Map of Sri Lanka

I. Summary

His father opened the door, and the men pushed him aside and then forced us and the children into one of the rooms. Junith Rex came out of his room, covering himself with a bed sheet, and the men grabbed him by the bed sheet and seized him. They wore black pants, green T-shirts, and their heads were wrapped with some black cloth. Later I found out that they arrived in a van, but they parked it on the main road. They smashed the lights bulbs in the room and dragged him away. They told him “Come,” in Tamil. He cried, “Mother!” but we couldn’t help him.

— Family member describing the abduction of Junith Rex Simsan on the night of January 22, 2007, following an army search of the house earlier that same day. At this writing, despite repeated inquiries by his family, his whereabouts remain unknown, his fate uncertain.

For instance, take the missing list. Some have gone on their honeymoon without the knowledge of their household is considered missing. Parents have lodged complaints that their children have disappeared but in fact, we have found, they have gone abroad.… These disappearance lists are all figures. One needs to deeply probe into each and every disappearance. I do not say we have no incidents of disappearances and human rights violations, but I must categorically state that the government is not involved at all.

— Sri Lankan President Mahinda Rajapaksa, in an interview to Asian Tribune, October 4, 2007.

The resumption of major military operations between the government of Sri Lanka and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) in mid-2006 has brought the return of a haunting phenomenon from the country’s past—the widespread abduction and “disappearance” of young men by the parties to the conflict. With the de facto breakdown of the 2002 Norway-brokered ceasefire between the parties, and its formal dissolution in January 2008, it is likely armed conflict will intensify in the coming year. Unless the Sri Lankan government takes far more decisive action to end the practice, uncover the fate of persons unaccounted for, and prosecute those responsible, then 2008 could see another surge in “disappearances.”

Hundreds of enforced disappearances committed since 2006 have already placed Sri Lanka among the countries with the highest number of new cases in the world. The victims are primarily young ethnic Tamil men who “disappear”—often after being picked up by government security forces in the country’s embattled north and east, but also in the capital Colombo. Some may be members or supporters of the LTTE, but this does not justify their detention in secret or without due process. Most are feared dead.

In the face of this crisis, the government of Sri Lanka has demonstrated an utter lack of resolve to investigate and prosecute those responsible. Families interviewed by Human Rights Watch all talked about their failed efforts to get the Sri Lankan authorities to act on the cases of their “disappeared” or abducted relatives.

The cost of this failure is high. It is not only measured in lives brutalized and lost, but in the anguish suffered by the survivors—the spouses, parents, and children who may never learn the fate of their “disappeared” loved one. And it is felt in the fear and uncertainty that remains in the communities where such horrific, unpunished crimes take place.

This report provides extensive case material and data about enforced disappearances and abductions since mid-2006. It details the Sri Lankan government’s response, which to date has been grossly inadequate. The government shows every sign of repeating the failures of past administrations, making lots of noise—including launching a spate of new mechanisms to investigate “disappearances”—but conducting little actual fact-finding and virtually no prosecution of perpetrators. The report concludes with specific recommendations on how authorities and concerned international actors can respond more effectively. The appendix to this report contains a detailed description of 99 cases documented by Human Rights Watch. A list of 498 additional cases documented by Sri Lankan human rights groups is available at: http://hrw.org/reports/2008/srilanka0308/srilanka0308cases.pdf.

* * *

Under international law, an enforced disappearance occurs when state authorities detain a person and then refuse to acknowledge the deprivation of liberty or the person’s whereabouts, placing the person outside the protection of the law.

In Sri Lanka, “disappearances” have for too long accompanied armed conflict. Government security forces are believed to have been responsible for tens of thousands of “disappearances” during the short-lived but extremely violent insurgency from the left-wing Sinhalese nationalist Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) from 1987 to 1990, and the ongoing two-decades-long civil war between the government and the Tamil-nationalist LTTE.

Enforced disappearances have again become a salient feature of the conflict. Figures released by various governmental and nongovernmental sources suggest that more than 1,500 people were reported missing from December 2005 through December 2007. Some are known to have been killed, and others have surfaced in detention or otherwise have been found, but the majority remain unaccounted for. Evidence suggests that most have been “disappeared” or abducted. The national Human Rights Commission (HRC) of Sri Lanka does not publicize its data on “disappearances,” but Human Rights Watch learned that about 1,000 cases were reported to the HRC in 2006, and over 300 cases in the first four months of 2007 alone.

