Curing the Selectivity Syndrome

The 2011 Review of the Human Rights Council

Introduction

In April 2006, the United Nations General Assembly created the Human Rights Council to promote the protection of human rights throughout the world. The Council replaced the discredited UN Commission on Human Rights, which had become a place, according to then Secretary-General Kofi Annan, where states sought membership “not to strengthen human rights but to protect themselves against criticism or to criticize others.”[1]

Resolution 60/251 of the General Assembly mandated the Council to:

· address situations of violations of human rights, including gross and systematic violations;

· contribute to the prevention of human rights violations; and

· respond promptly to human rights emergencies.

Four years later, despite this explicit mandate, the Council has failed to respond to a large majority of human rights crises and chronic situations of violations that need its attention, seriously calling into question its credibility. Although the Council was set up to be the UN’s main multilateral body focusing on human rights issues, it has been unable to make a difference in places such as Afghanistan, Guantanamo, Iran, Sri Lanka, Uzbekistan, and Zimbabwe. Most of the situations the Council has addressed are those inherited from the Commission, and even in those cases the Council’s response has often been weaker than its predecessor.

In order to fulfill its mandate and remain credible, the Human Rights Council needs to find a way to have a real impact on the lives of victims of human rights violations and to do so now.

The 2011 Review

When the General Assembly established the Human Rights Council (HRC) in 2006, it decided that the Council should review its work and functioning five years after its creation and report back to the General Assembly. The 2011 review provides a needed opportunity to reflect on the HRC’s achievements and failures, what it has done well, and what it can do better. It is an important moment for self-examination by the HRC and for an honest public appraisal of its performance.

The focus of the review should be to assess how the Council has implemented the mandate given to it by the General Assembly in Resolution 60/251. The General Assembly charged the Council with a broad mandate that includes the following areas of work:

1. Addressing situations of violations (operative paragraph 3);

2. Promoting effective coordination and mainstreaming of human rights within the UN system (OP. 3);

3. Promoting human rights education, learning, advisory services, technical assistance, and capacity building (OP. 5a);

4. Serving as forum for dialogue on thematic human rights issues (OP. 5b);

5. Making recommendations on the development of international human rights law (OP. 5c);

6. Promoting the implementation of states’ human rights obligations and commitments (OP. 5d);

7. Undertaking a universal periodic review of states’ fulfillment of their human rights obligations (OP. 5e);

8. Preventing violations and responding to emergencies (OP. 5f);

9. Assuming the role of the Commission on Human Rights in relation to the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OP. 5g);

10. Working in close cooperation with governments, regional organizations, national human rights institutions, and civil society (OP. 5h); and

11. Making recommendations for the promotion and protection of human rights (OP. 5i).

The Council has certainly performed some of these functions better than others. The 2011 review should focus on substantively improving the response of the Human Rights Council where it has underperformed. The review process should be directed at the identification of good practices and challenges with a view to making concrete proposals to improve the Council’s work and functioning. The review can also play a helpful role in improving the working culture at the Council.

There is an emerging consensus among UN member states that the review process should not be about renegotiating the Council’s institution-building package (HRC Resolutions 5/1 and 5/2). The institution-building package contains the details on the working methods, rules, and tools of the Human Rights Council and was painstakingly negotiated during the Council’s first year. Instead the review should build on the framework set forth in the institution-building package, and focus on where the Council has not performed adequately in key areas of work. Human Rights Watch joined a group of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) that has proposed structuring the 2011 review along the key areas of work of the Human Rights Council that were mandated by the General Assembly.[2]

Improving by Doing

Although the 2011 review provides an important moment for assessing the Council’s work and making needed improvements, states need not wait until 2011 to enhance its performance, particularly with regard to its response to human rights situations requiring the Council’s attention. The Council already has the mandate it needs to engage on more situations in a more meaningful way. Governments should explore new approaches in the coming months to enhance the Council’s work now, and those steps can feed into the review of the Council’s work. By “improving by doing,” the Council can illustrate a way forward through which the Council will be able to better fulfill its entire mandate.

As examples, the Human Rights Council could already undertake the following steps, all of which would make a real difference to those facing human rights abuses:

· Hold a briefing session on the human rights situation in Somalia involving UN agencies working in Somalia, the special representative of the UN secretary-general’s office, Somalia’s transitional federal government, NGOs, and other relevant actors who are working on the ground with the aim of improving and strengthening the international response to Somalia’s human rights situation in terms of protection, prevention, and accountability;

· Create a special rapporteur’s mandate on Afghanistan to independently monitor the deteriorating human rights situation in Afghanistan, and to recommend to the Human Rights Council ways and means of better responding to the human rights challenges in the country;

· Request Thailand to brief the HRC on the current human rights situation in the country and the status of investigations into abuses by all sides during the April-May 2010 violence in Bangkok;

· Call on the UN secretary-general to conduct an independent international inquiry into violations of international humanitarian law and human rights committed by all parties during the last months of the Sri Lankan war;

· Follow up on the commitment made by the government of Kyrgyzstan to ensure a prompt and independent investigation into the loss of lives during the uprising in April 2010 and appoint a commission of inquiry to support such efforts;

· Call on the United States to brief the HRC on its plans to close the detention center at Guantanamo Bay and possible ways of accelerating its closure;

· Call on the thematic special procedures to jointly report to the Council on the abuses committed in the context of post-electoral violence in Iran;

· Request the high commissioner for human rights to brief the Council on the current human rights situation in Guinea.

Double Standards and Selectivity

The greatest obstacle to the Council taking up its mandate more effectively is the disagreement among states about which situations should be addressed by the Council.

Human Rights Watch examined HRC members’ positions on a half-dozen key decisions relating to emergency or chronic situations from March 2009 to March 2010, including:

· Extending the mandate of the UN special rapporteur on the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea in 2009 and 2010;

· Strengthening a resolution on the Democratic Republic of the Congo;

· Continuing the expert mandate on Sudan;

· Blocking consideration of amendments to the special session resolution on Sri Lanka through a “no-action” motion;

· Referring the report of the UN Fact Finding Mission on the Gaza Conflict (the Goldstone report) to the General Assembly, the secretary-general, and other relevant UN entities; and

· Supporting the call for a special session on the human rights situation in Haiti in the aftermath of the January 2010 earthquake.

A table with the detailed results is contained in Appendix 2 of this report.

Analysis of these critical votes shows that Argentina and Chile were the most supportive of HRC engagement in the situations analyzed, and had the least “selective” approach. They supported affirmative Council action across the board in all country situations considered. They were followed by countries such as Bosnia-Herzegovina, Japan, France, and the United Kingdom, which supported action in most of the votes but did not favor referring the Goldstone report to the General Assembly. A number of Latin American and African countries also engaged positively on situations meriting the Council’s attention, including Mexico, Uruguay, Mauritius, Zambia, and Brazil, which shows that states from the Global South can be just as supportive of the Council’s full mandate as other “non-southern” states included in this group.

At the other end of the spectrum, Angola, Cameroon, Indonesia, and Gabon were the least supportive of engagement on country situations: they only supported action in one of the seven situations considered. The countries in this category have been some of the strongest critics of HRC selectivity and double standards, including countries such as Pakistan, Cuba, and Egypt. These countries consistently supported Council action relating to Israeli abuses in the Occupied Palestinian Territories, but were rarely supportive of country-specific action on other situations, arguing that addressing country situations in the HRC was inherently politicized and ought to be avoided. They contended that country-specific resolutions disproportionately targeted developing or less powerful nations. This approach has led to a weakening in the Council’s response to situations since its creation and has undermined its mandate.

On the other hand, there are a number of states, particularly from the West, that point to the Council’s efforts on Israel as the most glaring example of its selectivity. These states note that reticence over engaging on country situations has not extended to Israel, where dozens of resolutions relating to Israeli abuses have been brought under the Council’s separate agenda item on occupied Arab territories.

Given the Council’s explicit mandate to address situations of human rights violations, including gross and systematic violations, choosing to ignore such situations should not be an option. For states concerned about possible bias in addressing country situations, the question should not be whether the Human Rights Council should intervene, but rather how it can take on such situations in a manner that avoids selectivity and ensures that all situations in need of attention are covered. The 2011 review is an opportunity to address the allegations by all states that the response to concrete situations should not be selective. Meanwhile members of the HRC should strive to improve their own performance when it comes to voting or engaging on specific situations that are brought to the attention of the Council.

Building on Successful Experiences and Lessons Learned

Although there is reason to be critical of the HRC’s response to situations, there have been some positive experiences and lessons learned in the Council, which member states should build upon:

- The Universal Periodic Review (UPR) has demonstrated that a cooperative framework can be used to debate human rights situations and that resolutions are not the only way in the Council to address human rights problems. Although the UPR is an insufficient tool for responding to situations that require sustained or urgent engagement by the Council, some of the modalities used in the UPR could inspire more effective response by the Council to situations of concern.

