“I Lost Everything”

Israel's Unlawful Destruction of Property during Operation Cast Lead

Summary

|

This report documents 12 cases of unlawful destruction of civilian property by the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) in Gaza during Operation Cast Lead from December 27, 2008 to January 18, 2009. These cases describe instances in which Israeli forces caused extensive destruction of homes, factories, farms and greenhouses in areas under IDF control without any evident military purpose. These cases occurred when there was no fighting in these areas; in many cases, the destruction was carried out during the final days of the campaign when an Israeli withdrawal was imminent.

In the cases documented in this report, the IDF violated the prohibition under international humanitarian law – the laws of war – against deliberately destroying civilian property except where necessary for lawful military reasons and the ensuing civilian harm is not disproportionate. This report does not address civilian property damaged or destroyed during immediate fighting; such destruction may or may not be lawful, depending on the circumstances.

The available evidence indicates that the destruction in each of the 12 cases documented in this report was carried out by the IDF for either punitive or other unlawful reasons. Human Rights Watch found – based on visits to each site, interviews with multiple witnesses, and the examination of physical evidence – that there were no hostilities in the area at the time the destruction occurred. In seven cases, satellite imagery of the area was available during the fighting, and corroborated witness accounts that large numbers of structures were destroyed shortly before Israel announced a ceasefire and withdrew its forces from Gaza.

Two factors are especially relevant to the ongoing impact of this destruction today, some 15 months after the conflict ended.

First, Israel's comprehensiveblockade of the Gaza Strip, imposed since June 2007, has prevented reconstruction of private property and public infrastructure after the conflict. The blockade continues to affect the lives of the civilian population, including those whose losses are documented in this report. UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon noted in late March 2010 that Israel had allowed imports of cement for several repair projects, including 151 housing units, but these imports were “a drop in a bucket” compared to housing needs, and Israel continued to restrict or bar the entry of many essential goods including materials needed for reconstruction. The media and humanitarian agencies reported in March that many goods were entering Gaza through smuggling tunnels beneath the southern border with Egypt, and many damaged buildings had been at least partially repaired with bricks made from smuggled cement and recycled concrete rubble. However, in the areas of Gaza where the vast majority of homes were completely destroyed during the conflict in December 2008 and January 2009 – including areas addressed in this report – there has been virtually no reconstruction of destroyed buildings, indicating that the cost of reconstruction materials under the blockade remained prohibitive for Gaza’s residents, more than three-quarters of whom live under the poverty line (as defined by international standards). That poverty is often a product of or aggravated by the blockade. Israeli officials insist that the blockade—which had already degraded humanitarian conditions in Gaza before Operation Cast Lead—will remain in place until Hamas releases Staff Sgt. Gilad Shalit, the Israeli soldier captured in June 2006, rejects violence, and fulfills other political conditions. The blockade, which is supported by Egypt at Rafah's Gaza border, amounts to a form of collective punishment of Gaza's 1.5 million civilians in violation of international law.

Second, the inadequate steps that Israel has taken to investigate alleged violations of the laws of war committed during Operation Cast Lead and to bring to justice those found to be responsible compound the violations documented in this report. As of March, Israeli military police had opened 36 criminal investigations, which included interviewing Palestinian witnesses, leading to the sentencing of one soldier who stole a credit card and indictments of two others for endangering a child at a checkpoint. The IDF has undertaken scores of military “operational debriefings” and several broader inquiries, including one focused on the issue of property destruction, but none took any testimony from Palestinian witnesses or victims. The IDF disciplined four soldiers and commanders, one for destroying property, but released only partial information about the circumstances. Notably, Israel has not conducted thorough and impartial investigations into whether policy decisions taken by senior political and military decision-makers including pre-operation decisions led to violations of the laws of war, such as the destruction of civilian infrastructure. (Human Rights Watch is not aware of any meaningful steps by Hamas authorities to ensure accountability for serious violations; a Hamas report released in January which purported to exonerate Palestinian armed groups for laws-of-war violations lacked credibility.)

The laws of war prohibit attacks on civilian objects, including houses and factories, unless they are a military objective. A military objective is anything that provides enemy forces a definite military advantage in the circumstances ruling at the time. Thus, even though a residential home is presumed to be a civilian object, its use by enemy fighters for deployment or to store weaponry or in the event it provides cover for advancing enemy forces, will render it a military objective and subject to attack or destruction. Even an unoccupied civilian structure can be a military objective – such as a house blocking the line of fire to an enemy position – and subject to lawful attack so long as its destruction cannot reasonably be expected to cause harm disproportionate to the anticipated military gain. Under the Fourth Geneva Convention, applicable during occupations, the extensive destruction of property “carried out unlawfully and wantonly” and not justified by military necessity, is a grave breach of the Geneva Conventions, and can be prosecuted as a war crime.

This report examines incidents of destruction that suggest violation of the laws-of-war prohibition of wanton destruction. This report does not necessarily document all instances of unlawful property destruction; our research was limited by practical constraints of time and resources. Rather, Human Rights Watch examined cases of property destruction that seemed particularly difficult to justify, such as when Israeli forces were in control of an area, there was no active fighting there, and the property was destroyed without any apparent lawful military justification. We deliberately did not pursue cases in which the destruction was not extensive, or the evidence suggested any possibility that Israel’s destruction of the property in question could have been militarily justified, based on mistaken information, or a consequence of fighting in the immediate vicinity. Similarly, we did not investigate Israeli conduct when the structures at issue may have been used by Hamas to store ammunition or military equipment or to set booby-traps, or when property was destroyed to permit the movement of Israeli forces because adjoining roads were mined and impassable.

Because of the limited number of cases examined, we cannot claim that the incidents examined in this report are representative of a broader pattern, but instead address them because they are troubling in their own right. Further inquiry is required to determine whether they were part of a broader policy or practice.

Extensive, Unnecessary Destruction

Human Rights Watch documented the complete destruction of 189 buildings, including 11 factories, 8 warehouses and 170 residential buildings, leaving at least 971 people homeless. The 12 incidents documented in this report account for roughly five percent of the homes, factories and warehouses destroyed in Gaza during the conflict. Overall, some 3,540 homes, 268 factories and warehouses, as well as schools, vehicles, water wells, public infrastructure, greenhouses and large swathes of agricultural land, were destroyed, and 2,870 houses were severely damaged. Our conclusions about the unlawfulness of the destruction of property are limited to the incidents we investigated in depth. Israel should thoroughly investigate these cases – including the lawfulness or unlawfulness of any relevant policy decisions – and punish persons found responsible.

Residents of neighborhoods we investigated fled or were ordered to leave their homes by Israeli troops, and returned after the war’s end to find their previously undamaged or moderately damaged homes destroyed and their vehicles demolished. In these cases, all evidence points to the destruction being carried out by Israeli forces. In the cases we examined in the neighborhoods of Izbt Abd Rabbo, Zeitoun, and Khoza’a, virtually every home, factory and orchard had been destroyed within certain areas, apparently indicating that a plan of systematic destruction was carried out in these locations.

The destroyed industrial establishments that Human Rights Watch investigated include a flour mill, juice and biscuit plants, and seven concrete factories. At all the concrete factories that we examined, tanks or military bulldozers destroyed or badly damaged every cement-mixing truck, cement pump truck and other vehicles on the property. As noted, during Operation Cast Lead, Israel could have lawfully attacked otherwise civilian objects if they were making an effective contribution to Palestinian armed groups’ military action and their destruction offered a definite military advantage at the time. For example, if armed groups had commandeered concrete factories during the fighting and were using the concrete produced to build or repair military objects like bunkers, such factories could have been legitimate targets for Israeli attacks. However, Gaza’s concrete factories were unable to operate at all prior to and during the war because they had run out of cement, which they must import due to their lack of capacity to produce it. There is no evidence that any of the cement and concrete factories in Gaza contributed to the military efforts of Palestinian armed groups during the fighting.

