<<previous | index | next>>

V. Abuses Against Street Children

On the streets, their situation is precarious. Street kids live in dirtiness and total insecurity. They have no rights and no access to education, healthcare or security. They are victims of different types of violence––they are beaten and kicked, they are victims of sexual violence, both girls and boys, and they are at risk of economic exploitation. Bandits and gangs, the police, and the military use and abuse these children. Girls are especially vulnerable to rape and sexual assault by military and sentinels who guard offices and buildings at night.

—Mme. Bashizi Mulangala, Division of Social Affairs and the Family, September 15, 2005

Police and Military Abuse

Some police officers help to reintegrate street children with their families and protect them from abusive adults. For example, in Goma we noted the positive role of the Special Police for the Protection of Children (see sub-section below). But many street children live in fear of the forces meant to protect them and all other civilians. Ordinary police, military police and soldiers threaten, rob, beat, and harass children during the day and at night when they are sleeping. Under threat of arrest and imprisonment, children are forced to hand over money or material goods to men in uniform.

In the worst cases, police officers recruit children to steal and loot in exchange for a share of the booty or a small sum of money.8 More generally, the police use street children to assist in sting operations, provide surveillance at the scenes of robbery, or to act as decoys. Street children are also forced to provide information on the whereabouts of other street children or other people suspected of crimes. Children who perform these activities on behalf of the police risk imprisonment or beating for failing to comply.

Physical abuse

In Goma in eastern DRC, street children mentioned the particularly abusive nature of soldiers and military police who are responsible for security in the town. According to one seventeen-year-old street boy, it is the military police, not the civilian police, who approach them at night and take their money, shoes or clothes. Those who resist are beaten.9 Emmanuel, a fourteen-year-old orphan, who sleeps in an abandoned kiosk with several friends, told us, “Life is hard here in the streets, we are all the time harassed by the military. They come at night, any time after 10:00 p.m. They beat us with their hands or kick us with their boots. They regularly demand money or items they can sell, like mobile phones. Only those who run away and don’t get caught are safe. If we have worked all day for 100 francs (U.S.$0.20) they can even take that.”10 Fourteen-year-old Raphael, who sleeps with his friends in empty kiosks near the Virunga market in Goma, told us, “We are regularly harassed by the military police. In the evenings, they come to where we are sleeping and take whatever they can from us. We are chased and if caught, they beat us with their fists of pieces of wood.”11 Many of the children whose interviews with Human Rights Watch in Goma and other cities are described elsewhere in this section also mentioned beatings by police or military personnel.

Several employees of a center for street children in Goma linked the demeanor of children at the center during the day with the events of the preceding night. They reported that soldiers and military police chase the kids, beat them, and steal their money and goods. They told us that the following day at the centers, the kids recount to staff members their stories of police harassment and abuse and their desire to sleep, exhausted from running from the police at night.12

In Mbuji-Mayi, Lubumbashi, and Kinshasa, street children reported that some police officers harassed them at night, kicking, slapping or beating them. Children in Lubumbashi told us that they also risked abuse from police officers for playing in the squares or markets, or when groups of them try to congregate. Unlike in Goma where such abuse was regularly reported by street children, in these cities children told us that they were sometimes able to avoid such police harassment by not bringing attention to themselves. One street youth in Lubumbashi offered this explanation, “If you are stealing things or looking for trouble, this is when you risk beatings or arrest. One time I was guarding a car with friends. When the patron [owner] paid us, we started fighting over the money. The police arrived, arrested us, and later, beat us for the disturbance.”13

Extortion

A street child’s ability to avoid physical abuse or arrest

can be contingent on furnishing money to the police. As described in more

detail below (see sub-section

“Arbitrary arrests and roundups”), in the DRC children found in the street can

be charged with vagrancy, brought before a judge, and by law should be either

reunited with their families or placed in a public or private institution. In

very few cases does this actually happen. Instead, police can use the threat of

arrest or prolonged detention to extort money from children.

A street child asleep on the street. At night,

street children are at particular risk of physical and sexual abuse by adults

and law enforcement personnel.

© 2005 Marcus Bleasdale

According to twelve-year-old Noah, “Around the Olympia bar area at night, the money we have is often stolen by members of the military police. They come and rough us up, threatening to beat or arrest us if we don’t give them what we have. Or, if they see a nice piece of clothing, they take it from us.” Noah is from Goma and has lost his parents to disease. At night, he sleeps with a group of his age-mates under old sacks or flattened, cardboard boxes, on verandas.14 A former street boy named Benjamin told us that during his time on the street, he would never sleep in the same place for too many nights in a row because the police would harass him. “At night, the police would come and we would have to run. If they caught you, they would take things from your pockets and then let you go. They would hit us with their fists and intimidate us.”15

Street children are often the first suspects when money or goods are stolen in areas where they congregate. Police roundup groups of street children suspected of crimes and detain them for investigation. In some cases, police officers beat street children during interrogation to obtain information or a confession about a crime, and later demand payment for their release. According to the seventy-nine street children interviewed for this report, beatings during interrogation are frequent in Goma and Lubumbashi but appear to be less common in Mbuji-Mayi and Kinshasa.

Emmanuel, an orphan from Goma, told us that in March 2005 police conducted a roundup of street children who spend time at the Virunga market because U.S.$150 had been stolen from a merchant. Twenty-six children were arrested, interrogated, and for those who could not pay a bribe, detained for three days in the police lockup next to the market. Emmanuel reported that the police beat him on the back and buttocks with a baton during the interrogation.16 Peter, in Lubumbashi, left home because he hoped life would be better on the streets––he didn’t get enough to eat at home and he couldn’t go to school because his mother couldn’t afford the cost of primary education. He said that one time he was arrested in early 2005 for playing in a square with other street boys. The police demanded 500 Congolese francs (U.S.$1) from him for his immediate release. He didn’t have the money and so was detained for several days in the lockup. According to Peter, during his detention the police kicked him.17

Fifteen-year-old Frederic from Lubumbashi said:

I have had problems with the police. There was theft of cooking oil at the factory near the market. I don’t know who was involved. But the police were there and they picked us up and brought us to the police station at the market. I was beaten on the feet with a large stick that is used for making fufu (corn or cassava meal). I was tied up at the arms and ankles during the beating. The other boys paid the police some money and were immediately released. I spent several days at the station.18

Seventeen-year-old Rebecca told us that in 2005, “a few kids were stealing from the market, and the police arrested a whole group of street kids in the area. We were more than twenty kids in one small room at the lockup. We were whipped with a plastic cord on the buttocks. The kids would cry and scream. My friends paid the police 400 francs (U.S. $0.80) to make them stop, I was released that day.”19

Sexual abuse of girls

Some members of the police and military take advantage of the vulnerability of street girls, raping and sexually assaulting them. Many of these girls are already survivors of rapes, often multiple rapes, committed by civilian street boys and men (sexual abuse by civilians is discussed later in this chapter). Counselors at one center for street girls reported that girls will talk about rape and sexual violence that they experienced on the streets, but it takes time and counseling. Many girls feel shame in recounting the stories of sexual abuse and will not give the names of individual police or soldiers, either because they don’t know the perpetrators, they fear retaliation, or both. According to these counselors, girls at their centers, some as young as ten years old, regularly speak of soldiers, police, and men in uniform who rape street girls, demand sex in exchange for protection or release from custody, or offer them small amounts of money for sex.20

