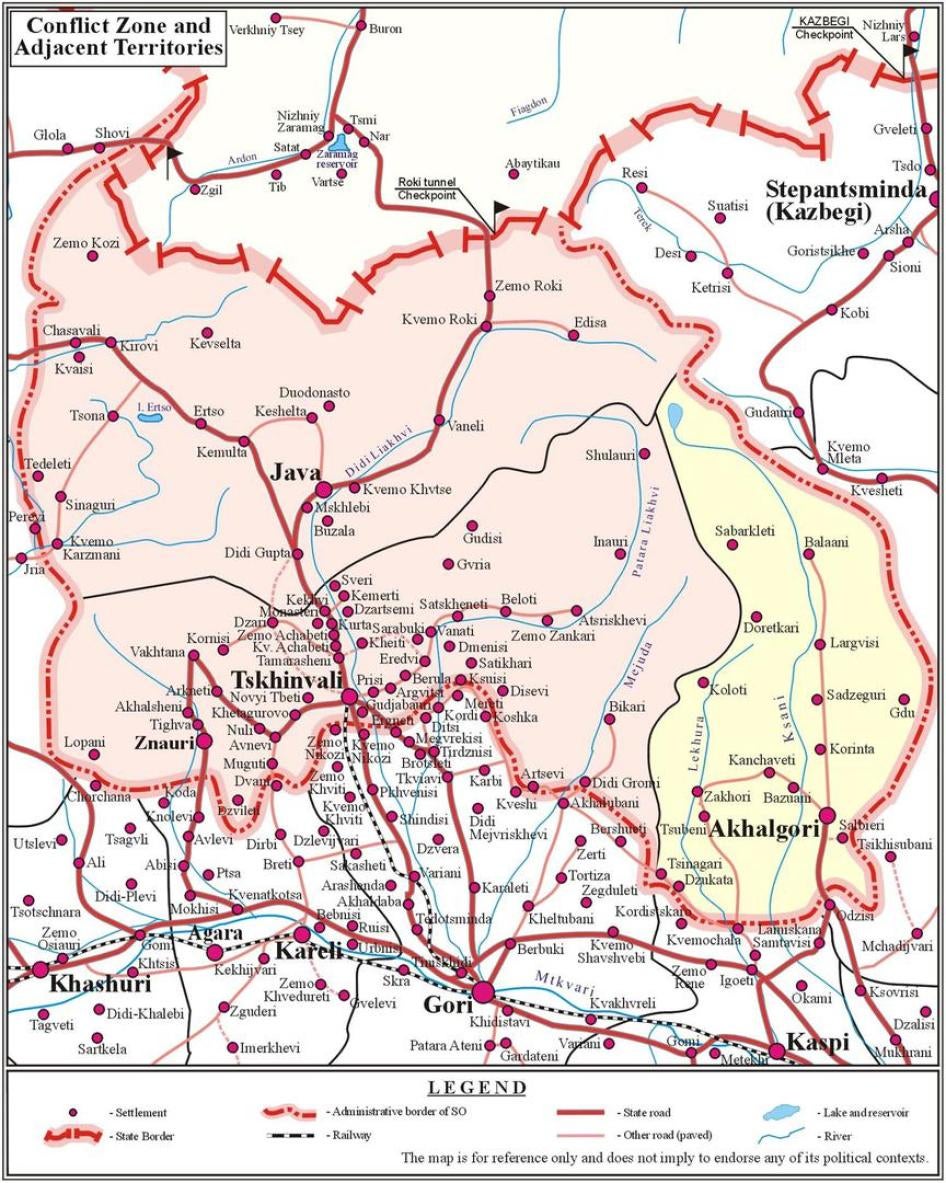

Map of South Ossetia

Executive Summary

Overview

The armed conflict over South Ossetia lasted one week in August 2008 and will have consequences for lifetimes and beyond. The conflict and its aftermath have seen lives, livelihoods, homes, and communities devastated in South Ossetia and bordering districts of Georgia. A significant casualty of the conflict was all sides' respect for international humanitarian law.

South Ossetia is a breakaway region of Georgia that shares a border and has very close ties with Russia. The armed conflict, in the making since spring 2008, started August 7 with Georgia's military assault in South Ossetia and Russia's military response the following day, and lasted until a ceasefire on August 15, with Georgian forces in retreat and Russian forces occupying South Ossetia and, temporarily, undisputed parts of Georgia.[1] The week of open conflict, and the many subsequent weeks of rampant violence and insecurity in the affected districts, took a terrible toll on civilians, killing hundreds, displacing tens of thousands, and causing extensive damage to civilian property. Today, there is an acute need for accountability for all perpetrators of violations of human rights and humanitarian law, and for security conditions to allow all displaced persons to return in safety and dignity to their homes.

Human Rights Watch carried out a series of research missions in Russia and Georgia, including in South Ossetia, focusing on violations by all parties to the conflict. We interviewed more than 460 victims, witnesses, and others, and looked at reporting (and misreporting) of the conflict in Russia and in Georgia. The international legal framework within which Human Rights Watch examined the conflict includes international humanitarian law-chiefly the Geneva Conventions-relating to the conduct of hostilities, humane treatment, and occupation; and international human rights law, including international law concerning displaced persons and the right to return.

Human Rights Watch found:

- In a number of instances Georgian forces used indiscriminate and disproportionate force in artillery assaults on South Ossetia, and in some cases used disproportionate force in their ground assault. The majority of these instances derived from Georgia's use of multiple rocket launching systems, which cannot distinguish between civilian and military objects, in areas populated by civilians. Many civilians were killed or wounded.

- In a number of instances in South Ossetia and in undisputed Georgian territory Russian forces violated international humanitarian law by using aerial, artillery, and tank fire strikes that were indiscriminate, killing and wounding many civilians.

- Cluster munitions were used by Russian and Georgian forces, causing civilian deaths and putting more civilians at risk by leaving behind unstable "minefields" of unexploded bomblets. Their use and impact on civilians in the conflict demonstrates why in December 2008, 94 governments signed up to a comprehensive treaty to ban cluster munitions, which had been negotiated just months before the conflict commenced.

- As an occupying power in Georgia, Russia failed overwhelmingly in its duty under international humanitarian law to ensure, as far as possible, public order and safety in areas under its effective control, instead allowing South Ossetian forces, including volunteer militias, to engage in wanton and widescale pillage and burning of Georgian homes and to kill, beat, rape, and threaten civilians.

- After Georgian forces withdrew from South Ossetia on August 10, South Ossetian forces over a period of weeks deliberately and systematically destroyed ethnic Georgian villages in South Ossetia that had been administered by the Georgian government. They looted, beat, threatened, and unlawfully detained numerous ethnic Georgian civilians, and killed several, on the basis of the ethnicity and imputed political affiliations of the residents of these villages, with the express purpose of forcing those who remained to leave and ensuring that no former residents would return. From this, Human Rights Watch has concluded that South Ossetian forces attempted to ethnically cleanse these villages. Approximately 22,000 villagers, the majority of whom had fled South Ossetia before the conflict started, remain displaced.

- In committing this violence, South Ossetian forces egregiously violated multiple obligations under humanitarian law, for which there must be individual criminal accountability and prosecution for war crimes where appropriate. To the extent that a number of these prohibited acts were committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack directed against the civilian population, they may be prosecuted as crimes against humanity.

- Residents of Akhalgori district-an area in the east of South Ossetia populated mostly by ethnic Georgians and currently occupied by Russian forces-face threats and harassment by militias and anxiety about a possible closure of the district's administrative border with the rest of Georgia. Both factors have caused great numbers of people to leave their homes for undisputed Georgian territory.

- During the time when Russian forces occupied Georgian territory south of the South Ossetian administrative border, Ossetian militias looted, destroyed, and burned homes on a wide scale, deliberately killed at least nine civilians, and raped at least two. Russian forces were at times involved in the looting and destruction, either as passive bystanders, active participants, or by providing militias with transport into villages.

- Georgian forces beat and ill-treated at least five of the 32 Ossetians detained in August in the context of the armed conflict.

