"They Shot at Us as We Fled"

Government Attacks on Civilians in West Darfur in February 2008

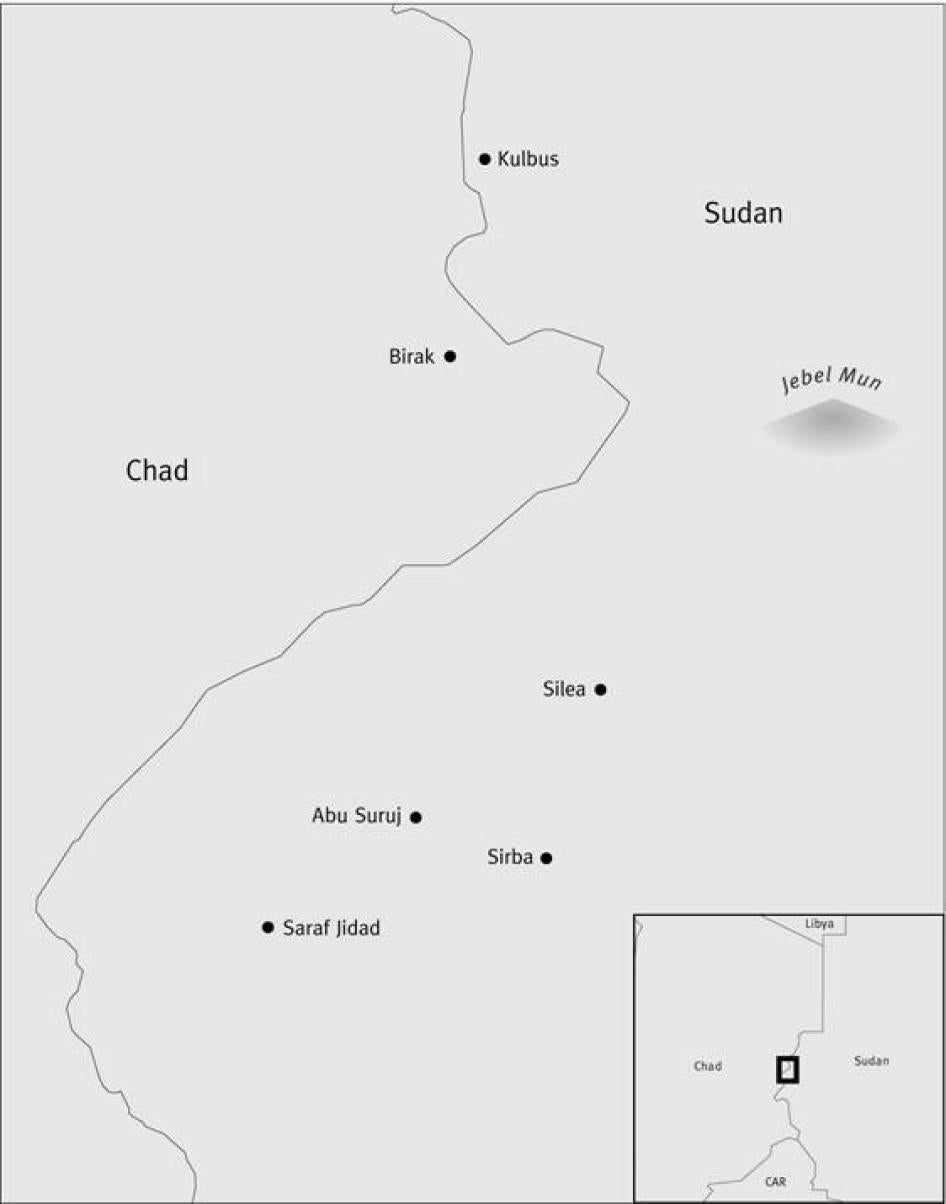

Map of Northern West Darfur

I. Summary

The Sudanese government's large-scale attack on towns in rebel-held areas of West Darfur in February 2008 was a vicious reprise of "scorched earth" counterinsurgency tactics from 2003 to 2005. The Sudanese armed forces and government-backed Janjaweed militia killed and wounded hundreds of civilians and caused widespread property damage and looting in violation of international humanitarian law.

The February attacks highlight the severe inadequacy of international protection efforts, namely the United Nations-African Union Mission in Darfur (UNAMID). The failure of the United Nations (UN) Security Council to strongly condemn these attacks and impose sanctions on those responsible points to a larger failure by concerned governments to effectively confront the Sudanese government to ensure the protection of civilians at risk.

On February 8, 2008, Sudanese government forces attacked the towns of Abu Suruj, Sirba and Silea, all located close to the Chadian border in the plains north of the West Darfur capital Al-Geneina in an area known as the "northern corridor." Ten days later, government forces attacked Jebel Mun, a mountainous rebel stronghold some 80 kilometers north of Al-Geneina. Each attack involved Sudanese air and ground forces and hundreds of Janjaweed militia. The attackers killed more than 120 civilians, injured hundreds more and destroyed and pillaged civilian property, including homes, schools, medical facilities, and food and water supplies.

In Abu Suruj, soldiers and Janjaweed burned down three-quarters of the town and killed at least 30 civilians, most while attempting to flee. In a simultaneous attack on nearby Sirba, more than 40 civilians were killed, many by attack helicopters or by soldiers using heavy machineguns mounted on four-by-four vehicles. Later the same day, soldiers and Janjaweed attacked Silea to the north, killing at least 20 civilians and looting homes, shops and the premises of four nongovernmental organizations. Following the attacks, government military and police forces were stationed in each town, and in the days and weeks that followed, soldiers in Silea were reportedly responsible for further killings and incidents of rape.

On February 18, 19, and 22, 2008, government forces assaulted Jebel Mun, targeting rebel positions located within or near civilian settlements. Starting on February 18, aircraft bombed a displaced persons' settlement near Jebel Mun and several villages around the mountain, using Russian-built Antonov transport planes and other fixed-wing aircraft and attack helicopters. On February 19 and 22, aerial bombing was accompanied by ground attacks in which soldiers and Janjaweed entered villages around Jebel Mun and shot at fleeing civilians. Those who could not flee, including disabled and elderly people, burned to death in their homes as militia deliberately set their huts on fire.

Following the February 8 attacks, many civilians fled to Jebel Mun for safety, and fled a second time after government forces assaulted Jebel Mun. At least 13,000 sought refuge in Chad, where many settled close to the border in the hope of returning to their villages ahead of the rainy season in June. More than 5,000 people have moved to refugee camps run by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) further inside Chad. Others fled south to Al-Geneina. During their flight, families were separated and some reported missing children to humanitarian agencies.

While many civilians returned to the towns of Abu Suruj and Sirba in the weeks following the attacks, few have returned to Silea and Jebel Mun. Continuing insecurity caused by clashes between Sudanese forces and rebels of the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) near Jebel Mun has made Silea and Jebel Mun largely inaccessible to humanitarian agencies.

The February 2008 clashes and ongoing insecurity in the northern corridor underscore the urgent need for wider, quicker and more effective UNAMID deployment. UNAMID is mandated under Chapter VII of the UN Charter to protect civilians "under imminent threat of physical violence and prevent attacks against civilians, within its capability and areas of deployment." However, in February, UNAMID was without the necessary troops and logistical support to effectively protect civilians in the areas under attack.

The failure of UN member states to contribute sufficient appropriate personnel and equipment to the UNAMID forces, combined with continuing political weakness in confronting Sudan's obstruction of UNAMID's deployment, undermines the effectiveness of UNAMID and threatens the credibility of the UN's operational peacekeeping and protection role.

Human Rights Watch's field research found that during the February 2008 attacks the Sudanese government committed numerous violations of international humanitarian law. There is no evidence that rebel forces were even present in Abu Suruj, Sirba and Silea when they were attacked by government forces and militia, indicating that the attacks on civilians and civilian property were deliberate. In the attack on rebels in Jebel Mun, armed forces and militia deliberately targeted civilians and conducted attacks that were indiscriminate or caused civilian loss disproportionate to any expected military gain. Individuals who committed, ordered or held command responsibility for these attacks are responsible for war crimes. The government should prosecute those implicated, regardless of rank, according to international fair trial standards.

The rebels bear some responsibility for failing to take all feasible precautions in the Jebel Mun area to safeguard civilians and property in areas under their control from the effects of attacks, and may have deployed forces within or near densely populated areas.

