When George Osborne visited China last month, he spoke gushingly about the huge opportunities for British businesses there. “Part of my job here,” he said, “is to help explain to the British people what’s going in China and how exciting it is.”

If he had been prepared to meet them, activists from China could have told Osborne a thing or two about what’s really happening in China today.

In the three years since President Xi Jinping assumed the presidency, there has been an alarming deterioration in human rights across the country. Between July and September this year, almost 300 human rights lawyers and activists were briefly detained and interrogated. Of these, about 20 remain in custody, most in secret locations without access to lawyers or family. Scores of others have been arrested and detained over recent years, and many have been tortured in detention.

The charges against activists and government critics are invariably preposterous – for example, when they are accused of “inciting subversion” for simply advocating political reform – and the legal processes behind these convictions are fundamentally flawed. Some of those imprisoned by the Chinese state have achieved international prominence, like the remarkable Liu Xiaobo, the Chinese literary critic, writer, professor, human rights activist and Nobel laureate who advocates peaceful political reform, and who is serving a monstrous 11-year jail sentence for doing so. But there are many others who face comparable or worse repression, beyond the reach of international media and political concern.

Xi has extended his iron grip on the internet, too. His government has shut down or restricted access to Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) which many people use to access content blocked to users inside the country. In July, the government published a draft cyber security law that will require domestic and foreign internet firms to practice censorship and aid government surveillance. And in a truly Orwellian move, the Chinese state will station police in major internet companies to monitor content and prevent the “spreading of rumours” online.

While the Chinese government says it’s committed to gender equality, it represses women activists who try to raise awareness about sexual harassment. Women’s reproductive rights are also curtailed under China’s abusive family planning regulations, with state authorities imposing sanctions, fines and abhorrent measures such as forced abortion.

Xi’s government continues to restrict religious freedom, with religious worship only allowed in officially approved mosques, churches, temples and monasteries, and religious appointments and publications all subject to government review. It also classifies many religious groups outside its control, such as the Falun Gong, as “evil cults”, with membership alone leading to criminal and extra-legal punishments.

Under Xi, China has pursued odious and discriminatory policies against its ethnic Uigher population. Although Osborne visited Xinjiang, home to many Uighers, on the anniversary of the trial and sentencing of the moderate Uigher scholar Ilham Tohti, he made no public comment on his case. And in Tibet, arbitrary detention, enforced disappearances and torture in detention remain widespread.

This is the reality of today’s China. There are many ways to describe this situation, but “exciting” is not one of them.

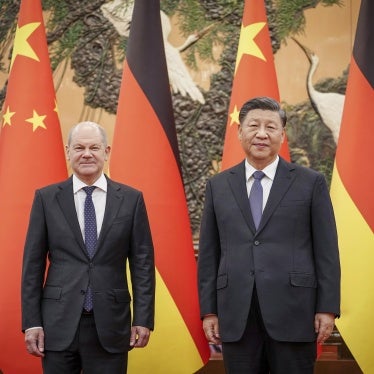

David Cameron has previously raised human rights issues with the Chinese leadership and during Xi’s state visit he should rediscover the moral courage to do so again. Public comments are sometimes dismissed as megaphone diplomacy, but they are nothing of the kind. Clear public statements of concern show solidarity with the victims of Chinese government repression, and often provide them with some degree of protection from the very worst abuses. That is what China’s human rights activists consistently tell us.

But standing up for human rights in China and urging far-reaching reform is also in our interests. Repression, pervasive corruption, impunity for abuses, a flawed judicial system – these are grave threats to China’s stability and its economy too. And that matters to all of us.