Summary

On November 4, 2013, the first day of the Islamic New Year, Saudi police and labor authorities launched a nationwide campaign to locate, detain, and deport undocumented migrant workers. The campaign followed an April 2013 amendment to the labor law that empowered police and labor authorities to enforce labor code provisions against undocumented workers, including detention and deportation for working for someone other than a designated employer.

The campaign has consisted of raids on neighborhoods and businesses, and ID checks at checkpoints. It resulted in the detention of 20,000 workers in the first two days alone, and continued in phases over the next year-and-a-half. In April 2014, Saudi interior ministry officials confirmed they had deported 427,000 undocumented foreigners in the course of the previous six months. On December 14, 2014, the Saudi newspaper Arab News reported that Saudi Arabia had detained 108,345 migrant workers across the country and deported 90,450 of them over the previous 40 days. Saudi authorities announced a new round of detentions and deportations of undocumented foreigners during the first quarter of 2015, and said on March 23 that Saudi Arabia had deported 300,000 people over the previous five months, an average of nearly 2,000 per day.

Human Rights Watch interviewed 60 migrant workers for this report, many of whom described serious abuses during the process of detention and deportation, including attacks by security forces and private citizens, inadequate detention conditions, and abuse in detention prior to deportation.

The detention and deportation campaign precipitated a wave of unrest in urban areas populated by undocumented workers, triggering violent attacks on migrants by Saudi police and citizens, especially during November 2013. The most violent attacks occurred on the evening of November 9 in areas around the Manfouha neighborhood of southern Riyadh, where Ethiopian residents make up a majority of residents. Manfouha residents told Human Rights Watch that at least three Ethiopian workers were killed during these attacks.

Ethiopian migrant workers told Human Rights Watch soon afterwards that they saw groups of people they assumed to be Saudi citizens armed with sticks, swords, machetes, and firearms, attack foreign workers. One worker said, “On the first night it was both the police and shabab [“young men” in Arabic] who were attacking and beating Ethiopians.We went out of our homes to protect them but the police were there and didn’t let us to do anything.”

Other migrants detailed serious abuses during detention, including inadequate food and sanitation and in some cases beatings by guards. One deported Yemeni worker described conditions that he endured after turning himself in to police in Jeddah in November 2013. “When they started deporting people I was working as a day laborer in Jeddah,” he said. “I was afraid because of the deportation campaign and turned myself in to go back. They kept me in Buraiman Prison for 15 days. Sometimes they brought food but it was very little and people fought over it. There was no medical care. Sometimes they slapped us with belts.”

Another Yemeni worker whom authorities deported in November 2013 after police caught him working illegally in the southern Saudi town of Jizan told Human Rights Watch that he spent one night in a deportation center before Saudi officials sent him back to Yemen by bus through the al-Tuwal border crossing. He said: “The jail conditions were bad; there are no clean bathrooms and no separation barrier so we could see others using the toilet. They took the batteries from our phones and our SIM cards, but some people refused to give them over and the guards beat them with cables.”

Following deportation, many migrants returned to their home countries destitute and with no means to buy food or pay for transportation to their home areas due at times to Saudi Arabia’s arbitrary confiscation of their personal property, which authorities refused to allow them to take. Some Somali deportees interviewed by Human Rights Watch indicated that they faced threats from both the militant rebel group al-Shabaab or Somali government forces. At least two Somalis stated that following their deportations they were harassed by Somali government officials who suspected that they had links with al-Shabaab based on their place of origin.

None of the workers interviewed by Human Rights Watch said they were permitted an opportunity to legally challenge their deportations, and Saudi Arabia has not established an asylum system whereby migrants could apply to prevent their forced return to places where their lives or freedom would be threatened.

Saudi Arabia should immediately halt mass expulsions, ensuring that removals are based on an individual assessment of the circumstances of the person being removed, including any international protection needs. It should also make further reforms to its labor sector that would serve to prevent thousands of foreign workers who enter the country from becoming undocumented. Most importantly, Saudi Arabia should grant workers the ability to change jobs and abolish the exit visa requirement, which obliges workers to obtain employer permission to leave the country, a requirement that has been shown in practice to expose them to exploitation and abuse by employers.

The Saudi government should sign and ratify the 1951 Refugee Convention, enact refugee law consistent with international standards, and establish fair asylum procedures for foreign nationals who may be at risk of persecution in their home countries. In the meantime, it should allow the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) to exercise its mandate to determine the refugee status of asylum seekers and facilitate durable solutions for those recognized as refugees, including, where appropriate, integration in Saudi Arabia.

The Saudi government has legitimate authority to deport undocumented migrants but should treat them with dignity at all times and give those who might fear persecution upon return the opportunity to lodge asylum claims and consider any other protection needs..

Saudi interior ministry officials should take immediate steps to improve conditions in the kingdom’s jails and detention centers for migrant workers facing deportation, and conduct prompt investigations into allegations of mistreatment of migrants in detention during the 2013-14 labor crackdown.

Methodology

This report is based on interviews Human Rights Watch researchers conducted between November 2013 and February 2014 with 60 migrants then resident in or recently expelled from Saudi Arabia. Of the total of 60 migrants interviewed, 46 were Yemeni citizens; Human Rights Watch interviewed six of them in Sanaa, and the 40 others at the al-Tuwal border with Saudi Arabia in northern Yemen. In February 2014, a team of Human Rights Watch researchers interviewed nine Somalis recently deported from Saudi Arabia to Mogadishu.

A Human Rights Watch researcher spoke by phone with five Ethiopian workers in Saudi Arabia in November 2013, four living in Riyadh and one in Jeddah, about the attacks on migrant workers in Manfouha on November 9, 2013. Human Rights Watch published a press release on those attacks on December 1, 2013. Material from that press release is reproduced in this report.

Human Rights Watch researchers also interviewed more than 20 government officials and representatives of local and international aid organizations offering services to deportees in Yemen and Somalia between November and February 2014.

In all cases, Human Rights Watch researchers explained the purpose of the interviews, gave assurances of anonymity where requested. None of the interviewees received monetary or other incentives for speaking with Human Rights Watch. We also received interviewees’ consent to describe their experiences and informed them that they could terminate the interview at any point. All interviews were in Arabic, Amharic, or Somali. Individual names have been changed and other identifying details removed to protect their identity and security.

I. Background: Undocumented Migrant Workers in Saudi Arabia

The campaign of detentions and expulsions of migrant workers in Saudi Arabia that began on November 4, 2013, followed the announcement in April 2013 of amendments by the Saudi cabinet to the 2007 labor law.[1] The amendment empowered police and labor authorities to enforce labor code provisions against undocumented workers, including detention and deportation for those found to be working for a non-sponsor. The authorities started enforcing the law in April 2013 but then temporarily halted enforcement after then King Abdullah declared a “grace period” to allow migrant workers to correct their status.[2]

In spite of the hundreds of thousands of deportations that have taken place since November 2013, Saudi Arabia maintains one of the largest migrant labor populations in the world. According to the Saudi labor ministry, over nine million migrant workers, more than half the work force, fill manual, clerical, service, and skilled jobs.

Saudi Arabia's restrictive kafala (sponsorship) system, which ties migrant workers' employment visas to their employers, facilitates exploitation and abuse by employers. Under this system, an employer assumes responsibility for a hired migrant worker and must grant explicit permission before the worker can enter Saudi Arabia, transfer employment, or leave the country. The kafala system gives the employer immense control over the worker. Human Rights Watch documented numerous cases where workers were unable to escape from abusive conditions or even to return home upon completion of their contracts because their employer denied them permission to leave the country.[3] Under Saudi labor law most foreign workers who change jobs without their employer’s approval become undocumented. The law also imposes an exit visa requirement that prevents all foreign workers from leaving Saudi Arabia without their employer’s permission, thereby rendering them vulnerable to exploitation and abuse by employers.[4]

Since 2011, Saudi officials, concerned that the unemployment rate of 12 percent among Saudi nationals is likely to grow as the population rises, have issued a set of reforms to the labor laws that create a tiered quota system for private sector employment of Saudi citizens.[5] The quotas vary from one labor sector to another. As part of these changes, when a firm fails to employ the required percentage of Saudi nationals, Saudi labor authorities can penalize that firm by allowing foreigners who work for it to move to other companies without first obtaining their employer’s approval. This new policy will grant some workers greater opportunity to choose their new employer.[6]