The international response to the February attacks was appallingly muted. UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, UNAMID officials, and UN member states issued statements condemning the attacks, but, critically, the UN Security Council took no steps to hold Sudan responsible. In March 2008, the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights issued a detailed report on the attacks committed by government forces in January and February, urging Khartoum to prosecute those responsible. To date, Sudan has taken no steps to ensure accountability for war crimes committed in February 2008.

Instead, the Sudanese government continues to disregard its international humanitarian law obligations and flout UN Security Council resolutions, including the ban on offensive military over-flights, the disarming of the Janjaweed militia, and cooperation with the International Criminal Court (ICC) at The Hague. An entrenched pattern of impunity persists in Darfur, exacerbated by Sudan's failure to use national justice mechanisms to punish perpetrators of crimes in violation of international law and its failure to hand over indicted war crime suspects Ahmed Haroun and Ali Kosheib to the ICC.

Human Rights Watch calls upon the UN Sanctions Committee to impose targeted sanctions on Sudan, including travel bans and asset freezes on senior civilian and military officials involved in these attacks. The UN Security Council should also establish and monitor a clear set of benchmarks, drawn from UN Security Council resolutions, for all parties to the conflict that includes compliance with their international law obligations, and imposes sanctions for non-compliance. The benchmarks should include ending attacks on civilians and offensive military over-flights, ending support to Janjaweed militia, facilitating UNAMID deployment and freedom of movement and promoting accountability in meaningful ways. Crucially, UN member states should ensure that UNAMID has adequate personnel, equipment, technical expertise and other resources to respond rapidly and effectively to threats to civilian protection.

II. Recommendations

To the Sudanese government

- Issue clear public orders to all commanders of government forces and government-supported Janjaweed militia to immediately cease all attacks on civilians and civilian property in Darfur.

- Investigate alleged violations of international humanitarian law in West Darfur in February 2008, and any allegations of subsequent violations by the Sudanese armed forces, police or Janjaweed militia; bring perpetrators to justice, and provide reparations for the victims of such abuses, including by recovering and returning looted property.

- Suspend from official duties Sudanese officials who are alleged to have participated in the February 2008 attacks, either directly or through command responsibility, and in any subsequent violations of international law.

- Actively facilitate the full deployment of an effective UNAMID force throughout Darfur, including by immediately and formally agreeing to the deployment of non-African troops, and by ending all obstruction and delay of equipment and personnel.

- Ensure that UNAMID is able to fulfill its mandate to protect civilians in Darfur by implementing in full the Status of Forces Agreement signed in February 2008, particularly the provisions for UNAMID to have the right to freedom of movement throughout Darfur, including to conflict-affected areas.

- Cease all military, financial and political support to and recruitment of abusive Janjaweed militia, and immediately implement disarmament programs in accordance with relevant international standards.

- Cease all offensive military over-flights and other breaches of the UN arms embargo pursuant to UN Security Council Resolution 1591.

- Investigate all incidents of alleged crimes against humanity, war crimes, and other violations of international law committed in Darfur since 2003, including those committed by members of the Sudanese armed forces and Janjaweed militia; try alleged perpetrators in accordance with international fair trial standards; and provide reparations, including the return of confiscated property, to victims of abuses.

- Facilitate full and unimpeded access of humanitarian personnel and the urgent delivery of humanitarian assistance to civilians.

- Fully cooperate with the International Criminal Court, pursuant to UN Security Council Resolution 1593, including handing over Ahmed Haroun and Ali Kosheib in accordance with arrest warrants issued on April 27, 2007.

To rebel groups and former rebel groups

- Issue clear orders to all commanders to abide by international humanitarian law, especially with respect to civilian protection.

- Appropriately discipline any member alleged to have participated in violations of international law.

- Facilitate full and unimpeded access of humanitarian personnel and the urgent delivery of humanitarian assistance to civilians.

- Fully cooperate with UNAMID and ensure it can carry out its mandate unhindered, allowing for full freedom of movement throughout Darfur including to conflict areas.

To the United Nations Security Council and UN Member States

- The Security Council should task the Panel of Experts to investigate the attacks in West Darfur in February 2008 and continuing attacks on civilians, to report, promptly and publicly, to the Sanctions Committee on any violations of international humanitarian and human rights law, of the arms embargo and of the ban on offensive military over-flights, and to provide a list of those who are responsible. Impose targeted sanctions including travel bans and asset freezes on those individuals.

- Establish and monitor benchmarks for all parties to the conflict including on compliance with their obligations under international humanitarian and human rights law, and impose sanctions for non-compliance. These benchmarks should include: ending attacks on civilians and civilian property; ending unlawful use of UN markings on aircraft; ending support to abusive Janjaweed militia and initiating disarmament programs; facilitating UNAMID deployment and freedom of movement; ending impunity and promoting accountability through cooperation with the International Criminal Court and by undertaking legal reforms to strengthen Sudan's national justice mechanisms.

- Ensure UNAMID has adequate personnel, equipment, technical expertise, and other resources to protect civilians through rapid response and frequent patrolling in conflict areas.

To the United Nations-African Union Mission in Darfur

- Ensure that UNAMID has strong rapid response capabilities, including sufficient personnel, attack helicopters and armored personnel carriers and information gathering and analysis technology to carry out daytime and nighttime activities that could include reconnaissance missions, placing peacekeepers in positions to protect civilians prior to expected attacks, providing armed protection to civilians who come under attack, conducting search and rescue missions if humanitarian or other convoys are hijacked, or investigating ceasefire violations immediately after they occur.

- Deploy fully equipped, quick reaction forces to respond immediately to imminent threats to civilians and humanitarian operations, including in the "northern corridor" of West Darfur and along the Chad-Sudan border and in cooperation with the European Force (EUFOR) peacekeepers to be deployed in eastern Chad. Ensure UANMID establishes a permanent presence and actively patrols in northern West Darfur where civilians are at risk from continued armed conflict.

- Ensure that all units are instructed, prepared and able to take all necessary measures to fulfill their mandate to protect civilians to the greatest extent possible with available resources. This requires ensuring that all forces understand and are instructed to take all necessary means to protect civilians under imminent threat of attack and exercising full freedom of movement throughout Darfur including in conflict-affected areas.

To the International Criminal Court

- Investigate and prosecute senior civilian and military officials and leaders of non-state armed groups responsible for offences committed in West Darfur in February 2008 within the court's jurisdiction.

III. Methodology

This report is based on a fact-finding mission to the Chad-Sudan border area in March 2008. Human Rights Watch conducted more than 60 interviews with victims and eyewitnesses to the February attacks, humanitarian aid workers, local leaders and other sources. The names of persons interviewed have been withheld or changed for security reasons. Information provided by those interviewed was supplemented and cross-checked through telephone interviews and other remote research.

IV. Background to February Attacks

Jebel Mun, a mountainous area about 80 kilometers northeast of the provincial capital Al Geneina, has been a stronghold for Darfur's rebels since early in the conflict.[1] The summit, which covers an area about 10 square kilometers, is considered militarily strategic because of its rocky terrain that deters attackers and provides hiding places, and because of its proximity to the Chad border.

