Not Safe at Home

Violence and Discrimination against LGBT people in Jamaica

Glossary

Bisexual: Sexual orientation of a person who is sexually and romantically attracted to both women and men.

Butch: Masculine gender expression; a popular term within lesbian and transgender communities to describe lesbians whose gender expression is masculine.

Gay: Synonym for homosexual in many parts of the world; in this report, used primarily to refer to the sexual orientation of a man whose primary sexual and romantic attraction is towards other men.

Gender Expression: External characteristics and behaviors that societies define as “feminine,” “androgynous,” or “masculine,” including such attributes as dress, appearance, mannerisms, hair style, speech patterns, and social behavior and interactions.

Gender Identity: Person’s internal, deeply felt sense of being male, female, both, or something other than male or female.

Heterosexual: Sexual orientation of a person whose primary sexual and romantic attraction is toward people of the other sex.

Homosexual: Sexual orientation of a person whose primary sexual and romantic attractions are toward people of the same sex.

Homophobia: Fear and contempt of homosexuals, usually based on negative stereotypes of homosexuality.

Lesbian: Sexual orientation of a woman whose primary sexual and romantic attraction is toward other women.

LGBT: Lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender; an inclusive term for groups and identities sometimes also associated together as "sexual and gender minorities."

Men Who Have Sex with Men (MSM): Men who engage in sexual behavior with other men, but do not necessarily identify as "gay," “homosexual,” or "bisexual."

Out/To be Outed: To be in a position where one’s sexual orientation is openly known and acknowledged, to have one’s sexual orientation revealed (perhaps inadvertently) through words or actions, or to be exposed as homosexual or bisexual by another person without one’s consent.

Sexual Orientation: The way a person’s sexual and romantic desires are directed. The term describes whether a person is attracted primarily to people of the same or opposite sex, or to both.

Transgender: Adjective used to describe the gender identity of people whose assigned gender (the gender they were declared to have upon birth) does not conform to their lived and/or perceived gender (the gender that they are most comfortable with expressing or would express, if given a choice). A transgender person usually adopts or would prefer to adopt a gender expression in consonance with their preferred gender, but may or may not desire to permanently alter their bodily characteristics to conform to their preferred gender.

Transphobia: Fear and contempt of transgender people, usually based on negative stereotypes about transgender people.

Women Who Have Sex with Women (WSW): Women who engage in sexual behavior with other women, but do not necessarily identify as “gay,” “homosexual,” “lesbian,” or “bisexual.”

Note on Jamaican Language

Many Jamaicans speak “patois” or Jamaican Creole in addition to Caribbean Standard English. The following patois words and phrases appear in this report:

Battyman/Battybwoy: “Batty” is a slang term for “buttocks.” Battyman or Battybwoy is a pejorative term for men who have sex with men, as anal sex is seen as the act that defines them.

“Battyman fi dead”: Gay men should be dead/killed; gay men must die.

Fish: Effeminate man who has sex with men.

Sodomite / Sodomite gal: Derogatory term for a woman who has sex with women.

Summary

On July 21, 2013, 16-year-old Dwayne Jones attended a dance party in Montego Bay, Jamaica, dressed in women’s clothing. When partygoers at the bar in Irwin, St. James, realized she was biologically male, they subjected her to almost every form of physical violence imaginable—beating, stabbing, and shooting her before running her over with a car. No one helped her during the assault. When police arrived, they found her body dumped in bushes along the main road. Dwayne had been homeless since age 12, rejected by her family because of her gender identity. Her family initially refused to claim her corpse from the morgue.

Dwayne’s murder received national, regional, and international media attention, and served as a catalyst for public debate. Justice Minister Mark Golding condemned the brutal murder, calling on the police to “spare no effort in bringing the perpetrators to justice.” A small public protest against the killing took place in Kingston’s Emancipation Park. The police interviewed witnesses and provided information about the murder investigations to Jamaica’s preeminent lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights organization, J-FLAG. At time of writing, however, no one had been arrested or charged.

***

The story of Dwayne Jones lies at one extreme end of a continuum of violence experienced by Jamaicans who identify as lesbian, gay, transgender, or bisexual. Nevertheless, the circumstances of her murder provide a snapshot of the current situation facing many LGBT people in Jamaica: a high risk of violence, vulnerability heightened by poverty and family rejection, and mixed responses from both the authorities and the public.

This report builds on previous research published by Human Rights Watch in 2004, Hated to Death: Homophobia, Violence and Jamaica’s HIV/AIDS Epidemic. Documenting human rights violations carried out against LGBT persons in Jamaica between 2006 and 2013, it focuses on the intolerable level of violence, physical and sexual, perpetrated based on actual or perceived sexual orientation or gender identity. Second, it documents discrimination LGBT people face from government institutions, including health care facilities, as well as in the private sector. The report then turns to the state’s responsibility for this abuse, considering legislation that facilitates abuses by private and public actors (such as “buggery laws” that outlaw anal sex and all male homosexual conduct), and government efforts to protect the rights of LGBT persons, including police investigation of homophobic and transphobic violence.

High levels of violent crime, public mistrust of police, low levels of crime reporting, low prosecution rates, and a perception that the criminal justice system is skewed against the poor are widespread in Jamaican society. However, LGBT Jamaicans—especially those who are poor and unable to live in safer, more affluent areas—are particularly vulnerable to violence. Many live in constant fear. They are taunted; threatened; fired from their jobs, thrown out of their homes; beaten, stoned, raped, and even killed.

