The window didn't last long. By mid 1995, Rongpo monks were in serious trouble, and their troubles escalated over the next two years. This is the story of three of the Rongpo monks, all now in exile in Dharamsala.

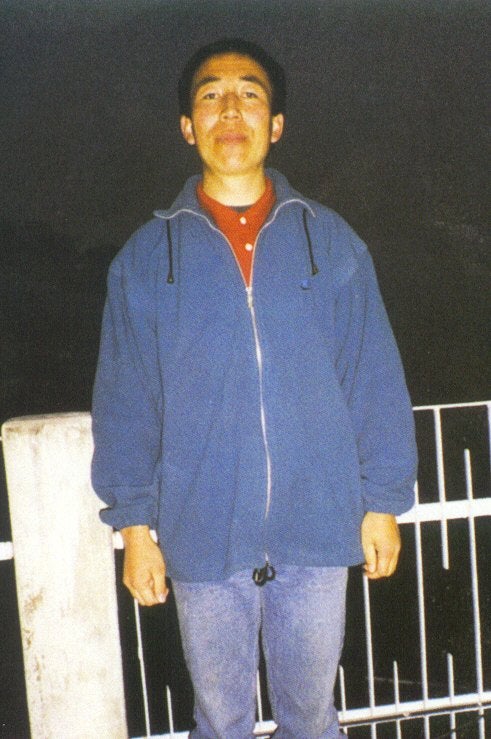

Tenzin Nyima

As

an activist monk, Tenzin Nyima (now twenty-nine years old), conceived and

executed a plan to hang two Tibetan flags in prominent sites in Repkong,

the prefectural capital of Huangnan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, in Qinghai

Province, where the Rongpo monastery is located. Chinese authorities, aware

of the symbolic importance of the Tibetan flag, ban its ownership and display.

The repercussions went on for most of 1997. Some monks fled, many others

were questioned extensively, and several were arrested, Tenzin Nyima among

them. But he engineered a daring escape, as he had two years previously

when he was captured at the Tibet-Nepal border on his way home from India.

As

an activist monk, Tenzin Nyima (now twenty-nine years old), conceived and

executed a plan to hang two Tibetan flags in prominent sites in Repkong,

the prefectural capital of Huangnan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, in Qinghai

Province, where the Rongpo monastery is located. Chinese authorities, aware

of the symbolic importance of the Tibetan flag, ban its ownership and display.

The repercussions went on for most of 1997. Some monks fled, many others

were questioned extensively, and several were arrested, Tenzin Nyima among

them. But he engineered a daring escape, as he had two years previously

when he was captured at the Tibet-Nepal border on his way home from India.

Today in Dharamsala, Tenzin Nyima spends much of his time studying English with two other Rongpo monks, Lobsang Tenzin and Lobsang Lungtok. Their experiences, similar in some respects and very different in others, broaden understanding of monastic life in Amdo, the campaign for Tibetan independence in Rongpo monastery, and Chinese government attempts to cleanse it of all so-called splittist influences. The monastery complex, whose beginnings reputedly go back more than six hundred years, is a major Tibetan Buddhist center and a prime tourist attraction. Despite sustaining devastating damage during the 1958-59 Tibetan uprising and the 1966-76 Cultural Revolution, Rongpo still has an extensive collection of Buddhist art housed in beautifully restored buildings.

Repkong town, originally centered on Rongpo, was still 69 percent Tibetan in 1994, and today Tibetans still dominate much of the surrounding high grassland area, where Tenzin Nyima and his nine brothers and sisters grew up. They all helped grow barley, wheat, and rapeseed and care for the family's sheep and yaks in Sakor, a small village of some thirty families seven kilometers from the town itself. All ten children attended the village primary school; none continued to middle school. Tenzin Nyima started when he was nine, completed fifth grade at the age of fourteen, and in the same year entered Rongpo monastery. There, he studied poetry, grammar, astrology, and dialectics, and committed Buddhist prayers to memory at one of the monastery's three "colleges"-or units-each with its own curricular emphasis. One of Tenzin Nyima's younger brothers later joined him at Rongpo.

