<<previous | index | next>>

Preplanned Targets

Strategic targeting consists of preplanned missions against fixed facilities. In Iraq, Coalition forces attacked most of these in the first few days of the war with cruise missiles and other precision-guided munitions. This targeting was characterized by strikes designed to destroy, degrade, or deny the ability to command and control Iraqi forces and/or employ weapons of mass destruction. Preplanned targets included leadership, government, security, and military facilities, and certain dual-use infrastructure elements (such as electrical power, media, and telecommunications facilities).96

Attacks on these facilities generally did not result in civilian casualties or extensive damage to civilian property for a number of reasons. U.S. strategy avoided power plants, public water facilities, refineries, bridges, and other civilian structures. Most of the facilities that were hit were in areas to which the civilian population did not have access. Thorough collateral damage estimates were done for each of the preplanned targets. Finally, these attacks were carried out exclusively with precision-guided munitions.

Human Rights Watch’s investigations found, however, that air strikes on civilian power facilities in al-Nasiriyya caused serious civilian suffering and that the legality of the attacks on media installations is questionable.

Dual-Use Targets

Dual-use facilities are those that can have both a military and civilian application. In Iraq, the United States and United Kingdom considered electrical power, media, and telecommunications installations dual use and attacked examples of each. In some instances, however, it was not clear to Human Rights Watch why Coalition forces characterized certain installations in that way. A dual-use object may be a legitimate military target because it makes an “effective contribution to military action” and its destruction offers “a definite military advantage.”97 Yet the harm to the civilian population in its destruction may be disproportionate to the expected “concrete and direct military advantage,” rendering an attack impermissible.98 In assessing potential targets, military planners must carefully balance the concrete and direct military advantage of destroying these facilities against the expected death and injury to civilians and damage to civilian objects.99

Electrical Power Facilities

The United States targeted electrical power distribution facilities, but not generation facilities, throughout Iraq, according to a senior CENTCOM official. He told Human Rights Watch that instead of using explosive ordnance, the majority of the attacks were carried out with carbon fiber bombs designed to incapacitate temporarily rather than to destroy.100 Nevertheless, some of the attacks on electrical power distribution facilities in Iraq are likely to have a serious and long-term detrimental impact on the civilian population.

Electrical power was out for thirty days after U.S. strikes on two transformer facilities in al-Nasiriyya.101 Al-Nasiriyya 400 kV Electrical Power Transformer Station was attacked on March 22 at 6:00 a.m. using three U.S. Navy Tomahawk cruise missiles outfitted with variants of the BLU-114/B graphite bombs.102 These dispense submunitions with spools of carbon fiber filaments that short-circuit transformers and other high voltage equipment upon contact.

The United States attacked al-Nasiriyya 400 kV Electrical Power Transformer Station on March 22, 2003, with a carbon fiber bomb designed to disable power. The city lost power for thirty days. © 2003 Reuben E. Brigety, II / Human Rights Watch

The transformer station is the critical link between al-Nasiriyya Electrical Power Production Plant and the city of al-Nasiriyya.103 When the transformer station went off-line it removed the southern link to all power in the city, which was then totally reliant on the North Electrical Station 132. Although the carbon fiber is supposed to incapacitate temporarily, three transformers were completely destroyed by a fire from a short circuit caused by the carbon fiber. The station’s wires seemed to have been melted by the intense fire. Human Rights Watch was told that the transformers would have to be replaced and the entire facility rewired.

On March 23 at 10:00 a.m., the United States attacked North Electrical Station 132. Hassan Dawud, an engineer at the station when it was attacked, said a U.S. aircraft strafed the facility, destroying three transformers, gas pipes, and the air conditioning, which brought the entire facility down as components that were not damaged by the attack overheated.104 Damage to the transformers and air conditioning were clearly visible, including large holes in the walls consistent with aircraft cannon fire. Further north in Rafi on Highway 7, Human Rights Watch found a transformer station with significant damage from air strikes, including at least one destroyed transformer.

From its investigations, it is unclear to Human Rights Watch what effective contribution to Iraqi military action these facilities were making and why attacking them offered a definite military advantage to the United States, and in particular how they supported the ground operations in al-Nasiriyya. Two senior CENTCOM officials declined to comment on these attacks.105 Human Rights Watch does not understand the military necessity and rationale for these attacks and calls on the United States to explain them fully.

The attacks caused significant and long-term damage, and the civilian cost was high. Dr. `Ali `Abd al-Sayyid, director of al-Nasiriyya General Hospital, told Human Rights Watch that the loss of power was a huge impediment to the proper treatment of war wounded. No one died as a direct result of the power loss, but the hospital’s generators were taxed to their limit and it had to do away with some non-critical services to ensure the wounded were given basic treatment. He also stated that the loss of power created a water crisis in the city.106

Human Rights Watch researchers saw many areas in al-Nasiriyya where people had dug up water and sewage pipes outside their homes in a vain attempt to get drinking water. Even when successful, the water was often contaminated because the power outage prevented water purification. This led to what Dr. `Abd al-Sayyid termed “water-born diarrheal infections.”107

Human Rights Watch believes that extreme caution should be used in the targeting of electrical power facilities because of the potential profound and long-term impact on civilian populations. The loss of electrical power in the first Gulf War, for example, crippled basic civilian services, including hospital-based medical care, and shut down water distribution, water purification, and sewage treatment plants. This led to death and suffering, especially among the most vulnerable members of the population.108

In particular, Human Rights Watch believes that civilian electrical generation (production) facilities should not be attacked because replacement is costly and time-consuming, thereby causing prolonged human suffering. As seen in Yugoslavia, attacks on electrical distribution facilities can have a lesser impact. If distribution facilities are attacked, it should be done in such as way as to cause only temporarily incapacitation.

