Stuck in a Revolving Door

Iraqis and Other Asylum Seekers and Migrants at the Greece/Turkey Entrance to the European Union

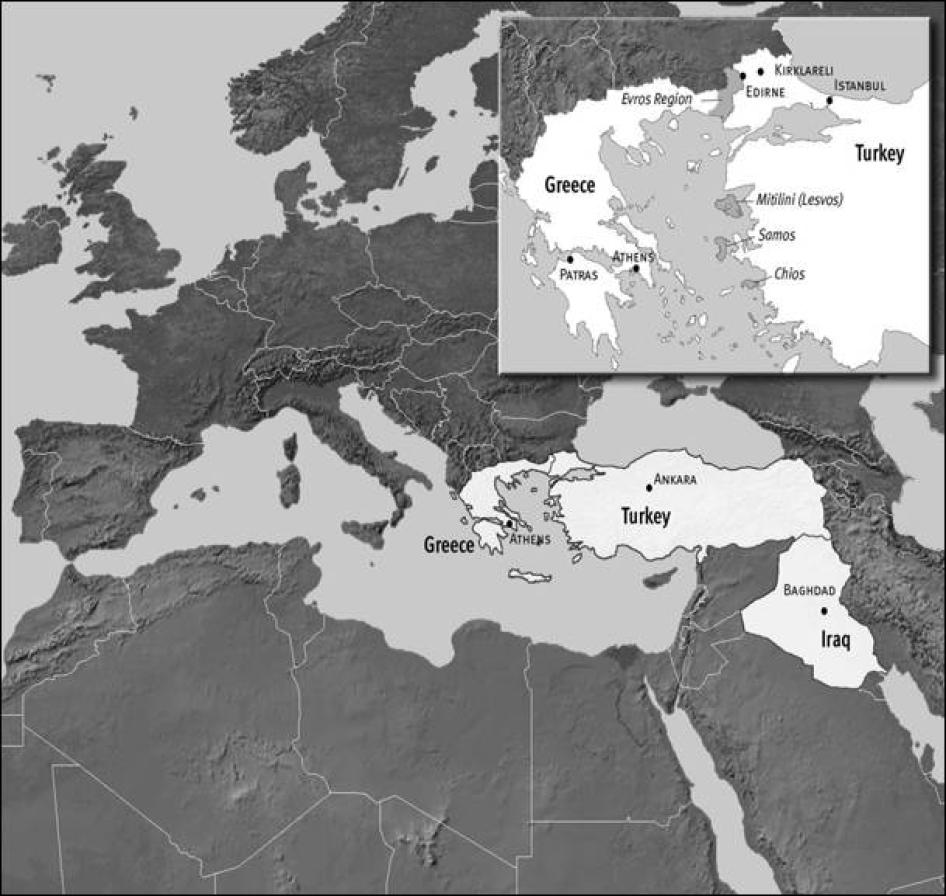

Map of Greece and Turkey Border Region

© Rafael Jimenez

I. Summary

The police arrested me in Thessaloniki and put me in jail for 25 days. The guards did not speak to me. If I tried to speak to them, they just shook their heads. I had no asylum interview when I was arrested, detained, or released. I told them I was an Iraqi. I gave them my real name. They only asked me if I wanted to stay in detention or leave. They told me that if I asked for asylum and a red card that I would need to spend more time in jail beyond 25 days, but if I didn't want asylum and a red card I could leave detention after 25 days. So, I refused the red card and after 25 days they released me. I got a white paper telling me I needed to leave the country in 30 days. I wanted to go to another country to seek asylum, but a friend told me that because they took my fingerprints, they would send me back to Athens. I have now been here a month without papers. Now I am in a hole. I can't go out. I can't stay. Every day I think I made a mistake to leave my country. I want to go back, but how can I? I would be killed if I go back. But they treat you like a dog here. I have nothing. No rights. No friends.

-An Iraqi Kurd from Kirkuk, who made five attempts to cross from Turkey to Greece, was beaten and summarily expelled from Greece to Turkey and beaten and detained in Turkey before going back to Greece.

Iraqis are currently the largest nationality group of asylum seekers lodging new claims in the European Union (EU), and Greece has become their favored entry point. But Greece does not want this role, nor do Iraqis appear to want to stay in Greece, but would prefer to seek asylum in countries to the west and north. However, Iraqi asylum seekers find themselves stuck in Greece. First, they can't move onward because EU asylum law, via the Dublin II regulation, normally requires asylum seekers to lodge their claims for protection in the first EU country in which they set foot and they also can't move back home because of fear of war and persecution. They are almost never provided asylum in Greece.

Most Iraqi refugees attempt to enter the EU via the Greek islands off the coast of Turkey or by crossing the Evros River that marks Greece's land border with Turkey. Despite having 1,170 kilometers of porous land borders and 18,400 kilometers of coastline, including islands in close proximity to Turkey, Greek police and Coast Guard authorities are zealous in their efforts to prevent irregular entry. In 2007, Greek police recorded 112,369 arrests for illegal entry or presence. However, Human Rights Watch believes this is the tip of the iceberg. Many, perhaps most, of the apprehensions in the border region are not recorded at all.

Migrants being rescued by the Hellenic Coast Guard in the Aegean Sea. Photo courtesy of the Hellenic Coast Guard/Intelligence Directorate

Police in the Evros region (northeastern Greece) systematically arrest migrants on Greek territory and detain them for a period of days without registering them. After rounding up a sufficient number of migrants, the police take them to the Evros River at nightfall and forcibly and secretly expel them to the Turkish side.The Turkish General Staff has reported that Greece "unlawfully deposited at our borders" nearly 12,000 third-country nationals between 2002 and 2007. Because this number only indicates those migrants who the Turkish border authorities apprehended and registered and many evade arrest, the actual number that Greece has summarily expelled is very likely to be higher.

In addition to summary expulsions of migrants from inside Greek territory, Greek police and Coast Guard officials also push migrants back from the border or from Greek territorial waters, in some cases puncturing inflatable boats or otherwise disabling them before setting them adrift as they push them toward the Turkish coast. When rounding up and expelling migrants, border-enforcement officials usually make no effort to communicate with them or to do any screening whatsoever to determine their possible needs for protection and in some cases beat and otherwise mistreat them.

This report is about obstacles placed at the Greek entrance to the EU that prevent Iraqis and other asylum seekers and migrants from entering the European Union or that summarily expel them when they do. It includes testimonies from Iraqis and other asylum seekers and migrants on both sides of the Greek-Turkish border about pushbacks and summary expulsions from Greece, inhuman and degrading conditions of detention in Greece, Greek police and coast guard brutality and harassment, and the blocking of access to asylum in Greece as well as the denial of asylum and other forms of protection to those needing it.

This report is also about abusive treatment of migrants by Turkish border authorities in the border region with Greece, including inhuman and degrading conditions of detention in direct violation of Turkey's obligations under the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (ECHR). Once detained, such migrants have no meaningful opportunity to seek asylum or other forms of protection in Turkey and are often held indefinitely until family or friends are able to provide them return tickets. Turkey, which has placed a limitation on the Refugee Convention that only recognizes Europeans as refugees, continues to put Iraqis apprehended at the Greek border on buses and return them to Iraq without giving them any meaningful opportunity to seek protection before being returned.

Given the risk of serious harm arising from generalized violence and widespread targeted persecution in Iraq, Human Rights Watch regards Turkey's return of Iraqis apprehended at the Greek border, in the absence of meaningful opportunities to seek asylum, as a violation of the principle of non-refoulement, the cornerstone of refugee rights law that prohibits the return of a refugee to persecution. International human rights lawin the Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Punishment or Treatment (CAT) also prohibits returning anyone to face torture. On the regional level, Article 3 of the ECHR also prohibits European states from returning anyone who would face a real risk of torture or inhuman or degrading treatment.

Human Rights Watch believes that Greece is violating the principle of non-refoulement not only by returning to Turkey Iraqis who may be subjected to onward return to Iraq, but also by returning any migrants to Turkey because they face a real risk of inhuman or degrading treatment there. The conditions that Human Rights Watch found at the Tunca center in Edirne, in particular, show that migrants returned from Greece are systematically and consistently subjected to inhuman and degrading conditions. By returning migrants to such conditions, Greece is in breach of its obligations under the ECHR.

