Henrietta Fore, and the State Department’s ASEAN ambassador, Scot Marciel, flew to Rangoon’s Mingaladon airport to speak with senior SPDC officials about expanding the relief operation and utilizing the full complement of US military aid and logistics in the area. Afterwards, Admiral Keating said he told SPDC officials:

One, we were ready to provide relief assistance immediately. Two, we were capable of moving 250,000 pounds or so a day of relief material into Burma. We were capable of moving it from the central distribution point there at Rangoon out to the areas needing the relief supplies, using our medium and heavy-lift helicopters. We would come in, be entirely self-sufficient. We would come in, if they chose, at first light and leave every evening. We offered them the opportunity to put their own military members or civilians, their choice, on our airplanes, on our helicopters. And I said… once you tell us we’re done, we will leave, you will not know we were here. The delegation accepted my comments and said, ‘We understand, we acknowledge, but we cannot approve. This decision has to be made at the very highest levels of our government, and we will take your recommendation to the highest levels of our government.’

We have been moving about five C-130 [transport aircraft] loads a day… The goods end up in Rangoon. Subsequent distribution is handled by non-governmental organizations to a limited degree, and to a larger degree by the government of Burma. Do we know where they’re going? I do not necessarily know where those relief supplies are going. That is why we continue to emphasize our desire to put helicopters into Rangoon and the surrounding countryside so as to assist in the further distribution into the Irrawaddy Delta, where we are convinced that the help is needed most desperately…. As yet, we don’t have permission from Burma to conduct those operations.[44]

The delay in granting access to affected areas and establishing an effective mechanism for aid distribution caused problems for the village chief in an isolated village in Pyapon township, where all 100 houses were destroyed during the storm. Htoo Htoo Lay told Human Rights Watch:

Our village was not on the lists of WFP to receive rice because they didn’t know our village. Our village is not on the map of Pyapon township. When we didn’t have food assistance from agencies, all the time we worried so much about the food. Our food stocks were damaged. We had to eat only wet spoiled rice. The most serious problem was to find water. Clean, safe water was unavailable. We had to dig the sand with our hands for water. However, only sort of salty water came out. We had to drink it, as there was no option.[45]

The village received government assistance only once, 10 days after the storm, when a Burmese military helicopter dropped water bottles and high energy biscuits. It was nearly two months after the cyclone that the first effective outside assistance reached his village.

MSF came to our village. Only when I met them in a nearby village [a 45-minute walk], did they come to know our village was also in need of help... They are the first group that came and helped us. They gave us clothes, thatch for roofs, and ropes to use in building makeshift houses. Soon after, [Burmese rock star] Zaw Win Htut came and built a new school. Zaw Win Htut also gave some rice to the households.[46]

Restrictions on Domestic and Foreign Media

Even as the military government was obstructing the relief operation, the official commentary in the state-controlled media portrayed the SPDC as being fully in charge of the operation. Burmese television and print media extensively covered incoming aid flights, even announcing the number of daily flights, the tonnage of supplies delivered, and the source countries and organizations.[47] Burmese soldiers were prominently featured clearing trees and debris from the streets. Senior generals were shown handing out relief supplies in the affected areas and visiting tent cities of survivors. State-run media also tried to compare the international outrage over the government’s obstructions with the slow response by the US federal government to Hurricane Katrina in August 2005.[48]

Foreign and Burmese journalists were officially denied access to the badly hit areas, but that did not deter scores of reporters and film crews from traveling without government approval to the worst affected places. Foreign journalists moved around constantly and avoided registering in hotels and guesthouses in the delta, as this was a sure way for the authorities to track them down. Christian Holst, a European photographer, told Human Rights Watch he was able to stay one step ahead of the authorities by sleeping overnight in his hired car.[49] Some correspondents were not so fortunate: Time magazine reporter Andrew Marshall was caught by authorities and deported two weeks after the cyclone. He wrote later:

the junta’s pitiless response to the cyclone is alienating the very people it depends upon for its own survival. One young Special Branch officer at the airport seemed embarrassed to be expelling a foreign journalist whose only crime was trying to publicize the plight of Burmese disaster victims. ‘Please forgive me,’ he kept telling me. ‘Please forgive me.’ I now realize he wasn't embarrassed at all. He was ashamed.[50]

