Summary

Arif B. was just 15 years old in early 2011 when he left Afghanistan to travel to Indonesia by himself.He borrowed US$7,000 to pay smugglers to bring him to Jakarta. From there, he made his way to Banjarmasin, a town in South Kalimantan, and boarded another smuggler’s boat to take him on what he hoped would be his final destination: Australia.

The crossing from Banjarmasin to the nearest Australian territory covers approximately 700 miles, and is perilous and often fatal, plied by unseaworthy vessels that lack sufficient navigation equipment, food, or fuel. Seven days into the 15-day journey, Arif’s boat went into distress. A passing cargo ship picked up the passengers, including Arif, and took them to the Indonesian police, who ignored the fact that Arif was a child traveling alone, half a world away from his parents. Immigration officials held the passengers overnight in an informal detention facility in Samarinda, East Kalimantan, before transferring them to the Balikpapan Immigration Detention Center (IDC), some 60 miles away.

Arif remained at Balikpapan IDC for 50 days, confined to a cell with unrelated adults for 22 hours each day. When he tried to escape, one day after arriving at Balikpapan, the guards beat him. He told Human Rights Watch,

That day I was beaten up very roughly…. There were eight or nine people beating me, most were guards and there was one person from the outside. They hurt my shoulder, my ear, my back. I was beaten with one of the other people who was caught. It was in the courtyard, everyone was there.... They saw and watched. Including one family from Iran, with a seven-year-old boy. He was watching too.

After 50 days, Arif was taken to Kalideres IDC near the capital Jakarta, one of Indonesia’s largest of the 12 or so IDCs nationwide. There, he bribed an immigration official with $400 to secure his release.

Arif tried to make the boat crossing to Australia again in December 2011. Again, his boat went into distress, but this time the consequences were fatal. Arif reports that hundreds of his fellow passengers died, and he himself nearly drowned:

We spent eight hours on the boat before it was in trouble, then three nights floating in the boat while it was sinking down.... For three days and nights, no water and food. We kept climbing higher and higher as the boat was sinking.

After Arif was rescued, Indonesian authorities brought him back to Jakarta, and all but turned their back on him. Now 17, he lives in a shelter that a non-governmental organization (NGO) runs near Jakarta for unaccompanied migrant children. Although Arif has paperwork certifying that he is a refugee from the UN’s refugee agency, UNHCR, the Indonesian government does not recognize him as in the country legally. The government does not provide guardianship or other assistance to unaccompanied boys like Arif, and he cannot work legally, or move freely around the country. He hopes to be resettled to Australia, but in the meantime has no school to go to, and claims he still feels the psychological trauma of his flight, detention, and near-drowning.

**

A Growing Problem

Despite his hardships, Arif is now one of the luckier ones: he has a place in a shelter and refugee status from UNHCR. Many other migrant children in Indonesia—both those traveling with parents or other guardians, and those traveling alone—are still detained, abused, and neglected.

Each year, a growing number of asylum seekers—primarily from Afghanistan, Somalia, Sri Lanka, and Burma— enter Indonesia in search of safer lives. At the end of February 2013, there were 9,226 refugees and asylum seekers in UNHCR’s active caseload in Indonesia, a 2,000 percent increase since 2008.

Almost 2,000 asylum-seeking and refugee children were in Indonesia as of March 2013.During the year 2012, 1,178 unaccompanied children entered Indonesia, the highest number in recent years.The real number of migrant children is likely to be far higher since many migrants and asylum seekers—including children—do not register with UNHCR, preferring to remain out of sight and try to make their way to Australia.

While many migrants and asylum-seeking children, like Arif, may try to reach Australia, they often spend months or years caught in Indonesia. This report focuses on the thousands of children—accompanied and unaccompanied—who enter Indonesia every year, and it documents the abusive conditions and interminable waits children face during the months and years they spend in limbo in Indonesia.

Thousands Detained and Abused

Migrant children—both accompanied and unaccompanied—are arbitrarily detained in terrible conditions for months or years, without knowing how long they will be held. Of the 102 migrants interviewed by Human Rights Watch, 82 were or had been detained. Of the 42 children covered in our research, all but 7 of them were or had been detained. Safia A., an Afghan refugee, was held with her husband and three daughters aged 10, 6, and 4 years old in a cell at Pekanbaru IDC for a year: “My children asked and asked, ‘When can we go outside?’ But … we have no answers for them.”

Indonesian law permits immigration detention for up to 10 years without judicial review. As a result, many children remain in detention for years, facing an array of abuses including physical violence from immigration officials, bribery and confiscation of property, and lack of basic necessities. The impact of prolonged, indefinite immigration detention is particularly severe for children, many of whom experience post-traumatic stress disorder or depression.

The detention centers are overcrowded, unsanitary, and can flood during the rainy season. One child with whom we spoke said there was one toilet for thirty-seven people when he was detained at Pontianak IDC for seven-and-a-half months. Interviewees complained that the food in the detention centers is dirty and lacks the nutrition that young children need. Some migrants and asylum seekers said they were not allowed outdoors for weeks or months. “How can I explain what it’s like when we went out?” said 17-year-old Faizullah A., who was kept inside for five months. “We were like the wild, running all around. We were thinking we were alive again.”

Most unaccompanied children—like Arif and Faizullah—are detained with unrelated adults at risk of violence and exploitation. Sher K., an adult asylum seeker, was detained at Kalideres IDC:

There were 20 or 30 unaccompanied minors… Whenever the boys talked on the phone with their families, they would cry. The boys cried all the time. They were the most powerless in there. They would get attacked.

Both adults and children described guards kicking, punching, and slapping them or other detainees. Some reported that guards tied up or gagged detainees, beat them with sticks, burned them with cigarettes, and administered electric shocks. For instance, Sher K. was beaten after trying to escape:

Three shifts of guards, they would each come with sticks and knives and hit us. Six or seven guards would come and beat us for fun. It lasted for three days, every day, all day. They did it for fun. One friend of mine … had a broken arm. My face was black and blue. My kidney was damaged for a month—it was bad—from the beating.

Several unaccompanied boys told Human Rights Watch that Indonesian immigration guards beat them in detention. In another case, parents said immigration guards forced their children, including their four year old and six year old, to watch guards beat other migrants.

The ill-treatment can be fatal. In February 2012, Taqi Naroye, a 28-year-old Afghan asylum seeker was beaten to death in Pontianak IDC after attempting to escape. Police had returned him to the facility in good health. The next day, he was delivered, dead, to the local hospital. According to our interviews, other migrants witnessed his beating, including one unaccompanied migrant child who was then beaten himself.

Accountability for abuses is generally lacking. Apart from some minor changes at Pontianak, there has been little accountability for Naroye’s death. There has been no nationwide review of physical abuse in detention, and there are no comprehensive procedures in place to train immigration staff or provide a complaints mechanism for detainees. Nor does the immigration detention system have published regulations establishing clear consequences for violations of detainees’ rights.

No Refuge, no Protection

Despite the growing numbers of migrant children, Indonesia fails to respond to their needs. It does not provide access to asylum for migrant children or their families and leaves unaccompanied migrant children alone, unprotected, and without access to services.

Indonesia has not ratified the 1951 Refugee Convention or its Protocol, and does not have adequate domestic asylum laws. As a result, processing asylum applications falls to UNHCR, which provides certificates recognizing individuals and families as refugees. Yet UNHCR’s process comes with many delays, leaving hundreds of migrant children in detention, and these certificates carry little official weight with the Indonesian government.

Indonesia does nothing to assist unaccompanied children, some of the most vulnerable asylum seekers. Though Indonesia is obliged, due to its ratification of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, to provide unaccompanied children with guardians, it has neglected to assign that role to any government entity. Without guardianship, some children remain in detention, unable to be released without anyone to care for them.

Outside detention, only a handful of unaccompanied children, like Arif, have any assistance. There are places in shelters for perhaps 140 children at any time. Others still live on the street or in crowded private accommodation with other migrants, at risk of exploitation, destitution, and re-arrest. None receives the care to which they are entitled by law from the Indonesian government.

Even with recognition from UNHCR, migrant children—whether accompanied or unaccompanied—have no viable future in Indonesia. They have no legal status under Indonesian law, cannot work, and have limited access to education. Constantly vulnerable to arrest or rearrest for violating these or other rules, refugees are reluctant to seek police protection should they become victims of crimes. Only a small minority (just 247 people in 2012) are resettled to third countries.