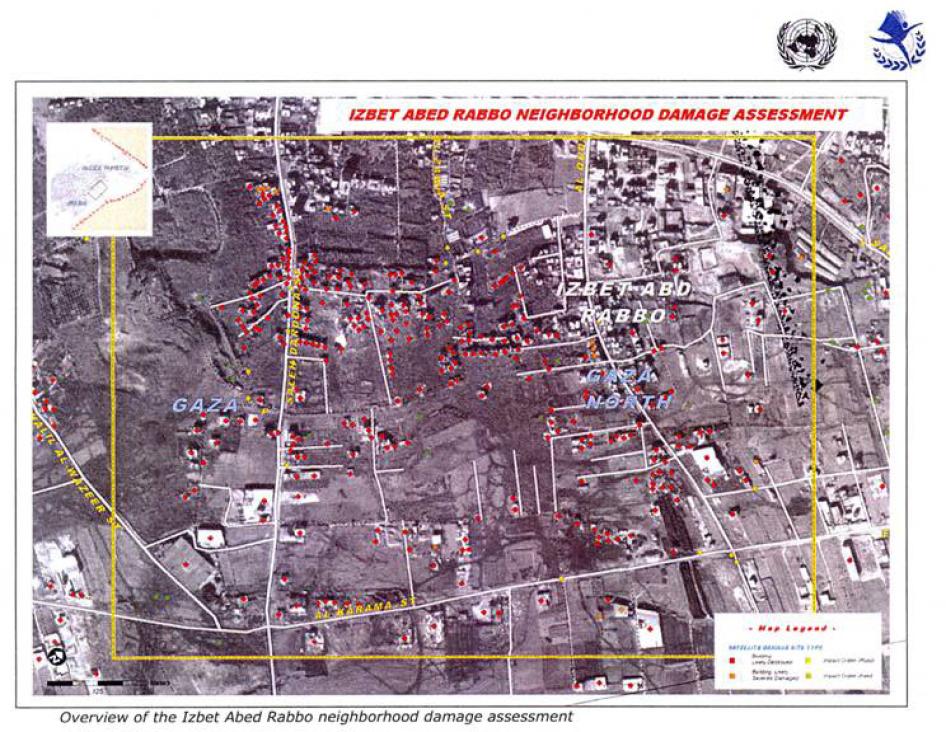

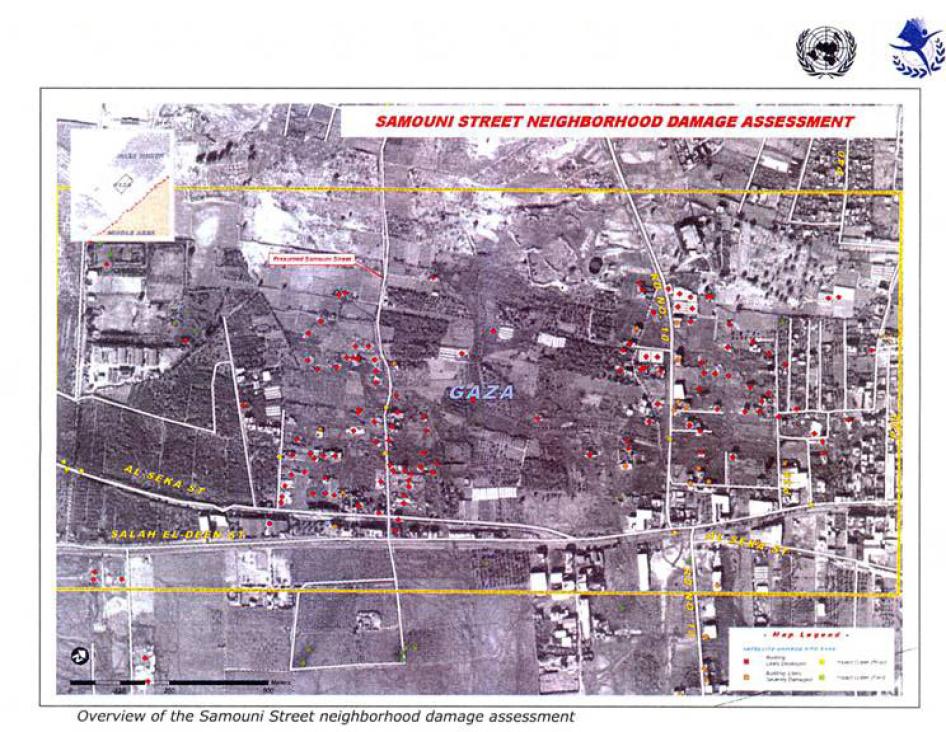

Satellite imagery taken at intervals during the conflict shows that in several neighborhoods Israeli forces destroyed property in areas where they had established control and immediately prior to their withdrawal from Gaza on January 18. In Izbt Abd Rabbo, satellite imagery shows that only 11 buildings were destroyed or severely damaged between December 27, 2008 and January 6, 2009, but that 330 buildings were destroyed or severely damaged from January 6 to 19 – a thirty-fold increase in destruction that occurred after the IDF had apparently established control of the area. In the Zeitoun neighborhood, satellite imagery shows that 43 percent of the destruction of buildings and greenhouses occurred during the last two days of the war, while only three percent of the destruction occurred during the preceding six days. This evidence is consistent with witness accounts that large-scale destruction occurred after the IDF had already established control of the area and there was no ongoing fighting.

An internal IDF investigation completed in April 2009 (which did not examine individual incidents of destruction or consider testimony from Palestinian witnesses) “confirmed that although relatively extensive damage was caused to private property” in Gaza, the IDF’s destruction of civilian property was lawful because Hamas used civilian infrastructure for military purposes by deploying fighters, weapons, booby-traps, and digging tunnels in houses, factories and mosques. The Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs stated in July 2009 that “IDF forces demolished structures that threatened their troops and had to be removed,” including (1) houses used by Hamas for military purposes during the fighting; (2) other structures “used by Hamas operatives for terrorist activity”; (3) structures whose total or partial destruction was imperatively required by military necessity, such as the movement of IDF forces; (4) “agricultural elements” used as cover for Hamas tunnels and infrastructure; and (5) buildings next to the security fence between Gaza and Israel that Hamas used for operations against IDF forces or for digging tunnels into Israeli territory.

Incidents of property destruction that fell into these categories would constitute lawful attacks on military targets. However, these categories do not account for any of the incidents of large-scale destruction of civilian property documented in this report. The Israeli government has published the results of a military probe into one case documented in this report, which found an attack on a flour mill to be lawful. The probe’s conclusions, however, are contradicted by available video and other evidence. (IDF lawyers told Human Rights Watch that the case could be reopened if new evidence was presented. In late March, Israel announced that it had approved cement imports to repair the flour mill.) The IDF has not provided explanations for the other 11 incidents that Human Rights Watch documented. Israel should conduct thorough and impartial investigations into these incidents and determine whether the incidents were lawful and, if not, if they reflected official policy.

During the IDF offensive in Gaza, Hamas and other Palestinian armed groups used civilian structures to engage Israeli forces and to store arms, according to news reports, video and photographic evidence. They also booby-trapped and dug tunnels under civilian structures. Human Rights Watch documented that armed groups fired rockets from populated areas; property damage caused by counter-strikes against the attacking forces could have amounted to lawful “collateral damage” (see Legal Obligations). Armed groups may also have been responsible for damage to civilian property in cases in which IDF attacks triggered secondary explosions of weapons or explosives, stored by armed groups, which damaged nearby structures. The IDF has published video footage that appears to show several such incidents.

However, in the 12 incidents examined in this report, extensive investigations revealed no apparent lawful military justifications for the destruction. The IDF was not engaging Palestinian forces at the time they destroyed the property – fighting had stopped – and in most cases the destruction of the property occurred after the IDF had eliminated or dispersed Palestinian fighters in the area and consolidated its control, such as by occupying houses, stationing tanks in streets or on nearby hills, and undertaking continuous surveillance from manned and unmanned aircraft. The possible future military use by armed groups of some civilian structures in these areas – such as to set booby-traps, store weapons, or build tunnels– cannot justify the wide-scale and at times systematic destruction of whole neighborhoods, as well as of factories and greenhouses that provided food and other items essential for the well-being of the civilian population.

For example, in Izbt Abd Rabbo, Human Rights Watch documented the complete destruction of 45 residential structures, which had housed at least 287 people, on or near the neighborhood’s main road during Operation Cast Lead. (Satellite imagery shows that a total of 341 buildings were destroyed in the area.) Fifteen industrial establishments in the area east of the neighborhood were also destroyed. According to separate individual interviews with 17 residents, including residents who were ordered to leave their homes by IDF soldiers or whom the IDF used as “human shields,” the vast majority of the destruction that this report documents in Izbt Abd Rabbo took place after January 7, by which point the IDF exercised control over the neighborhood.

In cases that Human Rights Watch examined in agricultural areas of Zeytoun, south of Gaza City – which represent a fraction of the total destruction in the area – residents said that at least 193 people had lived in residential buildings that were destroyed during the war. The accounts of residents suggest that Israeli forces inflicted extensive damage to buildings and land there in the early days of the ground offensive, but that they did not destroy most houses in these areas until after January 7, when they had already occupied these areas and almost all residents had fled. Many of the Zeytoun residents with whom Human Rights Watch spoke said that they left these areas after their homes had been shelled or hit with small-arms fire or they were ordered to leave by IDF soldiers. When they returned to the areas after the war, they said, they found the buildings had been bulldozed or destroyed with anti-tank mines. Human Rights Watch also observed bulldozer tracks in destroyed agricultural areas. In each incident we investigated, including where destruction occurred after residents and witnesses had left the area, Human Rights Watch cross-checked available reports to determine whether Palestinian armed groups counter attacked the area after the IDF gained control over it. In some cases, Israeli forces engaged and killed Palestinian fighters in areas where destruction occurred after residents and witnesses had left, but there is no evidence that the fighting caused or could in any way account for the extensive destruction of property we documented.

Public statements by some Israeli politicians suggest a willingness to conduct attacks against civilian infrastructure in Gaza to deter rocket attacks against Israel by armed groups. For example, Deputy Prime Minister Eli Yishai said at a conference on February 2, 2009 that “we have to determine a price tag for every rocket fired into Israel,” and recommended that “even if they fire at an open area or into the sea, we must damage their infrastructures and destroy 100 houses.” Because these statements both appeared consistent with some attacks during Operation Cast Lead and might be applied to Israel’s strategy in future conflicts, the Israeli government should publicly repudiate punitive attacks against civilian infrastructure.

Human Rights Watch documented that Palestinian armed groups in Gaza launched thousands of rocket attacks against Israeli population over the years in violation of the laws of war. During “Operation Cast Lead,” approximately 800,000 Israelis were within range of hundreds of rocket attacks, which killed three Israeli civilians and seriously injured several dozen others. Individuals who willfully conducted or ordered deliberate or indiscriminate rocket attacks on civilians are responsible for war crimes. However, laws of war violations by one party to a conflict do not justify violations by another party. The fundamental principle of distinction under the laws of war requires armed forces to distinguish between civilians and military objectives, and only target the latter, regardless of the conduct of the other side.

Inadequacy of Investigations

Israel is obliged under international law to investigate allegations of serious violations of the laws of war, including alleged excessive destruction of civilian property, and to prosecute those found responsible. To date, although Israel has conducted numerous “operational debriefings” and three dozen criminal investigations, it has not met that obligation.

The only reported penalty imposed for unlawful property destruction during “Operation Cast Lead” was an unknown disciplinary measure taken against one soldier. (The IDF has disciplined four soldiers and commanders for actions during “Operation Cast Lead,” but has published only limited information on the circumstances.) IDF lawyers told Human Rights Watch at a meeting in February 2010 that the incident involved “uprooting vegetation” in Gaza and that a disciplinary sanction was imposed immediately by the commander in the field, but they had given no details of the incident or the disciplinary measure.

