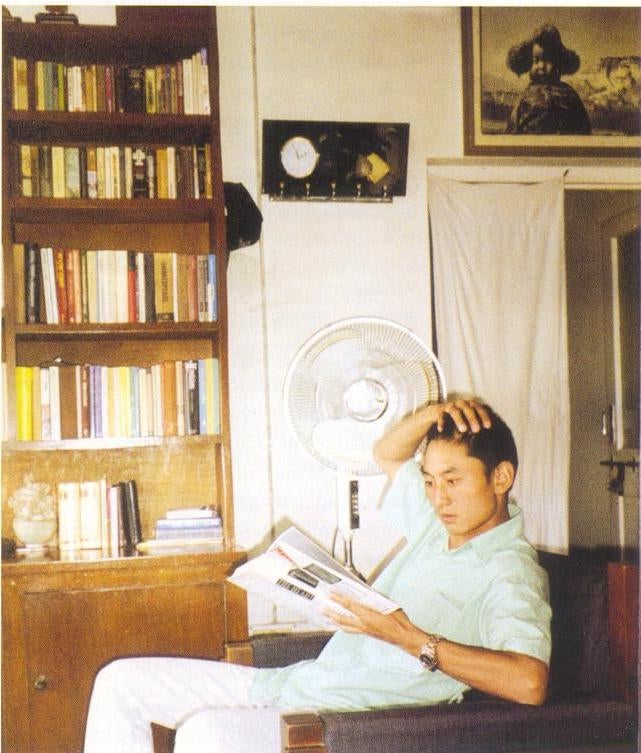

When we met him in New Delhi, his future was bleak. At twenty-one, he has no full-time job and survives on handouts and odd jobs, including some translation work for Taiwanese visitors. He studies Japanese when he can and wants to go to college, but he can't afford it. He is extremely thin from tuberculosis and looks much younger than he is. Intense, feisty, often angry, sometimes depressed, Jamyang has little hope for the future.

Jamyang left Amdo for the first time in July 1993, thus missing the competitive examinations that determine acceptance to Chinese universities. He reached Dharamsala, the seat of the Tibetan government-in-exile, in January 1994, a month before his seventeenth birthday. He stayed just over a year, until April 20, 1995, then tried to go back to Amdo because he was homesick. Shortly after he crossed the border, he was picked up by police, and he spent the next year and two months in various detention centers, police stations, and prisons-five in all. He finally got back home in June 1996, but after both he and his family were severely harassed, Jamyang returned to India in August of the same year.

One of ten children -- seven boys and three girls -- Jamyang grew up in Taktsang, a Tibetan village in Hualong Hui Autonomous County, in Haidong prefecture. His family still lives there, growing wheat, barley, and mustard, as well as raising sheep and horses and some sixty or seventy yak. There are few opportunities for Tibetans other than farming in this poor agricultural county, and population pressure is reducing the land available for cultivation. Once predominantly Tibetan, by 1994 the county was more than 50 percent Hui Muslim, 23 percent Chinese and only 21 percent Tibetan. Foreigners must obtain special permission to visit Hualong; it is not easily granted.

Jamyang is the only member of the family to complete high school, skipping some grades along the way; in fact, he is the only one who finished elementary school while still living in Amdo. He left home because the area he is from has no facilities for furthering a Tibetan education. The lack of any meaningful opportunity for schooling in Tibetan language and culture is often cited by parents as a reason for temporarily leaving their children in India, where the Tibetan government-in-exile maintains extensive, accessible educational facilities. The Chinese-government school, although a mixed-nationalities school, was not only far away and expensive, it was not welcoming to Tibetans#. "There were lots of Muslims and very few Tibetans at the school and the Han and the Muslims sometimes beat up on the Tibetans," Jamyang says. "But ever since I was little, I have never been afraid to fight."

Unlike Jamyang's two younger brothers, who went to India in April 1998 with their parents' blessing and what financial support they were able to muster, Jamyang left home without telling his family and without a passport. He actually escaped from school, telling his plans to only a few friends, who relayed the information to his parents.

It was a freezing but relatively uneventful group trip across the border into Nepal, and from there to Dharamsala. During his stay in India, Jamyang was enrolled in the Bir school, a facility where older arrivals in India could study English and Tibetan literature. At the time he was there, most students stayed for about three years, although they could remain even longer. Jamyang estimates that all of his study time in India added up to perhaps six months. After fifteen months in India, his youth, homesickness, intermittent hospitalizations (apparently for tuberculosis), and what he perceived as his poor Tibetan-he speaks the Xining dialect-drove Jamyang to turn back home.

