Summary

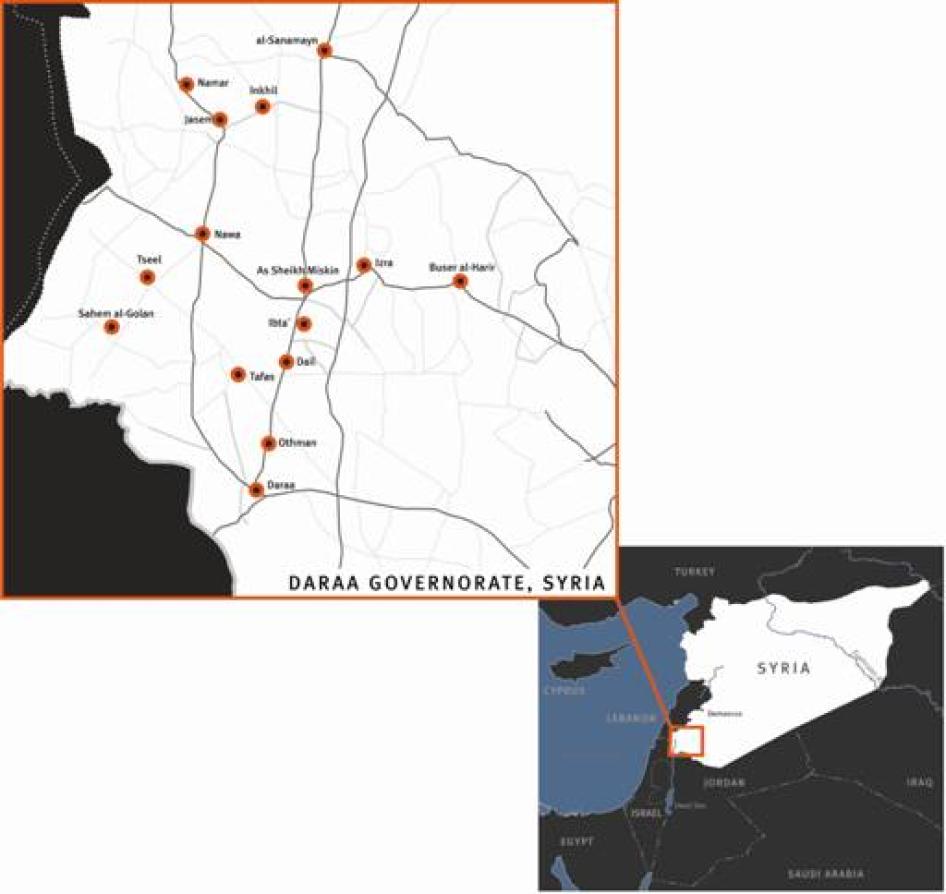

Map of Daraa Governorate

Since the beginning of anti-government protests in March 2011, Syrian security forces have killed hundreds of protesters and arbitrarily arrested thousands, subjecting many of them to brutal torture in detention. The security forces routinely prevented the wounded from getting medical assistance, and imposed a siege on several towns, depriving the population of basic services. Some of the worst abuses took place in Daraa governorate in southwestern Syria.

The nature and scale of abuses, which Human Rights Watch research indicates were not only systematic, but implemented as part of a state policy, strongly suggest these abuses qualify as crimes against humanity.

This report focuses primarily on violations by Syrian security forces in Daraa governorate from March 18 to May 22, 2011. Since the beginning of the protests in Syria, Human Rights Watch has issued numerous press releases documenting the crackdown on protesters in different parts of Syria. Obtaining information from Daraa proved most challenging as Syrian authorities put enormous efforts into ensuring that such information did not get out.

The report is based on more than 50 interviews with residents of Daraa and several Jordanian nationals who were in Daraa during the protests. Human Rights Watch also reviewed dozens of videos, filmed by the witnesses, which corroborate their accounts. Additional information was provided by Syrian activists who have been documenting the events.

The Daraa protests, which eventually spread all over Syria, were sparked by the detention and torture of 15 young boys accused of painting graffiti slogans calling for the downfall of the regime. On March 18, following Friday prayer, several thousand protesters marched from al-Omari Mosque in Daraa calling for the release of the children and greater political freedom, and accusing government officials of corruption. Security forces initially used water cannons and teargas against the protesters and then opened live fire, killing at least four.

The release of the children—bruised and bloodied after severe torture in detention—fanned the flames of popular anger. Protests continued, every week growing bigger with people from towns and villages outside Daraa city joining the demonstrations.

The Syrian authorities promised to investigate the killings, but at the same time denied any responsibility and blamed the violence on “terrorist groups,” “armed gangs,” and “foreign elements.” In the meantime, security forces responded to the continuing protests with unprecedented brutality, killing, at this writing, at least 418 people in the governorate of Daraa alone, and more than 887 across Syria. Exact numbers are impossible to verify given the information blockade imposed by the Syrian government.

Some of the deadliest incidents that Human Rights Watch has documented in this report include:

- An attack on al-Omari mosque (which had become a rallying point for protesters and served as a makeshift hospital for the wounded protesters) and ensuing protests from March 23 to 25, 2011, which resulted in the killing of more than 30 protesters;

- Killings during two protests on April 8, 2011, which resulted in the deaths of at least 25 victims;

- Killings during a protest and a funeral procession in Izraa on April 22 and 23, 2011, which claimed the lives of at least 34 protesters;

- Killings during the siege of Daraa and neighboring villages (starting on April 25 and ongoing in certain towns) and killings at an April 29, 2011 protest, during which residents of neighboring towns tried to break the siege, which claimed up to 200 lives.

Witnesses from Daraa interviewed by Human Rights Watch provided consistent accounts of security forces using lethal force against peaceful protesters. In some cases, security forces first used teargas or fired in the air, but when protesters refused to disperse, they fired live ammunition from automatic weapons into the crowds. In most cases, especially as demonstrations in Daraa grew bigger, security forces opened fire without giving advance warning or making any effort to disperse the protesters by nonlethal means.

Security forces deliberately targeted protesters, who were, in the vast majority of cases, unarmed and posed no threat to the forces; rescuers who were trying to take the wounded and the dead away; medical personnel trying to reach the wounded; and, during the siege, people who dared to go out of their houses or to gain access to supplies. In some cases they also shot bystanders, including women and children.

From the end of March, witnesses consistently reported the presence of snipers on government buildings near the protests, targeting and killing protesters. Many of the victims sustained head, neck and chest wounds, suggesting that they were deliberately targeted.

Other evidence obtained by Human Rights Watch also suggests that security forces participating in the operations against the protesters (in Daraa and other cities) had received, at least in a number of cases, “shoot-to-kill” orders from their commanders.

Security forces who participated in the crackdown in Daraa included several army units, as well as various branches of Syria’s mukhabarat (intelligence services). Several witnesses noted that most of the violence was perpetrated by mukhabarat forces and elite army units such as the 4th Division which reports directly to Maher al-Asad, the younger brother of President Bashar al-Asad. On several occasions army units deployed to quell the protests seemed reluctant to shoot at protesters, allowed them to pass through checkpoints, and, in at least two cases documented by Human Rights Watch, refused orders to shoot and either surrendered to the protesters or handed over their weapons to the protesters.

Syrian authorities repeatedly blamed the protesters in Daraa for initiating the violence and attacking security forces. On several occasions, starting in late March, after security forces first used lethal force against the demonstrators, Daraa residents resorted to violence. For example, they set several building on fire, including the governor’s house, and the political security building, as well as vehicles belonging to the security forces, and on several occasions killed members of the security forces.

At the same time, all witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that the protests started peacefully, with demonstrators often carrying olive branches, unbuttoning their shirts to show that they had no weapons, and chanting “peaceful, peaceful” to indicate that they posed no threat to the security forces. Dozens of videos of the Daraa protests that witnesses provided to Human Rights Watch as well as those posted online corroborate these accounts. Witnesses said that protesters only used violence against the security forces and government property in response to killings by the security forces or, in some cases, as a last resort to secure the release of wounded demonstrators captured by the security forces.