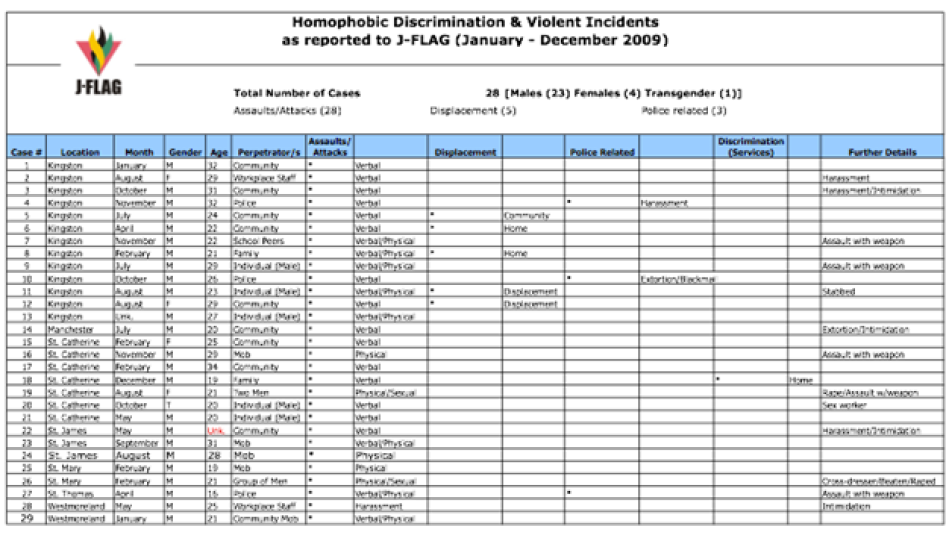

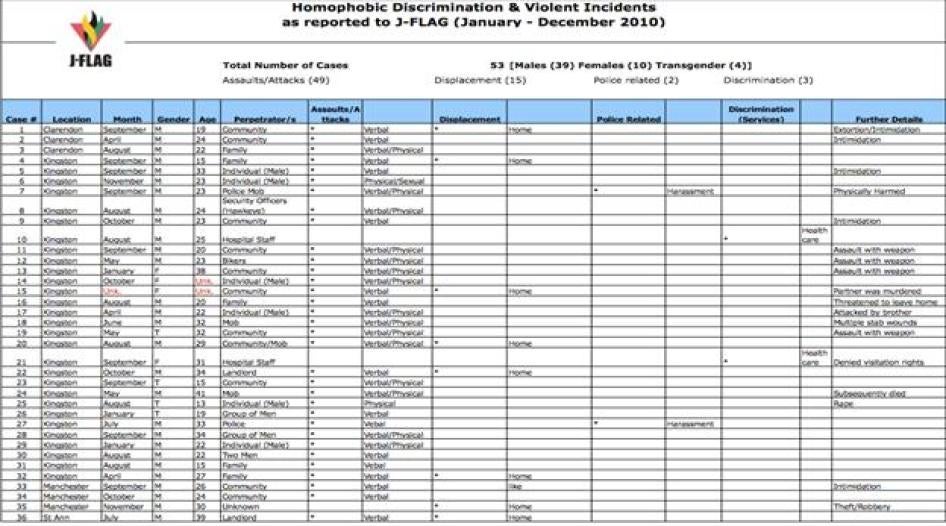

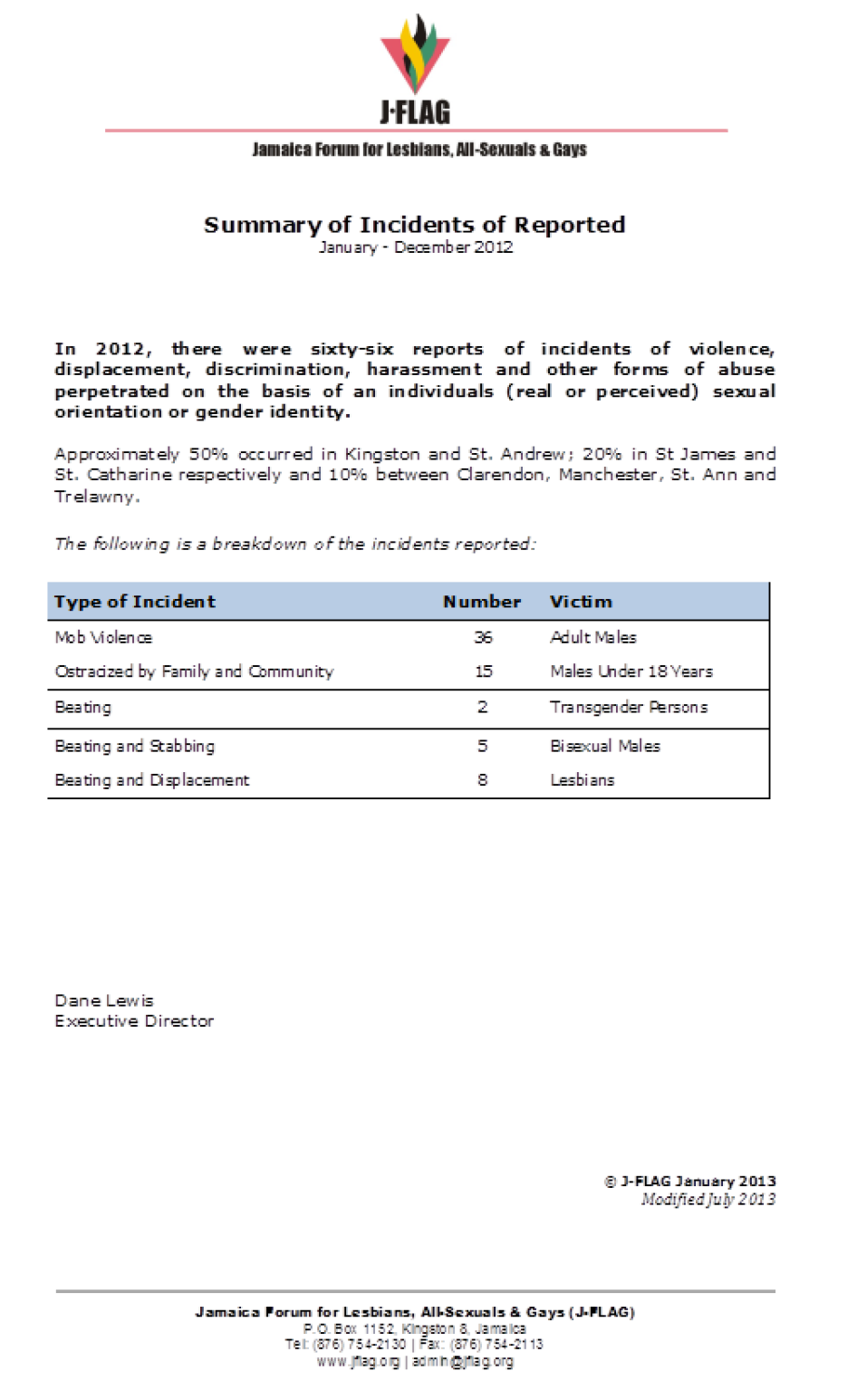

Between 2009 and 2012, J-FLAG, a Jamaican LGBT rights organization, recorded 231 incidents of attacks against LGBT people, including home invasions, physical assaults, and mob attacks.

Human Rights Watch conducted five weeks of field research in Jamaica in April and June 2013, interviewing 71 LGBT people as well as state officials and other stakeholders. Of those interviewed:

- More than half (44) said they had been victims of some form of violence based on their sexual orientation or gender identity, some more than once;

- Nineteen had reported these crimes to the police, who only took formal statements in eight cases;

- Victims were aware of arrests by police in only 4 of the 56 cases of violence that Human Rights Watch documented;

- Twenty-six of those who had experienced violence said they did not report crimes due to fear of retaliation from the perpetrators or because reporting a homophobic or transphobic hate crime would “out” them to broader society.

In recent years, the police have taken some steps to address homophobic and transphobic violence. In 2011, the Jamaican Constabulary Force launched a Policy on Diversity, developed in consultation with J-FLAG, which requires police to ensure that LGBT people and other vulnerable groups can safely file police reports. The policy establishes a mechanism to monitor police non-compliance, although Human Rights Watch has not been able to ascertain whether any police have been held accountable for non-compliance, despite a formal request for this information (see Annex I).

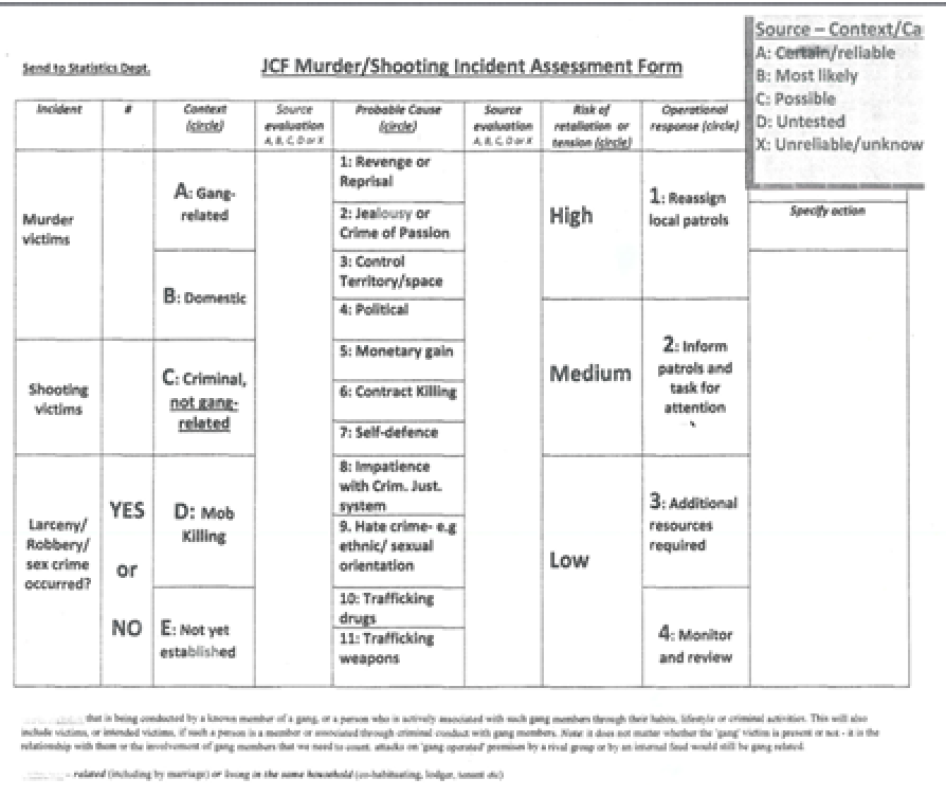

The Ministry of National Security has also developed tools to monitor experiences of crime, including the Violence Attribution Assessment Form. This specifically mentions “hate crime” as a cause of violent crime, lists “sexual orientation and gender identity” as one possible motivation for hate crime, and requires that police conduct immediate assessments to determine whether a hate crime has indeed occurred. (The definition of “hate crime” is not provided, however, potentially complicating the work of the police.)[1]

In March 2012, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights’ (IACHR) “Report on the Situation of Human Rights in Jamaica” found that discrimination based on sexual orientation, gender identity, and gender expression is widespread and entrenched in Jamaican state institutions. Following the report’s release, Justice Minister Mark Golding acknowledged the need for targeted anti-discrimination legislation to address violations against certain groups in society, although he did not specifically mention LGBT people.

Nonetheless, police protection remains inadequate, and is among several factors that contribute to the specific vulnerability of LGBT people. Families and neighbors often drive LGBT people from their homes and communities; landlords refuse to rent to LGBT persons, denying them housing; health providers stigmatize them when they seek services; and employers arbitrarily fire them.

Many LGBT Jamaicans become effectively homeless, forced to flee their homes and sometimes the country, and denied full citizenship rights. Among the most vulnerable are dozens of gay and transgender Jamaican children and young adults who have been rejected by their families and are living on the streets, where they face violence and harassment by police and the public.

The negative public discourse about LGBT people, who are referred to in the most derogatory of terms in public spaces, combined with the risk of physical violence, can have severe psychological implications. A 2007 study of LGBT Jamaicans found that they had disproportionately higher rates of mental health issues, and many interviewees said they constantly struggle with the stress associated with keeping their sexuality hidden in order to stay safe from harm. Some spoke of wanting to commit suicide.[2]

Given the risk of violence and discrimination, many LGBT people remain closeted in order to protect themselves. But in the last three years, a number of LGBT activists have come out publicly, in media or as lawyers or litigants in two major court cases challenging anti-gay discrimination. LGBT people are also increasingly reporting incidents of hate crime: in 2012 J-FLAG found that almost half of the 63 reports it received were also reported to police. J-FLAG, with funding from the Caribbean Vulnerable Communities Coalition, launched a social media campaign, “We are Jamaicans,” in which LGBT persons and allies speak out online about sexual orientation and gender identity, including their own experiences.

Despite these public and private initiatives, the Jamaican government still offers little in practical terms to prevent and protect against violence and discrimination, or to punish the perpetrators of crimes against LGBT people. Jamaica has neither comprehensive anti-discrimination legislation, nor specific legislation prohibiting discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation or gender identity. Serious rights abuses based on sexual orientation and gender identity continue, and justice for these crimes remains elusive.

International law and standards require Jamaica to prohibit discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. Jamaica’s sodomy laws violate those international standards, as do the abuses documented in this report, including police failure to address violence against LGBT people.

In December 2011, Prime Minister Portia Simpson Miller pledged that, “No one should be discriminated against because of their sexual orientation,” and at the same time called for the legislature to revisit Jamaica’s buggery laws.[3] However, on April 3, 2014, she stated in an interview that repealing the law would have to be “based on the will of the constituents,” and that repeal was not a “priority.”[4]

Meaningful progress will require a deeper commitment to equality on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity, particularly by the police. Progress will also require strong leadership from Jamaica’s government in the face of intense public resistance to any type of legal reform that would uphold the rights of LGBT people.

In order to translate words into action and ensure the equal rights of all persons regardless of their gender identity or sexual orientation:

- Prime Minister Portia Simpson Miller, parliamentarians, and other leaders should consistently condemn violence and discrimination.

- Police should undertake rigorous investigations into all allegations of anti-LGBT hate crimes, improve monitoring of the Policy on Diversity, and strengthen police training on LGBT rights, in collaboration with LGBT civil society groups.

- Parliament should strike down all discriminatory laws and replace them with laws that protect Jamaicans from discrimination on the grounds of gender identity and sexual orientation.

Key Recommendations

To the Prime Minister

- Uphold your election campaign pledge that “no one should be discriminated against because of their sexual orientation,” and translate it into concrete policy by proposing comprehensive anti-discrimination legislation that prohibits all forms of discrimination, including on the grounds of sexual orientation and gender identity, in all areas of life governed by law.

To the Ministry of National Security

- Closely monitor implementation of the Jamaica Constabulary Force (JCF) Policy on Diversity, and issue regular, public reports on its implementation.

- Strengthen monitoring and reporting mechanisms to better document incidents of hate crime against LGBT people, ensure accurate reporting and collation of information, and identify patterns of crimes.

To the Jamaican Constabulary Force

- Undertake prompt, independent, and effective investigations into all allegations of acts of violence, including those that may be motivated by sexual orientation or gender identity.

- Build a stronger working relationship with Jamaica’s leading LGBT organizations, including J-FLAG and Quality of Citizenship Jamaica. Work consistently and systematically with these organizations to develop sensitization and human rights training, and collaborate with them to identify and document incidences of violence.

To the Ministry of Justice

- Work with police, prosecutors, health care providers, and other social service agencies to develop an integrated approach or protocol to deal with LGBT people who are victims of violence.