Jamyang's trip back to Tibet was a nightmare, marked by his arrest and detention, the callousness of his treatment, and attempts by the Chinese to recruit him as an agent.

Jamyang had decided to pretend he was Han-he speaks fluent Chinese, could pass as a Han, and had even chosen a Chinese name. He had his first run-in with the Public Security Bureau (PSB)-the Chinese police-almost as soon as he crossed the border into the Tibet Autonomous Region. At his first stop, a restaurant, four policemen (none of whom identified themselves as PSB officers) asked where he was from. "Lhasa," he said. When they asked for i.d., Jamyang said he had traveled from Lhartse in a truck and lost it on his way. At that point, he was handcuffed and transported to the PSB office in Kyirong for interrogation. Police officers there told him they knew he was not from Lhasa but had crossed the border on his way from India. When he disagreed, two officers drove him back the way he had come, stopping after about an hour at a Tibetan house. An old man answered the policeman's knock, and said that he had seen Jamyang come from the direction of the border. Jamyang shouted that the man must be mentally incompetent, and received a punch in the mouth from one of the officers. The party then returned to the Kyirong police station.

Two Chinese and two Tibetan police officers, three of whom were in uniform, took Jamyang into an office, unlocked his handcuffs, and without saying a word began to beat and kick him. They forced him to squat with his arms extended, a brick placed on each thigh, and one at the back of each knee. One of the Tibetan policemen, "a good man," Jamyang said, punched him several times, then told the others to leave him alone. But while he was still in that position, the deputy head of the Kyirong PSB, a Chinese man named Wang, entered the office and took charge. He announced in Chinese that Jamyang was very strong and he, Wang, was going to teach him a lesson. Jamyang still has scars on his back from the beating Wang administered with a piece of spoon-shaped metal-the kind you use to remove dishes from a Chinese stove. Wang told Jamyang that he knew who he was and where he was from. He repeated that Jamyang was very strong, since he still was not crying, but told him that it was better to confess everything. Jamyang replied, "If the police know who I am and where I'm from, they don't have to beat me." He was beaten nevertheless, from midnight until about 4 a.m. Finally he was taken to another room and placed in a prone position between two beds, one arm cuffed to each bed, and one policeman asleep in each bed. The cuffs were the kind that tighten with the slightest movement, and are extremely painful.

Early the following morning, Jamyang was moved to the Kyirong County Detention Center. For the next eighteen days, he was questioned about the Tibetan Youth Congress (the Tibetan exile organization most insistent on independence rather than autonomy for Tibet); the Tibetan government-in-exile and the operations of its security office in Dharamsala; his own alleged spy training, including where it had taken place, his code name, and his secret number. He was not beaten. Jamyang told us, "Chinese policemen aren't highly educated and they asked me a lot of questions about Dharamsala. I told them I didn't know anything about Dharamsala-that they probably knew more than me because they have their own agents there." Between interrogations, Jamyang managed through a system of knocks on the wall to establish communication with other detainees.

While Jamyang was in the detention center, the owner of the restaurant where he had been apprehended came to visit and bring food. Jamyang asked if he would burn some books that he had left in the trash can in the restaurant. Jamyang told the owner they were Buddhist texts, although they were actually documents carried from India, among them Guidelines for Future Tibet's Polity and the Basic Features of its Constitution,# and My Land and My People, the Dalai Lama's autobiography. As they were in Tibetan script, the other man couldn't read them. However, after the restaurant owner told a policeman about the books, the restaurant owner was brought to the detention center and beaten severely. Jamyang said, "When I heard him crying out in pain, I felt pity and I confessed. I shouted out in Chinese, 'I came from India. I'm a Tibetan!,' and the beating stopped."

The next stop for Jamyang, in June 1995,

was the Nyari Detention Center in Shigatse, where for six months and fifteen

days, along with the four others in his cell, he did little but wait and

respond to interrogation handled by State Security Bureau personnel. The

interrogation was low-key and polite, and the questioning centered on his

alleged spying and "subversive" habits:

"You're young. You seem to know a lot.

Your Chinese is very good. Where were you trained?"

"I read a lot."

"What do you read?"

"I read Wei Jingsheng's Democratic China."

"What is in there? What does it say?"

