Summary

After the Moroccan boxer Zakaria Moumni won the light-contact boxing world championship in 1999, he repeatedly contacted Moroccan authorities to claim a job in the Youth and Sports Ministry to which he believed he was entitled by law as a Moroccan world title-winner.

When he was rebuffed Moumni frequently made his case before Moroccan and international media. On September 27, 2010, police stopped him at Rabat airport upon his return from a trip to Paris. They accused him of “harming sacred values,” a term often used to refer to the monarchy and the person of the king, and detained him.

According to Moumni’s account security officials then drove him to an unknown location where they handcuffed, stripped, and blindfolded him and subjected him to torture. They beat him, hung him by his arms, applied electric shocks, and deprived him of sleep and food over a three-day period, Moumni said.

On the morning of September 30, Moumni says police put his clothes back on, walked him up a set of metal stairs, and put him in a car. They drove him to the police station in the second district of Rabat, where they removed his blindfold. He found himself in a room with 13 men, most of them in plainclothes. They told him he would have to sign some documents in order to get back his personal belongings. He told Human Rights Watch:

They put documents in front of me, but they were covering the top part of the page. I said I wanted to read what I was signing. They said, “Just sign here, you’ll get your stuff back, and you’ll be free to go.”

Moumni said the security officials drove him straight from the police station to court, where his trial took place in the absence of defense lawyers, witnesses or spectators. Four days later on October 4, Moumni, sitting in jail, learned that the court had found him guilty of fraud and sentenced him to three years in prison. The conviction was based mainly on a signed statement that Moumni insists he was forced to sign without reading it.

Morocco’s new Constitution, approved by voters in July 2011, marked a major step both in the protection of fair-trial rights for defendants and in the promotion of judicial independence and access to justice. The judicial provisions of the Constitution were the culmination of an official campaign to reform Morocco’s justice system, which aimed, in the words of King Mohammed VI, to "make justice more trustworthy, credible, effective, and equitable, because it serves as a strong shield to protect the rule of law."

However, enduring flaws in the judicial system indicate that reforming the judiciary will be an uphill struggle. This report offers analysis of six politically sensitive cases adjudicated between 2008 and 2013, including the case of Zakaria Moumni, where the courts violated the right of defendants to a fair trial.

The six cases, involving a total of 84 defendants of whom 81 served time in prison, highlight two major weaknesses. First, in five of the six cases, the courts handed down convictions based largely on confessions that the police obtained from defendants and that those defendants contested in court. The courts did not make a proper effort to determine if these confessions were obtained through torture of the defendants or other illegal methods. The courts also based their convictions on incriminating written statements by witnesses or complainants without requiring those persons to provide their testimony in court where the defendants or their representatives could challenge them.

Second, in two of the six cases, there was a clear denial to the 32 defendants, especially to the 25 of them who had spent at least 18 months in pretrial detention, of timely access to a trial or court hearing once they had been charged or been subjected to prejudicial administrative actions.

It is not clear whether the failures of the Moroccan judicial system in these cases reflect a lack of judicial independence—pressure or interference by the executive branch or another party—or simply poor-quality justice, where judges do not show due diligence in trying to discern the truth by examining all pertinent evidence and discounting statements that may have been obtained through impermissible means. Lack of independence and due diligence may both have played a role. Whatever the reasons, the result is clear: unfair convictions for the defendants.

In five trials, we examined the court’s readiness to admit incriminatory evidence that the defendants had contested as false, notably the defendants’ “confessions” made while in police custody. These cases include the trials of:

- 25 Sahrawis in 2013 for their alleged role in the deaths of police during deadly violence that erupted in Western Sahara in 2010;

- labor and human rights activist Seddik Kebbouri and nine co-defendants for their role in disturbances that erupted in the city of Bouarfa in 2011;

- boxer Zakaria Moumni on charges of fraud in 2010;

- 35 defendants arrested in 2008 and accused of belonging to a terrorist cell, known as the “Belliraj” case, after the family name of one of the leading defendants;

- the trial in 2012 of six protesters from the February 20 youth movement for assaulting police officers while refusing to leave an “illegal” gathering.

In all these trials, the court convicted and imprisoned the defendants primarily on the basis of their contested confessions. In so doing, they displayed an apparent lack of diligence in failing to conduct serious investigations into defendants’ allegations of torture or ill-treatment during interrogation by police while at the same time admitting the defendants’ police statements into evidence.

In the Belliraj case, for example, the court justified dismissing torture allegations on the grounds that the defendants had not raised them at their first appearance in court. On the one hand, some defendants had in fact informed the court early on that the police had mistreated them under interrogation, without triggering any kind of inquiry. But even where they had not done so, the court should not dismiss torture claims summarily simply because the defendant was “late” in making them.

While the court is entitled to consider the timing of a defendant’s introduction of a torture claim as relevant in judging its credibility, it should also recognize that there are many reasons why a defendant may introduce a torture claim late in the trial other than a desire to escape punishment.

The courts also failed to allow the defense sufficient opportunity to challenge other incriminating evidence and deprived defendants of their right to call witnesses whose testimony might shed light on the facts in dispute.

In one respect, Morocco’s laws on evidence contribute to the lack of diligence by the courts in scrutinizing allegations of torture or ill-treatment. Article 290 of the Code of Penal Procedure instructs the court to presume that statements prepared by the police are credible, in cases where the defendant faces less than five years in prison.[1] Courts often quote this rule in written verdicts where they decide to convict defendants based on incriminating statements made to police, even if the defendants allege their statements were coerced. Article 290 should be revised so that the evidentiary standard is the same as the one that applies to more serious offenses, which requires the court to treat a police statement like any other piece of evidence, with no inference made about its credibility.

In two of the six cases examined in this report, courts unduly delayed bringing defendants to trial or concluding their trial, prejudicing defendants and denying them their right under international law to a “trial within a reasonable time,” a right newly enshrined in article 120 of Morocco’s constitution.

In many jurisdictions around the world, including Morocco, delays occur in the justice system due, for example, to backlogged courts, defense requests to postpone hearings, or the necessities of the judicial process. In these two cases, however, these factors do not seem to be responsible for the delay.

In both cases, the defendants include advocates of independence for Western Sahara. Authorities consider advocates of Sahrawi independence to be “separatists” who act in violation of Morocco’s laws that prohibit “attacks on territorial integrity.”

In the first of the two cases, 21 of 25 defendants spent 26 months in pretrial detention before going on trial for their alleged role in the violent clashes that occurred in Gdeim Izik, Western Sahara, in November 2010 in which 11 security force members were killed.

In the second of these two cases, the government has accused seven activists of undermining Morocco’s internal security while visiting the Polisario-run refugee camps near Tindouf, Algeria, by collecting funds there to stir unrest and subversion in Western Sahara; this is an offense punishable by five years in prison. Three of the seven defendants spent a year and-a-half in pre-trial detention before the judge released them. Since their release, more than two years have passed without the trial resuming or the case being dropped. According to a government reply to Human Rights Watch the court is conducting a “complementary investigation” that is continuing.

This apparent inconsistency in the court’s approach to the case—first treating it as serious enough to detain three of the defendants 18 months pretrial, and then freeing them without resuming the trial during two years—may suggest that political concerns guided the court’s handling of the case.

The conclusions from our analysis of the six cases examined here lead to two key recommendations. First, courts should diligently examine any claims made by defendants that the police obtained their self-incriminating statements by force or coercion and exclude statements so obtained, except as evidence against those responsible for abusing the defendant. Secondly, courts should end the practice of unduly prolonged pretrial detention of defendants and conduct trials with reasonable promptness, all the more promptly when the defendants are being provisionally detained. Detailed recommendations follow.

Recommendations

To the Moroccan Government

- Take steps to prevent torture and ill-treatment and to verify and ensure that incriminatory statements obtained through the use of torture or ill-treatment are not admitted into evidence, as required by article 293 of the Code of Penal Procedure.

- Ensure that all persons placed in garde à vue (pre-arraignment) detention are informed immediately of their right to a lawyer, and that they have, if they so request, prompt access to a lawyer, access that should include the possibility of being visited while still in garde à vue by the lawyer for a confidential consultation; in accordance with the U.N. Basic Principles on the Role of Lawyers.

