Introduction

Thousands of journalists will attend the 2014 Winter Olympic Games in Sochi, Russia to report on the Games’ athletic events and ceremonies to millions of sports fans across the globe. The Russian government clearly hopes to elevate the country’s image as the host of a prestigious international event. But human rights abuses and controversies have plagued the preparations almost since the Olympics were awarded to Russia in 2007. Many of those abuses contradict the values in the Olympic Charter and its principle of placing “sport at the service of the harmonious development of humankind.” One aspect of these abuses—Russia’s harsh crackdown on media and civil society—has direct implications for journalists covering the Sochi Olympics.

Sochi will be the most expensive Games in Olympics history. But the monetary cost should not eclipse the significant human costs of preparations for the Games, which have been marred by exploitation, illegal detentions, and deportations of migrant construction workers engaged on Olympic venues and other sites in Sochi; forced evictions of Sochi residents and illegal land expropriations to make way for Olympics infrastructure; and harassment of journalists and civil society activists criticizing the preparations for the Games. Olympic construction has also compromised the health, safety, and property of many Sochi residents.

For the past six months, the preparations for the Games have also taken place in a storm of criticism regarding a law adopted by Russia’s parliament in June 2013 that discriminates against lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people, clashing with the Olympic Charter, which states that “discrimination is inconsistent with belonging to the Olympic movement.”

Although Russia deserves much credit for committing to an accessible environment for people with disabilities ahead of the 2014 Paralympic Games in Sochi, a significant gap remains between these commitments and the obstacles that remain for people with disabilities in Sochi.

This guide provides an overview of the context and risks for

journalists in covering the Olympics and the Paralympics in Sochi. It includes

background on the Olympics, human rights abuses related to preparations for the

Games, recent cases of interest, and a factual overview of several laws that

may affect reporting. The section on press freedom in Russia will be directly

relevant to reporters covering Russia beyond the Olympic sites.

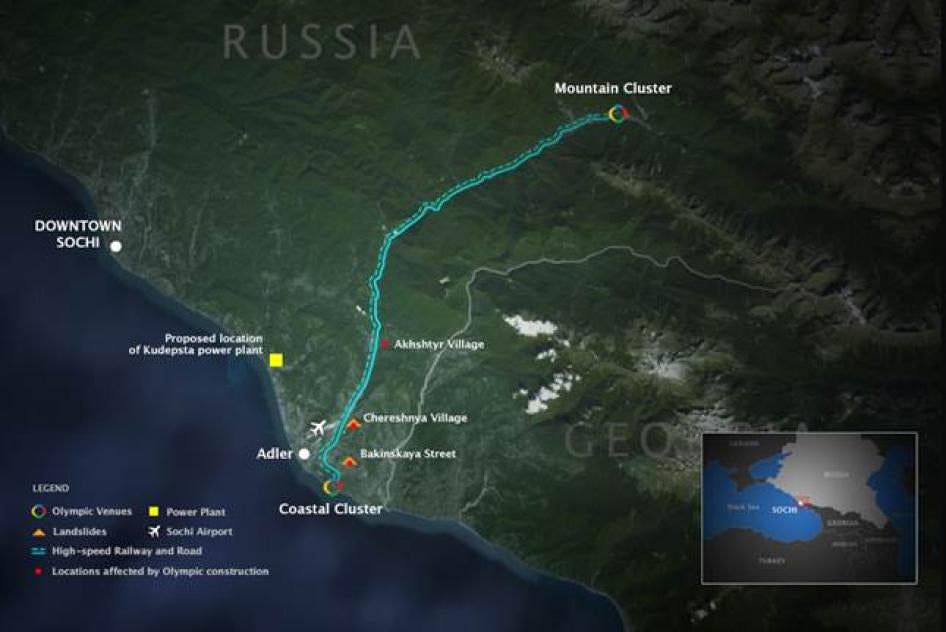

Maps and Satellite

Sources: Google Earth, maps.yandex.ru; Satellite Image © 2013 Cnes/Spot Image; Image © 2012 Human Rights Watch

The Sochi 2014 Winter Olympics and Paralympics will take place in a coastal cluster and a mountain cluster of venues linked by a new 48-kilometer high speed railway and road. Olympic preparations have caused landslides in two locations as well as destruction of drinking water wells and hazardous levels of dust in Akhshtyr. Some residents peacefully protesting a proposed power plant in Kudepsta have been arrested. Altogether 74,000 workers, including 16,000 foreign migrant workers, are building Olympic sites and infrastructure.

Sources: Google Earth, sochi2014.com; Sémhur; Satellite Image © 2013 DigitalGlobe; Image © 2013 Human Rights Watch

The Sochi 2014 Winter Olympic and Paralympic Games will take

place in two clusters of venues. The coastal cluster is home to the Central

Olympic (Fisht) Stadium and five ice arenas. The mountain cluster will host

skiing, snowboarding, and sliding events. Altogether 74,000 workers, including

16,000 foreign migrant workers, are building 136 Olympic sites.

Human Rights Abuses Linked to Preparations

for the 2014 Olympic Games

Background: Sochi

Located on southern Russia’s Black Sea coast, Sochi is a popular summer resort destination for Russian travelers. The Caucasus Mountains rise steeply to the north of Sochi and are home to several ski resorts.

Greater Sochi spans 145 kilometers along the Black Sea coast and has a land mass of 3,505 square kilometers. Its 2012 population was 437,000. Greater Sochi includes five administrative districts, one of which is the city of Sochi.

