"The Silent Treatment"

Fleeing Iraq, Surviving in Jordan

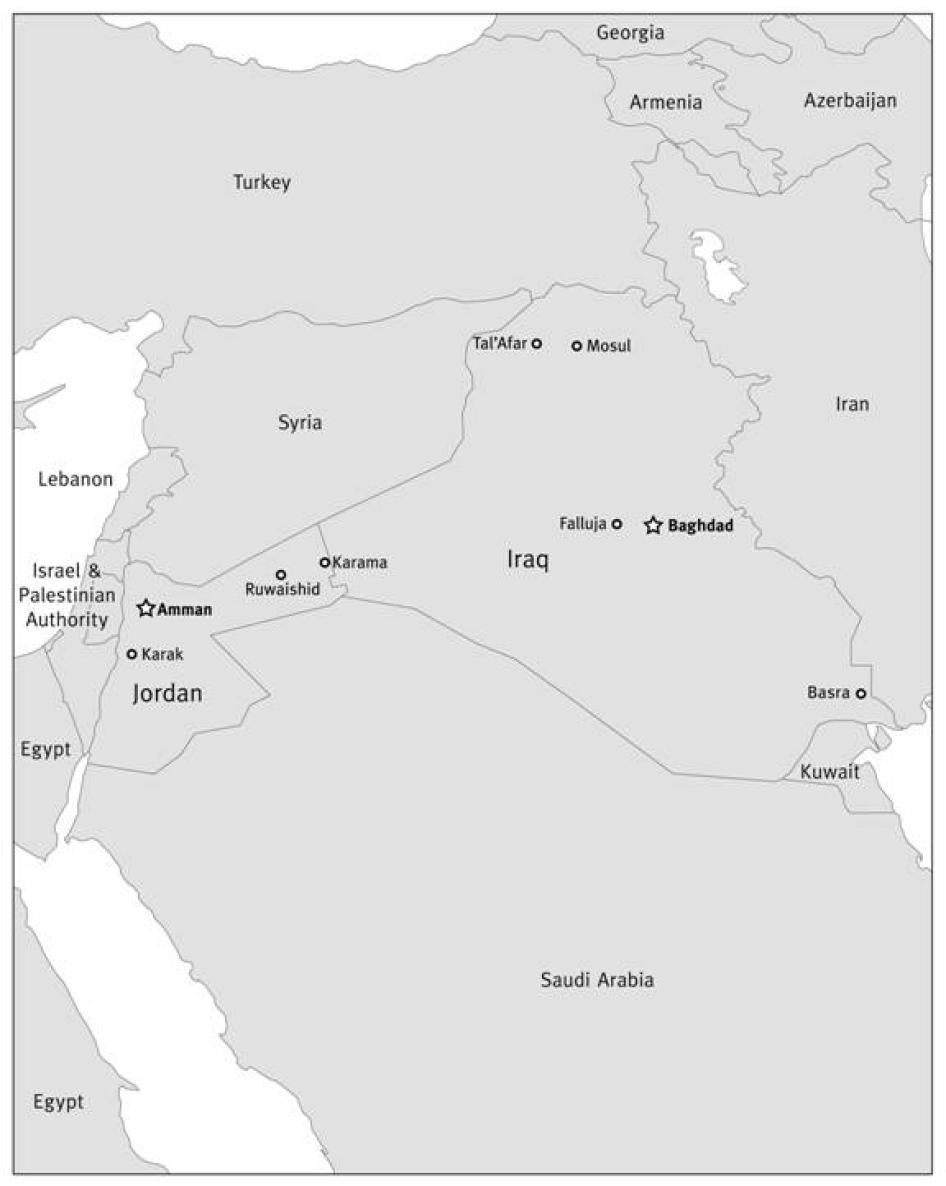

I. Map

Jordan and Iraq. 2006 John Emerson

II. Executive Summary

Since the start of the 2003 war in Iraq, hundreds of thousands of Iraqis have fled their country, seeking refuge in bordering countries. About one million are split evenly between Jordan and Syria, while Saudi Arabia and Kuwait have barred all Iraqis from entering and few are known to have sought refuge in Iran or Turkey. Countries within the region, as well as the larger international community, have largely ignored the presence and the needs of Iraqi refugees. This report focuses on the status and experience of Iraqis in Jordan not because Jordan has had a unique record in mistreating them; on the contrary, it and Syria have been the most generous in allowing Iraqis to enter and remain. Rather, Jordan serves as a case study to highlight-and to seek to remedy-the plight of Iraqi refugees, a shared responsibility of Jordan, neighboring countries, and the international community.

Although it has historically been among the most welcoming countries in the world toward refugees, the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan today ignores the existence of hundreds of thousands of Iraqi refugees, does not address their needs for protection, and has not asked for international assistance on their behalf. It is a policy that can best be characterized as "the silent treatment."

Human Rights Watch regards the vast majority of Iraqi nationals in Jordan as "de facto refugees"-people who have fled conditions of generalized violence and persecution, who are in need of international protection and who face objective conditions of danger in their country, even if they have not registered asylum claims or had those claims adjudicated and been officially recognized as refugees by either the Government of Jordan or the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). De facto refugees in Jordan come from all walks of life and diverse religious and ethnic backgrounds. Both Sunnis and Shi`a have sought refuge in Jordan, as have non-Muslim minorities. De facto refugees include people who fled during the Saddam Hussein era and who still fear return, as well as people who newly arrive at the border. Some are threatened as collaborators with the Americans, while others are threatened for their alleged associations with the Ba`thist Party that ruled Iraq under Saddam Hussein. They represent people who flee both generalized violence as well as targeted persecution, including ethnic cleansing.

Yet Jordan treats Iraqis fleeing violence inside Iraq as temporary visitors, not refugees. Because Jordan has made renewal of their visas so difficult that most Iraqis quickly lose their legal status, most Iraqis are left to fend for themselves, living in the shadows, fearful, and subject to exploitation. Although UNHCR declared a "temporary protection regime" (TPR), the Jordanian government accurately insists that it never agreed to it. Of greatest concern, Jordan has increasingly subjected Iraqis to deportation or refusal at the border. Given the present level of violence and human rights abuses in Iraq, such returns and rejections appear in many cases to constitute refoulement, the forced return of refugees, a violation of international customary law.

A Jordanian official encapsulated the government's nonexistent Iraqi refugee policy when he told Human Rights Watch that Jordan was not facing a refugee problem, but rather one of "illegal immigration, no different from what the United States faces with Mexicans." This statement consciously ignores the carnage and abuse raging next door that compels Iraqis to seek refuge in Jordan. Most Iraqis are not coming to Jordan to seek economic opportunity, but rather to escape brutality and save their lives.

Palestinian refugees and Iranian Kurdish refugees who fled from Iraq face uniquely difficult situations in Jordan. Both groups lived for decades in Iraq without having integrated into Iraqi society, and found themselves especially vulnerable after the fall of Saddam Hussein. Although UNHCR recognizes the Palestinians and Iranian Kurds as refugees, they are restricted to a remote and desolate place where their lives are, at best, in limbo. A group of Iranian Kurds stranded at the border crossing are on the edge of a war zone, and in actual danger. By contrast, while UNHCR does not formally recognize the de facto Iraqi refugees in Jordan, the government does not restrict their movement or confine them to camps.

In late 2002 and early 2003, as the United States and its allies prepared to invade Iraq, Jordan initially vowed to close its borders to refugees fleeing Iraq. In practice, though, as Iraqis began to seek refuge from the escalating conflict, Jordan allowed them to enter the kingdom on 30-day visas issued at the border-as it had for about a quarter million Iraqis who left Iraq during the Saddam Hussein era to escape repression and the effects of economic sanctions. As it did before the war, Jordanian authorities looked the other way after April 2003 when Iraqis overstayed their visas, demonstrating considerable leniency in enforcing immigration laws.