The "northern corridor"-from Al Geneina to Jebel Mun-is populated primarily by Messeriya Jebel and Erenga communities. The government and Janjaweed militia[2] have repeatedly attacked civilians and rebels living in and around the mountain and in the northern corridor.[3] Militia attacks spiked from April to July 2007, resulting in increased incidents of harassment, beatings, sexual violence, and extortion.[4] Government forces either allowed the attacks, attributing them to "inter-tribal tensions" or directly participated in them.[5] As a result of insecurity, starting from mid-2006, several communities established armed local defense forces.[6]

In December 2007 and January 2008, the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) rebel group launched a major military offensive in the northern corridor, and claimed to have surrounded the capital Al Geneina.[7] The government had a sparse presence in the area and put up little resistance. On January 7, 2008, JEM forces attacked the police station in Saraf Jidad, a town of about 15,000, prompting the police's withdrawal from town.[8] Reported laws of war violations by rebel forces during the offensive included the killing of three civilians near Silea and the assault and detention of local officials in the town to gain control.[9] JEM's occupation of Saraf Jidad and Silea was brief.[10]

In January 2008, the Sudanese government built up its military forces in Al Geneina in preparation for a counter-attack on JEM. Sudan Minister of Defense Abdelrahim Mohamed Hussein visited Al Geneina and held meetings with the local security authorities and Arab community representatives. According to United Nations (UN) sources, he allegedly gave clear instructions he wanted the northern corridor cleared of armed groups. At a meeting with UN officials on January 31, 2008, the deputy governor of West Darfur stated that the government was determined to recapture areas under JEM control.[11]

Members of the Erenga community told Human Rights Watch that they, too, met with government security officials two weeks before the attacks and told them that there were no rebels in their areas.[12] They said the authorities assured them that the military would move through their areas en route to attack rebel positions at Jebel Mun and that local defense forces should "welcome" government forces as they passed through.[13]

During this period in which the government was preparing to launch attacks on the areas that JEM had taken, government-supported Janjaweed militia attacked Saraf Jidad three times, most seriously on January 24. In that attack, Janjaweed exchanged fire with JEM rebels in nearby hills before entering the town and torching houses and shooting at civilians. The attack resulted in 24 civilian deaths, including the umda (traditional leader), elderly people, women and children. The attackers burned about half the town and forced thousands of civilians to flee to Abu Suruj, Tandelti and other villages.[14]

Meanwhile, the government closed off the northern corridor to humanitarian aid organizations and UN agencies from mid-December 2007 to early February, leaving an estimated 160,000 civilians without humanitarian assistance.[15] An April 2008 report from the UN secretary-general on UNAMID deployment concluded that lack of humanitarian access during the first 40 days of the year "was particularly damaging to humanitarian operations and had an extremely negative impact on civilians in the area."[16] Once the government reoccupied the northern corridor in February, humanitarian access was again allowed, but except for brief visits in early March and mid-April 2008, the agencies have yet to access Jebel Mun.

In early February, an attempted coup in Chad further exacerbated the situation between the Sudanese government and JEM. Sudan and Chad have long accused one another of fomenting rebellion through support to each others' insurgents.[17] The Sudanese government supported Chadian rebels in an attempted coup in the Chadian capital N'Djamena on February 2-3, 2008, while Sudanese JEM rebels, many with family and ethnic ties to Chad, helped the Chadian government to repel it.

Chadian rebels based in West Darfur have attacked Chadian government positions in eastern Chad, most recently on April 1, 2008.[18] The Chadian government has in turn used aircraft to bomb Chadian rebels in Sudan in January and April.[19] Chadian government forces also fortified JEM rebels inside West Darfur, notably during the period leading up to the February attacks.[20] JEM's links to the Chadian government provided another compelling incentive for Sudan to remove JEM from West Darfur. The group's engagement in N'Djamena provided a window of opportunity for the attack.[21]

In the wake of the failed coup attempt, the Sudanese government launched a large-scale military campaign to re-take the northern corridor and Jebel Mun on February 8, 18, 19, and 22. Its attacks on Abu Suruj, Sirba, Silea and in Jebel Mun are reminiscent of the "scorched earth" tactics the government used on civilian populations living in rebel areas from 2003 to 2005, both in terms of targeting civilians and of the scale of destruction and pillaging of civilian property.[22]

The February 2008 attacks appear to be part of a continuing pattern of attacks on civilian populations living in areas where rebel groups operate, particularly groups that did not sign the 2006 Darfur Peace Agreement, known as the "non-signatory" rebels.[23] The UN Panel of Experts tasked with monitoring Sudan's compliance with the arms embargo imposed in 2005 catalogued several such attacks in 2006 and 2007. For example, in November 2006, government forces carried out aerial and ground attacks on Hilef, a town in eastern North Darfur where rebels operated, killing 27 civilians.[24] In April and May 2007, the government bombed civilian sites, including a school and market, and killed at least two civilians in Um Rai, North Darfur, a known gathering point for non-signatory factions.[25]

The government's bombing campaign has continued in 2008. In April 2008, the government bombed a small village near Madu, killing one child, destroying homes, and causing the displacement of thousands of villagers.[26] In late April and early May 2008, the government bombed additional sites in rebel areas of North Darfur. On May 4, 2008, the government bombed a school and market, killing at least 13 people, including seven children.[27]

V. Attacks on Civilians by Government and Militia, February 2008

On February 8, 2008, the Sudanese government launched massive attacks on three major towns in the northern corridor, displacing an estimated 40,000 civilians to Jebel Mun and across the border to Chad. Then, on February 18, 19, and 22 the government went on to attack rebel positions at Jebel Mun, displacing thousands more civilians to Chad.

The timing and sequence of these attacks suggest the government had a strategy to drive civilians away from the area before assaulting rebel positions in Jebel Mun. The government carried out the attacks on three populated northern-corridor towns when many JEM rebels were still in Chad helping to repel the coup attempt there. According to various witnesses who spoke to Human Rights Watch, there were no rebel soldiers in these towns. The government used aerial and ground forces in ways that seem designed to terrorize the population.

The attacks were carried out in a similar pattern in all locations, using aerial and ground forces that included airplanes, helicopters, ground troops and large numbers of Janjaweed militia on horse and camels. Working in concert, these forces killed, assaulted, raped, and abducted civilians, destroyed their homes and villages, and looted and destroyed their property, including food and water stores. The government forces targeted civilians, particularly men, as they fled. In two cases documented by Human Rights Watch, attackers shot at fleeing women with babies on their backs, killing the babies. Humanitarian organizations, including clinics, were robbed and vandalized.

February 8, Abu Suruj

Abu Suruj, located about 30 kilometers northwest of Al Geneina, has a population of 18,000, a majority of whom are from the Erenga ethnic group. According to eyewitnesses, on the morning of February 8, 2008, government air forces, including an Antonov airplane painted in UN-designated white and at least two attack helicopters, flew over the town. Shortly thereafter, hundreds of armed men, whom eyewitnesses described as Janjaweed militia wearing green khaki uniforms and civilian clothes, arrived on horses and camels. A column of 30 to 45 green and gray military vehicles mounted with weapons followed them into the town.[28]

Witnesses said the soldiers and Janjaweed entered the town shooting in the air and directly at people, setting fire to houses, and looting livestock and property. The plane and helicopters circled overhead and bombed locations in and around the town, including hills where many civilians had fled for cover. About 30 civilians were killed, the majority of whom were shot while fleeing. Children, elderly and disabled people also perished, and some were burned to death in their huts.[29]

Mohamed, 60, told Human Rights Watch that he saw Janjaweed shooting at men while they were running north toward a mountain. "I saw seven people die while I was fleeing," he said. "One man was shot and fell down right in front me. Thank God I got to the mountain and was not hit."[30]

Many witnesses reported to Human Rights Watch that the attackers targeted the male population but allowed the female population to flee and take refuge in a wadi (small valley) on the east side of town. "They told us to take what we needed for the children and leave because they were going to burn down the house," said Zeinab, a 22-year-old woman who fled with members of her family. While fleeing, she saw one attacker order her uncle to stop and then shot him dead.[31]

Abdullah, a 40-year-old man, told Human Rights Watch that he got on his horse to escape the attackers, but soldiers shot at him. "I fell down and hurt my arm," he recalled. "I escaped into a house nearby. When I saw them coming, I went into the women's side and covered myself in a taub [women's garment] as a disguise to avoid being shot."[32]

The attackers looted and burned extensively. Eyewitnesses told Human Rights Watch that attackers set dwellings on fire using matches, but some houses were burned from rockets or other projectile explosives. According to a UN report, 75 percent of the village was burned.[33] Residents who fled the attacks told Human Rights Watch that more than 70 shops were looted.

Zeinab, the 22-year old who fled with her family, described to Human Rights Watch how a group of five Janjaweed on horses came to her house and stole all of her family's belongings before burning the house down. "They hit us with whips and sticks and said 'You are rebels. We want your animals.' Then they came inside and took our food and clothes, beds, mats, cups, pots and everything. They took the animals." To assist in the pillage, the Janjaweed militia enlisted a group of girls to shepherd the residents' cattle, goats and sheep to a location away from the village and guard them until the attacks were over.