The authorities detained British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) reporter Andrew Harding as he tried to enter Burma on May 6, and sent him back to Thailand on the next available flight. The state run media justified Harding’s denial of access by asserting: “Journalists from news agencies in western countries illegally entered the country very often and made fabricated news with the help of anti-government groups.”[51]

CNN reporter Dan Rivers and his film crew were pursued for a week in the delta just days after the cyclone, hiding in the back of cars, walking through the jungle to sneak into villages to interview survivors, bluffing their way through checkpoints, and sending out broadcasts of the scale of the disaster. Rivers was eventually detained and questioned by authorities after boarding a flight to return to Thailand on May 9. He commented on the SPDC’s response and their efforts to curtail the work of journalists: “The whole country is kind of a basket case. Combine that with a disaster on this scale and a government that won’t let anyone in, they’re turning a bad situation into...what really is criminal negligence on a massive scale…The more resources are spent chasing me, the less they're going to be concentrating on actually helping people.”[52]

The Burmese media were able to travel clandestinely to the delta and affected areas much more easily than Westerners, and helped immeasurably in getting information out to exiled radio stations, news services, and in assisting the international media who were under more restrictions.

Diversions of Relief Aid

There were many reports of aid diversions in the early weeks after the cyclone. Officials at all levels–from local officers to senior generals—were presented multiple opportunities to benefit personally from the unprecedented levels of international and domestic aid pouring into the cyclone-affected areas. Despite official announcements that aid embezzlement was illegal, there are credible reports that officials diverted aid for personal profit, to supply their own military units, or to favor communities to which they had some connection. The Guiding Principles on internal displacement provide that humanitarian assistance to internally displaced persons “shall not be diverted, in particular for political or military reasons.”[53]

The SPDC denounced reports that aid was being diverted, referring to “foreign media making false allegations and criticisms against the Government of Myanmar.”[54] The National Disaster Preparedness Central Committee announced:

Anyone may inform if he [sic] witnesses or knows that the cash assistance and relief supplies donated to the storm victims are kept for self-interest, traded, used for particular persons and organizations, or misappropriated for other purposes. We hereby announce that we have made all necessary arrangements to conduct investigation into the cases to expose the offenders and take punitive action against them in accordance with the law.[55]

Pu Me Le, a young Karen woman from Laputta, said that her village head abused his position to take aid supplies in the weeks after the cyclone:

Our village head did not allow the full distribution of the foreign aid, it all had to come through him and he kept about one-third of the goods. Later, ADRA came and distributed it themselves because they knew it was happening... The village head is selfish... He is still the head of the Ya Ya Ka [village council], he’s also the local leader of kyaing-phut [the government mass organization, USDA].[56]

Khin Myae, a Burmese doctor with MSF, was in Haingyi on May 8 with a team of MSF medics when one of his staff alerted him to attempts by the army to control distribution of MSF’s aid supplies. He wrote:

‘We have a problem,’ shouted Cho Aung, one of the logisticians. ‘The army wants to distribute our rice.’ When I went to look, I saw a few soldiers unloading our supply of rice. I ask them what they’re doing and the soldier in charge tells me that the army is organizing distributions in this area and that they want to give out our food supplies. I ask to speak to their commander and, in a long conversation, explain that we are MSF and that we’ve come to help and that we are on our way to villages to distribute our own supplies. Finally, we got our supplies back.[57]

Pat Brown, a photographer on assignment for Human Rights Watch after the cyclone related how he and a journalist colleague observed diversion of aid while traveling on a riverboat delivering aid:

We pushed off about 5 a.m. and set off to the eastern delta down the Rangoon River. As dawn broke, we were allowed to come out for some air, but it wasn’t too long before we were getting shouted at by our guide. Coming up was a Navy check point, a patrol boat—we jumped back down [into the engine room]. The [Burmese navy] officer shouted through a bullhorn for our boat to come closer. They captain did exactly what he said [but pretended] he couldn't get the boat alongside the patrol boat as he said the current was too strong. The Navy officers questioned the crew for about five minutes. The crew shouted back that they were carrying aid to outlaying villages down river. The Navy officers said ‘Okay, but we want some of your rice,’ so a bag of rice came from our hiding spot and was handed over, all done without tying the two boats together.