Thirteen-year-old Margaret, physically abused by her stepmother at home, ran away to live on the streets. She passed her days collecting pieces of charcoal that had fallen to the ground at distribution sites to later re-sell to get enough money to buy food. She told Human Rights Watch:

In early 2005, men in uniform arrested all the kids in the market and we were confined in a house nearby. Those men said we were under arrest because their superiors had given orders that all children should get off the street. They arrested many boys and girls. Some of the boys were beaten but not the girls. The soldiers slept with some of the older girls. They said, ‘if you don’t sleep with us, we won’t let you go.’ So, many of the girls accepted. They said the same thing to me, but I was spared because a nun came and secured my release. Who could do something like this?21

An official in the provincial Division of Women and the Family reported that the vast majority of street girls are victims of rape, including multiple gang rapes. In addition to civilians, she cited soldiers and police officers as being responsible for the sexual abuse of street girls. In her work, she has uncovered that perpetrators during these crimes, rarely, if ever, use condoms, leaving girls at risk of sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV/AIDS. According to her, sexual violence against girls further complicates their rehabilitation and makes it more difficult for successful reintegration with their families, particularly in cases where girls have children born of rape. Girls who are survivors of rape can be as young as eight years old.22

Studies done on the sexual abuse of girls and women in DRC support these findings. In one study conducted in Lubumbashi in 2003, all of the fifty street girls interviewed reported sexual violence. The girls named soldiers and the police among those responsible for the rapes. The author of the study concluded that street girls have little protection or redress from abuse and that the perpetrators of these rapes take advantage of their vulnerability.23 Another study conducted in eastern DRC included numerous examples of rapes and other acts of sexual violence in Goma and other cities in the east, committed by soldiers and members of the police.24

Police misuse of street children

Street children who are rounded up during police operations or accused of crimes, can be forced to perform labor while in detention: some roundups even appear to be with the express purpose of getting free labor for menial tasks. For example, children report that they are often made to dig latrines and clean cells when held in police lockups. One boy who spends his time at the Star roundabout in Mbuji-Mayi told us that in August 2005 he and his friends were rounded up by the police and forced to dig pit latrines at the central prison. According to him, eighteen boys aged ten to seventeen were tied up, walked to the prison, and made to dig three holes for pit latrines, labor that took them all day to finish. At the end of the day, the commandant of the police gave them each 200 Congolese francs (U.S.$0.40) to buy soap to wash themselves.25

Timothy, who lost both his parents to HIV/AIDS, was living at the central market in Mbanza-Ngungu in the province of Bas-Congo. In 2004, the police rounded up a large group of children in the market and detained them in a lockup. According to Timothy, they were accused only of being street kids; the police never explained why they were incarcerated. The children were held in lockups together with adults, some of whom physically abused them. During the day, they were made to clean latrines at the prison and cut the grass around municipal buildings in town. Never charged with a crime, they were released two days later.26

Street boys are also enlisted to assist the police with gathering information and participating in police operations. Sixteen-year-old Russell, from Kasai Orientale, told us that in early September 2005, two street children were stealing food from a warehouse in the night. Police suspected the street children in the area and questioned many of them about the incident. Russell said he was recruited to hang about the warehouse and alert the police the next time the boys attempted to rob the warehouse. In exchange for his cooperation, he was promised 1,000 Congolese francs (U.S.$2) but never received the money. According to Russell, “There is no way we can refuse this work; if we do, we can be accused and arrested.”27

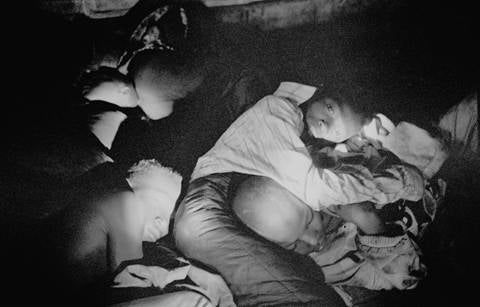

Many street children sleep

together in the evenings for warmth and safety.

© 2005 Marcus Bleasdale

Worse still is the use of street children by police and soldiers to rob and steal from civilians. In exchange for assisting in illegal activities, children can be given a piece of the loot and possible protection by individual police officers. According to staff members of a street children’s organization in Lubumbashi, several cases were brought to their attention earlier in 2005 of children from Kenya commune being used by the police to stand guard and act as lookouts when police entered stores and stole goods. They reported that these children received a share of the stolen goods or some money from the police following the robberies.28 Employees of two street children centers in Mbuji-Mayi reported similar abuse, as described to them by the kids in their centers, with street children being used by some police officers to create distractions when thefts are occurring or to help with the robberies. Staff members explained that the police seek out children to participate in theft because of their smaller size and ability to fit through narrower spaces than adults. In exchange for children’s assistance, the police reward them with money or goods, sometimes protecting them from angry civilians, or falsely accusing other street children of these thefts.29

Street children in several cities gave us the names of individual police officers or military personnel who were abusive to them. One military police officer, however, was singled out as particularly abusive. Several street boys in Goma cited Commandant Rajabu as notorious for enlisting children for criminal activities. According to one street boy, Commandant Rajabu has in the past arrested groups of street boys and detained them at Camp Katindo, a military camp in Goma of the former fifth brigade. Their prompt release was conditioned on their providing future assistance to Rajabu in stealing. One street boy knew of a case where his friend stole a mobile phone, gave it to Rajabu, and received U.S.$20 from him. He also claimed that Rajabu will assist street boys who work for him with their release from police lockups should they be apprehended during a criminal operation.30 Similarly, another street boy spoke of a roundup of street children in the area around Cap-Sud by Rajabu in August 2005. The older boys were allegedly held for some two weeks and pressured to furnish Rajabu in the future with stolen goods. 31 Several other children spoke of Rajabu as particularly brutal with street children, beating and stealing from them in an effort to intimidate and convince them to work for him.32 Employees working in street children centers in Goma reported that children in their centers had described Rajabu to them in the same way.33

When questioned about Rajabu, officers from the special police unit for the protection of children in Goma said that street children often complain about abuse by military police, including Rajabu. They said Rajabu was known for his cruelty to children, and it was possible he recruited children to steal for him, but they had not done an official investigation into the accusations. According to one officer, Rajabu is from Idjwi Island and is attached to the military intelligence office of Bureau II.34 He was arrested in September 2005 for crimes unrelated to street children.35 In an interview with the military prosecutor in Goma, a Human Rights Watch researcher was informed that Rajabu is not a military officer, but an intelligence agent from the T2 battalion that is attached to the 8th military region. As of December 2005, the military prosecutor was still collecting evidence against Rajabu, who had been dismissed from service and was under home surveillance.36

Arbitrary arrests and roundups

Police forces roundup and detain groups of street children when crimes are committed in areas where they are known to assemble. Such roundups are likely to occur when the victims of the crime are connected to those in power or when considerable amounts of money or goods are taken. In other instances, officials in the Ministry of Interior or urban security councils order general roundups of street children to clear neighborhoods of their presence. When rounded up in these circumstances, children are not charged with crimes; roundups are done under a colonial-era law that makes it an offense for children to be vagrant or to beg.37 According to the law, children must appear before a judge who will attempt to reunify them with their families or place them in private or government institutions.

