Key Individuals Named in this Report

I. Summary and Recommendations

II. Background: New Delhi and Bombay

III. Background to the Protests: Ratnagiri District

IV. Legal Restrictions Used to Suppress Opposition to the Dabhol Power Project

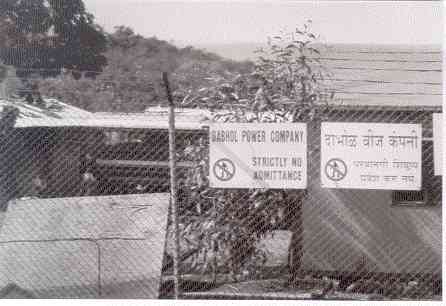

V. Ratnagiri: Violations of Human Rights 1997VII. Complicity: The Dabhol Power Corporation

VIII. Responsibility: Financing Institutions and the Government of the United States

Appendix A: Correspondence Between Human Rights Watch and the Export-Import Bank of the United States

Appendix B: Report of the Cabinet Sub-Committee to Review the Dabhol Power Project

Appendix D: Correspondence Between the Government of India and the World Bank

Beginning in 1994, when construction of the Dabhol Power project began in Ratnagiri, local farmers, shop-keepers, fisherpeople, politicians, and other residents of the district staged protests against it. Protests ceased in 1995 through the end of 1996, because construction at the site was suspended due to the cancellation of the project by the Shiv Sena-BJP government and during consideration of the CITU case.

Less than a month after the dismissal of the CITU case in December 1996, demonstrations against the DPC project resumed in Ratnagiri district. With the exception of one incident of stone-throwing and one incident in which a water pipeline was damaged, these protests were peaceful, and at no time did opponents of the project advocate violence. The police response was abusive, however. For example, Dr. S.B. Bhale, who since January 1997 has worked at the Guhagar rural government hospital—the hospital closest to the Dabhol Power project—commented on police brutality during demonstrations:

If the police actually bring people for treatment, they may bring them to the government hospital. I have seen at least ten to fifteen people over the last year who were brought by the police after demonstrations. All of these people had injuries consistent with beatings by lathis: contusions, abrasions, cuts. Two people had fractures on their arms and hands because of beatings with lathis. When people are brought by police, the doctors do not take medical histories, they just treat their wounds. The police will take their information at the station and tell the hospital people to “just treat them.”112

The abuses took place in the context of a state of emergency that had been imposed for DPC’s benefit, and those responsible were state agents acting at the company’s request with additional surveillance provided by DPC.

After a brutal police raid on June 3, 1997 (see below), demonstrations became less frequent, because villagers feared the repressive tactics of police and many were facing charges still under adjudication. However, local opposition to the project remained strong. Ataman More, a local leader of the opposition to the project, told Human Rights Watch in early 1998, “[P]eople still oppose the projectand protests could intensify except for the police atrocities and harassment.”113 Prohibitory orders were still being renewed at fifteen-day intervals, and criminal proceedings against opponents of the Dabhol Power project continued to be adjudicated.114

This report focuses on a series of thirty demonstrations that took place—at the height of opposition to the Dabhol Power project—between January 13 and June 1997 in Guhagar and Chiplun, population centers in Ratnagiri district.

112 Human Rights Watch interview with Dr. S.B. Bhale, Guhagar village, February 15, 1998. 113 Human Rights Watch interview with Ataman More, Veldur village, February 14, 1998. 114 Indian People’s Tribunal for Human Rights, Submission on Enron in India, April 17, 1998, p. 4.