Then from there it was smooth sailing until the next check point, but this time it was in a village that we were delivering the aid to. The Army captain this time came out and asked ‘How much aid do you have?’ then told the crew he wanted half of it. So his new-found wealth was off loaded. We carried on our way down river to our final destination, a small village at the mouth of the Rangoon River. This village was badly hit and yet only four people were killed. But the whole village was quite simply blown away… these people have nothing! They are receiving nothing from their government or the NGOs. This is only a six-hour slow boat ride from Rangoon city center. The aid that is getting to these people is being paid for and delivered by private donors.[58]

In one brazen case, donations from the foundation of the King of Thailand were stamped as coming from the largesse of Lt. Gen. Myint Swe, the head of the Bureau of Special Operations in Rangoon and other senior generals. Stickers in Burmese claimed the generals were donating the goods, obscuring a smaller label that said “Aid from the Kingdom of Thailand.”[59] The issue was widely reported, leading to a visit to Burma by then Thai prime minister Samak Sundaravej in mid-May, who quietly resolved the issue with Burmese authorities.[60]

Obstructions were also acknowledged in official ASEAN accounts of the post-cyclone response. According to Pavin Chachavalpongpun and Moe Thuzar, Thai and Burmese academics who wrote an account of ASEAN’s role post-cyclone:

In our conversations with the victims of Nargis, they expressed their frustration, being unable to understand why the government had denied international assistance, even when the affected people were desperately in need of help. They strongly voiced their opinion that the government had mismanaged its relief efforts, which contributed to the worsening situation in the affected areas. We were told that even the doctors who volunteered to work in the cyclone-affected communities had to await the state’s order before they could begin their volunteer work. The victims were instructed to present their identity cards in order to be eligible to receive food and household supplies. There is a fine line between bad governance and the lack of post-disaster relief experience. Unfortunately, the Myanmar Government was unable to define this line.[61]

Displaced Persons and Forced Returns

According to Burmese Prime Minister Thein Sein, two days after the cyclone, 1,064,623 displaced people were “rescued” and sent to temporary shelters at 12 frontline camps, 15 transit camps and 5 base camps. The official camps quickly became photo-opportunity locations for senior SPDC who visited communities housed in rows of donated tents. The actual number of temporary camps was far more numerous than official statements suggested. Large numbers of displaced people also sought shelter in monasteries, churches and mosques, and in other hard-walled buildings that survived the storm.

In late May and early June, local authorities started to force villagers out of schools, monasteries and small camps and coerced them into returning to their original villages, even if they were not inhabitable.[62] This placed the returnees at risk and violated international standards. The UN Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement provide that displaced persons have the right to be protected against forcible return to any place “where their life, safety, liberty and/or health would be at risk.”[63] The authorities have the primary duty and responsibility to “establish conditions, as well as provide the means, which allow internally displaced persons to return voluntarily, in safety and with dignity, to their homes or places of habitual residence, or to resettle voluntarily in another part of the country”.[64] In addition, “[s]pecial efforts should be made to ensure the full participation of internally displaced persons in the planning and management of their return or resettlement and reintegration.”[65]

The military authorities began forcible returns in the delta in May.[66] According to the World Food Program, displaced persons were being sent out of relocation camps or temporary shelters back to their home villages, where conditions remained poor: “WFP staff are finding that people who have been returned to villages with inadequate shelter and lack of water and food supplies are moving on within the delta to larger villages where they have more chance of receiving assistance. Many are also traumatized by the decimated population of their original communities and prefer to re-settle elsewhere.”[67] SPDC leaders denied that displaced persons were being forced to return to their homes.[68]

On return to their devastated villages, many survivors turned to their own communities to help them: Christians sought shelter and relief supplies through church groups, Muslims through mosques, and Buddhists through monasteries. In many cases, there were reports of cooperation between local religious leaders in the absence of government direction of the aid effort. Many of the shattered villages from Cyclone Nargis were located in outlying areas of farming and fishing communities trying to survive without harassment on the fringes of Burmese army control.