Al-Nasiriyya case is positive in some respects. Power distribution—not power generation—was targeted. Although it took a month for power to be fully restored, it would have taken much longer to rebuild an entire power production plant. The use of carbon fiber weapons may have prevented civilian casualties at the facility and allowed for quicker repair.

The United States dropped these carbon fiber filaments in an attack on electrical power in al-Nasiriyya. These filaments are designed to disable power, but in this case they caused a fire that destroyed the transformer station and plunged the city into darkness for thirty days. © 2003 Marc Garlasco / Human Rights Watch

Media Installations

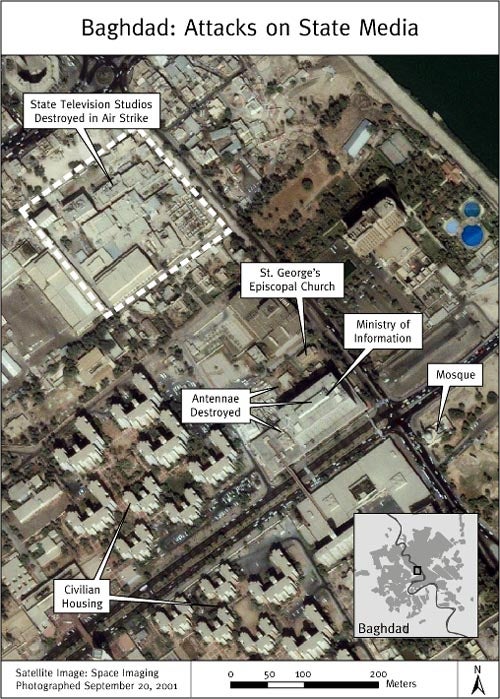

Human Rights Watch researchers visited three media facilities in Baghdad hit by U.S. air strikes: the Ministry of Information, the Baghdad Television Studio and Broadcast Facility, and the Abu Ghraib Television Antennae Broadcast Facility. While special care seems to have been taken to avoid civilian casualties when attacking the Ministry of Information, the latter two facilities were completely destroyed. There were no recorded civilian casualties as a result of any of these attacks.

The March 28 attack on the Ministry of Information was carried out with the CBU-107 Passive Attack Weapon, marking its first use in combat.109 The CBU-107, nicknamed the “rods from God” by the U.S. military, is a new non-explosive cluster bomb that contains 3,700 inert metal rods designed to destroy “soft” targets, i.e., those without armor. In this case, two CBU-107s were used to remove antennae on the roof of the building without destroying the facility. The custodian of Saint George’s Episcopal Church, next door to the ministry, told Human Rights Watch of seeing a series of bombs in the sky over the ministry.110 Visible observation of the facility confirmed that there was little to no structural damage done by the air strike, though the antennae were destroyed. The church adjacent to and a mosque across the street from the ministry suffered minimal damage, primarily broken windows, in the attack.

Map 12

Download PDF (1.8 Mb)

Prior to this attack the United States had used a Predator dronearmed with a Hellfire missile to destroy a single uplink antenna at this facility. The use of the armed Predator allowed CENTCOM to confirm visually there were no civilians in the area during the attack. The Predator also had a smaller warhead than the majority of bombs dropped during the war, thereby reducing damage to the area and the potential for civilian casualties.

In contrast to the Ministry of Information, the Television Studio and Broadcast Facility and the Abu Ghraib Television Antennae Broadcast Facility were completely destroyed. The former is in a Baghdad business district, while the latter is in an isolated area.

The U.S. targeting of the television broadcast capabilities of Iraq appears to have been aimed at denying Saddam Hussein and his government the ability to broadcast official statements on television. The United States attempted to end Iraqi government broadcasts by destroying television facilities but failed to do so until April 8, the day before Baghdad fell. The Iraqi authorities, like the Serbian authorities before them, maintained television broadcasts by using mobile assets and redundant broadcast capabilities.111

A senior CENTCOM official told Human Rights Watch,

The personality of the regime used the tool of the media. . . . It was clear we needed to eliminate the regime’s ability to put out disinformation. . . . Most important was the Iraqi TV’s military value. We have felt pretty comfortable that it was one of the means Iraqi intelligence used to signal its elements outside the country. . . . There was a potential for terrorist activity. . . . Did it happen? No. We were concerned it would happen, felt the potential for a catastrophic event outweighed the potential ill will. But the Iraqis never used TV to direct the military. There were songs we knew of they could use and had in the past that would tell forces where to go and to take certain actions. This is why we took out TV.112

There is no evidence that Iraqi media was being used to provide direct assistance to the Iraqi armed forces. If the media is used to incite violence, as in Rwanda, or to direct troops, it may become a legitimate target. The media facilities in Iraq, however, did not appear to be making an effective contribution to military action. As a consequence, Human Rights Watch believes that while stopping broadcasts intended to give encouragement to the general population may have served to demoralize the Iraqi population and undermine the government’s political support, neither purpose offered the definite military advantage required by law to make media facilities legitimate military targets.