"It says, 'China needs democracy.' "

Three or four times, Jamyang wrote letters on the back of cigarette wrappers-a common prison substitute for paper-to the head of the Shigatse PSB, a Tibetan named Palden. Jamyang's message was simple, "If I've done something, try me; if not, immediately release me according to the law. If you don't, you're breaking your own law." No one paid any attention. Life, Jamyang says, was bad in Nyari. He had the usual food complaints. Breakfast was tea and one mantou, an unsweetened coarse bun; lunch, filthy rice noodles infested with insects and pebbles, and a few vegetables; supper, two mantou and vegetable soup. He was freezing in a long-sleeved cotton shirt and jeans with holes."You could see my ass." Prisoners whose family members knew where they were being held could send food and clothes; Jamyang's family never knew his whereabouts. He was beaten just once at Nyari, when he protested the beating of an old monk by shouting, "You have no right to beat an old monk. You are here to guard and teach us." For this, a Tibetan named Tsering Gochen (Big Head) hit Jamyang several times on his back with a club. Jamyang was ordered to work just twice, loading vegetables that other prisoners had grown onto a truck. As far as he could tell, those held in Nyari did not have an extraordinary workload.

At Nyari and at other detention facilities, those privileged inmates who delivered meals often delivered the latest news. Jamyang learned, among other things, that Ngawang Choephel, an ethnomusicologist, later accused of spying and sentenced to an eighteen-year prison term, was also in Nyari. He also learned that on July 12 in the middle of the night, thirty-seven monks from Tashilhunpo monastery were brought to Nyari after they disrupted a meeting called by regional-level officials to denounce Chadrel Rinpoche, the monastery's abbot, for his part in the search for the reincarnation of the Panchen Lama, the second holiest figure in Tibetan Buddhism. (Chadrel Rinpoche is now serving a six-year term in a secret facility in Sichuan province.)

According to Jamyang, because he was so contentious-a trait that may have helped him cope and survive-the authorities thought he was a spy. On December 15, 1995, cuffed to the sides of a truck, he was transferred to Seitru, a state security facility in the northeastern suburbs of Lhasa for political detainees awaiting sentencing (many of them would later receive long sentences). Jamyang has few complaints about his more than four months in Seitru. He and the other prisoners, some seventeen to twenty in all, were held in individual cells. Work consisted of moving night soil to the vegetable fields, and this afforded the men an opportunity to talk, although discreetly, under the watchful eyes of the guards.

The next leg of Jamyang's journey brought him closer to home. Two officers from the Qinghai Province PSB came to Seitru, asked a few questions and then escorted him in cuffs back to his home province. On the bus to Golmud and the train from Golmud to Xining (the provincial capital), they announced to fellow passengers that Jamyang was a murderer. At provincial headquarters, the PSB's first division, charged with political security, took over. Jamyang's handcuffs came off. He was supplied with new clothes, then taken to an upscale Muslim restaurant. Some ten or twelve officers, all high officials in Western-style clothes, according to Jamyang, were his companions. His best bet, they told him, was cooperation. "You're young; you're intelligent. You'll be able to travel to other countries." After the meal, the conversation continued as they rode out of the city in a flashy Japanese car with tinted glass. "I'm a student," Jamyang said to them. "How could I cooperate?" Remembering this exchange, Jamyang says he was laughing inside at their proposal; he knew they were trying to trick him.

At first, the car followed the route to his village, but about halfway there, it turned onto an unfamiliar road. Jamyang did not know that he was headed for Ledu county, an overwhelmingly Han area with a small Tibetan presence, just east of Xining-specifically, to the Ledu County Detention Center.

For nine days Jamyang was severely brutalized by the seventeen "ordinary criminals" who shared his cell in Ledu. "By then," he said, "I was weak and thin. I fought with them but I couldn't compete. I was sometimes beaten more than once a day. The 'cell boss' ordered the beatings when the police told him to. There were ten in the nine days. And sometimes I was ordered to bend over and the others pushed into my ass with their hands." On each of the nine days, two Xining public security officers, the same two each time (one named Qi Yude), tried to convert him. When Jamyang told them about the beatings, they replied, "This is normal; this is how it is. But if you cooperate, you'll have a house, a car."