- Amend the Code of Penal Procedure to indicate that where there is an allegation of torture or ill treatment, the burden of proof lies on the prosecution to prove that any confession made has not been obtained by unlawful means, pursuant to the recommendation made by the U.N. special rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment in his February 28, 2013, report on Morocco.

- Ensure that prosecutors, investigating judges, and trial judges give defendants a thorough opportunity to: raise at any point in the investigation and trial any ill-treatment they may have experienced while in police custody; read carefully their police statement and challenge any alleged inaccuracies in it; and consult with a lawyer prior to their first appearance before a prosecutor or judge.

- Ensure that prosecutors, investigating judges and trial judges reflect in the minutes of the hearing and in the court’s written judgment any statements made by defendants before them about ill-treatment or inaccuracies in their police statements.

- Take steps to eliminate torture and coercion during the preparation of reports prepared by the judicial police. Possible steps to ensure the voluntariness of such statements include videotaping police interrogations; requiring the interrogating official to appear in court for cross-examination; and repealing article 290, as described below.

- Implement the recommendation that the U.N. Special Rapporteur on Torture made based on his visit to Morocco in September 2012 “to further develop the forensic capacity of the prosecution and judiciary and implement the right to complain and to ensure that defendants who first appear before them have a fair opportunity to raise allegations of torture or ill-treatment they may have experienced by the police or intelligence services.”

- Require that judges and prosecutors receive instruction regarding their obligation to investigate rigorously torture allegations regardless of when during a trial the defense raises them and to document their investigation efforts in writing. Such training should include awareness-raising about the reasons, other than a desire to escape punishment, why a defendant may raise torture or ill-treatment at a later phase of the trial, even if earlier in the judicial process the defendant had confirmed the veracity of his or her written statement as it was prepared by the police.

- Educate judges on their obligation to assess the credibility of allegations of ill-treatment even in the absence of physical evidence of torture, and the means of making such an assessment, based on international norms, as set out in the Manual on the Effective Investigation and Documentation of Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman, or Degrading Treatment of Punishment (“the Istanbul Protocol”).

- Educate judges on their obligation, in upholding the “equality of arms” to afford to the prosecution and defense, the opportunity to summon witnesses for questioning if they are brought to the court’s attention and if they appear relevant to determining the truth of the charges against the defendants and, in particular, the truth of incriminatory police statements when these are challenged by the defense.

- To prevent prejudice to defendants caused by inordinate and unreasonable delays in the completion of trials, implement laws that require trials to be completed without undue delay, in keeping with article 120 of the 2011 constitution, which states, “Everyone has the right to a fair trial and to a judgment delivered within a reasonable amount of time.”

- Amend the Code of Penal Procedure to require regular and substantive judicial review of all cases of pre-trial detention, with an increasing burden being placed on the state authorities to justify pre-trial detention the longer the trial is delayed and the person is detained, by showing all possible steps are being taken to ensure a trial as speedily as possible. If the burden is not met, the court should order the detainee’s release.

- Reform domestic law to restrict the jurisdiction of military courts to purely military offenses. Under Moroccan law, the jurisdiction of military courts is extended to also cover crimes committed by civilians against members of the security forces. This broad jurisdiction contravenes a basic norm of international law, which requires trying civilians in civil courts. In addition, military court verdicts are not subject to appeal except to the Court of Cassation, thereby violating the internationally recognized right of defendants to an appeal not only on formal but also on substantive grounds.

- Enact a law that gives force to article 133 of the 2011 constitution, which gives defendants the right to petition the new constitutional court to review the constitutionality of a law being applied in their case.

- Strengthen the fair-trial rights of defendants to ensure an “equality of arms” between the prosecution and the defense by revising Code of Penal Procedure article 290, which gives statements prepared by police inherent credibility in cases involving offenses that incur sentences of less than five years in prison. This law places the burden of proof on the defendant to show that the statement prepared by the police is false. The law should be revised to eliminate this unfair burden, so that a police statement would be treated the same as all other evidence presented in court with no inference made about its credibility.

With respect to the Gdeim Izik case, in which 21 of the 25 defendants are in prison, and the Belliraj case, in which 17 of the 35 defendants are in prison, the Moroccan authorities should:

- Free the defendants still in prison or grant them a new and fair trial. For the Gdeim Izik defendants, any retrials should take place before a civilian court.

- If the cases are retried, the presumption should be that all defendants will be at liberty until their trial. Any individual defendant the prosecuting authorities wish to detain should be entitled to a prompt hearing before a judge to rule on the legality of their detention, with the presumption being for liberty. A judicial decision to detain the defendant pending trial should be based on valid grounds, such as that the defendant is dangerous or is likely to repeat his offenses, tamper with evidence, or take flight;

- When retrying the defendants, the court should examine their allegations of torture and ensure, in compliance with international and Moroccan law, that no statement obtained through violence or coercion is admitted into evidence. The court should conduct investigations even if the physical traces of possible torture may have faded. The investigations should adhere to international standards for investigation of individual complaints of torture, notably those found in the Manual on the Effective Investigation and Documentation of Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman, or Degrading Treatment of Punishment (“the Istanbul Protocol”);

If the court decides to admit into evidence a police statement that the defendant claims was extracted under torture, it should explain in its written judgment why it decided the claims of torture or improper coercion were not credible.

To Governments and Institutions that Provide Assistance to Morocco

Under the rubric of judicial reform and rule of law assistance programs, encourage Morocco to implement the recommendations enumerated above, notably those designed to prompt judges to:

- scrutinize more critically the evidentiary value of statements prepared by the police when defendants challenge their contents;

- devise and follow methods of probing more thoroughly claims of torture or other ill-treatment regardless of when they are raised during the course of the proceedings;

- impose legal limits on the duration of pretrial detention not only during the phase of the judicial investigation but also when a trial fails to get under way or proceed to completion within a reasonable period of time, and to ensure regular and substantive judicial review of pretrial detention orders.

Methodology

This report is based on the study of selected trials conducted between 2008 and 2013. Human Rights Watch observers attended some sessions of four of them. We also examined written verdicts and case files and interviewed defense lawyers, officials of the Ministry of Justice and Freedoms, and other pertinent sources of information, including the defendants in some cases. We also reflect in the report, and reprint in Appendix I, statements provided to us by the government concerning these cases. However, for the most recent of the six cases, the one involving the February 20th Youth Movement protesters, Human Rights Watch did not formally request official comment and received none.

Human Rights Watch wrote to Minister of Justice Mustapha Ramid on January 12, 2012, informing him of our work on fair trials and requesting a meeting. We did not receive a reply. However, representatives of the Interministerial Delegation for Human Rights received us in Rabat on January 23, 2012.

While representatives of Human Rights Watch were in Morocco in mid-November 2012, Minister Ramid informed us that he could receive them on November 19. Because its representatives would no longer be in Morocco on that date, Human Rights Watch wrote a letter proposing to return in December if he was available to meet and also outlining the interim conclusions of this report. We received no reply.

Human Rights Watch trial observers encountered no obstacles in entering courtrooms and observing trials, with four exceptions relating to a single trial: on November 20, 2012, December 18, 2012, and January 8, 2013, police denied our representative entry to the Rabat Criminal Court of First Instance, where he had identified himself to them as Human Rights Watch and explained that he had come to observe the trial of Camara Laye.[2] Each time, the police told him he needed permission from the Ministry of Justice and Freedoms. Our representative managed to enter on the second occasion when defense lawyers escorted him inside. On May 14, 2013, security offices at the entry to the court denied entry to two representatives of Human Rights Watch who had come to hear the verdict in the Laye case.

With regard to the Gdeim Izik trial before the Rabat Military Court, our observer attended the sessions on February 1, 9, 10, 13 and 14, 2013, but not those on February 8, 11, 12, 15 and 16. For the dates when he was absent, the observer obtained an account of the proceedings from defense lawyers and other trial observers. Human Rights Watch interviewed several members of the defense team about the case, including Noureddine Dhalil in Casablanca on March 19, 2012, Mohamed Fadhel Leili, Mohamed Boukhaled, Mohamed Lahbib Rguibi, and Lahmad Bazaid in El-Ayoun on June 23, 2012, Mohamed Lahbib Rguibi on September 13, 2012, in Rabat, and Mohamed Messaoudi in Rabat during February 2013.

Background

Influential forces are pushing in opposite directions on Morocco’s justice system. In cases with a political coloring, courts continue to deny defendants the right to a fair trial by convicting them on the basis of confessions that they say the police extracted under torture or coercion, without the court making an earnest effort to probe their claims. This practice reinforces an impression that the courts serve as an extension of the state’s repressive security apparatus.