Given this toxic limbo, it is no wonder that migrants, asylum seekers, and refugees frequently choose to take smugglers’ boats to Australia, despite the risks posed by these journeys. One Afghan father explained, “It’s taking years, and people’s families are back home, needing money. At least on the boats, you know your fate in 36 hours, in 24 hours.”[1]

Role of the Indonesian, Australian Governments

Indonesia bears primary responsibility for its appalling treatment of migrants, asylum seekers, and refugees. However, Australia has pursued a strategy of immigration enforcement first, refugee protection second which leave migrants with few options other than to risk boat journeys. It has assisted the Indonesian government in constructing new immigration detention facilities, and Australia supports UNHCR and IOM operations in Indonesia, including some inside the detention centers.

In August 2012, Australia reinstated the much-denounced “Pacific Solution,” which sends migrants to offshore facilities in Nauru and Manus Island, Papua New Guinea, for processing of their asylum claims, which should be heard in Australia itself. Australia claims that such measures help to deter irregular boat migration, yet in the months after the Pacific Solution was reinstated, significant numbers of boats continued to arrive in Australian territory.

While Australia and Indonesia do have the right to control irregular immigration into their countries, they must do so in a way that respects children’s rights and provides protection for some of the most vulnerable new arrivals. Both Australia and Indonesia should prioritize children’s rights above immigration enforcement, so that children receive appropriate protection and care. Children like Arif B., who show great courage and resilience in journeying far from home, deserve the chance to have a meaningful future.

Key Recommendations

To the Indonesian Government

- Immediately review all immigration detention policies, end guards’ physical abuse of detainees, and improve the appalling conditions of detention.

- Immediately release all unaccompanied migrant children, and actively explore alternatives to detention for children.

- Ensure that, in the rare occasions where children are detained, that conditions are suitable, that children are not held with unrelated adults, and that they have access to education.

- Ensure that unaccompanied migrant children are granted guardians, legal assistance, and assistance with their basic needs.

- Ratify the 1951 Refugee Convention and implement a fair, humane, and speedy asylum system.

- Take wide-reaching measures to respond to the needs of asylum seekers and refugees throughout the asylum process, including providing viable options for life in Indonesia.

To the Australian Government

- End aggressive attempts to deter irregular migrants from reaching Australian territory.

- Demand that Indonesia live up to minimum human rights standards before providing funding to detain irregular migrants.

- Take advantage of opportunities to ensure a meaningful life for refugees awaiting resettlement in Indonesia, including through funding access to education, as one measure in deterring boat migration.

Methodology

Human Rights Watch carried out research for this report in Indonesia in August and September 2012. Two researchers interviewed 102 migrants between the ages of 5 and 66, including 36 women and girls.

Forty-two of our interviewees were, according to their own accounts or those of their parents, children when they entered Indonesia. Thirty-eight were still children when we interviewed them. Eleven were unaccompanied (without a parent or guardian) when they entered the country. We interviewed the parents of six children below the age of five years to understand the experiences of very young migrant children.

43 percent of our interviewees were from Sri Lanka (most of whom were Tamil); 26 percent were from Afghanistan (many of whom were Hazara[2]); 17 percent from Burma (mostly Rohingya[3]); and 7 percent from Somalia. The other interviewees were Nepali, and people born in Iran of Afghan descent. According to our interviews with officials from government, intergovernmental organizations, and NGOs, there are also asylum seekers in Indonesia from Iraq, Iran, Libya, Pakistan (including people born in Pakistan of Afghan descent), China, Russia, and various African countries.

We conducted some interviews in English and Nepali, and other interviews with the help of interpreters in a language in which the migrant was comfortable (such as Pashto, Dari, or Tamil). We interviewed migrants and asylum seekers in areas near residential facilities in Medan, Bogor, and elsewhere, as well as in detention facilities. We explained to all interviewees the nature of our research and our intentions concerning the information gathered through our interviews, and we obtained verbal consent from each interviewee. No interviewee received financial or other compensation in return for interviewing with us.

Most interviews were conducted individually and privately; this included extensive, detailed conversations with released detainees. In addition, Human Rights Watch researchers visited several immigration detention facilities and conducted group interviews with detainees (the number of participants ranged from 2 to 12). In order to safeguard interviewees who were detained at the time of our interviews, our conversations took place outside the hearing of immigration staff.

Human Rights Watch researchers met a number of government officials concerned with migration, who worked for the police, Imigrasi (directorate general of immigration), and the Ministry of Social Affairs. We also sent letters requesting data and other information concerning immigration and detention in Indonesia on December 21, 2012, and again on March 5, 2013, to the chief of national police, the minister of law and human rights, and the ambassadors to the US and to the UN in Geneva and in New York. We received one acknowledgement of our request for information but no substantive answers to any of the questions posed.

In addition, we met with representatives from intergovernmental organizations including the International Organization for Migration (IOM), as well as staff members of NGOs, migrant community leaders, journalists, and human rights lawyers and activists. While Human Rights Watch was able to obtain UNHCR data on asylum seekers in Indonesia, UNHCR told Human Rights Watch it was unable to comment on Indonesia’s treatment of refugees and migrants.

Virtually all names of adult migrants interviewed have been replaced by pseudonyms to protect their identity; where the real name is used, that is indicated. All names of children have been changed. Where migrants were interviewed inside detention facilities, we have taken additional steps to avoid the possibility of identifying the individual, for instance by concealing the location of the interview or by withholding precise details of the migrant’s case. Likewise, many staff members of government agencies, intergovernmental organizations, and NGOs in Indonesia are not identified at their request.

Human Rights Watch did not assess whether the migrants we spoke to qualified for refugee status. Some, perhaps many, undoubtedly do. This report instead focuses on how the Indonesian government fails to uphold migrants’ human rights, regardless of whether or not those migrants have legitimate asylum claims or other protection needs, and how Indonesia’s policies should be improved.

Terminology

This report focuses on migrants traveling through Indonesia, many with the goal of seeking refuge in Australia. Most lodge refugee claims with UNHCR in Indonesia, which is not party to the 1951 Convention and has made no commitment to provide permanent asylum. UNHCR recognizes some as refugees but has no authority to grant asylum. Some never file refugee claims with UNHCR in Indonesia, hoping instead to file in Australia.

An “asylum seeker” is a person who is trying to be recognized as a refugee or to establish a claim for protection on other grounds. Where we are confident that a person is seeking protection, whether in Indonesia or Australia, we will refer to that person as an asylum seeker. A “refugee,” as defined in the 1951 Convention and its 1967 Protocol, is a person with a “well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion” who is outside his country of nationality and is unable or unwilling, because of that fear, to return. In this report, we use the term “refugee” when UNHCR in Indonesia has recognized that person as a refugee, though it should be noted that UNHCR recognition of refugee status is declaratory, which means that people are, in fact, refugees before they have been officially recognized as such.

Although international law defines “migrant workers,” it does not define “migrants.” In this report, “migrant” is a broad term to describe third-country nationals in Indonesia. We use the term inclusively rather than exclusively, including people traveling in and through Indonesia and passengers on boats moving irregularly. The use of the term “migrant” does not exclude the possibility that a person may be an asylum seeker or refugee.

In line with article 1 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child, the term “child” refers to a person under 18.[4] We discuss children traveling with their families as well as unaccompanied children. The report discusses these groups separately and together, and uses the term “migrant children” to refer to them together. The term includes children seeking asylum or those granted UNHCR refugee certificates.

The definition of “unaccompanied migrant child” comes

from the term “unaccompanied child” used by the Committee on the

Rights of the Child. According to the committee’s General Comment No. 6,“‘Unaccompanied

children’ are children, as defined in article 1 of the Convention, who

have been separated from both parents and other relatives and are not being

cared for by an adult who, by law or custom, is responsible for doing

so.”[5]

I. Seeking Refuge: Journeys to Indonesia and Australia

For tens of thousands of migrants and asylum seekers—most from East Africa and South and Southeast Asia—Indonesia is an intended way station along a difficult and dangerous journey to Australia, where migrants hope to find opportunities for a better life and, often, protection from violence and persecution in home countries. Yet most stay in limbo in Indonesia for months or years. As of February 2013, most refugees and asylum seekers in Indonesia came from Afghanistan, Burma, Sri Lanka, and Iran.[6] Thousands of children travel this route annually—some with their families and others alone.[7]

Indonesia has seen a remarkable increase in the numbers of people seeking asylum in the past five years: up from 385 new arrivals in 2008 to 3,230 in 2009.[8] Large numbers of new arrivals continue—in July 2012 alone, for example, there were 753 new cases. At the end of February 2013, there were 9,226 refugees and asylum seekers in the UN refugee agency (UNHCR)’s active caseload in Indonesia, of whom 1,938 were recognized refugees.[9]

There are more migrants and asylum seekers who choose not to register with UNHCR and are not included in the statistics above. Some may not wish to lodge an asylum claim, seeing few benefits to the procedure in a country that does not officially recognize refugees, and hoping to move on to Australia sooner rather than later.[10]

Other organizations, including the International Organization for Migration (IOM), assist people who are not registered with UNHCR; IOM, for example, reports as of February 2013 487 beneficiaries who have never registered with UNHCR or who have been denied refugee status by UNHCR.[11] It is hard to know the total numbers of refugees, asylum seekers, and other migrants in need in Indonesia, many of whom receive no assistance at all.

