A Violent Education

Corporal Punishment of Children in US Public Schools

I. Summary and Key Recommendations

On August 18, 2003, 10-year-old Tim L. started the fifth grade at his public elementary school in rural east Texas. On the fourth day of school, Tim refused to run in gym class because he did not have his asthma medication. When the gym coach confronted him, Tim said, "coach sucks." The coach then took a wooden paddle and beat Tim severely on the buttocks. Faye L., Tim's mother, reported, "There was blood in his underpants…. I had to pull the underwear off his behind from the dried blood."[1]

Though Tim had always been an enthusiastic student, he begged his mother not to make him get on the school bus the next day. Three days later, with his bruises still fresh, Tim was hit again, this time by a teacher, for playing with a pen during band class. His genitals were bruised and swollen. With her son physically injured and terrified of school, Faye decided she could not risk sending him back. She began to teach him herself, at home.

Faye wanted school authorities to hold the teachers accountable. They reminded her, however, that corporal punishment is legal in their district, and refused to take disciplinary action against the two teachers who had hit her son. When she tried to file assault charges, the police dissuaded her, saying she had to "follow school procedure." Next, she attempted to pursue private litigation, but her claims were dismissed in court because the law provides immunity for teachers who paddle.

Faye was left feeling that she had no way to seek justice for the injuries her son had already sustained, and no way to protect him from future harm. Though Tim asked to go back to school, Faye felt she could not offer him a guarantee of safety in their public school district. "The law is supposed to be there to protect you. How do you explain this to your son, after this? 'Well, I'm sorry, honey.' That's all you can say."[2]

* * *

Tim's mother's tenacity and commitment to protecting her son's rights make this story extraordinary. Yet in other ways, Tim's story is far from unique. In school districts in many states, students of all ages are routinely subjected to corporal punishment.[3] Though some states have outlawed the practice, it is permitted by some federal and state laws. Hundreds of school districts allow students to be beaten, and state legislatures provide specific legal protection for educators who injure students when using corporal punishment. Studies show that beatings can damage the trust between educator and student, corrode the educational environment, and leave the student unable to learn effectively, making it more likely he or she will leave school. African-American students are punished at disproportionately high rates, creating a hostile environment in which minority students struggle to succeed.

The United States is out of step with international practice and jurisprudence on the use of corporal punishment in schools. Today 106 countries outlaw the practice, including the United Kingdom and other European countries, following rulings on corporal punishment by the European Court of Human Rights. Experts charged with issuing definitive interpretations of international human rights treaties also consistently have concluded that corporal punishment by school officials and teachers violates governmental obligations to protect children from physical violence and cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment. The disproportionate use of corporal punishment against African-American students in particular violates the right to non-discrimination in accessing education.

Corporal Punishment in US Public Schools

As students across the United States return to school each year, they, like their parents, are hoping for academic success. Policymakers and educators have the important responsibility of creating an educational environment based on respect, including an effective disciplinary system. Yet for many students, "discipline" means extensive use of violence.

According to the Office for Civil Rights at the US Department of Education, 223,190 students nationwide received corporal punishment at least once in the 2006-2007 school year, including 49,197 students in Texas alone, the largest number of any state. In Mississippi, 7.5 percent of public school students were paddled during this period, the highest percentage in the nation. The actual numbers almost surely are higher: Human Rights Watch interviewees reported that corporal punishment is often administered in a chaotic environment in which many instances of the practice are not recorded. One administrator reported that 37 students in a single day were sent to his office for corporal punishment. A high school student in another district estimated that as many as 60 students a day are paddled at her school.

Today 21 US states permit corporal punishment to be used in schools. Corporal punishment usually takes the form of paddling (also called "swats," "pops," or "licks"). A teacher or administrator swings a hard wooden paddle that is typically a foot-and-a-half long against the child's buttocks, anywhere between three and 10 times. Paddling can happen in the office or elsewhere, as noted by one Mississippi teacher: "The principal would do it in the hallway, in the classroom, in the band room. He would patrol the hallways with a paddle."[4] Students can be physically punished for a wide range of misbehavior, including minor infractions such as chewing gum, being late, sleeping in class, talking back to a teacher, violating the dress code, or going to the bathroom without permission.

Even students who are not punished find themselves in a hostile, violent environment designed to instill fear. One student told us that "licks would be so loud and hard you could hear it through the walls." A teacher reported that a principal turned on the loud speaker while paddling a student: "It was on the intercom in every class in the school…. He was trying to send a message … [l]ike, 'you could be next.'"

A Violent and Degrading School Environment

Minor bruising and stinging are the most common results of corporal punishment. Some children are more seriously injured. Some parents we interviewed sought medical care for their children who, like Tim L., sustained bleeding and deep bruising to the buttocks. Other children sustained blows to other parts of their bodies, including their hands or arms when they reached back to protect themselves. Corporal punishment can also impact students' mental health, especially for some special education students.

For hundreds of thousands of school children in the US, violence inflicted by those in authority is a regular part of their experience at school. All corporal punishment, whether or not it causes significant physical injury, represents a violation of each student's rights to physical integrity and human dignity. It is degrading and humiliating, damaging the student's self-esteem and making him or her feel helpless.

A number of teachers told us that as students are beaten, or see those around them beaten, the trust between administrators, teachers, and students is often destroyed. Over time, students may become less engaged in school and less interested in exploring and discovering new academic concepts. Corporal punishment may result in the student failing to thrive academically and may contribute to school drop out.

Though some educators believe that corporal punishment is an effective way to deter students from misbehavior, including students who may engage in physically disruptive and harmful behaviors like fighting, corporal punishment teaches students that violence is legitimate. Research suggests that children who are physically punished are more inclined to engage in aggressive conduct toward their siblings, parents, teachers, and schoolmates.

As a consequence of the helplessness and humiliation felt by students who experience corporal punishment, some students become angry: students told Human Rights Watch that it only makes them want to lash out against teachers or other students. Others become depressed or withdrawn; still others become immune to the constant violence, accepting it as a part of their daily lives.

Some parents are concerned that the use of corporal punishment in schools could also legitimize domestic violence in the home. One mother observed: "What are we teaching our young women when a school principal can swat … on the behind? We're saying that it's okay for a man to beat a woman … [that's] something we don't want in our families."

Discrimination in the Classroom

Corporal punishment in the US disproportionately affects African-American students, and in some areas, Native American students. In the 2006-2007 school year, African-American students made up 17.1 percent of the nationwide student population, but 35.6 percent of those paddled. In the same year, in the 13 states with the highest rates of paddling, 1.4 times as many African-American students were paddled as might be expected given their percentage of the student population. Although girls of all races were paddled less than boys, African-American girls were nonetheless physically punished at more than twice the rate of their white counterparts in those 13 states during this period. These disparities violate students' right to non-discrimination in access to education, making it harder for these students to succeed and undermining the social fabric of schools.

Special education students-students with mental or physical disabilities-also receive corporal punishment at disproportionate rates. For instance, in Texas, the number of special education students who were beaten in the 2006-2007 school year amounted to 18.4 percent of the total number of students who received corporal punishment statewide. However, special education students made up only 10.7 percent of the Texas student population, meaning almost twice as many were beaten as might be expected. Corporal punishment damages these students' education as much as other students, and it may also adversely affect some students' underlying physical or psychological conditions.

Lack of Recourse

Students, parents, and teachers encounter obstacles when trying to limit corporal punishment. For instance, teachers who work in schools that use corporal punishment may find themselves without alternative ways of disciplining particularly troublesome students. We interviewed teachers who wanted to send chronically misbehaving students out of the classroom, but were reluctant to do so knowing they would be beaten. While some teachers believe corporal punishment is an effective tool, other teachers concur with academic research showing that positive forms of discipline such as counseling and mediation are more effective in addressing the student's underlying issues. Yet if the school does not support these forms of discipline, individual teachers face obstacles implementing them on a classroom-by-classroom basis.

