Map: Administrative Divisions of Lebanon

2006 UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs

Map: Southern Lebanon

2007 John Emerson

Map: Northern Lebanon

2007 John Emerson

I. Executive Summary

In this report, Human Rights Watch examines military operations by Israeli and Hezbollah forces in Lebanon during the armed conflict that lasted from July 12 until August 14, 2006. Human Rights Watch issued an earlier report on the conflict, researched and published while the war was ongoing. Because of our concerns about the conduct of that conflict by both sides and the difficulty of doing research in the midst of the fighting, Human Rights Watch conducted substantial additional research in the less difficult post-war environment.

According to this new research, the conflict resulted in at least 1,109 Lebanese deaths, the vast majority of whom were civilians, 4,399 injured, and an estimated 1 million displaced. Hezbollah's indiscriminate rocket attacks on Israel, the subject of a separate Human Rights Watch report, Civilians under Assault: Hezbollah's Rocket Attacks on Israel during the 2006 War, resulted in the deaths of 43 Israeli civilians and 12 Israel Defense Forces (IDF) soldiers, as well as the wounding of hundreds of Israeli civilians.

Israeli warplanes launched some 7,000 bomb and missile strikes in Lebanon, which were supplemented by numerous artillery attacks and naval bombardment.[1] Israeli airstrikes destroyed or damaged tens of thousands of homes. In some villages, homes completely destroyed by Israeli forces numbered in the hundreds: 340 homes completely destroyed in Srifa; 215 homes completely destroyed in Siddiquine; 180 homes completely destroyed in Yatar; 160 homes completely destroyed in Zebqine; more than 750 homes completely destroyed in `Aita al-Sha`ab; more than 800 homes completely destroyed in Bint Jbeil; and 140 homes completely destroyed in Taibe. The list throughout southern Lebanon is extensive.

This report seeks to answer three central questions:

Were the Lebanese who died in Israeli air strikes civilians or combatants?;

Did Israel abide by international humanitarian law (the laws of war) in its attacks in Lebanon?; and,

To what extent did Hezbollah's actions contribute to the civilian death toll inside Lebanon?

To answer these three questions, Human Rights Watch investigated over 94 separate incidents of IDF air, artillery, and ground attacks that claimed 510 civilian lives and those of 51 Hezbollah combatants, or almost half of the Lebanese deaths in the conflict.

Our research shows that the primary reason for the high Lebanese civilian death toll was Israel's frequent failure to abide by a fundamental obligation of the laws of war: the duty to distinguish between military targets, which can be legitimately attacked, and civilians, who are not subject to attack. This was compounded by Israel's failure to take adequate safeguards to prevent civilian casualties.

The occurrence of civilian casualties does not necessarily mean that there has been a violation of international humanitarian law, but it is a starting point for investigations. Human Rights Watch's extensive field investigations in Lebanon found that Israel often attacked targets that, under the laws of war, could not be considered military objectives subject to attack. In cases where a legitimate military objective was evident, our investigations frequently found that the civilian loss incurred may have been excessive compared to the anticipated military gain from the attack. In critical respects, Israel conducted the war with reckless indifference to the fate of Lebanese civilians and violated the laws of war.

Israeli officials contend that the reason for the high fatality rate was not indiscriminate targeting by Israeli forces, but the Hezbollah military's allegedly routine practice of hiding among civilians and using them as "shields" in the fighting. If Israeli attacks on Hezbollah forces also killed civilians and destroyed civilian homes, Israeli officials have argued, the blame lies with Hezbollah. The evidence Human Rights Watch uncovered in its on-the-ground investigations refutes this argument.

Hezbollah at times violated the laws of war in its deployment of forces in Lebanon. It also frequently violated the laws of war in its rocket attacks on Israel, which is the subject of a separate Human Rights Watch report, Civilians under Assault. On some occasions, our research shows, Hezbollah fired rockets from within populated areas, allowed its combatants to mix with the Lebanese civilian population, or stored weapons in populated civilian areas in ways that violated international humanitarian law. Such violations, however, were not widespread: we found strong evidence that Hezbollah stored most of its rockets in bunkers and weapon storage facilities located in uninhabited fields and valleys, that in the vast majority of cases Hezbollah fighters left populated civilian areas as soon as the fighting started, and that Hezbollah fired the vast majority of its rockets from pre-prepared positions outside villages. On the question of whether Hezbollah intentionally used civilians as "shields"-that is, whether Hezbollah forces not only endangered civilians in violation of the duty to take all feasible precautions to spare civilians the hazards of armed conflict but also deliberately deployed among civilians with the aim of protecting themselves from attack-a serious laws of war violation, we found a handful of instances but nothing to suggest a widespread practice.

For the reasons set forth below, Human Rights Watch's assessment of Hezbollah's practices does not support the Israeli contention that Hezbollah violations were the principal cause of Lebanese civilian casualties. Responsibility for the high civilian death toll of the war in Lebanon lies squarely with Israeli policies and targeting decisions in the conduct of its military operations.

Israeli Policies Contributing to the Civilian Death Toll

In the vast majority of cases documented in this report, Israeli air strikes hit near or on civilian objects, killing numerous civilians in their homes or vehicles. While there were instances in which civilian deaths were "collateral damage" from legitimate attacks on military targets, during the vast majority of the deadly air strikes we investigated, we found no evidence of Hezbollah military presence, weaponry or any other military objective that would have justified the strike. Human Rights Watch visits to the graveyards in the villages found that the victims of these strikes were buried as civilians, and not honored as "fighters" or "martyrs" by Hezbollah or other militant groups, despite the pride that Hezbollah takes in these labels. Women and children account for a large majority of the victims of Israeli air strikes that we documented. Out of the 499 Lebanese civilian casualties of whom Human Rights Watch was able to confirm the age and gender, 302 were women or children.

This repeated failure to distinguish between civilians and combatants cannot be explained as mere mismanagement of the war or a collection of mistakes. Our case studies show that Israeli policy was primarily responsible for this deadly failure. Israel assumed that all Lebanese civilians had observed its warnings to evacuate villages south of the Litani River, and thus that anyone who remained was a combatant. Reflecting that assumption, it labeled any visible person, or movement of persons or vehicles south of the LitaniRiver or in the Beka` Valley as a Hezbollah military operation which could be targeted. Similarly, it carried out widespread bombardment of southern Lebanon, including the massive use of cluster munitions prior to the expected ceasefire, in a manner that did not discriminate between military objectives and civilians.

During the war, Israel repeatedly sent warnings to the population in southern Lebanon to evacuate the area south of the LitaniRiver. It issued such warnings by Arabic-language flyers dropped from airplanes, Arabic radio messages broadcast into southern Lebanon, recorded voice messages sent to some Lebanese cellphones, and loudspeakers along the Israel-Lebanese border. Following the release of the messages, many Israeli officials made statements (see below) suggesting that everyone who remained behind was linked to Hezbollah, and therefore a legitimate target of attack. In subsequent days and weeks, Israel intensified its bombardment of southern Lebanon, hitting thousands of homes in the south.

It is questionable whether Israeli officials really believed the assumption that there were no Lebanese civilians left in southern Lebanon, or simply announced this to defend their actions. Certainly, there is evidence to suggest that Israeli officials knew that their assumption was erroneous. At the time of the Israeli attacks in southern Lebanon, stories about Lebanese civilians dying in Israeli strikes or trapped in southern Lebanon filled the Israeli and international media. In addition, foreign embassies were in regular contact with Israeli diplomats to request assistance with the evacuation of their nationals caught in the fighting in the south. And in some instances, Israel seemed to know exactly how many people remained in a village. For instance, on July 24, Dan Halutz, the IDF chief of staff, estimated that 500 residents remained in Bint Jbeil despite IDF warnings to leave.[2]

In addition, Israel must have known from its past conflicts in southern Lebanon that a civilian population is rarely willing or able to leave its homes according to timetables laid down by a belligerent military force.[3] Reporting 10 years ago on fighting between Hezbollah and Israel during July 1993, Human Rights Watch found that it was "reasonably foreseeable that a segment of the population might not flee, and it was entirely foreseeable that in particular the old and indigent would not be able to evacuate their homes, especially considering the brevity of time between the first warnings and the beginning of the shelling."[4] As in 1993, many elderly and indigent people were among the casualties in the 2006 war. Israel should have known that significant numbers of civilians would remain in their villages throughout the war. At the very least, Israeli forces had a duty to check the areas they were targeting, especially after it became clear that civilians were dying in very high numbers.

