| ||

Live Updates from Field Teams, September 18, 2005

Update from Team 6, south of Kandahar, 3:30 PM:: We are just returning from Spin Boldak, which lies to the southeast of Kandahar. We went to two stations there. There weren't too many problems. There were some people there who were trying to vote twice; they had their cards and were trying to vote, but the polling staff didn't let them. The main issue down here seems to be low turnout. It seems like a lot of people didn't come out to vote. There hasn't been any violence, but it may be that people stayed away from the polls because of fears they would be attacked by insurgent forces.  Man voting in Spin Boldak (c) 2005 Reuters Update from Sam Zarifi, west of Kabul, 3:15 PM:: We're in Paghman district, which lies just to the west of Kabul. It's very quiet. Nothing much is going on here. There's another hour of voting left, but there are only a couple of people still voting. There are posters of one single candidate all around--the militia leader Abdul Rabb al Rasul Sayyaf, who is from this district. There is also still some campaigning going on: trucks and vans driving around with pictures of Sayyaf, but otherwise it's very quiet.  Woman voting in Kabul (c) 2005 Reuters Update from Team 3 in Ghazni, 2:30 PM:: We’re received confirmation of an attack on a polling site this morning. A grenade was reportedly tossed at a site in Andar district, and one polling worker was injured. Update from Team 4, Kapisa province 2:20 PM:: Just a quick update to say that we've seen a few more under-age voters since the last update. There are definitely some children voting out here. It seems like this is a recurrent problem in some of the villages here, which raises the possibility of there being a fraudulent scheme of some sort. Update from Sam Zarifi, near Kabul, 2:10 PM:: I've been talking by telephone with all the teams, as well as to other election monitoring teams. It's difficult to say anything conclusive at this point, but it seems like there is lower turnout than the last election [the presidential election in October 2004]. Yet it's hard to conclude anything: there are more polling stations and booths than last time, which could lead to shorter lines. Still, there is a sense that there have been fewer voters. Also, the mood is different than during last year's election. There isn't the same excitement as there was last year; people are not as excited about voting or about the election. Of course, this could be good thing--perhaps people are getting used to the process, and acting like voting is just a normal thing. But it could also be a reflection of voter disappointment or cynicism about the candidates and the process. We've heard a lot of cynicism from people in the lead-up to these polls. Our teams have witnessed a lot of complications with the ballot, some of which were expected. The complexity of the ballot has turned out to be a major issue. Many people here are illiterate and simply couldn't handle the ballots. There are pictures and symbols on the ballots, so that people who can't read know which candidate is supposed to be the one they want (that is, if they've chosen someone). But the photos and the symbols on the ballot papers are very small, and some people can't find their candidates. And there are other confusions. So, regardless of what the specific regulations are, election staff have had to help voters in many areas. This is especially true in the case of women voters. In a few instances, our teams have seen election workers, when helping voters, point to certain candidates, and tell voters to select them. Obviously, this raises concerns about the process. This doesn't seem from our monitoring to be a systematic problem--at least not yet--but it is a cause for concern.  Women voters in Kandahar lining up to vote earlier this morning. (c) 2005 Reuters Update from Team 1, Jawzjan province, 1:00 PM: We're in the village of Sayedabad, in Jawzjan district, in northern Afghanistan, to the west of Mazar-e Sharif. Things are going well generally, but a lot of women don't know how to vote. In a few places, we saw women voters who showed up at the polls and had no idea what to do. They came in, and they asked the polling workers, "What do we do now?" They didn't know how to vote, and didn't have any idea for who to vote for, so they were asking the polling staff, "Who should we vote for?" There was a lot of confusion: some of the poll workers were telling them, "You have to decide." But in some cases, the election workers were indicating to the women voters who to vote for. It's difficult to know what to say about this--these women voters just don't know what to do. Another issue that caused us some concern is that there was a candidate agent who showed up at a site, with a whole set of women, and was telling them who to vote for, and they were going in and voting as they were told. But that was just one case. The real problem was these women voters who didn't know how to vote, or who hadn't any idea whom to vote for. There was a lot of confusion among them. They simple didn't know what they were doing or whom they were voting for. Update from Team 4, Kapisa province 12:20 PM:: Some good news and some bad. In some places here things have been going well. But there have been some problems, especially out in the villages. There is a lot of illiteracy out here, and we don't know if everyone really understands what's going on with the ballot papers. There's a lot of confusion among the illiterate voters, not knowing who to vote for. And we saw a major problem at one polling station, in the town of Pul-e Mirwais. Some children were apparently voting. We were leaving the site there, on the way to another polling site, and we saw about 7 or 8 kids--boys--they were only about 10 or 12 years old. They had all voted, and had ink on their fingers [the indelible ink to prevent fraudulent multiple voting]. We asked them, "Did you vote?" And they said, "Yes, we voted." So we asked the eldest among them, "How old are you?" And he said he was fourteen. But he wasn't even fourteen. He looked younger than that. And he was the oldest of them. The rest were about 10 