Greece is also in direct violation of the ECHR when its own conditions of detention are inhuman and degrading. While Human Rights Watch does not regard conditions of detention for migrants in Greece as systematically inhuman and degrading, such conditions are not uncommon. The risk of such treatment is particularly real at the airport where people returned from other EU member and neighboring states under the Dublin system first arrive and in police stations in the border region where migrants from Turkey are often first apprehended and detained. The willingness of the Greek state to accede to its obligations means little if this is not evidenced through the conduct of police and other officials.

Greece also fails to provide refugee protection within its own territory. Of nearly 2,000 Iraqi asylum claims decided in Greece in 2006, none were granted on Refugee Convention grounds or protected because of risk of harm from armed conflict and generalized violence in Iraq. Greece's negative approach toward asylum seekers is not unique to Iraqis-its approval rate in the first instance for all nationalities in 2006 was 0.6 percent and in 2007 was 1.2 percent. Despite the extremely low approval rates, the number of Iraqis lodging asylum claims in Greece increased from 1,415 in 2006 to about 5,500 in 2007.

In April 2008, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) leveled a sharp criticism of Greek asylum and detention policies and recommended that other European states not return asylum seekers to Greece. UNHCR said that asylum seekers in Greece "often lack the most basic entitlements, such as interpreters and legal aid, to ensure that their claims receive adequate scrutiny from the asylum authorities."

The UNHCR announcement was preceded on February 7, 2008 by Norway announcing that it was suspending all transfers of asylum seekers to Greece under the terms of the Dublin II regulation. On March 10, 2008 a Swedish court ruled against the return of a disabled Iraqi asylum seeker to Greece under the terms of the Dublin II regulation. Also, in early 2008, the European Commission initiated an infringement procedure against Greece for preventing access to asylum procedures for persons returned under the Dublin regulation. The Commission will consider whether those returned to Greece are able to gain access to asylum procedures.

As the European Commission proposes amendments to the Dublin II regulation and the Reception Conditions Directive in late 2008, Greece and other Mediterranean EU member states are questioning what they regard as a disproportionate burden that Dublin II creates for member states on the external borders of the EU. At the same time, some member states are questioning the underlying presumption that returns take place among states that have harmonized their standards and procedures for establishing asylum claims and their standards for the reception of asylum seekers, the integration of refugees, and the return of rejected asylum seekers. Greece's treatment of asylum seekers brings into question whether, in fact, such harmonization exists and whether an asylum seeker in Greece has the same opportunity to find protection as in other EU states.

Although some EU states are beginning to have reservations about sending asylum seekers back to Greece, the EU is not meeting its responsibilities to protect refugees fleeing Iraq. It has effectively laid the burden on a few states at the EU's external borders that have limited capacity to deal not only with the influx of refugees from Iraq, but also the larger mixed stream of migrants and asylum seekers seeking entry to the EU.

The EU lacks not only a common asylum policy for people seeking asylum inside the EU, but an external refugee policy as well that would provide support for refugees outside the EU through resettlement and other burden-sharing measures in the region of displacement that could reduce the need of Iraqis to seek asylum outside their region.

Human Rights Watch recommends first that the governments of Greece and Turkey respect the basic human rights of migrants, including rights not to be abused, held in inhuman and degrading conditions of detention, to be granted the right to seek asylum and not to be summarily expelled, particularly when doing so constitutes refoulement, subjecting the returnee to persecution, torture, or other serious harm. Secondly, Human Rights Watch recommends that in consideration of their own non-refoulement obligations, EU states should suspend transfers of asylum seekers back to Greece, and instead opt to examine their claims themselves, as is allowed by the sovereignty clause of the Dublin II regulation. They should choose to resume such transfers only when Greece shows that it has met EU standards for conditions of detention, police conduct, access to asylum and other forms of protection, and the fair exercise of asylum procedures, and when Greece stops its practice of forcibly returning non-nationals who would thereby face persecution, torture, or inhuman and degrading treatment in Turkey or their countries of origin.

II. Recommendations

To the Government of Greece

•Make a public commitment to ensure that migrants apprehended in Greek territory or at the border-whether on land or at sea-are treated in a humane and dignified manner, are given the opportunity to seek asylum if they so choose, and are not subjected to refoulement.

•Prosecute police and coast guard officials who abuse their authority by beating, robbing, and summarily expelling migrants.

•Immediately stop the routine and systematic police practice of gathering migrants in police stations in the Evros region, trucking them to the Evros River, and sending them across the border secretly in small boats. Levy appropriate punishments against those officials involved directly and through command responsibility for illegal acts involving summary expulsions.

•Investigate allegations in this and other reports that Hellenic Coast Guard personnel are involved in the practice of puncturing inflatable boats and setting them adrift, as well as other acts of abuse that put the lives and safety of migrants at risk. Prosecute any guardsmen engaged in such illegal acts, as well as their commanding officers.

•Establish a system for adjudicating asylum claims that is independent of the police (the Secretariat General for Public Order within the Ministry of Interior) and that meets international procedural standards for determining refugee status.

•Provide access to asylum procedures at the border, in the border region, and on the islands; make the asylum booklet widely available in police stations and detention centers; allow independent lawyers and nongovernmental social service providers access to detained migrants; provide resources for interpreters to assist in identifying asylum seekers in these outlying areas and in conducting asylum interviews; and allow asylum seekers to remain in these areas, if they so choose, for the duration of the asylum process, including appeals.

•Reserve the accelerated procedure for cases that do, in fact, appear clearly to be manifestly unfounded, such as those that would fit the criteria for "manifestly unfounded" set out in UNHCR Executive Committee Conclusion 30. Greek asylum practices should be changed so that people who apply for asylum at borders, transit zones or ports, and airports are not automatically placed in the accelerated procedure and likewise that people who do not file an application for asylum as soon as possible are not also deemed to be manifestly unfounded, and, therefore also placed in the accelerated procedure.

•Reform the appeals committee so that it operates transparently through published decisions and is not housed in the Secretariat General for Public Order. Ensure that it maintains sufficient staffing and resources to fairly consider new cases before it, as well as the existing backlog of cases.

•Provide an efficient and dignified way for asylum seekers to lodge asylum claims in Athens. Allow any asylum seekers who appear at a port of entry, transit zone, or police station anywhere in the country at any time to submit an asylum application and in doing so to receive a receipt with an appointment date for a first-instance asylum hearing and papers that entitle them to stay in Greece until they are issued a red card (the standard document for asylum seekers).

•Provide asylum seekers access to legal representation, funded through public funds.

•As a matter or priority, train asylum interviewers and decision-makers on subsidiary protection for people fleeing indiscriminate violence arising from armed conflict or from torture or inhuman and degrading treatment (introduced into Greek law in July 2008).

•Take note of UNHCR's recommendation that all states consider asylum seekers from central and southern Iraq as refugees based on the 1951 Refugee Convention, and that those who are not so recognized should be afforded subsidiary protection.

•Provide an efficient and dignified way for asylum seekers holding a red card to renew their cards in six-month intervals.

•Avoid the detention of asylum seekers and, consistent with international standards, resort to detention only when necessary and on grounds prescribed by law; when detaining asylum seekers, comply with Presidential decree 90/2008 Article 13.2 that "the time period of confinement [for an asylum seeker] shall in no case exceed sixty (60) days." Provide a means for detainees to challenge their detention and to seek provisional release.

•Close the Mitilini, Peplos, and Venna detention facilities and open new facilities, as needed, modeled on the new detention facility on Samos. Ensure the adequate space, privacy, cleanliness, recreation, access to health care and legal and family visitation necessary for humane conditions of detention.

•Stop the administrative detention of non-criminal foreigners in police stations and other common law enforcement detention facilities.

•Build additional open accommodation centers to house destitute asylum seekers in need of shelter and humanitarian support.

•Provide suitable accommodation-not detention-for particularly vulnerable asylum seekers, including survivors of torture and victims of trafficking.

•Immediately stop the practice of routinely detaining unaccompanied children. Detention of unaccompanied children should only be administered as a measure of last resort, for the shortest time possible and only if it is in the child's best interests. Immediately increase the number of care places for unaccompanied children and ensure sufficient places are available to provide accommodation for all unaccompanied children in Greece. Provide specialized care arrangements for unaccompanied girl children.