* * *

The obstructions to humanitarian aid in the immediate weeks after the cyclone are best explained by the SPDC’s general lack of concern for the population at large, incompetence and inexperience at disaster relief, and an overriding obsession with security and control ahead of the referendum on the new constitution, scheduled for May 10, just eight days after the cyclone hit.

Fortunately, the feared “second wave of mortality” did not occur despite the delays in getting food, medical supplies and assistance to survivors. Some aid workers remarked that the “coping strategies” of the population accounted for their resilience, underscoring the experience of many communities with desperate living conditions even before the cyclone. According to MSF aid worker Philip Humphris, writing several months after the cyclone:

The inefficiencies of international aid evident in the Nargis response do not excuse the government of Myanmar of its responsibility to respond to the relief needs of its people. In the areas of the Delta where MSF teams were active, this response was slow compared to the scale of the disaster. Official constraints placed on international humanitarian actors in the country were still present three weeks after the disaster. This meant inadequate access during this time, and only unofficial needs assessments and limited relief were possible. One month after Nargis hit, MSF teams were still identifying some badly affected populations surviving on rainwater and immature and spoiled rice crops, with cases of dead relatives floating in the surrounding water and suspended in the trees where the cyclone had deposited them.[69]

Louise Arbour, the outgoing UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, concluded in one of her final speeches as commissioner that: “In the case of Myanmar, the obstruction to the deployment of such assistance illustrates the invidious effects of long-standing international tolerance for human rights violations that made such obstruction possible.”[70]

II. Breaking the Deadlock: ASEAN's Intervention and the Opening of Humanitarian Space

Responsibility to Protect

The SPDC’s obstruction of the international humanitarian response to the devastation and human suffering caused by Cyclone Nargis generated global outrage. Leaders from around the world criticized the blocking of relief and demanded that humanitarian agencies have greater access to the affected population, contrasting Burma’s restrictions with the openness shown by Asian countries affected by the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami. High-level envoys soon arrived in Rangoon to convince the junta to open up access.

Some foreign government leaders broached the idea of invoking the international doctrine of Responsibility to Protect, which recognizes that in order to help protect populations facing genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity, the international community has a responsibility “to take collective action, in a timely and decisive manner, through the Security Council … should peaceful means be inadequate and national authorities manifestly fail to protect their populations.”[71] French Foreign Minister Bernard Kouchner said on May 7 that the UN Security Council should authorize transport of emergency aid without the consent of the SPDC.[72] In an article in Le Monde, Kouchner argued:

The Burmese situation is at the heart of an unusual conflict between political and humanitarian considerations. Access to the victims of armed conflicts theoretically used to be more difficult because of the belligerents’ mistrust of humanitarian workers’ first-hand accounts of the violence of the clashes and acts of brutality against civilians. On the other hand, the distribution of aid in the event of catastrophes used to be facilitated by the relative depoliticization of the situation. The affected countries called for it. Yet in Rangoon, the cyclone isn’t opening up the borders any more than the massacres did. The offers of aid arouse suspicion and rejection, as if letting in the humanitarian workers raised the fear of them seeing the unspeakable.[73]

Some commentators contend that such statements actually fuelled the SPDC’s intransigence, playing into long-held fears of foreign military intervention to topple the government.[74] Others argued that applying the Responsibility to Protect doctrine to the post-cyclone situation in Burma was a misapplication of the original idea, articulated in a 2005 World Summit, and would have dire consequences for the doctrine and for future diplomatic and aid engagement with Burma.[75] Gareth Evans, then president of the International Crisis Group, noted that the doctrine of responsibility to protect could not be stretched to cover human security or natural disasters more generally, but was limited to “genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity.” At the same time, he noted that the commission that initiated the responsibility to protect proposal had stated that a crime against humanity could include: “overwhelming natural or environmental catastrophes, where the state concerned is either unwilling or unable to cope, or call for assistance, and significant loss of life is occurring or threatened.”[76]

