All Quiet on the Northern Front?

Uninvestigated Laws of War Violations in Yemen’s War with Huthi Rebels

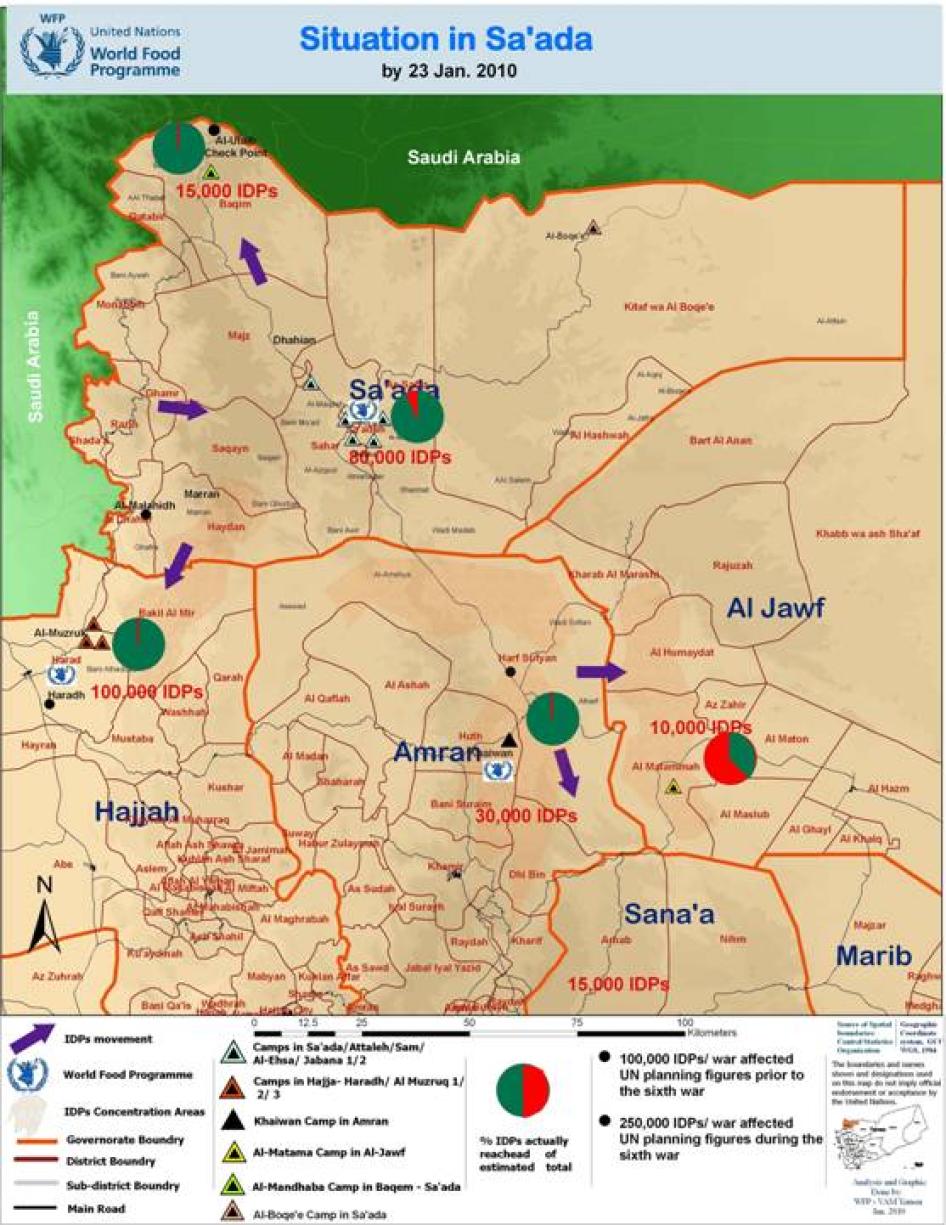

Map of Yemen’s Northern Governorates

Map provided courtesy of the UN World Food Programme; situation as of January 23, 2010.

Summary

On February 12, 2010, Yemen’s government and rebel Huthi forces agreed on a truce that ended the sixth round of fighting in a five-year-long war that has devastated the lives of hundreds of thousands of people in northern Yemen.

The elements of this shaky truce—the sixth in almost as many years—do not include investigations into alleged violations of the laws of war, including indiscriminate attacks, summary executions, and use of child soldiers. The continuing failure of both the Yemeni government and the Huthi rebels to investigate alleged violations by their forces prevents perpetrators from being held to account, denies compensation to victims of abuses, and complicates efforts to reach a long-term political settlement.

Since mid-August 2009— the beginning of the war’s “sixth round”—artillery shelling by both sides and government aerial bombardments have killed hundreds of civilians, injured untold more, and destroyed entire villages. In early November 2009 Saudi Arabia entered the war, sending fighter planes into Yemeni airspace to bomb rebel positions. By mid-February 2010, international aid agencies were struggling to regularly assist a small fraction of the 265,000 people, mostly women and children, displaced from their homes in this and earlier rounds of fighting.

Although the most recent fighting has attracted greater international attention—including the United Nations’ first-ever joint aid appeal to assist civilians displaced by the war—the international community has largely remained on the sidelines. There has been no perceptible effort within the UN or other intergovernmental bodies to monitor and press for the parties’ adherence to international humanitarian law (the laws of war) and to urge more effective protection of the civilian population.

This report is based on interviews conducted in Yemen in late October 2009 with civilians affected by the conflict and humanitarian aid workers. It documents incidents of possible violations of the laws of war by both sides. Because of lack of access to the conflict area, further investigations are needed to obtain a clearer picture of alleged abuses.

The five-year-old conflict has gone through six main rounds of fighting, with low-intensity conflict filling the gaps. The fifth round ended in July 2008. Increasingly frequent clashes began again in March 2009 and the sixth and latest round erupted on August 12, 2009. A ceasefire ending the sixth round was declared on February 11, 2010.

The political aims of the Huthi rebels are not clear. The group originated as a religious movement—the “Believing Youth” (al-shabbab al-mu’min)—in the mid-1990s, mainly to promote religious education in Sa’da governorate. Yemenis in Sa’da overwhelmingly follow the Zaidi branch of Shia Islam, and Zaidis had ruled large parts of Yemen for a thousand years under a religiously legitimized imamate until 1962, when a military-led coup eventually ushered in republican rule. The current Yemeni president, Ali Abdullah Saleh, is a Zaidi, but the Huthis object to what they say is the government’s failure to end Saudi-inspired Sunni Islamic missionary activities in Sa’da, which they say clash with traditional Zaidi doctrine.

Government forces included regular military units as well as tribal militias who fight alongside government troops or on their own in defense of their villages. Government forces have maintained a significant military advantage over the Huthis primarily through airpower; otherwise both sides have relied on small arms and artillery.

In 2008 the conflict spread beyond Sa’da governorate into ‘Amran, Hajja, and Jawf governorates, and in June 2008 briefly reached Bani Hushaish, on the outskirts of Yemen’s capital, San’a. In November 2009, following what it said was a cross-border raid on its territory, Saudi Arabia engaged the Huthis in sustained hostilities, including airstrikes, and established a “buffer zone” inside Yemen along the Saudi border.

By mid-February 2010, international aid agencies struggled to assist just over 45,000 displaced civilians (17 percent of the total number of those displaced) seeking refuge in seven camps and nine informal settlements. Due to a combination of insecurity inside the conflict area and governmental obstruction of aid activity outside formally approved camps, agencies faced even greater obstacles in trying to assist a further 218,000 displaced persons living with host families or in public buildings and open spaces. The plight of the displaced has been exacerbated by Saudi Arabia’s preventing Yemenis from seeking refuge across the border in Saudi Arabia and their forcing of refugees back across the border into Yemen, in violation of international law.

In September 2009, for the first time since the war began, international agencies, including the United Nations, the International Committee of the Red Cross, and international non-governmental humanitarian organizations, all regularly issued media statements to highlight the plight of displaced civilians, and launched the first-ever joint aid appeal—for US $23.75 million—to address their needs. In December 2009, the UN issued its first Comprehensive Humanitarian Response Plan for Yemen for $177 million in 2010—tens of millions of which were to help civilians affected by the war. However, by early February, the UN reported that governments had donated only $767,000 (0.4 percent of the appeal), threatening an aid crisis.

