Summary

Since the beginning of anti-government protests in March 2011, Syrian security forces have killed more than 3,100 protesters and bystanders in their violent efforts to stop the protests. They have maimed and injured many more and arbitrarily arrested thousands across the country, subjecting many of them to torture in detention. Local activists have reported more than 105 deaths in custody.

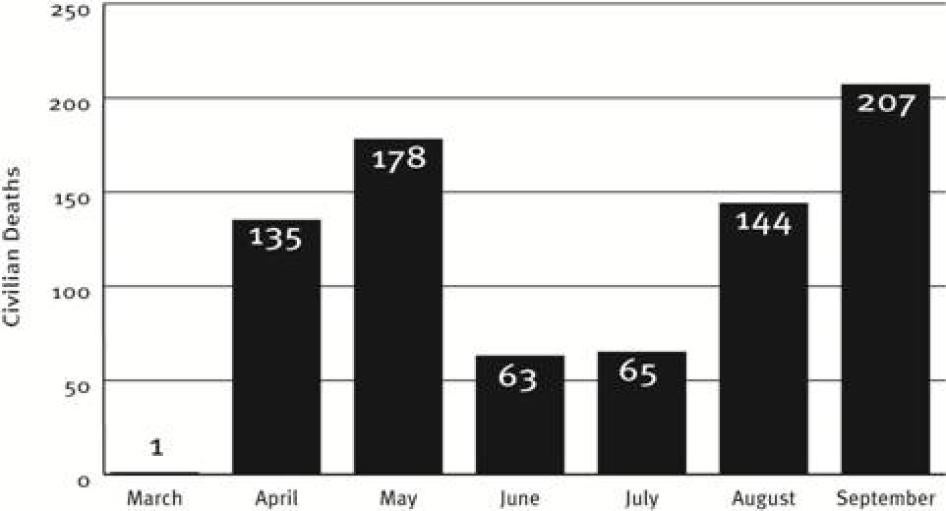

This report focuses on violations by Syrian security forces in the central governorate of Homs from mid-April to end of August 2011, where during that time security forces killed at least 587 civilians, the highest number of casualties for any single governorate, according to lists compiled by local activists. Most of these killings took place in Homs city, the capital of the governorate, and in the towns of Tal Kalakh, Rastan, and Talbiseh. At the time of writing, the crackdown on Homs had intensified with the killing of 207 civilians in the month of September alone, the bloodiest month to date. Human Rights Watch’s June 1 report “We’ve Never Seen Such Horror” documented abuses by Syrian security forces in the Daraa governorate, where the protest movement first erupted.

Obtaining accurate information about events in Syria is challenging as the authorities put enormous efforts into preventing the truth from getting out. This report is based on interviews conducted by Human Rights Watch staff with more than 114 residents of Homs as well as a review of 29 interviews videotaped by Syrian activists. The government has refused Human Rights Watch access to Syria, so we conducted interviews with residents who had escaped to neighboring countries and over the Internet with witnesses inside Syria. Human Rights Watch also reviewed dozens of videos, filmed by witnesses, which corroborate their accounts. Additional information was provided by Syrian activists who have documented the events. To ensure the reliability of the cases reported, this report only includes events corroborated by multiple sources.

Human Rights Watch believes that the nature and scale of abuses committed by the Syrian security forces across the country indicate that crimes against humanity may have been committed. The similarities in the cases of apparent unlawful killings, including evidence of security forces shooting at protestors without warning in repeated instances, arbitrary detention, disappearances, and torture, indicate the existence of a widespread and systematic attack against the civilian population which has the backing of the state.

Despite the high death toll extracted by the Syrian crackdown, the international response to this human rights crisis has been gruelingly slow and ultimately inadequate. While the European Union and United States have taken a number of strong measures – imposing travel bans and asset freezes on Syrian officials and key businessmen close to the authorities, prohibiting the purchase of Syrian oil, freezing the assets of key state and private entities – and while Turkey and some Arab states have strongly condemned Syria’s crackdown, Russia and China have successfully shielded Syria from further criticism or action at the level of the UN Security Council. The expected Russian and Chinese reticence for action has found support in the three influential southern democracies currently members of the Security Council, India, Brazil and South Africa (commonly referred to as IBSA), which have preferred a policy of soft engagement with Syria in the hope that President al-Assad will implement necessary reforms.

The problem with IBSA’s quiet engagement policy is that it has failed in stopping the violent crackdown. After seven months of repeated promises of reforms, security forces continue to shoot protesters, detain political activists, and deny access to independent human rights monitors and journalists. To continue to hope that somehow President al-Assad will enact his reforms without any external pressure is to willfully ignore the record of the Syrian authorities so far. Worse, the inaction and failure of the international community to condemn in unison the violations in Syria is emboldening the Syrian authorities and ensuring impunity for perpetrators of serious human rights violations.

Systematic Killings

Since anti-government protests spread to Homs Governorate in mid-March, security forces and government-supported militias there (referred to locally as Shabeeha) have killed hundreds of people. While the exact number of killings is impossible to verify due to restrictions on access and reporting, local groups have maintained a list of those killed and have registered 793 killings in Homs Governorate as of the end of September. The actual number of killed is likely higher.

Number of Civilian Deaths in Homs Governorate, March-September 2011

Many of the killings took place during attacks on protesters and funeral processions, such as killings in Homs city of protesters who had attempted to stage a sit-in at New Clock Tower Square on April 19 and the killing of 16 during a funeral near the Khaled Bin al-Waleed mosque on July 29.

While in some cases security forces appear to have initially used teargas or fired in the air to disperse the crowds, Human Rights Watch has documented several incidents when security forces opened fire directly at the protesters without giving advance warning or making any effort to disperse the protesters by non-lethal means. In several cases, witnesses told Human Rights Watch that security forces chased and continued to shoot at protesters as they were running away.

Since May security forces have conducted several large-scale security operations in Homs Governorate which have resulted in large numbers of deaths and injuries. Security operations in the towns of Tal Kalakh and Rastan, which lasted for several days, killed dozens. In Homs city, security forces have carried out operations in various neighborhoods on a regular basis. Witnesses told Human Rights Watch that security forces entered neighborhoods with tanks and armored personnel carriers and fired on civilians, sometimes from weapons mounted on the vehicles. They cut off communications and established checkpoints restricting movement in and out of neighborhoods, including delivery of food and medicine.

Witnesses said that attackers included one or several of Syria’s security agencies often referred to by the umbrella term mukhabarat (intelligence), armed pro-government militias, and sometimes army and police.

Based on witness accounts, it appears that most of the violence was perpetrated by mukhabarat forces or shabeeha militias. On several occasions, at least in the early stages of the protests, army units seemed reluctant to fire on protesters, according to the same accounts. In at least one case, mukhabarat forces appeared to shoot and kill an army officer for refusing to open fire on the protesters.

Syrian authorities have repeatedly claimed that armed terrorist gangs, incited and sponsored from abroad, perpetrated the violence in Homs and elsewhere. Syria’s official news agency, SANA, has published the names of at least 53 persons it identified as members of Syria’s security forces (police, mukhabarat, and army) who died in Syria between May 18 and September 5, 2011. Syrian human rights groups provided Human Rights Watch with a list of 93 security forces members killed in Homs between March and September 30, 2011, but they claim that many were killed by other security forces for refusing to shoot on protesters.

According to witnesses and local activists, some protesters and army defectors have used force, including lethal force, against Syrian security forces. For example, armed defectors from the army operating out of Homs and Rastan intervened in a few cases after security forces had attacked or opened fire on protestors. Many anti-government protesters who spoke to Human Rights Watch justified these attacks by arguing that they were in defense of protestors subject to unlawful attacks by the security forces. One local activist told Human Rights Watch that since July army defections had increased and that some neighborhoods in Homs had about 15-20 defectors who would sometimes intervene when they heard gunfire against protesters.

In the majority of cases documented in this report by Human Rights Watch, however, witnesses insisted that those killed and wounded were unarmed, or in some cases were throwing stones, and posed no serious threat to security forces. Statements to Human Rights Watch from security force members who defected lend credibility to this claim.