Jordanian hospitality and tolerance toward Iraqis changed, however, after November 2005, when three Iraqi nationals killed 60 people by setting off bombs in three large hotels in Amman. Since the hotel bombings, Jordanian officials have stepped up immigration enforcement: turning away large numbers of Iraqis seeking entry at the border, making it harder for Iraqis inside Jordan to renew their visas and remain in legal status, and arresting Iraqis for working or residing illegally once they lose their legal right to remain in the country. As a result, Iraqis who manage to enter Jordan quickly lose their legal status and begin accruing fines of 1.5 Jordanian dinars (JD, equal to US$2) for each day that they remain in Jordan after their visas expire. For refugees with nowhere to go and limited sources of income, this quickly adds up to enormous sums that they are unable to pay. If the Jordanian police apprehend Iraqis who cannot pay the accumulated fines for overstaying their visas, the police deport them and deny them re-entry to Jordan for five years.

While Human Rights Watch appreciates Ministry of Interior (MOI) officials' assurances that they act according to humanitarian principles and do not return people to persecution, their approach seems to be based on personal exceptions rather than policy, and in practice has led to abuses, including refoulement, the forced return of refugees. Human Rights Watch research documented cases of refoulement both of Iraqi asylum seekers holding UNHCR cards and of de facto refugees who were not registered with UNHCR but who expressed to the authorities their fear of return. In addition, frequent travelers, such as taxi drivers, report to Human Rights Watch that more Iraqis are turned away at the Jordan-Iraq border since the Amman bombings.

Living illegally in Jordan creates a pervasive climate of anxiety among the Iraqi population. Without work authorization and with depleted savings, many Iraqis become dependent on relatives outside the region to send them money. Others sell their belongings or seek low-paying, under-the-table work. Those who work illegally are prone to accepting exploitative or marginal employment. They are often over-qualified for these menial jobs, but earn less than Jordanians for the same work.

Iraqi children living in Jordan also face substantial barriers to education. Although the government has not clearly and categorically barred foreign children who do not possess residency permits from attending school, its actions and pronouncements have resulted in the denial of primary education for many Iraqi children. The timing and ambiguity of announcements of changes in education policy have sown confusion and uncertainty among Iraqis without residency permits and could be taken as a deliberate attempt to deter them from enrolling their children in school.

Jordan is not a party to the 1951 United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees (Refugee Convention) or the 1967 Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees. It has never developed a domestic refugee law or a procedure for adjudicating asylum claims, and UNHCR hardly fills the gap. In 2003, the UN refugee agency initiated the temporary protection regime in Jordan and the surrounding region. Its purpose was to prevent all Iraqis who registered with the refugee agency from being deported to Iraq, based on temporary conditions of generalized violence in their home country. According to the TPR, UNHCR does not actually process registrants' asylum claims, but rather provides them with "asylum seeker" cards, which are intended to ensure access to territory and temporary protection from deportation, but not to establish a refugee status per se or any rights to permanent residency in Jordan.

Yet UNHCR's temporary protection regime has failed to provide protection to the majority of Iraqis living in Jordan. The agency has registered only 17,000 Iraqis in Jordan under its TPR, and provided them with "asylum seeker" cards. They represent a tiny fraction of the potential refugees in the country who have fled persecution, war, and generalized violence in Iraq. Moreover, even those who have registered receive little protection because Jordan does not accept the temporary protection regime and Jordanian officials refuse to recognize UNHCR-issued asylum-seeker cards (other than to notify UNHCR when card holders have been detained and to provide the agency access to conduct refugee status determinations (RSDs) for such detainees).

In refusing to accept the temporary protection regime, the government of Jordan insists that UNHCR continue to operate according to a 1998 Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) under which the refugee agency is required to adjudicate refugee claims and seek third-country resettlement for recognized refugees. However, UNHCR has suspended processing of almost all newly registered Iraqi asylum seekers both because it lacks the resources to adjudicate the enormous potential number of Iraqi claims in Jordan and because it does not want to engage in a procedure that could result in Iraqis being screened out and returned to Iraq for failure to qualify as refugees according to the narrow persecution standard in the Refugee Convention. Consequently, the refugee agency has only recognized a miniscule number of refugees-22 in 2005. The vast majority of Iraqis have neither registered as asylum seekers nor been recognized as refugees, though many appear to be refugees in need of international protection.

Historically, Jordan has been remarkably open to people from the region fleeing persecution, first Palestinians, now Iraqis. Although Jordan's historical generosity is now undergoing a severe challenge and its attitude appears to be hardening, it still fares well relative to most of its neighbors as one of the more tolerant countries in the region toward refugees. Most governments in the region are intent on preventing the entry of Iraqis and make no effort to regularize the status of Iraqis residing in their countries. UNHCR's efforts to declare a region-wide temporary protection regime for Iraqis fleeing war and persecution have largely fallen on deaf ears. Kuwait and Saudi Arabia bar the entry of most Iraqis and have negligible numbers of Iraqi refugees in their territories. Although Iran and Turkey are somewhat insulated from the problem by the predominant ethnicities and religious persuasions of Iraqi asylum seekers, as well as other buffers that result in fewer arrivals, neither state has made any provision for considering refugee claims that Iraqis might make on their territories.

Syria bears the greatest similarity to Jordan and shares with Jordan the bulk of the burden-hosting an estimated 450,000 Iraqis. Although Syria has generally been tolerant toward Iraqis, its tolerance, like Jordan's, appears to be ebbing, and Syria, like Jordan, has been less than forthright in identifying refugees and asking for help on their behalf. Lebanon, which hosts an estimated 20,000 Iraqis, makes no allowance for refugees, provides no basis to allow them to regularize their status, and regularly detains Iraqis who may well have persecution claims in order to coerce them to "voluntarily" go home. Other countries that host significant numbers of Iraqis, such as Yemen and Egypt, have taken steps to restrict their entry. Generally, Iraqis throughout the Middle East remain unregistered, uncounted, unassisted, and unprotected.

Governments outside the region are also all too willing to look the other way to avoid recognizing the presence of Iraqi refugees in Jordan-and, by implication, acknowledging this dimension of the human costs of the war in Iraq. The United States and the United Kingdom, the two states most heavily committed militarily in Iraq, have paid relatively little attention to the regional human fallout precipitated largely by their military intervention in Iraq. Both states have close ties with Jordan. It should be in their interest to address the Iraqi refugee problem generated by the Iraq war before the massive refugee burden has a destabilizing effect on the region. Since the start of the war in 2003 until the beginning of 2006, the United States took only 12 UNHCR-referred Iraqi refugees from Jordan and the United Kingdom took none.

Jordan has insisted that resettlement to third countries is the only option for refugees on its territory whom UNHCR has recognized. It is also overwhelmingly the preference voiced by Iraqi (as well as Palestinian and Iranian Kurdish) refugees interviewed by Human Rights Watch. Given the very large number of people in need of protection in Jordan, however, resettlement is not a viable option for more than a relatively small number of the refugees in need of protection. Therefore another approach is needed, and the Jordanian government and the international community need to be convinced to subscribe to a more realistic, fair, and effective protection regime.

Although unlikely under present circumstances, Jordan should accede to the Refugee Convention and Protocol, establish domestic refugee law and infrastructure, and take responsibility for protecting refugees on its territory and at its borders. At a minimum, the government must meet its international customary law obligations not to return Iraqis to persecution or torture. This principle-nonrefoulement-applies to asylum seekers, who, de facto, may be refugees, but who have not had the opportunity to be officially recognized as such. The principle of nonrefoulement also applies to people seeking asylum at the border whose rejection would likely subject them to persecution or other serious harm.

Whether or not it accedes to the Refugee Convention and incorporates the provisions of the Convention into domestic law, the Jordanian government should institute its own temporary protection regime in response to the ongoing armed conflict and generalized violence in Iraq and the danger of return. Jordan's Law on Residence and Foreigners' Affairs gives the minister of interior the discretion to waive normal immigration requirements "on account of special considerations connected with international or humanitarian courtesy or of the right to political asylum." The law's recognition of the right to seek asylum and its allowance for international and humanitarian considerations provides wide latitude for the minister of interior to exercise discretion to protect Iraqis and other foreigners fleeing war and persecution. This statutory provision provides clear authority in domestic law to embark on a temporary protection regime, even in the absence of a refugee law.

Such an ad hoc TPR should include both a bar to deporting Iraqis who register with the government for at least six-month intervals and work authorization for those who have registered for temporary protection. The government should announce an exemption from fines for overstaying visas for Iraqis who register for the TPR. Government-issued temporary protection cards should provide both renewable, time-limited residence permission and work authorization. Iraqi temporary-protection beneficiaries should have equal access to health care and education as Jordanian nationals. With the assistance of UNHCR and the international community, the government should also provide temporary accommodation to Iraqis seeking asylum at the border.