The Indonesian government did not respond to multiple Human Rights Watch requests for information as to how many migrants there are in the country in addition to those registered with UNHCR.

Lengthy and Dangerous Journeys to Indonesia and Australia

Almost all of the migrant children we interviewed—both those who traveled with families and those who traveled alone—had stopped in Indonesia en route to Australia, risky and expensive journeys of months and even years. Most migrants and asylum seekers interviewed cannot fly directly to Australia because they lack visas needed to board planes. Instead, the journey typically involves a smuggler, either in a migrant’s home country or in a neighboring or transit country. For instance, an Afghan might contract with a people smuggler at home, or through Afghan communities in Iran or Pakistan.

For example, Karim Ali S., a 34-year-old Rohingya man, left Burma on September 20, 2011, with his wife and two cousins, 29 and 24 years old, bound for Australia. We went through Malaysia,” he said. “[After several months there], we paid 10,000 Malaysian ringgit (about US$3,225). We were three days and two nights on a boat [from Malaysia]…. The agent stopped on an island [in Indonesia] … we didn’t know where we were.”[12]

Fartuun A., originally from Somalia, flew to Indonesia from Yemen with her sister, brother in-law, and their four children in 2011. She said,

It cost $1,000 each. We paid a smuggler and used fake passports…. The smuggler said that he would take us to Australia, but then in Indonesia he disappeared…. In Jakarta he took us to a hotel, we stayed the night, and then in the morning he was gone…. Eventually [my brother-in-law] found a Somali man and arranged for us to come here [to the migrant communities outside Jakarta].[13]

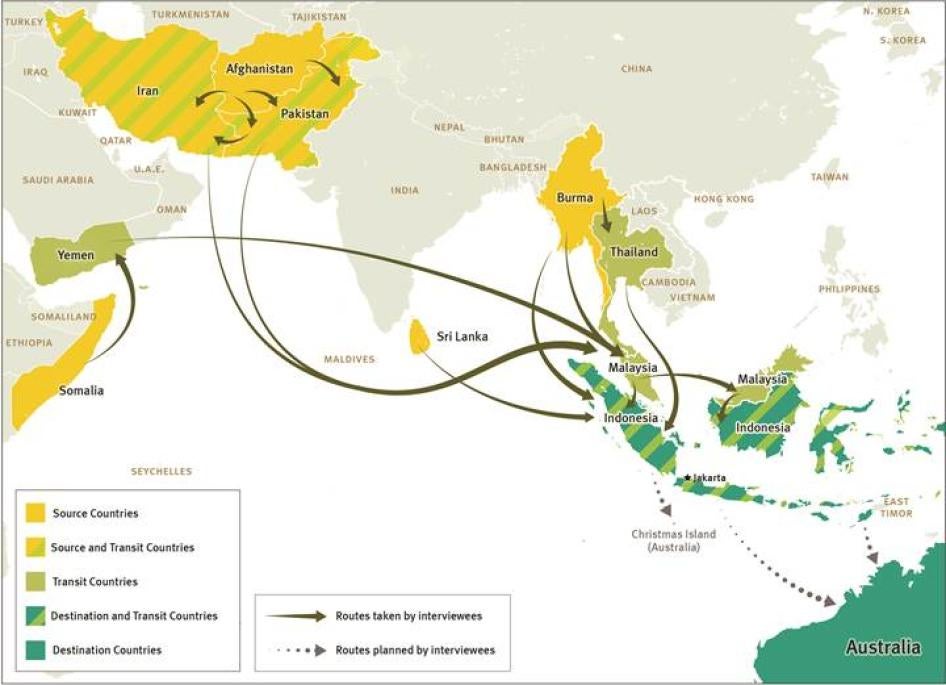

Sample migration routes based on Human Rights Watch interviews. © 2013 John Emerson/Human Rights Watch

Unaccompanied migrant children, who travel without parents or guardians, are particularly vulnerable to exploitation on smuggler routes. Rafiq A., a Burmese Rohingya boy, described his journey to Indonesia in February 2011 when he was 14 years old:

We had a lot of problems in Burma.... My parents thought I was in danger so they told me to leave…. The boat ride was long—18 days and nights. We arrived in Thailand, and rested for one day and one night. The Thai navy took our boat motor and our food and put us in the sea. They took us to the middle of the sea and they left us. We had some bamboo and some plastic tarpaulins, so we made a sail. We traveled for three days like that. In the sea we saw a fisherman’s boat. He guided us to Aceh. Police arrested us.[14]

Ahmad Z., a Hazara boy, was 17 years old when he found a smuggler in Kabul to take him from Afghanistan to Pakistan and then to Malaysia, where is stayed in a hotel for 10-12 days before taking a boat to Indonesia:

[I]t was four hours long and we landed in Sumatra. The smuggler’s contact met us in Indonesia and took us to his house. We stayed one or two days there…. He sent us to another place in Sumatra, and we spent three months there. Every day he would come and tell us, “Oh tomorrow I will send you [to Jakarta].” We couldn’t go outside at all. One day he dropped us at the Padang airport, all 12 Afghan Hazaras [eleven adults and one child]. We were caught in the airport by the police.[15]

Azim M. was also 17 when he traveled from Kabul with smugglers in August 2012. He went to Dubai, and then to Jakarta, where a smuggler promised to take him on to Australia. “He promised that after one month he would take me, but nothing has happened,” Azim said.[16]

Being smuggled to Indonesia is much more expensive than making the same trip by commercial plane. Our interviewees reported varying costs: for example, 300,000 Sri Lankan rupees (around $2,363) for one unaccompanied boy who traveled from Sri Lanka to Indonesia;[17] $3,200 for a Rohingya family of three that traveled from Malaysia to Indonesia (having previously made a separate trip from Burma to Malaysia);[18] and between $7,000 to $12,000 for unaccompanied boys who traveled from Afghanistan to Indonesia.[19] Similar trips by air, according to fare quotes found on-line in May 2013, are significantly cheaper: for instance, a one-way ticket from Colombo to Jakarta costs around $400-500; a one-way ticket from Kabul to Jakarta costs around $750-1,000; and a one-way ticket from Kuala Lumpur to Jakarta costs less than $100.

Once in Indonesia, many migrants and asylum seekers will contract with smugglers for onward travel to Australia through a dangerous boat trip. This costs an additional fee, which varies greatly but some estimates place it between $3,000 and $6,000.[20]

Boats leave from many locations, including Jakarta, towns in southern Java, and Kupang in West Timor. Many boats trips are intended for Christmas Island (one of the closest Australian territories to Indonesia).

The boat journeys are incredibly risky. Smugglers, bound by no safety regulations, overload unseaworthy boats and often fail to supply adequate amounts of fresh water, food, or fuel for the journey.[21]

Sometimes the journey is deadly. Almost 1,000 people died on the crossing between 2001 and 2012, according to known statistics[22]—a period in which the numbers of people attempting the crossing has grown considerably. There are no official passenger records for these unregulated, illegal journeys, and many hundreds more people go missing, presumed drowned, each year.[23]

Arif B., the unaccompanied migrant boy from Afghanistan, was 15 years old when his boat from Indonesia to Australia sank. He said he spent “three nights floating in the boat while it was sinking down.... For three days and nights, no water and food. We kept climbing higher and higher as the boat was sinking.” [24]

Despite the risks of the onward boat journey to Australia, many migrants and asylum seekers we interviewed felt that attempting to make the trip was preferable to the hardships of life in Indonesia.

When a boat goes into distress, Australian or Indonesian search-and-rescue obligations are triggered.[25] Some boat passengers hope merely to reach Australian territorial waters in order to call for help there.

