Summary

I go [to the gold processing site] at 6 a.m. and come back at 5 p.m. I have a break at lunchtime. I am very tired from it. Sometimes I buy painkillers to soothe the pain in my back and chest….I sell the gold to a buyer, his name is [name withheld]…. [I sell to him] at his house. He does not ask about my age. The trader also gives me mercury.

—“Kwame,” 12, Homase, Amansie Central district, April 2014

All I need to know is the gold is coming and that it is real gold.

—Trader, Dunkwa-on-Offin, April 2014

Ghana is one of the world’s top 10 gold producers. Many traders and refiners prefer to source gold from Ghana—a stable democracy—rather than from controversial conflict-affected regions. However, companies that do buy gold from Ghana risk benefiting from hazardous child labor.

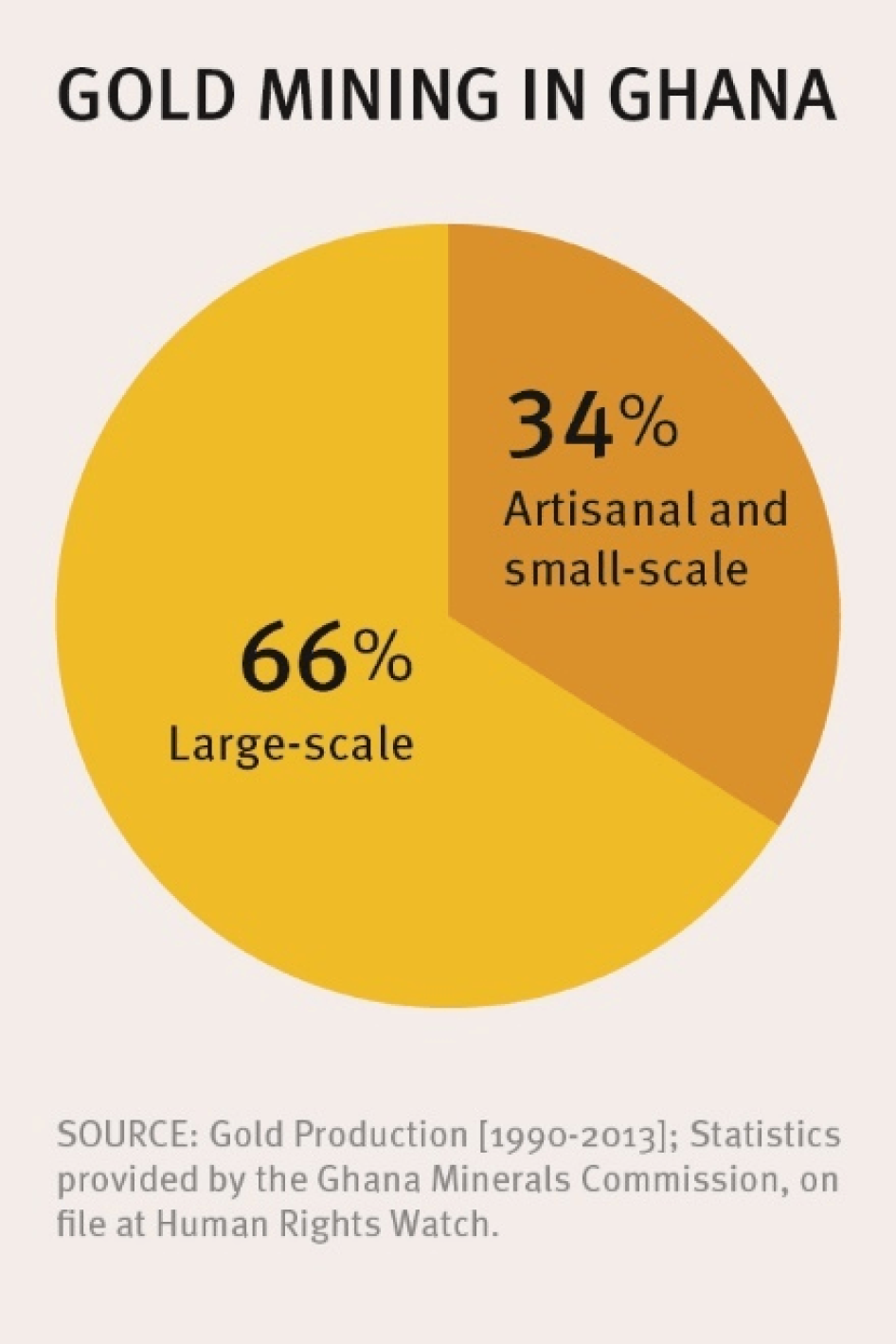

Around one-third of Ghana’s gold is mined in artisanal and small-scale mines, locally called galamsey, and exported at a trade value well above US$1 billion per year. Artisanal and small-scale mines operate with simple machinery, limited investment, and a large workforce. Most of these mines operate illegally without a license and belong to the informal sector. They offer important income opportunities for Ghana’s rural populations, but also encourage hazardous child labor and cause serious environmental damage.

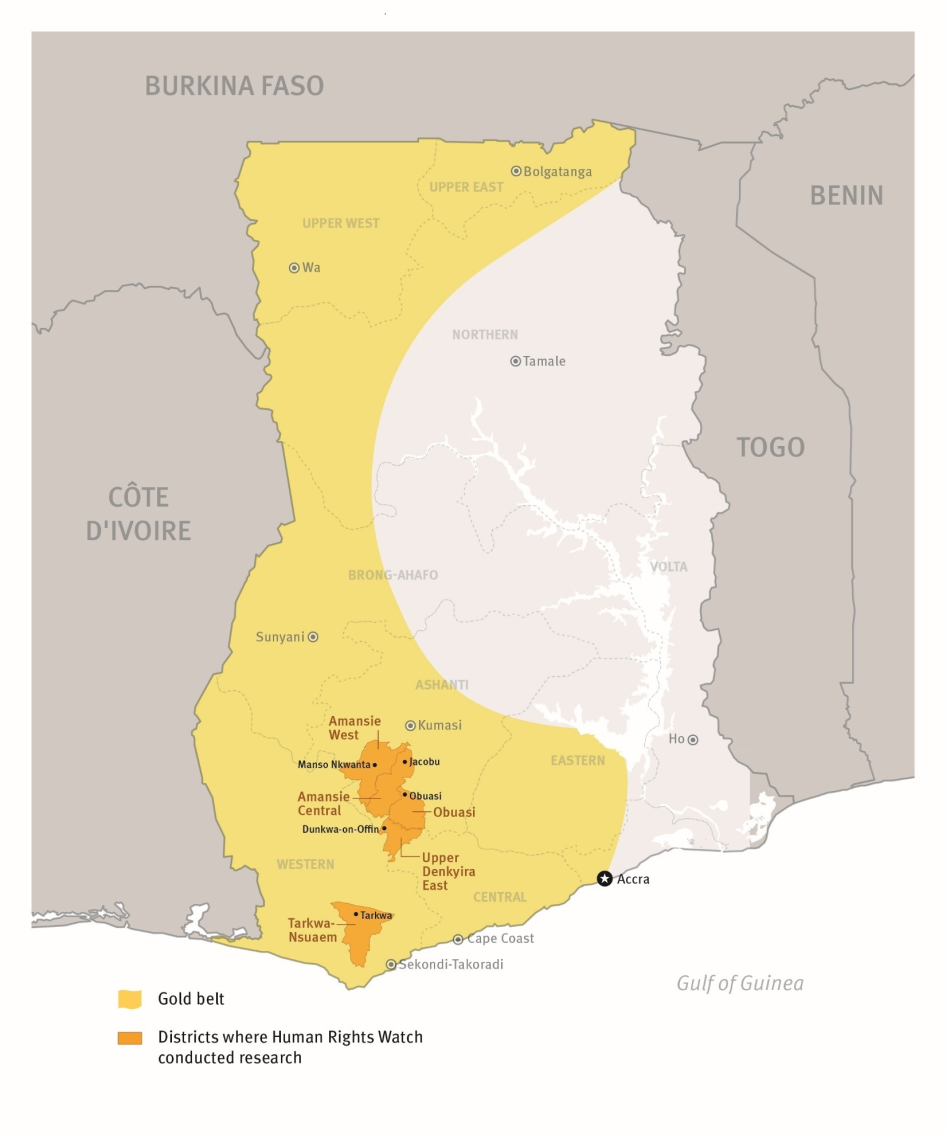

This report documents the use of child labor in artisanal and small-scale mines in Ghana’s Western, Central, and Ashanti Regions, focusing on unlicensed sites, which constitute the vast majority of mines. It also analyzes the measures that some gold traders and refiners take to avoid supporting child labor by buying gold mined with child labor.

Thousands of children work in Ghana’s artisanal and small-scale gold mines in hazardous conditions, despite both Ghanaian and international law prohibiting hazardous child labor. Most children are aged 15 to 17, but younger children work in mining too. The youngest child interviewed by Human Rights Watch was 9 years old.

