“I tried to get in touch with my teacher who was teaching mathematics, chemistry, and physics. He said he would not be able to go to anyone’s home, but they could come to his house. As girls we feared going to his house, but I hear the boys have been going.”

— Taisha, 16, Kenya

A young girl playing in an informal settlement in Nairobi, Kenya, in July 2020. Many students wandered the streets of parts of Nairobi with nothing to do at home and schools closed due to the coronavirus pandemic. © Donwilson Odhiambo/SOPA Images/Sipa USA via AP Images

“I was not contacted by the school and I received no information about assignments to be completed by my sons… I cannot read or write, and I am very poor. I have always wanted a better life for my children… All I want is that my sons return to school… They deserve an education like all other kids.”

— Mother, Cambodia

“I have around five students that I haven’t heard anything from and who have not submitted anything, they went off the grid.”

— Grade 4 teacher, US

“It does not make me happy that my children are no longer going to school… Years don’t wait for them. They have already lost a lot… What will become of our uneducated children?”

— Mother, Democratic Republic of Congo

“I have students who have not appeared in these four months because they have no cellphone.”

— Teacher, Colombia

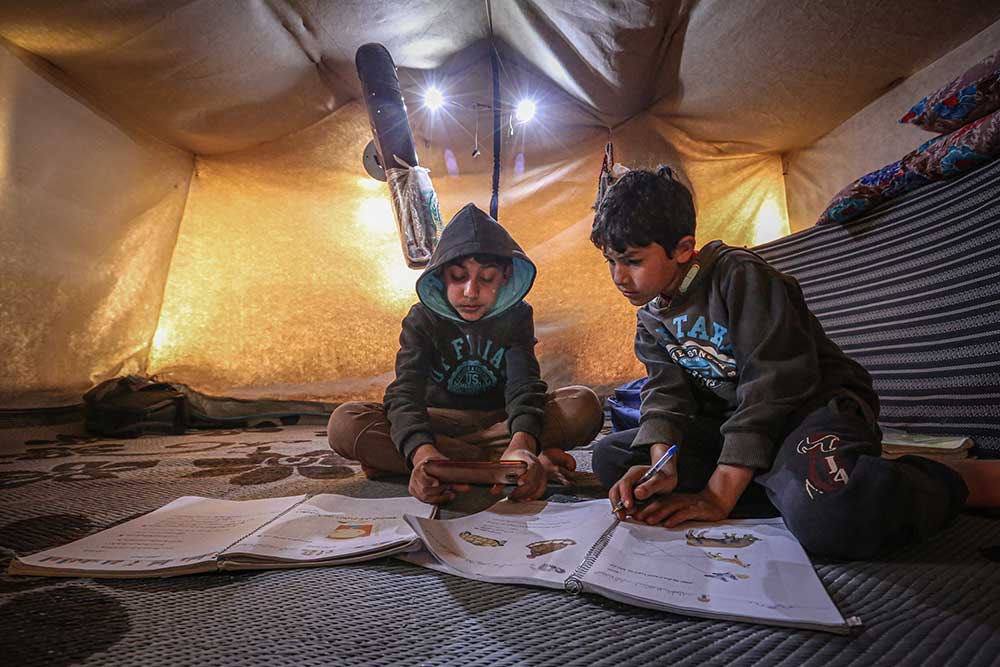

An 11-year-old Syrian girl, in a tent camp for displaced people in Idlib, Syria, teaches students who don't have smartphones to get distance education after schools are closed due to the coronavirus pandemic precautions on May 07, 2020. She can't continue her education due to giving classes to younger students. © Muhammed Said/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

“I received less knowledge, much less.”

— Miras, 13, Kazakhstan

“We just missed a whole bunch of material. The classes on Zoom really didn’t work… They were about 30 minutes long instead of 1.5 hours... Only three of my subjects offered Zoom classes.”

— Shaina, 18, Israel

“It’s certain that students will drop out of school. One of my students is already selling fish. She gave me two for free. She told me clearly that she cannot resume her studies next academic year.”

— Teacher, Central African Republic

“I was completely struggling for a whole two weeks, like crying every day. That was a big thing for me, starting to think life was meaningless.”

—Joseph, 16, South Africa

“Social life has always provided an escape from my worries and troubles, so it was scary to be just stuck with my own thoughts… At school, you’re with people that encourage a shared mindset of studying.”

—Tsering, 16, Belgium

Ma Seo-bin, a high school senior at an elite, expensive foreign language school near Seoul, South Korea, studies at her home in September 2020. “I felt I was trapped at the same place and I got lots of psychological stress,” said Ma. © Ahn Young-joon/AP Images

“It’s a little lonely… I’ve seen some of my classmates outside of school but this year I don’t have any of their [phone] numbers so it’s hard. I only follow two of my classmates on Instagram.”

—Josefina, 15, US

“The lockdown has been isolating with no friends and school structure. The group discussions that helped me learn and being able to go to the labs and conduct different experiments are other things I miss.”