Left without Legal Status or Protection

Indonesia

Migrants and asylum seekers receive a poor welcome in Indonesia, which has faulty or non-existent mechanisms for protecting asylum seekers and child migrants. A variety of government bodies in Indonesia offer incomplete care for migrants in Indonesia. The Directorate General for Immigration oversees immigration detention facilities and should take responsibility for migrants outside of detention but does not meet these duties. Likewise, the Ministry for Social Welfare is responsible for child protection, but is not tasked to protect migrant children.[26]

Indonesia has a recent history as a country of emigration, and indeed, the Indonesian government takes steps to protect its own citizens abroad. Indonesia has ratified the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families,[27] and it takes measures to aid Indonesians working as, for instance, domestic workers in Malaysia or elsewhere.[28] Indonesia has also taken steps toward assisting refugees, for instance by donating to UNHCR’s annual appeal in 2012 for the first time in over a decade.[29]

Because Indonesia has not ratified the 1951 Refugee Convention or its Protocol and does not have adequate domestic asylum laws, the protection of asylum seekers and refugees in Indonesia has fallen to UNHCR. IOM assists the government in operating migration detention facilities and supports some migrants outside detention; as of February 2013, it was assisting 2,946 refugees and asylum seekers in Indonesia, approximately half of whom were detained.[30]

Australia

Australia has ratified the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol and implemented it through domestic laws and procedures, and asylum seekers who reach Australian territory can apply for refugee status there. In addition, Australia resettles several hundred refugees recognized in Indonesia each year, and the government increased the number of places available for resettlement in 2012. Yet there are not enough resettlement places available for all recognized refugees in Indonesia.

Despite its ratification of the Refugee Convention, Australia has instituted punitive asylum policies that make it difficult for refugees to enter the country and ask for protection.[31] Australia has long maintained policies, including offshore processing, that deter “irregular maritime arrivals” from reaching the country. But Australia, a geographically isolated state, has erected visa regimes and other legal barriers that make it almost impossible for asylum seekers to arrive spontaneously by air legally.

Australia has repeatedly sent asylum seekers arriving by boat to Nauru and Papua New Guinea for “offshore” refugee processing, despite human rights groups repeatedly raising concerns over children’s and asylum seekers’ rights.[32] In 2012, Australia reinstated this policy after fashioning a legal mechanism to overcome a high court ruling that had found it unlawful. Yet Australia’s reinstated policy is not likely to effectively deter boat migration.[33]

These policies and others are designed to discourage “queue jumpers,” positing that refugees should wait in third countries for resettlement to Australia.[34] In reality, there is no queue for resettlement. The consequence of these policies is that people fleeing Afghanistan, Burma, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and elsewhere get stuck in Indonesia, faced either with a prolonged wait for a slim chance at resettlement, or compelled to take the smugglers’ boats to Australia at great personal risk.[35]

Australia co-chairs, along with Indonesia, the Bali Process, a regional intergovernmental body on people smuggling and trafficking. The recent initiative, with UNHCR, to map the protection needs of unaccompanied and separated children in the southeast Asian region is a welcome start. However, as co-chairs, both countries should ensure that immigration enforcement measures that emerge from the Bali Process prioritize children’s rights above policing measures. While states retain the capacity to control their borders, they also must respect the rights of all children in their territories, including non-nationals.

II. Lack of Protection for Unaccompanied Migrant Children

Unaccompanied children (children who travel without parents or other guardians) are particularly vulnerable to rights violations outside of their country of origin.

In recent years, around 1,000 children annually have arrived in Indonesia after traveling alone from Afghanistan, Burma, and other countries. During the year 2012, for example, 1,178 unaccompanied minors were registered in Indonesia by UNHCR.[36] Most were boys, and 81 percent were from Afghanistan, with Pakistan and Burma as other main countries of origin.[37] While most unaccompanied children arriving in Indonesia are 16 or 17, some 3 percent of the arrivals in 2012 were below 14 years old.[38]

Because some of these children move through Indonesia relatively fast, and because children age out of this category, the cumulative numbers of unaccompanied minors in the country fluctuates. As of March 2013, there were 718 unaccompanied minors registered with UNHCR in Indonesia; 121 of them, or 16 percent, were in detention.[39]

There are likely more unaccompanied minors in Indonesia than those included in UNHCR’s statistics since not all children register with UNHCR, either because of periodic backlogs in UNHCR’s registration system, or because they decide that registration does not provide any significant benefits. Others may be in detention awaiting UNHCR’s first visit, which can take weeks or months.

According to the Committee on the Rights of the Child, these children deserve special care.[40] The committee, the body authorized to interpret the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, a treaty to which Indonesia is party and which it must follow, issued General Comment No. 6 in 2005. General Comment No. 6 dictates that when unaccompanied migrant children enter a country, they should be assigned a guardian who can look after their material needs, and receive legal representation in immigration proceedings.[41]

Yet Indonesia, for the most part, fails to meet the obligations described in General Comment No. 6. It leaves these children without guardianship, so no-one takes responsibility for assisting these children in accessing basic services or making decisions about future migration. They are not given free legal representation, making it hard for them to understand asylum proceedings and present their case. As discussed below, every year hundreds are detained with unrelated adults, and many are subject to physical abuse. Of those not detained, only a handful of children have shelter, and others are left to fend for themselves.

No Guardianship, no Shelter

Indonesia fails to provide unaccompanied migrant children in its territory with guardianship, despite its obligations to protect this exceptionally vulnerable group. Without a guardian, children have no one to look after their basic needs, and do not receive guidance on changing their migration status or on other matters. Some children remain in detention, while others are on the streets without any assistance with basic needs such as shelter and food.

The Committee on the Rights of the Child specifies that unaccompanied migrant children must be assigned a guardian to protect their interests.[42] According to the Committee, the guardian’s job is much broader than that of a legal representative, to which the child is also entitled: the guardian, who need not be a lawyer, should be consulted on all actions taken for the child whether they are legal in nature or not; should have the authority to be present in all decision-making processes, including immigration hearings, care arrangements, and efforts to make long-term plans for children; and should be knowledgeable about child care in order to ensure that the child’s “legal, social, health, psychological, material and educational needs are adequately covered.”[43]

As far as Human Rights Watch is aware, no Indonesian government agency has been given the legal responsibility for providing guardianship to unaccompanied migrant children. An NGO, CWS, runs a shelter program for approximately 90 unaccompanied minors in Indonesia but describes the scope of their mandate as “a care and maintenance program,” not a formal assignation of guardianship.[44]

The government of Indonesia is failing not only in its responsibility to provide guardians but also to provide adequate shelter for unaccompanied minors. At the time of our investigation in September 2012, just one organization, CWS, provided shelter for unaccompanied minors, and with 93 children in facilities near Jakarta, those facilities were full.[45] As of March 2013, IOM had negotiated with the North Sumatra Provincial Department of Social Affairs (DINSOS) to house 44 unaccompanied minors with refugee status in DINSOS shelters designed for Indonesian children. IOM hopes that this model might be replicated in other provinces, including Yogyakarta and Makassar.[46] Nonetheless, with more than 1,000 unaccompanied minors arriving in Indonesia annually, and these shelters covering fewer than 140 places, these arrangements are far from sufficient.

Many unaccompanied minors are detained, as discussed below. The lack of guardianship and shelter can extend their periods of detention. According to IOM and CWS, unaccompanied minors in detention need to wait for there to be room in a shelter before Indonesia will release them. [47] At the time of our investigation in September 2012, 150 children remained in detention awaiting space to open in a shelter;[48]as of March 2013, there were 121 unaccompanied minors seeking asylum or with refugee status in detention.[49]

Those lucky enough not to be detained, but without a place in a shelter, are left to fend for themselves. This can amount to some 700 children per year without help. Some get informal assistance from other migrants. Others are left without money, food, and shelter. Ali H., 16 years old, said,

I don’t get any money. The house costs 600,000 rupiah [roughly US$61], for a bedroom with four people, one small room ... I don’t have a job. The house my family sold [in Afghanistan, to finance his trip], the money from that will last for one more month. After that, I’m not sure what I’ll do.[50]

Some boys, vulnerable without assistance, fear arrest or re-arrest. Azim M., an unaccompanied migrant boy from Afghanistan who had arrived in Indonesia two months before his interview with Human Rights Watch, was effectively confined to a small house in an area outside Jakarta that is popular with migrants. “I stay inside the house all day,” he said. “I’m afraid [immigration officials] will find me. I do nothing all day—sit inside all day.” Azim had received a token from UNHCR—a piece of paper the size of a business card indicating a date several months ahead for him to register as an asylum seeker. He said he had no other assistance from them and said he had not communicated with them since.[51]

There is a nascent understanding within the region that unaccompanied children need more care. UNHCR, in collaboration with The Bali Process, a regional intergovernmental body on people smuggling and trafficking that Indonesia and Australia co-chair, initiated a mapping project in September 2012 to understand issues faced by unaccompanied and separated children in Southeast Asia.[52]

No Legal Assistance

Unaccompanied migrant children in Indonesia receive no legal representation, either in requesting asylum or in challenging detention.[53] Article 37(d) of the CRC mandates that children deprived of their liberty should have prompt access to legal assistance, and the Committee on the Rights of the Child has emphasized that this specifically applies to unaccompanied migrant children in migration detention.