•Support the social integration of refugees and other protection beneficiaries by promoting Greek language instruction, access to health care, education and professional training, and the job and housing markets.

•Suspend the readmission agreement with Turkey until Turkey complies with minimal standards for the detention of migrants and provides a meaningful opportunity for returnees to seek protection and not to be summarily returned to Iraq or Iran.

•To avoid repeat detentions, harassment, and summary removals, ensure that non-nationals can only be deported if there exists a lawful deportation order which has been issued following full due process and the exhaustion of legal remedies, after voluntary repatriation has been offered, and if no other protection need or other legal or humanitarian basis for staying in Greece has been found. Deportations carried out on this basis must be done so in an orderly, dignified, and humane manner.

•Enlist the help of the International Organization for Migration to assist in the voluntary return of migrants who do not have a protection need and want to return to their home countries.

•Provide the UN High Commissioner for Refugees full access to all migration detention facilities, Coast Guard vessels and facilities, and to entry and border points and the border region.

•Act with greater transparency with respect to nongovernmental human rights monitors by acceding to reasonable requests from reputable NGOs for access to monitor conditions of detention, including by permitting them to conduct private interviews with detainees.

To the Government of Turkey

•Immediately stop deporting busloads of Iraqis apprehended at the Greek border to Iraq.

•Immediately close the Tunca detention facility at Edirne. Until a proper facility can be built, temporarily transfer all detainees in Tunca who cannot be released or deported to the Gaziosmanpaşa Refugee Camp at Kırklareli.

•Investigate allegations of abuse by gendarmes at the border and by guards at the Tunca facility and prosecute those responsible for abusing migrants and detainees.

•Build a proper detention facility at Edirne to meet the needs for administrative-not punitive-detention of undocumented or improperly documented migrants.

•Provide financial support to the relevant police authorities in Edirne commensurate with the numbers of migrants apprehended and detained there so that the detention facility is adequately staffed-including with health-care professionals on site-and is able to provide for the nutritional, sanitary, recreational, and health needs of detainees.

•Avoid the detention of asylum seekers and, consistent with international standards, resort to detention only when necessary and on grounds prescribed by law. Provide a means for detainees to challenge their detention and to seek provisional release.

•Set time limits (we suggest two months) on the administrative detention of migrants who are being held pending their removal from Turkey.

•Cease the practice of holding migrants in indefinite detention until such time as their families are able to pay for their return tickets.

•To avoid indefinite detention, harassment, and summary removals, ensure that non-nationals can only be deported if there exists a lawful deportation order which has been issued following full due process and the exhaustion of legal remedies, after voluntary repatriation has been offered, and if no other protection need or other legal or humanitarian basis for staying in Turkey has been found. Deportations carried out on this basis must be done so in an orderly, dignified, and humane manner.

•Enlist the help of the International Organization for Migration to assist in the voluntary return of migrants who do not have a protection need and want to return to their home countries.

•Provide the UN High Commissioner for Refugees full access to all migration detention facilities and to the Meriç River border region.

•Lift Turkey's geographic limitation to the 1951 Refugee Convention so that Iraqi, Iranian, and other non-European refugees will be fully recognized and protected equally with European refugees.

•Ratify the Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture, and implement the Protocol through the creation of an independent national body to carry out regular and ad hoc unannounced visits to all places of detention.

•Prior to ratification, urgently take steps to permit independent visiting of places of detention by representatives of NGOs, lawyers, medical professionals, and members of local bar associations.

To the European Union and Its Member States

•Suspend the transfer of asylum seekers to Greece under the Dublin II regulation because the Greek authorities prevent access to asylum procedures for persons returned to Greece, because its detention conditions, police conduct, and asylum procedures are not, in fact, in conformity with EU standards, even if its laws are formally compliant with EU directives, and because it systematically commits refoulement by summarily and forcibly returning third-country nationals to Turkey where they face a real risk of being subjected to inhuman and degrading conditions of detention and where two nationalities, Iraqis and Iranians, are subjected to onward deportation to their respective countries of origin with inadequate opportunity to seek protection.

•Ensure that all EU states fully implement the minimal standards of the EC directives on reception conditions for asylum seekers, asylum procedures, and the qualification for refugee status and other forms of protection.

•Reform the Dublin system by having the Dublin regulation take into account equitable burden-sharing among member countries that genuinely have common asylum standards and procedures by, for example, consideration of joint EU processing within the EU of specific caseloads. The operating principles of the Dublin system should also be reformed by according greater weight to the variety of factors that might connect an asylum applicant to one state over another. Such connections go beyond the qualifying family relationships in the Dublin II regulation to include wider family relations, community ties, prior residence, language, job skills that might be in demand in one country over another, and the personal preference of the applicant, a legitimate factor to consider. A reformed Dublin system should accord less weight than under the current regulation to the country of first arrival in assessing the state responsible for examining asylum claims.

•Establish a refugee resettlement program in cooperation with the UN High Commissioner for Refugees that sets quotas for all EU member states based on their capacity to accommodate refugees as a means both of expressing international solidarity and of providing a safe and legal mechanisms for refugees in need of resettlement to avail themselves of protection, family reunification, and durable solutions in Europe. Such a refugee program should be regarded as complementing a common European asylum system and not as a substitute for providing protection to asylum seekers within the EU.

To the UN High Commissioner for Refugees

•Continue to advise EU member states not to transfer asylum seekers to Greece under the Dublin II regulation until that country demonstrates its ability to give asylum seekers fair hearings on the merits of their claims, as well as reception, detention, and removal procedures that are on a par with EU standards and the practices of other EU member states.

•Assign at least one full-time protection officer for the Greek-Turkish border/Aegean Sea region to better identify and protect people in need of international protection in the mixed migration stream in the Turkish-Greek border area.

•Establish a sub-office at Edirne in Turkey.

To the Council of Europe's Commissioner for Human Rights and Committee for the Prevention of Torture

•Increase the number and frequency of visits to Greek immigration detention centers, particularly during anticipated periods of overcrowding, and conduct visits to immigration detention centers in Turkey.

To the International Organization for Migration

- Seek funding to be able to offer more assistance for undocumented third country nationals who wish to return to their home countries from Greece and Turkey to help them to voluntarily repatriate and reintegrate into their home economies. Repatriation assistance should be strictly reserved for people who have no need for international protection; it should be completely voluntary and only to places that allow for safe, dignified, and sustainable return.

III. Methodology and Scope

Human Rights Watch conducted research for this report in Greece from May 22 to June 5, 2008 and in Turkey from June 5 to June 14, 2008. We conducted 173 interviews with migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers, of which 126 took place in Greece, 46 in Turkey, and one by telephone with an Iraqi asylum seeker in the Netherlands who had recently arrived from Greece. Human Rights Watch told all interviewees that they would receive no personal service or benefit for their testimonies and that the interviews were completely voluntary and confidential.

Human Rights Watch interviewed 79 Iraqis, 32 Afghans, 13 Somalis, 11 Iranians, and 38 members of 16 other nationalities. The 173 people interviewed were overwhelmingly male, which reflects both that more single men than women engage in irregular migration and that the women who do migrate are harder to locate and interview. We were able to interview only 16 females. Of that number, five were Iraqis, all of whom were Christians living for a number of years in Athens; the remainder were all women or girls interviewed in places of detention: in Greece, five in the Petrou Ralli jail in Athens, one in the Kyprinou detention facility in Fylakio, and one in the detention facility on the island of Samos; in Turkey, three in the detention facility at Kırklareli and one in Edirne.

Although the age demographics of the Iraqis interviewed were evenly spread out (three teenagers; 20 in their twenties; 20 in their thirties; 22 in their forties; 4 in their fifties; and 10 in their sixties), those over the age of 40 were almost all Christians living long-term in Athens, whereas the Muslims were almost all under age 40. The Iraqi Muslims were less likely than their Christian co-nationals to have spent as much time in Greece or to be asylum applicants or to have some form of documentation. By contrast, the non-Iraqis interviewed were on the whole much younger than the Iraqis: two were pre-teenage children; 35 were teenagers; 46 were in their twenties; 7 in their thirties; and only 3 in their forties and 1 in his fifties.