The incidents of violence by the protesters should be further investigated and the perpetrators brought to justice. However, these incidents by no means justify the massive and systematic use of lethal force against the demonstrators, which was clearly disproportionate to the threat presented by the overwhelmingly unarmed crowds.

Syrian authorities also routinely denied wounded protesters access to medical assistance. In at least two cases documented by Human Rights Watch (and reportedly in many others), this denial of medical assistance led to the deaths of wounded persons who might otherwise have survived.

Witnesses told Human Rights Watch that security forces regularly prevented ambulances from reaching the wounded and, on several occasions, opened fire as medical personnel were trying to reach the injured. They also prevented people from carrying away the wounded and, in several cases documented by Human Rights Watch, shot at and killed the rescuers. Security forces took control of most of the hospitals in Daraa and detained the wounded who were brought in. As a result, many wounded avoided the hospitals and were treated in makeshift hospitals with limited access to proper care.

Since late March, and particularly after Daraa came under siege on April 25, security forces launched a massive campaign of arrests in the governorate. Witnesses from Daraa city and neighboring towns described to Human Rights Watch large-scale sweep operations conducted by security forces who daily detained hundreds arbitrarily, as well as targeted arrests of activists and their family members. Some detainees, many of whom were children, were released several days or weeks later, while others have not reappeared. In most cases their families have no information on their fate or whereabouts.

The majority, if not all, of the arrests seemed entirely arbitrary with no formal charges ever brought against the detainees. People arrested in Daraa were initially held in various ad hoc detention facilities before being transferred for interrogation in military intelligence or political security departments in Daraa. Many were then sent to Damascus.

Released detainees interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that they, as well as hundreds of others they saw in detention, were subjected to various forms of torture and degrading treatment. The methods of torture included prolonged beatings with sticks, twisted wires, and other devices; electric shocks administered with tasers and electric batons; use of improvised metal and wooden “racks”; and, in at least one case documented by Human Rights Watch, the rape of a male detainee with a baton. Interrogators and guards also subjected detainees to various forms of humiliating treatment, such as urinating on the detainees, stepping on their faces, and making them kiss the officers’ shoes. Several detainees said they were repeatedly threatened with imminent execution.

All of the former detainees described appalling detention conditions, with grossly overcrowded cells, where at times detainees could only sleep in turns, and lack of food.

Two witnesses (both former detainees) independently reported to Human Rights Watch a case of an extrajudicial execution of detainees on May 1, 2011 at an ad hoc detention facility at the football field in Daraa. One of the two witnesses said the security forces executed 26 detainees; the other one described a group of “more than 20.”

The majority of witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch also referred to the existence of mass graves in Daraa. On May 16, Daraa residents discovered at least seven bodies in one such grave about 1.5 kilometers from Daraa al-Balad. Five bodies were identified as members of the Abazeid family. Syrian government officials denied the existence of a mass grave, but al-Watan, a Syrian newspaper closely affiliated with the government, acknowledged that five bodies had been found.

On April 25, 2011, Syrian security forces launched a large-scale military operation in Daraa and imposed a siege which lasted at least 11 days and was then extended to neighboring towns. Daraa residents told Human Rights Watch that security forces moved into the city in military vehicles, including numerous tanks and armored personnel carriers. Under the cover of heavy gunfire they occupied all neighborhoods in Daraa, imposed checkpoints, and placed snipers on roofs of buildings in many parts of the city. They prevented any movement of residents in the streets. The security forces opened fire on those who tried to defy the ban on movement and gatherings, or simply went out of their homes in search of food or medication.

Witnesses said that Daraa residents experienced acute shortages of food, water (because security forces shot and damaged water tanks), medicine, and other necessary supplies during the siege. Electricity and all communications were cut off for at least 15 days, and, at the time of this writing, remained cut off in several neighborhoods in the city.

From April 25, 2011 until at least May 22, 2011, Daraa residents were not allowed to pray in mosques and all calls for prayer were banned. Security forces occupied all of the mosques in the city and, according to witnesses who saw the mosques after they reopened, desecrated them by writing graffiti on the walls.

As the killings continued during the Daraa siege, residents also struggled with the growing number of dead bodies. Due to the lack of electricity, the bodies could not be stored in morgues, and restrictions on movement and communications placed obstacles to identification and burials. As a result, Daraa residents stored dozens of bodies in mobile vegetable refrigerators that could run on diesel fuel. These were subsequently confiscated by the security forces who then returned at least some of the bodies to the families.

Syrian authorities also imposed an information blockade on Daraa to ensure that abuses were not exposed. No independent observers could enter the city and one international journalist who managed to report from Daraa during the first two weeks of protests in March was arrested upon his return to Damascus. During the siege all means of communication were shut down, including Syrian cell phone networks. Many witnesses told Human Rights Watch that cell phones were the first thing authorities confiscated during searches in their houses or at checkpoints. They were specifically looking for footage of the events and arrested and tortured those whom they suspected of trying to send out images or other information out, including some foreign nationals.

Human Rights Watch called on the Syrian government to immediately halt the use of excessive and lethal force by security forces against demonstrators and activists, release unconditionally all detainees held merely for participating in peaceful protests or for criticizing the Syrian authorities, and provide immediate and unhindered access to human rights groups and journalists to the governorate of Daraa, as well as hospitals, places of detention, and prisons. It also called on the Security Council to push for and support efforts to investigate and prosecute those responsible for the grave, widespread, and systematic human rights violations committed in Syria since mid-March 2011, and adopt targeted financial and travel sanctions on those officials responsible for continuing human rights violations.

Note on Methodology

This report is based on more than 50 interviews with Daraa residents and several Jordanian nationals conducted in person and over the phone in April and May 2011. Dozens of other interviews with witnesses in other parts of Syria were used for the chapter setting the context of the anti-government demonstrations in Syria. Additional information was provided by Syrian activists who have been documenting the events.

Human Rights Watch also reviewed dozens of videos filmed by the witnesses and interviewed them about the content.

The interviews were conducted by Arabic-speaking researchers or with the help of Arabic-English translators.

Daraa has been and remains under information blockade and obtaining information from the governorate is extremely difficult. Those who speak to foreigners or try to share the information through electronic means may face severe repercussions, and Human Rights Watch researchers had to exercise caution while collecting and publicizing the information. To protect the witnesses, many of the names of witnesses in this report have been changed or withheld, as well as places where the interviews took place.

In this report Human Rights Watch only used information that contained sufficient detail and was corroborated by several witnesses interviewed independently or by video footage filmed by the same witnesses Human Rights Watch interviewed. We excluded dozens of other accounts and allegations which we could not verify.

Human Rights Watch compiled the list of people who had been killed during protests based on information provided by local activists. While we did our best to verify the names and circumstances of the killings with witnesses and family members, this was not always possible due to restrictions on access and communications in Syria.

I. Timeline of Protest and Repression in Syria

Syria, a repressive police state ruled under an emergency law since 1963, at first seemed immune to the popular uprisings that swept the Arab world starting December 2010. Protests began in February, but failed to attract crowds large enough to outnumber the ever present security forces.

The situation changed in mid-March, when thousands of people took part in anti-government demonstrations in the city of Daraa, located in the southern Hauran region near the Jordanian border.[1]Protests broke out on March 18 in response to the arrest and torture by political security, a branch of Syria’s notorious mukhabarat, or security services, of 15 school children (see below). Security forces opened fire, killing at least four protesters and within days the protests grew into rallies that gathered thousands of people.

On March 19 the state news agency Syrian Arab News Agency (SANA) reported that the Ministry of the Interior would form a committee to investigate the “unfortunate incidents” in Daraa, and would respond with “all measures deemed necessary” after the committee's investigation.[2] On March 20, the government sent a delegation of high-ranking officials to Daraa, including General Rustum Ghazali, a leading figure in Syrian security services, stating they would try to assure tribal leaders that those who had opened fire on protesters would be brought to justice.[3]

Yet, as the protests continued over the following days and spread to nearby towns of Jassem, Da`el, Sanamein, and Inkhil, the security forces demonstrated increasing brutality in their efforts to quell the demonstrations, killing and wounding more and more protesters (see below).

