II. Background

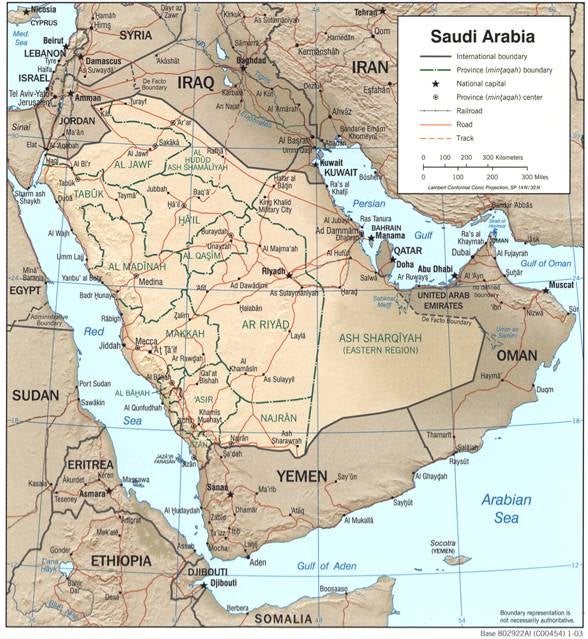

Map of Saudi Arabia. Source: U.S. Central Intelligence Agency, 2003, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Image:Saudi_Arabia_2003_CIA_map.jpg (accessed September 12, 2008)

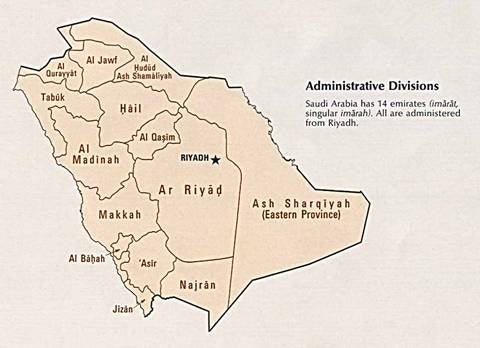

Source: University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin. July, 22, 2008

Najran is the seat of the religious leader of the Sulaimani Ismailis, al-Da’i al-Mutlaq (Absolute Guide). Its status as such, with some interruption, dates back to 1640.3 Ismailis had been living in Najran for over a millennium; they were one of many strands of belief that existed in early Islam. Ismailis called themselves Followers of the Truth (Ashab al-Haqq) and gathered adherents in many parts of the realm of Islam in the ninth and tenth centuries Common Era (CE). A split occurred around the turn of the tenth century, and most Ismailis eventually recognized ‘Ubaid Allah al-Mahdi, a man living in Syria, as their leader (imam). The Mahdi established the Fatimid dynasty (909–1171) in Egypt, founding the city of Cairo and its Azhar university. In the early 12th century another split occurred, and Ismailis in Yemen, where they lived and frequently fought with adherents of Zaidi Islam (another branch of Shia Islam that became prevalent in Yemen), carried forward the beliefs and rule of the Fatimid dynasty.4

Since their emergence, propagandists have depicted Ismailis as heretics, based on invented stories that discredit their beliefs and their claimed ancestry from the Prophet’s family.5

Ismailis have their own system of law; scholars report few modifications or modern adaptations since a series of legal treatises produced by the Fatimid high judge Nu’man in the 11th century.6

Najran, a fertile valley in what is now southwestern Saudi Arabia at the foot of mountains bordering the vast stretch of desert known as the Empty Quarter, was traditionally home to Christian and Jewish communities, in addition to Ismailis and Zaidis. Christians have been absent from Najran for some centuries, and the remaining Jewish community is believed to have left in 1949, following the establishment of the state of Israel. Najran’s Zaidi community today numbers around 2,000.7

The 2004 Saudi census puts the number of inhabitants in Najran at around 408,000.8 Ismailis, widely believed to constitute a large majority of the Najrani population, share a homogeneous identity based on historical, cultural, and religious roots. In Najran city, the Khushaiwa compound, with its Mansura mosque complex, is the spiritual capital of the Sulaimani branch of the Ismaili faith, one of two major strands of contemporary Ismailism. Ismailis in Najran belong mainly to one of two tribes—the Yam and the Hamadan. These tribes extend into territory that today lies in Yemen. There are also some Sunnis of the Yam tribe, both recent converts and adherents to Sunni Islam for generations.