years old. We'll keep an eye out for this in other villages. We have a real worry about this problem. Even the manager of that polling station, where the kids voted, he was only about 18 years old, if that. The polling staff out here, in these rural areas, are not very reliable. There are some serious problems with voters' knowledge in these villages. These people out here, in these villages, they're illiterate, and they don't really know what's going on with the ballot papers. So they ask the polling staff to help them vote. They go up to the polling staff, and they say, "I want to vote for so-and-so." And then the staff points to a line on the ballot and says, "This is the guy." Then the voters vote for that person. But there is a problem here. They might tell the illiterate voters to vote for someone else, whomever they want to. There's a real concern out here that some of these polling staff might be connected to certain candidates. So they might just point to the candidate they support, and say, "This is the guy you want to vote for." Some voters here have complained to us that the polling staff are linked with local candidates, or local commanders or warlords. If these polling staff are really linked to certain candidates, they might tell the voters to vote for their candidate, while the voter thinks he's voting for someone else. That's the worry here. We're going to look into this a bit more and see if there are specific problems. Of course, polling staff are allowed to help voters. But since there are some concerns about the impartiality of polling staff, and since some of the villagers here can't read the ballots here--it's an issue. An Afghan man marking his ballot this morning at a polling site in Herat. (c) 2005 Reuters News Update:: Two rockets hit a U.N. compound in Kabul this morning, but no serious casualties have been reported. According to U.N. staff we spoke with earlier today, the U.N. compound on Jalalabad road was hit--one of the main offices of the Joint Electoral Management Body, the Afghan-U.N. body overseeing the election. Reuters reports that "two rockets were fired into a U.N. compound near an election centre in Kabul shortly after polls opened. Only one exploded, slightly wounding an Afghan worker, an election official said." (All Human Rights Watch staff are safe and accounted for.) Update from Sam Zarifi, north of Kabul, 11:10 AM: Well, we've done the round robin of everyone, talked to all our teams, and called the Afghan Human Rights Commission and other domestic observation teams, and one thing that's coming out is that it seems there are far fewer voters this time than last year--a much lower voter turnout [than during last year's presidential poll]. We'll see the final results later, but certainly so far, everywhere we've been, and with all the people we've talked to, it seems like there are fewer people voting than last year. Update from Team 6, Daman district, Kandahar, 11:00 AM: We are, at the moment, in Daman district, outside Kandahar. We went to one of the polling sites for the Kuchis. [The nomadic Kuchi population of Afghanistan, most of whom live in tents and shepherd goats and sheep, have been allocated 10 seats in the lower house of parliament, and are supposed to vote at special sites set up around the country.] Nobody was there--only 8 Kuchis voted. We asked the polling staff and they said that only 8 people came and voted. Now we are going to another rural district, where there is another polling site for Kuchis, and along the way we'll check some other sites as well. The traveling is slow: the roads are almost empty, but every two or three hundred meters around Kandahar, you are stopped and searched by Afghan military or police. They check our observer cards, they look in the trunk, look at us, and then they let us go. Outside the city, it's deserted, there is no one to be seen. Just some kids running about, nothing else really, no one else. All the shops are closed, there are just some fruit sellers along the road, but no one else really. A lot of people have already voted. Otherwise, it's been pretty quiet and there hasn't been any violence we've heard about. From a member of Team 3 in Ghazni province, 9:40 AM: I'm in the center of Ghazni, and I just came in from the village of Khoja Omari, which is about an hour outside the city. There weren't any major problems out there. The voters came in to the polling stations and voted, so things were going smoothly there. Now I'm in the center of Ghazni city. I'm coming out of the municipal offices, where there is a major polling station. A lot of people are coming in, and there's a problem with the crowds. The election workers are not very good at controlling the crowds. People are all trying to rush in, and the staff cannot keep the people in line. It happened in a few stations; it's disorganized. But in general, things are going well. Security is alright, and everything is ok. There are a lot of Afghan military police out, Afghan police, American military, and ISAF [International Security Assistance Force, mostly NATO troops]. The other problem is that everywhere we go, there are a lot of candidates' agents [accredited candidate representatives]. They're all over the place. When I asked some of the election officials about this, they said: "We can't ask them to leave the polling stations. There are hundreds of candidates with agents, and every one of these agents wants to enter the sites, and since every candidate has one or two agents, there are a lot of them." [The candidate agents are allowed under election rules to monitor polling sites, but they are supposed to uphold codes of conduct, and not interfere with the voting process.] They're not doing anything wrong, but they make a crowd inside the polling site. For example, they stand near the polling boxes, and they stand right at the table, and when voters come to the table, the agents crowd around, looking at their voting card, looking at them have their hands marked with ink. [When voting, voters have to show their voting cards and then have their hands marked with indelible ink, which prevents fraudulent multiple voting.] And so they make it difficult for