On February 11, after weeks of disagreements between the parties over its terms, President Saleh announced a unilateral ceasefire—to which the Huthis agreed.

Despite the international humanitarian community’s increased involvement, by the end of 2009 the response of the United Nations and key states to the conflict could best be characterized as apathetic. The UN failed to follow up its call for a government investigation into airstrikes that on September 16 reportedly killed over 80 civilians, mostly women and children. A government-commissioned local inquiry shed little light on the incident.

Donor governments and the United Nations have failed to push for independent international mechanisms to monitor parties’ conduct of the war and to insist on accountability for serious violations of the laws of war. At a high-level meeting on Yemen in London in January 2010, UK Foreign Secretary David Miliband, “committ[ed] to non-interference in Yemen’s internal affairs.” Prior to the meeting, Yemen’s diplomats had been lobbying against any “internationalization” of what they regarded as Yemen’s internal issues, including the armed conflict with the Huthi rebels and the southern secessionist movement. However, given the inability of independent media to access the war zone to cut through government and rebel propaganda, and the government’s continued blocking of mobile telephone access in the conflict areas, independent monitoring mechanisms are all the more urgent.

Human Rights Watch spoke with internally displaced persons (IDPs) who witnessed fighting in seven districts of Sa’da and ‘Amran governorates: Malahit, Dhahir, Haidan, Saqain, Majz, Sa’da, and Harf Sufyan. Incidents described raised possible laws of war violations by both sides that require further investigation.

Government forces carried out airstrikes on Huthi forces in or near populated villages in which insufficient precautions may have been taken to minimize civilian casualties and loss of property. In some instances, these attacks may have been indiscriminate or disproportionate, which are serious violations of the laws of war.

Gathering information on alleged Huthi laws-of-war violations was hindered by lack of access to the conflict area. Huthi forces may have at times placed civilians at unnecessary risk by deploying within densely populated villages. Displaced persons reported two cases of possible summary killings by Huthi forces. On several occasions the Huthis allegedly prevented injured civilians from leaving their village to obtain necessary medical care in larger towns. There were also eyewitness accounts of rebels pillaging private property.

Human Rights Watch spoke to three youths who described fighting for government or Huthi forces as child soldiers, in violation of international law.

Human Rights Watch urges both government forces and Huthi rebels to promptly investigate reports of abuses by their own forces and punish as appropriate those responsible. The recruitment and use of child soldiers should be ended immediately. The organization urged that both parties permit and facilitate access by humanitarian organizations to persons in need. In any intermittent or future hostilities, both parties should abide by their obligations under international humanitarian law. In particular, they should take all feasible precautions to minimize harm to the civilian population.

Concerned governments should press the Yemeni government to allow UN agencies and independent monitors access to the conflict zone and should place meaningful pressure on both sides to respect the laws of war.

Recommendations

To the Government of Yemen

- Investigate allegations of laws-of-war violations by Yemeni forces, and discipline or prosecute as appropriate all those responsible; provide redress to the victims.

- Conduct an assessment of recent aerial attacks that caused civilian casualties with the aim of adopting measures to ensure conformity with the laws of war or otherwise reduce civilian loss.

- Develop and implement effective measures to ensure that all individuals recruited for military duties are a minimum of 18 years of age; develop and impose appropriate disciplinary or criminal sanctions against individuals found to be recruiting or using children under that age.

- Actively encourage Yemeni and international aid agencies to carry out need assessments in areas known to have large numbers of displaced civilians living outside official displaced persons camps and take all possible measures to facilitate agencies’ access to them.

- Abide fully with international humanitarian law (the laws of war) during times of armed conflict. In particular, distinguish at all times between military objectives and civilians; never conduct deliberate, indiscriminate, or disproportionate attacks against civilians; and take all feasible precautions to avoid civilian casualties, even after warning civilians to leave an area.

- Ratify the Rome Statute establishing the International Criminal Court.

To the Huthis

- Stop all summary executions; investigate the alleged summary executions by Huthi forces of Ali Mirzaq in Tallan village on August 9, 2009; and Faris Muhammad ‘Ali ‘Ayyash in Majz village in early July 2009. Appropriately punish those responsible and provide redress for the victims’ families.

- Respect the right of the sick and wounded to obtain medical treatment, including by allowing them to travel to health clinics.

- Respect civilian property and do not confiscate or loot private property; provide fair payment for requisitioned commodities.

- Develop and implement effective measures to ensure that all individuals recruited for military purposes are at least 18 years old; develop and impose appropriate disciplinary sanctions against individuals found to be recruiting or using children under age 18.

- Encourage Yemeni and international aid agencies to carry out assessments in areas known to have large numbers of displaced civilians living outside official displaced persons camps and take all possible measures to facilitate agencies’ access to them.

- Abide fully with the laws of war during times of armed conflict. In particular, take all feasible measures to avoid placing civilians at risk by not deploying in densely populated areas.

To Saudi Arabia

- Do not forcibly return (refouler) Yemenis fleeing the conflict; allow all civilians fleeing the conflict and seeking refuge in Saudi Arabia to enter the country.

- If engaged in military operations in Yemen, abide fully with the laws of war. In particular, take all feasible precautions to avoid civilian casualties, including providing civilians with effective advance warning of attacks when circumstances permit.

To the United Nations

- Press the government of Yemen to cooperate in the establishment of a human rights monitoring mission in Yemen, under the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, with a mandate to publicly report on human rights abuses by all parties.

- Increase efforts to address the needs of all internally displaced persons living with little or no assistance in host families, public buildings and open spaces and take all possible measures to encourage the Yemeni authorities to allow full and unhindered access these displaced civilians; do not disproportionately focus aid efforts on those IDPs living in official IDP camps.

- Provide donors with regular detailed reports on agencies’ access and assistance to displaced civilians not living in camps and on obstacles to accessing and assisting them.

- Develop a cohesive strategy for development assistance in collaboration with the appropriate UN agencies to ensure that assistance addresses human rights concerns that drive instability in Yemen.

To Yemen’s Donors and Concerned Governments

- Urge all parties to the conflict to abide by their obligations under international humanitarian law.

- Call for full and impartial investigations into incidents involving alleged violations of the laws of war.

- Support the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights to open an office in Yemen to help independently monitor parties’ conduct in the war.

- Encourage Yemeni authorities to facilitate agencies’ access to areas known to have large numbers of displaced civilians living outside camps and monitor agencies’ ability to assess their needs and provide adequate assistance.

Methodology

Human Rights Watch researchers visited Yemen for 12 days in October 2009, including the capital, San’a, ‘Amran, Mazraq refugee camp in Hajja governorate and its surroundings--Jidr on the northern outskirts of San’a, and Qa’ al-Qaidhi, south of San’a. The researchers interviewed 20 displaced persons from Sa’da governorate’s Malahit, Razih, Haidan, Saqain, Wasit, and Talh districts for eyewitness accounts of the fighting and their own flight. We also spoke with representatives of UN agencies, Yemeni and international human rights and humanitarian organizations, and local journalists.

Human Rights Watch was unable to reach locations near the conflict area due to heightened insecurity. The Yemeni Ministry of Interior answered our October 21 request for permission to travel to IDP camps by directing us to the minister of health, who heads the committee on displaced persons. On October 24 Minister of Human Rights Dr. Huda Alban instructed her office to approve in writing our travel to all places we desired. Security personnel at the Mazraq refugee camp on October 24 did not permit us to speak to camp residents without a security official present.

This report draws attention to several reported incidents that give rise to concerns about the adherence to the laws of war by Yemeni government and Huthi forces. The lack of access to the conflict area hindered our efforts to corroborate information we received. Moreover, several displaced persons in San’a said they canceled scheduled meetings with us for fear of government reprisals against them. Displaced persons outside San’a had generally fled Huthi forces controlling their villages to reach government-held territory and appeared reluctant to directly criticize government actions. Because of such limited access to the conflict area and to persons directly affected by the fighting, the report calls for investigations into the incidents set out in the report and into the broader conduct of both sides.

I. The Sa’da War

Since mid-2004, an armed conflict has raged in Yemen’s northernmost governorate of Sa’da, near the border with Saudi Arabia. A group known as the Huthis, after the leader of the initial rebellion, Husain al-Huthi, has fought Yemeni government forces and pro-government tribal fighters. There have been six main rounds of fighting interspersed by periods of low-level fighting.[1] Fighting has spread to areas outside Sa’da governorate, including in 2008 to Bani Hushaish district on the outskirts of the Yemeni capital, San’a.