Even if those who remained did so out of support for Hezbollah-a claim that Human Rights Watch's research disproves, as most who remained behind stayed because they were too old, poor, or sickly to leave-Israel would not have been justified in attacking them. The political leanings of the civilian population in a given area or village is irrelevant as far as their civilian status is concerned. To the extent that civilians do not directly participate in hostilities, that is, are not committing acts that by their nature or purpose are likely to contribute to harming the personnel and equipment of the enemy, they continue to benefit from the protection afforded by their civilian status under international humanitarian law. Thus attacks directed against civilians who support Hezbollah only politically are just as unlawful as other direct attacks against civilians.

Individuals who commit serious violations of the laws of war with criminal intent are responsible for war crimes. A criminal investigation of such attacks would need to determine if those responsible attacked areas where civilians remained knowingly or recklessly. That is, a commander who knew that the assumption that all the civilians had left an area was not true but still targeted that area indiscriminately would be criminally responsible for ordering an unlawful attack.

Throughout the conflict, Israeli warplanes targeted civilian vehicles on roads and homes, apparently assuming them to be Hezbollah military movements. Among the deadly attacks on civilians trying to flee the conflict are the killing of 23 civilians, including 14 children and seven women, fleeing from Marwahin on July 15; the killing of six and wounding of eight civilians fleeing from `Aitaroun on July 19; the killing of three and wounding of 14 civilians fleeing from al-Tiri on July 23; the killing of 2 and wounding of four civilians fleeing from Mansouri on July 23; the wounding of nine civilians fleeing from Mansouri on July 23; the wounding of six ambulance drivers and three passengers in Qana on July 23; the killing of one civilian on a motorcycle on his way to buy food and medicines on July 24; the killing of seven civilians fleeing from Marja`youn on August 11; and the killing of seven and wounding of six civilians in the Beka` Valley on August 14. In all these cases, there is no evidence of a Hezbollah military presence that would justify the attacks.

A simple movement of persons or vehicles was often enough to cause a deadly air strike. On July 19, Israeli air strikes killed four members of the Darwish family in `Ainata, almost immediately after the civilians returned in a taxi to their homes after buying and distributing bread in the village. On August 4, an Israeli strike on a remote fruit farm in al-Qa` in the northern Beka` Valley resulted in the deaths of 25 Syrian Kurdish farm workers. Apparently, the IDF spotted a refrigerated truck leaving the farm shortly before the attack and fired at the farm buildings before confirming whether or not they were a legitimate military target. On August 7, an Israeli air strike killed five civilians in Insar, after relatives and neighbors had gathered in the home to socialize and then left the home at the end of the evening. On July 25, an Israeli drone fired a missile at Sa`da Nur al-Din in al-Ghassaniyeh, after she had gone to her home to collect food supplies and was driving back to the village shelter where she had been living with some 40 other civilians. On August 10, Israeli warplanes struck a home in Rabb al-Talatine, killing four women, soon after the women had moved a wounded relative (one of the four women killed in the attack) from one home to another.

The nature of Israel's bombing campaign in southern Lebanon belies Israel's argument that it had direct evidence linking particular targets to Hezbollah forces before striking them. Human Rights Watch's field investigations found that in many instances there was no apparent military objective in villages hit by Israeli attacks. But even where valid military targets existed somewhere in the vicinity, the humanitarian law prohibition against indiscriminate attacks prohibits a warring party from treating a town or village as a single military objective subject to general bombardment. That is, the mere presence of Hezbollah forces somewhere in a village or town would not justify the wholesale destruction of villages and towns meted out by the IDF. Nor may attacks be carried out that would be expected to cause disproportionate harm to the civilian population.

Compounding the problem, Israel targeted people or structures associated in any way with Hezbollah's military, political, or social structures-regardless of whether they constituted valid military objectives in accordance with international humanitarian law-and failed to take all necessary precautions to avoid civilian casualties when attacking suspected Hezbollah targets.

During the war, Israeli officials repeatedly stated that they considered all parts of Hezbollah-its military wing as well as its extensive political, social, and welfare branches-to be part of an integrated terror organization, and designated any person or office associated with Hezbollah to be legitimate military targets. Israel's UN ambassador, Dan Gillerman, told the UN Security Council on July 21 that Hezbollah was a "cancer" that "must be removed without a trace," and rejected any distinction between Hezbollah's military and political structures, stating that "[t]he [Hezbollah] member of parliament and the terrorist in the hills launching rockets at Israeli civilians both have the same strategy and goal. These labels cannot be allowed to give legitimacy to a gang of thugs[5]."

The apparent decision to target virtually all aspects of Hezbollah's membership and infrastructure led to the deaths of some civilians who were unconnected to Hezbollah, as well as Hezbollah members who were not engaged in military operations. An attack that knowingly and deliberately targeted people who were neither combatants nor civilians directly participating in the hostilities would be a serious violation of the laws of war. Insofar as the attack is launched knowing that the target should be treated as a civilian under international humanitarian law, those responsible would have committed a war crime.

Human Rights Watch research indicates that a large number of private homes of civilian Hezbollah members were targeted during the war, as well as a variety of civilian Hezbollah institutions such as schools, welfare agencies, banks, shops, and political offices, in addition to Hezbollah military infrastructure and the homes of Hezbollah combatants. The civilian death toll from such strikes is low, because almost all Hezbollah officials and members, and often even their neighbors, evacuated their homes in anticipation of Israeli air strikes. However, Human Rights Watch did document a number of cases in which civilians were killed during air strikes on civilian Hezbollah-affiliated targets during the war. For example, on July 13, the first day of massive air strikes, Israeli warplanes destroyed the home of Shaikh `Adil Muhammad Akash, an Iranian-educated Shi`a cleric believed to have a religious affiliation with Hezbollah, killing him, his wife, and his 10 children aged between two months and 18 years, and their Sri Lankan maid. There is no evidence (and the IDF has not publicly alleged) that Shaikh Akash was involved in Hezbollah military activities, and according to villagers he was only a religious leader in Dweir village. On July 23, an Israeli warplane fired at the Nabi Sheet home of Dr. Fayez Shukr, a leading member of the Lebanese Ba`ath Party and a political ally of Hezbollah, killing his 71-year-old father.

