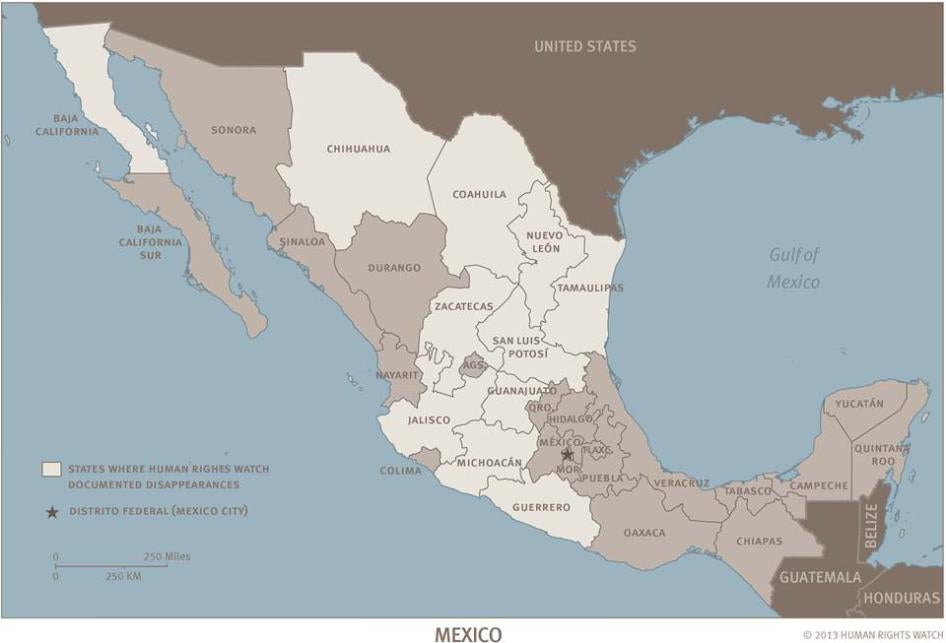

Map: States Where Human Rights Watch Documented Disappearances

Executive Summary

When Enrique Peña Nieto took office on December 1, 2012, he inherited a country reeling from an epidemic of drug violence that had taken the lives of more than 60,000 Mexicans in six years. The “war on drugs” launched by his predecessor, Felipe Calderón, had produced disastrous results. Not only had it failed to rein in the country’s powerful criminal groups, but it had led to a dramatic increase in grave human rights violations committed by the security forces sent to confront them. Rather than strengthening public security, these abuses had exacerbated a climate of violence, lawlessness, and fear.

Throughout most of his presidency, Calderón denied security forces had committed any abuses, despite mounting evidence to the contrary. Only in his final year did he acknowledge that human rights violations had occurred, and take a handful of positive—though very limited—steps to curb some abusive practices. However, he failed to fulfill his fundamental obligation to ensure that the egregious violations committed by members of the military and police were investigated and the perpetrators brought to justice.

That responsibility now falls to President Peña Nieto. And nowhere is it more urgent than in cases where people have been taken against their will and their fate is still unknown. What sets these crimes apart is that, for as long as the fate of the victim remains unknown, they are ongoing. Each day that passes is another that authorities have failed to find victims, and another day that families continue to suffer the anguish of not knowing what happened to a loved one.

Human Rights Watch has documented nearly 250 such “disappearances” that have occurred since 2007. In more than 140 of these cases, evidence suggests that these were enforced disappearances—meaning that state agents participated directly in the crime, or indirectly through support or acquiescence. These crimes were committed by members of every security force involved in public security operations, sometimes acting in conjunction with organized crime. In the remaining cases, we were not able to determine based on available evidence whether state actors participated in the crime, though they may have.

In nearly all of these cases, authorities failed to promptly and thoroughly search for the victims or investigate the cases. Prosecutors rarely carried out basic investigative steps crucial to finding missing persons, too often opting instead to blame the victims and, reflecting the low priority they place on solving such crimes, telling families to conduct the searches on their own. When prosecutors did investigate, their efforts were undermined by delays, errors, and omissions. Searches and investigations were further hindered by structural problems such as overly narrow laws and the lack of critical tools like a national database of the disappeared.

The inept or altogether absent efforts of authorities to find people who are taken add to the suffering of victims’ families, for whom not knowing what happened to their loved ones is a source of perpetual anguish. Many relatives put aside everything else in their lives to search for the missing, a quest they feel they cannot abandon until they learn the truth. Making matters worse, victims’ families may lose access to basic social services and benefits—such as healthcare and childcare—tied to the victim’s employment, forcing them to fight costly and emotionally-draining battles to restore the benefits.

The nearly 250 cases documented in this report by no means represent all the disappearances that occurred in Mexico during the Calderón administration. Quite the opposite, there is no question that there are thousands more. Officials in Coahuila, for example, told Human Rights Watch that 1,835 people had disappeared in that state alone from December 2006 to April 2012. More alarming still, a provisional list compiled by the Ministry of the Interior and the Federal Prosecutor’s Office—which was leaked in November 2012—contains the names of more than 25,000 people who were disappeared or went missing during the Calderón years, and whose fates remain unknown. While the list’s information is incomplete and its methodology flawed, the number leaves little doubt as to the unprecedented scale of the current wave of disappearances.

During the years the Calderón administration ignored this mounting “disappearance” problem, the country failed to take serious steps to address it. The result was the most severe crisis of enforced disappearances in Latin America in decades. If the Peña Nieto administration repeats this mistake—and fails to set out a comprehensive, effective plan to investigate past disappearances and help prevent them in the future—cases of disappearances will almost certainly continue to mount. And thousands of victims’ families will continue to endure the agony of not knowing what happened to their loved ones.

A different approach is possible. Human Rights Watch witnessed this in the state of Nuevo León, where government officials and prosecutors, responding to pressure from victims’ families and human rights defenders, have broken with a pattern of inaction and incompetence, and begun to seriously investigate a select group of disappearances. Their efforts have helped win back the trust of victims’ relatives and, with it, their collaboration, which has proven critical to identifying new leads and gathering valuable evidence. While at this time results in these investigations remain limited and very few of the disappeared have been found, the approach provides a blueprint for overcoming some of the greatest obstacles to resolving disappearance cases.

Ultimately, the success of this and other state-level efforts will depend in large measure on whether the federal government is willing and able to do its part. This is, after all, a national problem, often involving federal security forces and organized crime groups that operate across state lines. The mass graves discovered in one state may well contain the remains of people disappeared in others. A comprehensive strategy—rooted in nationwide efforts such as the creation of unified, accurate databases of the disappeared and unidentified remains—is critical to give prosecutors, law enforcement officials, and families the tools they need to find the missing and bring those responsible for their disappearances to justice.

Enforced Disappearances

Human Rights Watch has documented 249 disappearances committed in Mexico since December 2006. In 149 of these cases, we found compelling evidence that state actors participated in the crime, either acting on their own or collaborating with criminal groups. Members of every security force engaged in public security operations —the Army and the Navy, the Federal Police, and state and municipal police—are implicated in these 149 cases.

The majority of the likely enforced disappearance cases we documented follow a pattern. Members of security forces arbitrarily detain individuals without arrest orders or probable cause. In many cases, these detentions occur in victims’ homes, in front of family members; in others, they take place at security checkpoints, at workplaces, or in public venues, such as bars. Soldiers and police who carry out these detentions almost always wear uniforms and drive official vehicles. When victims’ relatives inquire about detainees’ whereabouts at the headquarters of security forces and public prosecutors’ offices, they are told that the detentions never took place.