Without warning, on the tenth day, Jamyang was taken by car, a filthy one this time, to another restaurant, this one in Ping'an, the Sinicized and industrialized capital of Haidong prefecture. During a lunch with seven or eight officers from Xining headquarters (some of whom he had eaten with before), he was told he would be going home, but with conditions attached. He could tell his family, but no one else, that he had been in India. He could tell no one, including his family, about his experiences with bureau officers and with state security agents. Nor could he contact foreigners; and he was forbidden to travel outside his home county without police permission. After a six-month probationary period, his status would be reevaluated. He received nothing in writing. In fact, during his entire ordeal, Jamyang was never given or shown any official document. He was never allowed to read what had been written during interrogation sessions, but was made to sign the transcripts.

Jamyang was driven to Bayan, Hualong's county seat. From there he made his way to his own village of Taktsang. He had borrowed five renminbi from the police for a ticket home, but when he met fellow villagers in Bayan, he hitched a ride on their tractor. By then his family already knew he had left India and was headed home, although they had no idea when he was arriving or that he had been caught and incarcerated. He finally arrived home in June of 1996-fourteen months after his departure from India. "When I got home, I looked like a beggar. My parents were sad to see what I looked like. And I was shocked at their appearance: they looked a lot older. My mother hardly looked human, and my father looked decrepit. They told me they had made pilgrimages to monasteries and had prayed every day."

Jamyang expected to remain with his family, but a series of compromising incidents, including occasional, irregular, and very public police "visits," made him realize how difficult it was going to be for him to stay.

I was home two days when a car with a light and a siren going arrived at my parents' house. I was taken to the Hualong County Public Security Bureau. It seems they didn't have a file on me, so I was pulled in for interrogation-the whole thing all over again. But they didn't try to turn me. They really wanted to know about India. They kept me one night.

A second incident involved an unexpected interrogation while Jamyang was in Bayan. Soon after Jamyang arrived home, his neighbors came to see him, as did many of his classmates, some from far away. A number of them gave him money. He used a portion to pay for more than twenty days of treatment and medication at the Hualong Hui Bayan County People's Hospital, and for his stay at a hotel close to the facility. "I thought I had heart problems," he said. The trouble turned out to be malnourishment. "Every time I went to the hospital, I was followed by an unmarked police car. One time, they pulled over and told me to get in. I did. They took me to a guest house." This time, officers from the Qinghai State Security Bureau interviewed him. They showed him photographs of several people-head shots, profiles, body shots-and asked if he had ever seen any of them before. He hadn't. "I still don't know who they are," he said. The officers then took his photograph, told him that if he would cooperate he would be welcome in Xining, and sent him back to where he had been staying.

The third and final incident came during a trip to a relative's house in Hainan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, a predominately Tibetan locale, and a day's bus ride from Jamyang's home. As required, Jamyang had reported his travel plan to the police. His first stop was the Hainan Prefecture Minorities Teacher Training Institute, where he spoke discreetly about India and Tibetan independence to some students he knew from his own schooldays. He also distributed some twenty-five pictures of Gendun Choekyi Nyima, the child recognized by the Dalai Lama as the reincarnation of the Panchen Lama. A picture of the boy had been given to Jamyang when he returned home and he had managed to duplicate it.

At midnight, state security officers from Hainan prefecture showed up at Jamyang's relative's house. "They knew me; I didn't know them. They wanted to know why I had come. They kept me about half an hour." After his relative told household members and others what had happened, Jamyang realized that staying could jeopardize his relative's relations with his danwei, the work or residence unit that controls most aspects of an individual's existence, including livelihood, housing, and social welfare benefits. And when he returned to his own home, he realized that his family was already, as he put it, "broken and suffering." The authorities often came unannounced to the house to ask about his activities, and he knew that if he stayed the whole situation would become "crueler." He thought about buying a gun and taking revenge on the police in Shigatse for holding him illegally, and on the police in Xining for allowing him to be brutalized, but, knowing the Dalai Lama would not welcome him if he went through with his plan, he talked himself out of it.

By the beginning of August 1996, two months after he had arrived home, Jamyang was ready to leave. He was well set up, he said. The necessary help, money, transport, and introductions had all been arranged through "ordinary" folk and through some in positions of influence. By October, Jamyang was back in Dharamsala where his weakened condition kept him in the hospital for six months.

Jamyang is restless and rootless in India.

He's now too old to be a student in Dharamsala; he's already had the one

chance for an education he's entitled to under Tibetan government-in-exile

auspices. He's still sick, and taking medication for tuberculosis. Some

days, Jamyang is ready to go home whatever the consequences.