Iraqi Christians were disproportionately represented in the interview sample because they have been living in Greece (and Turkey) longer, are more integrated, better organized communally, and therefore easier to locate and interview than the largely undocumented Iraqi single Muslim men. Of the 79 Iraqis interviewed, 38 were Christians, 13 were Kurds and one each identified himself as Sabean or Turkoman. Of the 26 Arab Muslims, the relatively small number who identified as Sunni or Shi`a was evenly split, and a few spoke about having parents of mixed sectarian backgrounds. The majority of Iraqis interviewed, 41, came from Baghdad, which was the case for nearly all of the Muslim newer arrivals. Mosul was home for nine of the interviewees, and eight originated from Kirkuk. Smaller numbers came from Dahok, Zakho, Erbil, Sulaymaniya, Diyala, Basra, Najaf, Karbala, and small villages.

Of the 79 Iraqis interviewed, 70 were in Greece, 8 in Turkey, and 1 in the Netherlands. Of those interviewed in Greece, 62 interviewees were in Athens, 5 in Samos, and 3 were detainees at Petrou Ralli. Nearly all of the interviews of Iraqi Christians in Athens took place at a community center near a church that includes a health clinic and provides other social services. Nearly all of the interviews of Iraqi Muslim Arabs, Kurds, and other Iraqi minorities took place in complete privacy in slum tenement buildings and cafes in Athens or the makeshift camp at Pendeli. Of the Iraqis interviewed in Turkey, six (all Christians) took place in private homes in Istanbul, and two were with detainees in Edirne. With the exception of detainees and some of the Christians at the community center, interviews generally lasted at least 40 minutes and often more than an hour.

Of the 94 non-Iraqis interviewed, 56 were interviewed in Greece and 38 in Turkey. Of those interviewed in Greece, 15 were interviewed in Athens, 10 on the islands, seven (all Afghans) in Patras, and 14 in detention. Interviews of non-detainees in Athens and on the islands took place in slum tenement buildings, parks, or the office of the Ecumenical Refugee Center, and were conducted with complete privacy and often lasting an hour or more.

Interviews of detainees in Greece did not take place under optimal conditions with complete privacy from other detainees, but guards who were usually within eyesight of the interview were not able to hear what was being said. Despite repeated requests, Human Rights Watch was not granted permission to visit Mersinidi in Chios, Pagani-Mitilini in Lesvos, and police facilities and detention centers in Peplos, Vrissika, Feres, Soufli, Tichero, Sapes, and Venna in the Evros region. The information gleaned about these facilities, therefore, comes exclusively from former detainees (and our brief, unauthorized visit to Venna).

The Greek Ministry of Interior initially gave Human Rights Watch permission to visit only two facilities, Fylakio-Kyprinou in the Evros region and the new facility on Samos Island, and specified that the visits to the two facilities would be "for a few minutes" and "without discussion with detainees."[1]

Following the visits to Fylakio-Kyprinou and Samos, Human Rights Watch wrote to Brigadier General Constantinos Kordatos, commander of Hellenic Police Headquarters Aliens' Division, saying, "It is not possible to make any meaningful assessment of detention conditions without the opportunity to talk with detainees or to spend more than a few minutes walking through a facility," and again requested permission to visit more facilities and to be able to interview detainees privately.[2] Following the second letter, the authorities gave Human Rights Watch permission to visit the detention facility for boys at Amigdeleza[3] and the detention facility at Petrou Ralli and allowed more time for us to speak with detainees.

All of the non-Iraqis interviewed in Turkey were detained-24 in Edirne and 14 in Kırklareli. All 11 of the Iranians interviewed were in Turkey. The interviews at Edirne and Kırklareli were conducted in complete privacy, outdoors in courtyard areas without the presence of guards, police, or other authorities and each interview took as long as we wanted, in some cases for an hour or more.

Human Rights Watch was particularly careful in questioning people who claimed to be Iraqi to ensure that they were truthful about their nationality; we are satisfied that all those listed as Iraqi in these statistics and in this report are, in fact, Iraqi nationals. The primary researcher for this report has conducted extensive interviews with Iraqi refugees and displaced people inside Iraq and in Turkey, Jordan, Iran, and Kuwait. The Arabic interpreter lived and studied in Baghdad. We asked specific questions and assessed accent in order to test those claiming to be Iraqi.

We are less confident that detainees identifying themselves as Burmese, Somalis, and Palestinians were who they said they were; in fact, one or two detained "Palestinians" may have been Iraqis. For the purposes of this report, the actual nationalities of these detained non-Iraqis did not reflect on their credibility about conditions of detention, treatment at the border, and access to asylum.

We also interviewed police chiefs and detention center guards in both Greece and Turkey, as well as Coast Guard personnel in Greece. In both Greece and Turkey, we interviewed UNHCR, lawyers, service providers, and other experts.

This report pays relatively little attention to the situation of unaccompanied children in Greece because Human Rights Watch is issuing a separate, complementary report on the treatment of unaccompanied children in Greece. Left to Survive: Protection Breakdown for Unaccompanied Children in Greece was researched at the same time as this report and will be published soon after this report's release.

We note that Greece adopted two new refugee laws in July 2008, Presidential Decrees 90/2008 and 96/2008, after we had completed our field research but before publication of the report. Although the two laws were officially applicable retroactively, in real time officials were unaware of the applicability of laws that had not yet been passed. In some cases, this created a discrepancy between what officials, experts, and asylum seekers told us about how the asylum system functions (for example, with respect to length of time of detention and deadlines for filing appeals) and how it should now be operating. We have tried to note such discrepancies in footnotes.

Finally, we promised to protect the anonymity of the migrants, asylum seekers, and refugees we interviewed. In most cases they gave us their names and other identifying details that will remain confidential. The notation used in this report uses a letter and a number for each interview; the letter indicates the person who conducted the interview and the number refers to the person being interviewed. All interviews are on file with Human Rights Watch.

IV. Background

The Geography of Migration: the Greek Gateway to the EU

Routes of irregular migration are constantly shifting; as immigration enforcement measures stiffen in one area migrants and smugglers probe and test for other soft points of entry. But two factors rarely change-the political boundaries that delineate international borders and the topography that makes one frontier porous and another impenetrable. Not only because Greece stretches into the eastern Mediterranean, but also because it has 1,17o kilometers of land borders and 18,400 kilometers of coastline, including islands in close proximity to Turkey, Greece is likely to remain an attractive entry point into the EU. With an eastern frontier bounded by the Caucasus Mountains and the Black Sea in the North and the Mediterranean in the south, Turkey effectively funnels migrants traveling overland from the Middle East and South Asia into Greece, while Africans are increasingly coming to Greece via Egypt.

Increase in Apprehensions

Stiffened interdiction measures in the western and central Mediterranean since 2005 appear to have contributed to shifting irregular migration routes toward Greece. While the number of irregular boat arrivals to Spain dropped by 53.9 percent from 2006 to 2007,[4] irregular boat arrivals to Greece increased by 267 percent during this same time period.[5] At this same time when irregular boat arrivals to Greece were almost tripling, they were also decreasing in Italy and Malta.[6] It is difficult to weigh all the variables for shifts in irregular migration patterns, but the rapporteur for the Council of Europe Parliamentary Assembly's Committee on Migration, Refugees and Population suggests that the shift away from Spain and Italy and toward Greece in 2007 was at least partly because "increased sea controls, including by FRONTEX,[7] …almost certainly had an impact, in particular during the periods the operations have been in operation."[8]

Greek police recorded 112,369 arrests for illegal entry or presence in 2007, more than double the number apprehended in 2003.[9] However, Human Rights Watch believes that the true number of apprehensions is much larger. Many, perhaps most, of the apprehensions in the border region are not recorded at all. After apprehending migrants in the border region, police detain them for a period of days without registering them. The police take these uncounted and unregistered migrants to the Evros River at nightfall and forcibly and secretly return them to the Turkish side. In addition to these numbers are the migrants that the Coast Guard apprehends and pushes back from Greek territorial waters.