In addition to these labor reforms, since mid-2013 Saudi Arabia has signed bilateral labor cooperation or labor recruitment agreements with four countries: the Philippines, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and India. These are the first agreements of their kind. Some of the agreements include stipulations aimed at improving conditions for domestic workers, including guaranteed regular monthly wage payments, sick leave, days off and a paid annual holiday. In addition, they stipulate that employers are not to retain the passports and documents of migrant workers they employ and should not prevent them from communicating with people outside their place of work.[7]

In 2013, the Saudi authorities issued a new regulation on domestic workers, nearly all of whom are migrants, that guarantees domestic workers nine hours of rest within each 24 hours, one day off each week, and a one-month paid vacation after two years. But it also allows for domestic workers to work up to 15 hours a day, to be fired or penalized if they do not respect Islam or the kingdom’s rules and regulations, and denies workers the ability to turn down any work without a “legitimate” reason.[8] Saudi Arabia’s 2013 domestic violence law, which officially outlaws domestic violence and neglect for the first time, specifically criminalizes the infliction of such abuses against migrant domestic workers.[9]

These improvements, however, have been accompanied since 2013 by a sweeping official campaign to detain and expel undocumented workers and migrants, including migrants without valid residency or work permits, and workers caught working for an employer other than their legal sponsor. Saudi officials argue that the expulsion of undocumented migrant workers will open jobs for Saudi private sector employment and decrease unemployment.[10]

In April 2014, Gulf News quoted Saudi interior ministry officials saying they had deported 427,000 undocumented foreigners in the course of the previous six months.[11] On December 14, 2014, the Saudi newspaper Arab News reported that Saudi Arabia had detained 108,345 migrant workers across the country and deported 90,450 of them over the previous 40 days.[12] Saudi authorities announced a new round of detentions and deportations during the first quarter of 2015, and according to a media report said on March 23 that Saudi Arabia had deported 300,000 people over the previous five months, nearly 2000 per day.[13]

Migrant workers from Ethiopia and Yemen, many of whom cross into Saudi Arabia from Yemen without the required permits to seek unofficial work in the kingdom, comprised the majority of those detained and deported. The International Organization for Migration (IOM), which does not facilitate involuntary returns of Yemenis from Saudi Arabia but offers humanitarian assistance to deported Yemenis along the al-Tuwal border crossing, said that between June 2013 and November 2014, it had counted 613,743 Yemeni workers deported from Saudi Arabia.[14] The IOM also said that between December 2013 and August 2014, Saudi authorities forcibly deported 40,779 Somalis to Mogadishu.[15]

The IOM directly assisted at least 163,018 Ethiopian deportees, including 53,732 women and 8,598 children, who were returned from Saudi Arabia to Addis Ababa between November 2013 and March 2014 and provided emergency assistance to them upon arrival.[16] While many of these undocumented Ethiopians were classified as “voluntary” returns, Ethiopians interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that most turned themselves into Saudi police fearing violent attacks by Saudi citizens and security forces following clashes in Riyadh’s Manfouha neighborhood in November 2013.

Most of the deported migrant workers Human Rights Watch interviewed for this report in northern Yemen and in Mogadishu entered Saudi Arabia by crossing the border illegally from Yemen.[17] However Human Rights Watch has also documented cases of migrant workers who became undocumented when they fled an abusive employment situation and sought alternative work in the informal sector.[18]

Corruption within the kafala system increases the vulnerability of some workers, according to workers interviewed by Human Rights Watch. Thousands of foreign workers in Saudi Arabia work under the so-called “free visa” arrangement, in which Saudis posing as sponsoring employers illegally import workers to staff businesses that do not exist and charge them regular fees to maintain their residency and work permits while the workers find employment with other employers unofficially.[19]

For example, Ra’id, a 24-year old Yemeni worker, who Human Rights Watch interviewed at Yemen’s border with Saudi Arabia in November 2013, said he had entered Saudi Arabia legally after obtaining a visa to work for a cargo company, but that he had been unable to locate his sponsor after arriving and so took up informal work at a gas station. When he finally located his sponsor, the sponsor told him that the cargo company had never existed and demanded that Ra’id pay him 4,000 Saudi riyals (US$1,066) for a residency card and work permit. Ra’id said he paid the money, but the Saudi sponsor failed to provide him with either a residency card or work permit, and threatened to report him to authorities if he called back. Ra‘id eventually decided to leave Saudi Arabia, but said he then had to pay the sponsor another 4,000 riyals to obtain an exit visa. “I waited ten months with no residency,” he said. “I feel so depressed. This is no life.”[20]

Over the past ten years, Human Rights Watch has documented rampant employer confiscation of workers’ passports, withholding of wages and, and in some cases forced labor, including numerous cases in which workers were unable to escape from abusive conditions or even to return home after their contracts ended because their employer denied them permission to leave the country.[21]

Some migrants workers in Saudi Arabia told Human Rights Watch they left their original formal employment to secure better terms with another employer or to extricate themselves from abusive employment conditions. Others said they were simply stuck in Saudi Arabia, unable to leave due to strict exit visa requirements, and therefore obliged to work informally to sustain themselves and their families back home.

Unlike most workers in Saudi Arabia, these “free visa” workers are able to choose their de facto employer, but because they are not working directly for their sponsoring employer the authorities consider these workers to be undocumented, and they are subject to detention and deportation. Due to their undocumented status they cannot seek remedy or redress for any abuses they suffer. According to a Yemeni civil society group that helps Yemeni migrant workers in Saudi Arabia, many workers who enter Saudi Arabia under the “free visa” arrangement do not know that, in doing so, they are breaking Saudi labor regulations.[22]

A Yemeni migrant’s rights activist in Sanaa told Human Rights Watch that a “free visa” and attendant residency permit usually costs a worker around 15,000 Saudi Riyals ($4,000) per year.[23] Migrants caught working under the “free visa” arrangement are also subject to detention and deportation. In December 2013, Labor Minister ‘Adil Faqih announced that those who hire foreign workers but do not provide a job will face prosecution and be classified as “human traffickers.”[24] However, Human Rights Watch is not aware of any prosecutions for visa fraud that the authorities have brought against Saudis posing as employers.

Amin, 34, a migrant worker from the Yemeni town of Amran in Amran governorate, told Human Rights Watch that he obtained a “free visa” in 2011 and then went to Saudi Arabia to work in construction. He said he paid 2,400 Saudi Riyals ($640) to obtain the visa, but when he arrived in Saudi Arabia his “sponsor” demanded an additional 10,000 Riyals ($2,667) to obtain his residency card and work permit.[25] He refused to pay, he said, whereupon his “sponsor” took him to the government’s immigration center for detention and deportation. He said, “I feel like everything is fake; he told me to do whatever I wanted then changed his mind and wanted more and more...” Amin appeared not to know that the “free visa” arrangement was illegal.[26]

Workers who enter without the required permissions or become undocumented in Saudi Arabia are at significant risk of exploitation because they cannot seek redress for labor violations or abuse. Mahmoud, a Yemeni aged 27 who entered Saudi Arabia illegally in 2011, told Human Rights Watch that his employer afforded him no medical or other assistance when he lost his right arm in an accident while operating heavy machinery at a rock quarry in the town of al-Kharaj in December 2012.[27]

My arm was cut off while I was working at the controls of a heavy machine … An Indian worker drove me to the hospital. I heard the Saudi boss tell the Indian over the phone to tell the police I was in a car accident, which he did. I told the police the truth, but they did not believe me. I had two operations to stop the bleeding, and after that I was chained to the hospital bed for two-and-a-half months … My employer didn’t visit me while I was in the hospital.[28]

Saudi authorities subsequently deported Mahmoud.

Yemeni workers and officials told Human Rights Watch that the expulsions beginning in 2013 were similar in scope to Saudi Arabia’s mass expulsion of 750,000 Yemenis in 1990-91 in response to Yemen’s perceived support for Iraq during the Iraqi occupation of Kuwait.[29]

II. Harassment and Violence against Migrants

Following the crackdown on undocumented migrants in Saudi Arabia in November 2013, incidents of confrontation between migrant workers and Saudi citizens and security forces occurred across the country, primarily in neighborhoods populated by Ethiopians and Yemenis. Migrant workers allege that the security forces directly participated in some of the abuses and failed to protect other workers attacked by men who appeared to be Saudi citizens. To Human Rights Watch’s knowledge, more than a year after the most violent incidents in November 2013, there have been no investigations into allegations of police abuses against migrant workers during the expulsion campaign.