The most recent sixth round of fighting began around August 12, 2009, when the military launched what it called “Operation Scorched Earth.” Clashes started in early August around Hasama, near Malahit and Razih on the Saudi border, and in Saqain, south of Sa’da town. The hostilities have since spread to all districts in Sa’da governorate and south to ‘Amran and Jawf governorates. On February 11, 2010, the Yemeni authorities announced a ceasefire.

Yemeni armed forces have attacked Huthi rebels using fighter jets, artillery, and tanks. Huthi fighters mainly use small arms and some artillery.[2] No official casualty counts exist, but Yemen’s news outlets give almost daily reports of dozens of civilian and Huthi fighter casualties.[3] The Huthis regularly claim to have killed and captured Yemeni soldiers.

In early November 2009, Saudi Arabia joined the conflict against the Huthis. Huthi forces, claiming they were attacking a Yemeni army position located within Saudi territory, reportedly conducted a cross-border raid. Saudi air forces responded by bombing Huthi positions inside Yemen.[4]

During the recent fighting, Yemeni media outlets reported on numerous alleged atrocities, and the Yemeni government and Huthi rebels traded accusations of endangering or harming civilians during the conflict.[5] Yemen is party to the 1949 Geneva Conventions and their Second Additional Protocol, which applies during internal armed conflicts. Prior to the recent fighting, on June 22, 2009, Huthi rebel leader Abd al-Malik al-Huthi sent a letter by fax to Human Rights Watch affirming his group’s commitment to the principles of international humanitarian law.[6] In the past the Huthis have denied allegations that they violated the laws of war.[7]

The Huthi rebels agreed to the government’s terms for a ceasefire that came into effect February 12. According to the Yemeni government, the Huthis agreed to:

the opening of blockaded roads, demining of roadsides, withdrawal from civilian districts and avoiding interfering in the affairs of elected local authorities, returning looted civilian and military equipment, releasing Yemeni and Saudi detained civilians and military personnel, abiding by the Yemeni constitution, law and order, and refraining from any attacks on Saudi Arabian territory.[8]

The government said that four committees in four different locations had been created to oversee the implementation of the ceasefire.[9]

The Huthis

The Huthis originated in the 1990s as a religiously based movement called “Believing Youth” (al-shabab al-mu’min). Husain Badr al-Din al-Huthi founded the movement, which numbered between 1,000 and 3,000 in the mid-1990s, mainly to promote religious education in Sa’da governorate.[10]

Sa’da governorate is populated predominantly by adherents of the Zaidi strand of Shia Islam whose leaders (imams) ruled Yemen for a millennium until a military-led revolution deposed them in 1962 (disaffected Zaidi tribesmen also participated in the revolution).[11] The majority of Yemenis are Sunni, following the Shafi'i school of thought and living mostly in the southern and central parts of the country and along the Red Sea coast. The Shafi'i school is doctrinally close to Zaidi Shiism.

Although Zaidis are largely reconciled to the existence of a republican state in Yemen, strict Zaidi doctrine holds that the imam, the religious and secular leader of the Muslim community, has to be a Hashemite, a term used for the descendants of the Prophet Muhammad.[12] During the time of the Zaidi imamate, Hashemites formed the religious and governing elite.

Political and religious developments underlie the tensions that eventually led to the current conflict. For one, Yemenis (often Zaidis) returning to Sa’da from working in Saudi Arabia brought with them Sunni Wahhabi religious leanings (Wahhabism is a puritanical interpretation of Islam regarding daily conduct of Muslims that prevails in Saudi Arabia, and is typically hostile to Shia doctrines). Muqbil al-Wadi'i, originally a Zaidi, opened the Dammaj school in Sa'da, in the Zaidi heartland, in the early 1980s to propogate Wahhabi thought. Furthermore, the (Sunni) Muslim Brotherhood movement in Yemen established Scientific Institutes under the Ministry of Education that reached many Yemenis, before the authorities closed them in the late 1990s. After the unification of north and south Yemen in 1990 and the advent of multiparty elections, the Islah Party, which represents the political interests of the Muslim Brotherhood but also includes some tribal and Zaidi interests, emerged as the largest opposition party.[13]

To counter encroaching Sunni ideological currents and a steady weakening of Zaidi religious and Hashemite social influence, in the 1990s Zaidis began to set up their own religious schools and to revive the tradition of Zaidi religious study at mosques and study centers in the Zaidi heartland of northern Yemen. Unlike the Scientific Institutes, these schools were not part of the government education system. Wary of the growing Sunni and Wahhabi influence in Yemen's Zaidi areas, the government in the 1990s reportedly began to financially support Husain al-Huthi and his Believing Youth movement, dedicated to Zaidi religious revivalism. Badr al-Din al-Huthi, the father of Husain, is considered one of the three most influential Zaidi scholars in Yemen.[14]

The US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003, followed by the war between Israel and Hezbollah in Lebanon in July-August 2006 and growing tension between Iran and the US, boosted perceptions of Shiism as a powerful political force. Starting in 2003, the Huthis began to raise slogans of “Death to Israel. Death to America. Curse the Jews. Victory to Islam” in demonstrations following Friday prayers at the Great Mosque in San'a's old town center, and the government arrested up to 640 demonstrators in June 2004, with the army pursuing the capture of Husain al-Huthi.[15]

By no means do all Zaidis support the Huthis, and many do not follow traditional Zaidi doctrine. Yemen’s president, Ali Abdullah Saleh, is himself of Zaidi origin, and Zaidis from the powerful Hashid tribal coalition have been well represented in senior political and military positions in Yemen. During the fifth round of fighting, in 2008, security forces arbitrarily arrested many Hashimites, Zaidi religious activists, and those whose names indicated that they were from the conflict area.[16] This pattern of arbitrary arrests appears to have decreased but not disappeared in 2009.[17] In the view of some observers, the conflict is at least as much an expression of center-periphery tensions as it is of doctrinal or sectarian differences.[18]

The Huthis have not issued clear demands of the Yemeni government, although Huthi leaders have described their struggle as one of defending their right to freely exercise their religion and responding to humiliations by the authorities against their dignity and identity. They have described their resorting to use of arms as an act of self-defense.[19] Human Rights Watch has not found any indications that the Huthis, who as of early November 2009 controlled most of Sa’da governorate as well as northern parts of ‘Amran governorate and areas in Jawf governorate, have set up parallel governmental structures to administer the population’s civil affairs.[20]

Tribal Militia

The Sa'da, 'Amran, and Hajja governorates are home to powerful tribes, especially the Hashid and Bakil, who also adhere to the Zaidi sect. Tribesmen traditionally carry arms, and central governments have never had a significant military or law enforcement presence in these tribal areas. Tribal conflict is a regular occurrence in Yemen’s northern governorates, and has complicated the conflict between the government and the Huthis.[21] Since major fighting erupted in 2004, the government has recruited thousands of northern tribesmen to support its regular forces.[22] There are concerns that this heightened governmental military support to tribes in Sa’da governorate could lead to increasingly violent tribal confrontations—unrelated to the main government-Huthi conflict—and to new long-term inter-tribal conflict.[23]

Villagers from different parts of Sa’da and ‘Amran, such as Malahit, Saqain, Wasit, and Harf Sufyan districts, told Human Rights Watch that villagers joined the militias to defend their fields and homes against Huthi forces, with some indicating that the government provided weapons, money, and promises of future assistance. Human Rights Watch did not hear accounts of tribal militia fighting outside their home areas.[24]

Saudi Arabia

Both Saudi and Huthi sources have reported that rebels have taken over parts of Saudi territory and that Saudi Arabia has responded with aerial bombardment of Huthi positions inside Yemen. The Huthis say these attacks have killed civilians.