But there is also a logic propelling Morocco to accelerate the pace of reform. Its leaders wish Morocco to be recognized, both domestically and internationally, as a regional model on human rights. When pro-reform street protests erupted in Morocco in February 2011, the authorities responded not by repressing them blindly but by promising a new constitution and calling early elections. While resolutely and successfully opposing proposals at the United Nations Security Council to give a human rights mandate to the peacekeeping mission in the contested Western Sahara, Morocco argues that it is on its own making great strides on human rights.

The official discourse on reform emphasizes the task of reforming the judiciary including by enhancing its independence. This has been a theme for several years in the public pronouncements of Morocco’s leaders, including King Mohammed VI. The 2011 constitution contains a remarkable number of provisions that, if implemented, would advance this objective.

A New Constitution

In July 2011, Moroccan voters approved into law a new constitution rich in affirmations of human rights, including some that did not figure in the previous constitution, promulgated in 1996. These affirmations must still be translated into laws and practices that curtail ongoing violations. The leap forward in rights language suggests, nonetheless, a willingness on the part of Morocco to set for itself a high standard by which its laws and practices are to be judged.

One of the realms in which the new constitution breaks new ground is in promoting judicial independence and the rights of persons before the courts. King Mohammed VI said that the constitutional provisions “stipulate legal guarantees of judicial independence and consecrate the judiciary as an independent power equal to those of the legislative and executive branches.”

The king said these provisions culminated a campaign to reform the judiciary, started in 2009. In a speech on August 20 of that year, he announced an "in-depth, comprehensive reform of the judicial system" to "make justice more trustworthy, credible, effective, and equitable, because it serves as a strong shield to protect the rule of law." He spoke of "moralizing justice and shielding it from corruption and abuse of authority," and of strengthening guarantees of judicial independence.[3]

The king has continued to emphasize the importance of judicial reform since then. On May 8, 2012, he inaugurated the High Commission of National Dialogue on Reforming the Judiciary, a 40-member body charged with leading a national debate that would result in a charter for overhauling the judiciary.[4] On July 30, 2012, a holiday commemorating his accession to the throne 13 years earlier, he declared:

Our starting point is that the rule of law is the source of all progress. This is why we put justice first among our reform projects. Now that the new constitution has placed judicial reform at the heart of its structures, the conditions are now in place to succeed in this major endeavor.[5]

Since its creation, the high commission, presided over by Minister of Justice and Liberties Mustapha Ramid, has convened a series of conferences in cities across the country on different facets of judicial reform. Ramid opened the eighth such conference, devoted to judicial independence, held in the city of Agadir on January 11-12, 2013. There he announced that a “national charter” on judicial reform would be ready by March 2013.[6] It had not been released publicly at the time this report went to print.

One reform that should be a priority is revising the laws to end to the trial of civilian defendants in military courts in peacetime. The National Council for Human Rights made this and other recommendations to King Mohammed VI in February 2013, citing both the constitution and Morocco’s international treaty obligations. On March 2, the king “welcomed” these recommendations.

Enduring Bad Practices

The push to guarantee defendants a fair trial requires a break with prevailing practices. Human Rights Watch and other international and Moroccan human rights organizations have documented tens of cases in the past decade where Moroccan courts convicted citizens due to unfair judicial proceedings. It is not possible to specify the number of “political prisoners” or the number of prisoners who were convicted unjustly. Beyond the handful of persons who are clearly in prison in violation of human rights because they were charged and convicted for their nonviolent speech or political activity, there are hundreds more defendants who were convicted of recognizably criminal offenses—such as drug-trafficking or serving a terrorist organization—but who claim that they are innocent of these charges and were convicted on the basis of flawed evidence. It is not feasible for us to assess how many, if any, of their claims, are true.

Others claim that they were prosecuted on criminal charges fabricated to retaliate against them for unrelated reasons having to do with their politics or whistle-blowing activities. To gauge the frequency of unjust convictions would require examining trials one-by-one and the evidentiary basis for the charges, an undertaking beyond the scope of this report. This report presents one persuasive example of charges that appear to have been fabricated to retaliate against a person for being outspoken toward the authorities: Zakaria Moumni, who was convicted of fraud apparently to punish him for lobbying the king and the royal palace to secure a government job he believed was his due.

In spite of the prohibition on torture and Morocco’s recognition of it, torture and mistreatment of criminal suspects remains a serious problem in Morocco. The torture and ill-treatment of suspects in custody and specifically under interrogation remains a problem in Morocco, as affirmed by the U.N. Special Rapporteur on Torture after his mission to Morocco in September 2012.[7] Human Rights Watch has interviewed numerous detainees and former detainees over the past decade who credibly described abuse to which security forces subjected them while in custody, including beatings, threats, denial of food and water, sleep deprivation, and other means that constitute torture or ill-treatment.[8]

Convictions based Largely on Contested Confessions

Seddik Kebbouri and Co-defendants

In this case, the fair trial concerns revolve around the conviction of defendants based on contested confessions and written reports prepared by the police, without the judges making a diligent effort to explore the defendant’s allegations of mistreatment or summoning witnesses who were relevant for addressing the prosecution’s evidence.

The case relates to protests in the desert town of Bouarfa, in the northeast of Morocco, on May 18, 2011. Seddik Kebbouri, a local activist, called on citizens to join in protests. Alongside citizens demonstrating peacefully, some protesters hurled stones, causing injuries and property damage. No one contests these facts. What is missing from the case file is any evidence showing that Kebbouri directly incited the violence, as the first instance court concluded.

Socio-economic protests like the one that engulfed Bouarfa on May 18, 2011, are increasingly commonplace in towns and cities across Morocco. Marches and open-ended sit-ins often end with forceful intervention by law enforcement agencies to disperse protesters, and not uncommonly with stone-throwing at the police and some property damage.[9] Following Bouarfa, such protests occurred in the coastal Safi in August 2011,[10] Taza in the Atlas Mountains in January-February 2012,[11] and Beni Bouayach and Imzouren in the Rif in March 2012.[12] In each case, authorities arrested, brought charges and obtained the conviction and imprisonment of protesters on such charges as holding unauthorized demonstrations, participating in “armed” gatherings, blocking traffic on public thoroughfares, disobeying or insulting the police, and causing property damage.

Seddik Kebbouri is active in the Democratic Confederation of Labor, the opposition Unified Socialist Party, and social-action committees, including one that protests against the high cost of living and the deterioration of public services. He also heads the local chapter of the Moroccan Human Rights Association (AMDH). Kebbouri was a co-organizer of a long-standing boycott by Bouarfa residents of their water bills, which they considered to be too high. Perhaps Bouarfa’s best-known social activist, Kebbouri often participates in dialogues and mediations between local authorities and protest groups, according to several residents we interviewed.[13]

For about two weeks in May 2011, a coalition of unemployed persons had been holding a sit-in across from the prefecture in Bouarfa. They had demanded, without success, to be received by a senior official. On May 18, relations grew more tense between the protesters and the police, who had repelled an effort by some of the protesters to gain entry to the prefecture. One of the unemployed demonstrators set himself on fire in protest. As his colleagues came to his assistance, the police moved to disperse the sit-in.

At this point, Kebbouri was at the school in Bouarfa where he works. Hearing the news of the self-immolation, he left the school and walked through the streets with a megaphone, urging citizens to march on the prefecture to show support for the protesters. The streets filled with people, and before long the police were chasing and clashing with youths. According to a statement provided later by authorities to Human Rights Watch (see Appendix I):

When the crowd reached approximately 600 persons, most of them minors, they headed to the prefecture in an attempt to storm it. Prevented by the security forces from doing so, they pelted security personnel and auxiliary forces with rocks and empty bottles, inflicting various degrees of injuries. They also threw stones at the Directorate for the Surveillance of National Territory [police headquarters] and attempted to storm it, causing material damage. They targeted the vehicles of security personnel and the Royal Gendarmerie, and uprooted traffic signs and burned tires. As a result of the attacks, 18 civil servants with the General Directorate of National Security, 14 members of the auxiliary forces, and six members of the Royal Gendarmerie were injured.

The police made some arrests that day, but released those they had arrested. However, a few days later, the police arrested nine youths; the Bouarfa Court of First Instance charged them on May 26, 2011. (The court dropped charges against one of the nine, a minor.)