The purpose of this paper is not so much to highlight the failures of the Jordanian government or to suggest that Jordan is uniquely responsible for a refugee problem that it faces largely as a result of geographical and historical happenstance. Jordan needs to institute a more responsible refugee policy, but it should not be expected to institute such a policy or bear the burden of such a policy alone. Its regional neighbors should join in providing temporary refuge, and the wider international community should provide prompt and generous support to enable Jordan to keep its doors open and to provide first asylum.

This level of international support is unlikely to be forthcoming, however, if Jordan does not recognize the refugee problem and ask for international help to address it. Yet the government studiously ignores both the scale of the problem (somewhere between a half million and a million people) and its character (as predominantly a refugee flow, not mere economic migration) to avoid acknowledging its responsibility to assist and protect.

One thing is certain: "the silent treatment" is not working and cannot continue. The government cannot go on pretending that huge numbers of Iraqi refugees are not living in Jordan, and assume that UNHCR can handle the problem. The scale of the refugee problem in Jordan is well beyond the resources of the UNHCR office in Amman, as currently constituted. The refugee reality in Jordan dictates a government response that cannot be shirked off onto UNHCR's narrow shoulders.

If Jordan does not follow Human Rights Watch's recommendation to institute its own temporary protection regime, the government must at least allow UNHCR broad authority to recognize refugees without guarantees that it will be able to find resettlement places for them. Donor governments, led by the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Gulf States, must provide the resources to give UNHCR the capacity to fulfill this role.

Minimally, Jordan should admit asylum seekers and tolerate the presence of refugees broadly recognized by UNHCR even if it is not able to provide them with a durable solution. It should refrain from rejecting them at the border or deporting them. It should allow them to work and provide them the basic necessities of life required by international human rights standards, including nondiscriminatory access to education and health care. Finally, Jordan needs to speak up and call upon the international community for help to share the enormous refugee burden it tries to ignore by remaining silent. Pretending that the burden does not exist will neither make the problem go away nor absolve Jordan of its responsibilities to protect and assist.

Refugee Terminology

Human Rights Watch regards the vast majority of Iraqi nationals, who have fled to Jordan to seek protection, as "de facto refugees." Human Rights Watch chooses this term because hundreds of thousands of Iraqis in Jordan have fled conditions of generalized violence and persecution, and face objective conditions of danger in their country of origin, even if they have not registered asylum claims or had those claims adjudicated and been officially recognized by UNHCR as de jure refugees.

The absence of a legal framework for refugee-status recognition-or lack of access to procedures-does not obviate the reality of being a refugee. As UNHCR's Handbook on Procedures and Criteria for Determining Refugee Status notes:

A person is a refugee within the meaning of the 1951 Convention as soon as he fulfills the criteria contained in the definition. This would necessarily occur prior to the time at which his refugee status is formally determined. Recognition of his refugee status does not therefore make him a refugee but declares him to be one. He does not become a refugee because of recognition, but is recognized because he is a refugee.[1]

The term "asylum seeker" refers to a person who claims to be a refugee but whose claim has not been determined. UNHCR-Amman stretches the meaning of the term asylum seeker when it uses this term to designate Iraqis who the office has registered for temporary protection because UNHCR, with a few exceptions, is not actually adjudicating their refugee claims while its temporary protection regime is in place.[2] The asylum-seeker card issued by UNHCR carries few actual benefits; the government does not recognize the card as conferring permission to reside or work in Jordan, but has formally agreed to inform UNHCR when it apprehends asylum-seeker card holders pending their deportation to give UNHCR the opportunity to examine their refugee claims.

The 1951 Refugee Convention refugee definition is based on a "well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion."[3] The 1998 Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) under which UNHCR operates in Jordan defines refugees according to the Refugee Convention and assigns UNHCR the function of adjudicating refugee claims. In the MOU, the Jordanian government agrees to abide by the principle of nonrefoulement and UNHCR agrees to endeavor to find a durable solution-voluntary repatriation or third-country resettlement-within six months of recognizing the individual as a refugee.

UNHCR-Amman's caseload of recognized refugees in 2006 includes about 700 Iraqis, most of whom it recognized before 2003 when Saddam Hussein was still in power.[4] Since 2003, UNHCR-Amman has suspended refugee status determinations for all but a few cases as part of its temporary protection regime. Therefore, either because the vast majority of Iraqis in Jordan are unaware of UNHCR or of the concept of refugee rights, or because they see little benefit to registering asylum claims with the refugee agency, relatively few have registered as asylum seekers and far fewer have been recognized as refugees. Many Iraqis in Jordan appear, however-prima facie-to be refugees in need of international protection, based on dangerous or threatening conditions in Iraq.

Although the Refugee Convention refugee definition is based on a narrow "well-founded fear of being persecuted" standard, the international community is also progressively recognizing the need for international protection for people fleeing war and serious civil disturbances, who may not qualify under the Convention, but who nevertheless would face the risk of serious harm if returned.[5] Human Rights Watch chooses the term "de facto refugees," therefore, to capture both persons who would qualify under the 1951 Refugee Convention if they had access to procedures to recognize them as refugees under that instrument, as well as persons who fear serious threats to their lives and freedom because of indiscriminate violence and ongoing armed conflict. In choosing this term, we also recognize that there are Iraqi nationals in Jordan who do not fear return, or who would otherwise be excluded from refugee status,[6] and who therefore should not be considered as refugees.

Recommendations

To the Jordanian Government

- Institute a temporary protection regime (TPR) based on the situation of ongoing armed conflict and generalized violence in Iraq, possibly by invoking the discretion given to the minister of interior in the Law on Residence and Foreigners' Affairs to waive normal immigration requirements "on account of special considerations connected with international or humanitarian courtesy or of the right to political asylum."

- At a minimum, recognize the TPR initiated by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. A TPR should have the following components:

- Temporarily suspend all deportations of Iraqis who register with the government and renew their TPR registrations for at least six-month intervals.

- Admit at least temporarily Iraqi and Palestinian asylum seekers who present claims at the border pending a determination of their claims.

- Provide work authorization for TPR registrants.

- Exempt from fines Iraqis who have overstayed their visas when they register for the TPR.

- Ensure the right of all children residing in Jordan, regardless of residency status, to free and compulsory primary education, consistent with Jordan's obligations under the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. To that end, immediately and unambiguously announce that all children will be welcome in public schools regardless of immigration status, and take steps to recognize and accredit otherwise qualifying private schools that cater to Iraqi students.

- Accede to the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol.

- In consultation with UNHCR, establish a domestic refugee law to enable Jordanian authorities to determine refugee claims and provide protection to refugees seeking asylum in Jordan-at its most basic level, protection from refoulement.

- Survey the population of Iraqis in Jordan to identify their numbers and the scope of their needs.

- Ask for financial and technical assistance from the international community to help meet the challenge to Jordan of providing temporary asylum to Iraqi refugees, including for other countries to help Jordan by resettling Iraqi refugees in need of durable solutions.

To the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

- Conduct a survey of Iraqi nationals in Jordan comparable to the survey conducted by the Danish Refugee Council on Iraqis in Lebanon[7] or the joint UNHCR, United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), and World Food Program (WFP) assessment of Iraqi refugees in Syria.[8]

- Intervene-at least to assess the refugee claim-when any detained Iraqi (or other foreigner) at risk of deportation makes a refugee claim. Do not limit interventions on behalf of asylum-seeking detainees to those who have previously registered with UNHCR.

- If the current arrangement of issuing asylum-seeker cards for purposes of temporary protection is maintained, then provide such cards to previously rejected asylum seekers whose cases were closed, who may no longer be candidates for refugee recognition, but who may nevertheless need temporary protection based on generalized conditions of violence in Iraq.

- When conducting refugee status determinations, ensure that UNHCR Executive Committee (ExCom) Conclusion 103 on the Provision of International Protection including through Complementary Forms of Protection is being followed so that protection is extended to war refugees and not only refugees who fall within the 1951 Refugee Convention definition.[9]

- Establish a UNHCR border-monitoring presence and have at least one protection officer dedicated to monitoring border protection.