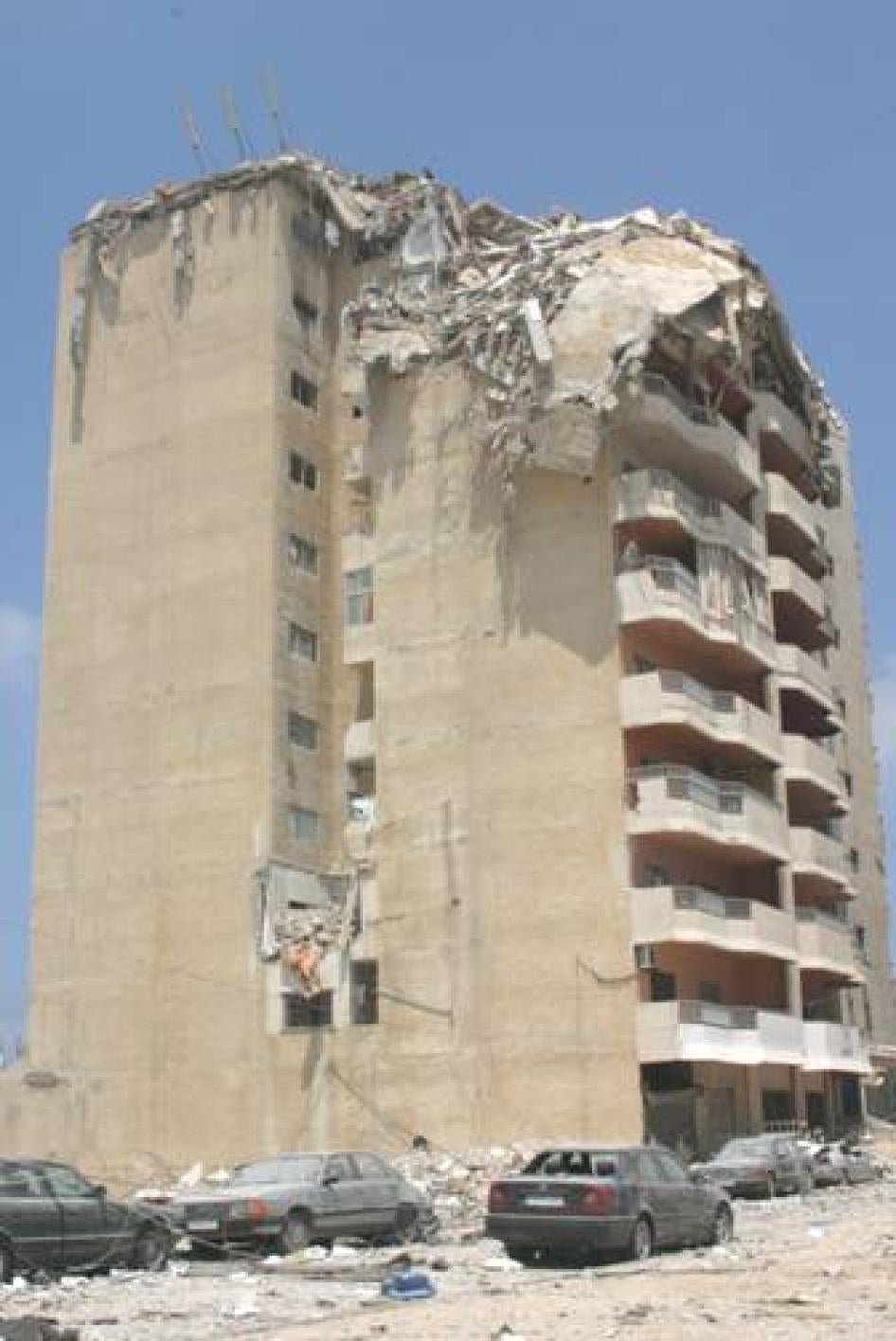

Israel's broad definition of legitimate Hezbollah targets is particularly evident in the pattern of attacks on the densely populated southern suburbs of Beirut, the neighborhood of Dahieh. In their attacks on this largely Shi`a district of high-rise apartment buildings, Israeli forces attacked not only Hezbollah military targets but also the offices of Hezbollah's charitable organizations, the offices of its parliamentarians, its research center, and multi-story residential apartment buildings in areas considered supportive of Hezbollah. Statements by Israeli officials strongly suggest that the massive IDF attacks in southern Beirut were carried out not against Hezbollah military targets, as required by the laws of war, but rather against entire neighborhoods because they were seen as pro-Hezbollah. Some statements by Israeli officials, including Israel's Defense Minister Amir Peretz and the IDF chief of staff Dan Halutz, suggest that some of the attacks on southern Beirut may have been unlawful retaliation for Hezbollah attacks against Israel.

In many cases in which civilian deaths did occur as Israel attempted to target civilian (or even military) Hezbollah officials, the main reason for the deaths was Israel's use of unreliable or dated intelligence that led to the misidentification of a particular building as Hezbollah-related, or Israel's failure to take adequate precautions to limit civilian casualties during strikes on presumed Hezbollah targets, particularly the homes of suspected Hezbollah militants.

On July 13, several Israeli missiles struck the home of 43-year-old Mustafa Khashab, killing him, his wife, his father, his sister, and two children aged 14 and 16. Mustafa had no links to Hezbollah and had permanently settled in Germany; it is possible that the strike attempted to target his brother, Safi Khashab, a high-ranking Hezbollah official, who had left the village the evening prior to the strike and did not live in the targeted home. A similar example of failed targeting of Hezbollah's members that led to civilian deaths is the Israeli attack on the town of al-Ghaziyeh on August 7 and 8, resulting in the deaths of 26 civilians. The apparent target of the al-Ghaziyeh attacks was a Hezbollah leader from the town, Amin Khalifa, as Israeli bombs struck his neighbor's home and the shops and homes of his brothers. By all indications, Amin Khalifa was not in al-Ghaziyeh during the war, including on the days the attacks took place.

Flawed intelligence and communication breakdowns contributed to many other cases of mistaken targeting by the IDF that resulted in civilian casualties. On July 16, an Israeli air strike on a multistory apartment building in Tyre killed 14 civilians, but the building was not the "Tyre Hezbollah headquarters" claimed by Israeli intelligence; it was the headquarters of Lebanon's Civil Defense offices in Tyre, an institution protected under humanitarian law. On July 25, an Israeli precision guided missile demolished an observer post of the UN's Observer Group Lebanon (OGL) outside Khiam, killing four UN observers, after UN officials had repeatedly been in contact with the IDF to warn them that they were firing close to a UN position. Although this report documents many cases in which Hezbollah fighters wrongfully fired from nearby UN positions, Hezbollah was not present near the Khiam UN position when an Israeli missile struck it. On the last day of the war, August 13, Israeli warplanes mounted one of the largest strikes of the war on the Imam Hassan Building Complex in the Rweiss neighborhood of southern Beirut, destroying eight ten-story buildings and killing at least 36 civilians and four low-ranking Hezbollah members, apparently acting on an inaccurate tip (see below) that a high-ranking Hezbollah official was staying at the complex.

* * *

Israel made extensive use of cluster munitions during the armed conflict in Lebanon.[6] As documented in a forthcoming Human Rights Watch report on Israel's use of cluster munitions in Lebanon, IDF cluster munitions struck wide swathes of southern Lebanon, particularly during the last three days of the conflict when both sides knew a settlement was imminent. The IDF has stated that it mostly fired cluster munitions at military objectives in open areas, and only fired near built-up areas "toward particular locations from which [Hezbollah] missiles were being launched against Israel, and after significant measures were taken to warn civilians to leave the area."[7] Human Rights Watch's field research in Lebanon showed that the Israeli military launched many of its cluster munition attacks at or near towns and villages, in some cases against Hezbollah forces, but in many other cases with no evident military objective.

The manner in which the IDF used cluster munitions and its reliance on antiquated munitions (many from the Vietnam war era) resulted in estimated failure rates of between 30 and 40 percent for many submunitions. This left as many as one million hazardous unexploded submunitions that littered fields and orchards and dozens of towns and villages in south Lebanon, threatening the returning civilian population.[8]As of June 20, 2007, the explosion of cluster munition duds since the ceasefire had killed 24 civilians and injured 183.[9] They have severely damaged the region's economy by turning agricultural land into minefields and interfering with the harvesting of tobacco, citrus, banana, and olive crops.

* * *

This report deals mostly with investigations of civilian deaths caused by aerial bombardment. However, in the course of our investigations we also documented two troubling cases in which Israeli ground troops killed unarmed Lebanese civilians who the soldiers should have seen posed no threat. On August 6, Israeli ground troops shot dead an elderly couple from the Nasrallah family (unrelated to the leader of Hezbollah, Hassan Nasrallah), aged 81 and 83, and their son and daughter, aged 54 and 58, as they came to check on their home in Taibe, which, unbeknownst to them, Israeli soldiers had occupied. On July 27, Israeli soldiers shot dead 36-year-old Maryam Khanafer as she was walking away from her home, which Israeli soldiers had occupied, holding her daughter's portable toilet. While these two cases of killings do not appear to be the result of any policy decision by Israeli officials, the circumstances of these killings merit investigation and, if appropriate, prosecution.

* * *

The Israeli policies summarized above guided IDF military operations in Lebanon during the conflict. That they reflect Israeli policy and not just the behavior of individual IDF members is evident from statements by Israeli government officials and military leaders that Israeli forces intentionally blurred the distinction between civilian and combatant. In one such statement issued on July 27, 2006, Israeli Justice Minister Haim Ramon said that "all those now in south Lebanon are terrorists who are related in some way to Hezbollah."[10] IDF spokesperson Jacob Dallal told the Associated Press:

[Hezbollah] is a terrorist institution, a terrorist organization that has to be debilitated and crippled as much as possible and that means [destroying] its infrastructure, that means its television, its institutions . In the war on terror in general, it's not just about hitting an army base, which they don't have, or a bunker. It is also about undermining their ability to operate . That ranges from incitement on television and radio, financial institutions and, of course, other grass-roots institutions that breed more followers, more terrorists, training bases, obviously, schools.[11]

In this context, Israel's claim that it only attacked military targets rings hollow.