None of the unaccompanied migrant children we interviewed said they had legal assistance. Sayed M., a 16-year-old unaccompanied Afghan boy detained at an IDC with unrelated adults told us, “I’ve never seen a lawyer.”[54] Ahmad Z. was 17 years old when he was detained at Pekanbaru IDC. He said that “some people were released by an Indonesian lawyer, but I didn’t have a lawyer.” He remained in detention for almost eight months before UNHCR helped secure his release.[55]

The Committee on the Rights of the Child emphasizes that in cases where unaccompanied children are subject to administrative proceedings, including immigration or asylum proceedings, they should be provided with a legal representative (in addition to the guardianship functions described above).[56] Yet unaccompanied migrant children in Indonesia receive no such assistance at any stage in the process of applying for refugee status.

III. Abuses in Detention

It was a cage. Shut. In the jail we stayed there for a long time. I don’t know how many months.[57]

—Enayet H., an 11-year-old Burmese Rohingya boy, who said he was detained in migration facilities starting when he was 9 years old.

Migrant children—including children in families, unaccompanied children, and very young children—are arbitrarily detained in violent, inadequate detention facilities throughout Indonesia. Immigration authorities and Indonesian police arrest migrants and asylum seekers either as they cross into Indonesia or as they move towards the boats to Australia; NGOs and asylum seekers have also reported arrests in the areas outside Jakarta where many migrants live. Indonesian authorities routinely detain families, unaccompanied migrant children, and adult asylum seekers for months or even years in informal detention facilities and formal Immigration Detention Centers (IDCs). Migrants, including children, are typically detained without judicial review or bail, access to lawyers, or any way to challenge their detention.

Of the 102 migrants interviewed by Human Rights Watch, 82 were or had been detained, 76 of those in one or more IDCs. Of the 42 children covered in our research, all but 7 were or had been detained, including children ranging in age from 2 to 17 years old.[58] Thirty-two children were detained in a formal IDC, and 12 were detained in informal facilities (the numerical overlap exists because some children were detained in multiple facilities).

On multiple occasions, Human Rights Watch asked, among others, the minister of law and human rights (who oversees the Directorate General of Immigration) for both the numbers of immigrants held at the IDCs and their demographic details, but the government did not provide this information.[59] Indeed, it is not clear whether the government knows the number of or biographical details for the detainees in its facilities.[60] A high-ranking police official in Tanjung Pinang City, near one of the larger IDCs, said of those responsible for facilities, “Since they don’t recognize these immigrants as human beings, they don’t track them at all.”[61]

Data we received from IOM indicates that as of February 2013, approximately 1,450 refugees and asylum seekers, including children, who fall under IOM’s care were detained.[62] The total number of detainees in migration detention facilities is higher as not all fall under IOM’s mandate.

Indonesia operates—through the Directorate General of Immigration under the Ministry of Law and Human Rights—approximately 11to 13 formal IDCs, though not all are always occupied and sometimes officials open facilities temporarily.[63] The larger facilities include Belawan IDC, near Medan; Tanjung Pinang IDC, on Bintan Island; Pontianak IDC, in Pontianak in West Kalimantan; Kalideres IDC, in Jakarta; and Makassar IDC in South Sulawesi. The smaller facilities include Pekanbaru IDC in Riau province in central Sumatra; Manado IDC in North Sulawesi; Surabaya IDC in East Java; Denpasar IDC in Bali; and Kupang IDC in West Timor. Facilities in Bandar Lampung, in southern Sumatra, Balikpapan, in East Kalimantan, and Papua are not always open or do not always contain detainees.

Indonesian immigration detention centers. © 2013 John Emerson/Human Rights Watch

Migrants interviewed by Human Rights Watch, including children, reported being held in a number of alternate facilities in addition to the IDCs. Regional immigration offices, including those in Medan, Denpasar, Padang, and Jakarta, have holding rooms or cells, which typically are used to hold migrants for short periods of time (our interviewees who were held in these facilities referred to periods of time less than one month). In addition, Indonesian authorities use hotels or other buildings, with guards (sometimes from the Directorate General of Immigration, and sometimes from the police), to hold groups of migrants for short periods. The total number of informal facilities used to detain migrants is hard to know, as different facilities are open at different times.

Arbitrary Detention

Indonesia routinely holds children of all ages in migration detention for months or years, rather than use alternatives to detention—such as registration and community monitoring. Young children are detained with one or both parents, and unaccompanied migrant children are held with unrelated adults. Single adults are also detained for lengthy periods. Neither children nor adults have any means of challenging their detention, nor do they know for how long they will be detained. Such indefinite detention without recourse to judicial review amounts to arbitrary detention prohibited under international law.

For instance, children are arbitrarily detained at the Tanjung Pinang IDC, where according to its director, several families were detained at the time of our visit in September 2012.[64] A security officer at Tanjung Pinang said there were two unaccompanied migrant children there at the time, whom he believed to be 13 or 14 years old.[65] Another boy, Jairaj N. was 12 years old when he was taken to Tanjung Pinang where he was held for six-and-a-half months. Interviewed after his release he said, “I stayed with my mom in detention, and my two sisters, ages sixteen and six. It was very bad though, we couldn’t go outside.”[66]

At some facilities, migrant children were held with their mothers but separated from their fathers; in others, the entire family was detained in the same cell. Saasvikan P. was nine years old when he was detained at Tanjung Pinang with his family for several months:

In one room, 10 families lived…. They separated us: Mothers and children in one room, and fathers in another room. They opened the fathers’ room from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. every day. My father was not allowed to eat dinner with us.[67]

Parents did not know how long they and their children would be detained. Safia A., an Afghan woman, was held with her husband and three daughters in a cell at Pekanbaru IDC for a year; her daughters were 10, 6, and 4 years old. Safia said, “My children asked and asked, ‘When can we go outside?’ but we cannot answer. We are responsible parents, but we have no answers for them.”[68] Mariam A., Safia’s eldest daughter, added, “We couldn’t go outside the gate. It was very difficult for us.”[69]

Some parents had concerns about their children’s physical safety. Raahitha H., for example, a Sri Lankan Tamil mother who had been detained in an IDC for five months with her two-year-old son, said, “There is no safety here because there are so many men. We are scared for our children because of the other men being around us. Sometimes they fight each other, the men. My son sees them fight—he watches like entertainment.”[70]

An asylum-seeking girl, thought to be from Sri Lanka, walks

through Belawan Immigration Detention Center while detained with her family,

September 2012.

© 2012 Kyle Knight / Human Rights Watch

Parents reported worries about the impact of lengthy detention on their young children. For instance, Selva P., a Tamil man, was detained at Kalideres IDC for three-and-a-half months with his daughter, who was then four years old.

Men and women are already adults when they have these experiences, but children don’t understand them—the first thing they know in their lives is painful. We have to explain to them many times.[71]

Children and adults are also held in informal detention facilities apart from and in addition to the IDCs, including hotels and immigration offices.