- The UPR has also shown that the problem of selectivity and double standards can be tackled by developing a more universal approach to the examination of specific situations, rather than avoiding engagement altogether. With regard to situations of concern, this model shows that the best approach to counter selectivity would be for the Council to engage much more broadly, rather than to limit its engagement as is current practice.

- The use of independent commissions of inquiry, fact-finding missions, and expert groups by the Council has been a particularly effective and, at times, innovative approach. With regard to Darfur, the group of experts was mandated to monitor the implementation of recommendations already made to Sudan by UN bodies, putting the focus on practical implementation rather than just fact-finding or monitoring. The Goldstone inquiry proved the relevance of international inquiries even in settings where fact-finding on the ground is restricted, and showed the importance of impartiality and a comprehensive approach to such investigations.

- The Council’s increased use of thematic special procedures to take on work in particular country situations has also been notable. This practice illustrates the Council’s recognition that further engagement on such situations is needed, but places a considerable strain on the already limited resources available to thematic procedures.

- The public hearings organized during the Goldstone inquiry are a good example of victims and witnesses participating directly in the work of the Human Rights Council. The Council should focus on giving more visibility to the plight and voices of victims, and this is one of the tools it could use more in its future work.

Improving the Council’s Response to Situations of Violations of Human Rights

In order to move away from a model of engagement on situations that is perceived by some states as being antagonistic, selective, or inefficient, the Human Rights Council should consider three possible approaches to improving its response to human rights situations: 1) creating independent triggers for the consideration of situations by the Council; 2) ensuring broader coverage to lessen selectivity in the Council’s engagement; and 3) diversifying the Council’s toolbox. This approach builds on the positive experiences of the Council and tackles the issues of selectivity and double standards.

Creating Independent Triggers for the Consideration of Situations

The Human Rights Council should ensure that situations in all regions that need a response from the Council will get one. One way of doing this is to give appropriate institutions, officials, and independent experts the ability to trigger consideration of a situation by the Council. Creating independent triggers for the consideration of situations by the Council will enhance its preventive role and its capacity to react to emergency situations.

The authority to put forward issues for discussion could be extended to the president of the Human Rights Council, the secretary-general, the high commissioner for human rights, the General Assembly, the Security Council, and the special advisor to the secretary-general on the prevention of genocide. A group of five special procedures could also put forward an issue for discussion by putting forward a joint request, an approach that would strengthen the early-warning capacity of the Council’s special procedures.

Requests by any of these experts, officials, or institutions would automatically trigger a formal discussion of the situation. Giving the authority to put forward issues for discussion to a broad range of relevant actors will help ensure that no situations are immune from consideration by the Council, and would make it more likely that the full range of situations within the Council’s mandate are discussed.

Implementing this suggestion would involve expanding the authority that already exists under agenda item 1, by which a state or group of states could, in theory, request a discussion on a specific situation of concern under one of the agenda items of the Council’s program of work. To date, no state has tried to make such a request.

Avoiding Selectivity by Creating Regional Segments for Discussion of Situations

The Council could also decide to organize its discussions under item 4—the agenda item on situations that require the attention of the Council—differently. In particular, discussion under item 4 could be expressly divided into regional segments in order to ensure that situations in all regions are discussed. This idea borrows from the successful experience of the UPR, which has ensured broad and equal engagement on all situations.

The general debate under agenda item 4 could be divided into five half-day segments, covering each of the UN’s five geographic regions (Africa, Asia, Western Europe and Others, Latin America and Caribbean Countries, and Eastern Europe). Delegations would be invited to raise their concerns relating to specific situations in each of the regions under each of the regional headings, rather than trying to cover all issues under one generic agenda item, as is the current practice.

Discussions on specific situations (including those triggered automatically through request of the institutions or persons listed under the preceding section of this report) would be scheduled in addition to the regional segments under a separate segment within item 4.

Creating Regional Special Procedures

Taking the idea of regional segments under item 4 one step further, the Council could also decide to create working groups of independent experts for each of the five regions. Following the model of the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention and the Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances, the Council could appoint five independent experts (one from each region) to each regional working group. Like other special procedures, the mandate of these regional working groups would be to examine the situations in their specified region, report their findings to the Council, send communications and urgent appeals to governments concerning allegations of violations, carry out country visits and report their findings, issue media releases, report on trends and good practices, and provide advice and make recommendations on how to improve the human rights situations under their consideration.

Each of the working groups would report to the Council about their respective region under the designated segments within agenda item 4. The creation of the working groups should be seen as complementary to the work of country-specific mandates. Country mandates would be necessary where the Council agrees that specific reporting, advice, or monitoring by a special rapporteur or independent expert is needed. The regional working group could also make recommendations as to situations in which a country mandate would be helpful. When a country mandate exists, the regional working group would not need to address that situation in its work, although it could offer assistance and support to the country mandate.

Expanding and Diversifying the Toolbox

The HRC should adopt a new approach to addressing human rights situations that would allow for different levels of interaction, depending on the urgency and severity of the situation, the outcomes of previous discussions at the Council, and the willingness of the state involved to engage cooperatively with it. The main aim should be to ensure discussion of a broad range of human rights situations that might be helped by the Council’s engagement.

When discussing situations under its consideration, the Council should use an expanded range of responses. This more diverse toolbox would add a range of additional approaches that could be applied by the Council to respond to the very different situations it confronts. The options available to the Council could include traditional avenues such as resolutions and the creation of country-specific mandates, but would also entail a wide array of measures that would allow the Council to better tailor its response to the situation at hand, and to have a greater chance of having an impact on the ground.

Responses of the Council could include any of the following, several of which have been employed previously:

1. Holding a “briefing session” (called like a special session, but specifically intended as informational rather than aimed at a specific result or resolution);

2. Reaching an agreement on technical assistance needed to address the situation;

3. Sending a “letter of inquiry” to the concerned state from the HRC or the president of the Council;

4. Soliciting and receiving pledges from the concerned state regarding steps that it intends to take to address a situation under consideration;

5. Issuing a presidential statement on the situation;

6. Holding a specific discussion of the situation under agenda item 4;

7. Organizing a hearing with victims of a particular situation;

8. Requesting the high commissioner for human rights to brief the HRC on the situation;

9. Grouping special procedures’ reports relating to a specific situation together and considering them in an in-depth discussion;

10. Appointing an expert or group of experts to engage with a concerned government regarding its implementation of recommendations already issued by UN bodies, including the HRC.

The key to this approach is that the Council should not be bound to respond in a rigid way by either adopting a resolution or not. While Council debates—like those in its predecessor the Commission on Human Rights—have tended to be centered on resolutions, there is nothing in either General Assembly Resolution 60/251 or the institution-building package that limits the Council’s modes of engagement. The possible responses by the Council to various human rights situations have the ability to be as varied as the many different types of situations the Council confronts.

A combination of tools can also be considered. The principle should be that decisions of the Council could include positive measures designed to reinforce and encourage good practices, as well as criticisms of current practices and measures that are intended to act as a deterrent to further abuses. If a resolution is put forward, it could be held for additional discussion at an upcoming meeting of the Human Rights Council, should the government involved be cooperative and make commitments about the steps it will take to address the situation. If the situation on the ground continues to worsen and the government concerned does not cooperate in good faith, the Council could undertake a variety of additional measures, including, for example, holding a special session on the situation. The key to this approach is to use the full range of options available to the Council in a creative and flexible spirit, rewarding positive engagement by countries that do not deny a problem and show a willingness to engage. Such an approach should also give room for more assertive action where concerned states deny the violations or refuse to cooperate with the Council.

Enhancing the Universal Periodic Review

Overall, the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) has proven to be a useful mechanism for advancing the promotion and protection of human rights. Through the UPR, the Human Rights Council has examined country situations that are rarely spotlighted in international forums, and has shed light on human rights concerns in states with generally strong human rights performance where such issues would otherwise have been overlooked. The review has spurred governments to make needed human rights reforms and has led to meaningful changes on the ground. Most importantly, the UPR is a living embodiment of the principle that there are human rights issues that deserve discussion in all states, no matter what their level of development, their political system, or geographic region.

The UPR presents unprecedented advocacy opportunities at the international and national level for human rights supporters seeking to spotlight concerns and push for change. By allowing even non-accredited NGOs to submit information, the review has significantly expanded participation in the Council by domestic NGOs. The three reports that form the basis of the UPR bring together the different perspectives of the concerned government, the UN system, and other stakeholders, including civil society and national human rights institutions, and place their views of the human rights situation on record. The UPR has the potential to create space for national dialogue on key human rights challenges, especially in societies that have robust civil society, legislative, and media participation. Each UPR is different in terms of the opportunities and challenges it creates. The approach that a state takes to the UPR, including the level of civil society consultation, transparency, and its response to recommendations, says a great deal about the state’s commitment to human rights.