Children work alongside family members, are sent to work by their families, or work on their own. They work anything from a few hours to 14 hours a day, pulling the gold ore out of shafts, carrying heavy loads of ore, and crushing it. Children wash the ore on a sluice (a board) and pan it. Finally, they work with mercury, a highly toxic metal, by amalgamating it with gold and then burning the amalgam to separate out the gold.

Children suffer numerous health consequences from mining work. The heavy lifting causes pain in the back, head, neck, joints, and arms, and can lead to long-term spinal damage. Some children suffer from respiratory disease as a result of the dust produced from crushing ore. Children have been injured in mine collapses, when working with sharp tools, and during other accidents. In April 2013, a 17-year-old boy was killed by a mudslide at a mine near Dunkwa-on-Offin, Central Region.

Children working with gold are often exposed to high levels of mercury. Mercury attacks the central nervous system and can cause lifelong disability, including brain damage, and even death. Mercury is particularly harmful to children, but is readily available in some gold trading shops and provided by gold traders to child laborers. Children—and adults—have limited and sometimes false information about mercury, and usually do not know its risks or how to protect themselves properly from this toxic metal.

While the majority of children working in mining are boys, girls mine gold too or do other jobs on mining sites, such as selling food or other items. They face the additional risk of sexual harassment, sexual exploitation, and rape.

Most children that work in mining attend school, and some children work specifically to earn money for school-related costs. However, many children attend school irregularly, skipping classes or entire school days. Other children drop out of school altogether. Mining managers and machine owners usually consider work by young children during school hours as unacceptable and have occasionally sent children away. At the same time, many mine managers often do not object to work by school-going adolescents and by younger children outside school hours, and sometimes employ them on their sites.

Child labor in Ghana’s gold mines violates Ghana’s Children’s Act, which prohibits work in mining for anyone under the age of 18. Child labor in mining also violates Ghana’s international legal obligations. The International Labour Organization (ILO) defines child labor as work that deprives children of their childhood, their potential and their dignity, that is harmful to their physical and mental development, and that interferes with their schooling. ILO Convention No. 182 prohibits the “worst forms of child labor” for anyone under the age of 18—that is, work that is likely to harm the health, safety, or morals of children, by its nature or the circumstances in which it is carried out. The worst forms of child labor include hazardous work, specifically mining activities such as work underground, work with dangerous machinery and tools, transport of heavy loads, and work that exposes children to hazardous substances.

Traders buy gold at or near Ghana’s artisanal and small-scale mines, and then sell it to other parties. The global trade in gold from artisanal and small-scale mining can be compared to a funnel: Gold from many different locations, bought by many traders, gets traded to fewer and fewer companies, until it reaches the refinery. The refiners hold a key position: 90 percent of the world’s gold gets refined by fewer than 10 companies. Most of Ghana’s artisanal mined gold is eventually exported to international gold trading or refining companies based in Switzerland, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and other locations. After refining, the gold gets traded to banks, jewelry businesses, the electronics industry, and other enterprises.

Human Rights Watch interviewed traders in Ghana as well as global refineries about the steps they took to prevent gold mined by children entering into the supply chain. In addition, Human Rights Watch sent letters to Ghanaian exporters and international refiners to inform them about our research findings on child labor and to ask them about their human rights due diligence policies and procedures.

Human Rights Watch found that local traders at mines or in mining towns had little or no procedures in place to ensure that they did not benefit from child labor. Several traders stated that they were buying or sourcing from unlicensed mining sites. Some were also buying gold directly from children. In contrast, Ghana’s largest four gold exporting companies told Human Rights Watch that they had processes in place to ensure that the gold they were buying was legally produced: The companies were buying gold mostly—but not exclusively—at licensed mines. However, Human Rights Watch found that these processes were not sufficient to eliminate the risk of child labor in the supply chain, though some companies managed to significantly reduce the risk.

Furthermore, the government-owned gold trading company, the Precious Metals Marketing Company (PMMC), has poor due diligence procedures. The PMMC also provides trading licenses to about 700 individual buying agents and trading companies without requiring traders to use any human rights criteria when purchasing gold. PMMC officials stated they were aware that traders buy from sites without a mining license. The government Minerals Commission provides export licenses and also does not require human rights due diligence.

Human Rights Watch also analyzed the due diligence policies and procedures of six international refiners that source from Ghana: Metalor (Switzerland), Produits Artistiques Métaux Précieux (Switzerland), Kaloti Jewellery International (UAE), Emirates Gold (UAE), Kundan (India), and Rand Refinery (South Africa). Human Rights Watch found that several of these companies had varying weaknesses in their due diligence procedures, such as a lack of systematic child labor monitoring or a lack of transparency. Human Rights Watch focused on these refiners because its research found that they were sourcing from Ghana. However, there may be other refiners sourcing from Ghana who are not mentioned in this report.

Under the United Nations Guiding Principles for Business and Human Rights, companies should put in place robust human rights due diligence—that is, a process to identify, prevent, mitigate, and account for the company’s impacts on human rights, including child labor. With regard to gold from conflict-affected areas, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) has developed a detailed due diligence guidance. While the OECD guidance is largely focused on preventing mass atrocities during armed conflict, it provides important guidance on how to establish human rights due diligence more broadly.

While the government of Ghana has made some efforts to address child labor in mining, its systems to monitor and eliminate child labor function poorly. Inspections for child labor are not systematic, and government institutions dealing with child labor or child protection are weak and underfunded. School enrollment rates in Ghana have risen over the last two decades and are above the regional average. Still, government funds for free public education are inadequate and sometimes do not reach the schools in a timely manner. As a result, schools levy various fees in violation of Ghanaian and international law, which undermine the right to free education. Children who cannot afford the fees often work in gold mines as an alternative, or work in the mines specifically to earn money to continue their education.

The government of Ghana—with the support of international donors and UN agencies—should improve existing systems for child labor monitoring and child protection and enforce child labor laws. The underlying causes of child labor need to be addressed, for example, through social protection programs, appropriate youth employment options, and efforts to make primary education truly free of charge.

Child labor also occurs in artisanal and small-scale mining and trade because the sector is poorly regulated. Most mines operate illegally without a license, which can be costly and often nearly impossible to obtain because large-scale mining companies or other entities already have a claim on available land that may be suitable for mining. Child labor is rare in licensed, formalized mines, according to nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) working in the mining sector.

The government has not undertaken the fundamental reform that is needed to regulate, professionalize, and formalize the artisanal and small-scale mining sector. It allows the trade and use of mercury for gold mining, a powerful pollutant and health threat. Existing labor, environment, and other regulations are not enforced, resulting in a regulatory collapse. Local chiefs and authorities in particular have allowed mines to operate without license, and have been accused of accepting bribes. In parallel to this laissez-faire approach, the government has started to shut down unlicensed mines without seeking a dialogue with illegal mining operations about obtaining licenses and abiding by the law. In some instances, illegal miners have obtained arms and attacked security forces.

Together with donors, companies, and NGOs, the government should develop a comprehensive strategy for a clean, professional, and child labor-free artisanal and small-scale mining sector. This should include steps to formalize unlicensed sites; better enforce regulations on child labor and other issues; and establish a robust due diligence process for the gold trade, including the government-owned Precious Minerals Marketing Company (PMMC). With regard to the use of mercury, the government should promptly ratify the Minamata Convention on Mercury and implement its key elements, including introducing mercury-free gold processing techniques.

Human Rights Watch does not recommend a boycott on gold from Ghana. However, Ghanaian companies and gold refiners—who hold important leverage due to their central position in the global gold supply chain—should take action to end the use of child labor in the mines. They should immediately establish effective due diligence procedures for the whole supply chain to prevent the use of child labor, conduct awareness-raising, and training with their suppliers, and make sure they are in full control of their supply chain.

Key Recommendations

To the Government of Ghana

- Enforce the ban on child labor in mining by ensuring that labor inspectors and district and community child protection committees have an adequate mandate and resources to conduct on-site inspections and otherwise monitor child labor.

- Improve access to education by ensuring free access to primary and junior high schools, and making sure that Ghana’s Livelihood Empowerment against Poverty (LEAP) cash transfer program reaches vulnerable children in mining areas.

- Formalize artisanal and small-scale gold mining by developing a comprehensive strategy to permit a simpler and quicker procedure to obtain a mining license, and provide technical support to such miners to help increase household income.

- Prevent, test, and treat mercury exposure by ratifying and implementing the Minamata Convention on Mercury, introducing mercury-free gold processing methods to mining communities, and boosting health system capacity to address mercury exposure.

- Establish a due diligence procedure at the government’s Precious Minerals Marketing Company (PMMC) to identify child labor and other human rights risks in the supply chain, and require human rights due diligence from companies applying for a trading or export license at the Minerals Commission.