Ahmad Z., an unaccompanied migrant boy from Afghanistan, was 17 years old when he arrived in Indonesia. He reported that he was held in multiple immigration offices, including the Medan office for 25 days. “Five people in one small room. It was all day, all night lock-up.”[72] Ahmad was then transferred to Kalideres IDC where he was held for approximately 14 months. Labaan A., an unaccompanied Somali boy, was 17 years old when he attempted to cross to Australia by boat, said, “The police arrested us. They kept us in a hotel (Jayana Hotel) in Sumbawa for 25 days…. The security at the hotel was Indonesian police.”[73]

These immigration detention facilities are not also used to house criminals. Nonetheless, children and adults detained repeatedly referred to their detention as jail-like, despite UNHCR standards mandating that detention of asylum seekers not be criminalized or punitive,[74] and despite the notion that detention of children, which is only permitted to occur exceptionally, must not have punishment as its purpose. Faizullah A., an unaccompanied boy from Afghanistan, was 17 years old when he was detained at Pontianak IDC for seven-and-a-half months. “The room had walls with windows [gesturing to internal windows] and a cage on one side. It was not a detention center, it was a real jail.”[75]

According to Indonesia’s immigration law, the criminal penalty for illegal entry or illegal exit is maximum one year imprisonment and/or a maximum fine of 100 million rupiah (US$10,315).[76] Any immigrant who enters Indonesia without proper documentation will be regarded as an illegal immigrant, and may be subject to detention awaiting deportation.[77] Detention is permissible until deportation is executed, and where deportation cannot be carried out, for up to 10 years.[78] Immigration officials have discretionary power to move a foreigner who “is sick, will give birth, or is still a child” out of detention and to an alternative location, though the law does not specify what that location would be.[79]

Indonesia’s laws do not give migrants or asylum seekers opportunities to challenge their detention, nor do they provide any way for them to know when they will be released.[80] Indeed, migrants rarely if ever have assistance from lawyers in challenging their detention. “There are no lawyers,” said an IOM staffer at Pontianak.[81]

Indonesia’s prolonged, automatic migration detention—without the possibility of judicial review or remedy—amounts to arbitrary detention prohibited by international treaties to which Indonesia is party. Article 9 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights forbids arbitrary detention, and the United Nations Working Group on Arbitrary Detention holds that a migrant or asylum seeker placed in detention “must be brought promptly before a judge or other authority.”[82]The Working Group’s mandate to investigate arbitrary deprivation of liberty refers to five legal categories for arbitrary detention, including one describing arbitrary detention as “[w]hen asylum seekers, immigrants or refugees are subjected to prolonged administrative custody without the possibility of administrative or judicial review or remedy.”[83] A prohibition on arbitrary detention is also found in the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families,[84] ratified by Indonesia in 2012. UNHCR emphasizes that asylum seekers and refugees have the rights to liberty and freedom of movement and that detention must only be in accordance with and authorized by law.[85]

Migrant children have a further level of protection from deprivation of liberty under international law. Article 37(b) of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) mandates that the detention of children “shall be used only as a measure of last resort and for the shortest appropriate period of time.”[86] The treaty body that interprets the CRC has stated that unaccompanied children must not be criminalized for reasons related to their immigration status or illegal entry,[87] and urges states to cease the detention of all children on the basis of their immigration status.[88] UNHCR asserts that family detention should be a last resort, when alternatives to detention are exhausted.[89]

Physical and Psychological Abuse

Immigration officials, under the Directorate General of Immigration in the Ministry of Law and Human Rights, appear to frequently beat migrants and asylum seekers in Indonesian detention facilities, according to our interviews. Of the 82 interviewees who were or had been detained, 11 reported that they had personally experienced incidents of violence, and 3 of the 11 reported multiple incidents in which they had been physically abused by immigration guards. Nineteen interviewees gave credible, detailed testimony of incidents of violence against others with whom they were detained, with one interviewee reporting multiple instances of violence against others. The experiences documented in this report, while not statistically representative of the detained population, are at least indicative of the types of abuses suffered and the lack of redress available.

Interviewees were consistent in their descriptions of the types of violence in detention facilities, describing guards kicking, slapping, and punching detainees, beating detainees with sticks and other implements, burning detainees with cigarettes, and using electroshock weapons. Some migrants reported sustaining lasting injuries. Multiple immigration officials might attack one migrant or a group of migrants in a single incident.

Unaccompanied migrant children were among those who reported brutality from immigration officials. In addition, according to our interviews, children as young as four years old have been witness to attacks, including one case in which guards forced children to watch as they beat adult migrants.

Human Rights Watch’s interviewees discussed incidents of violence between 2010 and 2011 in each of the four largest detention facilities: Belawan, Pontianak, Tanjung Pinang, and Kalideres IDCs, each of which routinely host asylum seekers, unaccompanied migrant children, and families. We also received reports from detainees of abuse in 2011 at Pekanbaru and Balikpapan IDCs; in summer 2012 at Kalideres IDC; and September 2012 at Belawan IDC. Our interviewees reported violence in informal detention facilities, during arrest, and at police stations between 2010 and 2012. A media report indicates further instances of violence at Surabaya IDC in February 2012,[90] and a support group for asylum seekers reported allegations that guards beat several Afghan men after they tried to escape from Tanjung Pinang IDC in July 2012.[91]

Despite the death following a severe beating of an Afghan migrant in Pontianak IDC in February 2012, and some limited accountability that has followed, the government has not launched a systematic review of physical abuse in the immigration detention system. Our interviewees reported instances of violence after February 2012.

In April 2013, eight migrants died in custody following a riot at the Belawan IDC near Medan,[92] creating further worries about the government’s capacity to maintain an atmosphere free of violence in the detention facilities.

International law binding on Indonesia prohibits corporal punishment and cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment in detention facilities, whether criminal or civil.[93]

Death of Asylum Seeker at Pontianak IDCOn February 28, 2012, Taqi Naroye, a 28-year-old Afghan asylum seeker previously detained at Pontianak IDC, was declared dead at a local hospital.[94] Media reports indicate that he had been bound at the wrists,[95] gagged, beaten with a piece of wood and a cable, and electrocuted the night before, while in the custody of immigration guards at the IDC.[96] On February 26, Naroye had attempted to escape from Pontianak with five other asylum seekers. He was recaptured the next day by the Pontianak police and, according to the West Kalimantan chief of immigration, was delivered back to the IDC in good health, prior to receiving the beatings that led to his death.[97]

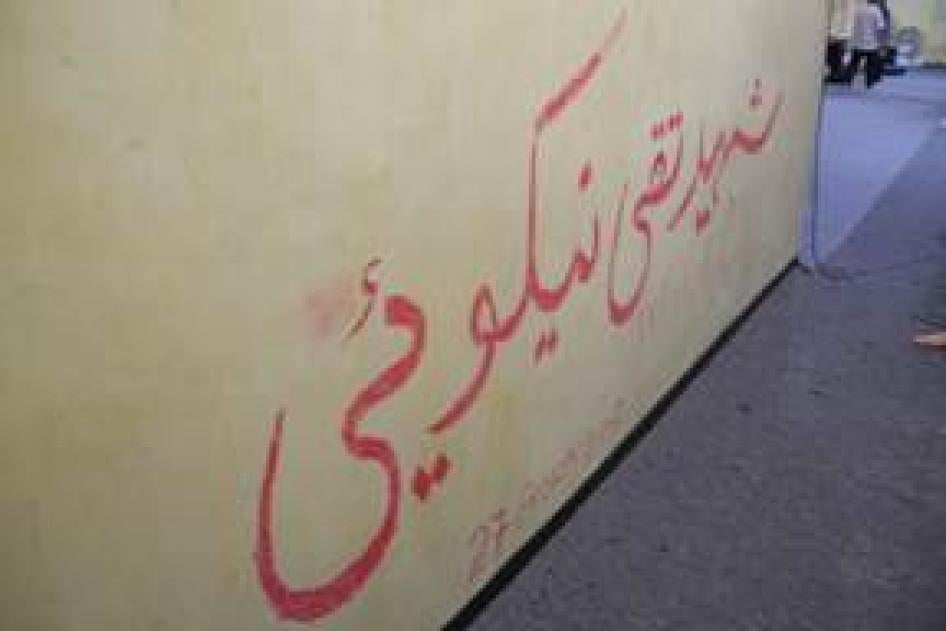

Graffiti written by Afghan detainees on a wall in Pontianak Immigration Detention Center. It reads "Shaheed Taqi Naroye" in Dari, or “Taqi Naroye, the martyr”—a reference to a 28-year-old Afghan asylum seeker who escaped from the center in 2012, was captured and returned by police, and delivered dead to a local hospital the next day. © 2012 Human Rights Watch According to UNHCR’s media reports, others who were recaptured at the same time as Naroye, including a 17-year-old unaccompanied boy, were also beaten and some were hospitalized.[98] Several migrants detained at the facility witnessed the beatings, including Mirza, another unaccompanied migrant boy, who himself was kicked by the guards during the incident.[99] At the time of our investigation, several of the guards on duty at the time no longer worked at the center, but it is not clear whether they left or were fired.[100] Ten employees of Pontianak IDC were each sentenced to ten months imprisonment for assault.[101] Yet no systemic investigation into guards’ misconduct—either at Pontianak or nationwide—had been undertaken, nor have comprehensive procedures to train immigration staff or provide a complaints mechanism for detainees been put in place. |

Children Beaten

Human Rights Watch collected accounts of multiple incidents of immigration officials beating children in detention between 2010 and 2012. Unaccompanied migrant boys told us they were beaten in detention, and adults testified that boys detained with them were beaten. One boy traveling with his family was also beaten.