Students are sometimes asked to choose between corporal punishment and other forms of discipline such as suspensions or detentions, decisions children should not be asked to make. One elementary teacher described her pupils' decision process as follows: "I take the five licks because I'm nine and I want to go outside and play."[5] Older students choose paddling because they want to seem tough or because their parents are less likely to find out about the underlying infraction. While it is a recognized principle of human rights that children should have a voice in making the policies to which they are subjected (and that participation is increasingly important as they get older), giving children of any age a stark choice between being beaten and other forms of discipline is not appropriate. Rather, it is a form of coercion that exploits vulnerable young people with underdeveloped decision-making capabilities, asking them to trade away their right to be free from beatings by school personnel.

Parents in some school districts are given methods of "opting out" of the use of corporal punishment on their children. However, these mechanisms are inadequate: parents report that opt-out forms are ignored and that their children are beaten anyway. Parents have virtually no legal recourse when opt-out forms are ignored, or when their children are beaten severely with or without an opt-out form. Human Rights Watch investigated several cases in which parents said school districts were unwilling to provide adequate responses, police were reluctant to investigate, and courts were unable to offer redress. Some parents we interviewed, like Faye L., felt they had no recourse but to withdraw their children from school and teach them at home.

Legality and Reform

While corporal punishment is prohibited in most US juvenile detention centers and even foster care settings, it continues to be allowed in certain US public schools. Many parents and teachers hold to the belief that corporal punishment in public schools has an instructive purpose, providing the discipline "necessary" for children to learn. The fact that many people believe that corporal punishment has a genuine pedagogical function does not diminish the fact that it violates children's human rights.

International instruments, including the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, the UN Convention against Torture, and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, prohibit the use of cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment, regardless of circumstance. Corporal punishment in US public schools also violates other human rights, including the right to freedom from physical violence and the right to non-discrimination. Corporal punishment infringes on the right to education, and educational experts have concluded that the use of corporal punishment hinders learning, encourages children to drop out of school, and generally undermines the purposes of education as articulated by a broad spectrum of US educators and embodied in international law.

Standards set by the US government and many states on corporal punishment fall far below the best practices counseled by educational experts and the obligations inherent in international human rights law. Though more than half the states prohibit the use of corporal punishment in schools, federal law does not ban the practice. The US Supreme Court has refused to impose constitutional restrictions on the practice of "reasonable" corporal punishment.[6]

Some state laws criminalize the imposition of excessive corporal punishment, but the standard of "excessiveness" is hard for students to prove. While some school districts have attempted to regulate corporal punishment, for example by placing limits on the number of blows a child may receive or requiring that the paddler not beat the child in anger, these regulations have proved difficult if not impossible to enforce. And such attempts do not address the basic fact that a child's rights are violated whenever he or she is beaten by school authorities.

While some Americans might believe firmly in the adage "spare the rod, spoil the child," corporal punishment has increasingly been prohibited in many states and municipalities. In fact, 95 of the 100 largest school districts in the country have banned corporal punishment, including Houston, Dallas, Memphis, Atlanta, and MobileCounty.[7] Twenty-nine states and Washington, DC, have banned the practice,[8] as have many school districts within states that permit corporal punishment. Outside of the US, as noted above, 106 countries reject the use of corporal punishment in public schools.[9]

Teachers in districts that use corporal punishment may want the best for their students, and may genuinely believe that corporal punishment can help to educate them. Likewise, parents and even children want orderly, safe school environments in which students can learn. But corporal punishment is not the answer. The practice hurts students, it damages the cohesive school culture that they need in order to learn, it is discriminatory, and it teaches violence as an appropriate response to problems.

Poverty and lack of resources help create conditions that lead to corporal punishment in schools. Teachers may have overcrowded classrooms and lack resources such as counselors to assist with particularly disruptive students or classroom dynamics. These conditions do not facilitate effective discipline, and they may explain why teachers feel it is necessary to subject students to beatings, but they do not excuse such actions.

Better approaches to school discipline are available. Effective discipline does not require paddling of students. Nationwide, teachers and administrators increasingly have been using positive discipline methods that foster nurturing school cultures, which allow students to thrive. With appropriate funding, training, and support, teachers and administrators can implement discipline systems that respond to students' fundamental needs and do better at producing environments in which every student can maximize his or her academic potential.

Key Recommendations

- The president of the United States, the US Congress, state legislatures, and governors should take all necessary steps to ban explicitly the use of corporal punishment in schools. There should be no exceptions for "reasonable" force or corporal punishment "to maintain discipline."

- Until a complete ban on corporal punishment has been instituted, federal and state legislatures, governors, and boards of education should establish an immediate moratorium on corporal punishment for special education students, in light of their particular vulnerability and additional potential for serious physical or psychological injury.

- Until a complete ban is adopted, state legislatures, governors, and boards of education should require school districts to respect parents' wishes not to have their children beaten by school officials, at a minimum by establishing an "opt-in" scheme requiring parents affirmatively to agree before their child could be subjected to this practice.

- State legislatures, police, district attorneys, state courts, and local school boards should remove obstacles that prevent victims of corporal punishment (and their parents) from pursuing redress. Lawmakers should repeal legislation that grants educators who use corporal punishment immunity from civil or criminal laws. Law enforcement officials and courts should treat corporal punishment complaints as any other assault complaint.

- State boards of education, local school boards, superintendents, principals, and teachers should prohibit the use of corporal punishment in all schools and classes under their control, and provide educators with extensive training and support for effective, non-abusive discipline techniques.

- State boards of education and local school boards should implement statistical review systems that track every instance of corporal punishment, and take measures to ensure that students of color are not punished at disproportionate rates.

- Federal and state governments, local school boards, superintendents, principals, and teachers should conduct comprehensive and sustained awareness-raising campaigns among parents and children on the right not to be disciplined physically, including appropriate programs according to the age of the child.

II. Methodology

For this report, researchers from Human Rights Watch and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) conducted 181 in-person and telephone interviews with experts and individuals directly affected by corporal punishment, including parents, students, teachers, and administrators. Seventy-one interviewees were current students, recent high school graduates, or young people who left school without obtaining a diploma. Of the current and former students we interviewed, 34 were between the ages of 9 and 17, and 37 were between 18 and 26. All of these young people were interviewed in person in Mississippi or Texas, where corporal punishment is widely used.

We spoke with 40 parents of students in school districts that use or used corporal punishment, 24 teachers who have relevant experience, 12 officials (including current and former school board members and current or former superintendents or assistant superintendents), and three school administrators. In addition, we spoke with lawyers, advocates, and educational experts to obtain information on all sides of the issue. Finally, we contacted 40 school districts with high rates of paddling in Mississippi and Texas by email, fax, and telephone, and received nine responses to our queries.

We chose to focus on Mississippi and Texas after examining data from the US Department of Education's Office for Civil Rights (OCR), which measure prevalence of corporal punishment (and other school discipline and educational tracking data) by school district, by race, and by gender. As discussed in this report, the OCR data likely undercount the number of incidents of corporal punishment that take place in a year, because some instances of school corporal punishment are not recorded by schools and thus not included in these data, and because the data are recorded per student per year, and therefore do not record occurrences where a student is hit multiple times in one year. Nonetheless, the OCR data provide the most reliable numbers presently available on the use of corporal punishment in US public schools. According to these data, Mississippi has the largest percentage of students who receive corporal punishment each year and Texas has the largest absolute number of students subjected to corporal punishment. We also decided to focus on Mississippi and Texas after discussions with advocates against corporal punishment and other experts in educational policy in each state.