In some instances, evidence suggests that a specific security force carried out multiple disappearances using the same tactics, within a narrow period of time, and in the same geographical area. For example, Human Rights Watch collected witness testimony and photographic and video evidence showing that members of the Navy committed more than 20 abductions in June and July 2011, in the border states of Coahuila, Nuevo León, and Tamaulipas. Almost all of these people were arbitrarily detained by members of the Navy in their homes. The Navy initially denied having taken the men, only to contradict itself later by admitting in news releases that it had come into contact with several of the men before they disappeared. The individuals have not been seen since they were arrested. The common modus operandi in these cases suggests that these crimes may have been planned and coordinated, or at the very least could not have taken place without the knowledge of high-ranking Navy officials.

In cases where state agents work with organized crime in carrying out disappearances, the collaboration may take one of many different forms. Most commonly, security forces arbitrarily detain victims and then hand them over to criminal groups. Police, soldiers, and investigators may also work with criminal groups to extort the families of the victims, or tell those groups when victims’ relatives report disappearances—information that abductors then use to harass and intimidate families. In more than a dozen cases, evidence pointed to state agents taking advantage of information obtained from families to pose as kidnappers and demand ransom from victims’ relatives.

In addition to these enforced disappearance cases, we also documented 100 other cases of disappearances. In these cases, individuals were taken against their will—often by armed men—and their whereabouts remain unknown. We are not aware of evidence of the participation of state actors in these crimes. However, given the widespread involvement of police and military personnel evidenced in other disappearances, in the absence of thorough investigations, it is impossible to rule out the participation of state actors in these cases. In any case, although these “disappearances” carried out purely by private individuals as a criminal act—unlike “enforced disappearances”—do not fall under the definition of the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearances, the state has a responsibility to investigate all disappearances, regardless of the perpetrator. Furthermore, under international law and Mexico’s newly passed Victims’ Law, the government has an obligation to provide victims of crimes with an effective remedy—including justice, truth, and adequate reparations.

Investigative Failures

Our research shows that authorities routinely fail to respond in a timely fashion when victims, their families, or witnesses report abductions while they are taking place. And when victims’ relatives or others report disappearances, prosecutors and law enforcement officials rarely take immediate action to search for the victim or the perpetrators. In spite of requests by families, they do not trace victims’ cell phones, track their bank transactions, obtain security camera footage (which is often automatically deleted at regular intervals), or take other time-sensitive actions. Instead, prosecutors and law enforcement officials regularly misinform families that the law requires a person to have been missing for several days before a formal complaint can be filed, and advise them to search for missing people at police stations and military bases—placing the family at risk; or prosecutors preemptively assert they lack the legal jurisdiction to investigate the case. These groundless delays and omissions result in irreparable losses of information that could potentially have saved the lives of victims and helped locate the people who abducted them.

Making matters worse, when prosecutors, judicial police, and law enforcement officials attend to families of the disappeared, they regularly tell them the victims were likely targeted because they were involved in illicit activities, even when there is no evidence for such assertions. Authorities use this unfounded presumption as a pretext for not opening investigations, and alienate and harass individuals whose cooperation often could have played a critical role in finding the missing person. While it is reasonable for authorities to investigate the background of a victim as a possible lead, Human Rights Watch found that officials repeatedly assumed the criminal guilt of victims before conducting any preliminary investigation, and held onto such views in the face of clear evidence to the contrary.

If and when prosecutors open investigations, they regularly ask victims’ families to take investigative steps, such as interviewing witnesses and tracking down suspects, which should be carried out by officials. It is appropriate and indeed necessary for prosecutors to collaborate with victims’ relatives in investigating disappearances. Yet in case after case, Human Rights Watch found that they relied disproportionately, or even entirely, on families to carry out key investigative tasks. In a vicious cycle, families take on more of the authorities’ duties because they know that investigators will not investigate on their own. And rather than fulfilling their investigative responsibilities, prosecutors and law enforcement officials become more accustomed to passing them off to victims’ relatives. Not only are families not trained for such tasks, but carrying them out can also put them at considerable risk: in several cases, families’ investigative efforts— encouraged by prosecutors—resulted in their being victims of threats and attacks.

In addition to relying excessively on families, prosecutors fail to carry out basic investigative steps. Among the most common lapses documented by Human Rights Watch were: failing to interview the victims’ family members, witnesses, or others who could have provided relevant leads; failing to interview possible suspects; failing to pursue obvious lines of investigation, such as obtaining the names of police officers and soldiers assigned to units implicated in disappearances; and failing to visit the scene of the crime to collect evidence. Even in cases where justice officials carried out basic investigative steps, they often waited so long to complete them that possible leads dissipated.

Prosecutors and law enforcement officers also misplaced key evidence, such as DNA samples of victims’ relatives, and made errors in compiling information critical to the case, such as recording inaccurate details about when or where victims disappeared. In some cases, police and justice officials fabricated evidence—claiming to have carried out interviews that never occurred, for example—while in others they manipulated or destroyed key evidence, suggesting that they may have been working to protect those responsible for the crimes.

Beyond failing to resolve individual cases and exacerbating a general climate of impunity, these investigative failures allow security forces and criminal groups that carry out multiple disappearances to strike again. In several cases, Human Rights Watch found compelling evidence that the same state agents—often in collaboration with criminal groups—carried out multiple disappearances in separate incidents. In these cases, prosecutors and law enforcement officials neglected to pursue evidence that, had it been adequately investigated, may have prevented additional people from being disappeared.

Impact on Victims’ Families

Disappearances have a profound impact on virtually every aspect of the lives of victims’ families. Families described not knowing what happened to their loved ones as a source of perpetual anguish—one deepened by the lackluster efforts of prosecutors to find their relatives. Many described an overriding sense of obligation to set aside the other parts of their lives in order to dedicate themselves fully to searching for their loved ones. Relatives reported suffering serious emotional and psychological effects as a result of their loss—including depression and the constant fear that another loved one would be taken next. Several relatives of the disappeared in the cases documented here, including at least one child, attempted to commit suicide. Disappearances also take a heavy toll on relationships among victims’ surviving relatives, who cope in different and at times conflicting ways, with disputes sometimes arising over sensitive issues such as whether to keep looking for the missing.

Families who do keep searching for the missing, publicly discuss their cases, or press authorities to investigate often are subject to harassment, threats, and attacks. These hostile acts are often aimed at dissuading relatives from pressing for accountability, and play on relatives’ terror of losing another loved one. Furthermore, such hostile acts terrorize not only the people they target, but also other relatives of the disappeared and members of the public, who fear that calling for justice will put them at risk.

In Mexico, disappearances also have devastating financial consequences for victims’ families, with particularly significant impact on vulnerable groups such as children and families living in poverty. The overwhelming majority of disappeared persons in the cases documented by Human Rights Watch were working class men, who were often the sole wage earners in households with several children. In their absence, their spouses and partners were forced to take immediate measures to adapt to the loss of income and provide for their families. This hardship is aggravated by the system of social services in Mexico, whereby the receipt of some services are conditional upon a member of the household being employed. Therefore, a disappearance can lead to the suspension of access to social benefits such as healthcare and childcare. In order to maintain access to these crucial services, relatives were forced to initiate a costly and protracted bureaucratic process to obtain recognition that the disappeared person was missing or dead, which heightened their suffering.

The Special Prosecutor’s Office for Attention to Victims of Crimes (PROVÍCTIMA) was set up in 2011 to assist the families of victims emotionally, economically, and legally, with a special focus on helping the families of the disappeared. Most of the families interviewed by Human Rights Watch had never come into contact with the agency, and had little to no understanding of the services it offered. Meanwhile, more than 30 families of victims who had sought assistance from PROVÍCTIMA told Human Rights Watch that the agency failed to deliver on commitments it had made—such as providing medical aid for relatives’ operations. Furthermore, the overwhelming majority of these families said PROVÍCTIMA pressured relatives to accept that their loved ones were dead, even though no evidence had been uncovered to substantiate that conclusion, exacerbating their suffering.

