<<previous | index | next>>

VI. Conditions of Detention

They’ve committed crimes, okay. There should be help in the first instance, not throwing them in prison, not keeping them without being able to call their family. Somebody won’t straighten out in Padre Severino. The problem of marijuana, he [my son] picked up this habit inside. My son returned full of rage, of aggression, without any help.86

—Neusa M., whose son was in detention in 2004, interviewed in Rio de Janeiro, May 12, 2005.

In December 2004, when Human Rights Watch released its last report on juvenile detention in Rio de Janeiro, DEGASE director general Sérgio Novo told the press that he was “indignant” at our findings, which he described as “an injustice.” “They show a reality that is completely different from what we have today,” he declared to the Folha de S. Paulo newspaper.87 In fact, Human Rights Watch’s six-month review of Rio de Janeiro’s juvenile detention centers found that little has changed. If anything, detention conditions have worsened in several important respects.

The Educandário Santo Expedito is a case in point. It held 181 youths the week we visited in July 2003, 9 percent over its official capacity of 166. When we returned in May 2005, it held 207 youths, 24 percent more than it was designed for. On both occasions, we found that its true capacity was closer to 90—entire cellblocks destroyed in a November 2002 fire were not repaired until late 2004, and they are not currently used to house youths. The only notable improvements were the fresh coats of paint on the doors leading into each cellblock, which are now yellow instead of a peeling, dingy blue, and on the basketball court.

Overcrowding is the rule at most other detention centers as well. CAI-Baixada is at 179 percent of its capacity. Padre Severino is at 175 percent of capacity. Santos Dumont was not filled to capacity when we visited, but officials there told us that it periodically reaches 150 percent. Only João Luiz Alves, the closest thing Rio de Janeiro has to an adequate detention center, consistently holds fewer youths than it is designed for.

Squalor continues to be the order of the day. Cells are filthy, dark, and infested with vermin. At times, youths wear a single change of clothing for a week at a time. Youths do not always have access to soap and toothpaste, particularly in Padre Severino. Shortages of mattresses and bedding are common, and extreme levels of overcrowding mean that youths must often share beds. Unsurprisingly, scabies and other contagious diseases thrive in such conditions.

All of Rio de Janeiro’s detention centers are dilapidated and badly in need of repair, but we heard particular complaints about Santos Dumont, the girl’s detention center. When we visited the center, a guard commented, “What’s bad here are the rooms. Look. Everything is wet, moldy. Really they have to renovate everything here.”88 André Hespanhol, a lawyer with the nongovernmental organization Projeto Legal, agreed with the guard’s assessment, saying of the rooms, “They’re horrible. And it would take just a little bit to improve them. About 20,000 reais [U.S.$8,300] would be sufficient to redo everything there.”89

The quality and amount of food was a problem in most centers, with the strongest complaints coming from those in Santo Expedito. “Here the food is very bad. Spoiled meat.” Marcos G. had recently found white bugs in his food, he told us.90

Youths in every facility we visited told us that they were now attending classes, but that was not the case for much of 2005. As described in the previous section, classes were suspended starting in January in CAI-Baixada, Padre Severino, and Santo Expedito due to an acute shortage of guards and other personnel. Schooling resumed in Santo Expedito only one week before our visit, according to the public defender’s office.91

The staffing shortage has also meant a sharp reduction in recreation and other activities, meaning that youths now spend much of their time locked in their cells. Marcos G. reported that when he was held in Padre Severino, “We only used the field once in a while. . . . There we stayed locked up the whole time. The place was stinking like hell. There was nothing to do.”92 The same is true in CAI-Baixada, according to a suit brought by the public defender’s office in March 2005 over conditions in that center.93

Juvenile detention is intended to serve a rehabilitative purpose. In Rio de Janeiro, it fails not only to achieve that end but also to provide basic conditions of dignity and humanity. “These boys deserve punishment because they made mistakes,” said Silvia R., the mother of a seventeen-year-old held in Padre Severino until May 2005. “But they shouldn’t be treated like animals.”94

Overcrowding

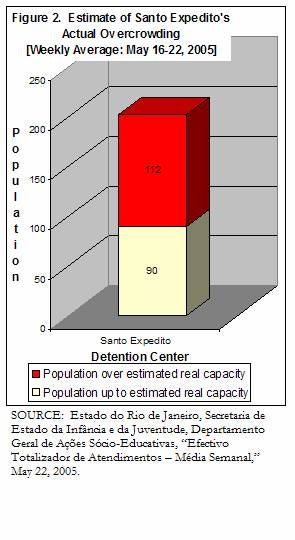

Overcrowding is particularly serious in CAI-Baixada, Padre Severino, and Santo Expedito, as the chart below show. CAI-Baixada and Padre Severino each held in excess of 175 percent of their rated capacity during the week of May 16, 2005, DEGASE reported. Santo Expedito was at 124 percent of its official capacity that week.95