Hosting the Olympic Games in Sochi has required massive construction, possibly on a scale larger than previously seen in any Olympics[1] or in Russia.[2] The official Olympic program includes more than 230 construction projects involving sports venues, hotels, roads, transportation infrastructure, energy plants, and other facilities.[3]

The Olympic sports venues are divided into two groups: the “coastal cluster,” built along the Black Sea in the Imeritin lowlands in the Adler district of Sochi, are home to the Central Olympic Stadium, also known as the Fisht Stadium, which will host the opening and closing ceremonies, as well as five ice arenas, the Main Media Center, and numerous hotels and other infrastructure.[4] The “mountain cluster,” 48 kilometers from the coastal cluster, will host the alpine, skiing and snowboarding, sliding, and Nordic events, and will also be home to a smaller media center and other facilities.[5] Each cluster contains an Olympic Village, with the Main Olympic Village in the coastal cluster.[6]

Preparations also include numerous non-transportation and transportation infrastructure projects, such as a 48-kilometer combined high-speed road and rail link between the coastal and mountain clusters.[7]

According to the official Sochi 2014 website, Russia had “earmarked over US$30 billion for the construction of sports facilities and infrastructure in Sochi”[8] through a combination of public and private financing.[9] By January, the estimated cost of the Games had swelled to more than $50 billion.[10]

Exploitation of Migrant Workers

The transformation of Sochi from a summer resort town to an international

Olympic host has been made possible by tens of thousands of workers, a large

portion of whom are migrant workers from outside of Russia. Human Rights Watch

is not aware of any accurate Russian official data or other data on the total

number of workers in Sochi or the number of migrant workers. Recent media

reporting estimates the number of workers engaged on Olympics sites at around

95,000.[11]

Human Rights Watch has documented exploitation faced by many of these migrant workers, including on key Olympic sites such as the Central “Fisht” Stadium, the Main Olympic Village, and the Main Media Center, which will be the central work and residential venue for the thousands of journalists expected to cover the Sochi Games.

Olympstroy is the Russian state corporation responsible for realizing the program of construction of Olympic venues and development of Sochi as a resort.[12]

Exploitation faced by workers, including migrant workers, has included nonpayment of wages or excessive delays in payment of wages, including in some cases nonpayment of wages for weeks or months; employers’ failure to provide written employment contracts or copies of contracts; excessive working hours, such as 12-hour shifts without payment of overtime; few days off; and overcrowded employer-provided housing and inadequate employer-provided meals. Some employers withheld some migrant workers’ identity documents apparently as a coercive measure.

Under Russian law, it is illegal to withhold any portion of wages for over three months or to withhold wages altogether for more than two months. Russian law also requires that workers be paid overtime for hours worked beyond the 40-hour work week.

When workers complained to authorities about the abuses, the authorities failed to effectively investigate the complaints. In some cases, employers retaliated against migrant workers who complained about abuses by denouncing them to the authorities, resulting in the workers’ expulsion from Russia or by kicking workers out of employer-provided housing, leaving them struggling to find adequate housing. Police detained on false charges at least one worker who tried to complain about exploitation.

In September 2013, local authorities initiated large-scale raids to detain and deport irregular migrants. Many have been held in arbitrary and inhuman detention conditions. Local human rights activists have told Human Rights Watch that by December 2013, thousands of migrant workers had been expelled, many following hasty court processes and without access to lawyers or interpreters.

For more Human Rights Watch reporting on abuses against migrant workers in Sochi, please see:

Report:

- Race to the Bottom: Exploitation of Migrant Workers Ahead of Russia’s 2014 Winter Olympic Games in Sochi, February 6, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/reports/2013/02/06/race-bottom-0

News releases:

- “Russia: Sochi Migrant Workers Targeted for Expulsion,” October 3, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/node/119499

- “Russia: Worker Exploited on Olympic Venues is Detained,” April 11, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/04/11/russia-worker-exploited-olympic-venues-detained

- “Russia: Migrant Olympic Workers Cheated, Exploited,” February 6, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/02/06/russia-migrant-olympic-workers-cheated-exploited

Multimedia feature:

- People & Power: The 2014 Sochi Olympics, February 2013, http://www.hrw.org/people-and-power-2014-sochi-olympics

Forced Evictions

The Russian government has resettled some 2,000 families to make way for

Olympic venues and infrastructure. In several cases the government forcibly

evicted families and demolished their homes without providing compensation.

Most families whose homes were destroyed received some monetary compensation or

resettlement to newly built houses and apartments. However, the government did

not consistently implement a fair and transparent process for compensating

homeowners. In some cases, compensation did not reflect the full value of

owners’ property and some resettled residents also lost significant portions of

their livelihoods because they depended on agriculture or income from seasonal

rentals. Some families relocated to new homes challenged the quality of the

alternative housing and reported problems with heating, mold, and structural

soundness.

For more Human Rights Watch reporting on forced evictions and property-related issues in and around Sochi, please see:

News releases:

- “Russia: Forced Eviction Tramples Olympic Ideals,” September 19, 2012, http://www.hrw.org/news/2012/09/19/russia-forced-eviction-tramples-olympic-ideals

- “Russia: Halt House Demolition for Olympics,” September 14, 2012, http://www.hrw.org/news/2012/09/14/russia-halt-house-demolition-olympics

- “Creating Sochi Olympic site comes at high cost for local residents,” February 28, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/02/28/creating-sochi-olympic-site-comes-high-cost-local-residents

- “Russia: Halt Forced Eviction for Olympics Road,” October 22, 2012, http://www.hrw.org/news/2012/10/22/russia-halt-forced-eviction-olympics-road

- “An Olympic Demolition,” October 2, 2012, http://www.hrw.org/news/2012/10/02/olympic-demolition

Multimedia feature

- Russia: Forced Eviction, No Compensation, September 21, 2012, http://www.hrw.org/features/russia-forced-eviction-no-compensation

Letter to the IOC:

- Letter to International Olympic Committee, December 9, 2010, http://www.hrw.org/news/2010/12/09/letter-international-olympic-committee-update-human-rights-concerns-related-sochi-ga

Negative Impacts of Olympic Construction on Property and Health

Olympics-related construction has seriously compromised some Sochi residents’ health, safety, and private property. The authorities have not taken adequate steps to address these concerns, including through fair compensation or relocation of affected residents.

Landslides

Illegal dumping of Olympic construction waste above the village of Veseloe, Sochi, just north of the Coastal Cluster of Olympic venues, has caused landslides on Bakinskaya Street. Some homes have sunk into the ground and are severely tilted to one side. Some houses are not fit for habitation, but residents have not been offered any form of compensation for the damage to their homes. In the village of Chereshnya, not far from the Sochi airport, the construction of electrical lines as infrastructure for the Olympics caused landslides resulting in severe damage to houses and yards, including collapsing walls and cracks in foundations and walls. Homeowners have yet to be compensated or helped in the repair of their homes.