On Friday, November 4, 2005, the police rounded up some 430 adults and children in Kinshasa who were congregating around the city’s main market––reportedly the police had been ordered to arrest all vagrants in the area because of growing crime there. Over 180 were boys and girls; the youngest child was nine years old. The children were held for six days, reportedly given only one meal in the entire time they were detained, and held in deplorable conditions among adult detainees. Congolese law requires that a person appear before a judge within forty-eight hours of arrest, but the children were never charged with a crime nor presented before a judge. Instead, the following Thursday, some were released to their parents or guardians, the remainder to private centers for street children.38 Child protection agencies protested the children’s prolonged detainment and unsanitary conditions and were instrumental in securing their release. One child protection officer told us that the governor of Kinshasa and officials from the Ministry of Interior had ordered the arrests, which were later condemned by the ministers of justice and social affairs.39

In another incident, eighty-five children and adults were rounded up during the last two days of September 2005 in Goma. In interviews, police officers reported to us that the provincial security council, which includes the governor and the mayor, met on September 23 and ordered the roundup after they received reports of violence and rape committed by street persons. On September 29, sixty-nine adults and children were arrested and crammed into one cell. They were released the following day, some children to their parents or guardians, others to centers run by Congolese NGOs. On September 30, another sixteen children were detained and some held overnight. During a visit to the lockup on September 30, a Human Rights Watch researcher together with other human rights activists were able to secure the release of the smaller children; the youngest appeared no older than six. On both days, no child was charged with a crime or brought before a judge. Police officers told us in interviews that the operation was necessary to stop the growing number of street children who were committing crimes and to avoid a general street child problem like the one found in Kinshasa. The assistant mayor of Goma further told us that the operation sent an important message both to parents to take better care of their children and to organizations that protect children that they should do their work correctly.40

Most street children who are detained are simply released back to the street after several days. Even in those few cases where children are presented to a judge, there is often neither an identifiable family member who can take responsibility for the child nor a state institution suitable for child placement. Instead the judge will simply release the child back to the streets. The president of a Tribunal of Peace41 explained his frustration: “If we arrive at the decision that there is no responsible family member who can take the child, we have no other real option. We can’t put them in prison; this is not suitable for a child and there is nowhere else for him or her to go. So in reality, children under sixteen just go back to the streets.”42

Twelve-year-old James lives in a village some ten kilometers outside of Mbuji-Mayi where inhabitants are predominantly engaged in diamond mining. He spends his days at gem counters running errands and looking for odd jobs. He told us that he had been arrested just the week before:

A street boy was arrested, and later told the police that I was among the boys who had stolen a shoe bag from the room of a diamond miner. Ten boys were all arrested the same day. We were beaten with bamboo on our feet and backsides. Others were beaten on their feet with pieces of rubber known as ‘boyo.’ The police did this during the interrogation but none of us knew about the theft. We were eventually released.43

Another boy, John, left his home after abuse by his aunt became intolerable. He has lived on the streets of Lubumbashi for over a year. He described the unsanitary conditions in the lockups. “I was accused of stealing with a group of street boys last month,” he told us. “We were taken to the lockup at the police station and held for three days. We weren’t given anything to eat, but some of the prisoners shared their food with us. During the interrogation, policemen whipped us with their belts. The conditions in the cachots [lockups] were terrible. Someone could have died in the lockup and you wouldn’t even have known it, the smell was that bad.” John described the lockup as a small room with only one window secured by a metal grill. While he was in custody, there were fifteen people in the room, boys and men mixed together.44 According to John, he was never charged with a crime nor brought before a judge. After his three days in confinement, he was released back to the streets.

With no home or parental care,

street children sleep together for warmth and protection.

© 2005 Marcus Bleasdale

In Kinshasa and other urban areas, roundups of large numbers of street children occur nearly every year. Individuals who work and advocate for street children have met with police and government officials to try to stop the roundups and instead focus on reintegration and rehabilitation. They told us their efforts had had some success in limiting the number and duration of roundups in the past year.45 Nonetheless, as described above, in September and November 2005 authorities ordered the roundups of large numbers of children in Goma and Kinshasa.

Special Protection Unit of the police

In Goma and a few other towns in eastern DRC, a special unit for the protection of children (Police Speciale pour le Protection des Enfants, PSPE) has been established to handle children in trouble with the law. Nongovernmental organizations, government officials, and ordinary Congolese commended the work of the PSPE and have found better treatment of children handled by that unit than by ordinary police or military. Two officers from the PSPE told Human Rights Watch that they had received specialized training in cases involving children and only detained children as a last resort (and in those cases, kept them separate from adults). They said that street children reported abuse by other police officers to them, but felt that through training and the expansion of children’s units in other towns, violence could be curtailed.46

Government and judicial officials in other cities spoke of the need to create special police units for children both to ensure that cases are brought more quickly to their attention and also so that children could receive better treatment and protection from the police. One magistrate in Lubumbashi told us that accusations of prolonged or illegal detention and police abuse were not limited to children, but were reported more generally among the entire population. For him, poor remuneration of police, salaries paid late, and little incentive to prevent crimes, helped account for some of the problems.47 Another official in the Division of Justice in Kinshasa stressed the need for more training for police to instruct them on other methods of interrogation beyond physical abuse.48 The state prosecutor in Lubumbashi suggested that police abuse of children is rare and that street children could not always be trusted to tell the truth.49 Nonetheless, he stated, as did other justice officials we interviewed, that the establishment of special police units for children could provide additional protection for children.

When questioned about roundups and police abuse of street children, police commanders responded that they were following instructions from government officials and they were merely doing their jobs. When asked about the roundup in Goma in September 2005, the police commander responded that children were not arrested nor allowed to be held overnight in jail. Rather, the intention was for their transfer to the PSPE for processing and family placement.50 In Mbuji-Mayi, a police commander denied that police officers beat or misuse street children but instead protect children from abusive adults, as was the case following the events of September 2004 (see section below, “Street Children Used for Political Purposes”).51

Child Labor

For many street children, their ability to survive depends on their finding work to earn enough for food. Street children transport goods, sell food, work in restaurants and homes, load and unload passenger busses, and engage in other temporary work in exchange for food or money. Other street children are involved in hazardous or illegal labor, such as mining, prostitution, or selling drugs and alcohol. Some adults may take pity on these children and allow them to perform labor in exchange for a reasonable sum. But others take advantage of street children, paying them less than they would adults, because they know these children have little choice.

At a center for street children in Goma, counselors who work with children reported that children can be easily exploited, for example, accepting work that adults will not, or carrying heavy loads in exchange for smaller sums of money than adults would normally receive. They highlighted the vulnerability of street children by mentioning one case in particular where street children were entrapped by a woman selling marijuana. After she had sold some to a few boys, she later threatened to report them unless they agreed to sell it for her. They began selling marijuana in town and a few were subsequently arrested.52

The following examples from Noah, Nicholas, and Matthew are illustrative of the types of jobs that children do to survive. Twelve-year-old Noah spends his time in the Virunga market looking for work. He told us that on a typical day he gets up when the cathedral bells ring, puts away the cardboard box he sleeps on, and makes his way to the market. He said that there is often little to do but play cards with his friends and beg for money or food, but sometimes he is lucky enough to find a job transporting packages for shoppers. At other times he is paid to clean excrement from an area of the market that people use as a toilet––for this work, he might get 50 francs (U.S.$0.10).53

Street children’s survival

depends on their ability to find work. Children shine shoes for small change.