The call for invoking the Responsibility to Protect was not taken up by the UN Security Council.[77] But the public debate, fuelled by intense media interest, helped open negotiating space for those seeking to persuade the SPDC to cooperate with the international community and allow greater assistance to the cyclone-devastated areas.

Tripartite Core Group

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) finally managed to break through the SPDC’s intransigence and broker a deal that improved humanitarian access for international humanitarian groups. ASEAN Secretary-General Surin Pitsuwan dispatched an Emergency Rapid Assessment Team (ASEAN-ERAT) to Rangoon on May 9 to start gathering data on organizing relief supplies. The ERAT reported to him that:

The main overarching concern for the international community including other ASEAN Member States and international organizations is currently the issue of access to the affected areas for the provision of assistance. International aid workers with known expertise and experience in managing and providing assistance in major catastrophes need to be working closely with their government counterparts in the capital and more importantly in the field where the need for assistance and coordination is critical. There is the possibility of a potential second wave of deaths and morbidity due to diseases and nutritional deficiency which could be avoided through a more coordinated effort between the international community and the Government of Myanmar.[78]

In late May, UN Secretary-General Ban visited Burma, meeting with senior SPDC officials and chairing a donor pledging conference attended by dozens of diplomats, aid donors, and heads of humanitarian agencies. Ban’s message at the pledging conference was “people, not politics” and expanded access and aid to the affected areas. He publicly stated:

Expert and experienced international relief workers, in addition to the medical teams from neighboring countries, must have unhindered access to the areas hardest hit by the disaster. Extra transport assets, including helicopters and boats, are urgently required. Whatever is needed to build an effective aid and logistics pipeline must be quickly put in place and be well-coordinated, both with Myanmar authorities and international aid agencies.[79]

The call from the conference to the SPDC was two-fold: to permit full and unfettered access to the cyclone-affected areas for relief workers and to cooperate in a credible needs assessment for continued emergency relief and reconstruction.

The pledging conference agreed to form an ASEAN Humanitarian Taskforce for the Victims of Cyclone Nargis that would take the lead in coordinating international efforts. It was a compromise which many participants deemed necessary to persuade the SPDC to open up the humanitarian space that it had largely denied for the first three weeks of the emergency. By the end of May, the SPDC agreed to form a Tripartite Core Group (TCG), composed of the Burmese government, the United Nations and the ASEAN to coordinate the relief operation. The arrangement was engineered by ASEAN Secretary-General Surin and supported by the UN. The TCG would be led jointly by deputy foreign minister U Kyaw Thu, a well-respected Burmese bureaucrat, the Singaporean ambassador to Burma, Robert Chua, and the UNDP resident representative, Dan Baker. Starting on June 8, 300 members of 32 assessment teams (comprised of UN, ASEAN, SPDC and seconded World Bank staff) spent 10 days assessing needs in the affected areas.

The Post Nargis Joint Assessment (PONJA) preliminary report was released in Rangoon in late June and led the UN to launch a revised flash appeal for emergency funds of US$303.6 million. The PONJA final report followed on July 21 and concluded that total damage of the cyclone was more than US$4 billion and that US$1 billion was needed for recovery.[80] More than two months after the cyclone, more than half the households in the affected areas still had urgent food, shelter, sanitation and health needs.[81] In terms of scale of destruction and deaths, the devastation of Cyclone Nargis was almost equal to the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami.

While such comprehensive assessments are standard practice following a devastating natural disaster, the PONJA assessment was unprecedented in Burma in terms of the access it granted to ASEAN, United Nations and other international assessors to the affected areas. The fact that it was a joint assessment conducted with the participation of SPDC officials also compelled the SPDC to confront the scale of the disaster and the humanitarian suffering caused, thereby forcing at least some SPDC officials into a dialogue on how the pressing humanitarian needs could be met.

