Almost

twenty years later, in 1994, Rinchen fled to Dharamsala. By then, he

had come to recognize that the Chinese government

used literature solely as a tool for

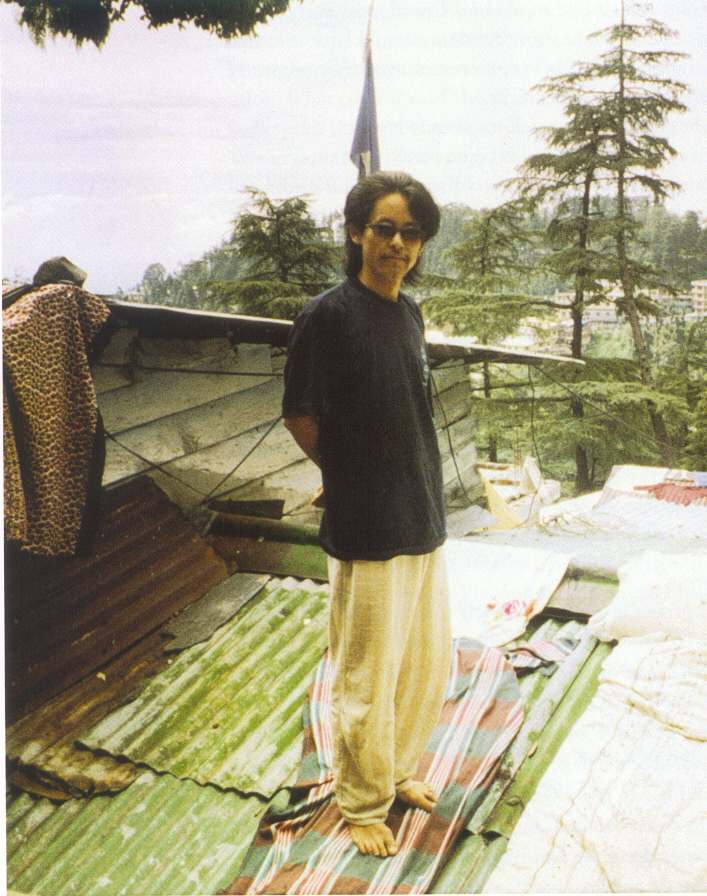

political propaganda purposes. The contrast between pictures of

a confident, poised, clearly happy Rinchen with his college friends and

the man we met in 1998 who could never

quite manage a smile is a reminder of

what Rinchen lost through his commitment to human-rights principles.

Almost

twenty years later, in 1994, Rinchen fled to Dharamsala. By then, he

had come to recognize that the Chinese government

used literature solely as a tool for

political propaganda purposes. The contrast between pictures of

a confident, poised, clearly happy Rinchen with his college friends and

the man we met in 1998 who could never

quite manage a smile is a reminder of

what Rinchen lost through his commitment to human-rights principles.

Rinchen lived from the time he was five until he was twelve with his maternal grandfather. Before being sent off to prison, his grandfather had been a local government secretary in Tianzhu Tibetan Autonomous County in the Wuwei region of Gansu province. He was also a high lama in one of the major sects of Tibetan Buddhism, the Nyingma. (Nyingma monks have permission to marry, among other privileges.) The combination was enough for Chinese authorities to humiliate him by subjecting him to public ridicule and physical indignities before he was sentenced. According to Rinchen, "The Chinese said lamas sucked blood from the public."

Although his grandfather was eventually "rehabilitated" and offered his old job back, he refused. When Alak Shardong Rinpoche, a high lama well-known locally, invited Rinchen's grandfather to return to his old religious activities at Kapuk, the family's small ancestral monastery in Chentsa, Huangnan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, many members of Rinchen's mother's family made the move. Chentsa is one of the richest agricultural regions in Qinghai. It has a long history of Tibetan settlement (at least one extant Tibetan Buddhist site there dates back to the ninth century), and in 1994, 58 percent of the population was still Tibetan.

In 1976, when Rinchen was five and his parents divorced, he, his mother, and his younger sister joined the rest of the family in Chentsa. His mother and sister lived with his grandmother. Rinchen lived in the monastery. For some four years after his mother remarried and moved again, this time to Yulgan, a Mongolian Autonomous County in Huangnan where there are few Tibetans, he remained at his studies in the monastery. From his grandfather and his grandfather's students, Rinchen learned to read and write Tibetan.

In 1983, when he was twelve, Rinchen joined his mother, sister, and stepfather in Yulgan and began his secular studies, completing primary school and lower- middle school in three years instead of the usual five. Back in Chentsa after his stepfather (a teacher of Tibetan) was transferred there, Rinchen continued on into upper-middle school. Upon graduation in 1990, he was admitted to a five- year program at Qinghai Institute for Nationalities, Department of Minority Nationalities Languages and Literature, Tibetan section. There were 280 students all told in his department. Forty Tibetans were admitted every year and forty Mongolians every two years.

Rinchen entered the Institute not long after the 1989 crackdown on the prodemocracy movement that had started in Tiananmen Square and had spread throughout China. He reports:

All the rules and regulations had been changed. We had to go for seven weeks of military training and for one year we all had daily two-hour dang de sixiang jiaoyu (Party thought education) meetings. It was a kind of reeducation. The Tibetan section had a lot of other changes, big ones. Before, Tibetan history, religious history, classical grammar, and logic were taught in Tibetan. That stopped, and the student magazine, called Lagya (Self-Respect), stopped publishing. There was so much reeducation going on it was difficult to study well. After about one year, in March or April 1991, I was finally able to start learning in that institute.

