<<previous | index | next>>

II. Historical Background

Before it all started, the city was very much intact. It was surprising to me that it was so intact. Afterwards, of course, it was all destroyed.

—Jeremy Bowen, correspondent with the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), discussing fighting in Kabul between mujahedin factions after the fall of the Soviet-backed government in 1992.5

The history of modern armed conflict in Afghanistan began in April 1978, when Soviet-backed Afghan communists took control of the government in a coup, overthrowing the president of Afghanistan, Muhammad Daoud Khan, the cousin of Afghanistan’s former king, Zahir Shah, who was earlier overthrown in a bloodless coup by Daoud in 1973.6

The “Saur Revolution” (named for the Afghan calendar month when it occurred) went badly from the start. The communists who seized power in Kabul consisted of two opposed political parties—Khalq and Parcham.7 Each had little popular support, especially outside of Kabul and other main cities, and many segments of the country’s army and police opposed the coup.

The new government soon came to be dominated by a ruthless Khalq leader, Hafizullah Amin, who sought to create a communist economy in Afghanistan virtually overnight through purges, arrests, and terror. An insurgency was launched against the new regime, and in 1979, the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan to support the failing revolution and government, and installed a new leader from the Parcham party, Babrak Karmal.

But it was too late to put down the insurgency, which was already well-advanced and widespread. The rebels included former officers and troops of the Afghan military, members of exiled Islamist groups in Pakistan and Iran, and militias of numerous other disgruntled political groups. Loosely allied under a common theme—defenders of Islamic and Afghan values against Soviet occupation and ideology—these diverse parties enjoyed widespread support within and outside Afghanistan. They came to be known as “the mujahedin” and their battle as “the jihad.”

There was never any real unity between the mujahedin parties: some were openly hostile and occasionally fought battles with each other. But for most of the 1980s, the mujahedin groups—with the indispensable support of the United States, as well as the United Kingdom, Saudi Arabia, China, Iran, and Pakistan—fought an effective and often brutal guerrilla war against Soviet and Afghan national forces, attacking convoys, patrols, arms depots, government offices, airfields, and even civilian areas. The Soviet and Afghan national armies, for their part, regularly attacked or bombed mujahedin bases and villages, and harshly suppressed mujahedin organization and other anti-government activities. Much of the countryside became a battle zone in the 1980s.

The war had terrible effects on civilian life in Afghanistan. Both sides regularly committed serious human rights abuses and violations of international humanitarian law. The Soviets often targeted civilians or civilian infrastructure for military attack, and government forces under their control brutally suppressed the civilian population. Mujahedin forces also committed abuses and violations, targeting civilians for attack and using illegal methods of warfare.8 It is estimated that well over one million people were killed by conflict and violence during the Soviet occupation and over seven million people were displaced from their homes.9

Militarily and financially exhausted, and spurred on by perestroika, the Soviet Union finally withdrew from Afghanistan in 1989. It continued to support the Kabul government, which was now headed by Najibullah, a former head of Afghanistan’s Soviet-trained intelligence service, KHAD.10

The Afghan nation, however, had been shattered by communist rule and Soviet occupation. By 1989 approximately one-fifth of its population had fled abroad and much of Afghanistan’s rural infrastructure was destroyed. The cohesion of the Afghan nation and concepts of national identity were severely compromised, and there were deep social, ethnic, religious, and political divisions within and between the existing regime and mujahedin parties.

The conflict also filled the country with weapons. Afghanistan was not particularly militarized in the late 1970s, when the communist coup took place. The mujahedin in 1979 were severely under-equipped to fight a standing Soviet army, and the communist Afghan government was severely disorganized and poorly outfitted. All that changed. In the 1980’s, the United States and Saudi Arabia, and to a lesser extent Iran and China, allocated an estimated $6 to $12 billion dollars (U.S.) in military aid to mujahedin groups, while the Soviet Union sent approximately $36 to $48 billion of military aid into the country to support the government.11 (Pakistan, where some of the mujahedin parties set up exile headquarters, arranged large military training programs for the mujahedin and controlled how much of the Saudi and U.S. assistance was delivered.) During the 1980’s, Afghanistan likely received more light weapons than any other country in the world, and by 1992 it was estimated that there were more light weapons in Afghanistan than in India and Pakistan combined.12

Despite the Soviet withdrawal, through 1989-1991 battles between mujahedin and government forces continued. The mujahedin parties made few attempts at compromise, and Najibullah stubbornly refused to step down as his power eroded. The mujahedin—deeply divided with historical rivalries and religious, ethnic, and linguistic differences—also increasingly began to fight among themselves as they took more territory from the government. The U.S. government began to turn its attention away from Afghanistan, even as it, along with Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and Iran, continued to arm mujahedin forces. The Soviet Union continued its support for Najibullah. There were few international efforts to mediate to prevent the increasing fragmentation of armed groups in Afghanistan. Peacemaking efforts were mostly put in the hands of the U.N. Secretary-General’s office, which lacked the political clout to force the parties to compromise. The war—increasingly a multi-party civil war—went on.