Overall, it is unclear how many and which incidents the IDF has examined related to the unlawful destruction of property. The Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs stated in a report published in January 2010 that the IDF had opened 150 individual inquiries into alleged wrongdoing by Israeli soldiers during Operation Cast Lead, including 36 criminal investigations by military police. According to the report, none of the 36 criminal investigations involved property destruction or examinations of orders or strategies regarding property destruction. (The report said the incidents involved alleged shooting of civilians, using civilians as human shields, mistreatment of detainees and civilians, and pillage and theft.) The military police opened investigations into two incidents that apparently included property destruction as well as another offense; an Israeli government report published in July 2009 stated that military police had opened one investigation into “allegations regarding damage to property and pillage,” and another investigation into a case where a home was destroyed after an Israeli soldier allegedly shot four members of the family, killing two.

Lawyers with the IDF’s Military Advocate General’s office told Human Rights Watch in February 2010 that many of the cases of property destruction that Human Rights Watch documented are being probed either by “operational debriefings” or by “command investigations” – two kinds of probes that may differ in several respects, but are both conducted by IDF officers rather than by trained military police investigators and do not involve contacting Palestinian witnesses. The officers could not provide further information. The cases being probed, according to the IDF lawyers, include the destruction of the Abu Jubbah cement factory, the Wadiyya Food Factory, and areas of the neighborhoods of Khoza’a, Zeytoun and Abd Rabbo. An inquiry into damage to the El Badr Flour Mill has ended, and concluded there was no wrongdoing by the IDF. With the exception of the flour mill case, which according to an Israeli report the IDF learned about on September 15, 2009 with the publication of the report of the UN Fact Finding Mission on the Gaza Conflict, it is not clear when the IDF initiated these inquiries. Human Rights Watch wrote to the IDF detailing all the incidents in the present report on August 21, 2009 (see Annex A) and received a response on September 8, 2009 (see Annex B).

In addition to the probes the IDF has opened into these individual incidents, the IDF also examined the destruction of civilian structures in one of five broad “command investigations” into issues from the Gaza operation. The relevant IDF command investigation, conducted by a colonel, focused on “issues relating to the infrastructure operations and the demolishing of structures by the IDF forces during the ground operations phase of Operation Cast Lead.”

According to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the relevant IDF command investigation examined:

a. Orders and instructions given and determined by different command levels (from the headquarters to the ground forces, before and during the operation), regarding the destruction of buildings and infrastructure. b. Extent of destruction of buildings and infrastructure in the different areas, divided in accordance to: stages of the operation, operating units, types of buildings or infrastructure that were damaged, purposes of destruction, the manner in which the destruction was carried out (via engineers/method of destruction/verification of evacuation of residents) and whether the destruction was planned or spontaneous by decisions which were taken in the field in ‘real time’. c. Intelligence and operational information regarding the nature of the enemy’s offensive and defensive methods, and with regard to infrastructure of the enemy that was identified and documented by our forces, which support the operational necessity of destruction.

Israel has provided no specific information on how the investigation was conducted. A report published by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in January 2010 stated that “the investigation did not deal with specific incidents alleged in complaints or reports.”

The investigation results, approved by IDF Chief of Staff Lt. Gen. Gabi Ashkenazi and published in April 2009, concluded: “In all of the areas in which the IDF operated, the level of damage to the infrastructure was proportional, and did not deviate from that which was required to fulfill the operational requirements.” The investigation blamed “the extent of damage caused to buildings” on “the extensive use by Hamas of those same buildings for terrorist purposes and targeting IDF forces.” The investigation noted that the IDF’s “written plans for the operation” did not sufficiently stress the need to minimize the damage to civilian property, but claimed that nonetheless, “the forces in the field understood” these limitations. Reports published by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in July 2009 and January 2010 reiterated these conclusions.According to the January 2010 report, Israel launched an additional 10 inquiries into incidents of property damage after becoming aware of them with the publication of the report of the UN Fact Finding Mission on the Gaza Conflict on September 15, 2009. The January 2010 report described the conclusions of probes into four cases of property damage discussed by the Fact Finding Mission; in none of these cases did the IDF find itself liable for laws of war violations. Human Rights Watch documented one of these incidents: the attack on the el-Bader flour mill, which is discussed below. A list of the other six incidents being examined has not been made public.

In January, Israel reportedly agreed to pay the UN US$10.5 million for the damage it caused to UN facilities during the war. A UN Headquarters Board of Inquiry led by Ian Martin investigated nine attacks that damaged UN facilities or killed or injured UN personnel, finding Israel responsible in seven cases and Palestinian armed groups in one case; the responsible party for the remaining attack could not be determined. Israel stated that the payment did not amount to an admission of wrongdoing.

Reconstruction Denied

Post-war reconstruction in Gaza has been greatly hampered by Israel’s continuing blockade (supported by Egypt) of the territory. Israel controls the Gaza Strip’s land, air, and sea access with the exception of a 15-kilometer border with Egypt. Israel’s strict blockade of Gaza has remained in place following the end of major military operations, exacerbating the effects of the wartime destruction. Since the end of the conflict, Israel has granted approval to a limited number of shipments of construction materials designated for specific projects. Israel allowed in only six truckloads of construction materials from January to May 2009, according to the United Nations, which noted that “the parallel figure during the same period of 2007, before the Hamas takeover of Gaza, was over 39,000 truckloads.” In June 2009, Israel allowed entry to 18 truckloads of cement and gravel (to expand the Palestinian side of the Kerem Shalom border crossing). In a significant positive development, Israel allowed the shipment of 100 truckloads of glass from December 2009 to February 2010, and reportedly approved a second shipment of window glass beginning on March 2, 2010, to be sold commercially. UN Secretary-General Ban Ki Moon informed the UN Security Council on March 24 that Israel had approved cement shipments to construct 151 housing units in Khan Younis, and to repair a number of structures damaged during “Operation Cast Lead,” including the Badr Flour Mill discussed in this report. However, Israel continues to deny entry to cement, iron bars, and other construction materials, on the grounds that Hamas could divert them for military purposes.

Israel may inspect goods entering and leaving Gaza, but restrictions should be for specific security reasons and should not be used to block basic goods and civilian necessities.

While Israel has consistently failed to provide specific security justifications for its refusal to allow many basic goods into Gaza, there are valid Israeli security concerns that Hamas could use cement to build strengthened military bunkers and tunnels. However, according to humanitarian aid organizations, Israel has refused to seriously discuss creating a mechanism that would allow the delivery of much-needed construction materials for civilian reconstruction projects in Gaza by ensuring the independent monitoring of the end-use of the materials. According to a March 2010 report prepared by a UK parliamentary delegation after a visit to Gaza, the “UN stresses that every single tile, pipe or bag of cement is tracked from the border crossing to its final use,” and noted that the UN had offered to allow Israel to install permanent remote visual monitoring of their housing projects, “in order to verify that all building materials were being used for their stated purposes.” Israel should seek to create a mechanism for the delivery of needed construction materials that would address these concerns as well as the severe impact of import prohibitions on thousands of civilians who remain displaced by the destruction of their homes. By denying entry to materials necessary for reconstruction, Israel is prolonging the post-war hardship of the civilian population.

Some reconstruction materials are reportedly among the goods smuggled into Gaza from Egypt via underground tunnels but are too limited in quantity and expensive to enable large-scale reconstruction. In March 2010, the price of smuggled concrete had reportedly fallen to 900 Israeli shekels (US $240) per ton from 4000 shekels (US $1080) per ton immediately after the conflict, but the price of smuggled metal reinforcing bars, which are also necessary for the type of home construction common in Gaza, remained high at 2000 (US $540) Israeli shekels per ton. Such prices evidently remain out of reach for persons whose homes were completely destroyed. According to the UN, approximately 80 percent of Gaza’s population is impoverished and dependent on food aid. Human rights and humanitarian workers in Gaza told Human Rights Watch that as of late March 2010, many local factories were producing concrete cinderblocks (or breeze blocks) by grinding down the rubble of destroyed buildings and mixing it with cement smuggled through the tunnels from Egypt, and that many of the partially destroyed buildings in Gaza’s cities and refugee camps had been at least partly rehabilitated with this material. However, they noted that there has been virtually no reconstruction in outlying areas where large numbers of buildings were completely destroyed, including the areas documented in this report.

As a result of the war and the ban on supply of reconstruction materials, thousands of Gazan families remain homeless. As of November 2009 – ten months after the war ended – the UN reported that more than 20,000 people still remain displaced, with children being among the worst affected. The more fortunate displaced are living with relatives or renting apartments; the less lucky still live in makeshift shelters inside their damaged homes. As of November, 120 families, including 500 children, were still living in tent camps set up as temporary shelters ten months previously, according to international humanitarian agencies.

The UN also remains unable to implement reconstruction plans. The UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA) reported in August that the blockade was preventing it from conducting an estimated US $43 million worth of needed repairs, including to 2,200 destroyed UNRWA-provided houses, as well as schools, sanitation facilities, warehouses, and other installations damaged during the war. UNRWA announced in December 2009 that it would resort to “compressed earth blocks” to build 122 planned homes for the displaced. (In addition, UNRWA began construction on several new housing projects with a total of 2,400 housing units prior to the siege in 2007, but has been unable to complete them due to the ban on construction materials.)

Many of the industrial establishments that Israeli forces destroyed had not been operating before the war for lack of supplies due to the blockade, but the destruction of these factories’ physical plant makes the rejuvenation of Gaza’s economy an even more remote prospect.

As with armed conflicts elsewhere, Human Rights Watch takes no position on the decision of either side in the recent Gaza conflict to resort to military force, whether to defend itself or to pursue other goals, but instead focuses on how the warring parties use military force, namely, whether they comply with the requirements of international humanitarian law. Just as Hamas should hold its serious abusers accountable, so Israel should hold accountable those responsible for serious laws of war violations, including those related to property destruction. Like Hamas, Israel should cooperate with international accountability mechanisms. And just as Hamas should immediately stop all rocket attacks on Israeli civilian areas emanating from Gaza, so Israel should urgently open Gaza’s borders to reconstruction materials and other essential supplies. The United States, the European Union and other allied states should urge both Israel and Hamas to abide by its legal obligations in these regards.