In March 1994, Tenzin Nyima and another monk from Rongpo, Lobsang Gyatso, went on a pilgrimage to India to meet the Dalai Lama and to visit Buddhist holy places. They had no trouble reaching Dharamsala, but in late spring 1995 on the way home, they were caught in the city of Dram near the Tibetan border. Tenzin Nyima says that he had to carry wood and the soldiers beat him frequently. But because it was considered extremely difficult to escape from Dram, Chinese PSB officers there were sometimes lax about monitoring the prisoners. Tenzin Nyima and Lobsang Gyatso observed their negligence, and after six days in Dram they managed to escape. They were recaptured almost immediately in Nyelam (some four hours from Dram by car) and spent another six days there.

Tenzin Nyima blames his "damaged memory" on the treatment he received in Nyelam. During his interrogation, he was not only badly beaten but given electric shocks, twice on his hands and four times on the front of his head.

It became dark in my head. And later, when I tried to speak, I wasn't able to speak clearly. They treated me so harshly because of how I answered their questions. When they asked me, "Why did you go to India? Why did you go to meet the Dalai Lama? How did you know the Dalai Lama was in India?" I said, "I became a monk at a young age and I knew that the Dalai Lama was Tibet's lama. I wished to meet him."

After six days in Nyelam, Tenzin Nyima

was finally free to continue his journey home. Back in Repkong, Huangnan

prefecture PSB officers questioned him for only a few days, but he remained

under surveillance even after he rejoined his monastery. As he explained

it, "A friend had warned me that someone was watching me. Sometimes this

person wore a PSB uniform; sometimes not. But I didn't know for sure that

I was always watched until I was arrested [in June 1997]."

During the intervening two years, Tenzin

Nyima concentrated on his studies, but not to the exclusion of his political

interests.

Lobsang Tenzin In June of 1995, not long after he returned to Rongpo from India, Tenzin Nyima's two Dharamsala friends, Lobsang Tenzin and Lobsang Lungtok, were arrested just hours apart for "political crimes." At that time, the two were not yet friends, but neighbors; they had never coordinated their independence activities, and their subsequent histories differed in many respects. Lobsang Tenzin was never sentenced; Lobsang Lungtok, after a full-blown trial, was sentenced to an eighteen-month term for "counterrevolution propaganda with intent to sabotage the unity of the nationalities."

Like Tenzin Nyima, Lobsang Tenzin came from a farm family in a village near Repkong. In 1987, at the age of fourteen, when his days at a village primary school were finished, he entered a small monastery called Geutang, near his home. But by the time he was nineteen, he had left for the greater study opportunities available at Rongpo. Like many other monks, Lobsang Tenzin lived in the monastery compound in a house built for him by his family. Lobsang Tenzin described his first arrest, on June 5, 1995 at around 2 a.m.:

While I was asleep, more than ten policeman jumped from the walls of the monastery into the courtyard of my house. I didn't know they were there or how long they had been there until they switched on the light. About ten were in the house, and several more were outside. None had on uniforms, but the policemen and I knew one another, because the monastery and the prefecture headquarters of the Public Security Bureau are both at Repkong. I don't know if they were armed or not. They didn't show me any documents.

Because I knew they were policemen, I didn't say anything and pretended to be asleep. They said, "We know all about you, and we have to search your house." They searched all my books and took those they needed. Then they said, "Now wake up and put on your clothes. You have to come with us to the office. We have some questions." They closed the door, locked it, and kept the key. One of the policemen asked if he should turn off the light, but the head of the county PSB said I would be back soon.

We drove with the red light on top of the car on but without the siren. First we stopped at the prefecture PSB office for me to sign a paper. Then I was taken to the Repkong County Detention Center.