Arif B. was 15 years old when he traveled to Indonesia without a parent or guardian. He said he was detained with unrelated adults at Balikpapan IDC for 1 month and 20 days in 2011, but tried to escape within the first 48 hours:

Those who were trying to escape were beaten…. Three people got away, four were caught. I was caught. That day I was beaten up very roughly…. There were eight or nine people beating me, most were guards and there was one person from the outside. They hurt my shoulder, my ear, my back. I was beaten with one of the other people who was caught.[102]

Faizullah A., an unaccompanied migrant child from Afghanistan, was 17 years old when he was detained at Pontianak IDC in 2010: “The immigration officer hit me on the face. I had gone to ask for water [to be turned on], I was shouting. He hit me two or three times. That stopped me. I was quiet then. I was crying for three or four hours after this.”[103]

A psychologist reported that one of his clients, an unaccompanied Afghan boy, was beaten in the same incident that led to Taqi Naroye’s death in 2012 (see above). Mirza,[104] who was 17 years old at the time, was in the courtyard and witness to Naroye’s beating. According to the psychologist, “the guards kicked [Mirza], his ankles, his shins, his feet, shouting at him emotionally. This was to get him away from the area of the beating.”[105] Mirza suffered severe anxiety in the months that followed (see below).[106]

Daoud T., an Afghan adult asylum seeker, said he went on a hunger strike at Belawan IDC in 2011, with several other migrants, including an unaccompanied migrant child. Many of them were beaten, said Daoud. “They even beat the 17 year old.”[107] Later testimony from detainees confirms continuing violence at Belawan. Kannan A., a 16-year-old boy detained with his family at Belawan in late 2012, reported that “immigration officers … grabbed me by my shirt and threw me into the room” after he says he was making too much noise.[108]

In all but one case reported to Human Rights Watch, immigration staff carried out the beatings. Yet in one instance in 2011 reported to us by an adult migrant, guards at Belawan forced another migrant to beat an Afghan unaccompanied child, Sadiq,[109] who was 16 years old at the time. Mohammad S., an Afghan refugee detained with Sadiq, said, “The person who beat Sadiq … was a prisoner like us, but immigration … told him, ‘You must beat this boy.’”[110] Sadiq was 16 years old at the time; Mohammad could see Sadiq’s cell and the hallway from his own cell:

[The other prisoner, who was Bangladeshi] took Sadiq to another room, with three immigration guards…. They locked the door to [the] room. The guards were still in the room while he [the other prisoner] beat Sadiq … I could hear him crying … he was beaten for 10 or 15 minutes. The next day he had black, black marks where [the other prisoner] had punched him…. Sadiq did see a doctor…. The marks stayed for three or four days…. For Sadiq, we complained to UNHCR and to IOM. All the Afghans who were living inside did. But … nothing happened.[111]

International law prohibits the use of force against children in detention except in exceptional circumstances to prevent self-injury, injury to others, and destruction of property.[112] Beating children is a serious violation of this standard.

Adults Beaten

Reports of children beaten in immigration detention are symptomatic of a larger problem. Adult migrants said they were also beaten in a number of different detention facilities, including Kalideres, Belawan, Tanjung Pinang, and Pontianak IDCs.

In 2010, Sher K., an asylum seeker who fled Afghanistan after working as a translator for coalition forces, attempted to escape from Kalideres IDC near Jakarta:

About twenty people managed to get out, but I got caught with five others. They beat us brutally. Three shifts of guards, they would each come with sticks and knives and hit us. Six or seven guards would come and beat us for fun. It lasted for three days, every day, all day. They did it for fun. One friend of mine … had a broken arm. My face was black and blue. My kidney was damaged for a month—it was bad—from the beating. We were put in a four foot by eight foot cell for six months—for six people. [113]

Ahmad Z., who said he arrived in Indonesia from Afghanistan when he was 17 years old, was 19 years old when he was detained at Kalideres IDC. He told us he was beaten and kept in a segregated cell when he was caught attempting to escape:

The [immigration] police found us…. They caught us and they beat us so badly. They punched me, they kicked me, they slapped me. Eight people each hit me. [After driving back to to Kalideres,] they took us inside and beat us more. They stomped on our food and kicked us in the stomach. Then they put us in a room with nothing. [We were] just sleeping on the floor. The next day they came and woke us up and beat us for 20 minutes…. For about six months we were locked inside of that room. No doctor visit during the six months. My friend got sick.[114]

Several migrants said that guards beat them and others at Belawan IDC, in northern Sumatra. Mohammad S., who was detained there for 14 months in 2010 and 2011, said, “ at Belawan, they beat people, many times, in front of my eyes.” [115] At the time of our interview, Daoud T. still sustained injuries from one of his beatings at Belawan, which took place in 2010:

The immigration guards beat me…. We wanted them to open the door so we could see the sky ... We staged a five-day hunger strike…. On day five, the guards slapped and kicked me. I can’t hear in my right ear because of the beating—they slapped my ear so hard.[116]

A number of interviewees who were detained at Tanjung Pinang IDC reported being beaten after being found with mobile phones or SIM cards. Nuwan D. described one incident in 2010:

One of my friends used a cellphone. He bribed a guard to buy it. Once the guards discovered him they attacked him—[including] the same officer he had gotten the phone from. They took him to a private room—three guards—and they beat him. He was burned by cigarettes, we could see this when he came out. He was 23 years old. He came out upset and injured.[117]

Ravith N. related a similar incident at the center after one of his cellmates objected to the guards’ delay in opening the gates to the recreation area: “The guard took a cigarette and burned him on his chest … the guard did this inside the guard room.”[118]

Abuse is not limited to IDCs: Migrants also reported abuses at immigration offices and police stations. After almost a month at Manado IDC, Khalid A. said he was caught while escaping with several other Afghan men, and beaten at a police station in Palu in 2010:

The police beat me. I’ve never been beaten like that before. They used electric shocks … 10 people beat us. All 10 were police. They were laughing and beating us. One had an electric shocker[119] that makes you shake…. He hit me with that maybe 20 or 25 times. I was feeling very weak. When he stopped the shocker, the other police beat me with a stick. We all cried, cried, cried. They beat me with a stick here, here, here [indicates his left elbow, knee, ankle, and shoulder]. They were telling us, “Do you want to escape next time? Do you want to escape? This time I’m beating you, next time I will kill you.”

This was in Indonesian and a little in English. I was left bruised. I had black marks in every place of my body. I couldn’t move my hand like that [indicates swinging elbow horizontally].[120]

Khalid also said immigration officers beat him when he was held at the Polonia immigration office for 11 days in 2011: “They … [p]unched me two or three times and asked why I tried to escape. If you’re illegal, you must be beaten…. It was a big guy who beat me, an immigration guy[.]”[121] Mohammad S. also said he was beaten at the Polonia immigration office when he was held there for seven days in 2010 shortly after entering the country: “The officer beat me because I didn’t want to give him my money. He said, ‘Just be quiet,’ and he beat me. ‘Give me your watch, and money, and be quiet. You’re illegal.’ He hit me. On my face, on many parts of my body.”[122] Faizullah A., who was 17 when he came to Indonesia alone, and 19 at the time of this incident, said immigration officers “grabbed me and slapped me on the face” when they re-arrested him in Medan in July 2012 and took him to the Polonia immigration office.[123]

Children Forced to Witness Violence

Among our interviewees, children of all ages were witness to harsh episodes of violence, underscoring the unsafe and unhealthy environment of detention. In one case, parents reported that immigration guards specifically forced children to watch as they beat other migrants. Media accounts confirm similar incidents in which children were exposed to violence in detention: for instance, in April 2013, multiple families were detained at Belawan IDC, when a riot broke out that left eight migrants dead and 15 injured.[124]

Arif B., a 15-year-old Afghan boy, said he was beaten on his shoulder, head, and back by “eight or nine people” he thinks were guards when detained at Balikpapan IDC in 2011. He said the incident took place “in the courtyard —everyone was there.... They saw and watched. Including one family from Iran, with a seven-year-old boy. He was watching too.”[125]

