<<previous | index | next>>

Syria

“The Internet is the only way for intellectuals to meet and share ideas in Syria today.”

—Aktham Na`issa, president of the Committees for the Defense of Democratic Liberties and Human Rights in Syria234

“What I want to say to you, my friend…is that you and your friends are being watched constantly. They’re watching you as you walk in the street and in your daily life. They’re watching you as you talk on your home phone, on your mobile, and on the Internet. Don’t be too surprised if they’re watching you in your sleep, in your dreams, and in your silence. Don’t be surprised if they’ve come into your bed at night.”

—E-mail from one Syrian human rights activist to another, 2005235

Many Syrians hoped that Bashar al-Asad, who succeeded his father as president in July 2000, would bring a new era of openness to Syria and to the Syrian Internet. In his inauguration speech, he spoke of the need for “creative thinking,” “the desperate need for constructive criticism,” “transparency,” and “democracy.”236 Before he became president, the only formal title he had ever held was chairman of the Syrian Computer Society (SCS). `Amr Salim, a co-founder of the SCS, told reporters in March 2005 that Bashar al-Asad “wanted us to start evangelizing the Internet at a time when it was unthinkable.”237

Syrian intellectuals, taking courage from the government’s quick release of 600 political prisoners, began to call more openly for reform. “By January 2001,” one leading reformist recalled, “It was like a fashion. Every week you heard an announcement of the opening of a new civil society forum.”238 It did not take long for this “Damascus Spring” to turn into a “Damascus Winter.” Key leaders in the nascent civil society movement were arrested in September 2001, weeks before the passage of a restrictive new Press Law. By fall 2002, continued arrests and a crackdown on the forums had all but eliminated the hopes reformers had nurtured for the new president.

Today, the Syrian government relies on a host of repressive laws and extralegal measures to suppress Syrians’ right to access and disseminate information freely online. It censors the Internet—as it does all media—with a free hand. It monitors and censors written and electronic correspondence. The government has detained people for expressing their opinions or reporting information online, and even for forwarding political jokes by email. Syrian bloggers and human rights activists told Human Rights Watch that plainclothes security officers maintain a close watch over Internet cafés.

Against the background of Syria’s monolithic state press—which former Interior Minister Ghazi Kan`an characterized as “unreadable” soon after his appointment in October 2004—and Syria’s record of threatening, detaining, and torturing people for expressing their opinions, the Internet has opened a small space for freedom of expression.239 Faced with an absence of independent news media, and with laws that criminalize any gathering of more than five people, Syrians have taken to the Internet to exchange information and express themselves, however cautiously.

Testing the Limits of Repression

Ayman `Abd al-Nur, an economist, Ba`ath Party member, and childhood friend of President al-Asad, knows something about online censorship in Syria. In a recent telephone interview, `Abd al-Nur told Human Rights Watch that he started the Web site http://www.all4syria.org in May 2003 because “I realized that Baghdad was the second step after Afghanistan. I wanted to launch a platform to promote intelligent dialogue to prevent Damascus from becoming the third.”240

The site quickly became a forum for Syrian groups, thinkers, and expatriates to exchange ideas. `Abd al-Nur’s writings have criticized officials by name, sometimes calling for their dismissal outright and listing their mistakes to justify his recommendations. In February 2004, `Abd al-Nur found his site blocked.

The day `Abd al-Nur found his site blocked, he marshaled his list of approximately 1,700 email addresses and sent them the first of his daily bulletins. `Abd al-Nur told Human Rights Watch that he knew his emails were being blocked when he started receiving complaints from people who had not received the bulletins. When `Abd al-Nur tried to log in to his email two days later, he received a message saying, “You are not permitted to enter.” `Abd al-Nur then created a new email address and sent the bulletin out from that address. The next day, that address was blocked. So he created a new one. And so it went for forty days, `Abd al-Nur said, “Until the government got tired of trying to guess what address I was going to use next. They couldn’t keep up, they couldn’t read my mind.”241

By October 2005, `Abd al-Nur said his list of subscribers had swelled to 16,000, two-thirds of them in Syria. “We cross all the red lines,” he said. “We attack the security apparatus, Military Intelligence, even officials in the Presidential Palace. There are no more taboos.”242

The Internet, he said, has “given Syrians free speech. It has expanded the range of topics people can read about. It has created a new, open atmosphere.” The aim, he said, was to “put tough questions to the government, to put it under some pressure.”243

`Abd al-Nur remains loyal to the Ba`ath Party, but he worries that the old guard is “out of date.”244 The purpose of All4Syria.org, he said, is “to promote the sense of freedom of speech, to open dialogue. It strengthens the community. When people see that they can participate in the dialogue, they will defend their society.”245

`Abd al-Nur explained to one interviewer why he had been censored but not treated more harshly:

For a simple reason: let us assume now that we have a PC and we surf the Internet. We go to those opposition sites and what do we see? “The al-Asad family is very corrupt and we have to change them or kill them. The Alawites [a minority Shi`a community that in Syria has supplied many senior military officers and politicians in the Ba`ath government, including the al-Asad family] are running Syria and we should finish them off. We need freedom of speech and to free political prisoners. The corruption in Syria must end. The Ba`ath is very bad—we should abolish it.” You go to my Web site and you see: “This is the official, this is his name, he did this, made this decision, which is wrong because of this, and because of his wrong decision he will impact this sector in this way. The president sent this delegation, and they are underqualified and should be changed and replaced with the following people,” and I list them….

If the average person reads the opposition Web sites, they think, “We will not endanger our lives with these Utopians.” There is no concrete or useable information against the officials in the opposition Web sites. “All4Syria” is actually much more scandalous because those in the government who employ these idiots will see how badly qualified they are and figure out with whom they should be replaced.246

`Abd al-Nur is sanguine about the Internet’s ability to bring about change in Syria. With the Internet, he recently told Human Rights Watch, “We will be able to create a new era of freedom and openness, to ask tougher questions of the government. The Internet helps people organize, to find others who share their ideas who didn’t have a chance to publish in the state press, to know there are others who share their ideas.”247

Others less well-connected are more circumspect. As Ayman Haykal, a 25-year-old medical student and the head of the Syrian Bloggers Association, put it, “You start writing something and then you think about it: Maybe I’ll be misunderstood. So you go backspace, backspace, backspace.”248

A recent academic survey of ninety-one bloggers in Syria, Lebanon, and Jordan found that 80 percent practiced some form of self-censorship. Nine out of twenty bloggers cited “political reasons and fear of state repression” as the reasons why they censored their own writings on politics.249

Some have found a refuge of sorts in English-language blogs. One anonymous blogger cited in the study wrote,

I think that in the Middle East, there is almost never honest talk about politics. People are afraid to say things openly. On blogs they can say almost whatever they like. I see blogs from Syria where they say all sorts of terrible (but true) things about the al-Asad family in English that they could never say in Arabic online or in person. It lets people tell the truth openly with less fear than other media forms.250

“There is now a wider margin for freedom of expression,” Ayman Haykal told one interviewer. “Most of the political blogs are in Arabic by anonymous bloggers. Some have two blogs—a cultural one in English and a political one in Arabic under a fake name. The power of blogging also lies in the possibility of being anonymous.”251