Civilian Telecommunications Facilities

U.S. attacks largely destroyed the telecommunications infrastructure in Iraq. The main telecommunication gateway switches Sinek and Ma’mun were both destroyed by GBU-37/B 5,000-pound guided bombs.113 Their destruction removed all long-distance calling capability from Iraq to the outside world. There were no reported civilian casualties in the attacks on these facilities, probably because of the timing and weapon choice. The attacks all took place at night when the chance of civilians being present was lessened. The bombs used were penetrators, which are designed to bury deep inside a target before exploding, therefore imploding the building and minimizing damage to the surrounding area.

Other telecommunications exchanges in Baghdad were also destroyed, though smaller munitions were used. In many of the strikes on telecommunications facilities, the United States targeted and destroyed cable vaults leaving the facilities relatively undamaged, which should facilitate their reconstruction. Post-war looting, however, rendered these precautions irrelevant because thieves picked most of the facilities clean.

According to a senior CENTCOM official:

We waited very long to hit civil telecoms. Military comms were automatic. But Iraq had spent a lot of money and time on contracts with China, France, and Yugoslavia setting up a modern fiber optic and coaxial cable telecoms network to support the military comms. We took a shoot-listen-shoot approach. We knew the risk was giving the Iraqi propaganda an opportunity to stay on the network. The principal objective early on was to sever command and control for fielded forces. The Iraqi military had a very central command and control process. If we could eliminate high-level commands, the regional and local commands became autonomous and many were less likely to die for their country if they didn’t feel directly supervised and had no commands from the leadership. . . . This reduced the likelihood of street fighting in Baghdad.114

Government Facilities

Preplanned targets primarily included leadership buildings, government buildings, and security buildings. These attacks, carried out by the United States solely with precision-guided munitions, led to few known civilian casualties. In addition to the accuracy of such weapons, thorough collateral damage estimates helped minimize the civilian toll. Human Rights Watch researchers also noted instances where weapon choice and fuzing contributed to the low casualty rate from bombing. Moreover, civilian casualties were limited by Iraq’s policy of locating the majority of these facilities away from the population. Even where these facilities were in populated areas, they were often separated by security perimeters and walls.

The methodology used in U.S. attacks on government buildings, and the success in avoiding civilian casualties, stands in stark contrast to other U.S. attacks, particularly those targeting leadership and those involving cluster bombs. The United States took extensive precautions to avoid civilian casualties and other civilian harm when planning and executing attacks on strategic targets such as government facilities. Because of these precautions, there were few civilian casualties even in densely populated areas. Having demonstrated its ability to do so, the United States should apply the same level of care and consideration in targeting and executing other air attacks as in the cases below.

The Republican Palace Complex and Other Government Buildings

Throughout Baghdad, Human Rights Watch researchers found bombed government, intelligence, and security facilities. The use of precision-guided weapons combined with the fact that most of these facilities were designed by the government to limit access by the civilian population, however, minimized civilian casualties. The Republican Palace complex in downtown Baghdad contained the Republican Palace, the Revolutionary Command Council buildings, the Presidential Secretariat, Saddam’s Bunker, the Ministry of Planning, and offices and living quarters for Saddam Hussein’s guards. Tomahawk cruise missiles and JDAMs hit the entire area, except for the Republican Palace, which was not bombed during the war and currently serves as the headquarters for the Coalition Provisional Authority. The palace complex had always been completely off limits to all civilians, and Baghdadis told Human Rights Watch researchers that the area had been deserted for days as government officials expected the attacks.

Another good example is the Iraqi Intelligence Service Headquarters, a sprawling complex with many buildings in the center of a populated area in al-Mansur district of Baghdad. Due to the high walls and location of buildings in the center of the compound and the accuracy of the precision-guided weapons, there were apparently no civilian casualties from the air strikes.

Attacks on buildings without such protection had similar results. Human Rights Watch was told the headquarters of the Baghdad Emergency Forces was struck by a GBU-37 5,000-pound penetrator bomb.115 This multistory building is a few hundred yards from an apartment complex, but the apartment windows were still intact. It appears that the penetrating nature of the weapon contained the blast and fragmentation damage.