A New Approach: the Example of Nuevo León

Nuevo León has been one of the states hardest hit by disappearances in recent years, with estimates ranging from over 600 (by official estimates) to more than 1,000 people disappeared (according to local human rights defenders) since the beginning of the Calderón administration. In 2010 and 2011, Human Rights Watch carried out several fact-finding visits to Nuevo León to investigate enforced disappearances and other abuses, and observed a climate of near-total impunity similar to what we had found in several other states of Mexico. Despite clear evidence of enforced disappearances, state prosecutors consistently failed to prosecute the members of the military and police who had committed them. Victims and their families grew deeply disillusioned with authorities, while even well-intentioned prosecutors had little incentive to investigate these crimes. In a vicious cycle of distrust and dysfunction, the less that victims and officials collaborated in solving these crimes, the more entrenched the climate of impunity became.

Then came the shift. Catalyzed by a grassroots victims’ movement and partnered with a local human rights group, families of the disappeared collectively demanded that authorities begin to take the investigations seriously. Under considerable pressure, state officials agreed to work with the families in investigating their cases. At first, both sides were distrustful. However, when prosecutors—motivated by families to investigate and held accountable when they did not—began to genuinely look into the crimes, they gradually began to win back the trust of the victims’ relatives. And families, in turn, began to collaborate more openly with prosecutors. The combination of real efforts by prosecutors and the guiding hand of families gave rise to a new dynamic, which allowed investigations to move forward for the first time in years.

Progress in individual investigations, however small, made it possible to believe that these horrific crimes, many of which appeared to implicate state agents, could be solved. A virtuous cycle started to take the place of a vicious one: the more prosecutors investigated, the more they earned the trust of victims’ families, and the more investigations advanced. For their part, prosecutors took the solid investigative tactics and skills they had learned working on one case or another and applied them to other disappearances on their docket. Over fifty suspects have been charged in seven of the cases tackled through the “working meetings” with families and human rights defenders. Even in those cases in which suspects have not been charged, the investigations have progressed, as prosecutors have pursued long-neglected steps—such as summoning suspects for questioning, canvassing for witnesses, and pressing telephone companies to hand over victims’ cell phone records—with a renewed sense of urgency and purpose.

This qualitative work on individual cases has been coupled with broader institutional and legal reforms aimed at strengthening the capacity of authorities to prosecute these crimes, such as passing legislation that criminalizes enforced disappearances, assigning special judicial police to investigate disappearances, and drafting an investigation manual that lays out fundamental steps that every prosecutor should take when investigating a disappearance.

For all of the progress that has been made in investigating disappearances in Nuevo León, the challenges that remain to effectively investigating disappearances and finding those who have gone missing are daunting. Authorities whose input is critical to advancing investigations often fail to cooperate with the efforts of prosecutors to solve cases—or worse, intentionally obstruct them. Some families, frustrated with the limited progress in their investigations, and understandably skeptical of authorities’ commitment given their previous experiences, have lost faith in the process and stopped cooperating with prosecutors. And state prosecutors have been alarmingly slow to apply the solid investigative practices developed in the “working meetings” to the hundreds of other disappearances that are not directly monitored by families and human rights defenders, in some cases repeating the same chronic investigative errors and omissions in new cases.

Due to these and other serious obstacles, advances in the investigations have been limited. The fate of the overwhelming majority of the disappeared remains unknown. And despite having charged more than 50 suspects in investigations tied to the “working meetings,” prosecutors have yet to obtain a conviction. Nevertheless, the step of breaking through a climate of disillusionment and distrust in select cases is real. In that way, the working process in Nuevo León provides a blueprint for how some of the greatest challenges to investigating not only disappearances, but all human rights violations in Mexico, can be overcome.

Recommendations

To the Federal Executive Branch:

- Present a proposal to Congress to reform the military justice system to ensure that all alleged human rights violations, including enforced disappearances, committed by members of the military against civilians are investigated and prosecuted in the civilian justice system.

- Sign an executive order mandating that all detainees be immediately presented before the public prosecutor’s office and that under no circumstances should detainees be taken to military installations, police stations, or illegal detention facilities for interrogation by members of the military or police.

- Work with federal agencies such as the Institute of Social Security to develop special, expedited processes to ensure that families of the disappeared do not lose access to basic social services as a result of disappearances.

- Request that the Senate recognize the jurisdiction of the Committee on Enforced Disappearances to receive complaints of enforced disappearances submitted by individuals and states (pursuant to articles 31 and 32 of the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance).

- Issue an invitation for the Committee on Enforced Disappearances to conduct a fact-finding visit to Mexico.

- Establish a national database of the disappeared that includes key information to help identify missing persons, such as genetic information (DNA) from relatives of the victim, evidence of the participation of state actors, and investigations that have been opened into the case. The criteria for and collection of such data should be standardized across prosecutors’ offices, human rights commissions, morgues, and other relevant institutions to ensure the utility of the system.

- Establish a national database of unidentified human remains, including genetic information (DNA) and other distinguishing characteristics. The criteria for and collection of data should be consistent with the data collected for the database of the disappeared.

- Conduct a thorough comparison between the national database of the disappeared and the national database of unidentified human remains to search for matches between disappeared persons and unidentified remains.

To Federal and State Prosecutors:

- Conduct immediate, full investigations into all alleged cases of disappearances, including those documented in this report, with a view to prosecuting all parties responsible for the crime under national and international law.

- Abstain from transferring from civilian to military jurisdiction cases in which a member of the military is accused of being involved in an enforced disappearance or any other human rights violation.

- End the practice of requiring victims’ families to gather evidence relating to the disappearance of relatives, such as evidence of the possible participation of security forces.

- Train teams of experts in the exhumation and identification of remains so that experts can be deployed quickly when mass graves and other unidentified bodies are discovered.

- Develop a national protocol in conjunction with law enforcement officials for promptly and thoroughly searching for persons who have been reported as disappeared. Such efforts should be initiated without delay, and should involve the full range of security forces and other authorities.

To Federal and State Legislators:

- Amend or insert the definition of enforced disappearance in federal and state criminal codes to ensure that it is consistent across jurisdictions and includes all conduct included in the definitions established by the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance and the Inter-American Convention on Forced Disappearance of Persons. In particular, ensure that the definition includes disappearances committed by organized groups or private individuals acting on behalf of, or with the support (direct or indirect), consent, or acquiescence of state officials.

- Reform the Military Code of Justice to ensure that all alleged human rights violations, including enforced disappearances, committed by members of the military against civilians are investigated and prosecuted in the civilian justice system.

- Modify the definition and the process by which a person is formally declared “absent” (declaración de ausencia) in the Federal Civil Code to prevent the loss of basic social services by families of disappeared persons.

- Modify vague “flagrancy” laws currently used to justify arbitrary arrests and unjustified preventive detention. These laws should be applicable only in exceptional cases when a suspect is caught in the act of committing a crime.

- Recognize the jurisdiction of the Committee on Enforced Disappearances to receive complaints of enforced disappearances submitted by individuals and states.

Methodology

This report is based on in-depth research on disappearances in Mexico conducted between January 2012 and February 2013, including fact-finding investigations in the states of Coahuila, Guanajuato, Nuevo León, San Luis Potosí, and Zacatecas. In the course of these investigations, researchers also met with families whose relatives had disappeared in other states, such as Tamaulipas and Michoacán. The report also draws upon Human Rights Watch’s research on disappearances for the November 2011 report, Neither Rights Nor Security, which documented cases in Baja California, Chihuahua, Guerrero, and Nuevo León. In all, the disappearances detailed in this report took place in 11 states, representing a geographically and politically diverse cross-section of the country.