A Soviet soldier in

a military parade

in Kabul marking the start of the pullout of Soviet forces

from Afghanistan in 1988.

© 1988 Robert Nickelsberg

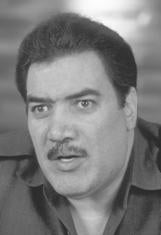

President Najibullah, the last

Soviet-backed leader of Afghanistan. Formerly the head of Afghanistan’s Soviet-trained intelligence agency, KHAD, Najibullah retained power for four

years after the Soviet withdrawal. He agreed to resign in March 1992,

three months after the Soviet Union cut off assistance to his government.

He was killed by the Taliban in 1996. © 1990 Robert Nickelsberg

The disunity among the mujahedin—a key obstacle to peace-making efforts—was aggravated throughout this period by the continuing policy of the United States, Pakistan, and Saudi Arabia to give a disproportionate amount of military assistance to one particular mujahedin party: the Hezb-e Islami of Gulbuddin Hekmatyar.13 Through the 1980’s, Hekmatyar received the majority of assistance from these countries, and in 1991, the CIA (with Pakistani support) was still channeling most U.S. assistance through Hekmatyar—including large shipments of Soviet weapons and tanks the United States captured in Iraq during the first Gulf War (weapons used by Hekmatyar later to attack Kabul in 1992-1996).14 Unity among the different mujahedin groups was made especially difficult because of Hekmatyar’s constant demands for a disproportionate share of power in a post-Najibullah government, and the resentment and hatred toward Hekmatyar in other parties, who believed they had fought against Soviet forces just as decisively as Hezb-e Islami (if not more) and with less assistance.15 As the Soviet Union collapsed, there were increasing signs that the war it started in Afghanistan would last for a long time, even as the regime it supported collapsed.

* * * * * *

In September 1991, the Soviet Union and the United States agreed to a reciprocal cut-off in funding and assistance to Najibullah’s government and mujahedin forces respectively, starting January 1, 1992. At this point, it was clear to all parties that the government’s days were numbered. Whole sections of Afghanistan, including areas on the Pakistan border, were already in the hands of mujahedin factions, and without Soviet support the Najibullah government’s grip on Kabul was loosening.16

Mujahedin leaders, however, were still in disagreement about a post-Najibullah power-sharing plan. Through the spring of 1992, the United Nations, along with Saudi and Pakistani officials, worked with major Sunni and Shi’a parties to fashion an agreement.

On March 18, 1992, under strong pressure from the United States and Pakistan (via the United Nations), Najibullah agreed to resign as head of state as soon as a transitional authority was formed. He appeared on Afghan television to make the announcement.17 The next day, the government’s main military leader in the north, General Rashid Dostum, defected from the government and agreed to form a coalition force with commanders from the Wahdat and Jamiat forces. This unified force then took control of the northern city of Mazar-e Sharif and surrounding areas.18 With the border of Pakistan already held by other mujahedin forces, Kabul was now effectively surrounded.

As the Afghan New Year of 1371 began at the spring equinox—March 21, 1992—it was clear that the communist era was over in Afghanistan, but it was unclear whether 1371 would be peaceful. The government in Kabul stood, as the U.N. continued to try to work out a post-Najibullah power sharing plan.

On April 10, U.N. Secretary-General Boutros Boutros-Ghali presented a plan to the mujahedin parties, which they in turn approved, to form a “pre-transition council composed of impartial personalities” to accept formal sovereignty from Najibullah and then convene a shura (traditional Afghan council) in Kabul to choose an interim government.19 The plan was for the U.N. to fly the council—mostly elder exiled community and tribal leaders—into Kabul the night of April 15 and then fly Najibullah out of the country to exile. Mujahedin parties would remain outside the city throughout.

On the ground, however, events were already in flux. Massoud’s forces seized control of the Bagram airbase north of Kabul and much of the Shomali plain north of the capital, along with forces working for Dostum, who had now formed a new political-military party: Junbish-e Melli-ye Islami (the National Islamic Movement). Both forces were literally just outside Kabul. Hekmatyar, meanwhile, had moved Hezb-e Islami forces just to the south of the city.

Government forces en masse were beginning to defect to the different mujahedin parties, offering assistance to each of the parties entering Kabul. Hekmatyar and Massoud had each worked to cultivate defectors among government security forces, and Dostum, as a former government official, already had links to officials in Kabul.

The dynamics of these defections were heavily influenced by ethnic identity. Most Pashtun officials and police officers in the interior ministry (mostly from the Khalq faction) now sought to build alliances with Hekmatyar, while Tajik officers in the military and government (mostly Parcham) were defecting to Massoud. Turkmen and Uzbek officials were siding with Dostum.