The most violent events occurred on the evening of November 9 – five days after the resumption of the detention campaign – in areas around the Manfouha neighborhood of southern Riyadh, where Ethiopian residents make up a majority of residents, according to local activists. Two Ethiopian migrant workers told Human Rights Watch that they saw groups of people they assumed to be Saudi citizens armed with sticks, swords, machetes, and firearms, attack foreign workers.[30]

One Ethiopian man, a 30-year-old supervisor at a private company, said: “On the first night it was both the police and shabab [“young men” in Arabic] who were attacking and beating Ethiopians, when we went out of our homes to protect them but the police were there and didn’t let us do anything.”[31]

The same man said that after he heard shouts and screams from the street, he left his home near Manfouha to see what was happening. When he arrived near Bank Rajahi, on the road to the Yamama neighborhood, west of Manfouha, he saw a large group of Ethiopians crying and shouting around the dead bodies of three Ethiopians. He said one had been shot, and the two others appeared to have been beaten to death. He said six other Ethiopians appeared to be badly injured.[32]

He said he saw Saudis whom he called shabab (“young men” in Arabic), and uniformed security forces attack the Ethiopians who had gathered. The shabab were using swords and machetes, while some of the uniformed officers were beating the migrants with metal police truncheons. Other officers were firing bullets into the air to disperse the crowd. He said that he narrowly escaped serious injury when a Saudi man swung a sword at his head. It missed, but hit his arm, requiring stitches to close the wound.[33]

A 26-year-old undocumented day laborer who lives in Manfouha told Human Rights Watch that he was sitting among a group of 23 Ethiopians in a private home on Street 20 on the evening of November 9 when a group of 20 shabab with machetes and pistols broke down the door and attacked the people inside. He and five other Ethiopians escaped by climbing to the roof, but he does not know what happened to the other 17 men.[34]

Another Ethiopian worker who lived nearby but did not witness the violence told Human Rights Watch that on the afternoon of November 9 he was sitting inside the Ethiopian community center and school compound five kilometers from Manfouha when 35 Ethiopian men came to the center and reported what was happening in Manfouha.[35] They said groups of armed Saudi men were forcing their way into the homes of migrant workers, removing the men, and holding the women inside.[36]

Saudi police announced later on November 9 that they had apprehended 561 people for “inciting acts of rioting” and “throwing stones at citizens and residents.” The statement by police carried by the Saudi press agency said that only two men had died – one Saudi and a man of unknown nationality – and another 68 were injured.[37] An Ethiopian Foreign Ministry spokesperson told reporters on November 12, however, that three Ethiopian citizens had been killed in the violence.[38]

The events provoked days of unrest, including further violent clashes between Manfouha residents and police on November 13 that resulted in the death of a Sudanese man, according to a media report quoting the Saudi police.[39]

The attacks in Manfouha appear to have been the worst incidents of violence against migrant workers in this period. However, workers from other countries also reported harassment by Saudi officials in other parts of the country. Nidal, a 25 year-old Yemeni man, told Human Rights Watch in Sanaa that he entered Saudi Arabia legally in 2010 to work at a media company in the southern city of Jizan.[40] In July 2013, however, he became aware of increased scrutiny of Yemeni workers by Saudi police and citizens. He said that during this period a police officer abducted him for five hours and robbed him in late July:

On Ramadan 27 I was kidnapped by a Saudi police officer wearing his tan uniform between 3:30-8:30 p.m. He abducted me near my home and stole 5,300 Saudi Riyals and my mobile phone, and then took me in an unmarked car outside the city. He threatened me with a handgun, saying that he would kill me if I talked. At 8 p.m. he took me to the [Yemeni] border and said to me: “You can either leave this life or leave Saudi Arabia.” At the border I called my sponsor to come get me, I still had my SIM card from the stolen phone. I had a good sponsor, he took me to the police to complain about what happened, they arrested the officer and took him, but then investigators pressured me to drop the case. I heard that the officer got out of jail with a medical report saying he had mental health problems. I asked police for protection from this officer, but he kept calling my company asking for me after Ramadan, he was trying to find me and harass me.[41]

Nidal said that he attempted to remain in Saudi Arabia after this incident but that he was unable to obtain new documents from Saudi labor and passports offices to replace those stolen from him. In early November, at the start of the campaign against undocumented workers, he said that he stayed home to avoid detention: “I did not go to work at the beginning of the crackdown. At first I tried to get my sponsor to fix my situation, but then I asked my sponsor for an exit visa so I could go home, I stayed in my room for two weeks straight.”[42]

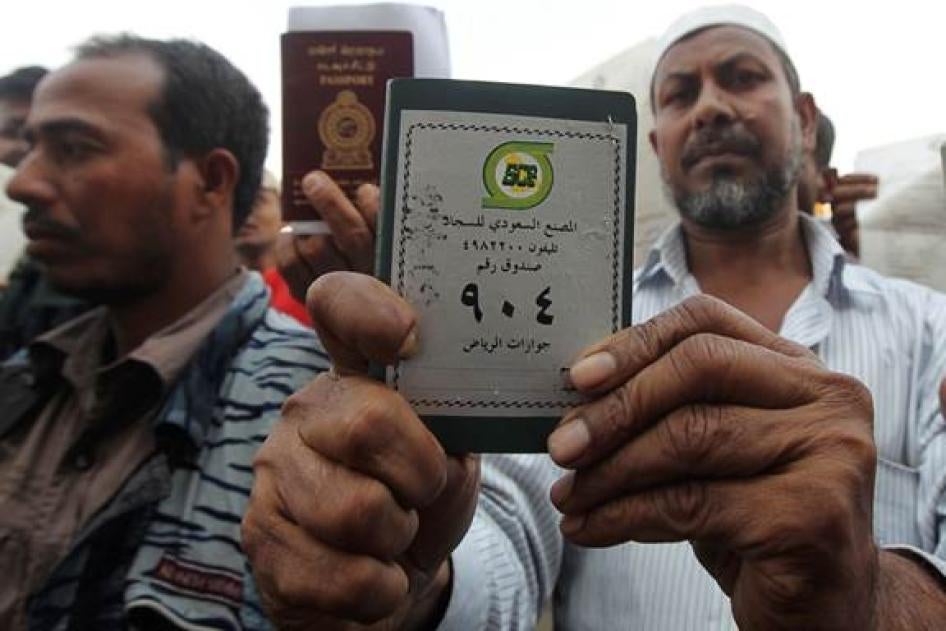

Foreign worker displays his passport as he waits outside a Saudi labor office, after missing a deadline to correct his visa status, in Riyadh, on November 4, 2013. © 2013 REUTERS/Faisal Al Nasse

III. Detention Conditions during Deportation

Of the 60 workers Human Rights Watch interviewed between November 2013 and February 2014, most complained of inadequate detention conditions during the deportation process. Complaints ranged from lack of food or receiving food of bad quality to overcrowding, lack of access to health care and physical abuse. None of the workers whom Human Rights Watch interviewed said that they were brought before a judge to challenge their detentions or deportations as required by article 14.6 of the Arab Charter on Human Rights.

Ad Hoc Detention Facilities for Detained Migrants

Saudi Arabia maintains a network of deportation centers and holding facilities for migrant workers across the country. It appears, however, that authorities did not anticipate the number of undocumented migrants who decided to turn themselves in voluntarily when the official campaign of detaining and deporting undocumented migrants resumed in November 2013, and this caused them to confine many undocumented migrants in ad hoc detention facilities. An Ethiopian official in Sanaa told Human Rights Watch on November 26: “I’m not sure Saudi Arabia was fully prepared for this. Ethiopians were in Saudi Arabia to make money, not fight.”[43]

Four Ethiopian migrant workers in Riyadh told Human Rights Watch that many undocumented Ethiopian workers in Riyadh’s Manfouha neighborhood turned themselves in to the authorities following incidents of violence by police and groups of Saudi citizens. One worker at that time described the atmosphere in Manfouha as a “battleground.”[44] The Ethiopian ambassador to Saudi Arabia, Muhammed Hassan Kabiera, told Arab News on November 13, nine days after the start of the detention campaign, that at least 23,000 Ethiopians, many from the Manfouha area, had surrendered to Saudi authorities for repatriation.[45]

The Ethiopian workers said that authorities transported the Ethiopians to makeshift holding facilities across the area, including a large wedding hall and the campus of Princess Nora Bint Abdul Rahman University, a large women’s university in northern Riyadh. One man told Human Rights Watch that he visited the wedding hall holding facility in the days following November 9 and saw thousands of foreign workers detained there, men in one area, and women and children in another, both inside and outside the building.[46]

He said that other Ethiopians in the neighborhood were trying to help the detainees by bringing food and that many at the wedding hall had been left without shelter during a heavy rainfall in Riyadh. One Ethiopian in Riyadh said he escaped from the wedding hall after officials held him in an area outside the building for 10 days. He said the authorities failed to supply the detainees with sufficient food, forcing them to buy food from Saudi guards.[47]

In February 2014, Philippines Consulate officials in Jeddah began working with Saudi authorities to deal with approximately 1,000 Filipino citizens who had set up a camp in November 2014 outside of Jeddah’s Rehab district and were demanding repatriation.[48] The workers remained in the camp until February, when the Philippines consulate began transporting them to the al-Shumaisi detention center outside Jeddah for Saudi authorities to process them for deportation.