Within each of the target states, we focused on particular school districts that had high rates of corporal punishment. First, we looked at the OCR data to locate districts with high rates of corporal punishment (both absolute and as a percentage of the student population); and second, we looked at districts where African-American boys and girls were punished at disproportionate rates. We measured disproportionality by comparing the rate at which a racial or gender group appeared among students who are physically punished to that group's proportion of the student population, on a district-by-district basis. We also traveled to districts with high rates of corporal punishment and interviewed teachers, administrators, or school board members in those districts.

We conducted in-person research in Mississippi in December 2007 and in Texas in February 2008. We conducted additional interviews with individuals in locations throughout the United States by telephone between September 2007 and May 2008. All students were interviewed in person; some adults were interviewed by telephone. Interviews were conducted in one-on-one settings in almost all circumstances, although some children, particularly younger children, were interviewed in the presence of their parents. We conducted several group discussions with students for background information but comments from these discussions were not used directly in the report.

Within the targeted school districts, students, parents, and teachers were referred to us by one another or through assistance from non-profit organizations or community members. Occasionally, current and former students were approached on college campuses or at shopping malls in the targeted districts. All interviews were conducted in English.

Before interviewing any subject, we obtained written or oral consent to use the information obtained in the interview, and we determined whether the interviewee wished to remain anonymous. We obtained written consent from all in-person interview subjects, oral consent from those interviewed by telephone, and parental consent to speak to minors aged 16 or younger. Participants did not receive any material compensation in return for speaking with us. All participants were informed of the purpose of the interview, its voluntary nature, and the ways in which the data would be collected and used. Care was taken not to retraumatize affected children.

All children interviewed are identified in this report with pseudonyms to safeguard their privacy and ensure there is no retaliation against them. Neither the first names nor last initials we use in such cases correlate in any way with the child's actual name. In some cases certain other identifying information such as school, town, or grade level also has been withheld for the same reasons. In addition, all parents, teachers, administrators, school board members or other adults who requested confidentiality are identified with pseudonyms. Where interviewees gave consent to use their real names, we have so indicated in the relevant citations.

III. Corporal Punishment in US Public Schools

The Mechanics of Corporal Punishment

Corporal punishment in US public schools[10] usually takes the form of a student hit on the buttocks and upper thighs with a wooden paddle. David F., an eighth grader in Texas, was beaten in seventh grade against his mother's expressed wishes. It happened when David and another student were sent by their teacher to the principal's office for shooting rubber bands at each other. Though school policy required an adult witness in addition to the paddler, David said:

[The Principal] did it on his own. When I went in we didn't talk. He just yelled, "What the heck were you doing that for?" and then he said "I get two swats." So I had to bend over and put my arms on the hands of the chair … it probably hurt for at least another school period.[11]

The mechanics of corporal punishment in public schools help to illustrate why it is a poor choice for disciplining children. The instruments used and the position of the child during the beatings are designed to cause pain and humiliation to the child. This, combined with the fact that blows are administered by mostly male school officials who are supposed to set an example, lead to an atmosphere of humiliation, violence, and degradation. This atmosphere, in some cases tinged with sexual undertones-as when teenage girls are paddled by men-is not conducive to creating a learning environment characterized by safety and mutual respect.

The Paddles and the Position of the Child

As in David F.'s case, described above, students are typically hit on their buttocks with a wooden paddle, approximately 15 inches long, between two and four inches wide, and one-half inch thick, with a six-inch handle at one end. The size of paddles can vary. For instance, one teacher in a Mississippi high school stated that his "principal uses a paddle with a flat head and a thin neck and handle. It's about four feet long and it's made of wood."[12] The SouthDeltaSchool District, a different Mississippi district, specifies dimensions in its official policy: paddles must be 14-15 inches long, two inches wide, and 1/4-3/8 inches thick.[13]

Picture of standard paddle. © 2008 Alice Farmer/Human Rights Watch.

Students describe the paddle as "a big ole long wooden thing with a handle,"[14] and say "the paddle looks like an oar, but smaller."[15] One student noted, "They use a short one for girls and a long one for the boys."[16] One former teacher in Texas told Human Rights Watch that he found shaved down baseball bats that were being used as paddles, similar to those depicted in the following photograph.[17]

Paddles made from shaved down baseball bats; keys indicate size. © 2008 Alice Farmer/ Human Rights Watch.

As analyzed later in this report, international human rights standards state that the use of force against students is only permissible as a restraint in exceptional circumstances, and even then only to a minimal degree.[18] Any force with intent to punish is impermissible,[19] meaning that the use of corporal punishment in public schools in the United States violates international human rights law.

In a vain attempt to limit the suffering caused to children by paddling, some school district policies specify that the type of paddle used must not injure the child. For instance, the RankinCountySchool District in Mississippi specifies, "Any instrument used to administer corporal punishment shall be such as not to cause either temporary or permanent physical injury."[20] Likewise, the MeridianPublicSchool District in Mississippi specifies that the administrator "should use an instrument approved by the principal which will produce no physical injury to the child."[21] A former administrator in Meridian commented on the logical inconsistency of his district's policy: "that's a catch-22. Essentially … any striking of a child that causes pain would be an injury."[22]

Sometimes the paddle is modified to improve the paddler's swing or to inflict greater pain. The paddle might have holes in it,[23] allowing it to move faster and therefore hurt more. One student noted, "It has holes in it, so the air can just woosh through."[24] Part or all of the paddle can be covered with duct tape to prevent the wood from splitting or to improve the paddler's grip.[25] A middle school boy in Mississippi reported that this contributes to the pain of the impact: "They duct tape all around the paddle and it makes it have a grip and that's why it hurts."[26]

Making Paddles in School

Paddles are not commonly available from school supply companies for purchase,[27] and educators may keep their paddles for a number of years.[28] One Mississippi superintendent noted, "You're not going to find them in school supply stores, they don't want to be sued. They're mostly made in woodshop."[29] We received multiple reports of students making paddles as a part of their woodworking ("shop") class. One high school teacher reported, "the kids would make them in shop class and have all their friends sign them."[30] A former principal noted, "I made my paddles myself, in woodshop. There were no specifications that I knew of for dimensions, wood, etc."[31] Another teacher noted that a student gave a teacher a paddle: "One of her students had a woodshop in his family and he gave it to her as a gift."[32] The fact that students might make paddles themselves underscores the extent to which corporal punishment has become part of school culture.

Sometimes teachers give their paddles nicknames such as "Dr. Pepper."[33] A student told us that "one man had a big, big paddle with a print on it that said, 'Mr. Whoopin.'"[34] A former teacher in Mississippi reported that one of her colleagues "had Big Bob and Little Bob,"[35] while another former teacher noted that his colleagues referred to paddles as "their 'boards of education.'"[36]

When a student is paddled, he or she is typically told to stand with his or her hands on a desk or a chair, so that the student is bent over, exposing the buttocks.[37] One former student in Texas described being hit in ninth grade: "This one time, like the other times, I had to stand up, and put my hands on the chair … and then, 'pop, pop.'"[38] These stances are submissive, placing the student in a position with no opportunity for self defense, even though they are being subjected to violent blows. In addition, the experience of being hit on the buttocks, an inherently private part of the body, can be particularly humiliating.

