Background

In November 2003 a popular uprising following fraudulent parliamentary elections, which became known as the Rose Revolution, ended in the bloodless ouster of the government of President Eduard Shevardnadze. Mikheil Saakashvili, leader of the Rose Revolution, was elected president in January 2004 with 96 percent of the vote. He was enormously popular at home and in the West, but faced significant challenges. Conflict in the breakaway regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia remained frozen, leaving some 220,000-247,000 people internally displaced in Georgia,4 organized crime had laid waste to the economy, widespread corruption paralyzed state institutions, and unemployment and poor economic conditions drove a large portion of the population to seek employment abroad.

President Saakashvili launched a series of institutional reforms—most notably to overhaul the famously corrupt police and judiciary—and prioritized fighting organized crime. He successfully reasserted control over Adjara, a region of Georgia that had refused to cooperate with the central government.

Parliamentary elections in March 2004 gave Saakahsvili’s ruling National Movement party an overwhelming majority in Parliament, and its decisive victory in October 2006 local elections further strengthened the president’s mandate.

In December 2006 the Georgian Parliament amended the constitution to extend the term of the current Parliament and allow for simultaneous presidential and parliamentary elections at the end of 2008. Parliamentary elections were initially scheduled for April 2008, and a presidential election for early 2009.5 In doing so, the government sought to de-link Georgia’s election cycle from two external events that it said risked destabilizing the political environment: the March 2008 presidential election in Russia and the impending determination of a final status for Kosovo.6 Opposition parties opposed the amendments, claiming that the schedule gave an unfair advantage to the National Movement party.7

Georgia’s political opposition has been weak and fragmented. Some analysts have observed that Saakashvili alienated the opposition and others by constantly rebutting criticism and using his supporters’ majority in Parliament to dominate politics and reject constructive dialogue and social consensus on reforms.8 While it is beyond the scope of this report to enumerate all of the opposition’s criticisms of Saakahsvili’s government, it is worth noting that the resignation and then arrest of former Defense Minister Irakli Okruashvili, who had been one of Saakashvili’s closest associates, served to galvanize it.9 Okruashvili was arrested on September 27, 2007, two days after making public statements accusing Saakashvili of corruption and claiming that the latter had instructed him to kill Badri Patarkatsishvili, founder and part-owner of Imedi television.10

The Opposition Demonstrations

Shortly after Irakli Okruashvili’s arrest, 10 opposition parties and movements established the United National Council to coordinate their activities. The council initially issued four main demands to the government, the most important of which was to restore parliamentary elections to their original scheduled date of April 2008. Other demands included the creation of new local election commissions with representatives from political parties; changing the current majoritarian electoral system; and the release of “political prisoners.”11 The opposition also accused Saakashvili of corruption and the use of the police and the judiciary for political purposes.12

The coalition organized a series of protest rallies in Georgia’s regions, including in Kutaisi (October 19), Batumi (October 23), and Zugdidi (October 28). These protests drew between a few hundred and a few thousand peaceful demonstrators. The protest rally in Zugdidi, in western Georgia, turned violent after a group of unidentified men, believed to be security officials, attacked the protestors and severely injured two members of Parliament as they were leaving the demonstration site.13