Strengths and Weaknesses of the Universal Periodic Review

The fact that the UPR is a shared experience for all governments in which all states both make and receive recommendations from their peers has been the main source of success of the UPR. This shared experience helps explain why the UPR has achieved 100 percent participation from all states undergoing review, which has not been the case for treaty body reporting. The UPR process has, in many cases, helped mobilize different departments or ministries within governments around the human rights agenda. As noted, the UPR has proven that it is possible for governments to discuss all kinds of human rights situations in a cooperative and collaborative environment. Another positive aspect of the UPR has been its accessibility through public webcast, and the fact that it is recorded and can be viewed at any time. This makes the process more transparent and allows for increased participation.

The UPR is not, however, a rigorous technical review of the human rights situation in a country. Unlike treaty bodies, which consider the detailed application of specific human rights obligations by a state party, the UPR only provides a general picture of the human rights situation in a country. Peer review cannot substitute for the expertise that treaty bodies and special procedures bring to bear upon a human rights situation, and states should bear in mind that the UPR should be a tool to help enforce existing recommendations by special procedures and treaty bodies, rather than compete with them.

The effectiveness of the UPR also depends on the willingness of states to respond to recommendations of their peers and undertake human rights reform. While the results of the UPR process are far from uniform, it is noteworthy that even some states without vibrant civil society or independent media have made significant commitments as part of the UPR. For example, Saudi Arabia agreed to abolish the guardianship system for women, and Vietnam pledged to limit the crimes for which the death penalty is applied. While these commitments are very significant, it remains to be seen whether they will be implemented, and there is no specific mechanism currently within the UPR to check on their implementation.

In other cases, the UPR has generated international attention concerning human rights concerns and helped support the calls for change at domestic levels. In the case of Mexico, for example, although the government did not agree to end military jurisdiction over human rights abuses committed by military personnel, the calls made by Mexican civil society for civilian jurisdiction for such abuses were echoed by many states’ recommendations during the UPR, increasing the pressure on the Mexican government to consider such reform.

Ensuring a Critical Assessment during the UPR

The quality of the UPR depends on critical but fair assessment by peers. In a number of cases, governments have been able to avoid such critical assessments by rallying the support of friendly governments eager to praise their human rights record without devoting any attention to the shortcomings that exist regarding human rights in all states. Stonewalling by devoting considerable time to such praise rather than focusing on human rights concerns undermines the main purpose of UPR, which is to improve the human rights situation on the ground.

The universal nature of the UPR process demands that all states should have equal opportunity to intervene in the UPR of a country and to hear the interventions of all states interested in speaking in their own review. Time should be managed flexibly to allow all states that wish to speak to do so. The UPR debate should be as long as necessary in order to ensure equal participation of all delegations. Human Rights Watch is supportive of proposals to extend the amount of time for discussion of each country situation, even if this requires lengthening the review cycle from four to five years. By allowing more time for discussion, the HRC could ensure that there is a proper interactive dialogue with the state under review, before proceeding to make recommendations.

Commitments Made by Governments during the UPR

An additional weakness of the UPR process to date has been the absence of clear responses by some states under review to recommendations made by their peers. Without such responses, the UPR cannot achieve its purpose of fostering tangible improvements in the protection of human rights. Failure by states to make clear commitments limits the HRC’s ability to measure or follow up progress on the ground. States that avoid responding to recommendations contravene the requirement of HRC Resolution 5/1, article 32, which states that recommendations that enjoy the support of the state under review will be identified and that other recommendations, together with the comments of the state, will be noted.

The 2011 review should address this failure and call on all states to abide by the rules they drafted for the UPR. Governments should be required to clearly state their positions regarding all recommendations.

Governments should also be required to indicate their responses to recommendations at least two weeks ahead of the adoption of the final report of the UPR. This would allow NGOs and delegations to make properly informed comments about the UPR process of the reviewed state during the adoption of the final report.

Bringing Expertise into the UPR

While the UPR has generally relied upon and incorporated international human rights standards, there are substantial concerns that some recommendations formulated by governments during the reviews have been inconsistent or contrary to international human rights norms. Furthermore the information compiled in the UN and stakeholders’ report containing a broad analysis of the situation and recommendations regarding the state under review does not bear enough prominence in the review process. The UN and stakeholders’ reports are not formally presented to the working group or the Human Rights Council at any stage of the review process. The wealth of recommendations and conclusions put forward by experienced independent mechanisms of the UN is therefore lost in this process, as is the assessment of independent civil society actors advocating for the improvement of human rights in their countries.

To address these concerns, the Human Rights Council could create a roster of independent experts or request the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) to provide its expertise during the process. The task of the experts or OHCHR would be to observe the whole of the review process and to present during the adoption of the final report of the UPR of the state under review.

As a rapporteur of the process, the expert would explain the different stages of the review, painting an overall picture of the main issues raised and the commitments made. The rapporteur would present the main elements of the UN and stakeholders’ reports, and would advise the HRC regarding recommendations that were inconsistent with human rights standards. The rapporteur’s comments would not alter the final report of the UPR, but would serve to bring together the different aspects of the process and add expertise helpful to both the state under review and the HRC itself.

Follow up and Universal Periodic Review

Another shortcoming of the UPR as currently implemented involves those situations where there is an obvious need for the Council to move from recommendations made by individual governments to a response by the Council as a whole. To date, the UPR has not triggered any further action by the Council as a whole, despite their being many situations discussed in the review that warrant more sustained action or examination by the Council. The UPRs of Afghanistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Sri Lanka are clear illustrations of this gap.

Agenda item 6, which covers the UPR, should have a section reserved for further consideration of initiatives arising from the UPR. This would allow for discussion of situations that the Council considers meriting more sustained engagement following the UPR. The section could include debates on proposals for technical cooperation arising from the review, discussions on the need for follow up and monitoring by the Council, or other proposals arising from the UPR, such as follow up on commitments to allow special procedures to visit the country.

Although many governments have voluntarily informed on the status of implementation of the commitments they made under the UPR, governments should be required to report on the status of implementation of their UPR commitments two years after their review was completed. This would create a formal basis for UPR follow up applicable to all countries. Creating a formal mechanism for follow up will help ensure that the focus of the UPR is as much on implementation and improving human rights on the ground as it is on reviewing and making recommendations and commitments.

Strengthening Special Procedures

The special procedures were initially created to provide the Commission on Human Rights and then its successor, the Human Rights Council, with independent, impartial, expert assessments of specific thematic issues or particular human rights situations.

Through their recommendations, the special procedures provide the Council with expert guidance on the application and interpretation of human rights standards, and on how to better protect human rights or prevent violations. The special procedures detect broad trends or threats to human rights, and provide early warning to the Council about emerging or deteriorating situations. In 2009 alone, special procedures mandate-holders conducted 73 fact-finding missions to 51 countries and issued 223 press releases and public statements.[3]

State Cooperation with Special Procedures

The special procedures system is premised upon the important role that independent expert voices can play in promoting and protecting human rights. The credibility of the special procedures arises from their ability to investigate and report on human rights situations in an impartial manner that is grounded in expertise and facts, rather than political views or opinions. Yet a number of governments have increasingly criticized the independence of special procedures and have sought to impose controls on the way special procedures interpret and implement their mandates. This approach could undermine both the work of the special procedures and the Council’s own credibility. While some oversight of the special procedures system may be warranted, it is essential for oversight functions to be impartial and not subject to influence by governments. Any approach that puts governments in an oversight position over the special procedures would politicize and damage the effectiveness of the special procedures system.