Occasionally, students might be paddled in other positions. For instance, students might be paddled against the wall when a principal is patrolling the hallways.[39] One boy who was paddled in the second grade for laughing when his friend threw something at a teacher, said, "[The principal] took me into the office and gave me three licks…. He made me hold onto the wall and he paddled me. It hurt for about two hours, it felt like fire under my butt."[40]

Some students are paddled in even more submissive positions. One sixth-grade student who was paddled in gym class was forced to line up with other students and bend over with her hands on her knees.[41] An elementary school student reported seeing two peers paddled: "My teacher left the door wide open … I could see what was happening. [The teacher] had her legs wide open and then she closed them and put their head in between her legs. The kids had to get on their knees on the floor and she holds you down."[42]

Students are required to remain in position throughout the administration of the beating; this condition is hard to meet as moving is a natural defense to physical violence. A Mississippi boy reported that "some teachers ask for hands in pockets-so you can't move."[43] A teacher at a Mississippi high school noted that it is difficult for children to stay still when being beaten: "I saw the principal giving licks once in the hallway. He was paddling a girl…. He would hit her and she would jump away and shout that it hurt."[44]

If students move during beatings they may receive additional blows and injuries. One eleventh-grade girl in Mississippi reported that in the course of a beating, her wrist was injured: "One time I got hit on my wrist with the paddle, and he told me, 'I told you not to be sticking your hand back there.' Well, I had my hands on the table and he was about to swing and hit me, and I reached back and he hit my arm with the paddle by mistake ... it hurt!"[45] Another Mississippi girl told us, "[The principal] reared back and paddled me once and I stood up and he said, 'No, bend over.' And I said, 'No, I can't take no more-that really hurt.'… [H]e paddled me again."[46]

Clothing as Protection against Blows

While Human Rights Watch did not receive any reports of students being asked to undress completely from the waist down prior to paddling, some students reported that they were told to hold their pants tight across the buttocks or that the paddler used one hand to tighten their pants. The fact that paddlers initiate this tightening of the fabric demonstrates the intent to cause pain or discomfort, a prohibited act under international law.[47] A Mississippi high school girl stated that the principal "tightened my pants and paddled me. He … went 'pow.' He grabs pants to make them tighter on your behind. It hurts more then."[48] A Texas student agreed: "The principal pulled my pants tight-it gives you a wedgie. By making things tight, it hurts more."[49]

Students take steps to mitigate blows, well aware of the painful punishments they may face. One middle school boy who receives regular beatings reported that "I wear two pairs of gym shorts under my pants to protect against the paddling," and that during one paddling in sixth grade, all of his clothing except for the second pair of gym shorts were removed.[50]

Number of Blows

Some school districts' corporal punishment policies limit the number of blows a student can receive. For example, the MarshallIndependentSchool District in Texas limits corporal punishment to two swats.[51] Students in the Grand PrairieIndependentSchool District near Dallas, Texas, cannot receive more than three licks per day.[52]DrewSchool District in Mississippi states that "[n]o more than five (5) licks will be given to elementary students and no more than seven (7) licks will be given to students in grade 7-12."[53] The SouthDeltaSchool District in Mississippi specifies that "[n]o student shall receive more than a maximum of five (5) licks of the paddle and only to the fleshy parts of the buttocks."[54]

In other districts, we received reports of students being subjected to large numbers of consecutive blows, and/or accelerating numbers of blows. A former high school teacher in the Mississippi Delta noted that students might accumulate a number of licks: "Say they had 30 licks, they could choose 10 today, 10 more the next day."[55] Some students reported accelerating punishments. One Mississippi high school girl said, "If it's your first time, then you get like, three licks. And then if you continue to go, it'd increase to like, three, five, seven, ten."[56] Another girl noted, "He got to give you from three to nine licks. And most time for curses, he's got to give you three licks for every letter in the curse word you say…. You got to be beat down."[57] Corporal punishment always carries some risk of serious harm;[58] increasing the number of blows exacerbates that risk.

Other Instruments Used

Human Rights Watch received some reports of students being struck with objects other than a paddle, including rulers and a belt. We heard multiple reports of students being hit by teachers with rulers, especially among younger children. A Mississippi middle school boy was hit in fifth grade with a set of rulers taped together: "I was talking, it was a group of students and she [the teacher] told us to come up to her desk and she popped us on our palms … this was with four rulers taped together."[59] A girl in Texas noted that "in kindergarten … they hit us with rulers on the hands … I saw it all the time in class."[60] One former teacher in rural Mississippi reported that hitting children with rulers was prevalent in her school, noting that "in my district, this happened all the way through high school."[61]

Other Physical Force Used against Students

Human Rights Watch received reports that students were subjected to other forms of physical force in addition to paddling. A Texas middle school boy, for example, reported that, after some gym students were misbehaving, his teacher made the whole class perform "'gut checks,' where we bear crawl" across the yard; the dry grass left some students bleeding on their hands and knees.[62] Because corporal punishment is defined as any punishment involving physical force "intended to cause some degree of pain or discomfort,"[63] such punishments, seemingly portrayed as part of routine physical education, amount to corporal punishment because of the intent to cause pain.

Persons Administering Corporal Punishment

Students are typically beaten by administrators (principals, vice principals, or assistant principals)[64] and in some cases, by coaches.[65] Students are usually referred to the principal's office (or the discipline office) by a teacher; teachers also administer corporal punishment,[66] particularly among younger students.[67] According to our interviewees, coaches beat students on their teams[68] as well as non-athlete students referred to them by teachers.[69] One recent graduate explained, "In high school, it was usually the coaches who paddled. Everyone had P[hysical] E[ducation] or was on a team, so everyone had contact with the coaches…. If a teacher had a problem, they'd send that person to the coaches."[70]

The majority of paddlers in incidents described by our interviewees were male. One Mississippi teacher and mother noted that the "swats are given by grown men; some of them [are] good swingers."[71] One former teacher reported that at her Mississippi Delta high school, the female basketball coach administered corporal punishment to the girls.[72] One teacher noted there was a policy of having a female witness whenever girls were hit,[73] though this was not common in other districts we visited.

Given these school environments, in which corporal punishment is an accepted means of punishment, and in which teachers and school administrators are perceived as community leaders entitled to respect, it is not surprising that Human Rights Watch received multiple reports of parents and guardians who cooperated with administrators by coming to school to beat their children themselves.[74] One mother in rural east Texas described one such situation:

There was an incident the last year when the principal asked me whether she could paddle my child. I said no, but said that I would come over there and use the paddle myself…. I don't remember what he did but I gave him two pops and told him to cut it out. I used her paddle in the principal's office, she was there.[75]

Parents may discipline their children on school premises to show their commitment to the child's education. One teacher and mother in Mississippi reported, "Some parents get called in and they will give their child swats in front of the administrators to show that they take discipline seriously."[76] A teacher noted that parents might also volunteer to paddle their children at home for infractions committed at school: "If I call parents about a kid with a discipline problem, 80 percent of the time the parent will say, 'Okay, I'm gonna give him a few good licks.' It's a way of showing respect to the teacher."[77] It is natural that parents want to engage in their children's education, and show their commitment to helping their children succeed. However, endorsing this sort of punishment undermines the learning environment by sending the message that violence and humiliation are appropriate and tolerated.

The Atmospherics of Corporal Punishment

The size and shape of paddles, the identity of persons administering corporal punishment, and the bodily positions of children, as discussed above, all contribute to a school atmosphere of harm and degradation. Beyond these mechanical elements, corporal punishment can set a tone of intimidation and humiliation in schools, as other students see and hear the punishment.