Alleged violence by protesters and army defectors requires further investigation, and those responsible for criminal acts may be held accountable and subject to lawful prosecution. However, these incidents by no means justify the massive and systematic use of lethal force against mainly peaceful demonstrators or the extensive military operations against neighborhoods or towns that have seen large anti-government protests, operations that were clearly disproportionate to any threat presented by the overwhelmingly unarmed crowds.

The decision of some protesters and defectors to arm themselves and fight back, shooting at security forces, shows that the strategy adopted by Syria’s authorities has dangerously provoked escalation in the level of violence, and highlights the need for an immediate cessation of lethal force against peaceful protests lest the country slip into bloodier conflict. As one protester who lost a cousin told Human Rights Watch:

They [the security services] shot at us for months and we kept chanting “peaceful.” They killed our families and friends, detained us, tortured us, and we kept chanting. But things cannot remain this way. How many funerals can any one person go to before deciding to fight back?[1]

Arbitrary Detention, Torture, and Enforced Disappearances

As in the rest of Syria, security forces in Homs Governorate subjected thousands of people to arbitrary arrests and systematic torture in detention. Some of those arrested were subjected to enforced disappearance.

Witnesses from Homs, Tal Kalakh, Talbiseh, and Rastan described to Human Rights Watch operations during which security forces detained dozens of people at a time, targeted arrests of activists and their family members, and arrests at checkpoints and by street patrols.

Exact numbers are impossible to verify but information collected by Human Rights Watch indicates that security forces detained up to 1,500 individuals from Tal Kalakh alone. Activists interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that thousands of people were detained in Homs city from April to August, 2011. While most were released after several days or weeks, several hundred remain missing, their fate and whereabouts unknown to their families. When anyone is detained by or with the support of the state and their detention is either unacknowledged, or their fate or whereabouts is concealed so that they are denied the protection of the law, this constitutes an enforced disappearance, a crime under international law.

Over 25 former detainees interviewed by Human Rights Watch reported seeing hundreds of others while in detention, and said detention facilities were unbearably overcrowded with guards packing dozens of detainees into cells intended for a few and holding detainees in corridors outside the cells.

Almost without exception, all former detainees interviewed by Human Rights Watch reported that they themselves were subjected to various forms of humiliation, ill-treatment, and often torture while in detention, and witnessed the abuse of other detainees. Interrogators and guards beat detainees with batons and cables whilst they were being arrested, transported, and transferred from one facility to another, and routinely during interrogation. Witnesses also reported security forces’ use of heated metal rods to burn different parts of the body, use of electric shocks, use of stress positions for hours or even days at a time, and the use of improvised devices, such as car tires (locally known as the dulab), to force the bodies of detainees into positions that make it easier to beat them on sensitive parts of the body, like the soles of the feet and head.

Deaths in Custody

One of the most worrisome features of the intensifying crackdown against protesters in Syria has been the growing number of custodial deaths that have been reported in various parts of the country, including in Homs Governorate.

Data collected by local activists indicates that more than 40 people detained from Homs Governorate had died in custody by the end of August. Human Rights Watch has independently collected information on 17 cases of deaths in detention in Homs Governorate since March 2011.

In the vast majority of custodial deaths documented by Human Rights Watch, the detainees had been victims of enforced disappearances. Families of victims told Human Rights Watch that they had no information of their relatives’ fate or whereabouts after security forces detained them at a protest or checkpoint until the day they received a call, usually from a local public hospital, asking them to pick up the body of their relative. In some cases, the bodies were found dumped in the street.

In all cases where such information was made available to Human Rights Watch, the bodies bore marks consistent with infliction of torture, including bruises, cuts, and burns. The authorities provided families with no information on the circumstances surrounding the deaths of their loved ones and, to Human Rights Watch’s knowledge, have launched no investigations. In many cases, families of those killed in custody had to sign documents indicating that “armed gangs” had killed their relatives and promise not to hold a public funeral as a condition to receive the body.

Recommendations

Human Rights Watch called on the Syrian government immediately to halt the use of excessive and lethal force by security forces against unarmed demonstrators and activists; to release unconditionally all detainees held merely for participating in peaceful protests or for criticizing the authorities; to account for all those who have been detained and forcibly disappeared; and to provide immediate and unhindered access to human rights groups and journalists to the governorate of Homs, including hospitals, places of detention, and prisons.

Human Rights Watch also called on all the members of the United Nations Security Council to take action, separately and jointly, to protect civilians by pushing for international civilian observers to deploy inside Syria, including in Homs Governorate in order to monitor human rights violations; to secure access to Syria for independent journalists, human rights monitors, and investigators; and to support investigations and prosecutions of those responsible for grave, widespread, and systematic human rights violations committed in Syria since mid-March 2011.

In the absence of collective action by the Security Council, Human Rights Watch called on all UN member states to act through the General Assembly to initiate measures to protect the Syrian people and for those states and regional bodies which have not yet done so to adopt unilateral targeted financial and travel sanctions on those officials responsible for continuing human rights violations.

Map of Homs Governorate

© 2011 Human Rights Watch

Map of Homs City

© 2011 Human Rights Watch

I. Background

Countrywide Crackdown on Protesters

Since March 2011 anti-government protests that started in the southern city of Daraa have spread across Syria. The government’s violent response has failed to quell the demonstrations, and in many parts of the country has had the opposite effect – the crowds grew bigger and new cities joined.[2]

At the time of writing, protests are still taking place regularly in the governorates of Daraa, al-Hasaka, Idlib, Deir al-Zor, Homs, Hama, and in the suburbs of the capital, Damascus.

Syrian security forces, primarily the notorious security services, referred to generically as mukhabarat, and pro-government armed groups, whom Syrians refer to as shabeeha, regularly used force, often lethal force, against largely peaceful demonstrators, and often prevented injured protesters from receiving medical assistance.[3] As the protest movement endured, the government also deployed the army, usually in full military gear and in armored personnel vehicles, to quell protests.

While witness testimonies leave little doubt regarding the extent and systematic nature of abuses, the exact number of people killed and injured by Syrian security forces is impossible to verify. Syria remains off-limits to international journalists and human rights groups, and communications are often interrupted in affected areas. However, an expanding network of activists grouping themselves in local coordination committees and making extensive use of the Internet and social groups have compiled a list of 3,121 civilians dead, including 232children, as of November 2, 2011.[4] On October 14, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Navi Pillay deplored the “devastatingly remorseless toll of human lives” in Syria and said the death toll had exceeded 3,000 people.[5]

Syrian authorities repeatedly claimed that the violence was perpetrated by armed terrorist gangs, incited and sponsored from abroad. On October 7, Syria’s deputy foreign minister Faisal Mekdad told the UN Human Rights Council (HRC) that those responsible were “criminals who have killed more than 1,100 police and security officials with arms supplied by neighboring countries.”[6]

Human Rights Watch has documented several incidents in which demonstrators, at times supported by military defectors, resorted to violence.[7]For example, demonstrators set security services buildings on fire in the towns of Daraa, Jisr al-Shughur, and Tal Kalakh, destroyed monuments to Hafez and Bashar al-Assad, and torched several vehicles belonging to the security forces.[8] Witnesses described some of these episodes to Human Rights Watch; we also viewed them on amateur videos available online. Several witnesses told Human Rights Watch that protestors had killed members of security forces, usually after the security forces had opened fire on them.

However, these incidents of violence by protesters remain exceptional. Testimony and other documentation gathered by Human Rights Watch from throughout the country since the start of the protests indicate that the majority of protests to date have been largely peaceful. But there is a risk that bigger segments of the protest movement will arm themselves in response to attacks by security forces or shabeeha. According to some reports, since August there has been an increasing trend towards armed resistance on the part of the opposition.[9]

In addition to shooting at protesters, security forces launched a massive campaign of arrests, arbitrarily detaining hundreds of protesters across the country, routinely failing to acknowledge their detention or provide information on their whereabouts, and subjecting them to torture and ill-treatment. The security and intelligence services have also arrested lawyers, activists, and journalists who endorsed or promoted the protests.