To the Ministry of Youth and Culture, Ministry of Local Government and Community Development

- Develop an inclusive, non-discriminatory homelessness policy that explicitly commits to addressing the needs of LGBT homeless people, including children and young adults.

To Parliament

- Repeal Sections 76, 77, and 79 of the Offenses against the Person Act, which criminalize consensual adult same-sex conduct.

- Amend the Sexual Offences Act 2009 to remove the gender-specific definitions of sexual intercourse and rape.

Methodology

This report is based on information collected during five weeks of field research conducted in Jamaica in April and June 2013, as well as prior and subsequent desk-based research.

Two Human Rights Watch researchers conducted 71 interviews with self-identified lesbian, bisexual, gay, and transgender people, including 3 LGBT children (i.e., under 18 years old). These interviews took place in Kingston, Manchester, St. Ann, St. James, St. Catherine, and St. Andrew.

All persons interviewed provided verbal informed consent to participate and were assured that they could end the interview at any time or decline to answer any questions. These interviewees have been given pseudonyms and in some cases other identifying information has been withheld to protect their privacy and safety. No one was compensated for their participation.

Most interview subjects were identified with the help of Jamaican nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) that provide services to people living with HIV, men who have sex with men (MSM), women who have sex with women, transgender people, and sex workers.

Many interview subjects told Human Rights Watch they were victims of violence based on their sexual orientation and gender identity. Such accounts were often difficult to independently verify. Most victims were alone when they were attacked, and many did not file police reports, for reasons discussed in Section II. We were able to corroborate 11 out of 56 reported incidents through police receipts documenting the incidents, court proceedings, or letters and incident reports from J-FLAG. In terms of the types of physical assaults documented, the information that we garnered closely paralleled the yearly incident reports that J-FLAG collated.

Human Rights Watch also interviewed representatives of government agencies, United Nations (UN) officials, representatives of NGOs specializing in HIV/AIDS or human rights, academics, health care workers, and members of Jamaica’s police force.

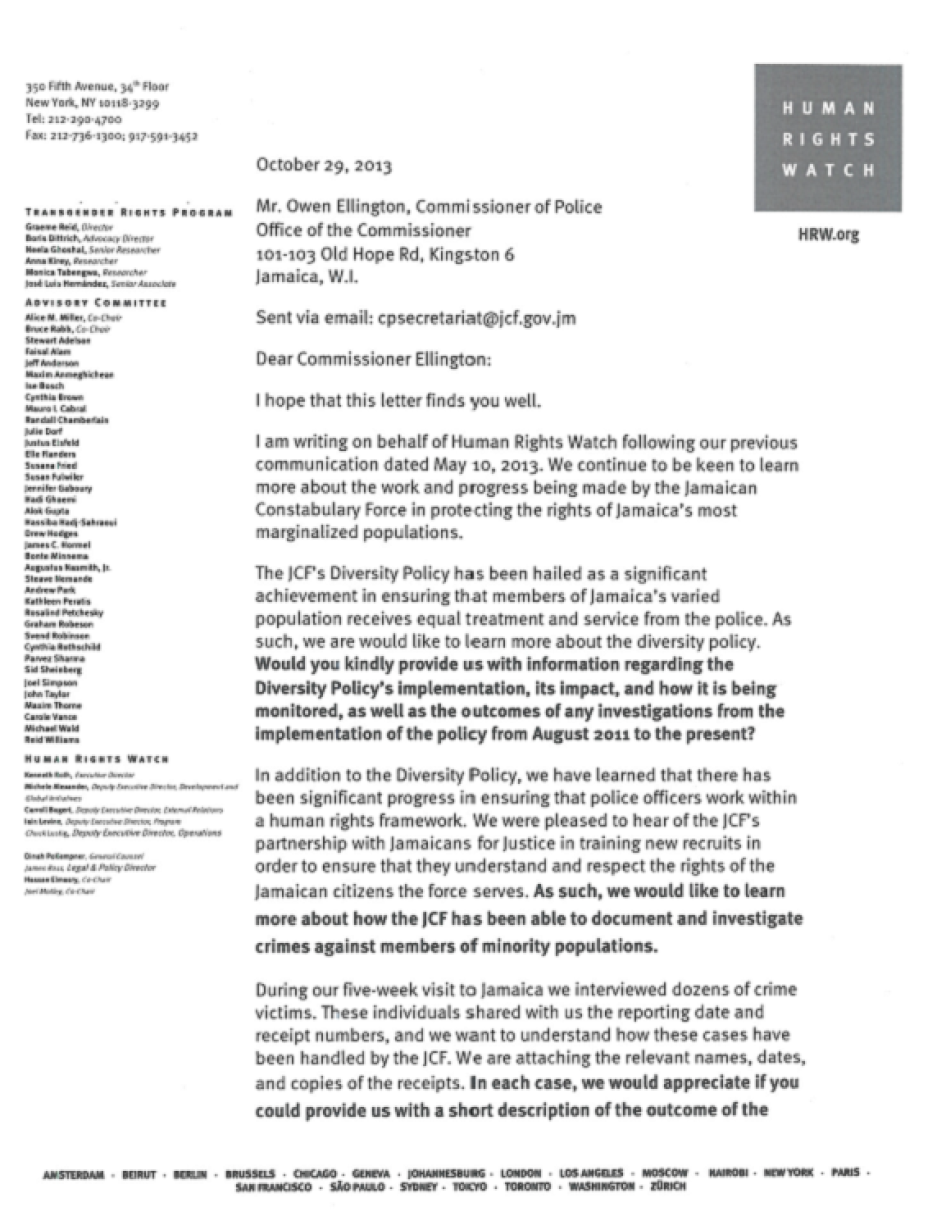

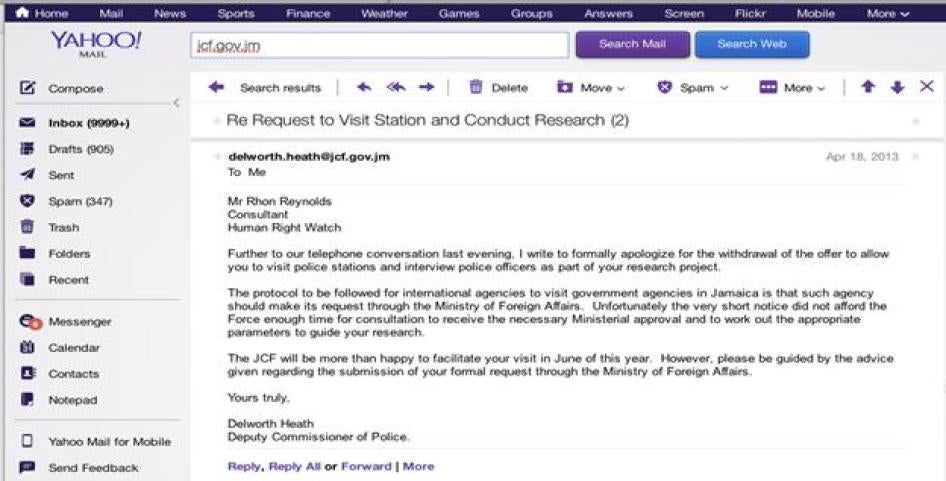

On October 30, 2013, Human Rights Watch wrote to the Commission of Police requesting information about the JCF’s Policy on Diversity and its implementation as well as its impact (see Annex I). The letter further asked for information on how the JCF monitors crimes against sexual minorities, and for information about specific cases and their outcomes. At time of writing, we had not received a response.

All documents cited in this report are publicly available or on file with Human Rights Watch.

I. Public Attitudes towards Homosexuality

Criminalization

Jamaica’s anti-sodomy or “buggery” laws that prohibit same-sex conduct between consenting adult males date to 1864 when Jamaica was a British colony. Sections 76 and 77 of the Offences Against the Person Act make "the abominable crime of buggery" punishable by “imprisonment and hard labor for a maximum of ten years,” while an “attempt” to commit buggery is punishable by seven years’ imprisonment. Section 79 prohibits "acts of gross indecency" (generally interpreted as referring to any kind of physical intimacy) between men, in public or in private. The Sexual Offences Act of 2009 requires men convicted of the “abominable crime of buggery” to register as sex offenders.[5]

Prosecutions under these laws are rarely pursued. Nevertheless the laws have a real and negative impact. Criminalizing sexual intimacy between men offers legal sanction to discrimination against sexual and gender minorities, and in a context of widespread homophobia, gives social sanction to prejudice and helps to create a context in which hostility and violence is directed against LGBT people.

The laws have been used by police to extort money from adults engaged in consensual homosexual sex; by public television stations to justify refusal to air public service announcements making positive statements about LGBT persons; and by landlords to justify refusal to rent apartments to them. Though those arrested are rarely if ever prosecuted, gay men who are “outed” through arrest risk violence and other abuse by community members.

While the law does not directly reference transgender people, transgender women and homosexuals are often conflated. Gender non-conforming Jamaicans, especially transgender women and gender non-conforming gay men who are publicly visible, are most likely to suffer violence and discrimination.

Same-sex relations between women are not criminalized in Jamaica. However, lesbians and bisexual women are stigmatized and subjected to violence, including sexual violence, as discussed in Section III.

In contrast, the Sexual Offences Act narrowly defines rape as the non-consensual penetration of a vagina by a penis, with a maximum penalty of life imprisonment.[6] Accordingly, the law does not recognize male rape, only “buggery,” with perpetrators facing a significantly lower penalty. Anal rape of females is also classified as “buggery.” The gender-biased, inadequate definition of rape in the Sexual Offences Act leaves several categories of victims of sexual violence, including male victims of rape and female victims of anal rape, unprotected by the law.

Homophobic Discourse

Anti-LGBT public rhetoric continues to be fueled by some elements of the religious, media, music, and political establishments.

Religious

Religion, particularly protestant Christianity, has strong influence in Jamaica. Politicians often describe the country as a “Christian nation” and Jamaicans as “a God-fearing people.” Some Christians combine religious rhetoric with homophobia. The Jamaican Coalition for a Healthy Society (JCHS)—an evangelical Christian network with the stated vision that a “healthy Jamaican society” is based on the Bible—has been proactive in lobbying the government to preserve Jamaica’s sodomy laws. Established in January 2012, the JCHS has risen to some public prominence in Jamaica through an aggressive media campaign, public protests, and rallies.