The Syrian government-controlled media denied the security forces’ role in the violence, blaming it on “instigators,” “armed gangs,” and “foreign elements.”[4]As the death toll mounted in Daraa, protests spread across Syria. On March 26, protesters and security forces clashed in the port city of Latakia in northwestern Syria, resulting in at least 12 deaths.[5]

On March 30, President Bashar al-Asad addressed the nation. Speaking before parliament, al-Asad pledged to enact ill-defined “reforms,” but did not provide any specific details and continued to blame the unrest on foreign conspirators.[6] The next day, he launched a probe into deaths in Daraa and Latakia and established a committee to study the lifting of emergency law. However, in what would become a familiar pattern, reform promises by President al-Asad were accompanied by more repression, as security forces carried out mass arrests of activists and journalists, including two journalists working for Reuters international news agency.[7]

On April 1, a Friday, protesters turned out by the thousands in several towns and cities including the capital, Damascus. At least eight demonstrators and possibly as many as fifteen were killed that day when men dressed in civilian clothes opened fire at a largely peaceful anti-government protest in the Damascus suburb of Douma.[8] Meanwhile in Daraa, people from neighboring villages attempted to enter the city, but were met with heavy fire at military blockades, especially on the roads from Sanamein and Inkhil.

This was the first of what became weekly mass anti-government demonstrations across Syria.[9] The following week, on April 8, protests continued in Daraa, Baniyas, Homs, Latakia, Tartus, Idlib, the Damascus suburb of Harasta, and the largely Kurdish northeastern city of Qamishli. In Daraa, residents of neighboring villages passed through the blockades at the city's entrances, burned posters and statues of Syria’s leaders, and converged on the offices of political security. Security forces opened fire on the protesters, killing at least 27 people. Another protester died in Douma. Human Rights Watch documented that Syrian security forces prevented medical personnel and others from reaching wounded protesters that day in Douma and in Harasta.[10]

On April 15, thousands of protesters tried to enter Damascus from Douma and other outlying suburbs, but security personnel fired on them and forced them back.

In addition to shooting protesters, security forces continued their campaign of mass arrests, arbitrarily detaining hundreds of protesters across the country, and subjecting them to torture and ill-treatment. The security and intelligence services also arrested lawyers, activists, and journalists who endorsed or reported on the protests.

By April 15, Human Rights Watch had interviewed 19 people who had been detained in Daraa, Damascus, Douma, al-Tal, Homs, and Banyas. All but two of the detainees arrested during the protests told Human Rights Watch that members of the mukhabarat (security services) beat them while arresting them and in detention, and that they witnessed dozens of other detainees being beaten or heard screams of people being beaten. Three of the victims interviewed by Human Rights Watch were children who reported that they were beaten. Other former detainees also reported seeing children detained and beaten in the facilities where they were held.

Witnesses told Human Rights Watch that they and other detainees were subjected to various forms of torture, including torture with electro-shock devices, cables, and whips. Most also said they were held in overcrowded cells and many said they were deprived of sleep, food, and water, in some cases, for several days. Some said they were blindfolded and handcuffed the entire time.[11]

On April 21, President al-Asad issued decrees to lift the state of emergency (decree no. 161), to abolish the state security court (decree no. 53), and to recognize and regulate the right to peaceful protest (decree no. 54).[12]

But government forces continued to violently suppress protests, killing at least 110 other protesters who participated in mass gatherings across the country on April 22, in what was the deadliest day of protests. Those killed included at least 30 in the town of Izraa, 23 in the Homs area, and 29 in the Damascus area. Three boys, aged 7, 10, and 12, were among those killed in Izraa, as was a 70-year-old man. Video footage posted on YouTube shows a number of the wounded and killed protesters, including one of the dead children, right after they came under heavy gunfire.[13]

The next day, on April 23, security forces fired on funeral processions in Barza, Douma, and Izraa, killing at least 12 mourners.

As protests continued, security forces launched large-scale military operations on towns and neighborhoods identified as hubs of protests. On April 25, security forces and military vehicles moved into the city of Daraa using military vehicles, including numerous tanks and armored personnel carriers (APCs), under a cover of heavy gunfire that lasted unabated for about 16 hours (see below for more details). The security forces occupied all neighborhoods in Daraa, imposed checkpoints, and placed snipers on the roofs of buildings in many parts of the city. They imposed a siege on the city, cut off electricity and all means of communications, and prevented any movement by opening fire on anyone who tried to leave their house. Once they had established full control of the city, the security forces then proceeded to arrest hundreds of men from their homes (see below).

This pattern would be repeated in a number of places, with varying degrees of military involvement. Security forces surrounded Douma, a suburb of Damascus that was the scene of large anti-government protests, in the early hours of April 25, deployed a heavy security presence in each neighborhood, set-up checkpoints, and proceeded to raid homes, arresting dozens of men.[14] On May 1, the army surrounded Zabadani, a town of approximately 40,000 residents near Damascus, a day after thousands of protesters had marched to the neighboring town of Madaya. The army posted snipers on rooftops and proceeded to arrest many of those who had participated in anti-government protests. A Zabadani activist told Human Rights Watch that the security forces detained 98 men from the town that day, releasing 28 of them on May 3. Most of those released reported being beaten during detention at a security facility on Baghdad Street in Damascus.[15]

On May 6, the army and the security services, using armored vehicles and tanks, surrounded the coastal town of Banyas and the neighborhoods of Bab al-Sba` and Baba Amr in Homs, Syria’s third largest city. A Banyas resident said that the army used 57 armored vehicles to surround the town, and entered under cover of heavy gunfire. Over the next few days the security forces would detain hundreds of boys and men from Banyas.[16] In the early hours of May 7, the security forces stormed the Baba Amr neighborhood in Homs, destroying a number of shops and homes, and killing several residents, including a mother and her two children, local activists reported.

By May 12, army and security forces had deployed military vehicles, including tanks, in Da`al, Tafas, Inkhil, al-Hara, and Jasem, all towns neighboring Daraa, and proceeded to carry out mass arbitrary arrests of suspected protesters. On May 19, the army also entered the nearby towns of Sanamain, al-Harak, and Kfar Shams.

Meanwhile the arrest and intimidation of political and human rights activists continued.[17] For example, on May 12, security forces in Homs detained Muhammad Najati Tayyara, a prominent human rights activist who frequently appeared in the media to provide information on Syria's crackdown on protests. Security forces picked him up off the streets of Homs, a friend of Tayyara told Human Rights Watch, and have not provided any information on his whereabouts since then.

In some cases the security forces resorted to detaining relatives and neighbors of government critics, in an effort to obtain information on their whereabouts or force them to stop their activism. For example, on May 11, security forces detained Wael Hamadeh, a political activist and husband of prominent rights advocate Razan Zeitouneh, from his office. The security forces had gone to the couple's house on April 30 searching for them but detained instead Hamadeh's younger brother Abdel Rahman, 20, when they could not find them.[18]

As this report went to print on May 31, Syrian protesters were still demonstrating and security forces continued their violent crackdown. On May 25, security forces returned the body of 13-year-old Hamza Ali al-Khatib to his family in Jeeza, near Daraa, bearing what appeared to be signs of torture. He had been injured and detained weeks earlier while attempting to bring food to Daraa.[19] His death and reported torture rallied protesters across Syria on Friday May 27.[20] The National Organization for Human Rights in Syria reported that security forces shot and killed 11 protesters that day, including a 15-year-old child in Idlib.[21]

Security forces killed five people on May 28 in Da`el, near Daraa, and conducted raids in the nearby town of al-Harek, arresting hundreds of young men.[22] At dawn on May 29, military forces with tanks stormed the Homs-area towns of Rastan, Talbiseh, Deir Ba`albeh, and Teir Ma`alleh, shelling and firing machine guns at homes and residents, killing 11 people, according to human rights lawyer Razan Zeitouneh.[23]

II. Crimes against Humanity and Other Violations in Daraa

Situated in the southwestern part of the country on the border with Jordan, Daraa is one of fourteen Syrian governorates or provinces. With less than a million people, it is divided into three districts, al-Sanamayn, Daraa, and Izraa. The provincial capital, also called Daraa, has a population of about 80,000.