The policies on the conduct of the war had a common element in that Israel sought to define a broad swath of civilians and civilian objects as military objectives. Israeli officials and commanders ostensibly recognized the humanitarian law requirement that they could target only military objectives but then unlawfully widened the scope of what they considered a legitimate military target. In doing so they conducted numerous attacks that were indiscriminate, disproportionate, and otherwise unjustified. Such attacks are serious violations of international humanitarian law. To the extent such attacks were conducted with knowledge or reckless indifference to the civilian nature of those being attacked, then those who ordered these attacks would have the criminal intent needed for the commission of war crimes as defined by international humanitarian law. And to the extent that senior commanders or officials knew or should have known that war crimes were being committed, and were in a position of authority to stop the attacks or punish those responsible and did not do so, they would be responsible for war crimes as a matter of command responsibility under international humanitarian law.[12]

Hezbollah Conduct During the War

Our research in Lebanon documented a number of cases in which Hezbollah fighters placed weapons or ammunition inside civilian homes or villages, as well as some cases in which Hezbollah fighters fired rockets from densely populated areas.[13] (Illustrative examples are detailed below.) Such conduct violates at minimum the legal duty to take all feasible precautions to avoid civilian casualties. Where Hezbollah combatants intended to use civilians to shield military assets from attack, the requisite criminal intent would be present for the war crime of shielding. However, as already noted, such practices were not nearly as widespread as official Israeli government accounts and some independent press accounts have suggested, and our research found that in all but a few of the cases of civilian deaths we investigated, Hezbollah fighters had not mixed with the civilian population or taken other actions to contribute to the targeting of a particular home or vehicle by Israeli forces.

In a few cases, Hezbollah's illegal conduct led to civilian deaths. For example, on July 13, an Israeli air strike destroyed two homes in Bar`achit, killing Najib Hussain Farhat, 54, and his 16-year-old daughter Zainab. Unbeknownst to the family, Hezbollah had built a large weapon storage facility located in the unoccupied home next door, which was also destroyed in the strike.

Similarly, on a number of occasions during the war, Hezbollah forces fired rockets from populated civilian areas, triggering deadly Israeli counterstrikes. On July 18, an Israeli air strike hit two civilian homes in `Aitaroun, killing nine members of the `Awada family, approximately two hours after villagers saw Hezbollah fighters firing rockets some 150 meters from the home. A local villager in Yaroun, a mixed Christian-Sh`ia border village, showed Human Rights Watch several places inside the village from where Hezbollah had fired rockets, leading to massively destructive Israeli counterstrikes.

In a case of Hezbollah's illegal conduct that led to the death of only combatants, on July 16, an air strike on a home in Yatar killed three Hezbollah fighters. The fighters had stored a recently fired rocket launcher in the home. In like fashion, on July 13 in Marwahin, a mostly Sunni village on the Lebanese-Israeli border, Hezbollah fighters drove a white van packed with weapons into the village, parked it next to a mosque, and then stored weapons and rockets in the home of a local civilian. Two days later, witnesses spotted Hezbollah fighters in the village moving weapons hidden under blankets.

Human Rights Watch also obtained credible evidence that Hezbollah maintained weapons storage facilities in apartment buildings in southern Beirut and used civilians to move some of those weapons to different locations, including at least one civilian shelter in an apartment building.

Hezbollah also fired from the vicinity of United Nations outposts on an almost daily basis. This often led to Israeli counterstrikes that resulted in death and injury to UN personnel. For observation purposes, the UN outposts tended to located on the top of hills, which also happen to be good positions from Hezbollah's military perspective to fire at Israel. However, insofar as Hezbollah commanders or fighters chose those locations to launch attacks because the proximity of UN personnel would make counterattack difficult, which would constitute the war crime of shielding. That the motives of Hezbollah combatants may have been mixed does not preclude criminality. Further investigations are needed, including by the UN, to determine whether Hezbollah forces acted unlawfully by purposefully using UN personnel as "human shields" or by placing UN personnel at unnecessary risk by deploying in the vicinity.

Commentators have cited the firing from near populated areas to support allegations that Hezbollah routinely used civilians as "human shields." International humanitarian law does not prohibit fighting in areas where civilians are present or prohibit the presence of forces in such areas. Armies have never been obliged to fight exposed out in the open. However, international humanitarian law does require all parties to a conflict to take all feasible precautions to protect civilians from the effects of combat. According to the International Committee of the Red Cross' (ICRC) authoritative Commentary on the Additional Protocols, several state delegations to the diplomatic conference drafting the 1977 protocols to the Geneva Conventions sought to define "everything feasible" as including "all circumstances relevant to the success of military operations." But the ICRC considered such a criterion to be "too broad":

There might be reason to fear that by invoking the success of military operations in general, one might end up by neglecting the humanitarian obligations prescribed here. Once again the interpretation will be a matter of common sense and good faith.[14]

Parties to a conflict must avoid, to the extent feasible, placing military objectives-personnel, equipment and weaponry-in densely populated areas. As the ICRC Commentary notes, "For example, a barracks or a store of military equipment or ammunition should not be built in the middle of a town."[15] Thus while using ammunition in a village during a firefight would be lawful under humanitarian law (though the presence of ammunition would render a location a legitimate target), the storage of ammunition inside a village would not.

Parties must also, to the extent feasible, remove civilians under their control from the vicinity of military objectives.[16] The ICRC Customary International Humanitarian Law states that this obligation "is particularly relevant where military objectives can not feasibly be separated from densely populated areas."[17] Thus parties to a conflict seeking to deploy in populated areas should take measures to ensure that civilians move to safer areas.

While failing to take precautions to protect civilians violates humanitarian law, intentionally making use of civilians to render military forces or a place immune from attack is considered to be the more serious violation of "shielding." Because the definition of shielding incorporates the concept of intent, any individual ordering shielding would almost invariably be committing a war crime.

While we documented cases where Hezbollah stored weapons inside civilian homes or fired rockets from inside populated areas, our investigations to date suggest relatively few cases where Hezbollah might have specifically intended to use the presence of civilians to shield itself from counterattack-certainly not enough to constitute a widespread or systematic pattern. One significant exception is Hezbollah's frequent firing of rockets from the vicinity of UN outposts, where the evidence strongly suggests that one of the two likely motives for doing so was to use the UN noncombatants to shield Hezbollah from counterattack.

Even where Hezbollah endangered civilians by unlawfully carrying out military operations in proximity to densely populated areas, Israel was not justified under the laws of war in responding with disproportionate attacks. International humanitarian law prohibits warring parties from conducting attacks in which the expected civilian loss is disproportionate to the anticipated military gain, even if the other party is committing violations of the laws of war.

While the humanitarian law applicable during the Israeli conflict with Hezbollah placed no obligation on those participating in the hostilities to wear uniforms,[18] the routine appearance of Hezbollah fighters in civilian clothes and their failure to carry their weapons openly put the civilian population of Lebanon at risk. Since Hezbollah fighters regularly appeared in civilian clothes, Israeli forces would have had difficulty distinguishing between fighters and other male, fighting-age civilians, and such difficulty increased the dangers of IDF operations to the civilian population of Lebanon. However, the failure of Hezbollah fighters to consistently distinguish themselves as combatants does not relieve Israeli forces of their obligation to distinguish at all times between combatants and civilians and to target only combatants.[19] That this task may have been difficult at times does not negate the obligation. In cases of doubt, a person must be considered a civilian and not a legitimate military target.[20]

Summary of Methodology and Errors Corrected

This report builds on Human Rights Watch's August 2006 report, Fatal Strikes: Israel's Indiscriminate Attacks Against Civilians in Lebanon. It represents the most comprehensive study of civilian deaths in Lebanon to date, based on extensive on-the-ground research. During the course of five months of continuous research in Lebanon and Israel, Human Rights Watch investigated the deaths of more than 561 persons during Israeli air and groundstrikes and collected additional summary information about an additional 548 deaths, thus accounting for a total number of 1,109 deaths (civilians and combatants) from the 34-day conflict. Human Rights Watch interviewed more than 355 victims and witnesses of attacks in one-on-one settings and collected information from hospitals, humanitarian groups, journalists, military experts, and government agencies. We visited more than fifty villages and conducted on-site inspections. Human Rights Watch also conducted research in Israel, inspecting the IDF's use of weapons and discussing the conduct of forces with IDF officials.