Following the attack, government soldiers deployed in town. Janjaweed militia left at dusk and returned in the following days to continue looting and burning. According to family members of people who stayed, soldiers and militia prevented the remaining population from leaving and harassed those who returned for their possessions. While many fled to Chad initially, by early April 2008 most of the population had returned to rebuild their homes, in part drawn by assistance from humanitarian agencies.[34]

February 8, Sirba

Shortly after the attack on Abu Suruj began, government forces attacked Sirba, a town of approximately 10,000 located 50 kilometers north of Al Geneina and about 15 kilometers east of Abu Suruj. The air forces, including an Antonov and attack helicopters, preceded hundreds of armed men riding horses and camels and wearing green khaki uniforms. They entered town from the southeast direction and were followed by a column of around 30 military vehicles mounted with weapons.

"The planes came. Then the Janjaweed came on horses and encircled the village and some came into the village. Then the cars came," recalled Yahyia, a merchant who watched the attack from a hiding place. He said the attackers fired their weapons indiscriminately. "The attackers fired in the air and at people. If they saw people moving around, they shot at them."[35]

Yahyia also told Human Rights Watch that he saw gunship helicopters firing on houses and at people. According to civilians who buried the dead, at least 42 civilians were killed from bombs, rockets or gunshots.

"The cars had dushkas [automatic weapons] and they were shooting at everyone, whether a woman, man or child. They were shooting at us even when we were running away," said Nada, another eyewitness.[36]

Witnesses told Human Rights Watch the attackers accused the population of supporting the rebels. "They said they would kill us all because we follow JEM," said Hamed, a merchant.[37] Among those shot dead were the town's fersha (traditional leader) and the head of the secondary school. The fersha was reportedly burned after he was shot. While most of the civilian casualties were men shot while trying to escape their attackers, elderly men and women and small children also died from shots or from burning.

Selwa, a 48-year-old woman, was with a group of women who discovered several corpses. She told Human Rights Watch, "We went to my house and I found the father of my son dead. Then we went to the neighbors and found the secondary school director and another man dead. I took a blanket and covered them." She waited until dark before leaving for Chad, where she reunited with her children who fled separately.[38]

The soldiers and militia engaged in extensive looting and burning. "They looted all the animals and horses and opened all the shops and took what they could and burned the rest," said Hamed. Half the village was burned down and an estimated 160 shops were looted and burned.

Witnesses also reported to Human Rights Watch that militia and soldiers committed sexual violence during and after the attacks. For example, one witness said that while in hiding, he heard two soldiers attack his neighbor's daughter. "I saw two soldiers enter the house and then I heard her crying out," he said. The UN reported that the attackers raped at least 10 women and girls.[39]

Following the attack, the Sudanese military and Central Reserve Police deployed in the town. After several days the military reportedly ordered the Janjaweed out. Residents said the military and Central Reserve Police prevented the remaining population from leaving or those returning from their hiding places from collecting their belongings. By early April 2008, most of the population had returned.[40]

February 8, Silea

Silea, located 65 kilometers north of Al Geneina, is an important hub for access to Jebel Mun. It had a population of approximately 10,000, mostly from Erenga and Messeriya Jebel ethnic groups. Government aircraft flew over the town mid-afternoon on February 8 and dropped at least three bombs, one of which killed at least nine civilians according to several eyewitnesses who spoke to Human Rights Watch.[41]

Around 4 p.m., soldiers arrived in a column of military vehicles mounted with weapons, along with hundreds of Janjaweed, wearing green khaki and civilian clothes, riding horses and camels. Over the course of several days, the soldiers and militia shot at civilians, looted and burned shops and homes, and stole livestock and vehicles. They killed at least 20 civilians.

"The afternoon prayers had just begun and a lot of us men were in the mosque on the north side of town," recounted Adam, a 35-year-old man. "I heard the sound of the plane bombing and came out and saw military vehicles entering town. They were grey pickups mounted with doshkas. There were about 15 soldiers in each vehicle. We all scattered. I saw many dead bodies on the way out."[42]

Many of the reported attacks took place during robberies by soldiers or militia. Mariam, 35, described to Human Rights Watch how a large group of Janjaweed militia came to her house on four pickup trucks. When she resisted them, one shot her. The bullet hit her and killed the baby on her back. "They told me to leave and not to take anything, and then one of the men on a Toyota shot me, and I fell down." Her father found her bleeding and helped her to a safe place, then found a horse-cart to take her to the clinic at Birak, on the Chad border. "I was pregnant with twins and I lost them while we made the trip. I lost so much blood," she said.[43]

Ibrahim, 38, was hiding in the office of the International Committee of the Red Cross when men wearing military uniforms arrived in three military vehicles and on horses. "They came and beat down the door. We were in the safe room with a group of staff and civilians. We were scared," he recalled. While in the safe room, he and his colleagues listened to the assailants enter the premises, shoot one of their colleagues, and steal the contents of the storage room. "After a few hours some women came to the window and told us we could come out. We found our colleague dead. He was shot in the chest. We buried him and six other bodies near the hospital. Most of them were shot while fleeing. One was an 85-year-old man who was shot in the chest."[44]

The majority of bombing victims were women and children. Aisha, an 11-year-old girl, was hit by shrapnel, which required her left leg to be amputated above the knee. She told Human Rights Watch how it happened:

Planes and vehicles and horses and camels came. They bombed our neighbors and one part of the bomb fell on our house. The bomb killed 10 people, four women and six children. Our house caught fire and burned to the ground. A piece of the bomb fell on my leg. People came to rescue us that night. When I came to the hospital, the doctors decided to amputate.[45]

Hawa, 30, told Human Rights Watch that when a bomb fell near her house, her 5-year-old daughter was injured from shrapnel:

We heard the sound of bombing and then a bomb fell on our house and a piece of [shrapnel] fell on my daughter's hip. We were in the courtyard of our house. We all ran for cover but she was slower and fell down. She pulled herself into the house. Everyone fled in different directions. We came back for her two days later.[46]

Government soldiers deployed in town, while Janjaweed left nightly and returned each morning for several days and continued looting goods and supplies and burning shops and homes. They looted the offices of four nongovernmental organizations, dozens of vehicles, milling machines, generators, and even pried metal doors off their frames. They burned an estimated two-thirds of the town to the ground.

A significant military base in Silea has contributed to ongoing human rights violations.[47] Several women who ventured back to Silea after the attack to collect their belongings confirmed that government soldiers tried to prevent them from returning to Chad. Two government soldiers allegedly raped an 11-year-old girl on March 14. One soldier shot and killed three women after JEM rebels ambushed a military convoy between Silea and Goz Minu on March 18.

Most of Silea's population fled to Jebel Mun or Chad on the day of the attack. As of early April 2008, only 20 percent of the population was believed to be in Silea.[48]

February 18, 19, and 22, Jebel Mun

Ten days after establishing a military presence in the northern corridor, Sudanese government forces launched attacks on rebel positions and civilian centers at Jebel Mun. A Sudanese military spokesman at the time said the attacks were part of an effort to open the road from Al Geneina to Kulbus, some 100 kilometers north on the Chad border.[49]

Government forces and Janjaweed militia clashed with rebels from JEM and the Sudan Liberation Army (SLA) Abdel Wahid faction during the course of attacks.[50] Bombing began on rebel positions near Aro Sharow internally displaced persons (IDP) camp and Korlungo on February 18, which killed four civilians including a woman and an infant.[51] One civilian who fled to Chad that day told UNHCR staff that civilians counted 18 bombs, six of which fell on the IDP camp.[52]

At least 20 civilians were killed in the attacks. The main clashes occurred on February 19 and February 22, with most of the civilian casualties on February 19. The government used Antonov planes, other fixed-wing aircraft and three attack helicopters accompanied by approximately a hundred military vehicles carrying soldiers and at least a hundred Janjaweed militia wearing military uniforms, most riding horses. Eyewitnesses told Human Rights Watch that rebel forces held positions near civilian settlements, and had several vehicles and anti-aircraft artillery.

According to eyewitnesses, on the morning of February 19, an Antonov cargo plane flew surveillance over the area. Then at about 10 a.m. a convoy of government military vehicles stopped on the south side of the mountain and soldiers proceeded on foot with Janjaweed militia, while a smaller convoy drove into the mountain from the north entrance.

