The case against Pinochet in Chile involves nineteen victims of a military unit known as the "Caravan of Death." Acting on the direct authority of Pinochet, the unit visited prisons the length of the country in late 1973, removing political detainees and summarily executing them.

On December 1, 2000, taking a landmark step toward ending impunity for crimes against humanity, Judge Juan Guzmán Tapia indicted Pinochet for these crimes, ordering that he be placed under house arrest. The Santiago Appeals Court threw out the charges on the grounds that the judge had failed to question Pinochet, a requirement under Chilean law before a person may be charged with a criminal offense, and the Supreme Court confirmed the ruling. Yet Judge Guzman pressed on with the case, questioning Pinochet at his Santiago home on January 23, 2001, and re-indicting him on January 29.

Several months before, in August 2000, the Chilean Supreme Court confirmed that Pinochet, a lifetime senator, should be stripped of his parliamentary immunity (a process known in Spanish as desafuero), and stand trial. Pinochet's immunity as a senator-for-life had previously protected the former dictator from prosecution for this or any other crime during his bloody rule.

Andean countries researcher Sebastian Brett, who is based in Santiago, reports:

Monday, January 29, 2001. General Pinochet has again been indicted by Judge Juan Guzman, who ordered him placed under house arrest.

Tuesday, January 23, 2001. This morning, more than three years after the first criminal complaint was filed against him, General Pinochet was formally questioned for the first time about the human rights crimes committed by his government. Conducted by Judge Juan Guzman, the interview took place in Pinochet's Santiago residence and lasted thirty minutes. Pinochet, who was accompanied by a legal advisor, is reported to have denied ordering the murder of the seventy-five victims of the "Caravan of Death," but to have admitted dispatching the military unit that killed them. According to El Mercurio, he said that he was not aware of the killings even afterwards, and that it was not his job but that of the local military commanders to investigate them.

Now that Pinochet has been questioned, the road is open for Judge Guzman to charge him. The judge may, however, rule instead that Pinochet is mentally unfit to stand trial. Whatever his decision, it will be appealed to the Santiago Appeals Court, with the final ruling to be made by the Supreme Court in the coming weeks. The appellate court's decision will focus on the results of the medical tests performed ten days ago.

Dr. Luis Fornazzari, the neurologist appointed as an observer by the legal team representing the victims, has claimed that the findings on which the examining doctors all agreed were subsequently altered to make Pinochet's condition appear more serious. Dr. Fornazzari refused to sign the report of the findings. The Chilean Medical-Legal Service, which was responsible for the examination, says the final results took into account results not available before Dr. Fornazzari left Chile for Canada, where he resides. The dispute is likely to continue and may become a key issue in the case.

Sunday, January 21, 2001. Two weeks after the military delivered to President Lagos their shattering report admitting that the bodies of 151 murdered prisoners were dumped in the ocean and lakes of Chile, a newspaper has finally published the armed forces' introduction to their findings. It makes President Lagos' public recognition of the armed forces' contribution to reconciliation seem premature and misplaced. There is no apology to the nation, or the victims, for the unspeakable atrocities baldly documented in the pages that follow. The description of the context in which they were committed is as inaccurate and misleading as earlier rationalizations. The explanation given for the military's conduct is the same as that given in its defiant response to the Rettig Commission's report a full decade ago.

"Most of the disappearances" says the introduction, published in today's La Tercera, "took place after September 1973 and over the following months, a period in which the country was experiencing a critical state of internal convulsion, provoking acts, behavior, and victims typical of irregular armed conflict. This situation placed limits on the institutions' ability to clarify the cases which were the subject matter of the task before them."

A critical state of internal convulsion? Reporting in 1991 on the immediate post-September 1973 situation, the government-sponsored Rettig Commission concluded that the armed forces were in full control of the country within a few days. As its report emphasizes, armed actions by supporters of the deposed government were "minimal." They were "irregular in terms of place, kind, and armaments used, uncoordinated and without the least chance of success, even at the local level."