This report will use “enforced disappearance” and “disappearance” as distinct terms. The term “enforced disappearance,” following the definition set out by treaties such as the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance, will be applied to cases in which there is compelling evidence of three cumulative elements:

- The deprivation of liberty against the will of the person concerned;

- The involvement of state agents, either directly or indirectly through authorization, support, or acquiescence; and

- The refusal to disclose the fate and whereabouts of the person concerned.[1]

The term “disappearance,” by contrast, will be applied to cases in which there is only evidence of two of the three aforementioned elements: the taking of a person against his or her will, and the failure to disclose his or her fate and whereabouts. The distinction, therefore, is that in a “disappearance” there is not compelling evidence of the involvement of stage agents.

Human Rights Watch documented 249 disappearances committed during the Calderón administration for this report. In 149 of those cases, the evidence strongly suggests they were enforced disappearances—meaning state actors likely participated in the crime. To reach this determination, we relied on a range of official documents such as arrest reports, detention registers, complaints filed by victims’ relatives, witness testimony, investigation case files, press releases by officials, amparos,[2] and reports by government rights commissions.[3] These documents were supplemented by additional sources of evidence which pointed to the participation of state agents in specific cases—much of it gathered by victims’ families, local human rights defenders, and journalists—including: security camera surveillance videos, witness video footage, audio recordings by victims’ families of meetings with officials, photographs of abductions, and maps of the signals emitted by victims’ cell phones or radios. In the remaining 100 of the 249 cases, there was not sufficient evidence to conclude that state actors had participated in the crimes, though they may have.

In certain cases in this report, Human Rights Watch cites official confessions by individuals accused of having participated in enforced disappearances. It is relevant to note that our previous report, Neither Rights Nor Security, documented the systematic use of torture by security forces in five states during the administration of President Felipe Calderón. Oftentimes, these tactics were aimed at extracting forced confessions that not only accepted guilt, but also a posteriori concealed the abuses by security forces leading up to and during coercive interrogations. Given the prevalence of this practice, and the doubt it casts on the truthfulness of confessions obtained by officials, this report only cites confessions of alleged involvement in crimes when such statements are corroborated by and consistent with other credible evidence—such as witness accounts, video footage, or official arrest reports. And each time the report cites such confessions, Human Rights Watch has noted that the widespread use of torture should be taken into account when weighing their evidentiary value.

The report also notes when individuals have been charged in disappearance cases. While being charged with a crime (consignado under Mexican law) requires the authorization of a judge, it is not—nor should it be read as—an indication of guilt.

In the course of the research, Human Rights Watch conducted more than 100 interviews with a wide array of actors. These included attorneys general, prosecutors, law enforcement chiefs, police officers, legislators, national and state human rights officials, victims’ relatives, human rights defenders, and journalists, among others, as well as a range of federal officials. We also drew on official statistics, which we sought through interviews, emails, and public information requests submitted through Mexico’s Federal Institute for Access to Public Information (Instituto Federal de Acceso a la Información y Protección de Datos).

In some of the interviews conducted by Human Rights Watch, victims’ families, friends, and witnesses requested that their names—as well as those of the disappeared—be withheld to protect their identities. Often this request was motivated by the fear that speaking publicly about the case could bring harm to the disappeared person, or even lead to another person being disappeared as retribution for denouncing the crimes of criminal groups or authorities. Others asked that the cases they shared not be included in the report, driven by similar concerns. Several state officials who spoke with Human Rights Watch about disappearances asked that their names be withheld, but permitted us to include the government institutions for which they worked.

Translations from the original

Spanish to English are by Human Rights Watch.

Enforced Disappearances

There is strong evidence that 149 of the 249 abductions Human Rights Watch investigated for this report were enforced disappearances involving public security personnel. Members of all of the security forces participating in public security operations—federal, state, and municipal police, the Army, and the Navy, as well as judicial police—are implicated in the cases. Members of municipal police forces, who in many instances colluded with organized crime, are implicated in more cases than members of other forces.

In the 149 cases, the victims were virtually always seen by eyewitnesses being taken into custody, most often without evident justification, by police or the military. These illegal detentions were virtually never officially registered, nor were detainees handed over to the public prosecutor’s office, as the law requires. The failure to register detentions and promptly hand detainees over to prosecutors has obstructed efforts of families and authorities to search for the missing people. In cases where security forces appeared to act on their own, victims were never seen after their illegal arrests. In other cases, there is evidence that members of the police or military handed over people to criminal groups after illegally detaining them, or joined armed men in carrying out abductions, and then denied participating in the crime. Sometimes the collaboration between authorities came after people were abducted—when state agents helped criminal groups extort the families of the victims.

Human Rights Watch collected a wide range of evidence that ties officials to these 149 cases. In many instances, officials explicitly identified themselves to families and witnesses as police or soldiers when they were carrying out the arbitrary detentions that led to disappearances. Members of security forces often wore uniforms and drove official vehicles used in abductions, and in several cases were captured on video or in photographs. In many instances, the testimonies of family members were confirmed by independent witnesses. Indeed, in several cases, security forces admitted to having taken the individuals in question into custody.

Government officials have at times said that crimes allegedly committed by soldiers or police in uniform were likely carried out by people disguised as members of security forces. While it is true that on a few occasions in recent years criminal groups have employed counterfeit uniforms and vehicles, government officials interviewed for this report were unable to identify a single case in which there was any evidence that criminals had posed as members of a security force to carry out a disappearance. The dearth of examples, coupled with the fact that, as this report shows, criminal groups openly carry out disappearances with near total impunity, casts serious doubt on whether any of the cases documented here were carried out by individuals using counterfeit uniforms and vehicles.

In the 149 cases in which evidence strongly suggests that enforced disappearances were perpetrated by state agents, the facts point to a clear modus operandi on the part of security forces. In some instances, there is evidence that a specific security force carried out multiple disappearances in a limited period of time within the same geographical area, suggesting that some of these crimes may have been planned and coordinated, or at the very least could not have taken place without the knowledge of high-ranking authorities.

Enforced Disappearances by the Navy

Human Rights Watch documented more than 20 cases of enforced disappearances perpetrated by members of the Navy in June and July 2011. The concentration of the cases within a short time period, the similar tactics described by victims’ families and other witnesses, corroborated by photographic and video evidence, and the fact that the abductions were spread across three northern states strongly suggests that these were not isolated cases, but rather points to a clear modus operandi by the Navy. Given the number of members of the Navy that allegedly participated in these operations—at least a dozen official vehicles, according to witness accounts—and the fact that the Navy acknowledged that it detained several of the victims, it is unlikely that such operations took place without the knowledge of ranking officers.

Victims’ families and witnesses described near identical tactics in the raids. In each case, the Navy arrived in a large convoy of more than a dozen vehicles, the majority of which were marked with official insignia, along with two to four unmarked vehicles. They closed off entire streets, using vehicles as barricades. Heavily armed members of the Navy wearing masks then entered homes, often forcibly, without any search or arrest warrants. According to families, the people in Navy uniforms were not looking for individuals by name. Instead, they indiscriminately took young men, telling their families they were being brought in for questioning and would be released if they proved to be innocent.