From 1995 through 1997, independence posters surfaced periodically in Rongpo, and books and pamphlets-some from Dharamsala-were circulated. Lobsang Tenzin had his share and copied extracts from them onto 8-by-14-inch paper. After adding his own ideas about what he considered to be an ongoing campaign to eradicate Tibetan culture and the Tibetan people, he photocopied the results at a shop on a main road in Repkong. But Lobsang Tenzin's plan for posting and distributing the posters was never realized. All copies were seized in a police raid on his house, along with eight notebooks in which he had written essays about Tibetan independence and human rights. Rongpo monks had regularly patronized this photocopy shop, and the shop's owner had been routinely supplying the PSB with copies of independence materials processed there.

During his interrogation the next day and the following week, Lobsang Tenzin answered all questions according to whether he thought the police already had proof of the activities they were asking about or whether they were trying to trap him into confessing to something they weren't sure he had done. They asked about the posters and notebooks; but much of the interrogation was an attempt to uncover his confederates. Lobsang Tenzin says his interrogators kept telling him:

We know all about you: your crime is not that big. We are investigating where the documents about Tibetan independence and human rights came from. We will forgive your crime and give you a reward if you will tell us, and also tell us the names of the people who are spreading the campaign.

Throughout this first week of interrogation and during additional questioning some three months later, Lobsang Tenzin was never beaten. He said he thought this was because his interrogators were Buddhists. He did admit to being frightened but was still willing to speak out about his belief in Tibetan independence and in the Dalai Lama, and about the farmers' and nomads' tax burdens. After his interrogators instructed him to write down all he had said, the questions stopped.

Seven months after his detention, on January 6, 1996, Lobsang Tenzin was temporarily released on the conditions that he appear when called and request permission if he intended to leave the area. Although he was permitted to return to Rongpo, life there became very difficult. He explains:

The police would constantly come near the walls of my house and climb on the roof to watch and listen. Many times when I wasn't home, the police searched my house. They came inside like thieves, but without stealing anything. They left a lot of footprints. My family would notice this when they came to visit, and it became their wish that I go to India. They had been told, "If policies become slightly more strict, your son will be in real trouble." And my friends told me, "Don't do this kind of work again. If it causes problems for you, that's okay, you are a single person. But after you are arrested, it will cause problems for many people."

More than two years after his release, on March 11, 1998, and a year after a major eruption at Rongpo monastery, Lobsang Tenzin left home, arriving in Lhasa four days later. From there he traveled to Dram on a business pass. By March 25, he was in Kathmandu and by April 1 in Dharamsala. His family sold the Rongpo house they had built for him.

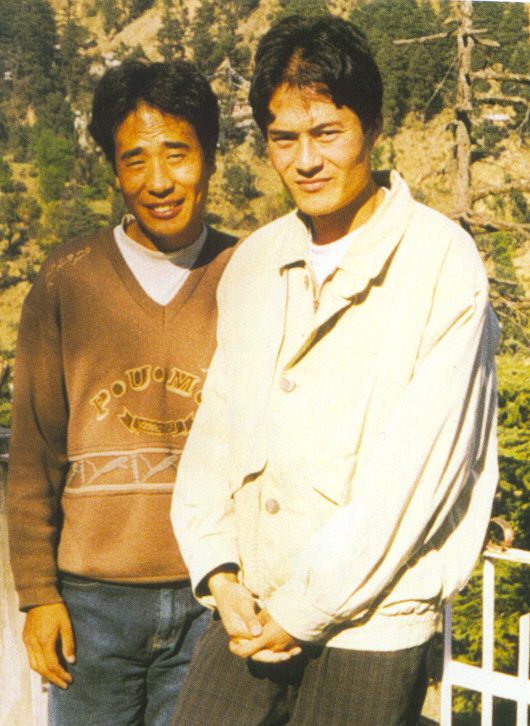

Lobsang Lungtok (right) and Lobsang Tenzin,

1998

Lobsang Lungtok Lobsang Lungtok's early history is similar to those of his friends. Together with eight brothers and sisters, he grew up in a small farming village near Repkong, attended school until the age of fifteen and then, in 1990 or 1991, entered Rongpo monastery. He describes parts of the initiation process:

The first thing is a haircutting ceremony. After that you go to the highest lama and get permission to enter. And the third thing is to go to the head monk, called the geko [the disciplinarian in charge of enforcing the monastic rules and regulations], and try to get permission from him. The Chinese government says there should be a limit on the number of monks in the monastery, so the committee that runs the monastery says so, too. But in practice, if anyone wants to be a monk, he can be a monk. It is not necessary to seek permission from the Chinese authorities. But before anyone is admitted, he must sit for the exam given by the Religious Affairs Bureau. The Chinese say, "If anyone is admitted without sitting for exams, he is not a qualified monk." [If you pass], you get a certificate stating that you are qualified to be a monk.

Lobsang Lungtok explained that a high percentage

of Rongpo monks had not taken the exam, but during his years in the monastery

they faced no special problems. The one difficulty he was aware of applied

to those whose homes were outside Repkong. Although technically they could

not be admitted to Rongpo, many did manage to obtain the necessary special

permission from the abbot. A second reported difficulty involved monks

younger than seventeen. They were forbidden to sit for certification.

Lobsang Lungtok recalls his middle school

years:

I didn't participate in protests against the Chinese, but a sense of nationalism: being a Tibetan, loving Tibet, grew in my mind. My older brother, Gendun Gyaltsen, was already a monk in Rongpo monastery. He was arrested without any reason by the Chinese, and I was very upset. It was said that he pasted up posters. I was a school kid, and one day I went to his room in the monastery and four Public Security Bureau officers were searching it. They found the "master letter" [from which the others were copied]. . . . One officer frightened me and searched the bag I was carrying. There was a love song written in one of my notebooks. When he saw that, he asked, "Are you a student or not?" They told me I was very bad. My brother was detained for five or six months. In 1991, after he was released, he went to India. When he returned, he was held for ten or fifteen days in the county detention center.

After my brother and I were in prison, my mother said, "Our family does too much work for Tibet. Now stop it. What use is it to us?" Earlier, my father and his brother had come up with a letter that spoke out for the death of all Chinese; they faced many problems.

"In March 1995," Lobsang Lungtok continues, "the Tibetans in India said a peace march was coming from Dharamsala to Tibet. So I started putting up posters in support of the march and accusing the Chinese of destroying Tibetan culture. The Chinese found out about it, and they arrested me."

Altogether, Lobsang Lungtok hung five large posters on the walls of the monastery, at the middle school, and at a teacher-training college housed in a large, modern complex. He explained that his posters were somewhat out of the ordinary. "Usually, when Tibetans put up posters they use only simple words that say 'Tibet is independent.' But I wrote a poem about the meaning of independence."

As in Lobsang Tenzin's case, the posters had been photocopied in town. Lobsang Lungtok is certain that the shop owner betrayed him to the police.

Lobsang Lungtok's arrest came close to three months after the poster incident. On June 5, as he was on his way to buy vegetables in the market in Repkong, ten PSB officers, on bikes and in a jeep, caught up with him. In the detention center, set amid agricultural fields on the border between the township and the county in the northeast portion of Repkong, State Security Bureau personnel interrogated him for some ten days, particularly about who had helped put up posters and who was working behind the scenes and advising him politically. Lobsang Lungtok confessed to what was already known to the interrogating officers, that is, that he had composed and hung the posters, but he insisted that he had acted alone, and added that even if he had had guidance, he would never reveal the source. He contended that he had not broken the law.

They asked him what he was doing on the fifteenth of some month in 1993, and other questions about his daily movements. Lobsang Lungtok says that he answered truthfully whenever he could remember. The questions were sometimes harsh, sometimes polite, and sometimes his interrogators just "chatted" in an effort to "educate" him. There were the usual entreaties to confess and work with the security forces in lieu of a harsh sentence, and there were the usual threats that if he didn't, he might never leave prison.