© 2005 Marcus

Bleasdale

Nicholas told us that he left his aunt’s home when abuse there became too much. He found work in a restaurant, cleaning and sweeping, fetching water, and running beer crates back and forth to the local distributor. In exchange for his labor, he was allowed to sleep on the floor of the restaurant at night and given food during the day. Nicholas stole money from the owner and left the restaurant after a few months. He was ten years old at the time.54

Street children who live in urban areas near mines engage in illegal mining, searching for diamonds and other gems, and assisting with other mine-related work. Although Congolese law prohibits the use of children in the mines, in practice, thousands of children, including street children, are engaged in mining activities. Children may be sent down small tunnels to dig for gems. Others work panning gravel and filtering out precious stones. Still other children are involved in weighing, selling, and other activities around gem buying counters.

Several street children we interviewed engaged in mining activities. Two boys living in Mbuji-Mayi told us they often pan through gravel brought in by diamond diggers to look for diamond chips or stones. Another boy, twelve-year-old Matthew, worked for a time with a team of adults, looking for diamonds illegally in a diamond concession in Mbuji-Mayi. Matthew’s job was to sift through the collected gravel. He told us, “This work was very tiring. My back hurt from leaning over all day panning for gems. I was afraid all the time of being spotted by guards and killed.” One day, militia members in charge of security at the mine discovered the group in the concession and began firing on them. Matthew escaped unharmed, but he lost his mining pan while fleeing for his life, and so has quit mining.55

Experiences of street children engaged in prostitution are described below, in the sections on sexual abuse.

Physical Abuse by Adults and Older Street Children

In addition to abuse by state security forces, older street boys and men physically assault younger street children. Children report beating, kicking, burning, and knifing, among other kinds of physical abuse. Threats and acts of physical violence toward younger street children appear to serve two purposes. The abuse is usually accompanied by theft whereby younger children are obliged to hand over whatever coveted meager possession or money they have. Equally important, however, is the significance of these actions in creating control and establishing a hierarchical order on the street. Groups of street children are generally self-organized by age group with a leader. Each group is part of a larger group that is controlled by a neighborhood leader. Through intimidation, threats, and physical and sexual abuse, these leaders exact loyalty and exert control over younger street children. In most instances, the police and military fail to protect younger street children from abuse by older street boys and men.

Solomon, a street boy living in Goma, explained that in his immediate group there are eleven members who are loosely organized and led by a leader or “chef.” According to him, the boys in his group work together, sharing food and resources. Their group makes up a part of a larger group that operates around the Virunga market. Solomon estimates that there are sixty or seventy street boys in this larger group, all led by one adult leader.56

One group of six street boys in Mbuji-Mayi comes together at night to share food and sleep in a group for protection. According to their leader, sixteen-year-old Deo, their group forms part of a much larger group of street kids and adults that numbers in the hundreds. Deo explained that they must follow the orders of older members of the larger group, turning over food or money on demand. He told us that earlier that day, he had worked transporting flour for women in the market and had received 400 Congolese francs (U.S.$.80) from them. But older street boys demanded he give them some money to buy drugs and they stole the entire sum. He described these street “boys” as men in their early twenties, many who have lived on the streets for years. Deo told us that some of them might even be married and have kids of their own, but still operate as leaders of the street kids, demanding money and goods from them, and beating or burning them when they try to refuse.57

Ten-year-old Gabriel spent two years on the street before agreeing to live at a street children rehabilitation center in Goma. On the streets he lived with a group of a dozen boys around his own age. They would sleep together at night for protection from civilians and police. This didn’t stop the harassment from older street persons, however: he showed Human Rights Watch researchers scars on his arms and legs where he said older street boys had melted hot plastic onto his flesh.58 Similarly, Frederic a fifteen-year- old in Lubumbashi who has been living on the streets for nearly five years, told us, “Much worse than police harassment is the abuse from older street kids. There are two men, named Hamisi and Betrand. They come here in the night when I am sleeping. They put their hands in my pockets to see if I have any money. They never ask, they just help themselves. They are much bigger than I am, so it is difficult to get away. One time, they burnt me because I refused to give them my money. They took me into an alley and melted pieces of hot plastic from plastic bags on my legs.”59

A street boy

enjoys a shower at a center for street children in Kinshasa.

© 2005 Marcus Bleasdale

Control over street children and the power, prestige, and income that comes with it appears more entrenched in Kinshasa than other cities. Normally, the abuse used by older street children and adults to gain loyalty and obedience is directed at newly arrived street boys and girls who undergo a period of hazing or what has been described as “baptism.” One fifteen-year-old street boy in Kinshasa, Edward, described his “baptism” as a period of servitude for older street boys. He was made to run errands, buy beer and cigarettes for them, and turn over his money and possessions when asked. On several occasions, he was beaten by older street boys––one time, one of his front teeth was knocked loose. He explained that police and security forces never intervene to protect young street boys.60 A former street boy named Jacob told us that when living on the street, “older street boys would sometimes bother us; they would beat us or burn us if we didn’t get them money. They would do this so you would submit to the older ones. It is the new boys who get the abuse, those who have just arrived. Leaders do this to train you to follow orders and be respectful to them.”61

A former leader of street children in Kinshasa, now in his thirties, described to us how he used to abuse younger street boys, including beating and intimidating the newly-arrived to teach them to respect him and the hierarchy of the street, and getting money from them to buy food, drugs or other items.62 (For this man’s comments on rape as a method of control, see the section “Sexual Abuse of Street Boys,” below.)

Sexual Abuse of Street Girls

Girls living on the street may trade sex for money. Many are survivors of rape and sexual assault, sometimes of multiple gang rapes, and so a street girl may also trade sexual favors with several members of her immediate group in exchange for protection from older street boys and men. A study by Mme. Bashizi Mulangala from the Division of Social Affairs in Lubumbashi found that rape and sexual abuse among street girls was ubiquitous: among the fifty street girls she interviewed, all were survivors of rape. Mme. Bashizi found that girls as young as eight were engaging in sexual relations with street boys and men in exchange for money, something to eat, or protection.63 She told Human Rights Watch that, “This doesn’t offer them complete protection. Many girls are still forcibly raped by older street youth and in some cases, forced to have sex with several at one time. The effects on their physical and mental health are overwhelming.”64

Outreach workers who inform street girls of their rights and the availability of shelters for street children described to us a similar situation among girls with whom they work. Staff from the Assocation Bumi in Lubumbashi told us that nearly every girl they approach on the street has been raped and many engage in sex work. Girls who come to their center are given medical screenings; some test positive for HIV and others are infected with other sexually transmitted diseases (STDs).65 Staff from the Amani Center concurred. One coordinator said:

All girls who come here from the street have been raped, without exception [emphasis added]. We had two cases last year of girls who arrived here and were HIV positive. It takes time, but with counseling, girls will open up and talk about the rape and violence they have endured. Girls who have prostituted themselves for some time find it difficult to adjust to studies and life at our center. Many leave and return to the streets. They are used to the money and attention.66

Even in cases of consensual sex, girls reported that they

are often not using condoms either because their partners refuse, their use

reduces the amount of money they may receive, or they cannot obtain them. This

leaves girls at high risk of contracting STDs including HIV. The study

conducted by Mme. Mulangala in Lubumbashi found that street girls having sex

with street boys or men were indicating as many as five partners a day, without

using condoms.67

A street girl warms herself by a fire in the evening. © 2005 Marcus Bleasdale

Fifteen-year-old Amelie left home at age ten when her parents died, and now lives with a group of girls in Lubumbashi, who share food, sleep in a group during the day, and engage in sex work at night. She told Human Rights Watch researchers that she may go with three or four men each night and can make from 1,000 to 2,000 Congolese francs (U.S.$2 to $4). The amount of money she receives is conditional on whether condoms are used. She tries to insist that her clients use condoms every time. She told us, “Sometimes men come and take me by force and afterwards, leave me no money. That happens often…I started this work when I was ten years old. It is not a good life. I would rather go somewhere else and study.”68