On September 15, 2009, the United Nations Fact Finding Mission on the Gaza Conflict, led by Justice Richard Goldstone, published a report that found evidence that both Israel and Hamas had committed war crimes and possible crimes against humanity. The report documented cases where Israeli forces allegedly engaged in “extensive destruction of property, not justified by military necessity and carried out unlawfully and wantonly,” and called on both sides to carry out credible investigations within six months. The United Nations Human Rights Council and General Assembly endorsed the report. On February 5, 2009 the UN Secretary-General reported to the General Assembly on steps taken by the Israeli and Palestinian authorities to investigate violations, as called for in General Assembly resolution A/RES/64/10, but concluded that investigations were ongoing and that “no determination can be made on the implementation of the [General Assembly] resolution by the parties concerned.” On February 26, the General Assembly approved resolution A/RES/64/254, reiterating its call for Israel and the Palestinian side to conduct credible investigations and requesting the Secretary-General to report on steps taken by both sides within five months, “with a view to the consideration of further action, if necessary, by the relevant United Nations organs and bodies, including the Security Council.”

The United States and the European Union are the international actors with the greatest leverage to press Israel to uphold its obligations under the laws of war. The United States supplied approximately $2.77 billion in military aid to Israel in 2009. Following the Gaza war, the European Union, Israel’s largest foreign trading partner, unofficially froze any upgrade in its relations with Israel, which are governed by an Association Agreement.

Recommendations

To the Government of Israel

- Conduct thorough and impartial investigations into alleged violations of international humanitarian law during the fighting of December 2008-January 2009 in Gaza. Make the investigation findings public and prosecute those responsible for war crimes in trials respecting international standards. Immediately lift the blockade of Gaza and facilitate the free flow of humanitarian aid and commercial goods, including materials urgently required for the reconstruction of destroyed civilian property, such as concrete and metal rods.

- Provide prompt and adequate compensation to the victims of laws-of-war violations in Gaza.

- Implement the findings and recommendations of the final report produced by the United Nations Fact Finding Mission on the Gaza Conflict.

- Review policy and tactical decisions made during Operation Cast Lead that may have led to unnecessary destruction of civilian property, with public findings and recommendations for minimizing such destruction in any future engagements.

To the Government of the United States

- Suspend shipment to Israel under the Foreign Military Sales Program of Caterpillar D-9 bulldozers, pending the conclusion of an official investigation into the IDF’s use of these bulldozers to destroy civilian property in Gaza in violation of the laws of war.

- Use the leverage that comes from the massive US military assistance to Israel to press Israel to :

- conduct a thorough, independent and impartial investigation into unjustified destruction of civilian infrastructure in the Gaza Strip during Operation Cast Lead, and compensate those unlawfully harmed; and

- open Gaza’s borders to allow for the entry of humanitarian aid and commercial goods needed for rebuilding.

To the European Union

- Under the leverage provided by the terms of the Association Agreement with Israel, the EU should press Israel to :

- conduct a thorough, independent and impartial investigation into alleged violations of the laws of war in the Gaza Strip during Operation Cast Lead, and compensate those unlawfully harmed; and

- open Gaza’s borders to allow for the entry of humanitarian aid and commercial goods needed for rebuilding.

To the United Nations Human Rights Council

- Review implementation of the Goldstone report by the parties to the conflict and UN bodies in future sessions of the Human Rights Council.

To the UN General Assembly

- Consider the UN Secretary-General’s report in response to General Assembly Res A/64/L.48, due by July 26, 2010, and, in case of continued failure by the parties to conduct impartial investigations and prosecute those responsible for serious laws-of-war violations, refer the situation to the Security Council.

To the UN Secretary-General

- Monitor and report to the General Assembly within five months (by July 26, 2010) on investigations conducted by the parties to the conflict as required by UN General Assembly resolution A/64/L.48, including an assessment of whether the steps taken meet international standards of promptness, thoroughness and impartiality.

- Should Israel and Hamas’s investigations continue to fall short of international standards for thoroughness and impartiality, refer the report of the UN Fact Finding Mission on the Gaza Conflict to the UN Security Council under article 99 of the UN Charter.

To the UN Security Council

- As it has done in response to other conflicts, call on the parties to the Gaza conflict to conduct thorough and impartial investigations into the allegations of laws-of-war violations by their respective forces, prosecute those responsible for serious violations, and compensate the victims.

- Await next steps by the UN General Assembly and in case of continued failure by the parties to conduct impartial investigations and prosecute those responsible for serious laws-of-war violations the Security Council should create its own independent committee of experts to monitor and report on progress made by the parties to conduct thorough and impartial investigations into alleged laws-of-war violations.

- If the parties continue to fail to conduct thorough and impartial investigations up to international standards refer the conflict to the prosecutor of the International Criminal Court.

Methodology

Human Rights Watch conducted research for this report in Gaza from April 8 to 19, 2009. A researcher entered Gaza via Egypt after Israeli authorities denied or failed to respond to six Human Rights Watch requests to enter Gaza via the Israeli crossing at Erez. The researcher conducted the research together with a Human Rights Watch consultant based in Gaza.