—Kioko, 15, Kenya

“I am feeling a lot of stress… I have not been going to school for a long time now, so it feels like maybe I won’t ever go to school again.”

—Palki, 14, Bangladesh

“I’ve been very depressed. My mood was just not good, I was feeling overall just restless. I feel like a kid that’s getting cranky and has too much energy. I feel trapped.”

—Mia, 17, Canada

An elementary school student in Berlin, Germany, using a laptop to participate in online classes, in January 2021. © Annette Riedl/picture-alliance/dpa via AP Images

“It doesn’t do me any good to not go to school. I feel like something in me is missing.”

—Céleste, 15, Central African Republic

“I feel like the earth has just stopped.”

—Jae-kuk, 14, South Korea

“Many families have not been able to afford to continue to pay their Wi-Fi bill or have struggled to obtain internet capable devices... Having inconsistent access to educational materials that I provide makes it difficult for many of my students to keep up with the work.”

— Grade 6 and 8 teacher, US

“Primary school is supposed to be free in Cameroon, but it is not. There are always contributions… Usually when you don’t pay, the child is kicked out... In normal times, there are already difficulties.”

— Father, Cameroon

Keyla Vera shows Ariana Rodriguez basic math during classes set up by a 16-year-old student who teaches children in an improvised school she has set up under a tree for children who have been unable to attend virtual classes, in the low-income neighborhood Realidad de Dios, in Guayaquil, Ecuador, in July 2020. © Santiago Arcos /REUTERS

“I have been practically unemployed for the past four months and barely manage to pay the essential bills and for food… How can I pay for a computer, an internet bill, and a school bill while my income is zero? I have discontinued my daughter’s education.”

— Mother, Pakistan

“Neither I nor my husband can read or write, so we can’t help our daughters with school… Sometimes when the girls don’t understand something and the teacher can’t follow-up with them, we ask my sister, who went to school until 5th grade.”

— Mother, Morocco

“The closure disproportionately affects students whose families are essential workers or are working multiple jobs, or don’t have a lot of books at home. I was mailing some students paper and pencils.”

— Teacher, US

Mary Joyce Florendo, 8, a grade 3 student, is helped by her mother while working on her learning modules at their home in Manila, Philippines, as schools remain closed due to the coronavirus pandemic in November 2020. "It's important for me to finish my studies so I can help my parents in the future," said Mary Joyce. © Eloisa Lopez/REUTERS

“It is not easy to study in these conditions because we do not have enough space at home to do so and she is often disturbed by her brothers and family members.”

— Father, Democratic Republic of Congo

“Their teacher called me to tell me to buy a big phone [smartphone] for online teaching... I don’t have money to feed my family and I am struggling to make ends meet, how can I afford a phone and internet?”

— Mother, Nigeria

“There was no money at home and my mother was struggling so much…It is hard being hungry a whole day. Many times, my mum has to borrow food at the shop, but sometimes those people at the shop refuse.”

— George, 12, Uganda

“For a while I thought that I would go back when the school reopens but I don’t think that anymore… I enjoy driving and making money so what will I do going back to school now? Even if I do go back to school, it won’t be for long. Maybe I will complete my [10th grade exams] but I’m not sure.”

— Rehan, 14, Nepal

“I started working in order to survive by myself … My father was drinking a lot of alcohol and he would beat me whenever he returned. I got tired and ran. Then I started working because I needed many things. But I also wanted to save some money such that if schools re-opened, I would pay for myself school fees and buy other scholastic requirements like books [and] pens.”

— Andrew, 14, Uganda

The Delgado children work in their family's carpentry workshop, supervised by their father in El Alto, Bolivia, in August 2020, after the government cancelled the rest of the school year, which would have ended in December 2020, leaving almost three million children out of school © Juan Karita/AP Photo

“The schools did not give any type of assignments or work for them to continue at home, and the government did not follow up with any learning alternatives… My siblings are home not doing much. They help out by hawking fish which my father brings home from fishing after my mother has smoked them.”

— Older sister, Nigeria

“I started work to support my mum and earn enough money to pay for my senior high school education when the time comes.”

— Daniel, 17, Ghana

“We have done everything … to make children feel obliged to come to school, and here we are giving them an opportunity not to go... It’s been four months since we lost our relationship with most children.”

— Education NGO director, Madagascar

“These teenage kids could either sit behind a screen and do some school or they could go work on the farm and actually make some money. A lot chose to do that, and I can’t say I blame them.”

— Teacher, US

“His mom would leave at 5 in the morning, and he had to take care of his 3-year-old brother. It was clear that he didn’t have time to do [the assignments I sent]. He had to give his brother food, straighten the house, watch him in the street. My [12-year-old] student had stopped being a student to become a father to his brother.”

— Teacher, Mexico

A Nepali child waits for customers as he sells vegetables in the early morning during lockdown amid the COVID-19 pandemic in Kathmandu, Nepal on June 12, 2020. © Sunil Sharma/ZUMA Wire/Alamy Live News

“I’m in grade 12 and I’m about to try to have admission into university but I’ve fallen behind… Sometimes I couldn’t attend the online classes because my family owns small local shops and I had to help them. I only went to online classes for a week, then I had to help in the shop the rest of the time… I’m not sure if they would have asked me to work in the shop if I physically needed to be in school.”