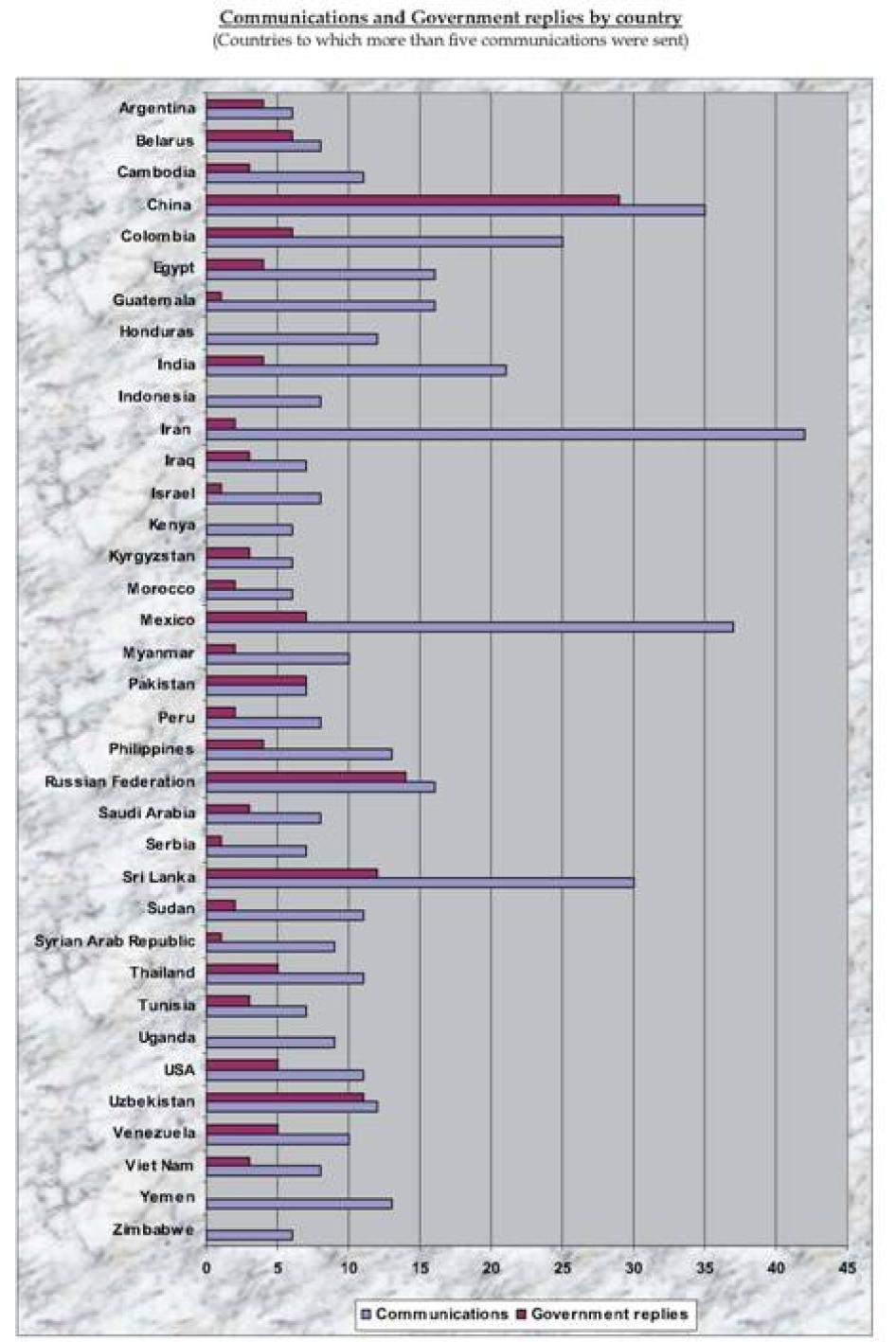

Human Rights Watch is also concerned that cooperation by states with the special procedures has in some cases declined, and that some governments use their demands for more oversight of the special procedures as a justification for non-cooperation. For a full breakdown of the status of replies to communications sent by special procedures in 2009, as well as statistics on state responses to special procedures’ requests to carry out country visits, see Appendices 3 and 4 of this report.

Governments that do not cooperate with special procedures are not held accountable by the Human Rights Council for that failure. The Council has not even taken steps to report on and respond to failures by its own members to cooperate with special procedures, despite General Assembly Resolution 60/251, which provides explicitly that members “shall fully cooperate with the Council.” The lack of cooperation by some governments compared to the substantial efforts of others to be transparent and to support the work of the special procedures puts an unequal burden on states. In order to ensure equity, governments that do not cooperate should be held to account.

Once a year, under agenda item 5 on human rights bodies and mechanisms, the Human Rights Council should address the status of cooperation with special procedures. The Council would invite the UN Secretariat to brief it on the number of communications sent by special procedures and the responses received by country and region. The Secretariat would also inform the Council of the status of visit requests by special procedures and provide information on the notes verbale sent to delegations in connection with specific studies or reports by special procedures and the responses received. An outcome document with a summary of the situation noting the extent of cooperation by states, including their comments, would be adopted by the Human Rights Council.

Effective Implementation of Standing Invitations

The Council should adopt a system to ensure that standing invitations to special procedures are effectively implemented.

Currently the practice of governments with standing invitations varies widely. Some governments effectively implement their standing invitation, while in other cases the standing invitation is virtually meaningless, as requests for visits go unanswered for many years. This divergence devalues standing invitations and is a disservice to governments that work diligently to implement such invitations.

Rather than grouping together all states that formally have standing invitations in place, the Council should delineate between states with effective standing invitations, and those without. For a standing invitation to be considered effective, the government making the invitation should respond to requests for visits by special procedures within six months and should actually schedule the visit within two years. Governments that do not meet these standards should be struck from the list of states that have issued standing invitations. In exceptional circumstances, special procedures could request an extension of time for a state to schedule a visit or respond to a request to visit.

Given that Council members should “fully cooperate” with the Council under General Assembly Resolution 60/251, all Council members should have an effective standing invitation in place. The Council should review the list of countries that have issued standing invitations during its discussion on cooperation with special procedures in agenda item 5.

Creating a Working Group of Standby Special Procedures

The important work of special procedures is constrained by their limited resources. On average, a special procedures mandate-holder can only carry out two country visits a year. Most special procedures have only one full-time and one half-time staff members within OHCHR to assist them with their respective mandates. This level of staffing and resources—particularly in the case of thematic procedures, which are expected to address their topics in all regions of the world—is clearly insufficient.

This shortage of resources is exacerbated when special procedures are over-tasked. Since the creation of the Human Rights Council, groups of thematic special procedures have been required to engage in specific situations of interest to the Council, such as the Democratic Republic of Congo, Darfur, and Gaza, in addition to their existing work plan.

This approach inherently diminishes the ability of the thematic procedures to address their core mandates, as additional resources are often not allocated for these further tasks. In addition, the availability of special procedures mandate-holders to undertake additional assignments is not boundless, given that they serve as unpaid experts who generally perform their mandates in addition to their regular employment. Yet, as the situations in Darfur, Gaza, and the Democratic Republic of Congo have shown, the Council often needs expert assistance to perform particular tasks on an urgent basis. Rather than overburden existing thematic special procedures in such circumstances, the Council should instead set up a working group of independent experts that would be ready to undertake on short notice specific tasks to be assigned at the Council’s discretion.

The standby experts group could be called upon to carry out fact-finding missions, examine specific situations of concern, or engage with governments regarding issues under consideration by the Council. Members of the group could be tasked with an assignment individually or as a group. Their assignments could focus on a particular thematic perspective in a given situation, or they could be asked to provide specific guidance on key issues. Putting in place a standby group of experts would greatly enhance the Council’s flexibility and ability to respond promptly to issues of concern. The Council would be able to consider at the completion of a task whether more sustained engagement or follow up was required.

Using the Recommendations Made by Special Procedures

Despite the detailed fact-finding and analysis provided to the Council by special procedures, the Human Rights Council usually receives their reports, but does not respond to or take action on the special procedures’ findings or recommendations, including those directed specifically at the Council itself.[4]This gap means that work commissioned by the Council is not as effective as it should be, and that the HRC’s impact is diminished. The HRC should do more to examine the findings and recommendations made by special procedures and to incorporate them into its work.

The interactive dialogues with special procedures provide an opportunity to examine the findings and recommendations contained in special procedures’ reports, but these discussions are only the first step. Following the interactive dialogues, the Council should include a segment within the same agenda item during which specific recommendations raised by the special procedures can be discussed, and proposals for follow up can be submitted. In addition, sponsors of resolutions relating to issues that have been addressed by special procedures should make a greater effort to build on the work of the special procedures.

Improving the Council’s Working Environment

One of the most important challenges for the 2011 review will be to consider how to improve the working environment of the Human Rights Council given the almost standing nature of the body.

The Council’s year-round engagement is a valuable asset. In theory it allows the Council to engage more promptly in new crises or rapidly evolving situations. It also provides space for a graduated approach to human rights situations in which concerns can be put forward in one session and addressed in subsequent sessions in a manner consistent with the concerned government’s response. At the same time, the HRC schedule has placed a huge burden on Geneva’s diplomatic missions, which has been particularly problematic for smaller missions. NGOs have also found the year-round schedule to be a double-edged sword, as they have more opportunities for advocacy, but few have the resources to participate in Geneva throughout the year.

The 2011 review should consider steps to make the work of the Human Rights Council more predictable, transparent, and inclusive. In particular, one proposal would be to develop a clear and accessible yearly calendar for the Council, including a list of resolutions and when they will be negotiated. In addition, the Council should adopt a rule requiring governments to circulate draft resolutions whenever possible at least four weeks ahead of Council sessions, in order to make the negotiation process more transparent and inclusive for delegations and NGOs alike. Resolutions relating to rapidly evolving or urgent situations would not be subject to the four-week rule.