Lobsang Lungtok reports that he had a difficult time in detention primarily at the hands of PAP guards who tortured and beat the prisoners without any reason. Such beatings often came during monthly checks of prisoners' cells. Months after Lobsang Lungtok's release, safe in Dharamsala, the memories are still fresh and painful. He acknowledges that he often thought about and dreamed about his experiences. He describes one incident:

In the first courtyard, a few prisoners had tried to escape by digging a hole. Then after two days, a lot of soldiers came inside our prison and started to beat us. I was in courtyard Number Two. I don't know exactly how many people were in our courtyard, because they made us stand with our faces to the wall. We were not allowed to look, otherwise they would hit our faces. So they beat us from behind. They didn't use any tools. They kicked me at the right of my back and in my ass where the hole is. This was all very painful, and I fell down. Then they shouted, "Stand up!" and beat me with their fists. They started twisting every part of my body-hard twists-mostly just below my chest. I was in monk's dress. One soldier pulled on the belt and untied my robe, and I looked behind me. The Chinese soldiers said, "What are you looking for?" They kicked more. Two soldiers held my head; another punched me on the back. I had a lot of dark-blue bruises. I lay on my bed for a few days. I couldn't walk properly. The soldiers laughed when they saw me walking like that-with my legs apart. I couldn't urinate properly, and it was very painful when I did.

That evening we told them we wouldn't eat. They told us it would harm us if we wouldn't eat, and that we would be able to stop eating for two days, but that then we would ask for food.

Two or three days after that, high officials from the prefecture came. We still had bruises on our backs. They took videos of our bodies and asked us what happened. They told us they would tell the soldiers that something like this shouldn't happen in the future.

Sometimes we were beaten with no reason at all. Sometimes, they would just slap. It's routine in prison to get beaten or slapped.

Like Lobsang Tenzin, Lobsang Lungtok blames his poor memory on prison-related conditions. He, however, attributes it not to the beatings, but to nosebleeds related to a "very bad cold" that started on the first day of his imprisonment. The twelve pills per day he had to take for one week did nothing to stop the bleeding. He also experienced a rapid heartbeat, headaches accompanied by dizziness, and severe pain in all the joints of his hands and feet. The prison doctor visited twice and told him he wasn't sick. After five months of growing progressively weaker, Lobsang Lungtok was shipped to the prefectural Chinese hospital in Repkong for a checkup. The herbal medicine prescribed by the doctor there did not stop the nosebleeds, nor did an injection administered by PSB officers.

Suddenly and unexpectedly, the PSB sent Lobsang Lungtok back to the monastery, perhaps, he thinks, because the authorities did not want to bear the expense of medical treatment. For his part, he hoped to "neutralize" his condition through nutritious food.

He remembers some of his first experiences after getting out of detention:

Someone brought my mother; she slept in my room that night. I couldn't sleep-maybe it was out of joy; maybe because of the change. I did go to my village, but I didn't like to stay there because some of the villagers would scold me for not thinking of my family, my mother. Some of my aunts and uncles were very angry at me for causing trouble for my family. They said, "You can't lift the sky with one finger." My elder brother, Jamyang Lodro, became very angry at them and said, "Even if our finger is broken, we should try to lift up the sky."

He was arrested after I came to India. Now that I am here [in Dharamsala], many people don't want to tell me what happened because they are afraid to tell me bad news regarding my family. He was a teacher in the school in Rongpo. He was detained for about fifteen days in 1997. He had explained the Dalai Lama's speeches to the students. He was a bit strange; he was very outspoken. He used to learn the Dalai Lama's speeches by heart. He always said, "Whenever you wake up, you always have to think, 'Today I will be kind to others.' "

At the monastery, Lobsang Lungtok was far from free. "The security bureau often visited," he explains. "When I was staying with my family, they gave written notice to village offices stating that I was not allowed to go anywhere outside the village, and that if I did, I would be arrested."