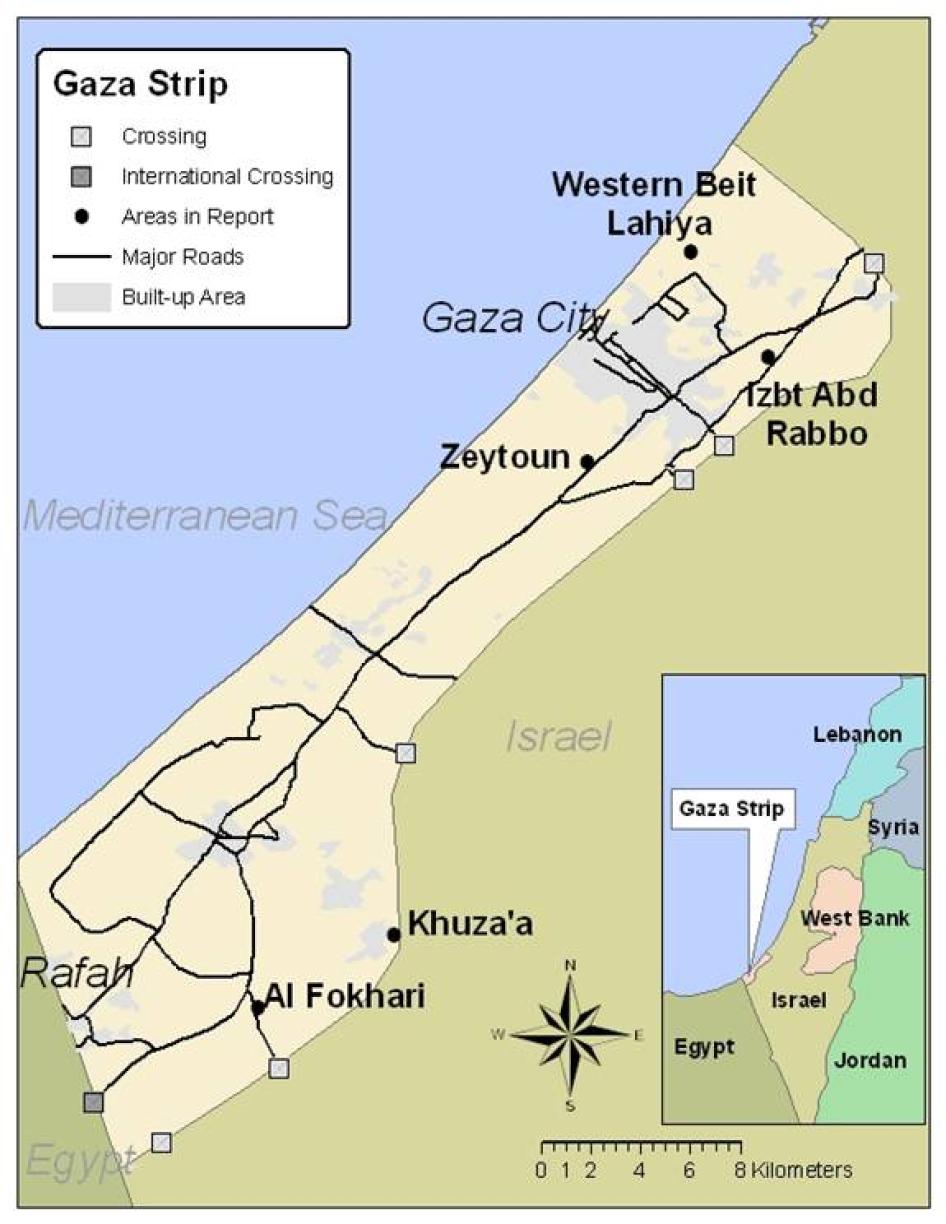

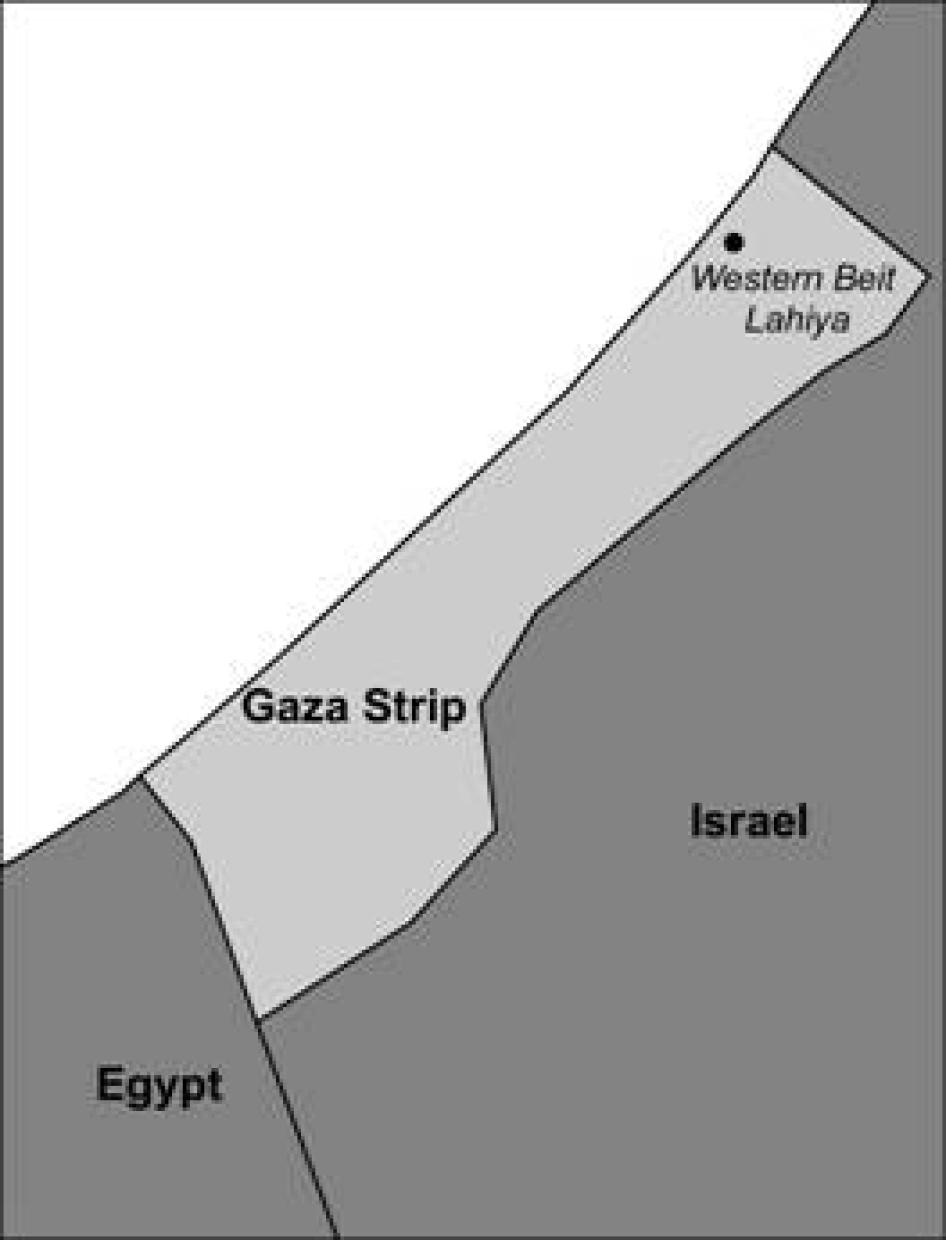

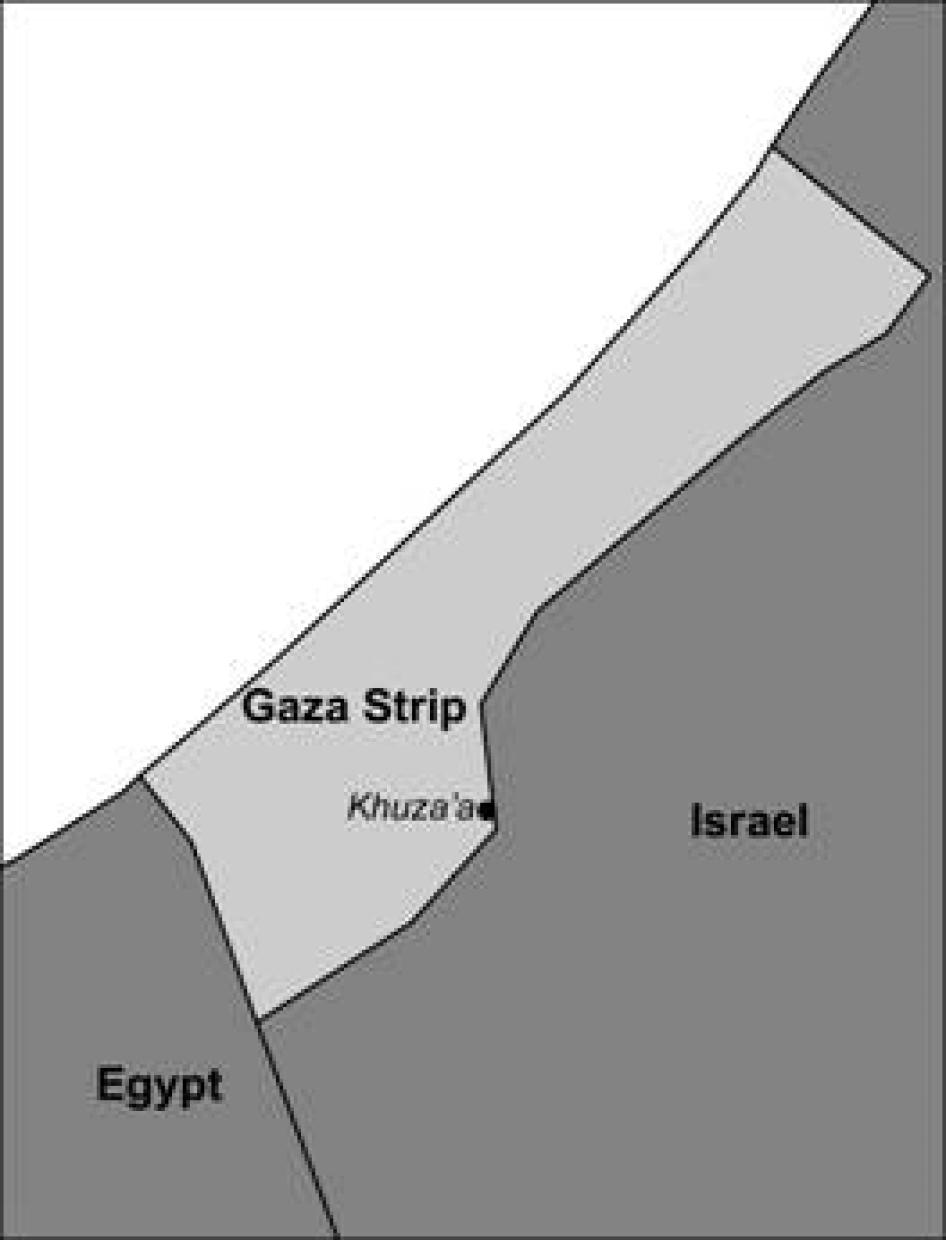

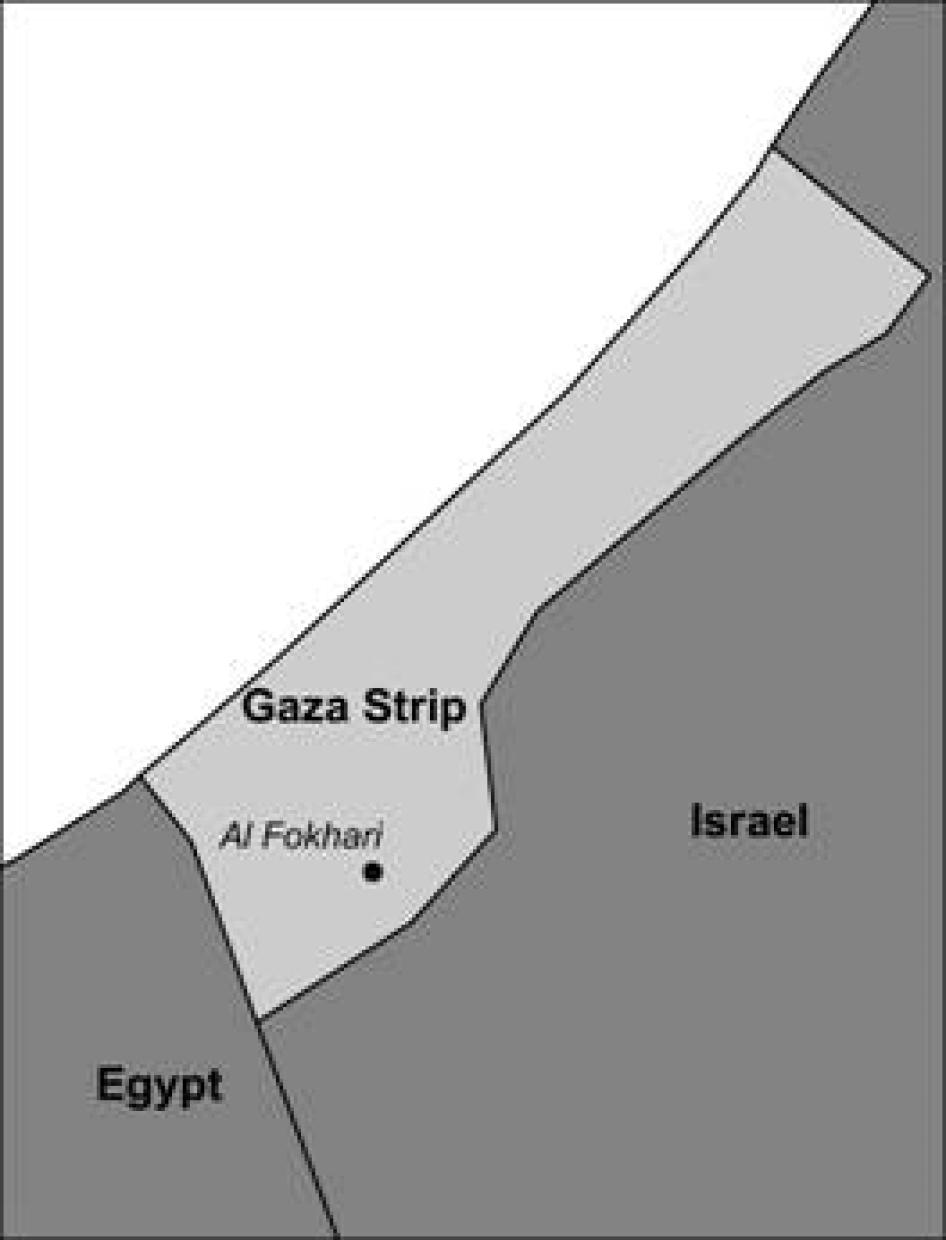

This report documents 12 incidents in which Israeli forces extensively destroyed or damaged civilian property in apparent violation of the laws of war. These incidents are drawn from four different geographical areas of Gaza – western Beit Lahiya in the northwest, Izbt Abd Rabbo in the northeast, Zeytoun in the north / central part, and Khoza’a in the southeast. We selected these cases by surveying the damage in Gaza, reviewing reports by the United Nations and humanitarian organizations, and considering accounts by the media and human rights groups.