Seddik Kebbouri, May 11, 2013. Kebbouri and nine other men served eight months in prison in connection with a demonstration in Bouarfa. ©2013 Eric Goldstein/Human Rights Watch

Kebbouri attended the youths’ May 26 hearing and while there advised their families on how to mobilize pressure for their release, according to relatives of the detained youths.[14] The case file contains a report prepared by a police officer stating that on May 26, Kebbouri was in court “inciting” the families to protest their sons’ detention.

Police arrested Kebbouri as he emerged from the courthouse. They arrested another labor activist, Mahjoub Chennou, elsewhere in Bouarfa that day. The prosecutor added Kebbouri and Chennou, who are both in their forties, to the same case as the youths, initially charging them all with the same offenses related to the violence that occurred on May 18.

It appears from the case file that the main evidence used by the court to convict the defendants consists of the statements purportedly given by the youths while in police custody and a written report filed by a police agent describing the events of May 18.

While held by the police, Kebbouri’s young co-defendants all signed statements prepared by police, in which they say they heard Kebbouri on the streets urging citizens to march on the prefecture; five of these state also that Kebbouri had announced that the man who had set himself on fire had died. (In fact, the man survived with injuries that were not grave.) However, none of the defendants’ statements implicated Kebbouri in committing or urging acts of violence.

On June 16, 2011, the Figuig Court of First Instance in Bouarfa convicted all ten men.[15] It found the eight younger men guilty of violence against public officials, destruction of private and public property, possession of weapons, insulting on-duty public officials, participating in an unauthorized public gathering, and disobeying law enforcement agents. The eight young men are Mohamed Negbaoui, Jamal Ati, Abdessamad Karboub, Yassine Balit, Abdelali Kdida, Abdelkader Qaza, Abdelaziz Boudabia, and Brahim Mqadmi.

The court also convicted Kebbouri and Chennou of participation in an unauthorized public gathering, disobeying security forces, and insulting on-duty public officials – that is, the same charges as their young co-defendants, excluding those charges involving violence, weapons, and property damage. The court sentenced all ten to pay fines and to serve prison terms of between 30 and 36 months. The sentence for Kebbouri and Chennou was 30 months.

On July 26, 2011, the Oujda Appeals Court upheld all of the verdicts but dropped the charge of insulting on-duty public officials. It reduced the original sentences to two years for Kebbouri and Chennou, and to between 16 and 18 months for the youths.[16]

Those who demonstrated that day in the streets did so without first notifying authorities, as the Law on Public Gatherings would require. However, more than one person in Bouarfa explained to us that notifying the local authorities in advance would have been pointless since they never would have permitted it. Moreover, this demonstration was not planned in advance but rather, erupted in response to that day’s events.

The first-degree court wrote in its judgment that Kebbouri and Chennou had incited the youths to resist the police and to force their way into the prefecture. The government wrote to Human Rights Watch:

[T]he court, in delivering its verdict, was convinced of the flagrante delicto nature of the case and the seriousness of the acts, seen in the rioting and in the defendants’ pelting of security forces with stones and glass bottles at the urging of Seddik Kebbouri and Mahjoub Chennou. The former used a megaphone to assemble more than 600 persons, most of them minors, who headed toward the prefecture office where the security forces confronted them, leading to material damage to vehicles, the destruction of state property, and the injury of several members of the security forces with wounds of varying degrees. They confessed to these acts before the judicial police and the Royal Prosecutor, and their recantation before the court was supported by no material evidence.[17]

On February 4, 2012, King Mohammed VI issued a pardon that included the ten defendants in this case. While the men are now out of prison, this does not alter the unfairness of the proceedings that led to their eight months of incarceration.[18]

The young co-defendants, as soon as they appeared before the prosecutor on May 26, 2011, repudiated the statements attributed to them by the police. The written ruling of the court states that before the prosecutor, the eight defendants said they saw persons throwing stones but denied that they had participated in any acts of violence. Contrary to their police statements, some also denied that Kebbouri had incited them to participate, according to defense lawyer Abdelouahid Benaïssa.[19] Some even denied having taken part in the protests at all.[20] Some told the prosecutor that the police had slapped and threatened them into signing their statements, Benaïssa and Kebbouri told Human Rights Watch.[21] However, these claims of being slapped and threatened do not appear in the official record of that hearing or in the part of the court judgment that summarizes the hearing before the prosecutor.[22]

According to defense lawyer Benaïssa, the prosecutor did not investigate whether the defendants had in fact been mistreated. Benaïssa said later that he did not demand a medical examination of the defendants because he detected no physical signs of mistreatment on them; an absence that would be consistent with mistreatment limited to slaps and threats.[23]

At trial, six of the youths told the judge that the police had either slapped or threatened them to compel their signatures, as the written verdict notes. Some stated that they had not even read their statements before signing. The judge allowed the defendants to make these claims on the stand but did not respond to them and in his written judgment shows that he considered their confessions valid and their recantations not credible.

Kebbouri at trial denied that he had incited or perpetrated acts of violence. He also denied that his appeal to fellow citizens included his announcing that a youth had died from self-immolation. He stated that his activities that day were limited to his usual peaceful activism as a member of the Moroccan Association for Human Rights and the Democratic Confederation of Labor.

Kebbouri’s statement at trial varies from his police statement in the case file. It also varies, he said, from the police statement he read and signed:

After the police finished questioning me, they presented me with a written statement. I reviewed it, found it accurate, and signed it. At trial, I was shocked to find that my statement had been altered to contain things I had never said. I told this to the court.[24]

As an example, in his police statement presented to court, Kebbouri confesses to having announced the death of the youth who immolated himself, a piece of news that was false and could presumably incite public anger. Kebbouri told the court that he had neither announced this on May 18 nor confessed to the police that he had done so.

The case file included videos showing Kebbouri in the streets that day, addressing his fellow citizens. In video clips that Human Rights Watch viewed, posted on YouTube by unknown persons, Kebbouri does not incite others to violence. It is not known if these clips are the same as the ones in the case file.

Besides the defendants’ police statements, the other pieces of evidence incriminating Kebbouri were reports prepared by a police officer stating that he had heard Kebbouri urging citizens not only to join a march but also to force their way into the prefecture. No other evidence in the case file supports this second allegation by the officer. The prosecution also introduced as evidence knives and slingshots purportedly seized in relation to the May 18 disturbances, but demonstrated no link between this material evidence and the defendants, according to the defendants’ lawyers Abdelouahid Benaïssa and Omar Ben Ali.[25]

The case file contains a written statement signed by a police officer who names the young defendants and says they “were seen” throwing stones at the police. However, the statement does not specify who witnessed them or how the police witnesses determined the identity of the stone-throwers.

The lawyers told Human Rights Watch that nothing links these defendants to the violence that occurred that day other than the defendants’ own written statements before the police, which they repudiated, and this written statement by the police officer.

The defense asked the court to summon police officers to answer questions about what they saw and how they identified these defendants among all of those throwing rocks that afternoon. The judges in both the first-instance and appeals court denied this request, but did not provide a justification for this denial in their written judgments other than to say that the court already had all the elements needed to judge the matter.

The defense also asked the appeals court to summon witnesses who would apparently testify that Kebbouri had tried to restrain rather than incite the demonstrators to violence, lawyer Ben Ali told Human Rights Watch.[26] The appeals court also denied this request. Tracking the language of article 290 of the Code of Penal Procedure, it wrote, in upholding the convictions, “The content of the confession recorded in the records of the judicial police, if they are carried out in a proper way, is trustworthy unless proven otherwise.”[27]

Faced with confessions and repudiations of those confessions, the court could have summoned witnesses requested by the defendants whose testimony appeared relevant to determining the veracity of their confessions. Instead, the court treated the written statements prepared by the police as presumptively trustworthy, and declined to summon the witnesses requested by the defense and convicted all the defendants based on their “confessions” and the police reports in the file.

Champion Boxer Zakaria Moumni Imprisoned for Fraud

The evidence in this case suggests that after publicly complaining about the state authorities, Zakaria Moumni, a boxing champion, was arrested, tried and convicted of fraud within three days. Moumni was not a political or social activist but rather someone who campaigned publicly for his personal cause, which was to get the royal palace to give him a government post that he considered his due under the law.