Rose started engaging in sex work at age fifteen. She told us she can make as much as 4,000 Congolese francs (U.S.$8) in one night. She reported sexual abuse by older men who take advantage of her. “These are men who come in cars, they have sex with you, and then leave you with no money. Other men they come and beat us. They steal our money, pull our hair, or take our clothes. Police and military don’t bother us in the same way. They sometimes offer us protection.”69

Marie Noniyabo, who works with an organization for the promotion of women and girls in Mbuji-Mayi, attempts to reconcile street girls with their family members. She told us that street girls having consensual relations with other street boys and men can be the most difficult to reintegrate with their families. She said that many are taken as “wives” by street boys or men on a semi-permanent basis and may even have their children, complicating a return to family life away from the streets.70 Numerous older street boys we interviewed spoke of their “wives” as girls they slept with occasionally, often in exchange for money. Christopher, who lives on the streets in Kinshasa, said his “wife” also sells her services to other boys and does not “belong” to him permanently. Fifteen-year-old Edward said that although he calls his girl his “wife,” they are not living together and that he sleeps with her only occasionally. Both boys told us they don’t use condoms when having sex with their “wives.”71

Sexual Abuse of Street Boys

Like street girls, street boys are at risk of sexual abuse and many are survivors of rape by older street boys and men. Young street boys and those who have recently arrived on the streets are particularly vulnerable to sexual assault. Some cases of rape of street boys are linked to their hazing period or “baptism” as described above. Many boys are reluctant to speak of sexual violence, a reluctance exacerbated by additional stigma and shame as homosexual relations are considered taboo in the DRC as in many parts of Africa. Nonetheless, a few street boys we spoke with were open about the sexual violence they had endured on the streets. Of those, not one boy had officially reported the rape or sought medical help, in part, they explained, because they were too embarrassed to report these acts, or felt that the police would do nothing, or worse, would laugh at them.

Eleven-year-old Jim left home after his mother died when he was nine years old. He lived on the streets of Mbuji-Mayi for nearly two years, together with a group of six boys around his age. He spent his time collecting flour that fell from a grinding mill to make fufu (cassava meal) to eat or sell, looking for work, and playing with his friends. At night, they would take their cardboard boxes and sleep in churches and abandoned buildings. Jim told us that older boys would come and anally rape him, taking him as their “wife.”

This happened to me many times. Sometimes we would get promises of food or money if we agreed to do this, but I never got anything. Other times, I would submit to anal sex in exchange for protection or to share sleeping spaces. It was different men or boys at different times, not always the same man. They would never use condoms. When they did this to me, it could hurt a lot and cause me pain. I often took drugs, so I wouldn’t think too much about it.72

Zachary left home when he was ten years old and spent two years on the streets of Kinshasa, begging and hanging about the Victory roundabout. He told us that at night he would sleep in different places because he feared the older street boys. According to Zachary, these boys would beat them and anally rape him and his friends when they weren’t able to run away. He said that the majority of young street boys are survivors of rape and he witnessed many rapes of street boys, some happening to a friend in his presence. Zachary said that the police were not able to protect them from such abuse because it often happened in dark alleys or abandoned buildings. After two years on the street, he moved into a shelter for street children but left soon afterwards because of sexual abuse by older boys in the dormitories.73

Counselors who work in centers for former street children told us that they are aware that rape and sexual assault of boys takes place on the street because some boys will discuss the violence with them, and because others continue to sexually abuse younger boys in the shelters where they sleep at night. Staff at a shelter in Goma, and a priest working at a center in Lubumbashi, told us that they occasionally have cases where young boys complain of sexual abuse by older boys in the dormitories.74 A teacher at a center for street boys in Mbuji-Mayi told us that only one in ten boys may talk about sexual abuse on the street, but he believes it to be a widespread problem due to instances in their shelter where, the following day, boys have complained about older boys forcing them to have sex in the evenings.75 In these cases, counselors separate the boys and talk with them to discourage the abuse.

A former leader of street boys in Kinshasa explained that heterosexual relations between street boys and girls and homosexual relations between street boys are very common. He described sex between street boys and placed their sexual relations in three categories. For him, there are boys who engage in consensual sexual acts with each other. Then, there are boys who engage in sex work––those who exchange sex for money, food, or a place to sleep. He said that the most common form is anal rape of younger street boys by older ones as part of their hazing or “baptism.” He told us, “Those younger ones, they are victims of sexual abuse. I had sex with many of them in the streets. You would go to them at night where they are sleeping, grab them around their neck, pull down their pants and rape them. They would try to struggle but the young ones can’t get away. Plus, many have been taking drugs and are in deep sleep. I don’t do this anymore, but it is done regularly to the boys by older street youth. It is part of the system of “baptism”––to establish control.”76

Street Children Used for Political Purposes

The tens of thousands of children living on the streets are easy targets for manipulation by adults. As described above, for small sums of money or food, children engage in legal and illegal activities, and in many cases are exploited by men and women. Their vulnerable status makes them equally easy fodder for political opportunists who have, in the past, recruited street children to march in demonstrations, intimidate political leaders, and help create public disorder and unrest. In addition, because street children are self-organized in groups and in an established hierarchy, it can be easy to attract a few leaders of street children who can efficiently organize hundreds of children in a short period of time. In some instances, street children, often with nothing to do, are naturally drawn to crowds and demonstrations and may willingly participate. But in many cases street children have been intentionally recruited to swell the ranks of participants in public demonstrations, to the detriment of their health and safety. In the last several years in the DRC, dozens of children have been killed and many more wounded while participating in political rallies, during clashes with police and with those holding opposing political views.

In May and June 2005, government troops and police killed scores of civilians who were protesting the delay of national elections.77 Among those killed and wounded were street children who had been recruited to participate in the protests. According to MONUC investigators from the child protection section, seven children in Mbuji-Mayi, Tshikapa, and Goma were killed during political activities in those two months; another later died while in detention for his participation. In addition, nineteen children were wounded and scores of street children were arrested and illegally detained following the events. 78 Some of the worst unrest took place in Mbuji-Mayi, an area known for its support to one opposition party, the Union for Democracy and Social Progress (Union Pour la Démocratie et le Progrès Social, UPDS). Street children were approached in Mbuji-Mayi by UPDS leaders and recruited, with promises of gifts and future benefits, to march in protest against the extension of the transitional government. In other urban areas, party organizers from different political parties tempted street children with money or other gifts in exchange for their participation in political events.79