— Jam, 17, Thailand

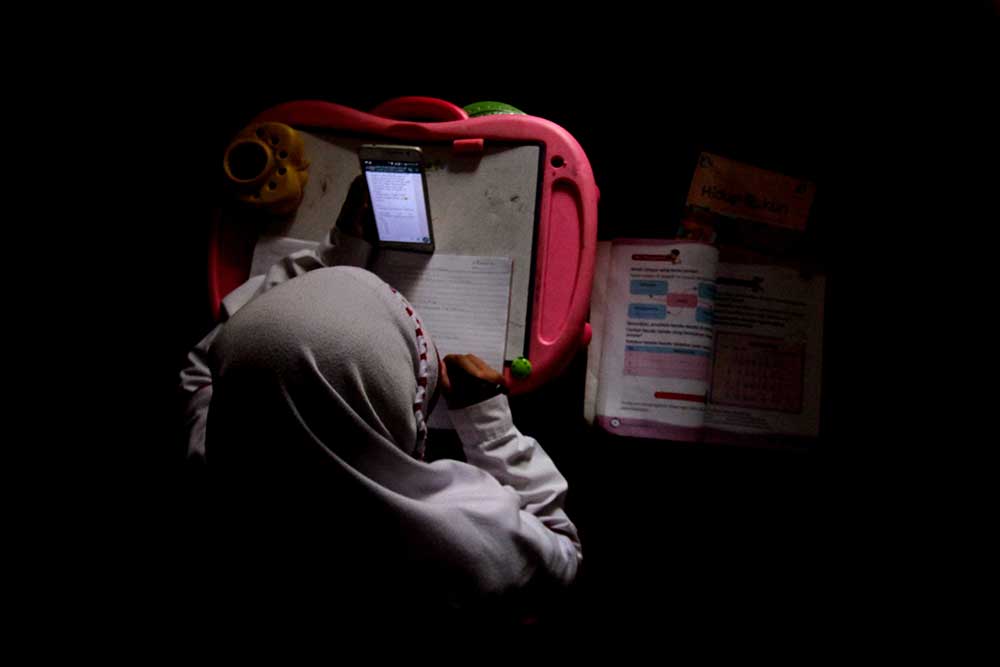

“These children… they often don’t have electricity―not even a lamp to study. So the [distance learning] classes benefit only children in…the big cities.”

— Teacher, Burkina Faso

Kila, 6, learns to draw by the faint light from an alley lamp in her neighbourhood in Jakarta, Indonesia, in November 2020. © Afriadi Hikmal/NurPhoto via AP Images

“My English teacher canceled class almost every time because she didn’t have electricity.”

— Sara, 14, Lebanon

“When we don’t have electricity, cell towers can’t transmit, so if we have a power outage, it means we don’t have electricity, and no communications.”

— Father, Venezuela

“I tell myself that I have to be ready if we are asked to resume [school] and take exams. [But I don’t have] internet access, nor can I access lessons through radio or television.”

— Marie, 16, Congo

Danka, Danixa, Violeta, and Axel draw while sitting on a discarded mattress in October 2020, in the community "El sueño de todos" (Everybody's dream), an informal settlement without potable water, drainage system, and electricity, where people have moved with their families after losing their jobs and income during the Covid pandemic, on the outskirts of Santiago, in Puente Alto, Chile. © Ivan Alvarado/REUTERS

“Nothing is happening from school. Everything is happening on TV. ... I am attending the classes on TV as much as possible, but when there is no electricity it is not possible… I’ve missed a lot of classes because the electricity was out.”

— Tasfin, 16, Bangladesh

“I hear there were lessons being offered on Warsan Radio, but I never tuned in because we do not have radio.”

— Taisha, 16, Kenya

“I am not aware of any TV programs and even if there are some, I don’t have a smartphone and don’t even have 24 hours of power to watch TV… I am not educated and don’t know how to teach him.”

— Mother, camp for internally displaced people, Iraq

“The government did something resembling courses on national television. But since some neighborhoods experience electricity shortages all seven days of the week, it's complicated. These courses only work for those who have access to electricity.”

— Father, Cameroon

“Sometimes the internet is very slow... I have a hard time downloading or streaming videos. There is a better plan for faster Wi-Fi. I discussed it with my mom, but she said we can’t afford it. Since the connection is not great, I have to prioritize some lessons over others… I missed some economy, philosophy, and English classes, because I had to make choices.”

— Hind, 18, Morocco

“I have the maximum plan for internet here, with 100 gigabytes of data [equal to about 200 hours of online video], and it is US$315 per month. I can start loading a web page and go sweep my floors while I wait for the page to load... I don’t believe that going to online learning could ever be an option unless the internet infrastructure is better.”