Overcrowding and Inadequate Conditions

Most of the non-Yemeni migrant workers Human Rights Watch interviewed remained in deportation centers for weeks or months awaiting the exit visas required for repatriation. On March 3, the Saudi Gazette newspaper reported that one migrant died and nine others were injured in a stampede at the al-Shumaisi detention center. According to the Mecca Governorate police spokesperson, “Workers from different nationalities caused commotion in protest against delay in the processing of their deportation procedures.”[49]

One Yemeni worker, Hassan, described conditions that he endured after turning himself in to police in Jeddah in November 2013. “They kept me in Buraiman Prison for 15 days. Sometimes they brought food but it was very little and people fought over it. There was no medical care. Sometimes they slapped us with belts.”[50]

Saleh, another Yemeni worker whom authorities deported in November 2013 after police caught him working illegally in the southern Saudi town of Jizan told Human Rights Watch that he spent one night in a deportation center before Saudi officials sent him back to Yemen by bus through the al-Tuwal border crossing. He said: “The jail conditions were bad; there are no clean bathrooms and no separation barrier so we could see others using the toilet....”[51]

Several of the Somali deportees who spoke to Human Rights Watch researchers in February 2014 in Mogadishu said they developed chronic health problems, such as persistent coughing, while detained in Saudi Arabia prior to their deportation.

One deported Somali, Mohammed, said Saudi authorities detained him in five detention facilities for a total of 57 days before deporting him.[52] “In the first detention center in Riyadh [the Saudi capital], there was so little food, we fought over it so the strongest ate the most,” he said. “Guards told us to face the wall and then beat our backs with a metal rod…. Then we were transferred to a jail called Shimeisi in Riyadh, there were two toilets for 1,200 people, including dozens of children.”[53]

Another Somali, Nur, a 24-year old man from Mogadishu, described the conditions he had experienced during his detention at a deportation center in Jeddah:

There was no air conditioning, it was very hot. There were 5 toilets for all of us [just under 790 people]. We slept on the floor. You were lucky if you have a cardboard box to sleep on. There was hardly any space to sleep. We had three meals a day, but it was insufficient [one piece of bread and soup for breakfast, half a plate of rice for lunch, and bread and soup for dinner]. If you had money on you, you could ask the police through the window to help you to buy food. But most people didn’t have money on them as they were picked up in the street. I had $25 but used up $18 in the first seven days.[54]

A health worker in Mogadishu told Human Rights Watch that she attended a one-year-old boy in a Mogadishu hospital for several weeks. The baby had been detained with his father for a month before being deported and was suffering from diarrhea, malnutrition, and anemia.[55]

Saladu, 35, a Somali woman, said that Saudi authorities had detained her for nine days with her two children, aged seven and nine, and her sister’s three children before deporting them: “The room we stayed in with 150 other women and children was extremely hot and there was no air conditioning. The children were sick. My son was vomiting and his stomach was very bloated. There were no mattresses, people just slept on the floor.”[56]

The IOM in Mogadishu reported publicly that many of the deportees were in poor health because of their prolonged detention in substandard conditions before they were deported. Some had suffered physical and psychological trauma or had respiratory illnesses, including pneumonia.[57]

The process for deporting undocumented Yemeni workers appears to differ from the process for other nationalities.[58] Almost all of the undocumented Yemeni workers whom Human Rights Watch interviewed in November 2013 had been detained by Saudi border guards while trying to cross the border into Saudi Arabia or caught by police when they were working in the southern town of Jizan or surrounding villages.[59] Due to the proximity to the Yemeni border most of these workers remained in detention for no more than one or two days before Saudi authorities expelled them in large groups by bus to the Yemeni side of the border.

Despite their short stay in either the Jizan detention center or another deportation facility near the border crossing, almost all of the Yemenis complained of overcrowding and poor treatment.

Mansour, a 42-year old Yemeni worker that Human Rights Watch interviewed at the al-Tuwal border crossing on November 26, 2013 said that he had been living in Saudi Arabia and working as an electrician without documentation for around a year, together with his brother. He said that the day before, November 25, police had raided his home in Jizan and detained both him and his brother. He said they refused to allow him to take his mobile phone or pack a suitcase, saying one of the officials told him, “You won’t even take a t-shirt.”[60]

He criticized the lack of medical care available to workers in the overcrowded deportation center, saying that his brother was ill and periodically fainted but had received no medical attention. He said Saudi officials crammed him and his brother and around 120 other Yemenis into a 45-seat bus to transport them to the Yemeni side of the border.[61]

Samih, a 33-year old Yemeni worker in Sanaa, told Human Rights Watch that the food he received at a deportation center in Jizan was insufficient, consisting of no more than a small portion of spoiled rice and lentils each day, while the only drinking water came from the same faucet above the Turkish toilet used to flush waste down the toilet’s drain.[62] Another Yemeni deportee, Hamoud, said that guards did not provide any food during his 36-hour detention.[63]

Humanitarian workers assisting returnees at the Saudi-Yemen border told Human Rights Watch that many of the deportees returned with health problems that appeared to result from the conditions of their incarceration in Saudi Arabia. According to one doctor,

The most common medical conditions we see are fatigue, motion sickness, vomiting, and headaches, all due to the overcrowding in detention. We’ve also seen urinary tract infections due to long periods of not using the restroom, as well as some injuries from physical violence, including emergency cases like fractures.[64]

The aid workers said that in mid-November 2013 Saudi Arabia returned the body of a Yemeni man who had died in Saudi detention. One aid worker said, “We received a dead body of a middle-aged Yemeni man; he had been with his brother when he died in detention. The Saudis claim he died in the bus, but his brother said he died of suffocation because of a stampede in jail due to overcrowding.”[65]

On November 28, 2013, Yahya, a 33-year old Yemeni deportee, showed a Human Rights Watch researcher a cut on his right heel that appeared to be infected, saying he had sustained the injury when stepped on glass while trying to run away from police in the southern Saudi town Abha. He said that he had received no treatment for the injury following his detention and that there were no medical services at the deportation center where he was held.[66]

The aid workers said that buses arriving from the Saudi side of the border were seriously overcrowded, with two or three Yemeni deportees to each seat.[67] Rami, a Yemeni deportee, told Human Rights Watch that Saudi police caught him in Riyadh and put him on a bus to the Yemeni border, a trip of over 600 kilometers. He said that there were over 70 people in a bus with 45 seats.[68]

Verbal and Physical Abuse in Detention

Many of the deportees Human Rights Watch interviewed said guards in Saudi jails abused them or others during their time in detention. This abuse ranged from verbal abuse to beatings of detainees with cables, belts, and fists.

Samih, a Yemeni man who worked in the Saudi town Baha prior to his deportation in April 2013, told Human Rights Watch that he witnessed guards harshly beating a man they believed to be a member of the Houthi movement, a Zaidi Shi'a resistance group from northern Yemen, considered a terrorist organization by Saudi Arabia. He said that he believed the man had a mental disability.[69]

Another deportee, Nagi, a 57-year old Yemeni from Aden, said that Saudi border guards caught him while he was walking through an agricultural area in Jizan looking for work.[70] He told Human Rights Watch what he saw when he was detained for one day at a deportation center near the al-Tuwal border:

There were 300 people in the same jail cell, one on top of another. There was a lot of cursing by guards, one of them was saying “dogs are better than you [Yemenis]” while he was beating detainees with a cable. I saw him beat 20 people. Some of them [guards] were also throwing cold water on us while we were sleeping.[71]

Ali, 26, another Yemeni deportee, told Human Rights Watch that during his 10-day detention at the deportation center near the border he saw one Saudi guard who frequently beat Yemeni detainees, including one night when he told them, “I will go and come back and if I see any of you sleeping I will hit you.”[72] Ali said that the guards asked whether any of the detainees were from Sa`ada, the Houthi stronghold in northern Yemen, and then singled them out for beatings.[73]

Another Yemeni, Musa, 33, said that he worked as a shepherd in the Jizan area for four years prior to his deportation in November 2013. He told Human Rights Watch, “It was very crowded in prison, when I asked for water they beat me with a stick. They gave me just one piece of bread to eat, and the only water was from the toilet faucet.”[74]

One deportee, Akbar, said that a Saudi guard beat him in detention with a cable: “He would order us to walk straight in a line, and he would randomly single out deportees to hit with a cable as we walked by.”[75] According to Ayyash, a 25-year old Yemeni, “If someone made trouble [the guards] would enter and beat everyone inside using cables, wires, or the butt of a gun. Asking for food is a problem, or laughing or playing.”[76]

Other Yemeni workers reported that Saudi border guards abused them after catching them in the desert attempting to cross into Saudi Arabia, but before turning them over to detention centers for deportation.