Human Rights Watch documented large-scale arbitrary detentions, including the detention of children, in Daraa, Damascus and its suburbs, Banyas and surrounding villages, Latakia, Deir al-Zor, Tal Kalakh, Hama, Homs, Zabadani, Jisr al-Shughur, and Maaret al-Nu`man.[10] The majority of the arrests seemed entirely arbitrary, with no formal charges ever brought against the detainees. Most detainees were released several days or weeks later, but others have not reappeared. Most of those cases constitute enforced disappearances as their families have had no information on their fate or whereabouts for a prolonged period of time.[11] In addition, the security forces have launched a nationwide campaign of arbitrary arrests and intimidation against political and human rights activists, holding them incommunicado, forcing them to sign undertakings to stop protesting, and in some cases torturing them.[12]

Released detainees, some of them children, said that they, as well as hundreds of others they saw in detention, were subjected to torture and degrading treatment. All of the former detainees interviewed by Human Rights Watch described appalling detention conditions, with grossly overcrowded cells, where at times detainees could only sleep in turns, and lack of food.[13]

In several cities, including Daraa, Tal Kalakh, Rastan, Banyas, Deir al-Zor, Hama, and parts of Homs, Syrian security forces moved into neighborhoods in military vehicles, including tanks and armored personnel carriers, under the cover of heavy gunfire. They imposed checkpoints, placed snipers on roofs of buildings, and restricted movement of residents in the streets. In some places, like Daraa, the security forces imposed a full-out siege that lasted for several weeks, cutting off all means of communication and subjecting residents to acute shortages of food, water, medicine, and other essential supplies.[14]

Homs: A Restive Governorate

The governorate of Homs is geographically the largest in Syria, stretching from the border with Lebanon in the west to Iraq in the east. Its capital, Homs, with a population of more than one million, is Syria’s third largest city and is located in central western Syria, along the banks of the Orontes River. Its population reflects Syria’s general religious diversity, composed mostly of Sunni Muslims but with significant Alawite and Christian minorities. Other main urban centers in the governorate are al-Qusair, Rastan, and Tal Kalakh near the Lebanese border.

Protests in Homs city erupted soon after the beginning of the Syrian uprising in solidarity with the anti-government protests that started in the southern governorate of Daraa.[15] On March 18, protesters gathered in front of the Khaled bin al-Waleed Mosque in the Khalidiyya neighborhood of Homs city, but security forces quickly dispersed them.[16] Protests spread to other parts of the governorate, erupting in Tal Kalakh in late March 2011 and in Rastan and Talbiseh in April.[17] At this writing, the anti-government movement in Homs remained strong, with almost daily protests, leading many inside Syria to call Homs the “capital of the revolution.”

On April 17, security forces killed shot 14 people in Homs city and fired tear gas and live ammunition on a separate funeral procession in Talbiseh, killing two and leaving at least 15 wounded.[18] (For more details on attacks on protesters see section II below.)

The crackdown increased sectarian tensions between Sunni Muslims, many of whom support the protest movement, and Alawites, who have in large part remained loyal to the Syrian government.[19] Many Sunni residents of the governorate told Human Rights Watch that some Alawites were actively taking part in the crackdown by for example enlisting in pro-government gangs referred to as shabeeha.[20] For their part, Alawite residents in Homs reported to Human Rights Watch that anti-government protesters have shouted sectarian chants against them during the protests and killed and mutilated Alawite officers and other citizens.[21]

Tension has been most palpable in adjoining neighborhoods of Homs city and in areas around Tal Kalakh, a majority Sunni town surrounded by mostly Alawite villages. Sectarian tensions in Homs city erupted on July 16 after the dismembered bodies of three Alawites, reportedly government supporters, were found on Hadara Street. In retaliation Alawite residents set fire to some Sunni-owned shops on the street.[22] Homs residents who escaped to neighboring Lebanon consistently told Human Rights Watch that they no longer ventured into neighborhoods or towns inhabited by groups from the other community for fear of kidnappings and harm.[23]

The security forces’ violent crackdown and increasing sectarian mistrust have led residents of some neighborhoods in the city of Homs, notably Bab Sba`, to organize themselves in local defense committees that are often armed, mostly with firearms but in some cases with rocket propelled grenades (RPGs).[24] A local resident in Bab Sba` explained to Human Rights Watch that “these committees that are formed by neighborhood youths are here to protect us from the shabeeha shooting randomly at us; to ensure that security forces do not kill us while we protest.”[25]

In parallel to these efforts, a number of soldiers – the exact number remains unknown – defected and gathered in Homs, particularly in the town of Rastan, where many of them originally hail from. Many have joined the Khaled bin al-Walid Brigade, a unit of defectors based in Homs and named after a famous historical military leader who played a key role in the early conquests of Islam in Arabia.[26]

II. Systematic Killings of Protestors and Bystanders

Because of the restrictions on access to information in Syria, the exact number of killings is impossible to verify. Information from local activists and organizations indicates that hundreds of people have been killed in Homs Governorate since protests began there in mid-March. Many of the killings took place during attacks on large gatherings of protesters and funeral processions, such as the killing of at least 13 people at the New Clock Tower Square on April 19 and the killing of 16 during a funeral near the Khaled Bin al-Waleed Mosque in the Khalidiyya neighborhood on July 19 (described in detail below). Other killings also took place during arrest operations, and there were incidents when security forces and militias opened fire at people in the street in drive-by shootings.

The “Violation Documentation Center” (VDC), a website created by a group of local activists, had registered 793 killings of civilians in Homs Governorate as of September 30, 2011.[27] Case details, such as names, dates, locations, and ages, which in a number of instances have been independently verified by Human Rights Watch, lend credibility to the number. Human Rights Watch has also documented killings not included in the list, which suggests that the list is not exhaustive.

According to the VDC, the highest number of killed were recorded in Homs city (149), Rastan (108), Tal Kalakh (45) and Talbiseh (25). In Homs city, neighborhoods hardest hit were Khalidiyya (36), Bab `Amro (27), Bab Sba’ (17), Bayyada (14) and Bab al-Dreib (12). These areas, predominantly populated by Sunnis, have been focal points for anti-government demonstrations.

Use of force by state security forces acting in a law-enforcement capacity must comply with standards set out in international law. Syria is a party to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and has specific treaty obligations to respect the rights to life and security, and to peaceful assembly. In most cases documented by Human Rights Watch, the use of force by security and law-enforcement officials appears to have been excessive and a violation of Syria’s international obligations.

The UN Code of Conduct for Law Enforcement Officials states that “law enforcement officials may use force only when strictly necessary and to the extent required for the performance of their duty.”[28]

The UN Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms provides that law enforcement officials “shall, as far as possible, apply non-violent means before resorting to the use of force” and may use force “only if other means remain ineffective.”[29] When the use of force is necessary, law enforcement officials must “exercise restraint in such use and act in proportion to the seriousness of the offense.”[30]

Article 10 of the Basic Principles requires that law enforcement officials “give clear warning of their intent to use firearms.”[31] Article 9 states that “intentional lethal use of firearms may only be made when strictly unavoidable in order to protect life.”[32]

The Basic Principles make clear that there can be no departure from these provisions on the basis of “exceptional circumstances such as internal political stability or any other public emergency,” i.e., these are non-derogable standards.[33]

Attacks on Protests and Funeral Processions

Human Rights Watch has documented dozens of incidents in which security forces and government-supported militias used violence to attack and disperse overwhelmingly peaceful protests.

Some of the most deadly attacks documented by Human Rights Watch include:

- Killing of an unknown number during protest at New Clock Tower Square, Homs city, April 19.

- Killing of 27 during protests in Homs city, April 22.

- Killing of 30 during protests in Rastan, April 29.

- Killing of 7 during protests in Homs city, June 17.

- Killing of 5 during protests in Homs city, June 21.