Human Rights Watch is supportive of proposals aimed at managing the workload of the sessions of the HRC by dividing up the meeting times in more creative ways. Some proposals include separating the adoption of UPR reports from the main sessions of the Council into one comprehensive session in the autumn. Another proposal is to schedule the presentation of special procedures’ reports and interactive dialogues with special procedures in a predictable way throughout the year. Lastly Human Rights Watch is also interested in proposals aimed at reducing duplication in the HRC. One such proposal suggests merging the general debates of agenda items 3 (on promotion and protection of all human rights), 8 (on follow up to the Vienna Declaration on human rights), and 9 (on racism and discrimination) into one general debate on thematic issues; and merging the general debates of item 4 (situations that require the attention of the Council), item 7 (human rights in Palestine and the other occupied Arab territories), and item 10 (technical assistance and capacity building) into one general debate on situations and capacity-building. These general debates could each be structured into separate regional segments as suggested earlier in this report, in order to ensure a balanced and broader coverage of issues.

Support for Small Delegations

A fund should be created to help enable small and developing nations participate more fully at the Human Rights Council. The fund could be used to recruit junior professional officers to expand small delegations and allow for those missions to respond to the Council’s taxing year-round schedule.

Flexibility for Special Sessions

The Human Rights Council should consider allowing states requesting a special session to suggest extending the timeframe for the convening of the session. This modification would be consistent with the institution-building package, which states that “in principle” sessions should be held within five days. If the states requesting the session agree that the interests of the session would be best served by a later date, the HRC president should have the flexibility to respect their request. Such flexibility would be helpful, as the Council’s experience has shown that convening a special session with little notice can sometimes undermine its effectiveness. In particular, key actors are not always available to participate in sessions convened on short notice. For example, a number of development NGOs were unable to come to Geneva to attend the special session on the global food crisis, and special sessions focusing on country situations have taken place without the presence of activists from the country concerned, given the hurdles they face in arranging travel and obtaining visas.

Elections and Membership

The best way to promote a strong and effective membership in the Human Rights Council is to ensure that elections to the body are open and competitive. While regional groups have an important role in the elections process, they should not be able to put forward a predetermined slate of candidates for HRC membership that renders the elections process and standards agreed by the General Assembly in Resolution 60/251 meaningless. Measures to ensure competitive slates for all regions should be adopted as part of the 2011 review.

In addition, the HRC should create a mechanism to review and assess the level of cooperation of candidates and Council members with the Council itself and its special procedures. The group would present its assessment in advance of the annual HRC elections, as part of the debate under agenda item 5.

Summary of Recommendations

General

- The 2011 review of the Human Rights Council should focus on substantively improving the Council’s response to situations that have gone unattended. It should also lead to improvements in the quality of its deliberations and decisions on concrete situations. The 2011 review should prompt governments to shift away from selectivity and adopt a more objective approach to the situations that need the Council’s attention.

- The review need not revisit HRC Resolution 5/1 (the institution-building package) and should instead build on the foundation of the institution-building package to strengthen the HRC’s work.