Intimidation and Threats

Students are constantly aware of the possibility of being beaten, a threat that discourages an open, trusting relationship between students and educators. One mother noted, "[my sons] talk about it all the time. It's always there in the school, and even in the classrooms. Some of my sons' teachers like to walk around holding their paddle."[78] Some teachers display paddles while making verbal threats. A seventh-grade boy in Mississippi reported that a teacher had a paddle: "He used to have it in the cabinet but he brought it out when kids started acting out towards the beginning of the school year. It gives us the signal that if we talk some, we going to get a whuppin.'"[79] One fifth-grade girl said her teacher leaves the paddle on her desk: "I feel [it] ain't supposed to be there because I don't like paddles, I just don't."[80]

Many students report specific threats of violence. For instance, a tenth grader reported she was told by her principal, "'Y'all go back to class before I tear you all up.'"[81] A recent graduate recalled that her cheerleading coach threatened her with a sorority paddle.[82] Some parents instructed the school not to paddle their children, but those students were nonetheless threatened: a fifth-grade boy reported that his principal "told me that 'if I could paddle you I would beat you black and blue.'"[83]

Witnesses to Paddling

In some instances, the administration of corporal punishment requires that another adult at the school witness the beating. Neither Texas nor Mississippi law requires such a witness, since both states delegate responsibility to school districts for determining the parameters of the administration of corporal punishment.[84] However, the school board associations in both states provide sample policies that individual districts may use in drafting their discipline policies and those sample policies call for a witness.

The Mississippi Association of School Boards recommends that any paddling be witnessed by at least one certified school employee at all times.[85] The Texas Association of School Boards suggests that "[c]orporal punishment shall be administered in the presence of one other District professional employee."[86] One teacher in Mississippi reported that the witness rule existed in her district in order to ensure the paddler is not hitting "in anger,"[87] but the presence of an adult witness cannot guarantee lack of anger on the part of the individual administering the blows.

Sample policies in Texas specifically dictate that corporal punishment should occur "in a designated place out of view of other students,"[88] and many school districts we visited adopted that language.[89] Sample policies in Mississippi do not give the same guidance, but some individual districts in Mississippi also require students to be paddled "not in the view"[90] of other students.[91]

Despite these attempts to preserve the privacy of students, many students we interviewed in other districts had witnessed their peers being beaten. A fifth-grade girl in rural Mississippi described witnessing a friend's paddling because "my teacher left the door wide open." She noted, "It made me mad, angry, and sad to see her get hit by a paddle."[92] Frequently, students are beaten in hallways: one middle schooler saw students paddled in the hallway through the crack of a door.[93]

Even in districts that prohibit students from witnessing paddling, students nonetheless hear their peers being beaten. An 18-year-old remembered high school paddlings: "I didn't see it but I could hear it. Licks would be so loud and hard you could hear it through the walls. You could hear the moans and yelling through the walls."[94] Allowing students to hear beatings may have been intentional, according to one former Mississippi high school teacher:

One time [the principal] was paddling this kid and put it on the loud speaker. It was on the intercom in every class in the school. You could hear him paddling this kid, talking bad to this kid. Oh yes, he did it on purpose. It lasted a minute or two. He was trying to send a message. I don't know … like, "you could be next."[95]

Some students are forced to wait for their own punishment while listening to the beatings of others, as one Mississippi middle school boy described, "You have to stand in line for like 30 minutes, waiting to get paddled while you're listening to everyone else."[96] As another middle school boy noted, "sometimes you hear five or six licks, and you're like, damn."[97] A tenth-grade girl in Texas noted that in ninth grade, "there was this separate waiting room. We'd hear it, the other kids getting hit. It sounds like dropping books on the floor. We'd all laugh, be like, 'damn, that's hurtin' today.'"[98]

Some students and teachers have seen or heard paddling so often that they are no longer outwardly affected by the experience. A former Mississippi teacher described how another teacher came into her classroom and paddled a student. The rest of the class's reaction was "normal. They got quiet and watched. For a select few I know they feared, but most of them laughed."[99] Another teacher noted, "Once you've been in it for a while, I don't know … you get immune to it happening around you."[100]

"The Devil's Bargain": Choosing to Be Beaten

In many districts, students are given a choice of corporal punishment or another punitive form of discipline. Students in both Mississippi and Texas may be asked to choose between corporal punishment and detention,[101] in-school suspension[102] or out-of-school suspension.[103] We also heard reports of elementary students being asked to choose between getting beaten and losing recess,[104] and of high school students being asked to choose between being paddled and getting worse grades.[105]

In some districts, the alternatives to corporal punishment, such as out-of-school suspension, are not desirable for students or for educators who prefer to keep their students in the classroom setting. In other cases, schools have such limited resources that alternative disciplinary measures are not an option, thereby increasing the frequency of corporal punishment. Whether or not students are mature enough to make these decisions, they should never be put in the position of bargaining away their human right not to be beaten by school officials.

Typically, interviewees reported that three to five blows are equivalent to one day of in-school or out-of-school suspension.[106] The "exchange rate" of physical strikes to alternative punishment can vary, however. At a high school in Mississippi, students were given the choice between five blows or five days away from school.[107] At another Mississippi high school, students were asked to choose between five blows or 15 minutes in lunch detention.[108]

Our interviews indicate that students often choose beatings over other forms of punishment. This is not surprising since the costs of refusing to be beaten and taking a suspension instead can be high. If a student is suspended, he or she is forced to miss class and teachers are not obliged to provide make-up work, meaning that students may fail. An 18-year-old boy in Mississippi noted that at his high school, "my friends who refused to be paddled got ISS [in-school suspension] or a zero day-that meant your parents had to bring you back [to school]."[109]

In fact, proponents of corporal punishment often justify their views by citing the undesirability of suspension, and pointing out that corporal punishment means the student returns to class faster. For example, one superintendent asked if a student is home alone, suspended from school, "is that really what's best educationally?"[110] This argument ignores the students' basic rights, and the fact that other options are available. Ultimately, schools should not be forcing students to make this difficult choice, and should instead be using effective positive discipline measures.[111]

Students may be induced to use corporal punishment as a bargaining chip. One interviewee in Texas took paddling to reduce the number of days in detention: "The principal said I could take two licks and get some of the days reduced. I didn't want to stay for the after-school detention, so I took the deal."[112] A seventh-grade boy in Mississippi watched a teacher paddle his peers in class: "He [the teacher] gave them the option of getting one lick in or three licks out. This was Social Studies. The kids were talking too much…. He told them to come up and he said 'do you want one in here or three out the door?' So they chose one lick. The class started laughing."[113]

Why Students Opt for Beatings

Students we interviewed chose corporal punishment for reasons that ranged from wanting to keep good grades to wanting to keep their parents from finding out; some simply did not know how much paddling would hurt. A twelfth-grade girl said she chose paddling the first time because "that meant I got my lunch detention erased." She noted, however, "I would have made a different decision if I had known how much it would hurt."[114]

Many students said they chose corporal punishment in order to avoid missing classroom instruction or suffering other academic consequences. A recent graduate in Texas told us, "I chose licks. If I had got written up, and suspended, I would have had to play catch-up. I would have missed class."[115] One student saw paddling as the better academic option: "I would take the paddling because I ain't trying to flunk out or anything."[116] An honors student at a Texas high school explained the calculation she and her friends make:

[My school] uses corporal punishment as a way to get out of SAC [StudentAssignmentCenter, or in-school suspension] … it's three swats to get out of SAC…. My freshman year, two friends of mine-they were girls-chose to get the swats…. It meant they could still "exempt the exam"… that means you use your [classroom grade point] average instead of taking the final. So my friends chose to get swats so they wouldn't have SAC and they wouldn't have to take the exam. I mean, who wants to take an exam if you don't have to?[117]

Some students, especially younger students, might think that the alternative punishment is more unpleasant than the beating. These students simply do not have the maturity to make such a decision, and should not be put in this position. A mother whose 10-year-old was paddled felt her son wasn't old enough to make that choice: "The principal said he asked my son whether he wanted two pops or two days of ISS and no field trip. He always wanted to go on field trips…. So how are you going to ask this child whether he wants two pops when he is 10 years old?"[118]

