Click here to explore the full 3D model

Human Rights Watch also reviewed information and statistics provided by the Ombudsperson's and Attorney General’s Offices about prison conditions and criminal investigations into the massacres, as well as judicial documents and a range of secondary sources, including reports by media outlets and Ecuadorian human rights groups. The police and the national prison authority, called the National Service for Comprehensive Attention for Detained Adults and Teenage Offenders (Servicio Nacional de Atención Integral a Personas Adultas Privadas de la Libertad y a Adolescentes Infract ores, SNAI), did not respond to requests for information.

In September 2021, President Guillermo Lasso declared several “states of emergency” in the country’s prisons that allowed his government to deploy soldiers to control detention facilities. In February 2022, the government adopted a “public policy” on rehabilitation, an action plan to bolster access to health, education, and other basic services for detainees and improve prison conditions.

In December 2021, President Lasso convened a commission of experts to reform the country’s prison system. On June 16, the commission released its final report concluding that prisons in Ecuador are “punishment warehouses” rather than centers for rehabilitation due to their punitive approach and lack of adequate programs. The experts said that overcrowding has increased violence in prisons, and pointed to reports of inhuman and degrading treatment and corruption by police and prison guards, as well as lack of access to medical care for detainees.

As of mid-July, Ecuador’s authorities had not convicted anyone for their part in the November killings or in any other prison massacres occurring in 2021. By December, the Office had opened 26 investigations into “violent events” occurring in prisons in 2021, including the massacres.