- After the withdrawal of Georgian forces from South Ossetia, South Ossetian forces, at times together with Russian forces, arbitrarily detained at least 159 ethnic Georgians. South Ossetian forces killed at least one detainee and subjected nearly all of them to inhuman and degrading treatment and conditions of detention. They also tortured at least four Georgian prisoners of war and executed at least three. All of these acts are war crimes, for which individual criminal accountability must be established.

This report measures each party's compliance with obligations under international law, rather than measure it against the conduct of the other party. Exposing violations committed by one party does not excuse or mitigate violations committed by another party. Which party started the conflict has no bearing on parties' obligations to adhere to international humanitarian and human rights law and to hold violators accountable. Those seeking answers to questions about who committed worse, or more violations, or who bears responsibility for starting the conflict, will not find them in this report.

* * *

Human Rights Watch urges the Georgian and Russian governments to investigate and hold accountable those from their respective forces responsible for international humanitarian law violations, including war crimes. As it exercises in effective control over South Ossetia, Russia should investigate and hold accountable South Ossetian forces responsible for war crimes and other violations of international humanitarian and human rights law. The Russian and Georgian governments should provide compensation for civilian damage and destruction caused by violations of international humanitarian law for which they are respectively responsible.

The permanent forced displacement of thousands of people cannot be countenanced. As it exercises effective control over South Ossetia, Russia has an obligation to provide security to all persons living there, regardless of ethnicity; this is especially urgent in Akhalgori district. Ethnic Georgians displaced from South Ossetia should be allowed to voluntarily return. Russia should publicly promote and implement the right of all persons displaced by the conflict, without regard to their ethnic background or imputed political affiliations, to return and live in their homes in South Ossetia in safety and dignity. Russia should prevail on South Ossetian authorities to publicly acknowledge this and to facilitate returns.

Brief Chronology of the Armed Conflict

After months of escalating tensions between Russia and Georgia and following skirmishes between Georgian and South Ossetian forces, on August 7, 2008, Georgian forces launched an artillery assault on Tskhinvali, South Ossetia's capital, and outlying villages. Assaults by Georgian ground and air forces followed. Russia's military response began the next day, with the declared purpose of protecting Russian peacekeepers stationed in South Ossetia and residents who had become Russian citizens in recent years. Beginning on August 8, Russian ground forces from the 58th Army crossed into South Ossetia and Russian artillery and aircraft hit targets in South Ossetia and undisputed Georgian territory. South Ossetian forces consisting of several elements-South Ossetian Ministry of Defense and Emergencies, South Ossetian Ministry of Internal Affairs, South Ossetian Committee for State Security, volunteers, and Ossetian peacekeeping forces-also participated in the fighting.

Georgian commanders ordered their troops to withdraw from South Ossetia on August 10, and two days later Russian forces moved into and occupied undisputed Georgian territory south of the administrative border with South Ossetia, including the city of Gori. In a separate operation from the west, moving through the breakaway region of Abkhazia (also supported by Russia), Russian forces also occupied the strategically important cities of Poti, Zugdidi, and Senaki in western Georgia.

Russia said that its forces completed their withdrawal from undisputed Georgian territory on October 10, in accordance with an August 15 ceasefire agreement between Russia and Georgia brokered by the French European Union presidency. The Georgian government disputes this, pointing to Russian forces' presence in Perevi, a village on the South Ossetian administrative border, as well as Akhalgori.

Violations by Georgian Forces

Indiscriminate and disproportionate use of force

During the shelling of Tskhinvali and neighboring villages and the ground offensive that followed, Georgian forces frequently failed to abide by the obligation to distinguish between military targets that can be legitimately attacked, and civilians, who may not be targeted for attack. This was compounded by Georgia's failure to take all feasible measures to avoid or minimize civilian casualties. While Human Rights Watch found no evidence that Georgian forces sought to deliberately target civilians, from our research Human Rights Watch concluded that Georgian forces demonstrated disregard for the protection of civilians during the shelling campaign, resulting in large-scale damage to civilian objects and property, and civilian casualties.

The sole fact of civilian casualties or destruction of civilian objects is not an indication that a violation of international humanitarian law occurred. What is important to seek to determine is whether there was evidence of a legitimate military target in the attack area at the time, and how that target was attacked. Circumstances did not always allow such a determination. Yet many of the attacks on South Ossetia during the brief conflict can be clearly attributed to Georgian forces-based on witness accounts, the direction of the attack, and the timing of the damage in light of the advance of Georgian forces.

In many cases Human Rights Watch researchers found no evidence of military objectives in the area under attack, while in many others we found that Georgian attacks struck legitimate military targets, causing combatant and, in some cases, collateral civilian casualties. In some cases we investigated, evidence suggests that the Georgian attacks against lawful military objectives may have been disproportionate, as the expected loss of civilian life or destruction of civilian property would have have expected to exceed any anticipated military gain.

The massive shelling of Tskhinvali and neighboring villages by Georgian forces was indiscriminate because, at the very least, the Georgian military effectively treated a number of clearly separated and distinct military objectives as a single military objective in an area that contained a concentration of civilians and civilian objects. In a number of artillery attacks Georgian forces failed to take all feasible precautions to minimize loss of life or injury to civilians.

Georgia's use of multiple rocket launching systems, such as BM-21s ("Grads") in civilian populated areas violated international humanitarian law's principle of distinction. These weapons cannot be targeted with sufficient precision to be accurate against military targets, and their broad area effect makes their use incompatible with the laws of war in areas where civilians or civilian objects (such as schools or hospitals) are located. The use of such weapons in populated areas is indiscriminate by nature and thus prohibited under international humanitarian law.

Georgian forces attacked vehicles in which many Ossetian civilians were trying to flee the conflict zone on August 8–10, which resulted in death and injuries. The cases Human Rights Watch describes in this report indicate that-in those cases at least-disproportionate force was used and precautions were not taken to avoid or minimize loss of civilian life.

Conduct of ground troops

During Georgian forces' ground offensive there were also attacks which, Human Rights Watch's investigation suggests, failed to respect the principle of proportionality: attacks such as when Georgian tanks targeted buildings in which Ossetian fighters may at times have been present, but where there were also many civilians sheltering in the basement. Several Ossetian civilians reported looting by Georgian ground forces but otherwise generally did not report other specific incidents of abusive treatment during the ground offensive by Georgian troops. Those detained by Georgian forces, however, reported they were ill-treated when taken into custody.

Violations by Russian Forces

Indiscriminate and disproportionate use of force

Russian forces attacked areas in undisputed Georgian territory and in South Ossetia with aerial, artillery, and tank fire strikes, some of which were indiscriminate, killing and injuring civilians. With regard to many aerial and artillery attacks Russian forces failed to observe their obligations to do everything feasible to verify that the objects to be attacked were military objectives (and not civilians or civilian objects) and to take all feasible precautions to minimize harm to civilians. In one case, Russian forces attacked medical personnel, a grave breach of the Geneva Conventions and a war crime.

As noted above, the mere fact of civilian casualties or destruction of civilian objects does not mean that a humanitarian law violation occurred. In each attack examined, Human Rights Watch sought to determine whether there was evidence of a legitimate military target in the attack area, and if so how that target was attacked.

Between August 8 and 12, Russian forces attacked Georgian military targets in Gori city and in ethnic Georgian villages in both South Ossetia and undisputed Georgian territory, often causing civilian casualties and damage to civilian objects such as houses or apartment blocks. The proximity of these military targets to civilian objects varied. In several cases, the military targets were within meters of civilians and civilian homes, and the attacks against them resulted in significant civilian casualties.

In other cases the apparent military targets were located as far as a kilometer away from civilian objects, and yet civilian casualties also resulted. In attacking any of these targets the Russian forces had an obligation to strictly observe the principle of proportionality, and to do everything feasible to assess whether the expected civilian damage from the attack would likely be excessive in relation to the direct military advantage anticipated. In many cases the attacks appear to have violated this proportionality principle. In yet other cases, Human Rights Watch investigated-but was not able to identify-any legitimate military targets in the immediate vicinity at the time of the attacks. The absence of a military target in the vicinity of an attack raises the possibility that Russian forces either failed in their obligation to do everything feasible to verify that the targets were military and not civilian, that they were reckless toward the presence of civilians in their target zone, or that Russian forces deliberately targeted civilian objects.