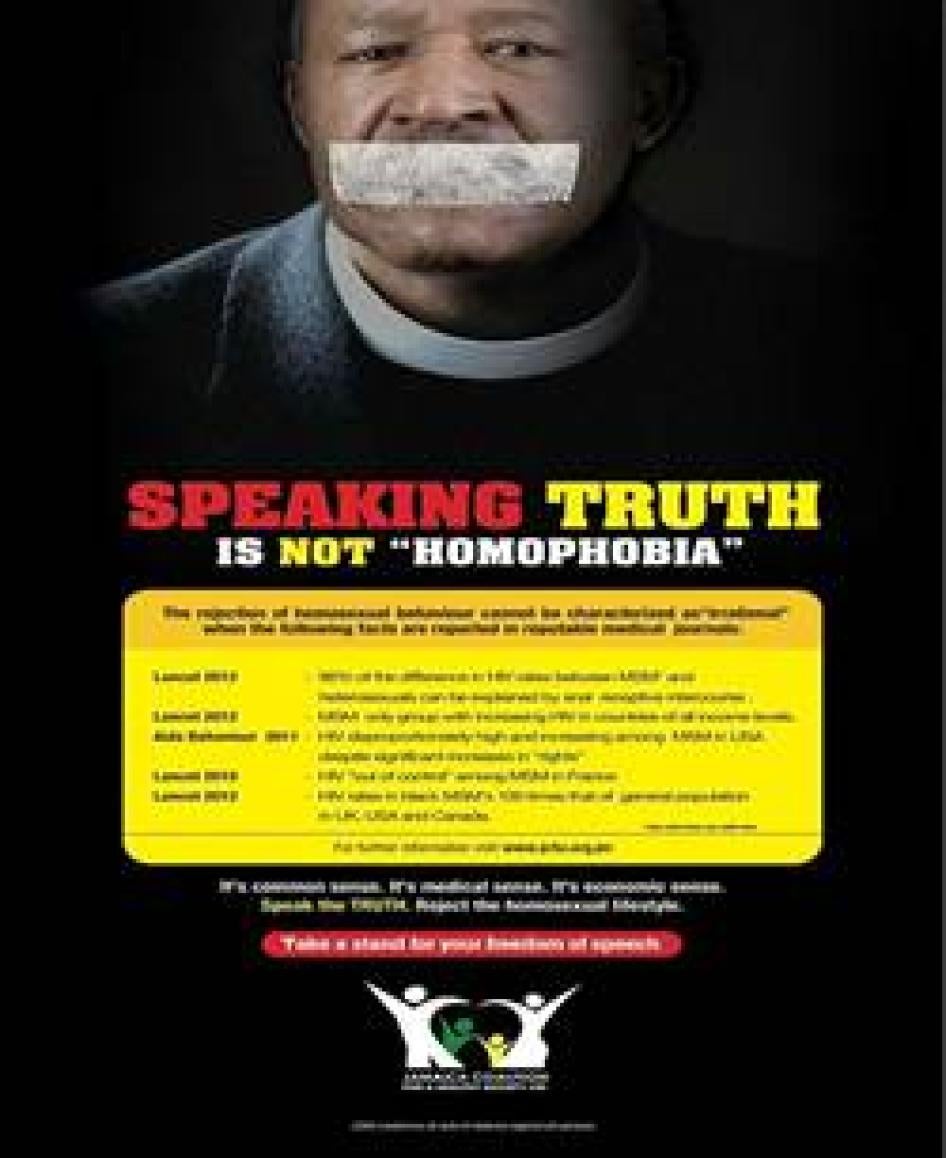

In response to the International Day against Homophobia and Transphobia (IDAHOT), celebrated by LGBT rights activists around the world each May 17, JCHS produced, in 2013, a poster misusing HIV statistics to condemn “homosexual behavior,” and claiming that the voices of those who oppose such “behavior” are being silenced.[7]

In June 2014, an ad-hoc coalition of religious groups, Jamaica CAUSE (Churches Action Uniting Society for Emancipation), organized a mass rally, estimated at 25,000-strong, in Kingston against “the homosexuality agenda” and the repealing of the buggery law.[8]

Media

Media reflect and fuel widespread homophobia in Jamaican society. Broadsheets publish cartoons that stereotype, ridicule, foment hate against, and demonize LGBT people.

Sensationalist and homophobic articles have also appeared under headlines such as, “Gay men, bystanders in missile-throwing brawl during road march” and “Stand your ground against homosexuality.”[9] Some of these types of headlines and associated links to the cartoons have since been removed from online editions after the papers received complaints.[10]

The Jamaica Observer did not grant Human Rights Watch permission to reproduce several cartoons that illustrate the stereotyping of LGBT people. However, they can be accessed on the newspaper’s website: http://www.jamaicaobserver.com/tools/cartoons/.

For example, a cartoon published in the Jamaica Observer in January 2013 depicts the Jamaican prime minister clutching a copy of the buggery law and being pulled in two different directions by a cleric and a gay man. The gay man, wearing a pink purse and made up in white face, tries to disrobe her. “Tek it off!” he exclaims, conveying a message that LGBT people are both dangerous and want “special rights.”[11]

Another Jamaica Observer cartoon published in March 2013 depicts gay men as criminals, shattering shop windows and hurling stones at figures representing “police” and “public,” as gay rights groups, portrayed as a nonchalant Uncle Sam, whistle and look away.[12]

A cartoon published in the Jamaica Observer in December 2012 shows a child unperturbed by men dressed in intimidating traditional holiday costumes, while in the next panel he flees in terror from a gay man in stereotypical dress.[13] Another Jamaica Observer cartoon from July 2011 mocks Jamaicans for Justice (JFJ) former Executive Director Carolyn Gomes, and ridicules J-FLAG with a stereotyped image of gay men responding to the head of the Organized Crime Investigation Division (OCID), Senior Superintendent Fitz Bailey, who accused gay men of being behind a form of organized crime known as “lottery scams.”[14]

In November 2012, after University of Technology security guards were filmed beating two men for being gay and encouraging a mob to “beat the fish,” Jamaica Observer published a cartoon depicting a fish sitting in a classroom, reinforcing derogatory slang for gay men as “fish.”[15]

Both The Gleaner and the Jamaica Observer published editorials in 2012 in support of LGBT rights and the repeal of the buggery laws.[16] However, this has not prevented them—particularly the Jamaica Observer—from also publishing homophobic rhetoric.

Such articles and cartoons may breach guidelines laid out in the professional code of practice for Jamaican journalists and media organizations, ratified on August 8, 2011:

The media should avoid prejudicial or pejorative reference to a person's race, color, religion, sex or sexual orientation or to any physical or mental disability or handicap. The media should avoid publishing details of a person's race, color, religion, sex or sexual orientation, unless these are directly relevant to the story.[17]

Music

A number of popular Jamaican musicians perform and produce music that contains inflammatory lyrics with regard to LGBT people. Emblematic of this genre is dancehall artist Capleton’s 1990 hit “Bumbo Red,” which remains popular and calls for gay and lesbian people to be shot in the head:

Lick a shot inna a battyman head! Lick a shot inna a lesbian head! All sodomite dem fi dead, all lesbian dem fi dead.[18]

Capleton and other dancehall artists who have a history of making homophobic comments or delivering anti-LGBT rants from the stage during performances—including Sizzla Kalonji, Buju Banton, Beenie Man, and Vybz Kartel—signed a 2007 agreement called the “Reggae Compassionate Act,” in which they promised not to promote hatred and violence towards LGBT people in their music.[19] Despite this, Sizzla Kalonji, Capleton, and other reggae performers, continue to perform anti-gay songs or promote homophobic ideology.[20] On December 26, 2013, Sizzla Kalonji sang the following at the Sting Music Festival in Jamaica:

I don’t care who want vex, Jamaica no support no same sex …

I don’t care who want vex, Africa no support no same [sex] …

Them say, “Sizzla, you sing too much anti-gay lyrics.”

Me just read the bible and get away with lyrics….

Burn out the lesbian, burn out the gays with the lyrics.

I don’t care who want vex, rastaman no support no same sex.

Dem a tell me bout “free speech,”

so me tell de raper man dem fe leave de beach.

And me tell the pedophile dem flee the creech.

Tell de lesbian dem flee de street and the battyman [screaming].[21]

Some artists have increasingly refrained from using homophobic lyrics at their concerts and have issued personal letters of apology following poor publicity and cancelled concerts abroad, although some of them have since denied apologizing. [22] Beenie Man issued a video statement in 2012, saying, “…I have nothing against no one. I respect each and every human being regardless of which race or creed, regardless of which religious belief … regardless of which sexual preference you have including gay and lesbian people.” [23]

A small but growing number of Jamaican artists are openly supportive of LGBT rights, including Mista Majah P (based in California) and Tanya Stephens. [24]

Politics

Homophobic rhetoric is not limited to the cultural sector. During his term as prime minister from 2007 to 2011, Bruce Golding of the Jamaica Labour Party (JLP) publicly expressed homophobic views on several occasions. For example, in a 2008 BBC interview, Golding said he would not allow gays in his cabinet.[25] In 2010, Golding stated, “The encouragement or recognition of the appropriateness of the homosexual lifestyle is going to undermine the effectiveness of family … and, in that process, undermine the basic fabric of a society.”[26]

A year earlier, in 2009, Ernest Smith, a JLP member of parliament (MP), claimed that LGBT people are merely “seeking publicity” when they report cases of violence. He said:

We’re not saying that gay people should be obliterated from the face of the earth ... but because your behavioral pattern is in breach of all decency … do not try to impose your filth on others, don’t force others to accept you and your filth.[27]

In August 2013, Education Minister Ronald Thwaites said at a press conference to launch the new Health and Family Life Education Teachers’ Manual that while the manual promotes tolerance on all grounds, “We will not be grooming Jamaican children for homosexual behavior…. [W]holesome joyous relationships are between men and women.”[28]

These negative attitudes towards LGBT individuals are reflected in the findings of a 2011 national survey of attitudes towards same-sex relationships in Jamaica, conducted by a University of the West Indies research team, which found that 85.2 percent of participants were opposed to legalizing homosexuality among consenting adults.[29]

Political views toward homosexuality are not monolithic. Then-opposition leader Portia Simpson Miller disagreed with Golding’s views on LGBT people in a 2011 debate, stating that no one should be discriminated against due to their sexual orientation.[30] Her opponent in that debate and the current opposition leader, Andrew Holness, said in a May 2014 interview that he, too, opposed discrimination based on sexual orientation and would allow gays in his cabinet.[31] Despite his homophobic statement above, Minister Thwaites has also spoken in support of tolerance and non-discrimination (see Section VI).

Mistrust of Police

Most of the LGBT people we interviewed said they did not even report criminal acts to the police, fearing they would be unresponsive because of the victim’s sexual orientation or gender identity.