It was in Daraa that the anti-government protests that have spread all over Syria since mid-March started. Initial protests were sparked by the detention and torture of 15 boys, ages 10 to 15, accused of painting graffiti slogans calling for the downfall of the regime. For days, the boys’ families pleaded for their release with the authorities and with General Atef Najeeb who was in charge of the local political security department in Daraa where the boys were held. Then the residents of Daraa took to the streets.

On March 18, following the Friday prayer, several thousand protesters marched from al-Omari Mosque in Daraa calling for the release of the children and greater political freedom, and accusing government officials of corruption. According to multiple witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch, security forces at first attempted to beat the protesters back with stones and batons. Later riot police were deployed with water cannons and teargas, and finally members of political security branch of the mukhabarat or security services showed up and opened fire on demonstrators using live ammunition. [24]At least four protesters were killed that first day, and several dozen injured.

The release of the children—bruised and bloodied after what they described as severe torture in detention—fanned the flames of popular anger. Protests continued, every day growing bigger, joined by people from towns and villages outside Daraa city.

Security forces responded to the protests with increasing brutality. As this report describes in detail, they have systematically opened fire on overwhelmingly peaceful crowds during demonstrations and funeral processions, killing, at this writing, at least 418 people in the governorate of Daraa alone, and wounding hundreds more. The security forces routinely prevented the wounded from getting medical assistance in a number of instances, and subjected thousands of people to arbitrary arrests and brutal torture in detention. When none of these measures succeeded in quelling the protests, Syrian authorities launched a large-scale military operation in Daraa at the end of April, put the city under military control, and imposed a siege on the city, preventing movement not only in and out of the city but also within it, and depriving the residents of basic services. Later the security forces extended these siege tactics to nearby towns.

Human Rights Watch believes that the nature and scale of abuses committed by the Syrian security forces, the similarities in the apparent unlawful killings and other crimes, and evidence of direct orders given to security forces to ‘shoot-to-kill’ protestors, strongly suggest these abuses qualify as crimes against humanity.

Under customary international law and the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, crimes against humanity are certain acts, including murder, torture, and other inhumane acts, committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack against a civilian population.[25]

Unlike war crimes, crimes against humanity can also be committed during times of peace, if they are part of a widespread or systematic attack against a civilian population.[26]

The Rome Statute defines an “attack against a civilian population” as “a course of conduct involving the multiple commission of [acts such as murder or other possible crimes against humanity] against any civilian population, pursuant to or in furtherance of a State or organizational policy to commit such attack.”[27]

For individuals to be found culpable of crimes against humanity, they must have had knowledge of the crime.[28] That is, perpetrators must have been aware that their actions formed part of the widespread or systematic attack against the civilian population.[29] While perpetrators need not be identified with a policy or plan underlying crimes against humanity, they must at least have knowingly taken the risk of participating in the policy or plan.[30]

Individuals accused of crimes against humanity cannot avail themselves of the defense of following superior orders.[31] At the same time, those in a position of military or other command can be held criminal responsible for failing to prevent crimes against humanity by those under their command, or to submit the matter for prosecution when they knew or should have known about the crimes.[32] Because crimes against humanity are considered crimes of universal jurisdiction, all states are responsible for bringing to justice those who commit crimes against humanity. There is an emerging trend in international jurisprudence and standard setting that persons responsible for crimes against humanity, as well as other serious violations of human rights, should not be granted amnesty.

Evidence collected by Human Rights Watch also suggests that Syrian security forces have been responsible for a wide range of other violations, including extrajudicial executions, massive arbitrary arrests, denial of medical assistance to the wounded, and imposing a siege which deprived a civilian population of basic services. Applicable legal standards are discussed in the sections below.

Systematic killings of protestors and bystanders

Human Rights Watch’s research has established that since March 18, 2011 and to this writing Syrian security forces have committed systematic killings in Daraa governorate. They deliberately targeted protesters, who were in the vast majority of cases unarmed and posed no threat to the forces; rescuers who were trying to take the wounded and the bodies away; medical personnel trying to reach the wounded; and, during the siege, people who dared to go out of their houses or to enter the city with supplies. In some cases, they also shot bystanders, including women and children.

While witness testimonies leave little doubt regarding the extent and systematic nature of abuses, the exact number of people killed and injured by Syrian security forces in Daraa is impossible to verify. The city remains largely cut off from the outside world and people who try to get information out face severe repercussions (see below). Thousands of families, according to local residents, have no information about their missing relatives and do not know whether relatives have been arrested or killed.

Local activists have been maintaining lists of people killed during the protests throughout Syria. Human Rights Watch compiled its own list after checking two separate lists that different local activists provided. As of May 29, the listed stood at 887 killed and included the names of at least 418 residents of Daraa governorate.

More than 50 witnesses from Daraa interviewed by Human Rights Watch provided consistent accounts of security forces using lethal force against protesters during demonstrations, funeral processions, and when people from surrounding villages tried to enter the city to join the demonstrations or participate in the funerals of those killed. In some cases, security forces first used teargas or fired in the air, but when the protesters refused to disperse, they fired live ammunition from automatic weapons into the crowds. In most cases, especially as demonstrations in Daraa grew bigger, security forces opened live fire without giving advance warning or making any effort to disperse the protesters by nonviolent means.

From the end of March witnesses consistently reported the presence of snipers on government buildings near the protests who targeted and killed many of the protesters. Many of the victims, as described by witnesses to Human Rights Watch and pictured on scores of cell phone videos smuggled out of Daraa, sustained head, neck, and chest wounds, suggesting that they were deliberately targeted.[33]

Other evidence obtained by Human Rights Watch also suggests that the security forces participating in the operations against the protesters in Daraa and other cities, had received, at least in a number of cases, “shoot-to-kill” orders from their commanders. Human Rights Watch interviewed a soldier from the presidential guard who deserted after the unit was deployed to deal with a demonstration in the city of Harasta on April 18, 2011. The commanders, the soldier said, initially told them that they were being deployed to deal with “armed militias,” yet what they saw upon arrival to Harasta was a peaceful demonstration. Nonetheless, the soldier said that they received “clear orders to shoot, with no conditions or prerequisites; literally – to ‘load and shoot.’”[34]

Another witness, a resident of Daraa, described to Human Rights Watch an episode when together with a group of other protesters he managed to briefly capture several members of political security branch of the security services (see below). According to the witness, the captured security men said they “were only following orders and their orders were to kill, not to take prisoners,” and added that they could not surrender to the protesters as they “would have been killed by their commanders if they refused to shoot.”[35]

Security forces who participated in the crackdown in Daraa included several army units (witnesses specifically referred to the 4th Division under the command of Maher al-Asad, President al-Asad’s brother), as well as various branches of Syria’s mukhabarat (security services).

Witnesses said that the majority of security forces wore green military camouflage, but that they eventually learned how to distinguish members of different branches of the mukhabarat by the colored stripes on their uniform. One witness told Human Rights Watch that members of military intelligence wear a green stripe, air force intelligence a white stripe, state security a yellow stripe, and the presidential guard a black stripe, while political security often wore plain black uniforms.[36] Witnesses also said that in some cases mukhabarat members wore civilian clothes.

According to witnesses, some of the security forces, in black uniforms, were equipped with riot-control and other special gear, including bulletproof vests, helmets, shields, and night-vision goggles. Snipers also wore black uniforms. Some of the forces were from Daraa, while others were brought in from other regions by helicopters and buses.

Several witnesses independently told Human Rights Watch that most of the violence was perpetrated by mukhabarat forces, while army units on several occasions seemed reluctant to shoot at protesters, allowed them to cross through checkpoints, and, in at least two cases described in detail to Human Rights Watch, refused orders to shoot and either surrendered to the protesters or handed over their weapons (see below).

The information about the command structure of Syrian military and intelligence services is limited. According to public sources, some of the officials in charge of the forces that reportedly participated in the crackdown on protesters include:Maher al-Asad, the president’s younger brother who heads the Presidential Guard and the Fourth Armored Division; Ali Mamluk, head of Syrian general intelligence directorate; Abdul Fattah Qudsiyeh, head of military intelligence; Jamil Hassan, head of airforce intelligence; Muhammad Dib Zaytun, head of political security directorate; Rustum Ghazali, head of the Damascus countryside branch of Syrian military intelligence; Hisham Ikhtiar head of the Syrian National Security Bureau; Muhammad Ibrahim al-Sha`ar, Minister of Interior; Dawud Rajiha, chief of staff of the armed forces; Asef Shawkat, deputy chief of staff of the armed forces responsible for Security and Reconnaissance; Ali Habib Mahmoud, minister of defense, Zuhair Hamad, deputy head of general security directorate; Muhammad Nasif Khayrbik, deputy vice-president of Syria for national security affairs; Atef Najib, the head of Political Security in Daraa at the beginning of the crackdown.[37]

Witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch also indicated that the officials present in Daraa during the operation included Hisham Bakhtiyar (Ikhtiar), Ali Mamluk, Rustum Ghazali, and Colonel Lo’ay Al-Ali, head of military intelligence in Daraa. Some released detainees said they had been personally interrogated by these officials at their temporary headquarters in Daraa (see below).

Some of the deadliest attacks documented by Human Rights Watch are described below.

Killings during attack on al-Omari mosque and protests that followed, March 23-25, 2011

From March 23 to 25, 2011, Syrian security forces killed at least 31 people during an attack on Daraa’s al-Omari mosque, which had become a rallying center for protesters and served as a makeshift hospital for the wounded protesters. The attack started shortly after midnight on March 23. Several witnesses who were in the neighborhood at the time of the attack, or later came to support the protesters inside the mosque, told Human Rights Watch that they heard gunfire at around 12:20 a.m. on March 23 and saw security forces near the mosque firing at people who were trying to approach. One of the witnesses, “Omar” (not his real name), said that there were about 60 people inside the mosque yard that night, waiting for the return of a delegation of tribal leaders who had gone to Damascus to discuss the protesters’ demands with officials. Omar said:

Shortly after midnight, all electricity was cut off, and security forces moved toward the mosque. They were shooting into the mosque yard through three entrances. It was panic and people were running away. Through loudspeakers people in the mosque called for support. I was nearby and ran toward the mosque along with many others.

We did not believe they would attack the mosque. We heard gunfire, but I did not think those were live bullets. I thought they were blanks. But then a bullet hit my neighbor just next to me. His name was Ayman Yasin Qteifam. He was 21 years old. We were some 30 or 40 meters from the mosque when a bullet hit him in the chest. He died on the spot. I pulled his body away and put it next to the wall and later on, when the fire stopped, started helping to collect other bodies. There were eight bodies altogether. Two of the people were killed inside the mosque (we only found them next morning), and six others killed when they tried to approach the mosque.[38]

Another witness, a non-Syrian national who was in Daraa at the time of the attack, said that a member of the family he was staying with, a 17-year-old boy, was shot in the leg as he tried to approach the mosque that night.[39]

The following day Daraa residents buried the dead, and at around 5 p.m. the funeral procession grew into another protest, joined by the people from surrounding villages. Omar said that security forces opened fire again without warning and killed 11 people. Omar was part of the team that was documenting the events in Daraa, photographing all the bodies and later collecting the names of those who were killed.

The next day, March 25, 2011, Daraa residents and people who kept coming to Daraa from neighboring towns launched another Friday protest. One of the witnesses, “Abdallah” (not his real name), a mathematics teacher from Daraa city, who was taking part in the protest, told Human Rights Watch:

There were snipers on the governor’s headquarters and other official buildings. Other security forces, who were in the streets, first fired in the air, but the snipers were shooting straight into the crowd. We started running away and we were jumping over the bodies. Whoever tried to get the bodies or rescue the wounded got shot at.

Next day, when we counted the bodies that the security forces had taken and then released and those the people managed to carry away, we realized that 31 people were killed.[40]

Another witness, “Saleh” (not his real name), who came to Daraa from Tseel, a village three kilometers northwest of Daraa, confirmed this account. He said that when the group of protesters he was part of was about 100 meters away from the roundabout near the governor’s building, snipers opened fire on the crowd. He said that some demonstrators who arrived there earlier were trying to topple the statue of the late president Hafiz al-Asad, and at that point security forces opened heavy fire. He personally saw at least seven dead bodies of the demonstrators.[41]

Killings during two protests on April 8, 2011

On April 8, after the noon prayers, hundreds of protesters gathered in two parts of Daraa city divided by a bridge: Daraa al-Balad and Daraa al-Mahata.

Several thousand protesters started marching from Shaikh Abd al Aziz mosque in Daraa al-Mahata toward the bridge leading to the other part of the city, Daraa al-Balad. According to one of the protesters, “Ahmed” (not his real name), people were carrying olive branches to symbolize their peaceful intentions.

According to Ahmed, security forces set up a roadblock near the bridge to prevent the protesters from crossing to the other part of the city. He said there were about 50 soldiers in front of them, several thousand mukhabarat agents, both in uniforms and in civilian clothes, behind and around them, and snipers on the roofs of nearby buildings. Around 1:30 or 2:00 p.m. the protesters reached the road leading to the bridge and walked toward the roadblock. Ahmed said the army told them to stop, but they did not obey and continued moving, and at that point security forces opened live fire. Ahmed, who was also filming the events, said that they fired straight into the crowd with Kalashnikovs, and snipers opened fire at the same time. He said he personally saw about 35 people who immediately fell, hit by bullets. At that time he did not know whether they were injured or killed, but later that day he saw the bodies of about 20 killed protesters as well as dozens of wounded in al-Omari mosque.[42]

Ahmed said that security forces also ran after the protesters, grabbing some and dragging them into their cars, and beating others. He said:

I saw one man—he was hit by three bullets, and fell on the ground. He was clearly dead. The security forces ran toward him, and, although he was already dead, started beating him with sticks on the face. Nobody could stop them, and when we finally managed to retrieve the body, it was unrecognizable—we could only identify the man because he had his civil identification card in his pocket.

Another witness told Human Rights Watch that around the same time, after the afternoon prayers, another group of protesters marched from al-Omari mosque towards the bridge, intending to join the protesters from Daraa al-Mahata. As they were trying to cross the bridge, security forces from the same roadblock first fired tear gas, and then opened live fire at them. The witness said he saw three people who were hit by the bullets and carried into al-Omari mosque. As he followed them to al-Omari mosque, he saw about ten wounded protesters there, three of whom died from their wounds while he was in the mosque.

Two other witnesses also told Human Rights Watch that later that day a group of protesters marched toward the political security department in Daraa to request the release of protesters arrested during the demonstration. He said that when the protesters tried to break into the yard of the political security building, snipers opened fire, killing at least four people.[43]

Killings during a protest and a funeral procession in Izraa, April 22-23, 2011

Several witnesses from the towns of Tseel and Tafas, described to Human Rights Watch a series of killings that happened on April 22 and 23, 2011 near Izraa, a town of 40,000 residents near Daraa.

“Abdul-Karim” (not his real name), a resident of Tseel, told Human Rights Watch that on April 22, 2011, he and other residents heard that 11 people were killed during a protest in Izraa, and decided to go there to support the demonstrators. He said:

At around 3 p.m. we reached a bridge close to Izraa which was closed by checkpoints on both sides. They let us through the first checkpoint and then trapped us on the bridge, not letting us through. We were about 300-400 people on the 70-meters-long, 9-meters-wide bridge. As we were trapped in the middle, security forces opened fire—not from the checkpoints; it came from the side. The shooters were from mukhabarat—they had camouflage uniforms with yellow and red straps on their shoulders, looked older than the army soldiers, and their uniforms were newer and fitted them well.

I saw a 7-year-old boy hit in the head right next to me (I later leant that he was from Namer, his name was Muhammad Ibrahim Hamoudeh), and three other young men—they were all hit in the head and died on the spot. About 20 people were wounded—we managed to carry them all away.[44]

The following day, people from different neighboring towns went to Izraa to participate in the funerals of the protesters killed on April 22. One of the witnesses said that the security forces at the checkpoint on the bridge told their group to stop and started shooting in the air, but at the same time others opened fire at the group of people in front of them, who had crossed the bridge earlier. When they were finally able to get through, witnesses said, they picked up 17 bodies.[45]

Another witness, “Mazhar” (not his real name) from Tafas, described the same incident to Human Rights Watch saying that when his group that was heading to the funeral was about 200 meters from the checkpoint, security forces first shot in the air. Protesters stopped, and those who were driving got out of the cars to demonstrate that they presented no threat, but the security forces then immediately fired into the crowd. Mazhar said he personally witnessed the killing of five people, and saw dozens of wounded.[46]

Killings during the siege of Daraa and neighboring villages and April 29 protest

At around 4:30 a.m. on April 25, Syrian security forces launched a large-scale military operation in Daraa. Multiple witnesses who were in Daraa at the time described to Human Rights Watch how the security forces moved into the city using military vehicles, including numerous tanks and armored personnel carriers (APCs), under the cover of heavy gun fire that lasted unabated for about 16 hours. Security forces occupied all neighborhoods in Daraa, imposed checkpoints, and placed snipers on the roofs of buildings in many parts of the city. They imposed a siege on the city (see below) and prevented any movement of residents in the streets. Security forces opened fire on those who tried to defy the ban on movement and gatherings, or simply left their homes in an effort to get food or medication.

Activists who were documenting the events in Daraa told Human Rights Watch that the first nine days of the siege were the deadliest. They estimated that the security forces killed at least 200 people during this period and said they were able to verify the names of 115 of them. They said that due to the siege some of the bodies have not been identified while some families are still looking for their relatives whom they believe to have been shot and possibly killed during the first days of the siege.

On April 29, 2011, thousands of people from towns surrounding Daraa attempted to break the blockade on the city. Nine witnesses from the towns of Tafas, Tseel, and Sahem al-Golan who were part of this group told Human Rights Watch that the security forces killed at least 62 people and wounded scores of others when they opened fire at the approaching protesters. Human Rights Watch has the names of 44.

Witnesses said that the security forces stopped the protesters who were trying to approach Daraa at a checkpoint near the Western entrance of Daraa city. One of the witnesses from the town of Tseel who participated in the protest said:

We stopped there, waiting for more people to arrive. We held olive branches, and posters saying we want to bring food and water to Daraa. We had canisters with water and food parcels with us. Eventually thousands of people gathered on the road—the crowd stretched for some 6 km.

Then we started moving closer to the checkpoint. We shouted “peaceful, peaceful,” and in response they opened fire. Security forces were everywhere, in the fields nearby, on a water tank behind the checkpoint, on the roof of a nearby factory, and in the trees, and the fire came from all sides. People started running, falling, trying to carry the wounded away. Nine people from Tseel were wounded there and one of them died.[47]

Another participant, Mazhar, from Tafas, said:

There was no warning, no firing in the air. It was simply an ambush. There was gunfire from all sides, from automatic guns. Security forces were positioned in the fields along the road, and on the roofs of the buildings. They were deliberately targeting people. Most injuries were in the head and chest.

Two men from Tafas were killed there: 22-year-old Muhammad Aiman Baradan and 38-year-old Ziad Hreidin. Ziad stood next to me when a sniper bullet hit him in the head. He died on the spot. Altogether, 62 people were killed and more than a hundred wounded, I assisted with their transportation to Tafas hospital.[48]

Another witness, “Aiman” (not his real name), from Sahem al-Golan, said that he helped to carry away three of the bodies, including the body of a 17-year-old boy from his town, Hasan Kamal Hasan Taani, who was from Sahem al-Golan and died from a sniper bullet that hit him in the neck.[49]

Mazhar said that the protesters brought at least a hundred wounded people and bodies of the dead to Tafas hospital as it was the only hospital in the area that security forces had not occupied. He said he assisted with the transportation of the wounded and the collection of medical supplies for the hospital. Other witnesses confirmed that the protesters brought the wounded and killed to Tafas hospital where they compiled the names of 62 people killed that day.

Other incidents of killings in and around Daraa

In addition to killings at demonstrations, almost all of the people interviewed by Human Rights Watch were eyewitnesses to incidents in which security forces opened fire at people who took no part in the protests. The victims were bystanders who happened to be near the demonstrations, people who were trying to escape the violence, or, during the siege, those who dared to step outside of their houses.

For example, one of the witnesses, “Ali” (not his real name), described the killing of his neighbor, 23-year-old Rateb Abdul Salam al-Harri, in the Othman suburb of Daraa. Ali said that in the evening of April 22, Rateb was returning home on his motorcycle when a security patrol shouted at him to stop. Ali said:

Rateb stopped and started getting off his motorcycle. Mukhabarat, in camouflage uniforms, with green straps in their shoulders, were just two meters away from him—it was right in front of my house. They did not say anything. One of the agents just shot him in the head, right into his forehead, as he was getting off his bike. They shot him and simply walked away.

I ran out, barefoot, and together with my neighbor we brought the body to his uncle’s house so that one of the female members could notify his mother.[50]

Another witness, Mazhar, said that when security forces moved into his home town of Tafas in the morning of May 7 they mostly fired into the air to scare people and to force them inside. However, he also witnessed snipers deployed on a roof not far from his house open fire on a group of people who were trying to leave the market, killing one and injuring another four, including three young men and a woman. Later, as Mazhar and about a hundred other people tried to escape from the town through Yarmuk valley, security forces in military vehicles chased them and opened fire, killing two other men. [51]

Another witness said that on May 16, he was in the hospital with a sick relative when people brought in two men. One of them was dead, hit by a bullet in the chest. The other was wounded in the shoulder, and told the witness that security forces opened fire at them when they were trying to sneak out of town to get bread. The witness said that the doctors provided some basic first aid to the wounded man, and then relatives took him and the body of the other man away, fearing that the security forces would otherwise take them from the hospital.[52]

According to witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch, the victims of the violence included several soldiers of the Syrian army who were deployed to Daraa but refused to shoot at the protesters. Omar described to Human Rights Watch one such case that he witnessed:

Several days after Daraa came under siege, I was on Yarmuk street in the city. A group of people there were throwing stones at a sniper placed on one of the buildings. Security forces then sent an APC to stop them. The APC stopped near a local school, and six soldiers got out.

But instead of shooting at the people, they immediately dropped their weapons, raised their hands, and said they were with the people. Snipers opened fire, and hit four of the soldiers in the back, while the remaining two managed to run away with the people.

Heavy fire continued, but we were determined to rescue the bodies. We brought a long metal bar, made a hook on its end, and pulled the bodies away by the ankles. It turned out the soldiers were from the 15th airborne division. We buried them together with other martyrs.[53]

Another witness described the same incident to Human Rights Watch.[54]

Allegations of violence by protesters

Syrian authorities repeatedly claimed that the violence in Daraa was perpetrated by armed terrorist gangs, incited and sponsored from abroad.[55] In its reporting, Syria’s official news agency, SANA, has published the names of 105 members of Syria’s security forces (police, mukhabarat, and army) who died in Syria between April 9 and May 31.[56] According to SANA, they were killed by “armed gangs” or “terrorists.” Other than the cases mentioned below, Human Rights Watch has no information on the killing of security members.

On several occasions, starting end of March, after security forces first used lethal force against the demonstrators, Daraa residents indeed resorted to violence. For example, they set several buildings on fire, including the governor’s house and the political security building, burnt Bashar al-Asad’s photo monument, and tried to topple the statue of Hafiz al-Asad. They also set several vehicles belonging to the security forces on fire. Witnesses described some of these episodes to Human Rights Watch; they were also shown on amateur videos available online.

Several witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch also said that protestors had killed members of security forces. One witness said that on one occasion (he could not remember the date of the incident), after snipers on rooftops killed several protesters, people waited until the snipers ran out of ammunition, and then ran up to the roofs and threw several snipers off the buildings.[57]

Another witness said that on April 22, protesters in Nawa, a town west of Daraa, marched toward the political security office and demanded the release of two detainees who had been taken by security forces from the hospital. The witness, “Saleh” (not his real name), said that the protesters were waving olive branches, and a tribal leader pleaded with the political security to release the wounded men. Instead, 15 political security agents opened fire at the crowd, killing at least four people, and wounding another eight. Saleh said that the protesters, who were more than a thousand people, had seven birdshot guns among them, which they fired, but mostly they just kept retreating and coming back, hoping the security forces would run out of ammunition.

At some point, Saleh said, a soldier from a nearby army unit brought the protesters two Kalashnikovs and a box of ammunition. According to Saleh, the protesters repeatedly called on the security forces to surrender as they were clearly outnumbered by the protesters, and promised not to harm them. But the security forces continued to fire at the crowd. When the security forces ran out of ammunition, the protesters overtook the building and released the two detainees. Saleh said that inside the compound they saw seven members of the security who had apparently been shot and killed by the protesters during the confrontation. Saleh said that they captured another three security members, one of whom was wounded, while the remaining five escaped. Saleh said that the family members of the wounded ex-detainees wanted to kill the captive security forces, but the protesters instead beat them up and then brought them to the hospital where they released them.[58]

At the same time, all of the witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that the protests started peacefully, with demonstrators often carrying olive branches, unbuttoning their shirts to show that they had no weapons, and chanting “peaceful, peaceful” to indicate that they posed no threat to the security forces. Dozens of videos of Daraa protests provided to Human Rights Watch by witnesses as well as those posted online corroborate these accounts.

Witnesses, including some Jordanian nationals who came to Daraa for business and were in the city during the protests but took no part in the demonstrations, said that protesters only used violence against the security forces and destroyed government property in response to killings by the security forces or, as in the case described above, to secure the release of wounded demonstrators captured by the security forces and believed to be at risk of further harm.

Such incidents should be further investigated and the perpetrators of unlawful use of force brought to justice. However, these incidents by no means justify the massive and systematic use of lethal force against the demonstrators, which was clearly disproportionate to the threat presented by the overwhelmingly unarmed crowds.

The use of force by state security forces acting in a law-enforcement capacity is governed by international standards. Syria is a party to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and therefore must respect the rights to life and security, and to peaceful assembly.

The UN Code of Conduct for Law Enforcement Officials states that “law enforcement officials may use force only when strictly necessary and to the extent required for the performance of their duty.”[59]

The UN Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms provides that law enforcement officials “shall, as far as possible, apply non-violent means before resorting to the use of force” and may use force “only if other means remain ineffective.”[60] When the use of force is necessary, law enforcement officials must “exercise restraint in such use and act in proportion to the seriousness of the offense.”[61]

Article 10 of the Basic Principles requires that law enforcement officials “give clear warning of their intent to use firearms.”[62] Article 9 states that “intentional lethal use of firearms may only be made when strictly unavoidable in order to protect life.”[63]

The Basic Principles make clear that there can be no departure from these provisions on the basis of “exceptional circumstances such as internal political stability or any other public emergency,” i.e. that these are non-derogable standards.[64]

Denial of medical assistance

Syrian authorities routinely denied wounded protesters access to medical assistance. In at least two cases documented by Human Rights Watch (and reportedly in many others) this denial of medical assistance led to the death of those wounded.

Witnesses told Human Rights Watch that security forces prevented ambulances from reaching the wounded, and on several occasions opened fire as medical personnel were trying to reach the injured, in one case killing a doctor and a nurse, an episode the authorities later blamed on “armed gangs.”[65] Security forces took control of most of the Daraa hospitals and detained the wounded who were brought in. As a result, most of those wounded avoided the hospitals and were treated in makeshift clinics like the one set up inside al-Omari mosque or in private houses with no access to proper medical care. According to witnesses, after security forces stormed al-Omari mosque on March 24 (see above), they destroyed or confiscated all medical equipment that had been brought into the mosque to assist the wounded.

Many witnesses told Human Rights Watch that during the protests, security forces prevented people from rescuing the wounded. For example, one witness, Saleh, said that when security forces shot at protesters near the political security headquarters during the April 8 protest three of those hit died on the spot, but a fourth was still alive. Saleh said:

I saw a man who tried to pull the wounded guy away, but security forces continued to shoot. They were clearly targeting them—they again shot the wounded guy, this time in the head, and hit the rescuer as well—I don’t know whether he survived. Another man tried to take a dead body away on the motorcycle, but as he tried to approach, he got shot in the shoulder, then again in the leg, and when he fell off and other people made a move toward him, a sniper hit him in the head, and I believe he died.[66]

Another witness, Ahmed, said that during the April 8 protest the security forces also did not allow the ambulances to approach the road to pick up the wounded, and kept shooting when other protesters tried to carry the wounded away.[67]

Ahmed told Human Rights Watch:

I went to al-Omari mosque at around 2:30 p.m. and saw the bodies of 20 dead protesters and dozens of wounded who were brought there. People were lying on the floor, all over the place, and there were a couple of doctors and nurses and also local women struggling to help the injured. But they could not do much. They only had the basic supplies brought from the local pharmacies. The hospitals were blocked by the security forces and it was impossible to bring the necessary equipment or supplies into the mosque. Several people with serious injuries were dying and there was nothing we could do to help them.[68]

One of the witnesses, “Mazen” (not his real name), told Human Rights Watch that during the attack on protesters on April 29 (see above), which resulted in at least 62 deaths and hundreds of injuries, no ambulances were available to transport the wounded. He said:

We struggled to take the wounded away on motorcycles and trucks. At the Tafas hospital, which was the only hospital not occupied by the security forces, medical personnel quickly ran out of supplies. They had almost nothing to perform surgeries and there was almost nowhere to get the supplies from. The hospital provided first assistance and then we quickly sent people to private homes as we were expecting the security forces to come and arrest them any moment.[69]

Security forces also arrested medical personnel and ambulance drivers and confiscated the ambulances to prevent the drivers from assisting the wounded. One of the witnesses, “Khaled” (not his real name), said that two of his cousins, both ambulance drivers, were prevented from rescuing the wounded and had their ambulances confiscated. Khaled said that the security forces stopped one of them at a checkpoint about a week after the siege began. They confiscated the ambulance and warned the driver not to go back to work.

Khaled said that the second cousin, who is 57 years old, was arrested and held for four days at the political security department in Daraa. Security forces then released the man but confiscated his ambulance. Khaled also said that the security forces released the man at around 8 p.m., during the curfew, and to avoid being shot he crawled on his knees, with his hands up in the air, through six checkpoints in order to get home.[70]

Several witnesses from different parts of Daraa also told Human Rights Watch that after the security forces imposed a siege on Daraa and neighboring towns they burnt or destroyed many of the pharmacies and did not allow the delivery of medical supplies into the town (see below).

In at least two cases documented by Human Rights Watch, denial of medical assistance or obstacles to obtaining medical care resulted in the deaths of wounded protesters.

One of the witnesses, Saleh, said that during the April 29 attack described above, security forces wounded a young man from Tseel, 18-year-old Ahed Khalil Al-Qarfan. Saleh, who was among those who tried to rescue the man, said that Ahed was hit in both legs, and they first took him to Tafas hospital. But the hospital was running out of supplies and could not provide proper care. Saleh said:

We then decided to take him in a car to a hospital in Qunaitra. There were four checkpoints on the way, and at each checkpoint mukhabarat stopped us, checked the entire car, and all of the passengers, including the wounded, turning and undressing him although it was clear he was bleeding and in a lot of pain.

We begged them to let us through. Ahed’s father was crying, saying, “It’s my son, he is hurt,” but they pushed us aside, asking for weapons and telling us not to interfere with the search. They said, ‘You pigs, you animals, you don’t deserve to live.’

At the fourth checkpoint, Ahed died from massive blood loss. A nurse who was in the car with us said he was dead, but his father insisted that we take him to the hospital. In Qunaitra, they confirmed that he was already dead.[71]

Another witness, Omar, said that his neighbor, 22-year-old Ahmad Omar Zreqat, was wounded on April 25 when the large-scale military operation started in Daraa. According to Omar, a bullet went through Ahmad’s shoulder and into his liver. The hospital was under the control of the security forces so his parents did not take Ahmad there, fearing he would be arrested. As the city was under siege, no doctor or nurse could come to the house, and the parents only provided basic first aid which was insufficient given the seriousness of the injury. Omar said that on May 4, 2011 Ahmad died and his parents buried him in the yard of their house.[72]

Denial of medical aid is a form of inhuman treatment and may be a violation of the right to life guaranteed by international law, as it creates a life-threatening situation for seriously injured persons. The UN Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms also stipulate that “whenever the lawful use of force and firearms is unavoidable, law enforcement officials shall… ensure that assistance and medical aid are rendered to any injured or affected persons at the earliest possible moment.”[73]

Arbitrary arrests, “disappearances,” and torture

Throughout the country, Syrian authorities also launched a massive campaign of arrests, subjecting thousands of people to arbitrary detention and brutal torture. As in the rest of Syria, in Daraa the arrests started in late March to early April. But the campaign intensified dramatically after the imposition of the siege.

Witnesses from Daraa city and neighboring towns described to Human Rights Watch large-scale sweep operations conducted by the security forces, targeted arrests of activists and their family members, as well as arrests at checkpoints and by patrols in the streets. The exact numbers are impossible to verify but information collected by Human Rights Watch suggests that the security forces detained hundreds of people each day. Some of them were released several days or weeks later, while others have not reappeared, and in most cases the families have no information on their fate or whereabouts.

Many of the detainees were children. One of the witnesses told Human Rights Watch that out of about 370 people he shared a cell with, more than 70 were children.[74] Another witness mentioned the arrest of two of his nephews, ages 14 and 15.[75]

Large-scale sweep operations

The majority of the arrests, if not all, seemed entirely arbitrary with no formal charges ever brought against the detainees. Local activists told Human Rights Watch that those detained in Daraa were initially held in several ad hoc detention facilities, including a stadium, a football field, a customs department building, two local schools, and several big yards in private houses occupied by the security forces. This information was corroborated by released detainees interviewed by Human Rights Watch. The detainees were then brought to the military intelligence department, the political security department, or other facilities in Daraa and many were then sent to various detention facilities in Damascus.

Four witnesses from Tafas, a town 11 kilometers north of Daraa, said that at around 8:30 a.m. on May 7, 2011, security forces moved into the town with tanks and APCs, and launched large-scale sweep operations over a period of several days, breaking into houses and arresting people. Witnesses estimated that up to a thousand people were detained in the course of the operation, about 600 of whom were released within a week, while new arrests continued. The security forces targeted activists and their family members, medical personnel, and religious leaders, but also arrested a number of individuals who never took part in the protests.

Six witnesses described a sweep operation in the Othman neighborhood of Daraa on May 1, 2011. According to witnesses, during the operation groups of between 15 and 20 security forces entered the houses, breaking the doors if the residents failed to open quickly enough, and smashed everything inside, allegedly looking for weapons, mobile phones, as well as for those who took part in the demonstrations. All of the witnesses said that security forces took away mobile phones, money, and other valuable items from their homes.

Released detainees told Human Rights Watch that security forces arrested over a hundred people from Othman that day. Two of the witnesses, arrested that day and later released, provided detailed accounts of their ordeal to Human Rights Watch.

One of the witnesses, “Ali” (not his real name), said that early in the morning on May 1, a group of about 15 of security forces members broke into his house. He said:

They went inside, shot at the ceiling, and started turning everything upside down. They broke furniture and framed Koran verses on the walls, and took my watch, mobile, and money. They started beating me, and two of my small children got so scared that they peed on themselves. At the same time, they were breaking into other houses on the street. They blindfolded and handcuffed me and put me into a bus, beating me all the way. I could feel that there were many more detainees there.[76]

Ali said that he was then brought to a fenced football field in Daraa and when he managed to move his blindfold away from his eyes, he could see about 2,000 other detainees there. He said that the field was a temporary base for high-level security officials Hisham Bakhtiyar and Rustum Ghazali, who he believed were in charge of the operation in Daraa. He said he knew about it because when the violence began tribal leaders used to go there to meet with Bakhtiyar and Ghazali, and then told people about their meetings.

The second witness, “Hussein” (not his real) name, corroborated this account. Both witnesses described to Human Rights Watch an execution of detainees that took place shortly after they were brought to the football field (see below).

Both witnesses said that the security forces brought them, along with several hundred others, from the football field to the military intelligence department in Daraa (both could see the place and recognized it), and later to Damascus where they spent about two weeks in detention.

Another witness, “Mustafa” (not his real name), a Jordanian national, who came to Daraa for business and could not leave the city after the siege began, was arrested during a sweep operation on May 2. He said he was staying in the house of his business partner in Daraa al-Balad, near al-Omari mosque, when security forces started breaking into the houses. He said the security forces detained about 150 people from the neighborhood and took them all to a fenced yard of a private house occupied by the security forces and turned into an ad-hoc detention facility. When the guards realized he was a foreigner, they immediately transferred him to a different detention facility in Daraa and then sent him to Damascus where he spent three weeks in detention in different facilities.[77]

Torture and ill-treatment in detention

Ali, Hussein, and Mustafa, as well as the relatives of other released detainees interviewed by Human Rights Watch, said that all detainees, without exception, were subjected to various forms of torture and degrading treatment. The methods of torture included prolonged beatings with sticks, twisted wires, and other devices; electric shocks administered with tasers; use of improvised metal and wooden “racks,” and, in at least one case documented by Human Rights Watch, the rape of a male detainee with a baton. The interrogators and guards also subjected the detainees to various forms of humiliating treatment, such as urinating on the detainees, stepping on their faces, and making them kiss their shoes. Several detainees said they were repeatedly threatened with imminent execution.

All of the former detainees described appalling detention conditions, with grossly overcrowded cells where at times detainees could only sleep in turns, and lack of food.

Hussein described the ordeal he and other detainees went through, first in Daraa and then in Damascus:

At the military intelligence department, they took us down into the basement. I could hear the sounds of beatings and screams. Then they took me into an interrogation room. They started beating me, saying, “You want freedom? Here is your freedom.” At some point, my blindfold slipped off and I saw another detainee. He was hung by the hands, with his feet about 15 cm above the floor, and the guards were whipping him all over.

Then the interrogator said, “Put him on the flying carpet!” The guard stretched me face down on a wooden plate and started lifting the front part backwards so that my back started cracking. I screamed and said I would admit to anything they want. They lowered the rack, and started whipping me on my legs and buttocks with a twisted rubber whip. It lasted for some 30 minutes, until I fainted. They splashed water on my face, and brought me back to the cell.

They kept bringing more people in, including my cousins and neighbors. At some point, they brought in an old man, maybe 75 or 80 years old, with his two sons. One of the guards told him they wouldn’t beat him because of his age but told him to kiss his shoe. The old man bowed and kissed his shoe. And then this guard told another one, “Now, go wash my shoe because this dirty man kissed it.”