Others are using technical means to combat government censorship. “At first we used sites that offer free, anonymous browsing that overcame the firewall,” one Syrian blogger, speaking on condition of anonymity, told Human Rights Watch by email. “But soon those sites were also blocked. So we (the tech people) tried to search for an alternative. This came in the form of anonymity software like HTTPtunnel, Socks2HTTP, CCProxy, and the like.” While some of these programs require paid licenses, pirated copies are easy to find. Demand for the software is reportedly so strong that some Syrians have been able to turn installing software available on a free or trial basis into a job. They reportedly charge people up to 5000 Syrian pounds (US$100)—steep prices in the Syrian market—for installing the software. And, since “most of the time they install the trial versions, after 30 days people will have to pay…another 5000 [Syrian pounds] to ‘reactivate.’”252

Another Syrian blogger noted that the Syrian government had taken steps to combat this, but “most of the time, they were unable to keep up with the rapid improvements to the software made by its original developers.”253

Syrian Internet users said they also used other means to get around the controls the Syrian government has placed on the Internet. At many Internet cafés, customers can request to use “the Lebanese server”—that is, a connection via a long-distance phone call to a Lebanese ISP not subject to Syria’s Internet restrictions—for no extra charge. Indeed, Syrians had connected through Lebanese and Jordanian ISPs before the government officially allowed the Internet into the country.254 If caught, those connecting through ISPs in neighboring countries face fines and the possibility of their phone lines being cut, but the practice is reportedly common nonetheless.255

New communications technologies are sabotaging the Syrian government’s state information machine. “Before satellite TV and the Internet,” prominent Syrian human rights lawyer Anwar al-Bunni said recently, the government could successfully tar human rights activists as “traitors.”256

Since the introduction of these new technologies, people have alternative sources of information and so regard such campaigns with more suspicion. “On the front page of the [government-owned] newspaper, al-Thawra, they accused me of agitating for human rights while ignoring national rights. But that hasn’t made a dent in my credibility. In fact the exact opposite happened: ten articles appeared on the Internet in support of me,” al-Bunni said.

Armed with technologies that afford a degree of privacy and the strength of numbers, Syrians are finding new spaces to express themselves. Several Syrian bloggers, echoing Ayman `Abd al-Nur, spoke of the Internet’s importance in helping them find others who shared their ideas. One, writing on condition of anonymity, told Human Rights Watch:

I was first introduced to few Syrian bloggers by a friend. At first, I didn’t understand what the connection between them was, but it was obvious that they were all highly intellectual people...the kind you don’t meet every day! But at the same time they seemed so different from each other. Eventually I found out that they didn’t know each other before becoming bloggers. So I was invited to become a Syrian blogger, and I happily decided to become one. I guess I started blogging to get access to exceptional individuals, I mean to their thoughts and ideas about what’s going on here and the rest of the world—you know—things you wont hear about on national TV or local newspapers, AS THEY’RE ALL CONTR[OL]LED IN ONE WAY OR ANOT[H]ER BY THE GOVERMENT! We sure know their side of EVERY story! [emphasis in original]257

Another told Human Rights Watch that he strongly believed the Internet is opening a new space in Syrian society.

Sometimes it’s hard to talk about serious issues without being hushed…But now it’s much easier to find people with similar interests, someone who’d be glad to hear what you have to say and give you some feedback...At least people can talk now, knowing that in one way or another they’re being heard. I know that the government and the high authorities will do everything they can to stop the change. But I am sure a day will come when it will be way over their tiny empty heads!258

Given Syria’s record of imprisoning people for what they have written online, it is no surprise to hear `Amr Faham, a civil engineering student who keeps http://www.syriahiking.blogspot.com, say, “Many people are still afraid. They are worried that it’s a trick—let people talk and then get them.”259

But even those who know all too well the reasons to be afraid speak of the importance of Internet in Syrian society. For thirty years, Aktham Na`issa has written articles and spoken out against human rights abuses in Syria. The authorities have arrested him six times for publicly demanding respect for human rights. The government has held him incommunicado and tortured him. He is currently not allowed to travel abroad. His family has been threatened and harassed. “In Syria,” he told Human Rights Watch, “all meetings are outlawed. According to the Emergency Law, any meeting of more than five people is banned without prior permission. In these conditions, the Internet is the only way to communicate.” The government was doing its best to control this new means of communication, he said, “But there are so many Web sites, so many emails, they can’t keep up with us… For the intellectuals, it’s the only means of communication.”260

Lawyer Anwar al-Bunni echoed these sentiments: “The Internet has become the only means of communication. There is a lot of censorship and obfuscation in the Syrian press.”261

“I am under the usual pressures,” al-Bunni told Human Rights Watch. “Six orders have been issued to bar me from the Lawyers Syndicate.”262 The government has prevented him from traveling. Security officials regularly call him in for questioning. “They send an officer with a letter inviting us to come in for an interview,” he told Human Rights Watch. “They treat us reasonably well. They tell us the country is under attack, that they don’t want us to help with that attack. They tell us they don’t want us to end up in prison. They say, ‘you don’t know what’s waiting for you in prison.’”263

Others, faced with threats against their families, choose to leave Syria if they can. Over the course of 2005, reformist and blogger `Ammar `Abd al-Hamid was “invited” to visit Political Security interrogators three times and Military Intelligence five times because of his blog, http://amarji.blogspot.com, which featured mordant criticism of the president and Ba`ath Party rule. `Abd al-Hamid told Human Rights Watch that the interrogations focused on his writings for Beirut’s English-language Daily Star, his time as a visiting fellow at the Brookings Institution in Washington, DC, in 2004, and on the activities of the Thawra Project he founded “to provide a free platform for the discussion and dissemination of ideas that can contribute to raising standards of civic awareness in the broader Middle East and North African region.”264

“The man I speak to is very upfront in saying that he doesn’t have confidence in what I do but at the same time he respects my sense of patriotism,” `Abd al-Hamid told a journalist in early September 2005. “He basically says ‘Big Brother is watching you.’”265

He elaborated on what happened in the interrogations in an email to Human Rights Watch:

I think they really wanted to smack me, but they did not have the authority to do it. I made quite certain to tell them that my activities and views were known to the president, and they were. The president did not approve of or like my activities, I admitted, but he knows not to bother me.

So, my strategy was to push the matter upward, because I knew, or hoped, that the people above would be better at estimating the political risk involved in harassing someone in my position. The strategy worked. I got called in by [Gen.] Assef Chawkat (General Dashing in my blog) in mid-March [Chawkat is head of Military Intelligence and the husband of the president’s only sister]. He had earlier attempted to send me a message through my mom (a known actress), which I ignored.

So, we met at his office. My wife insisted on showing up with me, and this took him by surprise, but he received us both. This was the first of two meetings. Threats and attempts at bribery and cooptation were the main features throughout. The second meeting in particular was a bit sharp. He threatened me with 15-to-life in prison, he then suggested that I could become a minister or an ambassador. I scoffed at both attempts and offered to stop writing for a while, and suggested that I might even leave the country for the time being, and that was that.266

In 2005, faced with harassment and threats, `Abd al-Hamid chose to leave Syria and continue blogging. On September 8, 2005, he began what he has called his “exile” in the United States.

Access to the Internet

Until the mid-1990s, Syria banned even the import of fax machines and computer modems. In 1997, Syria established a link to the Internet for a limited number of government ministries and state-owned companies. The next year, businesses and professionals were allowed to subscribe to a service that gave them access first to email, then the Internet. Only in 2000 were Syrian citizens allowed to apply for Internet access. Syrians could also access the Internet at the arrival and transit halls of the airport in Damascus, at the Asad National Library, and at two Internet cafés in Damascus.