In comparison with other cities, the vast majority of street children in Lubumbashi and Kinshasa did not participate in planned political rallies around June 30 in part because government authorities had specifically warned them not to get involved. In Lubumbashi, one street boy who spends his time near the post office in the center of town told us that he was approached by UPDS supporters but he refused to work for them. He told us that he had been warned not to protest.80 An employee in the Division of Social Affairs told us that not only the UPDS but also the party of President Joseph Kabila, the People’s Party for Reconstruction and Democracy, (Parti du Peuple pour la Reconstruction et la Démocratie, PPRD) had approached street children to participate in their events they were staging, but that the children had heeded officials warnings and avoided the rallies.81 Similarly in Kinshasa, street children were told not to demonstrate to protest the extension of the transitional government. Several leaders of street children we interviewed told us that in the days before June 30 they were approached by representatives of the mayor’s and governor’s offices and asked to keep “their” kids out of political events. They instructed their networks not to become involved, an order they told us their kids obeyed.82 Instead, many children took shelter in street children centers on June 30 to avoid potential unrest.83

Staff at street children’s centers in Mbuji-Mayi reported that the police and military had prohibited demonstrations, but that some street children were still recruited and involved in the unrest. They reported several clashes between police and demonstrators in May and June 2005. Following the events, they received street children who were wounded and in need of medical care: some children had been beaten with batons or crushed by crowds attempting to flee, others were wounded when police opened fire on demonstrators to diffuse the crowds.84 More than thirty children were arrested during the disturbances––some who had participated in the events, others who were caught up in sweeps.85 One fifteen-year-old girl arrested in late June told Human Rights Watch researchers that she and her three friends were outside the market chatting when police from the special intervention force (Police d’intervention Rapide, PIR) arrived and arrested them. Held for several days in the lockup, she was later released after a friend came to the jail and paid 1,000 Congolese francs (U.S.$2) to the police.86

The use of street children in Mbuji-Mayi in events concerning the extension of the transitional government, and their getting caught up in the ensuing violence, was minor compared to events of September 2004. On September 25, 2004, street children were the target of a mass killing campaign led by diamond miners and orchestrated with the help of other civilians. During the slaughter, attackers killed at least twenty street children, some as young as ten years old, burning street children alive and throwing their bodies into the river.87 Scores of street children were wounded in the attacks, and many were afraid to seek medical attention for fear of further mistreatment. Centers for street children were also targeted and looted by angry mobs, causing children who had taken shelter there to flee once again. In the days that followed, the center of Mbuji-Mayi was described as a ghost town, devoid of the estimated 5,000 street children who had gone into hiding to avoid the killings. 88

Numerous sources indicate that the massacre in Mbuji-Mayi and the popular uprising against the street children had its roots in past events and the political manipulation of street children.89 According to one human rights activist, street kids had been organized for some time into two groups: one supporting the former governor and the PPRD, and the other supporting the opposition, UPDS. In May 2003, during a political march in support of the president, street children for and against the march began assembling, security services were brought in, and in dispersing the crowds they killed several street children. Leaders of both groups of street children were reportedly given money, food or material goods to distribute to their respective groups in exchange for their participation.90

Following the May 2003 events, a group of street children, allegedly supported by the former governor and the PPRD to counter local UPDS support, became more powerful and began operating more systematically at the market of Bakwa Dianga, collecting money from civilians who were doing business there. This group was led by a former street child, Hubert Kanda, who told Human Rights Watch researchers in an interview, that he had been the “president” and protector of street children at this market.91 According to government and military officials, the activities of this group of street children and adults throughout 2004 became intolerable: they demanded “taxes” from the population to work and operate in the market, and physically abused men and women. They told us that at the same time the police would not, or could not, control these children and adults who were terrorizing the population, and were referred to as the “red army” (l’armée rouge).92 Emboldened street children identified with this same group began attacking women and girls on their way to the river to gather water, or those coming from the water after bathing. In order to pass, the women were reportedly forced to undress in front of groups of street boys, and in some cases, older boys and men gang raped them. 93

The situation came to a head following an incident on September 19, 2004, when older street youth attacked diamond miners from Binza quarter in Dibindi commune, and stole their sacks of gravel allegedly containing several large stones of value.94 The following day the miners came to town, reported the incident to police, and fighting between the miners and some street youths ensued, police being brought in to calm the situation. Several street children were injured as well as one policeman and one miner. On September 21, the diamond miners approached the Bakwa Dianga market and issued a warning to the street children and government authorities: clear the streets of Mbuji-Mayi of street children or they would take matters into their own hands.95

According to military reports,96 on September 23, with no visible movement on the part of the authorities to diffuse the situation, a group of diamond miners, reportedly led by Mukishi aka Chimbole, broadcast a message on a local radio station.97 They gave the authorities forty-eight hours to react and heed their warning, or the miners would seek out the street children and “finish them.” This message was repeated on several radio and television stations, that night and the following day.98 The miners reportedly called on all people who had problems with the street children to come together and take action. They told listeners to consider the street children as enemies of the state and to deal with them as decisively as the Tutsis had been hunted in Rwanda.99 On Saturday September 25, hundreds of diamond miners armed with sticks, batons, rocks, machetes, and gasoline entered town and attacked the street children. An even larger number of other civilians joined in, helping to identify the street children and indicate to the miners where they were hiding. At least twenty and possibly many more children were killed: some had tires thrown around their bodies, gasoline poured on them, and they were burnt alive, their charred corpses then thrown into a nearby river. Scores of other street children were wounded in the attacks and thousands fled the center of town and went into hiding.100 According to survivors, no distinction was made between older street youths responsible for past abuses of civilians and the general population of street children. Some street boys as young as ten years old were slaughtered. Witnesses also reported that initially the police and military played no role in stopping the killings, and that only later did they break up the crowds and protect children, locking some in jail for their own protection.101 The leader of the street children of the Bakwa Dianga market, Hubert Kanda, went into hiding following the events and was later taken into police custody, reportedly for his own protection.

Three children we spoke with described their experiences that day. Ten-year-old Daniel was at Bakwa Dianga market the day of the attack, washing clothes for a vendor. He told us that crowds of civilians came into the market swinging clubs and batons and shouting out to attack the children. Daniel was beaten on his back and both his arms were broken. He was left for dead with other bodies, only to be later discovered by the police and brought to a hospital. Daniel bears the scars from the beatings and both his arms are deformed from the injuries he sustained.102 George sells charcoal in town to make money for food. At the time of the September 2004 events, he was ten years old and working at the market, selling charcoal with a friend. He said, “All of a sudden, we saw a group coming at us with machetes, knives and batons. The mamas of the market cried out, ‘They are here, there is one, right there.’ My friend was stabbed with a knife and I was later told that he died. Myself, I was able to flee and was saved by a businessman who took pity and hid me from the attackers.”103 On the day of the attack, Rachel was with her friend on the way to the market. Surprised by a crowd carrying rocks and sticks, her friend was identified as a street kid, undressed and badly beaten. Rachel was able to flee to safety.104

Street children gather pieces of charcoal that

have fallen at distribution sites to later re-sell and earn money to eat.