Increase in Asylum Applications

Although relatively few of the migrants apprehended in Greece seek asylum, the number of asylum seekers has been increasing dramatically. As recently as 2004, Greece received a modest 4,500 asylum applications, but by 2007 the number of asylum claims had increased fivefold to more than 25,000, of whom 5,500 were Iraqi claimants.[10] In 2007, Greece was the fourth largest recipient of new asylum claims in the EU, exceeded only by Sweden, France, and the United Kingdom (UK).[11] Although EU member states saw an 11 percent increase in the number of asylum seekers from 2006 to 2007, Greece saw a 105 percent increase during this period.[12]

From Human Rights Watch interviews with Iraqis and other migrants in Greece, this increase ought to be attributed less to a recent preference among asylum seekers to lodge protection claims in Greece but rather to the blocking of other options; once fingerprinted in Greece, many asylum seekers lose hope of being able to seek asylum in their preferred destinations in Sweden, the UK, Germany, and other countries.

The EU has frustrated the preferred destinations of asylum seekers through a regulation known as Dublin II, which since February 2003 (and building on the framework of the earlier Dublin Convention, which has been in force since 1997) establishes that the Member State responsible for examining asylum claims will generally be the one in which an asylum seeker first sets foot.[13] Although both Greece and the Iraqi asylum seekers appear to agree on their preference that Iraqis not stay in Greece but rather seek asylum in countries to the west and north, in fact, Iraqi asylum seekers find themselves stuck in Greece-they can't move onward because of Dublin II, they can't move back home because of a fear of war and persecution, but they are almost never granted asylum in Greece. In 2007, the approval rate for asylum seekers was 0.04 percent in first-instance interviews.[14]

V. The Dublin System and the Failure of International Burden Sharing

At the Tampere European Council in 1999, the EU committed itself to establishing a Common European Asylum System (CEAS) that would harmonize refugee standards and asylum procedures throughout the EU. Nearly 10 years later, despite multiple EC asylum directives, the reality is that wide disparities exist throughout the EU in the treatment of asylum seekers. Far from a harmonized system, the EU is faced with a situation where Sweden would have a 91 percent approval rate for Iraqi refugees in the same year (2006) that Greece had an Iraqi asylum approval rate of zero. Clearly the EU asylum system is not harmonized. Nor is the refugee burden being shared equitably when those same two countries-Sweden and Greece-host three-fifths of all Iraqi asylum seekers in the EU.

Ostensibly to prevent "asylum shopping" and "refugees in orbit," the Dublin II regulation[15] sets out which member state is responsible for examining an asylum claim. It normally will be the country of first arrival and applies to all EU member states, as well as Norway, Iceland, and Switzerland.[16]

Based on the assumption that all participating states have the same standards and procedures for determining refugee status, the Dublin system highlights how much lower Greece's asylum standards and procedures are in comparison to other European states. Among its flaws, the Dublin system ignores the legitimate interest asylum seekers have in choosing where to apply for asylum and unfairly allocates the burden of processing asylum claims to the states on the EU's external frontiers.

Because of the dual failure of the Dublin system, two European countries, Sweden (because of its relative generosity) and Greece (because of its geographical location), have shouldered a disproportionate share of the Iraqi refugee burden-62 percent of all asylum applications lodged in the EU in 2007, to be exact.[17] Left nearly alone to bear the burden, both Sweden and Greece have reacted in ways that are as unfortunate as they are predictable.

Sweden's reaction was to become much less willing to recognize Iraqis as refugees and less generous in offering asylum. It went from granting 91 percent of Iraqi refugee claims in 2006 to 25 percent in the first trimester of 2008.[18] In the first half of 2008, only about 4,000 Iraqis lodged asylum claims in Sweden,[19] less than half the number who applied during the first six months of the previous year.

Greece has taken the approach of using noxious detention conditions, procedural obstacles to lodging claims, and illegal summary removals and abusive police and Coast Guard conduct to deter asylum seekers from entering Greece or, if they do succeed in entering, to dissuade them from staying or from seeking asylum there.

A more equitable and better managed approach by the EU as a whole might have put less of a burden on Sweden and Greece and resulted in better protection for Iraqi refugees. But whatever the EU's failures in equitable burden sharing within the EU or the wider world, this does not obviate Greece's own responsibility to treat all human beings-migrants included-humanely and its obligation not to return refugees and asylum seekers to persecution or anyone to the real risk of inhuman and degrading treatment or worse.

Transfers to Greece under Dublin II

Iraqis and other non-EU nationals who enter the EU irregularly through Greece and then move further into the Union face the possibility of forced return to Greece under the Dublin system.[20]

The state of destination can transfer an asylum seeker to the state of first entry, which the Dublin system regards as "responsible" for examining the claim for asylum. The EURODAC fingerprint database makes such transfers possible.[21] Member states fingerprint asylum seekers and then cross reference the fingerprint with the EURODAC system to determine whether the person previously entered another state.

Transfer is not mandatory, however. Article 3(2) of Dublin II, called the "sovereignty clause," permits a state to maintain responsibility for an asylum claim, even if under the regulation that individual could be transferred elsewhere. In April 2008, UNHCR called on European states to utilize this sovereignty clause and not return asylum seekers to Greece.[22] UNHCR was heavily critical of the Greek asylum system. It concluded that there was no meaningful assessment of an asylum seeker's claim in Greece, saying that asylum seekers in that country "often lack the most basic entitlements, such as interpreters and legal aid, to ensure that their claims receive adequate scrutiny from the asylum authorities."[23]

UNHCR raised concerns about the so-called "interrupted" procedure. Under Greek asylum law at that time,[24] where an asylum seeker had commenced a claim but did not continue with it-for example, by leaving Greece for another European country-Greece could regard the claim as "interrupted" and close it without further review. Dublin returnees were unable, therefore, to renew their asylum claims after being transferred back to Greece. Thus Greece completely subverted the supposed purpose of the Dublin system: The Dublin system returned asylum seekers to Greece on the assumption that Greece was responsible for examining their claims, but Greece refused to examine their claims because they had left Greece to seek asylum in another European country.

On February 7, 2008 Norway preceded the UNHCR announcement by suspending all Dublin system transfers of asylum seekers to Greece.[25] In March, a Swedish court stopped the transfer of a disabled Iraqi man to Greece,[26] and in May the Swedish Migration Board suspended returns of unaccompanied children to Greece, citing the Greek practice of detaining them for three weeks upon return.[27] Also, in March 2008, the European Commission (EC) initiated an infringement procedure against Greece for breaching Article 3 (1) of the Dublin II regulation because it was continuing to prevent access to asylum procedures for persons transferred by other Dublin members to Greece.[28] In late April, Finland announced that it would suspend transferring migrants to Greece unless it received written assurances from Greece that they would be fairly processed.[29]

Stung by the public rebuke and faced with an infringement proceeding before the European Court of Justice, Greece enacted a new refugee law on July 11, 2008 that allows asylum seekers transferred under the Dublin system to reopen their cases.[30]

The number of actual transfers of third-country nationals to Greece under the Dublin II regulation is modest. In 2007, member states transferred only 747 persons to Greece under Dublin II.[31] Member states made 3,306 requests for transfers during the year, of which Greece accepted 2,097 and rejected 380, but actual returns lagged far behind. A similar pattern of few actual transfers relative to the number of requests and acceptances has been a consistent pattern since Dublin II went into effect, although the number of transfers to Greece has steadily grown from 350 in 2005 to 501 in 2006 and 747 in 2007.[32] This growth pattern appears to be continuing in 2008 with 272 transfers in the first trimester of the year.[33]

The EU's Failure to Relieve the Iraqi Refugee Burden in the Middle East

The burden of hosting Iraqi refugees has not only not been equitably or fairly shared within the EU; the EU has also failed to share the refugee burden with the wider international community. UNHCR estimated in August 2008 that about 1.8 million Iraqi refugees were living in the Middle East.[34] For the whole of the European Union, the number of Iraqi asylum seekers in 2007 was 38,286 and 19,375 in 2006.[35] Although Iraqis were the largest nationality group seeking asylum in the EU in both those years, their numbers pale in comparison to the number of Iraqi refugees hosted by Syria (more than one million) and Jordan (about a half million).