Acacia Street (Ulitsa Akatsia)

Construction for the M-27 Federal Highway, part of the Olympic program, went right through the front yard of families living at Acacia Street 5a, Adler, Sochi, near the Coastal Cluster of Olympic venues. Yet the authorities have refused to compensate or relocate approximately 40 people, including 11 children, living there. As a result of the road construction, the driveways and access points to the homes have been destroyed. The families have lived with ongoing truck and machinery noise and dust as a result of the massive construction project adjacent to their home, and flooding due to alterations in drainage from the elevated road on their property. The authorities also ordered the families to dismantle one of their outhouse toilets, claiming that it interfered with the road construction. Although families have been living in the home since the 1950s, the local authorities have never provided a public water supply, gas supply, or sewer services to the building. The residents have relied on outdoor kitchens, two communal outhouses, a bathhouse, etc. The families have been engaged in a protracted court battle with local and regional administrations and the company executing the road construction, all of whom have refused to take responsibility for providing compensation or relocation to the affected families.

Akhshtyr

Residents in Akhshtyr, a village located in the mountains between Adler and Krasnaya Polyana have been without a safe, regular drinking water supply for over five years as result of Olympic construction. In order to facilitate truck access to two quarries and a construction waste dump located above the village and used for Olympic construction, in 2008 the authorities paved the road running through the village and in the process destroyed residents’ main drinking water wells.

Villagers receive water delivered by truck once a week, which, they have told Human Rights Watch, is often not enough to meet their need for water, and also have no information about the source or quality of the delivered water. A water pump was built in 2011 but it does not function and is located at the edge of the village, whereas previously villagers had had access to a series of wells much closer to their homes.

In addition, heavy construction truck traffic accessing the quarries and the dump has posed risks to villagers’ health by generating huge amounts of thick dust that residents complain has adversely affected their health, properties, livestock, and agriculture. The years of heavy truck traffic have also caused some mountainsides to slide, damaging some homes.

The high-speed road and railway linking Adler and the Krasnaya Polyana venues have effectively cut off Akhshtyr from key public transportation links. There is no entry or exit onto the new federal highway from Akhshtyr, although it is located approximately one kilometer from the road. Residents are forced to rely on a narrow mountain road in poor condition to reach Adler. They have no easy access to other villages along the Mzymta River due to the absence of safe pedestrian crossings across the high-speed highway and the Mzymta River.

For more Human Rights Watch reporting on environmental destruction related to Olympics preparations, please see:

News release:

- “Creating Sochi Olympic site comes at high cost for local residents,” February 28, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/02/28/creating-sochi-olympic-site-comes-high-cost-local-residents

Multimedia feature:

- People & Power: The 2014 Sochi Olympics, February 2013, http://www.hrw.org/people-and-power-2014-sochi-olympics

Letters to the IOC:

- Letter to the International Olympic Committee, October 15, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/node/121168

- Letter to the International Olympic Committee: One-Year Countdown to the Sochi Games, January 22, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/node/121160

- Letter to the International Olympic Committee – Update on human rights concerns related to Sochi Games, December 9, 2010, http://www.hrw.org/news/2010/12/09/letter-international-olympic-committee-update-human-rights-concerns-related-sochi-ga

- Letter to the International Olympic Committee: Human Rights Concerns Related to Sochi Games, October 1, 2009, http://www.hrw.org/news/2009/10/01/letter-international-olympic-committee-human-rights-concerns-related-sochi-games

Restrictions on Freedom of Assembly, Association, and Expression

The International Olympic Charter requires all Olympic hosts to guarantee full press freedom.

However, Sochi authorities have harassed some activists and journalists

who criticized or expressed concerns about preparations for the Games.

Although media coverage of preparations for the Olympics is diverse, with some media establishments critical of preparation for the Olympics and others eschewing such coverage, Human Rights Watch spoke to editors, journalists, bloggers, and staff of news outlets who have faced threats and harassment after publicizing violations or concerns about the Olympics or other issues of concern in Sochi.

In November 2013, local authorities in Sochi and neighboring regions repeatedly harassed, detained, and questioned a crew from Norway’s s TV2 television station over the course of three days.

Some journalists told Human Rights Watch that local authorities sought to control negative or critical information about Sochi by pressuring editors to present Olympic preparations exclusively in a “positive” light. Criminal charges are being brought against at least two Russian journalists and the general director of a newspaper, apparently in retaliation for their work.

The police have allowed

some peaceful protests in Sochi on environmental and other issues. However,

environmental, human rights, and citizen activists have also been the targets

of attacks, detention for peaceful protests, and police searches. Two

nongovernmental organizations actively involved in documenting abuses committed

in the preparations for the Games were subject to intrusive government

inspections, and at least one organization had its email accounts examined by

the authorities.

For more Human Rights Watch reporting on restrictions on freedom of assembly, association, and expression in relation to the Olympics, please see:

News releases:

- “Russia: TV Crew Reporting on Sochi Olympics Harassed,” November 5, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/11/05/russia-tv-crew-reporting-sochi-olympics-harassed

- “Russia: Silencing Activists, Journalists Ahead of Sochi Games,” August 7, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/08/07/russia-silencing-activists-journalists-ahead-sochi-games

- “Russia: Rights Group Targeted in Sochi,” July 25, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/07/25/russia-rights-group-targeted-sochi

- “Russia: Security Forces Shut Down Protest at Sochi Olympic Site,” April 30, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/04/30/russia-security-forces-shut-down-protest-sochi-olympic-site

- “Russia: Arrests, Intimidation Mar Sochi Olympic Prep,” September 7, 2012, http://www.hrw.org/news/2012/09/06/russia-arrests-intimidation-mar-sochi-olympic-prep

Discrimination Against LGBT People

On June 29, 2013, President Vladimir Putin signed into law a billbanning the promotion of information among children about “nontraditional” sexual relationships, widely understood to mean LGBT relationships. The law sets out administrative (not criminal) sanctions, including heavy fines and the deportation and detention of foreigners found to have violated the law.