the voters to get by. But they're not making any big problems. They're not saying anything to the voters here, and they're not allowed to go near the stations where the voters actually vote. From Team 6 in Kandahar, 8:30 AM: Kandahar city is completely shut down to traffic. There are no cars on the roads, except for those with special passes. When the polls opened at 6 AM, there weren't many voters out. I was waiting around, and the turnout was very low for a while, but things have turned around, and now there are a lot of people coming out. Throughout the city, there's now a lot of activity. A lot of people are now walking to the polls, and there are now a lot of people on the roads. On the main Shar-e Now road here [New City Road], there are lots of men walking to and from the polls. But the weather is very hot--very, very hot. The sun is beating down on our heads. So, the polls opened pretty early. Before the voting started, the poll workers opened up the ballot boxes, which were empty, and showed them to all the observers--showed that they were empty--and then they put on these plastic ties to hold the box tops down. There are hundreds of men inside the polling sites--quite a lot of men, but the problem is that there are a lot of candidates agents too [accredited candidate representatives], and they are voting too, so that's one of the reasons it's very crowded. Here in the city, there are about 10 or 12 voting desks in each site. The voters go in, show their voter cards and sign in, and then get their two ballots: one for parliament and one for the local provincial council. They have their hands marked with indelible ink, so that they can't go and vote again, if they've somehow gotten another voting card. The voters cast two votes: one vote for a parliamentary candidate, to represent this province, Kandahar, in the lower house of parliament; and another one for a candidate to represent them in the Kandahar provincial council. [Later, each of the provincial councils will elect representatives to go serve in Kabul in the upper house of parliament, the house of elders.] We weren't allowed into the women sites, but there weren't any women there anyway. We couldn't see any women going up to the polls when we first got here. But now a few women have started showing up, about 10 or 15 women came, they were brought in a van. There are no cars allowed generally, but some cars have passes. There was one problem we saw at some of the sites. In a few cases, there were 2 or 3 guys voting together, in the booths, but the vote is supposed to be secret. So some of the observers pointed this out, that people are supposed to vote alone, and the poll workers told the guys to vote one by one, alone. The sun is very hot here and it's unfortunate these voters have to walk in the sun to the polls. The sun is really beating down and it's going to be a very hot day. From Team 2 in Mazar-e Sharif, 7:15 AM We're at a school where some women are voting. The voting started about 10 minutes ago. There were some problems with the different candidates' agents: there were so many of them, that no one could fit into the station. (Note: candidates' agents are accredited representatives of different candidates, who are allowed into the voting sites.) But they've sorted that out-now the voting has begun. Some of the women don't know how to vote--they're asking, "Who are we supposed to vote for? How many people can we vote for?" They don't know who to vote for, and they don't know that they can only cast a single vote. But some other women are talking to them and trying to explain it. Otherwise, so far, there are no major problems. We're going to head out to some of the villages outside the city. . . . 6:30 AM Polls officially opened about a half hour ago, but the stations haven't opened in most places. There are small lines of voters starting to line up at the sites which haven't opened. From Sam: Well, I'm west of Charikar, a few hours north of Kabul. We're off-roading. We're trying to get up to this polling site in a village, up on the mountain west of Charikar, and the roads are pretty bad. The town looks very nice, if we can ever get to it. Like Charikar, it has a lot of terraced houses, where the roof of each house butts into the floor of the next one up the mountain. Very beautiful. There are goats and sheep everywhere-in other words, a pretty wealthy town. But the roads aren't so good. We're hanging on the road like a limpet on a rock, though really, we're hardly on a road. In fact, I think the road may have just ended. Indeed, we've reached the end of the road. I don't think this can really be called a road anymore. It's more like a goat path. In short, the road we're on is really not suited for vehicular traffic. Ok, we're getting out, to walk. We just ran into a very large ditch. . . or rather, somewhere between a ditch and a canyon. A "culvert," I guess you would call it. Now a young shepherd boy is leading us to the school. . . it's slightly embarrassing that we're being led by a young shepherd boy, but there you have it. This is a really beautiful valley: you can see all Charikar valley, which is very lush and green-lots of houses with fruit trees, very beautiful. . . . Ok, we've reached the little town of Khaja Saran. The voting is taking place in this combination mosque-and-school. It's a really mountainous town - reasonably prosperous, a lot of stone houses. The voting just started, about a half hour ago, and it's actually almost done, since this isn't really a big town. There's a whole group of men who voted, who are now just hanging out, outside the polls, talking. Inside the polling station, there are four cardboard voting boxes. There's a soldier voting now, and a really, really, really very old man, very bent over, filling out his ballot. There are also a bunch of candidates' agents hanging out--monitors for the candidates and political parties. Right outside the school is an old Soviet APC-an armored personnel carrier-all gutted out. The turret of the thing has been ripped off and is now being used as a step to walk into the school, an Afghan case of beating swords into plowshares. TopKabul, September 17, 2005