Male students may choose paddling in part because of a desire to meet perceived societal expectations of masculinity. One former high school teacher in Mississippi noted, "It's always one bad thing versus another bad thing-which one are you ready for? And with masculinity and the pressures to be tough and unfeeling, often the young man is going to want to take the licks. Take it like a man. It's almost a show when you offer the bargain."[119] This attitude affects even young children, according to one former teacher in Mississippi: "There's a certain amount of bravado that comes with it, you want to take your licks like a man, not crying or anything."[120] He emphasized, "with boys, it's a badge of courage to choose corporal punishment over ISS."[121]

A parent in rural Mississippi noted some obstacles to choosing suspension above corporal punishment: "Their parents have jobs. Their moms have jobs. They say they can't sit home [with the child]."[122] A superintendent in a district that uses paddling described the complications of this dynamic: "When you tell a parent we have to send the child home for a day, the parent will ask, 'can you not paddle them? I'm going to be at work. They'll be home by themselves.'"[123]

Sometimes schools do not tell parents about beatings and so, unlike with a suspension, the student's parents do not find out about the underlying infraction; this motivates students to choose corporal punishment. One Mississippi mother's son had been paddled when he was 17 years old; she did not find out until he was 22:

The school did this thing where they told the kids to take the paddling, don't tell anyone, and it would be over … [my son] says he got paddled almost every day…. That was an example of how they covered it up so the parent didn't know. I had signed the card for no paddling … I think they went so far as to tell [my son] that we'll just give you some licks and it will all be over and we won't have to call your mom.[124]

Many parents, like this Mississippi parent, disagreed with this scheme: "Your kid can get a paddling and you wouldn't know it…. Let me know. That's only right."[125]

Teachers and coaches sometimes directly pressure students not to tell parents about beatings. For instance, student athletes, for whom paddling can be a routine part of their training, might keep the abuse from their parents. One recent high school graduate noted, "for boys in the football program, they get licks without telling the parents. [The coach would give] them a choice-take your licks and we won't call your parents or we'll drop your grade and your parents will find out. It's your choice, it's up to you."[126]

Some students prefer to be paddled rather than have parents informed of the infraction because they feel punishment at home might be worse. A former high school teacher felt that her students' attitude was: "You get three smacks on the behind, you shed a tear, and it's over. Your parents don't know and they're not going to beat you."[127]

While students should not be subjected to abuse at home, this is not a reason to give the student the option of "buying" the school's silence by submitting to physical harm as a form of discipline. It is a recognized principle of human rights that children should have a voice in the policies and procedures to which they are subjected.[128] However, in this context, providing children a choice between physical beatings or another disciplinary option is not a rights-protective policy. Providing students a choice in this context is fundamentally exploitative, preying on vulnerable young people with underdeveloped decision-making capabilities.

IV. Offenses Leading to Corporal Punishment

Students are beaten in schools for a wide range of infractions. Though corporal punishment is never a legitimate response to misbehavior, it is particularly troubling when used as a disproportionate, angry response to minor infractions that might reasonably be expected from any child. The punishment is frequently meted out in an arbitrary manner, leaving students unsure why they were punished and angry about the injury they have suffered. Even in cases where students committed serious infractions, corporal punishment is not an effective method of redressing the problem.

Disproportionate Responses to Minor Misbehavior

The large majority of instances of corporal punishment reported to Human Rights Watch was for minor infractions, such as having a shirt untucked,[129] being tardy (late to class or to school),[130] or talking in class[131] or in the hallway.[132] While no student behavior should result in corporal punishment, it is egregious when applied for minor transgressions such as these.

As Justice Byron White observed when dissenting from a US Supreme Court decision allowing school corporal punishment, "[i]f there are some punishments that are so barbaric that they may not be imposed for the commission of crimes, designated by our social system as the most thoroughly reprehensible acts an individual can commit, then … similar punishments may not be imposed on persons for less culpable acts, such as breaches of school discipline."[133]

One teacher described a policy in which teachers were required to lock classroom doors when the bell rang; students who were still in the hallway were then paddled by an administrator patrolling with a paddle in hand before they could attend class.[134] A superintendent in a district that uses corporal punishment noted that the practice is particularly unpleasant if used for minor misbehavior: "I hate to think that a child gets three or five swats for being late to class, I hate to think that a child gets three or five swats for running in the hall-those are minor infractions."[135]

Despite this superintendent's concern, Human Rights Watch received reports of corporal punishment in response to a wide range of minor misbehavior. Students were paddled for eating or drinking in class,[136] sleeping in class,[137] walking on the wrong side of the hallway,[138] running in the hallway,[139] talking back to a teacher,[140] not turning in homework,[141] not having a belt in violation of the dress code,[142] and going to the bathroom without permission.[143] While some kind of disciplinary response to these misbehaviors may well be warranted, corporal punishment is grossly disproportionate. Teachers and students said that minor misbehavior leads to somewhere between three and five blows.[144] An 18-year-old noted, "You could get a paddling for almost anything. I hated it. It was used as a way to degrade, embarrass students."[145]

Students in the early grades receive corporal punishment for behavior typical among young children. This is especially problematic because while young children may immediately comply with adults' wishes, they frequently do not remember why they are being hit and will only refrain from future misbehavior if they face an imminent threat of violence.[146] A middle school boy in Mississippi was beaten for throwing paper balls at the teacher: "I was just trying to make the class more fun. Eventually after I threw about four or five paper balls she got really mad and sent me and my friends to the office and we got a whuppin'."[147] Two kindergarteners were paddled for playing a child's version of "footsie": "Me and my friend, we were stepping on each other's feet. [The teacher] called us both into the hall and … gave us three licks and sent us back into the classroom."[148]

In Texas, we received reports that coaches would paddle student athletes for bad grades. One 16-year-old student athlete said, "We had to show [coach] our grade sheets, we had to take it around to get it signed by all the teachers and then take it back to the coach."[149]

Disproportionality also arises where students or parents have the option of choosing another punishment such as suspension.[150] In such cases, students who refuse to be beaten typically receive a punishment that the school usually reserves for more serious infractions. A student who, for example, was tardy, and then chose to exercise his right not to be beaten, might then be suspended.[151] According to the hierarchy of punishment established by the schools, the suspension is the more serious punishment. In effect, students are being further punished for asserting their right to be free from physical violence.

Vague Offenses and Arbitrary Use of Corporal Punishment

Students and teachers reported that students could be paddled for a catch-all category of "disrespect," a term which is rarely defined in school policy and is used arbitrarily by teachers. In some cases, this is a category that can be checked on the school's official discipline form when a student is referred to the principal's office for paddling.[152] One Mississippi teacher implied it can be a catch-all term used to discipline students at the teacher's whim:

Disrespect can mean different things. Disrespect is doing something that you are told not to do. Not doing your work, talking out of turn, raising your voice to another teacher, putting your hands on another student. Breaking the rules. But it depends on a person's definition of respect.[153]

One middle schooler described punishments for "disrespect" as: "if you mess up, and don't say ma'am or sir."[154] A high school girl objected to being written up for a dress code violation, stating that she was not aware of the new rule; the teacher then wrote her up for "disrespect" instead.[155] Another similarly vague term for which students are sometimes paddled is "defiance of authority," which, as a recent high school graduate in Mississippi noted, "could be anything; that phrase could mean anything. Teachers threw it around all the time."[156]

Corporal punishment is sometimes administered arbitrarily, with inconsistent rules, underscoring the inefficacy of the punishment.[157] One teacher noted that at her high school in the Mississippi Delta, the reasons for giving corporal punishment were "vague," and that "there was never, at my school, a list of things that a kid did wrong that would result in corporal punishment."[158] One former teacher noted that whether or not a child received corporal punishment "just depended on the teacher. The only school-wide rule was no food or drink in the classroom."[159] A former student from Texas agreed, "Whether you get in trouble, whether you get paddled, it depends on the teachers."[160] A teacher noted that she thought it was "least effective because it was a catch-all punishment."[161] In these situations, students are not given adequate notice or clear rules that would indicate when they will be punished.