Beginning in 2006, similar laws outlawing “propaganda of homosexuality” among children were passed in 10 Russian regions. One more region, Kaliningrad, extended the ban also to adults. Also in June 2013, parliament passed a law banning adoption of Russian children by foreign same-sex couples and by unmarried individuals from countries where marriage for same-sex couples is legal. In September, Russian lawmakers briefly introduced a bill suggesting making homosexuality a legal ground for denial of child custody. The bill was later withdrawn reportedly in order to improve it.

The federal “propaganda” law specifically bans spreading among children information promoting attractiveness of “nontraditional sexual relationships” and providing a “distorted notion of social equivalence of traditional and nontraditional sexual relationships.” The ban applies to the press, television, radio, and the Internet.

The law is fundamentally discriminatory because it presumes that LGBT relationships do not have the same “social equivalency” as “traditional” relationships. The law treats information that puts LGBT relationships in a positive light as harmful to children. The same law sets out similar sanctions for promoting among children drug and alcohol use and suicide.

This discrimination contradicts the Olympic Charter, which states that “any form of discrimination … on grounds of race, religion, politics, gender or otherwise is incompatible with belonging to the Olympic Movement” (Sixth Fundamental Principle of Olympism). Articles 2-6 of the Olympic Charter further state that the IOC’s role is to, among other duties, “act against any form of discrimination affecting the Olympic Movement” (articles 2-6).

To date there has already been two known cases of prosecution under the federal law. On December 3, 2013, a Russian court found liable two LGBT activists for spreading LGBT “propaganda” next to a children’s library in Arkhangelsk, and on December 19 a court fined a third activist for holding a one-minute, one-man picket holding a poster that said, “Being gay and loving gays is normal; beating gays and killing gays is criminal.”

While prosecutions have so far been few, the law has had a harmful effect on Russia’s LGBT community. Public debates in the lead-up and aftermath of the law’s adoption have occasioned some instances of hateful, discriminatory, degrading rhetoric about LGBT people in Russia, including on state television stations. Many LGBT activists who track homophobic violence have told Human Rights Watch that attacks are also on the rise.

The international outcry against the law prompted President Putin to state publicly that all people are welcome in Sochi regardless of their sexual orientation. Deputy Prime Minister Dmitri Kozak provided assurances to the IOC that Russia will adhere to its obligation of nondiscrimination under the Olympic Charter, but also stated in a letter to the IOC, that the law will be applied “equally to all persons.”[13]

In response to Human Rights Watch’s concerns about the anti-LGBT law, the IOC has emphasized that the Games must be free from discrimination. However, it has refused to ask the Russian authorities to repeal the law and has said it is satisfied with the assurances the Russian authorities have provided.

For more Human Rights Watch reporting on discrimination of LGBT people, please see:

News releases:

- “Shocked by Russia’s Intolerance,” December 23, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/12/23/dispatches-shocked-russia-s-intolerance

- “Russia’s ‘Anti-Gay’ Olympics?” October 29, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/10/29/dispatches-russia-s-anti-gay-olympics

- “Dutch diplomat falls victim to Moscow’s anti-LGBT assault,” October 17, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/10/17/dispatches-dutch-diplomat-falls-victim-moscow-s-anti-lgbt-assault

- “Not So Much Reassurance from Russia,” August 22, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/08/22/dispatches-not-so-much-reassurance-russia

- “Every Color Flag But Rainbow at Sochi Olympics,” August 1, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/08/01/dispatches-every-color-flag-rainbow-sochi-olympics

- “Russia: Reject Discriminatory Bill,” June 24, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/06/23/russia-reject-discriminatory-bill

Letter to President Vladimir Putin:

- “Russia: Use Leadership to Repeal Discriminatory Propaganda Law,” September 5, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/09/05/russia-use-leadership-repeal-discriminatory-propaganda-law

The 2014 Winter Paralympics

Russia will host the XI Paralympic Games in March 2014. The 2014 Sochi Paralympic Games will include 1,350 athletes participating in five different sports: alpine skiing, biathlon, cross-country skiing, ice sledge hockey, and wheelchair curling. Russia’s decision to host the Paralympic Games reflects a significant shift in recognition and promotion of disability rights. When the Soviet Union hosted the 1980 Summer Olympics, it refused to host the Paralympic Games under the rationale that there were “no disabled citizens in the USSR.”

The Russian government has widely publicized the Paralympic Games as part of a nationwide effort to create a more accessible environment and greater respect for people with disabilities in Sochi and across Russia. However, people with disabilities have been only marginally involved in planning for the Paralympics. Sochi residents with disabilities continue to face obstacles in accessing transportation, public and private buildings, employment, and healthcare. Many buildings are accessible in name only. Pedestrian underpasses have been fitted with wheelchair lifts that require licensed operators, who are absent. Many sidewalks are not lowered for wheelchair access, including those where bus stops are located. Wheelchair users cannot always access bus stops in order to ride the 108 accessible buses that the city administration has listed among its key accomplishments.

As a public voice on Russia’s progress toward creating a more accessible environment in Sochi, the International Paralympic Committee can play a pivotal role in holding Russia accountable for its obligations as a Paralympic host country. Until recently, the committee had expressed only unreserved praise for Russia’s efforts to create a barrier-free environment without acknowledging any of the shortcomings. In November 2013, the committee moderated its praise to remind the Russian authorities that the Paralympic Games will be “judged only by the legacy they leave" and to remind Russia that the kind of progress on accessibility that has been made in Sochi needs to be replicated throughout Russia.

There are at least 13 million people with disabilities in Russia today. While Russia has taken some important steps in recent years to advance protections of the rights of people with disabilities, including the ratification of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), the Russian government has much more to do to ensure the right to an accessible environment for people with disabilities. People with physical, vision, auditory, intellectual, or psychosocial disabilities face barriers to accessing transportation, public and private buildings, and healthcare. People with disabilities also face stigma, which oftentimes bars them from adequate educational opportunities and full participation in their communities.