To Companies, including International Refiners

- Strengthen due diligence procedures to identify child labor and other human rights risks in gold supply chains, including by having a strong company policy on human rights; full chain-of-custody documentation; regular monitoring and inspections; contracts with suppliers prohibiting the use of child labor; and qualified third-party monitoring for child labor in supply chains in all countries.

Methodology

Human Rights Watch conducted field research for this report in June 2013, March-April 2014, and June 2014 in southwestern Ghana. We went to Tarkwa-Nsuaem Municipal district (Western Region), Upper Denkyira East Municipal district (Central Region), Amansie Central district, Amansie West district, and Obuasi Municipal district (all Ashanti Region).

Human Rights Watch visited 10 artisanal and small-scale gold mining and processing sites and interviewed over 160 people, including 44 child miners between the ages of 9 and 17.[1] Of these child laborers, 40 were boys and 4 were girls. In addition, we interviewed three girls that performed other jobs on mines, such as selling items or providing childcare for younger siblings. We also spoke to five young adults between the ages of 18 and 21 who had worked as children in gold mining and processing.

To investigate the role of traders, Human Rights Watch conducted interviews with 20 gold traders at mining sites, in mining towns such as Tarkwa, Obuasi, and Dunkwa-on-Offin, and in the capital, Accra. In addition, Human Rights Watch interviewed the director and a branch office staff member of the government-owned gold trading company, the PMMC, and met with gold trading and refining companies from Switzerland and Dubai.

Human Rights Watch interviewed a wide range of government officials, including the minister of gender, children and social protection and representatives of the Ministry of Employment and Labour Relations, the Ministry of Lands and Natural Resources, the Minerals Commission, the Environmental Protection Agency, the Education Service and the Department of Social Welfare, as well as district chief executive officers and other district authorities. We also spoke to parents and guardians of child laborers, adult miners, representatives of miners’ associations, teachers and principals, health workers and health experts, NGO activists, mining experts, and representatives of UN agencies and donor governments. Outside Ghana, Human Rights Watch interviewed several international experts on artisanal and small-scale gold mining and the gold trade.

Where possible, Human Rights Watch carried out interviews with children in a private setting, without others present. Because of the difficulty of maintaining privacy on mining sites, some interviews were conducted in the presence of a few adult miners and other children. Interviews were conducted in Twi and Wasa through the help of an interpreter. Interviewees were not compensated for speaking to us.

One challenge during this research was assessing children’s ages, which some did not know exactly. In such cases, researchers sometimes sought advice from parents or other members of the community to estimate the child’s age.

The names of all children have been replaced with pseudonyms to protect their privacy.

I. Background: Gold Mining in Ghana

Ghana has been shaped by gold throughout its history.[2] Named “Gold Coast” during the European colonial period, today it is Africa’s second biggest producer, after South Africa, and the world’s seventh largest gold producer globally.[3]

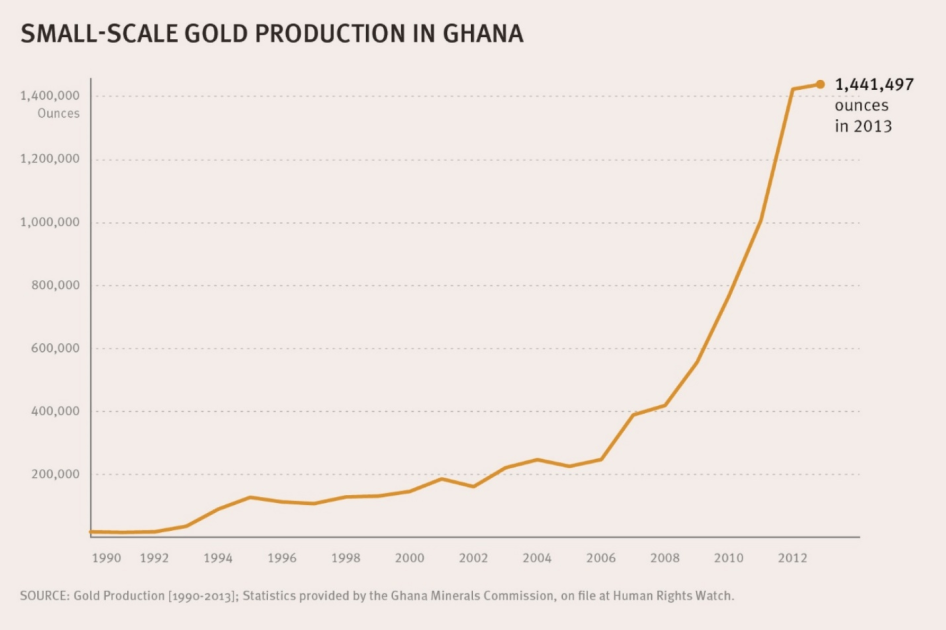

In 2013, Ghana produced about 119 tons of gold, the production of which contributes about 11 percent to Ghana’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP).[4] About one-third (34 percent) of Ghana’s gold comes from artisanal and small-scale gold mining, and nearly all of it is exported.[5] In 2013, 40.7 tons of gold from the artisanal and small-scale gold mining sector were exported, at a trade value of US$1.7 billion.[6]

Most of Ghana’s gold is produced by a few large foreign mining companies, including the South African companies, Anglo Gold Ashanti and Gold Fields, the US company, Newmont, and Canadian companies, Golden Star Resources and Adamus.[7] These large-scale industrial-style mining operations use open pit and underground mining, and are highly mechanized. While an important sector of employment, the presence of large-scale mining companies has also led to protest against the social and environmental impact of industrial mining, and has caused conflicts with artisanal miners.[8]

Artisanal and small-scale mining is defined as mining with limited investment, simple machinery, and a large workforce. Estimates put the number of artisanal and small-scale miners in Ghana between 500,000 and 1 million.[9] While some mines work without machinery at all, many others use simple machines for pumping water out of pits and for grinding ore. The mines are not owned by one individual or company, but are frequently controlled by an individual or a small group that provides machines to the mine. Machine owners employ people and get a share of the gold mined; sometimes they also trade in gold. The owner of the land also sometimes receives a share of the gold produced.[10]

In Ghana, artisanal mining and miners are commonly called “galamsey” (stemming from the words “gather and sell”). Sometimes, the term describes more narrowly illegal mining, whereas the term “small-scale mining” is used to describe legal operations, based on the language of the mining law.

This report uses the terms “artisanal” and “small-scale” mining broadly, without differentiating between legal and illegal gold mining operations.

II. Child Labor in Artisanal and Small-Scale Gold Mining

A 2014 Ghanaian government survey reported that about 22 percent of children in Ghana are involved in child labor and 14 percent are involved in hazardous work.[14] Most children work in agriculture, including the country’s significant cocoa production. Children also work in fishing, domestic service, mining, quarries, porterage of heavy loads, and other occupations. Some children, in particular those working in fishing, are at risk of being trafficked and enslaved.[15]

It is estimated that several thousand children work in Ghana’s artisanal and small-scale gold mining sector, though data is scarce.[16] There are many more boys than girls working in mining.[17] While the majority of child laborers are between the ages of 15 and 17, younger children work in gold mining too. Of 44 child miners interviewed by Human Rights Watch, 20 had started working at the age of 12 or younger. The youngest child miner Human Rights Watch interviewed was 9 years old. A survey by the International Labour Organization (ILO) of 400 child miners found that most child miners—61 percent—were adolescents between the ages of 15 and 17. One-third of miners were between the ages of 10 and 14, and nearly 6 percent of children were between 5 and 9 years old.[18] Artisanal and small-scale gold mining takes place in many parts of Ghana—including in Western, Central, Ashanti, Eastern, Brong Ahafo, Northern, and Upper East Regions. Child labor in mining occurs in all these areas.[19]

Causes of Child Labor in Mining

Family poverty is one of the main causes for child labor. Some children are sent to work by their family or work alongside family members, while others work on their own. Children in families of artisanal miners are more likely than others to work in mining.[20]

Human Rights Watch found that children work in mining to increase family income, to earn some money on their own, and to earn money for school fees or school-related costs. Children living with a single parent, with a relative or guardian, or alone, were more likely to be engaged in child labor. [21] Adama, 14, told Human Rights Watch:

I started working at the age of 10…. My father died and my mother was not able to take care of all of us. I realized other children were going to the mines to help their families, so I decided to join them.[22]

The ILO study on children working in mining found that children living with relatives or guardians were less well taken care of than those living with a parent, and hence more likely to work.[23] Human Rights Watch also found child neglect to be a cause for child labor. Ellen, 15, who was carrying heavy loads at a gold mining site, told Human Rights Watch:

My mother and father are divorced. My mother remarried a man with four children and can’t take care of me. My father also remarried and doesn’t take care of me. I came here alone.[24]

Some children worked specifically to raise money for schooling.[25] For example, 17-year-old Susanna carried heavy loads of mud ore to earn the cost of secondary school admission, 800 cedis (US$250).[26]

