<<previous | index | next>>

IV. Prolonged Pre-trial Detention in Guinean Prisons

Once charged with a crime, detainees are transferred from police custody to prison where many of them are left to languish for years before being brought to trial. As a result, hundreds of individuals in Guinea accused of crimes such as petty theft, robbery, assault, and murder are held in prolonged detention before a determination of their guilt or innocence can be made by a court of law. As described above, many of these individuals are in prison based on a confession extracted under police torture. Most are held in the Maison Centrale prison in Conakry.26

Of the approximately one thousand men, women, and children currently held in the Maison Centrale, between70 and 80 percent are still awaiting trial.27 Human Rights Watch interviewed twenty detainees who have spent more than four years in the Maison Centrale without trial, including two children; six had been there for over six years.28 One individual told Human Rights Watch that he has been in prison since 1991 without trial.29 While one of the three wings of the Maison Centrale is known as the “hallway of the convicted,” pre-trial detainees are mixed in with convicted prisoners throughout the three wings.30

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights provide for the right to be tried within a “reasonable time.”31 The Guinean Code of Criminal Procedure provides that suspects should be brought to trial within four months of being brought to prison as a pre-trial detainee, unless an investigating magistrate authorizes an extension.32 However, according to one criminal defense lawyer interviewed by Human Rights Watch, such procedures are never observed and after four months have passed, many detainees are simply forgotten. UN officials and local human rights defenders told Human Rights Watch that they view prolonged pre-trial detention as a serious problem.33

A major contributing factor to the problem of prolonged pre-trial detention is that, under Guinean law, individuals accused of a serious crime such as armed robbery, murder or rape may only be tried before a particular court, known as the Cour d’Assise.34 Under Guinean law, the Cour d’Assise is required to hold a session once every four months.35 However, because the Cour d’Assise has only met twice since 2000 and it only hears a small number of cases per session, individuals accused of a serious crime are often forced to wait years for a trial.36

An official with the Ministry of Justice responsible for oversight of the Cour d’Assise told Human Rights Watch that holding more regular sessions is a challenge due to the money required, but that he expects to hold a session later this year that should “absolutely” resolve all outstanding problems with pre-trial detainees.37

Prolonged pre-trial detention is also attributable in part to poor record keeping. For example, the detainee who reported that he has been in prison without trial since 1991 told Human Rights Watch that his file was lost by the authorities during his transfer to the Maison Centrale in the early 1990s. Another group of at least five detainees were held in limbo at the Maison Centrale for over five years because a fire at one of the courthouses in Conakry in the late 1990s destroyed their files.38 Although a local criminal defense lawyer interviewed by Human Rights Watch has succeeded in freeing four of them, one of them remained in prison at the time of Human Rights Watch’s visit (he claimed he has been in prison since 1997 without trial), and explained his situation as follows:

I am accused of theft. After my arrest, I spent two days at the police station, where I was hung from the ceiling and beaten with a club until I agreed to confess. After coming to prison, an investigating magistrate came to interview me, but I have never had a trial. Later I was told that my file was destroyed in a fire, so I am still here. Those with relatives who can pay can get out of here, but my family is dead, so there is no money to pay them.39

Poor record keeping may also be the reason that some detainees have been kept for several years after they had served their sentence.40

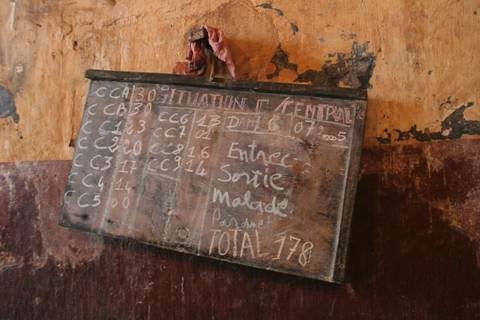

A chalkboard in one of the three wings of the Maison Centrale in Conakry is used to keep track of the number of prisoners in different cells.

© 2005 Kim

Osborn

[26] The Maison Centrale, like all civilian prisons in Guinea, falls under the authority of the Ministry of Justice.

[27] Human Rights Watch interviews with National Director of Penal Administration (Directeur National de l’Administration Pénitentiaire) Naby Youssouf Sylla, June 22, and with a local prisoners’ advocacy organization, Conakry, June 14, 2006. While the Maison Centrale in Conakry undoubtedly houses the highest number of pre-trial detainees, other prisons in Guinea, such as Faranah and N’zérékoré, also contain high ratios of unsentenced to convicted prisoners. Human Rights Watch interview with local prisoners’ advocacy organization, Conakry, June 14, 2006.

[28] Human Rights Watch interviews with prisoners and detainees, Conakry, June 20 and 23, 2006.

[29] Human Rights Watch interview with a detainee, Conakry, June 20, 2006.

[30] Under the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners, Article 8(b), “Untried prisoners shall be kept separate from convicted prisoners.” The United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners, adopted by the Economic and Social Council in 1957, is one of the most long-standing norms on the human rights of all those deprived of their liberty, and is widely considered an authoritative guide as to how governments may comply with their obligations under international law.

[31] ICCPR, Article 9; African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, Article 7.

[32] Guinean Code of Penal Procedure, 1998, Article 142; Human Rights Watch interview with criminal defense lawyer, Conakry, June 16, 2006.

[33] Human Rights Watch interviews with UN officials and local human rights defenders, Conakry, April 2 and 6, 2006.

[34] Guinean Code of Penal Procedure, 1998, Article 232. Human Rights Watch interviews with a local prisoners’ advocacy organization and with officials of the Ministry of Justice, Conakry, June 2006.

[35] Guinean Code of Penal Procedure, 1998, Article 235.

[36] Human Rights Watch interviews with a local prisoners’ advocacy organization, a criminal defense lawyer, and officials of the Ministry of Justice including General Prosecutor for the Court of Appeals (Procureur Général de la Cour d’Appel) Yves William Aboly and National Director of Penal Administration Naby Youssouf Sylla, Conakry, June 2006.

[37] Human Rights Watch interview with General Prosecutor for the Court of Appeals Yves William Aboly, Conakry, June 28, 2006.

[38] Human Rights Watch interviews with a local prisoners’ advocacy organization, June 14; with a criminal defense lawyer, June 16; and with National Director of Penal Administration Naby Youssouf Sylla, Conakry, June 22, 2006.

[39] Human Rights Watch interview with a detainee in the Maison Centrale, Conakry, June 20, 2006.

[40] A local criminal defense lawyer told Human Rights Watch that he has recently managed to free two such prisoners. A local prisoners’ advocacy organization told Human Rights Watch that they have recently worked with the prison authorities to computerize the list of prisoners so that such incidents should no longer occur. Human Rights Watch interviews, Conakry, June 14, 2006.

| <<previous | index | next>> | August 2006 |