Key Individuals Named in this Report

I. Summary and Recommendations

II. Background: New Delhi and Bombay

III. Background to the Protests: Ratnagiri District

IV. Legal Restrictions Used to Suppress Opposition to the Dabhol Power Project

V. Ratnagiri: Violations of Human Rights 1997VII. Complicity: The Dabhol Power Corporation

VIII. Responsibility: Financing Institutions and the Government of the United States

Appendix A: Correspondence Between Human Rights Watch and the Export-Import Bank of the United States

Appendix B: Report of the Cabinet Sub-Committee to Review the Dabhol Power Project

Appendix D: Correspondence Between the Government of India and the World Bank

The drastic change in the government’s position was not lost on the Indian public, and on April 8, 1996, the Center for Indian Trade Unions (CITU) and an energy analyst, Abhay Mehta, filed a public interest litigation against the government and the company.54 The petition alleged that the reported clearances required for the project were not obtained; that since the project had been renegotiated, it had to obtain new licenses and clearances; and that “having charged the Dabhol Power Company and Enron with fraud, misrepresentation, corruption and bribery, it was not open to the Government of Maharashtra to negotiate and purport to contract with the said DPC/Enron.”55 Vivek Monteiro, a representative of the CITU, told Human Rights Watch the justification for the writ petition:

The CITU/Abhay Mehta petition in the Bombay High Court challenged the project on economic issues. Namely that it was unsustainable, violated laws in many ways, obtained government clearances by submitting unfeasible or fraudulent documents. It is a complextechnical matter. CITU was concerned about the high cost of power associated with the project.56

The petitioners’ first problem was an inability to obtain counsel for the petition. According to Monteiro, “It was hard to find a lawyer because Enron had retained or briefed every major lawyer in Bombay.”57 Representing the plaintiffs would thus be a conflict of interest. Finally, the petitioners obtained the services of Sunip Sen, a commercial lawyer practicing in the Bombay High Court. Sen told us:

I got involved because they found me. Apparently Enron placed all the leading lawyers in Delhi and Bombay on retainer, so the petitioners could not find representation. I am a commercial lawyer and did not really do public interest litigation. I like to stay neutral and do not want to be seen by the court as just a public interest lawyer.58

After five days of oral arguments, the case was accepted on April 26, 1996 by Justice B.N. Srikrishna, a well-known judge who had led the investigation into the role of the Shiv Sena and BJP during the Bombay riots in 1992-1993.59

The same day that Justice Srikrishna accepted the case, the lawyers for Enron petitioned the chief justice of the High Court, M.B. Shah, to expedite the case and transfer it from Srikrishna to a two-judge division bench, whose ruling could not be appealed. The rationale for the petition was that every day, the company was losing approximately $269,000 because work had stopped.60 Less than a week later, on May 2, an administrative order was issued, stating that the chief justice had ordered all public interest litigations to be given to division benches.61 Sen, the plaintiffs’ lawyer, told us:

The chief justice cannot transfer the case to a division bench; the case would first have to be referred to the chief justice by Srikrishna, which it was not. This was clearly interference by Shah through administration of a judicial order. A High Court judge’s decision can only be reversed by an appeal, which did not happen. A High Court order cannot be changed by legislation, either. There are plenty of Supreme Court rulings on this. This was blatantly irregular.62

Vivek Monteiro also recalled the incident and told Human Rights Watch:

Initially, Justice Srikrishna got the case and accepted the petition. The same evening, Enron’s lawyers go to the chief justice, M.B. Shah, and lobby to have the case transferred to [the two-judge panel of Justices] Seraf and Rane. Enron claimed that if Srikrishna hears the case, it will cost Enron 86 lakhs per day in project costs, but when the case was transferred, they dropped this argument. It is very uncommon to have a case switched like that. It is extremely rare, basically unheard of, for a chief justice to overrule a High Court judge without conducting a separate hearing on the matter.63

The order to transfer public interest litigations to a division bench created an uproar among High Court lawyers. Initially, lawyers considered appealing the decision to the court, but they declined to do so for various reasons: the court was on a five-week recess, and challenging the chief justice would have ramifications on future cases.

The case was transferred to Justices B.P. Seraf and M.S. Rane. On June 3, the two-judge court told the petitioners that they could amend their petition so that the court could examine all the aspects of the project: alleged corruption, the price of power, the lack of transparency, and whether the company had obtained the proper clearances and licenses for the project. CITU regarded this as evidence that Justice Seraf was positively disposed toward their petition, according to Sen.64

Justice Seraf gave the petitioners three days to amend their petition. The plaintiffs submitted their amended petition on June 6. The lawyers for the Dabhol Power Corporation, however, asked for three weeks to reply to the petition, whichwas granted by Seraf. In early July, the lawyers for the government of Maharashtra asked for more time, and a hearing was set for the end of July.65

Following the petitioners’ submission of the amended petition, Seraf ruled that because all the old issues were raised, the case was barred by res judicata. Although it was Justice Seraf who had asked that the petition be amended, he said on the record that the request came from Sen. According to Sen, Justice Seraf also asked Sen not to argue corruption but then said the plaintiffs chose not to argue corruption and therefore, had provided no evidence of it. When Seraf heard the case, he also barred more than 1,200 pages of the evidence that the plaintiffs had submitted to support their allegations. As a result of this ruling, the evidence—more than 1,200 pages—could never be used against the government or the company in any future Indian court case because Seraf had barred it under res judicata.66

The government’s position was particularly weak on the corruption issue. The government had previously filed a suit against the company and had engaged in arbitration on the grounds that the contract with the company was illegal because bribery had been used to secure the contract. During the CITU case, however, the government reversed its position and claimed it had no evidence of corruption and had only raised the issue to extract concessions from the company. The petitioners argued that this statement amounted to an admission of prior perjury, since the government had initiated court and arbitration proceedings alleging corruption and was now in another judicial proceeding claiming to have lied about those allegations.

Ultimately, on December 12, 1996, Justices Seraf and Rane dismissed the petition on the grounds that the information was old; that the petitioners had waited too long to file their case; and that this agreement was outside the purview of judicial scrutiny. They refused to rule on the perjury or corruption issues, thereby avoiding a ruling on the government’s credibility or on the larger issue of whether officials had been influenced through bribery. Along with the toothless ruling, however, Seraf and Rane issued a scathing critique of the government. Seraf and Rane wrote:

[W]e do find that the statement of the State Government made before this court to the effect that corruption was never alleged by it at any time except in the plaint in the suit and in the submissions before the arbitrators is factually not correct. We have once again glanced throughthe Munde Committee report and the speech of the Chief Minister to verify the above claim. We find enough indications in the Munde Committee report which suggest corruption by those who were responsible for the deal and the PPA...

The message of corruption, bribery and fraud is eloquent in the above statements. We are really amazed at the bald statements made by the Government in support of its actions from time to time. When it wanted to scrap the project and decided to scrap it, it boldly said everything which it felt necessary to support the same. It talked of lack of competitive bidding and transparency, the speed and haste in finalising the project. It also condemned those who were responsible for the deal. It went to the extent of filing suit in this Court and made all possible statements and allegations it thought necessary to get the PPA declared null and void by the Court. It worked the same way when it wanted to stall the arbitration proceedings. But once it decided to revive the project, it acted in the very same manner in which its predecessors in office had done. It forgot all about competitive bidding and transparency. The only transparency it claims is the constitution of the negotiating team. The speed with which the negotiating group studied the project, made a proposal for renegotiation which was accepted by Dabhol, and submitted its report is unprecedented...The Committee, we are told, examined the project, collected data on various similar other projects as well as internal bids including data on a similar project executed by Enron in the U.K., held considerable negotiations, settled the terms of revival of the project, got the consent of Enron...and submitted its exhaustive report along with data and details to the Government of Maharashtra on 19th November, 1995, just 11 days after its formation...The speed at which the whole thing was done by the negotiating group is unprecedented. What would stop someone today, as was said by the Chief Minister in the context of the original PPA, “Enron revisited, Enron saw and Enron conquered—much more than what it did earlier.”

However, we need not go into all those aspects because that is outside the scope and ambit of the powers of judicial review... As indicated earlier, it is not within the domain of this Court in exercise of its power of judicial review to examine the merits of the Government. That will amount to sitting in appeal over governmental decision which is not permissible... In any event, one thing that is obvious is that at everystage, it is the common man who has been taken for a ride during elections by the Shiv Sena-BJP alliance by making Enron an election issue and a part of its election manifesto and after coming into power, by reviewing the project and branding it as anti-Maharashtra, anti-people, alleging corruption, bribery, fraud, etc., by scrapping the same and telling the people that the promise made to them to scrap the project had been fulfilled. When the government decided to revive the same, it came out with a different statement that it had succeeded in snatching some concessions from Enron.67

The court also criticized Enron/DPC for its conduct throughout the process. Continually, the company claimed that it had been unjustly maligned while it was providing a service to the Indian people and was forced to spend millions of dollars “educating” Indian officials and the public on the merits of the project. In response to these claims, the court stated:

We have also given our careful consideration to the submissions... that Enron has been victimised for no fault of its own. We are, however, of the opinion that to some extent, “Enron” is also responsible for vitiating the atmosphere and for the anti-Enron campaign. In our opinion, the multinationals who want to invest in developing countries should not indulge in tall talks about educating the people of those countries. The decision of multinationals to invest in that country is based on the security of its investment and lucrative returns on the same. It is not activated by the desire to help the resource-starved nations. They do no charity. They move out of their country for greener pastures or better returns. They should, therefore, act and behave like an investor or an industrial house and not as a Government.68

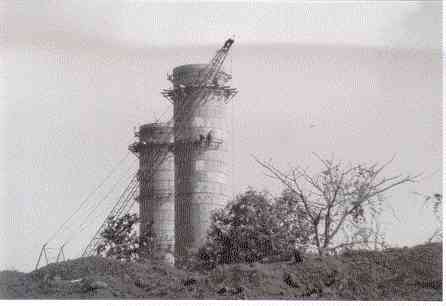

In the end, none of the issues that formed the basis of opposition to the project were adjudicated in the courts. The project, although suspended for eight months, was allowed to start construction. The petitioners, dissatisfied with Seraf’s ruling, filed a “Special Leave Petition” with the Supreme Court of India in an attempt to appeal. The court accepted the petition but ruled that it would only look into the conduct of the state government and would not examine the agreement between thecompany and the central government or allegations of corruption. At the time of this writing, that case is still pending.

Without any judicial or governmental recourse, the public, specifically those organizations and individuals opposed to the project and the manner in which it was negotiated and implemented, expressed their opposition to the company through protests in the district where the project was located (See Section V). The state, in turn, committed human rights violations to suppress opposition to the project. In this context, a statement in Seraf and Rane’ final ruling was particularly telling:

This case has highlighted to the people as to how, even after 50 years of independence, political considerations outweigh the public interest and the interest of the State and to what extent the Government can go to justify its actions.69

53 Mark Nicholson, “Dabhol Plant Finally Gets Green Light,” Financial Times, January 9, 1996.

54 This was the last of fourteen court cases filed against the project by various individuals, NGOs, and political parties. All of the previous cases were dismissed.

55 Center For Indian Trade Unions and others vs. The Union of India and Others, Special Leave Petition filed in the Supreme Court, p. B.

56 Human Rights Watch interview with Vivek Monteiro, Bombay, January 28, 1998.

58 Human Rights Watch interview with Sunip Sen, Bombay, February 4, 1998.

59 For more information on the Srikrishna investigation and the Bombay riots, see “India: Communal Violence and the Denial of Justice,” a Human Rights Watch Short Report, April 1996. Justice Srikrishna released his report into the riots in February 1998. The report was more than 700 pages long and indicted leaders of the Shiv Sena in promoting violence against Muslims.

60 Human Rights Watch interview with Sunip Sen.

61 Hutokshi Rustomfram, “Pulling the Rug to Spread the Carpet: The Enron Litigation,” The Lawyers Collective, Bombay, November 1996, p. 7.

62 Human Rights Watch interview with Sunip Sen.

63 Human Rights Watch interview with Vivek Monteiro.

64 Human Rights Watch interview with Sunip Sen.

65 “Pulling the Rug to Spread the Carpet...,” p. 7.

66 Human Rights Watch interview with Sunip Sen.

67 Judgement of Justice B.P. Seraf and M.S. Rane on Writ Petition 2456 of 1996, Center for Indian Trade Unions and Others vs. Union of India and others.

69 Judgement of Justice B.P. Seraf and M.S. Rane on Writ Petition 2456 of 1996.