Human Rights Watch approached Israeli officials for information on a number of occasions. Our researchers held several meetings with officials in the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the IDF, and the Ministry of Justice. We also sent a letter on January 8, 2007 to then-Defense Minister Amir Peretz requesting detailed information about the cases described in this report, which is attached as an appendix to this report. Human Rights Watch also talked to Israeli soldiers and officers to learn more about the instructions the IDF gave to its soldiers and the precautions it took to avoid civilian casualties.

This report does not address Israeli attacks on Lebanon's infrastructure, which have been reported on elsewhere,[21] or Israel's use of cluster munitions, which we will release a separate report on shortly. It also does not address Hezbollah's rocket attacks on Israel, which we also have reported on separately, in Civilians under Assault: Hezbollah's Rocket Attacks on Israel during the 2006 War.

This report corrects two major and several minor inaccuracies from Human Rights Watch's earlier report issued during the 2006 war (Fatal Strikes):

Further Human Rights Watch investigations into a deadly strike at Srifa established that an Israeli attack there killed 17 combatants and five civilians on July 19, not the 26 civilians claimed in Fatal Strikes.

In a second case, involving an Israeli air strike on the village of `Aitaroun that killed nine members of the `Awada family, further Human Rights Watch research established that Hezbollah had fired rockets from near the home a few hours before the deadly air strike, although there is no doubt that all of those killed in the air strike were civilians unconnected to Hezbollah.

Human Rights Watch regrets these two major inaccuracies in its Fatal Strikes report. We have corrected several smaller errors relating to dates of strikes, ages and names of victims, and the previously unreported presence of an empty Hezbollah civilian office in a building targeted by an Israeli air strike in Bint Jbeil that killed two civilians. Wherever we have corrected errors from previous reports, the text or footnotes of this report clearly identify the information corrected.

To avoid any such mistakes in this report, we reexamined all of the cases included in Fatal Strikes and conducted additional interviews, site inspections, and visits to graveyards to establish whether victims were civilians or combatants. In addition, we investigated a further 71 cases in similar detail. Thus, our findings do not rely on any one piece of evidence or witness testimony, but rather on multiple pieces of evidence that together provide the information needed to verify the circumstances and victims of each attack. Our findings in this report reconfirm the central conclusion of Fatal Strikes: the primary victims of Israel's bombardment of Lebanon were Lebanese civilians, and they died primarily because of the indiscriminate nature of Israeli attacks, not because of Hezbollah's practices.

II.Recommendations

To the Government of Israel

- Amend and revise wartime policies and military strategies that treat all persons remaining in an area following warnings to evacuate as combatants or civilians subject to attack, and instead ensure full compliance with international legal obligations prohibiting indiscriminate and disproportionate attacks, and that require all feasible precautions be taken to avoid civilian casualties;

- Amend and revisepolicies and military strategies that authorize the IDF to target people or structures associated with Hezbollah institutions, regardless as to whether they constitute valid military objectives under international humanitarian law, and to ensure that all necessary precautions are taken to avoid civilian casualties;

- Order the Israeli military to conduct a review of its operational guidelines. This review should focus in particular on the process of selecting targets and the types of weapons used. The review should be public and conducted by a special commission including members of the military, the Knesset, and independent legal experts.

- Institute procedures within the Israeli military to ensure that it conducts all military operations in full accordance with international humanitarian law treaties and customary law.

- Special operational attention should be given in the Israeli military to prohibit and prevent attacks that do not distinguish between military objectives and civilians, unlawfully target civilians who are not legitimate military objectives, or cause harm to civilians that is disproportionate to the expected military gain.

- Ratify the First and Second Protocols Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 1949, or at least publicly affirm the provisions that bind Israel as a matter of customary international law.

- Investigate Israeli government officials, IDF officers, and soldiers who ordered or directly committed serious violations of the laws of war and impose disciplinary measures or criminally prosecute as appropriate.

- Expand the mandate of the Winograd Commission to investigate laws of war violations by the IDF during the armed conflict, and the responsibility of IDF commanders for such violations.

To Hezbollah

- Adopt operational measures to ensure the compliance of Hezbollah forces with the requirements of international humanitarian law.

- Take all feasible measures to ensure that Hezbollah forces do not place civilians at unnecessary risk because of their deployments or the placement of weapons and ammunition in populated areas.

- Reaffirm to all military forces the absolute duty never to use civilians or other noncombatants to shield military forces and materiel from attack.

- Investigate in particular the incidents of fire from nearby UN positions to determine whether fighters intentionally used the presence of the UN to shield themselves from attack.

- Adopt recommendations set out in Civilians under Assault with respect to rocket attacks on Israel in violation of the laws of war.

- Ensure that individual members of Hezbollah are trained in the laws of war and abide by them. Take appropriate disciplinary measures against members who act in violation of the law.

To the Government of Lebanon

While recognizing the political difficulties presently faced by the government of Lebanon, we urge it to take the following measures at the earliest time feasible, consistent with its state responsibilities and obligations:

- Take appropriate steps to ensure that Hezbollah implements the recommendations listed above.

- Interdict the delivery of rockets to Hezbollah so long as it continues to use rockets in violation of international humanitarian law, by firing at civilians or firing indiscriminately into civilian areas.

- Investigate alleged violations of international humanitarian law by Hezbollah forces. We believe the credibility of the investigation would be heightened were it to be conducted by an independent and credible committee of respected national experts in international humanitarian law.

- Investigate and prosecute members of Hezbollah who have individual or command responsibility for the alleged commission of war crimes.

- Cooperate with international investigations into violations of international humanitarian law.

To the Secretary General of the United Nations

- Use your influence with Israel and Hezbollah to urge them to adopt measures to better comply with international humanitarian law.

- Establish an International Commission of Inquiry to investigate reports of violations of international humanitarian law, including possible war crimes, in Lebanon and Israel and to formulate recommendations with a view to holding accountable those on both sides of the conflict who violated the law.

To the Government of the United States

- Conduct a full investigation into Israel's use of US-supplied arms, ammunition, and other materiel in violation of international humanitarian law.

- Suspend transfers to Israel of arms, ammunition, and other materiel that have been documented or credibly alleged to have been used in violation of international humanitarian law in Lebanon, as well as funding or support for such materiel, pending certification by the US State Department that Israel has stopped using, and has made clear commitments not to use in the future, such arms, ammunition, and other material in violation of international humanitarian law.

To the Governments of Syria and Iran

- Do not permit transfers to Hezbollah of arms, ammunition, and other materiel that have been documented or credibly alleged to have been used in violation of international humanitarian law in Lebanon, as well as funding or support for such materiel, pending a commitment by Hezbollah that it will not use such arms or material in violation of international humanitarian law.

III.Methodology

This report is based primarily on investigations by Human Rights Watch researchers who were in Lebanon from the onset of the conflict and who carried out investigations throughout the conflict (July 12-August 14, 2006) as well as in the months after the conflict (August-December 2006). The research team included Human Rights Watch's Lebanon researcher, the director of Human Rights Watch's Emergency Program, Human Rights Watch's Senior Military Analyst, and consultants hired by Human Rights Watch.

Human Rights Watch has long experience in investigating the conduct of armed conflict. Human Rights Watch monitors and reports on conflicts around the world, from the civil war between the Maoist and government forces in Nepal to the multi-dimensional conflict in Iraq. Among our previous reports on air wars are our 1999 Report on the NATO air campaign in Kosovo, Civilian Deaths in the Nato Air Campaign, and our 2003 report on the US-led Coalition's air war in Iraq, Off Target: The Conduct of the War and Civilian Casualties in Iraq. Our investigations have contributed to the prosecution of war criminals and genocide suspects from Rwanda, the Balkans, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Darfur, and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Human Rights Watch has covered previous armed conflicts between Israel and Hezbollah. Our 1996 report, Civilian Pawns: Laws of War Violations and the Use of Weapons on the Israel-Lebanon Border, examined the impact on civilians of military activities from July 1993 until April 1996 between Israel and Hezbollah; our 1997 report, Operation Grapes of Wrath: the Civilian Victims, examined the conduct of the IDF and Hezbollah during the escalation of military activities in April 1996.