Faizullah A. was 17 years old when he was detained and learned of guards beating two other migrant who had tried to escape in separate incidents. According to Faizullah, the first “had cigarette burns over his body, on his arms and whole body [indicates torso.]” Faizullah witnessed the punishment meted out to the second escapee: “They beat him very badly. They hit him with a stick, and broke his hand.”[126] He described an atmosphere of routine intimidation and violence at Pontianak IDC during his seven-and-a-half months there: “They [immigration guards] had a stick, an electric stick. They would run it on the wall of the cage, it was very loud, like screeching…. They beat with everything—glass, boxes, anything around.”[127]

Enayet H., an 11-year-old Burmese Rohingya boy, said he was detained starting when he was 9 years old at a facility in Bandar Lampung. He told us, in English, that:

There, the police beat all people. My father, my uncle.... My father was beat, beat; my uncle was beat, beat, beat; but not me. They only beat the big people. I was the only child there. I stayed a long time.... it happened in the police room. The police were very bad in there. When people run [attempt to escape], they beat.... My father said to them, “I want to go outside, my child to study.” So the police, they beat my father.[128]

Children Forced to Watch Beatings at Pekanbaru IDCSafia and Nasir A., a couple from Afghanistan, were detained at Pekanbaru IDC for one year with their three daughters who were then 10, 6, and 4 years old.[129] They related an incident in late 2010 when immigration guards forced their family and two other families to watch as the guards beat two adult migrants: Safia said, “Ten people escaped. Two were caught by the guards, and they brought them back. They beat them like animals. The blood came from their nose, their face, all parts of their bodies. They had called all the families to watch…. My children were very scared when they saw this happen in front of them.” The beating took place, according to Nasir, in a small internal courtyard between the immigration office and his family’s cell. “Eight guards brought the two people back,” said Nasir. “They beat them in front of the three families [who were staying in the IDC at the time].” Safia reported that the immigration guards said, “See this person, don’t escape, or you will be like this.” Nasir said he attempted to intervene: “I pleaded, ‘Don’t beat them in front of my kids.’ Eventually, they let us take the kids into the room, and [the immigration guards] locked them in there. They made me go back outside [to watch].” Safia said she knew her young children could still hear the beating. “The men were crying very loudly. [The immigration guards] used electric shocks too.” |

Lack of Accountability for Violence

They [the immigration guards] didn’t have rules. We were in a cage, and they were outside.[130]

—Faizullah A., 17-year-0ld unaccompanied Afghan boy held at Pontianak IDC.

The immigration detention system appears to have no published regulations for staff behavior, nor are there clear consequences for violations of migrants’ rights. We requested, on multiple occasions, information from the Minister of Law and Human Rights (overseeing the Directorate General of Immigration) regarding procedures regulating staff behavior or providing accountability for abuse or other violations of migrants’ rights; we received no substantive response to these requests.[131]

Our own research on Indonesian domestic law and policy yielded no evidence of the existence of comprehensive regulations, and interviews with nongovernmental and intergovernmental organizations involved in providing support to asylum seekers and refugees further supports the notion that comprehensive regulations do not exist.

Intergovernmental agencies provide limited, unofficial channels of support for those subject to violence, though they do not have a mandate to monitor abuses. For instance, IOM, which provides assistance to some detainees, has no official capacity or mandate to monitor IDCs, and when staff members hear of abuses they are reported to the Directorate General of Immigration in Jakarta.[132]UNHCR has protection staff in seven locations (Medan, Tanjung Pinang, Pontianak, Makassar, Kupang, Surabaya, and Bogor) who regularly work within the IDCs,[133] but Human Rights Watch is not aware of any UNHCR mandate that would enable them to monitor the facilities.

A staff member of an NGO who spoke on condition of anonymity reported that

[I]mmigration staff employed in the IDC[s] have received little or no training on how to respond to detainees, there is a lack of guidance regarding detainees’ rights and obligations … the lack of regulations and guidelines tends to lead to choosing strict conduct as immigration staff fears to receive sanctions if detainees abscond.[134]

The staff member added that “there is no mechanism inside immigration to file complaints about violence, and there are no national standard operational procedures that could standardize simple complaint processes.”[135]

Rudy Prasetyo, an immigration officer at Pontianak, explained how new detainees learn what behavior is expected of them: “Usually one or two Afghan asylum seekers speak English, and IOM tells them the rules… sometimes it’s body language.”[136] Migrants said they were punished for a variety of offenses, including attempting escape, possessing mobile phones, going on hunger strikes, or arguing with guards.

Groups of migrants have been punished collectively. For instance, after a group of Afghan asylum seekers attempted to escape from Pontianak IDC in February 2012, other Afghan asylum seekers in the facility said they had their recreation curtailed and were no longer allowed to use mobile phones some migrants had been able to purchase. “The Myanmar and Thai people [detained in the facility] can go outside, they can have phones,”[137] said Afghan asylum seeker Nazar M. in a group interview. Zabiullah M., also Afghan, added, “[Immigration] says we can’t because we escaped. But I didn’t escape, that wasn’t me.”[138]

There is no independent monitoring body for immigration detention facilities. The Directorate General of Immigration falls under the Ministry for Law and Human Rights, which, as discussed above, does not have clear regulations for oversight of the facilities. As far as Human Rights Watch is aware, no institution has a mandate to monitor treatment of detainees by guards.

Failure to Provide for Children’s Rights

Conditions for children detained in Indonesian immigration detention facilities violate multiple international standards, leaving children without adequate care. Unaccompanied migrant children are detained with unrelated adults, and many have no contact with their families. No child has meaningful access to education, and recreation and medical care are limited. The prolonged, indefinite detention damages both adult and child mental health.

Detention of children—which should only occur in exceptional circumstances—must meet standards in the UN Rules for the Protection of Children Deprived of their Liberty.[139] These rules articulate standards for the provision of education, recreation, and medical care, among others. According to our investigations, several detention facilities in Indonesia failed to meet these standards.

Detention of Unaccompanied Migrant Children with Unrelated Adults

Unaccompanied migrant children were routinely detained in a number of immigration facilities with unrelated adults, making them vulnerable to exploitation and neglecting their need for specialized care.[140] During a visit to Pontianak IDC in September 2012, Human Rights Watch observed a boy who said he was 16 held in the same area as adult men. Many boys we interviewed reported they were detained with adults. For example, Arif B. from Afghanistan, who was 15 when he was held at Balikpapan IDC, said, “There were four people in each room. In that room, I was the only underage there. The other three were adults.”[141] Faizullah A., also from Afghanistan, was detained at Pontianak IDC:

I told the police I was 17 years old. They said “it’s no problem for us, you still go to detention.”… There were 34 or 35 other people [in my cell], all male [adults], and [one] other boy.[142]

Many adults also reported they were held with boys, including Shakairan A., a 44-year-old Tamil man, who said that while he was detained at Tanjung Pinang IDC in 2010 and 2011, “the 16 or 17 year olds lived with us, the men.”[143]

Some adult migrants said they worried about the welfare of the boys with whom they were detained. Udaya V., an adult male Tamil refugee, was detained for 10 months at Tanjung Pinang starting in 2010 and held with unaccompanied minors:

In my block there were three people under 18. They were 17 when we were there. They were just treated the same as us. The immigration officers and UNHCR, they knew they were kids. But they didn’t do anything. The boys felt stressed … They stayed with 40-year-old men, with 50-year-old men; they felt pressure.[144]

Sher K., from Afghanistan, was detained for over two years:

In Kalideres [IDC] … there were 20 or 30 unaccompanied minors. We got a weekly food supply from IOM. Boys had food stolen from them. Immigration didn’t listen; they laughed when we complained. Whenever the boys talked on the phone with their families, they would cry. The boys cried all the time. They were the most powerless in there. They would get attacked.[145]

No routine age determination is conducted in Indonesian immigration facilities. Several boys reported that officials knew their age but they remained in detention with adults anyway, suggesting that the detention of unaccompanied minors with adults did not occur from mere oversight. “They took us to the immigration office in Padang for 20-25 days,” said Ahmad Z., an unaccompanied migrant boy from Afghanistan who was 17 years old when he arrived in Indonesia. “I told the police I was 17. They just put me with the others, and treated me like the others.”[146]

Sayed M., from Afghanistan, was detained with adults at the time we interviewed him:

I’m 16 going on 17. UNHCR knows I’m here. I’ve been here for four months. I talked to UNHCR last week, I have talked to them many times…. I sleep in a room with these guys [pointing to adult men around him].[147]