From Sam Zarifi: There´s a full moon over Kabul tonight, without a cloud in the sky. The elections begin tomorrow, and the tension is palpable. Checkpoints have been erected around Kabul and other major cities to keep out most traffic, helicopters fly overhead, and unfortunately, insurgents have stepped up their attacks. A police patrol was attacked just outside Kabul today, killing a deputy police chief. We´re all set for the election. And most everyone in Kabul last night who had access to a television were glued to their sets to watch the beginning of the most exciting poll here—no, not the parliamentary elections, but the debut of the Afghan edition of American Idol. (More on this other “election" in later posts.) Human Rights Watch teams have fanned across most of the country. Before the teams left, we met again today to go over their proposed routes and to establish security and communication protocols. As I mentioned in a previous post, we have a great group of monitors; bright university students with a real passion for human rights. They are a remarkably resourceful and resilient group. But I admit I suddenly had a case of cold feet at the last minute and considered pulling the plug on their travels. The idea that anything could happen to them because of our work filled me with dread. I´ve already spoken to them in depth, at least three times, about our security protocols, and I could sense their bemusement at my suddenly maternal ways. As a reminder, you can read our real-time dispatches on this site tomorrow, starting at 8:30 AM Kabul time (12:00 AM New York; 5:00 London). I must say, the fact we can file these dispatches at all is simply incredible.