In several incidents involving military force against civilian vehicles, Russian forces may have intentionally targeted civilians. Deliberate attacks on civilians amount to war crimes.

Conduct of ground troops Several local residents told Human Rights Watch that many of the Russian servicemen who occupied undisputed Georgian territories behaved in a disciplined manner and in some cases even protected the civilian population from Ossetian forces, militia members, or looters. Nevertheless Russian forces played a role in the widespread looting of Georgian homes by Ossetian forces. Russian forces facilitated and participated in these war crimes, albeit in less prominent roles than South Ossetian forces, but we identified four cases in which Russian forces played an active and discernable role in looting.

Human Rights Watch also documented incidents in which Russian tanks fired at close range into civilian homes.

Russia's responsibility as occupying power

When Russian forces entered Georgia, including South Ossetia, which is de jure part of Georgia, they did so without the consent or agreement of Georgia. International humanitarian law on occupation therefore applied to Russia as it gained effective control over areas of Georgian territory. Russia failed overwhelmingly in its duty as an occupying power to ensure, as far as possible, public order and safety in areas under its effective control in South Ossetia. This allowed South Ossetian forces to engage in wanton and widescale pillage and burning of Georgian homes and to kill, beat, rape, and threaten civilians. Roadblocks set up by Russian forces on August 13 effectively stopped the looting and torching campaign by Ossetian forces, but the roadblocks were inexplicably removed after just a week.

Violations by South Ossetian Forces

In South Ossetia

Beginning just after the withdrawal of Georgian troops from South Ossetia, South Ossetian forces, including volunteer militias, embarked on a campaign of deliberate and systematic destruction of the Georgian government-administered villages in South Ossetia. This involved the widespread and systematic pillage and torching of houses, and beatings and threats against civilians. Starting August 10, after Russian ground forces had begun to fully occupy South Ossetia and were moving onward into undisputed Georgian territory, Ossetian forces followed closely behind them and entered the ethnic Georgian villages.

Upon entering these villages, Ossetian forces immediately began going into houses, searching for Georgian military personnel, looting property, and burning homes. They also physically attacked many of the remaining residents of these villages, and detained dozens of them. Human Rights Watch received uncorroborated reports of at least two extrajudicial killings of ethnic Georgians in South Ossetia that took place amidst the pillage. In most cases, Russian forces had moved through this set of Georgian villages by the time South Ossetian forces arrived. In other cases, Russian forces appeared to give cover to South Ossetian forces while they were committing these offenses.

By August 11 the attacks intensified and became widespread. Looting and torching of most of these villages continued intermittently through September, and in some through October and November.

Ossetian forces rounded up at least 159 ethnic Georgians (some of whom were abducted from undisputed Georgian territory), killing at least one and subjecting nearly all of them to inhuman and degrading treatment and conditions of detention. They also tortured at least four Georgian prisoners of war and executed at least three.

Human Rights Watch's observations on the ground and dozens of interviews conducted led us to conclude that the South Ossetian forces sought to ethnically cleanse this set of Georgian villages: that is, the destruction of the homes in these villages was deliberate, systematic, and carried out on the basis of the ethnic and imputed political affiliations of the residents of these villages, with the express purpose of forcing those who remained to leave and ensuring that no former residents would return.

In undisputed Georgian territory

Beginning with the Russian occupation of Georgia and through the end of September, Ossetian forces, often in the presence of Russian forces, conducted a campaign of deliberate violence against civilians, burning and looting their homes on a wide scale, and committing execution-style killings, rape, abductions, and countless beatings.

Crimes against humanity

In both locations South Ossetian forces, including volunteer militias, egregiously violated multiple obligations under humanitarian law. Murder, rape, acts of torture, inhuman or degrading treatment, and wanton destruction of homes and property are all strictly prohibited under both humanitarian law and serious violations of human rights law, and the perpetrators of such acts should be held criminally responsible for them. To the extent that any of these prohibited acts was committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack directed against any civilian population, they may be prosecuted as a crime against humanity. Where any of these acts, as well as acts such as imprisonment, unlawful detention of civilians, pillaging and comprehensive destruction of homes and property, were carried out with discriminatory intent against a particular group, in this case ethnic Georgians, they also constitute the crime of persecution, a crime against humanity, prosecutable under the statute of the International Criminal Court.

Use of Cluster Munitions

During the armed conflict both Georgian and Russian forces used cluster munitions, which are munitions that release dozens or hundreds of bomblets, or submunitions, and spread them over a large area. Because cluster munitions cannot be directed at specific fighters or weapons, civilian casualties are virtually guaranteed if cluster munitions are used in populated areas. For this reason, using cluster munitions in populated areas should be presumed to be indiscriminate attack, which is a violation of international humanitarian law. Cluster munitions also threaten civilians after conflict: Because many submunitions fail to explode on impact as designed, a cluster munitions strike often leaves a high number of hazardous unexploded submunitions-known as duds-that can easily be set off upon contact.

Human Rights Watch was not able to conduct adequate research to establish whether Georgia's use of cluster munitions was indiscriminate. Due to either malfunction or human error, Georgian cluster munitions landed in undisputed Georgian territory on days prior to the arrival of Russian forces there, killing at least one civilian and wounding two others. The report documents how at least three people were killed and six wounded by cluster duds that exploded upon contact in three villages in undisputed Georgian territory.

Georgia has acknowledged its use of clusters, and conducted a campaign following the armed conflict to warn civilians of the dangers posed by unexploded submunitions.

Russia has not acknowledged its own use of cluster munitions. Russian forces used cluster munitions in strikes against targets in populated areas in the Gori and Kareli districts just south of the South Ossetian administrative border, killing at least 12 civilians and injuring at least 46 at the time of attack. All of these strikes amounted to indiscriminate attacks.

The Russian and Georgian governments should join the 95 nations that have signed the Convention on Cluster Munitions, which imposes a comprehensive ban on the use of these weapons. Russia should make every effort to assist demining organizations with clearance and risk education in contaminated areas currently under effective Russian control, and Georgia should expand its cooperation with these organizations.

International Responses to the Conflict

Since the end of the conflict the European Union, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), and the Council of Europe have put in place mechanisms to monitor the human rights situation and promote security and stability near and in South Ossetia. Russia and Georgia should fully cooperate with these initiatives. The Russian government in particular should provide full, unimpeded access to South Ossetia to these intergovernmental organizations so that they may fully implement these initiatives.

At the end of 2008 Russia refused to approve budgetary support for the OSCE's presence in Georgia, claiming that the organization had to separate its work on Georgia's two breakaway regions-Abkhazia and South Ossetia-from work on other parts of Georgia. At this writing the OSCE was in the process of closing its offices in Georgia. Human Rights Watch urges the Russian government to reconsider its objections and to facilitate OSCE access to South Ossetia.

The United States government, a close ally of Georgia, should press the Georgian government to investigate and hold accountable violations of humanitarian law, and should prevail on the Georgian government to cooperate with various intergovernmental inquiries. The European Union and the United States, as participants in ongoing talks on security and returns of displaced persons, should urge Russia to uphold its responsibility to facilitate returns of all displaced persons to South Ossetia.

Methodology

A team of Human Rights Watch researchers conducted a number of research missions from August to November 2008 in South Ossetia and in undisputed parts of Georgia, and in August in North Ossetia (in the Russian Federation), to document violations of international humanitarian law and human rights law committed by all sides in the conflict.

Human Rights Watch researchers conducted three approximately one-week missions in South Ossetia beginning on August 10, and again in September and November. One of these missions was carried out jointly with Human Rights Centre Memorial, a Russian nongovernmental human rights organization.

Human Rights Watch researchers conducted research in undisputed parts of Georgia continuously from August 11 to 28, and again for one week in mid-September and one week in mid-October. Extensive research was conducted in the Gori and Kareli districts of undisputed Georgian territory while those districts were under Russian occupation. Human Rights Watch experts on armaments, including cluster munitions, participated in research missions in August and October. Human Rights Watch's Tbilisi-based researcher conducted follow up research after fact-finding missions.