On April 15, as Najibullah prepared to resign, some mujahedin parties balked at the U.N. arrangement, undermining the agreement. That night, the chief U.N. mediator, Benon Sevan, flew alone to Kabul to pick up Najibullah. But as Najibullah approached the airport, his car was blocked by militia forces. Najibullah backtracked into the city and took refuge in the Kabul U.N. compound (where he was to remain for the next four years, until the Taliban took control and killed him).20 Sevan flew back to Pakistan to continue negotiations. Meanwhile, Pashtun government officials in the interior and defense ministries were starting to allow forces from Hekmatyar’s Hezb-e Islami party into the city, to prepare for his entrance into the city. Massoud and Dostum remained north of the city while mujahedin representatives continued to work on a power-sharing agreement in Peshawar.

On April 24, as Hekmatyar was about to seize control of the city, Massoud and Dostum’s forces entered Kabul, taking control of most government ministries. Jamiat attacked Hezb-e Islami forces occupying the interior ministry and Presidential Palace, pushing Hezb-e Islami south and out of the city. There was shelling and street-to-street fighting through April 25 and 26.

On April 26, the mujahedin leaders still in Pakistan announced a new power-sharing agreement, the Peshawar Accords. The agreement provided for Sibghatullah Mujaddidi, a relatively independent religious leader with a small political party, to become acting president of Afghanistan for two months, followed by Jamiat’s political leader, Burhanuddin Rabbani, for another four months. After Rabbani’s term, a shura was to choose an interim government to rule the country for eighteen more months, after which elections would be held. According to the agreement, Massoud was to act as Afghanistan’s interim minister of defense. Hekmatyar was entirely sidelined from the government.

By April 27, Hekmatyar’s main forces had been pushed to the south of Kabul, but remained within artillery range. The city was breached, however, and all the mujahedin parties, including Ittihad, Wahdat, and Harakat, now entered the city. Thousands of former government soldiers and police now switched their allegiances to the militias or to the Massoud-led forces in Mujaddidi’s new government. Others just deserted. Some of the Pashtun officials who had earlier sided with Hezb-e Islami now left Kabul and allied with Hekmatyar to the south; some others joined the predominately Pashtun Ittihad party.21 Kabul had suffered a few days of fighting, but was generally intact. The Soviet-backed government had fallen, with minimal damage to the city.

Jamiat commander Ahmed Shah Massoud on April 18, 1992, speaking to

commanders on a field telephone just north of Kabul, soon after meeting with

Junbish commander General Rashid Dostum. Jamiat and Junbish forces moved

into Kabul six days later, while Hezb-e Islami forces entered the city from the

south.

© 1992 Robert Nickelsberg

Defecting soldiers from the

Soviet-backed government greet Jamiat mujahedin on the Jalalabad road, east of Kabul, April 25, 1992. After Najibullah’s resignation, government forces put up no

resistance to the mujahedin and Kabul was captured without fighting. The

subsequent violence within the city was primarily due to rivalries among

mujahedin factions.

© 1992 Robert Nickelsberg

Junbish troops in a

street battle with Hezb-e Islami forces in eastern Kabul, April 25, 1992.

© 1992 Robert

Nickelsberg

Junbish troops carrying rocket

propelled grenades, south Kabul, April 25, 1992.

© 1992 Robert

Nickelsberg

A civilian, wounded

in crossfire between Junbish and Hezb-e Islami troops, south Kabul, April 27,

1992.

© 1992 Robert

Nickelsberg

A boy wounded during

street battles in Kabul in May 1992, treated at the Karte Seh hospital in west Kabul, May 1992. Tens of thousands of civilians were killed or injured in fighting

in Kabul in 1992-1993.

© 1992 Robert Nickelsberg

[5] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Jeremy Bowen, correspondent with the British Broadcasting Corporation in Kabul in 1992, April 12, 2004.

[6] For information about the periods discussed in this section, see Barnett R. Rubin, The Fragmentation of Afghanistan: State Formation and Collapse in the International System, Second Edition (New Haven: Yale, 2002) and Rubin, The Search for Peace in Afghanistan; Olivier Roy, Islam and Resistance in Afghanistan (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986); and Steve Coll, Ghost Wars: The Secret History of the CIA, Afghanistan, and Bin Laden, from the Soviet Invasion to September 10, 2001 (New York: Penguin, 2004). See also Mohammad Nabi Azimi, Ordu va Siyasat Dar Seh Daheh Akheer-e Afghanistan (“Army and Politics in the Last Three Decades in Afghanistan”) (Peshawar: Marka-e Nashrati Mayvand, 1998); Sangar, Neem Negahi Bar E’telafhay-e Tanzimi dar Afghanistan; and Mir Agha Haghjoo, Afghanistan va Modakhelat-e Khareji (“Afghanistan and Foreign Interferences”) (Tehran: Entesharat Majlesi, 2001).