Our investigations are guided by international humanitarian law, also known as the laws of war, which can be found in treaties such as the Geneva Conventions of 1949, and by customary international law. The aim of our investigations is to provide an impartial account of the adherence to the law of all parties to a conflict-including non-state actors such as Hezbollah-and to document serious violations of that law. Human Rights Watch researchers are trained in the laws of war and professional investigation techniques, and have many years of experience working in conflict zones.

During the 2006 conflict, Human Rights Watch issued a preliminary report of its findings, Fatal Strikes: Israel's Indiscriminate Attacks Against Civilians in Lebanon. The report was based on Human Rights Watch's extensive on-the-ground investigations into some two dozen incidents in which IDF bombing and missile attacks killed civilians. It concluded that the IDF consistently committed indiscriminate attacks in which it failed to distinguish between combatants and civilians and that some of those responsible had committed possible war crimes. The report also concluded that in some cases, the timing and intensity of the attack, the absence of a military target, as well as return strikes on rescuers suggested that individual Israeli combatants may have deliberately targeted civilians, although Human Rights Watch has no evidence that this was done as a matter of policy. The report explicitly recognized the limitations of its findings because the ongoing fighting limited the information and investigative opportunities available to researchers: "Human Rights Watch does not claim that the findings are comprehensive; further investigation is required to document the war's complete impact on civilians and to assess the full scope of the IDF's compliance with and disregard for international humanitarian law."[22]

After the imposition by the United Nations Security Council of the ceasefire that ended hostilities, Human Rights Watch researchers immediately embarked on a more extensive investigation of the IDF's and Hezbollah's conduct during the war, a process of investigation that took five months to complete. Human Rights Watch researchers visited over 50 villages, towns, and locations to assess the impact of the war on the civilian population of Lebanon, and interviewed over 355 persons to get as accurate a picture as possible about individual incidents. We selected these villages and towns because civilians had died in them. The end of hostilities dramatically improved the research climate, as researchers were able to locate and interview witnesses in the privacy of their own homes and to conduct on-site visits to attack sites and cemeteries around Lebanon.

Human Rights Watch researchers followed a standard methodology to investigate the impact of the war on civilians throughout Lebanon. In each village, town, or location investigated by Human Rights Watch, our investigators first established the total number of persons reportedly killed, civilian and combatant. The researchers then interviewed local officials as well as family members and eyewitnesses to the incidents in which persons were killed, to establish the exact circumstances of those killings. In the majority of villages visited, our researchers were able to investigate every death in the village.

We conducted all interviews separately and independently from each other, so witnesses were normally unaware of what others had already told Human Rights Watch. Each interview normally lasted about one hour, and was designed to gather enough factual detail to assess the consistency of, and corroborate information given by, different witness accounts. Human Rights Watch asked interviewees for as much information as they had about attacks. We attempted to ask each person the same set of questions about an attack, but on some occasions witnesses could not provide answers to particular questions, such as the location of Hezbollah fighters or weapons, simply because they did not have such information available to them. In each instance, Human Rights Watch researchers endeavored to find multiple witnesses to individual events, in order to allow for corroboration and the checking for consistency of accounts.

`Imad Sulaiman Ahmad, mukhtar of Hadatha, shows the damage sustained in town from Israeli airstrikes. 2006 Peter Bouckaert/Human Rights Watch

In some cases in this report, particularly in cases where Lebanese witnesses discuss Hezbollah abuses, we have withheld the names of the witness and other identifying information to protect these witnesses from possible retaliation. To ensure that witnesses would speak candidly about both Israeli and Hezbollah abuses, Human Rights Watch researchers conducted all interviews in as private a setting as possible, and explained to witnesses that they could chose to remain anonymous to prevent relatiation. In all cases, the identities of the witnesses are on file with Human Rights Watch.

In addition to the detailed interviews, Human Rights Watch also conducted on-site investigations of attack sites, examining them for signs of Hezbollah presence or the types of weapons used. For each site visited, Human Rights Watch researchers photographed the site, documented any forensic evidence found, and collected the GPS coordinates.

A banner announcing the death of a Hezbollah combatant in the village of Yatar.It reads: "We present our condolences to the owner of era and time [religious reference] for the martyrdom of the mujahid brother Muhammad Hussain Haydar Ja`far 'Malak'." The use of Hezbollah symbols and the terms "martyrdom," "mujahid brother," and the giving of the nom de guerre "Malak" identify this individual as a Hezbollah combatant. 2006 Wissam Al Salibi for Human Rights Watch

Whenever possible, Human Rights Watch researchers also visited the cemeteries where those killed in Israeli strikes were buried, to examine whether their gravestones identified them as civilians or as "martyrs" or "fighters" for Hezbollah or other armed groups. Our researchers also examined the many "martyr" posters found throughout Lebanon to establish whether certain individuals killed were civilians or combatants.

The information collected by Human Rights Watch researchers from cemeteries and "martyr" posters proved important in corroborating whether an individual was a civilian, combatant, or Hezbollah official. In southern Lebanon and elsewhere in the country, many consider it an honor for persons who died in the conflict to be identified as a "martyr" or "fighter," with little likelihood that a Hezbollah fighter would be buried as a civilian. Human Rights Watch did not find any cases in which known combatants or Hezbollah officials killed in the conflict were buried as civilians, or where the family or Hezbollah officials denied a person's status as a fighter or Hezbollah official.

Burial practices also distinguish between civilian members of Hezbollah or other militant organizations, who are buried merely with a Hezbollah (or other militant organization's) symbol on their grave stone, and Hezbollah fighters (or fighters from other militant groups), who are buried as military "martyrs" with distinct markings on their grave stones and Koranic verses different from those used on the graves of Hezbollah civilian members (or other civilians). Hezbollah commanders and elite fighters who died in combat have additional markings on their grave stones, such as an identification of their leadership position (e.g., "the martyr leader," al-shahid al-qa'id) or noms de guerre given to full-time Hezbollah fighters.

|

The tombstone of Hezbollah fighter `Ali Abdullah Suli in Taibe.The tombstone is marked as that of a Hezbollah combatant, with the official Hezbollah symbols and a description of the deceased as a "Martyr Leader." It provides his nom de guerre "Mr. Safi" and states that he died in the Taibe fighting.Human Rights Watch researchers visited graveyards throughout Lebanon to assist them in distinguishing between civilians and combatants who died in the conflict. 2006 Peter Bouckaert/Human Rights Watch |

The tombstone of a civilian, Hussain Ahmad Nasrallah, who died in Taibe after being shot by Israeli ground troops.The graves of civilians did not bear Hezbollah symbols, and killed civilian were not claimed as martyrs by Hezbollah or other armed groups. Human Rights Watch researchers visited graveyards throughout Lebanon to assist them in determining the status of individuals who died in the conflict. 2006 Peter Bouckaert/Human Rights Watch |

The same applies for the much smaller number of militants from the Amal party and the Lebanese Communist Party who died fighting in the conflict, although it appears that at least in one case, Amal tried to claim two non-combatant members killed in the war as "martyrs" in order to bolster its status as a militant organization.

The visits to cemeteries provided an important safeguard against potential misrepresentations by witnesses. For instance, in our Fatal Strikes report issued during the war, eyewitnesses were not always forthcoming about the identity of those that died, and in the case of Srifa, misled our researchers. After the conflict, a visit to the graveyard made it possible to establish that most of those killed in Srifa were actually combatants because they were buried as "martyrs," not civilians.

Human Rights Watch researchers, using corroborative visits to the cemetaries, did not find any other cases where witnesses deliberately tried to mislead us on whether casualties were civilian or militants.

In addition to interviewing persons who witnessed attacks, Human Rights Watch also conducted numerous interviews with various officials, including Lebanese military and humanitarian officials; Hezbollah members and officials; UNIFIL and other United Nations officials; members of the Lebanese Civil Defense and the Lebanese Red Cross who were present at various recovery efforts, as well as their spokespersons; representatives of international and local humanitarian organizations; doctors and officials at various hospitals that received the wounded and the dead; international and local journalists and photographers; and diplomats, academics, and other policy makers.