In a 1999 article SCS co-founder `Amr Salim sympathetically explained Syria’s “cautious” approach to the Internet:

In order for President [Hafez] al-Asad to feel comfortable promoting a particular technology, it must meet the following criteria:

1. It should benefit the majority of the Syrian people. Technology geared toward the elite is not favored because such people have the resources and means to get what they want without government assistance.

2. It should not disrupt the social structure or adversely affect the middle class, and should be within the means of the masses.

3. It should have a direct impact on Syria’s overall social and economic development.

4. It should not jeopardize Syrian independence or security concerns.267

In January 2005, Best Italia started offering Internet service in Syria via a satellite link. Such services are expensive, however, and cater to embassies. Syria has recently overhauled its public data network, or “backbone” Internet infrastructure. According to a European computer engineer who worked on the project, the new network is “better and specifically more open,” but the government would “keep tabs on things” through its control of the public data network and the international gateway that links the Syrian network to the rest of the world.268

Currently, there are three ISPs that offer service to the general public: the government-owned Syria Telecommunication Establishment (STE); the government-funded SCS Network, which until April 2005 was open only to members of Syria’s professional syndicates; and, as of September 2005, Aya, which bills itself as “the first fully private ISP in Syria” and is owned by Muhammad Hamshu, a Syrian entrepreneur known for his close ties with the president. Other private ISPs were reportedly in the process of setting up their operations or obtaining licenses to operate. While Syrian consumers will likely soon enjoy the benefits of a competitive market place for Internet service, the government apparently intends to maintain its control over data communications within the country as well as coming into and leaving the country via its control of the international gateway and the public data network. On September 15, 2005, soon after Aya began operating, Syrian blogger al-Ahyam Salih reported that the new private ISP was filtering content.269

Syrians looking to subscribe to Internet service via the STE must bring a copy of their identity card and a printed copy of their application form to the Customer-Care Center between the hours of 8:30 a.m. and 2:30 p.m. The application form requires them to provide their name, their parents’ names, their nationality, their government-issued identification number, the date and place of their birth, their profession, and their username and password. The choices for professions are “educational institute, governmental, personal, industrial, professional, syndicate, organizational, commercial, or other”—a legacy, perhaps, of the recently abandoned preference for these professions in approving applications for Internet use.270 Fees were 2,000 Syrian pounds (U.S.$40) a month plus 1 Syrian pound ($0.02) a minute for a dialup connection. The SCS offers twenty-seven hours of service a month for 500 Syrian pounds ($10) (400 Syrian pounds, or $8, for SCS members), 250 Syrian pounds ($5) a month for thirteen hours (200 Syrian pounds, or $4, for SCS members), or “pay as you go” service for 36 Syrian pounds ($0.72) an hour.271 These rates make Internet access too expensive for many Syrians.

Despite these barriers, the number of users in Syria has grown quickly since the government first opened access. Current estimates put the number of Syrian users at around 500,000.272 The growth has been driven by strong popular demand and a marked shift in government policy that now recognizes the need to spread access while seeking to maintain control of Internet communications technologies. The Arab Advisors Group, an Amman-based business consulting firm, projects that the number of Syrian Internet users will grow at a compound annual rate of 24.9 percent between 2004 and 2009, meaning that 2.5 percent of the population, or 1.7 million people, may be online in 2009, up from less than one percent in 2004.273 So many Syrians are going online that service on the main government-affiliated ISPs has reportedly suffered. The government has focused its efforts on building the new public data network rather than improving the existing system. Better service on the public data network will likely further attract people to the new, private ISPs as they come online.

In response to a query from Human Rights Watch, the Syrian ambassador to the United States, Imad Moustapha, outlined the government’s efforts to make the Internet more widely available:

The government of Syria recognizes that widespread access to the Internet is restricted by the economic conditions of the Syrian people. The Syrian Ministry of Sciences and Technology has launched a national initiative in which lower-income families can buy an Internet-enabled PC for a relatively low price (U.S.$400) paid in twenty installments (The Popular Computer Project). A national Information Superhighway Project is supposed to increase the level of competition among ISPs, thus driving down access costs down.

The Ministry of Education has invested a huge amount of resources (human and financial) in order to introduce the Internet to every Syrian elementary and secondary (high) school. It has also incorporated the use of the Internet and computer-related skills into its national curriculum.

Every cultural center in Syrian towns and villages has a free-access Internet Room for citizens to access the Web free of any charges. FODOS, a Syrian NGO, has a number of mobile Internet units (buses converted into Internet access centers) that move from one village to another, particularly in the remote and less-developed countryside. At every station (village) the technicians accompanying the mobile Internet unit offer free tutoring and access to the Internet. This project has been very successful, and an increasing number of members of the business community are donating money towards increasing the number of these units.274

Internet Cafés

Internet cafés are now common in Damascus. The Syrian government told Human Rights Watch that there was “no legislations [sic] addressing the legal issue of whether Internet café owners/managers are legally responsible or not for the material sent or received at their premises,” but acknowledged that there were “a number of municipal regulations specifically applicable to the licensing and operation of Internet cafés.”275

Syrian Internet users report that they can access the Internet from the cafés without having to show identification or give their names. Many say the government does not need customer logs to monitor the cafés. Plainclothes security officials loiter around the cafés and near their entrances, watching who goes in and out and their activities online over their shoulders. These activities may be subject to criminal penalties. Activists and bloggers told Human Rights Watch that security officials can, moreover, compel uncooperative café owners to spy on their customers with threats to close the business on administrative grounds.276

Legal Framework

Article 38 of the Syrian constitution guarantees that:

Every citizen has the right to freely and openly express his views in words, in writing, and through all other means of expression. He also has the right to participate in supervision and constructive criticism in a manner that safeguards the soundness of the domestic and nationalist structure and strengthens the socialist system. The state guarantees the freedom of the press, of printing, and publication in accordance with the law.277

Article 32 further provides that “the privacy of postal and telegraphic contacts is guaranteed.”278 This protection of the privacy of written and electronic correspondence can, and should, be read to apply to email as well.

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, to which Syria is a state party, guarantees that “Everyone shall have the right to hold opinions without interference,” and that “Everyone shall have the right to freedom of expression; this right shall include freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing or in print, in the form of art, or through any other media of his choice.”279 It further holds that “no one shall be subjected to arbitrary or unlawful interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence.”280

The Syrian government also maintains a host of laws that criminalize the peaceful exercise of the right to free expression, to access information, and to privacy. As Anwar al-Bunni told Human Rights Watch, “If [the government] wants you, they will get you. It doesn’t matter whether they use the Press Code, the Penal Code, or the Emergency Law. The outcome is predetermined.”281

Emergency Law

Syria’s Emergency Law is at the center of the constellation of legislation that criminalizes peaceful opposition to the government. Syria has been under a state of emergency without interruption since December 1962, shortly after a group of military officers seized power.282 The day the Ba`ath Party seized power in a March 1963 counter-coup, they renewed the state of emergency with Military Command No. 2 of March 1963. The next day, they codified the military command as Legislative Decree No.1.