The aircraft included Antonovs, attack helicopters and jets. They bombed numerous villages in and around Jebel Mun. Area residents with whom Human Rights Watch spoke could not specify the locations of all bombings but consistently reported that Goz Minu, Sewani, Kendera, Koma, Nertiti, Saraf, Goz, Bot, Nurania, and smaller villages around the mountain were targeted by aircraft. Halima, a 40-year-old woman from Aro Sharow, saw her neighbor's house hit by a bomb. "We found seven people were killed, and we buried them. They were mostly old people and children," she told Human Rights Watch.[53]

Witnesses described ground forces arriving in the villages in cars and on horses and shooting indiscriminately and looting property, including livestock and food supplies in several villages.

"They came like flies, swarming here and there. They killed, beat and stole. They took all of our animals," said Fatna, 30, from the village of Gerda. She described the attackers as soldiers and militia from Arab and Gimir tribes. "We recognized them, we used to live near them," she said.

Mohamed, a 40-year-old farmer from Aro Sharow, told Human Rights Watch that the attackers shot people and burned houses:

They came and started to burn the village. Everyone fled, but the disabled could not leave. I saw them shoot at an old man and some children. I returned to the town the next day to bury the bodies. I found lots of burned bodies. I don't know how many. They were in the burned houses.[54]

The attackers shot civilians even as they were fleeing to safety. Kalthuma, 30, from Nokuna, a village of 200 households, told Human Rights Watch that while she and her family were fleeing, Janjaweed killed her baby and her father:

I had a small child on my back. [The attackers] followed us on their horses and shot at us as we fled to the trees. The bullet killed my baby boy. Some men took the baby off my back and buried it. Then we went under the trees and the Janjaweed shot at us again and killed my father.

Kalthuma said her uncle helped transport her to Birak, on the Chad side of the border.[55]

During the attack, government forces arrested 20 men from Aro Sharow, Goz Minu and other locations in the mountain and accused them of being rebels. One of those detained described to Human Rights Watch how authorities intercepted him as he was fleeing from Aro Sharow to Jebel Mun:

They took us back to Silea and we were beaten up badly. On our way, a Janjaweed recognized me and shouted, 'Are you a Torabora [derogatory term meaning "rebel"] now?' then shot at me.

He said security officials took the group to Al Geneina and El Fasher, interrogated them and accused them of being rebels. Authorities released the detainees after one month without charging them.[56]

Several villagers reported to Human Rights Watch that rebels had warned them of an impending attack. "On the morning of the attack, we heard the sound of helicopters and saw cars and Janjaweed coming. We fled thinking something was going to happen because the night before the SLA warned there would be an attack," said Yahyia, a 30-year-old man from Goz Minu village.[57]

Many witnesses and victims of the attack described to Human Rights Watch how they hid in mountain caves and behind boulders for several days without food before making their way to Chad after the fighting on February 22. Some said the attackers came looking for them in the caves.

UNHCR estimated 3,000 civilians crossed into Chad in the days following the attack on Jebel Mun.[58] As of this writing, only a few hundred civilians are believed to be living in the mountain. Some people who had escaped to Chad told Human Rights Watch they would not move to refugee camps further inside Chad because they planned to return to their villages for short periods to tend their crops.

Continuing insecurity in the border area

Most of the refugees who fled from the northern corridor and Jebel Mun settled in over a dozen sites over a 30-kilometer stretch of borderland in the Wadi Fira region of eastern Chad. Many refugees are situated in the town of Birak, located about 10 kilometers west of Jebel Mun, which has attracted armed rebels from Sudan and Chad who travel through the area and frequent Birak's market. The entire eastern portion of Wadi Fira is a "no man's land" with no Chadian government authority to uphold law and order.

As of mid-April 2008, the UNHCR had transferred more than 5,400 refugees to camps inside Chad, but an estimated 8,000 remained scattered along the border.[59] Many told Human Rights Watch and other agencies that they had decided to remain at the border in hopes of accessing their fields for cultivation.

Humanitarian agencies working along the border fear the mere presence of rebels from both Sudan and Chad could invite aerial bombings by either government, as they have done in the past year. Clashes between the government of Sudan and the JEM forces in West Darfur pose additional threats to refugees in Chad living close to the border.[60] There are indications the parties will continue to engage in hostilities, and with little regard for the safety of civilians. On March 19, JEM ambushed Sudanese army forces 65 kilometers north of Al Geneina, killing 19 soldiers.[61] On April 12 and 13, JEM and government clashed at Kishkish, northwest of Silea, injuring dozens of civilians and prompting humanitarian agencies to evacuate staff to Al Geneina.[62]

VI. Violations of International Humanitarian Law

Applicable Standards of International Humanitarian Law

International humanitarian law (the laws of war) imposes legal obligations on parties to an armed conflict to reduce unnecessary suffering and protect civilians and other non-combatants. It applies to all armed conflicts, whether belligerents are regular armies or non-state armed groups. All parties to the conflict in Darfur-Sudanese government forces, Janjaweed militia, and rebel factions-are bound by it.

Under international law, the Darfur conflict is considered a non-international (internal) armed conflict, in which the applicable law derives primarily from article 3 common to the four Geneva Conventions of 1949, the Second Additional Protocol of 1977 to the Geneva Conventions (Protocol II) and customary international law.

In 2006 Sudan ratified Protocol II, which specifically applies to internal armed conflicts between government forces and non-state armed groups.[63] The protocol includes many basic civilian protection principles, such as the prohibition on attacks against civilians. It states that acts or threats of violence designed to spread terror among the civilian population are prohibited.[64] It prohibits starvation as a method of conflict and protects from destruction or removal objects "indispensable to the survival of the civilian population" such as food, crops, livestock, and water supplies.[65] The forced displacement of the civilian population is prohibited unless it is for the security of the civilians involved or is required for imperative military reasons; in such situations all possible measures need to be taken to address the basic needs of the civilian population.[66] Parties to the conflict must facilitate rapid and unimpeded passage of independent humanitarian relief for civilians in need.[67]

Although the First Additional Protocol of 1977 to the Geneva Conventions (Protocol I) only applies during international armed conflict,[68] most of its provisions on the conduct of hostilities have been recognized by states to be reflective of customary international law.[69]

The "principle of distinction" is the foundation of the law regulating conduct of hostilities. It requires all parties to a conflict to distinguish at all times between combatants and civilians. Military operations shall only be directed against military objectives.[70] Deliberate attacks on civilians and civilian objects are prohibited. "Military objectives" are members of the armed forces, other persons taking a direct part in hostilities for the duration of their participation, and "objects which by their nature, location, purpose or use make an effective contribution to military action and whose total or partial destruction, capture or neutralization, in the circumstances ruling at the time, offers a definite military advantage."[71] "Civilian objects" include all objects-such as houses, farms, schools, shelters, hospitals, and places of worship-that are not being used for military purposes.

Humanitarian law also prohibits indiscriminate attacks,that is, attacks "of a nature to strike military objectives and civilians or civilian objects without distinction."[72] Indiscriminate attacks include those that "are not directed at a specific military objective" or that use weapons that "cannot be directed at a specific military objective."[73] Also prohibited are disproportionate attacks, which are attacks that are "expected to cause incidental loss of civilian life, injury to civilians [or] damage to civilian objectives … which would be excessive in relation to the concrete and direct military advantage anticipated" from that attack.[74]

The parties to a conflict must take precautionary measures to minimize incidental loss of civilian life, injury to civilians, and damage to civilian objects. These precautions include:

- Doing everything feasible to verify that targets are military objectives and not civilians or civilian objects;

- Taking all feasible precautions in the choice of means and methods of warfare so as to avoid and in any event minimize civilian loss and damage to civilian objects;

- When circumstances permit, giving effective advance warning of attacks that may affect the civilian population;

- Avoiding locating military objectives within or near densely populated areas;

- Endeavoring to remove civilians from the vicinity of military objectives.[75]

With regard to civilians and captured combatants, parties to the conflict are prohibited from using violence to life and person, in particular murder, mutilation, or cruel and degrading treatment. No party may pass sentences or carry out executions without previous judgment by a regularly constituted court that has afforded the defendant all judicial guarantees.[76] International humanitarian law also prohibits rape and other forms of sexual violence, enforced disappearances, arbitrary deprivation of liberty, and collective punishments.[77]

Government Violations in the West Darfur Attacks

The attacks by government armed forces and government-backed Janjaweed militia in West Darfur in February 2008 involved numerous serious violations of international humanitarian law. When committed with criminal intent-that is, purposefully or recklessly-such violations amount to war crimes.