The Chilean armed forces were not "provoked" by convulsion or armed conflict. In reality, their atrocities were committed against defenseless people, many of whom had given themselves up to the authorities in the mistaken belief that their army would treat them fairly. Yet, after a decade during which these facts have been known to every reader of the Rettig report, the military continues to shift the blame onto the deposed Allende government, with the introduction reiterating that "the events that led to the political violence [read human rights violations] must never be repeated in our country" (our italics).

The armed forces' report contains no critique of military doctrine, and no mention of the Geneva Conventions, which would have been applicable had there really been an armed conflict. The military's logic, after nine months of negotiations in the Mesa, is hardly different from General Pinochet's scathing attack on Rettig back in 1991: "from the point of view of any serious armed institution, when one is faced by a situation of war, the only possible objective is total victory."

In an interview in Sunday's El Mercurio, army chief Ricardo Izurieta was asked if there were now two armies in Chile: the army of the 1970s which abused human rights, and today's force. "That's a fallacy," Izurieta replied. "Whoever says that does not know the army. The army of Chile is one, and one alone. The army that lived through the experience of the military government is the same one as today's. It just had to live through different times, that's all. Throughout our history, the commanders have had a common thought, to act in benefit of the country. It's also true that the army is made up of human beings and human beings make mistakes, and can be wrong."

Mistakes? Although the armed forces say they are now teaching recruits about human rights, one can only wonder if they are telling them the truth about the events of the 1970s. Until they do so, Chileans will still have reason to fear their armed forces.

Friday, January 12, 2001. General Pinochet completed his third and last day of medical testing. Citing Pinochet's advanced age and fatigue from the testing, Judge Juan Guzmán postponed his interrogation, rescheduling it from January 15 to January 23. It is only after the interrogation is complete that Pinochet can be reindicted for his involvement in human rights atrocities.

Yesterday, the number of lawsuits pertaining to human rights abuses committed under Pinochet that Judge Guzmáan is investigating rose to 205, as the human rights group Codepu filed the case of a teacher shot dead in 1984.

Wednesday, January 10, 2001. Medical testing of General Pinochet began today. Judge Juan Guzmán had rescheduled the tests after Pinochet fail to show up for testing on Sunday and Monday.

Sunday, January 7, 2001. Today, defying judicial orders, General Pinochet has failed to appear for medical tests scheduled to take place at a Santiago military hospital. His lawyers say that Pinochet objects to the fact that urine and blood tests are to be conducted at a civilian hospital.

The tests were ordered to establish whether the former dictator is mentally fit to stand trial.

Friday, January 5, 2001. This morning, the Chilean armed forces delivered a report on the fate of persons "disappeared" under the rule of General Pinochet to President Ricardo Lagos. The report, agreed to under the auspices of last year's "Mesa de Dialogo," is supposed to include detailed information collected from members of the armed forces describing what happened to detainees.

In addition to the four branches of the Chilean armed forces, the Catholic Church, the Episcopal Church, the Jewish community, and other groups have been collecting such information to provide to Lagos today.

The family members of many victims of atrocities committed under Pinochet are still, decades later, unaware of how or when the victims died or where their bodies are located.

Tuesday, December 26, 2000. "Supreme Court: Medical Exams First" ("Suprema: Primero Exámenes Médicos") said the headlines today in Santiago's evening paper, La Segunda. The Supreme Court has reversed its own decision, one announced just six days ago, ordering Judge Juan Guzmán to question Pinochet within twenty days, with or without medical exams. Now the court is insisting that medical exams be performed first. With this development, the prospects of Pinochet facing criminal charges have dimmed considerably.

Judge Guzmán had fixed December 27 as the date for Pinochet's interrogation and January 22 for the medical exams. That timetable would have allowed plenty of time for Pinochet to be indicted and placed under arrest during the period between the interrogation and the exams. Pinochet's lawyers thus lodged an urgent appeal to prevent the interrogation. Although the Supreme Court formally rejected the appeal, the justices said they felt obliged to "clarify" the court's December 20 decision. Then, in a radical departure from that decision, they said that Judge Guzmán must ensure that the medical tests are carried out in twenty days, and that after this date he must question Pinochet.