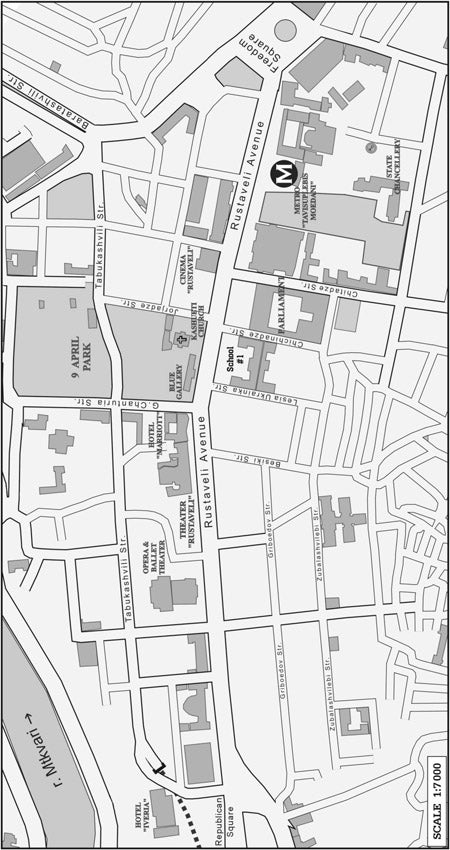

The United National Council also planned for a large rally to be held in front of the Parliament building in the capital, Tbilisi, on November 2. This demonstration attracted over 50,000 protestors,14 making it the largest public demonstration since the Rose Revolution. The demonstrations continued after November 2, although the number of participants rapidly decreased to only 3,000 to 4,000 during the day on November 6.15

While many demonstrators in Tbilisi and other cities joined the protests to express support for the political opposition’s platform, many also participated to express frustrations about continued economic hardship. Despite strong economic growth in recent years and significant progress in structural reforms, the effects of an improved economic climate have been far less significant for ordinary people. Poverty remains widespread in Georgia, particularly outside of Tbilisi.16 According to the International Monetary Fund, unemployment continues to increase and poverty remains at approximately 30 percent.17 Furthermore, the public has increasingly low confidence in the judiciary.18

Until November 3, opposition leaders focused on their original four demands. However, feeling that the government had largely failed to respond to their concerns, opposition leaders’ demands became increasingly strident, ultimately calling for President Saakashvili’s resignation.19

Georgian Media and Imedi Television

Georgia has a vibrant media. There are four main national television stations, including the state-funded National Public Broadcaster, three private stations (Rustavi 2, Mze, and Imedi), as well as a few smaller regional television channels. The Georgian print press is very diverse, but very limited in circulation. The majority of Georgians receives news through the broadcast media.

The popular Imedi television station was founded in 2002 by wealthy businessman Badri Patarkatsishvili, a former close associate of exiled Russian tycoon Boris Berezovsky. Imedi became increasingly critical of the authorities after Patarkatsishvili fell out with Saakashvili’s government in 2006, allegedly amidst business disputes. The station aired investigative pieces into controversial subjects, including on the murder of Sandro Girgvliani, head of United Georgian Bank’s international relations department, by Ministry of Interior employees in January 2006.20 Government officials criticized Imedi, calling it an opposition mouthpiece, and refused all invitations to participate in debates or talk shows on Imedi.21

In August 2006 News Corporation, run by media mogul Rupert Murdoch, acquired a 49 percent stake in Imedi. Patarkatsishvili retained 51 percent of the shares.22 Lewis Robertson, a News Corp executive, was named CEO of Imedi.23 On October 31, 2007, Patarkatsishvili announced that he would sell an additional 2 percent of Imedi shares to News Corp to give it a controlling stake and transfer the management rights of his shares in Imedi to News Corp for one year. The transfer came three days after Patarkatsishvili announced his decision to finance the campaign of Georgia’s united opposition.24 The Georgian government has claimed that despite the October deal, Patarkatsishvili retained effective control over the television company, and dictated its editorial policy to advance his personal political goals.25 Patarkatsishvili and News Corp deny these allegations.26

The Coup d’Etat in Recent Georgian History

Coups, attempted coups, and government allegations of coups have featured prominently in Georgia since the collapse of the Soviet Union. Georgia’s first president, Zviad Gamsakhurdia, faced several coup attempts27 and was ousted on January 6, 1992, after two weeks of bloody fighting in Tbilisi. 28 Following Gamsakhurdia’s ouster, Georgia was plunged into civil war and political chaos for almost two years. In this period several coup attempts were made by Gamsakhurdia and his supporters, including on June 25, 1992, when Gamsakhurdia supporters seized the television and radio center in Tbilisi and urged people to gather and demand the return of the deposed president.29

During his 11 years as Georgia’s leader, Eduard Shevardnadze survived repeated assassination attempts, and his government also alleged at various times the existence of plots to overthrow it.