Majed, a 27-year old Yemeni man from the town Mahweet in Mahweet governorate, said that Saudi border guards caught him trying to enter with 27 other Yemenis, including four smuggling in the narcotic leaf qat.[77] He said,

They accused me of being a qat dealer, but I was going in to work in construction. They searched my pockets and when they found my cigarettes they made me eat the tobacco from them. Then they played with us by making us march back and forth on their orders, and one of them slapped me in the chin … what can I do? I’m under their hand and they can do whatever they want with me.[78]

Another Yemeni, Ibrahim, 22, said that a border guard caught him as he was entering Saudi Arabia. He said, “I was running away, but a soldier caught me after I hit a rock and fell down. He said, ‘I can shoot you and no one will ask about it.’ I told him I wasn’t afraid and he kicked me.”[79]

Afif, a 53-year old Yemeni man from the Red Sea port city Hodaida, said that Saudi border guards caught him as he was trying to enter with a group of 50 Yemenis and a smuggler. He said that after the guards caught them they made each Yemeni lie down on the ground while they kicked them in their kidneys one by one, threatening to shoot them if anyone moved.[80]

Nasser, a 16-year old Yemeni also from Hodaida, said that Saudi guards made him and three other men perform exercises at their command after guards caught them trying to cross in the desert. He said, “After they caught us they put us in a tent. They made us exercise with heavy sacks of sand, we would have to lift and hold each sack for 5-10 minutes while they laughed at us. Then they made us lie down flat and kicked us and put the sacks on our backs and jumped on them.”[81]

Five of the nine Somalis interviewed by Human Rights Watch also complained of beatings and ill-treatment in detention. In February 2014, the IOM, which offered humanitarian assistance to returnees, noted that “a significant number [of Somali deportees] may have been subjected to ill-treatment.”[82]

Nur, a Somali deportee from Mogadishu, said he saw guards regularly beat detainees while he was detained awaiting deportation:

Whenever the police would enter the room, they would beat people with an electric stick. I was not beaten, but the Nigerians who were very strong and would resist the police – they would knock on the door asking for things and when the police would come in to stop them they would fight back and would hit them with the stick. The person who was hit would fall down on the floor.[83]

Salad, a 26-year old Somali, also said that Saudi guards beat him and others at a deportation center in Jeddah:

Once we spent a day and a half without food. We started beating the doors and the police came into the cell and beat us. When they came in, we were ordered to put our heads against the wall and they beat us. They beat us on our backs with a stick. Because of the beating and the time I spent sleeping on the floor, I still have back pains. This happened on my third day in this center.[84]

A Somali woman sits following her deportation from Saudi Arabia to Mogadishu in January 2013. © 2013 Samer Muscati/Human Rights Watch

Somalis said that beatings and other abusive treatment continued during the deportation process. A woman in her ninth month of pregnancy, Sadiyo, who was detained and deported separately from her husband, told Human Rights Watch that a Saudi policewoman beat her on the back with a baton while she stood in line at Jeddah airport. She went into labor and gave birth on the cabin floor of the plane as it flew to Mogadishu.[85]

Saudi Arabia should ensure that prisoners and detainees, including migrants awaiting deportation, be held in conditions that comply fully with Article 16 of the UN Convention against Torture and the UN Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners.[86]

Special attention should be paid regarding the stage of pregnancy of women while in custody and with regard to the decision to deport them. As made clear by the committee overseeing the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, to which Saudi Arabia is a state party, when deportation cannot be avoided, “States parties need to treat each case individually, with due consideration to the gender-related circumstances.”[87] This would include, for example, pregnancy and women who are breastfeeding. Women held in custody by state authorities must be provided with access to adequate and gender-specific health care.[88]

IV. Conditions Following Deportation

Following deportation, many migrants returned to their home countries destitute and with no means to buy food or pay for transportation to their home areas due at times to Saudi Arabia’s arbitrary confiscation of their personal property which authorities refused to allow them to take.

Yemen

A Human Rights Watch researcher at the al-Tuwal border crossing witnessed hundreds of Yemeni migrant workers crossing into Yemen between November 27-30, 2013 after the Saudi authorities deported them. Most of those interviewed said they were not allowed to take their personal belongings with them. Many said they had no hope of recovering lost wages and the possessions they had been forced to leave behind in Saudi Arabia.[89]

Although some deported Yemeni migrants have received food and humanitarian support, when Human Rights Watch visited the border no aid agencies or Yemeni government facilities were present to assist the migrant workers to obtain transport to their home areas from the remote border crossing. A Human Rights Watch researcher saw dozens of deportees attempting to hitchhike south from the border.

An official from Yemen’s expatriates affairs ministry told Human Rights Watch in November that mass expulsions of Yemeni workers would cost the country over $1 billion in lost worker remittances over the next few years.[90]

Ethiopia

In Ethiopia, according to the migrants documentation organization, the Regional Mixed Migration Secretariat (RMMS), the IOM, in cooperation with other agencies, set up five transit centers in Addis Ababa to temporarily house the influx of over 150,000 Ethiopians, many of whom had no means of returning home without assistance.[91] These transit centers were scaled down to two by January 2014 as the number of returnees fell.[92]

According to the International Rescue Committee (IRC), “Many of [the Ethiopians] returning were forced to leave [Saudi Arabia] on short notice, had to abandon their property in Saudi Arabia, and now find themselves back in Ethiopia with little money, few possessions and almost no prospects for the future.”[93] Angelica Kokutona Wagwa, a psychologist with Doctors without Borders (MSF) in Ethiopia, commented on the psychological state of Ethiopians upon return, stating, “[m]ost of the returnees that we are attending are suffering from major depression, post-traumatic stress disorders (PTSD), acute stress, generalized anxiety, dissociative and psychotic syndromes.”[94]

Somalia

Between December 2013 and August 2014 Saudi authorities deported 40,779 Somalis to Mogadishu, according to the IOM.[95] The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) stated in its latest country guidance on Somalia that southern and central Somalia “remains a very dangerous place” and that it “consider[s] the options for Somalis to find protection from persecution or serious harm within Southern and Central Somalia to be limited.”[96]

A Somali woman deported on January 29, 2014 to Mogadishu after working for 10 years as a domestic worker in Saudi Arabia. © 2013 Samer Muscati/Human Rights Watch

Somali deportees interviewed by Human Rights Watch indicated that they faced threats from both the militant rebel group al-Shabaab and Somali government forces. At least two Somalis stated that following their deportations they were harassed by government officials who suspected that they had links with al-Shabaab based on their place of origin.

One Somali, Ahmed, said that he was jailed upon his return to Somalia:

When [border officials] stopped me they asked me who are you, I said I am Somali. Then they asked me where are you from; I told them that I am from Bay region specifically Dinsoor district, but I also told them that I was deported from Saudi Arabia. One of them said to me we know that you are a member of al-Shabaab, you can’t trick us, just tell us where you are going to attack and why you want to harm innocent people.… At the prison I was not even interrogated, they registered my name and my belongings and took me into a small room with ten other prisoners. The room was like if it was intended to use as a torture, because it was around one by two meters and it was very hot... Everyone in the room was sick, and there was itching, coughing, sneezing and stomach bugs… I was very surprised that I was arrested and deported from a foreign country and I was also arrested in my country without aim and no one asked me why I was there.[97]

He said that authorities released him after five days after a relative vouched for him.

Another Somali, Abdul Rasheed, said that following his deportation Somali government soldiers beat him with their fists and the butts of their guns at the Bakara market in Mogadishu because they did not recognize him and suspected him of being linked to al-Shabaab. He said that many of the Somalis deported from Saudi Arabia were from al-Shabaab held areas and had fled to Saudi Arabia for refuge. “A lot of the Somalis I was detained with were from the southern regions because there was lots of fighting in those regions and so either you joined Al-Shabaab, or a militia, or you fled,” he said.[98]

Given the gravity of the human rights crisis in in Somalia and the number of people being deported, Saudi Arabia may be violating its obligation under customary international law not to return anyone to a place where their life or freedom would be threatened for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion or where they would face torture or prohibited ill-treatment.