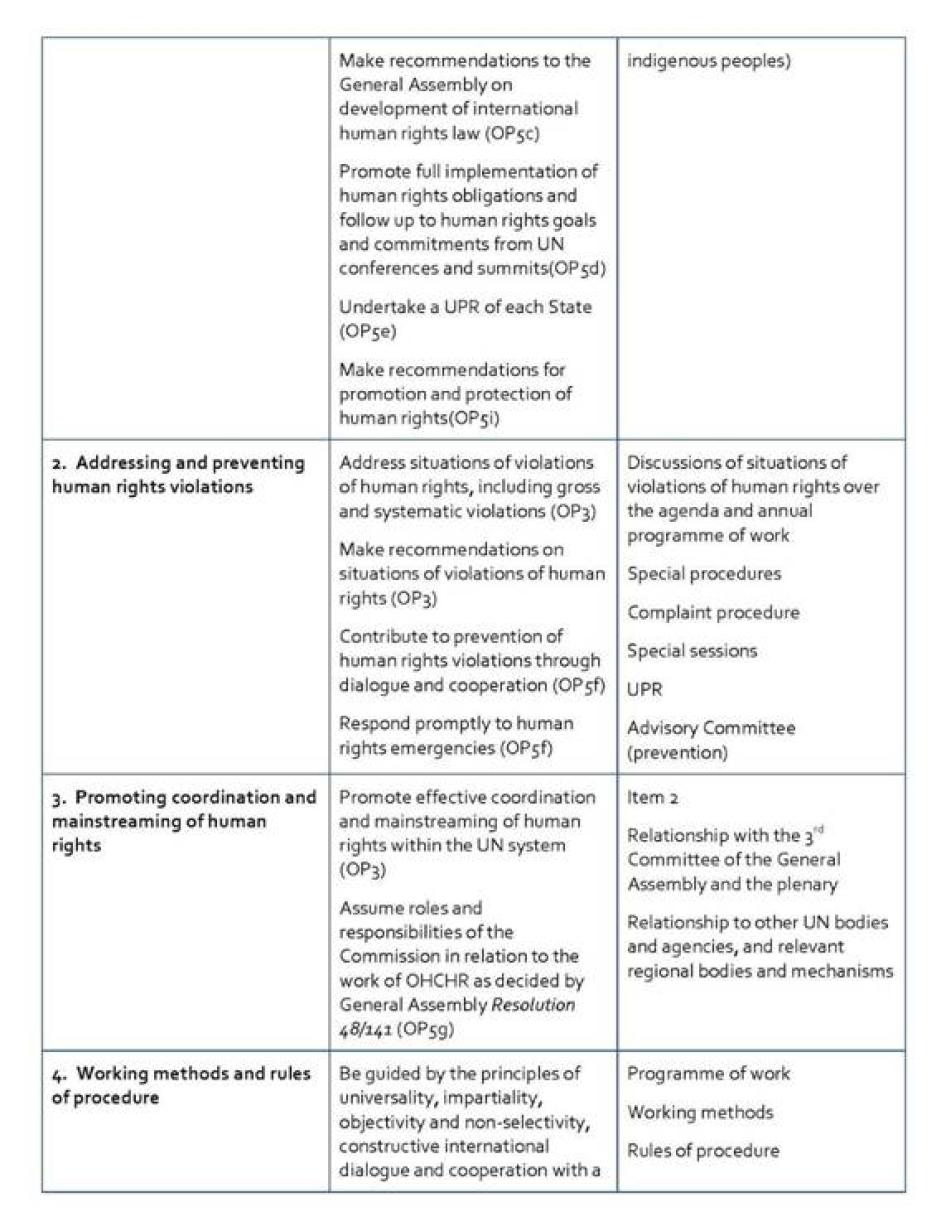

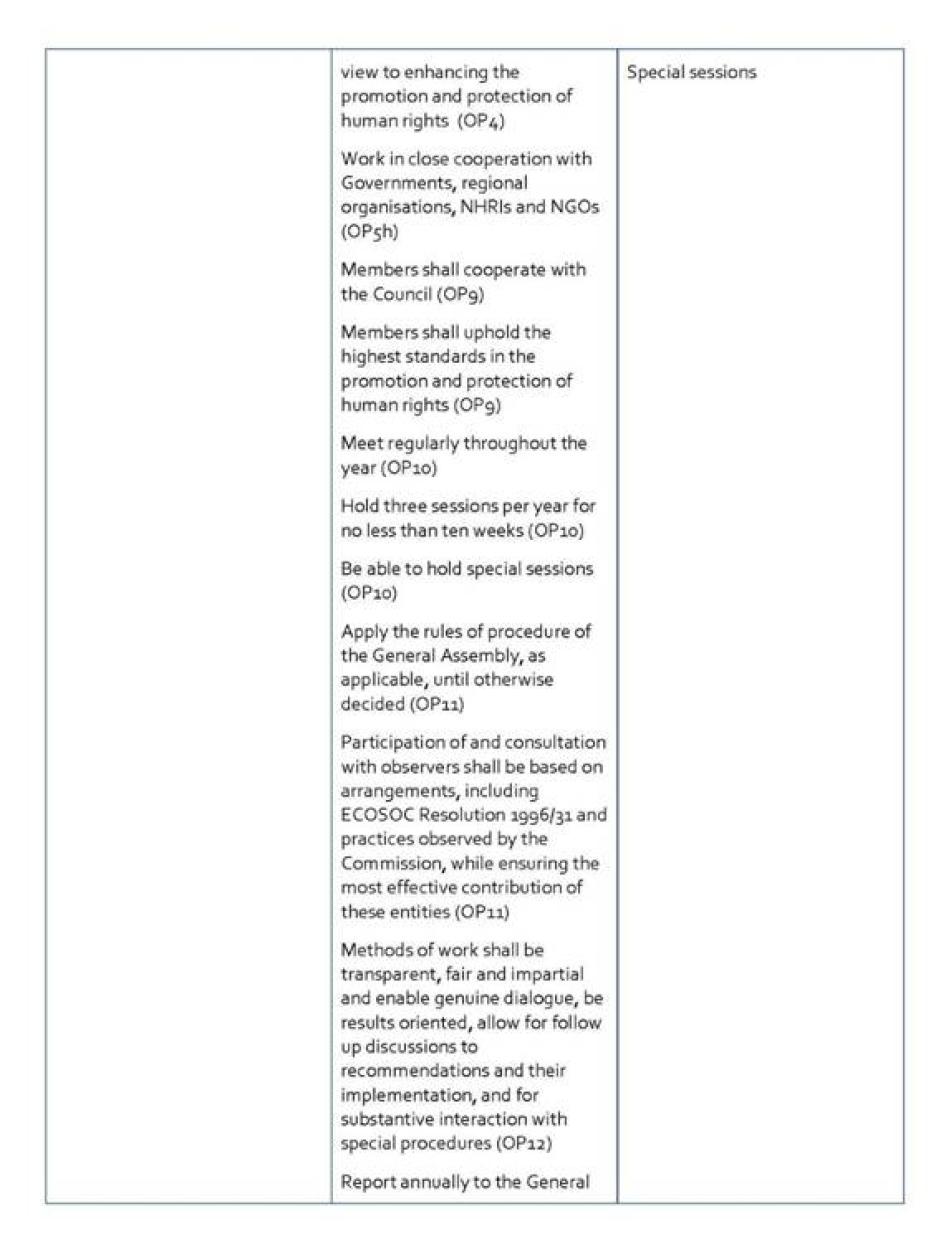

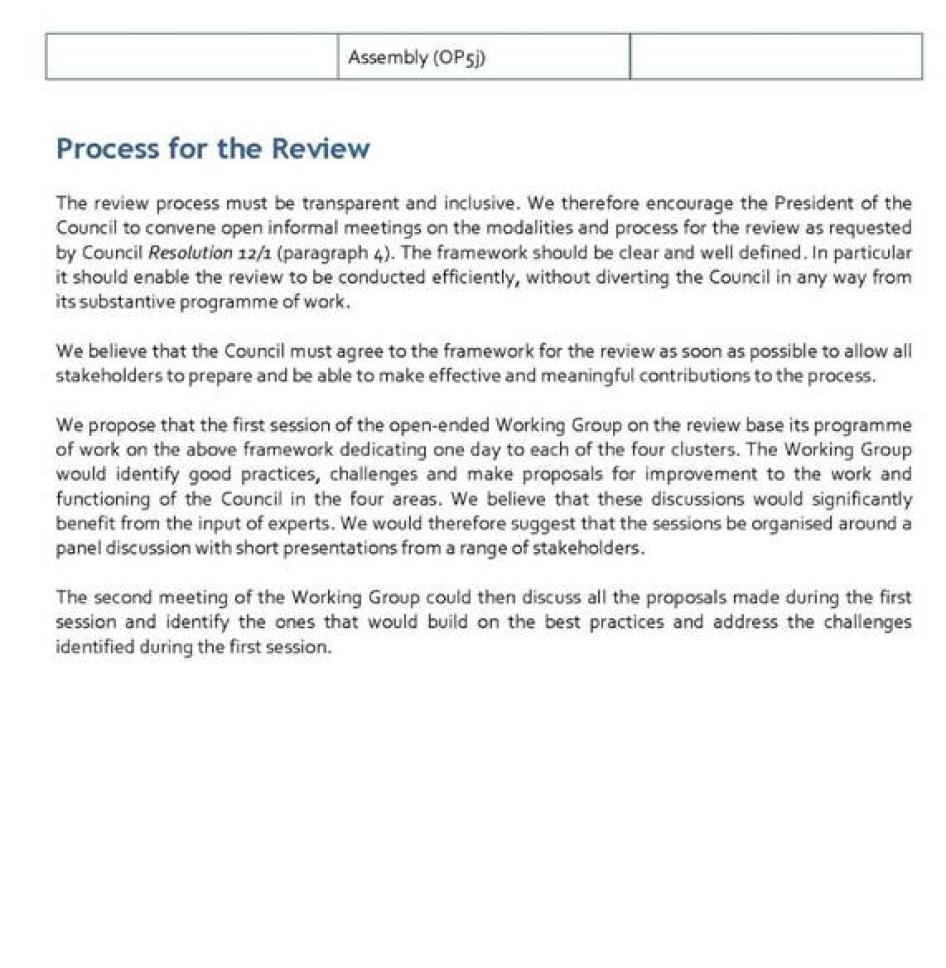

- The 2011 review should be structured around the areas of work and functions set forth for the HRC in General Assembly Resolution 60/251. The aim of the review should be to identify good practices and challenges in each of these areas of work and to make proposals for improvement based on this assessment.

- Improve by doing: the Council already has the mandate and many of the tools it needs to take on situations of ongoing human rights violations in a more meaningful way. Governments should be encouraged to improve the work of the Council by doing better during each of its sessions and not limit their efforts to the 2011 review process.

Improving the Council’s Response to Situations of Concern

- A new approach to addressing human rights situations should allow for less selectivity, broader engagement, and a more diversified response.

- The Council should create independent triggers for the consideration of situations.

- The general debate on situations that need the attention of the Council (item 4) should be divided into five regional segments.

- The Council should create five working groups of independent experts on situations, one for each of the regions represented at the Council.

- The Council should diversify the tools it uses to respond to situations of concern.

Universal Periodic Review

- All governments must participate on an equal footing in the UPR and be allowed to speak in a review if they so wish. Time arrangements should be flexible to meet the needs of all governments who need to participate in the review of a given country.

- The state under review should be required to state its position with respect to each UPR recommendation.

- Governments should be requested to respond to all UPR recommendations at least two weeks ahead of the adoption of the final report of the UPR, in order to allow delegations and NGOs to make properly informed comments during the adoption of the final report.

- Independent expertise should be brought into the UPR process by having experts (either appointed by the HRC or from within OHCHR) observe the review process and present a summary and analysis of the UPR during the adoption of the final report.

- The HRC’s agenda item on UPR (item 6) should have a section reserved for further discussion on situations that merit more sustained engagement following the UPR, including discussion of initiatives arising from the reviews.

- The Council should create a segment under agenda item 6 for follow up of each UPR. Governments should be required to report on the status of implementation of recommendations two years after their review was completed.

Special Procedures

- Once a year, under agenda item 5 on human rights bodies and mechanisms, the Human Rights Council should discuss the cooperation of states with special procedures based on factual information provided by the Secretariat.

- An outcome document summarizing the extent of cooperation by states with special procedures, including their comments, should be adopted by the Council once a year. Special attention should be paid to the status of cooperation of member states of the Council and candidates for election to the body.

- The Council should adopt a monitoring system to ensure that standing invitations are effectively implemented. States that fail to implement their standing invitations should be removed from the list of countries that have standing invitations.

- The Council should set up a working group of independent experts on standby to carry out tasks mandated by the Council in the context of its response to situations of concern.

- The early-warning function of the special procedures should be strengthened by allowing a group of at least five special procedures to trigger the automatic consideration of a situation of concern by the Council.

- The Council should discuss specific proposals and recommendations arising from special procedures’ reports that require follow up.

- Sponsors of country-specific resolutions should consider recommendations formulated by special procedures when drafting resolutions focusing on specific issues and situations addressed by the special procedures.

Improving the Working Environment in the Council

- A fund to support small delegations from developing nations should be created to allow those states to participate more actively in the Human Rights Council.

- A yearly calendar of resolutions should be made available to all delegations and NGOs, so that negotiations are more predictable, and planning is strengthened.

- The Council should also create a rule requiring governments to circulate draft resolutions at least four weeks ahead of the main sessions of the Council whenever possible. Resolutions relating to rapidly-evolving or urgent situations would not be subject to this rule.

- The Council should allow the group of states requesting a special session to request, on an exceptional basis, an extension of the timeframe for the convening of the session.

Elections and Membership

- The 2011 review should consolidate and strengthen the competitive nature of the HRC election process.

- The Council should create a mechanism to review and assess, on an annual basis, the state of cooperation with the HRC and the special procedures of candidates for HRC membership and member states of the Council.