As codified, the law designates the prime minister as the martial law governor and the interior minister as his deputy and gives them extraordinary powers. Among its sweeping provisions are “the placing of restrictions on freedoms of individuals with respect to meetings, residence, travel and passage in specific places or at particular times; preventive arrest of anyone suspected of endangering public security and order; authorization to investigate persons and places; delegation of any person to perform any of these tasks.” It further allows for the censorship of letters, publications, broadcasts, and other forms of communication. The law forbids contravention of orders from the military governor, offenses “against the security of the state and public order,” offenses “against public authority,” offenses “which disturb public confidence,” and offenses that “constitute a general danger.” Meetings of more than five people are also banned without prior approval from the government.283

Article 4 of the ICCPR limits the application of Emergency Law to a time of “public emergency which threatens the life of the nation and the existence of which is officially proclaimed.” It further stipulates that state parties to the ICCPR may derogate from their obligations under the treaty only “to the extent strictly required by the exigencies of the situation, provided that such measures are not inconsistent with their other obligations under international law.”284

In its 2000 report to the U.N. Human Rights Committee, the body charged with monitoring states’ compliance with the ICCPR, Syria justified the continued application of the Emergency Law by saying that since Israel’s establishment in 1948, Syria had faced “a real threat of war by Israel,” and that this “gave rise to an exceptional situation that necessitated the rapid and extraordinary mobilization of forces in the Syrian Arab Republic and, consequently, the promulgation of legislation to ensure the Administration’s ability to act rapidly in the face of these imminent threats.”285

On July 28, 2005, the U.N. Human Rights Committee

Note[d] with concern that the state of emergency declared some forty years ago is still in force and provides for many derogations in law or practice from the rights guaranteed under articles 9, 14, 19 and 22, among others, of the Covenant, without any convincing explanations being given as to the relevance of these derogations to the conflict with Israel and as to the necessity of these derogations to meet the exigencies of the situation claimed to have been created by the conflict.286

The Press Law

The Press Law—Decree No. 50/2001, promulgated on September 22, 2001—provides for sweeping controls of newspapers, magazines, and other periodicals, as well as virtually anything else printed in Syria, from books to pamphlets and posters. Provisions apply to publishers, editors, journalists, authors, printers, distributors, and bookstore owners, and subject them to imprisonment and steep fines for violations of the law.287 A Syrian court has ruled that anyone with a photocopy machine, a fax machine, a printer, or any means of printing is subject to the Press Law.288 This suggests that it would also apply to online publishing. “The new media law legalizes martial law—and that’s all it does,” journalist and human rights activist Nizar Nayyuf declared shortly after his release from prison.289

The decree prohibits the publication of information on a wide range of topics—including articles and reports that touch on what the authorities consider to be “national security” and “national unity”—and punishes the publication of “falsehoods” or “fabricated reports” with prison terms of up to three years and fines of 500,000 to 1 million Syrian pounds (US$10,000 to $20,000).290 Imprisonment of up to three months is the penalty for publishing a periodical without a license from the prime minister, who is empowered to deny licenses “for reasons he deems to be related to public interest.”291 Periodicals that are not licensed as political publications are prohibited from publishing “political” articles.292 The publication of “propaganda” financed “directly or indirectly” with funds from foreign governments or foundations is punishable by prison terms of up to one year.293 Convictions for libel, slander, or defamation carry a maximum one-year prison sentence.

Article 51a stipulates that maximum penalties “shall be imposed if such acts have been committed by reason of ill-will, or caused public unrest, or harm to international relations, offense to state dignity, national unity, the morale of the army and the armed forces, or caused some damage to the national economy and the currency.” None of the broad terms used in Article 51a is defined in the decree.

A list of topics banned from publication is set forth in Article 29 of the decree:

- Information about the investigation and charges in misdemeanor and criminal cases “prior to their being delivered by the court in an open session.”

- “Details of cases of libel, defamation, slander, or calumny.”

- “Details of secret trials and hearings of cases dealing with divorce, separation, hereditary disputes and those banned by courts, and reports made by forensic doctors in crimes of immorality.”

- “Confidential reports of the National Assembly.”

- “Articles and reports about national security, national unity, details of the security and safety of the army, its movements, weapons, supplies, equipment and camps, with the exception of information issued by the Ministry of Defense and approved for publication.”

- “Books, correspondence, articles, reports, pictures and news affecting the right to privacy.”

These prohibitions appear to rule out investigative reporting and commentary on a wide range of cases brought before Syria’s judicial system, as well as issues under consideration in the elected legislature, two important spheres of government activity where the public has a right to know.

The list of banned subjects also ensures that writers will exercise restraint with respect to information and analysis about controversial social and political issues. The term “national unity” is exceedingly vague, and can be applied to virtually any subject of domestic political concern. Similarly, the elasticity of the phrase “national security” requires journalists and others to exercise extreme caution on all subjects related to foreign policy and the Syrian military.

Other vaguely worded laws further restrict press freedom. Articles 286 and 287 of the Penal Code criminalize spreading any news abroad.294 Decree No. 6 of 1965, used to imprison human rights defender Aktham Na`issa, criminalizes “publishing news aimed at shaking the people’s confidence in the revolution.” Other laws criminalize “opposition to the revolution, its goals, or socialism.”295

Implementation of these laws has stifled the free flow of information and opinions in Syria, and has denied citizens the right to be fully informed in this era of almost instantaneous global information exchange.

In a letter to Human Rights Watch, Ambassador Moustapha said the Syrian government planned to reform its media laws:

Syria has only recently realized the need to reform its media policies and make them more reflective of the recent developments in ICT, international media policies, and world-class standards. Taking into account that conventional media development is hindered by a legacy of outdated legislations and regulations, and while the government of Syria has undertaken a commitment to make the media more open, transparent, and free, the electronic media has benefited from the fact that no legislations and regulations exist for the electronic media, thus enjoying a level of freedom and flexibility that allowed them to become the major media outlets in Syria, while conventional printed and broadcast media is lagging behind.296

On July 13, 2005, according to the government’s letter to Human Rights Watch, Nizar Mayhoob, a spokesman for the Syrian Ministry of Information, announced that Syria would issue a new media law,

which will enhance the law issued in 2001 by overcoming its inadequacies. This new law covers all media issues and all media channels including: Internet [original emphasis], radio, and television. Dr. Mayhoob mentioned that this development illustrates the seriousness of the Syrian government in fostering the growth of a vibrant free, private and public, media sector in Syria.297

A highly placed source in Syria who has seen a draft of the new law said it contained one page of regulations on the Internet. According to its provisions, those responsible for operating Web sites will reportedly be required to have a university degree, be at least 25 years of age, and live in Syria. This last provision, this source said, was intended to ensure that operators of Web sites registered in Syria would be subject to the penalties set out in the new law. The law’s provisions as to what material would be permissible were reportedly “kept flexible and vague to give the government latitude. They will allow ‘the maximum’ freedom of expression.”298

The Supreme State Security Court

All of the Syrians imprisoned for their online activities discussed in this report were sentenced by the Supreme State Security Court, established in March 1968 to try political and security cases. Decree 47/1968, which created the court, specifically stated that the procedural rules of the court would not be “confined to the usual measures” that governed Syria’s justice system. Evidence could be introduced that had no ordinary standing in law, such as hearsay or the opinion of the prosecutor. The absence of any rules of procedure eliminates any possibility of appeal on procedural grounds. Proceedings are closed. The president needs to confirm decisions.299

Aktham Na`issa—whose hearings before the court lasted from April 2004 to June 2005—described proceedings in the court as “a farce.”300 Anwar al-Bunni, the prominent Syrian human rights lawyer referred to above, has represented several high-profile clients sentenced by the court for their political activities.301 “The Security Court is completely outside the rule of law and the constitution,” he said. “Detainees arrive at the court with their case files, the verdict, and the sentence. It is only a symbolic procedure.”302