© 2005 Marcus

Bleasdale

In the weeks and months following the events, government bodies, U.N. agencies, and Congolese NGOs investigated the events and published reports of their findings. The government arrested and prosecuted five diamond miners who had participated in the massacre. In April 2005 they were each sentenced to five years in prison.105 On appeal, two of the accused were acquitted and the others were given reduced sentences. Dissatisfied with the outcome of the appeal, the public prosecutor told us in September 2005 that he has appealed the case to the Supreme Court in Kinshasa. He said that the convicted men were not the ringleaders, but had been identified through a film taken by a local news channel. When questioned by Human Rights Watch on why the leaders of the miners, including Mukishi, were not tried, he responded that a file was opened on them, but their whereabouts were unknown. When asked about the role of the media in inciting the population, he replied that their actions were still under investigation.106 When we asked the prosecutor about the detention of the street kid leader, Kanda, he told us that he was unaware under whose orders he was being detained and knew of no charges against him.107 The commandant Major Israel at police headquarters told Human Rights Watch that the decision to protect Kanda had been taken by the provincial committee of security and that questions about his detention should be directed to the Minister of Interior in Kinshasa.108 When we interviewed Kanda in September 2005 he told us that he had been held at the communal lockup without charge since 2004 and was waiting for transfer to another city.109

Since the events of September 2004, government officials, the police and NGOs have met regularly in Mbuji-Mayi to address issues around street children and try to avoid future killings. We interviewed a group of them, amongst whom several recognized that more needs to be done to prevent children from ending up on the streets. A nurse who works with street children summed up the killings of September:

What people have failed to identify and address is that the pitiful state of workers, and particularly diamond miners, is one reason there are so many street children in Mbuji-Mayi. They are largely uneducated men. They drink and take drugs. They don’t receive a steady income, many have several “wives” and numerous children they can’t, or won’t, care for. They are often away for weeks at a time, leaving the burden of the family on their wives who can be victims of physical abuse. The deplorable family life is what drives many of these children to the streets. These street children did not drop from the sky, they are our children. In some ways the killing of the street kids by the miners is comparable to parents killing their own children. The events leading up to and including the slaughter was just one desperate group preying on the other.110

[8] Human Rights Watch interviews, Goma, September 13-15, 2005, Lubumbashi, September 16-18, and Mbuji-Mayi, September 21-22, 2005.

[9] Human Rights Watch interview with Solomon, Virunga market, Goma, September 13, 2005. All names used in this report have been changed to protect the identity of street children.

[10] Human Rights Watch interview with Emmanuel, street children center, Goma, September 14, 2005.

[11] Human Rights Watch interview with Raphael, Goma, September 13, 2005.

[12] Human Rights Watch interview, street children center, Goma, September 13, 2005.

[13] Human Rights Watch interview with Robert, twenty-three, Lubumbashi, September 17, 2005.

[14] Human Rights Watch interview with Noah, Goma, September 13, 2005.

[15] Human Rights Watch interview with Benjamin, seventeen, street children rehabilitation center, Goma, September 14, 2005.

[16] Human Rights Watch interview with Emmanuel, fourteen, Goma, September 14, 2005.

[17] Human Rights Watch interview with Peter, fifteen, Lubumbashi, September 16, 2005.

[18] Human Rights Watch interview with Frederic, Lubumbashi, September 18, 2005.

[19] Human Rights Watch interview with Rebecca, Goma, September 14, 2005.

[20] Human Rights Watch interview, street girl center, Lubumbashi, September 17, 2005.

[21] Human Rights Watch interview with Margaret, street girl center, Mbuji-Mayi, September 23, 2005.

[22] Human Rights Watch interview with Mme. Kabera Mujijima Bora, Lubumbashi, September 16, 2005.

[23] Bashizi Mulangala, “Les Résultats de l’Enquete sur les Abus et Violence Sexuelles à Lubumbashi,” March 2003, p. 4. See also Mulangala, “L’Exploitation Sexuelle des Enfants et des Femmes à Lubumbashi, Mythe ou Réalité?” 2004, p. 3.

[24] Human Rights Watch, The War Within the War, Sexual Violence Against Women and Girls in Eastern Congo (New York: Human Rights Watch, 2002), pp. 52–63, [online] http://www.hrw.org/reports/2002/drc.

[25] Human Rights Watch interview with Deo, sixteen, Star roundabout, Mbuji-Mayi, September 25, 2005.

[26] Human Rights Watch interview with Timothy, fifteen, street children center, Kinshasa, October 1, 2005.

[27] Human Rights Watch interview with Russell, Mbuji-Mayi, September 25, 2005.

[28] Human Rights Watch interview with staff at a street children center, Lubumbashi, September 16, 2005.

[29] Human Rights Watch interviews with staff at two street children centers, Mbuji-Mayi, September 21-22, 2005.

[30] Human Rights Watch interview, Goma, September 14, 2005.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Human Rights Watch interviews, Goma, September 14-15, 2005.

[33] Human Rights Watch interviews with staff at street children centers, Goma, September 13-14, 2005.

[34] Bureau II refers to an intelligence office attached to a military battalion.

[35] Human Rights Watch interview with PSPE officers Justine Safi and John Matata, Goma, September 14, 2005.

[36] Human Rights Watch interview with Maj. Bwa Mulundu Guzola Jean Blaise, Auditeur de Garrison, et Auditeur Superieur ad interim, Goma, December 8, 2005.

[37] Décret du 6 décembre 1950 relatif à l’enfance délinquante, complété par l’ordonnance loi no. 78/016 du 4 juillet 1978, art. 1er. In most cases, street children are not arrested and charged with the offense of vagrancy. Rather, the existence of this law provides a pretext for authorities to arrest and detain street children during roundups.

[38] UN Integrated Regional Information Network (IRIN), “DRC: Police Still Holding 432 ‘Vagrants’ in Poor Conditions,“ November 10, 2005 [online], http://allafrica.com (November 11, 2005).

[39] Ibid., Human Rights Watch telephone interview with MONUC officer, Kinshasa, November 14, 2005.

[40] Human Rights Watch interviews in Goma with: Principal Commissioner of the police, Jacques Chiragada-Ntwali, 30 September 2005; Assistant Mayor of Goma, October 10, 2005; and, Police Major Oscar Tavawuka, November 10, 2005.

[41] The Tribunals of Peace in the DRC handle cases where the penalty for the crime is five years or less.

[42] Human Rights Watch interview with M. Jean Pierre Cakwangasha Kabwenga, president of the Tribunal of Peace, Lubumbashi, September 19, 2005.

[43] Human Rights Watch interview with James, Chimuna village, September 24, 2005.

[44] Human Rights Watch interview with John, fourteen, Lubumbashi, September 16, 2005.

[45] Human Rights Watch interview with Remy Mafu Sasa, Kinshasa, September 28, 2005.

[46] Human Rights Watch interview with PSPE officers Justine Safi and John Matata, Goma, September 14, 2005.

[47] Human Rights Watch interview with a magistrate at the Tribunal of Peace, Lubumbashi, September 19, 2005.

[48] Human Rights Watch interview with an official in the division of justice, Kinshasa, September 30, 2005.

[49] Human Rights Watch interview with the state prosecutor, Lubumbashi, September 17, 2005.

[50] Human Rights Watch interview with Maj. Oscar Tavawuka, Goma, November 10, 2005.

[51] Human Rights Watch interview with Commandant Major Israel, Mbuji-Mayi, September 27, 2005.

[52] Human Rights Watch interview with staff at a street children center, Goma, September 13, 2005.

[53] Human Rights Watch interview with Noah, Goma, September 13, 2005.

[54] Human Rights Watch interview with Nicholas, eleven, Lubumbashi, September 17, 2005.

[55] Human Rights Watch interview with Matthew, Chimuna village, September 24, 2005.

[56] Human Rights Watch interview with Solomon, seventeen, Goma, September 14, 2005.

[57] Human Rights Watch interview with Deo, Mbuji-Mayi, September 25, 2005.

[58] Human Rights Watch interview with Gabriel, Goma, September 14, 2005.

[59] Human Rights Watch interview with Frederic, Lubumbashi, September 18, 2005.