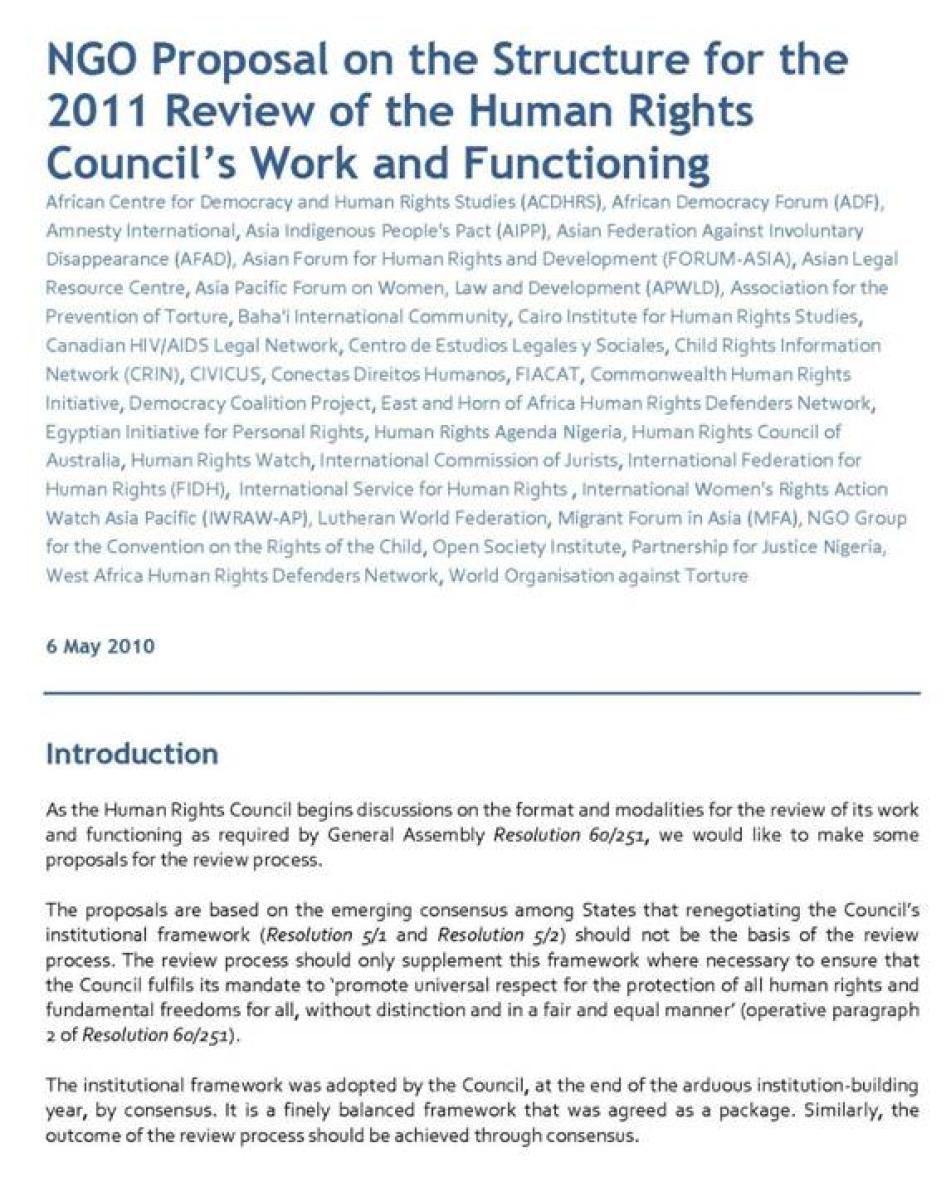

Appendix 1: NGO Proposal on the Structure for the 2011 Review of the Human Rights Council’s Work and Functioning

Appendix 2: Action Taken on Country Resolutions from March 2009 (HRC10) to March 2010 (HRC13)

ACTION TAKEN ON COUNTRY RESOLUTIONS FROM MARCH 2009 (HRC10) TO MARCH 2010 (HRC13) | |||||||

|

RES/10/16 |

RES/10/33 |

RES/11/10 |

RES/S-11/1 |

RES/S-12/1 |

SS-13 |

RES/13/14 |

|

DPRK |

DRC amend. |

Sudan amend. |

Sri Lanka non-action motion |

Goldstone |

Haiti |

DPRK |

Country* |

Vote |

Vote |

Vote |

Vote |

Vote |

Support call |

Vote |

Argentina |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

Chile |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

Bosnia & Herzegovina |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

O |

✔ |

✔ |

France |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

O |

✔ |

✔ |

Japan |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

O |

✔ |

✔ |

Republic of Korea |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

O |

✔ |

✔ |

Mexico |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

O |

✔ |

✔ |

Slovenia |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

O |

✔ |

✔ |

UK |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

O |

✔ |

✔ |

Uruguay |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

O |

✔ |

✔ |

Italy |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✘ |

✔ |

✔ |

Slovakia |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✘ |

✔ |

✔ |

Mauritius |

✔ |

O |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

✔ |

Netherlands |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✘ |

|

✔ |

Ukraine |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

O |

✘ |

✔ |

✔ |

Zambia |

✔ |

O |

✔ |

O |

✔ |

|

✔ |

Brazil |

O |

O |

✔ |

O |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

Jordan |

✔ |

O |

✘ |

O |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

Ghana |

✔ |

O |

O |

✘ |

✔ |

|

✔ |

Bahrain |

✔ |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

Saudi Arabia |

✔ |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

Nicaragua |

O |

✔ |

O |

✘ |

✔ |

✔ |

O |

Burkina Faso |

✔ |

O |

O |

✘ |

O |

✔ |

✔ |

Djibouti |

O |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

Senegal |

O |

O |

O |

O |

✔ |

✔ |

O |

Bolivia |

O |

O |

O |

✘ |

✔ |

✔ |

O |

Nigeria |

✘ |

✘ |

O |

O |

✔ |

✔ |

O |

India |

O |

✘ |

O |

✘ |

✔ |

✔ |

O |

Madagascar |

✔ |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

O |

|

✔ |

Pakistan |

O |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

✔ |

✔ |

O |

Philippines |

O |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

✔ |

✔ |

O |

Qatar |

O |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

✔ |

✔ |

O |

South Africa |

O |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

✔ |

✔ |

O |

Bangladesh |

O |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

✔ |

|

O |

China |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

✔ |

✔ |

✘ |

Cuba |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

✔ |

✔ |

✘ |

Egypt |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

✔ |

✔ |

✘ |

Russian Federation |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

✔ |

✔ |

✘ |

Gabon |

O |

✘ |

✘ |

O |

O |

✔ |

O |

Cameroon |

✔ |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

O |

|

O |

Angola |

O |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

O |

✔ |

O |

Indonesia |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

✔ |

|

✘ |

Countries that are no longer Council members |

RES/10/16 |

RES/10/33 |

RES/11/10 |

RES/S-11/1 |

RES/S-12/1 |

SS-13 |

RES/13/14 |

DPRK |

DRC amend. |

Sudan amend. |

Sri Lanka non-action motion |

Goldstone |

Haiti |

DPRK |

|

Vote |

Vote |

Vote |

Vote |

Vote/ position |

Support call |

Vote |

|

Switzerland |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

✔ |

|

Canada |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

✔ |

|

Germany |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

|

|

Azerbaijan |

O |

✘ |

O |

O |

|

|

|

Malaysia |

O |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

|

|

|

*Excluding current member states of the HRC that joined in June 2009 (Belgium, Hungary, Kyrgyzstan, Norway, USA)

Appendix 3: Communications and Government Replies by Country

Source: OHCHR, “UN Special Procedures: Facts and Figures 2009,” undated, http://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/chr/special/docs/Facts_Figures2009.pdf (accessed June 14, 2010), p. 9.

