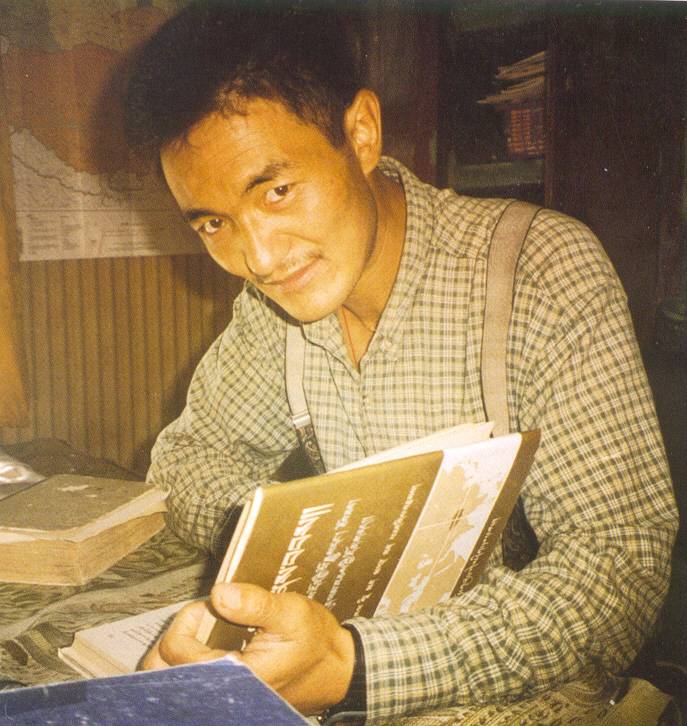

When we interviewed him, a year after he had left home and eight months after reaching India, most of his energy was still focused on coming to terms with making a permanent home away from his family in Amdo. In telling his story, this tall, imposing young man was sometimes quite animated; at other times, he was lethargic and removed, or despairing, as though he were reliving his ordeal. It was obvious that he had endured a terrible trauma.

Lukhar Jam was born in February 1969, one of seven brothers and sisters in the semi-nomadic area around Chabcha, the high-elevation capital of Hainan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture in Qinghai Province (Amdo). As he was growing up in that area, with a mostly Chinese population, he came to realize that there was a marked difference between Tibetans and Chinese.

I didn't like being under Chinese pressure. I personally didn't like the Chinese Communist system and their hypocritical activities. I knew Tibet was an independent country, and that China occupied it with the use of force and slaughtered many people. Tibetans are . . . totally different from Chinese. So I didn't like the policy of China being over Tibet. Tibetans will always be Tibetans,but the Chinese use their policies to divide Tibetans. They place them inseparate administrative areas-in Gansu province, in Yunnan, Sichuan, andQinghai, and in the Tibet Autonomous Region.

Lukhar Jam completed both primary and lower-middle school in Tsigorthang, an area of Xinghai county, a basically pastoral and overwhelmingly Tibetan county in Hainan. He then trained as a farm-machinery mechanic at a technical school, but never worked at that trade. Instead, in October 1991, he left for India, traveling by bus to Lhasa, then Shigatse and Sakya, and on foot to India viaSolo Khumbu in Nepal. Other than being short of money and sometimes offood, he had a relatively trouble-free journey. Lukhar Jam stayed in Dharamsalaeighteen months where he studied Tibetan literature and English. Then hereturned home.

The return trip, however, proved to be much more stressful than the original journey for Lukhar Jam, both physically and mentally. He was carrying copies ofthe Dalai Lama's My Land and My People, a videotape of a speech the DalaiLama made when he accepted the Nobel Peace Prize in 1989, and human rights documents including some sixty copies of the Universal Declaration ofHuman Rights, and he therefore made a detour across the mountains instead ofheading directly for the official border.

I carried the books and videotape home because people, especially older people, wanted to see the Dalai Lama. They often prayed they would see him inTibet. I knew the books and tape would bring happiness to them. Tibetans don'tknow about the Universal Declaration, and I thought that if I distributed copies it might help them to understand.