For more Human Rights Watch reporting on accessibility of facilities for the Paralympics and in Russia, please see:

Report:

- Barriers Everywhere: Lack of Accessibility for People with Disabilities in Russia , September 11, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/reports/2013/09/11/barriers-everywhere-0

News releases:

- 100 days Before Paralympics in Sochi, Barriers Remain for Disabled Athletes, December 4, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/12/04/100-days-paralympics-sochi-barriers-remain-disabled-athletes

- “Russia’s Hurdles for People with Disabilities,” September 23, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/tr/node/119222

- “Russia: End Hurdles for People With Disabilities,” September 11, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/de/node/118682

- “Witness: Trapped in His Own Apartment – Kolya’s Story,” September 11, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/09/11/witness-trapped-his-own-apartment-kolya-s-story

- “‘You’re Disabled, You Can’t Fly!’ Or Can You?” August 23, 2012, http://www.hrw.org/news/2012/08/23/you-re-disabled-you-can-t-fly-or-can-you

- “Russia: Reform Domestic Laws on Disability Rights,” May 4, 2012, http://www.hrw.org/news/2012/05/04/russia-reform-domestic-laws-disability-rights

Multimedia feature:

- Breaking Barriers: The Disability Rights Movement in Russia, August 2012, http://www.hrw.org/features/russia-breaking-barriers

Human Rights Abuses in Russia

The 18 months leading up to the Games have coincided with the worst crackdown on human rights in Russia’s post-Soviet era. The authorities unleashed this crackdown in May 2012, almost immediately following Vladimir Putin’s return to the presidency. They have introduced a series of restrictive laws, harassed, intimidated, and in several cases imprisoned political activists, interfered in the work of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and sought to cast government critics as clandestine enemies, thereby threatening the viability of Russia’s civil society. Other human rights concerns also persist, including the authorities’ harassment of migrants and an ongoing insurgency in the North Caucasus.

For an interactive map of human rights issues in Russia, please see:

- Russia: Beyond the Torch’s Glow, October 2013, http://www.hrw.org/olympic-torch-human-rights-route

Press and Civil Society Crackdown

Since Putin’s return to the presidency, a series of draconian laws were adopted that place restrictions on public assemblies, re-criminalize libel, criminalize religious insult, introduce additional restrictions on Internet content, expand the definition of treason, and, as noted above, ban “propaganda” for “nontraditional sexual relations.” A nationwide government campaign to force nongovernment groups that accept foreign funding and engage in vaguely defined “political activity” to register as “foreign agents” aims to curtail a broad range of work by independent organizations. From March to May 2013, authorities subjected over a thousand of NGOs to invasive inspections to intimidate groups and pressure them to register as “foreign agents.”

As a result, the authorities filed administrative lawsuits against at least nine inspected organizations and at least five administrative cases against leaders of these groups for refusing to register as “foreign agents”. They have also filed civil suits against at least four organizations. By December 2013, the authorities suspended two groups and at least another three chose to wind up operations to avoid further repressive legal actions. The prosecutor’s office ordered dozens of other groups to register as “foreign agents” or warned they might need to do so. The groups are fighting these orders and warnings through courts.

For more Human Rights Watch reporting on restrictive legislation, please see:

Report:

- Laws of Attrition: Crackdown on Russia’s Civil Society after Putin’s Return to the Presidency, April 24, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/reports/2013/04/24/laws-attrition

News releases:

- “Foreign agents” law:

- “Russia: New ‘Foreign Agents’ Law Ruling,” December 14, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/12/13/russia-new-foreign-agents-law-ruling

- “Russia: First Ruling on Civil Suit Under ‘Foreign Agents’ Law,” December 6, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/12/06/russia-first-ruling-civil-suit-under-foreign-agents-law

- “Russia: Drop Suits Against Independent Groups,” November 6, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/11/05/russia-drop-suits-against-independent-groups

- “Russia: ‘Foreign Agents’ Law Hits Hundreds of NGOs,” updated December 26, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/11/29/russia-foreign-agents-law-hits-hundreds-ngos-updated-november-29-2013

- “Russia: repeal ‘foreign agents’ measure,” November 21, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/11/20/russia-repeal-foreign-agents-measure

- “Russia: Voters’ Group First Victim of ‘Foreign Agent’ Law,” July 3, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/07/03/russia-voters-group-first-victim-foreign-agent-law

- “Russia: Harsh Toll of ‘Foreign Agents’ Law,” June 26, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/06/25/russia-harsh-toll-foreign-agents-law

- “Russia’s civil society crackdown continues,” September 25, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2012/09/25/russias-civil-society-crackdown-continues

o “Russia: Reject Proposed Changes to Rules on Foreign-Funded NGOs,” July 13, 2012, http://www.hrw.org/news/2012/07/13/russia-reject-proposed-changes-rules-foreign-funded-ngos

- “Anti-Magnitsky” law:

- “Russia: Reject Adoption Ban Bill,” December 21, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/pt/node/112180

- Expansion of the definition of treason:

- “Russia: New Treason Law Threatens Rights,” October 23, 2012, http://www.hrw.org/news/2012/10/23/russia-new-treason-law-threatens-rights

- “The Kremlin May Call It Treason,” September 28, 2012, http://www.hrw.org/es/node/110422

- Reintroduction of criminal libel:

- “Russia: Criminal Libel Law a Blow to Free Expression,” July 16, 2012, http://www.hrw.org/news/2012/07/16/russia-criminal-libel-law-blow-free-expression

- Internet content restrictions:

- “Russia: Internet Legislation Merits Greater Scrutiny Before Passage,” July 11, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2012/07/11/russia-internet-legislation-merits-greater-scrutiny-passage

- Restrictions on freedom of assembly:

- “Russia: Reject Restrictions on Peaceful Assembly,” June 8, 2012, http://www.hrw.org/news/2012/06/08/russia-reject-restrictions-peaceful-assembly