Baghdad International Fairgrounds

U.S. forces attacked the Baghdad International Fairgrounds, which had been occupied by the Iraqi Intelligence Service. The fairgrounds consisted of dozens of buildings used for trade shows and business conventions. Across the street from the fairgrounds is the Baghdad Red Crescent Maternity Hospital; Human Rights Watch spoke to the director, Dr. Rasmi al-Rikabi. He said that the Mukhabarat had left their headquarters complex in al-Mansur district and had occupied the Fairgrounds and his hospital. The hospital had been evacuated two weeks earlier, but a skeleton staff remained and watched as the Mukhabarat freely operated from the hospital. Dr. al-Rikabi said that the Mukhabarat threatened to kill him if he questioned their presence so he remained silent.116

Map 10

Download PDF (1.1 Mb)

At 9:00 a.m. on April 2, nine 2,000-pound precision-guided bombs struck the International Fairgrounds, blowing the glass out of the hospital and partially collapsing a secondary roof. One person in the street was killed and twenty-five or so suffered minor injuries, mostly from glass. The Mukhabarat evacuated the area and Dr. al-Rikabi treated the wounded.117

It appears the United States took precautions to minimize civilian casualties. Though 18,000 pounds of bombs were dropped some one hundred yards (ninety meters) away from the hospital, the angle of the attack seems to have limited the blast and fragmentation damage and directed it away from the hospital. There also appears to be some evidence of delayed fuzing, which caused the buildings to implode and thus contained damage.

Directorate of General Security Facilities

The Directorate of General Security (DGS), the Iraqi security organization responsible for monitoring political dissent, was a fixture throughout Iraq. During the war, DGS was responsible for coordinating local militias. There were DGS offices in most Iraqi cities, and all had prison cells and basement holding cells where Iraqi dissidents were tortured and killed. DGS facilities served as stark reminders to the population of their expected loyalty to Saddam Hussein, and as such were placed close to civilian facilities. In al-Nasiriyya, for example, the DGS headquarters building stood across the street from the General Hospital. In Basra it was across from the courthouse and other civil establishments. The presence of above ground prisons complicated the targeting of DGS facilities. Each DGS compound in Iraq has a prison, sometimes, as in Basra and al-Nasiriyya, in close proximity to the headquarters building. In both cases the United States was able to destroy the DGS headquarters buildings with little or no damage to the prisons. The United States apparently used penetrating weapons on each headquarters building and fired at an angle so that it would not spread damage to the prisons. The bombings also took place at night, offering further protection to the civilian population.

Conclusion and Recommendations

The Coalition’s record with preplanned targets in Iraq was mixed. It used precision-guided munitions and careful targeting to minimize civilian casualties in dozens of strikes on government buildings. U.S. attacks on alleged dual-use targets, however, were more controversial. Its destruction of media facilities was of questionable legality; Human Rights Watch found no evidence that the media was used to support Iraq’s military effort. Coalition strikes on electrical power distribution facilities—although questionable military targets—demonstrate an attempt, through choice of weapons and targets, to reduce the effects on civilians, but the results still caused extensive civilian suffering.

Human Rights Watch recommends:

Extreme caution be used in the targeting of electrical power facilities. In particular, electrical generation facilities should not be attacked at all. If electrical distribution facilities are attacked, it should be done in such a way as to cause only temporary incapacitation. Media installations not be attacked unless it is clear that they make an effective contribution to military action and their destruction offers a definite military advantage. Precision-guided munitions be used whenever possible, especially on targets in populated areas.

Cluster Bomb Strikes

While U.S. and U.K. air forces used primarily precision-guided munitions, they also dropped cluster bombs, which are notorious for causing harm to civilians.118 Cluster munitions are large weapons that contain dozens and often hundreds of smaller submunitions. They can be air-launched or surface-delivered, releasing “bomblets” or “grenades” respectively. These weapons endanger civilians during strikes because they blanket a broad area with submunitions and are often inaccurate. They also leave large numbers of hazardous unexploded submunitions, or duds, that threaten civilians after the conflict. In Iraq, U.S. and U.K. use of cluster bombs caused civilian casualties both during strikes and afterwards. Their air forces for the most part demonstrated, however, that they had learned some of the lessons of past wars, notably in dropping far fewer cluster bombs in populated areas. In contrast to Coalition ground forces, they significantly reduced the humanitarian harm of cluster strikes through better targeting and technology.

Introduction to Cluster Munitions

The military values cluster munitions because of their wide footprint and versatile submunitions. These munitions are area weapons that spread their contents over a large field, or footprint. Because of the dispersal of their submunitions, they can destroy broad, relatively soft targets, like airfields and surface-to-air missile sites. They are also effective against targets that move or do not have precise locations, such as enemy troops or vehicles. The submunitions themselves usually have multiple effects. Most of the models used in Iraq were both antipersonnel and anti-armor weapons.119

The military advantages of cluster munitions, however, must be weighed against their tendency to cause harm to civilians both during and after strikes. Most models, whether air-dropped or ground-launched, are unguided, and even those with guidance mechanisms are rarely precision guided. Unguided cluster munitions can miss their mark and hit nearby non-military objects. Once a cluster casing opens, it releases hundreds of submunitions that are also unguided120 and disperse over a wide area.121 Although other types of unguided weapons can miss their target, the humanitarian effects of a cluster accident are often more serious because of the submunitions’ wide dispersal. Even if a cluster munition hits its target, the submunitions may kill civilians within the footprint. The inherent risks to civilian life and property increase when a party uses these weapons in or near populated areas. If cluster munitions are used in an area where combatants and civilians commingle, civilian casualties are almost assured.122