— School Principal, US

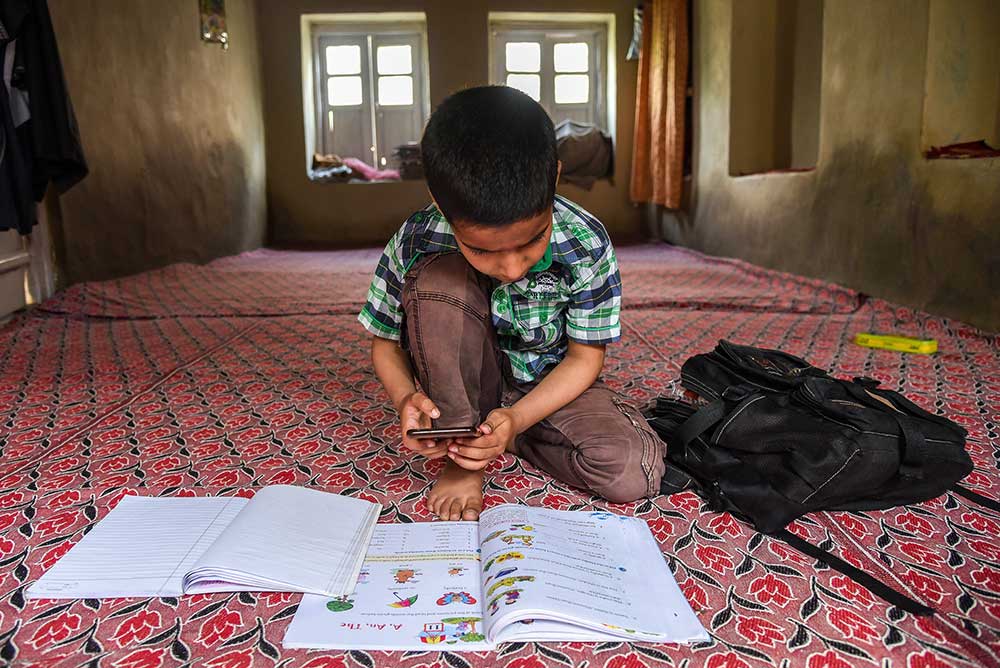

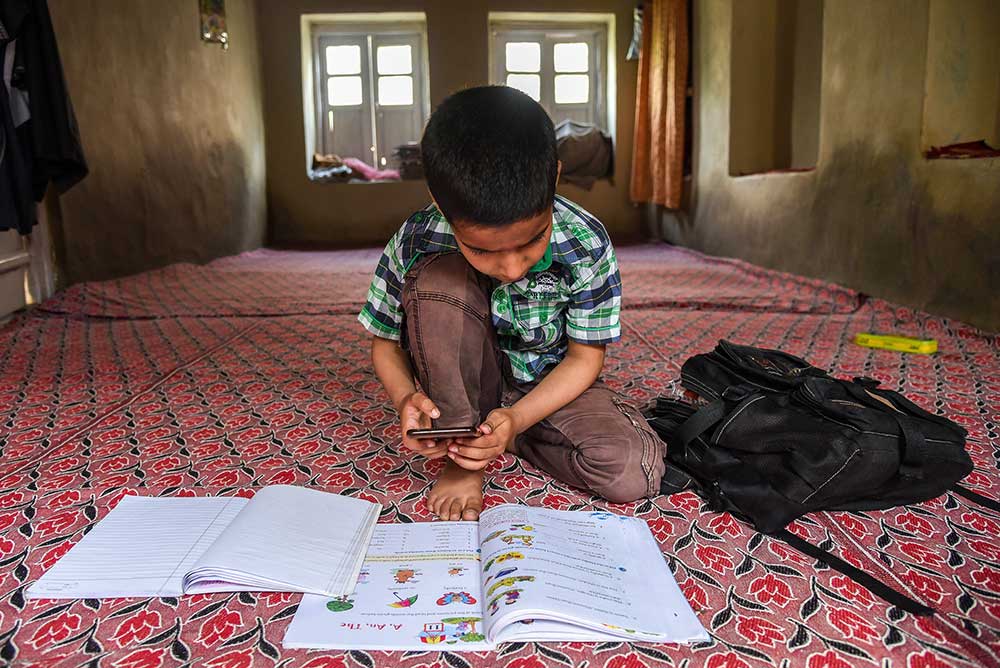

A Kashmiri student listens to the voice of his teacher during an online class in Kashmir, India, in May 2020. Students in Jammu and Kashmir were reeling under a double whammy of a government shutdown on high-speed mobile internet services and school shutdowns due to the Covid-19 pandemic. High-speed internet was finally restored after 18 months in February 2021. © Idrees Abbas/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images

“We had online classes through the phone… There were a lot of internet connectivity problems. I would miss what the teacher was saying, it was hard to understand the information that the teacher was trying to share. There was a direct impact on my grades―I didn’t do as well. We all find it hard to focus.”