The Saudis conquered first the independent princedom of the Idrisis, in ‘Asir region bordering Najran, in 1926, and then the Ismailis of the Yam tribe in Najran in 1933.9 A brief war with Yemen over ‘Asir concluded with a treaty in 1934 in which Yemen ceded any claims to Najran, then a largely independent sheikhdom, to King Abd al-‘Aziz Al Sa’ud.10 Najran was the last territorial conquest of the reemergent Saudi state.11

The Ismaili sense of pervasive discrimination against them appears stronger today than at any point in the first six decades of Saudi rule. In the 1960s, Saudi authorities had held al-Da’i al-Mutlaq under house arrest variously in Ta’if and Mekka for some five years because he had demanded the independence of Ismaili mosques and religious teaching, which the Wahhabi religious establishment opposed.12 Despite this, many Ismailis have relatively fond memories of Khalid al-Sudairy, who governed Najran from 1962 to 1980, and his son Fahd who succeeded him until 1996. Then, Prince Mish’al bin Sa’ud bin Abd al-‘Aziz Al Sa’ud became the first member of the ruling family to govern the region.

Discrimination against Ismailis in Saudi Arabia is part of a broader trend of discrimination against religious minorities in the country, but has its own dynamic. King Abd al-‘Aziz , also known as Ibn Sa’ud, set out at the beginning of the 20th century to recapture Riyadh and reconquer other parts of the earlier Sa’ud kingdom. He relied on an alliance between his family and the family (the Al al-Shaikh) and followers of Muhammad bin Abd al-Wahhab, the 18th-century missionary and religious scholar. The Al al-Shaikh gave religious legitimacy to the Al Sa’ud as the political rulers, who in turn pledged to uphold Islam.

To that end, Ibn Sa’ud enlisted in Najd the services of experts on religious ritual, the mutawwa’in, or volunteers, putting them in charge of indoctrinating the new tribal fighting force of the ikhwan (brethren), which helped conquer the remaining lands that now comprise Saudi Arabia, including Najran:13 The ikhwan forcibly converted conquered populations to their strict interpretation of Islam, sometimes engaging in mass killings, such as in Ta’if in 1924.14

Intolerance toward other interpretations of Islam remained a feature of Saudi state policies, reflected in discriminatory employment, school curricula, and public expenditures. Following the occupation of the Grand Mosque in Mekka by Sunni millenarian extremists in 1979, and the Islamic revolution in Iran at the same time, the Saudi state reacted with a renewed focus on promoting Wahhabi thought.15

Iran’s example led to increased political demands by the Shia population of Saudi Arabia, who live mostly in the Eastern Province. The Saudi government responded with harsh repression, and many Shia fled. By 1993 Saudi Shia leaders in exile had concluded an understanding with the government allowing them to return as long as they ceased their opposition to the government and worked for change as “loyal subjects” within the kingdom. The authorities, in turn, released Shia political prisoners, lifted travel bans, and took minor steps to ease discrimination against Shia in the public sector and in their religious worship.16 Especially in Ahsa’, the southern part of the Eastern Province, however, suppression of Shia freedom to practice their religion remains widespread.17

While Ismailis face discrimination similar to the Shia of the Eastern Province in employment, religious freedom, and in the justice system, they do not have the same political voice as their Shia brethren to the east. They did not have an organized opposition outside Saudia Arabia or influential coreligionists in a regionally powerful state like Iran, they are far fewer in numbers, and Najran has been more isolated from the outside world than the Eastern Province. One Eastern Province Shia told Human Rights Watch in 2006, “The Ismailis of Najran are where we were 10 years ago.”18

Largely ignored as a supposed backwater in the domestic context of Saudi Arabia for many decades,19 Najran in the late 1990s attracted increased attention. Its proximity to Yemen and the unification of the Yemen Arab Republic (North Yemen) and the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (South Yemen) in 1990, followed by Saudi-Yemeni border negotiations in 1997, gave new impetus to address the fate of tens of thousands of South Yemenis who had taken refuge in Najran. Ismailis vehemently object to the preferred official solution of naturalizing and settling these Yemenis (who are Sunni) in Najran, thereby altering the demographic make-up of the majority-Ismaili region.

3 Heinz Halm, Die Schia (Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 1988), pp. 234-243.

4 Ibid., pp. 193-219. Zaidis are a Shia Muslim sect whose leaders ruled large parts of Yemen for a millennium until 1962.

5 Most of these allegations against Ismailis have been disproved. See Farhad Daftary, “Introduction,” in Farhad Daftary, ed., Mediaeval Isma’ili History and Thought (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1996), pp. 1-18.

6 Ismail K Poonawala, “Al-Qadi al-Nu’man and Isma’ili jurisprudence,” in Daftary, ed., Mediaeval Isma’ili History and Thought, pp. 117-114.