Cluster munitions produce problematic aftereffects because many of the submunitions do not explode on impact as intended. While all weapons have a failure rate, cluster munitions are more dangerous because they release large numbers of submunitions and because certain design characteristics, based on cost and size considerations, increase the likelihood of submunitions’ failure. As a result, every cluster munition leaves some unexploded ordnance. The dud, or initial failure, rate, i.e. the percentage that does not explode, not only reduces cluster munitions’ military effectiveness but also puts civilians at great risk. Unexploded bomblets and grenades became de facto landmines that kill or injure civilians returning to the battle area after the attack.123

Coalition cluster munitions caused harm to civilians both during and after strikes in Iraq. This chapter and the next discuss the humanitarian impact of air and ground strikes, respectively. A third chapter discusses the aftereffects of cluster duds.

Cluster Bomb Strikes in the Iraq Air War

In three weeks from March 20 to April 9, U.S. and U.K. air forces dropped more cluster bombs in Iraq than they did in Afghanistan in six months. In Iraq, the United States used at least 1,206 clusters, containing more than 200,000 submunitions, only twenty-two shy of its half-year total for Afghanistan.124 This number represents 4 percent of the total number of air-delivered weapons used by the Coalition. The U.S. Air Force used a wide variety of these bombs, including 818 CBU-103s, 182 CBU-99s, 118 CBU-87s, and 88 CBU-105s. The United States also deployed 253 AGM-154 Joint Stand Off Weapons (JSOWs) and 802 BGM-109 TLAMs, which can contain submunitions, but it did not report how many of those used in Iraq carried submunitions.125 The side yard at the civil defense office in al-Hilla illustrated the breadth of the U.S. cluster arsenal. Clearance teams from this one city had collected pieces of cluster munitions delivered by planes and cruise missiles, as well as helicopters, artillery, and Multiple Launch Rocket Systems (MLRS). The array contrasts with Afghanistan where primarily CBU-87s and CBU-103s, different versions of the same bomb, were used. The United Kingdom contributed to the Coalition’s cluster bomb use in Iraq. It dropped seventy RBL-755s, containing 147 submunitions each for a total of 10,290.126

A clearance expert at al-Hilla Civil Defense Headquarters holds up two types of U.S. cluster submunitions used in Iraq. On the left is a ground-launched Dual-Purpose Improved Conventional Munition (DPICM), and on the right an air-dropped BLU-97. The duds he is holding were not dangerous because the fuzes and explosives had come out. © 2003 Bonnie Docherty / Human Rights Watch

The majority of the Coalition’s cluster bombs were CBU-103s, which had been deployed for the first time in Afghanistan. This bomb consists of a three-part green metal casing about five-and-a-half feet (1.7 meters) long with a set of four fins attached to the rear. The casing, which contains 202 bomblets packed in yellow foam, opens at a pre-set altitude or time and releases the bomblets over a large oval area. The CBU-103 adds a Wind Corrected Munitions Dispenser (WCMD) to the rear of the unguided CBU-87, which is designed to improve accuracy by compensating for wind encountered during its fall. It also narrows the footprint to a radius of 600 feet (183 meters).127

The CBU-103’s bomblets, known as BLU-97s, are soda can-sized yellow cylinders. Each one of these “combined effects munitions” represents a triple threat. The steel fragmentation core targets enemy troops with 300 jagged pieces of metal. The shaped charge, a concave copper cone that turns into a penetrating molten slug, serves as an anti-armor weapon. A zirconium wafer spreads incendiary fragments that can burn nearby vehicles.128 This type of bomblet was the payload for 78 percent of the reported U.S. cluster bombs; CBU-87s and CBU-103s both contain 202 BLUs. When used as cluster munitions, the AGM-154 JSOW contains 145 BLUs and the TLAM carries 166 BLUs.129

In Iraq, the Coalition used cluster bombs largely for their area effect and anti-armor capabilities. A CENTCOM official explained that common targets included armored vehicles or, when used with time-delay explosives, the path of thin-skinned vehicles.130 “I know that some were used in more built-up areas, but in most cases they were used against targets where there were those kinds of equipment—guns, tanks,” he said.131 Human Rights Watch’s field investigation supported these comments. Most of the cluster air strike sites it visited contained tanks, missiles, artillery, or thin-skinned vehicles. In a date grove in Hay Tunis, a neighborhood of Baghdad, Iraqis had hidden about a dozen military vehicles. The United States targeted it with both CBUs and unitary munitions. In Sichir, a small village outside al-Falluja, the United States dropped CBU-103s on a field with military vehicles protected by berms. Human Rights Watch found two casings and dozens of pieces of BLU debris at the adjacent chicken farm. In Agargouf, north of Baghdad, BLU duds were strewn across a field with SA-3 surface-to-air missiles and an accompanying radar truck. While military vehicles are legitimate targets, the impact of cluster bombs on civilians must still be considered.