In November 2003, following parliamentary elections that were largely considered fraudulent, thousands of demonstrators gathered on the streets of Tbilisi to protest the election results. On November 22, opposition leaders, including Mikheil Saakashvili, stormed the Parliament building and forced President Shevardnadze to resign the next day.

Since 2003 the Georgian government has alleged a number of coup attempts. On July 22, 2006, Emzar Kvitsiani, the leader of an illegal militia in the Upper Kodori Gorge region of Abkhazia (the only part of Abkhazia still under Tbilisi's control), announced that he refused to disband his militia as requested by the government and no longer recognized the government’s rule in the area. Georgian troops entered the area and Kvitsiani fled Georgia. On July 29, police arrested Irakli Batiashvili, former security minister and leader of the small opposition Forward Georgia movement, on charges of failing to report a crime and assisting a coup attempt by providing “intellectual support” to Kvitsiani. The allegations were in part based on a secret recording of a phone conversation between Kvitsiani and Batiashvili on July 26, in which Batiashvili allegedly conveyed his view of public support for Kvitsiani. Irakli Batiashvili was sentenced to seven years’ imprisonment in May 2007.

On September 6, 2006, Georgian police detained 29 supporters and allies of former security minister Igor Giorgadze, now a fugitive living in Russia, and charged 14 of them with treason and plotting to overthrow the government. Georgian authorities accused the Russian government of financing the coup attempt.30 Thirteen of those charged were sentenced in August 2007 to prison terms of up to eight years and six months for plotting a coup, following a closed trial.31

Relations between Russia and Georgia

Political tensions between Russia and Georgia have persisted since South Ossetia and Abkhazia attempted to secede from Georgia prior to and following the collapse of the Soviet Union. Although both South Ossetia and Abkhazia remain de facto independent since early 1990s, neither Georgia nor the international community recognizes the regions’ claims to independence. For many years, Georgian authorities have accused Russia of secretly supporting the separatist movements in both regions.32

After coming to power in 2004, President Saakashvili took an openly pro-Western stance, seeking political, economic, and military cooperation with the European Union (EU) and the United States (US), including membership in NATO.33 Russia openly opposes Georgia’s NATO aspirations.34

In 2006, Russia, a major market for Georgian exports, initiated a series of import restrictions on Georgian goods, including wine, mineral water, vegetables, and fruits.35 On September 27, 2006, Georgian police arrested four Russian military intelligence officers, whom it accused of espionage. In response, Russia effectively introduced economic sanctions against Georgia, beginning with a halt to all air, land, and sea traffic, as well as postal communication.36 Russia recalled its ambassador to Georgia and stopped issuing visas to Georgians.37 Russian police undertook widespread inspections and closures of Georgian businesses in Russia and stopped, detained, and expelled thousands of ethnic Georgians from Russia.38

In November 2006 Russia’s state-controlled natural gas company, Gazprom, threatened to more than double the price of gas supplies to Georgia for 2007, and Georgia accepted the price increase after Gazprom threatened to cut off supplies. 39

In March 2007 Georgia claimed that Russian combat helicopters fired on villages in the Upper Kodori Gorge region of Abkhazia. A September report by the United Nations Observer Mission in Georgia said that it was not clear who had fired at the Georgian territory.40 In August 2007 Georgia alleged that a Russian attack aircraft violated Georgian airspace and dropped a guided missile, which did not explode, near two villages approximately 80 kilometers south of the Russian border. Russia denied the allegation.41 Tensions remained high in September and October 2007 after a series of incidents involving Russian peacekeeping troops in Abkhazia and South Ossetia.