Because the laws-of-war violation of wanton destruction certainly occurs in cases in which one party to a conflict destroys property extensively in an area over which it has effective control without a lawful military purpose, we focused our research on such relatively clear alleged incidents. In cases where initial information or further investigations raised the likelihood that the destruction of property was justified, we did not investigate further.

The laws of war provide that the determination of whether an incident of property destruction was lawful or unlawful must be based on whether it was reasonable for the responsible force to conclude – based on what was known or should have been known at the time rather than in hindsight – that the property was a valid military objective in the circumstances prevailing at the time, and that its destruction would not be expected to cause disproportionate civilian loss compared to the anticipated military gain. In each of the cases we document, the scale of the destruction strongly discounts the possibility that the property was destroyed reasonably, accidentally or based on the mistaken assumption it was serving a contemporaneous military purpose.

As noted, this report deliberately excludes cases where there was a lawful military necessary reason to justify the destruction of civilian property. We did not investigate cases including several reported instances where large-scale destruction was caused by aerial bombings, because of the presumed difficulty in determining whether or not individual aerial bombings of civilian structures were carried out with criminal intent or as part of a widespread attack. In three cases in which Human Rights Watch conducted preliminary research, it either appeared possible or we could not rule out that Israeli forces might have destroyed or damaged property out of military necessity or due to mistaken targeting or intelligence, and we therefore did not pursue those investigations any further or include them in this report; a fourth such case is mentioned in a footnote.

During the course of field research, Human Rights Watch conducted interviews with 94 residents in Gaza – the majority of whom had left their areas of residence before these were destroyed -- primarily in Arabic with an interpreter, as well as with a UN expert on unexploded ordnance in Gaza. These interviews were conducted individually and privately, unless otherwise noted. In addition, we conducted extensive on-site investigations, examining destroyed structures and the surrounding areas for signs of military activity and armed exchanges between Israeli and Palestinian forces. Human Rights Watch examined forensic evidence at the scenes, such as the remnants of anti-tank mines used as demolition explosives and debris from aerial bombardment, artillery fire, tank fire, and small arms fire, as well as tank and bulldozer tread marks. Lastly, Human Rights Watch examined satellite images provided by the United Nations Operational Satellite Applications Programme (UNOSAT), some of which are presented in the report. The images show physical destruction throughout Gaza at different phases of the campaign.

Human Rights Watch does not dispute that in some cases, damage to civilian structures was caused by explosions from booby-traps or secondary explosions due to weapons placed by Palestinian armed groups. However, no reports, media accounts or our own research indicated that explosive booby-traps planted by Palestinian armed groups or secondary explosions caused by weapons stored by these armed groups were responsible for any significant amount of the damage seen in Gaza. (In response to specific questions from Human Rights Watch, the IDF has not provided evidence or claimed that the 12 cases of large-scale destruction documented in this report were caused by Palestinian armed groups.)

On August 21, 2009, Human Rights Watch sent the IDF detailed questions about its policies on property destruction and the incidents documented in this report (see Appendix 1). In its response of September 8, 2009, the IDF referred Human Rights Watch to reports already published by the IDF and Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs (see Appendix 2). On November 23, 2009, Human Rights Watch requested a meeting with the IDF to discuss accountability measures taken with regard to alleged violations during “Operation Cast Lead,” including the incidents documented in this report. Members of the IDF Military Advocate General’s office and the Spokesperson’s office met with us on February 4, 2010. This report takes these meetings and Israeli documents as well as other official Israeli statements into account, citing them where relevant. It also cites the statements of Israeli soldiers who fought in Operations Cast Lead, as published by Breaking the Silence, an Israeli nongovernmental organization of IDF veterans.

Destruction of Property during the Conflict

On December 27, 2008, Israel launched what it called Operation Cast Lead. The stated aim of the military operation was to stop the ongoing rocket fire into Israel from Palestinian armed groups in Gaza. After a large-scale air campaign, the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) on January 3, 2009 launched a major ground offensive. Israeli troops began to withdraw from Gaza early on January 18. The IDF operations killed some 1,387 Palestinians, at least 762 of whom were civilians, according to a list of names published by the Israeli human rights organization B’Tselem.[1] Thirteen Israelis died during the fighting, three of them civilians.[2]

Beyond the loss of human life, the war in Gaza resulted in the destruction of thousands of private homes, as well as public infrastructure, factories, businesses and workshops, vehicles, and agricultural land and animals. The sheer extent of the destruction does not, in itself, indicate violations of international humanitarian law (the laws of war). However, Human Rights Watch’s investigation into 12 incidents found that in these specific cases the IDF destroyed extensive civilian property in apparent violation of the laws of war. We do not claim that these violations are typical of the destruction in Gaza generally – the lawfulness or unlawfulness of which must still be assessed. In conducting that investigation, Israel should examine whether any violations were due to policies adopted by the military or the government. Property may be destroyed only for imperative reasons of military necessity and in accordance with the rules of proportionality.

According to a joint survey by UN agencies, the fighting destroyed 3,540 housing units in Gaza and 2,870 sustained severe damage during Operation Cast Lead.[3] Fighting and destruction during the war caused displacement of more than 50,000 people.[4] As of March 2010, humanitarian workers in Gaza informed Human Rights Watch that several factories in Gaza were operating to produce concrete cinderblocks (or breeze blocks) by combining the pulverized rubble of destroyed buildings with cement smuggled through the tunnels from Egypt, and that some reconstruction of damaged homes using this material was underway in refugee camps and cities in Gaza.[5] However, these sources reported that the vast majority of destroyed homes, particularly in areas of Gaza that saw extensive destruction during the war like Izbt Abd Rabbo, have not been rebuilt or repaired. While the price of cement and metal bars smuggled into Gaza via tunnels had dropped to 900 Israeli shekels (US $240) and 2000 shekels (US $540) per ton, respectively, by March, these prices appeared to remain out of reach for the majority of Gazans whose homes were totally destroyed.[6] As of November, ten months after the war, at least 20,000 people remained displaced, in large part due to Israel’s ban on importing into Gaza construction material such as cement, needed to rebuild housing.[7] (According to a January 18, 2009 statement by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Israel permits “humanitarian aid” to enter Gaza, but “cement, sand, gravel and steel are not considered to be humanitarian aid.”)[8] The displaced have had no choice but to remain with their relatives, in rented apartments, in makeshift accommodations next to the ruins of their homes, or in tented camps. As of November, thousands of families continued to live in sections of badly damaged homes, and 120 families, including 500 children, were still living in tents provided ten months previously by international aid organizations. Intended as temporary accommodations, many of the tents are unfit for use in winter.[9] In December, the UN completed the first of 122 planned “compressed earth block” structures, intended to improve the lives of those still living in tented camps or in makeshift shelters near their damaged or destroyed homes.[10]

According to the UN Refugee Welfare Agency (UNRWA), which assists Palestinian refugees, wartime attacks destroyed public and service sector infrastructure, including government buildings, bridges and 57 kilometers of asphalt roads (and other roads), and damaged 107 UNRWA installations, almost 20,000 meters of pipes, four water reservoirs, 11 wells, and sewage networks and pumping stations.[11] Because the Israeli blockade had made building materials and supplies unavailable, as of August, the agency reported that it would not be able to conduct US$43 million worth of needed repairs to refugee shelters and UNRWA installations “damaged during Operation Cast Lead."[12] A report prepared for the UK parliament in March 2010 reported that UNRWA remained unable to complete several housing projects, comprising some 2,400 housing units, that had been on hold since June 2007 when Israel blocked shipments of construction materials after the Hamas takeover of Gaza.[13] On March 24, UN Secretary-General Ban Ki Moon informed the UN Security Council that Israel had approved shipments of cement sufficient to complete construction of 151 housing units near Khan Younis as well as repairing several facilities damaged during the conflict, including the Badr Flour Mill. While welcoming the step, Ban noted that “One hundred and fifty-one units amount to far less than 1 per cent of the needs in the shelter sector alone, to say nothing of other needs. I have informed Israel that we will come back with more far-reaching proposals.”[14]

Israeli attacks on Gaza’s electricity infrastructure caused an estimated $10 million in damage, according to Gisha, an Israeli nongovernmental organization; on January 3, the first day of the Israeli ground offensive, Israeli attacks “damaged and put out of commission seven of the 12 electrical power lines that connect Gaza to Israel and Egypt.”[15] On January 13, Israeli aircraft bombed a warehouse containing spare parts needed for repairs to the grid that it had recently allowed Gaza’s utility, GEDCO, to import.[16]

The military offensive destroyed 18 schools (including eight kindergartens) and damaged at least 262 other schools. In North Gaza alone, nearly 9,000 students had to relocate to other schools after their own schools were destroyed.[17]

The war destroyed 268 private business establishments in Gaza and damaged another 432, causing total damage estimated at over $139 million (after discounting for inflated claims), according to a preliminary assessment by a Palestinian group published in February.[18] A study of the industrial sector, published in March, reported that 324 factories and workshops were damaged or destroyed during the war.[19] These reports documented damage to physical structures, equipment and machinery, inventories of raw materials and finished goods, and in some cases, to electronic and paper documentation. As of December 2008, prior to Israel’s military offensive, approximately 4,000 employees worked in the establishments that were subsequently destroyed during the war. According to the Palestine Federation of Industries, a private sector umbrella group representing the industrial sector in Gaza, those employees’ jobs “provide[d] for more than 24,000 people who are now impoverished as a direct result of the war.”[20] As of January 2010, the UN reported, Israel continued to block or severely restrict the entry to Gaza of raw materials needed for industry, as well as spare parts for Gaza’s sanitation and electrical networks, hindering post-war reconstruction.