Under article Six of Saudi Arabia’s basic law, the government can grant “political asylum provided it is in the public interest,” but Saudi Arabia has not ratified the 1951 Refugee Convention and has not established an asylum system.[99] The UN’s refugee agency, UNHCR, maintains a small staff in Riyadh but the Saudi authorities do not permit UNHCR to receive and review refugee claims, a process known as “Refugee Status Determination.” The Saudi authorities have no other procedures in place that would allow Somalis or others who claim a fear of persecution or other harm in their home countries to seek protection in Saudi Arabia or their challenge their deportation from Saudi Arabia.

Saudi Arabia’s lack of an asylum process and mass expulsions of migrants without any individual assessment of the circumstances of those subject to removal appear to violate not only its customary international law obligations, but also provisions of the Arab Charter on Human Rights. Article 28 of the charter holds that “[e]veryone has the right to seek political asylum in another country in order to escape persecution,” and article 26 prohibits collective expulsions in all circumstances.

On January 17, 2014, UNHCR issued guidelines for factors countries should consider when assessing refugee claims by Somali nationals or other claims for protection based on international human rights law. On January 28, 2014, UNHCR issued a news release on these guidelines, appealing to all governments “to uphold their obligations” not to forcibly return anyone to Somalia unless they are convinced the person would not suffer persecution or other serious harm upon return.[100] In April 2015, commenting on Kenya’s plans to close Dadaab refugee camps, UNHCR stated that “large-scale returns are still not possible in many parts of the country, in particular to South Central Somalia.”[101]

Recommendations

To the Government of Saudi Arabia

- Reform or abolish the kafala sponsorship system so that temporary employment-based visas do not tie workers to a specific employer

- Ensure that all workers can change employers without losing legal status and without having to obtain their first employer's permission

- Abolish the “exit visa” and immediately eliminate the requirement for migrant workers to secure the consent of their sponsors in order to obtain “exit visas” to leave Saudi Arabia

- Take concrete steps towards eliminating visa corruption, including by prosecuting those who engage in visa corruption

- Inspect and improve conditions of detention centers for migrants in the process of deportation, and take measures to ensure that migrants are treated humanely in detention and during deportation, including ensuring that all detainees are brought before a judge and have an opportunity to challenge the lawfulness of detention

- Conduct a prompt and thorough independent investigation into allegations of mistreatment of foreign workers awaiting deportation during 2013-14 mass expulsions

- Ensure that detained migrants, especially pregnant women, receive adequate and appropriate health care while in custody, including pre and post-natal care for new mothers

- Refrain from expelling unaccompanied migrant children, pregnant women, and members of other vulnerable groups that are protected by international and national law

- In the absence of any procedure to assess refugee claims in Saudi Arabia, halt all deportations of Somali nationals to Mogadishu and central Somalia, where they are at risk of serious human rights abuses.

- Sensitize all security personnel likely to come into contact with migrants to the rights of migrants, specifically to the rights of refugees, asylum seekers, pregnant women, children (including unaccompanied children), and persons with disabilitiesDevelop a system for the fair and legal processing of irregular migrants.

- Continue to facilitate the timely voluntary repatriation of migrants who wish to return to their country of origin

- Sign and ratify the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol.

- Establish refugee law consistent with international standards and asylum procedures for stateless people and foreign nationals at risk of persecution in their home countries.

- Meanwhile, allow the UN refugee agency (UNHCR) to exercise its mandate by allowing it to determine asylum seekers’ refugee status and facilitate durable solutions, including integration in Saudi Arabia, for those recognized as refugees.

- Establish reception centers for asylum seekers to ensure their basic needs are met while their claims are being processed, including a best interest determination and access to a guardian for unaccompanied children.

To the Governments of Yemen, Ethiopia, Somalia, and other Sending Countries to Saudi Arabia

- Urge Saudi Arabia to enact and implement laws to protect the rights of migrants and asylum seekers, regardless of whether their entry was legal.

- Launch targeted information campaigns to ensure that prospective migrants to Saudi Arabia are informed both of the risks they may face on the journey to Saudi Arabia as well as risks they may dace living and working in Saudi Arabia and their rights with respect to the Saudi authorities.

Acknowledgements

This report was researched and written by Adam Coogle, researcher with the Middle East and North Africa division at Human Rights Watch.

Samer Muscati, researcher for the women’s rights division, Laetitia Bader, researcher for the Africa division, Felix Horne, researcher for the Africa division, and Belkis Wille, researcher for the Middle East and North Africa division, provided support.

The report was reviewed by Malcolm Smart, consultant editor with the Middle East and North Africa program; Laetitia Bader; Felix Horne; Bill Frelick, Refugee Rights Program director; Clive Baldwin, senior legal advisor; Benjamin Ward, acting senior legal advisor; and Tom Porteous, deputy program director. Sarkis Balkhian and Sandy Elkhoury assisted with proofreading, footnoting, and formatting. Layout and production were coordinated by Grace Choi, publications director, and Fitzroy Hepkins, administrative manager.

Human Rights Watch would like to express our deep appreciation to all deported workers who shared their stories with us.

Appendix I: Letter to Ministry of Interior and Ministry of Labor of the K.S.A from Human Rights Watch

Dated April 8, 2015

His Highness Mohammed bin Nayef Al Saud

Minister of Interior

Ministry of Interior

Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

His Excellency Adel Fakeih

Minister of Labor

Ministry of Labor

Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

Your Highness/Excellency,

I write to inform you that Human Rights Watch plans to publish a report on the detention and deportation by Saudi Arabian authorities of hundreds of thousands of undocumented workers since 2013, to share with you the main findings of that report, and to request information concerning aspects of Saudi Arabia’s labor regulation, detention, and asylum policies.

We request that you respond to this letter by April 30, 2015 in order that we can reflect the information you provide in our forthcoming report.

On November 4, 2013, the first day of the Islamic New Year, Saudi police and labor authorities launched a nationwide campaign to locate, detain, and deport all undocumented migrant workers following an April 2013 amendment to Saudi Arabia’s labor law that empowered police and labor authorities to enforce labor code provisions against undocumented workers, including detention and deportation for working for a non-sponsor.

Under Saudi labor law all foreign workers who leave their designated sponsor without permission to work for another employer become undocumented. The law also imposes an exit visa requirement that prevents all foreign workers from leaving Saudi Arabia without their employer’s permission, thereby rendering them vulnerable to exploitation and abuse by employers.

In conducting the campaign, police and labor authorities raided neighborhoods and businesses, and carried out ID checks on the streets, detaining some 20,000 migrant workers within just the first two days. On December 14, 2014, the Arab News reported that Saudi authorities had detained 108,345 migrant workers in the previous 40 days and had deported 90,450 of them. In April 2014, Ministry of Interior officials announced that the authorities had deported 427,000 undocumented foreigners in the previous six months.

Migrant workers from Ethiopia and Yemen, many of whom cross into Saudi Arabia from Yemen without the required permits to seek unofficial work in the kingdom, comprised the majority of those detained and deported. The International Organization for Migration (IOM), which does not facilitate involuntary returns of Yemenis from Saudi Arabia but offers humanitarian assistance to deported Yemenis along the al-Tuwal border crossing, said that between June 2013 and November 2014 it had counted 613,743 Yemeni workers deported from Saudi Arabia. The IOM also said that between December 2013 and August 2014 Saudi authorities forcibly deported 40,779 Somalis to Mogadishu.

The IOM directly assisted at least 163,018 Ethiopian deportees, including 53,732 women and 8,598 children, who were returned from Saudi Arabia to Addis Ababa between November 2013 and March 2014 and provided emergency assistance to them upon arrival. While many of these undocumented Ethiopians were classified by the IOM as “voluntary” returns, Ethiopians interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that most turned themselves into Saudi police fearing violent attacks by Saudi citizens and security forces following clashes in Riyadh’s Manfouha neighborhood in November 2013.

Human Rights Watch conducted face to face and telephone interviews between November 2013 and February 2014 with some 60 migrants who were either resident in or had recently been deported from Saudi Arabia; they included 46 Yemeni nationals and nine Somali nationals. As well, Human Rights Watch spoke by phone in November 2013 to five Ethiopian workers, four of whom were then residing in Riyadh and the other in Jeddah.