For more Human Rights Watch reporting on the crackdown on freedoms of assembly, association, and expression, please see:

Press releases:

- Pussy Riot

- “Russia: Band Members’ Conviction a Blow to Free Expression,” August 17, 2012, http://www.hrw.org/news/2012/08/17/russia-band-members-conviction-blow-free-expression

- “Russia: Jailed Pussy Riot Member Cites Abuse,” September 27, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/09/27/russia-jailed-pussy-riot-member-cites-abuse

- Greenpeace

- “Russia: Drop Piracy Charges Against Greenpeace,” updated November 29, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/09/30/russia-drop-piracy-charges-against-greenpeace

- “Neither Pirates nor Hooligans,” November 19, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/11/19/dispatches-neither-pirates-nor-hooligans

- LGBT rights

- “Anti-gay law shames Putin’s Russia,” September 13, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/09/13/anti-gay-law-shames-putin-s-russia

- “Russia: Investigate Attacks on Peaceful LGBT Demonstrators in St. Petersburg,” press release, July 10, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/07/10/russia-investigate-attacks-peaceful-lgbt-demonstrators-st-petersburg

- “Russia: Investigate Homophobic Motivation for Killing,” May 16, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/05/15/russia-investigate-homophobic-motivation-killing

- “Russia: Investigate Attack on Gay-Friendly Bar,” October 12, 2012, http://www.hrw.org/news/2012/10/12/russia-investigate-attack-gay-friendly-bar

Multimedia feature:

- Acting Up: Russia’s Civil Society, December 2011, http://www.hrw.org/features/russia-civil-society

Migrants’ Rights

The exploitation against migrant workers in Sochi, described above, is part of a broader pattern of abuse of migrant workers in Russia, which Human Rights Watch documented in a 2009 report. Also, in the past year, an aggressive, xenophobic campaign against migrants, and especially migrant workers, has been under way in Russia, particularly in Moscow, St, Petersburg, and other large cities. Police engage in ethnic profiling in Moscow, Sochi, and other cities with large populations of migrant workers. Since summer 2013, hundreds, perhaps thousands, have been arbitrarily detained, often based on nothing more than their non-Slavic appearance. Some are treated poorly, held in inhuman conditions, and denied access to legal counsel. Many are then deported, based on rubber-stamp court rulings and often without getting paid for their work.

The issue of “irregular” migration and internal migration has risen up the political agenda in the country, as Russian authorities have increasingly scapegoated migrants, expressing concerns about the supposed rise in “ethnic crime” (relevant police statistics evidence no such rise) and the migrants’ alleged inability to adapt to Russian cultural and behavioral norms. Xenophobic discourse in the Russian media, including anti-migrant comments by high-level officials are contributing to a climate of xenophobia in Russia and xenophobic violence is on the rise.

For Human Rights Watch reporting on migrants’ rights, please see:

Reports:

- Race to the Bottom: Exploitation of Migrant Workers Ahead of Russia’s 2014 Winter Olympic Games in Sochi, February 6, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/reports/2013/02/06/race-bottom-0

- “Are You Happy to Cheat Us?”: Exploitation of Migrant Construction Workers in Russia, February 10, 2009, http://www.hrw.org/reports/2009/02/10/are-you-happy-cheat-us-0

News releases:

- “An Open Invitation to Violence in Russia?” October 28, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/10/28/dispatches-open-invitation-violence-russia

- “Russia: Sochi Migrant Workers Targeted for Expulsion,” October 2, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/10/02/russia-sochi-migrant-workers-targeted-expulsion

- “Russia: Mass Detention of Migrants,” August 9, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/08/08/russia-mass-detention-migrants

- “Russia: Reported Roundup of Tajik Migrants,” November 15, 2011, http://www.hrw.org/news/2011/11/15/russia-reported-roundup-tajik-migrants

Multimedia feature:

- People & Power: The 2014 Sochi Olympics, February 2013, http://www.hrw.org/people-and-power-2014-sochi-olympics

- Unspeakable Things: Migrant Workers in Russia, February 10, 2009, http://www.hrw.org/features/unspeakable-things-migrant-workers-russia

Insurgency in the North Caucasus

For years, Russian authorities have been battling an Islamist insurgency in Russia’s North Caucasus republics. The insurgents’ tactics have ranged from attacks on military and police personnel to assassinations of officials, mostly within the North Caucasus, to targeting of civilians in the North Caucasus and beyond, of which the December bombings in Volgograd were only the most recent examples. Government abuses in counter-insurgency operations include enforced disappearances, torture, and extrajudicial executions. These abuses go unpunished. Killings of activists and journalists also remain unpunished.

According to Caucasian Knot, an independent online media portal, in thefirst six months of 2013, 242 people were killed in the North Caucasus region, including 46 civilians, and 253 people were wounded, including 83 civilians. More than 60 percent of all casualties occurred in Dagestan. Ramazan Abdulatipov, Dagestan’s new leader, abandoned “soft power” counterinsurgency policies of his predecessor, which included a commission “For return of insurgents to peaceful life” and promotion of dialogue with Salafi, or ultraconservative, Muslims. Instead to combat “extremists,” the authorities condoned the rise of people’s militias, which have driven some Salafis to flee their homes. A journalist well known for exposing counter-insurgency related abuses, Akhmednabi Akhmednabiev, was killed in Dagestan in July 2013 and no effective investigation has been conducted into his murder. Akhmednabiev’s killing was starkly reminiscent of the killing of Gadzhimurad Kamalov, founder and publisher of a prominent Dagestani independent newspaper, Chernovik, two years previously. Both Kamalov and Akhmednabiev had received death threats and reported them to police authorities to little response.

The European Court of Human Rights has issued over 200 judgments on cases of grave human rights violations from Chechnya. However, these legally binding judgments have seen no effective implementation. The work climate for human rights defenders in Chechnya remains very hostile. Women are forced to wear headscarves in public buildings, and according to local women’s rights activists, “honor” killings are on the rise in Chechnya.