Although primary and junior public high schools are officially free of charge in Ghana, they charge smaller informal fees for books, printing, parent-teacher association dues, and other items. Children told Human Rights Watch that they were working in order to raise the money for these costs, as well as for their lunch during the school day. Other studies have also found that children worked in mining to pay for education-related costs.[27]

Anna, 16, has been working in artisanal and small-scale gold mining since she was 14. She told Human Rights Watch:

I work because my mother does not have money. I have to pay PTA [parent-teacher association] dues and other school material. Sometimes I earn 50-60 cedis (US$15-18) in three weeks, together with my mum. I also use some [money] as chop money.[28]

Even younger children spoke of the need to raise money for school-related costs. For example, 12-year-old Paul told Human Rights Watch that he worked to earn money for a school uniform.[29]

Child labor also takes place because there is little awareness of the harms associated with child labor and of the relevant laws in Ghana. Human Rights Watch found that child laborers were often unaware of the hazards of mining work, including mercury exposure. They only fully realized the dangers when lives were lost, such as during a mining accident in April 2013.[30] A baseline survey conducted among artisanal and small-scale mining communities in Ashanti Region found that less than 5 percent of people interviewed about child labor were able to identify suitable and hazardous (non-suitable) work for children.[31]

Another cause of child labor in gold mines is that it attracts children; they sometimes organize themselves in groups and are proud of their skills and the money they earn.[32] While some children told us that they handed over the money earned to their families, others used it to obtain items they would otherwise not be able to get, such as clothes, soccer shoes, or even a mobile phone.[33] While many parents readily accepted their child’s work in mining, others opposed it or threatened punishment.[34] But as children start to earn their own money, parents lose influence and control over them.[35]

Pay

While some children worked independently and processed gold by themselves, selling it directly to traders, others were employed and paid by adults for specific tasks. The amount of money earned in gold mining varied greatly. Half of the children interviewed indicated that they earned between 5 and 20 cedis ($1.50 and $6.25) for a day’s work. Some children earned more, while others earned less or nothing.

Child laborers who were employed to carry, shovel, wash, pan, or amalgamate the ore were typically paid a daily wage. Those carrying loads of ore in pans or sacks were usually paid for the number of loads carried per day.[36] The payment varied dramatically even in the same location, and seemed arbitrarily set. For example, three children carrying pans of mud on their heads up a hill at the same mine were paid 7 cedis ($2.20) for 27, 25, and 50 loads respectively.[37]

Some children were paid irregularly. Ellen, 15, who was among those carrying loads of gold ore up a steep hill, told Human Rights Watch:

I carry loads…. If you carry 50 per day you get 7 cedis, if you carry 100 you get 14 cedis, so I try to carry 100 a day…. I typically work four or five days a week…. I always feel pain in my head and my chest. I don’t buy drugs because I don’t have enough money…. Sometimes I don’t have money, so I carry the load with an empty stomach. If I have money, I buy food in the morning and in the evening, but if no money, depend on friends. If they don’t give me food, I sleep with an empty stomach. [The last time] I was paid [was] two weeks ago.[38]

Some children worked in a group and sold the processed raw gold directly to traders.[39] Human Rights Watch also interviewed one boy who described himself as the “ghetto owner”—that is, a person managing a pit and employing others to work there for him.[40]

Working Hours

Many children do not work in mining full-time, but try to combine school and mining work. Common periods when children mine are after school, during the weekend, and vacations. Others, however, work in mining six or seven days a week.[41]

Several children told Human Rights Watch that they worked between 7 and 14 hours per day. Twelve-year-old Kwame was carrying, crushing, and washing loads of gold ore. He explained his work at a processing site in Amansie Central district:

I go at 6 a.m. and come back at 5 p.m. I have a break at lunchtime. I am very tired from it. Sometimes I buy painkillers to soothe the pain in my back and chest.[42]

Several older boys working in the same location also worked very long hours. One of them, Faruk, 14, explained that he carried loads of ore up to 14 hours a day:

It was a difficult job, there was no time to rest. [We] worked from 6 a.m. to 8 p.m. … If we finished the job early, we would have time to eat, but if we didn’t finish, kept working. Sometimes we worked from 6 a.m. to 8 p.m. with no break.[43]

A boy in Obuasi went to the processing site after school and spent many hours a day “washing” (processing) gold ore. He said:

You hold a pipe up with one hand and wash with the other for hours at a time. You don’t rest until the load is finished. If there is another load waiting, you have to start it right away. But if there is no load waiting, you can rest…[I wash] up to five loads per day. The load owner pays us.[44]

The Hazardous Nature of Mining Work

I don’t like it anymore because of the way people are dying.

— Dustin, 12, Kyekyewere, Upper Denkyira East Municipal district, June 2013

Work in mining is considered one of the most hazardous forms of work by the ILO, due to the risks connected to accidents, pit collapses, the use of dangerous chemicals, the inhalation of dust, and other factors.[45] Human Rights Watch’s research found that the main tasks performed by children in gold mining in Ghana are:

- Pulling up and carrying loads of ore[46]

- Shoveling ore

- Crushing ore

- Washing ore (on a sluice or wooden board)

- Panning or “shanking”

- Amalgamating ore

- Burning the amalgam

Pain

Many of the tasks that child miners perform cause them physical pain. In particular, carrying or lifting heavy loads can be harmful if the load exceeds the body’s physical ability and can cause immediate pain as well as long-term damage to muscles and bones.[47] The district director of health services in Obuasi explained that his medical staff see neck and body pain in adolescent boys who work in artisanal and small-scale mining.[48] About half of the child laborers Human Rights Watch interviewed said they experienced pain in the neck, shoulders, arms, fingers, chest, back, waist, or in the whole body.

Nine-year-old Zachary has been shoveling loads of ore onto a washing board. He said, “When I went there [to the processing site], I started by 7 a.m. and ended by 5 p.m…. I felt pain at the sides and waist.”[49]

Paul, 12, suffered an injury from carrying loads at a mine, where he worked with his father. He said he took nine days to recover.[50]

Older children also complained about daily pains. Thomas, 15, carried loads from grinding machines to a washing place, and then washed the ore on a board. He said, “It is hard work. After carrying the load to the washing place, I feel pain in my back and my neck, and the whole body.”[51]

Lung Conditions

Artisanal and small-scale gold mines are nearly always dusty, which can cause long-term health problems, such as coughs, tuberculosis, silicosis, or other lung conditions.[52] Miners interviewed for a study in northern Ghana reported higher incidences of lung disease and coughing.[53] A health official in Ashanti Region listed coughs as one of the conditions he treats in child and adult miners.[54]

Samuel, who is 16 years old and small for his age, has been working in artisanal and small-scale gold mining since he was 11 to support himself. He stopped after the government crackdown on mining because activity was slow. He told Human Rights Watch about the daily work in which he had been involved:

It [the work] is difficult, because I work at the crushing site, and there is smoke from machines, the machines are hot, and I inhale the dust…. After inhaling the dust and fumes, and I go home to sleep, in the morning I see blood in my spit. It can last for a week after working. I also get a cough that can last for a week. Once I missed a whole week of school. I went to the doctor twice.[55]

Martin, 17, said:

Before, I had a cough and my phlegm had red blood stains in it. This can last for three weeks. The cough could last three days in a row…. I didn’t go to a doctor, but I went to the pharmacist. He gave me some medication, and he also advised me not to work at the galamsey. He said it was dangerous. But I didn’t stop because I needed the money.[56]

Martin stopped working in 2013 due to the slowdown of mining activity. After that, the cough stopped.[57]

Accidents

Accidents such as cave-ins and pit collapses occur regularly in Ghana’s artisanal and small-scale mines and are estimated to have killed over 300 people in 2011 and 2012 alone, according to a government estimate.[58]

A study of 72 small-scale miners seeking emergency department hospital care found that mine collapses accounted for nearly 13 percent of injuries, and explosive blasts for 10 percent of injuries. Three percent of the injuries were fatal. Miners sought care for various conditions including fractures, spinal cord injuries, and lacerations.[59]

In March 2014, a radio station in Ghana reported that a one-year-old child—who had been taken by her parents to the mine—was killed with four adults at a mine in Amansie Central district, Ashanti Region.[60]

Almost a year earlier, on April 15, 2013, a major accident occurred at a gold mine near Kyekyewere, Upper Denkyira East Municipal district, Central Ghana. At about 6:45 a.m., a mud wall collapsed in an open pit gold mine where over 20 people were working. A few miners were pulled from the mud with injuries but 16 died.[61] Among the victims was Abroso Kwabena Donkor, a 17-year-old orphan who had dropped out of school at the age of 15 to work in the mines. He had been living with his maternal aunt after his mother’s death. His aunt, who also worked at the site and survived, said:

When I was stacking the mud, I realized the ground was soft. I suggested to a colleague to surround the mud with some stones. As I called my colleague to help with this, I heard the sound of the pit collapsing.[62]

Abroso’s aunt fell and was injured in the leg. Abroso, who stood nearby, was buried in the mud. One survivor commented that boys regularly worked at the Kyekyewere mining site, though the other victims of this incident were adults.[63]

After the accident, many children realized the real risks of the work and some stopped working in mining for a while. A 12-year-old boy who had worked at the mine said, “I don’t like it anymore because of the way people are dying.”[64]

In addition to mud slides and pit collapses, child and adult laborers are at risk of injury from tools, machines, and rocks. Thomas, 15, told Human Rights Watch how he had repeatedly hurt his hands: “I use a hammer for crushing. Sometimes I have had accidents with the hammer…. I went to hospital once [and] was treated for an injury.”[65]

Albert, 14, said that when he was 10 he was injured when a rock fell on his knee.[66]

Mercury

Most artisanal and small-scale miners in Ghana, including child laborers, use mercury to process the gold because it can separate the gold from the other minerals easily and cheaply. Child and adult miners mix the liquid mercury into the ore, where it attracts the gold particles and forms an amalgam. Then, they place the amalgam on a fire and burn off the mercury, leaving raw gold.