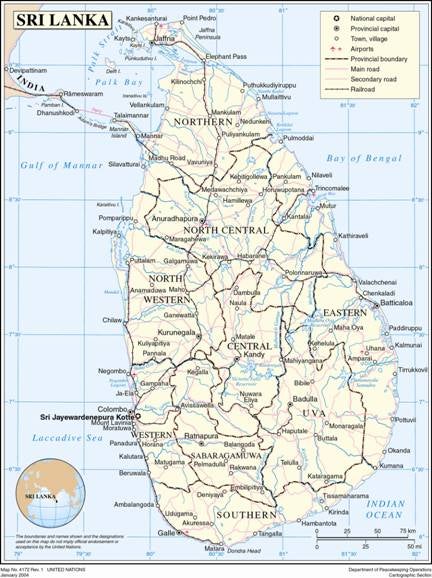

“Disappearances” have primarily occurred in the conflict areas in the country’s north and east—namely the districts of Jaffna, Mannar, Batticaloa, Ampara, and Vavuniya. A large number of cases have also been reported in Colombo.

Who Is Responsible?

In the great majority of cases documented by Human Rights Watch and Sri Lankan groups, evidence indicates the involvement of government security forces—army, navy, or police. The Sri Lankan military, empowered by the country’s counterterrorism laws, has long relied on extrajudicial means, such as “disappearances” and summary executions—in its operations against Tamil militants and JVP insurgents.

In a number of cases documented by Human Rights Watch, family members of the “disappeared” knew exactly which military units had detained their relatives, which camps they were taken to, and sometimes even the license plate numbers of the military vehicles that took them away.

In other cases, groups of about a dozen armed men took victims from their homes, located near army checkpoints, sentry posts, or other military positions. While eyewitnesses could not always identify the perpetrators beyond doubt, they suspected the military’s involvement, as it seemed inconceivable that large groups of armed men could move around freely during curfew hours and get through checkpoints without the military’s knowledge.

Relatives frequently described uniformed policemen, especially members of the Criminal Investigation Department (CID), taking their relatives into custody before they “disappeared.” The police claimed that these individuals were needed for questioning, yet did not say where they were being taken and did not produce the required “arrest receipt.” After these arrests, the families did not manage to obtain any information on the detainees’ fate or whereabouts.

The involvement of the security forces in “disappearances” is facilitated by Sri Lanka’s emergency laws, which grant sweeping powers to the army along with broad immunity from prosecution. Several provisions of the two emergency regulations currently in force create a legal framework conducive to “disappearances.” People can be arrested without a warrant and detained indefinitely on vaguely defined charges; there is no requirement to publish a list of authorized places of detention; and security forces can dispose of dead bodies without public notification and without disclosing the results of the post-mortem examination, thus preventing proper investigations into custodial deaths.

Also implicated in abductions and “disappearances” are pro-government Tamil armed groups acting either independently or in conjunction with the security forces. Relatives of the “disappeared” have often pointed to the Karuna group, which broke away from the LTTE in March 2004 and operates primarily in the east and in Colombo. In Jaffna, eyewitnesses to several abductions have implicated members of the Eelam People’s Democratic Party (EPDP), a Tamil political party that has long been targeted by the LTTE.

Both groups cooperate closely with Sri Lankan security forces. The military and police frequently use native Tamil speakers, often alleged to be Karuna group or EPDP members, to identify and at times apprehend suspected LTTE supporters. In several cases reported to Human Rights Watch, families said that they were first visited and questioned by the military, and then, usually several hours later, a group of Tamil-speaking armed men came to their house and took their relatives away. On other occasions, the Karuna group and EPDP seemed to be acting on their own—settling scores with the LTTE or abducting persons for ransom—with security forces turning a blind eye.

The LTTE has been implicated in abductions in conflict areas under the government’s control, though the numbers reported to human rights groups and the Human Rights Commission are comparatively low. This is not cause for complacency about LTTE practices which, as Human Rights Watch and others have documented elsewhere, include bombings targeting civilians, massacres, torture, political assassinations, systematic repression of basic civil and political rights in LTTE-controlled areas, and other serious abuses. In part, the LTTE abduction numbers are low because it is not the LTTE’s primary tactic; the LTTE prefers to openly execute opponents, perhaps to ensure a deterrent effect on the population. LTTE abductions may also be under-reported because the family members of the victims and eyewitnesses are often reluctant to report the abuses, fearing LTTE retribution.

Who Is Being Targeted?

No matter who is responsible for the “disappearances,” the vast majority of the victims are ethnic Tamils, although Muslims and Sinhalese have also been targeted. The security forces appear to target individuals primarily because of their alleged membership in or affiliation with the LTTE. Young Tamil men are among the most frequent targets, including a significant number of high school and university students. In other cases, the “disappearances” of clergy, educators, humanitarian aid workers, and journalists not only remove these persons from the civil sphere but act as a warning to others to avoid such activities.