On November 5, 2009, the Saudi Press Agency reported that Saudi warplanes had bombed Huthi fighters who had taken over an area called Jabal Dukhan in Saudi Arabia two days earlier.[25] On November 7, the Saudi deputy defense minister, Prince Khaled bin Sultan bin Abd al-Aziz, said that Saudi forces had recaptured all Saudi territory seized by the Huthis. The following day the Huthis claimed that Saudi fighter planes had bombed their positions for six days in a row.[26]On November 10 Prince Khaled said that Saudi Arabia would only end its airstrikes once the Huthis had retreated “tens of kilometers” from the Saudi border.[27] Two days later, a Saudi official confirmed that Saudi Arabia was using air power and artillery to enforce a 10-kilometer buffer zone inside Yemen to keep Yemeni rebels away from its southwestern border. The official said that the zone would be no place for civilians.[28]On November 29, Prince Khaled declared that his forces had “cleaned up every inch of Saudi territory,” but in late January, Saudi Arabia rejected a truce offer by Huthi rebels to withdraw from Saudi territory.[29]

On November 10, the Huthis said on their website that earlier that day Saudi aerial bombardment had killed two women and wounded a child.[30] On December 13, 2009, Abd al-Malik al-Huthi, leader of the Huthi rebels, issued a statement accusing the Saudi military of launching multiple airstrikes that hit a public market in Bani Mu’in in Razih district in Sa’da governorate the morning of the same day, killing 70 persons the Huthis said were civilians and injuring hundreds.[31] The same day, Yemeni Defense Ministry spokesperson 'Askar Zu’ail claimed Yemeni aircraft had carried out strikes on Huthis in the area earlier that day.[32] Throughout December and January 2010, there were regular reports of continued clashes between Saudi forces and the rebels.[33] On January 26, the Huthis announced that they had withdrawn all their fighters from Saudi Arabia.[34]

International agencies have reported on the humanitarian consequences of the outbreak of fighting between Saudi Arabia and the Huthis. On November 12 the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) reported a sharp increase (280 people arriving daily, up from 140 in the previous week) in the number of civilians fleeing parts of Yemen’s Baqim district on the Saudi border to seek refuge in Mandaba village in Yemen.[35] On November 13 the UN children’s agency, UNICEF, reported that the government had evacuated 240 villages in southern Saudi Arabia on the border with Yemen.[36]

According to the Gulf States Newsletter, Riyadh has been contributing $US1.2 million a month as well as field intelligence to the Yemeni government’s Operation Scorched Earth.[37] On November 11, a Saudi official said his country had imposed a naval blockade along the northern part of Yemen’s Red Sea coast to stop weapons from reaching Huthi forces.[38]

II. Applicable International Humanitarian Law

Under international law, the conflict between the Yemeni government and the Huthis is a non-international (internal) armed conflict in which all parties are bound by international humanitarian law (the laws of war). Yemeni armed forces, pro-government tribal fighters, and Huthi forces are obligated to abide by article 3 common to the four Geneva Conventions of 1949,[39] the Second Additional Protocol of 1977 to the Geneva Conventions (Protocol II),[40] and relevant customary international law.[41] Since their introduction into the conflict in November 2009, Saudi forces are also bound by the laws of war.[42]

International humanitarian law requires the humane treatment of civilians and other persons no longer taking part in the hostilities, including wounded or captured combatants. It prohibits summary executions, torture and other ill-treatment, rape, and the recruitment of children as soldiers.

Humanitarian law also provides rules on the conduct of hostilities to minimize unnecessary civilian casualties and destruction of property. This includes the prohibition on attacks directed at civilians that do not discriminate between civilians and military targets, and that cause civilian harm disproportionate to the expected military gain, or deployment of forces that place civilians at unnecessary risk. There are also requirements relating to humanitarian access to provide relief to the civilian population.

Human Rights Watch’s research, reports by Yemeni human rights groups, and media accounts suggest that the most frequent violation of the laws of war by government forces has been indiscriminate aerial bombing and shelling that has resulted in civilian casualties.

A second persistent concern is the government’s use of children in their forces.

Reported laws-of-war violations by Huthi forces, discussed in Chapter IV, include the deployment of forces in densely populated civilian areas, summary executions, looting of private property, and the recruitment of children, at times using coercion.[43]

There have also been reports that tribal militias supporting the government also use child soldiers.[44]

Because of the difficulties of gaining access to the conflict area by Human Rights Watch and other rights groups, humanitarian agencies and journalists, any discussion of alleged laws of war violations by all sides is likely to be incomplete.

Two fundamental principles of the laws of war are civilian immunity and distinction. Parties to an armed conflict have a duty at all times to distinguish between combatants and military objectives on the one hand and civilians and civilian objects on the other. Parties to a conflict may only target the former.[45]

Civilian objects are those that are not considered military objectives.[46] Military objectives are combatants and those objects that “by their nature, location, purpose or use, make an effective contribution to military action and whose total or partial destruction, capture or neutralization, in the circumstances ruling at the time, offers a definite military advantage.”[47] In general, the law prohibits direct attacks against what are by their nature civilian objects, such as homes and apartments, places of worship, hospitals, schools, or cultural monuments, unless they are being used for military purposes.[48]

Deliberate, indiscriminate, or disproportionate attacks against civilians and civilian objects are prohibited. Attacks are indiscriminate when they are not directed at a specific military objective, or employ a method or means of warfare that cannot be directed at a military objective or whose effects cannot be limited.[49]One form of prohibited indiscriminate attack is area bombardment. Any attack, whether by aerial bombardment or other means, that treats as a single military objective a number of clearly separated and distinct military objectives located in a town, village, or other area containing a concentration of civilians and civilian objects, is regarded as an indiscriminate attack and prohibited.

A disproportionate attack is one in which the expected incidental loss of civilian life and damage to civilian objects would be excessive in relation to the concrete and direct military advantage anticipated.[50] The expected danger to the civilian population and civilian objects depends on various factors, including their location (possibly within or near a military objective), the accuracy of the weapons used (depending on the trajectory, the range, environmental factors, the ammunition used, etc.), and the technical skill of the combatants (which can entail random launching of weapons when combatants lack the ability to aim effectively at the intended target).[51]

In the conduct of military operations, parties to a conflict must take constant care to spare the civilian population and civilian objects from the effects of hostilities.[52] Parties are required to take precautionary measures with a view to avoiding, and in any event minimizing, incidental loss of civilian life, injury to civilians, and damage to civilian objects.[53]

Before conducting an attack, a party to the conflict must do everything feasible to verify that the persons or objects to be attacked are military objectives and not civilians or civilian objects.[54] In its Commentary to Protocol I, the International Committee of the Red Cross explains that the requirement to take all “feasible” precautions means, among other things, that those conducting an attack are required to take the steps needed to identify the target as a legitimate military objective “in good time to spare the population as far as possible.”[55]

With respect to individual responsibility, serious violations of international humanitarian law, when committed with criminal intent, are war crimes. Criminal intent has been defined as violations committed intentionally or recklessly.[56] Individuals may also be held criminally liable for attempting to commit a war crime, as well as assisting in, facilitating, aiding, or abetting a war crime. Responsibility may also fall on persons planning or instigating the commission of a war crime.[57]

III. Government Conduct and International Humanitarian Law

Indiscriminate Attacks

Based on eyewitness accounts of attacks, Human Rights Watch is concerned that Yemeni forces may have conducted indiscriminate airstrikes and artillery attacks that have resulted in the death and wounding of civilians as well as in the destruction of civilian property.

Yemeni government forces have conducted airstrikes mostly with Soviet-designed MiG fighter jets.[58] In October 2009, Human Rights Watch researchers saw and heard these jets, visibly based at San’a’s international airport, as often as five times a day as the jets left San’a, flying north. Staff from Yemeni and international nongovernmental organizations told Human Rights Watch that in previous weeks, especially during the Muslim holy month of Ramadan (August 18 - September 18) even more jets flew missions from the capital every day.[59]

According to Jane’s Information Group, Yemen has a stockpile of unguided air-to-ground bombs that MiG jets can deliver.[60] However, the MiG-29 aircraft operated by Yemen are also capable of delivering a television guided bomb called the KAB-500KR, but it is not known if Yemen has acquired these weapons. According to a knowledgeable observer, Yemeni MiGs flying missions against the Huthis did not use guided munitions, but 500-pound “dumb” bombs.[61] Pilots time the release of such bombs based on a number of variables, including aircraft speed and height, and once released, the bomb’s trajectory cannot be changed.[62] MiGs dropping such bombs against military targets close to civilians would raise concerns of indiscriminate or disproportionate use.

Human Rights Watch collected information from eyewitnesses to airstrikes that raised concerns that these attacks were carried out against Huthi positions in an indiscriminate manner, causing unnecessary civilian casualties. The fact that civilian casualties occurred, however, does not automatically mean that a violation of the laws of war has been committed. Because of the limited information, further investigations are needed to determine whether all feasible precautions to spare civilian loss were taken and whether the methods and means of attack were appropriate in the circumstances prevailing at the time.