Mercury attacks the central nervous system and can cause lifelong disability, including brain damage. Higher levels of mercury exposure may result in kidney failure, respiratory failure, and death. Mercury is particularly harmful to children, as their systems are still developing, and its damage is irreversible. The younger the child, the more serious the risk. In utero exposure can occur when pregnant women are exposed to mercury and can present immediate and life-long negative health consequences.[67] Studies indicate that artisanal and small-scale gold miners in Ghana have a significantly higher burden of mercury than residents who live or work in mining areas.[68]

A little over half of the children interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that they worked with mercury. The ILO found in its study that 27 percent of child laborers surveyed worked with chemicals, and that mercury was the most common chemical used.[69] An adult miner told Human Rights Watch about a common division of labor:

The children wash the mineral…. They do the processing with mercury. They know the work better than the older ones. When they finish the burning, they sell the gold to the traders.[70]

Zachary, 9, was the youngest child laborer interviewed by Human Rights Watch. He explained how he worked with mercury: “I spread the mercury with the hand. Then I tie it [the amalgam] up with a rag…. Then I come out with gold and mercury. You put it in the fire and smoke it.”[71]

One 12-year-old boy, Kwame, showed a small flask of mercury that he was carrying in his trousers’ pocket. He worked to earn money for his mother and five younger siblings. He described how he sometimes burned the mercury at home, a particularly harmful practice that puts children and others at risk: “I use [my] hand to spread the mercury. Then I create the amalgam…. I burn it on my own, where I get fire, at my mother’s house or any place.”[72]

Children obtained mercury from local gold traders who bought the raw gold from them.[73] None of the child laborers interviewed knew how to protect themselves properly from mercury. Some had never heard that mercury is harmful.[74] Others had false or incomplete information. Some traders who provided children with mercury had told them only that mercury is dangerous when swallowed.[75] Samuel, 12, said, “I know mercury is dangerous… I should not let it touch my mouth.”[76] While swallowing mercury can indeed by harmful, the most serious health risk stems from the invisible mercury vapor that develops when the amalgam is burned.[77]

Sometimes, local trading shops buy the gold-mercury amalgam and burn it at their workshop. They often have one person, called a “kitchen boy,” doing this work. While many kitchen boys were actually adult men, Human Rights Watch spoke to one kitchen boy who had started working in this job at the age of 16.[78]

A common symptom of mercury poisoning is the development of tremors (twitching).[79] Human Rights Watch interviewed a 19-year-old miner who may have been suffering from the effects of mercury exposure. Ibrahim started working with mercury at age 17 and had a tremor in his hands. He found it hard to write as a result.[80] He said:

I was told [by the group leader] if you work with mercury for a long period and especially baking gold and use your bare hands, your fingers will start shaking…. It happens often…. It affects my writing.[81]

Sexual Exploitation

Girls who are present on or near artisanal and small-scale mining sites are vulnerable to sexual harassment, sexual exploitation, and rape. Adult miners frequently form relationships with girls, and mining areas are centers of commercial sexual exploitation.[82] According to the Domestic Violence and Victim Support Unit (DOVVSU) in Obuasi, rape and defilement—that is, sexual relations with anyone under the age of 16—are frequent in mining areas.[83]

Ellen, who is 15 years old and carries loads of ore, told Human Rights Watch that she is sometimes approached for sex, but that she refused each time:

Some guys want to be with me…. Sometimes [men] touch me. I complain, but they still do it. They touch me on my breasts and buttocks. I feel very bad, I don’t like that.[84]

Jacqueline, 17, told Human Rights Watch that men approached her for sex at the mine where she worked. When she refused, they told her not to come and work at the site anymore; she continued to work anyway.[85] Human Rights Watch also interviewed a 14-year-old girl who was pregnant from a mine worker. She had dropped out of school and was instead working for the aunt of the man, selling food at a mining site.[86]

Impact on Education

Most child laborers go to school and work in mining at the same time. However, they often attend school irregularly, skipping classes or entire school days. Some drop out of school altogether. Other children work specifically to earn money that allows them to pay school-related costs and continue their education.

Combining work and school is hard for many children as they have no time left for study at home, or suffer from mining-related sickness or exhaustion. The ILO survey found that of 400 child miners, 65 percent were attending school and 35 percent were not in school. Almost half of the child laborers going to school said that they did not attend regularly.[87] Denying children their right to an education ultimately decreases their future employment opportunities and earning potential as an adult.[88]

Human Rights Watch spoke with Anna, who—despite being 16—was only in fifth grade of primary school. She went to the mining site with her mother before school or skipped school entirely. She said:

Sometimes I do not go to school and work at the site. Later when I come to school after that, the teacher advises me to stop working. It affects my performance….It distracts my schooling. After going to the site at dawn, and then going to school, I sometimes sleep in class.[89]

Eric, 17, who was attending the last year of junior high school, said, “I did well at school but when I started [mining], my performance went down because I did not have the time to study after coming back from the site, I was tired then.”[90]

Some children dropped out of school once they started mining. About a third of the 44 children interviewed by Human Rights Watch had dropped out of school altogether. Nine-year-old Zachary said, “When I did not return to school, the teacher called my mother for a meeting but she did not go.”[91] A community worker observed that Zachary’s mother was not taking good care of him.[92]

Head teachers, teachers, and government officials told Human Rights Watch that school attendance is affected by child labor in mining, and complained about absenteeism and pupils dropping out of school altogether.[93] One head teacher said that, “When they [the children] earn money, they think there is a shortcut, school is not necessary.”[94]

A district assembly member in Amansie West district, Ashanti Region, estimated that 40 percent of children in his area were working in artisanal and small-scale mining, and that these children either attended school irregularly or not at all. He said, “The main reason for low school attendance is galamsey. Children prefer galamsey to school.”[95] Teachers in the district observed that more children were present in school on Tuesdays, when the mines were closed for work.[96]

The head teacher of a junior high school in Obuasi said that many children in the first year of junior high school (form 1) worked in mining. On the day of the Human Rights Watch visit, 26 of 44 pupils in form 1 were present. The head teacher said, “The rest is engaged in galamsey.” [97]

Children attend school more regularly in the last year of junior high school (form 3) because they are close to the graduate exam. According to one head teacher, child labor in mining was more common previously and is less of a problem now. This was confirmed by the interviews with several children who said they had recently stopped going mining, following the 2013 government crackdown on unlicensed mines.[98]

At the same time, child labor in mining sometimes enables otherwise impoverished families to pay school-related costs. Parents and other guardians often consider it the child’s duty to provide for their own school-related costs and their own food at school.

Felix, who attends form 1 and lives with his grandmother, explained that he needed to work “to come to school” and that he used the money to feed himself, buy books, and pay for printing fees.[99] Albert, 14, who lived with his aunt and uncle, said he worked to pay for school fees, books, and for his food. [100] This was the case even for children in public primary and junior high school, where no official fees are officially required, but there are informal costs. Secondary school and private schools charge tuition fees, for which children also sometimes work. Human Rights Watch interviewed one girl who was seeking to earn 800 cedis ($250) for secondary school admission, and learned of one younger boy raising his fees for a private Christian school.[101]

Attitude of Mine Managers, Sponsors, and Traders to Child Labor

Many mine owners, mine managers, machine owners, and traders said that work by younger children during the school day is unacceptable. At the same time, they had no objection to mine work by adolescents and by children outside school hours. For example, a trader and machine owner in Obuasi told Human Rights Watch:

We don’t allow children to work during school…. In my own sites, we say it is okay for children to work there on the weekend and during vacation, but not on a school day. We create jobs they can do. Some people have a vision and want to go to school and parents don’t support them, so then we agree for them to work.[102]

Similarly, another machine owner and trader said that he allows children to work during vacation.[103] A businessman with several mining sites explained that he does not allow children of school age to work at his sites, but also acknowledged that “the lines are blurred” for teenagers aged 16 and 17.[104]

Some businessmen have taken action to ensure children do not work in mining. Representatives of the National Association of Miners stated that they had taken action against child labor in licensed sites, and felt that “80 to 90 percent of the work on child labor has been done” in licensed sites.[105] Human Rights Watch did not visit licensed small-scale mines, where child labor is rare, according to NGOs working on artisanal mining issues.