The evidence used to convict Moumni consists of his own confession to the police, which he contends was obtained through torture following an illegal arrest and secret detention, and the written statements filed by two men who claimed that Moumni defrauded them by absconding with their money after promising to find them jobs in Europe.

The main violations of Moumni’s right to a fair trial relate to the court’s acceptance into evidence Moumni’s contested confession and the complainants’ written statements, even though they did not appear in court to testify until the third trial in the case.

The case proceeded with uncommon speed: the police placed Moumni in custody on a Monday, and by Thursday morning they had a confession and a signed declaration from him waiving his right to a lawyer; by that afternoon, his trial had taken place in the absence of a lawyer, witnesses, relatives, or acquaintances.

Because the charges against Moumni were considered minor offenses carrying a maximum prison sentence of five years or less, the presumption of the truthfulness of police statements under article 290 of the Code of Penal Procedure applied in his case.

When Moumni claimed his confession had been obtained through torture, the court did not investigate his allegations of torture. In Moumni’s account to Human Rights Watch of his experience, he said he raised at every opportunity before the court his claim of torture, trying each time to show the court the traces of it on his body, without ever receiving a medical examination or any kind of judicial probe.

Moreover, the court did not give Moumni the opportunity to adequately challenge the complainants’ written statements incriminating him. In the first and second of Moumni’s three trials, the court satisfied itself with the complainants’ written statements without requiring their appearance in court. It was only at Moumni’s second appeals trial, after he had spent 15 months behind bars and the court of cassation had quashed the first appeals verdict that the court required the complainants to appear in person and answer questions.

Another factor fueling suspicions about the handling of Moumni’s trial is the uncommon speed with which the case proceeded, as noted above, just three days from arrest to the completion of the trial. Such speed is highly unusual except, perhaps, in cases where the defendant pleads guilty from the outset and challenges neither the charges nor the procedures.[28]

Background to the Case

Zakaria Moumni won the light-contact boxing world championship in 1999. Since then he repeatedly contacted Moroccan authorities, including the palace, to claim a job in the Youth and Sports Ministry to which he believes he is entitled as a Moroccan world title-winner, by virtue of Royal Decree (dahir) No. 1194-66, dated March 9, 1967, and a later directive concerning its application. Moumni’s wife Taline Moumni told Human Rights Watch that in 2006 a high-level official in the royal court received Moumni but ultimately rebuffed his request for a post. Since then, she said, Moumni made various efforts to re-contact the palace, including by approaching Mohammed VI’s residence in Betz, France, on January 25, 2010, when he knew the king was visiting. He asked to be received but the guards turned him away.[29]

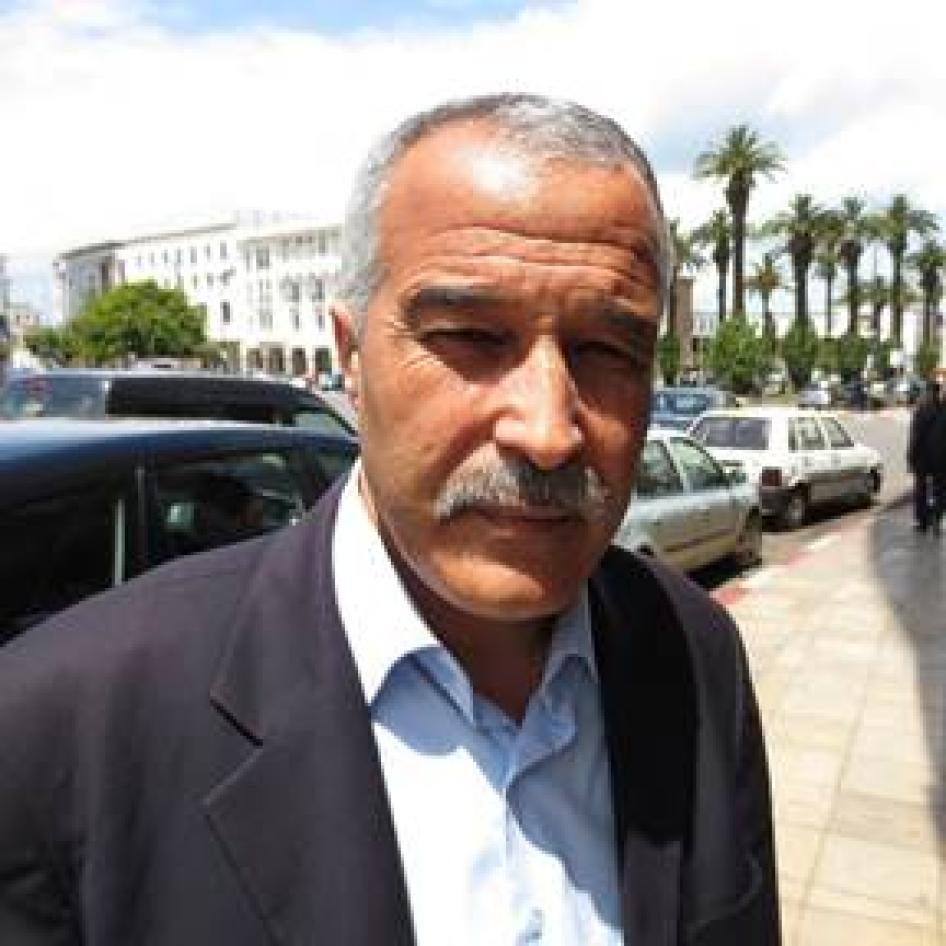

Zakaria Moumni, February 4, 2012, calling his wife minutes after leaving Sale Prison. He was pardoned after serving a year and-a-half on dubious charges of fraud. ©2013 Eric Goldstein/Human Rights Watch

Moumni frequently aired his grievance to the Moroccan and international media. For example, Al Jazeera television in 2006 featured Moumni criticizing the Youth and Sports Ministry and the Royal Federation of Light-Contact Boxing for blocking his access to a paid post.[30] An article on the French news site Bakchich.info dated June 29, 2010, recounted Moumni’s fruitless efforts to contact the palace.[31] The Moroccan weekly al-Ayam detailed Moumni’s grievances in its July 8, 2010 issue, including his alleged rebuff by the palace.[32]

The case file of Zakaria Moumni contains written complaints filed with the Rabat prosecutor, signed by Idriss Saâdi and Mustapha Ouchkatt, who said they reside in the city of Errachidia. Their complaints state that on January 22, 2010, they met in a Rabat café with Moumni, who took 14,000 dirhams (US$1,680) from each of them in exchange for his getting them jobs in Europe. They said that after giving him their money, Moumni became unreachable. The date on the complaints is difficult to read but appears to be the 26th – the day after Moumni sought to be received by the king and his entourage in France.

Moumni told Human Rights Watch that on February 12, 2010, police at Casablanca airport stopped him as he entered Morocco, telling him there was a warrant for him in connection with his having harmed "sacred values” (les sacralités), a term often used to refer to the monarchy and the person of the king. They released him after brief questioning, but stopped him briefly for questioning again when he left the country three days later. They said that they would try to close the matter but that there were no guarantees, he said. According to Moumni, the police did not ask him about the fraud complaint filed the previous month against him, according to the case file, and he remained ignorant of it until his trial seven months later. Moumni heard nothing more until September 27, 2010, when police detained him at Rabat airport upon his arrival from Paris.

From Arrest to the Completion of Trial

Moumni described the events starting with his arrest and concluding with his trial barely 72 hours later.

I landed on a flight from Paris at Rabat airport. When I got to passport control, the agent took my passport and said, “Follow me.” I followed him to a police office in the airport, where there were other police in uniform. I asked why I was there. A police agent looked at his computer and said, “Harming sacred values.” I looked on the screen and saw the same words. I called on my cellphone my relatives who were waiting for me at the airport to say I was inside with the police and would probably be out soon.

Then some guys in plainclothes came. They took my two cellphones, turned them off, searched me and my hand luggage, and handcuffed me behind my back. They walked me to an unmarked car parked on the tarmac—not in the parking lot but on the side of the terminal where the runways are. They put me in the middle in the back seat. There was a driver, a man seated next to him in front, and a man on each side of me in the back. They put a blindfold on me and asked me to put my face down. Then they put a jacket over my head and told me if I didn’t move everything would be OK.