José Fortino Martínez Martínez, 33, who ran a convenience store in a school with his wife in Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas, was sleeping at home with his wife and four children (ages 16, 12, 7, and 3) on June 5, 2011, when they awoke at 1 a.m. to the sound of their front gate being broken open. Martínez’s wife, Oralia Guadalupe Villaseñor Vázquez, told Human Rights Watch she turned on the light to discover seven or eight masked men entering their bedroom.[4] The men were armed with large weapons and wearing bulletproof vests that said “Marina” (“Navy” in Spanish). After the men had searched all of the rooms, one of them approached a man who appeared to be a commanding officer and said, “It is just family.”[5]The officer apologized to Martínez’s wife for breaking down the door of their home. He handed her 200 pesos to cover the damage and said, “They complained that there was something going on here, so that is why we entered like that.”[6]The officer did not specify who had complained.

The members of the Navy then took Martínez outside for questioning. From the entryway, his wife said she counted 14 vehicles marked with Navy insignia—most of them pick-up trucks, several of which had mounted guns in their bays—and four unmarked cars.[7] After several minutes of questioning, the members of the Navy let Martínez go back inside his home. But minutes later they summoned him outside again, saying they needed to check his fingerprints. His wife was told to wait inside the home with their children. Approximately half an hour later, his wife heard the screech of tires. When she went outside, she said, the vehicles in the convoy were driving away. Several neighbors who had gathered outside told Martínez’s wife that they had seen the Navy put him into the back of a car before driving off.

Martínez’s wife immediately got in her car and began driving around Nuevo Laredo in search of the convoy, methodically checking each of the major roadways. She came across the convoy on a highway near the airport, she said, and followed them from a distance as they carried out raids on several other homes. At one of the raids, Martínez’s wife approached an armed, masked man in a vest that said “Navy” (“Marina”). She asked why they had detained her husband and where they were taking him. The man answered that they had not detained anyone.

Martínez’s wife said she saw four men handcuffed in the bay of one of the pick-ups.[8] One had a bag pulled over his head, one was blindfolded, and the other two had their shirts pulled over their heads. As she looked at the detainees, the man she was speaking to warned her to stop following the convoy. If she did not, he warned her, they would shoot at her vehicle. He said they had been authorized to fire their weapons at will, regardless of whether their targets were women and children.[9] She returned to her car.

In spite of the threat, Martínez’s wife told Human Rights Watch she continued to follow the convoy until it arrived at the Motel Santa Monica in downtown Nuevo Laredo. As news spread that the detainees were being held there, more than a dozen friends and relatives of people who had been taken assembled outside of the motel, together with members of the local press. The people gathered near the entrance to the parking lot of the hotel, which was surrounded by a wall. Martínez’s wife, his children, and others waited there for approximately two hours.[10]

The presence of Martínez’s wife and other witnesses outside of the hotel was captured by video footage and photographs from that night provided to Human Rights Watch.[11] The video shows at least four Navy pick-up trucks in the motel parking lot, identifiable by official insignia on their doors.[12] It also shows several dozen armed men, wearing masks and uniforms bearing the name “Navy,” walking back and forth outside the motel. A pick-up truck with the Navy insignia on its door, marked as unit number 600160, is shown in the video at the parking lot entrance.[13] The truck was directed outwards, towards the street where people had gathered.[14] Several photographs show a masked man in a Navy uniform standing in the truck’s cargo bay, manning a mounted gun.[15] At one point, the photographs show, another masked man in a Navy uniform walked into the street next to the motel and began to photograph members of the crowd who had gathered there.[16]

One of Martínez’s sons, age 16, who was also outside the motel, told his mother that he spotted his father through one of the windows of a room on the motel’s second floor.[17] After his father walked by the window, the son said, the curtain was drawn closed swiftly by a man in a Navy uniform. At approximately 6 a.m., after several hours of waiting there, the convoy left the hotel. From videos and pictures taken by victims’ family members as the convoy left the hotel, Human Rights Watch was able to identify the Navy insignia and unit numbers on five of the pick-up trucks, as well as the license plates of several of the non-official vehicles.[18]

Martínez’s wife continued to follow the convoy after it left the motel. She said she observed the vehicles as they stopped outside a location in the Mirador neighborhood of Nuevo Laredo.[19] She said Navy vehicles blocked off two ends of a residential block, just as they had done on her block when they took her husband.

Human Rights Watch separately interviewed the mother of Martín Rico García, 41, who said her son was arbitrarily detained by people in Navy uniforms on the morning of June 5, 2011, also in Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas. Rico García’s mother confirmed that the street where Martínez’s wife observed members of the Navy carrying out another raid that morning was her street, lending credibility to both accounts.[20] She also confirmed the raid had occurred at approximately 6 a.m.

Martín Rico García’s family described similar tactics in his arbitrary detention. His mother said armed, masked men in Navy uniforms had come to her door and demanded she open it.[21] When she did, they identified themselves as members of the Navy and said they were carrying out an investigation. She asked if they had a warrant to search the home, but they said they did not need one. They searched the house and detained her son and her grandson. She said that the members of the Navy asked her how old her grandson was.[22]When she told them he was 17, the men let him go. They told Rico García’s mother they were taking her son to their base, leaving her with no record of the detention.

According to Martínez’s wife, after men in Navy uniforms stopped at Rico García’s home, they proceeded to a gas station, where she was able to approach a man in a Navy uniform to ask what would happen to her husband.[23] The man responded, “He will be investigated. If there is nothing on him, he will be set free.” When she told him that her husband had done nothing wrong, he responded, “Many say that they weren’t up to anything. But these guys behave one way at home and another in the streets. They are not all little white doves.” Then, the man warned her that she would be shot if she continued to follow the convoy. Afraid for her children, she stayed in the gas station when the convoy departed. She never saw her husband again.

The Navy provided conflicting accounts as to whether it had any contact with Martínez, Rico García, and at least four other men who were arbitrarily detained on June 4 and 5, 2011. After several press reports that the Navy had arbitrarily detained the men, the Navy issued a press release on June 14 claiming that “[w]ith respect to various news stories disseminated in assorted print media and websites, [the institution] categorically denies that Navy personnel participated in said operations.”[24]Approximately two weeks later, the Navy contradicted its initial assertion in a second press release, stating:

Acting on intelligence that suggested the presence of members of organized crime in various homes in Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas, upon inspecting these locations on [June 5], the Navy acknowledges that it had contact with six of the people supposedly detained, of the names José Fortino Martínez, José Cruz Díaz Camarillo, Héctor Rodríguez Vázquez, Martín Rico García, Diego Omar Guillén Martínez and Usiel Gómez Rivera. Up to the present there is no evidence that suggests that Navy personal secured, much less unlawfully deprived these persons of their liberty. Also, it should be pointed out no evidence has been found establishing that these individuals belonged to any criminal cell.[25]

The press release suggested that the six men may have been detained by organized crime after coming into contact with Navy personnel on the same day, “presumably with the aim of fueling allegations that detract from security operations designed to guarantee the safety of the public.”[26] In other words, the Navy implied that the victims may have been disappeared by criminal groups, who wanted to make it appear as though the crimes were committed by the Navy in order to hurt the reputation of the institution.