- Killing of 8 during protests in Homs city and suburbs, June 24.

- Killing of 5 during protests in the Wa`er, Khalidiyya, and Bab `Amro neighborhoods, Homs city, July 15.

- Killing of 16 during funeral at Khaled Bin Al-Waleed Mosque in Homs city, July 19.

- Killing of 3 during protest outside the Omar Ibn al-Khattab mosque, Homs city, August 1

- Killing of 3 during protest near Khaled bin al-Waleed Mosque, Homs city, August 5.

- Killing of 4 during UN humanitarian assessment mission, Homs city, August 21.

Witnesses told Human Rights Watch that security forces often resorted to lethal force even when protesters did not pose any threat to them. In several cases, security forces initially used teargas or fired in the air to disperse the crowds, but then opened fire with live ammunition directly at protesters who had not run away, the witnesses reported.

A typical example is the August 1 attack on protesters gathered outside the Omar Ibn al-Khattab mosque in the Mal`ab neighborhood of Homs city, during which three people were killed.[34] Amjad (not his real name) witnessed the attack and told Human Rights Watch:

Two buses with about 50 security forces wearing green showed up after people emerged from the mosque. The buses went by me, so I was basically between the security forces and the protesters. They [security forces] had electric batons and immediately threw three tear gas canisters and sound bombs as soon as they got out of the buses. Most of the protesters ran away, but around 200 stayed. At this point, the security forces attacked them. They used live bullets. Protesters were hiding in the alleyways off the main street. One man was shot with one bullet in his thigh and another in his testicles. We know about him because we treated him and took him to the hospital, but there were so many more.[35]

Louai (not his real name), whose brother was among the three people killed on August 1, told Human Rights Watch in a video testimony:

Suddenly a BTR [armored vehicle] comes out from Bottoul Street, next to a mall called Smart Mart. It had automatic weapons on the roof. Only ten of us were left trying to help the injured people and the ones who passed out from the tear gas. The BTR started firing at us as we were running away towards Hamra or Ghoutta Streets. When we reached Ghoutta Street, with bullets passing between our legs, a doctor and I hid in the first building that had its door open. Two meters away a man gets shot and falls between two cars. Then my brother gets killed while trying to move to another street to help his friend who was shot in the leg.[36]

Both witnesses told Human Rights Watch that none of the protesters had any weapons on them. Human Rights Watch has been unable to determine in this case whether protesters had thrown rocks at the security forces.

In other cases, witnesses told Human Rights Watch that security forces fired directly at protesters – or mourners at funeral processions – without giving advance warning or making any effort to disperse protesters by nonviolent means. Mohammed (not his real name), whose 21-year-old cousin was among 16 killed when security forces and pro-government militias attacked people who had gathered for a funeral near the Khaled Bin al-Waleed mosque in Homs on July 19, told Human Rights Watch:

As we were burying the dead, I suddenly heard gunshots. Four pick-up vehicles with people in uniforms, helmets, and body armor drove up, shooting at the people with their automatic guns and guns mounted on the vehicles.

We started running away. The mother and brother of one of the dead were killed next to his coffin. My cousin tried to drag the mother’s body away. He suddenly fell, but I didn’t know at that time that he had been hit. As I was running away I saw an armored personnel carrier also shooting. I don’t know whether they were shooting in the air or at the crowd.[37]

Muhammad told human Rights Watch that he did not see any protesters attack the security forces. Muhammad’s version of the incident was corroborated by two other witnesses.[38] A paramedic who arrived to the Khalidiyya neighborhood after the incident told Human Rights Watch that he treated a number of men who had been shot in the abdomen and chest. “There were too many injuries to treat them all,” he said.[39] Human Rights Watch also reviewed video of the incident and of a convoy of pick-ups, ambulances, and what appear to be armored vehicles, which support the allegation that security forces were involved.

In a similar incident, security forces attacked protesters without warning in the Khalidiyya neighborhood in Homs on August 5, 2011. Maher (not his real name), a protester, recounted the incident to Human Rights Watch:

We walked through the street after Friday prayers, passing the checkpoint run

by Air Force intelligence and military forces. They made note of us. After we

passed, they started shooting along the street. Some old people had stayed in

the mosque, but when they tried to leave the forces fired even on them, on

everyone passing in the street. They shot one man in his leg. Another man, an

old man, tried to help him, but they shot him in the hand.

[40]

According to Maher, the protesters were not armed and represented no threat to the security forces.

In another example, two unmarked cars and armored vehicles from the army opened fire on a peaceful evening demonstration in the neighborhood of Bab Dreib on August 15. A woman who participated with her three-year-old told Human Rights Watch:

We went out in a peaceful protest with the whole family in Bab Dreib at about 10:30 or 11:00 p.m. last night. It was calm, so everything seemed ok. Then two cars showed up suddenly and opened fire, targeting people even as they were ducking and lying on the ground. They were white Kia Cerato cars with tinted windows, like those used by Air Force intelligence. The guns were machine guns. My husband leaned over our son to protect him, but the bullet entered our boy’s stomach. The doctors were able to remove the bullet, but it left a lot of damage.

People tried to run out and help the approximately 20 injured lying there, but then a tank [probably referring to an armored vehicle] came from the other end of the street, trapping us between the cars and the tank. The tank opened fire using large bullets, the kind that can bring down walls. It fired on walls and houses, since by then everyone had run inside.

Three hours later, more tanks and cars showed up and again started firing randomly. In all, I saw four people killed, all by machine guns from those two cars. I don’t know their names, but one was pregnant, one was about a year-and-a-half old, one was 30 years old, and one was 25 years old.[41]

Another witness interviewed separately by Human Rights Watch described the attack in similar terms.[42] Human Rights Watch has not been able to obtain the names of those killed on August 15.

Security forces also opened fire on protesters who had gathered near the New Clock Tower Square on August 21 to attract the attention of a UN humanitarian assessment mission. Witnesses told Human Rights Watch that security forces killed four protesters.[43] Human Rights Watch reviewed two video clips taken in the area around the New Clock Tower Square that day, which show protesters being wounded by gunfire.[44] It is not clear from the videos who shot at the protesters, but in one of the videos security forces are seen nearby. None of the protesters in the footage were carrying any weapons. In one of the videos, some protesters can be seen throwing rocks at the security forces, but there was no evidence that they presented any lethal or serious threat to the security forces.

One journalist later reported that an opposition leader who was present told him that a group of defectors from the Syrian army intervened to defend the protesters and shot back at the security forces, killing two.[45] Human Rights Watch has been unable to independently verify an armed attack by the protesters in this instance.

In other instances, security forces continued to shoot at protesters as they were running away, indicating that lethal force was clearly not necessary because the protesters posed no threat to the forces while running away. Abu Wasim (not his real name), who was filming a protest in the Khalidiyya neighborhood on July 15, told Human Rights Watch:

Suddenly, they fired three shots in the air and then opened fire on us. Six protesters fell in front of me. We started running. Suddenly, we saw two red police cars, both Kia Rio station wagons, and a small white bus full of security services. The vehicles intercepted us and the security officers got out of the vehicles and started shooting without any warning. Nine people were wounded. Four were in critical condition and we took them to makeshift hospitals. Security officers took another three. I don’t know what happened to the other two.[46]

Syrian activists provided Human Rights Watch with the names of five protesters killed that day in Homs.[47]

Based on the accounts witnesses gave to Human Rights Watch in the various attacks the perpetrators included one or several of Syria’s security agencies (mukhabarat), armed pro-government militias often referred to as shabeeha, and sometimes army and police. According to the witness accounts, most of the violence was perpetrated by mukhabarat forces or shabeeha militias. In at least one case, in Tal Kalakh on May 14, a witness said that mukhabarat forces shot to death an army officer for refusing to open fire on protesters.[48]

Use of force by protestors

Syrian authorities have repeatedly claimed that the violence in Homs was perpetrated by armed terrorist gangs, incited and sponsored from abroad. Syria’s official news agency, SANA, has published the names of 53 members of Syria’s security forces (police, mukhabarat, and army) who died in Homs between May 18 and September 5. According to SANA, they were killed by “armed gangs” or “terrorists.”[49]