Detentions

The Political Joke

In December 2000, not long after the Syrian government first allowed email, the wife of a prominent Syrian businessman received an email containing a cartoon showing a donkey with President Bashar al-Asad’s head mounting another donkey with Lebanese Prime Minister Emile Lahoud’s head. The woman, a resident of Damascus, forwarded the message to her friends. After one of the recipients informed on her, Syrian authorities arrested and detained her without charge for nine months in what one writer described as “deliberately humiliating conditions.”303

`Abd al-Rahman al-Shaghuri

On February 23, 2003, Syrian secret police agents, operating without a warrant, arrested `Abd al-Rahman al-Shaghuri and confiscated his computer, his fax machine, and his elderly mother’s car.304 On June 26, 2003, the U.N. Special Rapporteur on torture and detention, the Chairman-Rapporteur of the Working group on Arbitrary Detention, and the Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers sent an urgent joint appeal to the Syrian government about his case.305 On September 15, 2003, the Syrian government replied that al-Shaghuri been detained for emailing articles copied from the Akhbar al-Sharq (Levant News) Web site, http://www.thisissyria.net. The government said it considered the site’s content “detrimental to the reputation and security of the nation,” and “full of ideas and views opposed to the system of government in Syria.”306

His captors beat and tortured al-Shaghuri and held him incommunicado in the tiny, underground cells known as “tombs” during his eighteen-month interrogation at in the Palestine Branch of Military Intelligence in Damascus before moving him to the Sednaya military prison on the outskirts of the city. On June 20, 2004, the Security Court found him guilty, under the Press Law, of “publishing lies” and disseminating articles “that harmed the image and security of Syria.” The court sentenced him to three years in prison and then reduced the sentence to two-and-a-half years. He was released on August 31, 2005.

Yahya al-Ous and the Qutaish Brothers

In September 2002 two construction workers were reportedly killed while digging a tunnel in Damascus. Over the course of the following few weeks, Haytham Qutaish, his brother Muhannad, and Yahya al-Ous were arrested for sending emails to a Gulf-based newspaperabout the incident.307 They had previously sent articles criticizing the Syrian government’s economic, political, and human rights policies and government corruption.

Syrian Military Intelligence held them in Sednaya prison for nearly two years before the Supreme State Security Court found the three guilty, on July 25, 2004, of “receiving secret information on behalf of a foreign state which threatens the security of Syria” and using the Internet to publish “false news outside of Syria” under the terms of the Press Law. The court found the Qutaish brothers guilty of “encouraging the transfer of secret information.” The court further found Haytham Qutaish guilty of “writing that threatens the security of Syria and her relations with foreign states.”308 The court sentenced Haytham Qutaish and his brother Muhannad to four and three years in prison, respectively. As of November 1, 2005, Muhannad was still in prison, though his sentence had expired twenty days earlier.309 As of September 2005, Haytham was rumored to have been released. Al-Ous spent two years in prison before being released.310

Mas`ud Hamid

On June 25, 2003, police violently dispersed a demonstration of Syrian-Kurdish children in front of the U.N. Children’s Fund (UNICEF)’s Damascus office. Mas`ud Hamid, a Kurdish-Syrian journalism student, posted photographs of the event on several Web sites, including the German-based Kurdish Web site http://www.amude.com. One month later, on July 24, 2003, Public Security officers arrested Hamid as he was taking an exam.311 Witnesses told Reporters sans frontières that the manner of his arrest, in which he was handcuffed in front of a room full of students, seemed intended to intimidate the future journalists.312 The authorities held him in solitary confinement in `Adra prison for one year before allowing him monthly visits from his lawyer and family. Interrogators reportedly tortured him on several occasions and beat him with a studded whip on the soles of his feet.313

On October 10, 2004, the Supreme State Security Court sentenced Hamid to three years in prison after finding him guilty of “membership of a secret organization” and having “attempted to annex part of Syrian territory to another country”—charges frequently leveled against detained Syrian Kurds.314

Hamid remains in `Adra prison, where he risks further torture.

Habib Salih

On May 29, 2005, Military Intelligence officers arrested Habib Salih in Tartus, approximately 100 miles (130km) north of Damascus. He had only been released on September 9, 2004, after having been imprisoned for three years for his participation in the civil society movement of the “Damascus Spring.” On May 29, 2005, Military Intelligence officers arrested him for posting on two Web sites a series of open letters addressed to the delegates attending the June 2005 Ba`ath Party Conference in which he detailed his prison experiences. In the months since his release, he had also written critical articles for the Lebanese newspaper an-Nahar and the banned Web site http://www.elaph.com. The authorities quickly transferred him to the investigations office, where he risks torture.315 Human Rights Watch has been unable to obtain further information on his case.

Censorship and Surveillance

In his letter to Human Rights Watch, Ambassador Moustapha outlined the Syrian government’s policy on online censorship thus:

Yes, certain types of Web sites are blocked in Syria by all ISPs: pornography, fanatic religious sites, and extremist zionist [sic] Web sites. Some ISPs have their own policy for blocking Web sites that are not applied by other ISPs (e.g. the Syrian Telecom ISP blocks access to Yahoo! mail and MS mail services, while the SCS ISP does not block access to these services).316

In practice, the Syrian government censors the Internet extensively under the terms of the Emergency Law, which allows for the censorship of letters, publications, broadcasts, and other forms of communication. One Syrian Internet user called the censorship regime imposed by the STE and the SCS “hell.”317 It reportedly blocks newspaper Web sites, such as that of London’s pan-Arab al-Hayat, when they run articles voicing particularly cutting criticisms. The authorities consistently block Elaph—http://www.elaph.com, a U.S.-based Arabic-language online newspaper—as well as Akhbar al-Sharq (http://www.thisissyria.net); the Web site of the independent, London-based Syrian Human Rights Committee, http://www.shrc.org; the internal opposition site http://www.all4syria.org; the news site Islam Online (http://www.islamonline.net); the online version of the Arab Times newspaper (http://www.arabtimes.com); and any Web sites registered with an “.il” top-level domain—that is, any site whose address indicates that it is based in Israel.318

The STE also reportedly blocks “anonymizing” Web sites. Such sites allow users to connect to the broader Internet via a “proxy,” or intermediary server, which in turn can enable people to circumvent government censorship.319 Governments that censor web content frequently censor proxy servers that could allow people to circumvent online censorship.

Web sites of human rights and press freedom groups such as Amnesty International and Reporters sans frontières (http://www.amnesty.org and http://www.rsf.org, respectively), which are primarily written in European languages, are available from Syria today, suggesting that state censorship focuses on Arabic-language material.320

The government has reportedly stopped trying to block its citizens from accessing popular web-based email sites such as Hotmail and Yahoo!.321 The government had previously blocked these sites in an effort to prevent users from circumventing state censorship of email correspondence passing through the government’s mail servers.

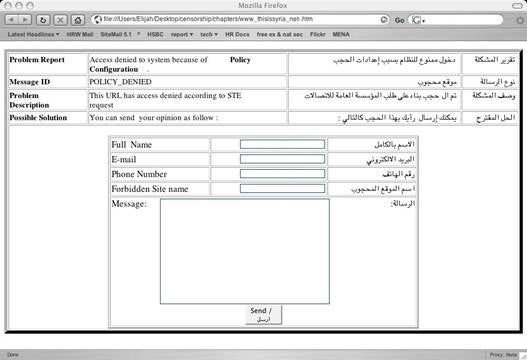

Aya started censoring Web sites on September 15, 2005.322 Today, when Syrians attempt to read a blocked page using Aya as an ISP, they get a page saying “This URL has access denied according to STE request:”

In mid-October 2005, researchers from Human Rights Watch and the Open Net Initiative (ONI), working in cooperation with local Syrian volunteers, simultaneously tested 1,095 Web sites from within Syria and from a location outside Syria. Tests conducted within Syria used the new, privately owned ISP, Aya—the first to operate over the new public data network. Of these, fifty-nine were confirmed to be blocked.

Of the 1,095 sites researchers tested, 856 had no particular bearing on Syria, but included, among others, popular news sites from around the world, the Web sites of international human rights and women’s rights organizations, religious Web sites, pornographic sites, sites that allow people to browse the Web via a proxy server, and sites of interest to lesbians, gays, bisexuals, and transgendered people.

The test indicated that, for the moment, the new public data network is less intensively censored than the old SCS and STE networks. In early October 2005, however, Syrian Minister of Communications Bashir al-Munajjid ordered a sweeping censorship program on the public data network.323 Our tests, carried out soon after the program was announced, confirmed that network administrators had moved swiftly to begin implementing the order.

Based on STE requests, six popular proxy servers were blocked. Three popular voice-over-IP Web sites were blocked. http://groups.msn.com, which allows people to exchange messages over email and online bulletin boards, was blocked. All4Syria.org, Ayman `Abd al-Nur’s site, was already blocked, as were http://www.elaph.com, http://www.thisissyria.net, http://www.arabtimes.com, and http://www.alquds.co.uk, the online version of the pan-Arab London-based newspaper al-Quds al-Arabi. The Web sites of Kurdish political parties and organizations were extensively blocked, as were those of foreign-based Syrian opposition parties.

Syrian bloggers told Human Rights Watch that the government was interfering with the very means by which information is transmitted over the Internet. The Internet is a network of computers that communicate with each other according to agreed protocols. For convenience’s sake, each protocol has been assigned a numbered “port” that corresponds to a specific means of transmitting data—such as one might use to send emails, for example, or to read a Web site.

Syrian bloggers and computer specialists told Human Rights Watch that the government-affiliated ISPs have interfered with communications from the ports most commonly associated with the Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP), which is used to send most email messages. When setting up a local email client, such as Mozilla’s Thunderbird or Microsoft Access, users must specify an SMTP address to send emails. In Syria, any traffic from these ports is blocked if it does not pass through STE or SCS servers, an arrangement that would presumably facilitate monitoring. And so resourceful Syrian Internet users reconfigure their computers to reassign the port associated with the SMTP protocol. “We have thousands of ways around every problem,” one Syrian technology expert told Human Rights Watch.324

According to Syrian bloggers and computer specialists, the government-affiliated ISPs have also restricted connections originating from ports associated with the File Transfer Protocol (FTP), the protocol most commonly used to publish to Web sites. Syrian users could download material over this protocol, but they could not use it upload anything.325 Web site administrators could publish files to Web sites over the HTTP protocol, but this is a slower and more unreliable method. Such policies, which make it more difficult for Syrians to make Web sites, can only retard the diffusion of the Internet in the country. On November 2, 2005, as this report was going to press, Human Rights Watch received an unconfirmed report from a Syrian computer programmer that SCS had stopped blocking uploads on the FTP protocol.326

As one Syrian systems administrator complained on a bulletin board for Syrian computer specialists, “If the ISPs would like to help us do our work, they should unblock all outgoing connections to all ports and services. They can still block Web sites from the proxy.”327

Syrian Internet users told Human Rights Watch that the government routinely blocks the ports used by VoIP (voice over IP) software. One said he would prefer the government to block these services by blocking the service providers’ IP address, rather than blocking entire ports.328

They further complained that the government blocks access to Open Source Version Control (CVS), an important resource for developers to exchange source code among the global network of open-source programmers. When Richard Stallman, the founder of the free software movement, the GNU Project, and the Free Software Foundation, traveled to Syria in late February 2005, he reported the frustrating restrictions he encountered there.329 “Blocking CVS is equivalent to strangling the software industry in Syria,” one Syrian developer wrote in an email to Human Rights Watch.330

The government told Human Rights Watch that in Syria, “There are no legislations regulating the use of encryption in electronic communications.”331

Conclusion

The Syrian government says it “has only recently realized the need to reform its media policies and make them more reflective of the recent development in ICT, international media policies, and world class standards.”332 The Syrian government has an extraordinary opportunity to act on that sentiment and to uphold its constitutional and international commitments to free expression with the new media law the Information Ministry promised at the June 2005 Ba`ath Party Conference. Accordingly, the government should:

- Continue to invest in expanding access to the Internet, and refrain from diverting funds reserved for improving networks to improve surveillance or censorship technology.

- Immediately and unconditionally release all those imprisoned or detained solely for exercising their right to free expression, online or otherwise, including but not limited to: Mas`ud Hamid, who was imprisoned after posting photographs of police violently dispersing a violent demonstration, and Muhannad Qutaish, imprisoned for sending e-mails to a Gulf based newspaper.

- Legislate that all Syrians should have free and unimpeded access to Internet cafés and Internet-connected libraries, and that such businesses should not be required to provide customer records without a specific court order based on a compelling and particularized showing of need in relation to the commission of a crime.

- Stop blocking Web sites for their political or their human rights content, including, but not limited to, the following sites: http://www.all4syria.org, http://www.elaph.com, http://www.thisissyria.net, http://www.shrc.org, http://www.islamonline.net, http://groups.msn.com, http://www.alquds.co.uk, and http://www.arabtimes.com.

- Scrupulously respect the rights of suspects and defendants in criminal cases, including counter-terrorism cases, and prohibit the use of evidence obtained by torture or without legal authorization. The Supreme State Security Court should grant all defendants a fair and open trial governed by transparent rules of procedure, and rules of evidence should conform to international standards.

- Repeal laws that abridge the right to privacy or the right to freely access or disseminate information or opinions, including the Press Law (Decree No. 50/2001) which provides for sweeping controls of virtually all printed publications in Syria and appears to apply to online publishing as well.

- Repeal the Emergency Law, in particular those provisions that restrict freedom of expression, online or otherwise, and freedom of association.

- Seek to pass legislation that

- Provides strict guarantees of the privacy of electronic communications.

- Allows monitoring of email or other forms of electronic communication only when authorized by an independent court of law upon a compelling showing of genuinely criminal activity.

- Contains explicit guarantees of the right to freedom of expression, the right to access information, and the right to privacy of communications as outlined in the Syrian constitution and articles 19 and 17 of the ICCPR, respectively.

- In accordance with international standards, seek to pass legislation that

- Affirmatively protects the right of writers to advocate nonviolent change of government policies or the government itself;criticize or insult the nation, the government, its symbols, or officials; and communicate information about alleged violations of international human rights and humanitarian law.

- Removes unlimited liability from private ISPs for carrying illegal content.

- Permits the free use of encryption and other techniques to ensure the privacy of online communications. Law enforcement agencies should be allowed to decrypt private communications only after convincing an independent court of a compelling and particularized need for the purposes of protecting the public order, public morals, or national security.

- Cease intimidation and harassment of online writers who express critical opinions or report on human rights violations. The right to freedom of expression precludes unauthorized or harassing surveillance or intimidation of online journalists and other practices designed to chill freedom of expression.

[234] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Aktham Na`issa, September 28, 2005.

[235] Confidential email on file with Human Rights Watch.

[236] Translation of President Bashar al-Assad’s July 17, 2001, inauguration speech provided by the Syrian Arab News Agency (SANA), via http://www.al-bab.com/arab/countries/syria/bashar00a.htm, as revised on March 31, 2001. The more recent version currently posted on the government news agency’s site, http://www.sana.org/english/Prisedent/President%20Speech/Bashar%20al-Assad%20speech%20after%20taking%20oath.htm, is significantly shorter and no longer contains widely quoted passages speaking of the need for reform. Both sites accessed September 29, 2005.

[237] Donna Abu-Nasr, “Syrian Chief Caught Between Old Guard, Own Reformist Ideas,” Associated Press, March 13, 2005, http://www.detnews.com/2005/nation/0503/14/A05-115675.htm, accessed September 29, 2005.

[238] Riad Saif, an independent member of parliament arrested September 6, 2001, quoted in Alan George, Syria: Neither Bread nor Freedom (London: Zed Books, 2003) p. 23.

[239] Syria’s government press “unreadable:” Ammar Abdulhamid, “Syrian Media Reform: A Glass Half Full or Half Empty?” The Daily Star, Beirut, February 5, 2005, http://www.dailystar.com.lb/article.asp?edition_id=10&categ_id=5&article_id=12398, accessed September 29, 2005. On Syria’s record of detaining and torturing journalists, see, e.g. the International Press Institute’s and UNESCO’s dossiers on Nizar Nayyuf, http://www.freemedia.at/IPIReport/Heroes_IPIReport2.00/35Nayyouf.htm and http://portal.unesco.org/ci/en/ev.php-URL_ID=5711&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html, respectively, or Amnesty International, “Syria: Smothering Freedom of Expression: the Detention of Peaceful Critics,” June 6, 2002, http://web.amnesty.org/library/Index/ENGMDE240072002?open&of=ENG-SYR, accessed September 29, 2005.

[240] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Ayman `Abd al-Nur, October 2, 2005.

[241] Ibid.

[242] Ibid.

[243] Ibid.

[244] Anthony Shadid, “Syria’s Voices of Change,” Washington Post, May 25, 2005, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2005/05/24/AR2005052401431_pf.html, accessed May 25, 2005.

[245] Joe Pace interview with Ayman Abd al-Nour, July 25, 2005, http://faculty-staff.ou.edu/L/Joshua.M.Landis-1/syriablog/2005/07/interview-with-ayman-abdelnour-by-joe.htm, accessed September 30, 2005.

[246] Ibid.

[247] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Ayman `Abd al-Nur, October 2, 2005.

[248] Quoted in Megan K. Stack, “Arabs Take Bytes at Regimes,” The Los Angeles Times, September 12, 2005, http://www.latimes.com/technology/la-fg-technology12sep12,1,3706022,full.story?ctrack=1&cset=true, accessed October 1, 2005.

[249] Maha Taki, Weblogs, Bloggers and the Blogosphere in Lebanon, Syria and Jordan: An Exploration, dissertation submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the M.A. Degree in Communications, University of Westminster, London, 2005.

[250] Ibid.

[251] Integrated Regional Information Network (IRIN), “Syria: Focus on Freedom of Speech Through the Internet,” September 4, 2005, http://www.irinnews.org/print.asp?ReportID=48894, accessed October 15, 2005.

[252] Confidential email to Human Rights Watch, September 2005.

[253] Confidential email to Human Rights Watch, October 2005.

[254] Hasna Askhita, “The Internet in Syria,” paper delivered at the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions’ meeting in Beirut, March 2-4, 2000, http://nmit.georgetown.edu/papers/askhita2.htm, accessed June 29, 2005.

[255] Alan George, p. 136.

[256] Interview with Joe Pace, August 7, 2005, http://faculty-staff.ou.edu/L/Joshua.M.Landis-1/syriablog/2005/08/anwar-al-bunni-interview-with-syrias.htm, accessed October 1, 2005.

[257] Confidential email to Human Rights Watch, September 2005.

[258] Confidential email to Human Rights Watch, September 2005.

[259] IRIN, “Syria: Focus on Free Expression.”

[260] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Aktham Na`issa, September 28, 2005.

[261] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Anwar al-Bunni, August 22, 2005.

[262] Ibid.

[263] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Anwar al-Bunni, September 28, 2005.

[264] Email from `Ammar `Abd al-Hamid to Human Rights Watch, October 2005.

[265] IRIN, “Syria: Focus on Free Expression.”

[266] Email from `Ammar `Abd al-Hamid to Human Rights Watch, October 2005.

[267] Amr Salem, “Syria’s Cautious Embrace,” Middle East Insight, March-April 1999, pp. 49-50.

[268] Confidential email to Human Rights Watch, August 2005.

[269] http://www.alayham.com/modules/news/article.php?storyid=359, accessed October 10, 2005.

[270] http://www.190.sy/index.php?d=251, accessed October 2, 2005.

[271] http://www.scs-net.org/modules.php?op=modload&name=connections&file=dialup_en, accessed October 2, 2005.

[272] Ibid. Syrian online writers and human rights activists Human Rights Watch spoke or corresponded with also consistently used this number.

[273] Serene Zawadeh, Syria Internet and Datacomm Landscape Report (Amman: Arab Advisors Group, June 2005), p. 32.

[274] Letter from Imad Moustapha, Ambassador of Syria to the United States, to Human Rights Watch, received August 2, 2005 (See Appendix).

[275] Ibid.

[276] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Aktham Na`issa, September 28, 2005; confidential email from a Syrian blogger to Human Rights Watch, September 2005.

[277] The Constitution of the Arab Republic of Syria, Article 38, http://www.oefre.unibe.ch/law/icl/sy00000_.html, accessed September 30, 2005.

[278] Ibid.

[279] International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), G.A. res. 2200A (XXI), 21 U.N. GAOR Supp. (No. 16) at 52, U.N. Doc. A/6316 (1966), 999 U.N.T.S. 171, entered into force Mar. 23, 1976, article 19, http://www.unhchr.ch/html/menu3/b/a_ccpr.htm, accessed September 3, 2005.

[280] ICCPR, article 17.

[281] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Anwar al-Bunni, September 28, 2005.

[282] The short-lived government of the High Arab Revolutionary Command, which had seized power in a 1961 coup and seceded from the United Arab Republic, formed with Egypt in 1958, first declared the state of emergency with Legislative Decree No. 51(5) of December 22, 1962.

[283] Legislative Decree No. 1 of March 9, 1963.

[284] The continued application of the Emergency Law may be invalid under its own provisions. The source of the law, Legislative Decree No. 51(5) of 1962, holds that a “State of Emergency shall be declared by a decree from the Cabinet, presided over by the President of the Republic. It must be carried out by a majority of two-thirds and be made known to the chamber of deputies at its next meeting.” But the 1963 law was issued by military decree, was never approved by the government, and was never submitted to the chamber of deputies.

[285] U.N. Human Rights Committee, Consideration of Reports Submitted by States Parties under Article 40 of the Covenant. Second Periodic Report of States Parties Due in 1984. Syrian Arab Republic, August 25, 2000, available at http://www.arabhumanrights.org/countries/syria/ccpr/ccpr-c-syr-2000-2e.pdf.

[286] U.N. Human Rights Committee, Consideration of Reports Submitted by States Parties Under Article 40 of the Covenant. Concluding Observations of the Human Rights Committee. Syrian Arab Republic, CCPR/CO/84/SYR, July 28, 2005, available at http://www.ohchr.org/english/bodies/hrc/hrcs84.htm, accessed September 30, 2005.