5 “Georgian Parliament Approves Proposed Constitutional Amendments,” RFE/RL Newsline, December 29, 2007, http://www.rferl.org/newsline/2006/12/2-TCA/tca-291206.asp (accessed December 6, 2007).

6 President Saakashvili was quoted as saying, “It is too risky for Georgia to have elections in spring, at the time when presidential elections are also held in Russia [March 2008]. In January or February [2008] the fate of Kosovo will be decided and it is most likely that it will be internationally recognized. Russia made it clear it planned to recognize Abkhazia and South Ossetia in case of Kosovo’s recognition, which in turn means a risk of having confrontation. That is why we have decided to shorten the president’s term in office for at least eight months and to prolong the parliament term in office.” See “Confrontation Deepens as Saakashvili Rejects Early Polls,” Civil Georgia, November 5, 2007, http://www.civil.ge/eng/article.php?id=16190 (accessed November 29, 2007).

7 “Ruling Majority Stands Firm on Constitutional Amendments,” Civil Georgia, December 13, 2006, http://www.civil.ge/eng/article.php?id=14290 (accessed December 5, 2007). The Council of Europe’s Venice Commission criticized the amendments. European Commission for Democracy Through Law (Venice Commission), “Opinion on the Draft Constitutional Law of Georgia on Amendments to the Constitution,” 69th Plenary Session of the Commission, December 15-16, 2006, http://www.venice.coe.int/docs/2006/CDL-AD(2006)040-e.pdf (accessed December 3, 2007).

8 Uwe Klussmann, “Ruckus in the Caucasus: Saakashvili’s Firm Grip in Georgia,” Der Spiegel (Hamburg), June 12, 2006, http://www.spiegel.de/international/spiegel/0,1518,421518,00.html (accessed November 29, 2007).

9 In addition, a number of government actions drew sharp criticism from the opposition, among them the killing of Sandro Girgvliani, head of United Georgian Bank’s international relations department, by Ministry of Interior employees in January 2006. Girgvliani’s body was found on the outskirts of Tbilisi bearing signs of a severe beating. In July 2006, four Ministry of Interior employees were convicted of causing the injuries that resulted in Girgvliani’s death, and were sentenced to prison terms. However, many believe that the senior ministry officials involved in the disagreement with Girgvliani had ordered his kidnapping and beating but escaped prosecution. Paul Rimple, “Murder Case Verdict Stirs Controversy,” EurasiaNet, July 7, 2006, http://www.eurasianet.org/departments/civilsociety/articles/eav070706.shtml (accessed December 6, 2007).

10 Okruashvili was jailed on corruption charges, and was eventually released on bail after he publicly retracted his statements. The night before the November 2 rally, he left Georgia, allegedly under pressure from the Georgian authorities. He was arrested in Germany on November 27 and awaits an extradition hearing. Salome Asatiani, “German Police Hold Wanted Former Georgian Defense Minister,” RFR/RL, November 29, 2007, http://www.rferl.org/featuresarticle/2007/11/BC56A494-CC43-4084-9B3A-4C02DE9A8966.html (accessed December 6, 2007).

11 “Opposition Vows to Keep Protesting,” Civil Georgia, November 2, 2007, http://www.civil.ge/eng/article.php?id=16166 (accessed December 2, 2007).

12 “Georgia, No Peace I Find,” The Economist (London), November 10, 2007, http://www.economist.com/daily/news/displaystory.cfm?story_id=10110247&top_story=1 (accessed December 3, 2007); and “Georgia’s Leader Calls Early Elections to Decide His Fate,” New York Times, November 9, 2007, http://www.nytimes.com/2007/11/09/world/europe/09georgia.html?_r=1&ref=world&oref=slogin (accessed December 2, 2007).