- Explore more creative solutions to resolve the situation of the Iranian Kurds in the no-man's land (NML) at the Iraq-Jordan border. Confidence-building measures could include taking camp leaders and residents for "go and see visits" to the Kawa camp in the Qoshtapa area of northern Iraq to see firsthand the place UNHCR says they would be safe, and where other Iranian Kurdish refugees are currently living. Or, explore the possibility of establishing a program of eligibility for NML Iranian Kurds with family links or ongoing protection problems in northern Iraq to seek resettlement opportunities to Sweden, New Zealand, and Ireland (the countries that have resettled the most Iranian Kurds from al-Ruwaishid) after their return to northern Iraq.

To the United States

- Work through UNHCR and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) to provide quick and meaningful technical and financial support to protect and assist Iraqi and Palestinian refugees from Iraq in Jordan and elsewhere in the region.

- Institute a significant refugee resettlement program for Iraqi refugees of special humanitarian concern to the United States, at least including persecuted religious minorities and people persecuted or threatened with persecution on account of their imputed or actual association with the U.S. government or private American organizations. Create a Priority Two refugee-processing category to expedite the resettlement of some or all of these groups, and expand eligibility for family members in the United States to petition for Iraqi refugee relatives to reunite with them.[10] Respond positively and quickly to UNHCR referrals to resettle Iraqi refugees who do not fall into the category groups specified above.

- Resettle to the United States on a humanitarian basis based on past persecution, Iraqi refugees recognized by UNHCR during the Saddam Hussein era and referred to the United States for resettlement, who were not resettled to the United States as a result of the U.S. moratorium on resettlement of Iraqis after September 11, 2001, and who have been living in limbo since that time. Doing so will not only serve an immediate humanitarian need, but will also help to expedite the processing of "new caseload" Iraqi refugees for U.S. resettlement.

- Provide leadership to other donor governments and at UNHCR's Executive Committee regarding the need for significantly greater emergency funding for refugee needs in Jordan and elsewhere in the region arising from the humanitarian crisis in Iraq.

To the United Kingdom

- In light of the United Kingdom's intricate historical and present involvement with Jordan and as the United States' major coalition partner in Iraq, institute a significant refugee resettlement program for Iraqi refugees, particularly those with links to the United Kingdom.

- Provide generous financial assistance to Iraqi refugees in the region through UNHCR and NGOs.

To Ireland, New Zealand, and Sweden

- In light of having resettled the bulk of the Iranian Kurds from al-Ruwaishid, offer to consider for resettlement those of the 192 Iranian Kurds still in the no-man's land who first voluntarily move to northern Iraq, and who after moving there can show ongoing protection needs, demonstrate meaningful barriers to local integration, or establish family links to Sweden, New Zealand, or Ireland.

To Egypt, Iran, Kuwait, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Turkey, and Yemen

- Institute a temporary protection regime based on the situation of ongoing armed conflict and generalized violence in Iraq, or, at the least, recognize the TPR initiated by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Depending on the resources of the particular country and on the refugee burden it bears, join with Jordan in seeking financial and technical assistance, as needed, from the international community to meet the challenge of providing temporary asylum to Iraqi refugees, including through resettling Iraqi refugees in need of durable solutions to third countries.

- Kuwait, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, and Syria should accede to the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol, and Turkey should drop its geographical limitation to the Convention and Protocol. In consultation with UNHCR, all countries in the region should establish domestic refugee laws and build infrastructures to enable government authorities to determine refugee claims and provide protection to refugees.

- Syria should admit the 200 Palestinian refugees stranded at the Syria-Iraq border and reopen the Syrian border to Palestinian refugees from Iraq, consistent with Syria's admission on May 9, 2006, of the Palestinian refugees stranded at the Jordan-Iraq border.

- Lebanon should discontinue its practice of detaining Iraqis indefinitely for illegal entry or stay as a means of coercing them to opt for "voluntary" return to Iraq.

To the European Union (and European Union member states), the Arab League (and its member states, including in particular Kuwait and Saudi Arabia), Iran, Turkey, Israel and Other Donor Governments

- Contribute quickly and generously both bilaterally and through UNHCR to meet the humanitarian and protection needs of Iraqi and Palestinian refugees from Iraq in Jordan and elsewhere in the region.

- In a spirit of international humanitarian solidarity, governments inside and outside the region should share the human burden by providing both temporary and permanent asylum, as appropriate, to Iraqi and Palestinian refugees fleeing war and persecution in Iraq in order to prevent refoulement and maintain at least temporary asylum in Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, and other countries in the region that may struggle to cope with the influx of refugees from Iraq.

To the UNHCR Executive Committee

- Recognize that the refugee emergency in Jordan and elsewhere in the region is of a major scale and that the numbers of Iraqi refugees and their needs are substantially greater than has heretofore been acknowledged.

- Re-designate the Iraq situation as a continuing humanitarian emergency that requires supplementary budget funding.

- Base funding of UNHCR operations in Jordan and Syria on a real needs-based assessment rather than on anticipated resources.

III. Background

Today, Jordan has the highest ratio of refugees to total population of any country in the world.[11] Palestinian refugees registered by the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) comprise about 30 percent of Jordan's population of 5.8 million people.[12] In addition to this long-standing refugee population who fled or were expelled from Israel/Occupied Palestinian Territories from the west, one of the largest new influxes of "de facto refugees" in recent years-now numbering at least 500,000 and possibly as many as one million-has fled from Jordan's neighbor to the east, Iraq.[13]

Iraq and Jordan share historical ties. Iraq's monarch, before the country became a republic in 1958, was a brother of Jordan's king, both of them descendents of the Hashemite family of Saudi Arabia.[14]Iraq was also Jordan's most important trading partner,[15] and, as a comparatively stable country, has long offered safety and relative freedom to Iraqis fleeing political upheaval and repression.[16]

The numbers of Iraqis fleeing to Jordan began to rise from a few thousand to a few hundred thousand in the 1990s, when Saddam Hussein brutally repressed Shi`a Iraqis, Kurds (though few Iraqi Kurds fled to Jordan), and any others who dissented from his rule. Another cause for flight was the accelerating economic decline and dire humanitarian situation in Iraq, caused in part by a comprehensive sanctions regime placed on Iraq by the UN Security Council. By the start of the war in April 2003, Jordan was estimated to host between 250,000 and 300,000 refugees.[17] The 2003 war and its continuing aftermath brought new waves of Iraqis to Jordan, at least doubling their number by 2006. Amman's population is estimated to have grown by as much as one-third since the war began.[18]

Until November 2005 the Jordanian government and Jordanian law enforcement officials had demonstrated considerable leniency in enforcing immigration laws, usually deporting Iraqis only if they violated other laws. Jordanian hospitality and tolerance toward Iraqis came under particular stress, however, when three Iraqis killed 60 people by setting off bombs in three large hotels in Amman in November 2005.

Although Iraqi nationals in Jordan interviewed by Human Rights Watch rarely alleged being personally harassed or abused in the aftermath of those bombings, resentment is rising and the government is cracking down on young Iraqis staying and working illegally.[19] Attitudes among Jordanians also appear to be hardening, and Iraqis appear increasingly at risk of being scapegoated for a wide variety of social problems. An observer wrote:

When I ask Jordanians about Iraqis in their midst, they voice sentiments like these: "The Iraqis make it harder for us because prices are going up"; "Youth who want to get married say they can't find apartments because the prices are too high"; "Iraqis are taking all of the jobs"; "Employers favor them because they can have them for less pay"; "We had a safe, secure Jordan, but crime is rising. Now there is prostitution, robbery, and theft."[20]

UNHCR's tally of detained asylum seekers jumped from a monthly average of 16 cases to 40 cases in November 2005, the month of the hotel bombings.[21] After the bombings, Jordan appears to have increasingly begun deporting visa "overstayers" back to Iraq and now denies entry to increasing numbers of Iraqis at the border, according to unofficial accounts.[22] Taxi drivers on the Baghdad-Amman route and Iraqis who had made the journey to Amman told Human Rights Watch that Jordanian officials are now turning back the majority of Iraqis seeking entry at the land border at al-Karama, the only land crossing between Iraq and Jordan.[23]