For more Human Rights Watch reporting on the North Caucasus, please see:

Report:

- “You Dress According to Their Rules”: Enforcement of an Islamic Dress Code for Women in Chechnya, March 10, 2011, http://www.hrw.org/reports/2011/03/10/you-dress-according-their-rules-0

News releases:

- “Russia: Journalist Killed,” July 9, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/07/09/russia-journalist-killed

- “Virtue Campaign on Women in Chechnya under Ramzan Kadyrov,” October 29, 2012, http://www.hrw.org/news/2012/10/29/virtue-campaign-women-chechnya-under-ramzan-kadyrov

- “Russia: Strictly Respect Rights in Dagestan Killing Inquiry,” August 29, 2012, http://www.hrw.org/news/2012/08/29/russia-strictly-respect-rights-dagestan-killing-inquiry

- “Russia: Protect Human Rights Defenders in Chechnya,” June 7, 2012, http://www.hrw.org/news/2012/06/07/russia-protect-human-rights-defenders-chechnya

- “Russia: Chechnya Enforcing Islamic Dress Code,” March 10, 2011, http://www.hrw.org/news/2011/03/10/russia-chechnya-enforcing-islamic-dress-code

The International Olympic Committee

and the 2014 Sochi Games

Since 2008, Human Rights Watch has regularly shared with the International Olympic Committee (IOC) information about human rights concerns related to the preparations for the Games. To its credit, the IOC has been open to receiving this information and has been open to dialogue with Human Rights Watch. However, its response to our reports has largely consisted in passing on concerns to the Sochi 2014 Organizing Committee, which has, in turn, assured the IOC that reports of abuses were being handled. To our knowledge, the IOC has not sought to verify, other than through correspondence with the Organizing Committee, whether the abuses or other problems have been adequately resolved. Instead, the IOC appears to accept at face value the Russian authorities’ explanations and assurances, even when that information has proven to be inaccurate or misleading.

For more Human Rights Watch reporting on the role of the IOC, please see:

News releases:

· “Russia: Abuses Tarnish 100-Day Countdown to Sochi,” October 28, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/node/120181

· “Olympics: Rights Agenda for New IOC President Bach,” September 9, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/node/118747

· “Russia: IOC Should Address Deteriorating Rights Climate,” October 11, 2012, http://www.hrw.org/news/2012/10/11/russia-ioc-should-address-deteriorating-rights-climate

· “Olympic Glow Should Not Mask Rights Abuses,” October 23, 2009: http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/10/09/AR2009100903413.html

Letters to the IOC:

· IOC: Presidency Candidates Face Critical Questions Regarding Human Rights, August 2, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/node/118123

· IOC: Discrimination Against LGBT People at Odds with Olympic Charter, Human Rights Protections, June 19, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/node/117891

· Letter to the International Olympic Committee – Update on human rights concerns related to Sochi Games, December 9, 2010, http://www.hrw.org/news/2010/12/09/letter-international-olympic-committee-update-human-rights-concerns-related-sochi-ga

What is the Olympic Charter?

The Olympic Charter acts as a “constitution” or rulebook for the Olympic Games and the Olympic Movement: it sets out principles that should be obeyed. The charter contains the fundamental principles of Olympism and the rules and bylaws adopted by the International Olympic Committee (IOC). The charter regulates the way in which the organization functions and establishes the conditions for the celebration of the Olympic Games.

Human rights organizations have used the charter to hold the IOC accountable and to demand that host countries meet benchmarks for compliance with human rights principles and with the Olympic Charter.

To read the Olympic Charter, please visit:

· http://www.olympic.org/Documents/olympic_charter_en.pdf

The “Fundamental Principles of Olympism:”

Mission and role of the IOCThe mission of the IOC is to promote Olympism throughout the world and to lead the Olympic Movement. According to the Olympic Charter, the IOC’s role includes:

Mission and role of the National Olympic Committees (NOCs)The mission of the NOCs is to develop, promote, and protect the Olympic Movement in their respective countries. Their role is:

Media Coverage of the Games

Who is Thomas Bach?Elected in September 2013, Thomas Bach is the 9th president of the IOC, replacing Jacques Rogue. Bach, 59, was born in Germany and has been a member of the IOC’s executive board since 1996, holding several positions, including vice-president. As a candidate, Bach promised to ensure the integrity and credibility of the IOC and the compliance of the Olympic Charter. |

The Olympics and IOC Rights Reform

Human Rights Watch has documented serious human rights abuses in conjunction with preparations for the Olympic Games both in Sochi ahead of 2014 Winter Olympics and in Beijing ahead of the 2008 Summer Olympics. This research strongly suggests that awarding the Games to a country with a poor record on human rights and the rule of law can result in the Olympic preparations being a source of human rights abuse.

For this reason, Human Rights Watch recommends that, from the bid process through the end of the Games, future Olympic host countries should commit to ensuring human rights protections in conjunction with their preparations for the Games, and the IOC should monitor implementation of those commitments.

When corruption and doping once threatened the integrity of the Olympic movement, the IOC took adopted reforms to address these practices, for example by setting up an anti-doping agency for monitoring and sanctioning improper conduct. Because serious human rights abuses linked to the preparations for the Games pose similar risks to the integrity Olympic movement, the IOC should also establish a monitoring body to address violations as they happen—in the same way the IOC monitors completion of sporting venues.

In order to ensure that future host countries fully respect the Olympic Charter, in February 2009 Human Rights Watch submitted to the Olympic Congress a proposal to integrate human rights within the Olympic Movement. Human Rights Watch’s proposal called for the creation of an IOC standing committee on human rights, which would help set and monitor human rights benchmarks related to media freedom, labor rights, freedom of expression and civil liberties. This committee could also serve a vital function to further communication between the IOC and rights organizations or individuals who have human rights concerns. Human Rights Watch also urges that future Host City Contracts include specific guarantees that human rights be addressed and respected.

To read the complete text of the proposal, please see :

· https://www.hrw.org/news/2009/02/23/human-rights-watch-submission-2009-olympic-congress

In response to this proposal, in September 2011 the IOC issued Recommendation 30, which states, “The IOC will intervene at the OCOG [Organizing Committee for the Olympic Games] level in the event of serious abuses, such as mistreatment of people displaced due to Olympic venue construction; abuse of migrant workers at Olympic venue construction sites; child labor; improper restrictions on the media’s freedom to cover the Games….”