Judge Guzmán had fixed December 27 as the date for Pinochet's interrogation and January 22 for the medical exams. That timetable would have allowed plenty of time for Pinochet to be indicted and placed under arrest during the period between the interrogation and the exams. Pinochet's lawyers thus lodged an urgent appeal to prevent the interrogation. Although the Supreme Court formally rejected the appeal, the justices said they felt obliged to "clarify" the court's December 20 decision. Then, in a radical departure from that decision, they said that Judge Guzmán must ensure that the medical tests are carried out in twenty days, and that after this date he must question Pinochet.

In essence, the clarification amounted to an acceptance of the defense appeal. But the ruling was still fraught with ambiguities. What if the tests were done within the time limit but the results were still not in by the time of the planned interrogation? Did the Supreme Court mean that the interrogation must proceed whatever the results of the tests?

That is not what members of Pinochet's defense team think. Their overriding goal is to prevent Pinochet from ever being charged, fingerprinted or arrested. They hope that Judge Guzmán will drop the prosecution once the results of the tests are known. But lawyers representing the victims of the Caravan of Death interpret Monday's decision to mean that the interrogation must proceed, and that the only change is in the order of the procedures to be followed. The legal wrangling over medical tests will doubtless continue.

Although no minister said so publicly, the Supreme Court decision must have come as a relief for President Lagos's government. A meeting of the National Security Council (called by Lagos in response to military pressure) is scheduled for January 2, to discuss national reconciliation measures. Three days later, the armed forces are due to provide the president with the results of their inquiries into the whereabouts or fate of the "disappeared," as agreed in the Mesa de Dialogo last June. With Pinochet in the dock, it would have been a tense moment for these events.

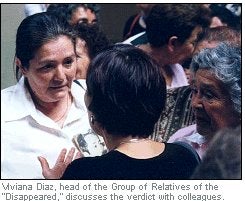

Wednesday, December 20, 2000. Today, in a decision that surprised and delighted the human rights movement here, the Supreme Court ruled that General Pinochet should be questioned within twenty days about his responsibility for ordering homicides and kidnapings after the military coup. Even more surprising, the court ordered the questioning to proceed whether or not medical examinations (required by law for defendants over 70) had been carried out. This ruling, stated in a single sentence, came at the conclusion of a 4-1 decision revoking Judge Juan Guzman's December 1 indictment of Pinochet, on grounds that he had failed to interview the general before charging him. The court's revocation of the indictment, upholding last Monday's Appeals Court ruling, was widely expected. But relatives of the "disappeared" present in the court building when the Supreme Court decision was announced were elated that the court also ordered Pinochet to be questioned.

Far from an afterthought, the ruling is crucial for several reasons. It means that the road now lies open for Judge Guzman to remedy the formal defects of the indictment, as neither the Appeals Court nor the Supreme Court have questioned the basis of the charges against Pinochet. Nor will Guzman have to wait until the results of the medical tests are available before reinstating the charges. It is thus quite possible that Guzman will interview and then charge Pinochet, and order his arrest, before the results of the medical tests are known. But Pinochet's defense will do everything possible to accelerate the medical tests in order to preempt the questioning and subsequent indictment. They want as little damage as possible to be done to Pinochet's prestige before he is, they hope, medically exempted from prosecution. Meanwhile, those pursuing justice against Pinochet remain keen to secure a conviction, though realists among them recognize that obtaining an indictment would itself carry enormously symbolic historical value.

Far from an afterthought, the ruling is crucial for several reasons. It means that the road now lies open for Judge Guzman to remedy the formal defects of the indictment, as neither the Appeals Court nor the Supreme Court have questioned the basis of the charges against Pinochet. Nor will Guzman have to wait until the results of the medical tests are available before reinstating the charges. It is thus quite possible that Guzman will interview and then charge Pinochet, and order his arrest, before the results of the medical tests are known. But Pinochet's defense will do everything possible to accelerate the medical tests in order to preempt the questioning and subsequent indictment. They want as little damage as possible to be done to Pinochet's prestige before he is, they hope, medically exempted from prosecution. Meanwhile, those pursuing justice against Pinochet remain keen to secure a conviction, though realists among them recognize that obtaining an indictment would itself carry enormously symbolic historical value.