Human Rights Watch also spoke to several children who related incidents in which children were sent away from mining sites. Paul, 12, said that he was initially allowed to work but the mine manager refused to have him back after he got injured while working.[106] Felix, 16, described how he and his friends were barred by adult miners from entering a mining site after the government crackdown on mining.[107] And a trader and owner of several mining sites reported that some processing sites had been closed by the head of a stone millers’ association because they employed children.[108]

III. Child Labor and the Gold Supply Chain: The Responsibility of Companies

Responsibility of Companies in the Gold Supply Chain

While governments are obligated under international law to promote and ensure respect for human rights, companies also have important human rights responsibilities. These responsibilities have been spelled out in the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (the UN Guiding Principles), an international standard adopted by the UN Human Rights Council in 2011.

Under the UN Guiding Principles, companies should put in place human rights due diligence—that is, a process to identify, prevent, mitigate, and account for companies’ impacts on human rights.[109] Companies should also monitor their impact on an ongoing basis and have processes in place to remediate adverse human rights impacts they cause or to which they contribute.[110] The guidelines recognize that small and medium-sized enterprises may have less capacity than larger companies, and that their respective policies and processes will take on different forms. Still, the responsibility of business enterprises to respect human rights applies to all enterprises regardless of their size, sector, operational context, ownership, and structure.

In addition to the UN Guiding Principles, several standards have been developed for the precious metals industry. These efforts have focused on the trade in “conflict minerals” that has often fuelled atrocities in armed conflict situations. Less effort has been made to spell out the due diligence measures that companies should take when sourcing precious metals from non-conflict areas.

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has adopted a “Due diligence guidance for responsible supply chains of minerals from conflict-affected and high-risk areas” for the gold supply chain and other minerals, which explicitly seeks to avoid contributing to the worst forms of child labor.[111] The OECD’s due diligence guidance lays out five steps for risk-based due diligence: 1) strong management systems; 2) identification and assessment of risks in the supply chain; 3) a strategy to respond to identified risks; 4) third-party audit of supply chain due diligence; and 5) public reporting on supply chain due diligence.[112] But while the OECD guidance is focused on due diligence for gold from conflict areas, it provides important guidance on how to establish human rights due diligence more broadly.

Several industry associations have also created gold-specific voluntary standards on responsible sourcing.[113] One of them is the “Responsible Gold Guidance” for refiners by the London Bullion Market Association (LBMA).[114] The standard is particularly important for gold refiners, who are only placed on the LBMA’s reputed “good delivery list” if they comply with it. The LBMA’s standard adopts the five-step approach of the OECD but is not limited to conflict-affected and high-risk countries.

In practice, the UN Guiding Principles and the industry-specific standards are not yet fully implemented. In its research, Human Rights Watch identified a number of risks in the supply chain from Ghana’s artisanal gold mines, which mean that companies sourcing from Ghana risk benefiting from child labor.

From Ghana’s Mines to the Global Gold Market

Artisanal and small-scale mines are an important economic sector and contribute significantly to Ghana’s gold exports. According to government data, 40.7 tons of gold from artisanal and small-scale mines were exported in 2013, at a trade value of more than US$1.7 billion.[115] The main export destinations for gold from artisanal and small-scale mining are Switzerland and the UAE; other export destinations are South Africa, India, China, Turkey, Lebanon, and the United States.[116] Traders buy gold at or near Ghana’s artisanal and small-scale mines, and then sell it to other parties. Most of the gold is eventually exported to international gold trading or refining companies.

The global trade in gold from artisanal and small-scale mining can be compared to a funnel: Gold from many different locations, bought by many traders, gets traded to fewer and fewer companies, until it reaches the refinery. The refiners hold a key position. One analysis even found that most of the world’s gold is refined by just six companies.[117] While the number of important refiners is higher, it is widely recognized that the refiners occupy a “choke point” of the gold supply chain.[118] After refining, the gold gets traded to numerous destinations.

The supply chain for gold for artisanal and small-scale mining operations tends to be long: The gold goes through several traders before it reaches a refinery.[119] Once the gold from these different origins has reached the refinery, it gets mixed, refined, and sold on to banks, jewelry businesses, the electronics industry or other businesses.[120]

An example of a supply chain for gold from an artisanal or small-scale mine in Ghana may look like the model below:

Traders at the bottom of the supply chain are often highly dependent on their clients—those whom they sell the gold to—because they rely on pre-financing.[121] For example, the traders who buy gold directly at the mining site usually work for larger traders in the nearest town and have been advanced cash by them. Gold traders sometimes also provide machines or other operational costs to mining operators—they “sponsor” them. That way, they oblige the miners to sell them the mined gold. These relationships are built on trust and are of a long-term nature. Since many mining operators have difficulty in getting bank loans, financial support from traders or machine owners is vital, but also creates dependency.[122]

Traders buy at the mines below the gold world market price in order to make a profit. A study on the gold trade in the Tarkwa area found that traders paid between 3.3 and 5.2 percent under the world market price.[123] A trader in Obuasi told Human Rights Watch that he paid between 2 and 5 percent below the world market price.[124]

Traders in Ghana are required to obtain a trading license from the Precious Metals Marketing Company (PMMC), the government-owned trading company and licensing authority.[125] They can obtain a license as an individual agent or as a trading company. Export licenses have to be obtained separately from the Minerals Commission.[126] Ghana has about 700 licensed agents and trading companies.[127] Seventeen companies are listed by the government as small-scale exporters.[128] The PMMC trades and exports gold too. It also exports gold for smaller traders against a fee of 0.5 percent of the world gold price.[129]

Due Diligence by Traders in Ghana

Human Rights Watch found that traders were sourcing from unlicensed mines, where child labor is common. Traders at or near the mine generally appeared to have little information on the concept of human rights due diligence; those interviewed said that they did not attempt to find out about labor conditions, the legality of the mine, or other aspects of the mining process.

Ghanaian export companies were aware of the need to conduct due diligence and described varying strategies to avoid benefiting from child labor, including sourcing predominantly from licensed mines. While these strategies helped reduce the risk of benefiting from child labor, they may not have been sufficient to guarantee a child-labor free supply chain.

Gold Traders at the Start of the Supply Chain

Human Rights Watch interviewed 16 traders at mining sites and in mining towns. All traders interviewed said that they did not attempt to find out about labor conditions, the legality of the mine, or other aspects of the mining process. As one trader put it, “All I need to know is the gold is coming and that it is real gold.”[130]

Several traders said that they were buying from unlicensed, illegal sites. Two traders stated explicitly that they were buying from licensed and unlicensed sites.[131] One other trader said that “you don’t ask the question” whether the gold is from a legal or illegal mine.[132] Managers of one unlicensed site confirmed that traders were coming regularly to the site buy gold.[133]

Asked about due diligence for child labor, a local trader who visits mining sites said that the use of child labor would make “no difference” in his decision to buy the gold.[134] A trader who has a trading company in Tarkwa said, “The only thing you ask from a person is that the gold is truly gold…. You don’t ask about labor conditions.”[135]

A trader in Dunkwa-on-Offin expressed doubt that due diligence for child labor is possible because “if I ask people where they got their gold, they will not sell to me.”[136] He felt that this was particularly true after the government crackdown on illegal mining.

Several child laborers described even how they sold gold directly to traders.[137] Kwame, 12, explained: “I sell the gold to a buyer, his name is [name withheld], and he lives in Homase. [I sell to him] at his house. He does not ask about my age.[138]

Another boy from Homase also said that he sold to the same trader, though the trader denied this in front of Human Rights Watch.[139] A notable exception was one trader who told Human Rights Watch that he had refused to buy gold from children because “it is not their time to work.” However, he also acknowledged that when adults sell gold, he does not ask where it is from.[140]

Ghanaian Gold Exporters

Human Rights Watch interviewed managers of the four largest Ghanaian companies that export gold originating from artisanal and small-scale mines: AA Minerals, Asanska, Asap Vasa, and Guldrest.[141] Human Rights Watch also contacted the companies in writing, and received responses from AA Minerals and Asanska.

Overall, representatives of these companies expressed in the meetings and in their letters that they were fully aware of the need to conduct due diligence, unlike the smaller traders in the mining areas. They stated in meetings and in letters to Human Rights Watch that they had varying strategies in place to ensure that they did not benefit from child labor. In Human Rights Watch’s assessment, these strategies may have helped to reduce the risk of benefiting from child labor to varying degrees, but may not have been sufficient to guarantee a child-labor-free supply chain.