Cases

Human Rights Watch has collected information on 10 Yemeni airstrikes in which civilians were killed or injured that raise concerns about possible indiscriminate or disproportionate attacks in violation of the laws of war. In a further three cases, the Yemeni and international media reported on similar possible violations.

‘Adi, near Harf Sufyan town, ‘Amran governorate

On September 16, several airstrikes on ‘Adi resulted in the deaths of 85 civilians, according to News Yemen, an independent news website.[63]The Associated Press quoted an ambulance driver who said he drove at least 120 persons to hospital following the airstrikes.[64]

That day, a local resident described the airstrikes to the Dialogue (Hewar) Foundation, an independent Yemeni human rights organization, and answered questions Human Rights Watch had provided to Hewar. He said he had seen four aerial attacks that struck a group of displaced persons sheltering near a school. He said that there were no armed clashes or Huthis in the area at the time, although the area was close to a road sometimes used by the Huthis.[65]

On September 18, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Navanethem Pillay called on the Yemeni government to launch an investigation into the incident.[66] The same day, Yemeni authorities responded that they had investigated the bombings, but no findings have been released at this writing.[67] Knowledgeable sources said the government had formed a committee of local shaikhs to investigate the matter. The committee reportedly concluded the government had bombed the location by mistake. To date, the government has not made public the committee’s report and has taken no further action.[68]

Razih district, Sa’da governorate

On October 15, Yemeni airstrikes hit a market and a medical facility in Razih district ofSa’da governorate.

A well-informed source told Human Rights Watch that in the preceding weeks there had been regular clashes in the mountains surrounding Razih between Huthi and government forces. The fighting reached Razih town on October 13.[69] Fighting continued on October 14, during which Huthi forces reportedly killed the chief of staff of the 36th Battalion, 28th Infantry Brigade in an ambush.[70] The independent Yemeni newspaper Al-Masdar reported that on the morning of October 15, Yemeni aircraft bombed the Razih market.[71]

The well-informed source said that villagers brought 16 casualties—one dead baby, four dead adults, and 11 injured—to the local Ministry of Health clinic. Health workers at the clinic believed the adult casualties were all civilians because there was no evidence that they were soldiers and the Huthis do not normally bring injured fighters to government clinics.[72] A nurse from Sa’da town’s Republican Hospital also said that Huthi fighters did not use that government facility.[73] It is possible that Huthi fighters were killed or injured in the airstrikes and taken elsewhere.

Later that day, a bomb or artillery shell struck the Ministry of Health clinic, which as a medical facility is a protected object under the laws of war.[74] None of the patients or staff was injured.[75] The clinic’s roof reportedly marked the building as a medical facility.[76] The well-informed source said the clinic is a freestanding building located on the edge of town, and no combatants were in the vicinity of the building at the time it was hit.[77]

Harf Sufyan town, ‘Amran governorate

In August, Yemeni aircraft bombed locations close to Harf Sufyan town on two separate occasions that struck civilian objects, according to a local source.

According to a witness, on a Monday shortly before Ramadan, which would have been August 10 or August 17, a “bomb” and a “missile that cannot change direction” [apparently a rocket, which is unguided] hit his house while he and his family of 12 were there. He said,

MiG jets were bombing in a line straight through Harf Sufyan town toward the mountains in the north. They fired two rockets on my house. One hit the house and the other one landed in front of my house.[78]

He said that the Huthis had occupied Harf Sufyan town, with a population of about 45,000,[79] since shortly before Ramadan, but were not in the vicinity of his home:

There were no clashes in the area at the time [of the bombing] and the Huthis were some distance from my home inside the town, nowhere near my house...The military was stationed in the mountains to the south and the Huthis were along the main street and in Harf Sufyan’s old town and in the northern mountains far away. The Huthis were moving back and forth in the Wadi north of town in the weeks before Ramadan.[80]

In the second incident, on August 18, the first day of Ramadan, the witness was at his mother’s house in Mudaqqa village after evacuating his family following the bombing. He told Human Rights Watch,

Shelling began and Mudaqqa was hit. A shell fell on my mother’s house, destroying the southeastern-facing living room on the second floor. [It came] from the hilltop to the south, about three kilometers away... You cannot see who or what is firing at you, but we know those are the government positions.

After his mother’s house was hit, the witness said that he telephoned the military commander, who apologized to him for hitting his mother’s house in an apparent mistake. He said,

I called the brigade commander and he said that the house was hit ‘by accident ’. We have Faisal Rajab’s [telephone] number because he’s been there for a while. Everybody likes the commander. He cares for the people. He is from the south.[81]

The same man also described a third incident in which a young cousin who was defending Mudaqqa village from the Huthis was injured by shrapnel from government artillery fired from nearby mountains. The incident gives some indication of government failure to take all feasible precautions in carrying out attacks. He said,

During Ramadan, the Huthis tried to take Mudaqqa. They did not have artillery until after Eid [September 19] and unsuccessfully attacked the village with machine guns, bazookas [portable rocket launchers] and RPGs [rocket-propelled grenades]. The government was firing from one side across the top of the village to hit the Huthis on the other side.

Our town has watchtowers from which villagers defended the village. A young man ...was on one of the northern towers and was hit in the head by shrapnel that came from the government shelling of the Huthis. We took him to the medical military camp and the military apologized and treated him.[82]

Silah village, in Sa’da governorate’s Wasit district

Yemeni aircraft reportedly bombed five nearby villages in Wasit district, an area comprising a big riverbed surrounded by some 40 villages. A man from Silah village told Human Rights Watch that the Huthis took over the area in the three months preceding the start of Ramadan (August 18). During that time, government planes bombed Silah and at least three other nearby villages—Shaqih, al-Haira and Wadi ‘Ayyan. He says there were no Huthi forces present in any of the villages at the time they were struck.

He did not know the date his village was bombed, but recalled,

At about 10 o’clock in the morning, three bombs hit two houses, injuring seven children who were playing outside in the street. Three of them were from the Qadar family, aged between six and eight, and four, aged between five and eight, were from the ‘Amrani family. I was in a neighbor’s house close to where the bombs fell. There were no Huthis in the village at the time. They were in the mountains, about two kilometers away.[83]

‘Allan village, Haidan district in Sa’da governorate

Yemeni aircraft conducted multiple airstrikes on ‘Allan village, which had been occupied by Huthi forces.

A villager told Human Rights Watch that the Huthis had taken over ‘Allan after the fifth round of fighting, which ended in July 2008. Ten days before Ramadan, about August 8, 2009, they began shooting at government planes that were attacking the area. The villager described how his daughter was injured in an aerial attack:

Every day, two or three times a day, government planes raided our village and the areas close by. Even though the Huthis were firing artillery at the government from inside the town, the government didn’t seem to target the town itself, maybe because they knew there were still civilians there. Most of the time the planes hit their Huthi targets outside the village, but there were some mistakes when they hit houses in the village.... [M]y house was also destroyed by a plane and my daughter was injured in the attack. There were no Huthis close to our house when it was hit. Their closest position was in a tall building, but that was quite far from our house.[84]

Another man from ‘Allan village told Human Rights Watch about another house that was hit:

The government planes bombed, but did not hit any civilian houses until 20 days ago [on October 3], when Ahmad Muhammad Ali al-Qadi’s house was destroyed.[85]

Several residents said that Huthi fighters were located in a tall building in the village from where they shot at planes with a ZU-23, a Soviet-designed anti-aircraft gun.[86]

Talh town, Sa’da governorate

On September 14, government planes reportedly bombed the market in Talh town, killing 34 persons, mostly women and children, according to the website of the opposition Socialist party.[87] The Yemeni Center for Human Rights reported that “dozens” of civilians were casualties in the bombing.[88]

Human Rights Watch spoke with a person in close touch with witnesses to the attack, who said that five dead and 31 wounded civilians, mostly women and children, were taken to the clinic in Talh shortly after the market was hit.[89]

On September 15, a defense ministry official denied government involvement in the Talh market bombing.[90] That day the Huthi’s media office circulated 19 photos and 4 videos on the internet that it said showed the aftermath of the market bombing. The photos show dead and injured, including children. Two of the videos show a large crater, about 10 meters in diameter and 2 meters deep, destroyed houses, and overturned cars.[91] Human Rights Watch could not confirm the source and date of the photos and videos.