— Lawan, 17, Thailand

“I have internet on my phone, but it is extremely poor because we live in a mountainous area… Teachers share videos, send links, but as I have poor internet connection on my phone, I cannot show them to my son.”

— Mother, Kyrgyzstan

“Me and my brother were using the same mobile phone. His classes would start later than mine, but there were times when they would coincide, and I would miss classes.”

— Gayane, 16, Armenia

VALLEJO, CA - APRIL 23: Michelle Burnett helps daughters Namarhianna, 9, and Alayjah, 12, with online classes at their home in Vallejo, California, in the United States, in April, 2020. Burnett was denied time off to pick up a laptop from Namarhianna's school so she could participate in distance learning. © Paul Chinn/The San Francisco Chronicle via Getty Images

“We have one computer in the family. Both my wife and I are working from home, so we need it. Now both children have classes, so they need to be on the computer. Two children with classes at the same time, so actually we need two computers. We are taking salary cuts, how can we afford to buy another laptop? So, one child is missing class.”

— Father, India

“I am a lower middle-class person and want to give my children the best education that I can afford, however I can’t afford multiple devices… My youngest daughter had to do classes on my wife’s phone and lost all interest in online classes… This is not fair. Anyone who can afford faster internet connections and multiple devices will have a significant advantage over my children.”

— Father, Pakistan

“I did not have internet prior to the school shutdown, and I was forced to adapt and try to get internet using 3G data on my phone… The connection is not reliable. I do not have unlimited access and I have to pay for the data that I use.”

— Teacher, Iraq

“Since I live in a [First Nations] reservation with no internet it’s been really difficult, I don’t have 24-hour access... It’s hard for me to even email teachers for help… I think my situation is harder than for ‘normal’ students, but I’m doing my best.”

— Annie, 15, Canada

“Students who cannot afford internet are simply deprived of the right to education.”