However, the case of Sochi shows that this level of involvement has been insufficient to rectify ongoing and serious human rights concerns and highlights the need for long-term institutional reform within the Olympic Movement, including human rights commitments from host countries and monitoring on the part of the IOC.

For more Human Rights Watch reporting on IOC reform, please see:

News releases:

· “New IOC President Should Learn Lessons from Sochi,” September 5, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/node/118575

· “Olympics: Next IOC Leader Should Back Rights Reforms,” August 23, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/08/23/olympics-next-ioc-leader-should-back-rights-reforms

· “Rights at Stake in Olympic Leadership Race,” August 13, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/08/13/rights-stake-olympic-leadership-race

· “Sochi a Chance for Thomas Bach,” August 8, 2013, https://www.hrw.org/news/2013/08/08/sochi-chance-thomas-bach-make-his-olympic-presidency-mark

Printed in the United States of America

Cover design by Rafael Jimenez

Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all.

Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich.

For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org

[1] Galina Masterova, “Sochi: An Olympic makeover,” Russia Beyond the Headlines, February 23, 2010, http://rbth.ru/articles/ 2010/02/23/230210_olympic.html (accessed July 16, 2012), and Jim Caple, “With London Around the Corner, Sochi Building Its Dream Project,” ESPN, July 16, 2012, http://espn.go.com/blog/olympics/post/_/id/2850/with-london-around-corner-sochi-building-its-dream-project (accessed August 9, 2012).

[2] The president of the Sochi 2014 Organizing Committee has called the 2014 Olympics preparations “the largest [construction] project in Russia’s history.” Ruslan Aliev, “Sochi has Surpassed St. Petersburg,” [Сочи превзошел Санкт-Петербург], Gazeta.ru , October 6, 2012, http://www.gazeta.ru/sport/2012/10/06/a_4803493.shtml (accessed October 24, 2012).

[3] Program of Olympics Venues Construction and Development of Sochi City as a Mountain Climatic Resort, Russian Federal Government, approved by decree December 29, 2007, with amendments, http://www.scos.ru/common/upload/ENG/Programm_eng_ revised.pdf (accessed October 24, 2012). Olympstroy has numerous public and private partners including national economic ministries and major joint-stock companies. A full list of partners can be found at: http://www.scos.ru/en/about/our_partners/interaction_and_coordination/index.php#3.

[4] “Fisht Olympic Stadium,” Sochi2014.com, http://sochi2014.com/en/objects/sea/central_stadium/, and “Coastal Cluster,” Sochi2014.com, http://sochi2014.com/en/objects/sea/ (both accessed July 5, 2012).

[5] “Mountain Cluster,” Sochi2014.com, http://sochi2014.com/en/objects/mountain/, and “Laura Cross-Country Ski & Biathlon Center,” Sochi2014.com, http://sochi2014.com/en/objects/mountain/ski/ (both accessed July 5, 2012).

[6] “Venues: Interactive map,” Sochi2014.com, http://www.sochi2014.com/en/objects/ (accessed July 16, 2012). There will be a third Olympic Village near the mountain cluster. “Three Olympic Villages with space for 6,700 people are being brought to Sochi,” [Три олимпийские деревни на 6,700 мест возводят в Сочи], Administration of Sochi, August 7, 2012, http://www.

sochiadm.ru/press_office/news/detail.php?ID=8329 (accessed October 2, 2012).

[7] See: “Rail,” Sochi2014.com, http://sochi2014.com/en/legacy/infrastrucrture/transport/railway/; “Air,”Sochi2014.com, http://sochi2014.com/en/legacy/infrastrucrture/transport/avia/; and “Auto,” Sochi2014.com, http://sochi2014.com/en/ legacy/infrastrucrture/transport/auto/ (accessed February 19, 2012).

[8] “Dmitry Medvedev promises modern infrastructure for Olympic host city residents,” Sochi2014.ru, January 4, 2011, http://www.sochi2014.com/en/sochi-live/news/38367/ (accessed July 5, 2012).

[9] Program of Olympics Venues Construction and Development of Sochi City as a Mountain Climatic Resort, Russian Federal Government, approved by decree December 29, 2007, with amendments, http://www.scos.ru/common/upload/ENG/Programm_eng_ revised.pdf, pp. 4-7. According to media reports, the combined public and private financing of venues has led “to an apparent lack of cohesion and organization at the many different construction sites.” Justin Davis, “Russians insist Sochi Olympic venues on track,” Agence France-Presse, February 14, 2012, http://www.google.com/hostednews/afp/article/ ALeqM5iD52d-PkiIyzaa7EkhBWFrjUfuNw?docId=CNG.1b7c0b5abee48c6a1dfe4025be09a1d9.2b1 (accessed February 19, 2012).

[10] Joshua Yaffa, “The Waste and Corruption of Vladimir Putin’s 2014 Winter Olympics,” Businessweek, January 2, 2014, http://www.businessweek.com/articles/2014-01-02/the-2014-winter-olympics-in-sochi-cost-51-billion (accessed January 7, 2014).

[11] Paul Sonee, “Workers Readying Winter Games Say Wages Are on Ice,” Wall Street Journal, December 23, 2013, http://sports.nationalpost.com/2013/11/29/russian-president-vladimir-putin-effectively-cancels-christmas-for-sochi-workers-ahead-of-2014-olympics/ (accessed January 7, 2013).

[12] State Corporation Olympstroy [Олимпстрой государственная корпорация], “Activities [Деятельность],” http://www.sc-os.ru/ru/activity (accessed December 5, 2013).

[13] Samantha Stainburn, “Russia defends anti-gay law in letter to the International Olympic Committee,” Global Post, August 22, 2013, http://www.globalpost.com/dispatch/news/regions/europe/russia/130822/russia-defends-anti-gay-law-letter-the-international-olym (accessed January 8, 2013).