Through Afghanistan´s nascent mobile system and Human Rights Watch´s

satellite telephones, all linked with Human Rights Watch´s headquarters

in New York, we´re going to be providing real-time information to you

from far corners of Afghanistan. You will be hearing about a one time

historical event, from the ground, as it happens. Our recent background report on the election was written by our researcher John Sifton, who arrived here in August, along with another star researcher for Human Rights Watch, Charmain Mohamed, who normally works in southeast Asia. Charmain and John interviewed scores of candidates in the lead-up to the elections. Kabul, September 16, 2005

From Sam Zarifi: The shoe mender was adamant that I tell "the foreigners" about his disappointment with Afghanistan's central government and his resentment that his life had not materially improved since U.S. forces removed the Taliban four years ago. He used an old-fashioned word in Dari for "foreigners," farangis, literally, "the Frankish," a reference to the memory of the Crusader hordes who descended rudely upon the Muslim world 900 years ago. Because I can speak Dari and look like I could be Afghan, many Afghans treat me as a compatriot, or at least as a cousin from a neighboring country. It is a privilege, and usually a great help in our research, but it sometimes makes it very difficult to maintain the distance and objectivity necessary for carrying out our work. Today, in the face of this man's vehemence, I wanted to retreat behind a wall of foreignness. I had asked him about the upcoming election, but he didn't really care to discuss it. "I will not vote for any of them," he said. "I voted last year for Karzai, and I hoped that things would get better, but now I can barely make enough money for my family. None of the candidates are trustworthy and they do not care about us, just about their own success." He ran a shoe-mending business by the side of the street to try to feed his family, who had returned from refuge in Iran last year. Prices were going up, and police were extorting protection money out of him. For this man, the omnipresent campaign posters around Kabul are simply background noise. "Tell the farangis that we need work, not these politicians," he said. While many Afghans are more excited about the election than this, most simply want their government to address the tremendous problems of their daily lives. It has now been nearly four years since U.S. forces ousted the Taliban-almost as long as the Taliban ruled Kabul. After four years of a government supported by the combined might of the international community, many Afghans expect to see more tangible improvement in their lives. They are grateful to international donors, but they are also growing impatient with the slow pace of economic development, the reemergence of nasty figures from the not-so-distant past, and the iniquities caused by the country's drug trade. They recognize the international community here as a guarantor of the peace and provider of crucial assistance, but there is also a fear that the mysterious farangis who are now in Kabul may leave just as suddenly as they arrived, leaving the job half-done. Most foreigners in Kabul stay in guesthouses, establishments that fall somewhere between a private residence and a small hotel. For upcoming elections, all the guest houses-a new one seems to spring up every day-have filled up with hundreds of temporary U.N. and diplomatic staff, journalists, aid workers and of course, human rights monitors. The guest houses take on the air of summer camp, full of people reuniting with others that they know through six degrees of destruction: from Kabul, Baghdad, Sarajevo, Kosovo, Chechnya, Nepal and back to Kabul. A group known as "the vulture club." The guesthouses vary widely; some have lovely gardens, some have elaborate swimming pools (which no one uses), some have little more than bare rooms with running water. What they all have in common is that they are hidden behind high walls, with a sentry post in front. Afghans are, by and large, limited to the serving staff. Being in a guest house in Kabul can feel very much like not being in Kabul. You can get a decent steak and fries, tortellini with goat cheese, and even French wine. You can get away from Afghanistan. The shoe mender, like many other Afghans, was worried that the foreigners would leave Afghanistan without helping fix any of the underlying problems, deserting the Afghan people to their poverty and their rapacious leaders. He may be right. I'm embarrassed to admit that I craved the sanctuary of our guesthouse after nearly three hours with the shoe mender, and a trip to the local