The referendum vote in June to leave the European Union sent political shockwaves through the country, creating uncertainty about future constitutional arrangements and the residence status of the more than 3 million citizens from other EU states in the UK.

The Brexit vote was preceded by the murder of MP Jo Cox, who had campaigned vigorously on behalf of asylum seekers and for the UK to remain in the UK. Following the vote there was a marked increase in xenophobic and racist hate crimes, including assault and arson attacks, with EU citizens from eastern Europe a particular target, according to data issued by the police. Poland sent police officers in September to an English town after a Polish man was beaten to death in a possible hate crime.

In an August review of the UK, the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination expressed concern at the “divisive, anti-immigrant and xenophobic rhetoric” employed during the Brexit campaign and the hate crimes that followed it, and called on public officials to formally reject such speech.

The government of Prime Minister Theresa May, elected leader by the Conservative Party in July, renewed its pledge to replace the UK’s domestic human rights legislation with a bill of rights, but took no discernable action towards that end. After the Brexit vote, May backed away from the suggestion the UK would leave the Council of Europe and ECtHR.

May used her first party conference speech as prime minister to say that “activist left-wing human rights lawyers” would “never again” be allowed to pursue claims on behalf of victims of human rights abuse by UK military forces. She was apparently referring to cases brought against the Ministry of Defence in relation to abuses in Iraq and Afghanistan. The government wants to exempt UK forces operating overseas from human rights law.

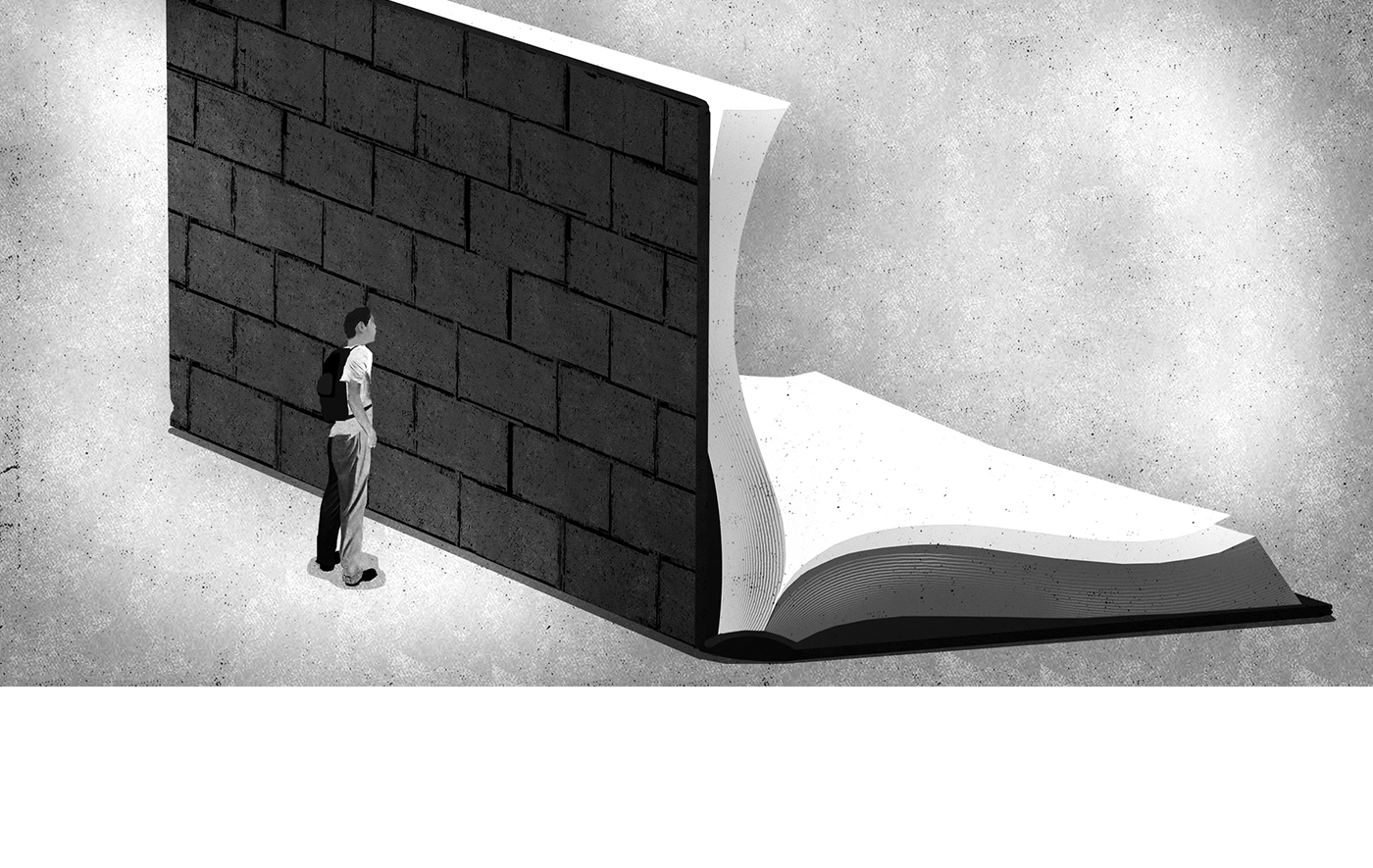

The UK made some progress on pledges to resettle Syrian and other refugees, but opted out of the EU asylum seeker relocation scheme. In late October, as French authorities moved to close the Calais camp, the UK finally stepped up efforts to bring unaccompanied children with family ties to the UK. By mid-November, the UK had brought around 300 children from the camp. Despite a legislative requirement that the government facilitate the relocation from Calais and elsewhere in the EU of unaccompanied asylum seeking children even without family ties in the UK, very few of the children brought from Calais lacked family ties, and the government imposed age and nationality restrictions on those it would accept.

In a June review, the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child called on the UK to stop detaining asylum-seeking and migrant children and expedite family reunification for unaccompanied children outside the UK.

In January, a government-commissioned independent review of the tied visa for migrant domestic workers recommended restoring their right to change employer—a key safeguard against employer abuse. The government restored the right but failed to permit visa extensions beyond the existing six-month limit, blunting the measure’s effectiveness.

In June, prosecutors announced no UK officials would face charges for involvement in the kidnap, transfer, and torture of two Libyan dissidents and their families in 2004, effectively closing the last criminal investigation for the UK authorities’ complicity in global counterterrorism abuses. A review by a parliamentary body into UK complicity in torture and rendition continued at time of writing.

The Iraq Historic Allegations Team, a body set up to investigate possible war crimes by UK forces, continued work in 2016, despite unwarranted political criticism of its existence and the principle of legal scrutiny of military operations.

In November, Parliament approved problematic legislation—the Investigatory Powers Act—entrenching and broadening state surveillance powers without adequate safeguards.