The U.S. Air Force reduced the danger to civilians from clusters by modifying its targeting and improving technology. Apparently learning a lesson from previous conflicts, the Air Force dropped fewer cluster bombs in or near populated areas. While Human Rights Watch found extensive use of ground-launched cluster munitions in Iraq’s cities, it found only isolated cases of air-dropped cluster bombs. As a result, the civilian casualties from cluster bomb strikes were relatively limited. According to a senior CENTCOM official, air commanders received guidance that one of their objectives was to minimize civilian casualties. “In the case of preplanned cluster munition strikes, I am more confident that concern for collateral damage was very high,” he said.132 Less care went into strikes on emerging targets in support of ground troops. The CENTCOM official explained that B-52 bombers would carry a variety of munitions and loiter over the battlefield. If a ground commander called for support and cluster bombs were the only option left, the commander might accept them for his target. “As the battlefield unfolds and the sense of urgency on the ground goes up, my personal opinion is the urgency of the ground commander may be more for protection of his forces. Therefore choosing the optimal weapon is less important than getting a weapon on target,” the official said.133

When the Air Force did not avoid populated areas, cluster bomb strikes caused civilian casualties. The Baghdad date grove was located immediately across the street, on at least two sides, from Hay Tunis, a densely populated, residential neighborhood. Nihad Salim Muhammad was washing his car when the bombs hit. During the strike, the bomblets injured several people on his street, including four children.134 Around midnight on April 24, the U.S. Air Force dropped at least one CBU-103 on al-Hadaf girls’ primary school in al-Hilla.135 The strike killed school guard Hussam Hussain, 65, and neighbor Hamid Hamza, 45, and injured thirteen others, according to Hamid Mahdi, a 30-year-old butcher who lived across the street.136 The manager of the school said there were dozens of paramilitary troops in the neighborhood at the time of the strike.137 While the Air Force minimized civilian harm by dropping the bombs at night, the incident shows the dangers of dropping clusters in populated areas.

The Air Force also reduced the threat to civilians from cluster bomb strikes by using improved technology. The guided CBU-103, which is more accurate due to the WCMD, represented about 68 percent of the total number of reported cluster bombs used by the United States. Other cluster bombs with guidance systems included the CBU-105 and any JSOWs and TLAMs that carried submunitions. Such weapons choice is a dramatic improvement over that in the 1991 Gulf War and Yugoslavia, as well as Afghanistan, where the CBU-103 was introduced. In the latter conflict, use of older, unguided CBU-87s contributed to dozens of civilian deaths because they strayed from their targets and landed on nearby villages.138 The WCMD technology probably contributed to the low

An Iraqi girl sits in the playground of the pockmarked al-Hadaf primary school in al-Hilla. U.S. cluster bomblets killed two civilians and injured thirteen when they hit the school on April 24, 2003. © 2003 Marc Garlasco / Human Rights Watch

number of casualties in urban strikes like the ones in al-Hilla and Hay Tunis.139 Given their location in the middle of urban areas, a less accurate weapon could have caused disastrous consequences. Despite the improved accuracy of the CBU-103, it is still not a precision-guided weapon, and the individual submunitions remain unguided and inaccurate. Militaries should not use cluster bombs in or near populated areas because their broad footprint and large number of bomblets make any error too deadly.

In addition to using the CBU-103 with WCMD, the U.S. Air Force took another major step toward increasing civilian protection by introducing the new CBU-105, or Sensor Fuzed Weapon. Similar to the CBU-87 and CBU-103 on the outside, this weapon contains ten BLU-108 submunitions that include four hockey puck-sized “skeets” each. It has a WCMD, which guides the casing, and, more importantly, an infrared guidance system on each skeet that directs it to armored vehicles.140

Despite some improvements in technology, one of the Coalition’s major failings with cluster bombs was use of outdated cluster bombs. Both the United States and United Kingdom continued to drop older models that are highly inaccurate and unreliable. In addition to unguided CBU-87s, the United States used 182 Vietnam-era CBU-99 Rockeyes, containing 247 Mk-118 submunitions.141 The United Kingdom used seventy RBL-755s, similar to the Rockeye but with 147 submunitions.142 Rockeyes, which were developed in the 1950s, were used in great numbers in the Vietnam War and 1991 Gulf War. Such outdated stockpiles should not be used, especially now that the Coalition has technology that can reduce the civilian casualties caused by cluster bomb strikes.143

Conclusion and Recommendations

The immediate effects of cluster bombs, i.e. the damage done during strikes, may in certain cases be indiscriminate because the weapons cannot be precisely targeted. International humanitarian law prohibits attacks “which employ a method or means of combat which cannot be directed at a specific military objective.”144 Bombings that treat “separated and distinct” military objectives as one are also expressly prohibited.145 Cluster bombs are area weapons, useful in part for attacking dispersed or moving targets. They cannot, however, be directed at specific soldiers or tanks, a limitation that is particularly troublesome in populated areas. The principle that multiple targets should not be treated as one supports the argument that cluster bombs should not be used in populated areas.

As stated above, an attack is disproportionate, and thus indiscriminate, if it “may be expected to cause incidental loss of civilian life, injury to civilians, damage to civilian objects, or a combination thereof, which would be excessive in relation to the concrete and direct military advantage anticipated.”146 Some kinds of cluster bomb attacks tend to tip the scale toward being disproportionate. While Human Rights Watch neither has the information nor is in a position to evaluate the military advantages expected from the cluster bomb attacks, it is nevertheless concerned about the significant civilian casualties these attacks caused.

An August 2001 U.S. Air Force background paper acknowledges that cluster munitions “must pass [the] proportionality test” and states that there are “[c]learly some areas where CBUs normally couldn’t be used (e.g. populated city centers).”147 The definition of a populated area should include not only cities but also villages and their environs.148 Based on research in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Yugoslavia, Human Rights Watch believes that when cluster bombs are used in any type of populated area, there should be a strong, if rebuttable, presumption under the proportionality test that an attack is indiscriminate.

In Iraq, the U.S. Air Force took steps to reduce humanitarian harm by using newer, guided cluster bombs and generally avoiding populated areas. Human Rights Watch did not find many examples of urban strikes, but any that did happen would have to be evaluated on a case-by-case basis for compliance with IHL. As will be shown in the next chapter, the use of ground-launched submunitions is a very different story.

Human Rights Watch has since 1999 called for a suspension of cluster bomb use until the weapon’s humanitarian effects have been fully addressed.149 If armed forces do use cluster bombs, Human Rights Watch recommends the following to minimize civilian casualties during cluster air strikes:

- Armed forces should cease use of old, unguided and unreliable cluster bombs, such as the Rockeye, CBU-87, and RBL-755.

- Armed forces should not use cluster bombs in or near populated areas.

96 Human Rights Watch telephone interview with senior CENTCOM official #2.

97 Protocol I, art. 52(2).

98 Ibid., art. 51(5)(b).

99 Ibid.

100 Human Rights Watch telephone interview with senior CENTCOM official #2.

101 Human Rights Watch interview with `Ali Bashi Jabbar, chief of operations of electricity, al-Nasiriyya, May 9, 2003.

102 BLU stands for “bomb live unit” and is often used to designate the submunitions in cluster munitions.

103 Human Rights Watch interview with Hamid Kadhim, engineer in charge, al-Nasiriyya Electrical Power Plant, al-Nasiriyya,May 9, 2003; Human Rights Watch interview with `Ali Dakhil, security manager, al-Nasiriyya Electrical Power Plant, al-Nasiriyya, May 9, 2003. Dakhil was at the station the morning of the attack.

104 Human Rights Watch interview with Hassan Dawud, engineer, North Electrical Station 132, al-Nasiriyya, May 9, 2003.

105 Human Rights Watch telephone interview with senior CENTCOM official #1; Human Rights Watch telephone interview with senior CENTCOM official #2.

106 Human Rights Watch interview with Dr. `Ali `Abd al-Sayyid, director, al-Nasiriyya General Hospital, al-Nasiriyya, May 7, 2003.

107 Ibid.

108 Human Rights Watch, Needless Deaths in the Gulf War: Civilian Casualties During the Air Campaign and Violations of the Laws of War (New York: Human Rights Watch, 1991), pp. 180-85.

109 Human Rights Watch telephone interview with senior CENTCOM official #2. CBU stands for “cluster bomb unit.”

110 Human Rights Watch interview with custodian, St. George’s Episcopal Church, Baghdad, May 17, 2003.

111 In the 1999 Kosovo conflict, Radio Television Serbia, a central Belgrade broadcast facility, was targeted, and many civilians were killed. See Human Rights Watch, “Civilian Deaths in the NATO Air Campaign,” p. 26.

112 Human Rights Watch telephone interview with senior CENTCOM official #2.

113 “Bunker-Buster Dropped on Baghdad,” CNN.com, March 28, 2003, http://www.cnn.com/2003/WORLD/meast/03/27/sprj.irq.war.int.main/index.html (retrieved October 20, 2003).

114 Human Rights Watch telephone interview with senior CENTCOM official #2.

115 Human Rights Watch interview with U.S. Air Force officer, Baghdad, May 2003.

116 Human Rights Watch interview with Dr. Rasmi al-Rikabi, director, Baghdad Red Crescent Maternity Hospital, Baghdad, May 22, 2003. The occupation of the Baghdad Red Crescent Maternity Hospital by the Iraqi Intelligence Service represents a clear breach of the Geneva Conventions. It is an abuse of the emblem of the red crescent. Though the hospital had been evacuated two weeks prior to the attack, it was still regarded as a medical facility and still looked like a hospital. For more information on this and other cases, see additional discussion in the Conduct of the Ground War chapter below.

117 Human Rights Watch interview with Dr. Rasmi al-Rikabi.

118 For a more in-depth discussion of cluster munitions, see Human Rights Watch, “Fatally Flawed: Cluster Bombs and Their Use by the United States in Afghanistan,” A Human Rights Watch Report, vol. 14, no. 7 (G), December 2002. For a complete list of Human Rights Watch documents on cluster munitions, see http://www.hrw.org/arms/clusterbombs.htm.