We drove for about 45 minutes. I heard iron doors open. Then the car drove in and stopped. They took me out, slapping, punching, and insulting me. They unlocked my handcuffs, removed my shirt, and reattached them with my hands behind me. Then they removed my pants and underpants. I was completely naked, still blindfolded. They chained my feet and then started walking me forward, shouting at me to lower my head, then raise it, lower it, raise it, as I walked. I heard a door open. They sat me down.

There was more than one man in the room. One of them said, “OK, tell us your life.” I started telling them my story. When I got to the part about meeting with the king’s advisor, Mounir Majidi, they pounced on me and punched me. They put an iron bar under my feet and tightened the leg cuffs around my ankles, swung my legs in the air, hit my feet, and stomped on my chest, which was now on the ground. They kept insulting me and laughing. They used an iron bar to hit me on my shins, saying, “You’re a boxer, we’re going to break your legs.”[33] They said, “This place is a slaughterhouse for men. We’re going to make you into chopped meat and you’ll come out of this place in cans, and no one will know anything.”

After this, they ordered me to tell my story again. When I got to the part about being received by Majidi, they started beating me again. At one point, they yanked my legs up on a bar, held me upside down and twisted me. They call that “the helicopter.” They applied electric shocks to my chest and feet. I was still blindfolded so I couldn’t see it coming; all of a sudden, I just felt a jolt. At another point, they hung me by my arms so that my knees were on the ground.

This continued on and off for three days. They wouldn’t let me sleep. I was naked the whole time. If I slid off my chair, they poured water on me and propped me back up. At one point, they handcuffed my wrists to the chair so I wouldn’t fall over. The men worked in shifts; they all called one another “al-Haj” [Arabic for one who has performed the pilgrimage to Mecca]. I asked to phone my family, but they just laughed. They were laughing throughout. They gave me no food to eat, just water.

Moumni said that at no time did the police tell him the offenses he was suspected of committing. He said they did not try to get him to confess to anything or ask him about the alleged fraud for which he was eventually convicted. They just ordered him to tell his story over and over, he said.

Contrary to what the government claims (see below), and contrary to what Moroccan law requires, both Moumni and his wife, Taline Moumni, told Human Rights Watch that no one informed her or any other relative that Moumni had been taken into custody.[34] Moumni said he first alerted his family of his situation on the evening of September 30, only after arriving in Salé Prison, following his trial.

While Human Rights Watch has not investigated many cases involving defendants in Morocco who, like Moumni, faced common criminal charges, it has found a pattern by the authorities of failing to inform the family when plainclothes police have detained suspects being investigated for terrorism links. Family members commonly learn of their relative’s whereabouts only after he has signed a statement and been brought before a prosecutor or investigating judge.[35]

Moumni believes he was held was a secret detention facility in Témara, outside of Rabat. Authorities deny that any interrogation facility exists at that location, which is the headquarters of the Direction Générale de la Direction générale de la surveillance du territoire (DGST), a police agency. However, scores of terrorism suspects contend that they had been taken there in the years following the May 2003 suicide bombings in Casablanca. Their cases, and the extensive use of the secret detention facility in Témara, have been documented by human rights organizations.[36]

Moumni has no proof he was taken to Témara. He was blindfolded while being transported and heard no one mention the facility’s name; “Témara” appears nowhere in his case file. Moumni offers only circumstantial evidence: he estimated that the drive from the airport to the place of detention took 45 minutes, a time consistent with the journey from Rabat-Salé airport to Témara. In addition, he said he overheard one of the interrogators telling a colleague that he arrived late to his shift because his car had broken down, forcing him to leave it at Aswaq es-Salam (a large supermarket in the vicinity) and walk 20 minutes. He said he heard the same man saying he would return home on the 58 bus, a line that connects Témara and Rabat.

He told Human Rights Watch that on the morning of September 30, police dressed him, walked him up a set of metal stairs, and put him in a car. They drove him to the police station in the second district of Rabat, where they removed his blindfold and switched the handcuffs from behind his back to in front. He found himself in a room with 13 men, most of them in plainclothes. They told him he would have to sign some documents in order to get his personal belongings back.

They put documents in front of me, but they were covering the top part of the page. I said I wanted to read what I was signing. They said, “Just sign here, you’ll get your stuff back and be free to go.” When I insisted on reading it, they put the blindfold back on, stepped on my feet, and threatened to send me back to where I had just been. I still had the handcuffs on. At that point, I signed many things without knowing what they were.

It was only at a later date, said Moumni, that he found in his case file a confession to the police and a statement waiving his right to a lawyer, both of them signed by him and dated September 30.

After I signed, they put me in a police wagon and drove me to a courthouse in Rabat. They removed my blindfold again but kept the handcuffs on. In the courthouse, they brought me into a little office in the basement. Inside, there was a man seated at a desk, two policemen, and someone taking notes. The man behind the desk did not identify himself or ask my identity. I did not even know that he was the prosecutor.[37] He mentioned two names [those of the complainants] and asked me one question: Do I know these two individuals? I answered no. Then I reached down, with my handcuffs still on and lifted the cuffs of my jeans, and showed him my shins. There was blood there and on the pants. I said, “Look what they did to me.” He replied, “I don’t want to see it. Take him upstairs.” The man told me to sign a sheet of paper written up by the clerk. He explained, “It just says that you said that you do not know the two men.” I signed without reading. The whole session lasted two minutes.

Then they escorted me upstairs to the ground floor, where I found myself in a large courtroom. The prosecutor came up too, and stood at one side of the room. Besides the judge, the prosecutor, the police, and me, there was no one else in the room: no lawyers, no complainants, no other defendants, no spectators. The judge launched right in; he did not ask me for my personal details; he just asked if I knew the two complainants.[38]

I stopped and said, “All I know is that I landed on the 27th; I don’t even know what day it is today.” I lifted my pants cuff and said I’d been tortured and electric-shocked. The judge cut me off and said, “Take him away.”