— Teacher, Bangladesh

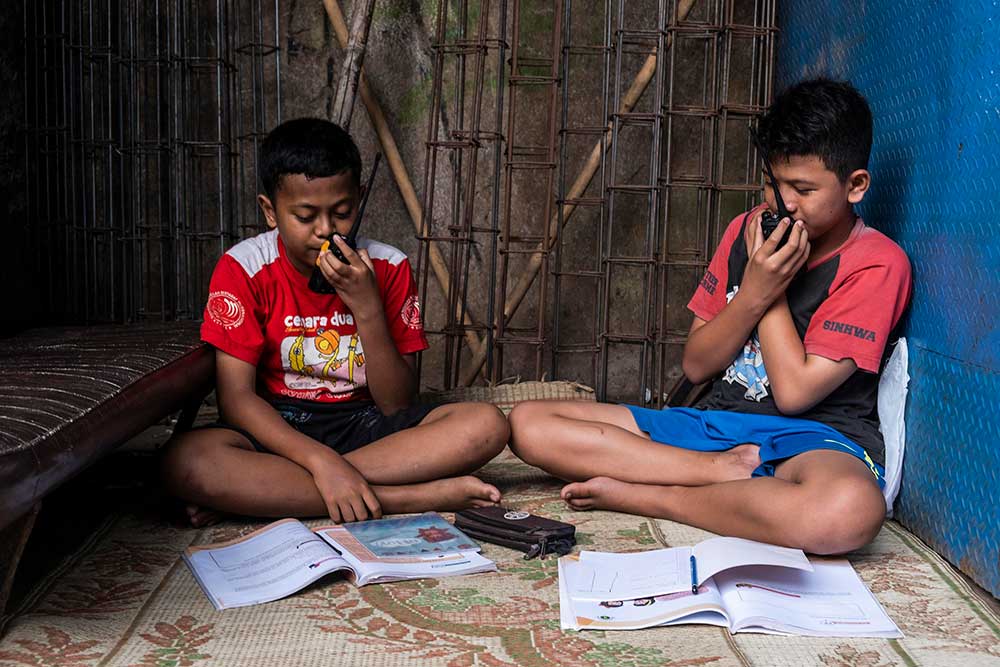

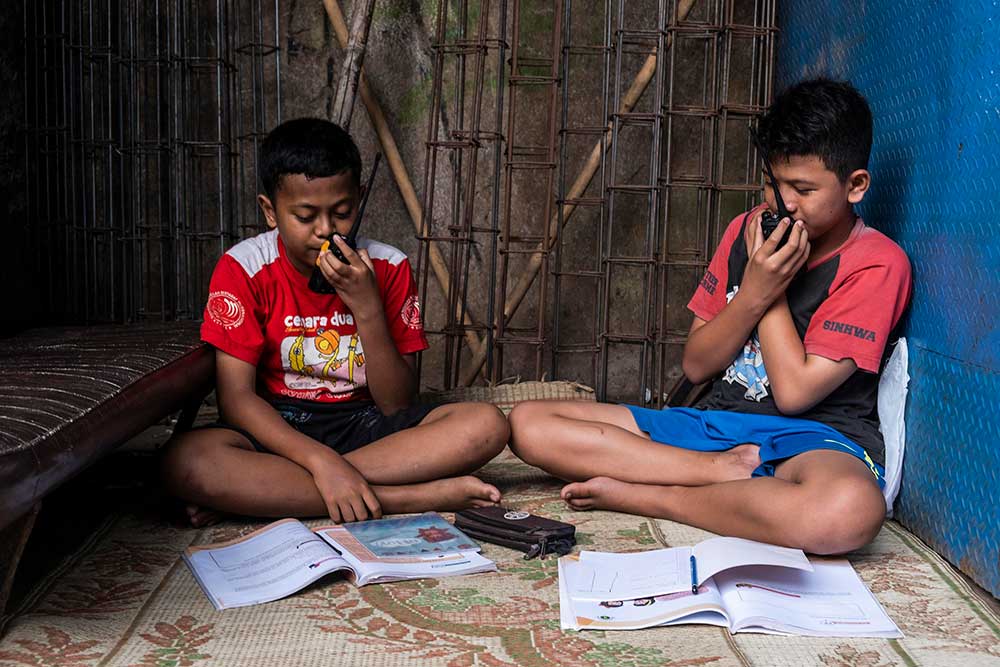

Satria Fikri and Muhammad Zaenal, students of Mojo elementary school use walkie talkies to hear their teacher’s instructions during distance learning amid the Covid pandemic in Solo, Central Java, Indonesia, in February 2021. © Agoes Rudianto/NurPhoto via AP

“Over 50 percent [of my students] don’t have internet. How are they supposed to work?… They went to the library and sat in the parking lot and did their work there… They have to make sure everybody has access to internet… Especially the kids in the rural areas. Those are the kids that get left behind because they just don’t have it.”

— Teacher, US

“The [government’s online] platform works well, but not everyone has access! A lot of kids have smartphones that they bought themselves, but what good is a phone if they don’t have internet? Some teachers can’t access the internet either.”

— Teacher, Ecuador

“I was so desperate but we didn’t have money to buy a phone.”

— Jyoti, 12, Nepal

“I have colleagues in schools in the center of [the nearby city of] Antigua, who tell me that they do meetings on Zoom or send assignments through [Google] Classroom. Those of us from the villages don’t have access to this technology.”

— Teacher, Guatemala

Students shake hands with their teacher Parmin (58), when he makes a home visit to students who have poor cellular service and cannot learn online at the remote area in Senden village, on the slope of Mount Merapi and Merbabu amid, in Central Java, Indonesia, in October 2020. © Ulet Ifansasti/Getty Images

“Half of the grade doesn’t have a laptop, or Wi-Fi, or a smartphone for WhatsApp. They haven’t been following classes at all…. There’s been no communication with these kids whatsoever. No one’s heard from them.”

— Santiago, 17, Venezuela

“I have to take my motorcycle and go to [another village] about 12 kilometers from home. I usually went there four times a week to get phone signal.”

— Mia, 17, Indonesia

“I find it complicated to deal with the Classroom app. The first few weeks I had difficulties with installing and understanding how to use it... No one explained to us how to use Classroom. Due to the challenges in working with the Classroom application, I am very stressed, and I don’t feel well.”

— Mariam, 17, Kyrgyzstan

“For students who are brand new to the country or had interrupted schooling, one big issue is that they weren’t proficient in using the technology before the pandemic… A student…was telling me that the video his teacher sent didn’t have any sound. I asked him if he turned up the volume and he said ‘Yes,’ but what he was actually doing was just pushing ‘mute’ and ‘unmute’ on the video over and over... Just getting a computer―that’s step one in equity. Having access to the content is the way bigger issue.”

— Teacher, US

Fernanda and her sister attend a class on their mother's cell phone after the channel where their school year classes were broadcast failed on August 28, 2020, in La Paz, Mexico. According to official statistics, 56% of Mexican households have access to internet while 93% have a television. Radio programs are used to reach children with no connection nor TV. © Alfredo Martinez/Getty Images

“Many students know how to use their Xbox to play Fortnite or [their] phone to use Snapchat, but struggle to send emails or use educational resources.”

—Teacher, US

“When I sent them the first assignments, I was expecting them to send me back Word documents, files. But I received photos of pages of their notebooks instead… I had students with poor equipment, and also with poor digital skills. They couldn’t rely on a good digital expertise, as nobody had provided them with that resource.”

— Science teacher, Italy

“We thought it would be easy for students, but it wasn’t. They have cell phones, but had difficulties accessing Google Classroom. I had to give personalized assistance to students. The state Education Ministry did tutorials for students, but students didn’t always understand. Students use phones for music or social media, but can’t always use specific apps.”

— Teacher, Brazil

“I… got distracted on the internet. You see a YouTube ad and you’re like ‘Oooh!’ and you click on it, and then you see the shoe sale and you’re like ‘Ahhh!,’ let me click on that video. When I see something really popping like an ad… and I get a notification that a new video is up, I'm… going to click on it.”