Corporal Punishment for Serious Offenses, including Violence

Some students we spoke with were subjected to corporal punishment for more serious infractions. Fighting in particular led to corporal punishment of students in both Mississippi[162] and Texas.[163] Even very young students who were caught fighting were then beaten: Human Rights Watch spoke with a student who was paddled after fighting in second grade,[164] and another student who was paddled after hitting another child on the head with a chair in third grade.[165] One student we interviewed was paddled for setting off firecrackers in school.[166] Students on a field trip were reportedly paddled for getting drunk.[167]

A superintendent who is against corporal punishment nonetheless reflected a popular sentiment when he observed that corporal punishment may be "more appropriate for major infractions: gambling, aggression towards other students."[168] While students who commit serious offenses need effective discipline, corporal punishment is not an acceptable answer.

Under international law, in "exceptional circumstances … dangerous behavior [may] justif[y] the use of reasonable restraint," but that force must be the minimum amount necessary for the shortest period of time, and must never be used to punish.[169] Educators are confronted with the difficult task of maintaining order and ensuring a safe environment for their students, while avoiding the use of unnecessary force. Therefore, they must be trained to respond to dangerous behavior, "both to minimize the necessity to use restraint and to ensure that any methods used are safe and proportionate to the situation and do not involve the deliberate infliction of pain as a form of control."[170] Educators should only use force when absolutely necessary, and should do so in compliance with the strict limits articulated in international law.[171]

Contrary to this standard, we received some reports that excessive and unnecessary force was used to control students. For instance, a Mississippi high school girl reported that when fights break out in the gym at her school, the principal and assistant principal "come up into the bleachers and put their hands on the girls and choke them, and slam them … [they put their hands] on their necks, they'll grab them all types of ways…. The principal is the biggest man at our school and he can literally just throw down anyone."[172] Elsewhere in Mississippi, two young students, both of whom have mental disabilities, were physically pushed into closets as punishment after acting out in class.[173]

V. Prevalence of Corporal Punishment in US Public Schools

Data on Corporal Punishment

223,190 students nationwide received corporal punishment at least once in the 2006-2007 school year, according to data from the Office for Civil Rights (OCR) at the United States Department of Education.[174]

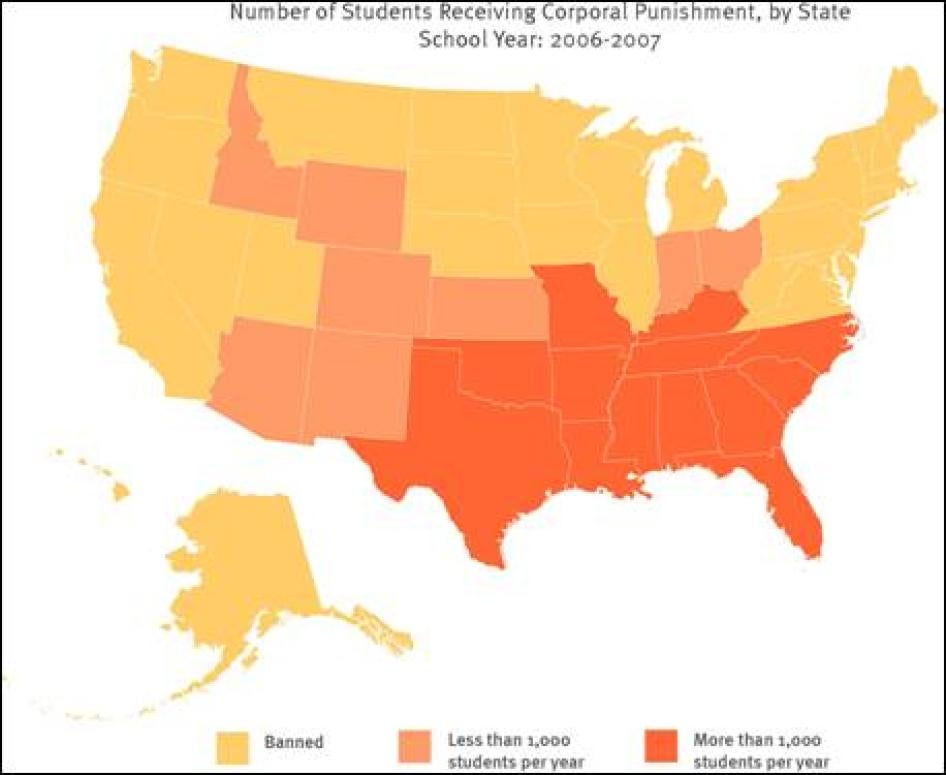

Figure 1

© Human Rights Watch, 2008.

While corporal punishment is legal in 21 states,[175] Table 1 shows that it is used more heavily in some states than others. In Texas alone, OCR data show that 49,197 students were subjected to corporal punishment during the 2006-2007 school year, more than in any other state.[176] In Mississippi, 7.5 percent of schoolchildren were paddled at least once during that same school year, the highest percentage in the nation.[177]

Table 1: Nationwide Prevalence of Corporal Punishment

State |

Number of Students Paddled During the 2006-2007 School Year |

State |

Percentage of Students Paddled During the 2006-2007 School Year |

Texas |

49,197 |

Mississippi |

7.5% |

Mississippi |

38,131 |

Arkansas |

4.7% |

Alabama |

33,716 |

Alabama |

4.5% |

Arkansas |

22,314 |

Oklahoma |

2.3% |

Georgia |

18,249 |

Louisiana |

1.7% |

Tennessee |

14,868 |

Tennessee |

1.5% |

Oklahoma |

14,828 |

Georgia |

1.1% |

Louisiana |

11,080 |

Texas |

1.1% |

Florida |

7,185 |

Missouri |

0.6% |

Missouri |

5,129 |

Florida |

0.3% |

Source: United States Department of Education, Office for Civil Rights, "2006 Civil Rights Data Collection."

Corporal punishment was widely accepted in US public schools in the latter part of the 19th century and the early 20th century.[178] While New Jersey banned corporal punishment by statute in 1867,[179] many other US states, including Michigan, Connecticut, and Nevada, did not enact a ban until the late 1980s or early 1990s.[180] In the present decade, the number of students subjected to corporal punishment in US public schools has been steadily dropping. OCR data indicate that 342,038 children in US public schools were paddled in the 2000-2001 school year;[181] by the 2004-2005 school year, the figure had dropped to 272,028 students.[182] In 2006-2007, the most recent school year for which data are available, the numbers fell to 223,190.[183] Any level of corporal punishment is too high; the fact that the numbers are dropping shows that districts still using paddling are becoming the exception, making it all the more imperative that they change their discipline policies.