In the north and east, many arrests leading to “disappearances” have occurred during or after military cordon-and-search operations following an LTTE attack. During such operations, the military either has detained people or seized their documents and requested that they report to the army camp or another location to collect them. In both scenarios, some of these people have never returned, and the relatives’ efforts to obtain any information on their whereabouts from the military have proved futile.

Particularly in Jaffna, individuals often have been “disappeared” after being stopped by military personnel at checkpoints, or as a result of targeted raids that sometimes followed claymore mine attacks or similar security incidents. In several cases in Jaffna, family members believe that EPDP cadres participated in the raids—judging by the perpetrators’ native Tamil speech, appearance, and cars leaving in the direction of EPDP camps.

In the east, Human Rights Watch received credible reports from eyewitnesses and humanitarian aid workers of “disappearances” that took place when thousands of people fled LTTE areas during fighting in late 2006 and early 2007. The army and the Karuna group reportedly screened displaced persons entering government-controlled territory to identify suspected LTTE members. In a number of cases, young Tamil men detained as a result of such screenings then “disappeared.”

Particularly in Colombo, and in the eastern districts of Batticaloa, Trincomalee, and Ampara, the lines between politically motivated “disappearances” and abductions for ransom have blurred since late 2006, with different groups taking advantage of the climate of impunity to engage in abductions as a way of extorting funds. While criminal gangs are likely behind some of the abductions, there is considerable evidence that the Karuna group and EPDP have taken up the practice to fund their forces, while the police look the other way.

Human Rights Watch has previously reported on abductions by the Karuna group in the east for the purpose of forced recruitment, including of boys. In many such cases, while the families knew that their husbands or sons were taken away to be used as soldiers, they subsequently received no information on their fate or whereabouts.

Unpunished Crimes

Enforced disappearances are a continuing offense—meaning the crime continues to be committed until the whereabouts or fate of the victim becomes known. The continuing nature of the crime takes a particularly heavy toll, with family members left wondering for months or years or forever whether their loved one is alive or dead. Some of the “disappeared” reappear as corpses showing signs of execution or torture, or turn up alive in detention in police custody or army camps, or simply turn out never to have been disappeared after all. But the great majority never turn up again and are presumed dead, victims of extrajudicial execution or other death in custody.

A critical factor contributing to continuing “disappearances” in Sri Lanka is the systemic impunity enjoyed by members of the security forces and pro-government armed groups for abuses they commit.

Police still do not investigate most of the cases and rarely follow up with families on the progress of cases, claiming they lack sufficient information to identify perpetrators and locate victims. As detailed in this report, however, family members say that even when they provide details to the police that should at least give a start to an investigation—such as the license plate numbers of the vehicles allegedly used in the abductions and the names of people or military units the family believes were involved—police do not follow through.

Figures on accountability released by the government show how little has been done to bring perpetrators to justice. A document provided to Human Rights Watch by the Sri Lankan government in October 2007 mentions only two pending cases against army personnel for unspecified human rights violations committed in 2005-2006, and refers to a recent indictment served on an unspecified number of army personnel for the killing of five students in Vavuniya in 2007. None of the indictments for abductions and “wrongful confinement” mentioned in the document appear to be for abuses committed since mid-2006.

The only known arrests for recent abductions were of former Air Force Squadron Leader Nishantha Gajanayake and another two policemen and an air force sergeant in June 2007. Although Sri Lankan authorities widely publicized these arrests as proof of their resolute action against the abductors and promised to promptly bring the perpetrators to justice, in early February 2008 the suspects were released; it is unclear whether charges against them were dropped.

The Government’s Response

Instead of making a diligent effort to investigate and prosecute enforced disappearances, the government of President Mahinda Rajapaksa continues to downplay the scope of the problem. Many official statements suggest there is no “disappearance” crisis at all or, if there is one, the sole perpetrators are LTTE fighters and common criminals. While the government has set up various mechanisms to address abductions and “disappearances,” all have lacked the independence, power, resources, and capacity necessary to conduct effective investigations.

Sri Lanka has a long history of setting up mechanisms to address “disappearances” but not following through. Four official commissions of inquiry set up by then President Chandrika Kumaratunga in the 1990s established that more than 20,000 people “disappeared” during armed conflicts in the 1980s and 1990s. Human rights groups believe that the actual figure may be two to three times higher. These commissions identified suspected perpetrators in more than 2,000 cases, but few have ever been prosecuted, and only a handful of low-ranking officers were convicted. Nor have successive governments meaningfully implemented the commissions’ recommendations for legal and institutional reforms aimed at preventing “disappearances” in the future.