Except for the attack on Jebel Mun, there was no apparent rebel military presence in any of the towns that came under direct government attack. The government's aerial bombings and ground attacks reflected, at a minimum, a failure to identify a military objective before conducting attacks. However, the repeated attacks in which there were no rebels or other evident military objective, as well as situations in which it was apparent that those attacked were civilians, indicates that the Sudanese armed forces carried out deliberate attacks on civilians and the civilian population.

Even had there been a rebel military presence in the towns, many attacks were clearly indiscriminate. Bombs were rolled out of the back of cargo aircraft to fall haphazardly on the town.[78] Attack helicopters fired rockets seemingly randomly into populated neighborhoods, setting numerous homes on fire. Government troops and Janjaweed fired rocket launchers, rocket-propelled grenades and firearms into densely populated areas.

In the attack on Jebel Mun, where rebel forces were deployed, the Sudanese air and ground forces used force indiscriminately and at times they deliberately targeted civilians. There were reports that government forces mistreated persons taken into custody in and around Jebel Mun.

The February attacks in West Darfur also violated international humanitarian law on the protection of the civilian population. Government forces repeatedly pillaged large amounts of food intended for civilians, stole thousands of livestock, looted extensively from shops and homes, and burned numerous homes, including significant percentages of towns. To the extent the government attacks were carried out to punish civilian populations for any perceived support of the rebels, they violated the prohibitions on attacks whose primary purpose was to spread terror among the civilian population, caused unlawful forced displacement, and were a form of collective punishment. Finally, any unjustified government interference with UN or other independent agencies who were seeking to provide humanitarian relief for civilians in need was a violation of humanitarian law.

Criminal responsibility

States and non-state armed groups are responsible for violations of international humanitarian law. Individuals who order or commit serious violations of international humanitarian law with criminal intent can be prosecuted for war crimes before national or international courts. Civilian or military officials who knew or should have known of such violations but took no action to prevent the crimes or punish the perpetrators may be held liable as a matter of command responsibility. International law also allows prosecution of individuals for crimes against humanity, which are unlawful acts that are committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack (whether during a conflict or during peace) against a specific civilian population.[79]

The Sudanese government is responsible for crimes in violation of international law committed by its soldiers and by armed groups over which it exercises "overall control." Links between the government armed forces and Janjaweed militia have been well-documented since early 2004.[80] In recent years, the government has integrated militias into auxiliary units of the army and police forces such as the Border Guards Unit.[81] The government of Sudan, even as it claims Janjaweed do not exist, acknowledges that military authorities have control over them. When a large militia force attacked three towns in North Darfur in early April 2008, killing about 14 civilians and looting and destroying shops in protest over the government's failure to pay their salaries, the provincial governor referred to the attackers as "Janjaweed" and gave assurances that military and border guard leaders would resolve the problem.[82]

The West Darfur attacks were carried out by Sudanese military, working in concert with Janjaweed militia. Scores of eyewitnesses told Human Rights Watch that Janjaweed militia dressed in military-style uniforms and bearing light arms arrived before or with government soldiers, and that militia and government soldiers carried out the attacks together. Government military officials who were present in the area during the attacks were seen allowing large-scale looting by Janjaweed. Eyewitness descriptions of attackers' uniforms suggest that government soldiers also participated directly in the pillage and looting, using military vehicles to transport stolen goods.

According to residents of the attacked towns, Janjaweed involved in the attacks were drawn largely from Arab ethnicities from North and West Darfur and included some Gimir and Tama fighters who arrived from the Kulbus area. Eyewitnesses told Human Rights Watch they saw a number of well-known militia commanders, including Diggi Idriss Ajina, Hassan Algoni Bakheet, Ahmed Abu Gurun, and Mustafa Issa Idriss ("Takizo") at the site of the attack. Some of these commanders are known members of the Border Guard Unit of the Sudanese army.

VII. International responses to the February attacks

International responses to the February attacks have not helped to improve the safety of tens of thousands of civilians at risk, and remain insufficient to protect civilians who remained or returned to the northern corridor and Jebel Mun. UNAMID's mandate includes "protection of civilian populations under imminent threat of physical violence and prevent attacks against civilians, within its capability and areas of deployment, without prejudice to the responsibility of the Government of Sudan."[83] On February 8, 2008, UNAMID officials urged the parties to the conflict to cease hostilities and show restraint.[84] Two weeks later, after receiving news of aerial bombing in Jebel Mun, UNAMID called on the government and rebels to allow civilians to leave safely.[85]

However, the international peacekeepers have not physically intervened to protect civilians by, for example, creating humanitarian corridors to help civilians in Jebel Mun reach safety. UNAMID authorities have stated the mission lacked the sufficient resources to be effective.[86] Five months after UNAMID took over the mandate of the African Union's peacekeeping mission on January 1, 2008, it has received just over one-third of its authorized 26,000 personnel and still lacks key equipment such as helicopters and transportation units. The Sudanese government has also obstructed the mission by objecting to the inclusion of non-African troops and delaying allocation of land resources for UNAMID bases.

Following the February attacks, UNAMID and aid agencies accessed Abu Suruj, Sirba, and Silea and agencies provided humanitarian assistance to civilians who stayed or returned. Ongoing fighting between government and rebel forces near Jebel Mun prevented the agencies from reaching civilians who may have stayed or have since returned.[87] The continuing insecurity around Jebel Mun underscores the urgent need for peacekeepers to access and patrol that area. The closest UNAMID base is at Kulbus, about 50 kilometers away. Although UNAMID is able to send ground patrols to the northern corridor from Kulbus and Al Geneina, a permanent base in Silea would enable the peacekeepers to patrol areas closer to Jebel Mun where civilians remain vulnerable to attack.[88]

In March 2008, based on the work of UNAMID human rights monitors, OHCHR issued a report documenting the government's violations of international humanitarian and human rights law in attacks on civilians in Saraf Jidad, Abu Suruj, Sirba and Silea in January and February. The report urged all parties to the conflict to take specific actions to end international law violations.[89] To date, Sudan has not acknowledged any wrongdoing or taken steps to promote accountability for serious international crimes its forces committed against civilians. It continues to disregard its obligations under international law and those set out in numerous UN Security Council resolutions.

Meanwhile, the UN has taken no meaningful action against Sudan. UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon condemned the February 8, 2008 attacks in "the strongest possible terms" and said the government's bombing of Aro Sharow IDP camp was unacceptable.[90] The UN Security Council expressed its concern over the security and humanitarian situation in West Darfur in a press statement.[91] But it stopped short of a presidential statement condemning the attacks or imposing targeted sanctions on those responsible.[92]

To comprehensively address Sudan's disregard for its international obligations, the UN Security Council should establish and monitor a set of benchmarks applicable to all parties to the conflict. The benchmarks should include ending attacks on civilians and offensive military over-flights, ending support to Janjaweed militia, facilitating UNAMID deployment and freedom of movement, and promoting accountability in meaningful ways. Crucially, UN member states should ensure UNAMID has appropriately trained and equipped troops with all necessary equipment and logistical support needed to respond rapidly and effectively to civilian protection threats.

[1] The Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) and the Sudan Liberation Army (SLA) faction led by Abdel Wahid Mohamed el-Nur both have forces in Jebel Mun.

[2] For the purposes of this report, "Janjaweed" and "government-supported militia" both refer to civilians who were armed by the government and continue to fight with government support either informally or formally as members of auxiliary units (such as the Border Intelligence unit or the Popular Defense Forces) within the Sudanese military. These terms do not refer to regular security services such as police, Sudanese Armed Forces or the National Intelligence and Security Service.

[3] Armed militia attacked Aro Sharrow internally displaced persons (IDP) camp, located southwest of the mountain, in September 2005, killing about 27 civilians. Militia with support from government forces again attacked Jebel Mun in October 2006, leading to about 50 civilian deaths. See Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), "Sixth Periodic Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on the situation of human rights in the Sudan: Attack on Villages around the Jebel Moon Area," Geneva, November 3, 2006, http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Countries/6thOHCHR5nov06.pdf (accessed May 9, 2008).