Human Rights Watch researchers conducted over 460 in-depth interviews with victims and witnesses of abuses committed by all parties to the conflict. Interviewees included persons residing in towns and villages of South Ossetia and undisputed Georgian territory; persons displaced from South Ossetia and undisputed parts of Georgia living in displaced person shelters in various parts of Georgia; persons displaced from the conflict and temporarily staying in North Ossetia; persons formerly detained by Russian and Ossetian forces; persons formerly detained by Georgian forces; former prisoners of war detained by Georgian forces; former prisoners of war detained by Russian and Ossetian forces; Georgian soldiers participating in active combat in South Ossetia; and members of South Ossetian militia and other forces.

In the course of their research, Human Rights Watch staff visited the following places in South Ossetia: Tskhinvali, Khetagurovo, Dmenisi, Sarabuki, Gromi, Tbeti, Novyi Tbet, Gudzhabauri, Muguti, Ubiati, Batatykau, Kohat, Bikari, Zonkar, Zakori, Ahalgori, Kanchaveti, Znauri, Alkhasheni, Archneti, Sinaguri, Kekhvi, Kurta, Kvemo Achabeti, Zemo Achabeti, Tamarasheni, Eredvi, Disevi, Beloti, Satskheneti, Atsriskhevi, Avnevi, Nuli. In undisputed Georgian territory Human Rights Watch visited: Gori city, Karbi, Tortiza, Kheltubani, Tkviavi, Akhaldaba, Variani, Ruisi, Dzlevijvari, Pkhvenisi, Tedotsminda, Karaleti, Tirdznisi, Koshka, Ergneti, Karaleti, Knolevi, Avlevi Ptsa, Khashuri, and Tseronisi.

Interviews with victims and witnesses in South Ossetia were conducted in Russian by native Russian speakers. Interviews in Georgia with victims and witnesses were in some cases conducted in Russian by native or fluent Russian speakers; in some cases in Georgian by a native Georgian speaker; and in other cases in Georgian with the assistance of an interpreter translating from Georgian to English. The majority of interviews were conducted in private; a small proportion were conducted in groups. Before being interviewed, interviewees were told of the purpose of the interview, informed what kinds of issues would be covered, and asked whether they wanted to proceed. No incentives were offered or provided to persons interviewed. (More detail on the methodology used for particular aspects of the research is included in the relevant chapters below.)

We have indicated where the names of individuals interviewed by Human Rights Watch (and in some cases, other identifying information) were changed to protect their security.

As part of our research, we also sought to meet with government officials representing each party to the conflict. In Georgia we held meetings with the National Security Council, the Ministry of Defense, the Ministry of Interior, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Ministry of Justice, and the Office of the Prosecutor General. The Georgian government also provided written responses to Human Rights Watch letters of August 29 and November 12, 2008.

Human Rights Watch requests for meetings in Russia with the Ministry of Defense, the Ministry of Interior, the Ministry of Emergency Situations, and the Office of the President went unanswered. Human Rights Watch letters of October 13, 2008-sent repeatedly to the Ministry of Defense, the Ministry of Emergency Situations, and the Office of the President requesting answers to specific questions-also went unanswered. (See Appendix) The Office of the Prosecutor General replied on December 21, 2009 to our request for information by stating that the request had been forwarded to the Investigative Committee under the Procuracy of the Russian Federation and the General Prosecutor of the Republic of South Ossetia. (See Appendix).

In South Ossetia, we met with de facto authorities, including the deputy prosecutor general, the South Ossetia Committee for Print and Information, and the South Ossetia human rights ombudsman.

* * *

Our research endeavored to identify violations of international humanitarian law irrespective of which party to the conflict may have been responsible. Issues related to the causes and origins of the conflict, as well as responsibility for starting the conflict, are not within Human Rights Watch's mandate and therefore were not part of our research.

The issue of civilian casualties is of great concern to Human Rights Watch, particularly when these casualties are caused by violations of international humanitarian law. However, Human Rights Watch did not have the capacity or expertise to carry out research to determine a conclusive number of civilian casualties.

A note on geographical and family names

The names of towns and villages in South Ossetia differ in the Georgian and Ossetian languages. Most Georgian nomenclature ends in the letter "i," whereas Ossetian nomenclature does not. For example, Tskhinvali, the Georgian name for the capital of South Ossetia, is known as Tskhinval in Ossetian. The Alkhagori district is known by Ossetians by its Russian nomenclature, Leningori.

This report's use of the Georgian nomenclature has no political significance or implications.

In a number of Georgian villages numerous people who are not related have the same family name.

Part 1: Background

1.1 Background on South Ossetia

South Ossetia is located along Georgia's northern frontier in the Caucasus Mountains, bordering North Ossetia, a republic of the Russian Federation. The region is surrounded to the south, east, and west by undisputed Georgian territories. Prior to the August 2008 conflict, South Ossetia's population consisted of ethnic Ossetians and Georgians and numbered some 70,000 people, 20 to 30 percent of whom were ethnic Georgians.[2] South Osseti a's capital, Tskhinvali, had a population of about 30,000. A number of villages in South Ossetia were overwhelmingly populated by ethnic Georgians, principally in three valleys: Didi Liakhvi (directly north of Tskhinvali and including Kekhvi, Kurta, Zemo Achabeti, Kvemo Achabeti, and Tamarasheni);[3] Patara Liakhvi (northeast of Tskhinvali and including Eredvi, Vanati, Beloti, Prisi, Satskheneti, Atsriskhevi, Argvitsi, Berula, and Disevi); and Froni (west of Tskhinvali and including Avnevi, Nuli, and Tighva). A large part of the Akhalgori district was also overwhelmingly Georgian-populated.[4] With a handful of exceptions in the west of South Ossetia, villages inhabited mainly or exclusively by ethnic Georgians were administered by Tbilisi, while Tskhinvali and Ossetian-inhabited villages were under the administration of the de facto South Ossetian authorities.

1991-92 Conflict in South Ossetia

During the Soviet era, South Ossetia was an autonomous oblast, or region, of the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic. It sought greater autonomy from Tbilisi in the period before the breakup of the Soviet Union. In autumn 1990 South Ossetia proclaimed full sovereignty within the USSR and boycotted the election that brought the political party of Zviad Gamsakhurdia, a Georgian nationalist, to power in Georgia. Gamsakhurdia's government responded fiercely to those developments and abolished the autonomous oblast status of South Ossetia in December 1990,[5] leading to increased tensions and armed conflict in 1991-92. Direct military confrontation between South Ossetian separatists and Georgian police and paramilitaries started in January 1991, leading to a year of skirmishes and guerrilla warfare with sporadic Russian involvement overwhelmingly in support of the separatists. The conflict resulted in some 1,000 dead, 100 missing, extensive destruction of property and infrastructure, as well as thousands of displaced people, including ethnic Georgians from South Ossetia and ethnic Ossetians from other parts of Georgia.[6]

(Another conflict in Georgia was fought in the early 1990s in Abkhazia, a former Autonomous Republic of Soviet Georgia located in northwestern Georgia between the Black Sea and the Caucasus Mountains. The 1992-93 military confrontation there led to some 8,000 deaths, 18,000 wounded, and the forced displacement of over 200,000 ethnic Georgians.[7])

The first conflict in South Ossetia culminated in the region's de facto secession from Georgia in 1992. On June 24, 1992, in the Russian city of Sochi, Russian and Georgian leaders Boris Yeltsin and Eduard Shevardnadze signed an agreement that brought about a ceasefire.[8] The Sochi Agreement established the Joint Control Commission (JCC), a body for negotiations composed of Georgian, Russian, North Ossetian, and South Ossetian representatives, and the Joint Peacekeeping Forces (JPKFs), a trilateral peacekeeping force with Georgian, Russian, and Ossetian units.[9] These units operated under a joint command, the JPKF commander being nominated by the Russian Ministry of Defence and appointed by the JCC. Battalion commanders were directly appointed by each side. Although the JPKF were meant as a joint force, in reality they were three separate battalions, deployed in different locations andmore loyal to their respective sides than to the JPKF commander.