Europe has done little to relieve the pressure on Iraq's neighbors or to share the burden by creating a legal mechanism to identify and protect Iraqi refugees.[36] Although UNHCR had recommended 40,000 Iraqi refugees for third-country resettlement through August 2008, only 15,000 had departed the region, 10,000 of whom were resettled in the United States.[37] As of August 2008, only seven EU countries had agreed to resettle any Iraqi refugees for an EU total of 1,752 since the beginning of the war in April 2003, and the EU's largest[38] and most successful[39] country, Germany, had not agreed to take a single one.[40] In contrast, Syria was admitting an average of 2,000 Iraqi refugees a day through much of 2006 and 2007.

Given the paucity of resettlement to the European Union, the only option for most Iraqis who want to seek asylum in Europe is to embark on a dangerous and illegal journey that exposes them both to the predations of traffickers and the abuses of law-enforcement officials. A refugee seeking protection in the EU has little option but to cast off on a rubber dinghy or unseaworthy boat into the uncertainty of the Aegean Sea or to wade and swim across the Evros River.

Faced with a refugee crisis of the magnitude of the Iraqi emergency (with an estimated 2.8 million internally displaced persons and 1.8 million refugees),[41] the European Council could have recognized the existence of a mass influx through its "temporary protection" directive of 2001 or developed a long-overdue refugee resettlement mechanism to provide a legal mechanism to identify and protect refugees who need to be removed from the region.[42] But it did not. Instead, the EU exacerbated the lack of international solidarity and burden sharing by using the Dublin system to shift its own internal burden to Greece as the entry-point to the EU for most Iraqis and not even to share the responsibility of hosting its own relatively small number of Iraqi asylum seekers equitably among its members.

VI. Iraqi Refugees and Migrants

In 2007, Iraqis were the largest nationality group of asylum seekers lodging new claims in the European Union (EU),[43] and, indeed, in the world.[44] The number of Iraqi asylum seekers applying in the EU doubled from 2006 to 2007, increasing from 19,375 to 38,286.[45] But only two countries, Sweden (18,600) and Greece (5,500), hosted fully 62 percent of all Iraqi asylum applicants in 2007.[46] The inequitable burden on these two countries has had negative consequences.[47]

Despite horrendous sectarian violence and widespread generalized violence in Iraq in 2006 and 2007, Greece neither granted refugee status nor subsidiary protection[48] based on generalized violence to a single one of the 5,474 Iraqis who lodged asylum claims in 2007.[49] Greece rejected 3,948 Iraqis after first interviews, with the remainder pending at year's end.[50]

At the beginning of the Iraq war in 2003, Greece suspended hearing any appeals of Iraqi asylum denials. For pending cases, this ensured that Iraqis who were able to renew their red cards[51] at least would not be deported to Iraq, but it also left them in limbo with no possibility to reunite with family members or to integrate into Greek society. Under criticism for its extremely low asylum approval rates, the Greek authorities decided in July 2007 to resume hearing appeals of Iraqi cases and gave priority to certain Iraqi cases before the Appeals Committee. In fact, the cases the Appeals Committee heard were overwhelmingly old cases, mostly of Christians who had been living in Greece long before the war started.[52]

The prioritization of old Iraqi cases in the appeals procedure has had a somewhat distorting effect on recent asylum statistics. Out of the 6,000 cases the Appeals Committee heard in 2007, it recommended granting asylum to 140, of whom 107 were Iraqis-and all of those were Christians who had applied for asylum prior to the beginning of the war in 2003.[53]

Iraqis living in Greece generally would prefer not to seek asylum in Greece and those who opt for Greece usually do so only because there are no other options.

Determining the nationality of Iraqis at all can be quite a challenge.[54] Many Iraqis are afraid to disclose their true nationality out of fear that Iraqis are more likely to be deported than other nationalities. Many claim that they are Palestinians, a group that cannot be deported. One, who at first told Human Rights Watch that his nationality was Palestinian, added with a wink, "Sometimes you have to lie to survive."[55] Ironically, however, in the past six months, as the freeze on processing Iraqi appeals cases has been lifted and Iraqi claims are being granted, an increasing number of Arabic speakers who are not Iraqis are now claiming to be Iraqis.[56]

Despite the almost universal preference of Iraqis not to seek asylum in Greece, Human Rights Watch interviews with scores of Iraqis in Greece revealed many with strong claims for refugee status, including kidnapping and torture victims, people with close relatives and associates who had been targeted and killed, and members of groups subjected to persecution.

Iraqis told Human Rights Watch harrowing and detailed testimony about human rights abuses they experienced in Iraq. There is no typical testimony, but some are indicative of conditions many face. A 28-year-old Shi`a man who is undocumented in Greece and has not sought asylum there said that he had been kidnapped by the Mahdi Army and subsequently fled to escape forced recruitment from his former kidnappers:

I am Shi`a from the Hayy al-Bunuuk neighborhood of Baghdad. I left because of the Mahdi Army. They wanted me to spy for them, to tell them who was Sunni, who was who. I refused. They then threatened to kill me. They kidnapped me on October 16, 2006, and my family paid $2,000 to get me released. My family couldn't afford more, so they accepted this amount. I was held for 12 or 13 days. The Mahdi Army came back to me after they kidnapped and released me to tell me they wanted me to be an informant for them. It was the same guys who kidnapped me who asked me to join them. I left because the time had come for me to escape. That was January 2007.[57]

Others, such as this 33-year-old man of mixed Sunni-Shi`a parentage, told Human Rights Watch how they escaped from Sunni militias:

I have a Sunni father and a Shi`a mother. Because we are half Sunni and half Sh`a, everyone sees us as spies. We pray in the Shi`a way. When Sunnis see me pray, they look at me like I'm an animal, like I am the enemy. Two of my brothers worked as translators for the Americans. A terrorist killed one of my brothers, Ali. [He shows a photo of the dead brother and his death certificate.] They told Ali to come with them, got him alone, and then shot him four times in the chest. The same people who killed my brother are the ones who hate me for praying the Shi`a way.

Terrorists caught me on my way to my job on April 11, 2004. They kidnapped and tortured me for four days. They beat my head and back. I still can't sit without pain. I have scars on my eyebrows. After four days they contacted my family. They took me by car on the highway, hit my head with a rifle butt, and left me. It was near Fallujah. My face was covered in blood.[58]

Many of the Iraqi migrants and asylum seekers in Greece are also Christians who have fled targeted persecution. A 33-year-old Christian from Baghdad-who has not sought asylum in Greece-gave this account of his reasons for fleeing:

A Sunni militia killed my father and my sister's husband in 2005. My younger sister's husband was kidnapped, held for a $25,000 ransom and released. I had a car and was going between Baghdad and Syria when Al-Qaeda in Iraq stopped me in al-Anbar. They told me to become a Muslim or they would kill me. I declared the Shahada.[59] They followed me to my neighborhood, Dora. They destroyed my house. I took my wife and children, and we moved to northern Iraq, but you can only stay in the north if you are from the north. I am not a Kurd. I couldn't go out. I couldn't work there. I could not support my family.[60]

VII. Access to Greek Territory: Apprehensions, Orders to Leave, Deportations, Summary Expulsions and Pushbacks

Greek border controls both in the Evros region (northeastern Greece) and in and around the Greek islands off the coast of Turkey not only make virtually no distinction between people seeking asylum and others, but also generally show a disregard for the basic human rights of third country nationals. Greek coast guard and police officials violate a host of basic rights, including the right to seek asylum, enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and the right not to be subjected to refoulement-the forcible return of people to places where they would be subjected to torture, inhuman and degrading treatment, persecution, or other serious harm.

Apprehensions

Aside from the physical barriers of river or sea, the greatest obstacle for irregular migrants seeking to cross into Greece is being caught by border or coast guard security personnel.[61] When Greek coast guard and police officials first apprehend migrants at the borders, they are often brutal and intimidating. The most frequently cited rationale for this violence is the identification of smugglers among the migrants. A 28-year-old Iraqi from Baghdad now living in Holland and interviewed by telephone, gave this account of his experience upon being apprehended on the shores of Lesvos Island October 28, 2007:

The smuggler told us to jump off the boat before landing. We had life vests of shabby quality. I thought we would drown; there was a woman with a child who almost died.

The Greek police caught us at 2 am. They beat everyone except the woman and the child. The police were dressed in blue. They kicked and clubbed us with long truncheons. They were trying to get us to confess who took us there. There were seven or eight police beating about 20 of us. The beating went on for about an hour. Then they put us on a bus and took us to a police station near the beach.