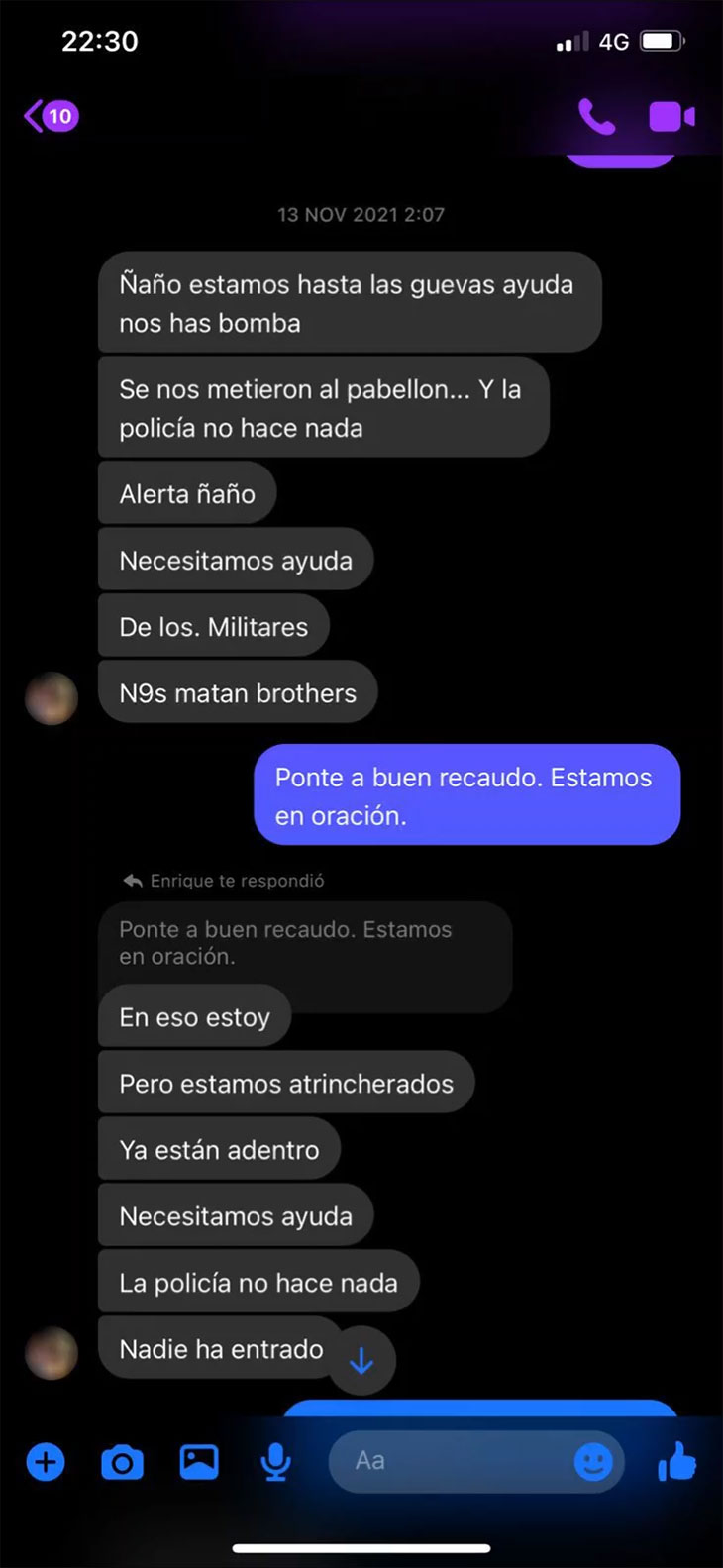

Screenshot of text messages from a detainee inside Littoral Penitentiary on the evening of November 13, 2021.

© Private

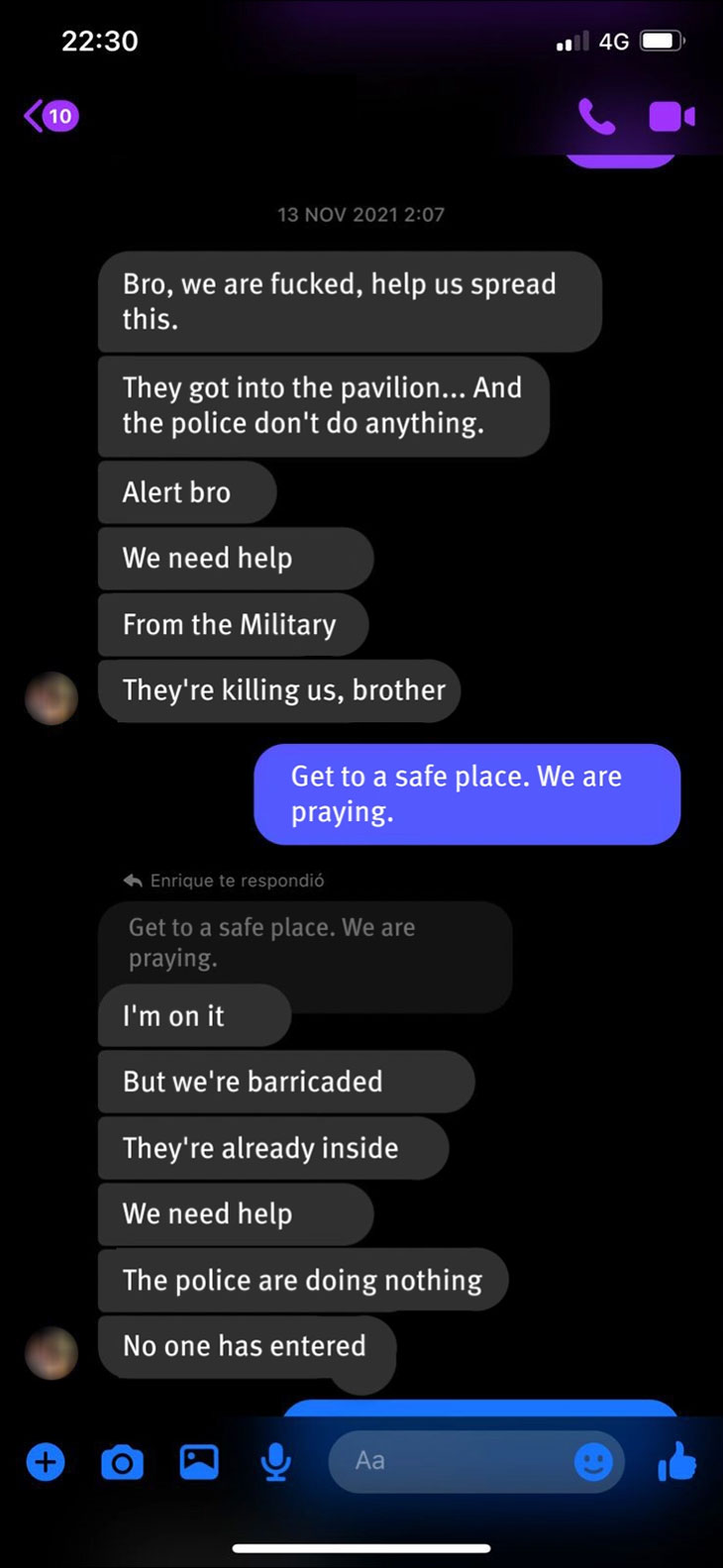

Screenshot of text messages from a detainee inside Littoral Penitentiary on the evening of November 13, 2021.