Lukhar Jam arrived home on December 15, 1992. Once there, he and some of his intimate friends, both men and women, organized a "dare-to-die" youthgroup of activists willing to play a front-line role and take sometimes inordinaterisks for their beliefs. As Lukhar Jam had anticipated, people were very pleasedwith the materials from India, so much so that sixty copies were not nearlyenough. He and his friends managed to buy a mimeograph machine and distribute copies directly to people and by mail to monasteries and schools inregions of Qinghai other than Chabcha. But almost from the start, the organization faced two problems: finances, and the danger to group members from public and state security branches. Lukhar Jam managed to alleviate the money worries by selling some of his family's domestic animals. "I was thebehind-the-scenes operator," he said, "and even though I had no work, I acted like a businessman. My parents really loved me and were very kind to me and didn't stop me from doing what I wanted. They gave me money, but I never told them what I was up to."

About two months after Lukhar Jam arrived home, he concluded that the project was a failure, and without telling his family he set off again for India. OnFebruary 25, 1993, at night, Lukhar Jam and ten others left Shigatse and headed for Dingri County in the Tibet Autonomous Region. After one member of the group became ill, all eleven stopped at a lodge run by the Dingri County administration. But just before dawn, when they were about to leave, they found themselves surrounded by six or seven armed border-patrol soldiers and public-security officials, who immediately began to frisk them and to search theirbelongings.

Lukhar Jam, now 1,200 kilometers from home, with only 50 more to go before he reached the Chinese border, knew he was in trouble. Although some of thedocuments and books he was carrying were available in local bookstores in Amdo, the Chinese government had labeled them neibu (internal). The most sensitive document, which he had procured from another source, was a Chinese map dating from before 1950. It was a planning document issued bythe Lanzhou area command's military headquarters showing entrance points for an invasion of Tibet, along with local population figures in the affected areas.According to Lukhar Jam, such numbers made it relatively easy to calculate the critical differences between the pre- and post-invasion population. The other documents, regional gazettes on the national economy, the tax structure, education, and family planning, were the kind, he said, "that give informationgovernment officials don't want people to know, although there are no current secrets in them."

Even more critical -- not only for Lukhar Jam's own safety, but also for that of two of his friends-were petitions with photographs of them attached; he was carrying these papers to the Dalai Lama. Both men were still in Amdo. One,named Tsegon Gyal, was a former policeman in Tianjun County who had beendetained for a month in 1989; the other, Namlo Yak, was an education official inTsigorthang, the county where Lukhar Jam had gone to school. Namlo Yak had been interrogated in 1990. The details of the two men's ordeals were spelled out in the petitions, as was information about the persecution of Tibetans in Tibet. (As a result of the seizure of these documents, Tsegon Gyal and NamloYak were, in fact, detained in May 1993.)

Lukhar Jam was detained in the Dingri County Detention Center; the others were released. Some may have reached India: word of Lukhar Jam's capture reached Dharamsala quickly. State Security Bureau officials in Dingri conducted some perfunctory interrogations during the week or two when Lukhar Jam was there. But his case was considered serious enough for him to be sent back to Shigatse where higher-level officials could take over. Lukhar Jam's objective during interrogation was to buy time to get a message to the friends whose petitions he had been carrying, urging them to flee. To that end, he lied about where he had procured the neibu books and documents, telling his interrogators that a friend in Lhasa had offered to pay his travel expenses if he took the books to Nepal. The friend, Lukhar Jam told them, was already in Nepal on a travel pass.