Someone in civilian clothes asked us more questions about who the smuggler was and how we got there. We gave our names and nationalities. We all said that we were Palestinians. We were still in wet clothes. We spent the night on the bus in our wet clothes. They gave us no dry clothes, no food, nothing to drink, not even for the children.[62]

The Greek police at the border can be especially brutal when they suspect a migrant of being a smuggler. An Iraqi Kurd who the Greek police expelled across the Evros River four times gives this account:

On the fourth time the Greek police beat me so much. One of the policemen recognized my face [from having been apprehended previously] and beat me so hard. He thought I was a smuggler. He beat me with a club and kicked me. One policeman did all the beating, but the others stood and watched and said nothing as he beat me. He beat me for 10 minutes. It was just beating to punish me because he thought I was a smuggler; he didn't ask me any questions or take my money.[63]

Orders to Leave

Rather than initiate a deportation procedure and enforce the removal of an undocumented migrant, the Greek authorities' usual practice is to detain the migrants and upon release from detention to hand them a paper which tells them to leave the country within 30 days.[64] This 30-day deadline for departure, commonly known as the "white paper," is written only in Greek, a language few of its recipients understand. The white paper seems to carry little weight as an enforcement document as individuals who do not comply with the "deadline" are simply provided with another white paper and are not formally removed through a judicially approved deportation proceeding or otherwise.

Undocumented people, by definition, lack the travel documents to leave the country legally, so if they are caught trying to leave they are arrested, detained again, and issued another white paper ordering them to leave the country within 30 days.[65] This happens repeatedly. Efthalia Pappa, program supervisor of the Ecumenical Program for Refugees, observed, "The 30-day paper is a paradox: It tells the person to leave the country and then the police arrest that same person for trying to leave the country."[66]

A 24-year-old Iraqi Kurd from Sulaymaniya interviewed while in detention in Petrou Ralli illustrates this paradox:

They arrested me and put me in jail for three months and gave me a paper to leave in 30 days. I got this paper three times. I have been in this country for two years and I've spent one year in jail. Each time [they release me] I'm given a paper to leave the country, but I can't leave because I have no [travel] documents. I want to leave the country, but I can't.[67]

A 28-year-old Iraqi man, deeply scarred by a bomb attack in Iraq, told about being re-arrested specifically for trying to leave Greece and being repeatedly detained, released, told to leave the country, caught trying to leave the country, and detained again:

After 35 days [of detention], they gave me the paper saying I had to leave the country in one month. That was October 27, 2007. Since then I have tried three times to leave from Patras but been arrested and jailed each time, the first time for one day, then for three days, and the third time for three months. I just got out on May 21, 2008 with another paper telling me I had to leave the country in one month.[68]

Human Rights Watch visited with this man on several occasions during our visit to Greece. On our last day we learned that he had left again for Patras and was trying once more to leave the country.

Official Deportations

The number of official deportations from Greece is small compared to the number of persons arrested for illegal entry or presence, the vast majority of whom are ordered to leave the country.[69] There are significant challenges to Greece's ability to deport undocumented foreigners.[70] Many migrants have no identity documents and give false names and nationalities. Determining their identities and correct nationalities can be time consuming and expensive.

Because the migrants' home countries are often poor and over-populated, their governments, desperate for remittances from their diasporas, have little capacity-or incentive-to cooperate in the return of their nationals. Greece, therefore, often finds it impossible to deport nationals of these countries within the three-month limit on administrative detention of migrants. Consequently nationalities that have no prospect for deportation are usually detained for less time than others. Afghans, Burmese, Palestinians, and Somalis-are held for shorter periods of time than those for whom Greece thinks it might be able to effectuate a deportation, such as Bangladeshis, Egyptians, Iranians, Pakistanis, and Sri Lankans. This is a primary reason for migrants to lie about their nationality. Even though Sudanese and Iraqis are not easily deported, they tend to be held for longer periods of time as well, according to testimonies from detainees.[71]

Despite the widespread fear among Iraqis of being deported, relatively few are officially deported from Greece. In 2007 Greece deported 405 Iraqis out of the 9,586 Iraqis who were "arrested to be deported."[72] Since Greece has not been able regularly to deport Iraqis directly to Iraq, this presumably reflects deportations to transit countries, such as air arrivals from Jordan. Because there are now direct air connections between Athens and Erbil through Viking Airlines, a private Scandinavian company that runs charter flights, it appears that some direct deportations from Greece to Iraq have taken place. However, since this connection is not permanent and flights are often interrupted, Greece has mainly sought to deport Iraqis to Turkey on the understanding that Turkey would be more likely to accept Iraqis (and Iranians) than other nationalities under its readmission agreement with Greece because of the relatively cheap and easy option of deporting them by bus across its southeastern land border.[73]

Returns under the Greece-Turkey Readmission Agreement

There have been relatively few formal, legal deportations from Greece to Turkey under the terms of the Greece-Turkey readmission agreement of 2001.[74] Brigadier General Constantinos Kordatos, commander of Hellenic Police Headquarters Aliens' Division, told Human Rights Watch that Greece has presented 38,000 cases to Turkey for readmission since the agreement went into effect in 2002, but that Turkey had only accepted 2,000 returns since that time.[75] A Turkish government source says that Greece has presented 22,312 requests for readmission between 2002 and 2007 and that Turkey has accepted 4,264.[76]

Even in obvious cases, such as a boat arrival on Lesvos or Samos, which are within eyesight of the Turkish coast, he said that Greece must still prove that the migrant came from Turkey. Kordatos said that another problem is the three-month limit on detention because Turkey takes longer than three months to decide whether to accept the return of a migrant, by which time the person has already been released from detention and is no longer in the custody of the Greek authorities for return.

Although by far the largest number of people interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that they had been summarily returned from Greece to Turkey, a few spoke about being returned under what appeared to be a formal procedure.[77] The common characteristic of these cases is that of naïve honesty: each person admitted to being an Iraqi national who had entered Greece via Turkey. An Iraqi Kurd who was deported from Greece to Turkey and from Turkey to Iraq, where he was arrested, jailed, and tortured, told Human Rights Watch, "Many Iraqis said they were Palestinians so they will not return you, but I didn't know this. I said I was an Iraqi. That was my mistake."[78]

Another Iraqi deported from Greece to Turkey was a 28-year-old member of the Sabean religious minority from Baghdad who fled following a death threat from the Mahdi Army. He was caught towards the end of 2006 by the Greek Coast Guard on an old fishing boat carrying about 150 people. The Coast Guard towed the sinking boat to the port of Lavrio where they held him in a camp for 10 days before transferring him to a jail near the airport in Athens. He said that he initially requested asylum, but that a lawyer told him that he would not be allowed to apply for his family as well, so he decided against applying. "I refused to ask only asylum for myself," he said. "I told them everything about being a Sabean and being afraid, but I did not ask for asylum."[79]

During his stay at the airport jail, he was told that the UN would come to visit, but they never did. He said that a private lawyer came, but asked for 600 euros to represent him, which the Sabean man could not afford.

Early one morning, the police came and told the Iraqi detainees that they would be taking them to a nice, open camp. He gave this account of the deportation:

They put about 80 of us on two blue buses. It was a 14-hour ride to Alexandroupolis. They wouldn't let us out of the bus the entire 14-hour ride. We had to urinate in bottles. During the ride they gave us only water, no food. When they stopped for the drivers and guards we offered to pay for them to buy us food, but they refused. We were handcuffed the whole time.

They took us to the border checkpoint; we saw Greek and Turkish flags. The Greeks turned us over to the Turkish authorities. The Turks behaved worse than the Greeks. They beat us and took our money. They even beat the women who were on the same bus. We were in handcuffs. No one resisted or we would be beaten more.[80]

The Turkish authorities subsequently bused the Sabean man and 64 other Iraqis to the border with Iraq and turned them over to the Iraqi Kurdish authorities who jailed and questioned them, and dumped them without any identification south of Kirkuk.[81]

Summary Forced Expulsions from the Evros Region

Summary forcible expulsions across the Evros River by Greek police and security forces are routine and systematic. The Turkish General Staff has reported that Greece "unlawfully deposited at our borders" nearly 12,000 third-country nationals between 2002 and 2007.[82] This number only indicates those migrants who the Turkish border authorities apprehended and registered; the number that Greece has summarily expelled is very likely to be higher. Human Rights Watch confirmed the systematic nature of the summary expulsions in 41 testimonies of migrants and asylum seekers interviewed in Greece and Turkey. Many of these individuals told Human Rights Watch of multiple entries into Greece and summary expulsions back to Turkey. The number and consistency of the accounts makes the presentation appear redundant. What follows are typical examples among the scores of interviews collected by Human Rights Watch.