[7] The names of the two parties derived from their respective newspapers, Khalq (the masses) and Parcham (the flag). At the time of the 1978 coup, Khalq and Parcham were ostensibly united within the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA).

[8] For more information on human rights abuses and violations of international humanitarian law during the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan, see Human Rights Watch, “Tears, Blood, and Cries: Human Rights in Afghanistan Since the Invasion, 1979 to 1984,” A Helsinki Watch and Asia Watch Report, 1984; Human Rights Watch, “To Die in Afghanistan,” A Helsinki Watch and Asia Watch Report, 1985; Human Rights Watch, “To Win the Children,” A Helsinki Watch and Asia Watch Report, 1986; Human Rights Watch, “By All Parties to the Conflict,” A Helsinki Watch and Asia Watch Report, 1988. See also, Jeri Laber and Barnett R. Rubin, A Nation is Dying (Illinois: Northwestern University Press, 1988); Amnesty International, Afghanistan: Torture of Political Prisoners (London: Amnesty International Publications, 1986).

[9] Rubin, The Fragmentation of Afghanistan, p. 1.

[10] KHAD stands for Khademat-e Ettela’at-e Dawlati (“State Intelligence Service”).

[11] See Larry P. Goodson, Afghanistan’s Endless War: State Failure, Regional Politics, and the Rise of the Taliban (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2001), pp. 63 and 99; Coll, Ghost Wars, pp. 65-66, 151, 190, and 239. See also generally, George Crile, Charlie Wilson’s War: The Extraordinary Story of the Largest Convert Operation in History (New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2003); Human Rights Watch, Crisis of Impunity: The Role of Pakistan, Russia, and Iran in Fueling the Civil War, A Human Rights Watch Short Report, July 2001, vol. 13, no. 3 (C); Haghjoo, Modakhelat-e Khareji, pp. 106-160; and Mohammed Nabi Azimi, Ordu va Siyasat, pp. 225-325.

[12] See Rubin, The Fragmentation of Afghanistan, p. 196.

[13] See Haghjoo, Modakhelat-e Khareji, pp. 168-189; for a broad discussion of the disunity among mujahedin groups, see Mohammed Zaher Azimi, Afghanistan va Reeshey-e Dardha 1371-1377 (“Afghanistan and the Roots of the Misery 1992-1998”) (Peshawar: Markaz-e Nashrati Mayvand, 1998).

[14] See Coll, Ghost Wars, p. 226; and Steve Coll, “Afghan Rebels Said to Use Iraqi Tanks,” The Washington Post, October 1, 1991.

[15] See Rubin, The Fragmentation of Afghanistan, pp. 196-201; Saikal, “The Rabbani Government, 1992-1996” in Fundamentalism Reborn, pp. 30-31.

[16] For more information on events in this specific period, see Rubin, The Fragmentation of Afghanistan, pp. 266-274, and The Search for Peace in Afghanistan, pp. 127-135; Saikal, “The Rabbani Government, 1992-1996” in Fundamentalism Reborn; M. Hassan Kakar, Afghanistan: The Soviet Invasion and Afghan Response, 1979-1982 (Epilogue) (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1995).

[17] See Rubin, The Search for Peace in Afghanistan, p. 128.

[18] For a detailed discussion of the political background and details of the fall of Mazar-e Sharif, see Assadollah Wolwalji, Safehat-e Shomal-e Afghanistan dar Fasseleh-e Beyn-e Tarh va Tahaghghogh-e Barnamey-e Khorooj-e Artesh-e Sorkh az een Keshvar (“What Occurred in the Northern Plains of Afghanistan During the Planning and Implementation of the Withdrawal of the Red Army from This Country”) (Unknown, likely Peshawar: Edareh-e Nashrati Golestan, 2001); see also Mohammed Nabi Azimi, Ordu va Siyasat, pp. 512-525 (regarding the conduct and views of the Afghan national armed forces in the north during this period).

[19] See U.N. Department of Public Information, “Statement of the Secretary-General on Afghanistan,” April 10, 1992.

[20] Mohammad Nabi Azimi, Ordu va Siyasat, pp. 557-563. Azimi, who was a high level officer in the Afghan Army in this period, claims to have personally witnessed some of the discussions between Najibullah and Sevan preceding the fall of Kabul, and suggests that Najibullah did not discuss the idea of departing from Kabul with his closest Afghan advisors and staff.

[21] For more information on ethnic identities and political alliances during this period, see Saikal, “The Rabbani Government, 1992-1996” in Fundamentalism Reborn, pp. 30-37, and Rubin, The Search for Peace in Afghanistan, pp. 128-129.

| <<previous | index | next>> | July 2005 |