2003-06: New Leadership in Georgia, New Agenda for Recovering South Ossetia

The peacekeeping and conflict settlement process evolved slowly over the years, with lengthy periods of inactivity. For 12 years there was no military confrontation. After his election in January 2004, President Mikheil Saakashvili made the restoration of Georgia's territorial integrity one of his top priorities. Tbilisi's initial approach to recovering South Ossetia was to simultaneously launch a large-scale anti-smuggling operation, aimed at undermining the major source of income for the de facto South Ossetian leadership, as well as a humanitarian aid "offensive" in an attempt to win the loyalty of Ossetians.[10] The anti-smuggling operation was focused primarily on closing a wholesale market near Tskhinvali, a hub for goods smuggled from Russia that entered Georgia's internal markets without proper customs clearance.[11] Saakashvili's government also initiated economic and cultural projects, including an Ossetian-language television station, pensions, free fertilizer, and humanitarian aid.[12]

In the late 1990s the Russian government began proactively to offer to residents of South Ossetia and Abkhazia Russian citizenship and to facilitate their acquisition of Russian passports for foreign travel; by the end of 2007, according to the South Ossetian authorities, some 97 percent of residents of South Ossetia had obtained Russian passports.[13] As Russia imposed a visa regime with Georgia in 2000, Russian passports allowed Ossetians and Abkhaz to cross freely into Russia and entitled them to Russian pensions and other social benefits.[14]

2004 spike in tensions

As part of the anti-smuggling campaign, in May 2004 several Georgian Ministry of Interior units landed by helicopter in the three Gori district villages adjacent to the South Ossetian administrative border, and one Tbilisi-administered village inside South Ossetia. The units proceeded to set up roadblocks that restricted traffic from South Ossetia. This move led to renewed hostilities in the following months that resulted in dozens of casualties, but stopped short of warfare.[15] The parties of the JCC agreed on a new ceasefire in August 2004.

Following the August 2004 crisis, the security situation in South Ossetia remained tense, with frequent exchanges of fire between the sides that occasionally resulted in deaths, and increased the rate of crime.[16] In another bid to alter the status quo peacefully, in late 2006 the Georgian government began strongly supporting an alternative South Ossetian administration led by Dmitry Sanakoev.[17] Following parallel presidential elections in November 2006, two competing governments existed in South Ossetia: the secessionist de facto government headed by Eduard Kokoity in Tskhinvali and a pro-Tbilisi government headed by Sanakoev, based in Kurta, an ethnic Georgian village five kilometers from Tskhinvali.[18] The Sanakoev administration maintained authority over the ethnic Georgian villages and a large part of the Akhalgori district of South Ossetia, while Tskhinvali administered the rest of South Ossetia.

Instability and occasional skirmishes persisted,[19] and negotiations between Tbilisi and Tskhinvali within the JCC framework stalled. Georgia pushed for a change in the JCC format, as it saw the JCC as a "three against one" arrangement: Tbilisi called for limiting Russia's role and insisted on participation of the European Union, United States, and Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) in the talks.[20] Tskhinvali opposed any format change and instead pushed for a formal agreement on the non-use of force, with strong Russian support.[21] Russia, which has considered itself a guarantor of stability in the region, since August 2004 also began to emphasize an obligation to protect the large number of Ossetians to whom it had given Russian passports.[22]

2006-08: Tensions Rise between Russia and Georgia

An increasingly strained relationship between Georgia and Russia compounded rising tensions between Tskhinvali and Tbilisi. The relationship between Moscow and Tbilisi was completely severed in September 2006 when Russia, in response to Georgia's detention of four alleged Russian spies, halted all air, land, and sea traffic with the country, and began a widespread crackdown on ethnic Georgians. During this time, Russia expelled more than 2,300 Georgians from Russia.[23]

By April 2008 communication between Russia and Georgia was being restored, but Russia, angered by Western countries' recognition of Kosovo's independence in February 2008 and by Georgia's continued efforts to join NATO, moved to deepen its cooperation with the breakaway administrations in Abkhazia and South Ossetia.[24] Georgia responded by blocking further negotiations over Russia's accession to the World Trade Organization.[25] Georgian use of unmanned reconnaissance drones in the airspace above the breakaway republics and the downing of one such drone by a Russian airplane on April 20 strained the relationship further.[26]

The Lead-up to the August 2008 War

In the months preceding the August war, tensions in South Ossetia steadily escalated as Georgian and South Ossetian forces engaged in violent attacks and mutual recriminations. In July Georgian forces hit nine residential homes in Tskhinvali and a nearby village with artillery fire, resulting in two dead and 11 wounded. Georgia said it had been forced to return fire after an attack. In response, South Ossetia announced a general mobilization, but halted it within hours when Georgian forces ceased firing.[27] A week later, Russia confirmed Georgian allegations that four Russian air force jets had conducted overflights over Tskhinvali in violation of Georgia's airspace, a move that caused Georgia to recall its ambassador to Russia. Russia stated that the overflights had been necessary to "cool hot heads in Tbilisi" and prevent attempts to settle the dispute over South Ossetia through military means.[28]

Military exercises conducted by both sides also contributed to rising tensions. On July 15, the Fourth Infantry Brigade of the Georgian Army conducted an exercise near Tbilisi with US forces, called "Immediate Response 2008."[29] On the same day, the Russian military launched "Caucasus 2008," a military exercise involving 8,000 troops not far from the Roki tunnel connecting Russia and South Ossetia. While the main stated goal of the exercise was to evaluate capacity for joint operations in connection with the terrorist threat in southern Russia, the Russian Ministry of Defense announced that, in connection with the deteriorating situation in Georgia, it would also address issues of peace enforcement in conflict zones.[30] Upon completing its military exercise, Georgia concentrated its entire artillery brigade in the city of Gori, just 30 kilometers from Tskhinvali.[31]

Toward the end of July, violent skirmishes between Georgian and South Ossetian forces became more frequent. On July 29, Georgian and South Ossetian each accused the other of firing on the other side. On August 1, several Georgian police officers were injured in a bomb attack in South Ossetia.[32] Later that day snipers shot and killed six South Ossetian police officers. The next morning automatic weapon and mortar fire resumed between the southwest side of Tskhinvali and the Georgian settlement of Zemo Nikozi.[33] The renewed violence prompted several hundred civilians, mostly women and children, to evacuate to Russia.[34]

Over the next few days, the sides exchanged fire, but apparently without casualties. Tbilisi continued to amass forces close to the South Ossetia administrative border. According to some accounts, by the morning of August 7 there were 12,000 Georgian troops and 75 tanks and armored personnel carriers gathered not far from the South Ossetian border.[35]

Fighting intensified toward the evening on August 6 and throughout August 7. Georgian authorities claim that its forces opened fire in response to the Ossetian side firing mortars on villages inhabited by ethnic Georgians. The de facto South Ossetian authorities claim that Georgian forces were trying to capture a strategic hill overlooking a road connecting Tskhinvali and several Ossetian villages.[36] On the evening on August 7 President Saakashvili announced a unilateral ceasefire.[37] Hours later, however, he rescinded the ceasefire, citing continued Ossetian shelling of Georgian villages.[38]

The Fighting and Immediate Political Aftermath

Late in the evening of August 7, Georgian forces initiated massive shelling of Tskhinvali and surrounding villages in an attack that is widely considered the start of the war. The Georgian government says its forces launched the attack to suppress firing positions from which South Ossetian militia had attacked Georgian peacekeeping forces and Georgian villages. Georgian authorities also claim that they had received information that Russian forces were moving south through the Roki tunnel in the early morning of August 7, and that they launched the attack to prevent a full-scale Russian invasion of their country.[39] Russian authorities, however, contend that the movements at the Roki tunnel were part of normal rotation of Russian peacekeeping troops stationed in South Ossetia,[40] and that the Georgian attack on Tskhinvali was an act of aggression against Russian peacekeeping forces and the civilian population.[41]

Throughout the night between August 7 and 8, Georgian forces shelled Tskhinvali, using, among other weapons, BM-21 "Grad," a multiple rocket launcher system capable of firing 40 rockets in 20 seconds. Attacks intensified overnight and into the morning of August 8 as Georgian ground forces moved toward Tskhinvali. Around 8 a.m. Georgian ground forces entered Tskhinvali and street fighting erupted between Georgian forces and groups of South Ossetian forces, mainly militia, who tried to stop the Georgian offensive. In the course of the day, several villages in South Ossetia fell under Georgian forces' control.[42]