In almost all cases documented by Human Rights Watch, witnesses insisted that those killed and injured were unarmed and posed no threat to security forces. Statements from several security force members who defected lend credibility to this claim.[50]For example, a mukhabarat officer who defected told Human Rights Watch that a high-ranking mukhabarat officer ordered the soldiers to fire on the protesters holding a sit-in in the New Clock Tower Square in Homs on April 19, even though they knew that the protesters were unarmed. The soldiers complied, he said. He told Human Rights Watch:

The protesters had sat down in the square. We were told to disperse them with violence if needed. We were there with Air Force security, army, and shabeeha. At around 3:30 a.m., we got an order from Colonel Abdel Hamid Ibrahim from Air Force security to shoot at the protesters. We were shooting for more than half an hour. There were dozens and dozens of people killed and wounded. Thirty minutes later, earth diggers and fire trucks arrived. The diggers lifted the bodies and put them in a truck. I don’t know where they took them. The wounded ended up at the military hospital in Homs. And then the fire trucks started cleaning the square.[51]

Two witnesses corroborated the mukhabarat officer’s version of the events.[52] One witness who was at the square told Human Rights Watch:

At around midnight, a sheikh approached the speaker’s platform underneath the clock tower and announced that he had received a call from an officer in the Presidential Palace threatening that all protesters must disperse or face the consequences. The sheikh urged protesters to leave. Many did leave, but a group of around 3,000 remained. At around 2:15 a.m., we suddenly heard heavy gunfire. At the beginning, it looked like the security forces were shooting in the air. People started running away. As I was running, I heard people shouting that someone had been shot. A few of us tried to go get him but others then shouted that he had died. For 20 minutes, all we could hear was non-stop gunfire. I sheltered in a neighboring building on Dablan Street until the morning. At 7:30a.m., I left the building and could see some blood stains on the ground. There were crews cleaning the street, as if nothing had happened.[53]

To date, the exact number of dead from the night of April 19 remains unknown. According to the witnesses, many protesters who were in the square when the security forces opened fire were from villages and areas near Homs, which makes it harder for activists to collect the names of the dead. The VDC published the names of at least 7 people killed in Homs on April 19.[54]Activists showed Human Rights Watch footage of five gravely wounded persons being treated at Al-Bar Hospital. After the incident local activists reported that 150 people from the sit-in had gone missing. While many of those turned out to be detained, local activists reported that the whereabouts of at least 30 people remained unknown at the end of July. According to an October 14 email to Human Rights Watch from a spokesperson of the Local Coordination Committees, a coalition of anti-government activists who organize and publicize protests,35 bodies were found in a garbage dump near al-Nasr Cemetery the day after the attack and 45 funerals were held in the following days.[55] Human Rights Watch has not been able to independently confirm this information.

While protesters appear to have been unarmed in most incidents, armed defectors intervened on some occasions after protesters came under fire from security forces. One local activist explained to Human Rights Watch that since June, army defections had increased and that many neighborhoods had about 15-20 defectors who would sometimes intervene when they heard gunfire. The activist recounted one incident he witnessed in Homs city on July 8:

There was a huge protest. Thousands of protesters marching from three mosques eventually joined at a roundabout near Brazil Street. Security forces first fired teargas. Then they opened fire with blanks, before they started using live fire. About seven protesters were injured. At that point, several defectors showed up on motorcycles and killed 14 or 15 members of the security forces using Kalashnikovs and pump-action shotguns. By the time the security forces returned with reinforcements, the protesters had dispersed.[56]

The activist claimed, however, that there were no armed defectors during the initial weeks of the protests or at the July 29 funeral, where he was present, during which 16 people were killed.[57]

A resident of Bab Dreib told Human Rights Watch that around 20 armed men, some soldiers who defected, and other local residents began protecting the neighborhood after security forces launched a large attack on Hama in early August:

[The defectors and residents] would not usually initiate any attack or carry their weapons openly. But if protesters would come under fire, then these men would try to shoot the security forces. Many of them were in Bab Dreib because they can hide in the neighboring groves.[58]

Violence by protesters or defectors deserves further investigation and anyone responsible for criminal activity may be held accountable and liable to lawful prosecution for crimes committed. However, these incidents by no means justify the disproportionate and systematic use of lethal force against demonstrators, which clearly exceeded any justifiable response to any threat presented by the overwhelmingly unarmed crowds.

Killings during Sweeping Military Operations and Mass Arrests

Since May, security forces have conducted large-scale operations in several towns in Homs Governorate, some of which resulted in many deaths and injuries.

Typically, security forces used heavy machine guns, including anti-aircraft guns mounted on armored vehicles, to fire into neighborhoods to scare people before entering with armored personnel carriers and other military vehicles. They cut off communications and established checkpoints restricting movement in and out of neighborhoods and delivery of food and medicine. These operations also involved large-scale arrest campaigns (see chapter on arbitrary detention below).

The killings occurred as a result of heavy machine gun fire from military vehicles, which sometimes penetrated people’s homes or hit them randomly; shootings by security personnel manning checkpoints or by snipers when residents tried to travel in or out of cordoned-off neighborhoods; or during arrests.

International law permits law-enforcement officials to use lethal force only to the extent absolutely necessary to prevent harm to themselves or others. The indiscriminate use of heavy machine guns in populated urban neighborhoods in the absence of sustained armed resistance violates those norms and places at risk the rights of residents to life, bodily integrity, and security.

Tal Kalakh, May 14 – 19

On May 14, security forces launched a large-scale operation in Tal Kalakh, a town of around 80,000 near the Lebanese border on the western edge of Homs Governorate. According to locally elected officials in Lebanese border towns, 3,500 Tal Kalakh residents had sought shelter in Lebanon by May 20.[59] Human Rights Watch interviewed 18 of those residents in May and June. According to those interviewed, a large peaceful protest took place in Tal Kalakh the previous day.[60] A 35-year old woman, Umm Omar (not her real name), who watched the protest from her home, located about 200 meters away from the Omar Ibn al-Khattab Mosque, told Human Rights Watch:

After the Friday midday prayer, people exited the mosque and marched through town to express their support for the people of Baniyas and call for freedom. I did not take part because my family had received a phone call from the security services two weeks earlier warning that if any of us protested, they would harm our relative who is detained at the Air Force branch of the security forces. I did not see any of the protesters with guns.[61]

Umm Omar reported that shortly after the demonstration began, a police car drove through town warning residents by loudspeaker that there were “terrorist snipers” in town. Shortly thereafter, snipers did appear on roofs throughout the city and opened fire on the protesters, she said, and the protesters dispersed.[62]

At around 4 a.m. on May 14, tanks and armored personnel vehicles surrounded Tal Kalakh, four witnesses from the town told Human Rights Watch.[63]At around 6:15 a.m., residents started hearing heavy gunfire as well as shelling. A family from the Burj neighborhood reported that water and electricity were cut off at about 8 a.m.[64]

The heavy gunfire prompted hundreds of people to attempt to escape to neighboring Lebanon. Six of those who made it to Lebanon and spoke to Human Rights Watch reported coming under fire as they escaped. A resident who crossed to Lebanon on foot with a neighbor reported coming under sniper fire and machine gun fire from men wearing camouflage, which led to his neighbor’s death.[65]

Another man, who fled midday on May 14 in a taxi with a driver and five women, said their car was fired upon from the direction of a Meshta Mahleh, an Alawite village located about halfway between Tal Kalakh and the Lebanese border. He reported seeing about ten men with automatic weapons in the hills near the village. A 25-year-old woman in the car was hit by a bullet in her leg.[66]

A witness from Lebanon reported seeing a group of families attempting to run across the bridge at the main border crossing in `Arida, but receiving fire from the surrounding hills. “The bullets came like rain,” he said. When the firing started, Lebanese soldiers at first dropped to the ground, but then helped the families across the border. The witness said he saw bullets hitting Lebanese military vehicles. He took a woman who was bleeding profusely to the hospital in Lebanon, he said.[67]