Marawin and Tallan villages, in Sa’da governorate’s Malahit and Haidan districts

Government airstrikes on Huthi forces active in two villages in Malahit and Haidan districts, days before Ramadan, resulted in civilian injuries and damage to civilian property.

A man from Marawin village described what happened to his house, though he was not present at the time. He said that the Huthis were deployed elsewhere, in a house some distance away:

The Huthis had Kalashnikovs [AK-47 assault rifles], and shoulder-fired rockets, but no artillery, and shot at the planes. A rocket came through the roof of my house and one landed in front of the house.[92]

A man from Tallan village said he fled after a government airstrike and after a number of other villagers had been killed by government artillery shelling and Huthi small-arms fire:

There were airstrikes in the morning, afternoon, and evening. The [planes] fired rockets into [Huthi] dugouts on the outskirts of town and the government also fired artillery into the village from far away. The Huthis fired at the planes, mostly with Kalashnikovs. Ten civilians died from the artillery fire and from Huthi small-arms fire.[93]

In addition to these 10 cases about which Human Rights Watch spoke with witnesses, the Yemeni media and Yemeni human rights groups have reported on alleged violations of the laws of war by both the Yemeni military and by the Huthi rebels.

Yemeni media has carried reports based on local sources alleging that the Yemeni military has indiscriminately bombed civilian areas, leading to dozens of civilian deaths and injuries. Human Rights Watch was unable to verify the two accounts presented below.

Haidan market bombing, in Sa’da governorate’s Haidan district

On August 12, Aleshtiraki.net, the media organ of the opposition Socialist Party, reported that 20 civilians were killed when government aircraft bombed the market in Haidan town, in the Haidan district of Sa’da governorate. The website based its account on a report from a cultural organization in Sa’da and released what it said were eyewitness accounts and photos of the aftermath of the attack.[94] The article said that civilians died in their houses, and showed pictures of injured or dead children. It did not refer to any Huthi presence in the market at the time and said the attack took place at a time when the market was crowded.[95] To date, the Yemeni government has not acknowledged this attack.

Saqain market bombing, in Sa’da governorate’s Saqain district

On October 23, the Huthis accused the Yemeni government of bombing a crowded market in the Sha’af area of Saqain town. The Huthis say three people were killed and an unspecified number of people were injured.[96]To date, the Yemeni government has not acknowledged this attack.

Advance warning of attacks

Parties to an armed conflict are obligated to take all feasible precautions to minimize harm to civilians and civilian objects.[97] When circumstances permit, they must give “effective advance warning of attacks which may affect the civilian population.”[98] The failure of civilians to heed such warnings does not make them subject to attack—the attacker must distinguish at all times between civilians and military objectives and to direct attacks only at the latter.

In two of the incidents above, witnesses told Human Rights Watch that Yemeni forces issued advance warnings. A villager from Manzala said that, before starting to bomb the village in mid-August, “the military ordered everyone to leave using megaphones and dropping leaflets from planes” with the message to “leave now.”[99] A government soldier also told Human Rights Watch that “usually, but not always,” the government gave warning to villagers they should leave.[100] The Yemeni media has carried reports of the government dropping leaflets urging the population to leave.[101]

Human Rights Watch could not confirm the extent to which advance warnings were given, whether they were “effective,” or when warnings were not given although the circumstances permitted it. In all the other incidents reported to Human Rights Watch, the witnesses said that there were no advance warnings of attacks from the Yemeni military.

Child Soldiers

All parties to the conflict in Yemen are bound by the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the involvement of children in armed conflict, which establishes 18 as the minimum age for any conscription, forced recruitment, or direct participation in hostilities.[102]

Determining the age of youth in Yemen can be difficult: the country has very poor birth registration and international officials told Human Rights Watch that due to widespread stunted growth from malnutrition, children may look younger than they are.[103]

Nonetheless, the government has not taken effective steps to ensure its military does not deploy child soldiers. On October 10, 2009, the Times of London published an interview with a former child soldier fighting in a tribal militia earlier that year.[104] According to the Times, the child soldier believed he was 14 years old. He said that he ‘“had a Kalashnikov [and] spent the past few months as a fighter for the Government in the civil war against the al-Houthi rebels... He was involved in firefights.”[105]

Human Rights Watch interviewed two child soldiers fighting in the regular Yemeni army. Both had recently fought in the Malahit area. They said they were on leave from their military duties to be with their families, who had recently been displaced by Huthi forces that had taken over their villages.

The first boy, from Khulan in Sa’da governorate, initially claimed he was “about 18 or 19 years old,” but subsequently said he was born in 1994,[106] which his father confirmed in a separate interview, saying he was 14.[107] The boy said that he had spent his first six months in training in San’a, and had been “a soldier for one-and- a-half years” in the 22nd Infantry Brigade. He said that from mid-August until mid-October 2009 he had been stationed with his older brother in the ‘Abs/Malahit area near the Saudi border, fighting the Huthis.[108]

In the presence of his extended family, the second youth, from Tallan, admitted his age—16—with some pride, saying he was fighting in the army with the government and that he was in the 105th Infantry Brigade.[109]

He told Human Rights Watch,

I was stationed in the [military base] near Malahit called “Camp.” I trained there for two months, which included saluting, marching, singing the national anthem, how to identify a Huthi, and firing, though only with a wooden rifle. When I finished [training], I got my own rifle from the government... a rifle with 30 shots. I finished training [in mid-June 2009] and have been in the Camp since then, until I came here on leave [at the end of Ramadan].”[110]

An adult soldier from the same town confirmed the youth as being a soldier, but did not know whether he had participated in combat.[111]

IV. Huthi Conduct and International Humanitarian Law

Non-state armed groups such as Huthi rebel forces are bound by international humanitarian law whether or not they explicitly commit to respect them. In the armed conflict in Yemen, this law includes Common Article 3 to the 1949 Geneva Conventions, Protocol II, and customary laws of war. [112]

On June 22, 2009, the leader of the Huthi rebel forces, Abd al-Malik al-Huthi, sent a letter by fax to Human Rights Watch affirming his group’s commitment to the principles of international humanitarian law:

[W]e are very careful with the treatment of civilians, and we treat them humanely in a manner that protects their rights mentioned in international humanitarian law and international human rights law... We also confirm being keen to keep civilians neutral and spare them conflict. We also work laboriously towards supporting their protection and saving their lives, possessions and dignity.[113]

However, the Huthis appear to have committed serious violations of the laws of war during the sixth round of fighting. Human Rights Watch received reports from civilians who had fled the conflict zone of Huthis committing summary executions of persons in their control, using non-combatants as “human shields” to deter government attacks, and recruiting children to be combatants. There were also reports that Huthis placed civilians at unnecessary risk by deploying in densely populated areas, prevented civilians from fleeing combat zones to receive medical evacuation, and looted private property.

According to a Yemeni government health official interviewed by Saba.net, on October 8, 2009, Huthi fighters opened fire on a UN relief convoy delivering assistance to displaced families in al Madbah camp, Jawf governorate.[114]

Because of limitations on access, Human Rights Watch was unable to independently corroborate these allegations of serious laws-of-war violations.

Summary Executions

International humanitarian law prohibits the killing of “[a]ll persons who do not take a direct part or who have ceased to take part in hostilities,“that is, civilians and captured or incapacitated combatants.[115]

According to “local sources” interviewed by the Yemen Observer newspaper, a paper with close ties to President Saleh, published on October 14, Huthi fighters executed two civilians—Yahya Bin Yahya Misfir and Ali Dhaif Allah Masawi—by firing rocket propelled grenades at them, and kidnapped nine others when they refused to fight with the Huthis against government troops in Razih district, in Sa’da governorate.”[116]

Human Rights Watch independently learned of a case of an alleged extrajudicial killing during the previous round of fighting. Huthi forces allegedly summarily executed Faris Muhammad ‘Ali ‘Ayyash in Sa’da governorate’s Majz district in early July 2008. According to second-hand information from a relative, for some time the Huthis sought to take control of the farm located on the edge of Majz village, near Dhahyan town, belonging to `Ayyash’s uncle, al-Thulaya. The farm was apparently key to controlling the whole village.[117] The relative learned that on the day of the killing, `Ayyash was in a hut in the fields: “At about 10 o’clock in the morning, around 20 Huthis entered the farm and killed him in front of the hut–with just one bullet in the head.”[118]

Human Rights Watch received information on two instances of alleged summary executions by Huthi forces during the sixth round of fighting.