— Lwandle, 17, South Africa

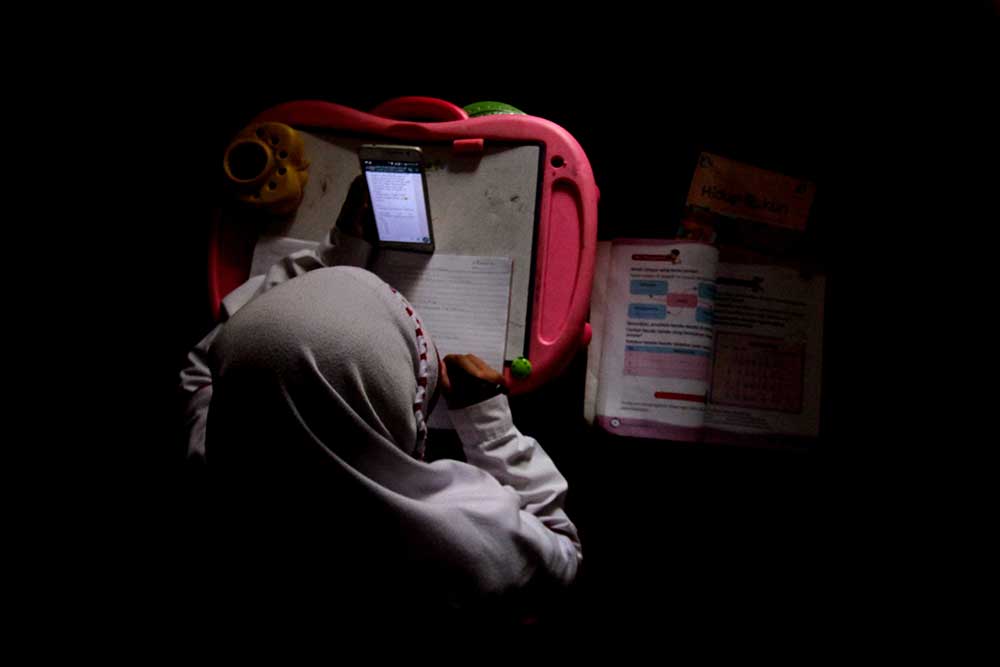

A student uses a mobile phone to do school tasks assigned by her teacher as part of an online learning system amid the coronavirus pandemic in Jakarta, Indonesia in July 2020. © Eko Siswono Toyudho/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

“The Math teacher circulated on the WhatsApp group our [Microsoft] Teams ID numbers and passwords… I tried them many times, but it didn’t work… Pretty much all other students were in the same situation. Not all of them, though. One of my classmates is a geek. She’s very high tech. She did her thing, not sure what, but finally sent us new passwords. This time, it worked.”

— Nawal, 16, Morocco

“The faculty at our school were not prepared on the technological side. The platform used was fraught with glitches they did not seem capable of over-coming. Also, the teachers had received no methodological training and their lessons were ineffective and hard for the kids to digest.”

— Mother, Russia

“It is very hard for him to see sign language via phone. He can hear to some extent, but there are some words that he has to also see. Imagine watching it on the phone, it is very hard for his eyes too, and imagine also the phone screen divided into seven.”

— Mother, Armenia

Children with disabilities, their families and supporters protest outside the Boston Public School headquarters in Boston's Roxbury neighborhood on September 10, 2020. Parents in Roxbury had raised concerns that their children were not getting a quality education while learning remotely. © Barry Chin/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

“He is an auditory learner, and his school is not doing Zoom sessions… They send the work and then it’s up to the child to do the work. That’s very, very hard because…sitting down and focusing is very difficult for him… He has to have a snack. And then he has to do this. And then he has to walk the dog and then he has to go for a run.”

— Mother whose son has attention deficit, South Africa

“A student of mine… he has great difficulty in concentrating even in person, so we used to do some small modules in person for a quarter of an hour and then we go for a walk. This mode of doing things became impossible… We are afraid that he may not come back.”

— Teacher, Italy

“Most of our students [with disabilities] have no access or support from their parents… It will be a great challenge to get these children ready for school again after such a long break. Their attention span is very short, and now, without having the routine and the daily interaction with the teachers as their person of contact it will be even more difficult.”

— Teacher, Germany

“What I think he needs more than learning letters and numbers is he needs the social impact, to be surrounded by other children.”

— Mother whose son has autism, Syria

Class teacher Margaret Poli leads a story massage session via Zoom at the Scottish Centre for Children with Motor Impairments, Craighalbert Centre, in Cumbernauld, Scotland, UK, in June 2020. These sessions delivered education to children who were “shielding”—staying at home - to minimize the risk of infection from the coronavirus. The centre provides educational and therapy services for children and young people throughout Scotland affected by cerebral palsy and other neurological conditions. © Andrew Milligan/PA Wire via AP Images

“Staying at home harms his case. Going to school, in and of itself, is therapy. This is where the interaction happens, be it with teachers, with other kids, like him and unlike him. School, in and of itself, is socializing, which is what children with autism need.”