Lukhar Jam describes his prison experience in detail:

The prison regimen is the same for political and criminal prisoners all over China. In Dingri, I was not beaten or tortured. But Shigatse was another story. I was on my knees, my hands were cuffed together with one arm over my shoulder and the other behind my back. My shoulder became dislocated. I wasnot allowed to sleep for two days and nights and they didn't give me much food.I fell asleep and fell over and hit my head. . . . I was interrogated for five or six hours a day and when I fell asleep they poured water on me. When they weren'tinterrogating me, they tied me up, but even then when I fell asleep, they pouredwater on me to wake me. . . . This all happened in the prison office and manyPublic Security Bureau officers were involved. Then I was taken to a cell. Mytorture increased because I was not cooperating. For about a week more, I wasbeaten and tortured with every kind of technique. They used cattle prods. Mybody swelled so much that my pants tore when I tried to put them on, but theydidn't give me new ones.

He points out the lumps on his wrists, a scar near his hairline, and a swelling on his shoulder as evidence of his treatment. Lukhar Jam also recalls other kindsof intimidation and attempted persuasion:

Once, the head of the region's Public Security Bureau told me, "We are all very grateful to the country and the Party because they provide us with everything . . . so how shameful you are if you act against the country and the Party. And your shameless action is against the law of karma" [the Buddhist principle of cause and effect]. I told him, "I grew up under the care of my parents. My parents worked with their hands and feet and lived their lives to take care of their children, and the government and the country haven't done anything for me. Sowhy should I be grateful to them?" So he got angry and yanked at my clothes,saying, "These clothes are a product of the Party and the country." I told him that they were from India. Then I was beaten severely, and my hands were cuffed and they kicked my body.

After less than a month in Shigatse, security-bureau officers took Lukhar Jam to Seitru, the state-security detention facility in the northeastern suburbs of Lhasa,where he was asked the same questions and gave the same answers, but wasnot ill-treated. By April 7, 1993, he had been taken back to Qinghai Province, toa detention center in Tsongkhakhar (Ping'an), the primarily Chinese capital of Haidong prefecture. There, in early July (although there are discrepancies among dates in official documents related to this case), he was formally arrested and moved to a special isolated and very secure detention center inDelinkha, the capital of Haixi Mongolian and Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture.Haixi is the site of military bases, and access to it is highly restricted.

Lukhar Jam objected on several counts to the more than four-month interval between his detention and formal arrest, saying it exceeded the legal limits. Healso objected to the officials' failure to notify his family that he was being held. Furthermore, he said, "When my elder brother came to find me in Tsongkhakhar, the officials lied and told him I wasn't there anymore. It's a day'stravel by bus from home to Xining, and another day by train to Tsongkhakhar."Interrogation by state security, procurators, and court officials continued for close to another year, until May 22, 1994. During that time, Lukhar Jam wasconsistently angered by the anti-Tibetan bias of many of his interrogators. Herecalled, "When Mr. Shu, a Chinese official from state security, was interviewing me, he got very angry when I answered his questions in Tibetan. He said, 'In China, everyone should use Chinese. It is unnecessary to speak Tibetan, and no one uses it. If you want to live in this country, you must use our nationallanguage.' "

According to court papers dated July 28, 1994, the Haixi Intermediate People's Court sentenced Lukhar Jam to an eight-year term for "espionage" and tenmore years for "organizing and leading a counterrevolutionary clique." If he"showed a good attitude," according to Lukhar Jam, "they'd take a year off my sentence." Indeed, his sentence was commuted to seventeen years.

According to the Haixi Procuratorate, he and his alleged co-conspirators,Tsegon Gyal and Namlo Yak, had "delivered four items of unlawful correspondence" out of the fourteen Lukhar Jam had brought back from India, and "purchased and collected over thirty volumes of books and materials, suchas surveys of eight autonomous prefectures or counties" in Qinghai Provinceand eight pieces of "classified or top-secret documents and data." Evidence presented to the court by the procuratorate consisted of two statistical volumes, one about the national economy and the other about the educational system. In addition, Lukhar Jam was accused of having been sent to Qinghai by an "external espionage organization" (i.e. the Tibetan government-in-exile), to"deliver correspondence and gather intelligence." "On numerous occasions,"the document continued, "he disseminated reactionary opinions concerning such subjects as Tibetan independence."