police station to discuss the problem of extortion by the police. (Several other small vendors from the area had also complained about this once they heard their colleague discussing it with a foreigner.) These elections are a test for the legitimacy and resilience of the new Afghan government, but they are also a test of the commitment of the international community to providing crucial assistance to Afghanistan. Will we declare the elections a historic moment, applaud our own philanthropy, and then pack up and leave? That is a real fear here. We even talked about it over a lovely dinner at the guesthouse, behind our high walls and armed sentries. As we were eating, I noticed a plaque on the wall of the guesthouse's garden. It marked the memory of Marla Ruzicka, a 28-year-old aid worker who was killed by terrorists in Iraq exactly five months ago. Marla had dedicated herself to gaining compensation for innocent people who had been hurt as a result of U.S. military action, first in Afghanistan, and then in Iraq. She was a bubbly California blonde, prone to using the word "dude," a keen and unstoppable force of nature. In the months after the Taliban's fall, she was known as the Queen of Kabul, for her role at the center of social life for the growing number of foreigners here. She was even more famous for spending a lot of time outside the walls, trying to help those who had suffered. She was a farangi, no doubt about it, but she was committed to providing assistance where it was most needed. I wish I could have introduced the angry shoe mender of eastern Kabul to her, to blunt his cynicism and raise his hopes. There could be no better role model for the international community here. ************************************ [Note: On Sunday, election day, Human Rights Watch teams will be sending hourly updates to this site from across Afghanistan. Log in to this page starting Sunday at 8:30 AM (12:00 AM New York; 5:00 AM London), and check for updates throughout the day.] Update from the Afghanistan Team: Two days to go until election day. The official campaigning period is over, and Kabul was relatively quiet today, but unfortunate news arrived from outside the city. On Thursday night, in the southern province of Helmand, a parliamentary candidate named Abdul Hadi was shot and killed, reportedly by Taliban forces. And we learned that another women candidate was shot and wounded on Wednesday in Nuristan. The Pajhwok Afghan News Agency also reported two cases of suspected arson of polling sites, including a mosque in Paktika (on the border with Pakistan) and a school in Logar (just south of Kabul). Voters and candidates remain tense, especially in south and southeastern areas. Most everyone hopes that Afghan police and international forces can lessen the number of insurgent attacks on election day. But in the south and southeast, it's likely a significant number of fearful voters are not going to make it to the polls. In the rest of the country, the polling should go more smoothly, though there are concerns about local militia commanders and strongmen intimidating voters in rural areas. Our monitoring teams have set out to some of the more remote areas, to visit sites on Sunday and access security conditions and look for cases of intimidation. Meanwhile, logistical preparations for the election continue apace. Afghan election authorities are distributing ballots, ballot boxes and other elections materials to the thousands of sites around the country. In most places, this is a relatively simple affair: workers just load up trucks with materials and set off for villages.  Afghan workers loading ballot papers onto a truck in Kabul September 16, 2005. (c) Reuters/Ahmad Massod 2005 Afghanistan is a mountainous country, and there are some areas that trucks and cars simply cannot reach. But election authorities have thought ahead, and hired asses and camels to acts as "mobile polling stations" for some of the more remote areas.  Afghan men preparing asses loaded with mobile polling stations in the eastern province of Badakhshan, September 16, 2005. (c) Reuters 2005 One election observer called these "ballot-carrying jackasses." And jackasses are exactly what one needs to get out to rocky high-altitude districts, like some of the northeastern districts of Badakhshan province, which form the "panhandle" that sticks out to the northeast of the country. Human Rights Watch won't be able to follow the mobile voting stations out to the most remote provinces, but we'll keep an eye out for some of the mobile teams in the mountains north of Kabul. Remember to follow this page on Sunday for hourly updates from the teams. TopKabul, September 15, 2005