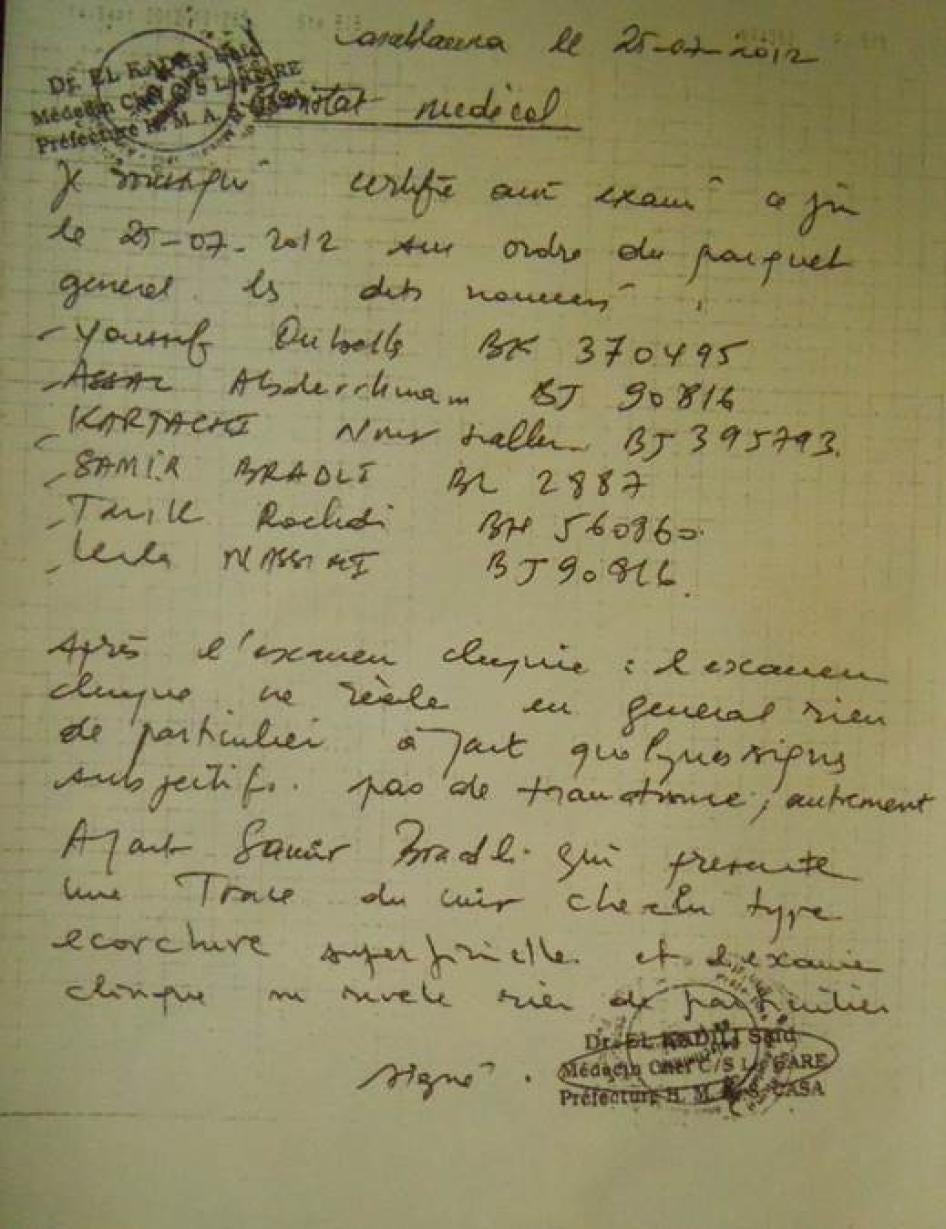

The minutes of the hearing before the prosecutor and the written judgment of the first-degree trial do not indicate that Moumni spoke in either setting of having been tortured. Neither complainant appeared at the September 30 trial, even though the case file contains written statements dated the day before, signed by lawyer Abdessamad Raji Senhaji, reaffirming their original complaints against Moumni.

Moumni recalled that after his brief trial:

The police escorted me out of the courtroom and to a cell where, for the first time, I found myself with other detainees. I waited another 15 minutes, and they put me in a police wagon. I asked where we going now, and they answered, “To Salé Prison.” When I got to the prison, I was able to borrow a phone and call my wife for the first time since being detained.

The next morning I saw a lawyer for the first time. [Attorney] Abderrahim Jamaï came to the prison. He asked me to tell him what had happened. He hadn’t yet seen the file. I told him what I had been through, but I still didn’t know what the case was about.

Jamaï later told Human Rights Watch that on this visit, he observed cuts and bruises on one of Moumni’s legs.[39] He also said that Moumni complained to him that his arms ached from being handcuffed for most of three days.

On October 4, the court pronounced Moumni guilty of fraud and sentenced him to three years in prison. The written verdict cites Moumni’s confession as the main evidence against him, adding, “Whereas what is contained in a statement prepared by the judicial police is to be considered trustworthy and can be discredited only through evidence of the contrary, according to article 290 of the Code of Penal Procedure, and this the defendant has failed to do.[40]

Moumni said he learned of the verdict only later; no one summoned him to attend its announcement.

Lawyer Jamaï filed a motion to appeal the verdict on October 6, 2010. He also petitioned the court to summon the two complainants and engaged a bailiff (huissier) to deliver the summons to the complainants. The bailiff looked for one of the complainants and wrote a statement saying that the complainant could not be found at the address he had provided. The appeals court postponed the trial twice because the complainants did not appear, Jamaï said.[41]

Suspicious of the complainants' statements, Jamaï also asked the court to summon the police agent who reportedly took their statements dated September 29, 2010, that were in the case file.

The appeals court eventually tried the case in a single session on January 13, 2011, with Judge Hachemi Slimani presiding. Judge Slimani did not summon the complainants or the police agent who took their complaint. As in the trial in first instance, the lawyer representing the complainants did not attend. It remained unclear why the complainants, who presumably would seek restitution of the money that Moumni had supposedly defrauded them of, never came to present their case against him. Moumni, however, with his lawyer present, this time spoke at length about being tortured and showed the court the scars on his shins.

The appeal court's written judgment noted Moumni's statement in court that he did not know his accusers, took no money from them, and was tortured in detention. It notes also that the defense asked the police officer to appear as a witness. It nevertheless reaffirmed the conviction, basing its verdict on Moumni’s confession to the police, which it deemed credible. However, it reduced Moumni's term to two and-a-half years.[42]

Moumni appealed to the Supreme Court to quash the verdict. On June 29, 2011, the court sent the case back to appeals court for a re-trial. The Supreme Court, ruling as the Court of Cassation, criticized the trial court for failing, without giving its reasons, to summon the police officer who took the complainants’ statements; and for failing to respond to the defense’s request to summon the complainants’ lawyer to court.”[43]

The third trial, scheduled to start in October 2011, was postponed while the court sought the appearance of the two complainants. On December 15, 2011, the trial took place before the Rabat Appeals Court, and Moumni’s accusers appeared in court for the first time. The complainants repeated the substance of their written complaints. Moumni stated once again that he was innocent of the charges, and that he had never heard of nor met his accusers in his life.

The defense noted several inconsistencies and anomalies in the testimony of the complainants. First, they chose to testify not as complainants but rather as witnesses, which would mean they were not seeking restitution of the money they allege had been defrauded from them. This seems odd since they had presented themselves as men desperate to find work, in which case the money they had lost would have represented a significant sum to them.

Second, in their original written complaints and testimony in court, they referred to a man who gave his name as “Soltan” and who introduced them to Moumni and was allegedly an accomplice in the fraud. The police report on the case, dated February 2, 2010, mentions “Soltan” as an accomplice. Moumni’s lawyer petitioned the court to identify and summon Moumni’s alleged partner-in-crime. Yet at no time during the course of the case did the court do so. The prosecutor justified the absence of Soltan by saying that all they had for him was a name, possibly only a nickname, and could not locate him.

The defense also pointed out in court contradictions between the testimony that the two complainants gave in court and what they had put in their written statements to the police more than one year earlier, relating to their own personal information: their city of residence, whether they were employed, and their family status.

The appeals court on December 22, 2011, upheld the verdict, but reduced the sentence to 20 months. On February 4, 2012, a royal amnesty freed Moumni from prison, after he had served 17 months.

Moroccan authorities provided Human Rights Watch a written defense of the judiciary’s handling of the case, contending that they carried out his arrest and trial with respect for the law at every stage. Here are key excerpts:

As the case documents show, the aforementioned [Moumni] was placed under garde à vue [pre-arraignment police custody] in the station of the judicial police, which is under the supervision of the public prosecutor, beginning September 27, 2010, at 6 p.m. until 11 a.m. on September 30, 2010, after the period of garde à vue was extended for 24 hours, with the approval of the public prosecutor, as per the legal requirements set forth in the Code of Penal Procedure (article 66, first paragraph), and his family was notified about this procedure.

As the complete record demonstrates with regard to the accused, the judicial police heard the complainants, who were able to pick him out from among several persons who were presented in front of them.

As to whether the police informed Moumni’s family about his arrest, the government stated that Moumni’s police statement acknowledged that the police had notified his next of kin.[44] However, as noted above, Moumni repudiated his statement, saying it had been extracted through torture; and his wife, meanwhile, said that no one in the family knew his whereabouts until he was able to call them from Salé prison on September 30.

On the allegation that his confession was obtained under coercion, and that he was denied his right to a lawyer, the statement from the authorities to Human Rights Watch said:

After the judicial police heard the accused in legal proceedings, his remarks were read to him, and he signed the record in his own handwriting without any coercion, as he indicated in front of the public prosecutor. Additionally, when present before the prosecutor and told of his right to have a lawyer be brought immediately to his defense, the accused indicated that he would defend himself, whether it be before the prosecutor or the court itself. During the period of appeal, Mr. Abderrahim Jamaï, a lawyer, assisted him (the accused) during the court’s proceedings. The court based its decision on the oral arguments and the content of the judicial police reports, which are deemed credible in cases involving less serious crimes, unless the defense proves the contrary (article 290 in the Code of Penal Procedure).

On the allegation that he was tortured, the statement added:

[Moumni] did not raise being subjected to torture and ill treatment when appearing before the prosecutor, or during the trial, or even after his appeal of the first instance verdict, even though the law permits him to request a medical examination when brought before a prosecutor for the first time. It is also required of this judge to automatically investigate the matter if it is warranted, and the crown prosecutor did not note any signs of violence on the accused, and the aforementioned never requested a medical exam. The subject of his torture was not raised until after the discussion of the case by the court of appeals, and the court found nothing to prove this. Noting that the aforementioned and his defense did not present any complaints on the matter, and it remains his right to issue a complaint to the public prosecutor directed at those who allegedly tortured him.