The Rajapaksa government’s response to the surge in “disappearances” starting in mid-2006 appears to be following this pattern. First, the independence of existing government bodies, the Human Rights Commission and the National Police Commission, has been significantly undermined by decisions by the president to bypass constitutional requirements and directly appoint commissioners to these bodies.

Despite the hundreds of alleged “disappearances” reported over the last two years to the Human Rights Commission, it has issued no public reports on the matter, has refused to provide statistics on the complaints it has received, and has tried to downplay the scale of the problem. The monitoring and investigative authority of the Human Rights Commission has also been effectively negated by the obstructive attitude of the security forces and lack of support from the government. As a sign of the HRC’s failings, in December 2007 the international body that regulates national human rights commissions downgraded the HRC’s status to “observer” because of government encroachment on its independence.

Second, while the government has created at least nine other special bodies to address “disappearances” and other human rights violations—all of them described in the report—as yet none of them have yielded concrete results.

Aside from periodic announcements on their establishment, the government rarely has provided any information regarding the mandate of such bodies, or the progress made in the investigations. The government also has not explained whether it continues to create new bodies because of the inability of previously established mechanisms to deal with the problem, or whether it is simultaneously correcting flaws in existing mechanisms.

Many observers believe that most of these bodies have been established to give the impression the government is taking seriously reports of widespread “disappearances” by security forces even as officials dither in initiating investigations into the cases. The government’s continuing dismal record in prosecuting perpetrators lends credence to such beliefs.

The lack of progress in investigations and the failure to halt the abuses is hardly surprising given that, at the highest levels, the Sri Lankan government continues to deny any new “disappearance” crisis or that its security forces are responsible for any significant portion of the violations. Typical in this respect are claims made by Judge Mahanama Tillekeratne, who stated that the abductions were “the result of personal grudges,” and that the majority of the missing persons have returned, neither of which claim is substantiated by the evidence.

President Rajapaksa, government ministers, and the government’s Secretariat for Coordinating the Peace Process (SCOPP) also have repeatedly dismissed reports of widespread “disappearances” as LTTE propaganda aimed at smearing the state’s image. They have claimed that most of the missing individuals have returned, left the country, went into hiding to escape criminal charges, or simply left home and failed to inform their families of their whereabouts—without providing facts to support these contentions.

These claims contradict statements made by some Sri Lankan law enforcement officials, such as the inspector general of the police, and information, albeit limited, that has been released by the governmental commissions, as well as facts and figures publicized by the media and NGOs. Such claims also invite the obvious question of why the government has felt the need to establish so many different mechanisms to look into an allegedly non-existent problem. High-level attempts to dismiss the problem of “disappearances” send a signal to security forces that the government does not take the allegations of their involvement in human rights abuses seriously.

International Response

Various United Nations mechanisms and some of Sri Lanka’s key international partners have raised concerns about the high number of enforced disappearances since mid-2006. Senior UN officials visiting Sri Lanka such as the High Commissioner for Human Rights, the Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions, and the Special Advisor on Children and Armed Conflict, have all noted the alarming prevalence of impunity and the failure of law enforcement bodies and national human rights mechanisms to establish accountability. Foreign governments such as the United States and United Kingdom have also spoken out.

Sri Lanka’s response to the growing international criticism has taken two forms. The government has intensively lobbied international organizations and bilateral partners, emphasizing improvements in the human rights situation and its willingness to cooperate with UN officials and human rights specialists. At the same time it has fiercely attacked its critics, including the very same UN representatives, accusing them of being, at best, ignorant of the situation and, at worst, LTTE sympathizers.

The continued refusal of the Sri Lankan government to acknowledge and adequately address the wide range of human rights violations has led to growing national and international support for the establishment of a UN human rights monitoring mission to investigate and report on abuses by government forces and the LTTE throughout the country.

The European Union and more recently the US government have joined the calls of domestic and international NGOs for establishing an international monitoring mission under the auspices of the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. During her October 2007 visit to Sri Lanka, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Louise Arbour expressed the willingness of her office to work with the Sri Lankan government toward establishing such a presence.

The Sri Lankan government has thus far rejected the proposals for any international monitoring mechanism. This response belies the government’s claims that it is taking the measures necessary to protect the rights of all its citizens.

Key Recommendations

- The Sri Lankan government should publicly acknowledge the scope of “disappearances” in the country and the continuing role of security forces in committing such abuses.