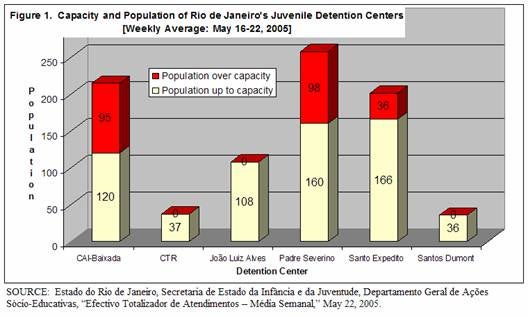

The situation is even more serious in Santo Expedito than it appears from these data. Its official capacity of 166 does not reflect the fact that many of its cellblocks have been converted to other uses. In our December 2004 report, we noted that several buildings had been largely destroyed in a November 2002 fire; these buildings had not been repaired when we visited in July 2003. When we returned to the center in May 2005, we expected to find that these areas had been renovated, easing the pressure on the other cellblocks. We found that the buildings had been repaired but are now used as a recycling center, meaning that all youths continue to be crowded into cellblocks in a single building. Based on our discussions with detention center staff and our inspection of the facility, we estimate the true capacity of Santo Expedito to be 90 rather than 166. With 207 youths in detention on the day of our visit, it held 230 percent of its estimated true capacity.

Overcrowding in Santo Expedito is such that youths must often share beds or sleep on the floor. Anderson F., a seventeen-year-old in Santo Expedito, explained, “Some stay on the ground, others on top [on the bed]. There one sleeps with his head one way and the other with his head the other way” so that they can fit on the bed.96

Santos Dumont held thirty-three girls when we visited in May 2005, seven under its official capacity of forty. Nevertheless, it is periodically overcrowded. One guard told us, “Now it’s okay because we have, what, twenty here, so we have a bed for everybody. It’s tough when there are fifty or sixty. Then we have to put two in a bed or even some on the floor.”97

Living Conditions

Rio de Janeiro’s detention centers fail to meet basic standards of health and hygiene. Detention centers report shortages of soap and toiletries; in some, youths wear a single change of clothing for up to a week before it is washed.

The youths we interviewed were particularly critical of the unhygienic conditions in Padre Severino. “The cells were all filthy” in Padre Severino, said André S., detained in Padre Severino in early 2004, when he was seventeen.98 Asked if the showers were clean in Padre Severino, seventeen-year-old Marcos G. responded, “No way. It was filth. It stunk like hell.”99 Reports of rats in Padre Severino were common among youths and parents we interviewed. “There were rats and centipedes,” André S. told us.100 “There were rats,” Marcos G. reported. “At night we would see lots of them running around.”101

The public defender’s office described CAI-Baixada in similar terms in a lawsuit filed in March 2005:

The infrastructure is precarious. The dormitories are dirty, fetid, and unhealthy, with leaks that have produced mold on the walls, making the place prone to respiratory illnesses and the dissemination of other infections, aggravated by the fact that the adolescents do not receive enough clothes to change them daily, as well as not having adequate facilities for their physiological needs and for daily bathing.102

In addition, youths in Padre Severino and other facilities often do not have bedding and mattresses; when they do, they are often old and worn. João T., seventeen, compared conditions at Padre Severino with those at João Luiz Alves. “There [in Padre Severino] . . . the mattresses were old. The foam was all worn down. Not like here [in João Luiz Alves]. Here they’re good. There you ended up with your back hurting.”103 André S. told us that he didn’t have a mattress during the forty-five days he spent in Padre Severino in early 2004.104 The public defender’s office has complained of a shortage of mattresses and bedding in CAI-Baixada, João Luiz Alves, and Santos Dumont as well.105

Those detained in Padre Severino told us that they did not regularly receive items such as toothpaste and soap. Marcos G. depended on his mother to bring him soap and toothpaste when he was in Padre Severino. “My mother brought it, but once they told her that toothpaste couldn’t come in,” he recounted.106 André S. told us that getting toothpaste there “was difficult. We got it every once in a while, like that, on our fingers.”107 Silvia R. brought her son soap when he was in Padre Severino, but she said that the guards also issued soap to the youths periodically.108

The situation in CAI-Baixada is similar, according to a suit filed by the public defender’s office in March 2005. Among other shortcomings, the suit charged that youths in CAI-Baixada “do not have the use of necessary items for personal cleanliness (soap, a place to bathe, towel, toothpaste, toothbrush, etc.),” lacked clean clothing, did not receive needed medications, and did not all have mattresses and bedding.109 In fact, the director of CAI-Baixada wrote to DEGASE’s central office in February 2005 saying, “We face difficulties in obtaining supplies of all kinds for the adolescents’ personal hygiene.”110