In November 2006, government forces attacked Sirba, destroying property and killing 11 civilians. The Panel of Experts report describes this and several other examples of attacks on civilians in 2006 to 2007. United Nations (UN) Panel of Experts, "Report of the Panel of Experts," S/2007/584, October 3, 2007, http://daccessdds.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N07/491/00/PDF/N0749100.pdf?OpenElement (accessed May 9, 2008). Smaller scale attacks have also occurred on Silea, Sirba and Abu Suruj. See OHCHR, "Ninth Periodic Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on the Situation of Human Rights in the Sudan: Attacks on civilians in Saraf Jidad, Sirba, Silea and Abu Suruj in January and February 2008," March 20, 2008, http://www2.ohchr.org/SPdocs/Countries/9thOHCHR20mar08.pdf (accessed April 22, 2008), p. 3.

[4] Human Rights Watch, Darfur – Chaos by Design: Peacekeeping Challenges for AMIS and UNAMID, vol. 19, no. 15(A), September 2007, http://hrw.org/reports/2007/sudan0907/, p. 46.

[5] See, e.g., the Panel of Experts description of the 2006 attack on Hilef, North Darfur. UN Panel of Experts, "Report of the Panel of Experts," October 3, 2007, para. 279.

[6] OHCHR, "Ninth Periodic Report," March 20, 2008, p. 3.

[7] "Rebel JEM leader threatens to attack Darfur capital," Sudan Tribune, December 27, 2007, http://www.sudantribune.com/spip.php?article25259 (accessed May 9, 2008). For the sequence of events, see JEM's press releases claiming military victory over several towns at http://www.sudanjem.com/en/index.php.

[8] OHCHR, "Ninth Periodic Report," March 20, 2008, p. 3.

[9] Human Rights Watch interview (name withheld), Guereda area, Chad, March 15, 2008; OHCHR, "Ninth Periodic Report," March 20, 2008, p. 3 (describing an attack resulting in death and injuries to members of security forces and civilians).

[10] Residents of Saraf Jidad told the UN that JEM never maintained a presence inside the village. OHCHR, "Ninth Periodic Report," March 20, 2008, p. 3. Refugees in Chad who fled from Silea told Human Rights Watch that JEM came to Silea in 13 camouflage cars and left after about a week. Human Rights Watch interviews (names withheld), Kounoungu refugee camp and Guereda, Chad, March 15-16, 2008.

[11] OHCHR, "Ninth Periodic Report," March 20, 2008, p. 3

[12] Human Rights Watch interview with community leaders (names withheld), March 25, 2008.

[13] Human Rights Watch interview with community leaders (names withheld), March 25, 2008.

[14] OHCHR, "Ninth Periodic Report," March 20, 2008, pp. 4-5.

[15] Agencies accessed Saraf Jidad on February 3 and Sirba, Abu Suruj and Silea on February 11, 12, and 14, respectively. Ibid. pp. 3-4. UN agencies visited the northern corridor town of Sirba on February 21, 2008. "Interview with UN Humanitarian Coordinator in Sudan, Ameerah Haq, during her visit to Sirba," UN News, February 22, 2008, http://unamid.unmissions.org/Default.aspx?tabid=55&ctl=Details&mid=376&ItemID=86 (accessed May 9, 2008).

[16] UN Security Council, "Report of the Secretary-General on the deployment of the African Union-United Nations Hybrid Operation in Darfur," S/2008/249, April 14, 2008, http://daccessdds.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N08/295/03/PDF/N0829503.pdf?OpenElement (accessed May 9, 2008), para. 14.

[17] For background on the Chad-Sudan proxy war, see Jérôme Tubiana,"The Chad-Sudan Proxy War and the 'Darfurization' of Chad: Myths and Reality," Small Arms Survey, HSBA Working Paper 12, April 2008.

[18]"Chad says Sudan broke peace pact, Khartoum denies," Reuters, April 1, 2008, http://www.alertnet.org/thenews/newsdesk/L01742572.htm (accessed May 5, 2008).

[19] UN Security Council, "Report of the Secretary-General on the deployment of the African Union-United Nations hybrid operation in Darfur," S/2008/98, February 14, 2008, http://daccessdds.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N08/235/84/PDF/N0823584.pdf?OpenElement (accessed May 4, 2008) para. 3-4; "Sudan accuses Chad of three territory violations," Reuters, April 2, 2008, http://www.alertnet.org/thenews/newsdesk/L02884232.htm (accessed May 4, 2008).

[20] UN Security Council, "Report of the Secretary-General," February 14, 2008, para. 3.

[21] Jérôme Tubiana,"The Chad-Sudan Proxy War and the 'Darfurization' of Chad," Small Arms Survey, April 2008, p. 12.

[22] Human Rights Watch documented many of these earlier attacks in previous reports. See, e.g., Entrenching Impunity: Government Responsibility for International Crimes in Darfur, vol. 17, no. 17(A), December 2005, http://hrw.org/reports/2005/darfur1205/; Targeting the Fur: Mass Killings in Darfur, January 21, 2005, http://hrw.org/backgrounder/africa/darfur0105/; "If We Return We Will Be Killed": Consolidation of Ethnic Cleansing in Darfur, Sudan, November 2004, http://hrw.org/backgrounder/africa/darfur1104/; Empty Promises?: Continuing Abuses in Darfur, Sudan," August 11, 2004, http://hrw.org/backgrounder/africa/sudan/2004/sudan0804.pdf; Darfur Destroyed: Ethnic Cleansing by Government and Militia Forces in Western Sudan, vol. 16, no. 6(A), May 2004, http://hrw.org/reports/2004/sudan0504/; Darfur in Flames: Atrocities in Western Sudan, vol. 16, no. 5(A), April 2004, http://hrw.org/reports/2004/sudan0404/.

[23]The non-signatory factions include JEM and the SLA factions headed by Abdel Wahid Mohamed el-Nur.

[24] UN Panel of Experts, "Report of the Panel of Experts established pursuant to resolution 1591 (2005) concerning the Sudan prepared in accordance with paragraph 2 of resolution 1713 (2006)," S/2007/584, October 3, 2007, http://daccessdds.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N07/491/00/PDF/N0749100.pdf?OpenElement (accessed May 5, 2008), para. 281-286.

[25] Ibid., para. 318-323.

[26] "Sudanese army bombs Darfur rebels' areas: SLA-Unity," Sudan Tribune, April 1, 2008, http://www.sudantribune.com/spip.php?article26586 (accessed May 2, 2008). Human Rights Watch verified the report in an interview with an UNAMID source (name withheld), April 10, 2008.

[27] "Sudan bombs Darfur school and market, 13 killed," Reuters, May 5, 2008, http://www.alertnet.org/thenews/newsdesk/MCD561339.htm (accessed May 5, 2008).

[28] The UN reported the government used 130 vehicles. Witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch were not able to confirm that number. UN Security Council, "Report of the Secretary-General on the deployment of the African Union-United Nations Hybrid Operation in Darfur," S/2008/196, March 25, 2008, http://daccess-ods.un.org/TMP/8996025.html (accessed April 24, 2008).

[29] There are discrepancies in casualty figures reported by UN sources. The numbers cited here and throughout represent Human Rights Watch's best estimation based on a range of published and non-published sources.

[30] Human Rights Watch interview, Birak, eastern Chad, March 17, 2008.

[31] Human Rights Watch interview, Birak, eastern Chad, March 18, 2008.

[32] Human Rights Watch interview, Birak, eastern Chad, March 18, 2008.

[33] OHCHR, "Ninth Periodic Report," March 20, 2008, p. 5

[34] US Agency for International Development (USAID), "Sudan Complex Emergency," USAID Situation Report #5, April 4, 2008, http://www.usaid.gov/our_work/humanitarian_assistance/disaster_assistance/countries/sudan/template/fs_sr/sudan_ce_sr05_04-04-2008.pdf (accessed May 5, 2008).

[35] Human Rights Watch interview, Guereda area, Chad, March 19, 2008.

[36] Human Rights Watch interview, Birak, eastern Chad, March 17, 2008.

[37] Human Rights Watch interview, Birak, eastern Chad, March 18, 2008.

[38] Human Rights Watch interview, Birak, eastern Chad, March 17, 2008.

[39] OHCHR, "Ninth Periodic Report," March 20, 2008, p. 6

[40] USAID, "Sudan Complex Emergency," April 4, 2008.

[41] Witnesses said another bomb resulted in 10 deaths, but Human Rights Watch could not independently confirm the number of casualties caused by each bombing. Residents of Silea who fled to Chad provided Human Rights Watch the estimate of the total number of civilian casualties from the attack.