The Navy changed its narrative of the events a third time in a November 2011 account provided to the federal prosecutor’s office. In it, the Navy said that it had indeed come into contact with the six missing men in Colombia, Nuevo León—a different location from the one it identified in a previous press release.[27]The account also claimed that the six missing men had told the Navy that “they had been forced, under threat, to work for the Zetas criminal group, as a result of which [the six victims] were asked to cooperate [with the Navy] to provide information on the matter; the individuals were offered protection during the duration of Navy forces in that location. Then they were transferred to the town of Miguel Alemán, Tamaulipas, for their safety.”[28]

Among the many contradictions between this and earlier accounts is the fact that, while the Navy’s previous account alleged that the victims had no connection to any organized crime group,[29] the latter account said the victims had been forced to work for the Zetas. It is also unclear why the Navy would allegedly transport the six men to the bus station in Miguel Alemán, Tamaulipas, “for their safety.” None of the victims lived in Miguel Alemán.[30]Moreover, it is a city notorious for being one of the most violent in the state (for example, there were several public shootouts involving the military and armed criminal groups shortly before this incident), and for having a significant presence of organized crime groups, in particular the Zetas.[31]

Human Rights Watch interviewed relatives of two other men who were arbitrarily detained on the same night as Martínez; these relatives corroborated the chronology of detentions, and described similar tactics. Yadira Alejandra Martínez Ramírez, 23, for example, said her husband, Diego Omar Guillén Martínez, 24, was detained late on the night of June 4, 2011, by eight armed, masked men in Navy uniforms who forced their way into his parents’ house and took him without explanation. [32] None of the six men have been seen since that night.

The disappearances carried out on June 4 and 5, 2011, in Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas, are similar in important respects to several other disappearances carried out in the neighboring states of Nuevo León and Coahuila during the same month. In those cases, robust evidence from multiple sources also points to the involvement of the Navy, suggesting all of these disappearances may have been part of a regional operation. For example, on June 23, 2011, at approximately 4 p.m., Jesús Víctor Llano Muñoz, 22, a taxi driver in Sabinas Hidalgo, Nuevo León, was stopped at a Navy checkpoint that had been set up outside of a hotel where the taxi company’s dispatch station is located.[33] His father, also a taxi driver, was at the station at the time. When he saw the Navy personnel remove his son from his taxi and load him into a Navy pick-up truck, he approached and asked why they were detaining his son. An official responded, “If he’s not involved in anything, I’ll hand him over to you shortly.” [34] Minutes later, the truck in which his son was being held drove off in a convoy of approximately 20 vehicles. His family filed complaints with the state prosecutor’s office in Sabinas Hidalgo that day, which said it had no information about his case.[35] They also inquired at the Navy base, which said they were not holding him. Llano’s whereabouts remain unknown, and no members of the Navy have been charged in the case.

Less than a week later—on June 28—René Azael Jasso Maldonado, 26, another taxi driver, was arbitrarily detained in the middle of the night at his family’s home in Sabinas Hidalgo, Nuevo León.[36] According to his mother, father, and brother—all of whom were home at the time—10 armed, masked men carried out the raid wearing Navy uniforms. The armed men entered the home without a warrant and first grabbed René’s brother, Oziel Antonio Jasso Maldonado, holding him facedown at gunpoint and yelling, “You are an halcón!”—the name for people who work as lookouts for criminal groups—before another man in Navy uniform entered and said Oziel was not the person they were looking for. They then took René, who was in the next room, and loaded him into an official Navy vehicle.[37] It was the last time they saw him.

Enforced Disappearances by Local Police

The security force most frequently implicated in the enforced disappearances documented by Human Rights Watch is local police. Human Rights Watch found strong evidence in 95 cases that local police participated directly or indirectly in enforced disappearances.[38]

For example, Israel Torres Lazarín, 21, worked at a treatment center for drug addicts in Gómez Palacios, Durango. On June 18, 2009, Torres was traveling together with five of his co-workers to pick up a patient when their car was stopped by municipal police in Matamoros, Coahuila.[39] Torres communicated via radio with the director of the treatment center to notify him that the group had been stopped outside of a Soriana department store (a chain in Mexico) by police, who informed them that it was a “routine check.”[40] The director later told Torres’s mother that when he radioed back to Torres three minutes later, the police were confiscating the detainees’ radio and cellphones. When the director tried communicating by radio a third time, there was no answer. The director immediately traveled to the location and spoke to several people working nearby who said they had seen the police stop the car and place six individuals in a truck marked with the insignia of the municipal police.[41] Torres and his five co-workers were never seen again.

In another case, gold dealers Eduardo Cortés Cortés, 27, José Manuel Cortés Cortés, 21, Carlos Magallón Magallón, 30, and David Magallón Magallón, 28, were abducted after traveling from their homes in the town of Pajacuarán, Michoacan, to buy and sell gold in the state of San Luis Potosí, as they did routinely as part of their trade, according to the father of victims Eduardo and José Manual Cortés Cortés.[42] On the night of September 29, 2009, they arrived in Río Verde, San Luis Potosí, where they checked into a hotel and called their families, according to a preliminary investigation report by the San Luis Potosí state prosecutor’s office.[43]

At 12:45 p.m. on September 30, David Magallón sent a text message to his wife saying that they had been stopped by police in the town of Cardenas, San Luis Potosí. “The police stopped us again anything happens we are in Cardenas San Luis Potosí,” the message read.[44] Shortly thereafter David called his wife and told her that he and the others had been detained and were being taken to the police station in Cardenas.[45] Then the call cut out abruptly. When his wife called back, she was unable to reach him.[46] It was the last contact any of the families had with the four men.

Further evidence points to the involvement of the police in the disappearance. Another gold dealer from Pajacuarán—who was working in Cardenas with his business partner at the time the four men disappeared—told the victims’ families he had seen the victims being questioned by police on September 30. [47] He also said that he and his partner had been robbed by local police the same day the men were “disappeared.” The police officers warned him that they did not like people from Michoacán and told him not to come back, he said. Although the victims’ relatives provided this information to investigators in San Luis Potosí on November 17, 2009, officials made no efforts to track down the alleged witnesses, according to the families. [48] When Human Rights Watch reviewed the investigation case file, there was no record of prosecutors having interviewed—or attempted to find—this potential key witness. Police in Cardenas denied ever having questioned the four men, and no officials have been charged in the case. [49] In October 2011, the head of public security in Cardenas, two police officers, and the chief of a police unit were detained and charged with having worked with the Zetas to carry out robberies, acts of extortion, and kidnappings. [50] Family members of the victims recognized one of the people charged as the police officer who had threatened them when they had traveled to Cardenas in October seeking information on their missing relatives. [51] They reported this to the public prosecutor’s office, but at the time of writing, no officers had been charged in the crime. [52]

Enforced Disappearances by Federal Police

Human Rights Watch found strong evidence that 13 enforced disappearances were carried out by federal police, including that of teenagers Roberto Iván Hernández García and Yudith Yesenia Rueda García, both 17.[53] Hernández and Rueda, boyfriend and girlfriend, were at the home of Rueda’s grandmother on March 11, 2011, in Monterrey, Nuevo León, when at approximately 9 p.m. armed men in masks broke down the door.[54] The eight men were wearing uniforms that said “Federal Police,” according to Rueda’s grandmother and aunt, who were both home at the time, and said they were looking for someone nicknamed “Piña.” When the family said there was no one by that name in the house, the men in police uniforms brought a detainee in handcuffs into the home and walked him over to Hernández and Rueda.[55] One of the uniformed men gestured to Hernández and asked the detainee: “Is it him?” “No,” the man answered. Then one uniformed man said to another, “Well, if you want to, take them.” With that, the officers removed Hernández and Rueda with force from the house—beating Hernández as they went and pulling Rueda by her hair—and loaded them into cars waiting outside.[56] According to Rueda’s grandmother and aunt, there were two pick-up trucks and a third vehicle marked with Federal Police insignia waiting outside, as well as a taxi and an unmarked car. None of the cars had license plates, they said. Rueda’s grandmother said she saw other detainees in the federal police cars.[57]

Within an hour of their arbitrary detention, relatives of Hernández and Rueda went to the federal police station in Monterrey to inquire whether the two were being held there.[58] The police officers who attended to them said, “We don’t know anything about it. Detainees are not brought here. Go to the municipal police.”