The Huthis allegedly summarily executed Ali Mizraq on August 9, 2009, in Tallan village, Haidan district. Human Rights Watch interviewed four individuals about the incident, including two relatives, one of whom was present at the scene immediately before and after the killing.

According to his relatives, Mizraq was a local councilor for the ruling General People’s Congress Party. Since the outbreak in early August of the sixth round of fighting, he was the leader of the village guards, a tribal militia organized to defend the village against Huthi attack.[119]

According to Mizraq’s relative:

I was in my house in the nearby village of al-Muhallal, not more than half a kilometer away from where it happened. I heard shooting and went outside. The shooting was coming from the Hasan al-Tallan area, which is higher up in the mountains above Tallan village.I wanted to go and see what happened but the Huthis were shooting at my house from high up in the hills so I could not go. After a while they stopped shooting, so I left the house later that morning, at about 9 a.m., and saw my brother’s body.

I did not see the moment when the Huthis killed him but the relatives who took away the body said they saw armed strangers next to the mechanic’s garage where we knew Huthis had been staying the week before since they had arrived from Duwaib, al-Fadhil, and Haidan. Other Huthis were staying with other Hashimite families in our village. That same day I saw about 50 armed Huthis leave many houses in the village and they went up to the mountains near the village to take up positions there.

They killed Ali because they are against anyone who works for the government. I fled the village because I thought they would kill me too.”[120]

According to a second relative:

Ali had given his car to a local mechanic. On Sunday morning [August 9, 2009], he got a call that the car was ready and he went to pick it up at the garage on the top of the hill. He was shot there. I saw his body. It had four bullet wounds to the chest, two on the left and two on the right. His hands, forearms, feet and lower legs were burned.[121]

These accounts suggest that Mizraq, though a militia leader, was not directly participating in hostilities at the time he was killed, and was thus not a legitimate military target.[122]

Later the same day the Huthis attacked the village and eventually occupied it.[123]

Human Rights Watch was not able to ascertain whether additional extrajudicial killings have taken place.

In another incident reported to Human Rights Watch, the Huthis allegedly threatened the lives of civilians. A member of a tribal militia that fought against the Huthis in Saqain town in June and July 2009 told Human Rights Watch that during the Huthis’ occupation of the town, they “sometimes planted a mine at the corner of a house to get people out so they could advance.” He could not recall whether Huthi forces ever exploded such a mine. [124]

Human Shielding

Under the laws of war, parties to a conflict are prohibited from engaging in “human shielding”—intentionally using civilians “to shield military objectives from attacks” or using their presence “to shield, favor or impede military operations.”[125]

Yemeni government officials have accused the Huthi rebel forces of using civilians as “human shields” but have provided no basis for their allegations.[126] For instance, following criticism of the government’s airstrike on ‘Adi in the Harf Sufyan district on September 16 that killed over 80 persons, including displaced civilians, the Ministry of Defense emailed a statement to the media claiming that Huthi “terrorists are using innocent citizens as human shields.”[127]

Human Rights Watch received information about one possible incident of shielding by the Huthis, although this incident could not be corroborated.

According to a resident of Harf Sufyan, between late August and mid-October 2009 government forces deployed on mountains to the south of Harf Sufyan town while Huthi forces were within and to the north of the town. The fighting was sustained, with thegovernment mainly firing artillery and conducting airstrikes, while the Huthis fired back with artillery. The Harf Sufyan resident told Human Rights Watch,

After many days of the army shelling Harf [Sufyan town] day and night, the Huthis brought about 30 captured officers, not normal foot soldiers, into Harf [Sufyan] town. They made them call the military and tell them they were in Harf so that the military would not attack the Huthis there.[128]

A video posted on YouTube on September 2 provides general support for this account. It shows six persons dressed in what appear to be Yemeni army fatigues. Two individuals with two stars and a crown (the rank of colonel) on their lapels describe the date as the 19th of the current month and their present location as Harf Sufyan, where they say Huthi forces had taken them after they surrendered on August 21, 2009.[129] A military source called the video a “media fabrication.”[130]

Using captured combatants to deter an enemy attack is using them as human shields, which is a war crime.

Deploying within densely populated areas

The laws of war do not prohibit fighting in urban areas, although the presence of civilians places obligations on warring parties to take steps to minimize harm to civilians.

Parties to a conflict are required to take all feasible precautions to protect the civilian population and civilian objects under their control against the effects of attack.[131] Precautions include the obligation “to the extent feasible, [to] avoid locating military objectives within or near densely populated areas” and to endeavor “to remove the civilian population ... from the vicinity of military objectives.”[132]

The independent Yemeni human rights organization HOOD reported that the Huthis have deployed in densely populated areas, unlawfully putting civilians at unnecessary risk, and have recruited children to fight with them.[133]

Human Rights Watch spoke with over a dozen persons about the circumstances in which Huthi forces located military objectives within densely populated villages.

Several people who fled Huthi advances recounted how Huthi forces set up headquarters inside populated villages and shot from within the village at Yemeni military planes flying overhead. While the laws of war do not prohibit the occupation of populated towns, oftentimes the Huthis took little or no action to remove civilians from an area under their control that was at risk of being attacked in the event of hostilities.[134] Villagers would ask the Huthis to stop firing at government forces and aircraft for fear of being bombed by government forces in counterattacks. Government bombing against Huthi positions in towns and villages, in many cases after the Huthis have shot at military aircraft, has often resulted in civilian casualties (see Chapter III).

One of those villages was ‘Allan, in Haidan district, which the Huthis had occupied since the fifth round of fighting in early 2008. Human Rights Watch was unable to visit ‘Allan to determine whether Huthi forces could feasibly have redeployed their forces or safely removed civilians from the vicinity of their forces to reduce the risk to the civilian population in the event of fighting.

A man from ‘Allan told Human Rights Watch how his village became the site of exchanges of fire at the outbreak of the sixth round of fighting in August 2009, as the Huthis fired from within the village at government aircraft:

About 10 days before Ramadan [in early August], the Huthis started firing their 23/147 [Hoon or ZU-23] guns against government fighter jets above from the tallest building in the village and we were afraid that they would attract revenge bombing.[135]

Another man from ‘Allan said,

The Huthis occupied the Mawqi’ house in town, and used a 23/147 Hoon to fire at aircraft. Some villagers asked them not to fire on the planes from inside the village, but they only said “If God wills, no Yemeni will remain. This is the religion of God and we will not go back on it.”[136]

Child Soldiers

Under international law, Huthi forces have an obligation not to recruit or engage children as combatants. The Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict provides that “[a]rmed groups that are distinct from the armed forces of a state should not, under any circumstances, recruit or use in hostilities persons under the age of eighteen."[137]

The government accuses the Huthis of using child soldiers. For example, on November 4, 2009, the minister of health and population, Dr. Abd al-Karim Rasi’, briefed international organizations on alleged human rights abuses by the Huthis, including what he said was their use of child soldiers.[138]

On December 10, at an NGO-sponsored conference in San’a addressing the issue of child soldiers, a nine-year old boy and his father recounted how the Huthis asked him to smuggle explosives and detonators in Sa’da town.[139]

In November Radhika Coomaraswamy, the UN secretary-general’s special representative for children and armed conflict, began an investigation into the use of child soldiers in Yemen, including by Huthi rebels.[140] The same month, Sigrid Kaag, regional director for UNICEF, referred to “anecdotal evidence” that the Huthis were using child soldiers.[141] On February 12, Coomaraswamy reported that in Yemen “large-scale recruitment [is] going on, primarily among the rebels, but also among some of the forces backed by the government – not the government army but the militias backed by the government.”[142]

The 14-year-old child soldier in the government’s army interviewed by the Times in October 2009, mentioned above, also recalled one battle that ended with the deaths of three Huthis whom he believed were no older than himself. He told the Times, “On these Houthis we found a piece of paper saying they will go to paradise. They convince children to fight by giving them this paper that promises they’ll go to paradise.”[143]

A person from Saqain district who fought in a pro-government local tribal militia defending Saqain town against the Huthis in mid-2009 told Human Rights Watch about the Huthis’ use of child soldiers. He said,

The Huthis used children to fight. I saw two children with Kalashnikovs standing guard for the Huthis outside Saqain town. They were no older than 13 or 14. We did not shoot them, because it is forbidden [haram]: we cannot deprive them of their lives. We only shot them in the feet or their legs.[144]

Pillage and Looting

International humanitarian law prohibits the forcible taking of private property for private ends, or pillage.[145] Looting or confiscation of private property is also prohibited.[146] A force occupying territory may requisition commodities—such as food and fuel—needed for its maintenance, so long as the needs of the civilian population are taken into account. Payment should be immediate.[147]

Human Rights Watch obtained information relating to five cases in which Huthi forces allegedly looted private property.