— Mother whose son has autism, Lebanon

“My children in speech [therapy] are going to be so far setback for so many reasons. One, they’re missing so much school, and being around peers encourages conversation.”

— School administrator at a Native American tribal program, US

“Kids love to be on a computer and there are a lot of programs geared towards kids with disabilities—especially ADHD—but they’re expensive as hell. Low-income school districts like mine couldn’t get that sort of thing.”

— Teacher, US

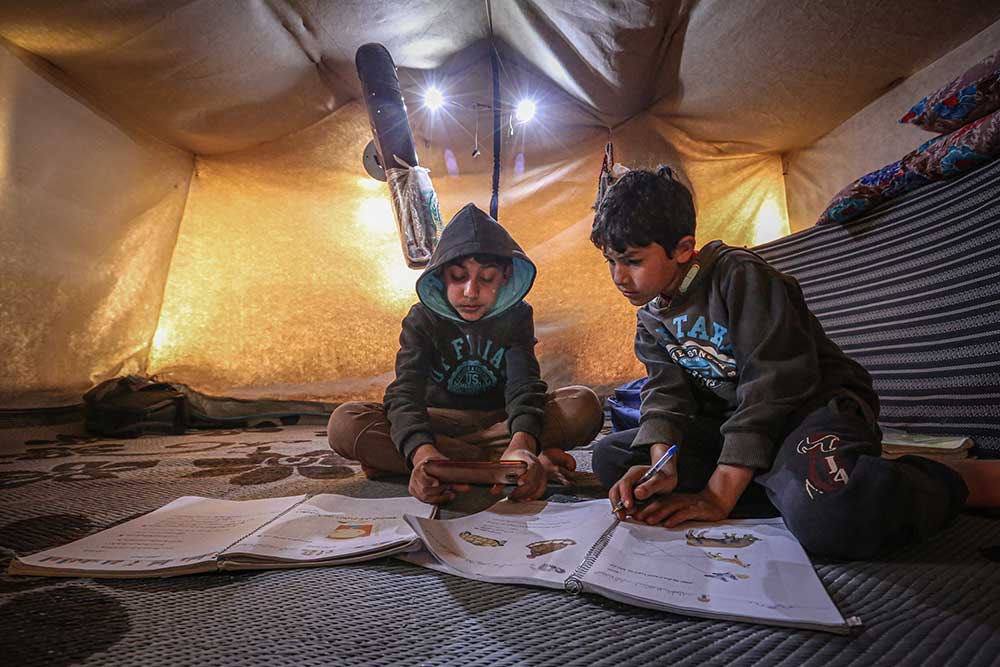

“He is 15 years old, he is supposed to be in 9th grade but he is in 6th grade because we were living under Islamic State territory for three years and schools were closed. And then for one year we were living in a camp for displaced families… We returned to our town in 2019 and it took another three months until the school officially opened because there was a lack of teachers and stationery and books. He started school again in December… He only studied for 80 days or less, and then we had this Corona pandemic crisis.”

— Father, Iraq

“We have no access to learning… This situation did not start with Covid-19. Prior to this we had no lessons for three weeks because a lot of teachers were running away from North Eastern Province due to a rise in terrorist incidents.”

— Taisha, 16, Garissa, Kenya

Two boys follow a lecture by smartphone from their tent in a camp for displaced people in Armanaz town, Idlib, Syria in April 2020. © Muhammed Said/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

“Children feel unoccupied… they are going to look for a job, which could be to join the armed groups in the forest.”

— Father, Congo

“With Covid, the government had to restrict children’s access to schools… But before the coronavirus crisis, few schools were already operating properly… It’s difficult to talk about education here.”

— Education NGO worker, Cameroon

“Education is the main reason we came here all this way, to have an opportunity to study and make a future… [There have been some irregular classes run by refugees inside the camp.] You can’t call that school.”

— Father, Afghan refugee seeking asylum, Greece

“We have two Chromebooks and five of us share. Each of us has one hour or two hours… When I went to school, I used to understand more.”

— Khaliq, 14, Syrian refugee, US

A Rohingya refugee girl holding a religious book in Kutupalong Rohingya refugee camp in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. Before the Covid-19 pandemic, Bangladesh authorities denied Rohingya refugee children access to formal accredited education, allowing them access only to informal “learning centers.” As a result of lockdown measures to prevent the spread of Covid-19, all learning centers were closed in March 2020 with no alternative options for remote learning. Before the pandemic, Human Rights Watch called on the Bangladesh government to urgently lift the restrictions that unlawfully deprive almost 400,000 Rohingya refugee children of their right to education. We continue that call today. © K M Asad/LightRocket via Getty Images

“I only have a phone, no laptop. My phone line has internet on it, about 20 GB, costs 10 Jordanian dinars [US$14]. It’s not enough now with using YouTube all the time… Sometimes I don’t top up my line or top it up after disconnecting for a week or so. When I don’t have internet on my phone, I use the book, I try to understand the lesson just from the book, but I don’t really understand.”

— Mohammad, 19, Sudanese refugee, Jordan