Nevertheless, despite the intense diplomatic pressure and the ASEAN-led effort to engage the SPDC into agreeing to a comprehensive humanitarian response, the SPDC continued to impose restrictions limiting and controlling the humanitarian response in various ways. Prime Minister Thein Sein surprised many at the pledging conference by abruptly declaring the emergency relief phase was over and that the rehabilitation phase was starting. He told the conference:

[W]e would warmly welcome any assistance and aid which are provided with genuine goodwill from any country or organization, provided that there are no strings attached nor politicization involved.… In line with the policy of the Government that achievements can be made with the close collaboration of the Government, people and members of the armed forces, under the leadership of the Government.[82]

Despite the denial of access to the affected areas and forcible evictions of displaced persons during the first weeks after the cyclone, a number of commentators now believe that cooperation between the Burmese government and the international community in cyclone relief was generally successful. The TCG opened the “space for creative engagement with the authorities,” effectively opening the way for donors to expand activities in the Irrawaddy Delta.[83]

But nearly a month after the cyclone, the UN estimated that about one-third of survivors still had received no assistance. While visas for foreign aid workers were slowly being granted, the United Nations continued to report incidents of Western staff of INGOs being turned back at government checkpoints, and authorizations approved by one group of government authorities being withdrawn by other authorities. By June 9, only 86 UN staff had been granted approval to visit the delta, and only 179 visas had been issued.[84] Helicopters, boats and trucks began ferrying supplies to those in need, and travel restrictions were gradually eased. Rangoon became both a hub for supplies and personnel and a bottleneck for those waiting for approval to travel to affected areas. Tony Banbury, the regional WFP chief, visited the Irrawaddy Delta one month after the cyclone and wrote:

Legions of aid workers await permission to enter Myanmar and join the nascent relief effort now underway. Some have made it as far as Yangon… but few have been allowed to travel to the hard-hit delta, and fewer still to stay there and work night and day… the harsh, unbending reality [is] that hundreds of thousands, maybe millions, of human beings are in desperate need of assistance for their survival and well-being, and that they are not getting it.[85]

In early June, the long-awaited helicopters ordered by the World Food Program began flying into the delta.[86] Paul Risley, the WFP spokesman in Bangkok, said the helicopters proved valuable in reaching isolated villages that had received little if any aid. “Today was the first day where you really saw a multiplier effect. These are areas that clearly have not received regular supplies of food or other relief assistance.”[87] However, much of the aid being transported to the delta was through truck transport and boats along the waterways and coastal areas.

In early June, the SPDC released a new set of guidelines for foreign humanitarian aid workers, which updated guidelines that had been imposed in March 2006.[88] The rules were restrictive and inimical to the spirit of the pledging conference agreements, and differences between the English version and the interpretation of the Burmese version by local authorities added another layer of ambiguity and uncertainty. As with many official documents in Burma, the rules denied foreign aid workers the reassurances and certainty they needed to effectively carry out their work and provided discretion to the authorities to take actions to restrict activities they viewed as adverse to government interests. In reference to the new restrictions, an OCHA situation report stated:

IASC [Inter-Agency Standing Committee] members have expressed concern that, if followed, [the new rules] will negatively affect ongoing emergency relief operations. Organizations are to seek approval for their activities from the relevant line Ministry and the Tripartite Core Group (TCG). Visas and importation of relief items are to be authorized by line Ministries and the TCG. Detailed listings of relief supplies and distribution plans are to be shared with line Ministries and Township Coordination Committees. Supplies are to be ‘temporarily kept in Yangon.’ Domestic travel arrangements are to be shared with line Ministries and Township Coordination Committees are to be informed of travel arrangements.[89]