During the day on August 8, regular Russian ground forces moved through the Roki tunnel toward Tskhinvali while Russian artillery and aircraft subjected Georgian ground forces in Tskhinvali and other places to heavy shelling and bombardment. Georgian forces bombed and shelled Russian military targets as Russian forces moved toward Tskhinvali.[43] By the evening of August 8, Russian authorities declared that units of the 58th Army were deployed in the outskirts of Tskhinvali and that their artillery and combat tanks had suppressed Georgian firing positions in Tskhinvali.[44] At the same time, Georgia's President Saakashvili declared that Georgian forces completely controlled Tskhinvali and other locations.[45]

Russian aircraft also attacked several targets in undisputed Georgian territory beginning on August 8. Starting from around 9:30 a.m. on August 8, Russian aircraft attacked targets in several villages in the Gori district, Gori city, and, in the afternoon, Georgian military airports near Tbilisi.[46]

Over the next two days, Russian forces continued to move into South Ossetia, eventually numbering by some estimates 10,000 troops with significant artillery force.[47] Georgian armed forces persisted with attempts to take Tskhinvali, twice being forced back by heavy Russian fire and fire from South Ossetian forces, including volunteer militias.Early in the morning of August 10, Georgian Defense Minister Davit Kezerashvili ordered his troops to withdraw from Tskhinvali and fall back to Gori city.[48]

Even though the Russian Ministry of Defense announced that Russian forces had ended all combat operations at 3 p.m. on August 12 and that all units had received an order to remain in their positions,[49] Russian armed forces crossed the South Ossetian administrative border on August 12 and moved toward Gori city.[50] The exact time when Russian forces occupied Gori city is disputed. The Russian authorities admitted that they were removing military hardware and ammunition from a depot in the vicinity of Gori on August 13,[51] but denied that there were any tanks in the city itself.[52] Russian tanks blocked roads into Gori city on August 14.[53] By August 15, Russian troops had advanced past Gori city as far as the village of Igoeti, 45 kilometers west of Tbilisi.[54] In a separate operation from the west, moving through Abkhazia, Russian forces occupied the strategically important cities of Poti, Zugdidi, and Senaki in western Georgia, establishing checkpoints and roadblocks there.

By August 16, President Saakashvili and his Russian counterpart President Dmitry Medvedev had signed a six-point ceasefire agreement brokered by French President Nikolas Sarkozy in his capacity as leading the French European Union presidency. The ceasefire agreement called for cessation of hostilities and the withdrawal of all forces to their pre-August 6 positions, while allowing Russian peacekeeping forces to implement additional security measures until an international monitoring mechanism would be in place.[55]

Beginning August 15, the Russian authorities started a gradual pull-back of Russian forces from undisputed Georgian territory, with withdrawal accelerating by August 20. Russian troops left Gori city on August 22, but established military checkpoints in the villages of Variani and Karaleti, just a few kilometers north of the city. This created what the Russian authorities called a security zone and what commonly became known as a "buffer zone," approximately 20 kilometers wide and controlled by Russian forces. Although civilians were allowed to enter and exit the zone, subject to document and vehicle inspections, Russian forces denied access to Georgian police. Russian troops finally withdrew to South Ossetia in early October, although Russian troops still occupy a village on the border.[56]

As Russian forces withdrew, the EU deployed a mission under the European Security and Defense Policy, and the OSCE deployed military observers in undisputed Georgian territory adjacent to the South Ossetian border. Both sets of observers have been denied access to South Ossetia, however. On December 23 Russia refused to approve budgetary support for the OSCE's presence in Georgia, requesting separate OSCE missions in Georgia's breakaway regons. At this writing the OSCE was in the process of closing its offices in Georgia, including monitoring activities in the undisputed Georgian territories adjacent to South Ossetia.

On August 26, the Russian authorities recognized the independence of Abkhazia and South Ossetia[57] in a move widely criticized by the EU, the Council of Europe, NATO, and the OSCE (Russia's move has gone almost completely unmatched internationally-the only country to have followed suit in recognizing Abkhazia and South Ossetia as independent states is Nicaragua). Moscow says it will keep a total of 7,600 troops in Abkhazia and South Ossetia.[58]

The EU, OSCE, and United Nations have co-hosted a series of talks between Georgian, Russian, and de facto South Ossetian authorities, focusing on stability and displaced persons. The first round of talks, held in mid-October, stalled over the issue of the status of the delegations from South Ossetia and Abkhazia. One of the two subsequent rounds, held in December, resulted in an oral agreement between the Russian and Georgian sides to prevent and investigate security incidents that have plagued the ceasefire.[59]

1.2 International Legal Framework

This chapter addresses the general international legal issues related to the August 2008 conflict in Georgia. This includes international humanitarian law relating to the conduct of hostilities, humane treatment, and occupation; international human rights law; and international law concerning displaced persons and the right to return. Discussion of specific violations of International humanitarian law and human rights law are found within the relevant chapters below.

International Humanitarian Law Governing Hostilities

The conduct of the armed conflict in Georgia and South Ossetia is primarily governed by international humanitarian law, also known as the laws of war. International humanitarian law imposes upon parties to a conflict legal obligations to reduce unnecessary suffering and protect civilians and other non-combatants, or those hors de combat, such as prisoners. It does not regulate whether states and armed groups can engage in armed conflict, but rather how they engage in hostilities.[60] All armed forces involved in the hostilities, including non-state armed groups, must abide by international humanitarian law.[61] Individuals who violate humanitarian law with criminal intent may be prosecuted in domestic or international courts for war crimes.[62]

Under international humanitarian law, the hostilities that occurred between Russia and Georgia constitute an international armed conflict-a conflict between two states. The law applicable to international armed conflict includes treaty law, primarily the four Geneva Conventions of 1949 and its First Additional Protocol of 1977-Protocol I-and the Hague Regulations of 1907 regulating the means and methods of warfare, as well as the rules of customary international humanitarian law.[63] Both Georgia and Russia are parties to the 1949 Geneva Conventions and Protocol I.[64]

Since South Ossetia is recognized as part of Georgia, fighting between the non-state South Ossetian forces and militia and Georgian forces falls under the laws applicable to non-international (internal) armed conflict.[65] Internal armed conflicts are governed by article 3 common to the four Geneva Conventions of 1949 (Common Article 3), the Second Additional Protocol of 1977 to the Geneva Conventions (Protocol II, to which Georgia is a party), as well as customary international humanitarian law.[66]

Customary humanitarian law as it relates to the fundamental principles concerning conduct of hostilities is now recognized as largely the same whether it is applied to an international or a non-international armed conflict.

International human rights law also continues to be applicable during armed conflicts.[67] Georgia and Russia are both parties to the major international and regional human rights treaties, including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR).[68] These treaties guarantee all individuals their fundamental rights, many of which correspond to the protections afforded under international humanitarian law including the prohibition on torture, inhuman and degrading treatment, nondiscrimination, and the right to a fair trial for those charged with criminal offenses.[69]

Basic Principles of International Humanitarian Law

The fundamental tenets of international humanitarian law are "civilian immunity" and "distinction,"[70] While humanitarian law recognizes that some civilian casualties are inevitable, it imposes a duty on warring parties at all times to distinguish between combatants and civilians, and to target only combatants and other military objectives.[71]Civilians lose their immunity from attack when and only for such time that they are directly participating in hostilities.[72]

Civilian objects, which are defined as anything not considered a military objective, are also protected.[73]Direct attacks against civilian objects, such as homes, businesses, places of worship, hospitals, schools, and cultural monuments are prohibited -unless the objects are being used for military purposes.[74]

Humanitarian law further prohibits indiscriminate attacks. Indiscriminate attacks are of a nature to strike military objectives and civilians or civilian objects without distinction. Examples of indiscriminate attacks are those that are not directed at a specific military objective, or that use weapons that cannot be directed at a specific military objective or that use weapons that cannot be limited as required by humanitarian law. Prohibited indiscriminate attacks include area bombardment, which are attacks by artillery or other means that treat as a single military objective a number of clearly separated and distinct military objectives located in an area containing a concentration of civilians and civilian objects.[75]

Also prohibited are attacks that violate the principle of proportionality. Disproportionate attacks are those that are expected to cause incidental loss of civilian life or damage to civilian objects that would be excessive in relation to the concrete and direct military advantage anticipated from the attack.[76]

Humanitarian law requires that the parties to a conflict take constant care during military operations to spare the civilian population and "take all feasible precautions" to avoid or minimize the incidental loss of civilian life and damage to civilian objects.[77]These precautions include doing everything feasible to verify that the objects of attack are military objectives and not civilians or civilian objects,[78] and giving "effective advance warning" of attacks when circumstances permit.[79]

International humanitarian law does not prohibit fighting in urban areas, although the presence of civilians places greater obligations on warring parties to take steps to minimize harm to civilians. Forces deployed in populated areas must avoid locating military objectives near densely populated areas,[80]and endeavor to remove civilians from the vicinity of military objectives.[81]Belligerents are prohibited from using civilians to shield military objectives or operations from attack-"shielding" refers to purposefully using the presence of civilians with the intent to render military forces or areas immune from attack.[82]At the same time, the attacking party is not relieved from the obligation to take into account the risk to civilians on the grounds that it considers the defending party responsible for having located legitimate military targets within or near populated areas.