That evening, a group of Tal Kalakh residents organized a truck to transport civilians to Lebanon, two women who rode in the truck told Human Rights Watch. Both women reported that the truck was guarded by a team of young men armed with guns on motorcycles on its first trip, which passed without incident. The truck returned to Tal Kalakh to pick up more women and children, but came under heavy fire the second time, they said, when the truck was protected by less people than it had been earlier.[68]

A woman who was in the truck on its second journey when it came under fire told Human Rights Watch:

When the truck arrived, there were so many people piled on top of each other. The truck came under fire halfway through the 15-minute trip, as it was passing the village of Mashteh Mahleh, hitting the truck’s tires and forcing us to ride the rest of the way on the rims. Once we got to the border, men wearing black and with red armbands opened fire on us. I saw two men, Maiz Haloum and Muhammad Haloum, killed as they helped people across the river that separates Syria from Lebanon.[69]

Residents who remained in Tal Kalakh reported hearing heavy gun fire all day on May 15 and on the morning of May 16. All witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch were hiding inside their homes and did not have any details on casualties. One family from the Burj neighborhood benefitted from a lull in the shooting on May 16 to escape. The mother told Human Rights Watch:

At 4:00 a.m. on Monday [May 16], there was a lull in the fighting and we left on foot with our children. We saw tanks throughout the city. There were some corpses in the streets but I don’t know how many as it was still quite dark. By sunrise, we reached another village near the Lebanese border, where we rested briefly and drank water. We heard gunfire start again and proceeded another three kilometers to cross the river into Lebanon. We were 13 in the group that tried crossing. The Syrian army was up in the hills, 100 to 500meters away from the river. They opened fire on us and yelled orders for us to return. We ran so quickly we couldn’t see who made it and who didn’t.[70]

A man who left Tal Kalakh in the early hours of May 17said that he counted more than 74 tanks and armored personnel vehicles around the town.[71]

Many residents told Human Rights Watch that they were hiding and did not know if security forces encountered any armed resistance. One resident told Human Rights Watch that he saw eight tanks and armored personnel carriers (APCs) damaged as he was leaving town. He later heard from some residents that it was men from Tal Kalakh who had shot at the tanks and APCs with machine guns and rocket-propelled grenades.[72]

On May 17 and 18, security forces carried out house-to-house searches in Tal Kalakh, detaining a large number of men and boys, regardless of age. A 66-year-old man who had stayed in Tal Kalakh told Human Rights Watch about his arrest on May 17:

My family escaped in the early hours of May 17. But I decided to stay in my house. At my age, I had no desire to walk across hills and rivers. At 9:30 a.m., around 20 men from the army and the security forces stormed my house and took me in my pajamas to the hospital, which they had turned into a detention facility. I saw three children detained with us. They were around 13-years-old. They put us in cramped cells and beat us multiple times a day. My age shielded me somewhat, but they still beat me on my face and back and electrocuted me twice with an electric baton. I was released seven days later. [73]

At least 34 people were killed during the security operation in Tal Kalakh between May 15 and 18, according to the Violations Documentation Center.[74]

Rastan, May 29 – June 3

On May 29, security forces entered Rastan, a city of an estimated 50,000 residents 20 kilometers north of Homs, cutting off water, communication, and electricity supply to the city. The operation followed a demonstration on May 27, the largest one in Rastan up until then. Security forces also entered the nearby towns of Talbiseh, Teir Ma`aleh, and Deir Ba`albeh, forming a belt around northern Homs.[75]

According to phone interviews with five residents in Rastan as well as 10 videotaped testimonies of witnesses that local residents and activists provided to Human Rights Watch, security forces shelled mosques, a cemetery, the town’s main bakery, and a number of homes, and opened fire on people in the streets in the course of the five-day long security operation.[76] At least 75 people were killed during the operation, according to the Violations Documentation Center.[77]

Several of those killed had multiple gun wounds. One example was 14-year old Abdallah Abdel Razzak Jeha from Bagha, a neighboring village. According to a relative, who provided Human Rights Watch with a video testimony, Abdallah left the village on May 29 to bring food to Rastan, but never came back. After a couple of days, a security official told the family to collect the body from the National Hospital in Homs. The relative said in the video testimony:

We went to pick up the corpse from the hospital where we were ordered to perform a normal funeral procession without any protests. When we brought his corpse back home we saw five bullet shots; one in his head, one on the left side of his chest, two in his stomach, and one in his leg.[78]

Human Rights Watch reviewed footage of Abdallah’s body that matches the description by the relative.

Another witness, whose son had been killed during the operation, told Human Rights Watch:

The military was shooting randomly. My son went out of the house [on May 29] heading towards the industrial area and never came back. In the meantime, shooting intensified. We started looking for him. Every day or two we received news from people saying either that he was injured, shot, or he’s in the custody of one of the security branches. We searched in hospitals but didn’t find him. On June 28, we received a call saying that an unidentified body from Rastan is at the morgue of the National Hospital. It turned out to be his body. We brought the body to Rastan. While washing his body for burial we saw two gunshot marks that looked like a bullet entered his ear and exited from his head. Another gunshot wound was visible on his stomach, right hand, and shoulder.[79]

A video of the corpse reviewed by Human Rights Watch shows a bullet entry hole in the victim’s stomach and ear and bruises on his face.

A lawyer from Rastan told Human Rights Watch that during the first day of the military operation on May 29 security forces killed around 20 protesters and injured 40. One of those killed was his 25-year-old nephew, Muhammad Amin Abdel Hassib al-Ashtar.[80]

According to media reports, local activists documented the killing of another five people in Rastan on May 31, the same day that President al-Assad issued a general amnesty covering members of “all political movements.”[81]One of the victims was four-year-old Marwa Hassan Shakhdu.[82]

The following day, June 1, SANA quoted a military source saying army and security forces seized weapons and ammunition in Rastan and killed or injured “a number of armed terrorists.”[83]Three soldiers were killed in the operation and seven injured, according to SANA. In an email to the media on May 31, LCC activists contested government accounts of protester violence and vandalism, claiming security forces had set the police station alight to destroy their own files.[84]

The shelling continued until June 2. A Rastan resident, a lawyer, who was wounded on June 2 stated in a testimony videotaped by a local activist:

On June 2, Rastan was still besieged by security forces. I was crossing the main road near my house by the Rastan bridge when I was shot by military forces stationed next to the Rastan National Hospital. Subsequently, the military forces repeatedly called out loudly for me to walk towards them. I got to my knees and raised my hands, covered with blood, to show them that I am injured and incapable of walking. They insisted that I walk towards them or else they will shoot at me again. I pulled my strength together, stood up and started walking slowly along the bridge.

As soon as I approached them, they grabbed me like the beast that jumps on its prey and forced me to lie on the floor while they encircled me and started taking pictures, cursing, and searching me for possession of a weapon. I later found out that they stole my mobile and around 7,000 Syrian pounds [around $140], they only left my ID. When the military forces found out that I am a lawyer they started calling me “leader of the Islamic Kingdom” and accusing me of plotting the terrorist attacks in the country. In the meantime, the ambulance arrived and drove me with the military forces to the National Hospital in Hama. [85]

Sniper fire stationed on rooftops continued into June 3, killing another six people, according to VDC tallies. Local activists told Human Rights Watch that they were sure the snipers were security forces. [86] LCC activists reported in an email update on June 3 that security and military forces firing machine guns stormed houses in Rastan to conduct arrests. They also reportedly bombed the home of Fatima Umm Akram Alwan. [87]

Homs

In Homs city, security forces conducted operations on a regular basis, targeting different neighborhoods. Operations varied in scope and intensity; several led to injuries and deaths.