13 “Opposition want Criminal Proceedings against ‘Zugdidi Attackers,’” Civil Georgia, October 30, 2007, http://www.civil.ge/eng/article.php?id=16134 (accessed on November 27, 2007).

14 The number of protesters is disputed. Some opposition leaders claim that there were over 100,000 participants.

15 Human Rights Watch interview with Shota Utiashvili, head, Analytical Department, Ministry of Interior, Tbilisi.

November 15, 2007.

16 Annual GDP Growth is nearly 10 percent. “People Power,” The Economist, November 8, 2007, http://www.economist.com/world/europe/displaystory.cfm?story_id=10113464 (accessed December 3, 2007). The World Bank’s 2008 Doing Business project, which ranks 178 countries on the ease of doing business, ranked Georgia 18th. Doing Business 2008, http://www.doingbusiness.org/ExploreEconomies/?economyid=74 (accessed December 3, 2007). The project named Georgia the top reformer in the world in 2006. “Doing Business: Georgia is This Year’s Top Reformer,” September 6, 2006, http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/COUNTRIES/ECAEXT/GEORGIAEXTN/0,,content

MDK:21042336~pagePK:141137~piPK:141127~theSitePK:301746,00.html (accessed December 3, 2007).

17 Official rate of unemployment increased from 12.6 percent in 2004 to 13.9 percent in 2006. ![]() International Monetary Fund, “Georgia: Sixth Review under the Three-Year Arrangement Under the Poverty Reduction and Growth Facility and Request for Waiver of Performance Criteria,” August 2007, IMF Country Report No. 07/299. In a 2007 Poll by the International Republican Institute, respondents overwhelmingly stated that their top concerns were unemployment and “economy” as well as territorial integrity. International Republican Institute, “Georgian National Voter Study,” August 31-September 10, 2007, http://www.iri.org.ge/eng/engmain.htm (accessed December 3, 2007). The same priorities were registered in a February 2004 poll. International Republican Institute, “Georgian National Voter Study,” February 2004, http://www.iri.org.ge/eng/engmain.htm (accessed December 3, 2007).

International Monetary Fund, “Georgia: Sixth Review under the Three-Year Arrangement Under the Poverty Reduction and Growth Facility and Request for Waiver of Performance Criteria,” August 2007, IMF Country Report No. 07/299. In a 2007 Poll by the International Republican Institute, respondents overwhelmingly stated that their top concerns were unemployment and “economy” as well as territorial integrity. International Republican Institute, “Georgian National Voter Study,” August 31-September 10, 2007, http://www.iri.org.ge/eng/engmain.htm (accessed December 3, 2007). The same priorities were registered in a February 2004 poll. International Republican Institute, “Georgian National Voter Study,” February 2004, http://www.iri.org.ge/eng/engmain.htm (accessed December 3, 2007).

18 In a survey conducted in 2004, the Eurasia Foundation’s Caucasus Research Resource Center (CRRC) found that 36 percent of respondents said that they fully or somewhat distrusted the judicial system; the figure increased to 37 percent in 2005 and 62 percent in 2006. CRRC, “2006 Data Initiative Survey for Georgia and the South Caucasus. Introduction, Results and Application,” http://www.crrccenters.org/index.php/en/11 (accessed December 3, 2007).

19 “Opposition Demands Saakashvili’s Resignation,” Civil Georgia, November 3, 2007, http://www.civil.ge/eng/article.php?id=16179 (accessed December 5, 2007). In a televised interview on November 4, 2007, President Saakashvili referred to the opposition as a “dark, black, 100 % negative force,” “Full Text: Transcript of Saakashvili’s Televised Interview,” Civil Georgia, November 5, 2007, http://www.civil.ge/eng/article.php?id=16195 (accessed November 22, 2007). See also “No Signs of Compromise as Opposition Vows to Keep Protesting,” Civil Georgia, November 2, 2007, http://www.civil.ge/eng/article.php?id=16172 (accessed December 5, 2007.)