With respect to persons within the control of a belligerent party's forces, humanitarian law requires the humane treatment of all civilians and captured combatants. It prohibits violence to life and person, particularly murder, mutilation, cruel treatment, and torture.[83]It is also unlawful to commit rape and other sexual violence; to carry our targeted killings of civilians, including government officials and police, who are not participating in the armed conflict; and to engage in pillage and looting.[84]

Captured members of the Russian and Georgian armed forces are considered prisoners-of-war and fall under the extensive provisions of the Third Geneva Convention. For captured members of South Ossetian militias to qualify as prisoners of war would require that militia members had a regular chain of command; wore distinct insignia or uniforms; carried arms openly; and conducted operations in accordance with the laws of war.[85] As discussed below, the South Ossetian militias did not meet all four conditions and so must be detained, along with other civilians who are taken into custody, in accordance with the Fourth Geneva Convention on the protection of civilian persons.

Individual Criminal Responsibility

With respect to individual responsibility, serious violations of international humanitarian law, including deliberate, indiscriminate, and disproportionate attacks harming civilians, when committed with criminal intent, are considered war crimes.[86] An act is carried out with criminal intent if it is done deliberately or recklessly. For example, a commander who knew that civilians remained in an area but still indiscriminately bombarded that area would be criminally responsible for ordering an unlawful attack.

Individuals may also be held criminally liable for attempting to commit a war crime, as well as assisting in, facilitating, aiding or abetting a war crime. Responsibility may also fall on persons planning or instigating the commission of a war crime.[87]

Commanders and civilian leaders may be prosecuted for war crimes as a matter of command responsibility when they knew or should have known about the commission of war crimes or serious violations of human rights and took insufficient measures to prevent them or punish those responsible.[88]

States have an obligation under the Geneva Conventions and customary humanitarian law to investigate alleged war crimes committed by their nationals and members of their armed forces, or which were committed on territory that they control, and appropriately prosecute.[89]

Position of Peacekeepers under International Humanitarian Law

The Sochi agreement of 1992 established the Joint Peacekeeping Forces in South Ossetia (see Chapter 1.1).[90]

Under international humanitarian law, as long as peacekeepers remain neutral and do not participate in hostilities they are to be treated as civilians who enjoy protection from attacks.[91] While peacekeepers may on occasion be required to resort to use of force, such force must be strictly limited to actions that are necessary for self defense or defense of any civilian objects that they have a mandate under the peacekeeping agreement to protect. Force used in this way must be strictly proportionate to that goal.

Attacks directed against peacekeepers who are not participating in hostilities would be a serious violation of international humanitarian law and a war crime.

If peacekeepers act in a manner that is not neutral, for example by facilitating combat forces from one side, or engaging in hostile acts of firing, they lose the protection afforded them as civilians and may lawfully be subject to attack. The attacks, however, must also comply with the requirements of international humanitarian law regarding means and methods of warfare and the treatment of enemy combatants. Peacekeepers who use their protected status to carry out attacks are acting perfidiously, which is a serious violation of international humanitarian law.

During the conflict peacekeeping posts manned by Russian and/or Ossetian forces were targeted and Human Rights Watch witnessed the extensive damage caused to the peacekeepers' posts by Georgian attacks.[92] Both Russia and Georgia have made serious allegations with respect to attacks on or by peacekeeping forces, none of which Human Rights Watch was able to corroborate or refute. Georgian authorities claimed that South Ossetian forces fired artillery from peacekeeping posts, rendering them a legitimate target. Russian officials have claimed that Georgian troops deliberately and brutally killed members of peacekeeping troops, which would be a war crime whether the peacekeepers were entitled to civilian status or had participated in hostilities.[93]

Law on Occupation and Effective Control

Under international humanitarian law territory is considered "occupied" when it is under the control or authority of foreign armed forces, whether partially or entirely, without the consent of the domestic government. This is a factual determination, and the reasons or motives that lead to the occupation or are the basis for continued occupation are irrelevant. Even should the foreign armed forces meet no armed resistance and there is no fighting, once territory comes under their effective control the laws on occupation become applicable.[94]

International humanitarian law on occupation applies to Russia as an occupying power wherever Russian forces exercised effective control over an area of Georgian territory, including in South Ossetia or Abkhazia, without the consent or agreement of the Georgian government.[95] Russia also assumed the role of an occupying power in the Kareli and Gori districts of undisputed Georgian territory until the Russian withdrawal from these areas on October 10, 2008, because Russian presence prevented the Georgian authorities' full and free exercise of sovereignty in these regions.

Occupying powers are responsible for security and well-being of protected persons-those who find themselves in the hands of a party to the conflict or occupying power of which they are not a national.

Once an occupying power has assumed authority over a territory, it is obliged to restore and maintain, as far as possible, public order and safety.[96] Ensuring local security includes protecting individuals from reprisals and revenge attacks.Military commanders on the spot must take all measures in their power to prevent serious public order violations affecting the local population.[97] In practice this may mean that occupying forces should be deployed to secure public order until the time police personnel, whether local or international, can be mobilized for such responsibilities. An occupying power may take such measures of control and security as may be necessary as a result of the war.[98]

Under the Fourth Geneva Convention, the occupying power must also respect the fundamental human rights of the territory's inhabitants and ensure sufficient hygiene and public health standards, as well as the provision of food and medical care to the population under occupation.[99] Collective punishment and reprisals are prohibited.[100] Personnel of the International Red Cross/Red Crescent Movement must be allowed to carry out their humanitarian activities.[101] Everyone shall be treated with the same consideration by the occupying power without any adverse distinction based, in particular, on race, religion, or political opinion.[102] A party has a duty to protect property in areas that its forces exercise control over or occupy. Private property may not be confiscated.[103] Pillage is prohibited, and the destruction of any real or personal property is only permitted where it is rendered absolutely necessary by military operations.[104]

The Fourth Geneva Convention requires an occupying power to investigate "grave breaches" of the convention.[105] Customary international law further obliges states to investigate and prosecute serious violations of international humanitarian law, including launching deliberate attacks against civilians, and attacks causing indiscriminate or disproportionate civilian loss.

Under international law, the law of occupation is no longer in effect when the hostile armed forces cease to control the occupied territory, either because of a voluntary or forced withdrawal, or as the result of a peace treaty or other agreement. The law of occupation also will no longer be in effect upon agreement between states that leaves the occupying government present or in control of the territory, but no longer as a belligerent force.[106] At this writing, Russia remains an occupying power in South Ossetia.

Right to Return

As this report documents, as many as 20,000 ethnic Georgians displaced from their homes in South Ossetia by the fighting are currently not able to return to their homes. International law provides various protections to persons displaced from their homes, including the right to return.[107]

People who flee their homes as a result of war are entitled to return to their home areas and property, a right known as the "right to return." The right to return to one's former place of residence is related to the right to return to one's home country, which is expressly recognized in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and international human rights conventions.[108] The right to return to one's place of origin within one's country, or at least the obligation of states not to impede the return of people to their places of origin, is implied. For example, article 12 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights recognizes the right to choose freely one's own place of residence, which incorporates the right to return to one's home area.[109] In some cases, the right to return to one's former place of residence is also supported by the right to family reunification and to protection for the family.