[42] Human Rights Watch interview, Guereda area, Chad, March 15, 2008.

[43] Human Rights Watch interview, Guereda area, Chad, March 15, 2008.

[44] Human Rights Watch interview, Birak, eastern Chad, March 18, 2008.

[45] Human Rights Watch interview, Guereda, Chad, March 16, 2008.

[46] Human Rights Watch interview, Guereda area, Chad, March 15, 2008.

[47] UN Security Council, "Report of Secretary-General on the deployment of the African Union-United Nations Hybrid Operation in Darfur," March 25, 2008, para.7.

[48] USAID, "Sudan Complex Emergency," April 4, 2008.

[49] "Rebels claim downing Sudanese helicopters in Darfur attacks," Sudan Tribune, February 20, 2008, http://www.sudantribune.com/spip.php?article26056(accessed May 5, 2008).

[50] Both JEM and the SLA faction led by Abdel Wahid were present and had vehicles and weapons including anti-aircraft weapons.

[51] "Four killed during Sudan air strike in Darfur's Jebel Moun," Sudan Tribune, February 19, 2008, http://www.sudantribune.com/spip.php?article26033&var_recharche=jebel%20mun (accessed May 9, 2008); UN Security Council, "Report of the Secretary-General on the deployment of the African Union-United Nations Hybrid Operation in Darfur," March 25, 2008, para. 5.

[52]Annette Rehrl, "UNHCR recalls staff from Chad border after air strikes in Darfur," February 19, 2008, http://www.unhcr.org/cgi-bin/texis/vtx/chad?page=news&id=47bb1a192 (accessed May 5, 2008).

[53] Human Rights Watch interview, Birak area, eastern Chad, March 17, 2008.

[54] Human Rights Watch interview, Birak area, eastern Chad, March 18, 2008.

[55] Human Rights Watch interview, Guereda, Chad, March 16, 2008.

[56] Human Rights Watch telephone interview (name withheld), April, 2008.

[57] Human Rights Watch interview, Birak, eastern Chad, March 18, 2008.

[58] UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), "Chad: Arrivals from West Darfur continue," UNHCR Briefing Notes, February 29, 2008, http://www.unhcr.org/news/NEWS/47c7f20a4.html (accessed April 24, 2008).

[59] UNHCR, "Chad/Darfur: Continuing Insecurity," UNHCR Briefing Notes, April 18, 2008, http://www.unhcr.org/news/NEWS/4808717c4.html (accessed April 24, 2008).

[60] At Sineit, a small settlement on the Chad side of the border just a few kilometers from Jebel Mun, the sounds of ongoing fighting prompt refugees to remove reflective cookware from the roofs of their shelters to avoid being mistaken for combatants and targeted by aircraft that residents said regularly patrolled the area. Human Rights Watch visit, Sineit, Chad, March 17, 2008.

[61] UN Security Council, "Report of the Secretary-General on the deployment of the African Union-United Nations Hybrid Operation in Darfur," April 14, 2008, para. 3.

[62] Opheera McDoom, "Clashes in Darfur, protests mark five years of war," Reuters, April 13, 2008, http://www.alertnet.org/thenews/newsdesk/L1395282.htm (accessed April 24, 2008); "UNAMID condemns fighting in West Darfur," Sudan Tribune, April 13, 2008, http://www.sudantribune.com/spip.php?article26744&var_recherche=SLA-Unity (access April 24, 2008).

[63] Protocol Addition to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and Relating to the Protection of Victims of Non-International Armed Conflicts (Protocol II), 1125 U.N.T.S. 609, entered into force December 7, 1978. Article 1 states the protocol applies to "dissident armed forces or other organized armed groups which, under responsible command, exercise such control over a part of its territory as to enable them to carry out sustained and concerted military operations and to implement this Protocol."

[64] Protocol II, art. 13(2).

[65] Ibid., art. 14.

[66] Ibid., art. 17.

[67] Ibid., art. 18.

[68]Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and Relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts (Protocol I), adopted June 8, 1977, 1125 U.N.T.S. 3, entered into force December 7, 1978.

[69]See, e.g. Yorem Dinstein, The Conduct of Hostilities under the Law of International Armed Conflict (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), pp. 10-11. The "Hague Convention (IV) of 1907 has acquired over the years the lineaments of customary international law" and "[m]uch of the Protocol may be regarded as declaratory of customary international law, or at least as non-controversial." See generally, International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), Customary International Humanitarian Law (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005).

[70]Protocol I, art. 48.

[71]Ibid., arts. 51(3), 52

[72]Ibid., art. 51(4).

[73]Ibid., art. 51(4)(a,b).

[74]Ibid., art. 51(5)(b).

[75]See ibid., arts. 57, 58; ICRC, Customary International Humanitarian Law, rules 15-24.

[76] Common article 3; Protocol II, art. 4.

[77] Protocol II, art. 4.

[78] Human Rights Watch, Chaos by Design, pp. 36-37.

[79] Examples of crimes against humanity include murder, extermination, enslavement, deportation, arbitrary detention, torture, rape, persecution on political, racial and religious grounds, and other inhumane acts.

[80] See past Human Rights Watch reports on Darfur and the "Report of the International Commission of Inquiry on Darfur to the United Nations Secretary General," January 25, 2005, http://www.un.org/News/dh/sudan/com_inq_darfur.pdf (accessed April 24, 2008).

[81] See, e.g., International Crisis Group, "Darfur's New Security Reality," Africa Report, vol. 134, November 26, 2007, p. 9.

[82] "14 Killed during Janjaweed attacks in three towns – Darfur rebels," Sudan Tribune, April 8, 2008, http://www.sudantribune.com/spip.php?article26680 (accessed April 24, 2008).

[83] See UNAMID mandate documents, http://www.un.org/Depts/dpko/missions/unamid/mandate.html (accessed May 9, 2008).

[84] "UNAMID Force Commander expressed concern over reports of attacks in West Darfur," UN News, February 8, 2008, http://unamid.unmissions.org/Default.aspx?tabid=55&ctl=Details&mid=376&ItemID=74 (accessed May 4, 2008) and "UN-AU Joint Special Representative concerned over ongoing military activity in West Darfur," UN News, February 9, 2008, http://unamid.unmissions.org/Default.aspx?tabid=55&ctl=Details&mid=376&ItemID=81 (accessed May 4, 2008).

[85] "Statement by JSR Adada and UN Humanitarian Coordinator Ameerah Haq," UN News, February 24, 2008, http://unamid.unmissions.org/Default.aspx?tabid=56&ctl=Details&mid=393&ItemID=91 (accessed May 4, 2008).

[86] See, e.g., "Thousands of Darfur refugees trapped by fighting," CNN, February 20, 2008, http://www.cnn.com/2008/WORLD/africa/02/20/darfur.fighting.ap/index.html (accessed April 6, 2008).

[87] UNAMID visited Goz Minu briefly on March 9, 2008, but nearby clashes between government and the JEM prompted them to return.

[88] UN Security Council, "Report of the Secretary-General on the deployment of the African Union-United Nations Hybrid Operation in Darfur," April 14, 2008, para. 8.

[89] OHCHR, "Ninth Periodic Report," March 20, 2008.

[90] Office of the Secretary-General, "Secretary-General condemns in strongest possible terms Friday's attacks on West Darfur civilians, reported to have included air strikes by government forces," SG/SM/11406-AFR/1655, February 11, 2008, http://www.un.org/News/Press/docs/2008/sgsm11406.doc.htm and Office of the Secretary-General, "Secretary-General extremely concerned by renewed violence in West Darfur," SG/SM/11431-AFR/1660, February 19, 2008, http://www.un.org/News/Press/docs/2008/sgsm11431.doc.htm (accessed May 4, 2008)

[91]UN Security Council, "UN Security Council Press Statement on Darfur," SC/9272-AFR/1667, March 11, 2008, http://www.un.org/News/Press/docs/2008/sc9272.doc.htm (accessed May 4, 2008)

[92] Human Rights Watch called on the UN Security Council to take these steps shortly after the attacks. Letter from Human Rights Watch to the UN Security Council, "Security Council: Condemn Attacks in West Darfur," February 27, 2008, http://hrw.org/english/docs/2008/02/27/sudan18168.htm.