7 Joseph Tobi, The Jews of Yemen: Studies in Their History and Culture (Brill: Leiden, Boston, Köln: 1999), p. 22. In October 1949 Najrani Jews left for Yemen, where Yemeni Jews were preparing to leave to Israel through Aden after Yemen’s Imam Ahmed had issued in May 1949 an official permit for them to leave. Human Rights Watch email correspondence with Israeli academic of Tel Aviv university (name withheld), June 13, 2008.

8 “Makkah Region is Most Populated in Saudi Arabia,” Saudi Info, January 5, 2005, http://www.saudinf.com/main/y7733.htm (accessed February 22, 2008).

9 Isam Ghanem, “The Legal History of 'A Sir (Al-Mikhlaf Al-Sulaymani),” Arab Law Quarterly, vol. 5, no. 3, August 1990, pp. 211-214. Enmity between Wahhabis, who originated in Saudi Arabia’s central Najd region, and the Ismailis of Najran dates from an Ismaili raid close to Dir’iya, the home town of the ruling Sa’ud family, in 1764. See George Rentz, “Wahhabism and Saudi Arabia,” in Derek Hopwood, ed.,The Arabian Peninsula: Society and Politics (Oxford: Allen and Unwin, 1972), p. 57.

10 Askar Halwan Al-Enazy, “‘The International Boundary Treaty’ (Treaty of Jeddah) Concluded between the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the Yemeni Republic on June 12, 2000,” The American Journal of International Law, vol. 96, no. 161, January 2002. King Abd al-‘Aziz Al Sa’ud and Imam Yahya Hamid al-Din, Treaty of Ta’if, May 20, 1934: “His Majesty the Imam Yahya similarly abandons by this treaty any right he claimed in the name of Yemeni unity or otherwise, in the country (formerly) in the possession of the Idrisis or the Al-Aidh, or in Najran, or in the Yam country, which according to this treaty belongs to the Saudi Arabian Kingdom.”

11 In 1934 King Abd al-‘Aziz bin Sa’ud concluded a covenant with the Yam tribe, the dominant tribe in Najran, in which he pledged not to interfere in Ismaili religious affairs and to respect their demographic dominance in Najran by not promoting either their emigration or the immigration of others. Human Rights Watch email correspondence with an Ismaili in Najran, August 22, 2007, and Human Rights Watch interviews with more than six prominent Ismails July 2006 – March 2008. On a visit to the region in November 2006, King Abdullah commented, “[W]hat a pleasure it is for me on this occasion to call to memory the historical covenant between his majesty the unifier King Abd al-‘Aziz, may God have mercy on him, and between the protagonists among your grandfathers and fathers, indeed, as the kingdom was unified through his covenant, you have been loyal.” Ali ‘Awn al-Yami and Hamad Al Mansur, “Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques: Your State Does Not Differentiate between One Region and Another or between One Citizen and Another.” al-Riyadh, November 1, 2006, http://www.alriyadh.com/2006/11/01/article198407_s.html (accessed February 29, 2008).

12 Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Ismaili, IN1, Najran, June 24, 2008.

13 Nadav Safran, Saudi Arabia. The Ceaseless Quest for Security (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1985), p. 54. Safran’s date of 1932 for the conquest of Najran differs from others’ who put the battle at Aba Sa’ud at 1933 or 1934. It is possible that there was more than one battle, or that conversion from hijri into CE dates produced this difference.

14 Rachel Bronson, Thicker Than Oil. America’s Uneasy Partnership with Saudi Arabia (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006), p. 30; and Madawi Al-Rasheed, A History of Saudi Arabia (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002 ) p. 61.

15 Thomas Hegghammer and Stephane Lacoix, “Rejectionist Islamism in Saudi Arabia: The Story of Juhayman al-`Utaybi Revisited,” International Journal of Middle East Studies , vol. 39 (2007).

16 International Crisis Group, “The Shiite Question in Saudi Arabia,” Middle East Report No. 45, September 19, 2005, p. 4; and Human Rights Watch interviews with Shia leaders in Qatif and al-Ahsa’, IQ1 and IA1, February 2006.

17 Human Rights Watch interviews with Shia from Qatif, Tarut, Dammam, and al-Ahsa’, IQ1, IT1, ID1, IA1, February and December 2006, and December 2007.

18 Human Rights Watch interview with a Shia in Qatif, IQ2, February 2006.

19 “I had never really heard of the Ismailis before [Shura Council member] Muhammad Al Zulfa talked to me about their situation.” Human Rights Watch interview with former member of the Shura Council, IR1 Riyadh, December 19, 2006.