[60] Human Rights Watch interview with Edward, Kinshasa, October 1, 2005.

[61] Human Rights Watch interview with Jacob, sixteen, Kinshasa, October 1, 2005.

[62] Human Rights Watch interview with a former street child leader, Kinshasa, October 1, 2005.

[63] Mme. Bashizi Mulangala, “Les Résultats de l’Enquete sur les Abus et Violence Sexuelles à Lubumbashi,” p. 4 ; Mulangala, “L’Exploitation Sexuelle des Enfants et des Femmes à Lubumbashi, Mythe ou Réalité?” p. 3 ; and Human Rights Watch interview with Mme. Bashizi Mulangala, Lubumbashi, September 16, 2005.

[64] Human Rights Watch interview with Mme. Bashizi Mulangala, Lubumbashi, September 16, 2005.

[65] Ibid.

[66] Human Rights Watch interview with a counselor at the Center Amani, Lubumbashi, September 17, 2005.

[67] Mulangala, “Les Résultats de l’Enquete sur les Abus et Violence Sexuelles à Lubumbashi,” p. 4 ; Mulangala, “L’Exploitation Sexuelle des Enfants et des Femmes à Lubumbashi, Mythe ou Réalité?” p. 3.

[68] Human Rights Watch interview with Amelie, Lubumbashi, September 18, 2005.

[69] Human Rights Watch interview with Rose, twenty, Lubumbashi, September 18, 2005.

[70] Human Rights Watch interview with Marie Noniyabo of the Conscientisation et Promotion de la Femme et Enfants (COPROFE), Mbuji-Mayi, September 22, 2005.

[71] Human Rights Watch interviews with Christopher and Edward, Kinshasa, October 1, 2005.

[72] Human Rights Watch interview with Jim, eleven, Mbuji-Mayi, September 23, 2005.

[73] Human Rights Watch interview with Zachary, twelve, Kinshasa, October 1, 2005.

[74] Human Rights Watch interviews with staff of the Concert d’Actions pour Jeunes et Enfants Defavorisés (CAJED), Goma, September 13, 2005, and with Father Serge Mwaka, Lubumbashi, September 16, 2005.

[75] Human Rights Watch interview with a teacher at the International Children’s Rights Organisation (BICE), Mbuji-Mayi, September 23, 2005.

[76] Human Rights Watch interview with former street child, Kinshasa, October 1, 2005.

[77] Human Rights Watch, “Democratic Republic of Congo - Elections in Sight: ‘Don’t Rock the Boat’?” A Human Rights Watch Briefing Paper, December 15, 2005, [online] http://www.hrw.org, p. 11.

[78] MONUC Child Protection Section, “Incidents and Risks of Children’s Rights Violations During the Electoral Process,” 2005.

[79] Ibid., Human Rights Watch interview, MONUC Human Rights and Children Protection Staff, Mbuji-Mayi, September 22, 2005. See also, MONUC Human Rights Section, “Report on the Events in Mbuji-Mayi, Province of Kasai Oriental,” July 2005.

[80] Human Rights Watch interview with William, fifteen, Lubumbashi, September 17, 2005.

[81] Human Rights Watch interview with a staff member of the Division of Social Affairs, Lubumbashi, September 16, 2005.

[82] Human Rights Watch interview with staff of the Association des Jeunes de la Rue pour le Dévelopment (AJRD), Kinshasa, September 30, 2005.

[83] MONUC report, “Incidents and Risks,” p. 6.

[84] Human Rights Watch interview with staff at street children’s centers, Mbuji-Mayi, September 21-23, 2005.

[85] MONUC report, “Incidents and Risks,” p. 4.

[86] Human Rights Watch interview with Nancy, Mbuji-Mayi, September 23, 2005.

[87] “Mbuji-Mayi: The ‘Diggers’ Impose the Law of the Jungle,” Centre d’Etudes et Formation Populaires (CEFOP) press release, September 27, 2004.

[88] Human Rights Watch interviews, Mbuji-Mayi, September 21-24, 2005.

[89] For a more detailed analysis of the events of September 2004, see: “Rapport de la Commission d’Enquete Sénatoriale sur les Evénements Survenus a Mbuji-Mayi du 20 au 25 Septembre 2004, Enquete Effectuée du 03 au 08 Octobre 2004,” Parliamentarian Report of the Senate of the Democratic Republic of Congo, October 2004; “Rapport: Attaques Perpétrées sur les Enfants et Jeunes de la Rue à Mbuji Mayi du 20 au 25 Septembre 2004,” MONUC, April 2005; “Rapport des Evénements Sanglants qui ont Oppose les Creuseurs aux Enfants du Marche du 17 au 25/09/2004,” Œuvres Sociales Betu Bana, November 2004; and, “Rapport Sur les Massacres des Enfants de la Rue a MbujiMayi du 18 au 27 Septembre 2004,” Training Center for People and Human Rights (TCPHR), September 27, 2004.

[90] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Charles Mfwamba Mukendi, Mbuji-Mayi, September 30, 2004. See also “MbujiMayi: Des Shegues en Danger d’Extermination par des Elements des Services Speciaux de la Police,” Centre d’Etudes et Formation Populaires (CEFOP) press release, May 2003.

[91] Human Rights Watch interview with Hubert Kanda, Mbuji-Mayi, September 24, 2005.

[92] Human Rights Watch interviews with the president of the Tribunal of Peace, Mbuji-Mayi, September 26, 2005 and with Maj. Mukonko Lemba, Mbuji-Mayi, September 26, 2005.

[93] Human Rights Watch interviews, Mbuji-Mayi, September 24 and 26, 2005.

[94] Human Rights Watch interview with Maj. Mukonko Lemba, Mbuji-Mayi, September 26, 2005.

[95] Human Rights Watch interview, Mbuji-Mayi, September 24, 2006. See also Œuvres Sociales Betu Bana, “Rapport des Evénements Sanglants. ”

[96] Human Rights Watch interview with Maj. Mukonko Lemba, Mbuji-Mayi, September 26, 2005.

[97] Human Rights Watch interviews, Mbuji-Mayi, September, 22-26, 2005. See also MONUC “Rapport: Attaques Perpetrées,” p. 17.

[98] MONUC “Rapport: Attaques Perpétrées,” p. 25; Senate Report “Rapport de la Commission,” p. 16.

[99] Human Rights Watch interview with Maj. Mukonko Lemba, Mbuji-Mayi, September 26, 2005.

[100] Human Rights Watch interview, September 25-27, 2005.

[101] Ibid.

[102] Human Rights Watch interview with Daniel, Mbuji-Mayi, September 23, 2005.

[103] Human Rights Watch interview with George, eleven, Mbuji-Mayi, September 24, 2005.

[104] Human Rights Watch interview with Rachel, fifteen, Mbuji-Mayi, September 23, 2005.

[105] “Sentences of Only 5-Years for Killing Street Children,” Missionary Service News Agency (MISNA), April 15, 2005.

[106] Human Rights Watch interview with the Procureur de la République, Mbuji-Mayi, September 24, 2005.

[107] Ibid.

[108] Human Rights Watch interview with Commandant Major Israel, Mbuji-Mayi, September 27, 2005.

[109] Human Rights Watch interview, police lockup at Chacaca quarter, September 24, 2005.

[110] Human Rights Watch interview with a nurse at a street children’s center, Mbuji-Mayi, September 26, 2005.

| <<previous | index | next>> | April 2006 |