From: Sam Zarifi Today began with broken hardware and ended with broken hearts. This morning in Kabul, we released a major report exposing how warlord intimidation and insurgent attacks are undermining Afghanistan's election process. The first order of the day was to print out the just-finalized PDF of the 27-page report, which involved an epic struggle with faulty internet connections, incompatible software and a particularly recalcitrant printer. We released our report at noon Kabul time, and it was immediately covered in many media outlets, including the BBC, Reuters, AFP and Associated Press. My day finally ended at a Kabul theatre, watching a performance of "Romeo and Juliet," not in Shakespearean English but in Dari, one of the main local languages here. First, about our report: "Afghanistan on the Eve of Parliamentary and Provincial Elections." My first job today was to download the finalized report, format it for Afghan computers and printers, print it out, and then drive around town to deliver copies. Human Rights Watch reports generally go out to a wide list of journalists and policymakers. But to ensure that they read them, it's crucial that we put actual paper copies squarely in people's hands, which gives our readers an opportunity to ask questions and discuss our findings. Things went badly from the start. The internet café that we usually use experienced a total system failure, so I had to scramble to find another one. Finding internet cafés in Kabul these days isn't easy. Ever since a suicide bomber attacked the main internet café we used to frequent, such establishments have moved to basements or the backs of buildings. These locations are great for security, but they are hell for mobile phone connections. In Kabul, you need to carry two mobile phones for each of Afghanistan's competing phone networks, since one network is often down. Once I found an internet café, I discovered that both of my mobile phones had enough reception to pick up incoming calls, but not enough to actually carry on a conversation. As I was printing out the report, I kept jumping out of my seat to answer the phone. Then, after the printer fiasco, I began a madcap dash around town to deliver copies of the report. Given our tight schedule, I had to do my best to be pleasant, answer questions, and move on to the next delivery. Our report's findings-that violence and intimidation are hurting the election process-contradict some of the conventional wisdom here, in particular, that the elections are a panacea for all of Afghanistan's ills. So I had to spend much of the day countering the official spin, and presenting the facts we had gathered from hundreds of interviews with candidates, voters and observers around the country. My next step was to pick up money transferred by wire, so we could help support our small team of local monitors, who will be fanning out across the country on election day. Western Union's main office in Kabul was closed, so I had to dash across town to the other location, which is located deep in the chaotic moneychangers' bazaar. With a brick-sized wad of dollars in my pocket, I returned in time to meet our monitoring team-a group of young men and women, mostly university students, committed to human rights and the rule of law, and willing to put up with difficult roads and security risks in order to monitor polling spots around the country. We discussed what they need to look for on election day: among other things, evidence of tampering with the ballots or ballot boxes, and signs of interference by political parties or candidates' agents. Our session was repeatedly interrupted by phone calls from journalists interested in discussing our report. After two hours, our monitors went on their ways, armed with keen intelligence, notebooks, mobile phones and youthful enthusiasm. It will be quite a challenge coordinating their activities and gathering the information they will collect on election day. Finally, just as I was about to keel over from a scarce diet of sour-cherry juice and cigarettes, I received a call from a friend, inviting me to attend a final performance of "Romeo and Juliet." Yes, that's right: Shakespeare in Kabul. Needless to say, I accepted the invitation. Tonight's performance was the last in a series of Shakespeare plays presented here in Dari. The productions, which have received assistance from U.S. and European artists, have been presented here since late August. The play was held in the open air in the courtyard of a former prime minister's house.  Romeo woos Juliet © Human Rights Watch 2005 It was a charming performance. All the performers, except Juliet, were men. The actors in drag added a note of historical Shakespearean authenticity. It was a short performance, just one hour. Since the performers didn't have enough time to rehearse the entire play, a narrator simply recounted the rest of the story after the point at which the two young lovers exchanged vows of love. It was a novel approach, but nonetheless clearly moving for both the audience and the troupe.  Romeo and Juliet exchange vows of commitment (c) Human Rights Watch As a theme, the director had chosen to emphasize the folly of needless violence and the threat it posed to innocent youth, a notion that clearly resonates in today's Afghanistan.  Juliet prepares to drink potion in order to reunite with Romeo © Human Rights Watch 2005 When the dying Mercutio finally declares "a pox upon both your houses," it was not just a curse on the Capulets and Montagues, but a condemnation of those who take up arms to destroy love and beauty. As the audience stood up to applause, I wondered how many of them were thinking about young friends and relatives they had lost over the past 25 years of conflict here, and about the future. Would all the deaths of the past be enough to force reconciliation upon leaders blinded by years of violence, as happened with the warring families of Romeo and Juliet? Elections are near, and time will tell. TopPaghman, September 14, 2005