20 Molly Corso, “Murdoch-Affiliated Broadcaster in Georgia Generates Controversy,” EurasiaNet, March 21, 2007, http://www.eurasianet.org/departments/civilsociety/articles/eav032107.shtml (accessed December 3, 2007). For more on the Girgvliani murder see above, footnote 9.

21 “News Ban Bodes Ill for Democracy,” Newsweek, November 11, 2007, http://www.newsweek.com/id/69785/page/1 (accessed December 2, 2007); and “News Corp. Takes Management of Patarkatsishvili’s Imedi Shares,” Civil Georgia, October 31, 2007, http://www.civil.ge/eng/article.php?id=16145 (accessed December 3, 2007).

22 “Newscorp buys Georgian media group- report,” Reuters, October 31, 2007, http://www.reuters.com/article/mergersNews/idUSL31741020071031 (accessed December 3, 2007).

23 “News Corp to Appeal License Suspension in Georgia,” Agence France-Presse as carried by Yahoo News, November 14, 2007, http://news.yahoo.com/s/afp/20071114/bs_afp/georgiapoliticsmediacompanynewscorp_071114175256 (accessed December 3, 2007).

24 Stefan Wagstyl and Quentin Peel, “Georgian TV Chief Turns to Rupert Murdoch,” Financial Times (London), November 1, 2007, http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/0c01a0cc-8810-11dc-9464-0000779fd2ac.html (accessed December 10, 2007); and Giorgi Lomsadze, “Georgia: With Rupert Murdoch as an Ally, Billionaire Pledges Big Bucks for Opposition,” EurasiaNet, October 31, 2007, http://www.eurasianet.org/departments/insight/articles/eav110107a.shtml (accessed December 2, 2007).

25 “Authorities Want Imedi to Change Hands,” Civil Georgia, November 28, 2007, http://www.civil.ge/eng/article.php?id=16447 (accessed November 29, 2007).

26 Molly Corso, “Tbilisi to News Corp: Show us the Ownership Documents for Pro-Opposition TV Station,” EurasiaNet, December 3, 2007, http://www.eurasianet.org/departments/insight/articles/eav120307.shtml (December 3, 3007).

27 See, for example, “Foes of Georgia’s Leader Seize Republic’s Station,” New York Times, September 23, 1991, http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9D0CE7D71030F930A1575AC0A967958260 (accessed December 2, 2007).

28 John Kohan, “Georgia Descending into Chaos,” Time, January 20, 1992, http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,974693-1,00.html (accessed December 2, 2007).

29 Serge Schmemann, “Shevardnadze Dodges a Coup and Ends a War,” New York Times, June 25, 1992, http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9E0CE7D8153FF936A15755C0A964958260&sec=&spon=&pagewanted=print (accessed December 2, 2007).

30 Diana Petriashvili, “Georgian Opposition: Coup Arrests are Campaign Tactic,” EurasiaNet, September 13, 2006, http://www.eurasianet.net/departments/insight/articles/eav091306.shtml (accessed December 2, 2007).

31 “Supporters of Fugitive Georgian Ex-Minister Sentenced”, RFE/RL Newsline, August 27, 2007, Vol. 11, No. 158, http://www.rferl.org/newsline/2007/08/270807.asp (accessed December 5, 2007.)

32 International Crisis Group, “Abkhazia: Ways Forward.” See also “Full Text: Saakashvili’s Address at UN General Assembly-2006,” Civil Georgia, http://www.civil.ge/eng/article.php?id=13622 (accessed November 22, 2007).

33 In September 2006 NATO offered Georgia an Intensified Dialogue, in recognition of Georgia’s aspirations to join the organization. However, Georgia will move on to the next step of the NATO accession process (the Membership Action Plan, MAP) only if it implements reforms. See “Georgia Moves Closer to NATO Membership, but Reforms Must Continue,” NATO Parliamentary Assembly press communique, April 24, 2007, http://www.nato-pa.int/Default.asp?SHORTCUT=1191 (accessed May 15, 2007), and NATO, “NATO-Georgia Relations,” May 2, 2007, http://www.nato.int/issues/nato-georgia/index.html (accessed May 15, 2007).