Many of the migrant workers interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that they had experienced serious abuses during their detention and deportation. These included physical assaults by members of the Saudi security forces and private citizens, inadequate detention conditions, and beatings in detention prior to deportation.

At its outset, the deportation campaign sparked a wave of protests in urban areas populated by undocumented workers, which our research indicates included violent attacks on migrants by Saudi police and some private citizens. The most serious such attacks occurred on the evening of November 9, 2013 in areas near the Manfouha neighborhood of southern Riyadh, where many Ethiopians reside.

Ethiopian migrants who were present at the time told Human Rights Watch that they saw Saudi police and groups of people they assumed to be Saudi citizens who were armed with sticks, swords, machetes, and firearms, attack foreign workers in the streets. They said that the November 9 attacks resulted in the deaths of at least three Ethiopian migrants, although they were not able to name them. Human Rights Watch was not able to independently confirm the deaths, but an Ethiopian Foreign Ministry spokesperson told reporters on November 12 that three Ethiopian citizens had been killed.

The allegations of beatings and other ill-treatment of migrants detained pending deportation in 2013-2014 should be investigated by the Ministry of Interior.

Other migrants interviewed by Human Rights Watch described being held in grossly inadequate detention conditions, without sufficient food and sanitation; some alleged beatings by guards. One Yemeni who had been working as a day laborer in Jeddah said that after he turned himself in to police in November 2013, Saudi authorities held him at Buraiman Prison for 15 days without adequate food or any medical care prior to his deportation, and that guards sometimes “slapped us with belts.” Prisoners and detainees, including migrants awaiting deportation, should be held in conditions that comply fully with Article 16 of the UN Convention against Torture and the UN Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners.

Another Yemeni worker told Human Rights Watch that Saudi officials deported him to Yemen by bus through the al-Tuwal border crossing after detaining him for one night in seriously inadequate conditions, where he saw guards beat “with cables” other migrants who refused to hand over the batteries and SIM cards from their phones.

Many deported migrants interviewed by Human Rights Watch were destitute on arrival in their own countries because Saudi authorities had confiscated their personal possessions. The Saudi government has legitimate authority to deport undocumented migrants but should first give those who might fear persecution upon return the opportunity to lodge asylum claims, consider any other protection needs and treat them with dignity at all times.

Our research indicates that Saudi authorities failed to take adequate steps to consider the protection needs of undocumented migrants prior to their deportation, including the risk of torture or other persecution in their home countries, or to allow those facing deportation any opportunity to challenge their deportation before Saudi courts or through other means. Those interviewed by Human Rights Watch following their deportation said that they had no opportunity to contest or appeal against their deportation prior to removal.

The Saudi government should promptly establish fair asylum procedures for foreign nationals who may be at risk of persecution in their home countries or, alternatively, to allow the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) to exercise its mandate to determine the refugee status of asylum seekers and facilitate durable solutions for those recognized as refugees, including, where appropriate, integration in Saudi Arabia.

According to the International Organization for Migration (IOM), Saudi authorities deported over 40,000 Somalis to Mogadishu between December 2013 and August 2014. Given the gravity of the human rights crisis in in Somalia and the number of people being deported, Saudi Arabia may be violating its obligation under customary international law not to return anyone to a place where their life or freedom would be threatened for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion or where they would face torture or prohibited ill-treatment.

In light of our findings, Human Rights Watch requests your response to the following questions:

- How many undocumented foreigners has Saudi Arabia detained and/or deported since March 2013? On what legal basis does Saudi Arabia carry out deportations?

- Does Saudi Arabia afford undocumented foreigners the right to challenge deportation orders in Saudi courts; if so, how are they informed of this right and how many undocumented foreigners have exercised this right since March 2013?

- On what basis can foreign nationals make asylum claims in Saudi Arabia, and what is the legal process for making asylum claims?

- Does Saudi Arabia accept the customary international law principle of non-refoulement, which requires that governments refrain from returning or transferring people to places where their lives or freedom would be threatened for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion or where they would face torture or prohibited ill-treatment? What policies and/or measures are in place in Saudi Arabia to evaluate whether individual deportations comply with the principle of non-refoulement?

- Did the Ministry of Labor, the Ministry of Interior or any other official body set out regulations, procedures, or guidelines to labor inspectors and police for implementing the campaign to locate, detain, and deport undocumented workers? If so, what are these regulations, procedures, or guidelines?

- Does Saudi Arabia detain undocumented foreigners under immigration powers in regular prisons or only in immigration detention centers? If they are held in regular prisons, are they commingled with criminal inmates or kept in a segregated part of the facility exclusively devoted to immigration detention?

- How many detention centers for undocumented foreigners exist in Saudi Arabia? Where are these centers located and what are their names and capacities? Which agency is in charge of these centers?

- What steps does the Interior Ministry take to ensure adequate conditions in detention centers for undocumented foreigners? Does the Interior Ministry undertake regular inspections? If so, which department is responsible for the inspections, and how often do they occur?

- Does UNHCR have free and unfettered access to detention centers holding foreigners in order to identify and assist those in need of international protection?

- Has any Saudi government agency carried out an investigation into allegations of beatings and other ill-treatment of undocumented foreigners in Saudi detention centers in 2013 and 2014? If so, what were its findings?

- Have Saudi authorities investigated alleged attacks on Ethiopian migrants by Saudi police and citizens in November 2013, and if so with what outcome? How many migrants were killed and injured in these attacks?

As stated above, we hope to receive your response to these questions and any other comments by April 30, 2015 in order to enable us to reflect them appropriately in our forthcoming report.

Thank you, in anticipation, for your assistance in this matter.

Sincerely,

Sarah Leah Whitson

Executive Director

Middle East and North Africa

Human Rights Watch

[1] “KSA Goes Tough on Illegals,” Arab News, March 19, 2013, http://www.arabnews.com/news/445349 (accessed February 9, 2015).

[2] “Joy as King Extends Grace Period to Nov. 3,” Arab News, July 2, 2013, http://www.arabnews.com/news/456804 (accessed February 9, 2015).

[3] Human Rights Watch, As If I’m Not Human: Abuses against Asian Domestic Workers in Saudi Arabia, July 2008, http://www.hrw.org/reports/2008/07/07/if-i-am-not-human-0.

[4] Human Rights Watch, As If I’m Not Human: Abuses against Asian Domestic Workers in Saudi Arabia, July 2008, http://www.hrw.org/reports/2008/07/07/if-i-am-not-human-0.

[5] For a comprehensive Arabic-language guide on Nitaqat (or Saudization) reforms see “Daleel al-Nitaqat [Nitaqat Guide]” Saudi Ministry of Labor, December 2013, http://www.emol.gov.sa/nitaqat/nitaqat.pdf (accessed February 9, 2013). For English-language explanation of the program see “New Saudization Program,” (Overseas Filipino Workers) OFW Empowerment, http://ofwempowerment.com/ofw-guide/new-saudization-program/ (accessed February 9, 2015).

[6] “Ministry Eases Sponsorship Transfer Rules,” Arab News, September 10, 2014, http://www.arabnews.com/featured/news/628081 (accessed February 9, 2015).

[7] “Kingdom, Philippines Sign Labor Agreement,” Saudi Gazette, May 20, 2013, http://www.saudigazette.com.sa/index.cfm?method=home.regcon&contentid=20130520166522 (accessed February 9, 2015); “KSA to Sign Labor Recruitment Agreement with 6 Countries,” Arab News, January 1, 2014, http://www.arabnews.com/news/501731 (accessed February 9, 2015); “Kingdom and Sri Lanka Sign Recruitment Deal,” The Peninsula Times, http://www.peninsulatimes.org/2014/01/12/kingdom-sri-lanka-sign-recruitment/ (accessed February 9, 2015); Nisha Varia, “Dispatches: New Protection for Saudi Arabia’s Domestic Workers,” Human Rights Watch, February 19, 2014, http://www.hrw.org/news/2014/02/19/dispatches-new-protection-saudi-arabia-s-domestic-workers.

[8] P.K. Abdul Ghafour, “New Law to Protect Domestic Workers,” Arab News, July 17, 2013, http://www.arabnews.com/news/458281 (accessed February 9, 2015); “Proposed Domestic Workers Contract Falls Short,” Human Rights Watch news release, November 17, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/11/16/proposed-domestic-workers-contract-falls-short.

[9] “Saudi Arabia: New Law to Criminalize Domestic Abuse,” Human Rights Watch news release, September 3, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/09/03/saudi-arabia-new-law-criminalize-domestic-abuse.