“I’ve heard terrible things about gay people going to the police and police turning on them. I would never dare go to the police,” said Jane, a transgender woman from Kingston.[32]

Genie O., a potential murder witness, said he did not report the shooting of his friend in Greenpond in 2010 because he, too, feared the consequences:

I didn’t call the police. I know much wouldn’t be done and I didn’t want to get involved. Once you are found to be associated [with gay men], your life would be at risk and you could be stigmatized as one of them. Most times you worry and cry about it and keep it to yourself and move on.[33]

Winnie R. told Human Rights Watch of her complete distrust of the police after having been groped by a police officer, and on separate occasions, after trying to make criminal reports to the police after being raped and robbed. Winnie R. said:

Justice for all, that would be my motto. It doesn’t matter about your sexual preferences, it’s not about your color, it’s not about how much money you make, everyone should be treated equally. When it comes to a crime, it should be dealt with in the correct manner. It shouldn’t be that I should be made to [feel] less of a person because of who I sleep with. If I go to a police station and my initial report wasn’t given the light of day, why would I ever go to the police station to report a crime? I’m not walking into a station with a gun but I am treated like a criminal. I’m told I deserve to be shot.[34]

HIV and Homophobia

Jamaica has a high HIV prevalence rate: just under 2 percent of adult Jamaicans (approximately 32,000 people) are estimated to be infected with the virus.[35] Within the Caribbean, only the Bahamas and Haiti have comparable rates of HIV infection.

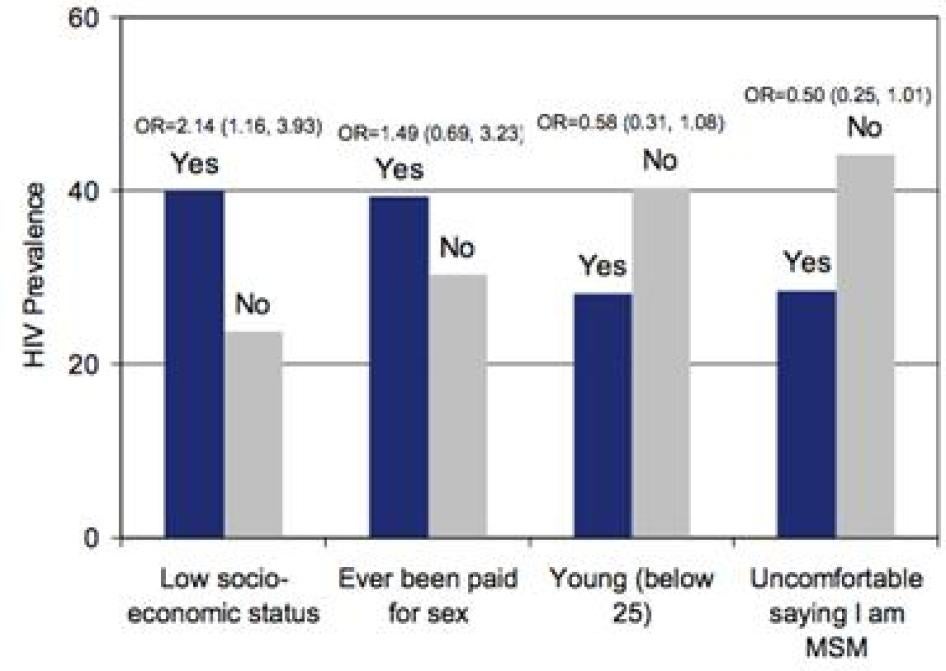

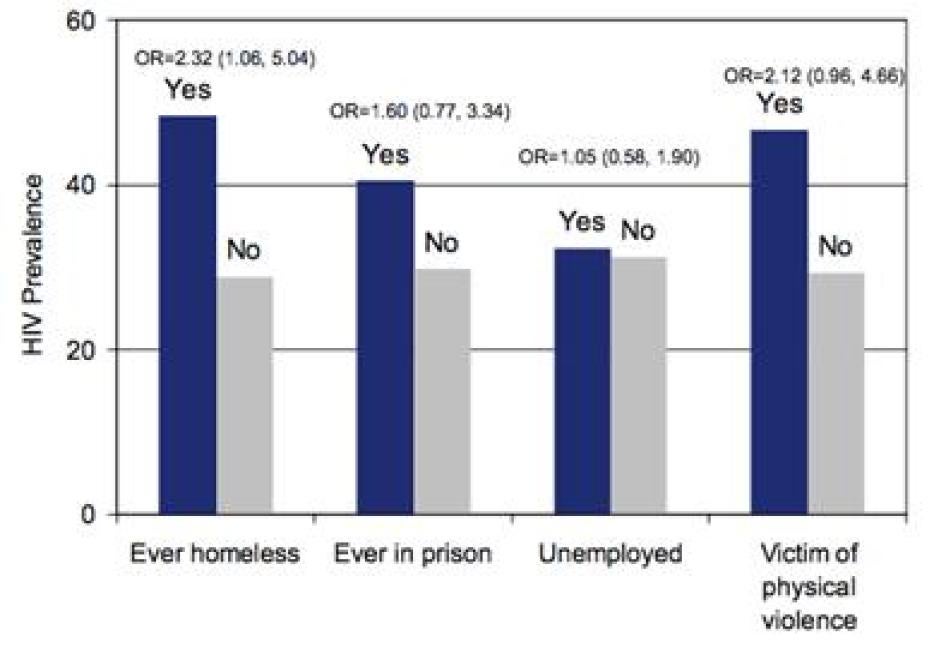

Jamaica has the highest HIV prevalence rate amongst MSM in the Caribbean.[36] Within the country, HIV prevalence among MSM remains considerably higher than general population rates—32 percent compared to just under 2 percent in the general population, according to recent data—and has not declined since 2007.[37]

Among the factors that continue to drive the epidemic in Jamaica amongst MSM are:

Stigma and discrimination are significant drivers of the epidemic, hampering the implementation of services for MSM, and the willingness of MSM to access heath care services.[41] “There is a fear that they might not be treated, might be looked down at and that people will label them,”Pascal G., an outreach worker with the Jamaican Network of Seropositive (JN+) said.[42]

Young and homeless MSM are vulnerable to sexual violence, including rape, which increases the risk of infection.[43] One homeless male sex worker in Montego Bay told Human Rights Watch that clients pay significantly more for sex without condoms, making it difficult for economically vulnerable individuals to negotiate condom use.[44]

The emergence and widespread availability of antiretroviral therapy (ART) since 2004 has reduced some of the HIV-related stigma and discrimination that was widespread when Human Rights Watch conducted research in Jamaica in 2004. The individuals we interviewed then emphasized the prejudice they experienced due to noticeable physical changes caused by the illness, and the contempt they endured when attempting to access HIV-related care.

Major international donors and multilateral agencies—including the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria (Global Fund), the World Bank, and the US President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR)—have invested millions of dollars in financial and technical assistance to address HIV among MSM in Jamaica, including efforts to address stigma.[45]

However, since the World Bank reclassified Jamaica as an upper middle-income country in 2010, Jamaica is no longer eligible for significant funding and key donors may soon reduce or withdraw financial support. The Global Fund has already significantly reduced funding and is due to withdraw altogether by 2017.[46]Government officials, civil society, and donors have expressed concern about the loss of this funding and its impact on most at-risk populations, including MSM, as well as on the HIV response more broadly.

II. Violence against LGBT People

Physical Abuse

Physical and sexual violence, including severe beatings and even murder, are part of the lived reality of many LGBT people in Jamaica. The level of brutality leads many to fear what could happen if their sexual orientation or gender identity is disclosed.

In many cases, perpetrators appear to have been private actors who felt that they had the moral authority to “rid the community” of LGBT people and had no fear of arrest from the authorities. In other cases, police were themselves the perpetrators.

Between April and June 2013, Human Rights Watch interviewed 71 self-identified LGBT people. These interviews elicited 56 accounts of physical violence that took place between 2006 and 2013 experienced by 44 LGBT people, the vast majority of which appeared to be directly as a result of their sexual orientation or gender identity.

Some of the individuals we interviewed had more than one experience of physical violence. These reported acts of violence included rape; being chopped with a machete; being choked; being stabbed with a knife; being shot with a gun; being hit with boards, pipes, sticks, chairs, or brooms; being attacked by groups ranging from 5 to 40 individuals; and being slapped in the face with hands or with guns.

J-FLAG recorded 231 incidents of attacks against LGBT people between 2009 and 2012, including home invasions, physical assaults, and mob attacks.[47] This number of homophobic attacks is likely to be underreported. In terms of the types of physical assaults documented, the information that we garnered closely paralleled the yearly incident reports collated by J-FLAG.[48]

The following incidents of violence and alleged attacks, reported during a four-month period in 2013, illustrate the regularity with which such violence occurs:[49]

- On July 22, 16-year-old Dwayne Jones, wearing female attire, was stabbed and shot to death and thrown into nearby bushes at a public street-dance near the resort city of Montego Bay (see Summary). At time of writing, no one had been arrested.[50]

- On August 1, an angry mob surrounded the home of two gay men in the parish of St. Catherine, “intent on getting rid of the men.” The crowd was yelling, “Dem fi cum out a ya (they must leave our community).” The police intervened to rescue them.[51]

- On August 22, community members barricaded five gay men inside their home in the parish of Manchester and threatened them with bats and sticks. The police had to rescue the men.[52]

- On August 26, two gay men in the town of Old Harbour had to flee the scene of a car accident and seek shelter at a police station when onlookers realized they were gay and demanded they leave their community.[53]

- On September 16, Edwin M., a young gay Jamaican man from Hanover parish, was chased with his friend and stoned by a mob shouting homophobic insults. He suffered head injuries.[54]

- On October 25, Keshema Tulloch, a Jamaican lesbian, was punched in the face by a man who called her a “sodomite.” When Tulloch chased her attacker with a knife, police shot her in the arm and chest.[55] J-FLAG, which has followed the case, told Human Rights Watch that Tulloch has since been charged with assault. Her male attacker has not been charged.[56]

Human Rights Watch interviewed 12 LGBT people who said they knew of a friend, partner, lover, or associate who had been murdered because of their real or perceived sexual orientation or gender identity. Other forms of violence described to Human Rights Watch include arson attacks; mob violence; and sexual, physical, and verbal abuse.

Among the cases that victims described to Human Rights Watch were:

- Ten cases of sexual assault against eight

lesbian women, one transgender woman, and one gay man, including cases of rape

at knife or gunpoint;

- Ten mob attacks;

- Eighteen cases of serious

injuries that included:

- Shooting injuries, including one that resulted in paralysis;

- Stabbing injuries;

- Bruises, cuts, swollen arms, and scars;

- Broken bones.

In the 56 incidents, the victims themselves told us of the violence they had suffered, and with respect to the experiences of 11 individuals, we were able to examine police receipts documenting the incident, court proceedings, or letters and incident reports from J-FLAG.