IV. Refoulement-Rejections at the Border and Deportations

Jordan's Nonrefoulement Obligations

Jordan acceded to the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (Convention against Torture) on November 13, 1991, and is bound under Article 3 of that instrument not to return or expel any persons to states where they would be in danger of being tortured.[24]Jordan is not a party to the 1951 Refugee Convention or its 1967 Protocol, but is nevertheless bound by customary international law not to return refugees to a place where their lives or freedom would be threatened. UNHCR's Executive Committee-of which Jordan is a member[25]-adopted Conclusion 25 in 1982, which declared that "the principle of nonrefoulementwas progressively acquiring the character of a peremptory rule of international law."[26]

The UN General Assembly reinforced the international consensus that the nonrefoulement obligation adheres to all states, not just signatories to the Refugee Convention, when it adopted Resolution 51/75 on August 12, 1997, which:

[c]alls upon all States to uphold asylum as an indispensable instrument for international protection of refugees and to respect scrupulously the fundamental principle of nonrefoulement, which is not subject to derogation.[27]

On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Refugee Convention in 2001, the Declaration of States Parties to the 1951 Convention and/or its 1967 Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees acknowledged "the continuing relevance and resilience of this international regime of rights and principles, including at its core the principle of nonrefoulement, whose applicability is embedded in customary international law."[28] Later that year, the UN General Assembly welcomed the Declaration.[29]

Jordan has explicitly pledged to uphold its nonrefoulement obligations on several formal occasions. In the Memorandum of Understanding Jordan signed with UNHCR in April 1998 it agreed:

In order to safeguard the asylum institution in Jordan and to enable UNHCR to act within its mandateit was agreedthat the principle of non-refoulement should be respected that no refugee seeking asylum in Jordan will be returned to a country where his life or freedom could be threatened because of his race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion.[30]

When Jordan presented its candidacy to the UN Human Rights Council on April 20, 2006, it formally provided the United Nations with its pledges and commitments for the promotion and protection of human rights. It said:

Over the last decades, the country has given shelter and protection to many waves of refugees; Jordan, as a long-standing host country, reiterates its commitment to fulfilling its obligations in accordance with the principles of international refugee law including those which are peremptory as well as international human rights law.[31]

Jordan's statements formally recognize that refugee protection is an obligation, and that it is committed to fulfilling this obligation, which includes abiding by peremptory norms (that is, customary law)-the most fundamental of which for refugees is the principle of nonrefoulement. Nonetheless, Jordan violated this principle when it returned three UNHCR refugee-card holders to Iraq in 2005, as well as in many other cases (see below).[32]

Nonrefoulement obligation adheres to de facto refugees and at the border

Because refugee status is declaratory,[33] the fundamental principles of refugee protection apply equally to de facto refugees who have not been formally recognized as de jure refugees. UNHCR's Executive Committee reiterated that the nonrefoulement obligation equally protects de facto refugees in 1996 with Conclusion 79, which reaffirmed the principle of nonrefoulement as prohibiting the expulsion and return of refugees "whether or not they have formally been granted refugee status."[34]

The principle of nonrefoulement as a customary norm of international law applies not only to de jure and de facto refugees within the territory of a state, but also to rejection of de jure and de facto refugees at the frontiers. In its October 2004 meeting, UNHCR's ExCom issued Conclusion 99, which calls on States to ensure "full respect for the fundamental principle of nonrefoulement, including non-rejection at frontiers without access to fair and effective procedures for determining status and protection needs."[35] (Emphasis added.) This Conclusion not only explicitly notes that the nonrefoulement obligation applies to rejection at borders, but also calls for fair and effective procedures for determining status and protection needs, which are also lacking for arrivals at Jordan's borders and ports of entry.

Conclusion 99 was the last in a long series of ExCom conclusions, starting with ExCom Conclusion 6 in 1977, which "[r]eaffirms the fundamental importance of the observance of the principle of nonrefoulement-both at the border and within the territory of a State"[36] (Emphasis added.) ExCom Conclusion 22 of 1981 on the Protection of Asylum Seekers in Situations of Large-scale Influx-such as that from Iraq-says:

In situations of large-scale influx, asylum seekers should be admitted to the State in which they first seek refuge and if that State is unable to admit them on a durable basis, it should always admit them at least on a temporary basis...They should be admitted without any discrimination as to race, religion, political opinion, nationality, country of origin or physical incapacity. In all cases the fundamental principle of nonrefoulement-including non-rejection at the frontier-must be scrupulously observed.[37] (Emphasis added.)

The practical consequence of the application of the principle of nonrefoulement at the border requires that Jordan allow asylum seekers fleeing widespread human rights abuses and generalized violence (even where the influx is significant) to enter the country, at least temporarily, to be screened for refugee status, so as not to return them to persecution.

Accounts gathered by Human Rights Watch strongly suggest that many Iraqis-perhaps most-are being turned away at the border without giving them any opportunity to make refugee claims, possibly returning them to persecution. By rejecting asylum seekers at the border, Jordan breaches this international obligation.

International refugee law does not formally provide an asylum seeker (a person claiming to be a refugee) the right to enter. The refoulement prohibition, however, provides little latitude when asylum seekers appear at a land border. The conundrum of a lack of a formal right to enter combined with the prohibition against returning asylum seekers (who may, in fact, be refugees) to persecution has bedeviled many governments-Jordan is not alone in confronting the contradiction between its sovereign prerogative of who may enter and its obligation not to return refugees to persecution.

An April 15, 2003, Letter of Understanding between UNHCR and the Jordanian government sought to solve precisely this dilemma. The two parties agreed "to provide for safe facilities for the temporary protection of beneficiaries," while also agreeing that "the provision of temporary protection, pending a longer-term solution, does not include the possibility of local integration, assimilation or permanent residency in the territory of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan."[38] As a result of this agreement, the Jordanian government agreed to erect the Ruwaishid refugee camp close to the border but within Jordanian territory in April 2003.[39]

International refugee law frowns upon any restrictions placed on the movements of refugees within countries of asylum. However, governments can justify some exceptions to the right of free movement for refugees on strictly necessary national security and other grounds.[40] The continuing use or expansion of al-Ruwaishid camp with restrictions to refugees' rights of movement would be one option, if Jordan could show how their movement would endanger its national security. While restricting refugees to camps is far from a desirable solution, it is preferable to pushing Iraqi asylum seekers back at the border.

Rejection at the Border

The road from Baghdad to Amman is highly dangerous. From Ramadi, about 100 kilometers west of Baghdad, there is only one road to the border, making those traveling through the desert toward Jordan an easy target for highway robbers and militants. Baghdad-Amman taxi drivers showed Human Rights Watch bullet holes in the heavy, oversized sport utility vehicles that are their preferred taxis. A driver described the route:

There are a lot of armed groups who steal, and kill people. There is a big division between Shi`a and Sunni now. If the armed group is Shi`a, they kill Sunnis, and vice versa. Two weeks ago, some people in a BMW, with weapons, stopped my car. They took us out of the car and walked us five kilometers into the desert. They stole all of the money of the passengers. They also took me into the desert. They only took our money and then went away, so we walked back to the car. There are thieves, but then there is the mujahideen [as the Iraqi insurgents are called]. The mujahideen, if they know any of your passengers are foreigners, they will take them and they will never be seen again. [41]

Another driver told Human Rights Watch a similar story of being robbed, and how one of his passengers was kidnapped and held for ransom. He also compared the different tactics highway robbers and insurgents use:

The mujahideen stop us on the road and ask us if we have any foreigners, police, or National Guards. They especially want Americans. The danger of the mujahideen is less than from the thieves. But if they discover police or National Guard in my car, and I didn't inform them, they will kill us both.[42]

After surviving the perilous journey from Baghdad, Iraqis face the even harder, though less dangerous, task of gaining entry to Jordan. Since the November 2005 hotel bombings, Jordan appears to be denying entry to increasing numbers of Iraqis. In interviews, taxi drivers and recent arrivals said that Jordanian border authorities are now turning back the majority of Iraqis they had witnessed seeking entry to Jordan. A taxi driver who has been plying the Baghdad-Amman route for the past six years observed, "Under Saddam, the Jordanians let all Iraqis pass, even those with fake passports. No one was turned back. Now, it is worse and worse from day to day, especially after the explosions in Amman."[43]