[10] “KSA Goes Tough On Illegals,” Arab News, March 19, 2013, http://www.arabnews.com/news/445349 (accessed February 9, 2015).

[11] Habib Toumi, “Saudi Arabia Deports 427,000 Foreigners in Six Months,” Gulf News, April 27, 2014, http://gulfnews.com/news/gulf/saudi-arabia/saudi-arabia-deports-427-000-foreigners-in-six-months-1.1324727 (accessed February 9, 2015).

[12] Irfan Mohammed, “Over 90,000 Expats Deported in 40 Days,” Arab News, December 14, 2014, http://www.arabnews.com/saudi-arabia/news/674166?quicktabs_stat2=0 (accessed February 9, 2015).

[13] “Nearly 300,000 illegals deported in 5 months,” Arab News, March 23, 2015, http://www.arabnews.com/news/722066 (accessed April 1, 2015).

[14] International Organization on Migration (IOM), “Ethiopian Diaspora Continues its Support to IOM for Migrants Returning Home from Saudi Arabia,” July 3, 2014, http://iomethiopia.org/index.php/news/168-ethiopian-diaspora-continues-its-support-to-iom-for-migrants-returning-home-from-saudi-arabia (accessed February 9, 2015).

[15] International Organization on Migration (IOM), “Situation Report 10: IOM Somalia Returns,” August 2014, http://www.iom.int/files/live/sites/iom/files/Country/docs/IOM-Somalia-Returns-Situation-Report-No-11.pdf (accessed February 9, 2015).

[16] International Organization on Migration (IOM), “Ethiopian Diaspora Continues its Support to IOM for Migrants Returning Home from Saudi Arabia,” July 3, 2014, http://iomethiopia.org/index.php/news/168-ethiopian-diaspora-continues-its-support-to-iom-for-migrants-returning-home-from-saudi-arabia (accessed February 9, 2015).

[17] Human Rights Watch has documented the harms suffered by migrants, most from the Horn of Africa, who try to travel through Yemen on their way to Saudi Arabia for work, see Human Rights Watch, Yemen’s Torture Camps: Abuse of Migrants by Human Traffickers in a Climate of Impunity, May 2014, http://www.hrw.org/reports/2014/05/25/yemen-s-torture-camps.

[18] Human Rights Watch, As If I’m Not Human: Abuses against Asian Domestic Workers in Saudi Arabia, July 2008, http://www.hrw.org/reports/2008/07/07/if-i-am-not-human-0.

[19]“Cost of the ‘free visa’”, Saudi Gazette, May 8, 2013, http://www.saudigazette.com.sa/index.cfm?method=home.regcon&contentid=20130508164732 (accessed August 20, 2014).

[20]Human Rights Watch interview with Ra’id, Haradh, Yemen, November 28, 2013.

21 Human Rights Watch, As If I’m Not Human: Abuses against Asian Domestic Workers in Saudi Arabia, July 2008, http://www.hrw.org/reports/2008/07/07/if-i-am-not-human-0.

[22] Human Rights Watch interview with Najeeb al-Odaini, Yemeni Migrants Organization, Sanaa, November 24, 2013.

[23] Human Rights Watch interview with Najeeb al-Odaini, Yemeni Migrants Organization, Sanaa, November 24, 2013.

[24] Abdurahman Al-Misbahi, “Jail for ‘free visa’ traders,” Saudi Gazette, December 26, 2013, http://www.saudigazette.com.sa/index.cfm?method=home.regcon&contentid=20131226190605 (accessed August 20, 2014).

[25] Human Rights Watch interview with Amin, Haradh, Yemen, November 30, 2013.

[26] Human Rights Watch interview with Amin, Haradh, Yemen, November 30, 2013.

[27] Human Rights Watch interview with Mahmoud, Sanaa, November 26, 2013.

[28] Human Rights Watch interview with Mahmoud, Sanaa, November 26, 2013.

[29] Human Rights Watch interviews with deported Yemeni workers and officials, Sanaa and Haradh, Yemen, November 22-30, 2013; see Brian Whitaker, “Yemen and Saudi Arabia, A Review of Historical Relations,” al-bab.com, March 25, 2o15, http://www.al-bab.com/blog/2015/march/yemen-saudi-relations.htm#sthash.LzEV9QQC.IQLWLfGZ.dpbs (accessed April 15, 2015); Human Rights Watch, World Report 1990 (New York: Human Rights Watch, 1991), Middle East Watch Overview, http://www.hrw.org/reports/1990/WR90/MIDEAST.BOU.htm#P10_0.

[30] These events have already been reported by Human Rights Watch in “Saudi Arabia: Labor Crackdown Violence,” Human Rights Watch news release, December 1, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/11/30/saudi-arabia-labor-crackdown-violence.

[31] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Ethiopian worker in Riyadh (name withheld), November 18, 2013.

[32] “Saudi Arabia: Labor Crackdown Violence,” Human Rights Watch news release, December 1, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/11/30/saudi-arabia-labor-crackdown-violence.

[33] “Saudi Arabia: Labor Crackdown Violence,” Human Rights Watch news release, December 1, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/11/30/saudi-arabia-labor-crackdown-violence.

[34] “Saudi Arabia: Labor Crackdown Violence,” Human Rights Watch news release, December 1, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/11/30/saudi-arabia-labor-crackdown-violence.

[35] “Saudi Arabia: Labor Crackdown Violence,” Human Rights Watch news release, December 1, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/11/30/saudi-arabia-labor-crackdown-violence.

[36] “Saudi Arabia: Labor Crackdown Violence,” Human Rights Watch news release, December 1, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/11/30/saudi-arabia-labor-crackdown-violence.

[37] “Media Spokesman for Riyadh Police: Control Gained Over the Rioters in Manfouha Neighborhood and Arrest of 561 of the Inciters,” Saudi Press Agency, November 9, 2013, http://www.spa.gov.sa/details.php?id=1166241 (accessed February 9, 2015).

[38] “Illegal Workers Surrender in Saudi as 3 Ethiopians Die,” Agence France-Presse, November 12, 2013, http://tribune.com.pk/story/630995/illegal-workers-surrender-in-saudi-as-3-ethiopians-die/ (accessed February 9, 2015).

[39] “Sudanese Killed as Illegals Riot Again in Riyadh,” Arab News, November 14, 2013, http://www.arabnews.com/news/476836 (accessed February 9, 2015).

[40] Human Rights Watch interview with Nidal, Sanaa, November 25, 2013.

[41] Human Rights Watch interview with Nidal, Sanaa, November 25, 2013.

[42] Human Rights Watch interview with Nidal, Sanaa, November 25, 2013.

[43] Human Rights Watch interview with Ethiopian Consul in Sanaa, Sanaa, November 26, 2014.

[44] “Saudi Arabia: Labor Crackdown Violence,” Human Rights Watch news release, December 1, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/11/30/saudi-arabia-labor-crackdown-violence.

[45] MD Rasooldeen and Irfan Mohammed, “4,000 Ethiopians are ready for deportation,” Arab News, November 16, 2013, http://www.arabnews.com/news/478296 (accessed August 20, 2014).

[46] “Saudi Arabia: Labor Crackdown Violence,” Human Rights Watch news release, December 1, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/11/30/saudi-arabia-labor-crackdown-violence.

[47] “Saudi Arabia: Labor Crackdown Violence,” Human Rights Watch news release, December 1, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/11/30/saudi-arabia-labor-crackdown-violence.

[48] Ronaldo Z. Concha, “Consulate endorsing Filipinos in ‘tent city’ for deportation,” Saudi Gazette, February 2, 2014, http://www.saudigazette.com.sa/index.cfm?method=home.regcon&contentid=20140202194453 (accessed August 20, 2014).

[49] Abdullah Al-Thibyani, “One dead, 9 injured in deportation center riot,” Saudi Gazette, http://www.saudigazette.com.sa/index.cfm?method=home.regcon&contentid=20140304197557 (Accessed August 20, 2014).

[50] Human Rights Watch interview with Hassan, Haradh, Yemen, November 30, 2013.

[51] Human Rights Watch interview with Saleh, Haradh, Yemen, November 30, 2013.

[52] Human Rights Watch interview with Mohammed, Mogadishu, January 10, 2014.

[53] Human Rights Watch interview with Mohammed, Mogadishu, February 10, 2014.

[54] Human Rights Watch interview with Nur, Mogadishu, February 8, 2014

[55] Human Rights Watch interview with Somali health worker, Mogadishu, February 8, 2014.