Appendix 4: Special Procedures’ Country Visits

Country (years of HRC membership) |

Standing invitation |

Pending visit requests |

Visits since June 2006 and forthcoming |

Visits agreed upon in principle |

Afghanistan |

N |

3 |

2 |

0 |

Albania |

Y |

1 |

0 |

1 |

Algeria (2006-2007) |

N |

5 |

1 |

1 |

Angola (2007-2010) |

N |

1 |

2 |

3 |

Argentina (2006-2011) |

Y |

6 |

1 |

1 |

Armenia |

Y |

1 |

0 |

2 |

Australia |

Y |

0 |

3 |

1 |

Azerbaijan (2006-2009) |

N |

2 |

3 |

1 |

Bahrain (2006-2011) |

N |

1 |

1 |

0 |

Bangladesh (2006-2012) |

N |

8 |

1 |

2 |

Belarus |

N |

4 |

1 |

0 |

Benin |

N |

0 |

1 |

0 |

Bhutan |

N |

2 |

0 |

0 |

Bolivia (2007-2010) |

Y |

1 |

2 |

3 |

Bosnia and Herzegovina (2007-2010) |

N |

0 |

4 |

1 |

Botswana |

N |

1 |

1 |

0 |

Brazil (2006-2011) |

Y |

2 |

5 |

0 |

Bulgaria |

Y |

2 |

0 |

2 |

Burkina Faso (2008-2011) |

N |

0 |

1 |

1 |

Burundi |

N |

4 |

3 |

0 |

Cambodia |

N |

5 |

2 |

0 |

Cameroon (2006-2012) |

N |

0 |

0 |

1 |

Canada (2006-2009) |

Y |

3 |

2 |

1 |

Central African Republic |

N |

1 |

3 |

1 |

Chad |

N |

4 |

1 |

0 |

Chile (2008-2011) |

Y |

2 |

2 |

2 |

China (2006-2012) |

N |

9 |

0 |

2 |

Colombia |

Y |

5 |

8 |

0 |

Congo |

N |

0 |

0 |

1 |

Costa Rica |

Y |

0 |

1 |

0 |

Cote d'Ivoire |

N |

2 |

1 |

0 |

Croatia |

Y |

0 |

1 |

1 |

Cuba (2006-2012) |

N |

2 |

1 |

1 |

Democratic People's Republic of Korea |

N |

4 |

0 |

0 |

Democratic Republic of the Congo |

N |

1 |

6 |

0 |

Denmark |

Y |

1 |

1 |

0 |

Dominican Republic |

N |

1 |

1 |

0 |

Ecuador (2006-2007) |

Y |

2 |

6 |

0 |

Egypt (2007-2010) |

N |

7 |

3 |

1 |

El Salvador |

N |

1 |

2 |

1 |

Equatorial Guinea |

N |

1 |

2 |

1 |

Eritrea |

N |

4 |

0 |

0 |

Estonia |

Y |

0 |

2 |

0 |

Ethiopia |

N |

8 |

1 |

0 |

Fiji |

N |

2 |

1 |

0 |

Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia |

Y |

1 |

2 |

0 |

France (2006-2011) |

Y |

1 |

1 |

0 |

Gabon (2006-2011) |

N |

1 |

0 |

0 |

Gambia |

N |

3 |

0 |

0 |

Georgia |

N |

2 |

3 |

1 |

Germany (2006-2009) |

Y |

0 |

1 |

0 |

Ghana (2006-2011) |

Y |

3 |

1 |

0 |

Greece |

Y |

0 |

2 |

0 |

Guatemala (2006-2008) |

Y |

1 |

10 |

0 |

Guinea |

N |

0 |

0 |

1 |

Guinea-Bissau |

N |

2 |

0 |

0 |

Guyana |

N |

0 |

1 |

0 |

Haiti |

N |

0 |

7 |

1 |

Holy See |

N |

1 |

0 |

0 |

Honduras |

N |

0 |

3 |

1 |

Hungary (2009-2012) |

Y |

0 |

1 |

0 |

India (2006-2010) |

N |

10 |

3 |

0 |

Indonesia (2006-2010) |

N |

9 |

3 |

1 |

Iran |

Y |

4 |

0 |

3 |

Iraq |

N |

4 |

0 |

2 |

Ireland |

Y |

1 |

0 |

0 |

Israel |

N |

5 |

3 |

2 |

Italy (2007-2010) |

Y |

1 |

2 |

1 |

Jamaica |

N |

1 |

1 |

0 |

Japan (2006-2011) |

N |

2 |

4 |

0 |

Jordan (2006-2012) |

Y |

1 |

1 |

0 |

Kazakhstan |

Y |

0 |

2 |

1 |

Kenya |

N |

5 |

4 |

0 |

Kuwait |

N |

1 |

0 |

0 |

Kyrgyzstan (2009-2012) |

N |

3 |

2 |

0 |

Lao People's Democratic Republic |

N |

2 |

1 |

0 |

Latvia |

Y |

0 |

2 |

0 |

Lebanon |

N |

1 |

2 |

0 |

Liberia |

N |

6 |

3 |

0 |

Libyan Arab Jamahiriya |

N |

1 |

0 |

2 |

Lithuania |

Y |

0 |

1 |

0 |

Madagascar (2007-2010) |

N |

0 |

0 |

1 |

Malawi |

N |

2 |

0 |

0 |

Malaysia (2006-2009) |

N |

8 |

1 |

1 |

Maldives |

Y |

1 |

4 |

1 |

Mali (2006-2008) |

N |

0 |

0 |

1 |

Malta |

Y |

0 |

1 |

0 |

Marshall Islands |

N |

1 |

0 |

0 |

Mauritania |

N |

1 |

3 |

2 |

Mauritius (2006-2012) |

N |

1 |

0 |

1 |

Mexico (2006-2012) |

Y |

1 |

2 |

6 |

Moldova |

N |

0 |

1 |

0 |

Mongolia |

Y |

0 |

3 |

0 |

Morocco (2006-2007) |

N |

1 |

2 |

1 |

Mozambique |

N |

3 |

0 |

0 |

Myanmar |

N |

5 |

4 |

0 |

Namibia |

N |

1 |

0 |

0 |

Nauru |

N |

1 |

0 |

0 |

Nepal |

N |

8 |

1 |

0 |

Netherlands (2006-2010) |

Y |

0 |

2 |

0 |

Nicaragua (2007-2010) |

Y |

5 |

1 |

1 |

Nigeria (2006-2012) |

N |

4 |

1 |

4 |

Norway (2009-2012) |

Y |

0 |

2 |

0 |

Oman |

N |

0 |

1 |

1 |

Pakistan (2006-2011) |

N |

7 |

0 |

0 |

Palestine & OPT |

N |

0 |

4 |

3 |

Panama |

N |

1 |

0 |

0 |

Papua New Guinea |

N |

3 |

1 |

0 |

Paraguay |

Y |

1 |

3 |

1 |

Peru (2006-2008) |

Y |

5 |

2 |

1 |

Philippines (2006-2010) |

N |

9 |

1 |

2 |

Poland (2006-2007) |

Y |

0 |

2 |

0 |

Qatar (2007-2010) |

N |

0 |

1 |

0 |

Republic of Korea (2006-2011) |

Y |

0 |

5 |

1 |

Romania (2006-2008) |

Y |

3 |

1 |

0 |

Russian Federation (2006-2012) |

N |

7 |

4 |

2 |

Rwanda |

N |

1 |

0 |

0 |

Saudi Arabia (2006-2012) |

N |

6 |

1 |

0 |

Senegal (2006-2012) |

N |

1 |

3 |

3 |

Serbia |

Y |

1 |

3 |

0 |

Serbia and Montenegro |

Y |

1 |

0 |

0 |

Seychelles |

N |

1 |

0 |

0 |

Sierra Leone |

Y |

4 |

0 |

1 |

Singapore |

N |

2 |

2 |

0 |

Slovenia (2007-2010) |

Y |

0 |

1 |

0 |

Somalia |

N |

1 |

3 |

0 |

South Africa (2006-2010) |

Y |

3 |

3 |

1 |

Spain |

Y |

2 |

2 |

1 |

Sri Lanka (2006-2008) |

N |

6 |

4 |

0 |

Sudan |

N |

5 |

6 |

2 |

Swaziland |

N |

1 |

0 |

0 |

Sweden |

Y |

0 |

1 |

0 |

Syrian Arab Republic |

N |

2 |

0 |

0 |

Tajikistan |

N |

0 |

2 |

1 |

Tanzania |

N |

2 |

1 |

1 |

Thailand |

N |

9 |

1 |

1 |

Timor Leste |

N |

2 |

1 |

0 |

Togo |

N |

0 |

2 |

1 |

Trinidad and Tobago |

N |

1 |

0 |

0 |

Tunisia (2006-2007) |

N |

4 |

1 |

0 |

Turkey |

Y |

4 |

2 |

1 |

Turkmenistan |

N |

9 |

1 |

0 |

Uganda |

N |

1 |

2 |

1 |

Ukraine (2006-2011) |

Y |

0 |

4 |

0 |

United Arab Emirates |

N |

2 |

2 |

0 |

UK (2006-2011) |

Y |

0 |

3 |

0 |

USA (2009-2012) |

N |

5 |

7 |

1 |

Uruguay (2006-2012) |

Y |

0 |

2 |

1 |

Uzbekistan |

N |

8 |

0 |

0 |

Venezuela |

N |

3 |

0 |

0 |

Vietnam |

N |

5 |

2 |

1 |

Yemen |

N |

2 |

0 |

2 |

Zambia (2006-2011) |

Y |

2 |

1 |

0 |

Acknowledgements

This report was researched and written by Juliette de Rivero, Geneva advocacy director, with additional contributions by Philippe Dam, Human Rights Council advocate. It was edited by Peggy Hicks, global advocacy director, and James Ross, legal and policy director.

Human Rights Watch interns Jennifer Carl, Sheherezade Kara, Madeleine Koalick, Estelle Nkounkou Ngongo, and Ellen Walker, and Klatsky fellow Katharine Quaglieri provided invaluable research and editorial support. Editorial and production assistance were provided by Judit Costa and Adrianne Lapar, associates in the advocacy division. Grace Choi, publications director, and Fitzroy Hepkins, mail manager, prepared the report for publication.

[1] UN Secretary-General, “In Larger Freedom: Towards Development. Security and Human Rights for All,” March 21, 2005, A/59/2005, http://documents.un.org/ (accessed June 14, 2010).

[2]African Centre for Democracy and Human Rights Studies et al., “NGO Proposal on the Structure for the 2011 Review of the Human Rights Council’s Work and Functioning,” May 6, 2010. See Appendix 1 of this report.

[3]OHCHR, “UN Special Procedures: Facts and Figures 2009,” undated, http://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/chr/special/docs/Facts_Figures2009.pdf (accessed June 14, 2010), pp. 10 and 19.

[4]Ibid. In 2009 the special procedures mandate-holders submitted 136 reports to the Human Rights Council, including 47 annual reports and 51 reports on country visits.