Complicity between Security Forces and Organized Crime in Disappearances

In more than 60 cases, Human Rights Watch found compelling evidence of cooperation between security forces and organized crime in disappearances. For example, 19 men[59]who worked for a construction company were abducted in Pesquería, Nuevo León, on May 28, 2011.[60] A neighbor who lived across the street from the small apartment building where the workers were staying while they completed the project saw municipal police arrive at the building immediately before the men were abducted, she told the victims’ relatives.[61] Later, police cars returned to the building carrying several of the workers, the witness said, and the workers loaded valuables from the dormitories into the police cars. Witnesses also reported seeing a large group of workers being held outside of the municipal police station in Pesquería on May 28.[62]

That afternoon, the kidnappers contacted the construction company’s foreman, Julio Rodríguez Torres, who had been staying in a different hotel in Pesquería and was not with the workers when they were abducted. The kidnappers told Rodríguez that if he wanted to negotiate the release of his workers, he would need to meet them the following morning at a bridge on the outskirts of town. An employee who drove him to the location said that a municipal police car and a car without license plates were waiting for him there.[63] Rodríguez got into one of the cars, which then drove away. Neither he nor the 19 workers were ever seen again.

Seventeen police from Pesquería were arrested on June 9, 2011, and placed under arraigo detention[64] the following week for the abduction of the workers and collusion with organized crime. At this writing, nine police officers had been charged in the disappearance, while the investigation remained ongoing.[65]

In another example of collusion between authorities and organized crime, on December 27, 2011, brothers José Carlos and Juan Rogelio Macías Herrera, 39 and 37—who ran a business selling used cars—were driving between the municipalities of Apodaca and Juárez in Nuevo León when they were detained at a police checkpoint.[66] The wife of one of the brothers lived along the road where police had set up the checkpoint. At 4:30 p.m., she said, she saw the two men being driven in the back of a Juárez municipal police car, which was being followed by another police car.[67] She saw the numbers of the two patrol units and wrote them down. When the brothers did not return home within several hours, relatives went to the Juárez municipal police station to ask if they were being held. The police denied any knowledge of their detention, members of the family said.

On January 3, 2012, five men, including three members of the Juárez police, were detained for kidnapping the two men.[68] In statements given by the police officers to prosecutors, they said they had carried out the detention “under orders” of a local crime boss, and handcuffed the brothers “ to part of the holding pen of the police car, and then we took them to a car lot…where they were held for more time until they were transferred to an unknown place.”[69] Five men were charged with illegal detention with the aim of kidnapping, three of whom were also charged with robbery.[70] According to the statements of the accused police officers, the brothers were handed over to a leader of a local cell of the Zetas.[71] Their whereabouts remain unknown.

Police from Juárez were also implicated in collaborating with organized crime in the disappearances of Israel Arenas Durán, 17, Adrián Nava Cid, and brothers Gabriel and Reynaldo García Álvarez—who worked at a plant nursery in Juárez, Nuevo León. The four young men disappeared on the night of June 17, 2011, after going for drinks at a bar after work.[72] Israel called his younger brother, Irving, from the bar to ask him to bring money for the bill.[73] On the drive there, Irving saw his brother’s car pulled over along the shoulder of the road, with a transit police car behind it. As Irving approached, he saw police loading his brother, in handcuffs, into the back of police car, unit 131. Irving asked one of the officers why the man was being detained, and in response the officer asked if Irving knew the man. When Irving answered that he did not (out of fear), the officer told him to go away.

Irving rushed home and told his parents what he had seen, and then the three set out together for the municipal police station in Juárez. The police who attended to them denied that officers had detained anyone named Israel Arenas. Yet while they waited, Irving saw one of the police officers who had detained his brother walk through the station. He also spotted the police car he had seen his brother loaded into—unit 131—parked outside the station. The following morning, the family returned to the police station but police continued to deny any knowledge of Israel’s detention, and recommended they check other police stations in the area. However, the family spotted Israel’s truck in an impounded car lot next to the station, and owners told the family it had been left there by transit police.

When the family returned to the Juárez transit police station a third time, an official in plainclothes who identified himself as a commander attended to them. He said Israel had been detained for crashing into a police vehicle and was being held in the station. He told Israel’s parents that officers were knocking him around a bit, but that he would be released the following afternoon.[74] Before the family left, according to Irving, the plainclothes officer took him aside and said, “You already know what happens to those who speak too much.”[75] Irving took the warning as a threat not to say that he had seen the police detain his brother.

When the family returned the next day, officials told them that—contrary to the information they had been given the day before—Israel had never been detained. Police also said no one with the characteristics of the man they spoke with the day before worked for the police.[76] On June 24, Israel’s father spotted his son’s truck on the road and followed it to a residential address, which he reported to police. The driver turned out to be a former judicial police officer.

Eight men from León, Guanajuato—José Diego Cordero Anguiano, 47; Juan Diego Cordero Valdivia, 22; Ernesto Cordero Anguiano, 37; Alán Josué Bocanegra García, 19; Sergio Sánchez Pérez, 32; Mario Alberto Reyes, 26; José Javier Martínez, 46; Héctor González Cervantes, 37—were illegally detained on December 6, 2011 by local police in the municipality of Joaquín Amaro, Zacatecas, as they returned from a hunting trip.[77] According to two individuals who were part of the group of hunters and managed to escape their captors, the group was detained at approximately 6 p.m. on December 6, as they drove through Joaquín Amaro. Municipal police officers from Joaquín Amaro and Tabasco (another municipality in Zacatecas) took part in their detention, the survivors said.[78] The police confiscated their mobile phones and weapons and took them to the police station, where they blindfolded them, beat them, and accused them of belonging to a criminal group that had come to take over new territory.[79]

At approximately 11 p.m., the

police handed the hunters over to a group of armed men in six SUVs near a gas

station in Fresnillo, Zacatecas.[80]

(One of the abducted hunters escaped, while another—a teenager—was

released.) The handover of the hunters was captured on the gas station’s

security cameras, footage from which shows police handing the abducted men over

to men waiting in other vehicles.[81]

Zacatecas’s attorney general later said that police officers admitted to

prosecutors to having illegally detained the hunters and handing them over to

“organized crime.”[82]

Eight police officers were charged by state prosecutors on January 18, 2011,

for kidnapping compounded with robbery and ties to organized crime. At this

writing, according to local human rights defenders, the police had also been

charged by federal prosecutors with colluding with organized crime and were

awaiting trial.[83]

Investigative Failures

Failure by Authorities to Intervene During and Immediately Following Abductions

In several cases, victims’ families told Human Rights Watch that they sought help from authorities when someone was taken against their will or immediately afterwards, a period critical to obtaining information on the fate of victim, preventing murder, and finding those responsible. In each case, however, authorities either did not respond or turned them away.