Tsegon Gyal and Namlo Yak received prison terms of sixteen and twelve years respectively for their petitions to the Dalai Lama, and for helping to collect confidential information. In addition, the formation of the "dare-to-die" group had, according to the verdict, "incited . . . splittism and endangered national security." Although the three denied the charges of spying and promoting independence, and pointed out that many of the books they had were available in local stores, their arguments were labeled "false and in contradiction with the law." A fourth detainee, Shawo Dondrup, who was less than eighteen years old when detained, reportedly was released by the procuracy after nine months indetention. It took until November 1997 for the details of the trials and the harshsentences to reach humanitarian organizations. By then, two months had passed since the Qinghai Higher People's Court had concluded that the sentences imposed on Namlo Yak and Tsegon Gyal went beyond the allowable punishments. Their terms were reduced to four and six years respectively, andon November 14, 1997, Namlo Yak was released. He arrived in Dharamsala in March 1999.

As far as Lukhar Jam is concerned, the legal system in China is a travesty. There were, he said, three problems with his interrogation and trial:

It was not public; I was not given the right to hire a lawyer-the Chinese didn't follow their own laws. About two months before the trial started, I was interrogated by procuracy officials. Then they gave me a paper explaining the charges and told me to prepare for the trial. I told them I didn't know the system and asked for a lawyer. Officials from the procuracy and from the court denied that I had the right to have a lawyer. For another month, court officials questioned me. Then the judges and officials came and gave me another paper. Even on the day of the trial I was asking for a lawyer. The third problem was that the Chinese kept me in prison over a year beforethey tried me. After the trial I stayed in the same cell in the detention center for another two years. My friends didn't leave their cells for years. When I left Amdo,they were still in the detention center. We all should have been moved to a prison after we were sentenced.

Lukhar Jam's description of the trial and appeal process provided evidence of other violations of Chinese law:

During the trial, they took off our handcuffs, but two soldiers held each of us.There were three Qinghai Province Public Security Bureau officials present,four court officers from Haixi prefecture, and three from the procuracy. Oneperson was a Muslim; all the rest were Chinese. All the documents were in Chinese. There were two or three journalists. They never published anything about the trial. They just cursed us [in print]; this proves they are notindependent. They do whatever the government tells them. After the chargeswere read out by the procuracy, the chief judge asked if we agreed. That was our chance to speak. The judges listened to us, then took a ten- or twenty-minute break. It was late in the day when they told us the sentence, but they didn't give us the papers for ten days. The chief judge had come to see meabout a week before the trial and told me I would get the heaviest sentence-so I know they decided the sentences before the trial.

We all refused to accept the verdict. I wrote a letter in Tibetan-I do know Chinese, but I know Tibetan better so I wrote it in Tibetan. I didn't have anyone to help me. I wrote that I came to Tibet to meet my parents and family and that I never came to spy and that I was never the head of a counterrevolutionary group. I said that the books they said were state secrets could be found everywhere. It took over two years for the high court to decide the appeal. That's against the law, too.

The trial was videotaped but not to show to the public. Sometimes when I was interrogated, they videotaped me and they took pictures of me in detention.They interviewed me after the trial. They said, "You got the heaviest sentence among the prisoners in Amdo. Do you still think Tibet will get freedom?" I toldthem I didn't feel like answering and it was useless for me to answer, but then I told them, "Freedom for Tibet is the right of the Tibetans and historically there is no right for China to rule Tibet. . . . Without freedom, our great religion andculture have been declining and Tibet's environment has been badlydamaged."

By the time of the trial, in July 1994, Lukhar Jam-who had entered prison healthy-was seriously ill. In Shigatse the beatings and poor food had takentheir toll, but it was not until his transfer to Delinkha that the deteriorationaccelerated. On April 29, 1995, when he was finally released on medical parole, his weight was down to thirty-nine kilograms (approximately eighty-seven pounds). He was still thin when we interviewed him in August 1998. His abdomen had become painfully distended, diagnosed initially as resulting froma liver ailment, and he had developed feifushui, a lung disorder. When LukharJam left prison, he could not stand, much less walk, unaided.