Another taxi driver said:

We have problems at the Karama border, on the Jordanian part of the border. They don't give us any specific reason why they turn people back; it just depends on their mood. I transport about 25 people from Baghdad to Amman a month, but on average only five people will be allowed to enter. The others will get a stamp in their passport saying that they were returned, and then are sent back to Baghdad.[44]

Other taxi drivers confirmed that some Iraqis' passports are stamped with a red stamp when they are refused entry at the border. The same taxi driver said that people who try to return to the border who have had their passports stamped are treated badly. "Sometimes they even hit them, especially the mukhabarat [intelligence] people."[45]

A Washington Post report noted that Jordanian officials reject Iraqis not only at the Karama crossing, the main entry point overland from Iraq, but at every port of entry:

Jordanian border police are turning away hundreds of Iraqi vehicles daily at the Karama border crossing, often without explanation, creating a huge parking lot of frustrated travelers in the Iraqi desert. At QueenAliaInternationalAirport, just south of Jordan's capital, Amman, Iraqi passengers are ushered into a room and interrogated before being allowed to enter the country. And some Iraqis who used to be able to get 30-day visas to Jordan are now being allowed just to stay a few days at a time.[46]

The Washington Post went on to cite the Jordanian government's spokesman, Nasir Judah, as confirming that Jordan "had imposed new border restrictions on January 2, 2006 that prohibit vehicles with Iraqi license plates from entering the country."[47]e Enhanced security concerns likely account for some of the rejections and contribute to the long delays of 10 hours or more at the border crossing. A businessman from Falluja who travels frequently to Amman told Human Rights Watch, "The last time, the Jordanians searched my car and tested my hands for explosive powder. They brought a dog to search us."[48]

The taxi drivers and other travelers interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that border guards' decisions regarding whom to admit or reject appear to be arbitrary, but that they turn away young men and poor people more often than others. They said the guards are more likely to admit people in need of medical care with proven appointments in Amman. Taxi drivers said that border officials are sometimes rough and rude with Iraqis but that it is impossible to get in by a bribe. One said, "At the Jordanian border, it is completely random whether they let you through. It depends on the face of the person who wants to come in and the mood of the officer."[49]

Ministry of Interior officials in Amman denied that there was anything arbitrary in border rejections. Officials told Human Rights Watch that border guards turn away people if they have false passports or appear to be part of smuggling operations. The MOI secretary general said that most Iraqis trying to enter have forged passports.[50]

Although Human Rights Watch collected anecdotal accounts indicating that some Iraqis continue to use false passports, there are also large numbers of Iraqis traveling with valid passports. During a ten-month period between July 2005 and April 2006, the present Iraqi government issued passports to 1.85 million Iraqis.[51] Although Iraqi refugees report endemic corruption in the Iraqi government's passport-issuing authority, so that even a government-issued passport does not necessarily serve as a legitimate identification document, people fleeing persecution today have less need to use fraudulent documents than in the Ba`thist era, when the government more strictly controlled passport issuance. In any case, asylum seekers have a right to seek asylum even if they do not have proper travel documents, and should not be rejected at the border.[52]

Arrests and Deportations of Iraqi Nationals

In Jordan, special police affiliated with the Ministry of Labor enforce immigration laws in the workplace while the Department of Residence and Borders in the Ministry of Interior enforces immigration laws elsewhere.[53] Arrest, however, is often a matter of chance. An Iraqi Shi`a woman, who works for one of the international NGOs that provide services for Iraqis, said:

In Amman, the Wafidin [migrants' police] roam the streets and carry out arrests. They wear civilian clothes. They make 'mercy' exceptions; if someone in the police or other ministry knows or likes you, you can avoid arrest or get out once arrested. The police know who to arrest by their faces and rarely go after well-dressed people.[54]

Although those slated for deportation have a right under Jordanian law to appeal an administrative order of deportation within 60 days, in practice deportation orders are rarely appealed.[55] MOI officials say that they allow any Iraqi facing deportation to go to Syria or Yemen, which do not require visas from Iraqis, and that most Iraqis in that situation exercise this option rather than go back to Iraq.[56]

Deportation procedures for Iraqis are swift. Iraqis interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that the police authorities wait until they have enough Iraqi overstayers to fill a bus. They said that a bus of deportees travels from Amman to the land border nearly every day since the hotel bombings,[57] an observation confirmed by a diplomatic source and a legal service provider.[58]

Jordanian authorities hold illegal Iraqi overstayers from a few days up to a week in deportation centers, such as Gwesmah in Jabal Habib, or in Markaz al-`Asima, after apprehending them. Gwesmah holds only about a dozen people at a time, according to an employee of the government-appointed NationalCenter for Human Rights, who said that the place was clean and that the kind and amount of food there appeared sufficient: "There were no problems there, except that they were being deported."[59] Iraqis confirmed to Human Rights Watch that police usually escort detainees to their apartments to gather their possessions before deportation.

Jordanian officials exercise a high degree of discretion when deporting Iraqis; this results in highly inconsistent practices. For example, Jordanian officials put different color stamps in deportees' passports, each meant to indicate a different time limit on re-entry, with no explanation and no discernable connection between the color of the stamp and the duration of the bar on re-entry. Those who receive a red, triangular stamp in their passport are barred from re-entry.[60] Some Iraqis said border guards told them this stamp means a lifetime exclusion, but others say it signifies a bar for five years. Authorities allow some deportees to pay the accrued fines equivalent to US$2 per day and avoid deportation. They allow others to pay the fines and avoid the red exclusion stamps when they are deported, theoretically allowing them the opportunity to re-enter the country.

Iraqi de jure and de facto refugees in Jordan fall into four categories:

1.UNHCR-recognized refugees;

2.Asylum seeker card holders under UNHCR's temporary protection regime;

3.Persons UNHCR rejected as refugees prior to 2003, but whose need for at least temporary protection may have changed because of the war; and

4.Persons who have not approached UNHCR, but who fled persecution or generalized violence.

Although circumstances among these categories vary, as outlined below, they all lack a secure legal status in Jordan, live on the margins, and fear being forcibly returned to Iraq.

UNHCR-recognized refugees

UNHCR-recognized refugees do not have any particular status under Jordanian law and in particular do not acquire rights, even temporarily, of residency or the right to work. Instead they are supposed to await resettlement in a third country. However, Jordan does not automatically deport UNHCR-recognized refugees if they are apprehended for working or residing in Jordan illegally, but instead gives them four options:

1.They can depart voluntarily (which is not a realistic option for UNHCR-recognized refugees);

2.They can stay in jail until UNHCR finds a durable solution on their behalf (the usual practice for those who have committed a serious crime or those whom the authorities consider to be a danger to the security of Jordan);

3.They can be released without conditions (the usual practice for those who were not caught working illegally, but who only overstayed their residency visas); or

4.They can be required to find a Jordanian sponsor who will guarantee their departure from Jordan as a condition for release (the usual practice for those caught working illegally or committing a minor crime).[61]

In all four cases the authorities formally issue a deportation decision and require the detainee to agree formally to leave the country as a condition for release from detention, though the authorities, in practice, do not necessarily require return to the home country. In practice, if UNHCR issues a letter on the refugee's behalf the authorities do not execute the deportation order, but use it as a means of keeping pressure on UNHCR to find a country willing to resettle the refugee.[62] Under the fourth option, Jordanian sponsors relinquish their identity documents to the arresting authority as a condition for the Iraqi's release. They are permitted to retrieve their IDs when they can verify the departure of the Iraqi refugee or find another sponsor to assume responsibility for the refugee.[63] Jordanian sponsors have been able to retrieve their identity documents by establishing that the Iraqi refugee had paid the accrued fines (which implicitly suggests that the refugee left the country since many pay their fines when exiting).[64] In some cases, however, the Jordanian sponsorship, in effect, serves as a mechanism for posting (and jumping) bail.