The construction materials sub-sector was particularly devastated. Human Rights Watch researchers did not survey all concrete ready-mix factories in Gaza, but at all seven of the factories we examined, every vehicle on factory grounds had been demolished, and many buildings and other pieces of equipment had been damaged or destroyed. A preliminary survey of the damage to Gaza’s industrial sector reported in February that the war destroyed or damaged 22 of Gaza’s 29 ready-mix concrete factories, causing an “85 percent loss in the sub-sector’s potential capacity” and an estimated $27 million in damages.[21]

Israel’s military offensive resulted in an estimated $268 million in losses to the agricultural sector. This includes $180 million in direct damage during the war to fruit, grain and vegetable crops, animal production, and infrastructure like greenhouses and farms, according to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). As OCHA noted, the severe damage to the agricultural sector is cause for concern for several reasons. First, agriculture plays a vital role in generating economic activity in Gaza, due to “the failure of other economic sectors (including industry) to function, owing to the closure of Gaza’s commercial crossings since June 2007.” In addition, agriculture is a “traditional shock‐absorber” and plays a critical role in protecting livelihoods, especially in rural areas, “for communities whose other social safety nets fail to operate.”[22] Agriculture is usually one of the few economic sectors that can recover quickly after a conflict, supplying needed food and jobs, but Israel’s continuing border blockade continues to exacerbate the damage done to the agricultural sector by the war, by making it extremely difficult to import materials to repair damaged infrastructure, new seedlings and farm animals, and many other necessary inputs from peat moss to heating gas for poultry farms that are difficult to obtain in Gaza.[23] According to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization, “almost all Gaza’s 10,000 smallholder farms suffered damage and many have been completely destroyed” as a result of the war.[24]

A Permissive, Destructive Policy

The conclusions this report draws relate to the unlawfulness of Israeli destruction of property in specific locations in Gaza and are based primarily on evidence gathered during investigations conducted in Gaza. In addition, the destruction we documented in these cases appears consistent with statements by Israeli politicians and military officials, and soldiers who participated in the Gaza conflict, which described two rationales for property destruction that conflict with the Israeli military’s obligations under the laws of war not to destroy property except for reasons of imperative military necessity and in accordance with the principle of proportionality.

First, statements by some Israeli politicians during and after “Operation Cast Lead” – the stated aim of which was to stop rocket attacks by Palestinian armed groups –suggest that a doctrine of punitive attacks intended as a deterrent against rocket attacks may have informed the conduct of the IDF in some cases where it destroyed property unlawfully. Then Foreign Minister Tzipi Livni reportedly stated on January 12, 2009, that “Hamas now understands that when you fire on [Israel’s] citizens it responds by going wild, and this is a good thing."[25] Livni said on January 19, 2009, the day after the conflict ended, that “Israel demonstrated real hooliganism during the course of the recent operation, which I demanded.”[26] Deputy Prime Minister Eli Yishai said at a conference on February 2, 2009 that “we have to determine a price tag for every rocket fired into Israel,” and recommended that “even if they fire at an open area or into the sea, we must damage their infrastructures and destroy 100 houses.”[27]

Such statements are consistent with a statement and an article published before the conflict by Israeli military officials that advocated a doctrine of punitive property destruction intended to deter armed groups from attacking Israel.While these statements focused on Israel’s strategy in a future large-scale conflict in Lebanon, they are consistent with the destruction Human Rights Watch documented in some areas of Gaza. In October 2008, Gen. Gadi Eisenkot, the commander of the IDF’s northern division, stated to the Israeli newspaper Yedioth Aharonoth:

What happened in the Dahiya quarter of Beirut in 2006 [which was severely damaged by Israeli military attacks] will happen in every village from which Israel is fired on. … We will apply disproportionate force on it [the village] and cause great damage and destruction there. From our standpoint, these are not civilian villages, they are military bases. This is not a recommendation. This is a plan. And it has been approved.[28]

International humanitarian law prohibits as indiscriminate any attack “which treats as a single military objective a number of clearly separated and distinct military objectives located in a city, town, village or other area containing a similar concentration of civilians or civilian objects.”[29] The laws of war permit attacks on military objectives such as rocket launchers even if they are located in the midst of populated civilian areas so long as the attacker takes precautions to minimize harm to civilians and the expected civilian harm is proportionate to the military advantage anticipated (see “Legal Obligations”).

The Israeli government should repudiate statements by politicians and military officials that would apply such an unlawful, punitive doctrine to future conflicts.

In addition to the punitive rationale according to which the destruction of civilian property would deter future rocket attacks by Palestinian armed groups, media reports and accounts from Israeli soldiers who participated in the Gaza offensive suggest a second rationale for property destruction: that the IDF would destroy property in order to improve Israel’s military position in Gaza after the conflict. As discussed below and in the section of this report dealing with Israel’s legal obligations, attacks directed against civilian property solely on the grounds that it could potentially be used for military purposes are unlawful.

In some cases Israeli forces may have destroyed property in areas near the border to create a buffer zone that would be devoid of cover from which Palestinian armed groups could in future launch attacks against Israel. This may have been the rationale for destruction of property in one of the cases documented in this report (see “Khuza’a”). However, the laws of war do not permit a party to the conflict to raze all civilian structures in a given area on the grounds that it would provide a buffer zone for a potential future armed conflict (see “Legal Obligations”).

A reserve infantry first sergeant who fought in Operation Cast Lead told Human Rights Watch that at a briefing before he entered Gaza, the battalion commander of his unit said “that the army in our area was going to there with the intention to destroy not only pinpointed targets, but also to do destruction for what they called ‘the day after.’”[30] The sergeant elaborated to Breaking the Silence, an Israeli group of IDF veterans, that “the expression ‘the day after’ was repeated time and again, even as we were still in action.”[31] In addition to being authorized to attack houses that have been “a source of fire” from Palestinian armed groups, the sergeant said,

we were told there are houses to be demolished for the sake of “the day after.” The day after is actually a thought that obviously we're going in [to Gaza] for a limited period of time which could be a week and it might also be a few months. […]. And the rationale was that we want to come out with the area remaining sterile as far as we're concerned. And the best way to do this is by razing. That way we have good firing capacity, good visibility for observation, we can see anything, we control a very large part of the area and very effectively.[32]

According to the sergeant, the “day after” policy applied to any “strategic point … between half a kilometer to over one kilometer [from the border]. I don't remember precisely so I don't want to say, but it's at a reasonable distance [from the border].” The sergeant gave as an example of a “strategic point” a house on a hill from which “anyone on the top of that hill sees both the sea on one side [to the west] and the Israeli border on the other.” The sergeant acknowledged that he felt “a certain confusion” when it came to putting the “day after” policy into operation. “I mean, you see a house, so what do you do? How? I felt the orders here were somewhat amorphous.”[33] The sergeant, whose unit operated during the conflict in a largely open area to the east of Zeytoun, south of Gaza City, said he knew “that this order was carried out in practice, for some of the houses that were demolished had not been incriminated” (i.e. they were not suspected of housing militants, booby-traps, weapons, or otherwise considered military objects).[34] In his area, “several [Caterpillar] D-9 bulldozers were operating around the clock, constantly busy” destroying houses.[35] The first sergeant said that “nobody [in the IDF] was injured in our area,” and that he “didn’t see a single Palestinian during my whole week there,” although other soldiers in his unit reported sporadic attacks by Palestinian militants.[36]

In cases where the “day after” policy was carried out in areas of Gaza near the border with Israel, the sergeant’s account is consistent with a report by the Jerusalem Post on January 11, 2009, that “the IDF was said to be carving out a ‘security zone’ along the border [with Gaza], which it would retain even after an end to the fighting and use to conduct routine patrols aimed at halting rocket attacks against the South.”[37] It is possible that the IDF conducted extensive demolitions in order to create such a buffer area, although the article did not mention such destruction and the IDF did not, in fact, maintain a physical presence inside Gaza after the war. Instead, on May 25 2009, the IDF doubled from 150 to 300 meters the amount of territory inside Gaza’s borders that it denies to Palestinians, by dropping leaflets warning Gaza residents to stay at least 300 meters away from the border or risk being shot. In 2006, Palestinian militants dug a tunnel under the Israeli-Gazan border and captured Israeli Cpl. Gilad Shalit. In June 2009, Israeli Brig.-Gen. (ret.) Shlomo Bron told the Christian Science Monitor that “The buffer zone makes the digging of such tunnels much more complicated and much more difficult […]. Israel established the zone mainly because Palestinian armed groups were attacking Israeli patrols with explosive charges on the Israeli side of the border.”[38]

One of the cases documented in this report – the destruction of 14 homes along the edge of the village of Khuza’a in the south eastern Gaza Strip – involved destruction of property within one kilometer of the Israeli border. Human Rights Watch is not aware of evidence or any IDF claims that Palestinian fighters used the houses later destroyed in Khuza’a as cover for tunnels, rocket or mortar attacks, or other military activity. Apart from Khuza’a, the closest area to the border where Human Rights Watch documented large-scale destruction is Izbt Abd Rabbo and a nearby industrial zone, an area that lies roughly 2.5 kilometers from the border. None of the destroyed buildings Human Rights Watch observed in Khuza’a or Izbt Abd Rabbo were situated in elevated areas of the kind that the IDF sergeant quoted above described as “strategic points.”