The medical tests themselves are the subject of a legal battle. Although to escape prosecution under Chilean law a defendant must be insane, Pinochet's family have refused to assert this argument. Instead, his defense team claims that Pinochet's general medical condition makes him unfit to stand trial, an argument based on general due process grounds. Responding to these concerns, the Appeals Court has allowed the team of medical experts who examine Pinochet to include neurologists as well as the mandatory psychologists and psychiatrists. The experts, drawn by the appellate court from the Medical Legal Service (a branch of the Justice Ministry) and the University of Chile, are all civilians. In addition, Judge Guzman has allowed two outside experts (one for the defense and the other for the prosecution, both of them neurologists) to act as observers. Eventually, the results of the medical examinations should form part of the legal record in the case, which is in the public domain.

The major point in dispute concerns not the personnel or the procedures of the tests, but the venue where they will be carried out. Judge Guzman ruled at the beginning of November that the tests should be done in the Military Hospital, where Pinochet was then recovering from a bout of pneumonia. The prosecution attorneys appealed, arguing that the Military Hospital provided no guarantees of impartiality. The appeal was heard and rejected by the appellate court last Tuesday. This means that unless Judge Guzman changes his mind (and the prosecution attorneys were due to meet him today to urge him to select a a neutral venue), the tests will be carried out in the Military Hospital.

This institution, which is off-bounds to civilians without a pass, has been frequently used in the past as a refuge for military officers under prosecution for human rights violations. Pinochet's lawyers and medical advisers have met on several occasions in the hospital to plan his defense strategy. Moreover, the medical expert observing the tests on Pinochet is head of neurology at the Military Hospital, giving the Pinochet team an unfair advantage.

"It is highly unfortunate that both Judge Guzmán and the Appeals Court have deemed the Military Hospital a suitable place to carry out these crucial tests," said José Miguel Vivanco, executive director of Human Rights Watch's Americas division, in a press release today. "Even if the hospital plays fair, a decision in favor of Pinochet could be tainted by the public perception of bias, and justice would not be seen to have been done."

Monday, December 11, 2000. In a unanimous (3-0) decision, the Fifth Chamber of the Santiago Appeals Court granted a habeas corpus writ challenging Pinochet's indictment for ordering kidnappings and extrajudicial executions following the 1973 military coup. The prosecution team has appealed the ruling to the Supreme Court, which is expected to decide the case soon.

Friday, December 1, 2000. Judge Juan Guzman indicted Pinochet on charges of kidnapping today, asking that he be held under house arrest and ordering him to face trial in connection with the "disappearances" of prisoners in the first months of his 17-year dictatorship.

Tuesday, August 8, 2000. In a landmark ruling that renews one's confidence in the Chilean judiciary, the Supreme Court rejected the appeal by Senator Augusto Pinochet Ugarte against a lower court ruling stripping him of his parliamentary immunity. The verdict, in which an overwhelming majority (14-6) of the court upheld the lifting of immunity, means that Pinochet should now face trial for human rights violations committed at the start of his seventeen-year dictatorship. Although Chilean law sets a low threshold for the lifting of immunity (simply requiring that there be grounds for suspicion of involvement in crimes), only two such actions have been successful in the last thirty-five years. The verdict therefore has considerable legal and symbolic significance, even if Pinochet's health rules out eventual conviction for his crimes.

The ruling gives further impetus to the legal doctrine followed by the investigating judge Juan Guzman, that "disappearances" are not covered by Chile's amnesty law. It thus opens the way for additional prosecutions of military personnel responsible for crimes against humanity.

> > > PAST DISPATCHES FROM SANTIAGO

Legal issues in the case against Pinochet. The amnesty law decreed by the military government in 1978 bars the criminal prosecution of crimes committed from 1973-1978. But in cases of "disappearances," where the bodies of the victims have never been recovered, the Chilean courts have ruled that the victims must be considered still "disappeared," and hence victims of an ongoing crime. Accordingly, the amnesty law does not apply.

The bodies of nineteen of a total of seventy-two prisoners executed by the Caravan of Death have never been found. It is their cases that are now being prosecuted in the Chilean courts.

> > > THE PINOCHET PROSECUTION