© Private

The prosecutor investigating the November massacre told Human Rights Watch that he was looking into who was responsible for the killings, as well as into whether any officials were responsible by “omission.” Ecuadorian authorities have provided inconsistent data on the number of people who died, with figures ranging between 63 and 68.

Several victims’ relatives told Human Rights Watch that they spent days trying to find out whether their loved ones had survived. Some only learned that they had been killed because their names were included in a list posted on a light post outside the prison. Others found out when a government official shouted the victims’ names outside the morgue. Relatives said they have not received any redress, compensation, or support from the government.

Prisons in Ecuador are overcrowded, with some holding roughly twice as many detainees as their official capacity, and they have insufficient and poorly trained guards. Overcrowding appears to be rooted in the excessive use of pre-trial detention, delays in granting prison benefits established under Ecuadorian law, such as semi-open regimes or early release, and harsh drug policies that in recent years have increased sentences for drug-related offenses, including low-level offenses.

An official from the Human Rights Ombudsperson’s Office told Human Rights Watch that the victims of the November massacre included 13 people who were in pre-trial detention, six detainees who had appeals pending, and two people whose release had been ordered and were waiting to receive their written release warrants.

Human Rights Watch examined judicial documents concerning the detainees who were reported killed by the Ombudsperson's Office and other authorities. At least 15 victims reported killed by authorities were eligible under Ecuadorian law to be transferred to a “semi-open” regime or to be conditionally released, the documents showed, though it is unclear how many of them had requested transfer or release. At least three others had been convicted of a low level drug offense.

Under international human rights law, Ecuador has an obligation to ensure that everyone deprived of liberty is treated with humanity and with respect for their inherent dignity. This heightened duty of care includes ensuring their security, as well as providing adequate sleeping accommodation, food, and health care, among other requirements. Ecuador has an obligation under international human rights law to promptly and thoroughly investigate any deaths in prisons.

For additional details of Human Rights Watch findings, please see below.

The Timeline

On November 12 and 13, over 60 people were killed in a massacre in prison No. 1 in Guayas (Centro de Privación de Libertad CPL Guayas No. 1), commonly known as “Littoral Penitentiary” (Penitenciaría del Litoral). At that time, the prison housed over 7,000 detainees, although its maximum capacity was 5,246.

Human Rights Watch reviewed dozens of videos and photographs and interviewed relatives of detainees who survived or died during the event to determine what happened and create a timeline of events.

Researchers built a 3D model of the prison and overlaid geolocated stills from videos and photographs taken in the prison’s shared spaces to reconstruct key events in the days prior, during, and after the massacre. Videos and photographs were geolocated by matching landmarks such as electricity pylons and characteristic architectural features with available satellite imagery. This spatial and temporal analysis, in addition to multiple interviews with victims' relatives, allowed Human Rights Watch to identify serious shortcomings in the authorities’ response to prevent or stop the massacre and investigate those responsible for the killings.

The authorities took insufficient steps to prevent the killings, despite serious indications days prior to the massacre that violence was likely to break out in the prison. This included shooting in the prison on November 8, as reported publicly by the prison authority on November 9.

Officials said the authorities had issued alerts days prior to the massacre that violence would break out. Several relatives of victims said that their relatives in prison informed them that violence was going to erupt soon.

On November 9, the National Police reported seizing explosives, arms, drugs, mobile phones, and money in six prison pavilions. On the morning of the massacre, the police apprehended three detainees for attempting to smuggle 27 packages of ammunition and explosives, five handguns, and two rifles into the prison.

However, detainees still were seemingly able to smuggle ammunition, explosives, and firearms – that day or days prior – that were used to commit the massacre and create holes in at least two interior walls and one exterior wall, as seen in videos and photographs Human Rights Watch analyzed. One of the photographs shows damage to the external wall of pavilion 2. Another photograph shows extensive damage to the interior of the building.