A 29-year–old Moroccan being held at the Gaziosmanpaşa detention center in Kırklareli, Turkey gave an account that includes the main elements in almost all testimonies: 1) making multiple attempts to enter Greece and being caught in Greek territory and returned several or more times before succeeding in getting through; 2) being held for several days to a week at a police station in a border town in dirty, overcrowded conditions, where detainees are often mistreated and sometimes beaten; 3) being trucked in groups of 5o to 100 people to the river at nightfall; and 4) after Greek police officials see no sign of Turkish gendarmes on the other side of the river, being put on small boats in groups of 10 and sent across the river:

I wanted to have a better life and improve my conditions, and so I tried to go to Greece. I tried 10 times and was always captured and sent back. The first time was in February 2oo4. That time I spent 12 or 15 days in Greece and was caught and sent back. The last time I went I was returned from Greece on April 24, 2008. I walked four days to Orestiada, was caught and detained for one week by the Greeks. I was kept in the police station by the village. It was the border police who caught me. They don't let you speak. They just ask your name. There was no Arabic speaker there and no lawyer. No written document was given to me. They removed the sim card and battery from my phone, threw them away and gave the phone back to me.

There were 20 people in the room in the police station where I was held. It was crowded and the blankets were very dirty. There were mattresses on the floor. They behaved to us as though we weren't human. When you needed something and insisted a lot, they beat you really badly. This didn't happen to me, but the time before this when I was detained in Greece, there was a Tunisian guy who was sick and when he tried to say he was sick they beat him so badly he bled from the mouth and nose. I saw this happen.

At around 6 pm [April 23 or 24, 2008], we were put in a truck and taken at the border to the river. They slowly got us down from the truck and told us to be quiet and put us in a row. They were observing the other side of the river bank to see if there were any soldiers there. When there was none, they put us in a small boat driven by one person with another man standing in the front with a gun. It was around 10 persons to a boat and the boat was wooden with a motor. The person standing was in a uniform and the driver was a civilian. The driver spoke Turkish. Around 40 people were waiting by the river to be put into the boat that went back and forth carrying groups of ten. We crossed around 7 pm as it was getting dark.[83]

When forcibly returning migrants at the Evros River border, Greek police sometimes hit and kick them. A 34-year-old Turkoman from Kirkuk, who said that he made about 10 attempts to cross into Greece before succeeding, spoke about one of those episodes:

One time I crossed the river into Greece and arrived in Komotini. They put us in jail for five days and then took us to the river and pushed us back. We were 60 persons. They put us in a small river boat with a motor in groups of ten. They did it in the middle of the night. It was raining hard and the Greek police started beating us to make us move more quickly. I saw one man who tried to refuse to go on the boat, and they beat him and threw him in the river. They beat us with police clubs to get us to go on the boat.[84]

Similar summary expulsions have been reported from Greece to Bulgaria. In Embracing the Infidel: Stories of Muslim Migrants on the Journey West, Behzad Yaghmaian recounts the story of Purya, an Iranian migrant who entered Greek territory and wanted to seek asylum in Greece.[85] Purya thought the Greek police were taking him to Athens, only to discover that they were heading back to Bulgaria, where he was turned over to Bulgarian soldiers who beat him and subjected him to forced labor. On another attempt, the Bulgarians and their guard dogs caught Purya trying to leave, after which he was taken to a "torture room 'for those with multiple arrests,'" where he was severely beaten.[86] On a third attempt, he crossed into Greece and got as far as Thessaloniki, but the Greeks again returned him to the Bulgarian border. This time, however, the Bulgarians refused to accept him:

Not wishing to allow him in the country, and not able to deport him to Bulgaria, the Greeks had to find another country for him. Turkey was a natural candidate. Saved from the dogs and the beatings by the Bulgarians, Purya was returned to the beginning of his long journey. The Greeks took Purya to the border with Turkey, kept him in jail for two nights, and sent him to the Turkish side of the Meriç River[87] one evening in absolute darkness, without alarming the Turkish gendarmes.[88]

Greek Coast Guard Pushbacks

Migrant being rescued by the Hellenic Coast Guard in the Aegean Sea. Photo courtesy of the Hellenic Coast Guard/Intelligence Directorate

Although Human Rights Watch interviewed five migrants who were rescued and brought ashore by the Greek Coast Guard (some, but not all of those rescued also said that they were beaten or threatened with being shot), 10 other migrants told Human Rights Watch about uniformed guardsmen pushing them back into Turkish waters, puncturing their inflatable boats, as well as beating and robbing them. Another two migrants who the Greek Coast Guard returned to Turkish waters said that they had disabled their own boat.

While the testimonies do not provide the overwhelming picture of systemic summary returns of the kind seen on the land border with Turkey at the Evros River, these testimonies, together with testimonies gathered in July and August 2007 by the German NGO Pro Asyl and the Greek Group of Lawyers for the Rights of Refugees and Migrants and published in the October 2007 report "The truth may be bitter, but it must be told:" The Situation of Refugees in the Aegean and the Practices of the Greek Coast Guard,"[89] demonstrate that elements within the Greek Coast Guard do abuse and push back migrants, putting their lives at risk and denying asylum seekers among them even the possibility of asking for protection.[90] In a November 22, 2007 letter to the Ministry of Mercantile Marine, the Greek Ombudsman wrote:

The regularity of the complaints, the cross-reference and relevance of witnesses' reports of the incidents suggest, at the very least, that the prevention-containment-of illegal entry of foreigners occurring at the country's borders, particularly by sea, consists of one of the most controversial activities of the Greek authorities with regard to…human rights.[91]

The testimonies about Greek Coast Guard pushbacks vary in their details, but are consistent in telling how the actions of the Coast Guard, including puncturing of inflatable boats, removal of motors, and taking away oars before setting migrant vessels back in the water, sometimes without life vests, put their lives in danger.[92] A 28-year-old man from Baghdad who fled Iraq after his brother, who worked as a translator for the Americans, was kidnapped and killed by the slitting of his throat, told Human Rights Watch about his near-death experience after the Greek Coast Guard put him on a rubber boat, towed it towards the Turkish shore, and punctured it:

In August 2007, I went on a boat from Izmir. This was the first time I passed to Greek territory. We left from Ayvalık. The Greek navy stopped us.[93] They took away my mobile phone. They took my money. They beat me. They stripped me of my clothes except my underpants. There were about 20 of us on the boat. They did the same to the others that they did to me.

The navy took us to a small island. The island had one small building. There was one guy there, a shepherd. The building had a Greek flag. They didn't keep us there. About 5 am they took all our things. They took our telephones. They then divided us into two groups. There were two groups of 10 and 10. They took us from their big boat and put us in small Greek coast guard boats. They were rubber boats. They put us in the boats and then put little holes in the boat and left us alone.

I had had a life jacket when I came on the boat from Turkey, but the Greek navy men cut up that life jacket. They were looking for money inside it. They cut it with a knife searching for money. They gave us a new life jacket when they put us in the rubber boat. The life jacket had no identification showing it was from Greece.

This was not the boat we came in. They put us in a rubber boat that belonged to the navy. They removed our clothes. They took us out about one hour to a place near Dikili. They took us close enough so we could see the Turkish coast. We could see a Turkish flag on the coast.

They gave us oars to row the boat that they put small holes in. The boat could stay afloat for about one hour. When they put us out, we could see the Turkish flag on the shore. We could actually see a Turkish flag.

We did not see the other group of 10 people in the other rubber boat. They arrived in Turkey before us and asked the Turkish coast guard to save us. By the time the Turkish coast guard got to us the boat had already sunk. One guy, Mustafa, had already died. I almost drowned. I had a life jacket but I couldn't swim.[94]