By April 20, 1996, Lobsang Lungtok was deemed cured and returned to prison. Five days later, he was formally indicted. In August 1996, he stood trial on charges of counterrevolution. He describes his trial as secret.

There was no one there to watch, just three judges, two procurators, a secretary, my lawyer, and me. The lawyer was paid for by the people from my village. He was supposed to help me but it was just a game to show that I had a lawyer. The trial took three or four hours.

I was standing just below the raised platform between wooden bars as if in a cage with a door. The judge in the middle read out the details of my offense, and the procurators added that I should get a heavy sentence. My lawyer said, "Putting up posters on walls is not a serious activity and should not merit a heavy sentence." The procurator spoke for about an hour and a half, mentioning "splittism." The lawyer spoke half an hour. [Then] the judges began asking me whether I had anything to say about the charges of counterrevolution. I said I didn't feel that I had done anything against the law which could be charged as a counterrevolutionary offense.

Two or three days later, I was called back to court again and they showed me an official paper with "Guilty" written on it.

He received an eighteen-month sentence and two subsequent years' deprivation of political rights, which limited his right to speak freely and to associate with whom he chose.

Lobsang Lungtok decided against an appeal, as the process could take longer than the four months he still had to serve and, according to Chinese law, could result in a longer sentence. His lawyer gave him no advice on the issue. In fact, according to Lobsang Lungtok, "He was like an actor in a movie. . . . He kept insisting that if I confessed honestly, I would get a lighter sentence." Lobsang Lungtok said some of his lawyer's courtroom tactics made him suspect that his lawyer actually was trying to help the prosecution identify other "splittists." Lobsang also believes that he was the first person from his area who actually had a court trial; everyone else had been directly imprisoned.

From the time of his release on December 5, 1996, until he was warned that he might again be arrested, Lobsang Lungtok studied, read in his room in Rongpo monastery, and went to teachings.

Crackdown in Rongpo Monastery Events in Rongpo came to a head on March 22, 1997, when Tenzin Nyima carried out his plan to raise two Tibetan flags in prominent places in the town of Repkong. After purchasing sufficient white cloth to make the flags, he asked a friend, Rigdrol, to draw two snow lions, a nationalist symbol representing the victory of the combined secular and religious authority of the Tibetan government. When the drawings were complete, Tenzin added the words "The Tibetan snow lion will tear out the bloody heart of China." With the help of Lodroe, a monk from his own village, Tenzin Nyima hung one flag from a telephone pole at a highway crossing in the center of Repkong, then cut the rope supporting the Chinese flag in front of the Huangnan Nationalities Teacher Training Institute, climbed the pole, and attached the other Tibetan flag. It was 2:00 a.m. on a Sunday when the flags went up, but it took until 9:30 the next morning for the army to remove them. According to Lobsang Lungtok, once the flags were discovered, the sirens started up and sounded all day.

Tenzin Nyima had chosen the date to coincide with a visit of the Dalai Lama to Taiwan, a trip he had learned about from a Voice of America (VOA) broadcast.

A concerted poster and leafleting campaign in February during Monlam (a prayer festival following the Tibetan New Year) had preceded the flag raisings. Rongpo was clogged with visitors, and posters were everywhere in Repkong, many denouncing the Chinese government's interference in determining which boy was the reincarnation of the Panchen Lama (the second most important figure in Tibetan Buddhism), and demanding that the Dalai Lama's choice be released from "protective custody." Other posters featured a collection of statements by the Dalai Lama, and still others held translations of information from VOA broadcasts. The leaflets were folded and thrown in all the rooms in the monastery. Others were put under each door at night.

Following Monlam, the Rongpo monks were busy, as they are every year, with monastic and collegial gatherings, debates, and prayers, culminating in an examination and promotion to a higher class. In 1997, these activities didn't end until March 19, just three days before the flags went up.