On November 10, SNAI tweeted at 6:16 p.m. about detonations in pavilions 1, 2, 8 and 9 that morning.

The authorities took insufficient and slow steps to stop the killings, with police entering the prison only eight hours after the shootout began. Prison guards in Ecuador are insufficient in number, poorly trained and generally unable to address situations of serious violence without police intervention. Prosecutors are investigating whether guards took adequate steps to stop the killings during the November massacre.

Human Rights Watch analyzed two videos filmed from outside the prison from different locations in which the sound of gunfire can be heard. Filmed after sunset and posted to Facebook on November 12 at 6:34 p.m. and 6:39 p.m. local time, the videos indicate that the shootout in the prison began around 6 p.m. on November 12. Some relatives of victims who talked with detainees the day of the massacre, and a detainee who was serving his time when the massacre occurred, said that it actually began hours earlier.

Ecuador’s Police Chief, Tannya Varela, said that police protocols to respond were activated at 7 p.m. In a video recorded from a car passing by the prison entrance, posted to Facebook at 6:39 p.m. on November 12, two armored vehicles are stationed outside the entrance, indicating security forces were present before 7:00 p.m.

A video posted to Facebook at 12:46 a.m. on November 13 shows what appear to be detainees beating and burning other prisoners in a courtyard.

Human Rights Watch also received screenshots of messages sent between a prisoner and a journalist. According to the timestamps of the messages sent to the journalist, whom Human Rights Watch interviewed, the prisoner wrote at 2:07 am: “They got into the pavilion... and the police do nothing. We need [the] help of the military. They are already inside. We need help. The police do nothing. No one has entered.”

Clips from a Facebook livestream broadcast recorded by a prisoner (the livestream itself was removed shortly afterward), were reshared across Twitter beginning at 1:22 a.m., and were then widely shared and discussed. Throughout the livestream the prisoner is calling for government intervention while describing deaths in pavilion 2 and F. Sounds of gunfire in the background can be heard in the clips.

In a video posted on November 13, Police Chief Varela stated that the police entered the prison at 2:20 a.m. This timing indicates that police did not intervene until at least eight hours after the shootout began.

Poor Prison Conditions and Oversight, Setting the Stage for Violence and Abuse

Overcrowding and Poor Access to Basic Necessities

Overcrowding is common in Ecuador’s prisons and a driving force for increased violence, the country’s National Mechanism against Torture of the Ombudsperson Office, the Constitutional Court, and the commission of experts have found.

Ecuador’s prisons have capacity for 30,169 detainees, though according to government data, over 200 spaces cannot be used due to “safety and security concerns.” As of late June, prisons were holding 32,798 people, and 24 of the 36 prison facilities in the country were over capacity. During 2021, when most of the recent massacres occurred, Ecuador’s detention facilities were housing over 8,000 detainees more than the actual hosting capacity.

The Ecuadorian government does not have accurate statistics on the number and identity of people it holds behind bars, a former government official said. The internal database used for this purpose has several inconsistencies and incorrect names, the official said, which means that officials face difficulties in determining the identity of detainees who are missing or killed.

Overcrowding means that many detainees sleep on the floor, relatives of detainees said, and have limited access to basic necessities, such as adequate food, water, and medicines.

Prisons do not have adequate health services or health personnel, the National Mechanism against Torture and the National Assembly have found. Prison authorities told the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) that there is a “significant deficit” in the number of healthcare workers, with some prisons having only one or two doctors for 5,000 detainees.

Overcrowding and limited access to protective equipment and health care makes populations more vulnerable to infectious diseases like Covid-19 and tuberculosis, the Ombudsperson’s Office and prison experts said.

On November 22, President Lasso decreed two pardons, which he said would lead to the release of some 5,000 detainees by the end of February. The first decree allowed authorities to release people jailed for driving-related violations that had not caused any deaths or injuries. A second one ordered the release of detainees with “catastrophic or terminal illnesses,” including multidrug-resistant tuberculosis and combinations of HIV and tuberculosis.

Ecuadorian authorities have not published figures on how many detainees were released as a result of the decrees. Official statistics show the total number of detainees decreased by about 3,800 between November 2021 and June 2022, though part of that reduction may be due to other factors.