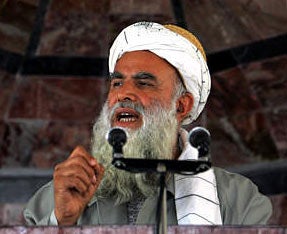

From: Sam Zarifi Today I found myself face to face with Abdul Rabb al-Rasul Sayyaf , one of Afghanistan's most notorious warlords, and he was complaining about Human Rights Watch. Sayyaf was one of the leading mujahideen commanders in the fight against the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan, and the leader of one of Afghanistan's meanest militias during the ruinous civil war that followed the Soviets' withdrawal. Human Rights Watch has documented serious abuses by his forces in the mid-1990s, and yet more abuses by his forces after his return to prominence after the fall of the Taliban. We have repeatedly called for Sayyaf to be investigated and prosecuted for his actions, along with other mujahideen, communist, and Taliban human rights abusers who have plagued this country.  Abdul Rabb al-Rasul Sayyaf © Reuters 2005 Sayyaf was holding a campaign rally near Kabul in support of his bid for parliament. Candidates can be disqualified for maintaining links to armed factions. So I went to the rally to monitor whether repeated allegations that Sayyaf continued to field a sizable militia were correct. The short answer is: yes, indeed. Sayyaf held the rally at a new mosque he's building in his home district of Paghman, a lovely, mountainous area west of Kabul. The most prominent feature on the mosque-dwarfing even the lone minaret-was a giant campaign poster of Sayyaf, resplendent in his grey-white bushy beard, bearing the legend "Your Mujahid Brother." And directly atop the poster was a machine-gun emplacement manned by a pair of gentlemen in camouflage pants who did not appear to be members of the Afghan National Army or Police.  Gunman stand guard atop the mosque in which Sayyaf's rally was held. The campaign billboard describes Sayyaf as "Your Mujahid Brother." (c) Human Rights Watch Also notable among the 1,500 or so Sayyaf supporters were a significant number of fans sporting Kalashnikovs, along with a pickup truck bristling with gun barrels. I, for one, did not know you could fit 15 heavily armed men on the back of a pickup. After his speech, which focused on the role of Islam in Afghanistan's future government, Sayyaf left the mosque and held an impromptu press conference. I found myself in the scrum of reporters, amazed to be about three feet from a man whom I had previously mostly heard about from the quivering mouths of victims traumatized by his forces. Just as I was thinking about that, I heard a foreign reporter ask Sayyaf what he thought of claims by Human Rights Watch that he was a war criminal and major human rights abuser. My hair stood on end, my blood ran cold, my sweat beaded on my already sweaty forehead, and I only barely fought the urge to duck to the ground. All because I was dying to hear his response-although I really did not want to die just to hear it. Well, the answer just about floored me. Here's how Reuters reported the Sayyaf's response: "If there was some proof that I had committed some crimes, then I will be responsible for that, but I am sure that we have worked for the freedom of the country. We have struggled against crimes and didn't commit crimes. These are only the claims of those who are against us and against the freedom of this country." Sayyaf said he supported the punishment of criminals, but investigations would need to be done impartially. "We want a pure and clear and sincere investigation," he said. "We want the facts to be uncovered. We want the facts to be well-known to the nation." So there you have it: Sayyaf has now publicly stated his support for an accountability process. This is a major development, one that I believe is due at least in part to Human Rights Watch's reporting and advocacy, in particular our report on atrocities in Kabul during the civil war in 1992-93. We now see various Afghan military figures criticizing one another's human rights records and calling for an accountability process. Which is exactly what we want. On the other hand, our fear is that once Sayyaf is elected to parliament-which looks like a sure bet-he and other implicated warlord types will push for some kind of immunity from prosecution for themselves-even as they pursue their former enemies. The Afghan government and election authorities had the chance to sideline figures with links to armed factions from the elections, but they didn't use it. Now, we all have to wait to see how these figures behave once elected. TopKabul, September 13, 2005

From: Sam Zarifi Everyone in Kabul is talking about one parliamentary candidate – "the woman in yellow". Nobody knows what her views are on access to education or on land reform. But she is undoubtedly one of the best known parliamentary candidates in Kabul. Amongst the door, and downright glowering, campaign photos plastered on every conceivable surface, her picture stands out for her obvious youth, her sweet smile, and her bright yellow veil which artistically frames, but does not quite cover, her hair. Frankly, her campaign picture looks more like the cover of a glossy magazine, or an advertisement for a demure Bollywood movie, than a political poster. It is now being sold on the streets for up to $5. The entire country, right now, is awash in posters. There are nearly 5,800 candidates running for parliamentary and provincial council and they have all put posters up. And billboards. And the campaign business cards that candidates hand out like candy. Some potential voters collect the cards the way young boys collect baseball cards. From: Sam Zarifi Charmain is standing in the midday sun and dust for about an hour in this Pashtun village in southern Samangan, a region in the high, dry plains of northern Afghanistan. She was waiting for me to finish interviews with a group of irate Pashtun grey-beards. She had prematurely finished her interviews with a group of women shortly after a man had come in to tell them not to say anything that would cause trouble. Charmain had gathered this group of women (seven and counting) to discuss their views on the upcoming parliamentary and provincial elections. They told her they were registered to vote, they were prepared to vote—and they were going to vote exactly as they were told by their husbands and fathers. Top |

RSS Feed:

Previous Posts:

September 17, 2005

September 16, 2005 September 15, 2005 September 14, 2005 September 13, 2005 September 12, 2005

Recent Work on Afghanistan from

Human Rights Watch:

Afghanistan: Campaigning Against Fear

Afghanistan on the Eve of Parliamentary and Provincial Elections Campaigning against

Fear: Women’s Participation in Afghanistan's 2005 Elections |

|

Home | Introduction | Afghanistan | More on Asia |  | ||