All four companies stated that they were buying gold from licensed mines, which are not allowed to rely on child labor. In order to check that the licensed mines respected the legal prohibition on child labor, the companies said that they visited mines to check on child labor and other issues of concern. The companies also explained that they had staff present in mining towns, thus making it easier to visit and control mining sites.[142]One of the exporters, Asap Vasa, specified that they conducted unannounced site visits, and that they had never found a case of child labor.[143] Visits by the exporters involved various issues beyond inspecting child labor and did not always occur regularly.[144]

Another strategy cited by companies as a way of keeping control over the supply chain was to provide mines with machines, for example, for pumping water out of pits and for grinding ore.[145] According to AA Minerals, this strategy makes it “easier to monitor them and make sure they adhere to human rights especially child labor and labor rights.”[146]

Companies had somewhat different approaches to intermediary traders. The representative of Asap Vasa stated it is the company’s strategy to buy only directly from registered (licensed) mines, and not from licensed traders, “because we are not able to track the source of the gold.”[147] The representative of Asanska explicitly stated “we don’t have intermediaries.”[148] However, he also acknowledged that his company sometimes buys small amounts of gold from people who come to their buying centers and who are not part of their regular network.[149] Similarly, AA Minerals stated that “our company is able to trace 90 percent back to the mines,” implying that the remaining 10 percent may be purchased from intermediary traders and cannot be traced back.[150] Guldrest stated that their strategy includes buying from licensed traders. Its director said: “You don't buy gold from anybody.… I only buy from miners with a license and buyers with buyer’s license.”[151] However, he also acknowledged that licensed traders buy from unlicensed and unregulated sites. “You are in the bush where you can do what you want,” he said.[152]

As illustrated above, licensed traders often buy without distinction from licensed and unlicensed sites. Thus, buying from licensed traders introduces a risk of child labor in the supply chain, unless a company makes the effort to control the trader’s supply chain.

With regards to environmental concerns and specifically the use of mercury, exporters explained that they had informed miners about environmental concerns and recommended specific mercury-free gold processing methods to them.[153] One company said that it was providing a machine for mercury-free processing (gravitation method) to miners.[154] Still, gold processing with mercury remains the most common method used in Ghana, and is also being used by some of the mines where larger exporters buy their gold.

Child Labor Due Diligence by the PMMC and Minerals Commission

The PMMC exports gold primarily to Switzerland, where one of its important (at least former) clients is the refiner Metalor.[155] It also exports to the UAE and to India. The PMMC exported a little over one ton in 2012 and 2013 each, a small amount compared to total exports in the sector. Since 2009, its exports have decreased by about 50 percent, and larger individual companies have taken over the market.[156]

The PMMC does not appear to have a human rights due diligence procedure for gold. In order to obtain a license as an individual buying agent, a trader has to be over the age of 18 and show proof of identity. In order to get a license as a company, a trader also has to provide a letter from the company.[157] No further checks are undertaken to verify the origin of the gold the trader sells or the working conditions at the sites. There is also no requirement to only buy at legal (licensed) sites. According to the director of the PMMC, “We know that some of our agents buy from unlicensed sites.”[158] As a result, the PMMC effectively legalizes the gold from illegal mining sites. An official of the Minerals Commission confirmed this approach: “When you come to PMMC, nobody questions you where you got the gold from.”[159]

For diamonds, the PMMC requires a due diligence report from buying companies before licensing them.[160] The director of the PMMC pointed out the difference between supply chains in the diamond and gold sector: “[With gold], we have no way of knowing…. You cannot know whether the gold is from child labor.”[161]

Companies obtaining an export license from the Minerals Commission are also not required to have human rights due diligence procedures in place, though they have to document their gold purchases with receipts.[162]

Due Diligence by Global Gold Refiners

Gold refiners are at a crucial point of the gold supply chain and have a key role to play in developing and implementing due diligence policies and procedures. Human Rights Watch analyzed due diligence policies procedures of the six international refiners sourcing gold from Ghana’s artisanal mines: Metalor (Switzerland), Produits Artistiques Métaux Précieux (PAMP) (Switzerland), Kaloti (UAE), Emirates Gold (UAE), Kundan (India), and Randgold Refinery (South Africa). Human Rights Watch focused on these refiners because its research found that they were sourcing from Ghana. However, there may be other refiners sourcing from Ghana who are not mentioned in this report.

In addition to interviewing the companies and traders in Ghana, Human Rights Watch sent letters to the nine international refiners to inform them about its research findings on child labor, and to ask them about the measures they had in place to ensure they were not benefiting from child labor.

Four—PAMP (Switzerland), Metalor (Switzerland), Kaloti Jewellery International (UAE), and Rand Refinery (South Africa)—responded and acknowledged sourcing gold from Ghana. Another two refiners—Kundan Gold and Emirates Gold—did not respond formally, even though Human Rights Watch has information about them sourcing from Ghana. Finally, another three refiners—Valcambi (Switzerland), Argor-Heraeus (Switzerland), and Heräus (Germany)—responded saying that they did not source from Ghana. Their due diligence measures are not analyzed in detail in this report.[163]

Human Rights Watch found that five of the six refiners sourcing from Ghana had policies on human rights due diligence or responsible sourcing in place and available online, and were conducting significant due diligence steps. [164] However, lack of detail in the refiner’s responses, and the refiners’ unwillingness to make public information on how they have identified and addressed risks found in their supply chains, make it difficult to assess the effectiveness of their actions.[165] Based on the available documentation, Human Rights Watch found that several of these companies had weaknesses in their due diligence procedures, such as a lack of systematic child labor monitoring or a lack of transparency.

Due Diligence by Gold Refiners in Switzerland

Switzerland has historically been the world’s center for the gold trade and refining, and remains a very important player today. According to analysts, six companies refine 90 percent of the world’s gold, and four of these are located in Switzerland.[166]

The lack of transparency of the gold trade—closely connected to the banking sector—has been a topic of public debate in Switzerland, and NGOs have called for the creation of a Swiss commodity market supervisory authority that requires human rights due diligence.[167] Swiss refiners are already obliged by law to conduct due diligence in relation to terrorism and money-laundering, but there are no specific requirements regarding human rights violations, including child labor.[168]

Metalor

Metalor is one of the world’s leading refiners—its refining capacity is estimated at 650 tons per year—which supplies jewelry, watch, and electronics companies, as well as banks.[169] Four Ghanaian exporters—Asap Vasa, Asanska, Guldrest, and AA Minerals—as well as the government-owned PMMC told Human Rights Watch that they exported to Metalor.[170] This would make Metalor one of the most important single business partners for Ghana’s trade in artisanal mined gold. It is to be noted that Metalor contests having such a position, as most of the abovementioned exporters are currently not supplying Metalor.[171] However, it is not possible to verify this assertion since Metalor does not reveal from which of those exporters it is not or no longer buying gold.

Metalor’s Supply Chain Due Diligence Policy states explicitly that the company will not tolerate or profit from human rights abuse, including the worst forms of child labor.[172] In a letter to Human Rights Watch, Metalor explained its due diligence procedures further. The company undertakes “regular analysis and verification of the bona fide of each customer,” a “detailed due diligence review, including of the supply chain,” and onsite inspections. The company also said that they conduct investigations in case there are doubts over the supply chain.[173]

While these are important due diligence measures, Metalor’s response to Human Rights Watch reveals potential risks in its supply chain from Ghana. Metalor stated that its business partners are licensed by the government to buy and export gold, and that “those buying from other producers can only buy from duly licensed small-scale mining operation[s].”[174] Metalor emphasized that the government itself vouches for exporters, saying they do not source gold from illegal mines or mines that use child labor.[175]

However, as shown above, licensed traders have bought gold from unlicensed sites, where child labor occurs and is sometimes common. The government is aware of the sale of gold from unlicensed mines to licensed traders and does not prevent it. Furthermore, licensed sites may not be inspected regularly for child labor by government officials.

In its letter, Metalor indirectly acknowledged these risks when saying that it “believes and is continuously striving to ensure that the mines Metalor is sourcing from in Ghana do not use child labor,” implying that there may be child labor. The company also stated that it did not take on new suppliers in Ghana over the last year because of its demanding criteria. With regards to mercury, Metalor says it requires that suppliers provide “mercury-free” gold.[176] In addition, Metalor asserts that it scans the gold with an X-ray system and that it sends back gold to its suppliers if mercury has been detected.[177]

Despite these supply chain risks, Metalor has been audited against several responsible mining standards, and found to be in compliance. For example, Metalor has received a Responsible Gold Certificate from the London Bullion Market Association (LBMA), the London-based global gold trading association, confirming that it is in compliance with the LBMA Responsible Gold Guidance.[178] Metalor has also been certified by the Responsible Jewelry Council (RJC), a body that brings together over 500 companies, for its compliance with the RJC Chain-of-Custody Standard.[179] The certification means that the gold has been “responsibly produced at each step of the supply chain” and is conflict-free.[180] The decision-making processes by LBMA and RJC remain somewhat unclear, as only the LBMA certificate (and not the report) is publicly accessible and the RJC has only published a summary report, respectively.