To further check the accuracy of our research, Human Rights Watch reviewed all publicly available information about the incidents it investigated, including statements of the IDF and the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs; international, Israeli, and Lebanese newspapers, wire services, and magazines (in English, Hebrew, and Arabic); statements by local and international organizations; and reports by local and international human rights and other investigative agencies (such as the UNHRC's Commission of Inquiry) to ensure that there were no accounts that contradicted our own findings. Whenever we found contradictory or additional information, Human Rights Watch carried out additional investigations and interviews to determine the accuracy of our information. Where we could not resolve factual contradictions, this report reflects the competing accounts and makes it clear that there are contradictory accounts of individual incidents.

Human Rights Watch researchers sought information from Israeli officials, including the IDF and the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs, about the various attacks investigated by Human Rights Watch, as well as any evidence to support claims of Hezbollah shielding practices in these attacks. Human Rights Watch provided Israeli officials with a complete list of place names, GPS coordinates, and times of the attacks it was investigating (Lebanese and Israeli place names do not always correspond, and attacks are normally logged by GPS location and time of attack, not the name of the location). Human Rights Watch received only a limited response to its queries to Israeli officials, but this report reflects those responses where relevant. In addition, the report reflects any public IDF statements.[23]

Human Rights Watch investigators also investigated the conduct of Hezbollah inside Lebanon during the conflict, including allegations of abuses against the Lebanese population during the war. This report focuses on the behavior of Hezbollah with respect to its conduct inside Lebanon; Civilians under Assault: Hezbollah's Rocket Attacks on Israel during the 2006 War focuses specifically on Hezbollah's rocket campaign against Israel.

A note on terminology: we use the term "Hezbollah fighter" or "combatant" to identify Hezbollah military personnel who took an active part in combat, as opposed to non-military Hezbollah members, who we refer to simply as "Hezbollah members." Hezbollah is a huge, multi-faceted organization in Lebanon. It has both a military wing (known as the "Islamic Resistance" or al-Muqawama al-Islamiyya) and non-military organizations, such as its political party, its educational institutions, and its social welfare organizations, including hospitals. Because most Lebanese civilians distinguish between the Hezbollah organization as a whole and its military or "resistance" wing, this report keeps the term "resistance" when witnesses used it during quoted interviews. The use of the word "resistance" in this report is not meant to imply a Human Rights Watch position on the legitimacy or illegitimacy of Hezbollah's military campaign against Israel.

Like other Lebanese political parties, Hezbollah has thousands of members who are not actively involved in any aspect of its military operations. While Hezbollah combatants are legitimate military targets, ordinary members of Hezbollah, as well as Hezbollah officials not directing or engaged in military activities, are not legitimate military targets. The term mukhtar identifies a local official in Lebanon who performs various administrative tasks such as birth registrations or authentication of documents. In Lebanese villages, mukhtars know a lot about the community they serve and represent an important source of information.

In accordance with its institutional mandate, Human Rights Watch maintains a position of strict neutrality on matters concerning the legitimacy of resorting to war because we find it the best way to promote our primary goal of encouraging all sides in the course of the conflict to respect international humanitarian law. Accordingly, this report does not address whether Hezbollah or Israel was justified or acting legally in their decisions to go to war or to escalate the war. We look only at how they complied with their legal duties to spare civilians the hazards of that war.

IV. Legal Standards Applicable to the Conflict

A. Applicable International Law

The armed conflict between Israel and Hezbollah in July-August 2006 fell within a body of law called international humanitarian law, also known as the laws of war. The sources of humanitarian law are treaty law and customary law, which binds both states and non-state armed groups.

The most relevant treaty law to the 2006 conflict is the Geneva Conventions of 1949, to which virtually all states are party, including Israel and Lebanon. Article 2 common to the 1949 Geneva Conventions provides for the full applicability of the conventions when there is an armed conflict between High Contracting Parties (that is, states), or when there has been a partial or total occupation of a High Contracting Party (even when that occupation meets with no resistance from the state).[24] At least to the extent of armed hostilities between the states of Israel and Lebanon and Israeli control over Lebanese territory, the 2006 conflict was an international armed conflict. In general, the 1949 Geneva Conventions provide for the security and well being of persons no longer taking part in the hostilities, namely captured combatants, the wounded, and civilians in the control of belligerent forces. They also provide special protections, for instance, to medical personnel and hospitals.

There has been controversy over the humanitarian law applicable to Hezbollah. Unless Hezbollah forces are considered to be a part of the Lebanese armed forces, demonstrated allegiance to such forces, or were under the direction or effective control of the government of Lebanon,[25] there is a basis for finding that hostilities between Israel and Hezbollah are covered by the humanitarian law rules for a non-international (that is, non-intergovernmental) armed conflict.[26] Under such a characterization, applicable treaty law would be common article 3 to the 1949 Geneva Conventions (the "treaty within a treaty"), which protects captured combatants and civilians from murder, cruel and inhuman treatment, being held as hostages, and unfair trials. Whether captured Hezbollah or Israeli fighters would be entitled to the protections of the Third Geneva Convention for prisoners of war, the Fourth Geneva Convention for protected persons, or only the basic protections of common article 3, would depend on the legal characterization of the conflict and a factual analysis of Hezbollah and its relationship to the Lebanese armed forces. Such an analysis is not necessary for analyzing the conduct of hostilities between Israel and Hezbollah, the focus of this report.[27]

International humanitarian law on the conduct of hostilities, traditionally known as "Hague law" because historically treaties regulating combat were drafted there, is set out in the Hague Regulations of 1907[28] and the First Additional Protocol of 1977 to the Geneva Conventions (Protocol I).[29] Protocol I, which provides the most detailed and current codification of the conduct of hostilities during international armed conflicts, was not directly applicable to the 2006 conflict because Israel is not a party to the treaty. Nevertheless, many of the provisions of Protocol I have been recognized by states, including Israel, to be reflective of customary international law.[30] Thus the legal analysis applied in this report frequently references norms enshrined in Protocol I, but as an important codification of customary law rather than as a treaty obligation. Customary humanitarian law as it relates to the fundamental principles concerning conduct of hostilities is now recognized as largely the same whether it is applied to an international or a non-international armed conflict.[31]

B. Protections for Civilians and Civilian Objects

International humanitarian law limits permissible means and methods of warfare by parties to an armed conflict and requires them to respect and protect civilians and captured combatants. "Means" of combat refers generally to the weapons used, while "methods" refers to the manner in which such weapons are used.

The First Additional Protocol of 1977 to the Geneva Conventions (Protocol I)[32] and the 1907 Hague Regulations lay out the law that protects civilians during armed conflict.[33] Most of the relevant provisions of both treaties are considered customary law, rules of international law that are based on established state practice and are binding on all parties to an armed conflict, whether they are state actors or non-state armed groups.[34]

The two fundamental tenets of international humanitarian law are those of "civilian immunity" and "distinction." [35] They impose a duty, at all times during the conflict, to distinguish between combatants and civilians, and to target only the former. Article 48 of Protocol I states, "the Parties to the conflict shall at all times distinguish between the civilian population and combatants and between civilian objects and military objectives and accordingly shall direct their operations only against military objectives."[36] While Protocol I recognizes that some civilian casualties are inevitable, parties to a conflict may not target civilians and civilian objects and may direct their operations against only military objectives.

Civilian objects are those that are not considered military objectives.[37] Military objectives are combatants and those objects that "by their nature, location, purpose or use, make an effective contribution to military action and whose total or partial destruction, capture or neutralization, in the circumstances ruling at the time, offers a definite military advantage."[38] In general, the law prohibits direct attacks against what are by their nature civilian objects, such as homes and apartments, places of worship, hospitals, schools, or cultural monuments, unless they are being used for military purposes.[39]

International humanitarian law prohibits indiscriminate attacks. Examples of indiscriminate attacks are those that "are not directed at a specific military objective" or that use means that "cannot be directed at a specific military objective."[40]

One form of prohibited indiscriminate attack is area bombardment. Any attack, whether by aerial bombardment or other means, that treats as a single military objective a number of clearly separated and distinct military objectives located in a city, town, village, or other area containing a concentration of civilians and civilian objects, is regarded as an indiscriminate attack and prohibited. Similarly, if a combatant launches an attack without attempting to aim properly at a military target, or in such a way as to hit civilians without regard to the likely extent of death or injury, it would amount to an indiscriminate attack.[41] Indiscriminate attacks are "of a nature to strike military objectives and civilians or civilian objects without distinction." Article 51(4) and Article 51(5) of Protocol I enumerate five kinds of indiscriminate attacks: those that 1) are not directed at a "specific military objective," 2) cannot be directed at "a specific military objective," 3) have effects that violate the Protocol, 4) treat separate urban military objectives as one (carpet bombing), or 5) violate the principle of proportionality (described below).