The crackdown in Rongpo began almost immediately after the flags were discovered, and lasted well into April. Most of the forty or fifty monks from Rongpo hauled in for questioning were released in a matter of days, if not hours. The detentions were secret. Each monk was told, "When you leave, you are not permitted to tell anyone that you were detained. If you talk to anyone, you will regret it the next time you are imprisoned." For the most part, the monks took the warning seriously. No one was allowed to leave the monastery and even within the monastery walls, the monks' movements were restricted. "Whenever we did go out," Lobsang Lungtok says, "there were police in and out of uniform walking up and down and they wanted to know where we were going."

Several monks were arrested, some solely for possession of Tibetan flags. One layman, Menba Dorje-a practitioner of traditional Tibetan medicine who often stayed in the monastery, and who was suspected of having photocopied many leaflets and books and of supporting the Tibetan cause-received an eighteen-month sentence. Aware that he would be among those arrested even though he had done nothing untoward since his release, Lobsang Lungtok fled, leaving home on April 12, crossing the border into Nepal with twenty-four others on May 21, and arriving in India in June 1997.

Sometime after midnight on April 22, 1997, almost a month after Tenzin Nyima had hung the Tibetan flags, six officers from the state and public security bureaus jumped into the courtyard of his house on the monastery grounds and took him in for several hours of questioning. Rigdrol and Lodroe were not caught until June, when the evidence against them was corroborated.

On April 27, the arrival of a work team composed of public and state security forces and Religious Affairs Bureau cadres signaled the start of a full-scale reeducation campaign in Rongpo, one that was to last seven months. On the first day, all monks were ordered to a central meeting place on pain of expulsion for nonattendance. Work-team members asked that monks "voluntarily" hand over all photos of the Dalai Lama and all video- and audiotapes and other materials from the Tibetan government-in-exile. According to Tenzin Nyima's account:

They announced this over a loudspeaker and threatened to punish us without mercy or regard for age if they later came to know we had any in our possession. No monks, young or old, handed over any items. The main speaker was the secretary of our prefecture. He was the campaign chairman. He talked about the five main points in the two books he had: oppose the splittist movement; uphold the unity of the motherland; accept the Chinese-chosen Panchen Lama; accept that Tibet is not independent; accept that the Dalai Lama is trying to destroy the country.

He threatened that all the monks who were not from the Repkong region would be sent back. But, at that time at least, the officials were unable to implement such a policy. The work team did close down temporarily a monastery-financed school for monks under fifteen, forcing them to return to their homes. The policy affected some one hundred novice monks.

By the second day of the campaign, forty team members out of the fifty who came were stationed in the three colleges. Each monk was given a letter. The team questioned all the monks one by one but didn't search their rooms. They planted informers to find out who had raised the flag. There were study meetings every day. Each class in each college of the monastery had study books.

On June 18, long before the end of the reeducation campaign in October, security officers again invaded Tenzin Nyima's courtyard in the middle of the night. Twelve officers searched his house, confiscated a copy of the Dalai Lama's autobiography, five VOA tapes, and other compromising material, then brought him in handcuffs to the prefecture-level detention center in Repkong, only minutes away from the monastery. The very next day, Tenzin Nyima was transferred to a prison in Henan Mongolian Autonomous County for six days of questioning. He assumed the transfer had to do with keeping word of mouth about his detention to a minimum.

Once in Henan, Tenzin Nyima quickly came to know that Lodroe and Rigdrol, the monks who had helped with the flags, had also been seized. The knowledge affected his decision to confess after four days of questioning. "It would create more problems for my two friends if I didn't accept my 'crime,' " he says. "I was the head of the work so I had to take responsibility if there was a problem."

Almost immediately following his confession, arrangements were made for Tenzin Nyima and the two others to be returned to Repkong in a two-jeep convoy. As he recounts:

When we were going to Repkong, I was thinking, "If I reach Repkong, I will be taken to court and given a very long sentence. I might be able to escape. But maybe they will shoot and kill me. But if I have to face many difficulties in prison for many years, I will not resent dying."