Boys are subjected to corporal punishment more than girls: nationwide, boys make up 78.3 percent of those paddled.[184] African-American students are paddled at more than twice the rate than might be expected given their percentage of the student population: African Americans constitute 17.1 percent of the nationwide student population, but 35.6 percent of those paddled.[185] Though girls as a group are paddled less than boys, African-American girls are more than twice as likely to be subjected to paddling as their white counterparts.[186]

Special education students[187] are also subjected to corporal punishment, even though the behavior that leads teachers or administrators to beat them may result from their disabilities rather than any lack of discipline.[188] Nationwide, OCR data indicate that 41,972 special education students received corporal punishment in the 2006-2007 school year.[189] In the two states examined in detail for this report, Mississippi and Texas, large numbers of special education students were among those receiving corporal punishment. In Mississippi, 5,831 special education students were beaten in the 2006-2007 school year.[190] In Texas, 10,222 special education students were beaten, amounting to approximately one-fifth of the total number of students who were beaten statewide.[191]

While these figures and rates may already appear quite high, they do not reflect the full extent of the problem. First, the data record the number of students hit each year, not the number of incidents.[192] In other words, the data show that 223,190 individual students were beaten in the relevant school year, but do not show how many incidents of corporal punishment occurred. Because many students likely were beaten more than once in a school year-a reasonable assumption given the evidence collected from our interviewees-the overall number of beatings administered each year undoubtedly is far higher.

The data also very likely undercount the number of students beaten each year because some school districts fail to report all incidents to the federal government. Corporal punishment is often seen as a quick form of discipline: a former high school teacher recalled that "paddling was just a fast way to deal with it and not write it down."[193] Records are not always kept for corporal punishment: a high school teacher noted that discipline is "completely haphazard … many teachers don't even bother with writing referrals anymore."[194] One superintendent of a major Mississippi school district told us the reported numbers were low:

[W]e probably do it twice as much as reported…. [T]here is no documentation you have to send to the central office to say that you did it…. [It's] an option where you don't have to do so much documentation, It's much easier than signing the suspension form and giving it to the parents or any of that. I'm speaking realistically.[195]

Incidents of corporal punishment may not be recorded when they do not take place in the principal's office (or the school's "main" office). A Mississippi teacher told us:

I know that there are paddlings that aren't reported…. A concrete example: during my planning period, I spent a considerable amount of time in this one teacher's class. I've seen the teacher ask students to get the paddle from the corner, wait outside for him, the students are paddled, they come in, and class resumes. No paperwork is filled out. I'm sure if you ask teachers, they wouldn't be able to tell you how many students they paddled at the end of the day.[196]

Informal referrals from teachers to coaches might not be recorded. Another Mississippi teacher reported that "[w]here the coach is giving licks, the coaches don't report to the office. It's sort of part of the coaching, [the coach's] rights, which contributes to the lack of data on corporal punishment."[197] The lack of record-keeping may be particularly evident when students are paddled in hallways or classrooms. One former Mississippi teacher, who frequently saw her principal administer corporal punishment in the hallway, noted, "Oh yeah, he [the principal] never reported it. He never took names; he didn't know who all these kids were."[198] It is unlikely such instances of informal, unregulated corporal punishment are recorded by the administrator upon return to his or her office.

Constant and High Levels of Paddling in Some Schools

Routine, high levels of paddling in schools can indicate a threatening, violent environment.[199] A former assistant principal in charge of discipline at a middle school in Meridian, Mississippi, recalled that he received 19-23 referrals for paddling every day; one day he had 37 students sent to his office to receive a beating.[200] Interviewees described long lines of students waiting to get paddled outside the principal's office.[201] One teacher noted his elementary students were punished so often it had become routine: "The kids would put their hands on the back of the chair, stick their butts out, and the principal would start hitting."[202]

Corporal punishment is so commonplace in certain public schools in Texas and Mississippi that students reported high levels of paddling in casual tones. A high school boy in Texas recalled, "I was paddled in elementary, yeah. Too many times to count."[203] A Mississippi high school girl observed that she was paddled "at least three times a week" in the ninth and tenth grades.[204] She estimated that "at least 60" students are paddled daily at her school, noting, "A lot of kids get paddled. Every class block you will hear a list of students being called [to the office for paddling] on the intercom."[205]

We received reports of students of all ages receiving corporal punishment, from pre-kindergarten to high school. A Mississippi middle school boy recalled receiving three blows as a kindergartener for making another child eat dirt in the playground.[206] Another Mississippi kindergartener was beaten three times for stepping on another student's feet.[207] An east Texas kindergartener was paddled for pulling a chair out from underneath another student.[208] Among our interviewees, paddling was no less common in older grades. We received reports of paddlings administered to a twelfth-grade girl in Mississippi,[209] an eleventh-grade girl in Texas,[210] and a 17-year-old boy in Mississippi.[211] A former teacher recalled that one of her high school students was paddled despite being "a really big kid … [for whom] the paddle just seemed kind of silly."[212]

VI. Impact of Corporal Punishment

Corporal punishment in schools harms children and damages their education. The practice almost always causes immediate pain, and can result in lasting physical injury. It humiliates and degrades students, and may leave them depressed or withdrawn. Corporal punishment teaches students that violence is acceptable: it can make students aggressive, angry, and more likely to lash out against their peers or educators, and it can teach them that domestic violence is permissible. Furthermore, as a result of being physically punished, students can become less engaged in school, less motivated to succeed, and may become more likely to drop out.

Lasting Injuries and Immediate Pain

Many victims of corporal punishment in schools sustain serious injuries, as noted by the Society for Adolescent Medicine, including severe muscle injury, extensive bruising, and whiplash damage.[213] A girl in Mississippi was paddled in sixth grade: "[The coach] hit me so hard I felt nauseous at my stomach. I was mad because I remember I came home to take a shower, and I was like, I'm going to look and see if I have bruises. And I looked in the mirror and I had bruises all over, and I said, 'Mama, come look.'"[214] Her mother took her immediately to the local hospital's emergency department for medical care,[215] and also reported the incident to the sheriff's office.[216] The same girl was paddled in twelfth grade: "[The principal] reared back and paddled me … you could see where the paddle hit and it was really red…. That was first period and I had bruises by third period."[217] Once again, her mother took her to receive medical care,[218] and filed a sheriff's report.[219]

A middle school student in rural Mississippi was severely bruised when his beatings escalated. He was sent to the office for paddling, and "[w]hen I came back, [the teacher] said I was laughing so she sent me back and I got three more licks…. The principal was like, 'you're in here again already?'… He said, 'Do you realize that every time you come in here I'm going to hit you harder and harder?'"[220] When his mother met him after school, she noticed he was in pain. She found his buttocks were black from bruising.[221] It took more than a week for the bruises to heal, and during this period "he couldn't sit down."[222]

One very young student in Texas, a three-year-old boy attending a public pre-kindergarten program, was beaten and bruised during paddling. The program was run at the local elementary school and governed by the school district policy on discipline.[223] The boy, who has diagnosed Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), was paddled for taking off his shoes and for playing with an air conditioner. He became reluctant to go to school: his mother reported that "all he would say is that 'she [the principal] hit him with a board.'"[224] The child sustained bruises to his hips that reached around to his belly button.[225] While this case may seem exceptional, it is a direct byproduct of the climate created in school districts by the regular use of corporal punishment.

Some students sustain injuries to other body parts. An 18-year-old San Antonio, Texas, girl sued her school district when she was hit on her buttocks and her hand. Her hand was injured when she tried to block one of the blows. She went to the emergency room with a severely swollen hand that was put into a cast.[226] An injury to a hand is not unique to this case; many students use their hands or arms to protect themselves. Among our interviewees, a Mississippi high school junior reported that she reached back when the principal was swinging and was hit on her arm,[227] and a Mississippi middle school boy reported that when the principal was about to paddle him, the boy put his hand back and the principal hit his thumb with the paddle.[228]

In one case the student paddled was visibly pregnant, as a Mississippi teacher described:

I had a pregnant girl get paddled once for being tardy. She was five months pregnant. She was 16. The principal paddled her … she was showing and it was known that she was pregnant. She was part of a group that was tardy to class. And she yelled something along the lines of "you shouldn't paddle me, I'm pregnant."[229]