Also prohibited are attacks that violate the principle of proportionality. Disproportionate attacks are those that are "expected to cause incidental loss of civilian life, injury to civilians [or] damage to civilian objectives ... which would be excessive in relation to the concrete and direct military advantage anticipated" from that attack.[42] The expected danger to the civilian population and civilian objects depends on various factors, including their location (possibly within or near a military objective), the accuracy of the weapons used (depending on the trajectory, the range, environmental factors, the ammunition used, etc.), and the technical skill of the combatants (which can lead to random launching of weapons when combatants lack the ability to aim effectively at the intended target).[43]

International humanitarian law requires that the parties to a conflict take constant care during military operations to spare the civilian population and to take all feasible precautions to avoid or minimize the incidental loss of civilian life as well as injury to civilians and damage to civilian objects.[44] In its authoritative Commentary on Protocol I, the International Committee of the Red Cross explains that the requirement to take all "feasible" precautions means, among other things, that the person launching an attack is required to take the steps needed to identify the target as a legitimate military objective "in good time to spare the population as far as possible."

These precautions include:

- Doing "everything feasible to verify" that the objects to be attacked are military objectives and not civilians or civilian objects. If there are doubts about whether a potential target is of a civilian or military character, it "shall be presumed" to be civilian.[45] The warring parties must do everything feasible to cancel or suspend an attack if it becomes apparent that the target is not a military objective.[46]

- Taking "all feasible precautions in the choice of means and methods" of warfare so as to avoid, and in any event minimize, "incidental loss of civilian life, injury to civilians and damage to civilian objects."[47]

- When circumstances permit, giving "effective advance warning . . . of attacks which may affect the civilian population."[48]

- "When a choice is possible between several military objectives for obtaining the same military advantage," carrying out the attack that may be "expected to cause the least danger to civilian lives and civilian objects."[49]

- Avoiding "locating military objectives within or near densely populated areas."[50]

- Endeavoring "to remove the civilian population ... from the vicinity of military objectives."[51]

International humanitarian law does not prohibit fighting in urban areas, although the presence of civilians places greater obligations on warring parties to take steps to minimize harm to civilians. Humanitarian law prohibits belligerents from using civilians to shield military objectives or military operations from attack. "Shielding" refers to intentionally using the presence of civilians to render certain points, areas, or military forces immune from military attack.[52] Taking over a family's house and not permitting the family to leave for safety so as to deter the enemy from attacking is a simple example of using "human shields."

The prohibition on shielding is distinct from the requirement that all warring parties take "constant care" to protect civilians during the conduct of military operations by, among other things, taking all feasible precautions to avoid locating military objectives within or near densely populated areas.[53] Such a determination will depend on the situation. Placing ammunition dumps in the center of a town during peacetime is a clear violation. Storing ammunition in civilian areas during fighting will be lawful or unlawful depending on a various factors, such as whether the warring faction took proactive steps to remove civilians from the vicinity, and whether other locations that did not endanger civilians presented themselves. Unlawfully placing forces, weapons, and ammunition within or near densely populated areas amounts to shielding only when there is a specific intent to use the civilians to deter an attack.

With respect to individual responsibility, serious violations of international humanitarian law, including deliberate, indiscriminate, and disproportionate attacks harming civilians, when committed with criminal intent are grave breaches (see Additional Protocol I) or, in common parlance, war crimes. Individuals may also be held criminally liable for attempting to commit a war crime, as well as assisting in, facilitating, aiding or abetting a war crime. Responsibility may also fall on persons planning or instigating the commission of a war crime.[54] Commanders and civilian leaders may be prosecuted for war crimes as a matter of command responsibility when they knew or should have known about the commission of war crimes and took insufficient measures to prevent them or punish those responsible.[55]

V. Background to the Israel-Hezbollah war

A. Hezbollah's "Operation Truthful Promise"

At about 9 a.m. on July 12, 2006, Hezbollah fighters crossed into Israeli territory and attacked an IDF convoy patrolling the border, killing three IDF soldiers and taking two captured IDF soldiers back into Lebanon. The Hezbollah operation appears to have been well-planned, as it was preceded by diversionary Hezbollah rocket fire on IDF positions at the coast and near the Israeli town of Zarit.[56] Almost immediately after the attack, an IDF Merkava tank sent into Lebanon to seek to retrieve the captured soldiers ran into a massive anti-tank mine, estimated to contain as much as 300 kilograms of explosives, killing three IDF soldiers and wounding a fourth. An eighth IDF soldier was killed in the fighting that followed to retrieve the bodies and wounded from the tank.[57]

Dubbed "Operation Truthful Promise" by Hezbollah, the raid fulfilled Hezbollah leader's Hassan Nasrallah's longstanding aim to take IDF soldiers hostage in order to pressure Israel to release remaining Lebanese prisoners in Israeli prisons,[58] and to seek the return of the disputed Israeli-occupied Sheba` Farms area to Lebanese control.[59] Immediately following the raid, Hezbollah stated that it would return the abducted soldiers to Israel through "indirect negotiations" resulting in a "trade" with Lebanese prisoners held in Israeli prisons.[60]

Human Rights Watch has criticized Hezbollah for illegally refusing to confirm the fate of the two abducted soldiers or to permit the International Committee of the Red Cross access to them. We have also criticized Hezbollah for holding these detainees as hostages whose release is conditioned on Israel's release of a large number of its detainees.[61]

B. Israel's "Operation Change of Direction"

After the abduction of the two soldiers, Hezbollah perhaps expected a response from Israel limited to several days of air strikes on Hezbollah targets, followed by a prisoner exchange negotiation, as had happened during prior hostage-taking incidents.[62] Instead, Israel mounted a full-scale military offensive not only to retrieve the captured soldiers, but also to clear Hezbollah from its northern border.

Prime Minister Olmert declared Hezbollah's raid into Israel and the capture of the two IDF soldiers an "act of war" by the government of Lebanon, and stated that "Lebanon is responsible and Lebanon will bear the consequences of its actions."[63] Amir Peretz, Israel's Defense Minister, stated that the IDF would launch a military offensive that would continue until the Lebanese Army had replaced Hezbollah in southern Lebanon, saying that "if the government of Lebanon fails to deploy its forces, as is expected from a sovereign government, we shall not allow any further Hizbollah to remain on the borders of the state of Israel."[64] The IDF's Chief of Staff, Dan Halutz, bluntly stated that the Israeli offensive would "turn back the clock in Lebanon by 20 years" if the abducted soldiers were not immediately returned.[65]

According to Halutz, the Israeli offensive in Lebanon had four major objectives: obtaining the release of the two kidnapped soldiers, "to remodel the security situation along the [Israeli-Lebanese] border and to prevent the Hezbollah from reaching Israeli territory," "to weaken the Hezbollah organization," and to get the "Lebanese government to exercise its sovereignty over its own [territory] and activities that emanate from its territory."[66]

Almost immediately after the abductions of the soldiers, IDF warplanes began bombing bridges, roads, and suspected Hezbollah positions.[67] While the first bombing raids appear to have focused on preventing Hezbollah from transferring the captured IDF soldiers away from the south by cutting off roads and other lines of communication, Israel soon launched a country-wide offensive against Hezbollah. On July 13, Israel imposed a total land, sea, and air blockade on Lebanon that would continue until September, well after the ceasefire began on August 14, 2006. Israeli warplanes bombed the runways and fuel tanks of Beirut's international airport on the grounds that the "airport is used as a central hub for the transfer of weapons and supplies to Hezbollah," and that the IDF wanted to prevent the transfer of the captured IDF soldiers to Iran or Syria.[68]