As noted in above, this official account differs radically from Moumni’s account. Moumni contends that authorities never notified any relative of his arrest, that they transferred him to secret detention, that he was tortured into signing a false confession and a waiver of his right to a lawyer, and that he immediately flagged the torture to both the prosecutor and the trial judge, showing him marks on his shins, only to have them cut him off and omit mention of his declarations about torture in the record of these hearings.

With respect to Moumni’s torture allegations, authorities defended the court’s discounting of them, saying they lacked credibility since, according to authorities, he did not raise them until after his first appeals trial, and that, moreover, the prosecutor noticed no signs of torture on his body when the prosecutor received him directly out of police custody.

There is no third party who can corroborate Moumni’s claim that he raised his torture at his first appearance before the prosecutor or at his first trial only to have the court ignore them. This is because no lawyers or outside witnesses attended these sessions.

In two other trials described in this report, the Belliraj and Gdeim Izik cases, Moroccan authorities made similar arguments to defend the guilty verdict, stating that the defendants did not raise torture and mistreatment until late in the trial, and therefore the court acted appropriately in discounting these claims. In fact, the court’s minutes of these hearings show that at least some of the Belliraj and Gdeim Izik defendants raised allegations of torture early in the process. In Human Rights Watch’s view, in these cases the courts did not take seriously defendants’ claims of torture even when they allege they raised them at an early stage.

In a statement that Human Rights Watch received from Morocco’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, on September 27, 2011 and that is reproduced in Appendix I, authorities said that the statements made to the police by the two complainants against Moumni contained the details of their identities, addresses, and national identity cards. Therefore, it would be simple, authorities implied, for Moumni’s defense team to contact them or ask the court to summon them.[45]

However, as noted above, it was not so simple. Defense lawyer Abderrahim Jamaï petitioned the court to summon the two complainants and engaged a bailiff (huissier) to deliver the summons to them. The bailiff looked for one of them and wrote a statement saying that he could not find him at the address provided, Jamaï said. Despite defense efforts to summon them, the complainants did not appear in court in the first two trials. They first appeared only after the Court of Cassation had quashed the appeals verdict and ordered a retrial partly on the grounds that the court had not justified its failure to summon the complainants or their lawyer. When they finally appeared in court, during the second appeals trial, the defendant had already spent 15 months in prison.

The “Belliraj” Mass Terrorism Trial

Four years after this mass terrorism trial that resulted in the convictions of 35 defendants, 21 or them remain in prison. The case attracted substantial attention because among the defendants were six political figures, including senior figures in four political parties—three of them moderate Islamist parties, and the fourth, a socialist party. The case came to be known by the family name of the alleged ringleader, Abdelkader Belliraj.

The Salé Court of Appeals, which has jurisdiction nationwide over all charges under the 2003 counter-terrorism law, convicted all of the defendants on July 29, 2009, in the first-instance trial, of various of the following charges: endangering internal security by forming criminal gangs aimed at committing terrorist acts within the framework of a collective project to cause grave harm to the public order by intimidation; trafficking and possession of weapons and firearms to be used in the implementation of terrorist plans, forging official documents and identity theft, collection of funds, properties and assets for the implementation of terrorist plans, money-laundering, and theft.[46]

The appeals court upheld the verdicts on July 16, 2010, while reducing sentences for six of the defendants.[47] In June 2011, the Court of Cassation confirmed most of the verdicts but sent six of the defendants back for new trials at which five were convicted again and one was acquitted. The latter is Abdelazim at-Taqi al-Amrani, who had already completed his three-year prison sentence.

Although the government described the organization as “one of the most dangerous terrorist organizations to be dismantled recently,”[48] the charges against them included no concrete acts perpetrated since 2001. Moreover, the concrete acts attributed to them included murders in Belgium that Belgian authorities never prosecuted, and a robbery in Casablanca for which others had already been tried and convicted in the mid-1990s.

Sessions of the Belliraj trial were open to the public; observers from Human Rights Watch and other international and Moroccan organizations watched the proceedings without impediment. Human Rights Watch attended three of the numerous trial sessions. The trial judge allowed the lawyers and the defendants to speak, including about the torture they said they had endured; their allegations are reflected in the written verdict. The court provided translators for those defendants who spoke French better than Arabic.

Court Convicts Based on Police Statements Without Investigating Defendant Claims of Torture, Falsification

The guilty verdict is based overwhelmingly on the statements purportedly made to the police by the defendants themselves, statements that corroborate one another and, when taken together, incriminate all of the defendants for their involvement in an elaborate terrorist organization that existed from the early 1990s until the police arrested its members in early 2008. This heavy reliance on police statements to convict is similar to other trials in Morocco of terrorism suspects.[49]

As Human Rights Watch argued in its previous reporting on the Belliraj case,[50] the main prejudice to the defendants’ right to a fair trial was the court’s failure to make a demonstrable effort to determine the veracity of their claims that they had been victims of torture, their statements falsified, and other illegal acts. If true, these acts would warrant prosecution as violations of Moroccan law and also would lend credence to their claims that their police statements were inaccurate, and not legally admissible as evidence. The only significant evidence introduced in court other than these confessions was a weapons cache. However, the prosecution presented little if any evidence connecting the defendants to weapons other than their confessions. The written judgment does not dwell on the weapons as an incriminating piece of evidence.[51]

Wives of “Bellarij” defendants, September 14, 2012. L to R: Houriya Ameur, Samira Rammache, and Maymouna Bosh, wives respectively of Mokhtar Lokman (serving an 15-year term), Mansour Belaghdeche (freed in February 2013 after serving a 5-year term) and Ahmed Khouchiâ (serving an 8-year term). ©2013 Eric Goldstein/Human Rights Watch

The defendants’ main line of defense was to repudiate their police statements and to challenge the accuracy and voluntariness of the police statements made by their co-defendants. If the court found the police statements to be inadmissible as evidence, it would presumably acquit them in the absence of other compelling evidence against them.

Some of the defendants repudiated their “confessions” before the investigating judge. Some told the court at their very first appearance that they had been the object of police violence while others did not do so until months later, during the trial phase. Others challenged their confessions on grounds other than torture: they stated that the police had not subjected them to physical violence so much as tricked them into affixing their signature to doctored versions of the statements they had reviewed and approved. In any event, by the trial phase, all of the defendants had repudiated their confessions.

In the end, both the court of first instance and the court of appeals rejected all efforts by the defendants to repudiate their police statements. The court of first instance’s written judgment justified the guilty verdicts by explaining that the defendants’ claims of coercion and falsification were “unproven,” made too late in the process, and in any event undermined by the level of detail and cross-corroboration in the various defendants’ statements when taken together. The judgment concluded:

[The court found its basis for a guilty verdict] in the documents in the case file and the statements that the accused made … to the judicial police, which were detailed and precise in terms of dates and locations…and which corroborated one another. Since there is nothing in the case file to indicate the statements were the product of torture or coercion they should be admitted as evidence -- especially since the court is confident of their veracity from having discussed them with the defendants at the hearing [...] and since there is nothing that should prevent the court from admitting into evidence these statements that the defendants made incriminating others before the judicial police and during the investigation. This gives the court confidence and a basis for forming an intimate conviction about the matter, thus leading it to find the defendants guilty.[52]

The written verdict of the appeals trial, which reaffirmed all 35 convictions but reduced some of the sentences, reasons similarly.

A court should be vigilant when the prosecution’s case is built almost entirely on defendants’ police statements that incriminate themselves and one another, and when the case lacks other forms of corroborative evidence such as eyewitness testimony, authorized wiretaps or video surveillance, reports by informants, fingerprints, or other forms of forensic evidence.

If the report of the investigating judge is to be believed, all of the defendants, within a few days of their arrest, voluntarily confessed to crimes of great gravity. For example, the two political party chiefs among the co-defendants, Mustapha Mouâtassim and Mohamed Merouani, implicate themselves and others in years of plotting violent attacks, including weapons-trafficking, an attempt to rob a vehicle transporting cash, and an attempt to assassinate a Jewish citizen.

However, the defendants claimed their confessions had been obtained by torture or ill-treatment or forgery. Faced with such claims, the court should have tried to ascertain whether the police obtained the statements in a legal fashion before admitting them into evidence. The case file shows no record of any forensic medical examination conducted on any of the defendants, and the court’s written judgment gives no indication that it had probed the matter.