But the Tibetan courses still had not been reinstated. Rinchen said:

[Instead] we had to study politics, a philosophy based on Marxism, aesthetics, modern Chinese language, history of the Chinese Communist Party, and modern Chinese history. There were two courses about Tibet: Tibetan literature-taught in Chinese-and Tibetan language. For the latter, the only one taught in Tibetan by Tibetan teachers, we used a three-book set that had some grammar, some poetics, and some general Tibetan history.

Early in 1991, Rinchen and many of his friends petitioned school authorities for reinstatement of the discontinued courses. When two or three student representatives delivered the appeal to the chairman of the Minority Nationalities Languages and Literature department, he was willing to accept it but told the delegation that school authorities would have to research the matter. Several days later, when the students returned to his office, the chair told them that the petition had gone to the office of the Institute's president and that he, the chair, did not have the authority to decide. The students replied by asking the chairman to return the petition, then going themselves to see the president, who told them that the issue would be decided after proper discussion and research by the Institute's Party Committee. (Schools, like other organizations, have party committees at every level.)

After repeated visits to the president, the students realized they would never get another answer and their effort to reverse all the changes had failed. They decided on another tactic. They would petition only for the reinstatement of the publication Self-Respect. In June 1992, the school authorities granted the request but with a string of conditions attached: First, anything that remotely resembled a political discussion could not be published. Second, school authorities would appoint three advisors, one a Tibetan and the other two Han Chinese-and at least one would be a Communist Party member. All articles were to be vetted by the advisors before publication. Students would have minimal leeway, both in criticizing the school and in voicing opinions. On very rare occasions, they might try to have their political poems or articles published, usually unsuccessfully.

Interested students openly chose twelve of their number as an editorial board, which they called the Youth Literature Committee. Six of the twelve worked together as editors and in rotation as editor-in-chief. Rinchen was one of the six. The renamed magazine, Babchu (Torrent), and the editorial board's official title memorialized Dhondup Gyal, a tragic young Amdo intellectual who committed suicide in 1985 and has since become an icon for a younger generation of Tibetans.

The plan, to publish two editions a year starting in 1992, began smoothly enough. Then, at the beginning of 1994, Rinchen became editor-in-chief. By that time, student complaints had multiplied. "Many good articles were submitted but they never got published," Rinchen noted. "So I made some changes. I removed the names of the advisors from the magazine and planned the next edition without consulting them." Rinchen also contributed an article, "Ruming" (Clan Names), which ostensibly had to do with the relationship between Tibetan clan names and clan spirits. "What the article was really about, though," Rinchen said, "is that a Tibetan can't be more than a deputy head; he can't have a full position. I said in the article that when a Chinese person sees a Tibetan name, he immediately thinks 'fu'; that's Chinese for 'deputy' or 'second.' "

Rinchen continues,

Two or three days after I took the proofs to the printer in Xining, the Party Committee called me and scolded me and asked questions about whether I'd written the clan-name article. I said yes. And they wanted to know about the other articles, too. Someone from the school went to Xining to bring back the proofs. Then I was interrogated. They wanted to know what my motives were, and they wanted to know what I was thinking when I wrote the article. They wanted to know why I didn't consult the advisors, and they reminded me that not consulting them violated school regulations. Then they told me to write a detailed letter of apology to the school president. I had to give a clear explanation of my personal background. I had to tell them what made me write the article. And I had to tell them why I didn't consult the advisors. They warned me not to go to class and not to leave the school compound. . . .

I was very upset. For four or five days, I didn't do anything but think. I didn't believe I'd made any mistakes, so how could I apologize? And that's when I came to realize that the government wanted literature as a means of political propaganda.

In his unhappiness, Rinchen went home without asking school authorities for permission, a move that could have further impeded his academic career. During the two weeks he was there, he made his decision to flee, made his preparations, and one June night left for India.

Traveling by bus, Rinchen went first to Lhasa, where he spent two and a half weeks locating a guide and meeting some monks headed in the same direction. After paying 500 renminbi (then approximately U.S.$70), he traveled in a group of twelve to Saga in the Shigatse region and from there on foot at night to Solo Khumbu in Nepal, a route that took them over some of the highest mountain passes in the world. According to Rinchen, the biggest problem for him was his poor eyesight, which made night travel over a seventeen-day period very difficult.

The group had no serious difficulties until they reached Pema Thang where local residents and Nepali police robbed them of all their belongings and beat them up. He reported: "They beat some of the group with guns and sticks- some seriously, some were hit on the head. Then they told us to move on-but we didn't want to. So the police beat some of us again and threatened to hand us over to the Chinese. So we moved on a little way and finally were able to go to sleep."

Some Tibetan-speaking Nepalese people guided the group members to a police station where they hoped they might find help retrieving their belongings. The officers there took them back to the place where they had been caught. "We didn't get our money back, but we got everything else back," Rinchen reports, "And the police promised they would bring us to Kathmandu." For two days the twelve group members waited in prisonlike conditions until the officers escorted them to the next police station. The officers at the second station then took over, accompanying the group to the next police station, and so on. But each leg of the trip took a long time because, for safety's sake, the route was never direct. In Pokhara, the group was held up for five days before being sent on to Kathmandu by bus.

But their troubles weren't over. Rinchen and the others arrived in Kathmandu on a Saturday when the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) office was closed. "We were held in cells until Monday," he said. "The place looked like a prison. The Reception Center (a Tibetan government-in- exile agency) paid 500 Nepali rupees [approximately U.S.$7.40] each so we could be released."

In August 1994, Rinchen arrived safely in Dharamsala, where he now works for a Tibetan freedom movement.