In at least two prominent cases, the “gay panic” defense—when a perpetrator claims that an unwarranted homosexual sexual advance resulted in murder—has been used to justify a killing. For example, on November 7, 2010, Kevon Martin was charged with killing Steve Lindo, a gay man, by stabbing him with scissors. The magistrate granted Martin bail, despite his not having a known address, on the grounds that Martin had appeared to be acting in self-defense in response to Lindo’s demands for sex.[57] The case was still in progress at time of writing.[58]

Human Rights Watch spoke with LGBT individuals who said that their socioeconomic status was an important determinant in either shielding them or making them more susceptible to physical and verbal attacks. Although no one is immune to negative attitudes or behavior towards LGBT people that permeates Jamaican society, middle-class LGBT people explained that they could afford to live in safer, more affluent areas, drive private vehicles, and access social networks more tolerant of LGBT people than poor and working class Jamaicans, many of whom spoke of being vulnerable to verbal attacks and physical abuse.

Faith M. and Denise C. have been together for over four years. Faith M. told Human Rights Watch that their middle-class backgrounds “protect and insulate” them from attack,[59] while Raheem D., a 20-year-old gay man from a lower-income area in Montego Bay, told Human Rights Watch:

I don’t feel safe walking down the street because people on the street, my neighbors say, “Fish, battyman,” and that I should get out of the community. I am always afraid they could attract a crowd and hurt me.[60]

Among the various types of physical abuses endured, interviewees identified two forms—mob attacks and arson—as notable for being both extreme and targeted at LGBT people.

Mob Attacks

Human Rights Watch interviewed 10 people who reported suffering mob attacks because of their sexual orientation. All the accounts involved gay men that were set upon by groups ranging from 5 to 40 men. In some cases, police intervened and saved these individuals from further harm. However, none of the individuals that we interviewed were aware of any investigation or arrests that were made in relation to the mob attacks.

Rahim Q. told Human Rights Watch that in March 2013 at approximately 6 p.m., he and a group of about 14 friends were attacked by a violent mob of about 10 men:

We were there under the tree socializing and some men came with machetes, stones, [and] other weapons trying to beat us. They called out, “Battyman fi dead.” We saw them coming, so we had a chance to escape…. We had to jump into a pool of water in order to escape.

One if his friends who had his nose broken went to the Cornwall Regional Hospital.

He went by himself because if he went with one of us he would have been stigmatized. Persons would say things, “Those guys are gay,” “Look at those battymen there.” Most of the time we go alone [to avoid this]. Later that evening, I saw him. He went to the police, but the police didn’t make any effort, he told me.[61]

Arson

Human Rights Watch interviewed one gay man and one transgender woman whose homes were set on fire in attacks apparently motivated by a desire to force them from the community. Three other victims told us that perpetrators threatened to set them ablaze or torch their homes.

Carol C., a 30-year-old transgender woman, told Human Rights Watch that community members had warned her she would be “dead before the year end.”[62] Soon after, her aunt called to say her house was on fire.

When I went to the area, I could see from quite a distance the smoke in the air. By the time I got to the house the fire brigade were busy putting out the fire. People were standing outside, some seemed happy. I left and came back the next day and there was still smoke, the older [wooden] part of the house burnt to the ground and the concrete sections remained standing.

Marcello T., a resident of Ocho Rios, told Human Rights Watch that a gay man’s shop in his neighborhood was burned down. He said, “I think it was done on purpose because they were saying he was a funny man and they don’t want no funniness there….”[63]

Silroy N. and his male partner of 18 years, who had lived in Westmoreland for a year-and-a-half with their 9-year-old daughter, left the area after locals began to speculate they were gay. Silroy told Human Rights Watch:

The physical and verbal threats became unbearable and unavoidable. We even received threats that they [members of the community] would burn down our house: People would say, “Batty boy, why don’t you leave the community. We don’t support them thing. We’re going to burn your house down.”

“That was enough for me to move,” Silroy said. “We have a daughter.”[64]

Verbal Abuse

At least 48 physical assaults that interviewees described to Human Rights Watch were accompanied by slurs that referred to the victim’s perceived or real sexual orientation or gender identity.

Sexual assaults on LGBT people are frequently accompanied by verbal abuse that suggests the assaults are motivated by homophobia and justified by the perpetrators as an attempt to “convert” the victims to heterosexuality.

In one such case, Patsy B., a 25-year-old college student in Kingston, told Human Rights Watch that a male friend raped her in his house in March 2013:

All of a sudden he jumped on me, “Do you want to know what a real fuck feel like?” He attacked me and raped me. He did what he had to do. I was screaming…. I saw him recently at Half Way Tree (a neighborhood in Kingston). I heard him yelling, “Yo, I fucked that girl, I fucked that girl.”[65]

III. Police Failures to Act

The JCF Policy on Diversity, launched in 2011, established “operating protocols … to be strictly adhered to as soon as it is established that any individual or group was victimized because of their religion, ethnicity, sexual orientation, class, colour, creed or political ideology”—and has resulted in some progress.[66]

But it was clear from the series of interviews we conducted that, often, policy and practice are far apart. Human Rights Watch interviewed LGBT people who said that when they tried to report a crime, police made derogatory comments and failed or refused to take a report, even well after the Policy on Diversity was established.

The fact that police themselves are sometimes perpetrators of violence and extortion against LGBT people makes LGBT victims even more unlikely to seek police assistance.

Failure to Intervene, Investigate, and Arrest

In some cases, police appear to have failed to intervene, even as attacks were happening.

According to Devon O., in January 2013, police stood by and watched while a crowd of about 30 people—shouting insults regarding his sexual orientation and armed with knives, machetes, and sticks— beat him for about 20 minutes. He said police finally removed him from the crowd and placed him in a police van to protect him from the mob but then handcuffed and beat him (see Section IV).[67]

In many cases, interviewees described police failing to arrest suspects or investigate homophobic incidents: in only 4 of the 56 cases of violence documented by Human Rights Watch were victims aware of any arrests of suspects by the police.

Such inaction is not unique to LGBT cases: Jamaica has one of the highest violent crime rates in the world, and police response is often seen to be lacking.[68] Indeed, a majority of Jamaicans believe that the justice system is corrupt and that “powerful criminals go free”;[69] only 9 percent of Jamaicans believe police “treat people equally”; and only 12 percent believe they show “courtesy to ordinary civilians.”[70]

However, Human Rights Watch research shows that for LGBT crime victims, bias based specifically on gender identity or sexual orientation directly contributes to the inadequate police response.

Anne I., a 35-year-old transgender woman who does sex work, experienced an attempted rape in December 2008 by two men at knifepoint who propositioned her for sexual services. The exchange turned violent when the men realized Anne had male genitals. She told Human Rights Watch:

They placed a cardboard down [on the ground] to feel me up. One of the guys came behind me, while the other man started to take off my pants. He yelled, “You are a batty man.” One of the guys started to choke me, while the other guy started to stab me up. They broke my nose and slashed my throat.

Anne managed to run away, and found a sex worker outside a club who called the police on her behalf. The police took her to Kingston public hospital and recorded her testimony, but to Anne’s knowledge, there was no follow-up.[71] Police did not respond to an inquiry from Human Rights Watch as to whether there had been any progress in the case.[72]

In an extreme case documented by Human Rights Watch, armed men in 2007 attacked Tanasha G. as she sat in her car, shooting her three times in the chest, buttocks, and leg as they called her a “sodomite gal.” Police never followed up.

She spent a month-and-a-half in Mandeville hospital, and another month-and-a-half in a rehabilitation center and remains disabled and wheelchair-bound due to the attack. “The police came [to the hospital] the next day and spoke to my mother,” she said. “I never spoke to the police and they never followed up.”[73]

Police also do not appear to have followed up adequately on the July 2013 murder of Dwayne Jones, a gender non-conforming 16-year-old, who was beaten, stabbed, and shot to death in St. James by partygoers when they discovered her biological sex.[74] Although police interviewed witnesses and provided information about the murder investigations to J-FLAG, no one had been arrested for the attack at time of writing.

Human Rights Watch interviewed seven lesbian women, one transgender woman, and one gay man who told us that they were raped or threatened with rape as a result of their sexual orientation or gender identity, in some cases at knife- or gunpoint. Only one of these cases resulted in a police investigation that eventually led to an arrest, prosecution, and conviction, but even then, the accused was ultimately acquitted on appeal.[75]

FAILURE TO INVESTIGATE: WINNIE AND NADINE’S STORY

On August 10, 2012, Winnie R. and Nadine B.—two lesbians—returned home after a party around midnight. As they got out of the car, two men disguised with bandanas across their faces ambushed them and forced them inside their house at gunpoint. Initially they thought it was a robbery. Winnie R. told Human Rights Watch, “I said that they could take whatever they want. One of the gunmen said, “We’re not here to take your stuff.” The other gunman said, “You not with nuh man [You aren’t with guys].”

Nadine B. said that after raping her, the gunmen forced her to watch them rape Winnie:He made [Winnie] lie on the bed face down. I realized that he was going to have sex, so I said, “You know, I have condoms, to make sure that she doesn’t get AIDS or get pregnant.” I thought they were just trying to prove a point because she doesn’t dress like a girl. The other guy was there with a gun to my head. He didn’t take his clothes off. He just unzipped his pants and just had sex with her [without a condom].

Afterwards, the men left and threatened to kill the women if they informed the police. Winnie and Nadine did so anyway. But when they went to Greater Portmore police station, Nadine said the police verbally abused them and failed to act. She said:

The police officer [asked] us if we were related, and I said we were just friends, sharing the place. The officer then responded, “You’re sodomites, look at her, a sodomite them, why did you come to the police station? A fuck you want, a fuck you get.” I said, “When I want sex, I know where to get it and who to get it from. I came here to report the crime.” He said, “Look at that one there. She is so pretty. And she a suck pussy?”

I was so upset that I started to walk out.… I was there saying, “This is how you treat people. What if I were your sister? What if I were your mother?”

Those men were in our house for four hours. Imagine having to go through that for four hours and then you go to the police officer and he says, “Sex you want sex is what you get. Dirty lesbian girl deserve what you get.” This is what I get from a police officer who took an oath to serve, protect, and reassure. How was he protecting me? How did he serve me? How did he reassure me?

Winnie and Nadine left the station without being able to file a police report.

Although police are instructed to record hate crimes, they lack a clear definition of what constitutes such a crime, and documenting these incidents appears to be under-prioritized. As one senior police official told Human Rights Watch:

Jamaica doesn’t have a well-developed crime recording system, murder and other crimes. There is a significant underreporting of crime.… Reports are not transmitted [from local police posts] to the central recording/statistics branch. Almost nothing on hate crime is recorded…. Hate crime is not high up on the agenda, guns and other crimes such as domestic violence are.[76]

Only one case that Human Rights Watch reviewed—that of Kingston University student Jolly K.—resulted in a police investigation and arrest.