34 See Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, “A Survey of Russian Federation Foreign Policy,” http://www.mid.ru/Brp_4.nsf/arh/89A30B3A6B65B4F2C32572D700292F74?OpenDocument (accessed May 15, 2007).

35 “Russia Extends Georgian, Moldovan Wine Ban,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (RFE/RL), April 6, 2006, http://www.rferl.org/featuresarticle/2006/04/f813834f-6fd6-4b60-a6c8-77e2a48d5553.html (accessed May 16, 2007); Maria Levitov, “Russian Ban on Georgian Mineral Water,” St. Petersburg Times, May 12, 2006, http://www.sptimes.ru/index.php?action_id=2&story_id=17547 (accessed May 16, 2007); “Bans Cost Georgia $100M,” The Moscow Times, May 16, 2007, http://www.themoscowtimes.com/stories/2007/05/16/061.html (accessed May 16, 2007).

36 “Transportation blockade of Georgia” (“Transportnaya blokada Gruzii”), Kommersant (Moscow), no. 184 (3515), October 3, 2006, http://www.kommersant.ru/doc.aspx?DocsID=709686 (accessed August 1, 2007); and “How the Russian government explains the introduction of sanctions against Georgia” (“Kak rossiiskie vlasti obiasniaiut vvedenie sanktsii protiv Gruzii”), Kommersant, No. 184 (3515), October 3, 2006, http://www.kommersant.ru/doc.aspx?DocsID=709684&print=true (accessed August 1, 2007).

37 Prior to the ban, Russia had issued approximately 100,000 visas per year to Georgians. “Vizi dobroi voli,” (“Visas of good will”), Vremya Novostei (Moscow), July 20, 2007, http://www.vremya.ru/2007/127/5/183126.html (accessed August 2, 2007); and “Russia Partially Resumes Visas for Georgia,” CivilGeorgia, May 29, 2007, http://www.civil.ge/eng/article.php?id=15185 (accessed June 25, 2007).

38 Human Rights Watch, Singled Out: Russia’s Detention and Expulsion of Georgians, vol. 19, no. 5(D), October 2007, http://hrw.org/reports/2007/russia1007/5.htm#_ftn26; See also “Anti-Georgian campaign” (“Antigruzinskaia kampania”), Lenta.ru, http://lenta.ru/story/antigeorgia/ (accessed April 17, 2007).

39 Neil Buckley, “Russia Threatens to Double Gas Price to Georgia,” Financial Times (London), November 2, 2006, http://www.ft.com/cms/s/2c275652-6a58-11db-83d9-0000779e2340.html (accessed August 6, 2007); “Gazprom to Double Georgia Charges,” BBC News Online, November 2, 2006, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/business/6108950.stm (accessed August 6, 2007); and “Georgia ‘Agrees Russia Gas Bill,’” BBC News Online, December 22, 2006, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/business/6203721.stm (accessed August 6, 2007).

40 “Georgia Lashes out at Russia Over Attack,” Reuters, March 14, 2007, http://www.reuters.com/article/latestCrisis/idUSL14608394 (accessed December 3, 2007); and “Russia Accuses Georgia over Attack,” CNN, August 9, 2007, http://www.cnn.com/2007/WORLD/europe/08/09/russia.georgia.ap/index.html (accessed December 3, 2007).

41 Michael Schwirtz and Jon Elsen, “Georgia accused Russia of Missile Attack; Russia Denies it,” New York Times, August 8, 2007, http://www.nytimes.com/2007/08/08/world/europe/08georgia.html?_r=1&oref=slogin (accessed December 3, 2007).