Detention-center officials had ignored Lukhar Jam's many requests for medical treatment and had even placed his friend Namlo Yak in leg irons for a week forwriting several letters of complaint to prison authorities. But nothing changed until a routine inspection of the facility by high-ranking provincial officials.During cell inspection, prisoners were required to line up by twos. When LukharJam did not respond to the demand, one official removed his quilt and blanket."He was shocked at how thin my legs were. I think that the higher officials talked to the prison officials, because they started to treat me right away."

Lukhar Jam's condition steadily worsened over the next five to six months, and officials moved to release him, fearing he might die in prison. The process ofobtaining his release degenerated into a bureaucratic nightmare. The chief of the detention center, who announced that he would refuse to take responsibility if Lukhar Jam died in prison, asked the prefecture to approve the release. At the same time, the chief, with the assistance of the center's health committee,forwarded to the Haixi prefecture hospital and the Tibetan-Mongolian hospital the agreement he obtained from the provincial high court to underwrite medical expenses. After prefectural hospital personnel put Lukhar Jam through a battery of tests, they told the high court that Lukhar Jam was beyond help. The medical advisors to the court, upon evaluating the hospital's report, concurred. LukharJam said he later heard that the thinking was that even if he went to the best hospital and the government spent 20-40,000 renminbi (ca. U.S.$2,850-5,700), there was no hope.

Despite that conclusion, during the month before he was released, cadres and soldiers at the detention center began to take Lukhar Jam to the hospital for day treatment. While there, he was shackled to the bed by one hand while he received intravenous glucose in the other arm. At night, even though he was thought to be infectious, he was returned to the overcrowded cell he shared with five or six others. Finally, the head of the high court, representatives from the intermediate court, and procuracy officials all decided that he had to be released.

Once the decision was made, Lukhar Jam was asked if family members would act as guarantors. When he replied yes, they were notified that he was ill and that they should come to the center and bring money to cover his medical expenses. According to Lukhar Jam, "Relatives came and went. Mostly they cried. And they wouldn't bring my mother. They were afraid of what my appearance might do to her." His older brother and his uncle, however, stayed a month, buying him food he could digest, meeting his medical-related expenses,and eventually arranging for a few face-to-face visits. Initially, Lukhar Jam hadonly been able to see them from a distance, on his way to or from the hospital.

Finally, Lukhar Jam felt he was improving and told his relatives to tell the detention center they had run out of money and were going home. In fact, at that point all they had left was 900 renminbi (U.S.$125), barely enough to cover another two or three days of treatment. They had already spent some 18,000 renminbi (U.S.$2,570). For two weeks, Lukhar Jam pretended to get worse. Butthe detention center refused to cover his expenses, treatment was terminated,and his condition again actually deteriorated. At that point, his family was notified to come and take him home. Two uncles agreed to post 6,000 renminbi(U.S.$950) and to sign and thumbprint a six-point agreement. Lukhar Jam remembered four of the points:

• Should he die, the family will accept his death and tell others that it had to do with the illness itself and not the treatment he received in prison.

• Should he recover, the family will hand him over to prison authorities when so ordered.

• Should a guarantor die, his heirs (probably his children) will be responsible for upholding the agreement. Therefore, before he can be released,each guarantor must provide to the authorities a complete list of family assets.

• The family will pay all medical expenses.Lukhar

Jam also had to sign and thumbprint a second six-point agreement of which

he recalled three requirements:

• to inform the authorities of any contacts with the Tibetan government-in- exile;

• in case of recovery, to come on time if ordered to appear by the court, the Public Security Bureau or the detention center;

• should he have to go to any hospital in any place, to report the incident to the PSB. Within a week after Lukhar Jam arrived home in April 1995, he started treatmentat Chabcha People's Hospital. But after two to three months, when his condition was rediagnosed as an intestinal blockage, and not a liver ailment, he opted for traditional treatment at Hainan Prefecture Tibetan Hospital, which was, according to Lukhar Jam, "the best in Chabcha, and was famous all over Qinghai."