Human Rights Watch collected the names of 29 UNHCR refugee-card holders who had been paroled from detention after Jordanian sponsors provided guarantees on their behalf, often in return for money. In response to written questions by Human Rights Watch, eight of those former detainees described their arrest and release.[65] Jordanian police arrested them between February 2005 and April 2006 and detained them from two days to 24 days before releasing them, after Jordanian sponsors came forward on their behalf. The other 21 only gave their names and refugee-card numbers but did not fill out the questionnaire, fearing repercussions. "There are tens of refugees who were afraid to fill out, feeling afraid that some unknown thing would happen to them," said the refugee who collected the information for Human Rights Watch. "There are also a lot of the refugees who are still in prison and some who had been taken out of Jordan."[66]

Despite UNHCR's objections the Jordanian authorities deported three UNHCR-recognized refugees to Iraq in 2005; one had a criminal conviction and the other two were alleged to have committed crimes but had not been convicted.[67] Such returns constitute refoulement, a breach of Jordan's international obligations.

Asylum-seeker card holders under UNHCR's temporary protection regime

The UNHCR card for asylum seekers, issued as part of its temporary protection regime, offers little protection against deportation and no other benefits. Jordanian policy is to notify UNHCR when its law-enforcement officials detain asylum-seeker card holders on immigration violations and to allow UNHCR staff to visit them in the detention centers to conduct refugee status determinations. In fact, UNHCR conducted almost all of its RSDs in 2005 with people in detention.[68] The refugee agency intervened on behalf of 191 detained asylum-seeker card-holders in 2005. During that year Jordan deported 121 Iraqis who had held asylum-seeker cards but whom UNHCR rejected as refugees according to the 1951 Refugee Convention refugee definition.[69] UNHCR recognized 22 Iraqis as refugees in 2005.[70]

This raises immediate questions about the thoroughness of the RSDs and the refugee-definition standards on which they are based, the right to appeal negative UNHCR decisions, other due process rights that might be compromised in a detention setting, and, most obviously, the meaning and value of a supposed temporary protection regime that fails to protect everyone-including rejected asylum seekers-from deportation based on conditions of generalized violence. Rejected asylum seekers are subject to deportation, though UNHCR informs anyone whose application has been rejected that they may appeal the refugee agency's rejection of their refugee claims. In most cases detained asylum seekers do appeal UNHCR's first-instance rejection of their claims, according to UNHCR, and their deportations are suspended while the appeals are pending (though they remain in detention).[71]

Under normal circumstances rejected asylum seekers are no longer of concern to UNHCR, and their deportation would not raise protection concerns. Under a temporary protection regime, however, all nationals of the country experiencing warfare or generalized violence should fall under UNHCR's protection, even those who do not meet the 1951 Refugee Convention refugee definition. After UNHCR rejects a detained Iraqi asylum seeker, it sends the following letter to the Jordanian authorities:

UNHCR's position on the return of rejected Iraqis from Jordan is guided by the international legal principles governing its protection mandate, taking into consideration the situation of the concerned individuals as well as the cooperation of the Jordanian and Iraqi authorities. Within this context, UNHCR seeks the cooperation of the Jordanian authorities, as it has requested the cooperation of other States, in continuing to extend flexibility in allowing even rejected asylum seekers to remain in Jordan until such time as the security situation in Iraq has improved and the concerned individuals can be returned to Iraq at no security risk.[72]

That Jordan nevertheless deported 121 rejected asylum seekers in 2005 shows that it was not inclined to heed UNHCR's request to show flexibility. Despite the temporary protection regime, UNHCR does not regard these forced returns as refoulement and did not consider them as "people of concern" (a wider formulation that UNHCR sometimes uses) at the time they were deported.[73] UNHCR's position is inconsistent; it has called for a TPR "for all Iraqis" without distinction,[74] yet reveals a critical blind spot with respect to Iraqis who actually sought refugee-status protection but whom UNHCR found not to meet the 1951 Refugee Convention definition. Human Rights Watch regards the forced return of such Iraqis as refoulement because they sought protection in Jordan and because of the high level of risk of serious harm they face upon being forcibly returned to Iraq.

In practice even the asylum-seeker card's supposed limited protection of a guaranteed UNHCR refugee-status interview had broken down by the time of Human Rights Watch's visit. In one case a Shi`a woman from Najaf told Human Rights Watch that in March 2005, Jordanian authorities deported her husband, who had overstayed his visa and was working illegally, despite his UNHCR card:

He was arrested in Aqaba while he was working on a job site. They directly deported him. They told him, "You are a guest and you know the law. The law prevents you from working." He couldn't afford to pay the [residency fines]. He showed them the UN card, and they said it means nothing. When he was deported, they stamped his passport so he can't come back for five years. Even after five years, they won't allow him to go back to Jordan-when they see the stamp, they exclude you.[75]

While this man had committed a violation of Jordanian law by working without a permit, international law-the principle of nonrefoulement-nevertheless protects him from being returned to Iraq should he face there the likelihood of persecution, torture, or other serious harm. Since returning to Iraq, the wife said that her husband has been injured in a terrorist attack and suffered a heart attack. The authorities failed to respect the fact that he was carrying a UNHCR card, and thus clearly committed refoulement when they forcibly returned him to Iraq.

Persons UNHCR rejected as refugees prior to 2003, but whose need for at least temporary protection may have changed because of the war

Jordan regards asylum seekers who sought recognition as refugees with UNHCR during the Saddam Hussein era but who at the time were rejected as illegal aliens as subject to deportation, even though the circumstances in Iraq have changed and they may now be seriously harmed if returned. Despite proclaiming a blanket temporary protection regime UNHCR has refused to issue asylum-seeker cards intended to provide temporary protection to previously rejected asylum seekers, even though they now have the same needs for temporary protection as other de facto refugees living in Jordan.[76]

Formerly rejected refugee claimants have lived in Jordan for many years, and many have experienced various forms of hardship. A Shi`a man from Missan Governorate told Human Rights Watch about his separation from his wife and children. He said that he fled Iraq in 1998 after the government executed five of his relatives. He said that UNHCR rejected his refugee claim and that his family had been accruing large overstayer fines ever since his visa expired. Because UNHCR had rejected his refugee claim and closed his case, he was not eligible for an asylum-seeker card when UNHCR instituted its temporary protection regime in 2003. Faced with the possibility that the Jordanian authorities might arrest, detain, and deport his wife and five children, he decided to send them back to Iraq but felt that it would be too risky for him to return with them. The Jordanian border officials stamped their passports with red exclusion stamps. He does not know when he will see them again. "We are like prisoners of war," he told Human Rights Watch. "If I go to the border, I can't come back." Similarly, because of their exclusion stamps, his wife and children cannot come and visit him in Jordan.[77]

A 58-year-old Shi`a man, who told Human Rights Watch Iraqi officials had arrested him three times in the 1980s for his communist activities, said that UNHCR rejected his refugee claim in 2001 and closed his case. He said that the UNHCR office has repeatedly turned him away since the war began, and seven months ago (well within the time frame of the temporary protection regime) took away his old asylum-seeker card, leaving him with nothing to show the police if he is arrested for overstaying his visa.[78]

An Assyrian[79] Christian woman who has lived in Jordan since 1995 told Human Rights Watch of her increasingly desperate attempts to find temporary protection for her family after UNHCR rejected her husband's refugee claim in 1998. She said that her husband had been a member of an Assyrian political party, whom Ba`th Party officials had arrested and tortured, leaving him permanently handicapped. Despite his disability Iraq conscripted him into its military forces, from which he deserted-a capital offense. They arrived in Jordan in 1995 after Turkish and Syrian border guards had refused them entry at their respective borders. Jordanian police arrested her son in 1999 while walking on the street and jailed him for 13 days in the Zuhar police department for juveniles. "We went to UNHCR to ask for help to take him out of jail, but they said that the file was closed."[80] The police used her detained son as bait to apprehend the rest of the family, and they were all deported to Syria later that year. The family found that they could not earn enough to live in Syria; the mother and children returned to Jordan shortly after being deported, but her husband remained in Syria for more than a year before rejoining them in Jordan. Jordanian police apprehended her again in late 1999. She paid the fine for overstaying her visa and went to Lebanon as part of a tourist group for three days to renew her Jordanian visa for another six months.