Jolly K. told Human Rights Watch that she had agreed to an in-person meeting after chatting online with someone who presented herself as a woman. She soon realized it was a set-up: when she reached the agreed meeting place with a friend, a man wearing a handkerchief across his face held her at gunpoint:

He cursed at us, “Pussyhole.” He put the gun at the back of my head and directed us to hold our hands up and walk.

After robbing us of about J$30,000 (about US$270) and a camera, he forced her to perform oral sex, and to watch as he raped her friend. “She is a butch lesbian and has never been with a man.[77]

Jolly K.’s father contacted a senior police officer at Twickenham police training center [Jamaican Constabulary Force Training Branch Twickenham Park], who directed her to the Spanish Town Centre for the Investigation of Sexual Offences and Child Abuse (CISOCA), where she reported the assault to the head of CISOCA. “When she read what happened, she put down the paper,” Jolly K. said, “and looked up, and said ‘Jesus Christ, another one.’”

Jolly K. accompanied CISOCA officials to show them where the incident occurred. Several days later, police arrested a suspect, who was found with Jolly K.’s phone and other stolen items. Jolly K. and her friend returned to the station to provide a positive identification for the suspect, and to identify their stolen items. Tried and convicted, the suspect was sentenced to 29 years in prison on rape, theft, and arms possession charges. However, he was subsequently acquitted on appeal for reasons related to the identification process.[78]

IV. Police as Perpetrators

While the cases in the previous chapter dealt with police response to violence carried out by private citizens, in some cases the police also directly victimize LGBT people.

Cases of police violence toward LGBT people appear to have decreased in the decade since Human Rights Watch documented such violence in our 2004 report, Hated to Death. However, the persistence of even isolated cases is of great concern given the police’s role as a source of protection.

At the root of much police abuse appears to be the same intolerance and homophobia found in Jamaican society more broadly.

For example, Human Rights Watch interviewed a foot patrol police officer in Montego Bay who said LGBT people were criminals, and deserved the violence they experienced.[79] A detective corporal from CISOCA, also in Montego Bay, told Human Rights Watch: “Gay men need to just stop being gay.… They are just greedy. I even think that the Police Force Order on Diversity should stop.”[80]

Verbal Abuse

In a homophobic environment, LGBT people are particularly susceptible to verbal abuse from members of the broader public. Police also perpetrate verbal abuse. In several cases, police expressed sympathy for the attackers and support for their homophobic beliefs, and further verbally abused victims who turned to them for help.

After Kevin G., an HIV-positive 17-year-old from Montego Bay, was severely beaten by his brother in February 2013 for being gay, he went to Montego Hills police station to report what had happened to him. “I waited four hours,” he said. “They didn’t do anything. The police said, ‘That’s the reason he is being beaten. He’s a battyman, a fish.’”[81]

One young homeless gay man, Bryan T., said that New Kingston police promised to investigate an incident in which construction workers chased him in February 2013—but then appear to have failed to do so. He added that he and a friend were told they could not use the police officer’s pen to sign the complaint: “He said, ‘You are a battyman. We don’t want battyman to use our pen.’”[82]

Cutie G., 18, who had been living on the streets for four years after leaving home, described both physical (including pepper spraying and being hit by batons) and verbal assaults by police. In one incident, he said, he was being chased and ran to the police station for help. “Come out of the station,” he recalled them saying. “We don’t want to help you. Go kill yourself.”[83]

Physical Abuse

Devon O. told Human Rights Watch that after a large crowd beat him in January 2013, police handcuffed and physically assaulted him in the police car and station:

The policeman in front hit me three times with his baton, and said: “Hey, you’re a fish, and you are a battyman.” There were two policemen in the car, one in the front and one beside me. They were hitting me with their elbows. Then, they stopped the van and they continued to hit me. I feel the licks come from the front and the side.

When they arrived at the station, a policeman kicked him out of the car. “Fish don’t last long in St. Ann,” one policeman said inside. “Everyone who comes in comes out dead.”

He was handcuffed the whole night, released the next morning, and told he “should go to church.”[84]

Michael B., a 20-year-old homeless gay man, told Human Rights Watch that abuse at the hands of the police is a regular occurrence. He recalled that one day in the summer of 2011, at around 5 a.m.,

…The police surrounded us and told us to leave the street because we were loitering. One police officer took out his baton and started beating us one by one. We were up against the wall. Four cops, one beating us, the others standing to make sure we couldn’t leave.[85]

Michael said that on other occasions, police had used tear gas and pepper spray against him and his friends:

The police would come over and tell us to leave the road, and they would run us with pepper spray, throw stones, and chase us down like dogs. The police don’t like homosexuals.[86]

Carlton J., 25, told Human Rights Watch that in 2006, he was confronted by a policeman while on the street in Kingston:

The police beat me with a gun in my back, called me battyman. The policeman said “How come mi so nice and turn homosexual [how can someone so good-looking become a homosexual]?” He beat me so that it left a gun mark in my back.[87]

Sexual Abuse

In a small number of cases victims described sexual abuse at the hands of police.

John B., a 23-year-old gay man, recalled how a policeman kidnapped and raped him at gunpoint in 2007, when he was 17 and homeless. John B. said:

One Sunday evening he called me over, handcuffed me, and told me that I was arrested for loitering. He drove me to a field, pulled my pants down, removed my handcuffs, put his gun to my head, and raped me. I grunted and screamed. When he was finished the police officer said, “If you tell anyone, you’re dead.”[88]

Extortion

Another form of victimization is through extortion. Human Rights Watch interviewed five LGBT people who were subjected to police extortion. All were threatened with arrest, and asked to pay a significant sum to avoid imprisonment or the risk of having their sexual orientation or gender identity revealed to media, friends, family, or the broader community.

Sean T. recalled:

In September 2012 I was in a car with a friend by Emancipation Park. The car was off and the lights were off. The police ordered us out of the car. The guy was married, so he didn’t want it to go too far. The police asked for money. The guy found the money and paid them J$50,000 (about $445). Then they demanded more, [and] in the interest of protecting his marriage, he paid more.[89]

On April 9, 2013, police stopped and threatened to arrest Stephen V., a Jamaican man who lives in Canada and was visiting Jamaica. He told Human Rights Watch:

I was driving to Port Royal to have lunch with my friend. On our way, he wanted to stop to go to the bathroom. I pulled over to the side of the road, close to the bushes so people passing by wouldn’t see him.

My friend came out of the bushes and was pulling his pants up. A police car blocked us, and two police jumped out the car. One of the police officers said to me, “You guys are battymen.... You two were having sex.”

Stephen said that after warning him, “It’s my word against yours,” the policeman threatened to arrest and charge him with buggery, and expose him to media and his family.“In Canada it may be okay to be gay,” he recalled the policeman saying. “In Jamaica it is not okay.”[90]

When the police officer threatened to take away Stephen V.’s passport and hold him in custody, preventing his return to Canada, Stephen asked the police officer how much money was needed to prevent the arrest. The police officer demanded J$20,000 (about $180). He then escorted Stephen and his friend to an ATM to retrieve the money.

Jolly K. also said that police officers bribed her to avoid arrest when they found her in a parked vehicle with a female friend around midday, in Greater Portmore, in early 2010:

I thought that they were going to drag us into the police station. I wasn’t scared about what the police would do, but what would happen afterward. At that time, I was living with my grandparents.[91]

The police let the two women go after Jolly K.’s girlfriend paid them a bribe of J$5,000 (about $45).

EXTORTION: LUIS’S STORY

Luis M., the only person whom Human Rights Watch interviewed who was jailed for being gay, was arrested and charged with gross indecency and buggery in Kingston in October 2011. Police extorted him and his partner, Robert U., after they found them parked in a secluded area, where they had been kissing and having sex. Luis told Human Rights Watch that both he and his boyfriend were fully dressed and sitting in the car when three police officers approached and said, “Ah two men in there. It must be battymen them.”

As one police officer pointed his flashlight at them, another began videotaping them with his phone. When Luis and Robert turned their faces away, the policemen ordered them to look at the camera. The officers searched around the vehicle and found two used condoms. They then ordered them out of the car, and according to Luis, said:

“You have money? Because you’re going to need money to get out of this.”

The police ordered Luis and Robert to drive to the police station in their own car as the police officers said they didn’t “want no fish in their vehicle.” The officers continued to demand money from them, asking for J$100,000 (about $890) for each police officer.

Luis and Robert were charged with buggery and gross indecency. J-FLAG secured the services of a lawyer, who came to the police station and recorded their statements. Other inmates verbally and physically attacked them: on one occasion, four men pushed them towards the grill of the cell and punched them. Luis and Robert shouted for help for over 15 minutes, but no one came.

They were released on bail after two weeks in detention and given a court date three months later. The lawyer explained they could either go to trial or accept a plea bargain for gross indecency. They accepted the latter and were offered a choice of a fine of J$250,000 (about $2,225) or six months in prison. Luis took a loan from his mother to pay the fine, which he was still repaying when we interviewed him in April 2013.

V. Public and Private Sector Discrimination

The stigma and discrimination that LGBT people face in Jamaica seeps into everyday activities, such as accessing health care, attending school, going to the movies, shopping, or riding a bus. Human Rights Watch talked to LGBT people who were verbally abused and confronted in public and private spaces about their real or perceived sexual orientation or gender identity.

Health Care Discrimination

LGBT patients faced a combination of ignorance and discrimination in accessing health care, including incidences of homophobia and transphobia among health workers. In some cases, the fear of negative responses from health care providers keeps LGBT individuals from accessing care.

When they do access care, many told Human Rights Watch they are not comfortable sharing information about their sexual orientation or HIV status. Several LGBT people told Human Rights Watch that nurses, doctors, and other staff had disclosed their confidential information to others—a lack of privacy not confined to LBGT people.[92]

Anne I., a transgender woman, described the level of hostility that she received at Kingston Public Hospital when she tried to access treatment for the knife wounds she received after a vicious attack by two men in 2008:

The doctor asked me what happened. I told him the story. He called the porter and said, “You have to look at this.” He called various people to look at me. He pulled down my pants to look at my sex organ. He said, “You should not let man [men] sex you.” He called about three porters and another man [a patient] to look at me.