The staff was very friendly. They

had to send reports to the Chabcha security department

because it was responsible for me. I was still appealing mysentence, so

the security department sent the reports to the high court and tothe State

Security Bureau. After about a year, I was almost recovered, but thestaff

never mentioned that I didn't have a problem or that I was being treated

as an outpatient. They always

said my health was not good, and they kept a bedfor me even when I wasn't

there. I was a patient almost to the day I left Amdo.The hospital reduced

the charges so we only had to pay 4,000-5,000 renminbi(U.S.$570-710).

Once out of the detention center, Lukhar Jam used other subterfuge methods to keep his condition from detention-center officials. From almost the moment he returned home, he had had to report his thoughts to the PSB on a weekly basis,and he was questioned whenever something concerning Tibet occurred in Qinghai. "It was a big problem," Lukhar Jam said.

At first an officer came to the hospital. Later on, when I went to the PSB station, I didn't even wash my face. I wanted to look ill. They asked about Tibetanindependence and putting up posters and about whether I knew this or thatperson. They suggested I work with them. I had to say something to pleasethem, so I said I would contact them when I knew something. I was frightened; Ididn't want to go back to the detention center; I was sure I would die if I did. And there was no way my family could pay 70,000-80,000 renminbi (U.S.$1,000-1,425) again. A lot of people from where I lived-high lamas, rich people,officials-had given money because they knew I was a political prisoner andbecause of the feeling of being Tibetan. So I knew I had to be careful about howI answered.

Time was beginning to run out, and Lukhar Jam knew it. By midsummer 1997, word had leaked that he had regained his health. Furthermore, his appeal still had not been heard. (He found out later that it was heard in absentia on August13, 1997 and turned down.) In June 1997, three years after sentencing, his two friends found guarantors and were released temporarily:

They were under surveillance and I was under even heavier surveillance, but for a month we managed to do some business together. . . . Then in August,much to their surprise, they were re-arrested. They had come to believe theywould not have to go back to prison. They even had expected to get their jobs back and they had relaxed their guard. They thought at worst they would be called to court for an appeal hearing. I was convinced they would be returned to prison but would only have to serve half their terms.

While Lukhar Jam was in Xining, prepared to flee if necessary, he telephoned his friends, only to hear that they been arrested and that they had been beaten for not telling where he was hiding. As soon as he heard the news, Lukhar Jamput his carefully worked-out plan into action. He had been staying in a guesthouse owned by a friend. On August 20, Lukhar Jam told the friend that he was leaving for Lanzhou for medical treatment and would be back soon. As evidence of his intentions, Lukhar Jam left most of his belongings at the guesthouse but managed to carry with him documents related to his case. When Hainan and Qinghai security came to arrest him in Xining, his friend repeatedthe story. The officers waited a few days in Xining and then headed forLanzhou.

By that time, Lukhar Jam had already reached Golmud, the largest city in western Qinghai, and from there traveled to Lhasa by bus. He reached Lhasa inforty-eight hours. In both Golmud and Lhasa, Lukhar Jam did not dare stay in hotels; instead he stayed with friends. The police later caught up with many ofthose who had helped him; and his uncles, as guarantors, were interrogatedand fined heavily.

According to Lukhar Jam, the physical hardships of his flight and the need to beg money from friends in preparation for the winter trek across the Himalayas were not his biggest problems. It was the threat of being caught again. "That was on my mind. If I was caught, two years would be added to my sentence. Imight even be executed because I was carrying all the documents related to mycase."

He arrived back in Dharamsala on November 20, 1997. When we interviewed him in August 1998, he was struggling to find a way to earn a living, make new friends, and advance his education, and also with how he could contribute tothe Tibetan cause. It is clear that he could no longer even attempt to go back across the border. He had already decided that one solution might be to use his personal experience to focus international attention on how China's government circumvents its own laws in order to solidify its political control.