Produits Artistiques Métaux Précieux (PAMP)

PAMP, another Swiss refiner, has an estimated refining capacity of 450 tons per year.[181] It is a member of the MKS Group, which trades in precious metals. The company informed Human Rights Watch in a letter that it is buys gold from one supplier in Ghana.[182]

MKS has a Responsible Precious Metals Group Policy for PAMP and other subsidiaries. The policy states that the MKS group will not tolerate or profit from “illegal and/or unacceptable forms of child labor.”[183] In its letter to Human Rights Watch, the company stated that it assesses various risks, including the risk of child labor and other human rights abuses, for each new supply chain. PAMP’s due diligence process includes verification of the customer and his licenses, identification of the ultimate beneficial owner, determining the origin of precious metals, understanding the mining process and social responsibility measures taken—including measures to prevent child labor—and onsite visits.[184]

In Ghana, the company sources from one licensed exporter, who in turn sources from 12 licensed mines.[185] PAMP has provided detailed information on the mines where its gold is being produced to Human Rights Watch, including location, number of workers, and gold processing methods.[186] In March 2015, PAMP visited the mines that its supplier sources from, and said it observed no child labor on any site.[187] In PAMP’s own assessment, there is no evidence of the use of child labor at these mine sites. This detailed information makes the company’s procedure more robust.

In order to seek additional assurances over its supply chain, PAMP has sought an attestation from the government Minerals Commission that its gold was sourced from these 12 sites, and not from illegal sources or operations involving child labor.[188] During its March 2015 visit, PAMP was assured by the Minerals Commission that they perform regular unannounced visits and know each mine site well.[189] While regular unannounced visits are a crucial element of monitoring, Human Rights Watch cannot judge the validity of these government attestations.

PAMP has been certified to be in compliance with the LBMA’s Responsible Gold Guidance. The compliance report and auditor’s summary report are available on their website.[190] The company should make more information on its robust due diligence procedures public: such transparency is part of good due diligence activity and could serve as illustration of what is possible, as well as allow for independent scrutiny.

Due Diligence by Gold Traders and Refiners in the UAE (Dubai)

Over the past few years, the UAE, and Dubai in particular, has emerged as a global hub for the gold trade. In 2013, about 2,200 tons of gold or nearly 40 percent of the global gold trade flowed through Dubai, according to the government regulator, the Dubai Multi Commodities Centre (DMCC).[191] The rise of Dubai as the “City of Gold” has been closely connected to the expansion of the Asian gold market.[192]

Dubai is known as a business-friendly location; it has tax-free zones and regulatory controls on gold imports. Dubai companies have been found to be involved in the illicit gold trade from war-torn Democratic Republic of Congo, and in practices that increase the risk of money-laundering, such as cash transactions.[193] In 2012 the DMCC introduced guidance for a responsible supply chain that is mandatory for Dubai’s main refiners in the free trade zone.[194] The guidance seeks to eliminate the risk of supporting armed conflict through trade; it does not mention child labor but obliges refiners to put in place due diligence procedures that could also be used to assess child labor risks in the supply chain. Other companies in the UAE, such as gold traders based in Dubai’s souk (gold market), are not covered by the DMCC rules. As a result, there is a risk that jewelers in the souk buy gold whose origin is unclear and could be problematic, and then sell it on to the large refiners.[195]

Several Ghanaian traders and the PMMC told Human Rights Watch that they were exporting gold to Dubai. Local traders who were not exporting themselves also mentioned Dubai as one of the main export destinations.[196]

Kaloti

Kaloti is one of the largest Dubai-based refiners. According to the company website, Kaloti currently refines around 300 tons of gold per year and is building a new refinery in Dubai that is designed to refine 1,400 tons per year, exceeding the refining capacity of its Swiss and South African competitors.[197] Two exporters in Ghana, Guldrest and AA Minerals, specifically stated that they exported gold to Kaloti, and Kaloti confirmed in its letter to Human Rights Watch that it is sourcing from Ghana.

According to Kaloti’s policy and procedures, the company has agreements in place with its suppliers to follow policies on responsible sourcing from conflict-affected and high-risk areas, to avoid contributing to conflict. However, the policy is weak on other human rights issues, including child labor. It stipulates that Kaloti “will comply with all relevant UN resolutions combating any and all forms of inhuman treatment, forced child labor & sexual violence.”[198] It lacks any mention of measures to address these abuses in the supply chain—indeed, existing UN resolutions contain no firm obligations with regards to a company’s supply chain.[199] The policy is also limited to forced labor and does not mention child labor generally, or its worst forms. Despite these weaknesses in Kaloti’s policy documents, the company requires suppliers to confirm in writing that the traded gold is “free from child labor,” conflict-free, and legally produced to their best of their knowledge.[200]

In a letter to Human Rights Watch, Kaloti stated that the company only buys from licensed suppliers in Ghana.[201] However, as illustrated above, licensed traders sometimes buy gold from unlicensed mines where child labor is common—and therefore, buying from licensed suppliers carries a significant risk of buying gold mined with child labor. Hence, Kaloti’s supply chain may still have some risks with regards to child labor.

Kaloti implied that it addresses this risk by “tracing the origin of the gold back to the mine in all cases.” The company also conducts site visits. According to Kaloti’s letter, during such visits, the company identifies all actors in the supply chain and “signs of child labor in the workforce,” and checks compliance with environmental and mining regulations.[202] However, Kaloti did not respond to Human Rights Watch’s questions on the origin of the gold and its chain of custody and did not provide details on how it conducts child labor monitoring.

The last visit by Kaloti occurred in June 2014 and included meetings with government officials who assured the company “of their procedures and monitoring activities to eliminate child labor in the Ghanaian mines.” It remains unclear what specific procedures and activities the government was referring to; Human Rights Watch has found the child labor monitoring regime to be flawed.[203] Yet, Kaloti took the government’s statement as assurance that it has “eliminated any risk pertaining to child labor.”[204]

Emirates Gold

Emirates Gold is another leading refiner from Dubai, with a refinery volume of about 200 tons per year.[205] One exporter from Ghana, Guldrest, informed Human Rights Watch his company is selling gold to Emirates Gold.[206] Emirates Gold declined to respond formally on the record to Human Rights Watch’s letter, but Human Rights Watch has had unofficial exchanges with Emirates Gold.

Emirates Gold’s Compliance, Anti-Money Laundering and Supply Chain Management policy is modeled on the OECD’s guidance, but does not limit itself to conflict-affected or high-risk areas. It specifically states that the company will not tolerate or profit from human rights abuse, including the worst forms of child labor.[207]

Emirates Gold has been audited against the DMCC guidance on responsible sourcing, and found to be compliant. Its compliance report and the auditor’s assurance report are available on the company website.[208] The company has also been certified to be compliant with the LBMA Responsible Gold Guidance. The compliance report and auditor’s summary report are available on their website.[209] The company’s policy and these reports indicate that Emirates Gold follows the due diligence model of the OECD, but they contain little specific information on the due diligence procedures used by Emirates Gold. For example, it is not clear from the available documentation whether the refiner is able to trace back the gold it receives to its mine of origin and what is specifically being done to avoid purchasing gold that has been mined with child labor.

Other Gold Refiners

Exporters also informed Human Rights Watch that they were exporting gold from artisanal mines to Rand Refinery in South Africa,[210] Kundan Group in India,[211] and Turkish refiners.[212]

Kundan

Kundan is an Indian refinery with a refining capacity of 200 kilograms per day.[213] There is no policy on responsible sourcing or compliance policy available on its website, and it is not clear whether the company has such a policy. There are also no summary audit reports or other reports about the company’s due diligence measures available online. Kundan did not respond to Human Rights Watch’s letter.[214] It is therefore impossible to assess the company’s due diligence procedures. Regardless of the quality of Kundan’s due diligence measures, the lack of public reporting is of concern.

Rand Refinery

Rand Refinery, a South African refiner, describes itself as one of the world’s largest gold refineries.[215] According to analysts, the refinery has a capacity of about 600 tons per year.[216]

The company’s responsible gold policy mirrors the OECD due diligence guidance, including its focus on conflict-affected and high-risk areas. With regards to these areas, it explicitly mentions that it will not tolerate or assist any use of child labor.[217] Rand Refinery has been certified by the LBMA and has made a summary compliance report public on its website.[218]

The report states that Rand Refinery has a chain of custody process that ensures full traceability, a monitoring system, and a whistleblowing mechanism to report concerns.

Rand Refinery sourced periodically from a Ghanaian export company until August 2014, but does not do so anymore.[219]

IV. Ghanaian Government Response