When Anne I. returned to the hospital for follow-up treatment, she was physically assaulted by one of the porters to whom she had been exposed. “The porter recognized me and said ‘Who you a look pan [Who are you looking at]?’ He took out a knife and he cut me in my face.”[93]

Two nurses locked Anne into a room, apparently to protect her, and she went without treatment through the night. The next morning, she received treatment for her knife wounds, but was also subjected to further humiliation. Anne explained, “Some guys [auxiliary staff] wanted to know if I was a woman, and for me to let them see my breasts.”[94]

A senior Ministry of Health official shared the case of a gay man who had Human papillomavirus (HPV) that remained untreated until his health seriously deteriorated:

They can’t officially turn away people, so what would happen is that he would come in with fever and drainage problems related to HPV lesions [on his anus]. I sent him to dermatology [at a public hospital] but they don’t do large lesions. I sent him to surgery with a referral for HPV lesion removal. They gave him medication for fever, and antibiotics, and then … instead of taking care of him, they discharged him and said to return. This happened six or seven times throughout the year from 2011-2012.

By the time he got surgery at the end of 2012, the official said, the cancer was well established and he had to have almost a total colostomy.[95]

Stigmatizing treatment from health workers can dissuade LGBT people from seeking critical services including HIV testing, as Florio P.’s story demonstrates. Florio said he normally goes for testing every six months at Red Cross or Cornwall Regional, but in 2009, he tried to get an HIV test at St. James Health Department “Type V” Clinic in Montego Bay. He said:

I went to make an appointment for an HIV test. The reception asked, “Why are you here? Are you having sex with a man?” [I responded] “Do I have to answer the question?” The receptionist said “Bwoy, do you fuck men? Either you fuck men or not?” I felt so uncomfortable that I left. Other people could hear this. People who were in the front row laughed.[96]

To avoid the real or perceived stigma and discrimination associated with being identified as gay or HIV positive at a public hospital, they chose to go to pharmacies outside the public health system, or to access services through Jamaica AIDS Support for Life (JASL) or the Red Cross. Even seeing private physicians can pose problems. David M., a psychologist who volunteers with JASL, told Human Rights Watch:

There are some physicians [that] are wary of LGBT in their [private] practice … my clients have told me this. They [doctors] have no problem seeing them outside of their private practice, [but] they fear that LGBT coming to their practice might turn normal patients away and would rather see them in the public health system or at JASL. The discrimination has to be considered as fear of association.[97]

Genie O., a 28-year-old gay man from Westmoreland, told Human Rights Watch that he had gone for an HIV test at St. James Health Department “Type V” clinic, but was afraid to disclose his sexual orientation to health workers, whom he saw discussing clients’ confidential information:

Most men who are MSM go to Type V. There is a section that does the HIV test. As soon as you go there you are assumed to be gay…. If you are effeminate there are whispers and shuffling [away from people who are perceived to be gay].

The information is easily accessible and the staff talk, and they would say, “I didn’t know that person had AIDS.” The staff would discuss it in earshot. There is no confidentiality.[98]

Employment Discrimination

The 2004 Staff Orders for the Public Service, which bans discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation in civil service, is the only legal protection in Jamaica against employment discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity.[99] There is no equivalent protection for workers in the private sector.

LGBT people in Jamaica face discrimination when seeking and maintaining employment. We interviewed five LGBT people who had lost employment primarily because of their assumed sexuality. Others said they move regularly to protect themselves from violence; the constant movement of homes, or homelessness, also hampers their ability to find and hold a job.

Charles B. told Human Rights Watch he was fired because of his sexuality:

In 2008 there was rumor going around that I was gay and that the supervisor caught me in the bushes with a guy. The rumors escalated at work. I was later fired based on the fact that I was gay. My manager said that I was bringing the organization disrepute. That incident caused me to become homeless, and I have been living on the street for about three years now.[100]

Devon O. had a job as a security guard at a large business in Montego Bay. He told Human Rights Watch that in December 2010 his manager called him into a meeting and told him he had to look for a new job. “I heard that you are gay, that you are a battyman,” Devon O. recalled him saying. “We don’t tolerate these things in the company.”[101]

Marsha J., a single bisexual mother living in Ocho Rios, told Human Rights Watch that her sister, who is also bisexual, argued with a colleague in February 2012 because of her sexual orientation. Marsha, who witnessed the argument, recalled: “They were up in my sister’s face. They eventually suspended her from work.”

Marsha J. said the father of her baby also lost his job because of his perceived sexual orientation. “People are saying that he is a battyman,” she said.[102]

None of the individuals we interviewed had attempted to file a complaint or seek redress for wrongful dismissal, stating that there is no legal protection for them.

Housing Discrimination

Eviction and homelessness shape the lives of many LGBT Jamaicans. Human Rights Watch interviewed LGBT people who had been forced to move: kicked out of their homes by family members, driven from home by community members who threatened to kill them, and in some cases violently attacked and forced to flee. Some had moved many times, often with short notice.

Winnie R. and Nadine G. were evicted by a homophobic landlord in 2011. Nadine recounted:

A week after Winnie R. began living with me, I began to experience problems with my landlord. Initially, he would make negative comments when he saw Winnie, such as that she was “too harsh” in appearance, and would complain whenever Winnie parked her car at the house. As time passed, my landlord only became increasingly more hostile, and on multiple occasions he called us “abominations”; told us he did not want “this nasty thing” in his house; and said that he wanted us to leave, claiming that we would bring destruction to his house.

Around January 2011, the landlord called the police, telling them that Winnie and Nadine were abusing their sons. She said:

We were visited the following day by a “child care officer,” who confirmed that the allegations were false after speaking with the children. When we mentioned the problems we faced from the landlord, [the police] said that we should find a new place to live.

Two days later, the landlord padlocked the house.

On the day we moved out, our landlord began yelling outside that we were lesbians, that this was why we were leaving, that we had been there too long, that we were bringing destruction to his house and business.[103]

Errol S. and his boyfriend had to abandon their home in 2011 due to threats from neighbors. On one occasion he was confronted by neighbors as he walked down the street in his Old Harbour neighborhood. He said:

As I turned the corner, one of the guys said, “Me no want a battyman go by my shop.” He got up and started to flick his knife open. When I ignored him, he said, “You a battyman?” I started to back away and then I just turned and go back by my avenue. The guy yelled, “Leave the community within 24 hours, or else.”[104]

The next day, members of the community stoned his house for 20 to 30 minutes. “[I] heard them yelling, ‘Battyman them there so. Come out of the community,’” Errol said. He left a week later.

Anne, the transgender woman whose experiences with violence are described in Section III, had to flee her home in St. Mary in 2007:

They surrounded the house—I saw the crowd from 5 p.m. until I left there from 9 to 10 p.m. I called the police, told them that there was a crowd of people at my gate and around the back. The police came with two jeeps. The crowd would say “Jesus God, Jesus God” as they wanted to see what I looked like. [The police] asked me where I could go, and I said I have a sister that lives in the district. I stayed with her for two months before moving again.[105]

Homelessness

According to Ivan Cruickshank of Caribbean Vulnerable Communities, LGBT-identified youth comprise up to 40 percent of the nation’s homeless youth population.[106] These young men tend to fall through the cracks, as neither government services nor civil society organizations have developed services that can fully address their health or psychosocial needs.[107] Both in New Kingston and Montego Bay, police evict them from their squatted or makeshift homes.[108] Living at the margins of Jamaican society, they are vulnerable to rape, violence, and disease.

Human Rights Watch found that many young LGBT people were almost entirely uprooted, having been expelled by their families and forced to move on from each place that briefly became home.

We interviewed 13 gay, homeless youth, including 3 boys under 18 that had been kicked out of their homes in Kingston and Montego Bay. At the time, they were squatting at the former offices of J-FLAG and Jamaican AIDS Support for Life, located in New Kingston. They have few skills and limited access to resources or social support and face constant threat of attacks from both private citizens and the police.

Cutie G., 18, had been living on the streets for four years after leaving home and school due to constant teasing, bullying, and attacks. He lived with grandparents until they chased him away, and was living mostly in a sewer when we interviewed him. Cutie G. survives by selling sex in New Kingston. “Sometime we go to a hotel, their houses, on the street,” he said. “If I don’t go on the road to sell my body, I don’t eat.”

Carlton J., 25, said he also began to live on the streets of Kingston after his mother and his aunt cursed him because of his sexuality, which he revealed to them when he was 18:

[My mother] wanted me to be straight, go to church, all that stuff. [She said] “If you can’t change you must leave,” and eventually she kicked me out of the house. I left to stay with friends in Mandeville and then I eventually made it to Kingston to live on the streets.[109]

In June 30, 2012, Carlton said a car slammed into him on a New Kingston street and dragged him down the road for about a minute as the driver yelled “homosexuals.” Police from New Kingston picked him up and took him to the hospital, but Carlton did not file a complaint and police did not investigate the incident. After a week in the hospital, Carlton returned to his mother’s house, but fled to the streets again after seven months because of constant arguments with her over his sexual orientation. He now does sex work to survive.[110]

Scars that Carlton J. says he sustained as a result of being knocked over and dragged by a car in June 2012.[111]

©Rhon Reynolds

Wayne P. has been living on the streets of Kingston since the age of 16. He told Human Rights Watch that he was kicked out of his home in March 2009 after his mother and aunt found out about his sexual orientation. He went to stay with an uncle, who then forced him into sex: He told me that if I didn’t have sex with him I would have to leave the house.[112] After giving in to his uncle’s demands twice, Wayne left his uncle’s house in May 2009 and moved to New Kingston because, he explained, “A friend told me that is where the gays live.” He started to beg and do sex work to survive:

I had no money. I had to hustle, beg many people, sell sex … on the street, in a car or on the road or in an apartment. I always used condoms, [but] not always lubricant.[113]

Kevin G., age 17, was raised from age 6 to 15 in a children’s home in St. Elizabeth, where he said he was regularly sexually abused by older boys. When he was 15, he said, staff at the children’s home “run me off. They say that I’m acting like a little girl. ‘This is not a girls’ home, it’s a boys’ home.’ They strike me with a bottle.” He now lives on the streets.[114]

Non-governmental organizations such as JASL and J-FLAG have made attempts at developing programs to address the needs of homeless gay and transgender young people. A Safe House pilot project operated briefly in 2009, supported by the Jamaican Red Cross and the Ministry of Health and hosting 11 young gay men and one woman, but it subsequently closed.[115]

Since 2013, New Kingston MP Julian Robinson and the police have organized a series of town hall meetings, in which LGBT organizations have participated, focused on addressing the needs of homeless gay youth. Participants have called for a project to be established that would provide homeless gay youth with shelter, counseling, and food.[116] The project had failed to materialize at time of writing.

In April 2014 Minister of Youth and Culture Lisa Hanna announced that her ministry is developing new services to address the challenges, concerns, and needs of the different types of youth the ministry serves, including LGBT youth.[117]

VI. Government and Police Response