Of both direct and indirect relevance to the displacement of ethnic Georgians is article 49 of Geneva Convention IV, which maintains that civilians who have been evacuated during an occupation "shall be transferred back to their homes as soon as the hostilities in the area in question have ceased." This provision is directly relevant to persons evacuated as a result of international armed conflict; it is indirectly relevant to persons displaced as a result of internal armed conflict insofar as it reflects the principle that parties responsible for breaches of international humanitarian law (in those cases where evacuation or forced displacement did not occur for imperative military reasons or for the safety of the affected population) are responsible for redressing such violations.

Recognizing these various rights, the UN Sub-Commission on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights has reaffirmed "the right of all refugees ... and internally displaced persons to return to their homes and places of habitual residence in their country and/or place of origin, should they so wish."[110] Numerous resolutions of the UN General Assembly and of the Security Council as well as several international peace agreements also recognize the right to return to one's home or property.[111]

In reference to previous displacement of civilians in Georgia, the UN Security Council passed Resolution 876 on October 19, 1993, in response to the situation in Abkhazia, which "affirmed the right of refugees and displaced persons to return to their homes."[112]

The UN Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement, which reflect existing international human rights and humanitarian law, restate and clarify the rights of displaced persons.[113] This includes the rights to freedom of movement and to choose their place of residence,[114] as well as the responsibility of competent authorities to establish the conditions and provide the means for internally displaced persons to return voluntarily to their homes or places of habitual residence or to resettle voluntarily in another part of the country.[115] The Guiding Principles also set out the prohibition on arbitrary deprivation of property through pillage, direct or indiscriminate attacks or other acts of violence, using internally displaced persons as shield for military operations or objectives, as well as making them object of reprisal.[116] The property of displaced persons should not be destroyed or appropriated as a form of collective punishment. The Guiding Principles also clarify the obligation of the authorities to protect the property of internally displaced persons from such acts as well as from arbitrary and illegal appropriation, occupation or use,[117] to assist displaced persons with recovery, to the extent possible, of their lost properties and possessions or to ensure compensation or other just reparation.[118]

Part 2: Violations by Georgian Forces

2.1 Overview

Human Rights Watch's investigation concluded that Georgian forces committed violations of the laws of war during their assault on South Ossetia. Our research shows that during the shelling of Tskhinvali and neighboring villages and the ground offensive that followed, Georgian forces frequently failed to abide by the obligation to distinguish between military targets that can be legitimately attacked, and civilians, who may not be targeted for attack. This was compounded by Georgia's failure to take all feasible measures to avoid or minimize civilian casualties. While we found no evidence that Georgian forces sought to deliberately target civilians, Human Rights Watch research concludes that Georgian forces demonstrated disregard for the protection of civilians during the shelling campaign, causing large-scale damage to civilian objects and property, and civilian casualties.

In the course of three missions to South Ossetia in August, September, and November 2008, Human Rights Watch interviewed more than 150 witnesses and survivors of the attacks on Tskhinvali and the ethnic Ossetian villages of Khetagurovo, Dmenisi, Sarabuki, Satikari, Gromi, Tbeti, Novyi Tbeti, Nizhnii Gudjabauri, Muguti, Monasteri, Batatykau, Kohat, Bikar, Tsinagari and Tsairi. Human Rights Watch researchers also examined the majority of sites where attacks took place, and gathered information from public officials, hospital personnel, and public activists.

The mere fact of civilian casualties or destruction of civilian objects does not mean that a violation of international humanitarian law occurred. Where civilian loss or damage occurred, what was important to seek to determine was whether there was evidence of a legitimate military target in the attack area, and how that target was attacked. In many cases Human Rights Watch researchers found no evidence of military objectives in the area under attack; other attacks did strike legitimate military targets, causing combatant and, in some cases, collateral civilian casualties.

In a number of cases, moreover, there were no direct witnesses and no reliable information regarding the circumstances of the attack. Also, since Georgian and Russian forces use some identical Soviet-era weapons systems including main battle tanks, Grad multiple-launch rockets, BMP infantry fighting vehicles, and tube artillery, Human Rights Watch could not always conclusively attribute specific battle damage to a particular belligerent, especially for the attacks that happened on and after the evening hours of August 8 when both Russian and Georgian troops were present in Tskhinvali. Human Rights Watch did not include such incidents in this report.

Yet many of the attacks on South Ossetia during the brief conflict can be clearly attributed to Georgian forces-based on witness accounts, the direction of the attack, and the timing of the damage in light of the advance of Georgian forces. Human Rights Watch has concluded that a number of these attacks were indiscriminate.

The massive shelling of Tskhinvali was indiscriminate because, as will be described below, at the very least the Georgian military effectively treated a number of clearly separated and distinct military objectives as a single military objective in an area that contained a concentration of civilians and civilian objects.

In some of the attacks investigated by Human Rights Watch, evidence suggests that the Georgian forces targeted lawful military objectives (that is, objects or persons making effective contribution to the military action) but the attacks may have been disproportionate, because they could have been expected to cause loss of civilian life or destruction of civilian property that was excessive compared to the anticipated military gain. In others, Georgian forces carried out a number of artillery attacks in which they failed to take all feasible precautions to minimize the likely extent of loss or injury to civilians.[119]

Georgia's use of multiple rocket launching systems, such as BM-21s ("Grads") in civilian populated areas violated international humanitarian law's principle of distinction. These weapons cannot be targeted with sufficient precision to be accurate against military targets, and their broad area effect makes their use incompatible with the laws of war in areas where civilians or civilian objects (such as schools or hospitals) are located. The use of such weapons in populated areas is indiscriminate by nature and thus prohibited under international humanitarian law.

Several Ossetian civilians reported looting by Georgian ground forces but otherwise generally did not complain of other abusive treatment during the ground offensive by Georgian troops.[120] Those detained by Georgian forces, however, reported they were ill-treated when taken into custody (see Chapter 2.8).

2.2 Indiscriminate Shelling of Tskhinvali and Outlying Villages

On the night of August 7-8, Georgian forces subjected the city of Tskhinvali and several nearby Ossetian villages, including Nizhnii Gudjabauri and Khetagurovo, to heavy shelling. That night other villages were also shelled, though less heavily, including Tbeti, Novyi Tbeti, Sarabuki, Dmenisi, and Muguti. Tskhinvali was heavily shelled during daytime hours on August 8. Shelling resumed at a smaller scale on August 9, when Georgian forces were targeting Russian troops who by then had moved into Tskhinvali and other areas of South Ossetia.

Based on numerous interviews with survivors and witnesses, and on an examination of the scene of the attacks, Human Rights Watch concluded that Georgian forces used Grad rockets, self-propelled artillery, mortars, and Howitzer cannons.

Tskhinvali

In Tskhinvali, the most affected areas were the city's south, southeast, southwest, and central parts. Georgian authorities later claimed that their military was targeting mostly administrative buildings in these areas.[121] The shells hit and often caused significant damage to multiple civilian objects, including the university, several schools and nursery schools, stores, and numerous apartment buildings and private houses. Such objects are presumed to be civilian objects and as such are protected from targeting under international law; but as described below, at least some of these buildings were used as defense positions or other posts by South Ossetian forces (including volunteer militias), which rendered them legitimate military targets.[122]

Human Rights Watch examined damage caused by shelling, including by Grad rockets, and interviewed witnesses from houses and apartment buildings located on numerous streets in different parts of the city.[123]

Grad rocket attacks on Tskhinvali and outlying villages

One of the civilian objects hit by the Grad rockets in Tskhinvali was the South Ossetian Central Republican Hospital (Tskhinvali hospital)-the only medical facility in the city that was assisting the wounded, both civilians and combatants, in the first days of the fighting.

One of the hospital's doctors told Human Rights Watch that the hospital came under fire for 18 hours, and that hospital staff had to take all of the wounded into the hospital basement because of this. Human Rights Watch documented the damage caused to the hospital building by a rocket believed to have been fired from a Grad multiple rocket launcher: the rocket had severely damaged treatment rooms on the second and third floors. Aivar Bestaev, the chief of the surgery department in the hospital, told Human Rights Watch,