Between July 21 and 25, for example, security forces cordoned-off several neighborhoods, including Bab Sba`, Khalidiyya, and Bayyada. Movement was restricted, and residents from neighboring areas attempted to organize delivery of food and medical supplies to the cordoned-off areas. Witnesses told Human Rights Watch that the injured were afraid to seek treatment in public hospitals and that the blockade had made it much more difficult to get injured to hospitals deemed to be safe. Many of the injured were being treated in private houses.

Abu Adam (not his real name) told Human Rights Watch:

Security forces blocked off Bab Sba` completely [on July 21]. Cars trying to get through were shot at from heavy military vehicles and pedestrians and bicycles were shot at by snipers. When we tried to bring food and medicine into the area on the morning on July 21, security forces opened fire. They killed one person, injured a second, and arrested the third.[88]

On at least one occasion in the following days, security forces and men in civilian clothes driving through the neighborhoods opened fire on residents who happened to be out in the streets. Abu Ahmad (not his real name), a resident of Bayyada neighborhood, told Human Rights Watch that he saw one person killed and about 20 injured in drive-by shootings on July 25. According to Abu Ahmad, who was sitting outside his house on al-Zir Street, people in civilian clothes and body armor driving a pick-up truck and a taxi opened fire on people in the street around 7 a.m., killing Khaled al-Awayshi, a neighbor. Abu Ahmad told Human Rights Watch that he watched as the pick-up drove to the Air Force intelligence base, around 600 meters away. Shortly thereafter, three armored military vehicles arrived, also opening fire. According to Abu Ahmad, most of the injured were shot from the military vehicles.[89]

In another example, local activists told Human Rights Watch that 12 people were killed in an operation that started on August 10.[90] One Homs resident told Human Rights Watch:

The attack started yesterday [August 10] at about 4 a.m. and continued until today [August 11]. The sounds were enormous. There were constant explosions and .50 BMG [refers to large bullets used in machine guns] fire coming from Bab `Amro and Insha’at next to the bakery. This gunfire has a very particular sound. There was a break around iftar time yesterday [6:00 p.m.], then it started up again, but not as heavy.

I tried to go to those areas by car, but the police had blocked off Brazil Street, close to Bab `Amro. Then after the taraweeh prayer [special prayers performed every night during the month of Ramadan] I was in al-Mal`ab and there were no police, which is very unusual for al-Mal`ab. Normally, security forces are there every day shooting in the air, since this is a popular, important area. Around 11 p.m., when I was back home in Khalidiyya, the shooting intensified again and didn’t let up until 6 a.m. this morning, sometimes with great intensity and sometimes with small guns. This morning I was at Dablan Street and heard sounds from Bab `Amro. The police forces and some soldiers were surrounding the neighborhood. There were no communications inside – no phone, no mobile, no internet.

The security forces were searching for a list of wanted men. We live as in war. We didn’t sleep all night last night. The shooting and fire came from everywhere, from yesterday until today.[91]

III. Arbitrary Detention, Torture, and Enforced Disappearances

As in much of the rest of Syria, security forces in Homs Governorate subjected thousands of people to arbitrary arrests, enforced disappearances, and systematic torture in detention.

Witnesses from Homs city, Tal Kalakh, and Rastan described to Human Rights Watch large-scale operations during which security forces detained dozens of people at a time, targeted activists and their family members for arrest, picked up people at checkpoints and by street patrols.

Exact numbers are impossible to verify, but information collected by Human Rights Watch suggests that the security forces detained more than 1,000 individuals from Tal Kalakh alone. Activists interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that thousands of people were detained from April to August in Homs city. While most were released after several days or weeks in detention, at this writing several hundred remain missing, apparently subjected to enforced disappearances, their fate and whereabouts unknown to the families.[92]

All the former detainees from Homs Governorate interviewed by Human Rights Watch reported seeing hundreds of others while in detention, saying that the detention facilitates were unbearably overcrowded with guards packing dozens of detainees into cells intended for a few and holding detainees in the corridors outside of the cells. For example, one witness told Human Rights Watch that in the State Security detention facility in Homs, just in the immediate vicinity of his small cell that held eight detainees, there were 14 other small cells, each holding approximately the same number of persons, and one large cell with many more inside. In addition, he said, he could see other detainees in the corridor between the cells.[93]

Most detainees were young men in their 20s or 30s, but security forces also detained children and elderly people. Several witnesses reported the detention of their parents or grandparents – individuals in their 60s and 70s. Human Rights Watch documented the detention and beating of two 13-year-old boys in Tal Kalakh; other released detainees also reported seeing many teenagers in detention.

Witnesses from Homs city and neighboring towns described to Human Rights Watch sweep operations that security forces conducted in their neighborhoods following the protests. They said that joint groups of military personnel, mukhabarat, and shabeeha militias moved through the neighborhoods grabbing people in the streets and breaking into houses. At times, they had lists of individuals they were looking for, and on several occasions, when the people they wanted were not at their homes, they detained their relatives. On other occasions, they randomly detained people from the street or from their homes.

Witnesses from Tal Kalakh told Human Rights Watch that following massive protests there on May 14-15, security forces moved into the town and arrested hundreds of people in different neighborhoods. A majority of witnesses from Tal Kalakh had been either arrested themselves, or had family members or neighbors who were detained.

One of the witnesses, Ali (not his real name), said that following the protests in Tal Kalakh on May 14-15,he spent several days in hiding, moving from house to house. He said:

I was hiding in water ditches, and saw security forces arresting people from every house on the street. The detainees were too many to count. Security forces pushed them to the ground and walked on them. Sometimes, they made them chant praises to Bashar al-Assad before putting plastic handcuffs on them and leading them away.[94]

Another witness, Mahmud (not his real name), said that he fled from the house when the security forces came to his neighborhood on May 15, but they took away his 51-year-old father. He said:

I was hiding in a house across the street and saw that they broke into our house and dragged my father out. They pushed him on the ground and started beating him, demanding that he praise Bashar al-Assad. He had to do it. They were about 10-15 men, some in military uniforms, with special forces badges, and some in black uniforms and white sneakers; I believe these were from mukhabarat. They blindfolded him and took him away in a taxi. For 24 days we had no information about his whereabouts, and then my uncle found him in the central jail in Homs, and managed to get him released on bail. When he was released his front teeth were broken and his face and eyes were swollen.[95]

A witness told Human Rights Watch that on June 24 he saw plainclothes security personnel emerge from a taxi with the license plate number 747191 to detain a young man walking in front of Abdulhamed al-Zehrawy High School in the Homs neighborhood of Insha’at. Seven police officers on motorcycles joined them in beating the man, then put him a security bus, the witness said.[96]

Three protesters described to Human Rights Watch events in the Mal`ab neighborhood on July 8, when about 200 security forces dispersed a protest of about 1,000 people and detained 10 protesters. The three witnesses said that five protesters tried to escape and hid in a nearby house, but were spotted by security men, who came after them, broke the door of the house, and arrested all five, along with the doorman, who was not involved.[97]

A resident of Khalidiyya, Abu Ahmad (not his real name), told Human Rights Watch that around a hundred people from his street were detained during June and July and that the whereabouts of many remain unknown. He described a security raid that he witnessed in his neighborhood on July 26:

Around 4 p.m. yesterday, more than a dozen pick-up trucks and two army buses entered the al-Sharakes street in the Khalidiyya neighborhood. They just arrested everybody they saw in the street right outside my shop. They stayed there for several hours. By the time they left they had arrested more than 40 people. I have no idea where they took them.[98]

In Homs and neighboring towns security forces also conducted targeted arrests of wanted activists, people suspected of collecting and disseminating information about the protests, and doctors and nurses who assisted wounded protesters.

