<<previous | index | next>>

I. Introduction

Ruwaida al-Hajin and her two sons were killed by thousands of tiny, dart-like flechette rounds one Friday night in August 2002, during a summer holiday picnic. That same month Fatima Abu Dhahir was shot while sleeping in her front yard to avoid the heat. These and many other civilians are the faceless victims of lethal force used by the soldiers of the Israel Defense Forces (IDF). Their deaths may have resulted from the unlawful use of lethal force or simply be the unfortunate result of incidents of armed conflict. But no one will ever know precisely what happened, because their deaths were never impartially investigated.

The situation is different for Ahmad Abu `Aziz, a six-year-old who died in June 2002 when he went out to buy a bar of chocolate. His death, recorded on video, was investigated by the IDF, as were some seventy other cases. But because Israeli military investigations are shrouded in secrecy and the results rarely made public, no one can judge whether the investigations were impartial – or if they had any result. The soldier alleged to have killed Ahmad along with his little brother and three other civilians is unlikely to stand trial. At the time of Human Rights Watch’s inquiry, he had reportedly left the army and was traveling overseas.

It is the army’s lack of accountability that has produced what a military court in 1989 termed this “bitter fruit.”21 This lack of accountability has reinforced the widely held belief that the Israeli army does not hold its forces responsible for the wrongful killing, injury, or ill-treatment of Palestinian or foreign civilians. Unlawful practices have gone uninvestigated and unchecked. With greater discipline and accountability on the part of Israeli forces, many civilians would not have been maimed or killed. And the lack of accountability is reflected in a surreal public relations war, in which the IDF first publishes inaccurate and self-serving accounts of victims’ deaths and later claims moral victory on the very few occasions when it finally agrees to investigate them.

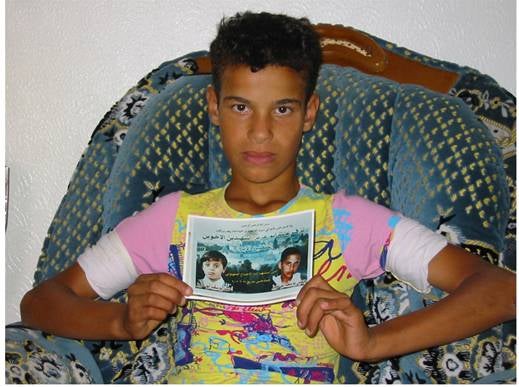

The brother of Ahmad and Jamil Abu-Aziz

holds of a photo of his brothers, killed by IDF tank fire on June 21, 2002. An

indictment was issued for a soldier for allegedly killing the two brothers and

two others to enforce a curfew. According to media reports in January 2004, the

soldier had left Israel.

© 2002 Miranda Sissons/Human Rights Watch

The public outcry in the several incidents in which the IDF has injured Israeli civilians illustrates how arguments against conducting proper investigations to some extent rest on the assumption that those injured or killed may be Palestinians but not Israeli Jews. The case of Gil Na’amati, who was shot in the knee by IDF soldiers while participating in an unarmed demonstration against the West Bank separation barrier on December 26, 2003, is illustrative: Na’amati, an Israeli citizen, had recently completed his military service in a combat unit. In the public outcry that followed, the IDF reportedly opened both a special investigation and a Military Police investigation into this shooting. Chief of Staff Moshe Ya’alon was quoted as saying, “The Israeli army is not given orders to shoot at Israeli demonstrators, but under the circumstances, one cannot blame the soldiers for having made a mistake.” The soldiers, he said, “did not believe they were dealing with Israelis.” 22

As already noted, these problems are not new. Those Israeli soldiers who wrongfully kill or injure Palestinian civilians in the occupied West Bank and Gaza Strip have enjoyed effective impunity for decades.23 Israeli public officials, human rights groups, journalists, and others have deplored this impunity at least since the formation of the Karp Commission in 1982.24 The Karp Commission concluded, in May of that year, “The key lies not in the technical monitoring of the investigations, nor in criteria for investigative techniques, nor in the legal angle — but rather a radical reform of the basic concept of the rule of law in its broadest and most profound sense.”25

Pressure for a proper investigation rises every time a high-profile killing takes place, but Israeli authorities have taken no serious steps to improve the accountability of the armed forces, create an independent investigation system, or reform the military justice system.