For example, on the afternoon of October 26, 2008, approximately five unmarked SUVs blocked off the street where the Vega family lived, Dania Vega (pseudonym) told Human Rights Watch.[84] Masked men armed with large weapons emerged from the cars and forced their way into the home, abducting Dania’s husband and father, ages 33 and 59 respectively. Vega hid in the bathroom with her children and dialed 066—the telephone number used to report emergencies, such as fires and robberies, to authorities—to report the abduction in progress. She explained what was happening as the armed men went from room to room, going through the family’s belongings. When she finished explaining what was happening, the official on the line told her, “If they are already there, we cannot do anything for you.”[85]

As soon as the armed men had left the home, Vega ran toward the center of Matamoros, which was only a few blocks away, and came across a municipal police car. She told the officers that her husband and father had just been abducted, described the SUVs that had just taken them, and asked the police to pursue the vehicles. The officers responded that they were not responsible for what happened in that part of the town and could not leave the location where they had been posted. She said the officers did not even report the crime to other units over their radios.[86]

The family of Iván Baruch Núñez Mendieta, 31, also found authorities unwilling to act in real time when presented with credible evidence of a disappearance.[87] Núñez went to a bar in Torreón, Coahuila, with several friends on August 6, 2011, and called his wife around 3 a.m. to say he was leaving. When he did not arrive home within several hours, his wife called several of his friends. One told her that the bouncers had prevented Núñez from leaving the bar after he had an argument with a waiter.[88]

When Núñez still had not returned by the morning of August 7, several of his relatives went to the bar, but armed guards at the door would not let them go inside. One of the guards told the family, “If you are looking for the one in the Santos jersey”—a soccer jersey Núñez was wearing the night before—“he will show up in two or three days,” implying that they knew who he was and where he had been taken.[89] This comment, together with the guards’ refusal to let the family enter the bar, led them to suspect he might still be inside. As a result, a relative went to look for help and found a patrol unit several blocks away. But when he told the two police officers what had happened, the officers said that they were assigned to a specific location and could not leave their post.[90] Members of the family said that when they went to the police station, officers told them they would first need to obtain a search warrant before going to the bar, which could take days or even weeks. Núñez was never seen again. In April 2012, his relatives told Human Rights Watch that, according to their conversations with investigators assigned to the case, neither police nor prosecutors had ever inspected the bar.

Failure to Immediately Search for Victims or Open Investigations

Human Rights Watch found that prosecutors routinely fail to conduct preliminary inquiries or open investigations immediately after disappearances are reported, a period that the UN Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances (hereafter the UN Working Group on Enforced Disappearances) defines as “crucial to obtaining information on the fate of enforced disappearance and preventing murder.”[91] Such delays may result in irrecoverable losses of key evidence, and may discourage families from returning at a later time to report disappearances.

Scores of families said that when they went to report a disappearance, prosecutors and police told them that a person needed to have been missing for 72 hours before a complaint could be filed. State prosecutors in Coahuila told Human Rights Watch that, as recently as 2011, official documents had been circulated to state justice and law enforcement officials instructing them to wait 72 hours before opening investigations into disappearances. [92] While they said such memos are no longer in circulation, they conceded that many prosecutors and police continue this practice when families report disappearances.

In other cases, prosecutors told families the missing person had most likely been detained by security forces, and would eventually be handed over to justice officials or released without charge. In the meantime, prosecutors told families, it was not worth opening an investigation. By law, security forces are required to immediately hand over detainees to prosecutors. In addition, prosecutors have a duty to investigate and prosecute security forces that fail to comply with this requirement, which is critical for respecting detainees’ due process rights.[93]

On December 29, 2009, at approximately 8 p.m., according to witnesses, soldiers detained Nitza Paola Alvarado Espinoza, 31, and José Ángel Alvarado Herrera, 30, as they were driving in Buenaventura, Chihuahua.[94] Around 10 p.m., soldiers forcibly entered the home of Nitza Paola and José Ángel’s cousins and arbitrarily detained Irene Rocío Alvarado Reyes, 18, according to Irene Rocío’s mother.[95] On December 30, Nitza’s sister went to the state judicial police in Casas Grandes to inquire about her missing relatives. Upon arriving, she noticed José Ángel’s car parked in a lot attached to the station. When she asked the judicial police officer attending her why the vehicle was there, he said the report accompanying the vehicle indicated that it had been left there by the Army. The same report, the officer told her, said that the Army had detained Nitza Paola and José Ángel, who had been in the car at the time. (A subsequent letter from the judicial police agent assigned to the investigation confirmed that the victims’ car was on the premises of the police station shortly after the disappearance.[96]) Nitza’s sister asked the officer if he was certain the Army had carried out the detentions, to which he replied he was “pretty sure, because I have a section that lists the names of your relatives.”[97]

From the judicial police station, Nitza’s sister went directly to the state prosecutor’s office in Casas Grandes to file a report.[98] However, when she met with a state prosecutor, he refused to register the case, telling her instead that she had to go to the state prosecutor’s office in the neighboring municipality of Buenaventura. When she arrived there, she was told that there was no prosecutor who could attend to her.[99]

José Ángel’s brother encountered similar resistance convincing authorities to open an investigation into the disappearance. Like Nitza’s sister, he also went to the state prosecutor’s office to file a complaint on November 30, where a judicial police agent told him that the three civilians were being held on the 35th infantry battalion in Nuevo Casas Grandes, Chihuahua. However, according to José Ángel, the agent told him the family should wait several days before taking any action.[100] “Be patient,” the officer said, “we know that the Army detained them.” More than two years later, the fate of the three victims remains unknown. A subsequent investigation by the National Human Rights Commission concluded that they had been “disappeared” by the military.[101]

The failure to immediately search for victims and open investigations was also evidenced in authorities’ response to 20 families in Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas, who said their relatives had been arbitrarily detained by members of the Navy on June 4 and 5, 2011. The victims’ families went to the federal prosecutor’s office to report the cases immediately after their relatives were arbitrarily detained.[102] (For a more detailed summary of these cases, see previous chapter, “Enforced Disappearances by the Navy.”) However, federal prosecutors told families they could not register a formal complaint until 72 hours after the victims had gone missing, according to several of the families and a human rights defender who accompanied them to the meetings.[103] Federal prosecutors also refused to accompany families to the neighboring Navy base where many believed their relatives were being held incommunicado.[104] By the time federal prosecutors were willing to attend to the relatives and register their cases on June 7, at least six families who had originally tried to report disappearances did not return to file official complaints.[105] The fact that families did not return suggests that the dilatory measures of the federal prosecutor’s office discouraged victims’ families from filing complaints.

Other prosecutors gave different pretexts for refusing to open investigations or take victims’ testimony. For example, in November 2011, 23 undocumented Central American migrants making their way to the United States were abducted by armed men in Coahuila.[106] According to the testimonies of three migrants who escaped, the armed men stopped a train the victims were riding and then forced the migrants into pick-up trucks. One of the migrants who escaped immediately filed a formal complaint with the federal prosecutor’s office in Saltillo, Coahuila.[107] Weeks later, another of the migrants who had escaped—and who had previously had been too afraid to come forward—decided that he too wanted to file an official complaint. However, when he arrived at the federal prosecutor’s office to give his testimony with a human rights defender, the prosecutor said the defender was not allowed to be present in the meeting.[108] When the defender insisted that he had a right to accompany the migrant, the prosecutor “grew angry that [he] was there and scolded [him].”[109] Then the prosecutor said she no longer wanted to take the migrant’s testimony and turned him and the defender away.[110]

The failure to promptly open investigations into the disappearances of undocumented migrants can be especially harmful when witnesses are fellow migrants, because they are likely to leave the places where abuses have occurred within a short period of time due to their transitory status. They are also more reluctant to speak with authorities, out of fear that authorities will deport them for having entered Mexico without authorization, according to rights defenders in migrant shelters.[111] These investigative shortcomings exacerbate the exposure undocumented migrants already face—people who the UN Working Group on Enforced Disappearances said “are particularly vulnerable to enforced disappearances due to their undocumented status and the lack of financial resources, effective laws, protection schemes, and judicial remedies available to them.”[112]

Blaming the Victim

Prosecutors have an obligation to conduct prompt, thorough, and impartial investigations into every disappearance, which necessitates pursuing various lines of inquiry and exploring a range of motives. Given that cartels have committed serious crimes in Mexico in recent years, including many disappearances, it is reasonable for prosecutors to investigate the possibility that the perpetrators of such crimes are members of criminal groups. It is also reasonable to examine the background of the victim for information relevant to his whereabouts or possible motives for his abduction.