Clothing is changed once a week in Padre Severino and other detention centers. Silvia R. described what this meant in the close quarters of a detention center:

Their clothing takes on a revolting smell. They stay in those clothes. They sweat. They stay in dirty rooms, a lot of them in each room. They start to reek. So the guards call them, “You stinking bunch, you filth.”111

Some youths in CAI-Baixada go barefoot because the center does not have shoes or sandals for them, the public defender’s office reported, characterizing this situation as “not rare.”112 And when some of the parents we interviewed tried to bring their children clothing and other items, their children did not always receive what they brought. “They didn’t give him his clothes. They didn’t give him many things we brought,” said Gerson J., the father of an eighteen-year-old held in Santo Expedito until February 2005.113

As one consequence of the lack of hygienic conditions in Padre Severino and other detention centers, we heard reports of skin conditions likely caused by scabies and other parasitic diseases, which the public defender’s office describes as “constantly” present in Rio de Janeiro’s detention centers.114 “Many get itchy sores,” Silvia R. told us. “They stay there in those dirty cells, wet too.” She told us that she brought her son a special antibacterial soap so that he would not get the condition. 115 André S. gave a similar account. When he was in Padre Severino, he said, “There were many people with itches. They stayed separated from the rest. . . . I still have marks here on my feet, some little black bumps that don’t go away.”116 Marcos G., in Santo Expedito when we interviewed him in May 2005, reported that his hands itched. He pointed out tiny bumps on one hand. “Many people have them,” he said. He told us that he had not received treatment for the condition.117

Trash, standing water, and weeds

covered a basketball court in Santo Expedito when Human Rights Watch inspected

the center in July 2003.

(c) 2003 Stephen Hanmer/Human Rights

Watch.

In May 2005, Santo Expedito’s

basketball court showed some improvements: The backstop had been replaced and

the concrete painted. Trash still littered the edge of the court.

(c) 2005 Michael Bochenek/Human

Rights Watch.

[86] “Cometeram delito, tudo bem. Deveria ter um apoio na primeira instância, não botar preso, não ficar sem chamar a família. A pessoa não vai endireitar no Padre Severino. O problema de maconha, ele pegou esse habito lá dentro. O meu filho voltou cheio de ravia, de agressão sem nenhum apoio.”

[87] “Realidade da hoje é diferente da de 2003, diz diretor,” Folha de S. Paulo, December 8, 2004, p. C4.

[88] “O que é ruim aqui são os alojamentos. Olhe. Tudo molhado, cheiro de mofo. Realmente eles tem que refazer tudo isso ai.” Human Rights Watch interview with guard, Educandário Santos Dumont, May 12, 2005.

[89] “Lá o que é problemático mesmo são os alojamentos. São horriveis. E precisa de tanta pouca coisa para melhorar. Uns R$20,000 daria para refazer tudo aquilo.” Human Rights Watch telephone interview with André Hespanhol, lawyer, Projeto Legal, and president, Temporary Sócio-Educational System Monitoring Commission of the State Counsel for the Defense of the Child and Adolescent of the State of Rio de Janeiro, May 13, 2005.

[90] “Aqui a comida é muito ruim. Aquela carne estragada. Outro dia achei um bicho dentro da minha comida. . . . Tapuruca branco.” Human Rights Watch interview with Marcos G., Educandário Santo Expedito, May 23, 2005.

[91] Human Rights Watch interview with Simone Moreira de Souza, May 23, 2005.

[92] “Só usávamos a quadra de vez em quando. . . . Lá ficava o tempo todo preso. Fedendo pra caramba. Não tinha nada pra fazer” Human Rights Watch interview with Marcos G., Educandário Santo Expedito, May 23, 2005.

[93] See Ação Coletiva, No. 2005.001.028123-8, p. 3.

[94] “Os meninos merecem castigo porque tão errados. Mas também não tem que ser tratados como bicho.” Human Rights Watch interviw with Silvia R., Rio de Janeiro, May 20, 2005.

[95] True detention center capacity is difficult to estimate objectively, and capacity figures are notoriously easy to manipulate. See, e.g., Human Rights Watch, Behind Bars in Brazil (New York: Human Rights Watch, 1998),p. 24.

[96] “Fica alguns no chão, outros em cima [na cama]. Ai dorme um com a cabeça pra lá e outro com a cabeça pra ca.” Human Rights Watch interview with Anderson F., Educandário Santo Expedito, May 23, 2005.

[97] “Agora está okay porque têm, o quê, vinte aqui então tem cama pra todo mundo. Difícil é quando têm cinqüenta ou sessenta. Ai tem que botar duas numa cama ou até algumas no chão.” Human Rights Watch interview with guard, Educandário Santos Dumont, May 12, 2005.

[98] “Nas celas era tudo imundo.” Human Rights Watch interview with André S., Rio de Janeiro, May 20, 2005.