119 Human Rights Watch, “Fatally Flawed,” p. 7.

120 The “skeets” of the CBU-105 are one exception to this rule. Used for the first time in Iraq, these warheads within a BLU-108 submunition are designed to guide themselves to armored vehicles. The new Sense and Destroy Armor Munitions (SADARM), artillery-launched submunitions, are another exception and operate in a similar way as the skeets.

121 Because of the imprecision and the fact that submunitions do not always reliably explode, multiple cluster munitions with overlapping footprints are often used in attacks. The use of multiple weapons increases the potential area of destruction in strikes and produces more unexploded submunitions that have aftereffects. Colonel Lyle Cayce confirmed that the U.S. Army used such techniques in Iraq. He said the footprint of a round of six Multiple Launch Rocket System (MLRS) rockets could have a radius of .6 miles (one kilometer). Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Colonel Lyle Cayce, staff judge advocate, Third Infantry Division, U.S. Army, Washington, D.C., October 17, 2003.

122 Human Rights Watch, “Fatally Flawed,” p. 8.

123 Ibid., pp. 8-9.

124 This figure does not include two CBU-107s, which contain steel rods rather than explosive submunitions. “Operation Iraqi Freedom—By the Numbers,” p. 11.

125 Ibid.

126 U.K. Ministry of Defence, “Operations in Iraq—First Reflections,” July 2003, p. 24. In April, a member of parliament reported use of sixty-six RBL-755s. Hansard (House of Commons), April 30, 2003: col. 392W.

127 Human Rights Watch, “Fatally Flawed,” pp. 6-7.

128 Ibid.

129 The AGM-154A contains 145 BLUs; the AGM-154B contains six BLU-108/B submunitions, which will be described later in the discussion of CBU-105s. FAS [Federation of American Scientists] Military Analysis Network, “AGM-154A Joint Standoff Weapon [JSOW],” June 27, 2000, http://www.fas.org/man/dod-101/sys/smart/agm-154.htm (retrieved October 23, 2003). For information on the TLAM with submunitions, see Raytheon (General Dynamics), “Directory of U.S. Military Rockets and Missiles: AGM/BGM/RGM/UGM-109 Tomahawk,” May 21, 2003, http://www.designation-systems.net/dusrm/m-109.html (retrieved October 23, 2003).

130 Human Rights Watch telephone interview with senior CENTCOM official #2.

131 Ibid.

132 Ibid.

133 Ibid.

134 Human Rights Watch interview with Nihad Salim Muhammad, Baghdad, May 17, 2003.

135 Human Rights Watch interview with Ibtisam Ibrahim Jassim, manager, al-Hadaf school, al-Hilla, May 20, 2003.

136 Human Rights Watch interview with Hamid Mahdi, al-Hilla, May 20, 2003.

137 Human Rights Watch interview with Ibtisam Ibrahim Jassim.

138 Human Rights Watch, “Fatally Flawed,” pp. 21-23.

139 Human Rights Watch confirmed the use of a CBU-103 in the strike on al-Hilla primary school because it found the casing at the site. It did not find a casing at the Hay Tunis site. It also found a CBU-103 casing in Sichir, a village near al-Falluja.

140 “CBU-97/B Sensor Fuzed Weapon System (SFW) (with BLU-108),” Jane’s Air-Launched Weapons, ed. Duncan Lennox (Surrey, U.K.: Jane’s Information Group, 1999).

141 “Operation Iraqi Freedom—By the Numbers,” p. 11. For information on the Rockeye, see ORDATA Online, “U.S. Bomb, Guided, Rockeye Munition (GRM),” February 4, 2002, http://maic.jmu.edu/ordata/srdetaildesc.asp?ordid=391 (retrieved October 24, 2003).

142 U.K. Ministry of Defence, “Operations in Iraq—First Reflections.”

143 Human Rights Watch, “Cluster Munitions a Foreseeable Hazard in Iraq,” A Human Rights Watch Briefing Paper, March 2003.

144 Protocol I, art. 51(4)(b).

145 Ibid., art. 51(5)(a).

146 Ibid., art. 51(5)(b).

147 U.S. Air Force, Bullet Background Paper on International Legal Aspects Concerning the Use of Cluster Munitions, August 30, 2001. This is an informal paper prepared by the office of the Air Force Judge Advocate General.

148 The Convention on Conventional Weapons (CCW), for example, defines “concentrations of civilians” as “any concentration of civilians, be it permanent or temporary, such as inhabited parts of cities, or inhabited towns or villages. . . .” Convention on Prohibitions or Restrictions on the Use of Certain Conventional Weapons Which May Be Deemed to Be Excessively Injurious or to Have Indiscriminate Effects, Protocol III (Prohibitions or Restrictions on the Use of Incendiary Weapons), 1980, amended December 21, 2001, art. 1(2).

149 Human Rights Watch, Cluster Bombs: Memorandum for Convention on Conventional Weapons (CCW) Delegates, December 16, 1999.

<<previous | index | next>> | December 2003 |