After the war began and UNHCR started the temporary protection regime, this woman was able to get a UNHCR asylum-seeker card in her name that includes her children but excludes her husband. He therefore is denied whatever protection UNHCR might be able to provide under the TPR to asylum-card holders. The family lives in constant fear of deportation. "For eleven years my children did not go to school. My daughter worked in a picture studio, but one of her co-workers grew jealous of her and said she would call the police and report her for working illegally if she didn't quit. We are now too afraid to work." She added, "I would never ever consider going back to Iraq."[81]

Persons who have not approached UNHCR, but who fled persecution or generalized violence

Most deportees carry neither UNHCR refugee nor asylum-seeker cards, but may well have justified claims to refugee status based on their experiences in Iraq. Human Rights Watch interviewed an Assyrian Christian woman from Mosul whose husband was deported from Jordan on September 25, 2005. Jordanian police arrested him at a restaurant after a policeman apparently randomly asked him for his ID and found him to be without documents. His wife had his passport at home. She took the passport to UNHCR and told them her story of having fled Iraq (she had worked in a beauty salon, said something negative about the government one day during the Ba`thist era, and a customer reported her to the security forces, who falsely accused her of being a spy). She asked UNHCR to intervene on behalf of her husband. After the Jordanian police had detained her husband, she said that they requested his passport as part of the deportation process. She asked UNHCR to take the passport to the police station at al-Ashrafiya and to visit her husband there. She not only wanted UNHCR's intervention on behalf of her husband, but was afraid to take the passport to the police herself since she was also a visa overstayer: "I was afraid I would be deported too." She met with UNHCR. "I told them our story," she said. "He was still in the police department. I was crying." She said that UNHCR would not visit her husband while he was detained pending deportation because he had not previously registered with them. "They told me to calm down. They wouldn't take his passport. They were not interested to help."[82]

Four days after her husband's deportation, UNHCR gave the woman an asylum-seeker card. "I need to go to the market to do the things my husband used to do. People make comments. They insinuate things." She has spoken to her husband by phone. "He said that someone wrote on the church door 'Death to Christians.' My husband told me he is afraid to leave the house. He doesn't work. He told me not to come back."

Human Rights Watch contacted two Iraqis recently deported from Jordan to Iraq. Neither person had registered a refugee claim with UNHCR in Jordan, but one of the two, a young woman working as a translator in Baghdad's Green Zone, said she fled to Jordan because she had received death threats.[83] She fled Iraq in September 2005 after an Iraqi National Guardsman at a checkpoint close to the Green Zone told her, "We know you are a translator for the Americans. We know who all the translators are." She told Human Rights Watch that she asked for protection after Jordanian intelligence arrested her and began proceedings to deport her.

The intelligence officers arrested her at the airport in Amman on November 18,2005(within two weeks of the hotel bombings), when she went to pick up an American friend. She had just extended her visa the day before and was legally in Jordan. Intelligence officers interrogated her and five other Iraqis who had come to pick up people at the airport that day. They accused her of carrying a false passport andsaid she was also involved in"carrying out the explosions." She was transferred to the women's section of the Nadhala Prison in Juwaida. At the prison, guards denied her permission to make a phone call. She asked for a lawyer, but they denied her request. She then tried to make a refugee claim, telling her jailers that she had worked for U.S. companies and the U.S. military in Baghdad and had been threatened. "That is not our problem," she was told. She was deported on November 27. Human Rights Watch spoke to her by telephone in Baghdad. She left soon thereafter for Egypt.[84]

The seconddeportee, a young man, also gave good reasons for fleeing Iraq but said that Jordanian police did not provide him any opportunity to explain his circumstances or to seek protection.[85] Unknown assailants killed two of his nieces in Iraq for their alleged collaboration with the Americans.[86] He is engaged to an American citizen and had an appointment pending with the U.S. consular section in Amman at the time the police arrested him, on April 16, 2006. The young man said he had gone to the airport to drop off his uncle, who was flying to the United States, but police stopped and detained him at the checkpoint on the airport road. He spent three days in detention, during which time he made desperate calls to his family members asking for wasta (intervention by people with connections in government). At the time of his arrest he had overstayed his visa by about three months. He had been in Jordan for one year, renewing his visas by exiting and re-entering Jordan. The last time he went to renew his visa, however, the Jordanians at the Syrian border only gave him a three-day visa. Hequickly became an overstayer.

In a telephone interview with Human Rights Watch from Mosul, Iraq, the young deportee said he begged the intelligence officers to let him pay the JD130 fine, but they refused. He recalled, "There was no questioning. They only said, 'You will be deported.' They did not ask me if I was afraid to return to Iraq." He said that he had not known that there was such a thing as a UNHCR asylum-seeker card. Military guards took him by bus to the border with about 40 other persons. They let them off at the Karama-Trebil crossing, in the middle of nowhere. He had to find a taxi to Baghdad and from there make his way back to his home in Mosul. He said that he has no job and no money, and that he has lost his visa appointment with the U.S. consular section in Amman and does not know if he can submit a U.S. visa application in Baghdad.[87]

V. UNHCR and Temporary Protection

The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan signed a Memorandum of Understanding with UNHCR in 1998 that allows the UN refugee agency to exercise its mandate to recognize refugees with the proviso that it must find places outside Jordan to resettle them within six months of recognizing them.[88] In practice, Jordan has tolerated the stay of many UNHCR-recognized refugees well beyond the six-month resettlement deadline.[89]

In response to an anticipated refugee exodus from Iraq following the U.S.-led war, UNHCR in April 2003 declared a temporary protection regime on behalf of Iraqi refugees in Jordan, Syria, and Lebanon.[90] UNHCR concluded a Letter of Understanding with the Jordanian government that it cites as the legal basis for the TPR, but which the Jordanian government interprets differently.[91] UNHCR's 2006 Country Operations Plan for Jordan states, "UNHCR continues to promote the TPR for all Iraqis, which were [sic] formally agreed upon with the Government of Jordan (GoJ) in a Letter of Understanding signed on April 15, 2003."[92]Jordan, however, only recognizes the TPR as applying to al-Ruwaishid camp, a closed facility near the Iraqi border that currently holds fewer than 500 refugees, mostly Palestinians and Iranian Kurds.[93] Mukhaimar F. Abu Jamous, the secretary-general of the Ministry of Interior, told Human Rights Watch that UNHCR's April 2003 statement announcing the TPR was "a unilateral declaration that we did not recognize."[94] He said that the Letter of Understanding with UNHCR concerned temporary protection for refugees in the border area camp, not a broader temporary protection regime.[95] Human Rights Watch has obtained a copy of the letter, which supports the Jordanian reading.

In addition to insisting that it never agreed to the TPR, Jordan has also communicated to UNHCR that whatever need may have existed for temporary protection has long since ended. As early as April 2005 the Jordanian government told UNHCR that it should not apply the TPR "long after the war in Iraq was over."[96]

UNHCR nevertheless continues to issue the asylum-seeker cards[97] and renew them every six months as though the TPR exists, although Jordanian officials do not recognize these documents for residency status purposes and the cards provide no benefits, such as work authorization or eligibility for public assistance. Their sole utility is in the event of arrest to enable the detained card bearer to ask for a visit from a UNHCR official to conduct a refugee status determination. Although the term asylum seeker indicates a pending refugee claim, UNHCR in practice suspended RSDs once it declared the TPR (except for card holders in detention).

UNHCR took no further action on Iraqi asylum claims after 2003, leaving the people who had been issued asylum-seeker cards in limbo over their future. It reasoned that refugee screenings would invariably result in some denials, and it did not want to act in a way that could result in Jordan deporting denied asylum seekers to an ever more violent Iraq. Suspending refugee screening meant, however, that Iraqis would not be recognized as refugees and thus UNHCR would be unable to refer them for third-country resettlement.

UNHCR also had a practical reason for suspending RSDs: its resources did not remotely match the requirements of an influx of hundreds of thousands of Iraqis into Jordan,[98] and there was no possibility of a durable solution for large numbers of recognized refugees. Two such solutions would have been resettlement outside the region, which is at the discretion of third-country governments, or local integration, which Jordan had categorically ruled out.[99] The United States, the largest refugee resettlement country at the time, had declared a moratorium on the resettlement of any Iraqi refugees following the September 11, 2001, attacks (which remained in effect until being officially lifted in April 2005).[100] In 2005, the United States admitted 12 Iraqi refugees referred by UNHCR-Amman and admitted another six persons on family reunification grounds without UNHCR involvement.[101]