The official SPDC line after the TCG breakthrough was cavalier, almost to the point of being callous about the continuing challenges. In one notorious state run commentary, ongoing food shortages were dismissed because of survivors’ ostensible access to wildlife in the devastated areas: “In the early monsoon, large edible frogs are abundant. The people of the Ayeyawady Division can survive with self-reliant efforts even if they are not given chocolate bars from [the] international community.”[90]

III. Local Heroes: The Spontaneous Response of Burmese Society

When the SPDC blocked international humanitarian organizations from responding to the crisis while failing to mount a major relief effort itself, thousands of ordinary Burmese decided to respond on their own initiative to the needs of their fellow citizens. Spontaneously, Burmese from all backgrounds—monks, business people, local activists, doctors, and ordinary farmers and laborers—began collecting food, clothes and housing materials from their communities and driving to the delta where they haphazardly delivered their relief goods. Ad hoc groups were organized. At the same time, international humanitarian groups, initially largely prevented from mobilizing their international staff in the affected region, quietly sent their local staff into the delta to establish a presence and begin delivering humanitarian relief, which laid the groundwork for the larger-scale humanitarian effort that developed.

Individual Burmese citizens, and existing and newly created local civil society groups, were played critical roles in bringing aid to those most in need. There is little question that many of the “first responders” to the cyclone helped save and sustain the victims of the disaster. Buddhist monks, whom the authorities had repressed and intimidated since their leading role in the 2007 anti-government demonstrations, often took the lead, as did Christian church groups and other community organizations.

Long seen as oppressed into silence by decades of military rule, Burmese society has become more assertive in the past few years protesting declining socio-economic conditions wrought by years of military misrule. The SPDC initially stood idly by during the outpouring of local support to help the cyclone’s victims, but soon reintroduced control through checkpoints and close monitoring of aid. Later on, the SPDC targeted activists for harassment, arbitrary arrest, and—in a number of cases—lengthy prison sentences for their organizing activities and expressing views that the SPDC viewed as threatening its control. The SPDC also sought to steer international donor assistance into the network of social organizations that the government tightly controls and uses for both political and social objectives.

Civil Society in Burma

According to a 2005 study conducted in Burma, there are approximately 64 nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and 455 countrywide community-based associations (CBOs), which can be termed non-profit civil society organizations.[91] Many of these organizations are local-level religious groups and health-focused service providers that operate in towns and rural areas throughout Burma and face varying levels of coercion from national and local authorities. NGOs in Burma outside of the control of the authorities suffer harassment by government officials who wish to either subsume their activities into the work of state agencies, restrict successful initiatives that cast an unbecoming light on civil service failures, or eliminate the possibility of wider social mobilization by a NGO that could constitute a threat as perceived by those in government.

Nevertheless, many groups are able to operate in the space outside of government control, or learn to live within it and pursue development projects that have the tacit support or at least acquiescence of local authorities.[92]Burma’s rich social and cultural life provides a basis for a civil society that pursues social activities that do not have immediate political dimensions.[93]

Spontaneous Civil Society Responses to Cyclone Nargis

In the aftermath of the cyclone, thousands of people from throughout Burma spontaneously became humanitarian aid workers. Myo Nyunt (not his real name), now director of a major local relief organization still active in the Delta, explained to Human Rights Watch how he and his friends changed their existing education-focused organization into a humanitarian relief society:

When Cyclone Nargis struck, there was no authority visible even in Rangoon, because there was so much damage, and it was clear that the authorities couldn’t meet the needs of the people so they decided to stay away. This was alarming to the public—suddenly we found no soldiers and no local authorities on the street. People had to rely solely on themselves, but we had never found ourselves in such a situation.

Many people rushed to the cyclone-affected areas to provide whatever they could. At that time, people were coming even from Mandalay and Chin State, far away. They would collect money and materials from their community and then bring it down in trucks.

We had no experience of working in a group before—the authorities were always too suspicious. Before the cyclone, we offered educational programs and trainings, but we were not allowed to do humanitarian work. Cyclone Nargis created the space for us to engage in humanitarian work, not the government. The 2007 monk’s uprising also helped—the uprising and Nargis gave big shocks to the government.[94]