Overcrowding seems to be in part rooted in Ecuador’s harsh drug policies. According to official statistics cited by the IACHR in a February 2021 report, almost 30 percent of detainees in Ecuador are being held for “drug-related crimes,” apparently in part due to a substantial increase in sentences imposed for drug-related offenses, including low-level ones, under new laws.

Additionally, the excessive use of pre-trial detention is a critical problem. In December 2021, the National Court, one of the highest in the country, found that due to lack of clarity in the country’s criminal code, judges were sending detainees to pre-trial detention in an “arbitrary and widespread manner,” causing overcrowding.

The National Court ordered prosecutors and judges to ensure that detainees are sent to pre-trial detention only as a last resort when other measures are insufficient to guarantee a person’s appearance at trial or safeguard the integrity of an ongoing investigation.

Since the ruling, the number of people in pre-trial detention has decreased from 13,286 in December 2021 to 12,701 in June 2022.

Ecuadorian law allows detainees to request a “semi-open” detention regime after they have served 60 percent of their sentence and an “open” detention regime after they have served 80 percent. Additionally, some detainees can obtain a reduction in their sentences of up to 50 percent for good behavior.

The IACHR found “legal and administrative obstacles” to the timely granting of prison benefits, including delays in hearings to rule on cases and to issue release warrants. The Ombudsperson’s Office told Human Rights Watch that in September 2021 it “alerted” the SNAI and the Council of the Judiciary about “systematic delays in attending files regarding prison benefits and changes in detention regimes.”

Weak State Control or Oversight

Under international human rights law, Ecuadorian authorities have a duty of care toward people in prisons, and an obligation to protect their rights to health, life, and security. However, prisons in the country are often controlled by criminal organizations that extort detainees and their families, control shops in prisons, and threaten detainees with transferring them to cells where they would hold them in isolation, Human Rights Watch found.

Many detainees are forced to work with organized crime groups or pay them to protect themselves inside the prisons or acquire basic necessities, such as mattresses, bedding, and health supplies, relatives of victims and prison experts said.

Several relatives of detainees said that they had been asked to transfer between US$20 and $50 per week to bank accounts of strangers. Some said that their relatives in prison told them that gangs could transfer them to isolation cells if they did not pay.

Due to lack of basic necessities in prisons, including food and health supplies, many detainees have to buy them in prison stores, known as “economatos,” which are often controlled by criminal gangs, relatives of detainees and prison experts said.

Ecuador’s prison system has an insufficient number of guards. Based on information provided by government authorities, the IACHR found that, during every shift, jails in Ecuador had an average of one guard for every 62 detainees, with some larger prisons having one guard for every 99 people detained.

In total, Ecuador has 1,650 prison guards. In September 2021, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) estimated that 2,500 additional guards were needed. In April, the government initiated a selection process to hire 1,400 more prison guards.

Guards are also poorly trained. They receive brief training that is mostly theoretical and does not prepare them to handle the practical challenges of working in Ecuador’s prisons, including in responding to gang violence to prevent mass killings, a former government official told Human Rights Watch.

Due to their insufficient number and poor training, guards normally do not intervene when there are confrontations between detainees, prison experts said.

The IACHR reported “acts of corruption” in prisons that have allowed gun smuggling and a “classification” of detainees according to their money and not the crime they committed.

Ecuadorian authorities also appear to have taken limited steps to foresee and prevent outbreaks of violence in prisons, including the November massacre.

Prison conditions in the country appear to have worsened since 2013 as a result of various government actions and policies, prison experts said.

In 2014, the Ecuadorian government built large prisons, known as “mega-jails” (megacarceles) in Cotopaxi, Azuay and Guayas. The “mega-jails” have some of the worst overcrowding and lowest number of prison guards per detainee in the country. The IACHR found that these prisons generated “problems,” including challenges to control the facilities, as well as increased vulnerability for at-risk detainees. Experts from Kaleidos, an Ecuadorian NGO that has worked on prisons for years, described these “mega-jails” as “ungovernable.”

In 2018, the Ecuadorian government dissolved the Ministry of Justice and Human Rights, transferring the responsibility for overseeing prisons to the SNAI, an agency that has a smaller budget and number of officials, and limited power to promote nationwide and comprehensive policies to regulate the prison system. Many government documents, including prison maps, were lost during the dissolution of the Ministry of Justice and Human Rights, a former government official said. The documents were left in an abandoned building and unidentified people appear to have sold the paper for recycling, the former official said.