A man from ‘Urdh village described a Huthi attack on Malahit market, around two weeks after he was forced out of his village in early August 2009:

The Huthis killed three soldiers there, point blank, and took all the qat [a popular stimulant leaf] and looted 200 bags of wheat from a UNICEF school. I saw this from a distance and someone else later told me what they had stolen.[148]

Others alleged that Huthis looted private homes of people who had fled the fighting or whom the Huthis had forced from their homes.

A man from ‘Allan village said that the Huthis forced him to leave all his belongings behind on September 25, 2009, as he was fleeing because they wanted it for themselves: “I had to leave everything behind, including my jambiya [symbolic dagger], before my family and I were allowed to leave.”[149]

A man from ‘Iqab village five kilometers south of Sa’da town told Human Rights Watch that the Huthis forced him and his family to leave their home in September 2009 and that when his brother had returned to check on the house by the end of the month: “He found it empty, completely looted, all the gold, furniture, rugs, and clothes gone. We had a car. The Huthis took that too.”[150]

Relatives of Faris ‘Ayyash, whom the Huthis allegedly summarily executed in July 2008 (see above), said that “50 days after that incident, the Huthis came back and looted the farm, including the water pump.”[151]

In Marawin village, the entire civilian population left after Huthi forces took over the town in mid-August. One villager told Human Rights Watch,

I secretly went back to my village to retrieve some documents for the children ... The house was as I had left it, but other houses were looted, especially that of Shaikh Jailani, which the Huthis had taken over and completely emptied. There were no villagers left, only Huthis.[152]

Human Rights Watch’s evidence does not indicate that looting was systematic. A man from Harf Sufyan told Human Rights Watch that in August 2009 “the Huthis occupied the houses [of strategic importance] on Harf Sufyan’s main road [but they] did not enter the private homes in our area.”[153]

Human Rights Watch heard accounts of three incidents in which Huthi forces unlawfully confiscated private property from local residents.

A man from al-Hariba village, northwest of Sa’da town, told Human Rights Watch that when the Huthis occupied the town around September 2009, they confiscated private property from villagers belonging to pro-government tribes:

The Huthis confiscated cars and minibuses from the Andalunis family and other families without compensation... They told people it was “for the sake of jihad.” The Andalunis are from the Hashid tribe, but most Huthis are from the Bakil tribe.[154]

It is also a serious violation of international humanitarian law for a party to the conflict to destroy or remove “objects indispensable to the survival of the civilian population,” such as food and agricultural areas for the production of foodstuffs.[155]

A man displaced from the area around Madhabb village, in Sa’da governorate, told Human Rights Watch,

The Huthis want to take half of the harvest so there is no point in going back home. They took half of the harvest in Madhabb and Habasha villages—they take from everyone and if you refuse they kill you.[156]

The man did not know of any case where those who refused to provide the demanded harvest were killed, though such a demand would be difficult for a villager to resist.

The Huthis typically do not exercise civilian administrative functions in the areas they control. However, one man told Human Rights Watch that in ‘Allan village they reportedly began to impose “taxes”: “Since they took over the town, the only real change has been that they make us pay zakat [the Islamic alms tax]. Before, we paid the state.”[157]

Prevention of Flight and Denial of Access to Medical Care

Under international humanitarian law, parties to a conflict must take all feasible precautions to protect civilians under their control from the effects of attacks, including by removing civilians from the vicinity of military objectives.[158]

Civilians also have the right to access medical care. Common article 3 of the Geneva Conventions provides that the “wounded and sick shall be collected and cared for.”[159] Article 7 of Protocol II protects “all the wounded, [and] sick, whether or not they have taken part in the armed conflict,” and mandates their humane treatment, including the right to “receive to the fullest extent practicable and with the least possible delay, the medical care and attention required by their condition.”[160]

There are very few medical facilities in northern Yemen. During the conflict, government healthcare staff have left town when Huthi forces took over. The possibility of traveling overland to healthcare facilities in larger towns such as Sa’da town is therefore imperative for those requiring medical treatment.[161]

Human Rights Watch spoke with four people who said that Huthi forces had prevented them and others from leaving their village, including to obtain medical treatment.

A man from ‘Allan village said, “The Huthis wanted to prevent me from leaving town the day after my house had been bombed and allowed only women to leave.” After some time, they allowed him to leave.[162]

A displaced man from al-Hariba village told Human Rights Watch about several incidents in which Huthi forces prevented people from fleeing in order to obtain medical care. In one case, during Ramadan [August 18 – September 18],

A woman from the Bakil tribe had a miscarriage, after the government bombed the area around our town. She could not travel to the Talh clinic, because the Huthis prevented her from leaving. Another man, Ahmad Yahya Andaluni, had a stroke, but could not get to the hospital, because the Huthis blocked the road.[163]

In the fifth round of fighting during 2008, Huthi rebels allowed a woman to bleed to death, eyewitnesses said. A man from ‘Allan village told Human Rights Watch that in October 2008 Huthi forces had let his 27-year-old aunt bleed to death at a checkpoint:

Dardah al-Qatur wanted to leave her village and find safety at the army’s base nearby, but the Huthis shot her with an automatic rifle as she left town. One of my cousins and I tried to reach Sa’da hospital, but soon after we had left ‘Allan in a car with Dardah we reached a Huthi checkpoint and they didn’t let us through.

There were eight Huthis. One, whom the others called Abu Dhar, said, “She is a person who gives bread to the government soldiers, she is an American agent,” and did not let us through. We were there from 8 a.m. until 5 p.m. We pleaded with them, but they did not allow us through. She bled to death. They wore masks so I couldn’t see their faces, and I did not recognize any of them.[164]

V. Overview of Humanitarian Response and Challenges in Assisting Displaced Civilians

Overview of Humanitarian Response

As of mid February, just over 265,000 people had been internally displaced by Yemen’s armed conflict, half of whom were displaced by the sixth round of fighting that began in August 2009 and less than 2o per cent of whom lived in official camps.[165]

Since August 2009, UN agencies and international non-governmental organizations have increasingly published information on the humanitarian situation of civilians affected by the fighting. In September the UN launched its first ever Flash Appeal for the conflict, asking for $23.75 million,[166] while in December the UN in Yemen launched a 2010 appeal for $177 million, tens of millions of dollars of which relate to addressing the humanitarian consequences of the war.[167] As of February 19, 2010, donors had given $763,766 (or 0.4 percent of the appeal), leading John Holmes—the UN under-secretary-general for humanitarian affairs and emergency relief coordinator—to officially classify the humanitarian situation in northern Yemen as an “underfunded emergency” requiring emergency UN funding.[168] On February 4, 2010, John Holmes warned of a funding shortfall, saying that although the humanitarian situation was “without any doubt getting worse and the needs [were] great,” they were “in danger of not being met because the international community, the donors, [had] not responded as [he] would have hoped.”[169]

In September, UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon called for a ceasefire.[170] In early October,John Holmes visited Yemen and called on all involved in the conflict to “ensure the protection of civilians in line with international humanitarian law, to allow [humanitarian agencies] ... to reach those who need assistance, rapidly and without hindrance, and to enable civilians to leave insecure areas.”[171]

Since August 2009, the United Nations, the ICRC, and Yemeni and international partner organizations, including the Yemeni Red Crescent Society, have opened up four camps and started supporting eight informal settlements for new internally displaced persons (IDPs)[172]—seven settlements in Mandaba, Baqim district; one settlement in Khaiwan, Harf Sufyan district; three camps in Mazraq, near Haradh; and one camp in Sa’da town—which joined three pre-existing camps in and around Sa’da town.[173] As of February 13, 2010, there were 45,781 IDPs living in these camps and settlements, or 17 percent of the total number of people displaced by the conflict.[174]As a result of months of pressure from non-governmental organizations and lengthy negotiation between the authorities and aid agencies, in January 2010 UNHCR began registering significant numbers of IDPs in the capital Sana’a. By mid February, 11,853 IDPs were registered, although UNCHR estimated there were at least another 5,000 in the capital.[175]