I kept looking for a good place to escape. And when we reached a forest, I told them I had to pee. The driver and one of the PSB officers got out, and the person in charge of my case told me to go with them. But I didn't. [Instead,] when he had his zipper open, I ran downhill-but I fell down and hurt my leg badly. They shot at me. I forced myself to go on and hid in an isolated spot among tangled shrub, while the officers went straight into the forest [trying to find me].

Tenzin Nyima managed to hide out for three months, time enough for his leg to heal. Some nomad families were willing to help him with food, clothes, and medicine; others turned him away, some out of fear and some because the PSB had spread word that a horse thief was in the area. Finally, Tenzin Nyima knew that he had to flee Tibet.

I received a secret message that I had to move quickly, because the Chinese were going to look for me in the place where I was hiding; I had to leave the region. I traveled to Xining, Lhasa, Dram, and on to Nepal. I heard later that the forest where I hid was sealed off by soldiers and searched for four days. The PSB had distributed about seven hundred pictures of me. They even looked for me in Lhasa. My family's and my relatives' houses were searched at night without warning. They even told people I had a gun and a radio with me.

Tenzin Nyima left his "home country" in September 1997, and arrived in Dharamsala in late autumn.

During the time Tenzin Nyima was in hiding and arranging his escape, security officials were pressuring his two confederates, Rigdrol and Lodroe, for evidence. The outcomes were different. Rigdrol, who had drawn the snow lions on the white material but was told nothing about the plan to make and raise the flags, spent four months in detention before being released on the guarantees of his family and fellow villagers. But Lodroe, who had helped to hoist the flags, was severely beaten during the detention phase of his imprisonment. Later, he was in such pain from an untreated stomach ulcer that on at least two occasions he banged his head against a wall until he lost consciousness. He finally served either one year or eighteen months (exiled monks from Rongpo who knew Lodroe do not agree about the length of his sentence). And there was one last humiliation left for both men. At the October 20 meeting that ended the reeducation campaign in Rongpo, armed soldiers escorted Rigdrol (who was already out on bail) and Lodroe before the assembled monks, lamas, and senior prefecture officials. After they were ceremoniously handcuffed and denounced as "splittists," their sentences were read out. At the same time, the expulsions of eighteen monks, who were deemed not to have been reeducated, were announced. The whole procedure was videotaped and eventually shown on Qinghai television.The meeting itself was described as terrifying, with armed soldiers surrounding the gathering. Having been told that the soldiers had orders to shoot if there were any disturbances, monks didn't dare say a word to each other.

According to available information, no monks from Rongpo have been overtly engaged in independence activities, and none have been arrested since the 1997 reeducation campaign ended in October.

Since coming to Dharamsala, the three friends, Lobsang Lungtok, Tenzin Nyima, and Lobsang Tenzin, have made different adjustments to life in exile. Lobsang Lungtok's time in India has not been free of problems. On January 4, 1998, after five months in the Bir school (a government-in-exile facility where adults can study English), and a month of study on his own, he was jailed for a month and a half for lack of valid residence papers. (India gives shelter to Tibetan refugees, but is not a signatory tot he UN Refugee Convention. Tibetans are technically stateless; they do not have explicit refugee status. Recent arrivals are not even issued residence permits.) It took twenty days for his friends to find out where he was and to be permitted to visit. Government-in-exile officials, preoccupied with security matters, spoke directly with the detainees, but did not request their release until they had satisfied themselves that the detainees presented no danger to the exile community. Lobsang Lungtok had taken part in a hunger strike during his detention, and was apprehensive that he would be returned to China and would face further persecution there. It took more than another year and a half for him to finally find what he considers meaningful and enjoyable work. Until he, too, found work in early 1999, Lobsang Tenzin spent his time studying by himself. Tenzin Nyima's future seems even less secure than his friends'. At the end of 1998, he was still spending much of his time in study on his own. In Dharamsala, "studying" is often a euphemism for marking time.