The Sri Lankan government will not make meaningful progress in ending “disappearances” until it takes the problem seriously and is seen to be taking it seriously. However many new mechanisms the government creates, their efforts cannot be expected to succeed when senior officials deny there is a serious problem. An essential starting point is unambiguous acknowledgment of the problem, and of the role of security forces and pro-government, non-state armed groups in perpetuating the practice.

- The Sri Lankan government should reform detention procedures to ensure transparency and compliance with international due process standards.

In order to stop the spree of new “disappearances,” the government should ensure that all persons taken into custody are held in recognized places of detention, and each facility maintains detailed detention records. Detained individuals must be allowed contact with family and unhindered access to legal counsel; they should promptly be brought before a judge and informed of the reasons for arrest and any charges against them.

- The Sri Lankan government should vigorously investigate and prosecute perpetrators of “disappearances.”

Lack of accountability for perpetrators is one of the key factors contributing to the crisis of “disappearances.” The authorities must vigorously investigate all cases of enforced disappearances and arbitrary arrests, including those documented in this report—until in each case the fate or whereabouts of the person is clearly and publicly established. Those responsible for “disappearances” and abductions, be it members of government security forces or members of non-state armed groups, must be disciplined or prosecuted as appropriate.

- The government and the LTTE should cooperate with the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights to establish and deploy an international monitoring team to report on violations of international human rights and humanitarian law by all parties to the conflict.

Deployment of an experienced international monitoring team would save lives, curtail abuses, and promote accountability. Here, the burden rests not only with the Sri Lankan government and LTTE, but also with concerned international actors. The latter should make it clear that they view the Sri Lankan government’s position on deployment of such a team as an important test of its commitment to human rights and its willingness to take real, rather than feigned, measures to address continuing problems. Sri Lanka’s international partners, in particular India and Japan, should make further military and other non-humanitarian assistance to Sri Lanka contingent on government efforts to halt the practice of “disappearances” and to end impunity, including its acceptance of an international monitoring team.

International monitoring has proven particularly effective in dealing with the problem of large-scale “disappearances.” With sufficient mandate and resources, the monitoring mission could achieve what the government and various national mechanisms have failed to do—establish the location of the detainees through unimpeded visits to the detention facilities; request information regarding specific cases from all sides to the conflict; assist national law enforcement agencies and human rights mechanisms in investigating the cases and communicating with the families; and maintain credible records of reported cases.

Detailed recommendations to the Sri Lankan government, the LTTE, and the international community are found in the closing chapter of this report.

Note on Methodology

This report is based on field research carried out in Sri Lanka in February, March, and June 2007, and follow-up research through January 2008. Human Rights Watch conducted over 100 interviews with families of the “disappeared,” as well as dozens of interviews with human rights activists, lawyers, and international agencies working in Sri Lanka. Human Rights Watch visited Colombo and its environs, and the districts of Batticaloa and Jaffna.

Following the visits, Human Rights Watch communicated closely with local NGOs and international organizations working in Sri Lanka to update the information and obtain new data.

Human Rights Watch has raised its concerns in various meetings with the president of Sri Lanka, the foreign minister, and the minister for disaster management and human rights, among other Sri Lankan officials. Human Rights Watch sent inquiries to various Sri Lankan authorities—the Ministry for Disaster Management and Human Rights, the Inspectorate General of the Police, the Defense Ministry, the Human Rights Commission, and the Presidential Commission on Abductions, Disappearances, and Killings—requesting information related to the issues raised in this report. Human Rights Watch also sent an inquiry to Eelam People’s Democratic Party (EPDP).

Human Rights Watch received responses from the Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka and the Sri Lankan police. The EPDP also responded to the inquiry. Their responses are incorporated in the relevant sections of this report. Other officials mentioned above did not respond to Human Rights Watch inquiries. Human Rights Watch letters of inquiry and responses we have received are appended to this report (Appendix II).

Appendix I of this report contains detailed descriptions of 99 cases of “disappearances” and abductions documented by Human Rights Watch. A list of 498 additional cases reported to Sri Lankan human rights groups is available at: http://hrw.org/reports/2008/srilanka0308/srilanka0308cases.pdf.

While all efforts were made to ensure that information in Appendix I is up to date, given the challenge of obtaining information from some parts of Sri Lanka, especially the north, it is possible that new developments may have occurred in some of the cases before the report went to print.

Human Rights Watch also notes that in some of the documented cases there were no eyewitnesses to the abduction or arrest, and such cases may not technically qualify as “disappearances.” Most such cases were excluded from this publication; where we have included such cases it is because there is other evidence, set forth during our discussion of the case, suggesting the victim was abducted by a pro-government armed group, the LTTE, or government security forces.