[287] A fuller analysis of the 2001 Press Law is available in Human Rights Watch, Memorandum to the Syrian Government, Decree No. 51/2001: Human Rights Concerns, January 31, 2001, http://hrw.org/backgrounder/mena/syria/.

[288] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Aktham Na`issa, September 28, 2005.

[289] Alan George, Syria: Neither Bread Nor Freedom, p. 121. Nayyuf was sentenced to ten years in prison in 1992 as a founding member of the Committee for the Defense of Democratic Freedoms and Human Rights in Syria (CDF). He was held in solitary confinement, subjected to torture, and denied access to medical treatment for nine years before he was released in 2001.

[290] Decree No. 50/2001, Article 51a.

[291] Ibid., Article 12.

[292] Ibid., Article 44d.

[293] Ibid., Article 55(b).

[294] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Anwar al-Bunni, September 28, 2005.

[295] Human Rights watch telephone interview with Aktham Na`issa, September 28, 2005.

[296] Letter from Ambassador Moustapha to Human Rights Watch.

[297] Ibid.

[298] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with a Syrian who requested anonymity, September 30, 2005.

[299] For more on the exceptional courts, see Middle East Watch, pp. 23-26.

[300] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Aktham Na`issa, September 28, 2005. Aktham Na`issa was charged with “opposing the objectives of the revolution,” “disseminating false information,” and “affiliation with international organizations.” The government acquitted Na`issa of all charges on June 26, 2005. Before his acquittal, eleven international human rights organizations, including Human Rights Watch, recognized his work with the Martin Ennals Award for Human Rights Defenders. More information about the prize and Na`issa is available at http://hrw.org/english/docs/2005/01/12/syria9994.htm.

[301] In June 2002, for example, he was beaten and forcibly ejected from the court when he demanded an investigation into allegations of mistreatment made by his client, ‘Arif Dalila, an economist, Damascus University professor, and a founder of a civil-society forum who was arrested on September 9, 2001, after appearing on Al-Jazeera.

[302] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Anwar al-Bunni, August 22, 2005.

[303] Alan George, p. 136. George does not supply the woman’s name.

[304] Syrian Human Rights Commission, “Urgent appeal to release Abdel Rahman Rafiq al-Shaghouri,” June 16, 2003. http://www.shrc.org.uk/data/aspx/d1/1191.aspx, accessed July 25, 2005.

[305] U.N. Commission on Human Rights, Report of the Special Rapporteur on Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, Theo van Boven, Addendum: Summary of Information, Including Individual Cases, Transmitted to Governments and Replies Received, E/CN.4/2004/56/Add.1, March 23, 2004.

[306] Cited in Amnesty International, “Syria: Further information on Prisoner of conscience/legal concern/torture and other ill-treatment, 'Abdel Rahman Shaghouri,” June 21, 2004, http://web.amnesty.org/library/Index/ENGMDE240462004?open&of=ENG-315, accessed October 1, 2005.

[307] Amnesty International and Reporters sans frontières have said the paper was based in the United Arab Emirates. Syrian publisher and women’s rights activist Ma`an `Abd al-Salam told Human Rights Watch in an August 23, 2005, telephone interview that the paper was Kuwait’s al-Siyasa.

[308] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with their attorney, Anwar al-Bunni, August 22, 2005; Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Syrian human rights activist and publisher Ma`an `‘Abd al-Salam, August 22, 2005.

[309] Statement from the Syrian Human Rights Organization, November 1, 2005 (in Arabic).

[310] Reporters sans frontières, “Three Internet Users Sentenced to Prison Terms of Two to Four Years,” July 26, 2004, http://www.rsf.org/article.php3?id_article=11013, accessed October 1, 2005.

[311] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Anwar al-Bunni, September 28, 2005.

[312] Reporters sans frontières, “Reporters Without Borders Calls on Syrian President for Release of Journalism Student,” February 16, 2004, http://www.rsf.org/article.php3?id_article=9261, accessed October 1, 2005.

[313] Reporters sans frontières, “Syria: Massud Hamid,” http://www.rsf.org/article.php3?id_article=15053, accessed October 1, 2005.

[314] For more on the Syrian government’s treatment of the Kurdish minority, see Human Rights Watch, Syria: The Silenced Kurds, October 1996, http://hrw.org/reports/1996/Syria.htm. Amnesty International has reported that Hamid’s jailors tortured him and beat him on his head and his back for participating in a hunger strike with fellow Kurdish prisoners in protest of prison conditions. Amnesty International, “Syria: Medical Action Health Concern: Six Imprisoned Human Rights Defenders,” http://web.amnesty.org/library/Index/ENGMDE240542005?open&of=ENG-SYR, accessed October 1, 2005.

[315] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Anwar al-Bunni, August 22, 2005;The Egyptian Organization for Human Rights, “The Egyptian Organization for Human Rights Calls on Syrian Authorities to End Intimidation, Kidnapping, and Arbitrary Detention of Human Rights Activists,” June 4, 2005, http://www.eohr.org/press/2005/pr0604.htm, accessed September 10, 2005.

[316] Letter from Ambassador Moustapha to Human Rights Watch.

[317] Confidential email to Human Rights Watch, October 2005.

[318] Human Rights Watch telephone interviews with Maan Abd al-Salam, Anwar al-Bunni, Aktham Na`issa, and Ayman Abd al-Nour over the course of August and September 2005. See also Amnesty International, “Syria Imprisons Internet Users,” August 2004, http://web.amnesty.org/wire/August2004/Syria; Committee to Protect Journalists, Attacks on the Press, 2004: Syria, March 15, 2005, http://www.cpj.org/attacks04/mideast04/syria.html; Reporters sans frontières, The Internet Under Surveillance, 2004: Syria, http://www.rsf.org/rubrique.php3?id_rubrique=433.

[319] Confidential emails from Syrian bloggers, Internet users, and former residents of Syria to Human Rights Watch.

[320] Reporters sans frontières, The Internet Under Surveillance, 2004: Syria, http://www.rsf.org/article.php3?id_article=10767, accessed October 27, 2005.

[321] IRIN, “Syria: Focus on Freedom of Speech Through the Internet,” September 4, 2005, http://www.irinnews.org/report.asp?ReportID=48894&SelectRegion=Middle_East&SelectCountry=SYRIA, accessed October 2, 2005.

[322] Confidential emails from Syrian bloggers and computer programmers to Human Rights Watch, September – October 2005.

[323] al-Ayham Salih, http://www.alayham.com/modules/news/article.php?storyid=366, October 6, 2005, accessed October 27, 2005.

[324] Confidential email to Human Rights Watch, October 2005.

[325] Comments left by al-Ayham Salih, http://www.sif-syria.com/index.php?option=com_nobforum&Itemid=41&func=view&id=102&catid=13, accessed October 31, 2005.

[326] Confidential email on file with Human Rights Watch, November 2, 2005.

[327] Comments left by al-Ayham Salih on http://www.sif-syria.com.

[328] Ibid.

[329] For more on the free software movement, see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Free_software_movement; for Stallman’s report from Syria, see, for example, http://www.fsf.org/blogs/rms/entry-20050315.html, accessed October 31, 2005.

[330] Confidential email to Human Rights Watch, October 2005.

[331] Letter from Ambassador Moustapha to Human Rights Watch.

[332] Ibid.

| <<previous | index | next>> | November 2005 |