The destruction of civilian property to create a “sterile area” that would improve the military position of an attacker in potential future conflicts violates international humanitarian law. While a civilian object that provides a concrete and perceptible military advantage could be justifiably destroyed, a civilian object does not become a target because its destruction would offer the attacker an advantage in a hypothetical future attack, or because of its potential future use as a military objective by the enemy. Since allcivilian objects are potentially military objectives, permitting destruction based on possible future use would allow the destruction of all civilian structures. Thus, while a house protecting the entrance to a tunnel used for military purposes would be subject to destruction, a house that could hypothetically be used by Palestinian armed groups sometime in the indefinite future would not be.[39]

An Israeli soldier who operated a tank in northern Gaza during the conflict told Breaking the Silence, “the amount of destruction there was incredible. You drive around those neighborhoods, and can't identify a thing. Not one stone left standing over another. You see plenty of fields, hothouses, orchards, everything devastated. Totally ruined.”[40] The soldier said that his tank worked in conjunction with D-9 military bulldozers to prepare “secondary protective positions” for IDF forces behind the front lines. If commanders in these areas “didn't like the looks of some house, if it disturbed or threatened them, then it would be taken down,” he said.[41] The laws of war permit house demolitions for imperative military reasons consistent with the laws of war. However, the soldier speculated that only “maybe half” of the demolitions were carried out for “operational needs.” In other cases, it seemed to him that the destruction was gratuitous: “sometimes the company commander would give the D-9s something to demolish just to make them happy.”[42]

Breaking the Silence provided Human Rights Watch with the transcript of an interview the group conducted with the operator of a Caterpillar D-9 militarized bulldozer. The D-9 driver, who requested anonymity, said that he destroyed a large number of homes, orchards and greenhouses in an area of Gaza north of the Sufa border-crossing near the end of Israel’s military operations. Before he entered Gaza, the driver said, he was “shocked” by the briefing that a commander gave his battalion:

[The commander] said, “the fact that we're a democracy works against us, for the army cannot act as aggressively as it would like.” Then he repeated that we're going into this operation aggressively […]. Usually in such talks the army, the commanders mention the lives of civilians and showing consideration to civilians. Here he didn't even mention this. Just the brutality, go in there brutally. […] He said, “In case of any doubt, take down houses. You don't need confirmation for anything, if you want.”[43]

According to the D-9 driver, at a second briefing at the end of the operation, the commander told the battalion that they had demolished 900 houses. The driver found the figure plausible, considering that “around 60” soldiers were involved in operating bulldozers and the fact that “there were people who had been in Gaza for two days constantly demolishing one house after the other.” He added that some demolitions were carried out even after the ceasefire announced on January 18.

We were still going in, this time closer to the fence [along the armistice line] and not demolishing houses, just orchards and stuff like that. Only things that interfere with the ground. We'd flatten the ground near the fence to expand visibility from Israel to […] 200 meters from the fence. I didn't go in at that point, but it was 200 meters.[44]

The driver said he received radio instructions to destroy specific houses, and was not ordered simply to raze an entire area. Nonetheless, he said, no IDF forces followed his bulldozer unit into Gaza and he confirmed that he was the “closing force.” Rather than using the bulldozers to clear explosive charges to prepare the way for a subsequent infantry incursion, he helped raze an area that had already been cleared of militants, concealed tunnels and buildings where intelligence sources said militants might be hiding weapons. It is unlawful to destroy civilian property on the grounds that it might be used by the enemy in potential future conflicts (see “Legal Obligations”). Human Rights Watch observed destroyed civilian property in the area around the Sufa border crossing that was more than 2.8 kilometers from the border (see “Khuza’a, al-Shoka and al-Fokhari,” below).

Several soldiers told Breaking the Silence that they were struck by the “nonstop” nature of home demolitions in areas that the IDF controlled. A member of an Israeli tank crew who had been dug-in in an unspecified residential area in Gaza for a week, stated that Israeli troops destroyed homes in the area with explosive charges “almost daily, all the time,” although the area was emptied of militants and the Israeli forces exercised control. “There were constant blasts […]. Corps of Engineers was engaged there nonstop, with houses containing no one […], where no one was present, and anyway those houses were monitored and I, personally, never saw anyone in there […].”[45]

The IDF has on previous occasions destroyed property in Gaza that even if for a purported military purpose, far exceeded the limits of proportionality under international law – by destroying, for example, 16,000 homes in Rafah from 2000 to 2004, primarily in order to create a buffer zone along the border with Egypt. Human Rights Watch concluded that these house razings were done despite feasible less-destructive alternatives, including the use of ground-penetrating radar that could have detected the presence of tunnels and tactics such as filling up tunnel entrances with cement, indicating that the houses were destroyed “regardless of whether they posed a specific threat.”[46]

The IDF’s willingness to destroy property without sufficient military justification or that caused disproportionate civilian loss mirrored more general reports of military commanders sanctioning attacks on targets without taking all feasible precautions to minimize harm to civilians.A reservist, Amir Marmor, who served as a gunner in a tank crew operating in Jabalya, told The Jewish Chronicle:

We were there for a week and despite the fact that no-one fired on us, the firing and demolitions continued incessantly. I am very doubtful how many of the demolitions can be justified. We were told to expect incoming fire from various directions; our first reaction was to blow up or bulldoze houses in a given direction so as to give us better lines of fire. But then no fire came from that direction, or any other.[47]

Other soldiers described an extremely permissive atmosphere in which commanders failed to discipline soldiers who needlessly destroyed property. “Aviv,” thesquad commander of a company from the Givati Brigade whose forces were in the Zaytoun neighborhood south of Gaza City, reported that soldiers vandalized houses “for no reason other than it’s cool …. You do not get the impression from the officers that there is any logic to it, but they won't say anything.”[48]

In a report published on July 29, 2009, the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) stated that “extensive damage to civilian infrastructure and personal property did occur in the course of the Gaza Operation” but that “much of the damage was demanded by the necessities of war and was the outcome of Hamas’ mode of operating.”[49] The report stated that some damage was due to Hamas’s use of explosive booby-traps, which created secondary explosions that caused damage to nearby property after IDF attacks, and that the IDF was required to destroy some booby-trapped buildings to protect its forces, and had to destroy other property in order to bypass booby-trapped roads and buildings.[50] The MFA report did not mention the operational policy, discussed by soldiers, to destroy property for “the day after.”

As noted, the presence or reasonable suspicion of booby-traps or stored weapons would render otherwise civilian objects like residential buildings legitimate military targets. According to an Israeli soldier who participated in the ground offensive, “many explosive charges were found […]. Tank Corps or Corps of Engineers units blew them up. Usually they did not explode because most of the ones we found were wired and had to be detonated, but whoever was supposed to detonate them had run off. It was live, however, ready….”[51] In some cases the IDF triggered booby-trap explosives that destroyed the building in which they were planted. Breaking the Silence published the account of a soldier who witnessed such an incident near Zeytoun: “a D-9 bulldozer makes the rounds to verify that the house is not booby-trapped. Suddenly the D-9 jumps in the air and the entire ground floor collapses as well as part of the second floor.”[52] In other cases, video footage recorded by Israeli aircraft shows secondary explosions triggered by Israeli attacks, apparently caused by weapons stored by Palestinian armed groups. Some of these secondary explosions appear to have destroyed or damaged the targeted area as well as surrounding buildings.[53]

In all the cases Human Rights Watch investigated in which large numbers of buildings were destroyed or damaged, there was clear evidence that the destruction was carried out by Israeli anti-tank mines or bulldozers.[54] While other instances of property destruction could have been unlawful, we did not investigate cases that did not appear clearly to meet the laws-of-war criteria of extensive, unnecessary destruction in areas under effective control. In instances where Human Rights Watch found that Israeli forces could have had a lawful military reason for destroying property, no further inquiry was conducted, (see “Methodology”).

Similarly, IDF forces could legitimately destroy otherwise civilian objects where there were lawful militarily necessary reasons for doing so, such as because soldiers needed to conduct operations close to buildings that they reasonably suspected were booby-trapped or mined in ways that could have endangered soldiers nearby. In the cases Human Rights Watch investigated, the large scale of the destruction and the fact that it was carried out by the IDF days after taking control of the area are irreconcilable with such an explanation.

The MFA report states:

IDF forces demolished structures that threatened their troops and had to be removed. These included (1) houses which were actually used by Hamas operatives for military purposes in the course of the fighting, (2) other structures used by Hamas operatives for terrorist activity, (3) structures whose total or partial destruction was imperatively required for military necessities, such as the movement of forces from one area to another (given that many of the roads were booby-trapped), (4) agricultural elements used as cover for terrorist tunnels and infrastructure, and (5) infrastructure next to the security fence between Gaza and Israel, used by Hamas for operations against IDF forces or for digging tunnels into Israeli territory.[55]

The laws of war do not prohibit the lawful destruction of structures, infrastructure and agricultural land that fall within the criteria listed by the MFA report. These criteria do not apply to any of the cases Human Rights Watch researched for this report. The prior use by Hamas forces of civilian property is not in itself a sufficient justification under the laws of war for its destruction. Nevertheless, Human Rights Watch did not find evidence of Hamas deployment of fighters, weapons or ammunition in infrastructure, or other militarily necessary reasons for Israel to destroy the property in most of the incidents we investigated. As noted, our conclusions are limited to these individual incidents (which we do not claim to be representative of broader Israeli practice) that appear to have violated the laws of war and that Israel should investigate and repudiate so they are not repeated in future; we did not seek to investigate, and excluded from this report, cases of destruction that might have been due to military necessity.

Photographs

|

Destroyed buildings and a tent camp in Izbt Abd Rabbo, April 2009. Human Rights Watch documented the complete destruction of the homes of at least 287 people on or near the neighborhood’s main road. © 2009 Bill Van Esveld/Human Rights Watch. |

|

An unexploded Israeli anti-tank mine in the rubble of a demolished home in the Izbt Abd Rabbo area of Gaza. There is evidence that the IDF frequently used anti-tank mines to demolish homes in Gaza. © 2009 Bill Van Esveld/ Human Rights Watch. |

|

Hamdan Abu Oreiban, a guard at the Engineering Company for Concrete and Construction Materials, stands next to a destroyed cement pump truck and his own car. Human Rights Watch observed 16 vehicles at the factory that were crushed, apparently by IDF tanks or bulldozers, near Gaza’s Zeytoun neighborhood. © 2009 Bill Van Esveld/Human Rights Watch. |

|

Residents of the village of Khuza’a in southeastern Gaza fled when bulldozers were used against their homes, leaving 119 people homeless. © 2009 Bill Van Esveld/Human Rights Watch |

Bulldozer tracks are visible leading to the remains of the Al Wadiyya family’s destroyed biscuit factory, in an industrial area near Izbt Abd Rabbo. © 2009 Bill Van Esveld/Human Rights Watch.

A resident of Gaza’s Zeytoun neighborhood stands among the ruins of his home, April, 2009. © 2009 Bill Van Esveld/Human Rights Watch.

Izbt Abd Rabo and Nearby Industrial Areas

IDF control of Izbt Abd Rabbo