There is no reason this state of affairs should persist. Other armies have learned lessons from their own failures of accountability, by improving investigation procedures in these cases, transferring military cases to civilian jurisdiction, and revising their military justice laws. The IDF and its civilian authorities must do more to ensure that the IDF fulfills its duty to investigate impartially all suspicious civilian deaths and credible allegations of wrongdoing. It owes this duty to the civilians of the West Bank and Gaza Strip, whose lives depend on it. It owes this duty to its soldiers and officers, to protect them against unwarranted allegations of war crimes. And it owes this duty to the Israeli public, which has the right to expect a transparent, efficient, and accountable military that abides by international norms that the state of Israel has pledged to uphold.

About This Report

This report examines the Israeli army’s failure to investigate adequately allegations of wrongdoing by Israeli soldiers since the outbreak of clashes in September 2000. It addresses three major questions. First, it examines how the army’s policy on investigations has operated since September 2000, and the obstacles to accountability it has created. Second, it assesses the impact of “operational investigations,” in which allegations of wrongdoing are “investigated” by the colleagues of the alleged perpetrator. These debriefings may be appropriate for learning operational lessons, but they in no way constitute impartial investigations into suspicious incidents. Third, it looks at how the Military Police investigations opened since September 2000 have been conducted — and what can be done to improve them.

This report is based on field research conducted from April to August 2003, previous Human Rights Watch fieldwork and reports, and additional research and interviews in 2005. It is based on more than 150 interviews with victims, families, military officials, nongovernmental organizations, and intergovernmental groups. It also draws from meetings and written correspondence with the IDF from 2001 to 2005, as well as public statements and legal submissions by government officials. Human Rights Watch particularly wishes to thank the staff of the International Organizations Unit of the Office of the IDF Spokesperson, who were considerably more responsive to our requests for meetings in 2003-2004 than in previous years.

During the course of its fieldwork in 2003, Human Rights Watch researched some thirty cases of alleged wrongdoing by members of the IDF. The majority of these cases were incidents that had taken place at least six to twelve months earlier, allowing sufficient time for an investigation to take place. Others took place during Human Rights Watch’s period of fieldwork. Human Rights Watch in February 2005 requested from the IDF any update in the status of each case, and as of early June 2005 had received no response.

In selecting cases for examination, Human Rights Watch concentrated on those cases of alleged wrongdoing that the IDF had publicly committed to investigate. In the great majority of these cases, the killings very clearly happened outside a situation of armed conflict. Human Rights Watch also followed up cases that it had itself presented earlier to the IDF for investigation. For the sake of comparison, Human Rights Watch also documented a number of cases of alleged wrongdoing that appeared to merit investigation, but no mention of investigation had been made. Reasons of space do not allow us to discuss in the report every troubling case.

[21] “In our eyes, the defendants are not deviants and are no different from thousands of soldiers who belong to their brigade... Their failure is the bitter fruit of the lack of observation of norms which apparently received legitimization and even encouragement by commanders. Even, regretfully, by high-ranking commanders. . . ,” Military Court opinion in the Givati trial, May 25, 1989. For an account of the Givati incident, see John Conroy, Unspeakable Acts, Ordinary People: The Dynamics of Torture (New York: Knopf, 2000), pp. 140-42.

[22] “Israel will Not Punish Soldiers over Shooting of Peace Demonstrator,” Agence France-Presse, January 6, 2004. The army later stated that the soldiers would not be disciplined because they had operated according to the rules of engagement, and one “senior military officer” told the press that it was not possible to equip troops with riot control equipment to deal with such incidents. See, Amos Harel and Tsahar Rotem “IDF Won’t Act Against Soldires Who Shot Protester,” Ha’aretz, January 6, 2004. One of the recommendations to Israel of the Sharm el-Sheikh Fact-Finding Committee, appointed by President Clinton and headed by former Senator George Mitchell, was to “ensure that the IDF adopt and enforce policies and procedures encouraging non-lethal responses to unarmed demonstrators, with a view to minimizing casualties and friction between the two communities.”

[23] Complaints against Israeli police, in contrast to those against the IDF, are handled by the department of investigation of police misconduct within the Ministry of Justice. Although police investigations suffer from ongoing problems, they have complied to a greater extent with international standards of fairness than those of the IDF.

[24] The Karp Commission was formed in response to a petition by fourteen Israeli law professors protesting the practices of Israeli settlers towards Palestinians in the West Bank. The commission was created by the Israeli attorney general and headed by his deputy, Judith Karp.

[25] Deputy Attorney General Judith Karp, Investigations of Suspicions Against Israelis in Judea and Samaria,: “Conclusions” (Government Press Office, May 25, 1982); released in edited form by Government Press office, Jerusalem, February 7, 1984. Known as the Karp Commission Report, an English-language translation was published as The Karp Report (Washington D.C.: Institute for Palestinian Studies, 1984).

| <<previous | index | next>> | June 2005 |