On May 12, 2011, Muhammad Najati Tayyara, a human rights activist from Homs who had spoken with the international media about the government’s crackdown, was detained on a street in Homs, a friend of his told Human Rights Watch. According to Tayyara’s lawyer, he has been held in a basement storage room in Homs’ central prison, along with others arrested during protests. Tayyara has been able to see his family and lawyer once a week for 15 and 30 minutes, respectively. His lawyer said that a court in Damascus is examining possible charges of “spreading false or exaggerated information that weakens national sentiment while Syria is at war or is expecting a war” or “spreading lies harmful to the prestige of the nation.”[99]

In Homs city, security agents arrested two doctors, Eyad Rifa`i, an orthopedic surgeon, and Jalal Hasoun al-Najar, a neurologist, on July 7 and July 9 respectively. Authorities accused both men of providing medical assistance to wounded protesters and information to international reporters about the crackdown, friends told Human Rights Watch. Rifa`i drove himself to the Air Force branch of security after receiving an order by phone to come in, said a friend. Agents from the military security branch arrested al-Najar at his clinic in Homs, and the next day went to his house and took his laptop and mobile phone.[100] Activists told Human Rights Watch that on July 13, both a city official and the medical association in Homs petitioned the military security branch for al-Najjar’s release, saying that treating the wounded is not a crime. According to one activist, security authorities replied to the city official that al-Najjar had been arrested not for his medical activities, but for alleged political activities.Both men were released on August 19.[101]

In addition to sweeps and targeted arrests during and following protests, security forces also detained people at checkpoints and during patrols. In one case documented by Human Rights Watch, on May 18, 2011, two 13-year-old children were detained in Tal Kalakh on their way to school. One of them told Human Rights Watch:

We were passing near Abu Arab square, and there was a big checkpoint there, with several tanks and concrete slabs. The military stopped us and asked where we were going. We said we were going to our school, but when they heard it was a religious school, they got very angry, and started yelling, calling us “pigs who want freedom.” We tried to explain that we had nothing to do with the protests, but they beat us, and then blindfolded us and put us in car. They took us to some room with a horrible smell where we spent the next two hours. Every now and then somebody came and beat us with fists and wooden clubs. Then they released us – just dropped us on the side of the street, saying somebody would pick us up and bring back to town.[102]

Torture in detention

The pattern of systematic and rampant torture in detention that Human Rights Watch documented in Daraa and other parts of the country has repeated itself in Homs Governorate as well. Almost all of the 25 former detainees interviewed by Human Rights Watch reported being subjected to various forms of torture while in detention, and witnessing the abuse of fellow detainees.

According to former detainees, the majority of those detained in Homs city and nearby towns were held in the Homs Military Intelligence base, Balooni military prison – often used as a holding facility for detainees to be transferred to other cities or to other intelligence agencies – and branches of Political Security, State Security, and Air Force Security.

Detainees provided consistent accounts of appalling conditions in detention, including overcrowded cells with no ventilation, lack of food and water, and limitations on the use of toilet.

One witness, Abu Adam, who was detained in early July along with 11 other protesters from the Khalidiyya neighborhood in Homs, described to Human Rights Watch the conditions in a State Security detention facility in Homs:

The conditions were horrible. The cell measured 1.7 by 2 meters. There were eight of us there. There was a tiny window high up on the wall, but it provided no light or air. We had to take turns sleeping on each other’s shoulders. There was no place to lie down. I was dripping with sweat from head to toe. They gave us two loafs to share twice a day and a bottle of water. Twice a day they gave us 10 seconds to use the toilet.[103]

Another former detainee, Omar (not his real name), who was held first at the Balooni Prison in Homs and then at the Military Intelligence base in Homs along with his father and five brothers, told Human Rights Watch:

On the 23rdday of detention, they moved us to the Military Intelligence base where they squeezed 50 of us into a tiny room. We could only stand; we were pushed so close together that it was hard to breathe. We stayed there for 10 hours. My 73-year-old father almost died – they took him out after 40 minutes.[104]

Another former detainee held by Military Security in their detention facility in Homs, told Human Rights Watch that security forces placed him with two other detainees in a small cell measuring 0.90 by 2 meters, and that they had to take turns sleeping. He told Human Rights Watch that there were 20 individual cells similar to his, all occupied by three individuals.[105]

Interrogators and guards routinely subjected detainees to beatings with batons and cables during arrest, transportation, and during interrogations. Witnesses also reported other forms of torture, including burning of different parts of bodies with heated metal rods, use of electric shocks, drilling or cutting holes in bodies, use of various stress positions for hours or even days, and the use of improvised devices, such as car tires, to immobilize the bodies of detainees and ease their beating on sensitive areas like the soles of their feet, their head, and backs. Witnesses provided Human Rights Watch with video and photo materials that show marks left by these forms of torture on the bodies of the released detainees as well as the bodies of detainees who had died in detention (see below).

One witness, Wael (not his real name), described the torture he and other detainees experienced at the Military Intelligence base in Homs:

They brought me into what felt like a big room with lots of people inside. I was blindfolded but could hear people around me screaming and begging for water. I could hear the sound of electric tasers and interrogators ordering to hang people by their hands. Once they got to me, they started mocking me, saying, “We welcome you, leader of the revolution,” and asked me what was going on in Tal Kalakh. I said I didn’t know, and then the torture began.

They beat with cables and then hanged me by my hands from a pipe under the ceiling so that my feet weren’t touching the floor. I was hanging there for about six hours, although it was hard to tell the time. They were beating me, and pouring water on me, and then using electric tasers.

For the night, they put me into a cell, about three-by-three meters, along with some 25 other detainees. We were all squeezed together. Next morning, they brought me in for another interrogation. This time, they “folded” me, pushed my legs and head into a tire, flipped me on my back, and started flogging the soles of my feet.[106]

Another witness, Basel (not his real name), gave similar accounts of torture he experienced at the Military Intelligence detention facility in Homs:

When I did not answer all their questions during interrogation, they took me to a torture room. My eyes were blindfolded, but I recall going five steps down. They used handcuffs to tie one of my arms to a pipe under the ceiling and left me hanging there, with my feet barely touching the ground. They left me there for two or three hours. They did this over eight days. There were usually five or six detainees tortured that way at any given moment. I could not see them but I could hear their screams. Sometimes, they would also beat me while hanging. My wrist, arm, and shoulder would hurt so much, that I tried at one point to break my arm so that they would have to take me down.[107]

Basel said that after three days of torture, he could no longer bend his legs and his feet were worryingly swollen. The security forces called for a doctor to give him an anti-inflammatory injection. Basel said that he met two detainees who had had nails pulled out and many who had been electrocuted with electric batons.

Another witness, Omar (not his real name), told Human Rights Watch that some detainees were subjected to particularly brutal treatment:

Four days after we were brought to the Military Intelligence base in Homs, the guards took one the detainees, Abdul Halim [name changed] for interrogation. When they returned him to the cell two hours later, he was half-dead. No matter where you touched his body, he screamed in pain. He had black-and-red marks from electric shocks on his hands, legs, and back. They pulled out nails on his hands. The interrogators also used an electric drill on him – hehad holes from the drill on his hands, hips, knees, and feet. He was bleeding profusely. We asked the guard to give him medical assistance, but they refused.

I was moved to another facility shortly thereafter, and I don’t know whether he survived.[108]

Interrogators did not spare those detainees who were wounded during the arrest and thus particularly vulnerable. One former detainee, Wassim (not his real name), sustained a bayonet wound on his back during arrest. He said that he and other wounded detainees had been subjected to various forms of torture in the military hospital in Homs:

After the nurses stitched my wound without applying any anesthesia, the guards took me into a detention facility in the hospital, threw me on the ground, and started beating me. I told them I was injured and cried, asking them not to beat me, but they didn’t stop. They put me on a bed, and when they removed my blindfold, I saw five other detainees, all with gunshot wounds, on the beds around me.

Two hours later one of the guards came in, and beat me again. Then I saw him heating up a metal rod on a gas heater. I was terrified that he would use it on me, but instead he walked up to another man – hewas naked, and his hands were cuffed. The guard put the red-hot metal rod to his testicles. The man screamed, saying he was innocent. The guard then beat him with the same rod, and then heated it up again, this time burning his feet.[109]

Detainees arrested in Tal Kalakh said that before delivering them to the detention facility, security forces brought them to a nearby Alawite village where they encouraged residents to beat and humiliate the detainees. Wael told Human Rights Watch: