Summary

"Why Jordan?" The question puzzled Abu Hamza al-Tabuki, a Saudi citizen who claims that US agents arrested him in Afghanistan in December 2001, interrogated him in Pakistan, and then flew him in a private jet to Jordan. Because he was not Jordanian and had no past connection to Jordan, he did not understand why he was sent there. "Why wasn't I sent to America since I was arrested by Americans?" al-Tabuki asked, in a narrative he sent to contacts in Jordan after he was released.

What al-Tabuki learned was that Jordan offered greater possibilities for abusive interrogations: it was a place for him to be questioned "more freely," as one US official put it.

According to al-Tabuki, the Jordanians' methods included "terror and fear, torture and beatings, insults and verbal abuse, and threats to expose my private parts and rape me." Nor was al-Tabuki alone in facing this abuse. Based on our investigations in Jordan and elsewhere, including interviews with several former detainees, Human Rights Watch has concluded that al-Tabuki was one of at least 14 prisoners that the United States sent to Jordan for interrogation and likely torture.

From 2001 until at least 2004, Jordan's General Intelligence Department (GID) served as a proxy jailer for the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), holding prisoners that the CIA apparently wanted kept out of circulation, and later handing some of them back to the CIA. More than just warehousing these men, the GID interrogated them using methods that were even more brutal than those in which the CIA has been implicated to date. The prisoners were typically held for several months in GID custody-and in at least one case, for nearly two years.

While the exact number of transfers cannot be ascertained, Human Rights Watch has found that at least 14 non-Jordanian prisoners were sent from United States to Jordanian custody during this three-year period, and the actual figure may be much higher. While a few other countries have received individuals rendered by the United States in recent years (that is, transferred without formal legal process), no country is known to have detained as many as Jordan.

Human Rights Watch has credible information indicating that the prisoners included at least five Yemenis, three Algerians,two Saudis, a Mauritanian, a Syrian, a Tunisian, and one or more Chechens. They may also have included a Libyan, an Iraqi Kurd, a Kuwaiti, one or more Egyptians, and a national of the United Arab Emirates.

The majority of the men whom the US brought to Jordan were initially arrested in either of two places: in Pakistan, particularly the city of Karachi, and in Georgia, from the Pankisi Gorge. One reportedly said that he was held for three months at a US prison in Iraq before being moved to Jordan, while many others were later held in secret CIA detention in Kabul or at the US military base at Bagram, in Afghanistan.

These prisoners include five men currently held at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba-Ramzi bin al-Shibh, Hassan bin Attash, Ali al-Hajj al-Sharqawi, Jamal Mar'i, and Mohamedou Ould Slahi-as well as one man believed to be in custody in Saudi Arabia. Ibn al-Sheikh al-Libi, currently in custody in Libya, was probably also held in Jordan for a time. The current whereabouts of a number of other former prisoners are unknown or unconfirmed, though some of them may have been returned to their countries of origin.

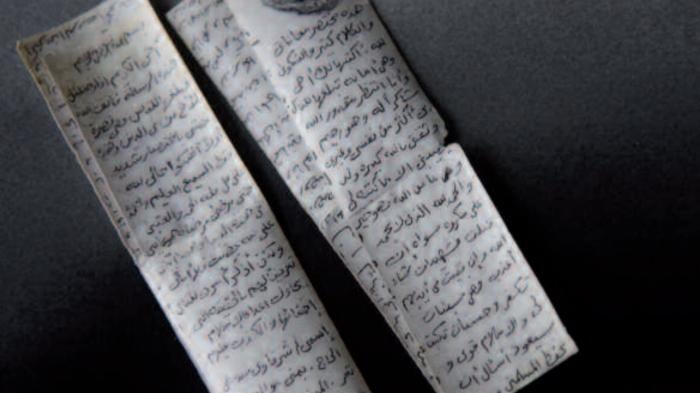

While in GID detention in late 2002, one of these prisoners, Ali al-Hajj al-Sharqawi, wrote a long note describing his ordeal. The note, which al-Sharqawi marked with his thumb print, was smuggled out of the facility in 2003. In it, al-Sharqawi describes being held as a secret prisoner and hidden in secret cells. Consistent with what al-Sharqawi told two fellow prisoners at GID at the time, the note states that the GID interrogators "beat me in a way that does not know any limits."

"They threatened me with electricity," the note continues, "with snakes and dogs .... [They said] we'll make you see death .... They threatened to rape me."

Al-Sharqawi later told his lawyers at Guantanamo that GID interrogators had subjected him to a torture method known as falaqa, by which prisoners are given extended beatings on the bottoms of their feet. He said that after the interrogators beat him, they would resume interrogating him, and would threaten to electrocute him if he did not provide information. He also told his lawyers that when representatives of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) visited the GID facility, he was hidden from them.

The same two prisoners who communicated with al-Sharqawi while he was held at GID also communicated with Hassan bin Attash. They said that bin Attash arrived at the GID facility several months after al-Sharqawi, and suffered similarly abusive treatment.

"Just about everyone at GID was beaten with sticks," one former GID prisoner told Human Rights Watch. "People were beaten on their feet. They did it in the basement. I was beaten twice, but al-Sharqawi, ba Attash and al-Jeddawi [a Saudi prisoner who was rendered to Jordan] were beaten much more than me."

According to another former detainee who claims that he was held in a neighboring cell, terrorist suspect Ramzi bin al-Shibh was among the prisoners that US agents transferred to GID custody. The former detainee told Human Rights Watch that al-Shibh (who was arrested in Pakistan in September 2002) was held in GID custody in late 2002. Al-Shibh reportedly said that he had been flown to Jordan via Qatar, and that he had been badly tortured in Jordanian custody.

Flight records that Human Rights Watch has obtained support these claims. Civilian aircraft linked to the CIA, including Gulfstream jets and Boeing 737s that are known to have been used for prisoner transport, made dozens of trips to Jordan during the period of 2001 to 2004. Some of these flights coincide exactly with the dates that detainees said they were transferred.

In a meeting with Human Rights Watch in Amman in late August 2007, senior GID officials categorically denied that the GID had held prisoners rendered by the United States. They also denied that torture was practiced in GID detention. Given the weight of credible evidence showing the opposite, their denials are unconvincing.

Human Rights Watch conducted research for this report from August 2007 to February 2008 in Jordan. We held in depth interviews with six Jordanian nationals who said that while they were detained at the GID detention facility in Amman, they communicated with prisoners who had been delivered to the GID from US custody.[1] All of our informants were detained by the GID for varying periods of time between mid-2002 and 2005. Human Rights Watch also spoke to a former Guantanamo detainee who said that while at Guantanamo he spoke to prisoners who had been rendered by the CIA to Jordan. In addition, we received extremely useful information from lawyers representing detainees at Guantanamo, including detainees who were previously held for a time in Jordan. Finally, Human Rights Watch interviewed more than a dozen Jordanians who claim that they were brutally tortured in GID custody during this same period, and who described the torture techniques that the GID employed. We have sought, wherever possible, to corroborate information from interviews with prisoners' written accounts, flight logs, and other secondary materials.

Recommendations

The US government should:

·Repudiate the use of rendition to torture as a counterterrorism tactic and permanently discontinue the CIA's rendition program;

·Disclose the identities, fate, and current whereabouts of all persons detained by the CIA or rendered to foreign custody by the CIA since 2001, including detainees who were rendered to Jordan;

·Repudiate the use of "diplomatic assurances" against torture and ill-treatment as a justification for the transfer of a suspect to a place where he or she is at risk of such abuse;

·Make public any audio recordings or videotapes that the CIA possesses of interrogations of detainees rendered by the CIA to foreign custody;

·Provide appropriate compensation to all persons arbitrarily detained by the CIA or rendered to foreign custody.

The Jordanian government should:

·Repudiate its role as a proxy jailer in the CIA's rendition program;

·Disclose the identities, fate, and current whereabouts of all persons rendered to Jordan by the CIA since 2001;

·Make public any audio recordings or videotapes made of interrogations of detainees rendered by the CIA to Jordan;

·Open an immediate independent judicial inquiry into the GID's use of torture, ill-treatment, and arbitrary detention.

Other governments should:

·Refuse to cooperate in secret detention and rendition efforts, and disclose all information about past cooperation in such efforts.

Background

The US Practice of Rendition

The US practice of rendering terrorist suspects abroad-in other words, of transferring prisoners to foreign custody outside of normal legal proceedings-predates the September 11, 2001 attacks on the United States. During the administration of President Bill Clinton, the CIA rendered a number of Egyptian terrorist suspects from countries such as Albania and Croatia to Egypt, where some of them had previously been sentenced to death in absentia.[2] After September 2001, however, the CIA's rendition practices changed. Rather than returning people to their home countries to face "justice" (albeit justice that included torture and grossly unfair trials), the CIA began handing people over to third countries apparently to facilitate abusive interrogations.

The US may have had several reasons for transferring suspects to Jordan for detention and interrogation. The CIA already had a history of close relations with the Jordanian intelligence agency; there was apparently a shortage of Arabic speakers on CIA staff, and CIA officials may have believed that Jordanian officials were particularly well versed in counterterrorism or perhaps would be particularly good at keeping the fact of the detentions secret. Yet Jordan was already notorious for torturing security detainees, and this would have been well known to US officials at the time of the transfers. As detailed in this report, many of the detainees were returned to CIA custody immediately after intensive periods of abusive interrogation in Jordan, and certain US officials, including former CIA officer Michael Scheuer, have made statements suggesting that detainees were knowingly sent to a place where they would be abused. The evidence indicates that torture in such cases was not a regrettable consequence of rendition; it may have been the purpose.

In a classified briefing for US senators not long after the September 11 attacks, then-CIA Director George Tenet reportedly alluded to the thinking behind these new renditions. Asked whether the US government was planning to seek the transfer of Al Qaeda suspects from abusive governments, Tenet suggested that it might be preferable for some suspects to remain in the hands of foreign authorities able to use more aggressive interrogation methods on them.[3] Cofer Black, who served as the Director of the CIA's CounterterroristCenter from 1999 until May 2002, put the matter more bluntly. In discussing the detention of "nearly three thousand al-Qa'ida terrorists and their supporters," he said that "there was a before 9/11 and there was an after 9/11. After 9/11 the gloves come off."[4]

Just after the September 11 attacks, US President George W. Bush signed a classified presidential directive giving the CIA expanded authority to arrest, interrogate, detain, and render terrorist suspects arrested abroad.[5] Since that time, the US is believed to have rendered terrorism suspects to the custody of Egypt, Morocco, Libya, and Syria, in addition to Jordan. But the available evidence suggests that Jordan was the first country to receive rendered detainees after September 11, and that Jordan accepted the largest number of detainees.[6]

Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, under pressure from European allies because of press revelations about CIA activities in Europe, offered a vigorous defense of US rendition practices in December 2005. Asserting that the practice of rendition was a "vital tool in combating transnational terrorism," Rice claimed that the United States and other countries have long relied on renditions to transport terrorist suspects from the country where they were arrested to their home country or to other countries where they can be held and questioned. She insisted, moreover, that the United States "does not transport, and has not transported, detainees from one country to another for the purpose of interrogation using torture." Instead, she explained that, where necessary, "the United States seeks assurances that transferred persons will not be tortured."[7]

The systematic nature of the abuses suffered by prisoners rendered to Jordan contradicts Rice's bland reassurances. If the Jordanians did indeed promise the US authorities that prisoners rendered there would not be tortured, it was a promise that neither the US nor Jordan believed.

A description of the rendition process provided by then-Attorney General Alberto Gonzales in August 2006 was somewhat more revealing. Testifying before the Senate Armed Services Committee, Gonzales explained that "we seek assurances, whenever we transfer someone, that in fact that they will not be tortured." He admitted, however, that: "you know, we are not there-(chuckles)-in the jail cell in foreign countries where we render someone."[8]

Michael Scheuer, a former CIA officer who claims to have initiated the terrorist rendition program during the Clinton administration, rightly dismisses these assurances as "legal niceties"-pledges meant to look good on paper, which provide no real protection. He has said that both CIA agents and their superiors were aware that abuses were likely.

As Scheuer has explained:

[T]he non-C.I.A. staff members . . . knew that taking detainees to Egypt or elsewhere might yield treatment not consonant with United States legal practice. How did they know?

Well, several senior C.I.A. officers, myself included, were confident that common sense would elude that bunch, and so we told them-again and again and again. Each time a decision to do a rendition was made, we reminded the lawyers and policy makers that Egypt was Egypt, and that Jimmy Stewart never starred in a movie called "Mr. Smith Goes to Cairo."

They usually listened, nodded, and then inserted a legal nicety by insisting that each country to which the agency delivered a detainee would have to pledge it would treat him according to the rules of its own legal system.[9]

The growing weight of evidence and international expert opinion indicates that diplomatic assurances cannot protect people at risk of torture on return.[10] Part of what makes such promises ineffective is the nature of torture, which is practiced in secret, using techniques that may not leave marks and may defy detection (for example, mock drowning, sexual assault, and threats of violence). And detainees subjected to torture are often afraid to complain to anyone about the abuse for fear of reprisals against them or their family members.

It is unknown precisely how many people have been rendered to foreign custody since 2001. Representative Ed Markey, a member of the Select Committee on Homeland Security, told the New Yorker in 2005 that he had been unable to obtain a count. "I've asked people at the CIA for numbers," he said. "They refuse to answer. All they will say is that they're in compliance with the law."[11] CIA Director Michael Hayden claimed in a September 7, 2007, speech before the Council on Foreign Relations that fewer than 100 people had been rendered abroad since the September 11 attacks: "mid-range two figures," in his words.[12]

Jordan's General Intelligence Department

Jordan's General Intelligence Department (GID) (Da'irat al-Mukhabarat al-'Amma) is the country's main intelligence agency, charged with investigating threats to national security.[13] TTThe GID has long had a close and cooperative working relationship with the CIA.[14] That relationship deepened further still in the wake of the September 11 attacks.[15] Given the intimate nature of GID/CIA links, it is hardly surprising that the CIA turned to the GID when President Bush gave the agency expanded authority to detain and question people suspected of links to terrorism.

The GID's abusive interrogation practices are well known. Numerous former GID prisoners have reported that while in GID custody they were subjected to torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment. In particular, many have claimed that guards brought them to the basement of the GID detention building in Wadi Sir and administered the falaqa: beating them on the soles of their feet.[16] Others have said that they were hit, deprived of sleep, or given pills and injections that induced feelings of extreme anxiety.

These men's claims are supported by the findings of UN envoys and international organizations. In 2006, after carrying out a visit to Jordan, the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture issued a report concluding that: "The practice of torture is widespread in Jordan, and in some places routine, [including] the General Intelligence Directorate (GID)." Although the Special Rapporteur was denied access to interview prisoners held in GID detention in Amman, he cited credible and consistent allegations that torture was used at GID headquarters "to extract confessions and obtain intelligence in pursuit of counter-terrorism and national security objectives."[17] Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch have reported similar findings.[18]

US officials were well aware of these abuses, including during 2001 to 2004. The Jordan chapter of the US State Department's 2001 human rights report states that prisoners in the custody of Jordanian police and security forces have alleged that "methods of torture include sleep deprivation, beatings on the soles of the feet, prolonged suspension with ropes in contorted positions, and extended solitary confinement."[19]

The GID Detention Facility at Wadi Sir

Prisoners transferred from US to Jordanian custody from 2001 to 2004 were held at the GID's main headquarters in Amman, located in the Jandawil district in Wadi Sir. The headquarters, which appear to cover nearly an acre of land, contain a large four-story detention facility that Human Rights Watch visited in August 2007.[20]

The building that holds the detention facility is in the shape of two triangles that together form a square; the facility itself takes up approximately half of the building, i.e., one of the triangles. Each floor of the detention facility, except the top floor, consists of three main corridors (the sides of the triangle) running around a central courtyard. The administrative offices and interrogation rooms are on the second floor of the building, while visiting rooms are on the ground floor. During the period that Human Rights Watch inspected the facility, all of the detainees in custody were held on the second floor.[21] There are also many cells on the ground floor and third floor, however, as well as a small number of cells on the fourth floor, which includes a few collective cells and what the director called the "women's section" of the facility.[22] In addition, the facility has a basement where many prisoners have claimed that they were brought for the most violent treatment.

Prisoners in GID detention at Wadi Sir are kept in single-person cells and are prohibited from speaking with one another, but some have managed to communicate via the back window of their cells. (Each cell faces onto the central courtyard, and has a window looking out on the yard.)

Rendition to Jordan

After September 11, 2001, the CIA quickly began rendering suspected terrorists to Jordan for interrogation.[23] The first case may have been that of Jamal Mar'i, a Yemeni living in Karachi, who was picked up by a joint team of CIA and Pakistani intelligence operatives at his home on September 23. Within a few weeks of his arrest, he was delivered to GID custody in Jordan, where he was held for several months. Mar'i, who is now in detention at Guantanamo, has not complained of being tortured in Jordan; in this respect his case is unusual.

What is typical about Mar'i's case-and what distinguishes it from pre-September 2001 renditions-is that Mar'i was not Jordanian, and had no particular connection to Jordan.[24] The GID had no obvious reason to be concerned about Mar'i, beyond an interest in helping the CIA. It appears, in short, that the GID acted as a true proxy jailer for the CIA: primarily serving the CIA's interests, rather than collaborating with the agency for its own security reasons.

The fact that several detainees were later returned to CIA custody after spending time in Jordan further suggests that the GID's goal in the rendition program was assisting the CIA rather than directly furthering Jordanian security objectives. Such people were not actually handed over; rather they were effectively lent to Jordan for interrogation purposes. At least five men who are currently detained at Guantanamo were previously rendered to Jordan for some amount of time during the period of 2001 to 2004. In addition, at least two Yemeni prisoners who were later held in secret CIA prisons (without being sent to Guantanamo) were arrested in Jordan and held in GID custody for a few days or weeks prior to their transfer into US custody.[25]

Al-Sharqawi, one of the detainees whom the CIA delivered to Jordan in 2002, noticed that GID interrogators were extremely eager to provide information to the CIA. In the note that al-Sharqawi wrote while in GID detention in 2002, he said:

Every time that the interrogator asks me about a certain piece of information, and I talk, he asks me if I told this to the Americans. And if I say no he jumps for joy, and he leaves me and goes to report it to his superiors, and they rejoice.[26]

He later told his lawyers that one of his Jordanian interrogators acknowledged that he was asking questions that the Americans had provided.[27]

Not long after Ma'ri was transferred to Jordan, another Yemeni living in Pakistan was apparently sent there as well. Jamil Qasim Saeed Mohammed was a student; he was studying microbiology at KarachiUniversity. After being arrested by the Pakistani security forces and handed over to US authorities, he was reportedly flown to Jordan in the early morning hours of October 24, 2001. Very little is known about his case, since he has not been seen since that time, but journalists reported that he was an Al Qaeda operative.[28]

A third person rendered to Jordan in 2001 was Mohamedou Ould Slahi. Slahi, a Mauritanian citizen, was arrested in Mauritania in November 2001, brought to Jordan soon after, and held there until July 2002. Like Mar'i and others, he is currently incarcerated at Guantanamo.

Several prisoners were believed to have been rendered by the US to Jordan in 2002, including Ali al-Hajj al-Sharqawi, Hassan bin Attash, Ramzi bin al-Shibh, Ibrahim Abu Mu'ath al-Jeddawi, Abu Hamza al-Tabuki, Khayr al-Din al-Jaza'eri, Abu Yousef al-Jaza'eri, Abu Hassan al-Suri, and Abu Bakr Saddiqi, as well as a number of people whose names are unknown.[29] Although it is difficult to know with certainty-and additional prisoners reportedly arrived in 2003-it appears that 2002 was the year in which the CIA delivered the largest number of people to Jordan. (This may be because as time went on the CIA developed its own detention capacity, opening secret facilities in Thailand, Afghanistan, Poland, and Romania, and had less need to rely on Jordan.[30]) Some of the detainees who arrived in Jordan in 2002 were held for more than a year, leaving GID custody in 2004. While it is impossible to estimate the total number of people who were rendered to Jordan, some former prisoners told Human Rights Watch that for a while in 2002 and 2003 the third floor of the GID detention facility was "full" of non-Jordanian prisoners who had been delivered by the CIA.

Pakistan, and in particular the city of Karachi, was the source of at least six detainees believed to have been rendered to Jordan from US custody. The Pakistani authorities have made no secret of the fact that since September 2001 they have handed over several hundred terrorism suspects to the United States, boasting of the transfers as proof of Pakistan's cooperation in US counterterrorism efforts.[31] A large number of these men ended up at Guantanamo; some ended up in secret CIA prisons, and others were rendered to Jordan and other countries.[32]

Another source of prisoners was the Pankisi Gorge, in Georgia. Home to thousands of Chechen refugees, the Pankisi Gorge borders on Russia's Chechnya region and has long served as an entry point for Arab mujahideen seeking to fight in Chechnya. In early 2002, under US pressure, the Georgian government began arresting Arabs found there, including a number of Algerians.[33] Some of these men were transferred to proxy CIA prisons in Afghanistan, and then sent to Guantanamo, but others were brought by the CIA elsewhere. At least four of the men who were reportedly rendered to Jordan in 2002-Khayr al-Din al-Jaza'eri, Abu Yousef al-Jaza'eri, Abu Hassan al-Suri and Abu Bakr Saddiqi-were reportedly picked up in Georgia. (Khayr al-Din al-Jaza'eri, an Algerian, is also described in the court opinion of a high-profile French terrorism prosecution as a militant who operated in the Pankisi Gorge.[34]) The current whereabouts of all four men are unknown, although it is likely that they were at some point transferred to their home countries for continued detention.

Torture and cruel or inhuman treatment seems to have been systematically used against the detainees rendered by the CIA to Jordan, with the exception of al-Mar'i. As described in detail below, detainees claim that they were threatened, beaten, insulted, deprived of sleep, and subjected to falaqa. In addition, they appear to have been systematically hidden from the ICRC representatives who visited the GID detention facility. Human Rights Watch interviewed several former GID detainees who said that they were hidden whenever the ICRC visited, and that prisoners rendered to Jordan by the United States were hidden as well.

Al-Tabuki, the Saudi who was in GID custody in 2002, described how he was hidden during the ICRC's visits:

Early in the morning, the guards would come, telling us to pack all of our clothes and belongings, and they would take us while we were blindfolded to cells and areas that the Red Cross does not know exist. We would remain there the entire day until their visit ended, and then would be returned back to our cells. They [the ICRC] would either be given the impression that the floor was empty, or it would be filled with prisoners who had legal status. And sometimes we had with us Jordanian prisoners who the Red Cross would learn about only through their families, rather than the legal system. They would move us with those prisoners to the guards' quarters, where we would remain the whole day, sitting down blindfolded, and with our hands manacled behind our backs, until the Red Cross's visit was over. And if the Red Cross did not complete its visit and would return the next day, this same scenario would be repeated.[35]

Similarly, Sharqawi told his lawyers that whenever ICRC representatives visited the GID facility, he would be moved to the soldiers' lecture room at and kept there until the representatives left.

The secrecy surrounding the detention of these men continues. While five people who were previously rendered to Jordan are now at Guantanamo, and two are believed to have been released, the current whereabouts of most of the prisoners whom the US rendered to Jordan is not known. It is quite possible that many or all of the remaining detainees underwent a second rendition, being transferred from Jordan back to their home countries without any legal proceedings or any opportunity to challenge the transfer.

Cases

Ibrahim "Abu Mu'ath" al-Jeddawi (Ahmad Ibrahim Abu al-Hasana)

Ibrahim "Abu Mu'ath" al-Jeddawi is a Saudi who reportedly lived in Yemen. Human Rights Watch spoke to two former detainees held by the GID who said that they communicated with him while he was detained at the GID detention facility in late 2002; al-Tabuki wrote that he saw al-Jeddawi there, too. He was said to be approximately 32-38 years old.

In early 2002, the US Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) placed Abu Mu'az al-Jeddawi (almost certainly the same person) on its "Seeking Information – War on Terrorism" list, calling him a known associate of a Yemeni al Qaeda cell leader.[36] A little more than a month later, however, al-Jeddawi was removed from the list, probably because the FBI learned that he was in CIA or Jordanian custody. Human Rights Watch has confirmed that he was transferred to GID custody sometime in the first half of 2002.[37]

Human Rights Watch's sources differ regarding where al-Jeddawi was arrested. Both al-Tabuki and another person claim that al-Jeddawi was arrested in Yemen. Al-Tabuki said that he was arrested less than a month after his wedding. A third source, however, who was also held in GID custody with al-Jeddawi, believes that al-Jeddawi was arrested in Kuwait, although he was not certain about this point. All of them agree, at any rate, that al-Jeddawi was in US custody prior to being handed over to Jordan. And according to one source, a US agent "hit him in the head."

A summary of evidence memo used in annual status review proceedings for Abdul Rahman Mohammed Khowlan, a Saudi citizen who was held at Guantanamo from 2002 to 2006, mentions Khowlan's association with someone named "Abu Mu'ath."[38] This may very well be the same person, and suggests that the US military may have relied on information obtained from al-Jeddawi while al-Jeddawi was in US or Jordanian custody.

One person, who told Human Rights Watch that al-Jeddawi was "famous in Afghanistan," said:

He was a really rich guy, and he lived in Yemen; he was married to a Yemeni woman. The Yemenis arrested him and handed him over to the US. I actually saw him in GID: we met in the bathroom thanks to the help of a nice soldier.

This same informant not only saw al-Jeddawi in custody in late 2002 but also communicated with al-Jeddawi's family later. He said that the family told him that al-Jeddawi was held at the GID facility for more than a year, during which time he was kept hidden from the ICRC. Al-Jeddawi is believed to be currently incarcerated in Saudi Arabia.

Khayr al-Din al-Jaza'eri, Abu Yousef al-Jaza'eri, Abu Hassan al-Suri, Abu Bakr Saddiqi, and possible unnamed Chechen

Khayr al-Din al-Jaza'eri, Abu Yousef al-Jaza'eri, and Abu Bakr Saddiqi, all Algerians, and Abu Hassan al-Suri, a Syrian, were reportedly arrested in Georgia in 2002 and rendered by US agents to Jordan.[39] All but Saddiqi were said to have been arrested together in April 2002; it is not clear when Saddiqi was picked up.

Al-Tabuki mentioned Khayr al-Din al-Jaza'eri in his account, saying that he was "sent to Jordan in a private jet to be interrogated by Jordanian intelligence, who sought to extract from him information about Chechen fighters. And he was threatened to be falsely tied to a terrorist conspiracy against British interests, since he was originally a British resident." Khayr al-Din al-Jaza'eri is also mentioned in the written judgment of a high-profile French terrorism prosecution, the so-called "Chechen network" case.[40]

The current whereabouts of all four men are unknown, although it is possible that they were at some point transferred to their home countries-i.e., Algeria and Syria-for continued detention.

Several former prisoners said that one or more Chechens who had been brought to the GID detention facility by Americans were held there in 2002-2003. One such prisoner, who was held in GID custody in late 2002, told Human Rights Watch that at least one Chechen had originally been detained in Georgia. A different former GID prisoner, who was held in 2003, said that he had seen writing on his cell wall from a prisoner who wrote that he was from Chechnya.

Abu Hamza al-Tabuki

Abu Hamza al-Tabuki, a Saudi national, was arrested in Karachi, Pakistan, in late 2001. Two prisoners whom Human Rights Watch interviewed said that they spoke to him while he was in detention, and one of them provided Human Rights Watch an account of his stay in GID detention that al-Tabuki wrote after his release.

In his account, al-Tabuki explains that he was interrogated by US officials in Pakistan, and that the American told him that they were going to send him to a country where he could be interrogated "more freely." He reported that US interrogators thought that detention in Jordan "was more suitable for people like me because American laws tie their hands and they cannot apply the methods of the Jordanians."

Here is his description of what happened to him in GID detention in Amman:

As soon as I arrived at the prison, the money that I had was confiscated, my clothes were taken, and I was given the blue prison uniform. And from the first day, they began to interrogate me using the methods of terror and fear, torture and beating, insults and verbal abuse, and threatening to expose my private parts and rape me. I was repeatedly beaten, and insulted, along with my parents and family. Every time they took me, they blindfolded me; however, I was able to peak through the blindfold and see my interrogators, as well as many details of the prison building. As soon as I reached the torture room, the torturers began to violently beat me. They would tie my feet and beat me with a heavy stick. After which, my flesh in my feet would tear apart, they would untie the rope and order me to run across the courtyard, over saltwater. Throughout this, they would throw questions at me and demand answers to them, while kicking and beating me all over with sticks, including my sensitive parts.[41]

Al-Tabuki claimed that the point of the abuse was to obtain information, even false information:

The questions focused on Osama bin Laden and his wives and children, his location, and on members of al-Qaeda. I was shown pictures of bearded and non-bearded Yemeni, Saudi, Jordanian, and Egyptian individuals. I was asked the names of these individuals, and forced to identify them even if I didn't know them. Many times, I even made up names for them because I did not know who they were and was forced under physical duress to identify them.

They tortured me a great deal in order to make me confess to them about the American targets that al-Qaeda was planning to hit, even though I had no knowledge about that. They even forced me, through torture, to make up fictitious targets, about which they could report to the Americans. Their [American] masters would later discover that these were empty threats, and that such targets were made up under torture.[42]

A prisoner who was held with al-Tabuki in Jordan told Human Rights Watch that al-Tabuki was returned to Saudi Arabia in late 2002 or early 2003, and was released.

Ramzi bin al-Shibh

Ramzi bin al-Shibh, a Yemeni citizen, was arrested in Karachi, Pakistan, on September 11, 2002, and was held in CIA custody for several years. Alleged to be one of the main conspirators in the September 11 attacks, he was rendered by the United States to Jordan for an unknown period. In early September 2006, he was transferred to US military detention at Guantanamo, where he remains. He has yet to see a lawyer or an independent monitor who could report on his experiences since his arrest.

A former detainee in Jordan gave Human Rights Watch a detailed account of being held in a cell next to al-Shibh's in late 2002, on the third floor of the GID detention facility. The source said that he spoke with al-Shibh through the back window of his cell and sometimes through the small vent in the door of the cell. "We could never talk for long," he said, "maybe two minutes at most."

According to this source, al-Shibh claimed that he had been arrested in Pakistan, then brought to the US air base at Bagram, in Afghanistan, then flown to Jordan via Qatar. Al-Shibh described the flight from Bagram, saying that US officials put him in a diaper and wrapped a giant bandage around his body.

Al-Shibh reportedly said that he had been badly tortured in Jordanian custody. The forms of abuse included electric shocks, long periods of sleep deprivation, forced nakedness, and being made to sit on sticks and bottles (a form of sexual violence). The source did not recall al-Shibh saying anything about how the Americans treated him.

Al-Shibh reportedly claimed that he had been brought to Jordan together with two or three other prisoners. Human Rights Watch's source said that al-Shibh was the "most important" of the group, but he did not know anything about the others, except that one or more of them may have been Egyptian.

Ali al-Hajj al-Sharqawi

Ali al-Hajj al-Sharqawi (also known as Riad al-Sharqawi or Shergawi) is a Yemeni citizen who was arrested in Karachi in mid-February 2002, and rendered by the US to Jordan soon after. He is now held at Guantanamo.

Two former prisoners held by the GID spoke to Human Rights Watch about al-Sharqawi.[43] In addition, while at the GID detention facility in late 2002, al-Sharqawi himself wrote a long note describing his ordeal, which another prisoner managed to smuggle out, and which was provided to Human Rights Watch. Human Rights Watch also obtained a statement that al-Sharqawi wrote in 2006, two years after he was moved to Guantanamo.

In the 2006 statement, al-Sharqawi described his transfer to Jordan:

One evening around , all of a sudden, they took me out of my cell. They covered both my eyes and ears, and hooded me. I was also cuffed and shackled tightly, and I didn't know where they were going to take me. I was put in a car, and they played loud music. The car moved and we arrived at the airport. I was taken out of the car near an airplane. The noise of the engines was very loud. I was taken to the airplane through the back door. It was like a dark room. I was held tightly my neck forced down, and put on a chair, with guards on my left and right. The plane took off. A person came close and spoke with me very loudly in Arabic. He started questioning me. I asked him where we are going. He said God willing you'll go to your country. God save you from the Americans. Your mother is praying for you (this is a very common Arabic saying that shows ones good luck). The treatment that far was good (during the flight) excluding security matters. The aircraft landed.[44]

Like al-Tabuki, al-Sharqawi was surprised to find himself in Jordan:

I asked them where I was. I was in Sanaa? A voice answered No. You are with your Brothers in Amman (Jordan). I was being treated well so far. And I was surprised, Amman?? Why Amman? I asked. He said don't ask.

With this my two year ordeal started. I was kidnapped, not knowing anything of my fate, with continuous torture and interrogation for the whole of two years.

A prisoner held with al-Sharqawi in GID detention told Human Rights Watch that al-Sharqawi was badly beaten by GID interrogators. Al-Sharqawi described the interrogations, saying:

I was being interrogated all the time, in the evening and in the day. I was shown thousands of photos, and I really mean thousands, I am not exaggerating .... And in between all this you have the torture, the abuse, the cursing, humiliation. They had threatened me with being sexually abused and electrocuted. I was told that if I wanted to leave with permanent disability both mental and physical, that that could be arranged. They said they had all the facilities of Jordan to achieve that. I was told that I had to talk, I had to tell them everything.

Al-Sharqawi was held in GID detention for nearly two years. Flight records obtained by Human Rights Watch indicate that a Boeing 737, registration number N313P, linked to the CIA and other prisoner transports, traveled from Amman to Kabul on January 8, 2004, the date that al-Sharqawi claims that he was flown from Jordan to Kabul.[45] Al-Sharqawi told his lawyers about what happened on that trip. Their notes of his account state:

He was taken to the airport in a black hood that came down to his shirt. When [he and the Americans] arrived at the airport, they cut his clothes off, searched his anus and gave him diapers, shorts, a sleeveless shirt and plastic handcuffs. He stood in the room for an hour in handcuffs tied to the walls. They took pictures of him. Then they came for him, tied his feet together and tied his hands together. One other man was thrown into a luggage cart, and Shergawi was picked up like a sack and thrown on top of him. Then they carried him like a sack and threw him into the plane. Two men were already in the plane, and they were American.[46]

Upon arrival in Kabul, he was brought to a CIA proxy prison, with Afghan guards, where he stayed for about a month and a half. Next he was transferred to the US military detention facility at Bagram air base, and in September 2004 he was transferred to Guantanamo, where he remains. He claims that once, at Guantanamo, a chief interrogator warned him that if he did not cooperate he would be returned to Jordan.[47]

Hassan bin Attash

Hassan bin Attash (whom Jordanian former detainees remember as Hassan ba Attash) is a Yemeni born in Saudi Arabia. He is the younger brother of Walid bin Attash, an alleged Al Qaeda operative who spent more than three years in secret CIA custody before being transferred to Guantanamo in 2006. The younger bin Attash was approximately 17 years old on September 11, 2002, when he was arrested in Karachi, Pakistan, in a raid that resulted in the arrest of Ramzi bin al-Shibh and several other Yemenis.

Bin Attash has told his lawyers that during a four-day period after his arrest he was held in a Karachi jail, where he was hit and kicked repeatedly while being questioned by Pakistani and American interrogators. After three nights there, he was transferred to a US-run facility in Kabul, Afghanistan, which he and other prisoners know as the "Dark Prison."

Bin Attash claims that after three days in Afghanistan the UStransferred him to Jordan. He has told his lawyers that while in GID custody in Jordan, he was subject to severe torture by Jordanian interrogators, including sleep deprivation; being slapped in the face and ears; being beaten on his feet with large sticks and being forced to run on his bare feet afterwards.[48]

He has described his torture in detail to his lawyers, who summarized it as follows:

The main method of torture was carried out in the courtyard of the basement by masked guards dressed in black. The guards would tie a prisoner's legs together and hang them from the ceiling by their feet. They would then beat the prisoners on their toes with large sticks. (After repeated blows, Attash noted that his feet would become numb to the pain.) The guards would then pour hot water on the feet of the prisoners to bring back the feeling. On some occasions this water was salty; on others the salt water was icy. Attash was also occasionally forced to run on his bare feet after these beatings.[49]

A Jordanian who was detained with bin Attash remembered his mistreatment.[50] He said that bin Attash, like al-Sharqawi, was beaten more severely than him or most other prisoners. Also, he recalled, "the guards didn't allow ba Attash [bin Attash] to sleep. The guards would look in on him through the small window in his cell door. If they saw that his eyes were closed, they'd wake him up by slapping his face or spraying water on him."

A habeas petition filed in US federal court summarizes the treatment bin Attash endured:

On information and belief, Mr. Attash was seized in 2002 from his home in Karachi, Pakistan, when he was 17 years old .... [In September 2002], he was transferred by U.S. authorities to Jordan, where he was imprisoned for sixteen months and suffered abuse and torture at the hands of his captors. During his imprisonment in Jordan, Mr. Attash was, for a period of three months, tortured for twelve hours per day.[51]

Bin Attash says that he was returned from Jordan to Afghanistan in January 2004, almost certainly on the same flight as Sharqawi. His lawyer has related his account of the trip:

On approximately January 7, 2004, Attash was taken from the Jordan Intelligence to the airport (trip took less than one hour) where he was met by CIA officers who were dressed in black, and were wearing black masks with forehead flashlights. Attash was then flown back to Kabul.[52]

In September 2004 he was flown from Afghanistan to Guantanamo, where he remains in custody.

Khais (or Qais)

One former prisoner told Human Rights Watch that in early 2003 he was briefly held in a GID cell near a Kurd named Khais. Khais was said to be in his twenties, and was from Halabja, in the Kurdish region of Iraq.[53] The person said that Khais may have been arrested in Yemen and delivered to Jordan by US agents.

Unnamed Libyan (probably Ibn al-Sheikh al-Libi)

Another former prisoner detained at the GID facility in 2004 and 2005 claims that a guard spoke of a Libyan prisoner who had been rendered by the Americans. The rendered prisoner was reportedly held on the very top floor of the GID facility, away from all the other prisoners. Human Rights Watch's source said that the guard said that:

They were hiding some Libyan guy who had been handed over by the Americans to be interrogated. They didn't want the ICRC to know about him. And they didn't want the Libyan to know where he was. So they chose dark-skinned guards, and they put the guards in green trousers and yellow shirts, so the Libyan thought he was in Africa.

The source said that the Libyan figured out where he was, however, after one of the Jordanian officers accidentally spoke in front of him.

The source thought the prisoner's name was Ibn al-Sheikh al-Libi, but he was not certain. Human Rights Watch has learned through other sources that al-Libi (who the United States rendered to Egypt for a time as well) believes that he was held in Jordan for a couple of months.[54]

Unnamed Tunisian

Another former detainee, who was held by the GID in 2004, told Human Rights Watch that he was held in a cell adjoining that of a Tunisian prisoner who had been delivered to Jordan by US authorities. The Tunisian was said to have been unhappy because he had been in custody for a long time: "He complained that he had spent four months in GID, and before that three months in an American prison in Iraq."

The Tunisian reportedly said that he had been detained in northern Iraq by the Peshmerga (Kurdish militants), who handed him over to US authorities.[55] He said that he had been a mujahid (fighter) for five years. GID interrogators had reportedly showed him photos of other mujahideen whom he did not know. "They said that if he didn't confess they'd send him to Guantanamo or Tunisia," the former detainee told Human Rights Watch.

The former detainee said that he only saw the Tunisian once, through the vent in his cell door. He described the Tunisian as short, slim, balding, and in his early thirties. The Tunisian reportedly said that his father was dead, and that he was his mother's only source of support.

Jamil Qasim Saeed Mohammed

Jamil Qasim Saeed Mohammed, a Yemeni student who lived in Karachi, Pakistan, was reportedly flown to Jordan on a CIA-linked Gulfstream jet, registration number N379P, in the early morning hours of October 23, 2001.[56] Someone who witnessed the scene at the Karachi airport reported that Mohammed was shackled and blindfolded. He said that the plane arrived from Amman and started flying back there at

A Pakistani journalist quoted a source at the Karachi airport saying: "The entire operation was so mysterious that all persons involved in the operation, including US troops, were wearing masks."[57] He also claimed that a masked person filmed the operation.

Jamil Qasim Saeed Mohammed has not been seen or heard from since.

Mohamedou Ould Slahi

Mohamedou Ould Slahi is a 37-year-old Mauritanian citizen who voluntarily submitted himself for questioning by the Mauritanian authorities in September 2001 and again in November 2001. In the report of the US National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States (the 9/11 Commission), Slahi is described as "a significant al Qaeda operative," but these allegations have never been tested in court. Although he has acknowledged fighting in Afghanistan in the early 1990s, he claims that he broke all relations with al Qaeda in 1992.

Arrested and transferred to US custody in November 2001, Slahi has been detained without trial ever since. He has said that he was flown to Jordan on approximately November28, 2001, and that he was held in custody there for eight months. He claims that during that time he was hit in the face and slammed against a concrete wall many times by Jordanian interrogators, and that he sometimes heard crying and moaning, presumably from other prisoners. What happened to him in Jordan, he later said, was "beyond description."[58] He has said that he confessed to involvement in the 2000 plot to blow up US airports, because "in Jordan they made me crazy to admit I had something to do with it. Because there was so much pressure and mistreatment, I admitted to this."[59]

Slahi claims that he was flown from Jordan to Afghanistan on July 19, 2002. This is consistent with flight information from a known CIA detainee transport plane, registration number N379P, which flew from Amman to Kabul on that date. On the day he was transferred, he later explained, "they stripped me naked like my mom bore me, and they put new clothes on me."[60]

I was in chains, a very bad suit, I had lost so much weight in Jordan that I was like a ghost ... the Americans [had me put] on a diaper but psychologically I couldn't [urinate] in the diaper. I tried to convince myself that it was okay but I couldn't and I was exploding.[61]

After spending three weeks in US military custody at Bagram air base, Slahi was transferred to Guantánamo on August 4, 2002. He is still there now.

Jamal al-Mar'i

Jamal al-Mar'i, a Yemeni who is currently being held at Guantanamo, was arrested at his home in Karachi, Pakistan, on September 23, 2001.[62] The arrest was carried out by a joint Pakistani-US team of operatives. Upon his arrest, he was taken to a Pakistani jail where he was held for approximately a month. While held at this facility, al-Mar'i claims that he was interrogated two or three times during a single week by US personnel, who he believes were intelligence agents. In late October 2001, al-Mar'i was rendered to Jordan, where he was held in the custody of the GID.

Al-Mar'i, like other rendered prisoners, has said that he was hidden from the ICRC during their regular visits to the facility, generally in the basement. During one of the ICRC's visits, however, al-Mar'i was "not taken into the basement and was discovered by the ICRC." Unlike other rendered prisoners, al-Mar'i has not claimed that he was tortured while in GID custody.

Al-Mar'i has told his lawyers that he was imprisoned for four months in Jordan. In mid-2002, he was taken to Guantanamo, where he remains.

International Legal Standards

The systematic rendition of individuals to Jordan by the United States in the years following the September 11 attacks violated several fundamental human rights guarantees. These include the prohibitions on arbitrary detention, torture and cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment, and enforced disappearance.[63]

The Jordanian government violated both national law and international human rights law by torturing and otherwise mistreating rendered detainees, by detaining them without charge or trial, and by holding them incommunicado, without contact or visits by family members or legal counsel.

By rendering prisoners to Jordan, the United States specifically violated its obligations under the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (Convention against Torture), which it ratified in 1994.[64] The Convention against Torture defines torture as "any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as obtaining from him or a third person information or a confession" and when "inflicted by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity."[65] States violate the Convention against Torture not only by directly inflicting torture, like Jordan, but also, under article 3, when they "expel, return ('refouler') or extradite a person to another State where there are substantial grounds for believing that he would be in danger of being subjected to torture."[66]

Rendition to torture is thus a clear violation of the prohibition against torture. In 2006, the UN Committee against Torture, the international expert body responsible for monitoring state compliance with the Convention against Torture, expressed concern with the US contention that the non-refoulement obligation under the convention did not extend to persons detained outside of the United States. It maintained that the US government's "rendition of suspects, without any judicial procedure, to States where they face a real risk of torture" was a violation of the Convention against Torture.[67] The committee called upon the United States to:

apply the non-refoulement guarantee to all detainees in its custody, cease the rendition of suspects, in particular by its intelligence agencies, to States where they face a real risk of torture, in order to comply with its obligations under article 3 of the Convention. The State party should always ensure that suspects have the possibility to challenge decisions of refoulement.[68]

Notably, in the case of Agiza v. Sweden, the Committee against Torture held that Sweden violated the Convention against Torture when it assisted in the CIA's rendition to Egypt of Egyptian asylum seeker Ahmed Agiza in December 2001. The Committee found that "it was known, or should have been known, to [Sweden]'s authorities at the time of [Agiza]'s removal that Egypt resorted to consistent and widespread use of torture against detainees, and that the risk of such treatment was particularly high in the case of detainees held for political and security reasons."[69] The Committee also stated that "an inability to contest an expulsion decision before an independent authority . . . [is] relevant to a finding of a violation of [the Convention]" because it violates "the procedural obligation to provide for effective, independent and impartial review required by article 3 of the Convention."[70]

Importantly, the Committee rejected Sweden's argument that it should be not be found responsible because it had obtained assurances from the Egyptian government that Agiza would not be ill-treated. As the Committee emphasized, the "procurement of diplomatic assurances, which, moreover, provided no mechanism for their enforcement, did not suffice to protect against this manifest risk."[71] In its 2006 Conclusions and Recommendations to the United States, the Committee called upon the US government to "provide detailed information to the Committee on all cases since 11 September 2001 where assurances have been provided."[72]

Numerous other international authorities have criticized the use of diplomatic assurances in cases involving returns to a risk of torture, finding that they do not provide effective protection.[73] Human Rights Watch has shown, as an empirical matter, that such assurances are often unreliable, and that persons who have been returned to their home countries on the basis of such assurances have faced torture and other abuse.[74] The brutal torture endured by Maher Arar-a Canadian-Syrian dual national whom the United States rendered to Syria, via Jordan-is perhaps the most notorious example of this problem.[75]

International human rights law provides victims of rights violations the right to an effective remedy. In cases where people have endured torture as a result of US actions, they should be able to seek legal redress in court. The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights provides that states shall "ensure that any person whose rights or freedoms as herein recognized are violated shall have an effective remedy" for abuses by persons acting in an official capacity, that anyone claiming such a remedy shall have this right determined by competent governmental authorities, and that states shall ensure that remedies are enforced.[76]

Under the Convention against Torture, in addition, torture victims have a right of access to the courts in order to obtain fair and adequate compensation.[77] To date, however, the US courts have proven hostile to victims of rendition, dismissing a lawsuit brought by a group of rendition victims that include Ahmed Agiza, Abou Elkassim Britel and Binyam Mohamed, as well as an earlier suit brought by rendition victim Maher Arar.[78] While the Canadian government acknowledged wrongdoing and compensated Arar for his suffering, the US government has done neither. Indeed, despite heavy international criticism, the US government has never acknowledged that the CIA's rendition program has resulted in abuses or has violated the law.[79]

Acknowledgements

This report was written by Joanne Mariner, director of Human Rights Watch's Terrorism and Counterterrorism Program. It is based on research conducted by Mariner, Christoph Wilcke, a researcher with the Middle East and North Africa Division, and John Sifton, formerly a senior researcher with the Terrorism and Counterterrorism Program. It also benefited from comments from Julia Hall, senior counsel with the Terrorism and Counterterrorism Program. It was edited by James Ross, legal and policy director, and Joe Saunders, deputy program director. Thodleen Dessources, senior associate, provided production assistance, as did Grace Choi, publications specialist; Jim Murphy, online editor; Veronica Matushaj and Anna Lopriore, photography specialists, and Fitzroy Hepkins, production manager.

We thank the government of Jordan for granting us access to interview prisoners in government custody. We are also grateful for the assistance of several lawyers representing detainees at Guantanamo, including Marc Falkoff, David Remes, and Kristin Wilhelm, and the team at the Center for Constitutional Rights, including Jessica Baen, Wells Dixon, Susan Hu, and Shane Kadidal. And we would especially like to express our gratitude to the former GID detainees who spoke with Human Rights Watch, despite concern that they might face repercussions from the authorities.

Human Rights Watch would also like to acknowledge with appreciation the generous support of the JEHT Foundation, Atlantic Philanthropies, and the Normandie Foundation for our research on US abuses in the "war on terror."

[1]Human Rights Watch is withholding the names of our sources in order to protect them from any possible reprisals. They were interviewed in Jordan in August 2007, October 2007, and February 2008.

[2] See Human Rights Watch, "Black Hole: The Fate of Islamists Rendered to Egypt," Vol. 17, No. 5(E), May 2005, pp. 19-24 (describing US involvement in the rendition to Egypt of Tal'at Fu'ad Qassim, Ahmad Ibrahim al-Sayyid al-Naggar, Shawqi Salama Mustafa, Muhammad Hassan Mahmud Tita, Ahmad Isma'il 'Uthman, and 'Issam 'Abd al-Tawab 'Abd al-Alim); Jane Mayer, "Outsourcing Torture," New Yorker, February 14, 2005 (describing the genesis of the rendition program).

[3] See John Barry, Michael Hirsh, and Michael Isikoff, "The Roots of Torture," Newsweek, May 24, 2004.

[4] J. Cofer Black, Unclassified Testimony before the Senate Intelligence Committee, US Congress, 107th Congress, 2nd Session, September 26, 2002.

[5] President Bush reportedly signed the directive, which remains classified, on September 17, 2001. Although the precise wording of the directive is not known, it has been widely reported that, among other things, the directive greatly expanded the CIA's power to transfer suspected terrorists to foreign countries for detention and interrogation. See Douglas Jehl and David Johnston, "Rule Change Lets C.I.A. Freely Send Suspects Abroad to Jails," New York Times, March 6, 2005; American Civil Liberties Union, "CIA Finally Acknowledges Existence of Presidential Order on Detention Facilities Abroad," November 14, 2006 (explaining that the CIA acknowledged the existence of the directive in response to an ongoing ACLU lawsuit).

[6] By way of comparison, seven people are known to have been rendered to Egypt by the CIA since 2001.

[7] Condoleezza Rice, "Remarks upon her Departure for Europe," December 5, 2005.

[8] Hearing of the Senate Armed Services Committee on the future of military commissions following the US Supreme Court's decision in Hamdan v. Rumsfeld. Federal News Service, transcript of hearing, August 2, 2006.

[9] Michael Scheuer, "Exporting Detainees," International Herald Tribune, March 12, 2005.

[10] See generally Human Rights Watch, "'Empty Promises:' Diplomatic Assurances No Safeguard against Torture," Vol. 16, No. 4 (D), April 2004; Human Rights Watch, "Still at Risk: Diplomatic Assurances No Safeguard Against Torture," Vol. 17, No. 3(D), April 2005. For information on the ineffective of diplomatic assurances used in returns to Jordan, see Julia Hall, Witness Statement, November 6, 2006 (available at http://www.hrw.org/backgrounder/eca/ecaqna1106/witnessstatementjuliahall.pdf).

[11] Jane Mayer, "Outsourcing Torture," New Yorker, February 14, 2005.

[12] Remarks of Central Intelligence Agency Director Gen. Michael V. Hayden at the Council on Foreign Relations, September 7, 2007.

[13] The General Intelligence Department was established in 1964. Law No. 24 of 1964 mandates the GID to work "for the security and safety" (salama) of Jordan. The law stipulates that the prime minister shall designate the GID's specific duties in writing and that these are to remain confidential.

The king of Jordan appoints the GID director, who reports to the prime minister. GID officers are considered military personnel. For detailed information about the GID and its practices, see Human Rights Watch, "Suspicious Sweeps: The General Intelligence Department and Jordan's Rule of Law Problem," Vol. 18, No. 6(E), September 2006.

[14]Human Rights Watch interview with former CIA official, Washington, DC, February 16, 2006.

[15] Ken Silverstein, a journalist who follows intelligence issues closely, claims that the GID "has surpassed Israel's Mossad as America's most effective allied counter-terrorism agency in the Middle East." A former CIA official told Silverstein that "Jordan's intelligence partnership with the U.S. is so close ... that the CIA has had technical personnel 'virtually embedded' at GID headquarters." Ken Silverstein, "U.S. partnership with Jordan was targeted," Los Angeles Times, November 12, 2005.

[16] The falaqa technique has a long history; it is believed to have been used in the Arab world since the tenth century. As one expert on torture explained, "[t]he soles of the feet are not thickly muscled, and so caning or whipping them is especially painful. Depending on the weight of the rod and the intensity and frequency of the blows, this practice can yield mildly swollen feet to broken bones that damage a person permanently." Part of attraction of this method, in modern times, is that its physical traces disappear quickly. Darius Rejali, Torture and Democracy (Princeton and Oxford: PrincetonUniversity Press, 2007), pp. 273-76.

[17] Report of the Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, Manfred Nowak, Addendum: Mission to Jordan, U.N. Doc. A/HRC/4/33/Add.3 (5 January 2007).

[18] See, for example, Amnesty International, "Jordan: 'Your confessions are ready for you to sign': Detention and torture of political suspects," MDE 16/005/2006, July 2006; Human Rights Watch, "Suspicious Sweeps."

[19] US Department of State, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, 2001 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices, March 4, 2002.

[20] In the last two weeks of August 2007, Human Rights Watch was given permission to conduct a series of visits to the GID detention facility. Besides being allowed to see the entire building, Human Rights Watch researchers were granted access to certain prisoner registries and other official information. During this period, our investigators also visited five Jordanian prisons and interviewed more than 100 prisoners in private.See Human Rights Watch, "Jordan: Rampant Beatings in Prison Go Unpunished," August 30, 2007.

[21] In this report, references to the second, third, and fourth floors correspond to the American usage, by which the ground floor is the first floor.

[22] The cells are numbered, so that cell numbers 1 through 31 are on the ground floor, 32 through 63 on the second floor, and 64 through 95 on the third floor.

[23] Several journalists have reported on renditions to Jordan, as well as on CIA prisons allegedly located there. Their reports have been incomplete, however, and based on information received from Guantanamo detainees and unnamed intelligence sources, rather than from Jordanian detainees held with the rendered suspects. See, for example, Yossi Melman, "CIA holding Al-Qaida suspects in secret Jordanian lockup," Haaretz, October 13, 2004 (stating that Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, Ramzi bin al-Shibh, Abu Zubaydah, and Hambali were among at least 11 senior Al Qaeda suspects held in CIA custody in Jordan); Ken Silverstein, "U.S. partnership with Jordan was targeted," Los Angeles Times, November 12, 2005 (stating that Jamal Mara'i and Hassan bin Attash were rendered to Jordan); Farah Stockman, "7 detainees report transfer to nations that use torture," Boston Globe, April 26, 2006 (stating that Mohamedou Ould Slahi, Jamal Mar'i, Hassan bin Attash, and Al-Shaqwi (Ali al-Hajj al-Sharqawi) were rendered to Jordan); and Craig Whitlock, "Jordan's Spy Agency: Holding Cell for the CIA," Washington Post, December 1, 2007 (stating that Ali al-Hajj al-Sharqawi, Jamil Qasim Saeed Muhammed, and Jamal Ma'ri were sent to Jordan, and Ramzi bin al-Shibh may have been). See also Amnesty International, "Jordan: 'Your confessions are ready for you to sign': Detention and torture of political suspects," July 2006 (describing post-September 2001 cases of Jamal Ma'ri, Mohamedou Ould Slahi, Jamil Qasim Saeed Muhammed, Abo al-Hitham Sharqawi, Hassan bin Attash, and Maher Arar).

[24] In contrast, all the people whom the US rendered to Egypt prior to September 2001 were Egyptian citizens over whom the Egyptian government was clearly eager to obtain custody. Moreover, nearly all of the people known to have been rendered to Egypt after September 2001 are also Egyptian citizens, although in some of the cases it does not appear that the Egyptian government had a strong interest in detaining them.

[25] The two men are Muhammad Faraj Bashmilah and Salah Nasir Salim 'Ali Qaru (Darwish). They were arrested in October and September 2003, respectively. After relatively brief periods of detention in Jordan, they were transported by the US to Afghanistan where they were secretly detained. See Amnesty International, "USA/Yemen: Secret Detention in CIA 'Black Sites,'" AMR 51/177/2005, November 2005.

[26] Note from Ali al-Hajj al-Sharqawi, written approximately October 2002 (on file at Human Rights Watch).

[27] Lawyers' notes, undated (2007).

[28] See Masood Anwar, "Mystery Man Handed over to US Troops in Karachi," The News International (Pakistan), October 26, 2001; Alissa Rubin, "Pakistan Hands Over Man in Terror Probe," Los Angeles Times, October 28, 2001; Rajiv Chandrasekaran and Peter Finn, "U.S. Behind Secret Transfer of Terror Suspects," Washington Post, March 11, 2002.

[29] Note that some of these names are likely nicknames rather than real names: for example, "al-Suri" means "the Syrian"; "al-Jaza'eri" means "the Algerian."

[30] See Dana Priest, "CIA Holds Terror Suspects in Secret Prisons," New York Times, November 2, 2005; Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights, Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, "Secret detentions and illegal transfers of detainees involving Council of Europe member states," Doc. 11302 rev., June 11, 2007.

[31] See Human Rights Watch, "Ghost Prisoner: Two Years in Secret CIA Detention," February 2007, pp. 31-32.

[32] Many of those who spent time in secret CIA prisons or were rendered to other countries were later transferred to Guantanamo.

[33] The US government acknowledged this pressure in the Georgia section in its annual terrorism survey, Patterns of Global Terrorism 2002, which says: "In 2002, the United States strongly urged Georgia to regain control of the Pankisi Gorge where third-country terrorists with links to al-Qaida had established themselves. These extremists threatened Georgia's security and stability, as well as Russia's." US Department of State, Patterns of Global Terrorism, April 30, 2003, p. 29. The US also provided military training to Georgian troops, with the stated goal of "clear[ing] Georgia's Pankisi Gorge region of foreign fighters." Ibid., p. 154.

[34] Verdict, Tribunal de Grande Instance de Paris, case of Marbak Lebik Benhamed et autres, June 14, 2006, p. 88.

[35] Abu Hamza al-Tabuki, Jordanian Intelligence and its Services to US Intelligence in its War on the Mujahidun and Iraq, written in early 2003 (hereinafter al-Tabuki account) (copy on file at Human Rights Watch. On a visit to the GID detention facility in August 2007, Human Rights Watch was prevented from freely visiting the guards' quarters, which are located in the outer walls of the same two triangular buildings, easily accessible through doors that were locked at the time of our visit. We were able to see the guards' washroom and one large room with bunk beds for guards. It was clear that within the larger building there were rooms in which prisoners could be hidden.

[36] The FBI posted the names of 17 suspected terrorists to the list on February 11, 2002. By late March 2002, his name had been removed from the list. See http://www.fbi.gov/terrorinfo/terrorismsi.htm. Arabic names can be transcribed into Latin script in several different ways, leading.

[37] Abu Hamza al-Tabuki remembered that Abu Mu'ath was mostly held in cell number 87, on the third floor of the GID detention facility. Al-Tabuki account, p. 3. He also said Abu Mu'ath's real name was Ahmad Ibrahim Abu al-Hasana.

[38] The memo states: "The detainee was recruited in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia [sometime before August 2001], by Abu Mua'th, who gave the detainee an airline ticket to Karachi, Pakistan, 3000 Saudi Riyals ($799 USD) and a passport." Department of Defense, Office for the Administrative Review of the Detention of Enemy Combatants at US Naval Base Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, "Unclassified Summary of Evidence for Administrative Review Board in the Case of Khowlan, Abdul Rahman Mohammed Hussein," June 29, 2005. The summary of evidence memo used in Khowlan's case the following year omits the name of Abu Mu'ath, but identifies him as "a Saudi in his early 30s," which corresponds to al-Jeddawi's description. Department of Defense, Office for the Administrative Review of the Detention of Enemy Combatants at US Naval Base Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, "Unclassified Summary of Evidence for Administrative Review Board in the Case of Al Khawlan, Abd al Rahman Muhammad Husayn," May 2, 2006.

[39] Human Rights Watch does not has any information about who arrested them. Another Algerian who was picked up in Georgia in April 2002, however, who is now held at Guantanamo, claims that he and two others were abducted by the "Mafia" and handed over to American officials for a "brief case full of money." Transcript of Combatant Status Review Tribunal hearing, Soufian Abar Huwari, ISN 1016, Set 21, pp. 1663-64.

[40] Verdict, Tribunal de Grande Instance de Paris, case of Marbak Lebik Benhamed et autres, June 14, 2006, p. 88.

[41] Al-Tabuki account.

[42] Ibid.

[43] He is also mentioned in al-Tabuki's account.

[44] Undated statement of Shergawi [Sharqawi] Ali Al-Haj, p. 1 (copy on file at Human Rights Watch).

[45] Al-Sharqawi told his lawyers that he was taken out of his cell at 11 p.m. on January 7, 2004, put in a car, and handed over to the Americans. He was placed on an airplane to Kabul later that same night. Al-Sharqawi lawyers' notes, p. 11.

[46] Ibid. As discussed below, the other prisoner he was transferred with was Hassan bin Attash.

[47] Shergawi statement, p. 10.

[48] Memorandum from Brent Starks, June 14, 2006.

[49] Ibid.

[50] Abu Hamza al-Tabuki, who was also held with bin Attash, said that he was rendered to Jordan by the Americans for interrogation. He remembered that bin Attash was held in cell number 85, on the third floor of the GID detention facility. Al-Tabuki account, p. 4.

[51] Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus, Attash v. Bush, Case No. 05-CV-1592, August 9, 2005, p. 4.

[52] Memorandum from Brent Starks, June 14, 2006.

[53] Al-Tabuki also claimed that there were Kurds in GID detention whom the Americans had handed over to the GID.

[54]Human Rights Watch interview, London, March 18, 2007.

[55]Human Rights Watch has also interviewed a Jordanian with a similar story. He claims that he was arrested in the Kurdish area of Iraq by Kurdish forces in January 2004, handed over to US forces, and held for 38 days in US custody in Baghdad. Then he was flown to Jordan on a small plane and transferred to GID custody. Human Rights Watch interview, Amman, October 23, 2007.

[56] Stephen Grey, Ghost Plane: The True Story of the CIA Torture Program (New York: St. Martin's Press, 2006), p. 272.

[57] Masood Anwar, "Mystery Man Handed over to U.S. Troops in Karachi," The News International (Pakistan), October 26, 2001.

[58] Mohamedou Ould Slahi, Annual Review Board transcript, Set 8, undated, p. 203.

[59] Mohamedou Ould Slahi, summarized transcript of Combatant Status Review Tribunal, undated, p. 32.

[60] Mohamedou Ould Slahi, Annual Review Board transcript, Set 8, undated, p. 203.

[61] Ibid.

[62] Al-Mar'i's registration number at Guantanamo is 577. According to weight records kept by the US military and made public as a result of Freedom of Information Act litigation, al-Mar'i entered Guantanamo on approximately May 1, 2002.

[63] See, for example, International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), G.A. res. 2200A (XXI), 21 U.N. GAOR Supp. (No. 16) at 52, U.N. Doc. A/6316 (1966), 999 U.N.T.S. 171, entered into force Mar. 23, 1976, arts. 7 & 9; Declaration on the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearances, G.A. res. 47/133, 47 U.N. GAOR Supp. (No. 49) at 207, U.N. Doc. A/47/49 (1992). The United States ratified the ICCPR in 1992.

[64] Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, G.A. res. 39/46, annex, 39 U.N. GAOR Supp. (No. 51) at 197, U.N. Doc. A/39/51 (1984), entered into force June 26, 1987.

[65] Convention against Torture, art. 1. The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), also bars torture and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. ICCPR, art. 7.

[66] Convention against Torture, art. 3.

[67] Committee against Torture, Conclusions and Recommendations of the Committee against Torture Concerning the Second Report of the United States of America, U.N. Doc. CAT/C/USA/CO/2, 25 July 2006, para. 20 (stating that article 3 applies extraterritorially); see also Second Periodic Report of the United States of America to the Committee Against Torture (May 6, 2005), para. 27.

[68] Committee against Torture, Conclusions and Recommendations of the Committee against Torture Concerning the Second Report of the United States of America, para. 20.

[69] Committee against Torture, Agiza v. Sweden, U.N. Doc. CAT/C/34/D/233/2003, May 20, 2005, para. 13.4.

[70] Ibid., paras. 13.7-13.8.

[71] Ibid., para 13.4.

[72] Committee against Torture, Conclusions and Recommendations of the Committee against Torture Concerning the Second Report of the United States of America, para. 21.

[73] See, for example, "Report of the special rapporteur on the question of torture," U.N. Commission on Human Rights, 62nd Session, UN Doc. E/CN.4/2006/6, p. 2 (stating that "Diplomatic assurance ... are not legally binding [and] are ineffective and unreliable in ensuring the protection of returned persons").

[74] See Human Rights Watch, "'Empty Promises:' Diplomatic Assurances No Safeguard against Torture," Vol. 16, No. 4 (D), April 2004; Human Rights Watch, "Still at Risk: Diplomatic Assurances No Safeguard Against Torture," Vol. 17, No. 3(D), April 2005.

[75] Arar was arrested by US officials at JohnF.KennedyAirport in New York on September 26, 2002, held for nearly two weeks in immigration detention, and subsequently rendered to Jordan, from which he was driven to Syria. At the Far Falestin detention center in Syria, he was held in detention without charge for more than a year, tortured, and exposed to abusive conditions of confinement. See "Report of the Commission of Inquiry into the Actions of Canadian Officials in Relation to Maher Arar," September 18, 2006.

[76]ICCPR, art. 2(3). The UN Human Rights Committee in its General Comment 31, Nature of the General Legal Obligation on States Parties to the Covenant, U.N. Doc. CCPR/C/21/Rev.1/Add.13 (2004), at paragraph 10, states with respect to states' jurisdiction for human rights violations:

States Parties are required by article 2, paragraph 1, to respect and to ensure the Covenant rights to all persons who may be within their territory and to all persons subject to their jurisdiction. This means that a State Party must respect and ensure the rights laid down in the Covenant to anyone within the power or effective control of that State Party, even if not situated within the territory of the State Party.