[99] “Nada. Uma sujeira. Fede pra caramba.” Human Rights Watch interview with Marcos G., Educandário Santo Expedito, May 23, 2005.

[100]. “Tinha rato, lacraia.” Human Rights Watch interview with André S., Rio de Janeiro, May 20, 2005.

[101] “Tinha rato. A noite a gente via muitos correndo por lá.” Human Rights Watch interview with Marcos G., Educandário Santo Expedito, May 23, 2005.

[102] “As instalações são precárias. Os alojamentos são sujos, fétidos e insalubres, com problemas de infiltração derivando mofo nas paredes, tornado o local propício a doenças respiratórias e disseminação de outras infecções, agravada pelo fato de os adolescentes não receberem roupas suficientes para a troca diária, além de não ter local adequado para as suas necessidades fisiológicas e para o banho diário.” Ação Coletiva, No. 2005.001.028123-8, p. 6.

[103] “Lá [em Padre Severino] também os colchões eram velhos. Não tinham espuma direito. Não como aqui [João Luiz Alves]. Aqui eles são bons. Lá ficava com as costas doendo.” Human Rights Watch interview with João T., Escola João Luiz Alves, May 12, 2005.

[104] “Não tinha nem colchão . . . todos os quarenta e cinco dias.” Human Rights Watch interview with André S., Rio de Janeiro, May 20, 2005.

[105] Ação Coletiva, No. 2005.001.028123-8, p. 6 (“Faltam roupa de cama e colchões.”); Ação Civil Pública com Pedido de Antecipação de Tutela, No. 2005.001.028046-5 (filed 1a. Vara de Fazenda Pública da Comarca da Capital, March 15, 2005), p. 3.

[106] “A minha mãe trazia mas uma vez disseram que a pasta de dente não podia entrar.” Human Rights Watch interview with Marcos G., Educandário Santo Expedito, May 23, 2005.

[107] “Era difícil. Era de vez em quando assim no dedo.” Human Rights Watch interview with André S., Rio de Janeiro, May 20, 2005.

[108] Human Rights Watch interview with Silvia R., Rio de Janeiro, May 20, 2005.

[109] “Os adolescentes não dispõem dos objetos necessários para o seu asseio pessoal (sabonete, local para banho, toalha, pasta de dente etc.), para o seu vestuário (roupas limpas, sandálias, agasalho etc.), para a sua saúde (medicamentos, médicos, tratamento odontológico etc.), além de faltar colchões, roupa de cama, gêneros alimentícios, material escolar, oficinas profissionalizante etc.” Ação Coletiva, No. 2005.001.028123-8, p. 2.

[110] “Estamos em difficultades em obter materiais de higiene pessoal para os adolescentes, sem exceção . . . .” Letter from Ivamor Lima Silva, director, CAI-Belford Roxo, to Public Defender’s Office, Ofício CI/DEGASE/CAI BR No. 066/05, February 25, 2005, quoted in Ação Coletiva, No. 2005.001.028123-8, p. 5.

[111] “A roupa fica com um cheiro enjoativo. Eles ficam nessas roupas. Suam. Ficam em quatros sujos, muitos em cada sala. Ai eles ficam fedidos. Ai os agentes chamam, ‘O seus fedidos, seus imundos.’” Human Rights Watch interview with Silvia R., Rio de Janeiro, May 20, 2005.

[112] “Não raro, os adolescentes andam descalçados pela Unidade, posto que o número de calçados é insuficiente para o quantitativo de internos.” Ação Coletiva, No. 2005.001.028123-8, p. 6.

[113] “A roupa dele não entregaram. Muitas coisas que nos levamos eles não entregaram.” Human Rights Watch interview with Gerson J., Rio de Janeiro, May 20, 2005.

[114] “[E]m virtude da precariedade no fornecimento destes materiais, muitas vezes os adolescentes têm que dividir o mesmo material (sabonete, toalha, roupa de cama . . .) entre si, o que facilita a disseminação de doenças, principalmente a escabiose (sarna), que vem sendo constante nas Unidades de Internação.” Ação Coletiva, No. 2005.001.028123-8, p. 5.

[115] “Muitos pegam uma coceira danada. Ficam lá naquelas cela sujas, molhadas também.” Human Rights Watch interview with Silvia R., Rio de Janeiro, May 20, 2005.

[116] Tinha muita gente com coceira. Ficavam separados de todos. É porque tinha muito cachorros na quadra. Dai a gente sentava lá e pegava as coisas. Ainda tenho marcas aqui no meu pé, umas bolinhas pretas que não sairam.” Human Rights Watch interview with André S., Rio de Janeiro, May 20, 2005.

[117] Human Rights Watch interview with Marcos G., Educandário Santo Expedito, May 23, 2005.

| <<previous | index | next>> | June 2005 |